The effects of DFID’s cash transfer programmes on poverty and vulnerability

ICAI Score

Good achievement on poverty reduction impact, value for money and learning, with scope for improvement on building national cash transfer systems

DFID’s support for cash transfers helps to alleviate poverty and vulnerability for the poorest households, in accordance with the “leave no one behind” commitment. Over the 2011-2015 period, DFID exceeded its target of reaching six million people with cash transfers. Independent evaluations show that the programmes have consistently delivered on their core objective of increasing incomes and consumption levels for the poorest households, with modest but positive effects on savings, asset accumulation and debt reduction. Evidence points to more variable results in relation to education, nutrition, health and the empowerment of women – areas where cash transfers may need to be combined with other interventions to improve results. DFID has made a significant contribution to promoting the use of cash transfers in national social protection systems in its partner countries. However, in the face of shortcomings in its approach to financial and technical assistance, it is not making enough progress in overcoming weaknesses in the national programmes it supports. We find that DFID’s cash transfer programme presents a strong value for money case, given its proven ability to deliver results for the poorest. DFID has made progress on building a focus on cost-efficiency into programme management, although its practice could be more consistent. It has made a strong contribution to the global evidence base on cash transfer programming, and has used evidence and learning well to strengthen its results. There is scope for DFID to increase its level of ambition for the cash transfer portfolio by improving results in individual programmes and helping to scale up promising national programmes.

Executive Summary

Cash transfers play an increasingly important role in the fight against global poverty. In 2014, developing countries provided cash transfers to 718 million people. Their primary purpose is to alleviate extreme poverty by supplementing the income of the poorest households, enabling them to increase their consumption of food and other basic items. They can also promote other benefits, including increased use of education and health services and empowerment of women. Cash transfers are an important element of national social protection systems.

In this review, we explore the impact of DFID’s cash transfer programmes on poverty reduction[1] over the period 2011 to 2015. There have been 28 such programmes, the majority of which support national cash transfer schemes and involve both direct funding for cash transfers and technical and financial support for system building. These programmes all aimed to mitigate extreme poverty and improve nutrition, as well as to achieve a range of other programme-specific objectives. Under its global results framework for 2011-15, DFID committed to reaching at least six million people with cash transfers. Over this period, DFID spent an average of £201 million per year – around 2% of its total expenditure – on cash transfers.

Box 1: What are cash transfers and what are they intended to do?

In this review, “cash transfers” include any regular payments made to individuals and households to reduce poverty and vulnerability. They can take the form of child-support grants, old-age pensions, payments to vulnerable groups such as widows or people with disabilities, or transfers to particularly poor households. Sometimes conditions are attached around other development objectives such as school enrolment, health clinic visits or work on community projects.

Most cash transfers are very small, at the level of a few pounds a month for each household. They are designed to supplement the incomes of the poorest, increasing their consumption of food and other basic items without creating a disincentive to work.

The target groups and objectives of DFID-funded cash transfer programmes vary. For example, one programme in Nigeria targets pregnant and lactating women, with a view to improving nutrition; in Pakistan, poor households receive quarterly transfers provided that their children attend school; while in

Uganda, a DFID-funded programme helps mitigate extreme poverty among the elderly.

Cash transfers are a form of development assistance that lends itself to rigorous impact assessment, and there is a substantial body of global and DFID-specific evidence available on its effectiveness. Their importance and the available body of evidence mean that this is an appropriate area for an impact review, to examine DFID’s reported results and their significance for the intended beneficiaries.

We conducted desk reviews of 18 of the 28 programmes, and detailed case studies of programming in two countries: Bangladesh and Rwanda. We addressed three broad areas:

i. The impact of DFID-supported cash transfers on poverty and vulnerability.

ii. DFID’s contribution to the development of sustainable, nationally owned cash transfer systems.

iii. The value for money of DFID’s cash transfer programming.

DFID’s cash transfers have succeeded in their core objective of raising income and consumption levels, but show more variable results against secondary objectives

In its 2015 Annual Report, DFID reported that between 2011 and 2015 it had reached a ‘peak’ of 9.3 million people with cash transfers, against a target of six million[2]. We examined this claim thoroughly. We found some inclusion errors in the data that led to over-reporting of around 475,000 people – all from one programme. These errors were corrected when brought to DFID’s attention. For the rest of the programme portfolio, we were able to verify that DFID had exceeded its reach target.

DFID’s cash transfer programmes have succeeded in their primary purpose of alleviating extreme poverty. Independent evaluations have confirmed that DFID programmes have consistently helped to improve household incomes and boost consumption levels of food and other basic items, with no evidence of increases in unhealthy consumption choices (eg alcohol or gambling). The results data is robust and matches what would be expected from the literature.

DFID’s support for cash transfers has also brought a range of additional benefits to beneficiary households. The evidence suggests a modest but positive impact on savings, asset accumulation and debt reduction. This in turn helps to make poor households more resilient to external shocks (eg adverse weather or

unexpected health bills).

It is widely recognised that cash transfers are generally not sufficient on their own to lift the poorest households permanently out of poverty. DFID has been experimenting with a “poverty graduation” model that combines cash transfers with other interventions, such as asset grants, training and support for income generation. Its pilot programmes with a Bangladeshi NGO (BRAC) have delivered impressive results, although at a higher unit cost than a pure cash transfer programme. It is not yet known whether this model is replicable outside Bangladesh, or could be delivered by government, but DFID is experimenting with versions of the model in a number of other countries.

Most of DFID’s cash transfer programmes include secondary objectives in areas such as education, health and nutrition, and empowering women. In these areas, the evidence of impact is more mixed and, in a few cases, less than would be predicted from the global evidence base.

• Education: While many DFID-funded programmes include objectives around improving the education of children from poor households, the results have been uneven. Programmes in Pakistan and Zambia have made a positive contribution to school attendance, and one programme in Ethiopia has recorded an improvement in learning outcomes. A number of other programmes, however, showed no or very modest impact, and in Zimbabwe the programme had both positive and negative effects.

• Health and nutrition: The literature suggests a mixed but mostly positive relationship between cash transfers and improvements in health and nutrition outcomes. Independent evaluations of DFID funded programmes show a wider range of results, including some cases where no positive effect was observed. In several cases, DFID has recognised where programmes are underachieving in this area and is introducing corrective measures.

• Women’s empowerment: DFID programme design documents emphasise the objective of empowering women, and several programmes make payments directly to women. Unlike other areas, however, the focus on women’s empowerment has not been backed by rigorous measurement of results. There are encouraging signs of progress in some programmes, such as improved status for women within their households and communities and increased sexual autonomy, but the evidence is not strong enough to support a clear conclusion. We also found that DFID was not explicitly monitoring risks to women beneficiaries, such as increased domestic abuse.

Overall, we have awarded DFID’s portfolio a green-amber score for impact on poverty and vulnerability. DFID has achieved and exceeded its global reach targets. Across the portfolio, its core objective of alleviating income poverty and increasing consumption for the poorest and most vulnerable is being consistently achieved, with modest but positive impacts on building resilience to shocks. Impact on secondary objectives is more variable, with some positive results in areas such as school attendance (although not everywhere) and less positive results in health and nutrition. There is therefore scope for DFID to continue improving the impact from its cash transfer programming.

DFID has committed to strengthening national cash transfer systems but lacks a strategic approach

Beyond funding specific cash transfer programmes, DFID is also seeking to expand the coverage, quality and sustainability of national cash transfer systems. DFID has worked towards this objective by supporting pilot initiatives, as well as through funding, policy dialogue and capacity strengthening support. Over the review period, there has been clear progress in expanding national cash transfer programmes across DFID’s partner countries. In some cases, this is accompanied by increased domestic funding. While other factors are also at play, it is likely that DFID has made an important contribution to this result.

Wherever possible, DFID chooses to fund cash transfers through national programmes. This means tolerating weaknesses in the design and delivery of programmes over the short term in order to try to strengthen them over time. In most cases, DFID takes a long-term approach to systems development, sharing international and local evidence but generally choosing not to challenge partner countries on strongly held positions. While this approach is welcomed by national stakeholders, there are risks that it can lead to a lack of ambition and urgency in addressing core challenges. We observed ongoing challenges across the portfolio in the key areas of targeting, transfer size and timeliness. While recognising the positive achievements against core programme objectives, these challenges pose limits for effectiveness and sustainability. DFID is aware of these issues and, in some instances, has made good progress in addressing them, but overall progress is uneven.

DFID reports a range of practical results from its technical assistance programmes. However, its approach varies markedly across programmes, with no clearly stated rationale. We heard concerns from both DFID staff and implementers that technical assistance programmes can become drawn too far into short-term problem solving (“firefighting”) at the expense of a more strategic approach. We found that oversight and monitoring of technical assistance was not adequate, and that there have been no independent reviews or evaluations of results in this area.

