The current state of UK aid: A synthesis of ICAI findings from 2015 to 2019

Foreward

As ICAI transitions to a new team of commissioners, we have prepared an assessment of the state of UK aid and the challenges ahead for international development. Drawing together findings from our past four years of reviews, we assess the readiness of UK aid to respond to these challenges.

This analysis will help shape ICAI’s review programme for the next four years. We also hope that it will inform the government’s future plans and priorities for the aid portfolio, as well as providing a timely perspective for Parliament and taxpayers on the value of UK aid.

Our reviews have highlighted major contributions by UK aid to global development challenges and the Sustainable Development Goals. For example, the UK has shown clear leadership on the ‘leave no one behind’ principle, in strengthening the international response to challenges such as Ebola and climate change, and in tackling violence against women and girls. At its best, UK aid continues to be world-leading.

But we have also found shortcomings. We criticised aid programmes for their failure to prioritise building sustainable public services, for inadequate monitoring and evaluation, and for lapses against the ‘do no harm’ principle in conflict zones. We highlighted weaknesses in DFID’s funding of civil society organisations and in its use of ‘payment by results’ for multilateral organisations.

In recent years we have seen a dramatic scaling up of aid spending by a number of departments and cross-government funds – often before the necessary systems, processes and capabilities were in place. We devoted a series of reviews to ensuring that proper aid management practices were observed, and this will continue to be a focus.

One of the most rewarding parts of our work comes when we revisited problem areas, to assess action on our recommendations. We have found progress in a wide range of areas, and many examples of our reviews touching off wider learning processes. This underlines the importance of robust and independent scrutiny and accountability.

But we aren’t complacent. Like UK aid itself, we are constantly trying to improve the impact of our work. Innovations include the introduction of unscored ‘rapid reviews’, to provide early feedback on emerging challenges. We have also conducted an online public consultation, to help focus our work in the coming four years on issues that resonate with the general public and stakeholders in the aid sector.

As we say farewell to our retiring commissioners, Tina Fahm and Richard Gledhill, and to the previous chief commissioner, Alison Evans, who left ICAI to take over the Independent Evaluation Group in the World Bank Group in December, we welcome two new commissioners, Sir Hugh Bayley and Tarek Rouchdy. The important work of independent scrutiny continues.

Introduction

Over the period from 2015 to 2019, ICAI has accumulated a rich body of findings on the performance of UK aid. We have produced 28 reviews, four annual follow-up reports and a number of other products (see Table 1). As ICAI hands over to a new team of commissioners, this report draws out key findings and themes from across this body of work, exploring how well UK aid has delivered in its main areas of activity.

The 2015-19 period has been a dynamic one for UK aid. The Sustainable Development Goals have reshaped the global development agenda. The UK has mounted its largest ever humanitarian operation in response to the Syria crisis, and UK aid has responded to a range of other global challenges, from Ebola to the growing threat of climate change. Within the UK, more departments have taken on a role in spending aid, as the aid programme has become more integrated into the UK’s machinery for external engagement.

Looking ahead, UK aid will continue to evolve rapidly, in response to a dynamic global context and new UK priorities. The government has pledged to put development “at the heart of our international agenda”, while making sure that the aid programme serves to enhance the UK’s global influence and interests. This review explores how well equipped the aid programme is to respond to the challenges ahead, and the opportunities and risks associated with the changing functions of UK aid. As well as being of interest to policymakers and other stakeholders, this assessment will inform ICAI’s future selection of reviews.

In preparing this report, we have:

- synthesised findings from selected reports and annual follow ups in the 2015-19 period

- reviewed literature and data on current trends in international development

- explored the results of UK government strategic planning processes that affect the aid

programme - drawn on the results of an online public consultation on ICAI review topics and products

- consulted with stakeholders from government, academia, the think tank community and civil

society, including through four round tables.

The report is structured as follows: Chapter 2 surveys the changing global development context and looks at changes in the policy and institutional architecture of UK aid. Chapter 3 presents the results of our synthesis of ICAI’s 2015-19 reviews under five themes: leaving no one behind, jobs and economic transformation, conflict and crisis, global threats, and the changing profile of UK aid. Chapter 4 summarises the results of our public consultation, while the final chapter draws out key themes and issues for ICAI’s future work.

| Review topic | Review type | Score |

|---|---|---|

| DFID’s efforts to eliminate violence against women and girls (2016) | Learning | Green |

| Assessing DFID’s results in water, sanitation and hygiene (2016) | Impact | Green/Amber |

| DFID’s approach to managing fiduciary risk in conflict-affected environments (2016) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| UK aid’s contribution to tackling tax avoidance and evasion (2016) | Learning | Amber/Red |

| When aid relationships change: DFID’s approach to managing exit and transition in its development partnerships | Performance | Amber/Red |

| Accessing, staying and succeeding in basic education: UK aid’s support to marginalised girls (2016) | Performance | Amber/Red |

| The effects of DFID’s cash transfer programmes on poverty and vulnerability (2017) | Impact | Green/Amber |

| The cross-government Prosperity Fund (2017) | Rapid | Not scored |

| The UK’s aid response to irregular migration in the central Mediterranean (2017) | Rapid | Not scored |

| UK aid in a conflict-affected country: Reducing conflict and fragility in Somalia (2017) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| DFID’s approach to supporting inclusive growth in Africa (2017) | Learning | Green/Amber |

| The Global Challenges Research Fund (2017) | Rapid | Not scored |

| Achieving value for money through procurement Part 1: DFID’s approach to its supplier market (2017) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| The UK aid response to global health threats (2018) | Learning | Green/Amber |

| DFID’s approach to value for money in programme and portfolio management (2018) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| Building resilience to natural disasters (2018) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund’s aid spending (2018) | Performance | Amber/Red |

| DFID’s approach to disability in development (2018) | Rapid | Not scored |

| The UK’s humanitarian support to Syria (2018) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| DFID’s governance work in Nepal and Uganda (2018) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| Achieving value for money through procurement Part 2: DFID’s approach to value for money through tendering and contract management (2018) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments (2018) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| DFID’s contribution to improving maternal health (2018) | Impact | Amber/Red |

| The UK’s approach to funding the UN humanitarian system (2018) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| International climate finance: UK aid for low-carbon development (2019) | Performance | Green/Amber |

| CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states (2019) | Performance | Amber/Red |

| DFID’s partnerships with civil society organisations (2019) | Performance | Amber/Red |

| The Newton Fund (2019) | Performance | Amber/Red |

| Four annual follow-up reviews, 2016-19 | Follow-up | Not scored |

| UK aid in a changing world: implications for ICAI (2016) | Information Note | Not scored |

| The 2015 ODA allocation process (2015) | Information Note | Not scored |

| An information note for the International Development Committee’s inquiry into the definition and administration of official development assistance (2018) | Information Note | Not scored |

The global and UK development contexts

In this chapter, we explore challenges in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, in the face of rapid changes in the global context. We draw on a range of horizon-scanning by other authors, distilled here into a number of key challenges for UK aid to respond to in the coming years.

Global poverty reduction is slowing

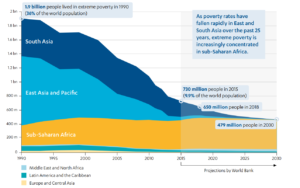

The last few decades have seen dramatic falls in global poverty, with more than a billion people lifted out of poverty since 1990. There are now estimated to be around 650 million people, or 8.6% of the world’s population, living in extreme poverty in 2015 – down from 1.85 billion in 1990.

