How UK aid learns

Executive summary

As ICAI has observed in many of its reviews, applying learning to programmes is fundamental to the quality, impact and value for money of UK aid. Since 2015, the UK government has involved more departments in the spending of UK aid. Around a quarter of the £14 billion annual aid budget is now spent outside DFID. This has given rise to a major organisational learning challenge, as 18 departments and funds have worked to acquire the knowledge and skills to spend aid effectively.

This rapid review assesses the quality of the learning processes around non-DFID aid. Building on a 2014 ICAI review of How DFID learns, it looks across the other aid-spending departments. It draws on findings from past ICAI reviews of particular funds and programmes, together with light-touch reviews of learning processes within each department, using an assessment framework developed for the purpose. Our findings per department are summarised in the Annex, and are intended to encourage departments to look in more depth at their own learning needs and capabilities. We also assessed how well aid-spending departments exchange learning with each other and with DFID.

Learning within aid-spending departments

The decision to allocate the UK aid budget across multiple departments posed a major learning challenge. Departments with new or increased aid budgets had to acquire the systems, processes and capabilities needed to meet the eligibility requirements for official development assistance (ODA), HM Treasury rules and the 2015 UK aid strategy requirement of ‘international best practice’ in aid management. There was no structured process for developing these capabilities, and no additional resources were provided to support the learning process. Past ICAI reviews have found that there were significant value for money risks involved in scaling up departmental aid budgets before the necessary capacities were in place.

Each department has gone about meeting this learning challenge in its own way. Overall, they have made important progress in building up their aid management capabilities, with investments in learning that are broadly commensurate with the size and complexity of their aid budgets. Departments with large aid budgets have developed more complex systems for generating and sharing learning. Those with smaller aid budgets, or whose aid spending is more transactional (for example support costs for refugees in the UK by the Department for Education), have made do with simpler arrangements. A third group of departments, which are actively pursuing larger aid budgets, have been the most active in building up their aid management capabilities, including drawing on learning from other, more experienced departments.

However, we find that learning processes are not always well integrated into departments’ systems for managing their aid. Learning is often treated as a stand-alone exercise or a discrete set of products produced to a predetermined timetable. The challenge is to ensure that the resulting knowledge is actively used to inform management decisions in real time. This involves building a culture of evidence-based decision making, and a willingness to embrace failure as well as success as a source of learning. The ultimate goal of learning systems is not to meet an external good practice standard, but to make departments more effective in the management of their aid portfolios.

In many instances, departments have contracted out monitoring, evaluation and learning functions to commercial providers. Outsourcing learning can be an effective way of overcoming internal capacity constraints and accessing technical expertise. However, the knowledge and know-how may then ccumulate in the commercial supplier, without being properly absorbed by the department itself.

A potential benefit of involving more departments in delivering UK aid is the ability to draw on technical skills from their core mandates – such as on health, justice or taxation.

We find that their expertise is indeed being used, with significant exchanges of learning between aid programmes and other activities in many departments.

Learning between aid-spending departments

We found many good examples of the exchange of learning between departments. Many of the key informants we interviewed recognised the importance of shared learning, and we identified a large number of learning interactions. There has been a proliferation of cross-departmental groups and forums where learning is exchanged. However, many of these structures are new and not yet fully operational. A clearer architecture and set of expectations would enable more shared learning.

The best prospects for shared learning emerge where aid-spending departments work closely together in country. Stakeholders agreed that co-location of staff in UK missions overseas facilitates learning, collaboration and coherence.

The UK government has made a strong commitment to transparency in UK aid, recognising it as a driver of value for money. It is also a facilitator of cross-government learning. The 2015 aid strategy commits all aid-spending departments to achieving a ranking of ‘good’ or ‘very good’ on the Aid Transparency Index, which measures the progress of donors on publishing their data to an international open data standard for aid known as the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). So far, progress towards this target is mixed, with some departments yet to publish data in this format.

DFID publishes its programme documents on an online platform, DevTracker, providing other departments and the public with detailed information on the design and performance of its programmes. Most other aid-spending departments are not providing this level of transparency. There is no overarching requirement on the publication of aid-related documents.

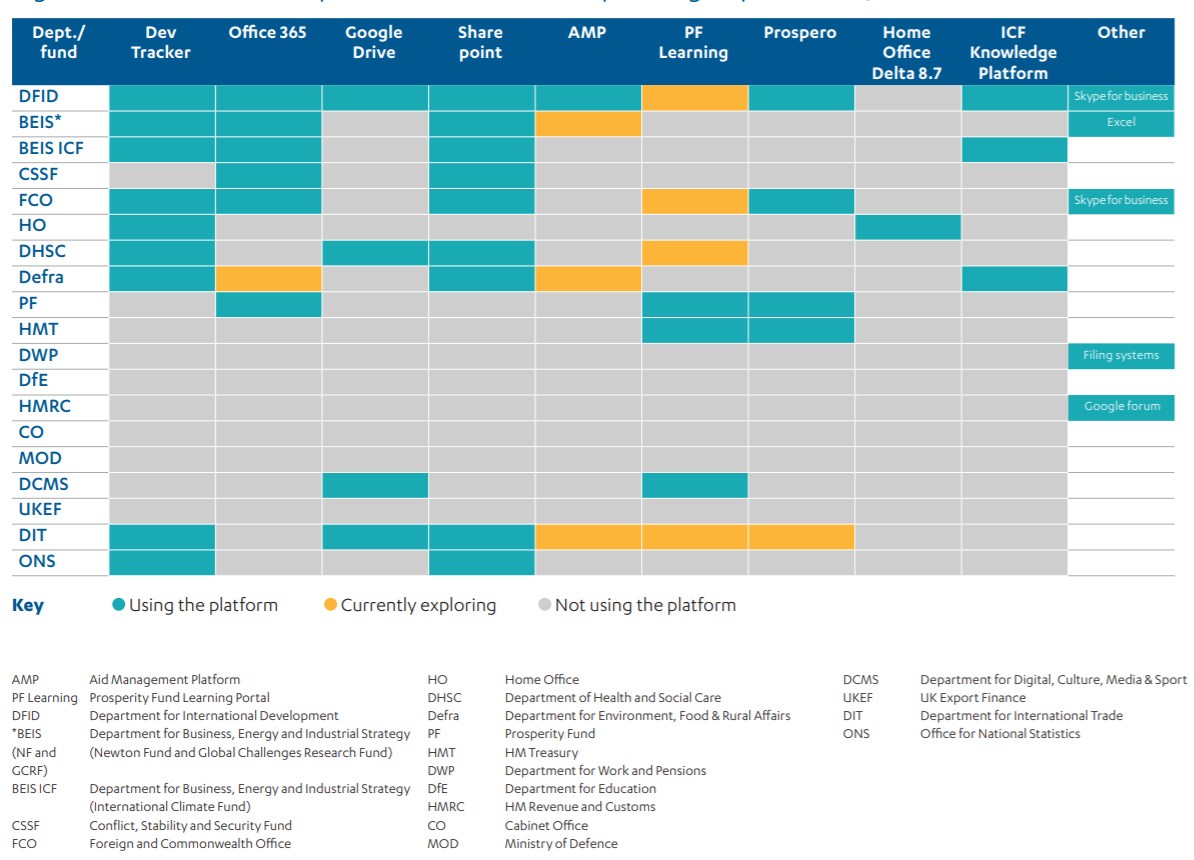

A number of departments have made progress on developing information platforms that capture learning on development practice. DFID, the Prosperity Fund, the Home Office (on modern slavery) and UK International Climate Finance (BEIS, DFID and Defra) all have promising technical platforms for knowledge management. However, these platforms are currently not accessible across departments, both because of information security concerns and because technical constraints prevent them from being interoperable. There is therefore considerable scope to improve both the publication of aid data and sharing of learning between departments.

DFID’s support for other aid-spending departments

Under UK government rules, each department is accountable for its own expenditure. DFID is mandated under the UK aid strategy to support other departments with their aid expenditure, but has no formal mechanisms for overseeing their work or ensuring good practice.