There is also no clear strategy underlying the size or conditions of DFID’s financial contributions. With the exception of the Pakistan and Uganda programmes, DFID does not use performance triggers to drive reforms and it lacks a clear strategy for promoting financial sustainability.

We have therefore awarded DFID an amber-red for its system-building efforts. While DFID has good relations with its national counterparts and has helped to increase country ownership of cash transfer programmes, it lacks a systematic approach to both financial and technical assistance, and does not adequately monitor and assess the results of its system-building efforts.

DFID’s cash transfer programming offers a good value for money case, and there may be a value for money case for scaling up funding towards national coverage

We find that DFID’s support for cash transfers meets many of the criteria for value for money. It is consistently delivering on its core objective of alleviating extreme poverty and reducing vulnerability. It is an effective means of reaching the poorest and most vulnerable, in accordance with DFID’s commitment to “leaving no one behind”. There are short-term trade-offs involved in funding through national systems, and DFID should ensure that its technical assistance is sufficiently focused on improving financial sustainability. However, our analysis suggests that, where the core issues of targeting, timeliness and transfer size are being addressed, there may be a value for money case for scaling up funding towards national coverage.

Following a challenge from the Public Accounts Committee in 2012, DFID has made an effort to strengthen the focus on value for money in the management of its cash transfer portfolio. It has developed guidance and tools for undertaking value for money assessments at programme level. We saw some good use of value for money analysis in identifying the variables with the greatest impact on cost-efficiency and programme effectiveness (eg targeting, payment size and financial management). What was less clear was how these assessments were being used to inform broader, portfolio-level management decisions about funding for cash transfers.

DFID recognises evidence and learning as “cross-cutting enablers” of value for money. DFID has made an important contribution to building up evidence on what works in cash transfer programming. It has commissioned syntheses of existing literature to identify gaps and policy-relevant lessons. During the review period, it managed a centrally commissioned research portfolio of over £35 million that has been innovative in both themes and methodology.

DFID has also demonstrated a willingness to learn from international evidence and from its own programmes. It has an active community of practice that disseminates research findings and shares lessons. We saw good examples of real-time learning within and across programmes, and of the use of evaluative findings to inform new designs.

We have rated the portfolio as green-amber on value for money, owing to its demonstrated impact and strong learning orientation. There remains scope for DFID to continue strengthening the relationship between value for money assessments and management decision-making.

Conclusion and recommendations

Overall, DFID’s cash transfer portfolio merits a green-amber score. The portfolio has demonstrated its capacity to achieve impact in its core objective of alleviating extreme poverty. DFID has also made an important contribution to encouraging the spread of national protection systems. Notwithstanding the complexities of strengthening national systems and financial sustainability for social protection, there may be scope to achieve even greater value for money by taking successful programmes to scale.

The following recommendations are designed to help DFID to improve the impact and value for money of its cash transfers programming, in pursuit of its “leave no one behind” commitment.

Recommendation 1

DFID should consider options for scaling up contributions to cash transfer programmes where there is evidence of national government commitment to improving value for money, expanding coverage and ensuring future financial sustainability.

Recommendation 2

DFID should be clearer about the level and type of impact it is aiming for in each of its cash transfer programmes, and ensure that these are adequately reflected in programme designs and monitoring arrangements.

Recommendation 3

DFID should do more to follow through on its commitment to empowering women through cash transfers by strengthening its monitoring of both results and risks, and using this data to inform innovations in programming.

Recommendation 4

DFID should take a more strategic approach to technical assistance on national cash transfer systems, with more attention to prioritisation, sequencing, monitoring and oversight.

Introduction

In 2014, cash transfers to poor households reached an estimated 718 million people across the developing world.[3] Their primary purpose is to alleviate extreme poverty by supplementing the incomes of poor households and increasing their consumption of food and other basic items. Cash transfers can also help to empower women, improve school attendance and promote better nutrition and health.[4] Many developing country governments are now using cash transfer programmes as part of national social protection systems (see Box 2). At the Addis Conference on Financing for Development in July 2015, the global development community pledged to provide “sustainable and nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all”.[5] This commitment was repeated as target 1.3 of the Global Goals[6] and is a key element of the “leave no one behind” pledge.

“Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable.”

Target 1.3, Global Goals.

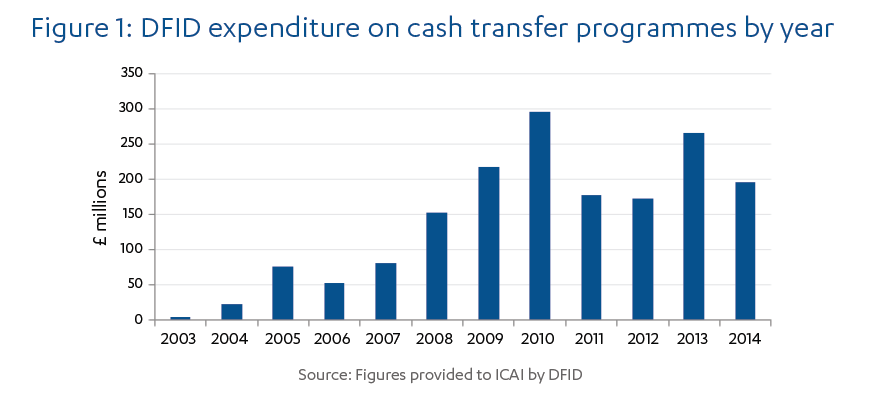

In this review, we explore what development impact DFID has achieved through its support for cash transfer programmes. DFID’s spending on cash transfers for poverty mitigation has increased as experience and evidence have grown, from £4 million in 2003 to an annual average of £201 million over the review period (2011-2015), reaching approximately 2% of DFID’s total expenditure.[7] Most of this was direct financing for cash transfers, but there was also a significant element of technical and financial assistance for the development of national cash transfer systems. In this review, we are interested both in the direct impact of DFID’s funding for cash transfers and in its contribution to building sustainable national cash transfer systems.

This report reviews DFID’s use of cash transfers for mitigating poverty and vulnerability. We have not covered the use of cash transfers for humanitarian assistance, which raises different issues, but we hope to come back to this in a future review. Our scope is DFID’s cash transfer portfolio over the four-year period covered by DFID’s Results Framework 2011.[8]

| Review criteria and questions |

|---|

| 1. Impact on poverty and vulnerability: To what extent has DFID’s cash transfer portfolio contributed to reductions in poverty and vulnerability? |

| 2. Building national cash transfer systems: How successfully is DFID supporting the development of sustainable, nationally owned cash transfer systems? |

| 3. Value for money: To what extent has DFID ensured maximum value for money for its cash transfer programming? |

Box 2: Defining “cash transfers”

In line with DFID’s own definition, we define cash transfers as “all regular cash transfer payments made to individuals and households to reduce poverty and vulnerability”. They can take the form of child-support grants, old-age pensions, transfers to specific vulnerable groups such as widows or people with disabilities, or transfers to particularly poor households. Sometimes, conditions are attached around other development objectives, such as school enrolment, health clinic visits or work on community projects.

Cash transfer programmes can serve a range of development purposes. Increasingly, they form part of national social protection systems, as a type of “social assistance”.

This portfolio was chosen for an impact review because it is mature enough to have generated a substantial amount of results data. There is also a large body of evidence-based literature on the topic of cash transfers.

Box 3: What is an ICAI impact review?

ICAI impact reviews examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries. We examine the quality of results data generated by aid programmes and whether the data is being used to improve results over time. We also assess value for money – that is, whether DFID or other spending departments are maximising the return on UK aid invested. ICAI impact reviews use the results data that is already available, triangulated with other sources. We do not carry out our own independent impact assessments.

Other types of ICAI reviews include performance reviews, which probe how efficiently and effectively UK aid is delivered, and learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming.