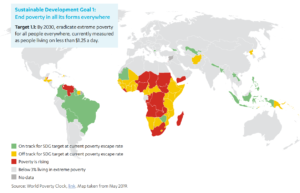

However, progress towards the SDG pledge of zero extreme poverty by 2030 has slowed. Only 20 million people are forecast to exit poverty in 2019 – well short of the rate of progress required to achieve zero poverty. The absolute number of people living in extreme poverty is still rising in 14 countries (see Figure 2), as a result of high population growth.

The reductions in extreme poverty have left large numbers living only just above the poverty line. Around 1.6 billion live in ‘multidimensional poverty’, without adequate access to basic services, and many are vulnerable to falling back into extreme poverty as a result of shocks such as medical emergencies, food price rises or extreme weather.

Looking towards the ‘last mile’ of delivering the SDG poverty target, the nature of the challenge will be qualitatively different. The poverty that remains is deeper, with more people living further below the poverty line and in circumstances that make them harder to reach. As poverty rates in Asia fall, extreme poverty is increasingly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa. Of 26 countries with more than 40% of the population below the poverty line, all but two (Haiti and Bangladesh) are in Africa. By 2030, Africa will account for 87% of the world’s extreme poor.

There are also substantial numbers of poor people living in middle-income countries that have yet to experience the benefits of economic growth. Inequality, exclusion and marginalisation are emerging as key challenges, calling for more focus on inclusive patterns of growth.

Poverty is increasingly linked to conflict and governance failures. In 2015, 513 million people in extreme poverty were living in fragile contexts. This number is expected to rise to 620 million people by 2030, accounting for 80% of the world’s poor. The accelerating impacts of climate change will also be a major influence on global poverty, with the potential to push large numbers of vulnerable people back into poverty.

Figure 1: Regional distribution of extreme poverty, with projections to 2030

Figure 2: Global poverty map, May 2019

Economic growth is not delivering enough jobs in the poorest countries

The SDGs recognise that eradicating extreme poverty by 2030 will require high, sustained and inclusive economic growth. In particular, more and better-paid jobs will be an essential element in lifting people out of poverty at scale.

In recent decades, global trade has been an engine of poverty reduction, creating millions of manufacturing jobs in China and other countries. This pattern may not be replicable in Africa. Africa has enjoyed strong economic growth over the past two decades, linked to widespread improvements in economic management, high global demand for its natural resources and a growing middle-class consumer market.14 However, growth has been concentrated in a few sectors and geographical areas, and has not translated into job creation at anything like the scale seen in Asia. Manufacturing has in fact declined as a share of output and employment. Given the signs of a slowdown in the globalisation of trade, it is unlikely that Africa will replace East Asia as the workshop of global manufacturing.

Africa’s potential may instead lie in ‘industries without smokestacks’, including agricultural industries and services such as tourism, telecommunications and computing. African countries, which include some of the world’s fastest growing, are demonstrating their potential for horticultural exports and a nascent IT sector. While there are still formidable barriers to overcome, including deep infrastructure deficits, skills gaps and persistent governance problems, there are also grounds for optimism over the long term.

In the short term, however, Africa faces a race against time. With the highest population growth of any continent, 28 countries will see their populations double between 2015 and 2050. With over 90 million labour market entrants over the next decade, African economies will need to create 18 million new jobs per year. At present, they are creating just 3.7 million. This is a matter of acute concern to African policymakers, who fear that youth unemployment will become a driver of social and political instability.

Conflict and crises are drivers of global poverty

Around the world, 1.8 billion people live in conflict-affected places and this number is projected to grow to 2.3 billion by 2030, including 80% of the world’s poorest. Climate change will exacerbate conflict, as water resources and arable land become scarcer.

Conflict and extreme poverty are mutually reinforcing. Conflict disrupts public services, suppresses trade and investment, weakens institutions and degrades human and physical capital. The effects spill across national borders, creating regional conflict traps that are difficult for individual countries to escape. From Yemen to northern Nigeria, an ‘arc of instability’ has emerged, causing famine and mass

displacement.

Refugees are a growing burden for developing countries. In 2017, there were 20 million refugees around the world – the largest number since the end of the Cold War. This burden falls principally upon developing countries, many of which are also fragile. The world’s top ten refugee-hosting countries include Pakistan (1.3 million), Iran (979,000), Uganda (940,000), Ethiopia (791,000), the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Kenya (451,000 each).

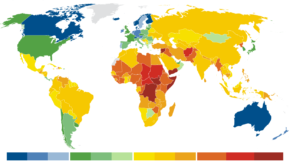

Figure 3: Fragile states index 2019

The Fragile States Index is an annual ranking of 178 countries based on the range and severity of pressures they face that impact on their level of fragility. Countries are ranked in order, based on an aggregate of 12 indicators, measures and long-term trends. The colours in the map indicate each country’s position in the ranking, in 12 bands.

As a result of major crises in Syria, Yemen, Iraq and South Sudan, global humanitarian need absorbs a growing proportion of global aid (see Figure 4). Three-quarters goes to countries in protracted crises, and humanitarian support for these countries is growing faster than development aid. There is consensus on the need to rebalance resources from repeated emergency response towards addressing the long-term drivers of conflict and fragility, but the practical challenges in doing so have proved considerable.

Figure 4: Trends in global humanitarian expenditure, 2007 to 2017

Humanitarian assistance increased sharply from 2013 and continues to account for a growing proportion of global aid flows.

Global threats are consuming a growing share of aid resources

A key role for development assistance is tackling challenges that present risks for both developing and donor countries – from climate change to global health threats, violent extremism, crime and illicit financial flows.

The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC24 warns of the dire consequences of climate change for developing countries. A global temperature rise of 1.5ºC (which, according to the IPCC, is not inevitable but increasingly likely) will:

- push 122 million more people into extreme poverty

- reduce crop yields and undermine food security, increasing food prices by 12% and stunting by 23%

- reduce access to clean water, affecting livelihoods and increasing health threats from diarrhoea and other water-borne diseases

- increase the risk of vector-borne diseases, such as dengue and malaria, for 150 million people

- intensify heatwaves, droughts, tropical storms and coastal flooding, with disproportionate impact on the poorest communities.

Climate change is a multiplier of other development challenges, slowing economic growth and increasing conflict and fragility. It also magnifies risk and uncertainty. In 2017, 39 million people in 23 countries experienced food insecurity as a result of climate-related disasters. The impact of biodiversity loss on human food chains is likely to be severe.

Developed countries have agreed to provide $100 billion annually by 2020, from both public and private sources, to support climate action in developing countries,although the financing needs are likely to be much higher. While climate finance flows are difficult to measure, the latest estimates are well short of that commitment, and the access of many of the poorest countries to climate finance is limited by fragility and capacity constraints.

The 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa exposed serious shortcomings in both national health systems and international systems for detecting and responding to pandemic disease. Increased population densities increase the risk of epidemics, with zoonotic diseases (those that cross species, like bird or swine flu) being a particular threat. The Chief Medical Officer for England, Sally Davies, has suggested that antimicrobial resistance poses as serious a global threat as climate change.

In the security field, the number of global terrorist attacks increased sharply from 2008 and peaked in 2014, with the highest concentration in the Middle East and North Africa. Terrorism is likely to remain an ongoing threat, with unemployed young people potentially prone to radicalisation.