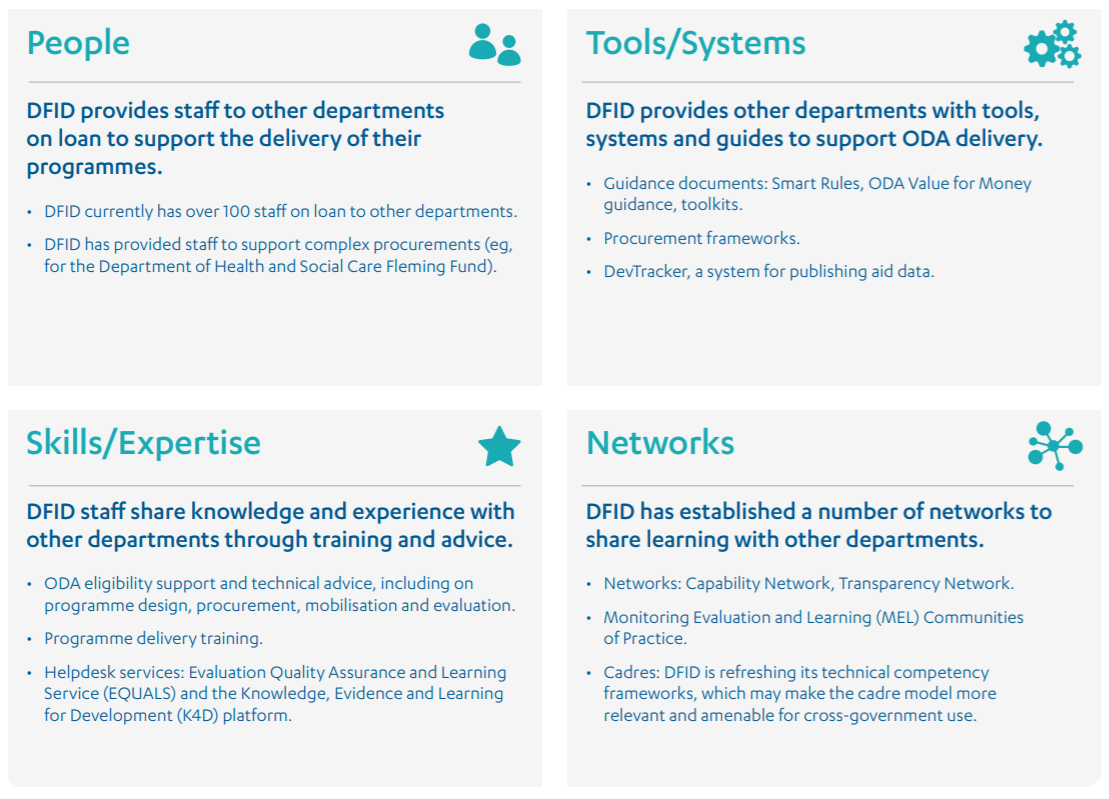

We find that DFID has been active in supporting other departments with their learning on aid in a wide variety of ways, including:

- People: DFID seconds over 100 staff per year to other departments, and others are loaned for short periods to support specific tasks.

- Tools: The Smart Rules, and the guidance and software that DFID uses to support programme management, are available to other departments.

- Skills: DFID shares its knowledge and expertise through training, advisory support and helpdesk services.

- Networks: DFID has established a range of networks to share learning with other departments on particular thematic areas or aid management challenges.

However, there are some practical limitations to DFID’s offer; its networks, for instance, are not widely publicised.

Most departments have welcomed DFID’s support, recognising its important role as a repository of expertise on aid management. As the International Development Committee observed in June 2018, “DFID has a crucial role to play in ensuring that all other government departments understand how to administer ODA programmes effectively and efficiently.”

Importantly, exchange of learning between DFID and other departments goes both ways. We came across a range of examples where cross-government technical expertise was being drawn on to raise the quality of DFID programming. In particular, secondments and staff transfers are proving to be an important mechanism for transferring learning across government.

Despite its important role, DFID has not received any additional staffing resources to support learning on aid management across government. Given the scale of the challenge involved in building aid management capacity across multiple departments, this is a significant omission. We expect that the question of resourcing support to other departments will come up in any future Spending Review.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

DFID should be properly mandated and resourced to support learning on good development practice across aid-spending departments.

Recommendation 2

As part of any Spending Review process, HM Treasury should require departments bidding for aid resources to provide evidence of their investment in learning systems and processes.

Recommendation 3

The Senior Officials Group should mandate a review and, if necessary, a rationalisation of major monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) contracts, and ensure that they are resourced at an appropriate level.

Recommendation 4

Where aid-spending departments develop knowledge management platforms and information systems to support learning on development aid, they should ensure that these systems are accessible to other departments and, where possible, to the public, to support transparency and sharing of learning.

Introduction

In our 2014 ICAI review of How DFID learns, we wrote that “excellent learning is essential for UK aid to achieve maximum impact and value for money.” Learning is fundamental to the ability of any organisation to achieve its objectives – particularly in times of change and uncertainty, when it needs to learn and adapt in real time. It is ICAI’s experience that continuous learning is essential to the achievement of impact and value for money. The quality of learning is therefore an area that we explore in many reviews.

Building on the 2014 review, this review looks at learning across other aid-spending departments and cross-government funds. It incorporates findings from a number of other ICAI reviews that have looked at learning in non-DFID funds and programmes. The review explores how learning takes place within departments, and what resources they are devoting to the learning process. We also look at what learning is taking place between departments and the extent to which they exchange knowledge with DFID.

As we did in How DFID learns, we define learning as the process of gaining and using knowledge and know-how to shape policies, strategies, plans and actions. There are many ways of building a learning organisation; we are not looking for any particular approach, but for evidence of a deliberate and thoughtful approach to learning.

Our review covers the period since the 2015 aid strategy, which signalled a growing role for other departments and cross-government funds in the delivery of UK aid. We explore how departments have tackled the challenge of acquiring a knowledge of good practice in aid management and development cooperation. Although not our original objective, the topic has also generated insights into how the sharing of knowledge and learning between departments enhances or constrains coherence across a fragmented aid budget – an issue that the National Audit Office has recently highlighted.

This is a rapid review, conducted over seven months, based on interviews with the relevant departments and documents provided by them. As a rapid review, it is not scored, but it does reach evaluative judgments based on our review questions (see Table 1). With 18 departments and funds involved in the spending of UK aid in 2018, the depth of analysis of individual departments is necessarily limited, but each has been given an opportunity to comment on our findings and correct any errors.

Our findings follow the main review questions below. As it became clear that DFID has a specific role to play in cross-government learning on UK aid, we added a third review question on how DFID interacts with other departments.

Table 1: Our Review Questions

| Review questions | |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance | To what extent do aid-spending departments have systems and processes, resources and incentives in place to enable eff ective learning about their spending of ODA? How effectively is learning being used to improve the design and delivery of aid programmes within aid-spending departments? |

| 2. Effectiveness | How effectively is learning shared across aid-spending departments and used to improve the eff ectiveness and value for money of aid? |

| 3. Effectiveness | How well does DFID support learning across government? |

Methodology

Figure 1: Overview of the methodology

In order to cover 18 departments and funds within the scope of a rapid review, we chose a methodology that was broad rather than deep. It draws on four interlocking sources of evidence:

- A review of the recent literature: We updated the literature review on learning that we undertook for How DFID learns. As well as bringing in more recent studies on good learning practice, the scope of the literature review was expanded to cover adaptive programming, the contribution of learning and knowledge management to ‘joining up’ government and the elements of a supportive institutional architecture for learning. This literature update can be viewed on the ICAI website.

- Document review: We collected and analysed over 450 documents from aid-spending departments on their approach to learning. We also collected evidence from past ICAI reviews since 2015 that assessed learning within aid-spending departments other than DFID and/or cross-government funds.

- Key informant interviews: We conducted more than 100 interviews (see Figure 2) with officials from aid-spending departments, both in person in Whitehall and by telephone with representatives from two selected countries, Kenya and Pakistan (see Box 1). We also conducted interviews with a range of external stakeholders, including from other development partners and aid-spending organisations.

- Inter-departmental relationship mapping: We have mapped the exchange of learning among aid-spending departments in the 2016-18 period, including support provided by DFID to other departments.

Box 1: Country selection

Some aid-spending departments have representatives in developing countries, based in UK diplomatic missions or embedded within national institutions. To extend our analysis of how departments collaborate and share learning at the country level, we selected two countries: Kenya and Pakistan. These countries were selected as demonstrating a number of criteria of interest to the review, including:

- fragility and conflict risk (which arguably calls for a quicker and more adaptive approach to learning)

- importance as a trading partner for the UK (active engagement by more UK departments)

- sizeable UK aid expenditure

- a significant number of ODA-spending departments represented in country.

