The UK’s aid response to irregular migration in the central Mediterranean

Executive Summary

The recent large-scale arrival of refugees and migrants into the European Union has made migration a subject of renewed and intense political interest. In its 2015 Aid Strategy, the UK government pledged that UK aid would tackle “the root causes of mass migration”. Aid-spending departments are in the process of identifying how UK aid contributes to this objective and developing new, targeted programmes.

This rapid review explores what progress has been made in developing a relevant and effective aid response to irregular migration. We use the term “irregular migration” to refer to both refugees and voluntary migrants crossing borders without the required documents. We recognise that these two groups have distinct legal statuses and rights.

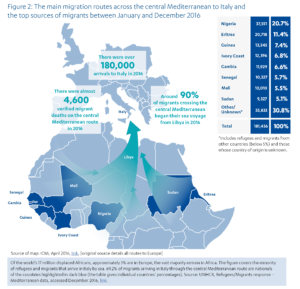

In this review, we focus on the central Mediterranean route through North Africa into southern Europe. This is currently the major route for arrivals into Europe and, with 4,576 confirmed deaths at sea in 2016, a continuing humanitarian crisis. Much of the UK government’s work on migration is funded from outside the aid budget. Our review does not examine this work or the pros and cons of UK migration policy, as these are beyond ICAI’s mandate. The review covers all UK aid spending on irregular migration across government, within the central Mediterranean region.

An ICAI rapid review is a short, real-time review of an emerging issue or area of UK aid spending that is of particular interest to the UK Parliament and public. While we examine the evidence to date and comment on issues of concern, our rapid reviews are not intended to reach final conclusions on performance or impact, and are therefore not scored.

Is a relevant aid response to irregular migration emerging?

The core objective of the government’s Illegal Migration Strategy – which is only part-funded from the aid budget – is to limit the number of irregular migrants arriving in Europe and the UK. Under the rules that govern official development assistance, this cannot be the main objective of an aid programme. However, aid programmes can legitimately address the root causes of irregular or forced migration and protect vulnerable migrants, while contributing to a reduction in irregular migration towards Europe as a secondary objective.

At the time of the review, the responsible departments were yet to settle on a shared definition of “migration-related” aid programming. There was therefore no agreed list of migration-related programmes which we could use to measure expenditure.

However, from UK government documents and interviews, we identified the following emerging categories of migration-related programming:

• Tackling conflict and fragility, partly in order to reduce forced displacement.

• Reducing the socio-economic causes of irregular migration.

• Supporting local integration in situations of protracted displacement.

• Providing humanitarian support and protection to refugees and internally displaced persons.

• Countering people smuggling and trafficking and modern slavery.

• Promoting regular migration within Africa to provide alternatives to irregular migration through the central Mediterranean.

The government has recognised that, to influence global migration, it needs to invest in shaping the wider international response. The government credibly claims to have been influential in a number of areas, particularly in relation to reshaping the international response to protracted displacement. While we were not able to independently verify the results, the influencing messages were well defined, reflected in the UK government’s own practice, and clearly communicated by the responsible departments.

As the government seeks to define and develop its migration-related programming, national Compacts stand out as the most innovative and important concept. Compacts support both host communities and refugees through a combination of humanitarian and development interventions. As they target groups with a high propensity to migrate irregularly, they have the potential to reduce irregular migration.

There are various assumptions that will need to be tested as the programming evolves, but key stakeholders agreed that the concept is a positive one, and that the UK’s role in developing, promoting and funding the Compacts is welcome.

Other than in relation to the Compacts, the government’s thinking on how to reduce irregular migration by tackling its root causes – conflict, underdevelopment and, potentially, population growth – is much less developed. These root causes are clearly linked to migration, but in complex and unpredictable ways. Unless carefully designed to target local drivers of irregular migration, the impact that aid interventions could have on the root causes of irregular migration remains uncertain. As this review was being drafted, the government informed us that it is developing a set of “principles” on good migration-focused aid programming, to be published in April 2017. This could be an important step towards more tailored and consistent programming on this issue.

To help develop its portfolio, DFID has invested in data collection and research on migration. Stakeholders both inside and beyond the government note that much of this research is relevant and of good quality. However, the evidence gaps remain substantial, and we saw few examples where existing research findings on the causes of irregular migration were already being used to inform programming choices. We note a body of research that points to the benefits of migration for development, and to the impact development can have on migration, but there is a lack of evidence on what influences migration decisions, particularly in the short term.

Overall, the government has not yet settled on a well-defined migration portfolio and it is therefore difficult for us to assess expenditure. Cross-departmental approaches to addressing the root causes of migration are still under development, and have not yet fully absorbed research findings on the causes of irregular migration. Further work is required to understand these causes in particular contexts and apply this understanding to effectively address irregular migration through aid programmes. We find that there has been valuable investment in research, appropriate efforts to shape the international response to irregular migration, and promising initial development work on Compacts.

How effective are migration-related programmes likely to be?

Since 2015, the government has moved quickly to build up capacity on migration-related programming in the responsible departments, and to create cross-government strategies and coordination structures. There is now a Migration Department within DFID, and capacity has been added in the Foreign Office, Home Office and Cabinet Office. A cross-government Migration Steering Group was established, co-chaired by the National Security Adviser and the Home Office. Despite high staff turnover, stakeholders report a good level of cross-government dialogue and coordination.

In Libya and Nigeria (two of our three country case studies), as well as in the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund’s (CSSF) Africa portfolio, most current migration-related aid programming is small and rather fragmented. The programmes also remain some distance away from making a measurable impact on irregular migration through the central Mediterranean. This is the case partly because UK aid’s focus on migration is very recent. At the time of this review, the government was in the process of operationalising the migration objective of the Libyan aid programme and defining a migration strategy and related aid programmes for Nigeria.

We selected Ethiopia as the third country case study because this is where the government’s thinking on irregular migration is most advanced. The Horn of Africa is a strategic priority for the UK, and Ethiopia is a major host country for refugees who have fled conflict and repression in the region. The aid response has been active and innovative, centred on the idea of promoting durable solutions for refugees with shared responsibility between international donors and the host country. Major programmes are being developed to improve the lives and livelihoods of both refugees and host communities, including an £80 million Jobs Compact. This Compact aims to create 30,000 jobs for refugees, as part of a much larger job creation programme for host communities. This is very ambitious, considering that the approach rests on a number of assumptions which still need to be tested. However, the approach shows promise by responding to the aspirations of would-be migrants rather than focusing solely on the need to provide humanitarian support.