Serious organised crime and illicit trade – including in drugs, firearms, wildlife and people – have widespread impacts on both source and destination countries, linked both to poor economic outcomes and to conflict risk. Outflows of funds from corruption, tax evasion, trade fraud and organised crime are estimated to cost Africa some $50 billion a year – roughly twice the amount that it receives in aid – leading to calls for better regulation of the international financial system.

The geopolitical context is becoming more challenging

The changing global balance of power is challenging the rules of the global economic order, from global trading systems to the governance of multilateral institutions. By 2030, China is likely to be the world’s largest economy, with growing capacity to set global rules. Its success at generating economic growth without liberal democracy presents a challenge to the development orthodoxy promoted by the UK and other OECD donors. China is also an important alternative source of development finance, having recently pledged $60 billion in support for Africa. Its trillion-dollar ‘Belt and Road’ programme promises improved infrastructure connections for two-thirds of the world’s population, but has also prompted concerns in light of rising debt in developing countries.

Some commentators fear that democratisation around the world may have stalled or even gone into reverse. While the majority of countries hold regular elections, democracy is under threat from rising authoritarianism, populism, the effects of social media and, in some regions, hostile state action. In more than half of DFID’s priority countries, governments have restricted the space for civil society to

organise and operate.

The role of development finance is changing – and not necessarily to the benefit of the poorest countries

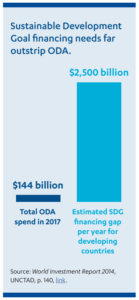

The scale of investment needed to achieve the SDGs and the Paris climate agreement far exceeds global aid flows. Developing countries will need to draw on other sources of finance, including domestic revenues and private investment. The donor community has therefore recognised that a key role for official development assistance (ODA) is to mobilise other development finance, working in partnership with the private sector.

However, the ‘billions to trillions’ narrative, as it has become known, has yet to materialise for poor countries. While the UK and other donors have agreed to double their support for domestic resource mobilisation, 35 low-income countries still collect less than 15% of GDP in taxes, making it impossible to finance basic services for their populations.

ODA has not yet demonstrated an ability to mobilise private investment at anything like the scale required. Recent research suggests that each $1 in blended finance from multilateral development banks and development finance institutions mobilises $0.75 across all developing countries, and just $0.37 in low-income countries. Estimates of the volume of private finance leveraged through ODA range between $3.3 billion and $27 billion per annum. Even the higher estimate adds less than 20% to current global ODA flows of $146 billion.

So while it is undoubtedly true that all sources of development finance will be needed to achieve the SDGs, the ‘billions to trillions’ narrative risks leaving the poorest countries behind. They remain significantly underfunded, relative to the depth of their poverty challenge, which is a major barrier to the global achievement of the SDGs.

The changing nature of UK aid

The role and function of UK aid is evolving, as the aid programme becomes increasingly integrated with the UK’s other tools for external engagement and influence.

The UK is the only major economy to meet the UN target of spending 0.7% of gross national income on aid. In the lead-up to Brexit, the government sees a large aid programme as enhancing Britain’s global status and influence as a ‘development superpower’.

The government is determined to use this status to promote the UK’s national interests. The November 2015 aid strategy announced a restructuring of the aid budget to ensure that it tackles global challenges that also threaten the UK. It argued that the objectives of reducing poverty, addressing global challenges and serving the national interest were “inextricably linked”. The 2015 National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review also commits DFID to spending at least half of its budget in fragile states and regions.

The 2018 National Security Capability Review introduced a more explicit focus on using aid to enhance mutual prosperity by building the foundations for UK trade and commercial opportunities in trading partners of the future. It also introduced the ‘Fusion Doctrine’, which specifies that the government would use its national security, economic and influencing levers in a coordinated way, in pursuit of shared objectives.

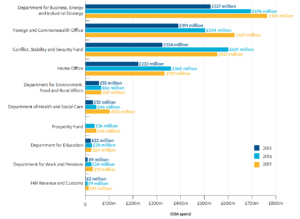

One immediate impact of these shifts in priorities was a change in the spending profile of UK aid. In 2014, DFID spent 86% of UK ODA. By 2018, this had fallen to 75% – although DFID’s budget continued to rise in absolute terms. There was a rapid scale-up in aid spending by a number of departments, including:

- the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), which is responsible for a

substantial share of UK international climate finance and ODA-funded research and innovation

programming (£849 million, or 5.8% of UK ODA) - the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), which manages a series of strategic and bilateral

programmes and contributions to the British Council, the BBC World Service and multilateral

organisations; a share of the FCO’s ‘frontline diplomatic activity’ is also charged to the aid budget

(£633 million, or 4.4% of UK ODA) - the Home Office, which contributes to first-year refugee support costs and runs a number of

programmes on modern slavery and migration (£329 million, or 2.3% of UK ODA) - the Department for Health and Social Care, which runs programmes on antimicrobial resistance,

health security and other global health issues (£195 million, or 1.3% of UK ODA).

Two cross-government funds, operating under the authority of the National Security Council, also play a growing role in the UK aid programme. Both have a combination of ODA and non-ODA resources, and are accessible to a number of departments:

- the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), which includes UK contributions to international peacekeeping and programming on conflict and security (£609 million, or 4.2% of UK ODA)

- the Prosperity Fund, which promotes economic reform and development in selected middleincome countries (£95 million, or 0.7% of UK ODA).

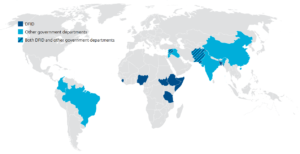

This has also led to changes in geographical focus. As Figure 6 shows, DFID’s aid expenditure is mainly concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, plus major humanitarian operations in the Middle East. The rest of the UK aid portfolio includes a growing focus on large middle-income countries that are primarily of interest to the UK from a security, climate change or economic perspective.

Figure 5: Largest ODA-spending departments and funds other than DFID

Figure 6: Top ten ODA recipients for DFID and other government departments

Other implications for the aid programme are still emerging. In a speech in Cape Town in August 2018, Prime Minister Theresa May called for “a fundamental strategic shift in how we use our aid programme”. She reaffirmed the UK’s long-standing commitments to humanitarian relief, job creation, empowering women and girls, achieving the SDGs and implementing the Paris climate agreement. She announced new areas of geographical focus, including the Sahel region and ‘frontier markets’ such as Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal. In some instances, this will involve new DFID country offices, and in other cases, a DFID presence within cross-government teams. The prime

minister also signalled an intensified focus on four thematic areas:

- addressing the root causes of conflict and fragility

- tackling cross-border threats such as terrorism, organised crime and trafficking in people

- promoting the rules-based international order, including by building stronger relationships with ‘rising powers’ like China, India and Brazil, and by more intensive engagement to shape and influence the multilateral system

- building markets in frontier economies.

More information on these changes will emerge from the forthcoming Spending Review, giving more clarity on just how large a strategic shift is involved. However, there is a widespread perception across the UK government stakeholders we spoke to that the pace of change is likely to accelerate in the coming years.

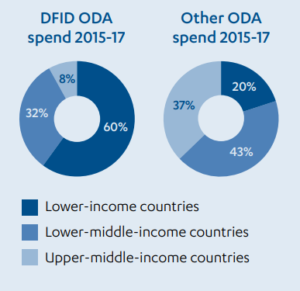

While most of DFID’s budget is spent in lowincome countries, the rest of the UK aid budget goes mainly to middle-income countries – including upper-middle-income countries where the UK has security, economic and climate interests.