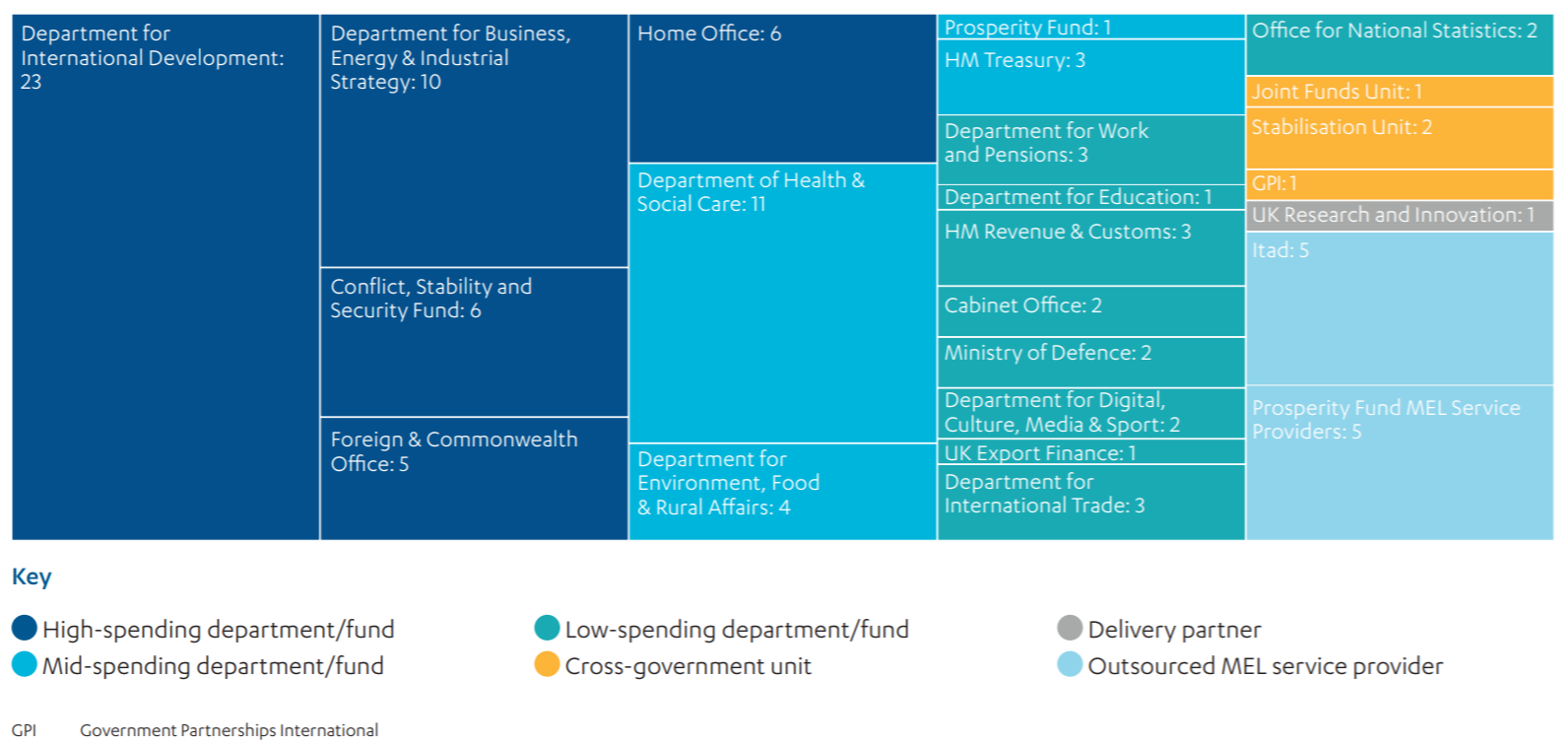

Figure 2: Stakeholders interviewed for this review

We interviewed 103 people across 18 government departments and funds:

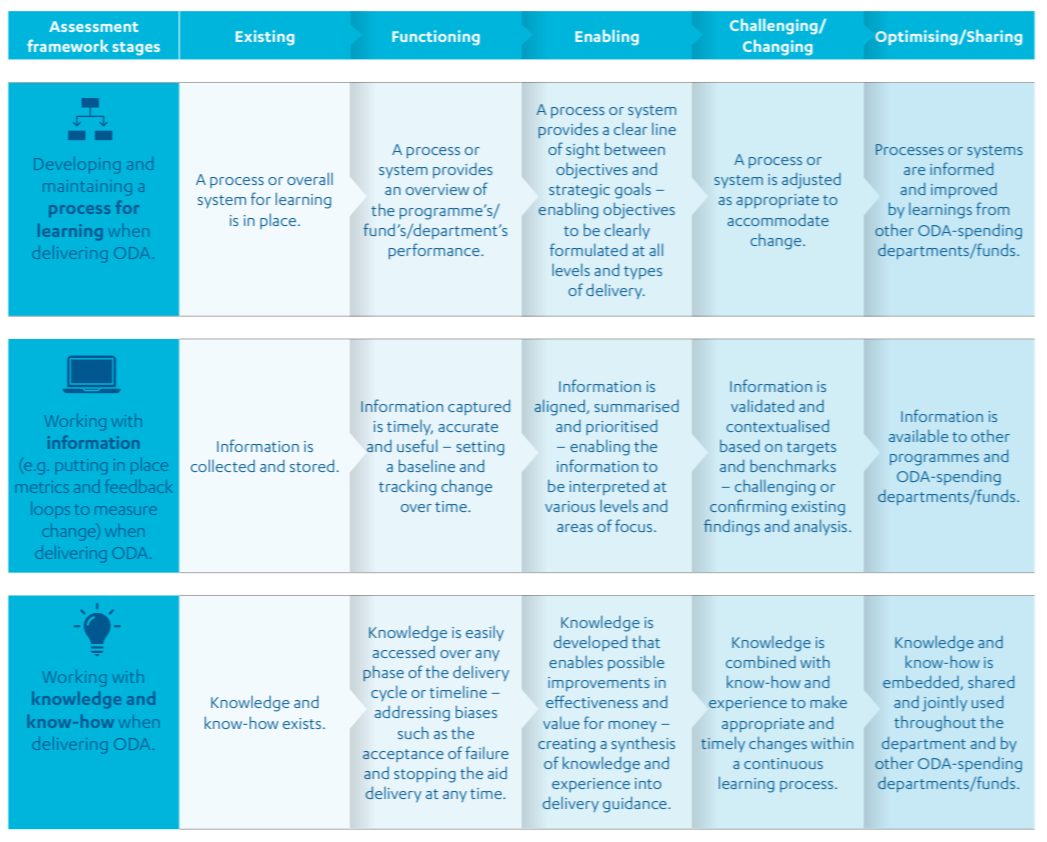

To support our analysis, we developed an assessment framework to help us identify good learning practice. The framework specifies the various elements needed to ensure an effective learning organisation, depending on the size and complexity of their aid budgets. It draws on the ‘maturity model’ that the National Audit Office has developed for performance measurement and its use in decision making. The framework recognises that the diversity of aid portfolios across departments – from single transactions to multi-million pound programmes – also calls for differences in learning approaches.

Figure 3: Assessment framework: ‘what good looks like’

ODA learning in and across departments.

We used this framework to guide our assessment of individual departments/funds, based on interviews and relevant documentation. Our assessments of individual departments are summarised in the Annex. We hope these will be used as starting points for the departments in question to look in more depth at their learning needs and capabilities.

Our methodology and an advanced draft of this report were peer-reviewed.

Box 2: Limitations to our methodology

There are limitations to the depth of our analysis given the high number of departments and funds reviewed and the limited scope of this rapid review. While we recognise that learning is also occurring within and between non-departmental public bodies and delivery partners, they were not the focus of this review. Our questions are at the level of departmental/fund ODA spending. We were only able to speak to a limited number of respondents per department. Obtaining key documents across multiple departments proved challenging and delayed our initial delivery timeframe. In the context of an ongoing Spending Review, our findings provide only a snapshot of progress at this point in time. This review is intended to be a preliminary assessment only, to encourage further self-assessment by aid-spending departments.

Background

The importance of learning to organisational performance

Effective learning is key to the effectiveness and value for money of UK aid. The literature is clear that an active approach to learning is an essential feature of any effective organisation. However, there is no single model for learning. It can range from the simple exchange of information to more sophisticated processes for turning information into knowledge and know-how. What is critical is that learning is applied to practice, leading to adaptation and improvements in performance.

The processes of learning and adaptation usually require at least three steps:

- generate accurate, timely and relevant feedback on performance

- create opportunities to reflect, challenge, assimilate or accommodate this feedback

- choose and implement timely and appropriate change.

This process requires supportive cultures and systems.

Box 3: Six elements of effective learning

In our 2014 review of How DFID learns, drawing on a review of the literature on organisational learning, ICAI identified six elements in the learning process:

- Clarity: a shared vision of how learning takes place

- Connectivity: establish a ‘learning community’ in which individuals and networks can interact

- Creation: using data and information to generate knowledge and know-how

- Capture: assimilating knowledge and know-how

- Communication: sharing knowledge and know-how across the organisation

- Challenge: using knowledge and know-how to challenge practice.

A key insight from the literature – and a finding from our 2014 review of How DFID learns – is that learning occurs through both formal and informal processes. The former are mandated and supported from the top of an organisation, with dedicated structures and processes. But learning also takes place spontaneously, through informal interactions. Successful learning strategies therefore also help to build broader social networks that expand opportunities for informal learning.

There also needs to be a balance between individual and organisational learning. Motivated people will find opportunities to learn, according to their preferences. However, people move on, and their experience and know-how need to be captured in a more structured way in order to be accessible across the organisation.

Finally, learning is about managing complexity and change. Development cooperation is inherently complex and development assistance work takes place in very dynamic contexts. Learning therefore needs to be continuous and embedded throughout the delivery cycle, rather than confined to fixed learning products delivered to a predetermined cycle. In recent years, DFID has worked to introduce adaptation into its management processes, to facilitate continuous learning at the programme level. At a higher level, continuous learning means ensuring that performance information and learning are closely integrated with the management process, to allow for a rapid learning cycle.