Methodology

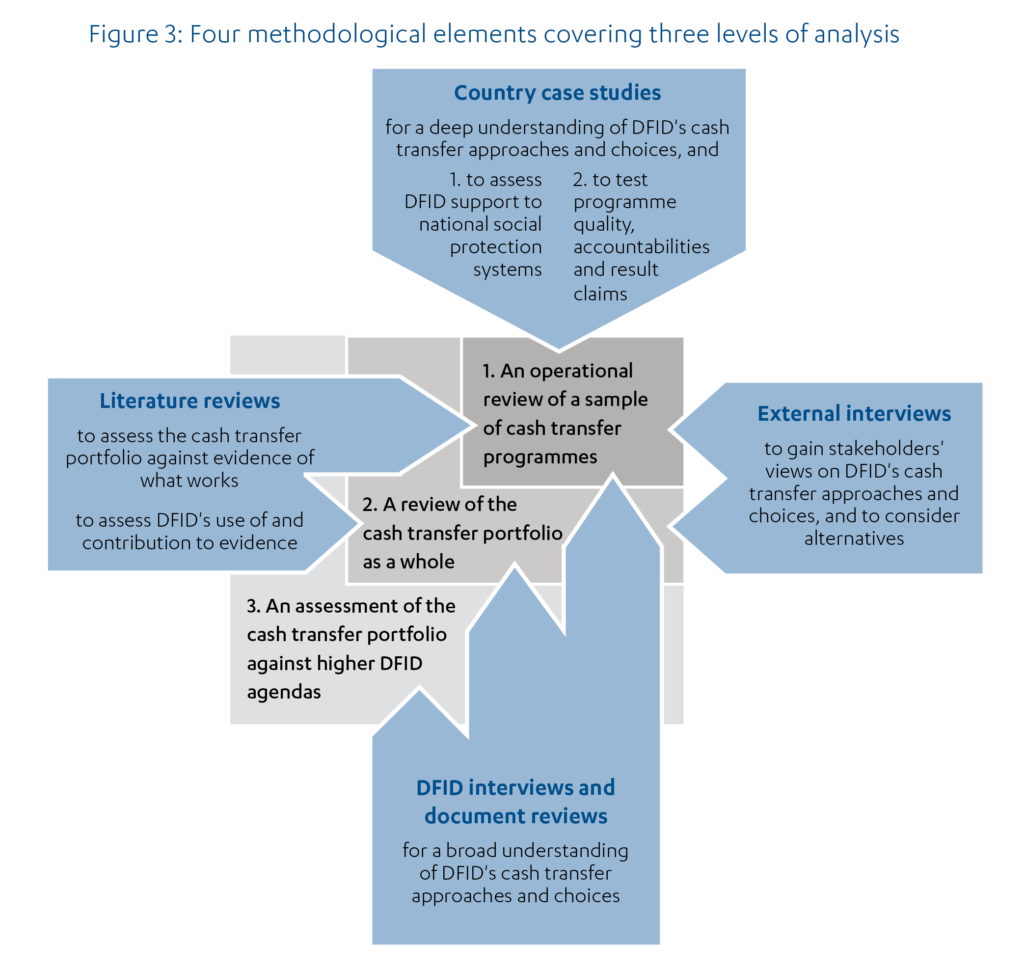

There are four main methodological elements to our review.

i. Our literature review served two purposes. First, we reviewed the available evidence on the effects of cash transfers as a yardstick against which to measure the impact of DFID programmes. Second, we compared DFID’s research choices and contributions with the worldwide body of cash transfer literature to assess the extent to which DFID has contributed to filling relevant evidence gaps.

ii. We carried out key stakeholder interviews with 36 DFID staff about the portfolio as a whole and about specific programmes. We also interviewed 12 academics and peers from other organisations to gain stakeholders’ views on DFID’s cash transfer approaches and choices. We sought out known “critical voices”, to help us challenge DFID’s thinking.

iii. We selected a sample of 18 programmes (out of a total of 28 cash transfer programmes identified by DFID) for desk review. A list of the programmes is included in Annex 2 (Table A1). For each programme we reviewed the available programme documents, including business cases, logframes, baseline studies, diagnostic studies, annual reviews, project completion reports and independent evaluation reports.

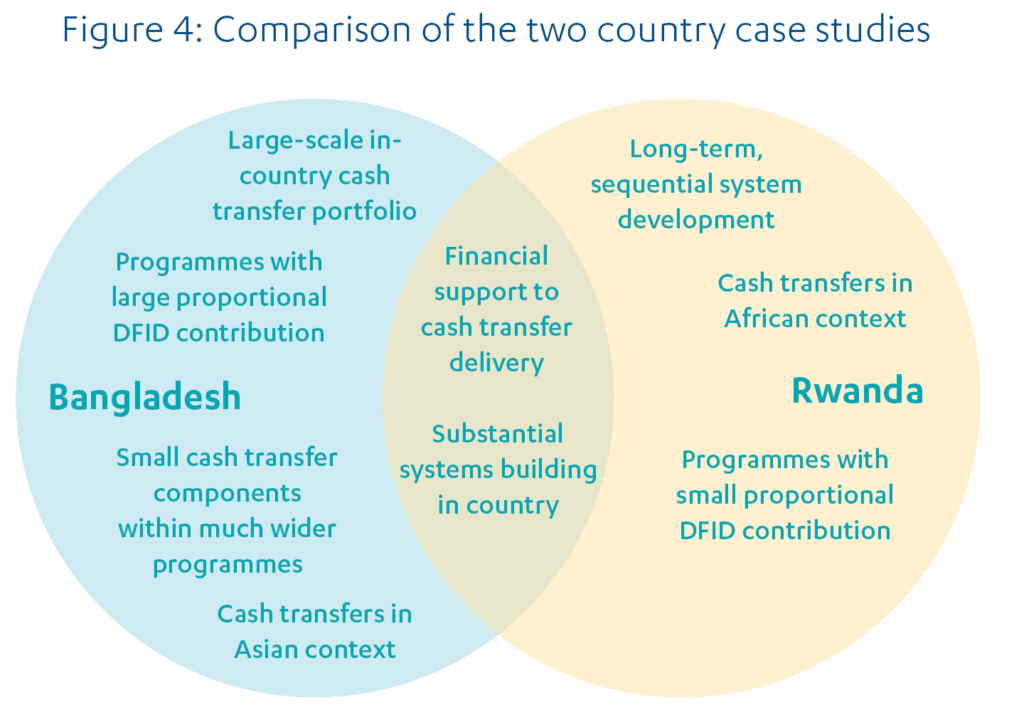

iv. We carried out country case studies of DFID cash transfer programming in two countries: Bangladesh and Rwanda. Each involved a visit by the team. The countries were selected for having a sizeable portfolio with a history of programming over several years, covering both technical assistance and financial support.

The methodology is explained in more detail in Annex 3, and in full in our Approach Paper, which is available on the ICAI website. Both our methodology and this report were independently peer reviewed.

• We relied primarily on DFID’s own results data to assess the impact of individual programmes. We discounted any results data that we considered unreliable. If there is a correlation between the impact of programmes and the quality of their monitoring data, this could introduce a positive bias into our evidence. • Our sample of programmes was chosen purposively to reflect the full spectrum of programme objectives, modalities, support, types and sizes, but may nonetheless not be fully representative. Our findings may not always be applicable to the portfolio as a whole. • There is limited evidence on the impact of DFID’s technical assistance. DFID does not necessarily document the impacts of its support on thinking and practice in partner countries. In complex multi-stakeholder environments, it is challenging to attribute progress to DFID’s advocacy and influencing work.

Background

DFID is thought to be the largest funder of cash transfer programmes among bilateral donors,[9] with annual expenditure ranging between £170 million and almost £300 million over the past five years (see Figure 1). Most of its cash transfer programmes fall within its social protection portfolio, contributing to the “poverty, vulnerability, nutrition and hunger” pillar of DFID’s results framework.[10] These programmes provide supplementary income to the poorest and most vulnerable households in order to mitigate extreme poverty and ensure that beneficiaries are able to meet minimum consumption levels of food and other basic items. They thereby aim to have positive effects on nutrition and health. Individual programmes may also aim to provide additional benefits, such as improving school attendance or empowering women.

In its results framework, DFID committed to supporting at least six million people with cash transfers.[11] To be “supported” means different things in different programmes. It may involve the household receiving a small monthly payment, often set by reference to the number of people in the household and the cost of buying basic foodstuffs (see Box 5 on payment sizes). It can also mean payment for regular or occasional labour on public works programmes. Section A5 in Annex 2 provides a more

detailed description of one particular programme, in Rwanda.

In most instances, DFID works with and through national governments in order to contribute to the development of national cash transfer systems. Most DFID programmes offer a combination of financial support for cash transfers and financial and technical assistance for system development.

Box 5: How large are cash transfer payments?

Cash transfer programmes supported by DFID provide small but regular payments to poor households, ranging from as little as £6 per household per month for Uganda’s cash transfer programme up to £19 per month for five-member households in Zimbabwe. In most cases there is an explicit rationale for the size of the payment. For example, in some programmes in Bangladesh and Zambia, the payment is equivalent to the cost of a daily bag of rice or maize, while in Nigeria it is based on a calculation of the amount needed to enable very poor households to pay for a nutritious diet. Transfer size is also determined by affordability and by political considerations. In two programmes in Bangladesh and one programme in Pakistan, we did not find an explicit rationale in programme documents for the size of the transfer.

Within the broad goals of extreme poverty mitigation and consumption protection, DFID’s cash transfer portfolio is diverse.

- Programme budgets range from £1 million to £300 million, and their duration from four to ten years, with repeat programming common.