“I am… unashamed about the need to ensure that our aid programme works for the UK.”

Theresa May, Cape Town Speech, August 2018

Synthesis of ICAI findings 2015-19

This section summarises key findings from ICAI’s 28 reviews over the period from 2015 to 2019, updated with the results of our annual follow-up work. We draw out common themes and explore how well equipped the aid programme is to respond to the challenges ahead.

The findings are organised under five thematic areas: leaving no one behind, jobs and economic transformation, crisis and conflict, global threats, and the changing profile of UK aid. More detail on each of the reviews can be found in the Annex.

Leaving no one behind

The UK was a global champion of the ‘leave no one behind’ principle during the negotiation of the Sustainable Development Goals. It has pledged to “put the last first” by prioritising “the world’s most vulnerable and disadvantaged people; the poorest of the poor and those people who are most excluded and at risk of violence and discrimination”.

‘Leave no one behind’ has profound implications for how aid programmes are designed and delivered, and a number of our reviews have explored how well DFID has risen to the challenge. In earlier reviews, we found that DFID programmes often targeted the poorest communities, but not necessarily the poorest members of those communities. Women and girls were commonly identified as target groups, and more latterly people with disabilities, but we have seen less of a focus on other causes of marginalisation, such as caste, ethnicity, age and sexuality.

We found that objectives around inclusion in the business cases for DFID programmes did not always translate into programme design and delivery (see Box 1). Furthermore, monitoring systems were not fine-grained enough to detect who was being inadvertently left behind. Our conclusion was that the ‘leave no one behind’ commitment needed to be more explicit in programme designs, targets and monitoring arrangements.

Why is the ‘leave no one behind’ commitment hard to implement?

In our review of DFID’s effort to promote marginalised girls’ education, we found that commitments to tackling marginalisation were not always carried through into programme delivery for a number of reasons, including:

- competing priorities, such as maximising overall access to education

- a lack of DFID influence on national education programmes

- a perceived risk of political and community resistance to an overt focus on girls

- a lack of detailed analysis of the causes of marginalisation in particular contexts

- a lack of expertise on the part of delivery partners

- poorly designed interventions

- difficulties with implementing programmes in challenging contexts.

The review recommended the adoption of country-specific strategies for marginalised girls’ education, based on detailed knowledge of the barriers in each context, and more emphasis on overcoming marginalisation in programme delivery plans and monitoring systems.

Source: Accessing, staying and succeeding in basic education: UK aid’s support to marginalised girls, 2016

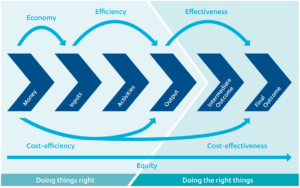

DFID has now introduced a number of measures to support its commitment. It now incorporates ‘equity’ as the fourth ‘E’ in its value for money framework (see Figure 7). This encourages programmes to specify target groups, rather than just to maximise overall beneficiary numbers. DFID has adopted an Inclusive Data Action Plan, committing it to progressively disaggregate data by sex, age, disability status and geography, and an ambitious Disability Inclusion Strategy.

Figure 7: DFID’s value for money framework now incorporates ‘equity’ as the fourth ‘E’

DFID programmes are now more likely to specify vulnerable groups as beneficiaries, even where the costs of reaching them are higher.

ICAI’s only overall ‘green’ score in the 2015-19 period went to DFID’s work on tackling violence against women and girls, in recognition of its structured approach to developing and applying evidence on what works. We also saw other good examples of DFID investing in research and evidence on leaving no one behind, including in girls’ education, social protection and transport infrastructure.

We found that DFID, often working closely with multilateral partners, had helped galvanise action on some key ‘leave no one behind’ themes, including:

- the introduction, expansion and strengthening of national social protection systems in developing countries, which boost incomes and consumption for the poorest

- road safety in multilateral transport infrastructure projects

- reproductive health and rights, including by working with the UN Population Fund to ensure a global supply of affordable family planning commodities

- the global campaign against female genital mutilation and cutting.

ICAI reports have been less positive about DFID’s efforts to promote universal, quality public services in key areas such as education, health and water and sanitation. Many of the DFID programmes we reviewed had expanded access to basic services, but not necessarily improved their quality. In maternal health, in particular, we found that poor service quality posed a significant risk to the achievement of

better health outcomes.

ICAI has also expressed concerns about DFID’s contribution to building sustainable public services. During this period, the UK government set ambitious global results targets for the aid programme, and DFID country offices were accountable for their contribution to reaching them. An unintended effect was to encourage them to turn to non-state options for delivering services, particularly in fragile states, rather than strengthen public provision. We have also observed a decline in the importance that DFID attached to development effectiveness principles. As a result, the emphasis has too often been on maximising the return on the UK aid investment, rather than building sustainable and equitable public services for the long term.

We also questioned whether the UK was doing enough to address the closure of civic space in many of its partner countries, and whether its funding practices were strengthening the capacity of civil society organisations to support and represent marginalised groups.

Overall, DFID has made good progress on implementing the ‘leave no one behind’ commitment, but will still face some significant challenges over the coming period. Other aid-spending departments have not taken on this commitment, and the shift in the geographical focus of non-DFID aid towards upper-middle-income countries is a potential cause of concern. In our review of UK international

climate finance, we noted that BEIS’s decision to focus its resources on middle-income countries with rapidly growing emissions was defensible, as emissions impact on poor people around the globe wherever they occur. However, in our review of the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), we raised concerns as to whether some of the ODA-funded research under BEIS had a close enough link to

poverty reduction.

Challenges ahead – leaving no one behind

- Developing a deeper understanding of the causes of marginalisation in particular local contexts – including intersecting discrimination (such as elderly and disabled people within marginalised communities).

- Developing strategies for tackling politically and culturally sensitive causes of marginalisation.

- Helping to protect and promote the ability of civil society organisations to support and represent

marginalised groups. - Becoming a strategic partner for strengthening public services, with more focus on policy advice,

sustainable finance and system building. - Scaling up support for domestic resource mobilisation, in support of sustainable public service delivery.

- Developing stronger systems for monitoring quality and equity in service delivery, including through

feedback from citizens. - Incorporating consideration of the ‘leave no one behind’ principle in the programming of other aidspending departments and funds.

Promoting jobs and economic transformation

Since 2010, the UK aid programme has significantly increased its focus and ambition on job creation and promoting economic growth. DFID’s economic development portfolio doubled in size between 2011 and 2016, to £1.8 billion per year. Since 2015, DFID has invested an additional £1.8 billion into the UK’s development finance institution, CDC, which invests in companies in developing countries. The cross-government Prosperity Fund was launched in 2016 to promote economic reform and development in selected middle-income countries, with a budget of £1.2 billion over six years.

In its 2017 Economic Development Strategy, DFID set itself the objective of promoting economic transformation – that is, supporting poor people to move from traditional livelihoods into more productive jobs or ways of working.86 ICAI welcomed this as an appropriate response to the problem of jobless growth in Africa, but noted that it was an ambitious objective calling for new tools and approaches.

We emphasised the need to make sure that economic development programmes are genuinely inclusive. At the time of our reviews, onitoring and evaluation processes were not strong enough to identify whether poor and marginalised groups were being inadvertently excluded. We have been pleased to note progress since then, with the most recent economic development programmes giving more attention to equity and inclusion in their design and monitoring arrangements. We also welcome the introduction of a new diagnostic phase into DFID’s business planning, to give it a better understanding of opportunities for and constraints on inclusive growth in each country.