The evolving architecture of UK aid delivery

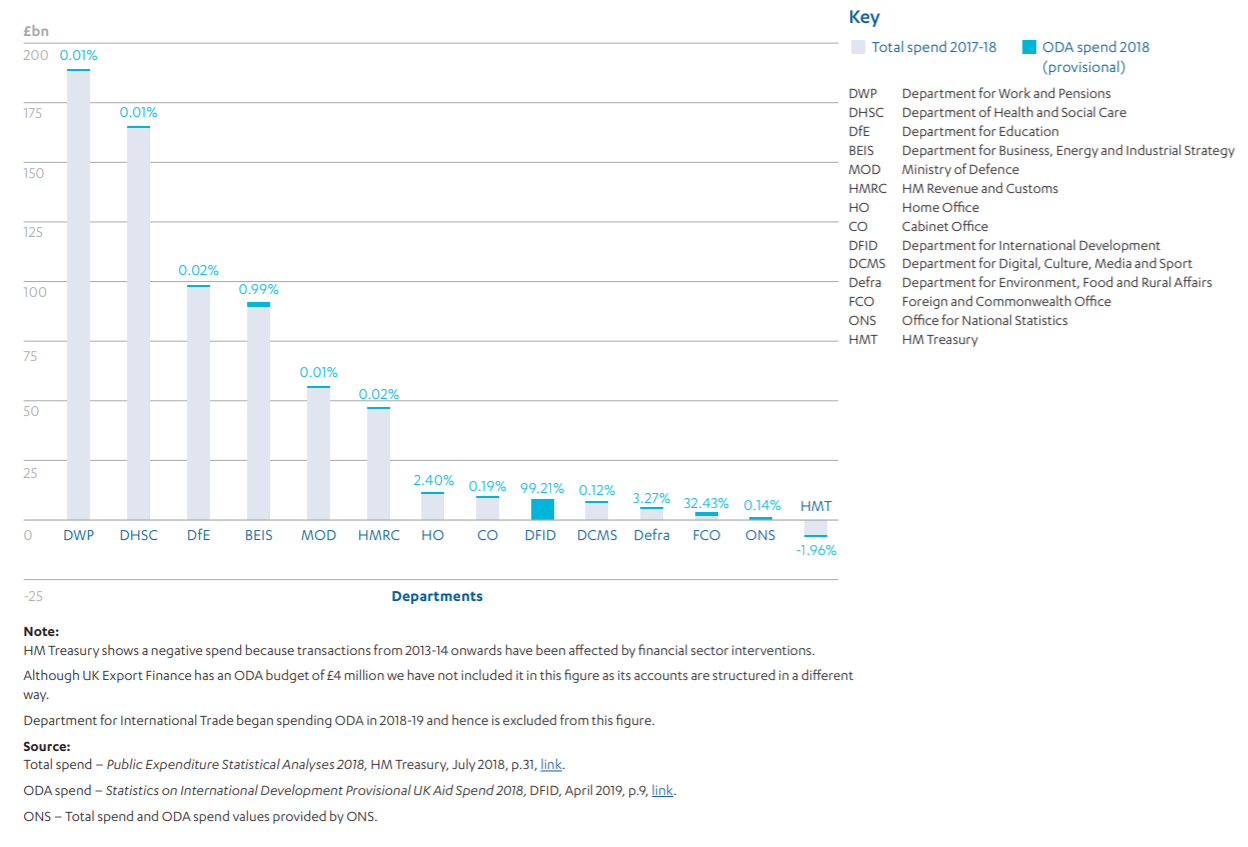

Since the 2015 aid strategy, the proportion of UK aid spent by departments other than DFID has rapidly increased – from 14% in 2014 to 25% in 2018, or just under £3 billion. While DFID’s budget has continued to rise in absolute terms, aid expenditure in a number of other departments has grown much more rapidly. Figure 4 shows the major aid-spending departments. However, with the exception of DFID and the Foreign Office, ODA accounts for only a minor share of each department’s overall budget.

Figure 4: More departments now have substantial aid budgets, although for most it represents a minor share of their overall budgets

Total 2017-18 departmental spend and 2018 ODA spend

Potentially, this wider distribution of UK aid across departments allows the aid programme to benefit from a broader range of technical expertise – for example, on health, education, justice or taxation. However, it also amounts to a fundamental shift in the organisation of the UK aid programme, requiring aid management capacity to be developed across multiple departments. For new aid-spending departments, it takes several years to put the necessary systems and capacities in place.

The large number of government aid spenders creates new challenges around ensuring coherence and accountability for UK aid as a whole. UK aid is now spent by multiple funds and programmes with different objectives, approaches and systems. There are processes in place to ensure that the legislative requirement of spending 0.7% of gross national income on aid is met, and that UK aid statistics are accurate. However, each department is responsible for managing its aid expenditure according to its own rules and procedures, with no overall mechanism for ensuring the quality of aid investments.

In 2018, the National Security Capability Review introduced the ‘Fusion Doctrine’ – the objective of increased coherence among the UK’s tools of external influence, in pursuit of common objectives. This implies a need for an even more sophisticated learning process, capable of linking up development cooperation with other areas of external engagement, including diplomacy, trade and security.

The International Development Committee has questioned whether the current organisational arrangements support the goal of increased coherence. In June 2019, the National Audit Office also raised concerns that a fragmented aid architecture was working against coherence in UK aid.

“Strong and effective cross-government mechanisms should form the bedrock of an effective system of cross-government ODA. The current arrangements leave opportunities for gaps in coherence and ambiguity in where oversight of ODA lies across Whitehall. This creates a risk of duplication, overlap or conflicting priorities in programmes. Without a single person responsible, this also means that there is no single check on the overall coherence or quality of UK ODA as a whole and no central point for capturing examples of added value.”

Definition and administration of ODA inquiry, Final Report, International Development Committee, 5 June 2018.

The November 2015 aid strategy states that all aid-spending departments are required to meet ‘international best practice’ in their processes for spending UK aid. In May 2018, three years after departments had begun to receive their new funding, HM Treasury and DFID elaborated on some of the requirements, including in financial management, procurement, programme design and monitoring and evaluation. Meeting the high standard of international best practice consistently across UK aid implies the need for active exchange of knowledge and learning across departments.

Findings

In this section, we set out our findings against our review questions. We comment first on how well ODA-spending departments/funds are learning around the delivery of aid. We then look at how well these departments are sharing learning with each other. Finally, we comment on the extent to which they are exchanging learning with DFID.

To what extent do aid-spending departments have systems and processes, resources and incentives in place to enable effective learning about their spending of ODA?

There was no structured process for building aid management capacity in new aid-spending departments

The decision to allocate the UK aid budget across multiple departments has been a major organisational shift, raising complex learning challenges. The 2015 UK aid strategy states that:

“All departments spending ODA will be required to put in place a clear plan to ensure that their programme design, quality assurance, approval, contracting and procurement, monitoring, reporting and evaluation processes represent international best practice.”

Departments that were new to aid spending, or that saw their aid budgets increase rapidly, faced a major challenge in developing systems, processes and capabilities to meet this ‘international best practice’ standard.

To comply with the international ODA definition and UK legislation, they had to put in place processes to ensure that the expenditure promotes the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective, and that it is likely to contribute to poverty reduction. They also had to ensure that they considered options for advancing gender equality within each aid programme.

HM Treasury rules governing the spending of any UK public money require, among other things, evidence-based business cases for programmes and processes for monitoring and evaluating results, proportionate to the scale and risk of the expenditure. Value for money guidance issued by the Treasury and DFID in May 2018 summarises these requirements and sets out additional good practice principles, including the need for context- and conflict-sensitive programme design, policies to safeguard vulnerable people and environments, and robust monitoring of inputs, outputs and outcomes. However, the three-year delay between committing new spending to departments in 2015 and the publication of this guidance was problematic since departments were left to decide for themselves what good practice looked like.

There was no overall plan for how these capacities would be developed, and no structured process to help new aid-spending departments build the necessary systems and processes. Nor were any additional resources provided to support the learning process. We find this to be a striking omission. Past ICAI reports have found that it takes several years to develop the capacity to spend aid well. Scaling up departmental aid budgets before the necessary systems were in place entailed both value for money risks and dangers of non-compliance with the ODA definition. The National Audit Office (NAO) similarly noted the risk that departments might seek access to ODA funds without a full understanding of whether they have the capability to carry out the work.

Departments have been on a steep learning curve

In the absence of a structured change management process, each aid-spending department has approached the task of acquiring the necessary learning in its own way. We find that most have made important progress in building capacity to deliver aid. Past ICAI reports have pointed to a range of initial shortcomings, such as:

- a lack of rigour in assessing ODA eligibility (the Prosperity Fund, as well as the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) as owner of the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and the Newton Fund)

- delays in developing fund-level strategies, including clarity on primary and secondary objectives (BEIS: GCRF and Newton Fund)

- a lack of appropriate monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) arrangements (the Prosperity Fund, the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), BEIS: GCRF and Newton Fund).

However, when we have subsequently followed up with departments on their response to our reports, they have in many cases been able to show significant improvement. This demonstrates that learning is indeed occurring, albeit to different degrees.

The Annex sets out our summary findings on the state of learning on aid for each aid-spending department. We would expect to find that the level of effort put into building learning systems is broadly commensurate with the size, type and complexity of each department’s aid budget. High-spending departments such as the Foreign Office (FCO) and BEIS require more complicated systems, deeper learning and more sharing of knowledge and know-how. We would expect them to invest in platforms to store and access information, and also to build the capacity to add value to that information. They should have processes to ensure its accuracy, and to share their knowledge and know-how internally, across government and with partners.

The FCO has a large and complex aid portfolio, spread across a large number of thematic programmes and overseas posts. This diversity of topics and proliferation of spending channels has been a barrier to the emergence of a shared learning architecture for its aid expenditure. Since 2015, the FCO has taken steps to develop a more integrated approach to managing its programmes, covering both ODA and non-ODA expenditure, under an FCO Portfolio Board. It has increased its investment in staff training and technical support facilities, and built up a 140-person Project Delivery Cadre. However, we found that learning practices are still uneven across the department. The planned development of a common operating framework for aid programmes may help to encourage greater consistency in approach. The FCO is exploring options for a more adaptive approach to learning, but this work remains at an early stage.

In the case of the CSSF, we found significant ongoing activity to build learning capacity – partly prompted by an ICAI report in March 2018 that was critical of its approach to results management. The CSSF has recruited additional staff and contracted in external expertise. It has set up regional contracts to provide monitoring and evaluation support and enhance its internal capacity. It is upgrading its programme-level theories of change and focusing its results frameworks on measurable outcomes. It has also introduced new programme management tools. While much of this is still under development, it represents a significant investment in increased learning capacity. The CSSF also funds the cross-government Stabilisation Unit, which provides research and technical advice in support of UK aid in conflict settings, and Government Partnerships International, which works with other departments to provide peerto-peer support to public institutions in partner countries. Both these units have a strong learning orientation.