In Libya’s volatile and insecure environment, the delivery options are limited and the programming small in scale. It is focused on humanitarian support to irregular migrants in detention centres, training for the Libyan coastguard on search and interdiction operations, and support for “assisted voluntary returns”. These interventions are likely to make only a marginal difference to a national system that denies refugees rights (Libya does not recognise the right to asylum). In addition, we are not convinced that the risk of unintended harm has been sufficiently analysed, incorporated in programme design, monitored and managed.

Nigeria is currently the largest source country for migrants on the central Mediterranean route, accounting for 21% of 2016 arrivals in Italy. However, at the time of the review it was not a priority country for work on central Mediterranean migration, and there was no consolidated list of migration-related programmes. Programmes were being designed to prevent Nigerians being trafficked into Europe for sex work and bonded labour, and there was funding to improve Nigeria’s border security. However, most of the other programming that the government identified as migration-related was ongoing work on economic development not designed with irregular migration in mind (for example youth-focused skills development programmes). These programmes did not demonstrate a contextualised understanding of irregular migration from Nigeria, or have mechanisms for targeting people likely to migrate. We therefore found these kind of programmes’ links to irregular migration too uncertain to warrant labelling them as “migration-related”.

Migration has only recently been added to the strategic framework of the cross-government CSSF, which supports UK objectives in fragile states with an annual budget of over £1 billion (both aid and non-aid). The CSSF is exploring options for a criminal justice response to people smuggling and trafficking, but has encountered various challenges in identifying approaches that are likely to be successful. The CSSF is therefore taking an appropriately cautious approach to developing larger-scale programming on people smuggling and trafficking.

We looked at the approach to value for money in migration-related programming. We found that DFID is giving due attention to value for money management techniques in its procurement and delivery arrangements. For the CSSF, the small and fragmented nature of the migration portfolio makes it difficult to conclude that it represents value for money, but efforts are underway to increase the average programme size and improve strategic effects. However, the larger value for money issues in the migration area are the lack of a shared understanding of the challenge, insufficiently clear portfolio objectives and the lack of a clear body of evidence on what works. This makes it difficult to determine what “value” to assess. Only once a set of credible programming options emerge will it be possible to begin serious analysis of how to deliver them cost-effectively.

Conclusions and recommendations

The UK response to irregular migration in the central Mediterranean remains at an early stage. Departments are under considerable pressure to deliver the objectives of the National Security Council’s Illegal Migration Strategy, including limiting arrivals in Europe and the UK. However, they face a complex and rapidly changing context and a range of difficulties, including a lack of consensus on the nature of the migration “crisis” and a body of research that offers limited guidance on what works.

The Compact approach in Ethiopia and other countries stands out as the most promising initiative for a number of reasons, including its inclusion of groups with a known propensity for secondary displacement, its potential to benefit all migration-affected groups and its potential for adaption to different country contexts. These elements point to a number of productive ways to think about how to use aid to address the challenges related to irregular migration.

Looking across the evolving portfolio, we have made three recommendations based on our concerns with the aid response as we currently see it.

Recommendation 1

The UK government should not label development programmes as migration-related unless they target specific groups with a known propensity to migrate irregularly and can offer a testable theory of change as to how they will influence migration choices.

We find the re-labelling of much existing programming as “migration-related” to be unhelpful, and not well supported by the evidence. Such programmes were not designed to target populations or individuals with a propensity to migrate irregularly and there are no efforts to monitor the impact of such interventions on irregular migration.

Recommendation 2

The responsible departments should invest in adapting monitoring and evaluating methods to the long causal chains between interventions and irregular migration patterns, and ensure that the new portfolio of programmes already in design include strong baselines and monitoring arrangements.

The causal links between aid interventions and the root causes of migration are long, complex and difficult to verify through standard monitoring and evaluation. New programming on irregular migration will require innovative monitoring and evaluation arrangements, informed by the latest research.

Recommendation 3

The UK aid response to irregular migration should be informed by robust conflict, human rights and political economy analysis, to ensure that it does not inadvertently do harm to vulnerable refugees and migrants. This information should be fed in at an early stage of project or programme design and documentation should contain a clear articulation of the risks, benefits and risk appetite.

Some programming may be prone to causing unintended harm to vulnerable migrants, particularly where national law enforcement standards are poor. This calls for investment in context analysis, conflict and risk assessment and understanding the complex political economies involved in the central Mediterranean migration route.

Introduction

In recent years, global migration has emerged as an increasingly important issue for UK aid. The large-scale movement of refugees and other irregular migrants into the European Union (EU) in 2015 and 2016 and the continuing humanitarian crisis of deaths in the Mediterranean Sea have made migration a focus of intense political and public attention. The UK government has pledged that UK aid will be restructured to tackle the “root causes of mass migration”, among other global challenges, including through increased spending in Syria and other fragile and conflict-affected states.

Through the UK Aid Strategy and National Security Council strategies, aid-spending departments have been mandated to increase their focus on migration, with a particular focus on reducing irregular migration into Europe and ensuring protection to those who need it. This review assesses what progress they have made in developing a relevant and effective aid response.

We have chosen to focus on the central Mediterranean migration route (that is, migration through transit countries in North Africa into southern Europe) for a number of reasons. It is currently the largest and most dangerous route for irregular migrants into Europe. With 4,576 verified deaths at sea in 2016, it represents a continuing humanitarian crisis. It also affords us an opportunity to examine UK aid programming along the migration route, from source countries across Africa through transit countries in North Africa. The review does not cover support to asylum seekers in the UK.

What is an ICAI rapid review?

ICAI rapid reviews are short reviews carried out in real time to examine an emerging issue or area of UK aid spending. Rapid reviews address areas of interest for the UK parliament or public, using a flexible methodology. They provide an initial analysis with the aim of influencing programming at an early stage. Rapid reviews comment on early performance and may raise issues or concerns. They are not designed to reach final conclusions on effectiveness or impact, and therefore are not scored. Other types of ICAI reviews include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries, performance reviews, which assess the quality of delivery of UK aid, and learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming.

The review covers any UK aid identified as migration-related by the responsible departments. Most of this is spent by DFID and the Foreign Office, with some resources coming from the cross-government Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF). Other departments and agencies, including the Home Office and the National Crime Agency, are involved at the strategic level and have small implementation roles. Many of the programmes are still in design or at an early stage of implementation. The review also covers related international influencing efforts, as well as the commissioning and use of research and data collection. The scope is limited to the aid response; ICAI does not have a mandate to review UK asylum or other migration-related policies.