Since 2010, DFID has built up its internal capacity on economic development, but there are limits to the expertise available in its country offices. It has therefore turned to centrally managed programmes to provide support in technically complex areas such as urbanisation and women’s economic empowerment. In the past, DFID struggled with achieving coherence and coordination between country-based and centrally managed programmes. In the urbanisation area, we noted that the benefits of centralising technical support may be offset by the greater difficulty of engaging with national counterparts.90 We will therefore continue to follow this evolution in DFID’s operating model

with interest.

Box 2: DFID’s infrastructure work with multilateral bank

The World Bank estimates that developing countries would need to spend an extra $1.2 trillion per year on infrastructure to sustain their current rates of economic growth and deal with the effects of climate change.

The multilateral development banks are specialists in infrastructure projects and provide funding on a much larger scale than any bilateral donor. The UK therefore focuses much of its infrastructure work on helping its partners to access and make good use of multilateral infrastructure finance. Programmes such as the multidonor Private Infrastructure Development Group help to meet the substantial costs involved in preparing infrastructure projects, and mobilise private investment by sharing risks.

We found that DFID had influenced its multilateral partners in areas such as road safety and cost-effective transport connections for remote communities. It had also helped to strengthen multilateral bank policies on social and environmental safeguards, although not enough was being done to ensure that the required capacity was available in country to implement those policies.

We welcomed DFID’s engagement with China on infrastructure standards, but found that it could do more to

ensure that its partner countries were able to analyse the full cost of Chinese infrastructure finance.

In recent years, DFID has directed CDC to rebalance its portfolio towards low-income and fragile contexts, for greater development impact. This has called for a transformation in the leadership, culture and capacities of the organisation, which is still under way. At the time of our review, CDC’s investments in low-income countries remained concentrated in a few countries and sectors. It needed a more active presence in developing countries to identify viable investments, and a more mature process for delivering and measuring transformative impact. These are difficult challenges for any development finance institution, and CDC will need to continue to innovate.

The National Security Capability Review emphasised that aid for economic development should create trade and commercial opportunities for the UK, as well as promoting poverty reduction. The Prosperity Fund has the most explicit focus on mutual prosperity, working primarily in upper-middleincome countries, but other aid programmes are also expected to contribute by building markets and showcasing British expertise. While most of the stakeholders we have spoken to agreed that development aid can legitimately promote the mutual interests of donors and recipients, there are concerns that the search for opportunities to do so may distort the allocation of aid by country or sector. It also raises challenging questions around ODA eligibility and good development practice.

Looking ahead, economic development and job creation will be increasingly important objectives for UK aid, raising a number of challenges.

Challenges ahead – promoting jobs and economic transformation

- Ensuring that UK aid for economic development is pro-poor and inclusive.

- Ensuring that the pursuit of mutual prosperity does not detract from the quality of UK development assistance.

- Strengthening DFID’s approach to building markets, tailored to the needs and priorities of partner countries.

- Combining economic development programmes, development capital investments and multilateral finance to promote transformational impact.

- Broadening and deepening CDC’s approach to maximising development impact in low-income and fragile states.

- Helping partner countries become more informed consumers of infrastructure finance.

Conflict and crisis

The UK government has set itself a new strategic priority of promoting long-term solutions to conflict and instability in fragile countries and regions. This is another ambitious objective: the evidence on how aid can be used to reduce conflict and fragility remains limited, and recurrent emergencies often draw resources away from the pursuit of long-term objectives.

In recent years, the UK aid programme has increased its ability to deliver in fragile environments. In both Somalia and Syria, we found that DFID had developed a network of suppliers, including companies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), able to operate in insecure contexts. This had reduced its reliance on multilateral agencies to deliver assistance and given it the flexibility to pursue its own objectives, enhancing the UK’s leadership within the international response.

However, we have seen less evidence that this has led to a more convincing approach to tackling the root causes of conflict. DFID has produced a strategy, the Building Stability Framework, but it does not appear to have been a strong reference point for programming. In our Somalia review, we encountered mixed views among DFID staff as to whether it was appropriate to pursue conflict-related objectives

in development programmes – for example, by directing support to communities or groups at risk of radicalisation. With conflict emerging as the leading cause of extreme poverty, there is a need for new thinking on how to break the cycle of poverty and conflict.

DFID has developed a discussion paper on protracted crises, which proposes “development approaches whenever possible and humanitarian aid only when necessary”. We have yet to see much evidence of this. There has been progress in some areas, such as introducing multi-annual humanitarian budgets and more use of cash transfers, which in principle facilitates transition between emergency support and long-term social protection. However, we found DFID to be reluctant to invest in local capacity in conflict-affected contexts, owing to concerns about fiduciary and other risks and the politicisation of local civil society in conflict zones.

DFID was alerted to the serious problem of sexual exploitation and abuse in humanitarian aid operations in early 2018. We found that DFID had not taken action before then, even though instances of abuse had been reported as early as 2002. Since then, it has taken a range of measures to address the issue, both internationally and in UK humanitarian aid, although the problem remains a challenging

one to solve (see Box 3).

Box 3: Sexual exploitation and abuse in humanitarian contexts

In early 2018, a serious pattern of sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) of humanitarian aid recipients by aid workers emerged in Haiti and other countries. In response, DFID established a safeguarding unit to review its safeguarding rules and procedures and encourage reform across the aid sector. It has imposed additional requirements on NGOs, contractors and research organisations to manage SEA risks in their operations. It organised a safeguarding summit in London in October 2018, at which international humanitarian actors agreed to a range of measures, including more support for survivors and whistleblowers.

Many of the stakeholders we spoke to were sceptical that these measures – although necessary – would be enough to change practices, given the acute imbalance of power between humanitarian aid workers and recipients in crisis situations. DFID has launched a substantial research programme to identify further

solutions.

The (CSSF) is an instrument that supports flexible interventions in conflict situations. It uses financial support and technical expertise to support peace processes and influence international initiatives. In Colombia, it had responded well to the peace agreement, identifying a key problem of lawlessness in former rebel areas and tailoring its security and justice support in response. However, we found that the CSSF had not invested enough in collecting evidence on what works in conflict-related programming, and that much of its programming lacked convincing theories of change and results monitoring. We also raised concerns about the depth of risk assessments when working with security agencies in partner countries with poor human rights records. The CSSF has responded well to our challenges, in particular by strengthening its results management systems.

As the UK aid programme continues to increase its focus on tackling conflict and fragility, it will face a number of important challenges.

Challenges ahead – conflict and crisis

- Ensuring a consistent approach across the aid programme to the ‘do no harm’ principle, conflict sensitivity and the promotion of human rights.

- Ensuring a deeper and more effective response to safeguarding against sexual exploitation and abuse in humanitarian operations.

- Developing long-term investments to tackle underlying drivers of conflict and fragility.

- Improving the ability of development programming and humanitarian response to work in complementary ways in protracted crises.

- Balancing the need to build local capacity with the management of fiduciary and other risks.

- Investing in evidence of what works on conflict reduction, and ensuring that programmes are evidence-based and results-focused.