Box 4: Government Partnerships International (GPI)

GPI is funded through the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund, DFID’s Partnership for Development Programme and other UK government funds. It has existed in various guises for some years, most recently as the National School of Government International. It both delivers training and helps UK departments and agencies to provide peer-to-peer support to partner governments overseas. Given the UK government’s policy of showcasing UK expertise through the aid programme, GPI has helped to improve the ability of a number of departments and agencies (such as the Office for National Statistics and HMRC) to offer highquality knowledge-based assistance.

BEIS is currently the largest spender of UK ODA after DFID, with responsibility for a significant share of the UK’s International Climate Finance and two major research funds. We found mature learning processes for UK International Climate Finance, including:

- increased in-house capacity, particularly in its analyst team, with stronger oversight from senior managers

- a new strategy for strengthening MEL, with increased effort to synthesise evidence and share lessons between programmes and with external partners

- a programme for procuring external research (the Knowledge, Evidence and Engagement Programme)

- improvements in portfolio management, including clearer statements of expected results, key performance indicators and an operating manual.

However, these positive learning practices were not applied to the two BEIS-managed research funds, the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and the Newton Fund (NF). There have been improvements in the GCRF’s approach to performance management since our 2017 review. However, in June 2019 we awarded the Newton Fund a red score for learning, on the basis that, five years after its establishment, it had yet to develop a workable system for capturing development results at the portfolio level. BEIS has established a working group on results and is in the process of identifying key performance indicators. However, these will not be in place until the final year of the Fund’s operations, which leaves little space for learning.

Lower-spending departments do not require the same depth and complexity of learning mechanisms as the higher-spending departments or funds. Departments whose aid spending is more transactional (such as support costs for refugees in the UK by the Department for Education) may have no need for aid-specific learning processes. In such cases, we found that the limited learning needs were adequately met by current arrangements.

Some departments currently have small aid budgets but are actively building their aid-management capacity in order to access more ODA funding. Examples include the Department for International Trade which began spending ODA in 2018; the Office for National Statistics which plans to increase its ODA budget; and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) which has been exploring different modes of ODA delivery. Amongst this group, departments are investing in internal learning systems and processes, and learning from more experienced aid-spending departments. We identified a range of investments in working with information and data, developing knowledge and know-how, documenting lessons and developing networks to share learning. This is rightly recognised as part of demonstrating a capability to manage ODA. The process of bidding for more ODA funds has therefore proved to be a useful spur to learning.

Box 5: Department for International Trade (DIT)

DIT, one of the lower-level ODA-spending departments, is building its capacity in preparation to increase its ODA spending. It is engaging with both DFID and the FCO to learn from their experience. It produces quarterly updates (heat maps) on its emerging capability to manage its first two ODA programmes and identify risks. It has shared this self-assessment tool with other departments, including the Joint Funds Unit and DFID (which is considering how to include it in support for other departments). DIT has established an awareness training programme covering the legal framework, the UK aid strategy, transparency commitments, fraud, risk, programme delivery, safeguarding and media relationships. A number of other ODA-spending departments have also participated in this training.

Our findings show that investments in learning are broadly commensurate with the size and complexity of each department’s aid portfolios – even if these systems are not yet fully operational. However, we remain concerned that learning is often treated as a stand-alone activity or set of products produced to a predetermined timetable, without being properly integrated into the management of aid portfolios. The value of learning is ultimately around improved decision making. As DFID’s Smart Rules note:

“continuous learning and adapting is essential for UK aid to achieve maximum impact and value for money. It is important that learning is systematically planned, adequately resourced and acted on in ways that are strategic and can maximise results.”

A key outstanding challenge is therefore to ensure that whatever knowledge is being generated is actively used to inform management decisions in real time. Not all departments have given enough thought to which management processes should be informed by learning and which stakeholders need access to the knowledge, in order to tailor their learning processes accordingly. There is more work to be done in building a culture of evidence-based decision making, with a willingness to embrace failure as well as success as a key source of lessons. The ultimate goal of learning systems is not to meet an external good practice standard, but to make departments effective in the management of their aid portfolios.

Outsourced learning arrangements are not well integrated into aid management processes

In many instances, departments and funds have contracted out capacity for MEL to commercial providers. This can be an effective approach to overcoming internal capacity constraints and accessing technical expertise. Buying in these experienced providers has enabled the departments and funds to fill capacity gaps in the face of rapidly increasing aid budgets.

Departments are using these external providers in a variety of ways. They are providing support on ODA eligibility screening and introducing departments to programme management methods, some adapted from DFID guidance and good practice and some developed by MEL suppliers themselves. Given competing demands on officials’ time, the MEL suppliers increase the departments’ capacity to experiment and analyse the results. Internal cultures within government departments sometimes work against acknowledging and learning from failure; according to some key informants, an MEL contract can help create space for discussion of what has not worked and why by providing an arms-length perspective.

Outsourcing is also helping to join up learning across programmes, departments and funds. There is a relatively small pool of commercial firms providing these services, often to several departments. We saw examples of contractors sharing lessons internally.

The chief drawback of outsourced learning is that the knowledge may accumulate in commercial firms without being properly absorbed by the responsible departments or used to inform aid management decisions. In the most extreme examples of this, key elements of learning in MEL contracts were only developed after the programme or fund in question had already committed most of its expenditure. This was the case with both the GCRF and the Newton Fund. It was not clear how learning generated by the external provider could influence the ongoing development of the portfolio when most of the funds had already been allocated. In other cases (such as the Prosperity Fund), we see risks where institutional memory has been externalised and capacity built within a service provider at the expense of civil servants.

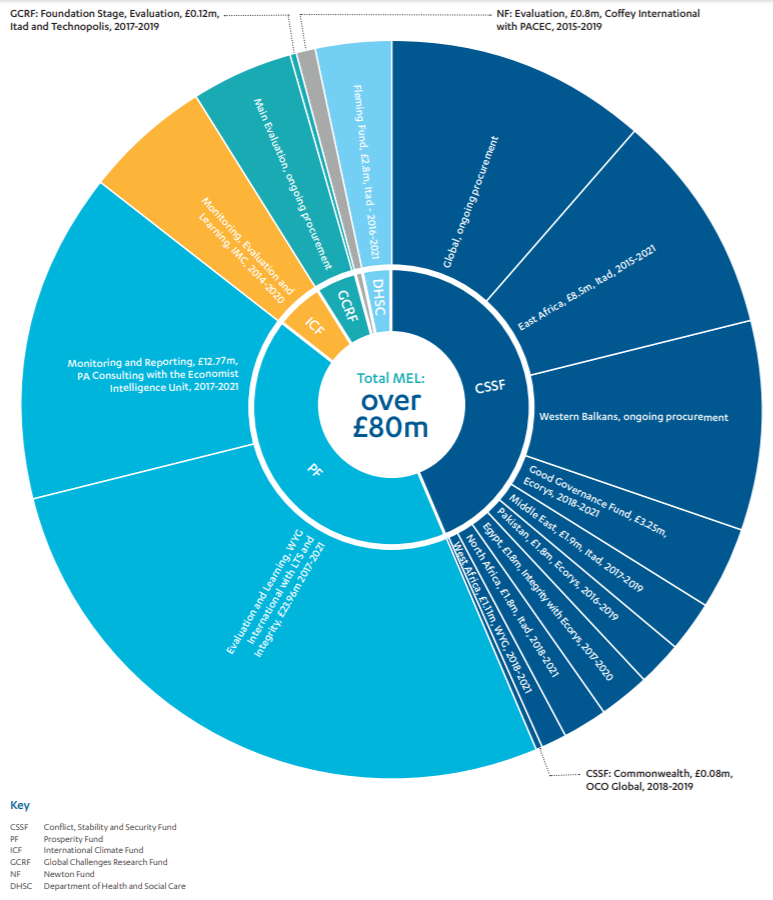

Looking across the MEL contracts that we have identified (see Figure 5), it is difficult to discern any clear rationale for the size and pattern of expenditure. Aid-spending departments obviously see a need to make substantial investments in learning but there is no consistency in how they have done so. The proliferation of MEL contracts has also led to duplication and overlap, not just between departments and funds, but also within them. For example, the CSSF has multiple contracts across different geographical and thematic areas, provided by a range of contractors. Having engaged its providers on a case-by-case basis, it is not clear to us that the CSSF is managing its MEL portfolio so as to extract the best value. Across government, there are no common rules or expectations for the outsourcing of MEL resources for aid portfolios and no oversight as to whether these outsourced contracts represent good value for money. Given that these departments and funds often work on overlapping topics and in the same geographies, there is a risk of duplication of data and analysis.

Figure 5: Externally outsourced monitoring, evaluation and learning contracts

Over £80 million is spent on outsourced monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) contracts. This chart displays the breakdown of the contracts across departments/funds and individual contracts. The inner circle shows the proportional amount of money spent on outsourced MEL by each respective department/fund. The outer circle provides details of the name, the value (where publicly available), the service provider and the dates of the contract.

Departments are drawing on their core technical expertise to inform their aid programmes

A potential benefit of involving more departments in delivering UK aid is the ability to draw on their core technical expertise. We found that this is happening, with significant exchange of learning between ODA and non-ODA activities within many departments. The FCO uses common programme management systems for both ODA and non-ODA funds (although it has created a separate ODA team that scrutinises whether funding is ODA-eligible). The CSSF provides the FCO with both ODA and non-ODA funding to support the implementation of National Security Council strategies, and both are informed by the FCO’s thematic expertise in areas such as the promotion of human rights and good governance. Other departments make a clearer distinction between ODA and non-ODA activities, while actively sharing expertise between the two areas of work. Examples include the Department of Health and Social Care, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and the Office for National Statistics (see Box 6).