We have chosen to conduct a rapid review because of the high levels of public interest and because the aid response to the migration crisis is still in its infancy. The aid response is at too early a stage for us to reach any final judgment about the effectiveness or impact of individual programmes. As with other rapid reviews, we do not offer a performance rating at this stage, but we point out areas of concern and make a number of recommendations as to how the aid response could be improved.

Review criteria and questions

- Relevance: Is the UK aid response to the migration crisis in the central Mediterranean relevant and proportionate, given the nature and scale of the challenge?

- Effectiveness: Are the UK migration-related aid programmes likely to make an effective contribution to the UK government’s migration strategy?

Global migration is a highly political subject, and the terms used to describe it are value-laden and contested. In our interviews with stakeholders, we encountered a range of views as to whether there is in fact a migration “crisis” and what it consists of . The interests are wide apart. While the UK works to limit immigration and is tightening its immigration rules, many developing countries see emigration as contributing to their socio-economic development. Additionally people fleeing persecution have a right under the 1951 Refugee Convention to claim asylum in a safe country. As this is not a review of government policy, we make no assumptions as to whether migration is positive or negative. Rather, we explore how far the UK aid programme has come in developing a relevant and potentially effective response to the various challenges posed by different forms of irregular migration via the central Mediterranean.

Contested terminology

Differences in the way stakeholders understand the migration challenge are reflected in their terminology.

A number of government documents refer simply to the aim of “addressing the root causes of migration”, without further qualifications. In other documents, the Home Office and the cross-government Illegal Migration Strategy use the term “illegal migrants” for all those crossing borders without proper papers, irrespective of the cause of their displacement or their right to asylum. External stakeholders including the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights refer to migrants who arrive in countries of destination without documents as being in an “irregular situation” or “undocumented” or “unauthorised”. They disagree with the term “illegal” because these individuals have not necessarily committed a criminal act. DFID is also reluctant to use “illegal migrants” as an umbrella term for all those taking the central Mediterranean route towards Europe, and emphasises that refugees have a right to claim asylum under international law. Instead, DFID proposed a set of definitions of international and internal migration that distinguished between “regular” and “irregular” migration and, within the latter group, between “forced displacement” and “voluntary migration”. In this report, we use the term “irregular migration” to avoid presenting “migration” as such as undesirable, and to avoid labelling legitimate refugees as criminal. When we use the word “migrants” without further specification, we mean this to include refugees, while acknowledging that refugees are different from other migrants in terms of their distinct legal status and rights.

What is the “migration crisis”?

The UK Aid Strategy refers to “the current migration crisis.” In our discussions with stakeholders, we encountered a range of views on the nature of this “crisis”. It was described in many ways including:

• the increase in refugee movements following the Syrian and other protracted conflicts

• the numbers of people dying when attempting the Mediterranean crossing

• the sharp increases in arrivals of both refugees and economic migrants into Europe

• the breakdown in EU systems for asylum management

• public concerns that refugees might increase the terrorist threat

• the growing political opposition to migration in some European countries.

These different interpretations of the crisis in turn affect what challenges the aid programme is required to address – whether conflict and instability, lack of livelihood opportunities within the migrants’ countries of origin, the loss of lives in the Mediterranean or the absence of lawful migration opportunities.

Methodology

Our methodology for this rapid review consisted of:

• A literature review of academic and other research on the effects of aid on migration, and a collation of data and analysis on central Mediterranean irregular migration.

• A review of relevant UK government policies, strategies and commitments.

• A round table with 12 people from nine research institutes and implementing organisations.

• Key stakeholder interviews with 51 government officials from DFID, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the National Security Council Secretariat and the Home Office (including a representative of the National Crime Agency), and with 19 people from 11 research institutes and implementing organisations.

• A desk review of migration-related aid strategies and programming in three countries – Libya, Ethiopia and Nigeria.

The scope of our review included any programmes identified by the responsible departments as migration-related, whether or not this was explicitly stated in programme objectives. We found that, at the time of the review, the government did not have a shared view on which categories of programme are migration-related, and did not have a settled list of programmes. We therefore relied on key informants from the responsible departments to identify the most relevant programmes.

Background

Irregular migration in the central Mediterranean

The central Mediterranean migration route into Europe draws mainly from source countries in West and East Africa. Most migrants along this route (90% in 2015-16) begin their sea voyage in Libya, heading towards Italy. This is currently the main route for migrants crossing into Europe. Arrivals rose from an average of 23,000 per year in the period 1997 to 2010 to over 180,000 in 2016.

The sea crossing is extremely hazardous. Around 5,000 migrants are known to have lost their lives on the Mediterranean in 2016 (4,576 in the central Mediterranean), compared to 3,777 in 2015.

Most of the migrants pass through conflict-torn Libya, where they face a significant risk of violence and exploitation. Prior to the conflict, Libya was an important destination country in its own right, hosting 1.5 million migrant workers. The substantial deterioration of law and order rendered Libya a less attractive destination, while creating opportunities for the long-standing people smuggling business to thrive.

What are people smuggling and trafficking?

“People smuggling” is the facilitation of illegal crossing of national borders for payment. It differs from “people trafficking”, where the movement of people is done for the purpose of exploitation, often involving forced labour or prostitution. People smuggling is in essence a voluntary process, even though the individuals may end up vulnerable to abuse or exploitation. Smuggling routes across the Sahara have existed for centuries, but in recent years these routes have been used much more intensively for people smuggling. Contrary to the common perception, people smuggling is not typically carried out by large, hierarchically organised criminal organisations, but by networks of actors embedded in local communities along the migration routes. In some countries, there is evidence that public officials, the military, police and border guards are implicated in the process. The fluidity of the criminal networks and their links to national authorities makes people smuggling a difficult problem to tackle through law enforcement.

The global response to migration challenges

In recent years, migration has become a more prominent issue for development assistance. The 2015 Sustainable Development Goals contain references to the situation of migrant workers, the problem of human trafficking and the importance of “well-managed migration policies” to facilitate “orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration.”

There have been a number of recent high-level events and agreements on migration – particularly the control of irregular migration. Principles adopted at the Khartoum Process (November 2014) and the Valletta Summit (November 2015) refer to the need for international cooperation to:

• address root causes of irregular migration and forced displacement

• cooperate on legal migration and mobility

• prevent irregular migration and fight against people smuggling and trafficking

• protect migrants and asylum seekers

• facilitate returns.

To further these commitments, an EU Trust Fund for Africa was launched at the Valletta Summit “for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa”. It had a planned initial budget of €1.8 billion (£1.5 billion) until 2020 from the European Development Fund and member states.