- DFID may be the sole funder (as is currently the case for a World Bank administered programme in the Sahel), the main funder (Uganda, Zimbabwe) or one of many funders (Ethiopia).

- The programmes in Myanmar and Nigeria are delivered outside national governments, through NGO partners. Most other programmes are co-financed with government, with national contributions ranging from very little (Uganda, Zimbabwe) to most of the funding (Kenya, Pakistan, Rwanda).

- Seven programmes consist only of technical assistance. The other 21 provide a combination of technical assistance and direct funding for cash transfers (there are no cases of funding without technical assistance).

- Cash transfers are mainly unconditional. In Ethiopia, Myanmar, Nepal, Rwanda, Tanzania and Yemen, some or all of the cash transfers are provided in exchange for labour on public works. Programmes in Pakistan and Tanzania have education-related conditional components (for example the Pakistan programme provides a monthly payment of £1.80 for each child who attends school regularly).

- Some of these programmes are designed to reach the poorest in the community (though effective targeting is one of the challenges). Other programmes target a particular category of citizen, such as pregnant women in Nigeria or elderly people in Uganda.

Details of the programmes in our sample are included in Tables A1 and A2 in Annex 2.

DFID also has a substantial research portfolio on cash transfers. Since August 2009, it has centrally commissioned research contracts totalling over £35 million, many of which are ongoing. Its research partners include UK universities (Oxford, Manchester, Sussex), research institutes (the Overseas Development Institute, the Institute of Development Studies, 3ie, RAND Europe) and multilateral agencies (the World Bank, the Food and Agriculture Organization). Many of its country programmes also include research components.

Box 6: Findings from the literature on the impact of cash transfers

There is a comparatively large evidence base available in the development literature on the various impacts that can be achieved through cash transfer programming. While we would not expect to see all of these results in any single programme, the literature offers a benchmark against which to assess the performance of DFID’s portfolio as a whole.

The strongest evidence relates to reductions in income poverty. At household level, cash transfers have been consistently shown to increase total expenditure and expenditure on food, as well as to reduce various measures of monetary poverty.

There is evidence of linkages between cash transfers and school attendance, and limited evidence of a positive effect on cognitive development. However, there is no clear pattern of improved learning outcomes as measured by test scores.

There is evidence of positive effects of cash transfers on health and nutrition, measured through use of health services, dietary diversity and anthropometric measures (ie reduced stunting and wasting). However, the literature suggests that additional programme features (such as nutrition supplements and behavioural change training) are needed to produce consistent impact on child stunting.

There are positive links between cash transfers and savings, livestock ownership and investment in agricultural inputs, although these results are not universal and vary across types of livestock and inputs. Results on borrowing rates, investment in agricultural assets and business development are less clear and draw from a smaller evidence base.

The literature found contrary – but often positive – evidence in relation to domestic abuse. Cash transfers to women have been found to increase abuse in some instances and decrease it in others, depending on the type of abuse, the context and situation-specific design. There is relatively strong evidence that cash payments to women increase their decision-making power within the household. There is also evidence of positive impact on women’s choices as to fertility and engagement in sexual activity. However, cash transfers do not reduce risky sexual activity among men and boys.

Source: Cash transfers: what does the evidence say? ODI, July 2016, p. 28, link.[12]

According to key stakeholders in DFID, the department’s interest in cash transfers emerged around 2005-06. The aftermath of the 2007-08 “Triple F” crisis, when the global financial crisis was combined with sharp rises in food and fuel prices, reinforced this interest, as DFID identified that cash transfer systems in a few South American countries had shielded the poorest households from the worst effects. A view emerged within DFID that low-income countries in Africa and Asia could also develop such systems, and that DFID could support them to do so. The 2009 White Paper, Eliminating World Poverty, announced an intention to extend social protection to 50 million people in 20 countries.[13] This commitment was subsequently replaced with the target of reaching six million people.

In 2011, a DFID literature review noted that cash transfers were already “one of the more thoroughly researched forms of development intervention”. It concluded that “there is convincing evidence from a number of countries that cash transfers can reduce inequality and the depth or severity of poverty”, as well as “contribute directly or indirectly to a wider range of development outcomes”.[14]

This enthusiasm was mirrored in a February 2012 Public Accounts Committee report on “transferring cash and assets to the poor”. The report confirmed that transfer programmes “are effective in targeting aid, and ensuring the money goes directly to the poorest and most vulnerable people. There is strong evidence of short-term benefits for recipients of transfers, for example better nutrition and greater access to health and education services.” The Committee expressed its surprise “that the use of transfer programmes has not increased more in light of the evidence of positive outcomes [and that] the Department only plans to support transfer programmes in 17 of its 28 priority countries”.[15]

“The Global Goals for Sustainable Development offer a historic opportunity to eradicate extreme poverty and ensure no one is left behind. To realise this opportunity we will prioritise the interests of the world’s most vulnerable and disadvantaged people; the poorest of the poor and those people who are most excluded and at risk of violence and discrimination.”

Leaving no one behind: Our promise, DFID, November 2015.

DFID has nonetheless declined to set spending targets on cash transfers, arguing that the decision on whether to provide cash transfers, and in what amount, should be left to each country programme. It noted that: “[i]t is important the Department does not move ahead of local political and practical reality in seeking to support transfer programmes” and that “country offices are in the best place to judge which programmes offer the best value for money in achieving objectives”.[16]

The impact of DFID’s cash transfers on poverty and vulnerability

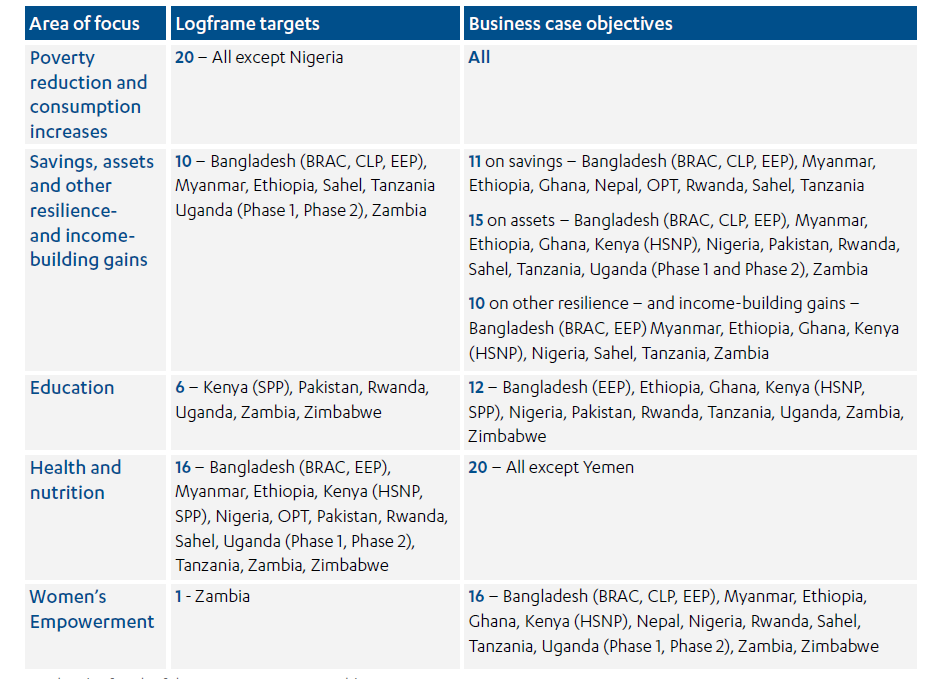

In this section, we look first at whether DFID has met the cash transfers target in its results framework. We then explore impact across our sample of 18 programmes. DFID-funded cash transfer programmes have a range of objectives (see Table A4 in Annex 2 for a DFID-funded cash transfer programmes have a range of objectives (see Table A4 in Annex 2 for a sample of logframe targets). All of the programmes are designed to alleviate extreme poverty and boost consumption, and some plan to improve household resilience to shocks. Most cash transfer programmes also include additional or secondary objectives in areas such as education, health and nutrition, and women’s empowerment (see Table 2). Not all programmes specify logframe targets in all these areas and some of the impact evaluations reveal results in areas that were not specified as logframe targets. To capture both planned and unplanned results, we looked at the evidence across five major areas:

i. Income poverty and consumption

ii. Savings, assets and resilience

iii. Education

iv. Health and nutrition

v. Women’s empowerment.

DFID provided us with an overview of 28 cash transfer and social protection programmes. Seven of them provided only technical assistance and 21 offered a combination of funding and technical support. The logframes and business cases of these 21 programmes covered a range of aims and objectives:

Table 2: DFID’s logframe targets and business case objectives

DFID’s reach target is a means to an end

Under its results framework, DFID set itself the target of supporting at least six million people with cash transfers between 2011 and 2015, measured as the total of the peak annual reach of each programme. This is known as a reach indicator: it shows the scale and coverage of DFID’s programming, but not the effects of cash transfers on beneficiaries. The indicator does not include the impact of DFID’s technical assistance on expanding national cash transfer systems.