Global threats

We have seen numerous examples across our reviews of the UK helping to shape the international response to global challenges. We find that when the UK uses technical expertise and evidence from the aid programme as part of a sustained campaign, it wields considerable influence. Examples from our reviews include:

- The UK is a strong advocate for international climate finance, and its substantial contributions to international climate funds make it an influential voice in arguing for more and better investment in climate adaptation and mitigation in developing countries.

- DFID has encouraged reform of the UN humanitarian system, championing the role of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and the Central Emergency Response Fund, and successfully campaigning for more use of cash payments as a form of humanitarian

assistance. - DFID has been a champion of reproductive rights and health at the global level, at a time when global cooperation on the issue has been under threat.

The 2014-16 Ebola crisis in West Africa exposed serious weaknesses in the international system for preparing for and responding to epidemic diseases, and demonstrated the vulnerability of national health systems in low-income countries. We found that the UK moved quickly to diagnose these weaknesses and develop a cross-department strategy for addressing them. DFID and the Department of Health and Social Care introduced programmes to strengthen disease surveillance and the capacity of national health systems to respond to future epidemics. The UK was also influential at the international level in promoting reform of the World Health Organization and securing global policy commitments on antimicrobial resistance. However, we expressed some concern that interventions to tackle specific diseases must not come at the expense of a comprehensive approach to health system strengthening.

Box 4: Using insurance to build resilience to natural disasters

To strengthen disaster resilience, DFID has supported the development of parametric insurance, which pays out at the outset of climate-related disasters in order to provide resources for minimising their impact. New UK-supported insurance facilities were able to make payments to Caribbean nations within two weeks of Hurricane Matthew in 2016. Following criticisms that some insurer schemes were not

paying out claims to developing countries, DFID established the Centre for Global Disaster Protection to bring together humanitarian experts, developing countries and the insurance industry to strengthen risk management and risk financing.

Not all of the programmes that we reviewed on global challenges have been as successful. In the area of international tax cooperation, DFID set out to make the process more accessible to developing countries, but we found that its efforts were not grounded in the needs and priorities of its partner countries. In its funding for UN humanitarian agencies, DFID had successfully promoted a stronger focus on results management and value for money, but its increased oversight requirements and shift to payment by results risked undermining some of the inherent benefits of multilateral aid. We also found that DFID focused on UN agencies’ operational capacity, rather than their normative or standard-setting roles.

On climate change, ICAI noted the lack of an up-to-date public strategy for UK climate finance and a risk of loss of coherence between DFID and BEIS. While DFID had a clear strategy on promoting clean energy, it had not gone about integrating climate action across its portfolio in a systematic way. There was no explicit requirement for new programmes to incorporate low-carbon development objectives, and no central leadership, guidance or central support. We share the recent concerns of the International Development Committee that DFID’s climate response is not commensurate with the scale or urgency of the challenge.

The UK’s commitment to using the aid programme to tackle global threats will raise complex challenges in a wide range of areas – including around how best to use UK influence within the multilateral forums where global action is agreed.

Challenges ahead – global threats

- Strengthening the UK’s engagement with multilateral partners without creating excessive oversight and reporting burdens.

- Promoting the normative or rule-setting role of the UN in responding to global threats.

- Encouraging ‘rising power’ nations to support international cooperation on global challenges.

- Increasing UK engagement with the work of multilateral partners at the country level.

- Ensuring that climate action is systematically integrated across UK development programming andcommensurate with the scale and urgency of the challenge.

- Promoting a more urgent international response to antimicrobial resistance.

The changing profile of UK aid

Since the 2015 aid strategy, there has been a sustained effort to integrate the UK aid programme with other tools for international engagement, including diplomacy, security and the promotion of trade and investment. Collaboration across aid-spending departments has improved, with new coordination structures in place at country and regional levels and in thematic areas.

The reallocation of aid to cross-government funds and programmes has posed some significant challenges. ICAI conducted a series of early reviews exploring their governance and management processes. We found that it takes several years to put in place the necessary systems and processes to spend aid well, and that in the interim there are both value for money risks and dangers of noncompliance with the international ODA definition and the UK’s International Development Act. The risks are heightened when new funds or programmes are required to allocate multi-annual budgets in advance. On ICAI’s recommendation, the Prosperity Fund slowed its pace of expenditure. verall, ICAI’s interventions have prompted significant improvements in the management of the Prosperity Fund, the CSSF and the GCRF.

ICAI raised concerns about how robustly some of the funds checked ODA eligibility – in particular, whether “the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries” was the main objective of each item of expenditure. Most have now put in place adequate screening processes. However, we remain concerned that the ODA definition is sometimes treated as a compliance hurdle, rather than the guiding purpose of the assistance. Departments must ensure that they use aid not just lawfully, but also so as to maximise its contribution to poverty reduction.

We have expressed additional concerns about ODA research and innovation funds. The two largest funds managed by BEIS – the GCRF and the Newton Fund – will spend more than £2 billion in ODA in the five years to 2021. A significant share of this has been allocated directly to UK research institutions, in breach of the spirit, if not the letter, of the UK’s commitment to untying all its aid. In the case ofthe Newton Fund, which supports research and innovation partnerships between institutions in the UK and in middle-income developing countries, most of the aid goes solely to the UK partners, while developing countries fund their own participation through ‘matched funding’.

This raises a wider concern about the evolving UK aid architecture. With each aid-spending department accountable for its own expenditure, there is currently no overarching mechanism for ensuring that the UK aid programme meets common principles and standards. The government has established three structures to oversee aid expenditure: the Cross-Ministerial Group, the Senior Officials Group and a Ministerial Committee for the Cross-Government Funds. These manage the 0.7% spending target and have an overall remit on value for money. The National Security Council also provides overall strategic direction. At present, however, there is no body with a clear mandate to set principles and standards to govern the quality of UK development cooperation.

As departments look for more opportunities to use the aid programme to promote mutual prosperity and the UK national interest, questions will continue to arise about how to ensure the best use of aid and how to maintain coherence across aid-spending departments.

Challenges ahead – the changing profile of UK aid

- Developing shared norms and principles across the government around what constitutes effective

development cooperation and sound aid management. - Resourcing DFID, as the aid specialist, to support other aid-spending departments on programme

management and good development practice. - Strengthening cross-departmental learning processes around aid management and development

cooperation. - Establishing principles to govern the use of aid in pursuit of mutual prosperity and national security.

- Ensuring an integrated UK development offer in partner countries.

- Enhancing the transparency of UK aid and the strategies and objectives it supports.

ICAI’s public consultation

Between 27 February and 26 April 2019, ICAI held a public consultation around what it should scrutinise and what its scrutiny products should look like. The consultation focused on two key questions:

- What areas do you think ICAI should focus on over the next four years, and why?

- What do you think of the current ICAI products? Do you have suggestions for different

products?

We received 108 responses, from a wide range of stakeholders, including development nongovernmental organisations, universities, think tanks and members of the public.

Among a wide range of suggestions for future review topics and themes, the most common were:

- multilateral aid

- DFID systems, processes and human resources

- the Sustainable Development Goals

- humanitarian aid

- procurement

- leaving no one behind.

The responses to the consultations revealed an interest in a number of sectors and thematic areas (health, climate, gender, the private sector and security sector reform), and in cross-cutting issues such as monitoring and reporting, aid effectiveness, citizen consultations and the management of aid across departments and funds.

Conclusions

The UK aid programme is evolving rapidly in response to changes in the international and national landscapes. At the global level, these include shifts in the distribution of poverty, development finance flows, geopolitical realities and the accelerating impacts of climate change. Within the UK, the aid programme is being called upon to enhance the UK’s global role and influence and support new priorities, such as building bilateral trading links. The implications of these changes are far-reaching and are still being worked through.