Since the large-scale secondary displacement of Syrian refugees from neighbouring countries in 2015, the UK government has advocated greater international attention to the challenge of protracted displacement. The subject was discussed at the Syria Conference (February 2016), a Wilton Park Forum on Forced Protracted Displacement (April 2016), the World Humanitarian Summit (May 2016), the 71st UN General Assembly and a Leaders’ Summit hosted by the US President Barack Obama (September 2016).

These events have taken place against the background of a tense political climate. Within Europe, the sharp increase in irregular migrant arrivals in 2015 was met with growing political opposition in a number of countries. In Africa, the planned closure of the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya and anti-migrant violence in South Africa are symptomatic of reduced political openness to migrants and refugees.

UK policies and priorities

In the UK, migration has become a subject of intense public and political interest. Mass migration is mentioned in the UK Aid Strategy as a global challenge which directly threatens British interests, alongside disease, terrorism and climate change. UK government respondents often mentioned they were under considerable pressure to come up with a portfolio of programming that would quickly and substantially reduce irregular migration into Europe.

Cross-government work is governed by an unpublished National Security Council Illegal Migration Strategy, which sets out a number of goals, including improving the asylum and returns process, reducing unmanaged migration along the eastern and central Mediterranean routes, and addressing the root causes and enablers of forced displacement and illegal migration. Its objectives for the central Mediterranean include reducing departures from Libya and North Africa through better management of land and sea borders, the provision of adequate protection and assisted voluntary returns.

In September 2016, the Prime Minister set down three overarching principles for the government’s migration work:

• Ensure that refugees claim asylum in the first safe country they reach.

• Improve the ways we distinguish between refugees fleeing persecution and economic migrants.

• Get a better overall approach to managing economic migration which recognises that all countries have the right to control their borders – and that countries must all commit to accepting the return of their own nationals when they have no right to remain elsewhere.

Findings - Is a relevant aid response emerging?

Since the 2015 UK Aid Strategy introduced a mandate to focus on the migration crisis, the responsible departments have been identifying which existing aid programmes could be considered “migration-related”, while preparing a new portfolio of more targeted programmes.

In this section, we explore what progress the government has made in defining and developing its portfolio of migration-related programmes, and how research underpins and sometimes challenges the relevance of this portfolio.

Which aid programmes do the responsible departments consider to be migration-related?

To qualify as Official Development Assistance (ODA) under the international definition, all UK aid must have “the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective”. Assistance to refugees also qualifies as ODA. In addition, aid spent under the International Development Act must be “likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty”.

Under the Illegal Migration Strategy, a key priority is to limit arrivals in Europe and the UK. This cannot be the main objective of an aid programme, but it is permissible for ODA-eligible programmes to pursue the reduction of migration as a secondary objective. An example would be a programme that helps refugees in a third country integrate locally, with reducing their likelihood of coming to Europe as an accompanying, secondary objective. In some cases, determining which objective is primary is a matter of interpretation. A few of the officials we interviewed mentioned grey areas and suggested that ODA eligibility “often depends on how you describe a project”. That

notwithstanding, ODA rules do impose limits on the extent to which this strategic priority can shape aid programmes. DFID has been advising other departments on the application of the ODA-eligibility rules in this context (and we saw an example where this prevented non-ODA work being classified as ODA).

In addition to the objective of limiting arrivals in Europe and the UK, there are a range of ODA-eligible objectives in the latest (November 2016) version of the Illegal Migration Strategy. These objectives are broadly aligned with the objectives of existing programmes that the responsible departments have labelled as “migration-related”. These programmes fall under the following broad categories:

• Programming that addresses conflict and instability. The government has committed to increasing its investment in fragile states and regions, partly “to reduce forced displacement and migration over the long term”. For the time being, only a few of these programmes have specific migration-related objectives.

• Programming that addresses socio-economic causes of irregular migration. Because irregular migration is often linked to economic aspirations, some of DFID’s existing economic development programming, including on livelihoods, market development, the energy sector, the finance sector and extractive industries, was included in overviews of migration-related programming. These programmes were newly labelled as such. They were not designed with migration objectives in mind, and do not explicitly target groups that are most likely to migrate.

• Programming in situations of protracted displacement. Many long-running conflicts lead to displaced populations being hosted in neighbouring countries for long periods. One of the UK’s policy objectives is to change the type of support offered to long-term displaced people, to help them integrate locally and reduce their likelihood of secondary displacement. This entails moving beyond humanitarian assistance and providing them with access to public services and livelihood opportunities, through burden-sharing arrangements with host countries (Compacts). The UK has been actively involved in the development of Compacts with Jordan and Ethiopia – countries with large, long-term refugee populations.

• Humanitarian support and protection. Life-saving humanitarian aid to refugees and internally displaced persons is a long-standing feature of DFID’s humanitarian work. It is sometimes accompanied by protection activities for vulnerable migrants, such as promoting human rights awareness among national authorities, information campaigns about the risks of irregular migration and related support options, search and rescue operations at sea and assisted voluntary returns.

• Programming to counter people smuggling, trafficking and modern slavery. Both DFID and the CSSF are exploring options for a security and justice response to these challenges. In addition, there is long-standing although small-scale Home Office, FCO and National Crime Agency programming in this area. For instance, “Operation Invigor” provides a strategic framework for National Crime Agency projects to tackle organised immigration crime. In Nigeria, the agency has been providing support to strengthen the border force and establish an anti-human trafficking Unit. And in Ethiopia, the FCO has been helping to strengthen the government’s capacity to investigate immigration crime.

• A “migration theory of change” developed by DFID’s Migration Department also includes programming designed to promote “safer and well-managed regular migration”. In its internal documents and cross-government dialogue, DFID has held to the position that regular migration can be beneficial for development. DFID does not consider regular migration into Europe in its research or plans, but is currently considering programming that strengthens regional migration options within Africa.

We found programmes of these types in a number of internal documents that listed migration-related programmes. In the absence of a shared definition of “migration-related” aid programming (something the government is currently working towards), we found these documents to be inconsistent. They did not enable the UK government, or us, to draw conclusions about the portfolio, or its expenditure, with any level of precision.

Several government-produced lists of migration-related programming feature programmes with uncertain causal links to the root causes of migration. These programmes may affect irregular migration patterns over the long run by changing the context in which people decide whether or not to migrate. However, given the complexity of the factors involved, it is not possible to predict the nature or magnitude of these effects. Many programmes have not been designed to achieve or measure migration effects, and the value of including such programmes in the migration portfolio is questionable.