While these are real limitations, the reach target remains relevant for three reasons. First, it builds on a large body of evidence showing a causal link between the provision of cash transfers and poverty mitigation. Second, DFID is a key advocate for the expansion of cash transfer coverage in Africa and Asia, and the reach target helps to signal this commitment. Finally, its inclusion in the results framework provided a clear signal to DFID country offices during the 2011 Bilateral Aid Review that cash transfers were a priority.

Cash transfers reached more people than DFID aimed for, but fewer than it reported

In its 2015 Annual Report, DFID reported that between 2011 and 2015 it had reached a ‘peak’ of 9.3 million people with cash transfers, including 4.9 million women and girls.[17] According to DFID data, most individual programmes met or exceeded their targets, with the exception of programmes in Bangladesh (after the correction of a reporting error, covered below), Zimbabwe (with an underachievement in 2015 only) and the Sahel.

We reviewed this data (see Box 7). We found that, with the exception of DFID Bangladesh, all country offices had followed the approved methodology and had mechanisms in place to check data provided by their implementers. Where the data was incomplete, DFID used explicit assumptions to calculate its total.[18]

Box 7: Verifying DFID’s overall results claim

We assessed DFID’s reported “reach” results by subjecting the programmes in our sample to five tests:

i. Have DFID’s implementing partners verifiably followed the guidance notes about what “reach” means? For example, are beneficiaries counted only once, and are they exclusively members of households in which at least one member has received “regular cash transfer payments” that were provided with an aim related to “tackling poverty and vulnerability”?

ii. Do the results look plausible and, if not, is DFID able to provide satisfactory explanations of unlikely numbers such as identical targets and results or identical results for women and men?

iii. Have the reported results been adjusted to reflect changes in the context? For example, has the claimed DFID proportion of a national programme changed when the national government increased its contribution or when a new funder joined?

iv. Have DFID country offices scrutinised the data and are they able to discuss it substantively?

v. Has there been periodic, independent verification of the reported results?

We did find a few inaccuracies. The only material one is that, in Bangladesh, various errors associated with one specific programme resulted in an over-claim of almost half a million people (corrected after we brought it to DFID’s attention). Notwithstanding this error, we conclude that there is reliable evidence that DFID has achieved and exceeded its target of six million people, even though the total is somewhat less than DFID reported.

There are two main reasons why the six million target was exceeded. First, the original target was lower than the sum total of the 2011 country targets, which added up to 7.2 million people. Second, while a few of the programmes planned at that time never materialised (including in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo), two new, larger Pakistan programmes began during the review period, adding more than three million people to the total reached.

DFID’s cash transfers have succeeded in supplementing incomes and increasing consumption

The primary purpose of DFID’s cash transfers is to alleviate extreme poverty for the duration of the transfer (which may be short-term or open-ended) by increasing income and consumption levels. Independent evaluations have confirmed that DFID programmes have, in almost all cases, succeeded in achieving this objective. This finding is consistent, whichever definition of poverty is used.[19]

The evaluations have consistently found that cash transfers increase consumption in beneficiary households.[20] There is no evidence of an increase in unhealthy consumption choices (eg increased spending on alcohol or gambling) and in some cases there is evidence of a decrease. The most impressive finding is from Kenya, where beneficiary households spend significantly more of their overall income (not just the cash transfers) on food, health and clothing, and significantly less on alcohol and tobacco.

These are very positive findings, suggesting that cash transfers are proving to be an effective means of alleviating severe poverty.

Box 8: The intangible benefits of cash transfers

Not all of the benefits of cash transfer programmes can be measured quantitatively. During our country visits to Bangladesh and Rwanda, we met various beneficiary groups who stressed the importance of cash transfers in reducing the stigma of poverty and creating a more positive outlook on life, as illustrated in the following quotes.

Cash transfers have modestly increased longer-term income and resilience

In addition to improving consumption levels, increasing household income through cash transfers can bring a range of additional benefits. According to the literature, cash transfers may help to increase and diversify household income by enabling beneficiaries to acquire productive assets and take calculated risks in their business ventures (which is more likely if cash transfers are regular and predictable). In addition, cash transfers have been shown to boost savings, reduce debt and change the ways in which beneficiaries behave. All of this, as well as the assets built or maintained by public works programmes, potentially contribute to households becoming more resilient to shocks (see Boxes 9 and 10).

While potentially complex to measure, these effects have been confirmed in a number of DFID’s cash transfer programmes. A common result is a reduction of indebtedness and an increase in creditworthiness – two factors that affect households’ ability to deal with crises. Such effects were reported in DFID-funded programmes in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Nepal, Rwanda, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Box 9: Cash transfers’ potential contribution to household resilience

Households living below or close to the poverty line are vulnerable to shocks, such as unexpected medical bills or adverse weather affecting their agricultural activities. One comprehensive review of the literature found that regular and predictable cash transfers can reduce poverty by making them less vulnerable to such shocks. Cash transfers can help to increase savings and the ability of beneficiary householders to access credit through formal and informal mechanisms. This in turn can reduce their reliance on detrimental risk-coping strategies, such as distress sales of productive assets or reducing consumption of food and other necessities below minimum levels.

In the longer term, cash transfers can also build resilience by enabling beneficiary households to make investments and change their livelihood strategies, such as by introducing sustainable land management practices.

We also found a number of other effects that were specific to individual programmes.

- In Zambia, recipient households were found to be more resilient to shocks and external fluctuations in income than they had been in the past, due to various factors including reduced debt, increased investment in assets, reduced reliance on casual labour and livelihood diversification (such as increased livestock, more production of agricultural output for markets and increased non-farm enterprise).

- In Zimbabwe, an independent impact evaluation concluded that, after only 12 months, the programme had led to increased agricultural assets and livestock, diversified income sources and reduced indebtedness. As a result, there was a reduction in vulnerability to shocks, particularly among smaller households.

- Reviews in Rwanda and Uganda tracked data on savings and productive assets. Both reported an increase in livestock, though probably not to the point that the gains would survive a single household shock. A study in Uganda found that transfers were helping recipients to purchase other types of productive assets.

- Conversely, a study in Pakistan reported that recipients expressed an increased desire to save, but that an actual increase in savings occurred in only a single province (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).

While these findings illustrate the potential for cash transfers to go beyond boosting consumption, the reported impacts are relatively modest and, in many cases, amount to resilience against only a single shock. DFID’s annual reviews and evaluation reports confirm that cash transfer programmes do not have a lasting impact on income-earning opportunities and resilience, unless accompanied by other interventions.[21] This is probably true everywhere, but especially in African countries, where the state of rural economies makes it particularly challenging to diversify income.

A more ambitious “poverty graduation” model in Bangladesh is achieving results by combining cash transfers with other forms of support

The biggest gains in both income and resilience are achieved by the DFID-funded programmes in Bangladesh. These programmes combine relatively small cash transfer components with other interventions, such as asset grants (eg livestock) and supporting products and services (eg animal vaccinations, food supplements, entrepreneurial and other training, and hygiene awareness raising).

DFID was a supporter of the Bangladeshi NGO BRAC when it first piloted this model in 2002. The approach has developed but not fundamentally changed since then, and there is strong evidence that it has enabled a large majority of beneficiaries to achieve substantial improvements in their socioeconomic status. The chances of these mixed interventions achieving results that continue after households have exited the programme are much stronger than for pure cash transfers. Furthermore, the results have shown an ability to survive climate shocks.

It is not yet known whether this model is replicable outside Bangladesh (only a few initial studies exist),[22] whether it can be delivered by government (as opposed to an NGO) or how it performs in times of economic downturn. Moreover, these combined interventions are more costly than standard cash transfers. However, the results are impressive enough for DFID to be supporting a pilot adapted from this model in Rwanda, while other pilots in Pakistan and Kenya are under development.

Box 10: DFID-funded cash transfer programmes build resilience above household level

In Ethiopia and Bangladesh, public works programmes often support adaptation to climate change through, for example, reforestation projects or developing flood-resistant infrastructure.

Furthermore, in Ethiopia (but not in Rwanda, Myanmar or Nepal), some public works programmes schedule work to take place in the lean months of the year, when participants are most likely to be suffering from food insecurity. This counter-cyclical effect also contributes to resilience.

Despite significant success in Ethiopia and Pakistan, the effects on education have been generally modest

There is strong evidence that DFID’s cash transfer programmes have been successful in their core objectives of relieving income poverty, increasing consumption and, in some instances, providing a modest boost to resilience. However, most cash transfer programmes also include additional objectives in areas such as education, health, nutrition and empowering women. In these areas, the evidence of impact is more mixed and, in some cases, less than would be predicted from the literature.