Our reviews over the 2015 to 2019 period have followed the progress of the UK aid programme in responding to these challenges. So far, there has not been a clear commitment across the UK aid portfolio to the ‘leave no one behind’ principle. DFID has found its own commitment a challenging one to implement, but has made good progress, with a range of reforms at the corporate level designed

to make inclusiveness central to its work. However, at the global level, the poorest countries still face a significant financing gap in achieving the SDGs. The UK government must be careful that its pivot back towards upper-middle-income countries does not lead to neglect of the key SDG objective of eliminating extreme poverty and inequality.

The UK aid programme in 2019 has a more convincing approach and set of instruments for promoting economic development than in 2015. However, many of its tools are new and untested, and considerable work is needed to learn how to deploy them effectively and in combination to meet the unique needs of each partner country. Given demographic pressures, creating decent jobs in the formal and informal sectors must be a central focus of the work.

UK aid has demonstrated that it can deliver in the midst of conflict, in some of the world’s most challenging contexts. This has given the UK more flexibility to pursue its objectives and enhanced its leadership role in the international response to crises. However, there are concerns that the increasingly onerous oversight requirements for delivery partners will make it more difficult for them to respond quickly and flexibly. With global poverty and conflict increasingly and inextricably linked, UK development aid needs to move from working around conflict to addressing conflict directly. It needs a stronger strategic direction for its conflict-reduction work, and a more integrated approach across humanitarian, peacebuilding, development and international influencing efforts, especially in protracted crises.

The UK has demonstrated on many occasions that it can be highly influential in shaping the international response to global crises, especially when it brings technical expertise and evidence to the discussion. However, we are concerned that some of the most pressing global challenges – particularly climate change and antimicrobial resistance – call for greater urgency and intensity of action.

The government has clearly signalled its intention to use the aid programme to pursue direct UK national interests – in particular, by helping to position the UK as a key trade and investment partner with frontier economies. While the pursuit of mutual prosperity is not necessarily in conflict with good development practice, the focus needs to remain on building long-term opportunities, rather than securing short-term advantage. The rules and principles underlying UK aid will need to be better articulated. Ultimately, the UK’s standing as a ‘development superpower’ rests not just on the size of its programme, but its integrity, its use of evidence and its ability to be an effective partner to developing countries in tackling the development challenges that matter most to them.

Future directions for ICAI – Tamsyn Barton, ICAI’s new Chief Commissioner

In preparing this report, we consulted with a wide range of stakeholders across civil society, academia and other areas involved in international development, including within the UK government. We also conducted an online consultation. A number of suggestions were made for topics to focus on in our scrutiny of UK aid over the coming four years.

First of all, many stakeholders expressed the view that the SDGs, as the overarching international development agenda, should provide the framework for our work. Both the consultation and this synthesis of ICAI’s reviews over the last four years have indicated the centrality of the ‘leaving no one behind’ principle. Our reviews have shown that this is a challenging commitment to implement systematically, and so far the commitment is yet to extend beyond DFID to other aid-spending departments.

Around a quarter of UK ODA is now spent by departments other than DFID. The consultation made it clear that ICAI needs to build on its scrutiny of the entire UK aid portfolio, including the crossgovernment funds. Our first review in the next phase of ICAI’s work (How UK Aid Learns) will cover all 17 aid-spending departments, and will generate evidence to inform the Spending Review and the allocation of programme and human resources across departments. We will pay more attention to human resource issues, alongside financial flows. We will continue to probe the overarching principles of aid delivery, as well as the way it is organised and governed. A shorter piece of work will interrogate the use of aid to pursue mutual prosperity, and we will continue to be vigilant in checking whether the UK keeps its commitment to untied aid.

Looking back over the past four years, it is fair to say that ICAI’s scrutiny of multilateral aid has not been commensurate with the high proportion it represents (£5.3 billion was provided as core contributions to multilaterals, which amounts to 36.5% of UK ODA). Multilateral aid was ranked as the highest priority for ICAI scrutiny by contributors to the online consultation. In the coming years, we will explore the effectiveness of UK multilateral aid, as well as the UK’s influence with multilateral partners. The African Development Bank will feature among our first batch of reviews. Our country portfolio reviews – a new initiative for examining the entire footprint of UK aid in particular countries – will explore the respective roles and contributions of bilateral and multilateral aid.

Last but not least, we welcome the views of those consulted who asked for the voices of people whom UK aid is meant to help to be more integrated into ICAI’s reviews. It is not only the right thing to do, but also helps build the case for greater accountability of UK aid and demonstrate the value of inclusion. We have already started to experiment with bringing in the views of Ghanaian citizens in our first country portfolio review, as well as of people who have directly received UK aid in Ghana. We will ensure that the voices of survivors are heard in our review of preventing sexual violence in conflict and sexual exploitation and abuse in UN peacekeeping. We are also planning to conduct an assessment of the UK’s response to the safeguarding crisis in the aid sector.

Annex 1 ICAI Phase 2 reviews, 2015-19

| Leave no one behind | |

|---|---|

| DFID’s efforts to eliminate violence against women and girls (2016) A learning review exploring how DFID goes about building knowledge, testing new approaches and moving towards programming at scale. Green rating | Key findings: • DFID has gone about building up an evidence base on what works in tackling violence against women and girls (VAWG) in a systematic way. • It has positioned itself as a leading global investor in VAWG research. • DFID has invested considerable effort in raising the profile of the VAWG agenda, with some success. • DFID has developed some innovative programming, but lacks a clear strategy for taking it to scale. Follow-up findings: VAWG remains a priority for DFID. A theory of change has been developed on scaling up and working with multilaterals. DFID has told us it will shortly announce a new business case that will significantly scale up its own VAWG programming. DFID informs us that it now has a system in place to track expenditure from programmes that focus solely on VAWG, but is still unable to track expenditure on VAWG components within wider programmes. |

| Assessing DFID’s results in water, sanitation and hygiene (2016) An impact review of DFID’s water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) portfolio, assessing whether its results claims were credible and if programmes were doing all they could to maximise impact and value for money. Green/Amber rating | Key findings: • DFID WASH investments have led to improved health outcomes, particularly reductions in infant diarrhoea, parasitic worms and other infectious diseases. • DFID’s systems are designed to maximise outputs, rather than sustainable impact. • DFID does not apply a consistent approach for measuring value for money across its WASH portfolio, nor does it have credible benchmarks to help it to identify more or less efficient programmes. However, there are examples where DFID has improved value for money at programme level. • DFID WASH programmes are not set up to measure – or maximise – sustainability. • At the central level, DFID is a significant investor in WASH research and in improving data quality. Follow-up findings: There has been a welcome increase in focus on sustainability in programme design and evaluation. DFID has been unable to extend monitoring beyond the programme cycle, but commissioned an independent study of whether results achieved in the review period had been sustained in subsequent years. There is updated value for money guidance and ongoing work to develop value for money metrics, including with UNICEF. |