The UK’s contribution to the global approach to irregular migration

Aware that the influence of UK-funded programmes on irregular migration patterns is necessarily limited, the UK government has put considerable effort into shaping the international approach. We did not independently assess the outcomes of its influencing work. However, we note that stakeholders from across the departments – as well as in UK missions overseas – believe that close cross-government coordination has given the UK a strong voice internationally.

Under the umbrella of the National Security Council, DFID’s Migration Department leads a cross-government working group on the “Global Agenda”. DFID was assigned this role in part because of its established relationships with the two leading multilateral bodies, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The working group has contributed to a range of international events through round-table contributions, formal submissions and behind-the-scenes influencing. In the lead-up to two international events on migration in September 2016, the UK was represented by a joint delegation of directors from the FCO, DFID and the Home Office, which the UK mission in New York (as well as the directors and other government staff) said contributed significantly to the effectiveness of the UK’s influencing work.

The government moved quickly to identify the areas where it wished to play a leadership role, based in part on the UK government’s own programming focus and practice, and to establish its influencing objectives. Although these objectives have developed over the past two years (most recently in the light of the Prime Minister’s three “migration principles” of September 2016), some core elements have remained consistent. The most important continuous focus has been on promoting a new approach to protracted displacement, with an emphasis on access to employment and education, and the idea of national Compacts. This work started in 2015 and continues today, now linked to the Prime Minister’s principle that refugees should claim asylum in the first safe country they reach.

The UK’s influencing objectives were framed by four “red lines”. Specifically, the UK government was careful not to commit to:

• any requirement for the UK to increase resettlement numbers

• mandatory resettlement programmes or compulsory burden sharing

• any blurring of the distinction between refugees and economic migrants

• any commitment to expanding legal migration options into Europe.

Respondents and internal UK government documents claim a number of influencing successes – most prominently around the national Compacts of Jordan, Lebanon and Ethiopia. Within the scope of a rapid review, it has not been possible to independently verify these claims, but we do recognise them as a product of constructive cross-departmental cooperation and the clarity of the government’s influencing objectives and red lines.

National Compacts stand out in the early thinking on migration-related programming

Among the responsible departments, planning for a new migration-related aid portfolio is at an early stage. In the absence of clear evidence on what works, the idea of national Compacts with countries with large refugee populations is an innovative idea. As we explore in the next section, it is a potentially important advance in the aid response to protracted displacement, and a means of helping both refugees and host communities while reducing further displacement. Humanitarian aid and protection interventions are also relevant and important.

At this stage, the other possible approaches are much less clearly articulated. For example, the government sees value in policy work to increase regional labour mobility, in recognition of the potentially positive effects of migration on development in source countries, and on the assumption that the regularisation of regional migration may reduce migratory pressures on Europe. However, the nature of the UK contribution has yet to be determined, and the net effects of such policies on irregular migration patterns to Europe are unknown. Similarly, the government recognises there is value in targeting populations with a known propensity to migrate (such as groups at risk of secondary displacement) but the unpredictable nature of migration often makes such targeting very challenging.

Effective programming on the root causes of irregular migration would need to be based on a strong understanding of the conditions and individual traits that influence migration decisions. Research that builds such necessarily localised understanding is needed but currently sparse, and programming that is informed by such understanding is not yet common.

Options for targeting potential migrants

Studies of the profile of migrants suggest that they are more likely to be younger, unmarried and male, living in urban areas and with social ties to diaspora communities. Compared to the rest of the population, they tend to have higher incomes and be more entrepreneurial, productive and risk-taking.

A DFID internal “think piece” has explored how Africans with a propensity to migrate irregularly might be offered alternatives to undertaking the risky central Mediterranean journey. These alternatives included regional labour markets across Africa and the Middle East, and the provision of training in skills that are in demand internationally (such as in health care), with the possibility of gaining temporary permits to work in Europe at the conclusion of their training. For the time being, however, the UK’s “red lines” rule out initiatives that involve expanding regular migration options into Europe.

DFID is investing in data and research, but there are still substantial knowledge gaps

DFID has invested in building up data on migration patterns, in the central Mediterranean and elsewhere. It is a key funder of IOM’s “Displacement Tracking Matrix” in Libya and worldwide, and has agreed to fund another data-gathering programme by a consortium of non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

DFID also funds a range of migration-related research. The two most substantial programmes are:

• Migrating out of Poverty: a £6.4 million, seven-year research programme that preceded the current migration “crisis”. It focuses on the relationships between intra-regional migration and poverty reduction.

• Protracted Forced Displacement Research: a £10 million programme through the World Bank and UNHCR. It focuses on labour markets and self-reliance, social protection and targeting, basic services and utilities, institutional solutions, and gender and social inclusion.

The CSSF has commissioned a study on people smuggling and trafficking in East Africa (£116,000). We have not seen examples of other departments funding migration-related research.

While the research and evidence collection activities that we have reviewed are relevant and of good quality (a point acknowledged by stakeholders inside and beyond the UK government), the knowledge gaps remain substantial. Rather than waiting for the research to yield results, DFID’s practice is to build research and evidence-collection into its programming. For example, in Ethiopia, DFID’s new migration programme takes an adaptive approach, and the programme budget includes a significant amount for research that is to be undertaken in parallel to programme delivery to inform its continuing development. In a field where much is still unknown, such an experiential learning approach is appropriate.

The available evidence challenges some of the assumptions behind UK aid programming

We found that the government uses data on irregular migration patterns to inform programming. However, possibly given its early stages, we did not see equivalent use of evidence on the causes of irregular migration directly influencing programming.

One reason is that the research is very recent and will take time to absorb. Another is a pattern of research findings which questions existing approaches, without being able to offer practical alternatives. For example, while the UK Aid Strategy states that economic growth helps to “reduce poverty, and also to address the root causes of migration,” the available research shows a more complex relationship between poverty and migration. As migration under distress costs money, it is generally not an option for the very poorest in developing countries. As incomes rise, however, aspirations may increase faster than livelihood options, while the cost of migration becomes more affordable, leading to increased migration. This is supported by evidence that emigration from developing countries tends to rise as they progress towards middle-income status, before falling away once per capita income surpasses US$ 7-8,000 (purchasing power parity).

Such research findings are among the challenges facing the departments in designing a relevant aid response on irregular migration. It is clear that UK aid programming on the economic causes of migration may not on its own reduce irregular migration – but it is less clear what would achieve this.