Nine of the 18 programmes in our sample mentioned educational goals in their business cases. The programmes in Pakistan (see Box 11) and Ethiopia have achieved considerable success, but in the other programmes the impact has been modest, absent or, in one or two cases, negative. Overall, the impact of DFID’s programming on enrolment and attendance (although not necessarily learning) is below what the wider evidence suggests can be achieved through cash transfers. It is likely that weaknesses in programme design and implementation (see the sections on cash transfer targeting, timeliness and size) have held back results in these areas.

Box 11: School enrolment in Pakistan

The Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) is the main social assistance programme in Pakistan. It targets and provides unconditional cash transfers to the poorest 25% of households. An independent evaluation found that unconditional cash transfers had no impact on school enrolment, but the addition of a conditional transfer did have an impact.

A sub-group of BISP recipients receive a quarterly amount of some £5.40 per child, conditional on school enrolment and an attendance rate of at least 70%. This conditional transfer is combined with behavioural change communication on the importance of schooling.

The marginal impact of this additional, conditional cash transfer (ie compared with children in households that received the unconditional cash transfers only) is an increase in the enrolment rate of nine percentage points for girls and boys alike. Source: Benazir Income Support Programme; Evaluation of the Waseela-e-Taleem Conditional Cash Transfer, OPM, July 2016, draft version.

In seeking to understand this mixed performance on education, we found no particular correlation between the presence of explicit education-related logframe targets and a programme’s education related outcomes. Schooling is not among the Ethiopia programme’s logframe targets, but transfers have helped children from poor families to attend schools and have improved educational attainment and progress. In one region – Tigray – children in recipient households outperformed the children of better-off, non-recipient households. Conversely, the Kenya programme does have education-related logframe targets, but the results have been limited to a minor enrolment increase among children living a long way from school. In Uganda, a hope that the transfer would support schooling has not materialised: the programme has not increased household expenditure on education and has had no impact on children’s attendance or attainment at either primary or secondary level.

We also came across an example of negative impact. In Zimbabwe, poor government coordination across programmes meant that cash transfer recipients were discouraged from participating in the Basic Education Assistance Module (BEAM), another government programme that provides targeted resources for children to attend school. An external evaluation found a 6% decline in BEAM participation among DFID-funded programme participants, which offset other positive effects on education (including a seven percentage point increase in the probability of school progression for children of primary school age in small households). An external assessment suggested that there may also have been a negative impact from a public works programme in Nepal. The researchers noted that, while the programme does not employ children below the age of 16, it may nonetheless have increased school absenteeism as a result of children taking on extra responsibilities of caring for younger siblings while their parents are participating in the programme.

Where programmes did increase school attendance, this did not necessarily result in improved learning outcomes. In Zambia, one of the two grant types resulted in large impacts on enrolment of both primary- and secondary-age children, but there was no impact on educational outcomes for primary school age girls.[23] The wider evidence suggests that cash transfers on their own rarely secure a positive impact on learning, due in part to problems with the quality of national education systems. DFID has other programmes in most of its partner countries that aim to strengthen education systems.

Evidence of impact on health and nutrition is uneven across and within programmes

All of DFID’s cash transfer programmes (not just those in our sample) include objectives around health and nutrition, and 15 of them incorporate health and nutrition indicators in their logframes. This reflects empirical evidence from the literature that cash transfers can promote both greater use of health services and more dietary diversity, although impacts on child wasting and stunting are generally weaker.

Notwithstanding this strong focus on health and nutrition, evidence of impact in these areas is uneven in our sample programmes (see Table A3 in Annex 2). Where effects have been achieved, they are sometimes smaller than what the literature suggests is possible. In some cases, DFID recognises that its health and nutrition objectives are not being achieved; in Ethiopia and Bangladesh, DFID is supporting experiments combining cash transfers and other types of health and nutrition-related support in order to improve results.

The available evidence suggests that several of the programmes DFID is supporting are currently not optimised for maximum impact on nutrition and health, and that improvements in design and implementation – including timeliness and transfer size – could strengthen results in this area.[25] These challenges and the manner in which DFID is supporting governments to overcome them are discussed in the section on DFID’s work to strengthen national cash transfer systems.

Women’s empowerment is central to programme design, but impacts are not fully clear

DFID’s programmes place a strong focus on women’s empowerment in their business cases. In some cases, women are the sole recipients of cash transfers (eg Nigeria, Bangladesh). Other programmes take care to ensure that eligible women have access to the cash transfers. For example, the Ethiopian public works programme uses client cards that feature the names and photographs of both husband and wife, and includes a range of measures to ensure women have access to the income. In contrast, the Myanmar public works programme allowed only one member of each household to participate, resulting in a preponderance of men.

The literature suggests that cash payments to women can strengthen their decision-making power within the household and their choices about fertility. However, there is mixed evidence about the impact of cash transfers on domestic abuse, with both positive and negative results recorded depending on context and programme design.[25]

Despite the risk of causing harm under certain circumstances suggested by the literature, we found that none of the programmes in our sample were monitoring levels of domestic abuse. This is a surprising omission. While government counterparts may sometimes be reluctant to monitor domestic violence, owing to political sensitivities, DFID could invest in other monitoring or review mechanisms to ensure that programmes cause no harm in this respect.

DFID does monitor other empowerment indicators across its programmes. However, measuring empowerment is a challenging undertaking and we found DFID’s approach to be relatively weak. Only a few programmes were monitoring a basket of indicators capable of generating a robust picture of empowerment (see Box 12), despite the fact that DFID has been a pioneer of research on the impact of cash transfers on women’s empowerment.[26] The lack of robust programme monitoring in this area is a notable gap, suggesting that DFID is not putting its own research into practice or doing enough to build up practical experience on what works in this critical area.

Box 12: Measuring women’s empowerment

Women’s empowerment is a complex phenomenon to measure. Good practice suggests that it should be assessed using multiple indicators looking at different aspects of empowerment. The ODI cash transfer review measures empowerment on the basis of six indicators: domestic abuse, women’s decision-making power, marriage, pregnancy, use of contraception and having multiple sexual partners.[27] Other reports consider participation in public life, control over and ownership of assets, and/or access to information.

Few DFID-funded cash transfer programmes have systematically measured more than one or two of these indicators. As a result, their reported results are not particularly robust.

The exceptions are an assessment in Pakistan and a few assessments in Rwanda. In Pakistan, an external assessment looked at the proportion of women that are economically active (no statistically significant effects), at women’s control over cash and other resources (no effects), and at women’s mobility (a small positive effect on women’s ability to visit a friend’s home). In Rwanda, one assessment found improvements in intra-household decision-making, more equity in household relations and positive improvements in women’s participation at the community level as a result of the programme. Two other studies on the Rwanda programme were less positive, reporting similar findings but at a marginal level. Moreover, they found no effects on the gender division of labour within households, no marketable skills development and they noted that distance, times and lack of care facilities were obstacles for women’s access to public works programmes.

The limited evidence that is available points to mixed results from DFID’s programmes. In Zambia, which set a logframe target on women’s decision-making, there was no measurable progress. Programmes in Kenya and Zimbabwe impacted positively on adolescent girls’ sexual health (see Box 13), even though this was not an explicit target for either programme.

Box 13: Safe transitions into adulthood

In Zimbabwe, there is some evidence that the programme has supported the safe transition of adolescent girls into adulthood. Among the programme’s reported results were delayed sexual debut and marriage, decreased likelihood of early pregnancy in large households and a positive impact on safe sex practices among sexually active youth (ie condom use at first sex). These findings are encouraging but tentative, as the sample size was modest and the findings were only based on the initial 12 months of the programme.

DFID’s cash transfer portfolio is achieving its primary objectives, but with scope for improvement in other areas

Overall, we award DFID’s cash transfer portfolio a green-amber score for impact on poverty and vulnerability. The core objective of DFID’s cash transfer programmes is to alleviate income poverty and increase consumption for the poorest and most vulnerable, for the duration of the transfer. There is strong evidence that these results are being delivered consistently across the portfolio. Moreover, in some programmes the increases in income are in turn making beneficiary households more resilient to external fluctuations in their incomes, due mainly to increased creditworthiness and reduced debt. DFID has also achieved promising results from a more ambitious model of poverty graduation and is exploring how this could be replicated. These are strong results that, in our view, make a good case for DFID’s continuing investment in cash transfers.

There is no room for complacency, however. We found that DFID programmes are not always clear about what additional results to target, beyond the core objective of poverty alleviation, and therefore may not be optimised to deliver such results. Impact on school attendance has been below DFID’s targets, and we identified a few instances of zero or even negative impact. Evidence of impact on health and nutrition is uneven, both within and between programmes, with a pattern of results that DFID is sometimes unable to explain. Although women’s empowerment is a central concern in DFID’s business cases, its monitoring is not strong enough to generate robust results, and we are concerned that DFID has not done enough to monitor for unintended negative results such as increased domestic abuse. We are encouraged that DFID is beginning to explore how to combine cash transfers with other interventions, so as to maximise results in these areas.