Box 6: How departments are bringing their expertise to the support of UK aid

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) is accessing UK health expertise to inform its own ODA programmes and those delivered jointly with other departments. For example, the department tells us that it has drawn on the experience and expertise of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), which delivers research to support health and care in England. The NIHR Global Health Research programme aims to commission and support high-quality applied health research in low- and middle-income countries. Building on the NIHR principles of Impact, Excellence, Effectiveness, Inclusion and Collaboration, the programme strengthens global health research capability and training through equitable partnerships. In one example, experienced NIHR researchers from Manchester are working in partnership with researchers and community workers in Kenya and Tanzania to reduce the number of stillbirths. The UK researchers shared their know-how and helped combine their UK experience with that of local practitioners and communities to support stillbirth prevention and care in low-resource settings. DFID has also drawn on NIHR’s track record of commissioning high-quality research to inform its own health research.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) is also drawing on UK experience to help DFID and other aid-spending departments. In our review of the UK’s International Climate Finance, we saw examples in the areas of environmental planning and marine protection and in promoting the idea of ‘natural capital’, which brings an understanding of the value of nature into economic assessments. DHSC has requested Defra’s help on its international work on animal health and zoonotic diseases.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) informs us that it is developing peer-to-peer partnerships with statistical institutes in developing countries, including by pairing its own experts with professionals in the partner country. The learning is going both ways: returning experts share their experience with colleagues,and this in turn is reportedly informing the ONS culture and its approach to challenges in the UK.

While departments bringing their expertise to bear on ODA programming is a positive finding, we note that it may not be necessary to allocate ODA resources to departments in order to achieve this result. Other methods of drawing on their expertise could be devised.

How effectively is learning shared across aid-spending departments and used to improve the effectiveness and value for money of aid?

There is a good level of exchange of learning between aid-spending departments

While each department has gone about building a knowledge of effective development cooperation in its own way, we have found many positive examples of the exchange of learning between departments.

In past reports, ICAI has noted many instances of departments working together to shape the UK aid response to global crises. The joint effort to strengthen the international health crisis response system in the wake of the 2013-16 West Africa Ebola epidemic stood out as a strong example. We have also seen examples of departments seeking out expertise across government. For instance, the BEIS International Climate Finance team drew on CSSF expertise of working in conflict-affected environments when developing the business case for addressing deforestation in Colombia. We have also seen examples of departments that bid for ODA funds in the 2019 Spending Review, such as DIT, learning from other departments with established aid programmes.

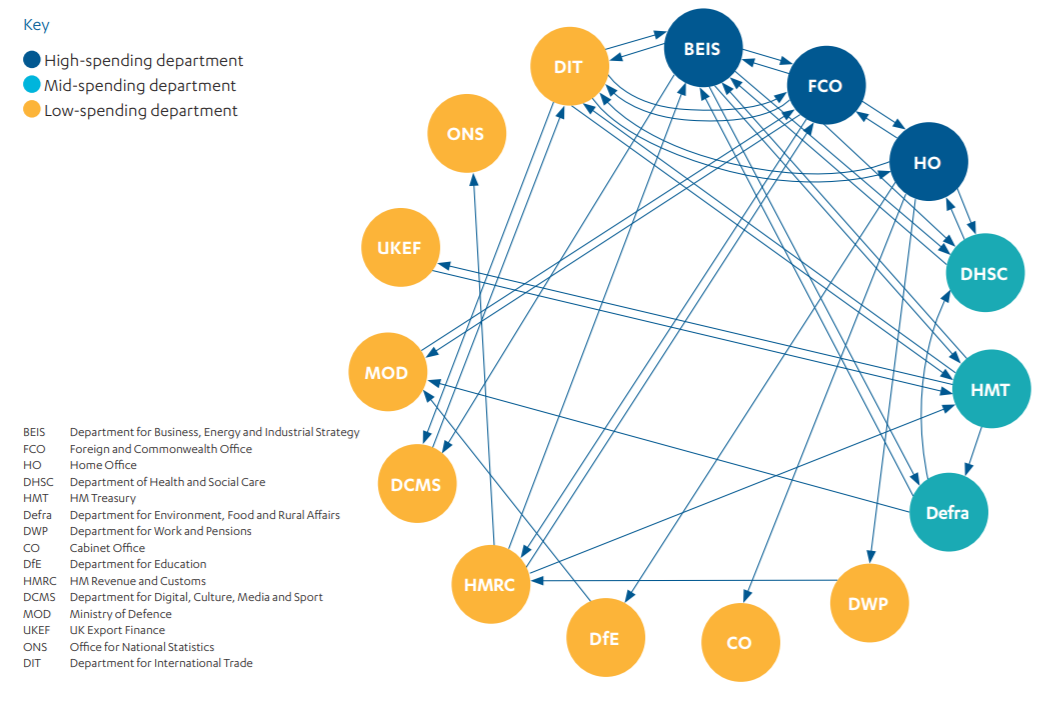

Figure 6 maps the learning interactions between departments that were mentioned in our interviews (leaving interactions with DFID, which are discussed under question 3). While not a comprehensive list, this provides an indication of the complexity and range of learning interactions taking place.

A set of cross-government learning networks are beginning to emerge

The UK government is beginning to put in place some high-level, cross-government structures to oversee the UK aid programme. The National Security Council sets the UK’s strategies, priorities and policy direction for external engagement across the fields of security, diplomacy, trade and development cooperation. It provides direction to the two cross-government funds: the CSSF and the Prosperity Fund. It has established cross-departmental groups to support the implementation of National Security Council thematic objectives. There is a Senior Officials Group on ODA, which is co-chaired by HM Treasury and DFID and meets at director level. While its initial mandate was to ensure that the 0.7% of gross national income spending commitment was met, its remit was widened in 2018 to include coherence and strategic guidance.

A cross-government architecture for learning is also beginning to emerge. Many of the key informants we interviewed recognised the importance of cross-government learning. There has been a proliferation of groups and forums where learning is being exchanged on thematic issues. Examples include the Strategic Coordination of Research (SCOR) Board, which was put in place in response to ICAI’s 2017 report on the GCRF, the Global Health Oversight Group, and the Cross-Whitehall Safeguarding Group. There are also learning networks whose remit is broader than aid, such as the Chief Scientific Advisers’ Network.

Recently, new groups have been established for sharing learning about aid management, including a Cross-Government Evaluation Group. There is an ODA Commercial Oversight Group where commercial directors convene to explore procurement and commercial issues, supported by a Commercial WorkingLevel Group (with representatives from DFID, the FCO, the Home Office, BEIS, DIT and DHSC) and a Cross-Whitehall Financial Instruments Knowledge Network. We are also aware of networks that have emerged to share experience on thematic or technical issues, such as urban development, global health research, modern slavery and the mobilisation of private finance. Most of these groups are still being established, but interviewees believed they would provide valuable spaces for learning and collaboration.

Figure 6: Complexity of learning interactions between government departments

Figure 6 shows the complexity of learning interactions between aid-spending departments other than DFID. The lines show only the learning interactions that were mentioned in our interviews and are indicative only. See the individual department pages in the Annex for more detail.

Peer-to-peer exchange among professionals can be one of the most effective methods of learning. Communities of practice have developed across government among staff performing similar tasks in support of UK aid to share learning and develop relationships. We found examples of tax and public financial management, economics, gender economics and families, and monitoring and evaluation. Many were initiated by DFID staff. They are mostly at an early stage, consisting of email lists of interested individuals and sometimes online platforms for discussion and sharing materials. They are a good start but will need further investment to become effective.

Another mechanism for joining up is technical professional groups (for example on infrastructure, evaluation or climate change). Members of professions are accredited as having particular skills or expertise. They can be useful agents for exchange of learning and promoting common standards across departments. DFID itself organises its advisory staff into 13 such groups, called cadres, each run by a head of profession. It has offered cadre accreditation to other departments, and some departments, such as FCO, are in the processes of establishing professional groups of their own. Some formal professional groups exist right across government, for instance for economics and statistics, as do looser technical groups on issues such as infrastructure, evaluation, climate and environment. Developing common technical qualifications across aid-spending departments would be potentially useful for promoting common standards and practices.

Co-location within countries facilitates exchange of learning across departments

From our own observations, and from the evidence gathered, shared learning happens most readily among UK government representatives within developing countries, close to the frontline of aid delivery. Stakeholders were in agreement that co-location of government departments in UK missions facilitates learning, collaboration and coherence. This echoes findings from past ICAI reviews.

Our interviews with officials in Pakistan and Kenya suggest that departmental representatives abroad tend to act and learn as one team – especially where senior staff champion joined-up working. In Kenya, the CSSF has run workshops with the FCO and the Ministry of Defence (MOD) to identify scope for management efficiencies in aid programmes. It is also working with DFID to deliver joint training to colleagues from different departments.

Joint working on external relations has long been an objective of the UK government, promoted through the One HMG Overseas initiative and more recently through the Fusion Doctrine (see Box 7). However, it is an ambitious agenda, given the different cultures and priorities of departments. To succeed, it will need a more active approach to the exchange of learning across departments. It is also a resource-intensive process. Staff in Pakistan and Kenya reflected that home departments in London do not always appreciate the time required to support One HMG working.

Box 7: Cross-government measures to improve joint working abroad

One HMG Overseas: Since 2011, the One HMG Overseas initiative has sought to remove barriers to joint working among departmental staff based in British diplomatic posts overseas, so that the government can deliver on its objectives more effectively and efficiently. As the NAO noted in 2015, “Given the many partners and disparate objectives of those involved, this has been and remains an ambitious agenda, requiring considerable culture change.”