Conclusion on relevance

The responsible departments remain at an early stage in formulating a relevant aid response to irregular migration in the central Mediterranean. There is as yet no agreed list of migration-related programming, and therefore no data on overall spend. Few programmes operating at the moment were designed with specific migration objectives, and many programmes that have a newly assigned migration label are not well aligned with research findings that point to the complex relationship between poverty and migration. Further work is required to set out clear principles to underpin the government’s migration strategies and to develop a strong and localised understanding of migration drivers that would enable programmes to apply these principles to specific contexts. Investment in research and evidence-collection within new UK aid programmes aimed at reducing irregular migration is a relevant and appropriate response to current evidence gaps about what works in this area. Among the areas where programming is being developed, the idea of national Compacts stands out as the most important innovation.

Findings - Efforts to deliver effective programming

This section first looks at the government’s efforts to build migration-related programming capacity across departments and in the EU. We then look at each of the three case-study countries we have considered in this review and briefly discuss the CSSF. We conclude with a few observations about value for money in the context of the UK’s migration-related programming.

The government moved quickly to address UK and EU capacity constraints

Following the rapid increase in refugees and other migrants entering the EU via the eastern Mediterranean in early 2015 (rather than the spike in arrivals via the central Mediterranean in 2014), the UK government has been building up its capacity to respond to the challenges. Within the UK, the starting capacity was modest. The government had relatively few officials with long-standing migration expertise, and those who did were rarely experienced in aid programming. Moreover, key departments – specifically the Home Office and DFID – had little history of cross-departmental engagement on migration-related issues. The government has taken steps to address both issues. A high turnover of staff added to the challenge, as did the sense of urgency of the “crisis”: in interviews, government stakeholders acknowledged that much of the initial strategy and planning work had been done in haste, and was now being revisited.

The Home Office is the lead department for migration policy. In 2016, a cross-government Migration Steering Group was established, co-chaired by the National Security Adviser and the Second Permanent Secretary from the Home Office.

• Within DFID, a four-person surge team on migration was added to DFID’s Policy Division in early 2015, to respond to the situation in the eastern Mediterranean. This team has grown into a Migration Department with 20 staff, which manages a number of humanitarian programmes and leads the UK’s international influencing work. There are also staff assigned to migration issues within the Africa Regional Department, the Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department, the Europe team, the Humanitarian Policy and Partnerships team and the Research and Evidence Division.

• The FCO-DFID North Africa Joint Unit includes several staff assigned to regional migration policy and programming. In addition, the FCO has a Mediterranean Migration Unit of six staff which includes a Migration Envoy and is located within Europe Directorate. The cross Whitehall Africa Strategic Network Unit in Africa Directorate oversees FCO Migration and Modern Slavery programming across Africa. The FCO has also deployed two specialist Migration Policy Advisers while a number of core embassy staff have migration as part of their broader job remit.

• The Cabinet Office has a senior adviser on migration.

• Within the Home Office, ODA-funded projects are managed by individual business areas. Coordination is provided jointly between the International Directorate and the Directorate for Finance and Estates. The International and Immigration Policy Group leads on international migration policy and strategy. There is a diversity of migration-related projects managed from across the Home Office, including by the Immigration and Border Policy Directorate, Border Force, Office for Security and Counter Terrorism, Immigration Enforcement and the Modern Slavery Unit.

Under the Migration Steering Group there are regular director-level meetings and several working groups covering different geographical and thematic areas. Although not all working groups are equally active, key informants from the participating departments report that these mechanisms have contributed to mutual understanding of the different departmental agendas and priorities and helped to identify common ground to inform programming and international influencing.

The UK has also helped to enhance the capacity of the EU Trust Fund for Africa. The UK’s focus has been on improving project selection processes, increasing the use of evidence and contextual analysis, ensuring conflict sensitivity, promoting regional cooperation, and improving the focus on results management and value for money. The UK has also pushed for greater focus on source countries, particularly in the Horn of Africa.

Against a challenging backdrop, we find that the government has achieved quick progress in building capacity to support its aid response, including putting in place relevant cross-departmental coordination structures and processes. We also note that the UK has made a positive contribution to the capacity of the EU Trust Fund for Africa.

Ethiopia: an innovative approach centred on the idea of a Jobs Compact

The Horn of Africa is the UK’s priority for addressing movements by irregular migrants and refugees through the central Mediterranean. This is an area of strategic importance for the UK and the source of significant numbers of asylum seekers. Within the Horn, Ethiopia is a key partner country. It has long had a liberal asylum policy, making it the largest host country for refugees in the region.

Ethiopia is a major host country for refugees

Ethiopia maintains an open-door asylum policy, providing protection to groups fleeing regional conflicts. As a result, it is one of the largest refugee-hosting countries in Africa, with close to 780,000 refugees in 2016. Most of the refugees are fleeing conflict and repression in South Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea and Yemen.

The majority are housed in 25 camps across the country. While Ethiopia is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, it maintains reservations in respect of freedom of movement and the right to work. This means that refugees must seek permission to leave the camps and their access to employment is limited. The lack of livelihood opportunities means that some refugees seek opportunities for secondary irregular migration through the central Mediterranean route.

The UK emerging aid response to irregular migration in Ethiopia has been active and innovative. It is centred on the idea of finding durable solutions that include access to employment and education for long-term refugees, with shared responsibility between the host country and donors. The UK government has actively promoted this approach with the Ethiopian authorities and other donors. It has helped reframe the response to protracted displacement from repeated humanitarian aid towards a combination of short-term relief and more sustainable development interventions designed to promote local integration. This has been facilitated by a shift to multi-year funding, which internal reviews have shown delivers better value for money.

The UK government’s strategy for irregular migration in Ethiopia

The UK government has a cross-government Ethiopia migration strategy (2016, unpublished) with seven components:

• building a stronger evidence base

• developing a Jobs Compact

• strengthening law enforcement capacity (not ODA-financed)

• refugee protection

• facilitating legal migration to the Gulf States

• building a returns approach

• strengthening regional approaches to border management and refugee issues.

DFID is currently preparing for the implementation of a new Refugee and Migration Business Case, with a proposed budget of £125 million over five years. Its objective is to improve the lives and livelihoods of both refugees and host communities, particularly in underdeveloped and peripheral regions. The programme will promote both protection and economic opportunities for refugees, so that they are less likely to resort to irregular migration. Proposed activities include shelter and protection, support for basic services (health, education and water and sanitation), livelihoods and vocational training, and a £25 million challenge fund to attract innovative proposals for research and programming from NGOs and companies. There is also a contingency fund for spikes in humanitarian need, which helps protect the longer-term investments from being diverted to emergency needs.