DFID’s impact on the development of sustainable national cash transfer systems

DFID has successfully encouraged the introduction and expansion of national cash transfer systems in low income countries

When describing the cash transfer portfolio, DFID staff place more emphasis on the long-term aim of increasing the coverage, quality and sustainability of national cash transfer systems than on the immediate effects of DFID’s funding on today’s cash transfer recipients. The underlying objective is to extend coverage of cash transfers, particularly across sub-Saharan Africa, so that they become part of a standard toolkit in the fight against extreme poverty and vulnerability.

According to stakeholders in DFID, there are two dynamics that may, in the long run, support this goal. First, as national cash transfer systems become established, expand and demonstrate their effectiveness, public expectations and political commitment will grow and become mutually reinforcing. Second, the spread of national cash transfer systems across Africa would create a positive “neighbourhood effect” where national governments are under increasing pressure to emulate the actions of their neighbours.

Over the review period, government-operated cash transfer programmes in sub-Saharan Africa have indeed shown a rapid growth path, both in number and coverage. The number of countries with unconditional cash transfe programmes increased from 21 in 2010 to 40 in 2014 (out of 48),[28] reaching some 50 million people.[29] Within our sample, the programmes in Uganda, Rwanda and Zambia had expanded particularly fast.

In part, this expansion was underpinned by domestic political support that already existed at the start of the review period. Eight of DFID’s partner countries had signed the 2006 Livingstone Call for Action – an intergovernmental document calling for reliable long-term funding for social protection from both national budgets and donors.[30] The African Union had also adopted a policy framework on social protection.[31] In parallel, the World Bank has helped national governments to adopt or expand social safety nets.[32]

Building on this initial support, DFID contributed to the expansion in cash transfers through evidence based policy advocacy, financial contributions and technical assistance on a range of issues (Table A4 in Annex 2 lists some of the diverse objectives of technical assistance). DFID also funded pilot programmes, either through government or non-government partners, in order to demonstrate the potential benefits of cash transfers, create a body of context-specific evidence and stimulate public demand.

It is obvious that DFID funding has directly enabled national governments to improve and extend their coverage. It is more difficult to isolate the impact of other forms of DFID support, but it is reasonable to conclude that DFID has made a valuable contribution to building the commitment of its partner countries to developing national cash transfer systems for the poorest and most vulnerable.

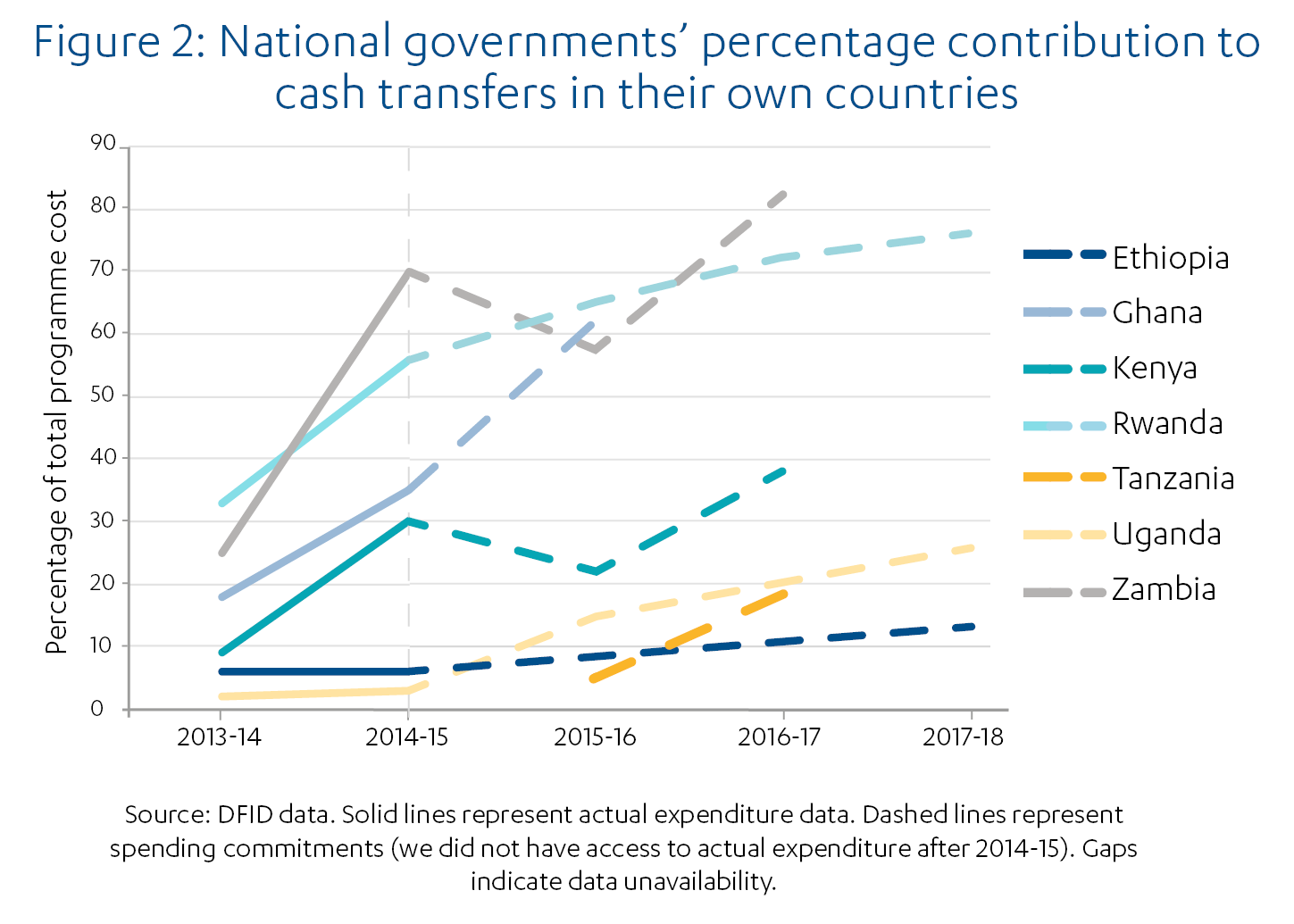

African governments have increased their financial contributions, although sustainability is still some way off

One of the indicators of this increased commitment is national financial contributions and commitments (see Figure 2). In the last few years, the capacity and willingness of African governments to fund national cash transfer systems has changed dramatically. In the words of one DFID advisor, “governments have changed from the assumption that ‘we cannot afford this’ to the question of how much they would be able to contribute”.

This change has been facilitated by a decade of economic growth in Africa, buoyant commodity prices and better macroeconomic management, creating more budgetary space. However, it was by no means certain that these additional resources would be invested in social protection. DFID has provided seed funding for national systems and has actively advocated for national contributions. We find it plausible that this has helped to secure government funding in a number of cases.

DFID’s partner countries are, nevertheless, still a considerable distance away from providing sustainable national funding for their cash transfer systems (the same can be said for other public services and development programmes). Financial contributions from national governments are often irregular; in Rwanda and Uganda, pressure on national budgets has resulted in disbursements for cash transfers being below what was budgeted. Furthermore, existing programmes still fall well short of nationwide coverage, there are programme design problems and the amounts transferred to individual households are not always high enough to make a meaningful difference.

It is not yet clear that the political consensus is strong enough to sustain budgetary allocations through economic downturns and in the face of competing priorities. Recent discussions in the Ethiopian parliament illustrate this. The country has a long-standing, large-scale public works programme, but there are still voices arguing for a reprioritisation towards fuel subsidies (which are shown not to be effective in reducing poverty). This underscores the challenges that the government of Ethiopia faces in delivering on its objective of full domestic financing of the programme within the next decade.

While financial sustainability may be a long-term goal, it is nonetheless notable that DFID has not yet begun to formulate an overall strategy for achieving it. There is no explicit rationale for the size and duration of its financial contributions, which vary considerably. Nor does DFID explicitly seek to incentivise increased national contributions via its own funding (though it does encourage increased national contributions through other means). As national programmes begin to be consolidated, financial sustainability will become an increasingly important consideration.

DFID’s choice to work through national government systems makes sense, but there are some short-term disadvantages

There are both advantages and costs to working through national systems. When working with NGO partners, DFID has the significant short-term advantage of direct influence over programme design and implementation. In its NGO-implemented programme in Nigeria, for example, DFID can be confident that the cash transfers offered to pregnant and lactating women are soundly targeted, with a meaningful transfer size (£14 per household per month) and a good record on timeliness. On the other hand, being donor-financed and NGO-implemented, the programme has limited geographic coverage, rates poorly for sustainability and does not contribute to the goal of strengthening national cash transfer systems.