Fusion Doctrine: The Fusion Doctrine was introduced in the National Security Capability Review 2018 as an initiative to harness together the tools for external engagement – security, diplomacy and economic engagement – in support of a common set of objectives. It builds on the creation of the National Security Council in 2010 to strengthen the delivery of the UK’s international objectives. Its aim is to drive forward and support a ‘whole of government’ approach to national security, bringing out improvements in accountability and efficiency. The government is in the process of implementing groups for particular geographical areas and thematic objectives, under the National Security Secretariat.

The cross-government architecture for learning about aid is not yet mature

While our findings show a growing network of links across the aid programme, many of these structures are new and yet to be fully operational. The system has grown organically, without conscious design and with no single body responsible for overseeing it. Its ad hoc nature means that learning across the UK aid programme is still unstructured, with inevitable gaps and overlaps.

There have been efforts to improve coordination across the UK government since the 1990s, if not earlier. One review of the experience identifies a number of success factors: most notably, a clear central mandate for joint working and a strong and supportive architecture that encourages innovation and cooperation.

For the time being, the mandate for joint working is still not sufficiently clear. The requirement for joint learning and basic principles for how this should occur have not been set out, nor is there currently a clear architecture to support joint learning. As the International Development Committee recently observed:

“There is a conundrum in any joined-up or cross-government working, which is the balance between the opportunity of benefitting from different views and new skills and expertise and the risks of strategic incoherence, duplication and other unintended consequences.”

More guidance is needed to help departments get this balance right.

The UK aid programme lacks an agreed standard for publication of aid data

Transparency is recognised in the UK aid strategy as a driver of value for money. Transparency improves the accountability of aid-spending departments, both to UK taxpayers and to citizens in partner countries. It is also a key facilitator of cross-government learning.

In June 2010, the UK government introduced an ‘Aid Transparency Guarantee’, with a commitment to publishing detailed information about DFID programmes, using the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) standard. It committed to requiring all recipients of UK funding to publish their data to the IATI standard, and also to encouraging other donors to do so. First launched in 2008, IATI initially focused on the transparency of development funding and has since been broadened to cover development results.

“Aid transparency is critical to improving the effectiveness and value for money of aid. Making information about aid spending easier to access, use and understand means that UK taxpayers and citizens in poor countries can more easily hold DFID and recipient governments to account for using aid money wisely. Transparency creates better feedback from beneficiaries to donors and taxpayers, and helps us better understand what works and what doesn’t. It also helps reduce waste and the opportunities for fraud and corruption.”

UK Aid Transparency Guarantee, DFID, 3 June 2010.

Progress by donors on publishing their data to the IATI standard is assessed in the Aid Transparency Index, an annual publication by the non-governmental organisation Publish What You Fund. By 2015, DFID was rated in the index as ‘very good’, making it a global leader on transparency. The aid strategy included a new commitment that all other aid-spending departments would be ranked as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ on the index by 2020. On the recommendation of the International Development Committee, the government has commissioned Publish What You Fund to report on progress against this commitment, with an initial assessment due in December 2019. DFID has established a working group on transparency and provides technical and financial advice support to other departments.

So far, progress is mixed across the departments. Some have yet to generate expenditure data in the right format. BEIS, DCMS, Defra, DHSC, FCO, ONS, MOD and DIT are all publishing at least some of their data to the IATI standard, but DWP, DfE, HM Treasury, HMRC, UKEF and the Cabinet Office are yet to do so. DFID has created an online tool, DevTracker, that summarises data published by any UK government department – and some implementing partners – to the IATI standard. This tool is able to produce convenient summaries of UK aid by country, sector or spending department, although for the time being the data on non-DFID expenditure is incomplete (see Figure 7).

Surprisingly, in interviews conducted for this review, some departments argued that the commitment to transparency in the aid strategy was general in nature, requiring aid-spending departments to include basic information on their departmental website, but leaving them discretion as to which data to publish. For instance, the CSSF and the Prosperity Fund currently only publish a selection of portfolio and programme data on their respective websites.

In addition to expenditure data, DFID publishes its main programme documents, including business cases, annual reports and programme completion reports, on DevTracker. Most other departments are not doing so. These documents summarise the progress of each programme towards its intended results and include DFID’s programme performance scores. This is an important contribution to transparency, which also facilitates the sharing of learning across government and with external stakeholders by making performance data accessible via internet search engines. There is no overarching requirement for aidspending departments to publish programme documents, progress reports or learning products.

Aid-spending departments lack access to each other’s learning platforms

Some departments have made progress on building information platforms to capture data on aid expenditure and/or lessons learned on good development cooperation, for their own internal purposes. However, many of these systems are not accessible to other departments or to the public, which inhibits the sharing of learning.

DFID’s Aid Management Platform (AMP) presents and analyses data on expenditure and programming from its management information system, to support management decision making at programme and portfolio level. While DFID has been promoting AMP to other departments, it was not designed to be a common platform and other departments cannot use it without additional technical investment.

Other departments are also pressing ahead with developing technical learning platforms. The Prosperity Fund’s Learning Platform is a strong example (see Box 8). The Home Office has a knowledge platform on modern slavery (known as Delta 8.7), while there is a knowledge platform for UK International Climate Finance that aggregates results across multiple programmes and funding streams.

However, these platforms are not being shared. While we acknowledge that, for some departments, confidentiality and security requirements preclude the sharing of some information, there is nonetheless scope to improve information sharing within and across departments.

Figure 7: Use of technical platforms across ODA spending departments/funds

Box 8: The Prosperity Fund’s Learning Platform

The Prosperity Fund has invested in the development of its own information system, the PF Learning Platform, which went live in October 2018. It is designed to respond dynamically to learning needs and link people together with interests in topics such as transparency, procurement and economics. While still at an early stage, this platform stands out as a strong example of using technology to enhance learning, at a time when legacy technical systems are standing in the way of effective sharing of information and knowledge. It incorporates:

- Learning networks on thematic areas, responding to interest expressed by stakeholders. There are networks on commercial issues, gender and inclusion, and a planned network on achieving benefits to the UK (‘secondary benefits’).

- Learning forums and pop-ups, which allow participants to access expert advice face to face or via teleconference/webinar, and which support discussions on areas of common interest across programme teams.

- A library of evaluation reports, thematic guidance and other outputs.

As of March 2019, the Platform had acquired 478 users across departments, including a growing group of ‘super users’ who have logged on 20 times or more.

How well does DFID support learning across government?

DFID provides extensive support to other departments

Under UK government rules, each department is accountable for its own expenditure. While DFID is given the role under the UK aid strategy of supporting other departments with their aid spending, it has no mandate to oversee their work or to enforce good practice standards. Nor was it provided with any additional staffing resources for this support function.

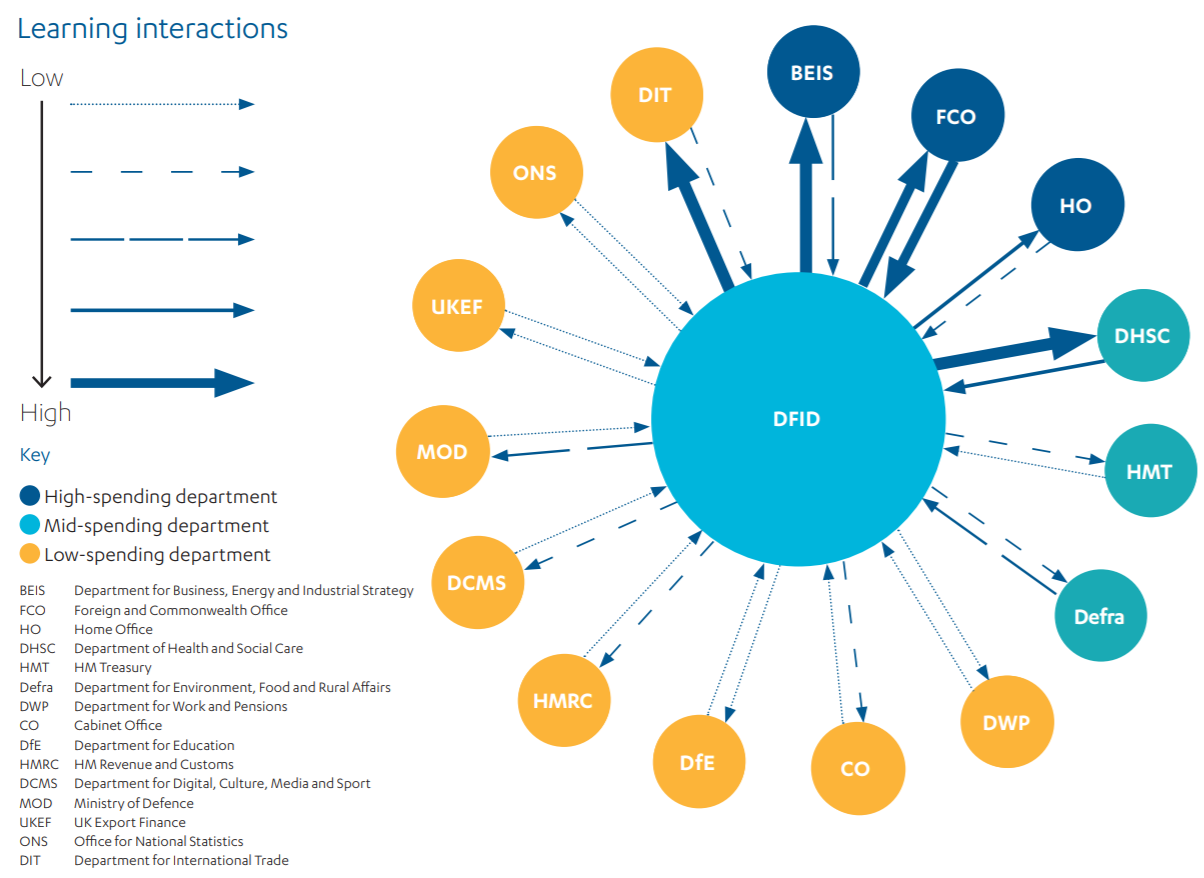

Despite these constraints, we find that DFID plays an important role in supporting aid-spending departments. Figure 8 maps the instances of such support that we encountered. It shows that DFID has provided help to every aid-spending department. It also shows that other departments have provided DFID with technical advice and support.