DFID is also developing an £80 million Jobs Compact, inspired by the Jordan Compact. In exchange for the Ethiopian government granting refugees access to parts of the labour market, DFID will help to leverage international finance for the development of a series of industrial parks. The Compact is led by the Wealth Creation and Climate Change team in the DFID country office, rather than the Humanitarian team, which is in itself an innovation. The objective is to create 30,000 jobs for refugees, as part of much wider job creation for host communities.

The Jobs Compact is still under negotiation, but was presented by the UK and Ethiopian Prime Ministers at the September 2016 Leaders’ Summit on Refugees in Washington. The World Bank, the European Investment Bank and the European Union indicated support to the Jobs Compact in principle, with combined pledges of over $550 million.

As a new approach, the Compact is as yet unsupported by evidence of what works in preventing secondary displacement, and it rests on a number of assumptions that will need to be tested. To reach the intended scale, the scheme will have to attract a considerable amount of finance from both donors and the private sector. While the infrastructure for industrial parks will be donor-financed, the actual jobs will be created by the private sector. Industrial parks across Africa have a poor record on job creation, and the target may be overambitious as DFID has no previous track record of supporting job creation at this scale. UK government respondents argued that Ethiopia offers a more promising environment for industrial development than most African countries and that there has been interest from Asian investors in the country’s garment sector (despite Ethiopia’s low ranking on the World Bank’s “ease of doing business” index). However, there have been recent protests involving damage to foreign-owned businesses. If the programme is successful in creating jobs at scale, there are questions as to whether the Compact might inadvertently increase irregular migration into Ethiopia or, by raising the effective cost of granting asylum, create a disincentive for Ethiopia to maintain its current open-door policy. Careful baselining and monitoring will be essential for measuring impact and identifying any unintended consequences.

National Compacts

The UK government has been influential in promoting Compacts as a potential solution to protracted displacement. We have looked at the Compacts that have been agreed in principle in Jordan and Ethiopia.

There is also a Compact in Lebanon, and Compacts are reportedly under discussion in Kenya and Uganda.

There are a number of attractive elements to the Compacts concept:

• It changes situations of protracted displacement from a humanitarian challenge to a development challenge by combining aid programmes with initiatives to influence national policies in refugee host countries in pursuit of durable solutions.

• It can target specific groups with a known propensity for secondary displacement, while also offering wider benefits to host communities.

• The content of each Compact can be tailored to the needs of each country context, and develop as a better understanding emerges of the needs and aspirations of the target groups. According to the UK missions in Brussels and Geneva (as well as staff across the UK government in London), the responsible UK departments worked quickly, effectively and jointly to promote the idea of a Compact for Jordan, which was agreed in outline between the European Union and the government of Jordan within a few months (in early 2016). Under the Compact, Jordan receives significant financial and technical support and preferential access to European garment markets, so as to encourage the creation of more jobs. In return, the Jordanian government agrees to allow refugees access to parts of the country’s labour market. This reciprocal approach became the model for a Jobs Compact with Ethiopia.

Libya and the Mediterranean: a limited response in a difficult environment

Libya is a key country for the central Mediterranean migration route, as the main departure point for irregular migrants attempting the sea crossing to Europe. People smuggling is not new to Libya, but the collapse of the Libyan state and the rise of rival militias have enabled it to flourish. Libya is also home to between 700,000 and one million migrants and refugees, many of whom are vulnerable and in need of assistance. Libya is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol. The country does not recognise the right to asylum and a joint UNHCR-IOM statement of February 2017 confirms that “it is not appropriate to consider Libya a safe third country”. All irregular migrants detained by the Libyan government – including those intercepted or rescued at sea within Libyan territorial waters – are held in detention centres, often indefinitely, where they face overcrowded conditions and are at risk of abuse and extortion.

UK aid programming in Libya is constrained by difficult and volatile security conditions, and is therefore small in scale and delivered remotely from Tunisia. Only a small number of implementers are able to operate in Libya (including IOM, UNHCR and the Danish Refugee Council), and only where security permits. The primary focus of UK assistance is security and stabilisation. Migration was added as an objective in September 2015, but the operationalisation of this objective has started only recently.

The main migration-related activities are humanitarian support for refugees and irregular migrants in detention centres (including non-food items and water and sanitation facilities), training for the Libyan coastguard to conduct search and interdiction operations, and support for a number of activities delivered by IOM, including assistance for irregular migrants to return to their country of origin. There is also emergent work on protection of women and girls. Given the modest size and focus of the UK aid programmes in Libya, they are likely to reach only a small proportion of the migrants with humanitarian and protection needs.

UK migration-related aid programming in Libya and the

central Mediterranean

The responsible departments provided us with the following details of UK migration-related aid programmes in Libya and the central Mediterranean. We note that they had some difficulty with assembling a list of programmes and that, at the central level, none of the stakeholders we spoke to had a good overview of which departments are engaged in which activities. In the absence of clarity within the UK government, we received some of this information from implementing partners.

• The Safety, Support and Solutions Programme for Refugees and Migrants in Europe and the Mediterranean region is a DFID-funded regional programme (£38.3 million for 14 months in 2016-17, of which £5.1 million is earmarked for operations in Libya) with multiple components, including humanitarian assistance for migrants and refugees in Libya, a contribution to a UNHCR regional appeal for migrants and refugees, a women and girls protection fund (still under design) and a £1.5 million contribution to IOM to support data gathering, capacity building for the Libyan coastguard and direct support to an estimated 8,350 irregular migrants in detention (medical and psychosocial support, as well as non-food items and hygiene kits). The design originally included support to NGOs for search and rescue on the Mediterranean, but this was not approved.

• A DFID Humanitarian Programme for Libya (£2 million for 2016-17), which includes a component that provides health and related services in migrant detention centres, as well as human rights focused training for guards.

• A CSSF contribution (€100,000 for 2016-17) to an EU programme of capacity building for the Libyan Naval Coastguard.

• A CSSF project (£1.7 million for 2016-17) that funds IOM to improve conditions in four detention centres, provide capacity building to relevant Libyan staff and support “assisted voluntary return” to detained and other illegal migrants’ countries of origin.

These programmes are not designed to reduce the numbers of people attempting the sea crossing, and are unlikely to affect these numbers in a material way (though the support to the Libyan coastguard may reduce the numbers arriving in Europe). They have more limited objectives around improving conditions in detention centres and providing some irregular migrants with an option to return home. These aims fit within the overall goal of protecting vulnerable migrants.