| UK aid’s support to marginalised girls (2016) A performance review assessing DFID’s support for girls who are marginalised in education, assessing how well DFID has supported hard-to-reach groups and the implications of the ‘leaving no one behind’ commitment. Amber/Red rating | Key findings • DFID met its global target for 2011-15 of providing 5.2 million girls with basic education. • DFID has yet to adapt its education value for money framework to reflect its commitments on tackling marginalisation. • DFID should use emerging practice from the Girls’ Education Challenge to inform its approach to equity and value for money. • There was no overall theory of change or detailed analysis about how to tackle the causes of girls’ marginalisation in education through policy dialogue and programming. • Most of DFID’s country operational plans include a focus on girls’ education. Follow-up findings DFID’s new education policy includes a strong focus on reaching marginalised girls. Equity has been introduced into DFID’s value for money guidance and DFID has made efforts to ensure the Girls’ Education Challenge is better aligned with its in-country programmes. |

| The effects of DFID’s cash transfer programmes on poverty and vulnerability (2017) An impact review assessing the effects of DFID’S cash transfers on poverty and vulnerability and its contribution to the development of sustainable, nationally owned cash transfer systems. Green/Amber rating | Key findings: • DFID’s cash transfers have succeeded in their core objective of raising income and consumption levels, but show more variable results against secondary objectives such as improving health and education. • DFID committed to strengthening national cash transfer systems but lacked a strategic approach to technical assistance for partner governments. • DFID’s cash transfer programming offers a good value for money case, and should be scaled up. • The cash transfer programmes we reviewed had a strong commitment to empowering women, but did not sufficiently identify, monitor or mitigate the risks of negative unintended consequences, such as the threat of domestic abuse against vulnerable women beneficiaries. Follow-up findings: We recommended that DFID scale up its contributions to cash transfer programmes where there is appropriate national government commitment. DFID only partially accepted this recommendation and ICAI expressed its concern about a perceived shift away from financial support to national social protection programmes. DFID informs us that its current approach is to decide on the appropriate mix of support on a case-bycase basis. A five-year £19 million gender and social protection programme has been approved, and there is stronger guidance on assessing and monitoring safeguarding risks. |

| DFID’s approach to disability in development (2018) A rapid review assessing whether DFID has developed an appropriate approach to disability and development, and how well DFID is identifying and filling knowledge and data gaps on disability in development. Not scored | Key findings: • DFID has made a useful start and is scaling up activities ahead of the global disability summit, but a step change is needed to mainstream disability across the department. • DFID’s disability-targeted programming in key sectors is too modest in scale and reach to be likely to deliver transformational results. • DFID is a leader in promoting disability in the global development agenda. • DFID is now planning a substantial Disability Inclusive Development programme. However, DFID staff have limited guidance on how to address disability in programming. A helpdesk is to be introduced in 2018. Follow-up findings: DFID has introduced a comprehensive Disability Inclusion Strategy. This sets standards for all business units and covers DFID’s approach and culture, the engagement and empowerment of people with disabilities, influencing others, programming, and data and evidence. A new Disability Inclusion Delivery Board will meet quarterly to monitor progress, and DFID will publish an annual assessment of progress against the standards. The Strategy has targets for the home civil service to increase the proportion of staff with disability to the rate in the UK working age population as a whole. DFID has begun to build up its expertise on disability inclusion, but needs to take further measures. We are still expecting further progress on working with disabled people’s organisations and analysing local barriers to disability inclusion. |

| DFID’s contribution to improving maternal health (2018) An impact review assessing how well DFID maximised the medium- and long-term impact of its investments in maternal health programming over the 2011- 15 results framework period with specific reference to Malawi and the DRC. Amber/Red rating | Key findings: • DFID's family planning programmes have expanded the availability of sexual and reproductive health services for women. However, there were considerable challenges involved in ensuring a regular supply of contraceptives to health clinics in developing countries. • DFID has invested in strengthening basic health services, including some that are important for improving maternal health. However, they are yet to make a significant difference to the quality of services offered to women. • DFID had limited focus on reaching the poorest, youngest and most vulnerable women through its programming or monitoring. • DFID’s global advocacy in sustaining international progress on reproductive health and rights has been strong. However, there is an emphasis on short-term impact goals, limited sustainability strategies and potential displacement of some public sector family planning provision. Follow-up findings: Not yet followed up. |

| Jobs and economic growth | |

|---|---|

| The cross-government Prosperity Fund (2017) A rapid review assessing what progress has been made in putting in place the governance arrangements, systems and procedures required for the Fund to allocate resources effectively and with good value for money. Not scored | Key findings: • A major challenge facing the Fund is demonstrating impact and value for money against both its primary purpose and its secondary benefits to international and UK businesses. • It has not operated so far in a fully transparent manner. There is limited information in the public domain about its strategy and ways of working. • The Fund is subcontracting its monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning functions to contractors. There is a risk of poor integration with management and poor learning at portfolio and programme levels. • There was a lack of clarity between governance and bidding roles, leading to a perception that some departments may have privileged access to the Fund’s resources. • While the Fund had set out broad thematic and geographical priorities, the actual distribution of resources will be determined by which bids are received and pass technical scrutiny. There is a risk of this resulting in a fragmented portfolio that is unable to achieve portfolio-level strategic impact. Follow-up findings: The Treasury has extended the lifetime of the Prosperity Fund by two years, and slightly reduced its total planned spending from £1.3 billion to £1.22 billion. The Fund has developed portfolio-level indicators and associated systems for measuring results and learning from experience. It updates its theory of change annually and has appointed two monitoring, evaluation and learning service providers. There is now a procurement framework in place, with conflict of interest assessments undertaken in cases of potential risks. Ownership of official development assistance (ODA) compliance has been formally clarified. Spending departments are responsible for ensuring that spending meets ODA eligibility requirements and, as appropriate, provisions of the International Development Act (IDA) on poverty alleviation and gender equality. |

| DFID’s approach to supporting inclusive growth in Africa (2017) A learning review assessing how well DFID has gone about learning what works in the promotion of economic development in Africa. Green/Amber score | Key findings: • DFID engaged in a concerted effort to build its knowledge and expertise on economic development, and its strategy has become progressively clearer and more ambitious as a result. • While recognising that the inclusive growth diagnostics were an important step forward, DFID still has some way to go in developing country portfolios that reflect robust in-country diagnostics and learning from programming. • DFID showed increasing ambition towards economic transformation, and the new strategy has set out some good foundations, including politically smart approaches, context-specific programming and economic inclusion. While there are substantial challenges ahead in implementing these commitments, the approach is relevant and credible. Follow-up findings: DFID is beginning a drive to disaggregate its results data and track distributional impact, and the new Country Development Diagnostic has a strong emphasis on inclusion. A number of research programmes are under way, designed to generate a better understanding of which institutions matter for inclusive economic growth. Some recently designed programmes include a stronger focus on distributional impacts |

| DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments (2018) A performance review assessing whether DFID has a coherent approach to its transport and urban infrastructure work, its effectiveness in support for transport and urban infrastructure development in partner countries, and how well it uses bilateral programmes to enhance the effectiveness and value for money of other sources of infrastructure finance. Green/Amber score | Key findings: • DFID has a clear approach to selecting transport and urban infrastructure investments that support economic growth. However, the approach to poverty reduction and the inclusion of women and marginalised groups is inconsistent. • DFID has an active approach to managing value for money across the portfolio. However, there is a mixed pattern of results and inadequate monitoring of safeguarding practices. • DFID invests in research on transport infrastructure to promote knowledge on crosscutting issues, such as road safety, and to influence standards and practices across the sector. It has a number of knowledge-based partnerships with the World Bank. Follow-up findings: Not yet followed up. |