Figure 8: Support for learning interactions between DFID and other aid-spending departments

Figure 8 gives an indication of learning interactions between DFID and other aid spending departments. The lines are weighted to show the density of interactions mentioned in our interviews and are indicative only. See the individual department pages in the Annex for more detail.

Figure 8 shows that DFID’s support has gone far beyond peer-to-peer exchanges of information and learning. For example, DFID requires its advisers to devote 10% of their time to providing support to programmes beyond their direct responsibility, in areas such as design, procurement, annual reviews and evaluations. Some of this support has been extended to other departments, although we are informed that it is not always available and can in practice be difficult to access.

Figure 9: Examples of support offered by the Department for International Development to other departments

Most departments have welcomed DFID’s support, recognising its important role as a repository of expertise on aid management. We fully agree with the conclusions of the International Development Committee in June 2018, that:

“DFID has a crucial role to play in ensuring that all other government departments understand how to administer ODA programmes effectively and efficiently, including programme management and reporting, and highlighting when required administration standards are not being met.”

Other departments are also helping DFID to learn

Importantly, the exchange of learning between DFID and other departments goes in both directions. We came across a range of examples where cross-government technical expertise was drawn on to raise the quality of DFID programming. For example, DFID has drawn on DHSC’s expertise on health systems research and vaccine development.

Secondments and staff transfers across departments have proved to be an important mechanism for sharing learning. DFID has over 100 staff currently on loan to other departments. On their return to DFID, they bring new experiences and knowledge, as well as stronger personal networks to facilitate ongoing exchange of learning.

No additional resources have been given to DFID to support learning across government

Supporting other departments with their aid expenditure is a time-consuming process. While DFID’s overall budget has continued to grow in absolute terms since the 2015 aid strategy, the department has operated under tight headcount constraints. This means that time spent supporting other departments detracts from DFID’s capacity to manage its own aid budget.

Furthermore, DFID staff told us that UK government financial rules made the charging of other departments for knowledge-based services difficult. For example, DFID has offered its EQUALS programme (an outsourced monitoring and evaluation facility) to other departments. While these departments are required to pay for the support they use, DFID would need to go through a new programme approval process in order to include the additional funds in the EQUALS budget.

As a result, DFID has struggled to meet the demand from other departments for support. We were told that the resourcing of such support was a concern for DFID in the recent Spending Review.

Conclusions and recommendations

Conclusions

The UK government’s decision to increase the number of departments involved in spending UK aid created a substantial organisational challenge. As noted in a number of ICAI reviews, some departments saw rapid increases in their aid budgets before the necessary systems and capacities were in place, entailing significant short-term value for money risks.

The 2015 aid strategy required all aid-spending departments to achieve international best practice in their management of aid. The government has also set the objective of improving joint working across aid-spending departments and between the aid programme and other tools of external influence. This has created major learning challenges, both within and between departments.

It is striking that the UK government did not give more consideration to how new aid-spending departments would acquire the necessary learning, and what additional support they would need.

Our findings nonetheless show that departments are making significant investments in learning. With a few gaps, these investments are commensurate with the size and complexity of their aid budgets. We have also seen many initiatives to share learning between aid-spending departments. However, departments are at different points on this journey and many of the new systems for generating and exchanging learning are not yet fully operational. The learning assessment framework that ICAI developed for this review is intended to help them assess their learning needs and monitor their progress.

DFID is providing a good range of support to other departments. However, it lacks a clear mandate to set and enforce good practice standards across the UK aid programme, and is not resourced to provide adequate support across the many aid-spending departments and funds. If the UK’s status as a ‘development superpower’ rests on the quality and integrity of the aid programme, as well as the size of the aid budget, then this is a significant gap. While a diversity of knowledge and approaches across aidspending departments may be a source of strength, it should be accompanied by a clear commitment to share learning on good development cooperation. Without a shared understanding of what good looks like, there is a danger that a fragmented aid programme will lose coherence and quality.

It is telling that departments that bid for aid resources as part of the 2019 Spending Review are among the most active in building learning systems and engaging with more experienced departments. This competitive pressure creates healthy incentives for rapid learning. We offer the following recommendations to enhance and extend these incentives.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1:

DFID should be properly mandated and resourced to support learning on good development practice across aid-spending departments.

Problem statements:

- DFID has a crucial role to play in ODA learning as a repository of expertise on aid management. Other departments welcome its support.

- While DFID is given the role under the UK aid strategy of supporting other departments with their aid spending, it has no mandate to oversee their work or to police good practice standards.

- Providing support to other departments has resource implications for DFID.

- DFID has not been able to meet the current demand for assistance from other departments.

Recommendation 2:

As part of any Spending Review process, HM Treasury should require departments bidding for aid resources to provide evidence of their investment in learning systems and processes.

Problem statements:

- It is not clear that the allocation of ODA across departments takes into account aid management capacity – particularly as the size and complexity of ODA spending varies in each department. Aid-spending departments lack strong incentives to be best in class in aid management.

Recommendation 3:

The Senior Officials Group should mandate a review and, if necessary, a rationalisation of major monitoring, evaluation and learning contracts, and ensure that they are resourced at an appropriate level.

Problem statements:

- While outsourced monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) services are part of the solution to overcoming capacity constraints on aid management, there is currently no clear rationale for the shape or size of MEL contracts.

- The proliferation of MEL contracts has created risks of overlaps and duplication, potentially compromising value for money.

Recommendation 4:

Where aid-spending departments develop knowledge management platforms and information systems to support learning on development aid, they should ensure that these systems are accessible to other departments and, where possible, to the public, to support transparency and sharing of learning.

Problem statements:

- At present, technical platforms to support aid expenditure do not easily exchange information/ learning across government – or in some cases within departments.

- A number of departments are still a long way from meeting UK government commitments on the transparency of UK aid.

- There is no requirement in the 2015 aid strategy to publish information on learning which leaves discretion to departments to decide what to put in the public domain.

- At present, technical platforms for supporting aid expenditure do not easily exchange information/learning across government in a format all staff can read – or in some cases within departments.

- Incompatible systems between departments (particularly when co-located in UK overseas missions) are an obstacle to learning and effective collaboration on development cooperation.

Annexes

This Annex contains one-page overviews of each official development assistance (ODA)-spending department and fund. The intention is to have a consistent approach to the summary information while respecting that each department and fund has a different level and complexity of spend. Each overview contains at least four sections:

- key facts/details of ODA spending and resources

- summary or general overview

- working groups and other cross-government engagements

- key insights.

To assist in this process, in addition to the assessment framework described in paragraph 2.2, we have created a form of classification which reflects the learning that is relevant for the different departments.

Two important distinctions have been identified that cannot be looked at in isolation from each other: the size of ODA spending and its nature. The size of a department’s spending is determined as the total amount spent over the financial years 2016-18. This categorisation of departments according to their level of ODA spending was developed for the sole purpose of this review.

Size of spending:

- High-level spender (£500 million and above): We expect a significant depth and complexity of learning that has in place an effective process of working with information and data, encourages the ongoing development of knowledge and know-how, and continues to maintain the necessary network of relationships for sharing the learning. Departments in this category include BEIS (GCRF and Newton Fund), ICF, FCO, CSSF, Prosperity Fund and the Home Office.

- Mid-level spender (£100-500 million): We expect the learning at this level of ODA spending to span all elements of learning, from supporting a process of working with information and data to the ongoing development of knowledge and know-how, and the maintenance of a network to share the learning. However, the depth and complexity can be less than for the high-level spenders. Departments in this category include DHSC, Defra, HM Treasury and HMRC.

- Low-level spender (up to £100 million): The departments at this level of spending can vary significantly in the depth and complexity of their learning. The nature of the ODA spending has a particularly strong influence on each department’s need to manage information and data, develop knowledge and know-how, and maintain the necessary network of relationships in place to share the learning. Departments in this category include DIT, ONS, DCMS, UKEF, DWP, DfE and MOD.

Nature of the spending:

- Transactional: In terms of learning, these departments are focused primarily on working with specific data and information, with limited contact with other departments. Departments in this category are UKEF, DWP and DfE.

- Scaling up: Current low-level ODA-spending departments which plan to increase their spending significantly or try to establish a new fund are considered to be scaling up their learning work to align with a higher spending level. They are beginning the necessary process of working with information and data, developing knowledge and know-how, and setting up the necessary network of relationships to share the learning. Departments in this category are DIT, ONS and DCMS.

- Mixed portfolio/programme: The spending tends to combine a variety of elements within a department’s portfolio. This can include programme delivery, policy programmes, research programmes, transactional spending (including retrofitting), administrative costs and so on.

**Please see pdf version of this review for the full annex.