As only national governments are in a position to develop sustainable cash transfer systems with nationwide coverage, DFID chooses to work with and through national systems whenever conditions allow. As a result, while it tries to influence the design and delivery of programmes through policy dialogue and technical assistance, it must ultimately accept the partner country’s right to decide. In the short term, this entails trade-offs in several important areas – particularly around the efficiency of targeting, transfer size and the reliability of transfer payments – all of which can hamper the size and depth of programme impacts. Given DFID’s ultimate goal of building sustainable national cash transfer systems, we regard this as a legitimate trade-off, provided that DFID is doing everything reasonably possible to strengthen these programmes over time.

DFID takes a gradual and evidence-based approach to policy dialogue

In most instances, DFID supports the development of national systems over an extended period – either through long-term programmes (eg ten years in Zambia and eight years in Pakistan) or a sequence of shorter ones. During these engagements, DFID contributes to the development of national policies and systems but does not insist on a single programme model. Generally it avoids directly confronting counterparts on strongly held positions. Instead it chooses to tolerate shortcomings in the national systems it funds while aiming for incremental improvements over time. As one DFID advisor put it, “we are supportive, show our value, and then see if we are able to open other doors”.

DFID’s engagement is often informed by political economy analysis, which helps advisors to negotiate complex political terrain. In appropriate cases, DFID makes good use of evidence in its policy dialogue. It synthesises evidence from cash transfer programming around the world and shares it with national counterparts. It also invests in domestic research and in documenting local success stories, where it believes this would be more persuasive. It should be noted, however, that evidence-based advice is not always taken, and we have found examples where governments are resistant to evidence that challenges their design choices or calls into question the effectiveness of their programmes.

During our visit to Rwanda, we found evidence that DFID’s policy advocacy had significantly influenced counterpart attitudes and beliefs. Our documentary analysis and feedback from a number of Rwandan senior civil servants, DFID staff and technical advisors led us to conclude that DFID has verifiably helped to advance the government’s thinking about social protection. There is a clear progression of the technical assistance programme, moving from basic advocacy work on core design issues to more detailed advice on technical delivery challenges. For example, it is now agreed that people living with disabilities are an important target group; the assistance now focuses on how best to identify and target them. DFID has also influenced adjustments to some of the key social protection principles. These include ring-fencing (ie protecting against budget cuts) unconditional transfers and introducing a system of budgeting across regions based on need rather than pre-determined percentages.

Across the sample, DFID has made useful contributions to the development of national policies and strategies. Elements of the National Social Security Strategy in Bangladesh can be traced back to DFID’s engagement, as can the government of Myanmar’s decision to start a 1,000-day maternity cash grants system. Similar examples can be found in Kenya, Pakistan, Rwanda, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

DFID are keenly aware of the need to protect against opportunities for fraud and leakage within the cash transfer programmes they support. We also noted, however, that DFID may end up avoiding politically difficult but important areas of engagement relating to targeting errors in their policy and advocacy work with national governments. We did note that on occasion, political sensitivities can mean DFID avoiding tackling targeting issues directly. In Bangladesh, for example, DFID’s technical assistance programme started out with a relatively lengthy diagnostic exercise rather than engaging directly with problems of targeting – both inclusion and exclusion errors – that were already well known and evidenced (and which were a key reason for DFID providing technical rather than financial assistance to the programmes in the first place).

It also chose not to address the systemic but politically sensitive problem of the fragmentation of the government’s many social protection programmes. While the Bangladesh case shows that DFID’s patient approach to policy dialogue helps to maintain good working relations with counterparts, this should not be at the cost of a lack of ambition or urgency in tackling the most pressing problems head on.

DFID’s technical assistance is focused on improving programme delivery

Cash transfers are a new undertaking for most of DFID’s partner countries. They often begin with limited capacity to design, implement and maintain a national cash transfer system. In the few countries with a history of cash transfer programmes, such as Bangladesh, these are fragmented and spread over multiple ministries, giving rise to an additional problem of overcoming vested interests.

Wherever it provides financial aid, DFID also provides technical assistance to strengthen national delivery mechanisms. DFID’s annual reviews identify a range of examples where its technical assistance has helped to translate government preferences into practical policies, systems and processes, with accompanying monitoring systems to promote adherence. Examples include the following:

- In Kenya, flexible technical assistance helped the government with its targeting and recertification processes (ie determining whether beneficiaries remain eligible). Other contributions related to a management information system and an electronic payment system.

- In Uganda, DFID supported the government in the development of a social protection policy framework. It helped to design and implement a consultation process that improved the quality of the policy and also helped to build government understanding and support for social protection at both national and local government levels.

- In Nepal, DFID helped social protection programmes with no history of cross-fertilisation to learn from each other.

- In Zambia, technical assistance was instrumental in enabling the programme to scale up from 32,000 recipient households in 2010 to 240,000 in 2016.

- A conditional cash transfer programme in Pakistan was mainly designed by DFID technical advisors before being handed over to government.

Across the portfolio, we identified technical weaknesses in three areas – targeting systems, timeliness of payments and transfer size – that can have a significant impact on effectiveness and value for money. While DFID is aware of and engaged on all of these issues, it is often required to tolerate shortcomings in one area in order to focus its efforts on another. We look at each of these areas in turn.

Targeting errors remain common across the portfolio

Targeting systems are basic to the design of cash transfer programmes. An effective means of ensuring that cash transfers reach the poorest and most vulnerable households is key to maximising impact. We found that targeting errors exist across the portfolio. They fall into three main types:

- Targeting that is not focused on the poorest and most vulnerable households. In Rwanda, the selection of recipients is based on the government’s Ubedehe system – a home-grown community cohesion instrument that correlates only weakly with poverty levels. Even where targeting is explicitly focused on the poorest and most vulnerable households, different concepts and measures of poverty and vulnerability can lead to very different selection outcomes. The Sahel programme provides a good illustration. In this programme, different tests were used to identify the poorest households and those most vulnerable to shocks. [33]These two groups should strongly overlap but, according to one key informant, the lists of eligible people had only a very minor overlap in some of the areas they surveyed.

- Inclusion errors. The inclusion of people who are not in fact eligible is all but inevitable in programmes that target on the basis of community selection or household income, as local power dynamics, misreporting and seasonal variations give rise to an unavoidable margin for error. Even programmes targeting specific groups may feature inclusion errors. A unique case was found in Nigeria where fake urine samples were reported to have initially led to the inclusion of women who were not actually pregnant. DFID successfully introduced random pregnancy testing to tackle the problem. The largest inclusion error we came across was in Pakistan, where the programme aims to reach the poorest 25% of the population but the World Bank found that a quarter of recipients fell well above that threshold. Rather than occurring from a failure to apply the targeting criteria properly, inclusion errors can also happen if the criteria themselves are inadequate. The child-focused programme in Zimbabwe used the criteria of labour constraints and food-poverty to identify households who may have been affected by the AIDS crisis and have children to care for. However, this resulted in 17% of the recipient households being included in spite of not having any children.[34]

- Exclusion errors. In Pakistan, the women who receive the transfer must hold a valid Computerised National Identity Card. This led to temporary exclusions, as it takes time to acquire this card. In the early implementation stages in Myanmar, the most remote and labour constrained households were effectively excluded from public works programmes, as were a range of other particularly vulnerable groups (eg single women with young children and other labour-constrained households, disabled people, households without local registration cards).

Not all targeting problems are equally problematic, nor do all require an immediate solution. In some cases, the effort required to fix the targeting would be disproportionate to the benefits. Sometimes the finer points of targeting assume a lower priority in the face of more pressing issues such as expanding national coverage.

We nonetheless found several cases (in Rwanda, Nepal and Zimbabwe) where, in our assessment, DFID should have made greater use of its influence to improve targeting and to monitor the results more systematically. In Pakistan, DFID and other key international stakeholders have shown that it is possible to persuade a national government to change its targeting paradigm even in the face of strong vested interests (see Box 14).

Box 14: Changing the targeting paradigm in Pakistan

Before DFID’s involvement, the targeting system in Pakistan’s largest cash transfer programme was the major constraint on programme effectiveness. All national and provincial assembly members were given a budget for cash transfers and authorised to select the beneficiaries. After advocacy and technical support from DFID, the World Bank and USAID, the targeting mechanism was changed to a proxy means-based Poverty Score Card that enables effective targeting of the poorest 25% of households. It is not yet perfect (in 2013 the World Bank estimated that only 75% of the transfers reached the poorest 40% of the population) but it has been a step change in Pakistan’s cash transfer practice, making it considerably more effective in alleviating poverty.

DFID has invested in improving the timeliness of cash transfers, but delays remain common