However, we do have several concerns about the combination of programming.

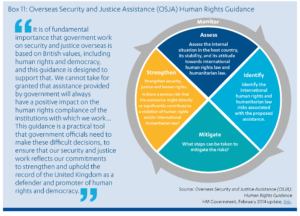

• The UK government supports the EU work to build the capacity of the Libyan coastguard. This support aims to increase the likelihood that refugees and other irregular migrants will be intercepted in Libyan territorial waters. These people are then placed in detention. While reducing the number of deaths at sea is vital, we are concerned that the programme delivers migrants back to a system that leads to indiscriminate and indefinite detention and denies refugees their right to asylum. We are also concerned that the responsible departments were not able to provide us with evidence that an Overseas Security and Justice Assistance human rights risks assessment or equivalent was carried out prior to the support to the Libyan coastguard, as required by the government’s own Human Rights Guidance. This guidance does not rule out support to the Libyan coastguard, but it does require careful assessment and management of human rights risks. Such an assessment should be carried out early enough to allow it to feed into project or programme design. Design documents describing aid interventions should describe both the risks and benefits of an intervention, alternatives considered, and an articulation of the risk appetite. While the government informed us that as this was a contribution to an EU project it would be sufficient to rely on EU assessment systems, we were not provided with information about these systems or evidence that the analysis had been fed into project design.

• Similarly, we have not seen evidence that the responsible departments and implementing partners have analysed the economic and political conditions surrounding Libya’s system of detention centres in sufficient detail. This is important because thereare credible reports that some Libyan state and local officials are involved in people smuggling and trafficking, and in extortion of migrants in detention. We have not seen data showing if UK support to the detention centres, or the agencies responsible for operationalising this support, has increased the number of detainees. However, we conclude that there is a risk that providing financial or material support – even neutral humanitarian support – to detention centres might create conditions that would lead to more migrants being detained. We are not satisfied that the responsible departments have done enough analysis to assess the requirements of the “do no harm” principle.

• Once detained, a migrant might be eligible for IOM’s “assisted voluntary return” to his or her country of origin. While voluntary repatriation is one of the durable solutions for displaced people, there is a risk that repatriation is not truly voluntary if migrants are only faced with the alternative of detention in poor conditions. We note that IOM-assisted return programmes from Libya have been challenged on this basis in the past. The government says it is working with IOM and other organisations to ensure that “assisted voluntary return” is part of a broader approach seeking to identify alternatives to indefinite detention, but this work is at very early stages and we have not seen evidence that such alternatives exist already.

• We note that the government is considering further work on police capacity building through the National Crime Agency. We emphasise the importance of conducting a thorough analysis of human rights and economic and political conditions and feeding this into project design where security and justice interventions are being considered.

Some of the UK government stakeholders we spoke to acknowledged these concerns, but argued that UK government policy and the difficulty of operating within Libya meant that no alternatives were available. While the choices are certainly limited, spending departments still need to satisfy themselves that their programming choices are not causing inadvertent harm. The need for the risk of unintended harm to be analysed, incorporated in programme design, monitored and managed is particularly important now that the EU has committed to rapidly expand the cooperation with Libyan authorities in its Malta Declaration of 3 February 2017.

Nigeria: as yet no clear migration portfolio

We chose Nigeria as a country case study for this review because it is currently the largest source country for irregular migrants coming to Europe via the central Mediterranean and because the initial documentation we received suggested a substantial amount of migration-related programming. In practice, we found that responding to irregular migration through the central Mediterranean route was not a strategic objective in DFID’s business plan for Nigeria and was not a significant focus of aid programming at the time of the review.

The responsible departments in Nigeria have made various attempts to identify migration-related programming from their current portfolio but, in the absence of agreed criteria, have yet to settle on a consolidated list.

Programmes identified as migration-related included humanitarian programmes in the north of the country that are supporting Nigerians affected by the Boko Haram insurgency. While this support is relevant to migration at some level, UK government documents note that Boko Haram is not considered to be a driving factor for irregular migration along the central Mediterranean route. DFID is also planning for a programme that will support the “migration and modern slavery” pillar of the National Security Council country strategy for Nigeria. It will tackle the challenge of Nigerians being trafficked into Europe for sex work or bonded labour. The National Crime Agency (in partnership with other UK agencies) is also providing some capacity-building support to the Nigerian government on border security, under a CSSF project.

In one government document we were provided with, the majority of programmes identified as migration-related are ongoing economic development programmes, with a total budget of over £600 million over the 2011-19 period. These include programmes that aim to create youth employment and promote economic reforms (for example trade policy, the oil and gas sector), a stronger business and investment climate, and access to finance for the financially excluded.

The latter group of programmes may be relevant to their primary objectives, and also have causal links to the root causes of migration. However, these causal links are uncertain and at best long-term, and the government should be cautious in assigning direct attribution. The programmes were not designed with migration objectives in mind, and do not target specific groups of people with a known tendency to migrate. The available evidence suggests that we cannot assume economic growth of itself decreases the tendency to migrate; indeed, the reverse may be more likely. DFID’s own documents suggest that creating economic opportunities for the poorest, which is DFID’s objective, is unlikely to influence the choices of potential migrants, who – according to UK government documents – are more likely to be middle-class. We therefore conclude that DFID Nigeria is still at an early stage in identifying how its aid programmes might influence the socio-economic drivers of irregular migration.

The CSSF’s engagement on people smuggling remains at an early stage

The CSSF, which operates under the authority of the National Security Council, offers a flexible fund of over £1 billion per year for addressing UK objectives around conflict, security and stability, combining both ODA and non-ODA. Migration has only recently been added to its strategic framework and it remains at an early stage in developing migration-related programmes. As of the end of 2016, it had planned £28 million of migration-related programming for Africa, most of which is still in design.

The CSSF has been exploring the option of a wider criminal justice response to people smuggling and trafficking, but acknowledges that it faces a number of challenges. National borders in the Sahel region of Africa are porous. Success at intercepting irregular migrants at any given point would simply cause smugglers to take other routes. The limited available evidence suggests that people smuggling is done by loose networks of actors, rather than hierarchical criminal organisations , making them difficult to disrupt. They are often deeply embedded in local communities along migration routes and work in collusion with border agencies, police or security forces. People smuggling represents an important source of income for public authorities, militias and tribal groups, and capacity building in criminal justice has a limited record of success in the face of strong vested interests. There is also a risk that building up law enforcement capacities in countries with poor human rights records might do harm to vulnerable migrants and refugees.

Furthermore, most CSSF programming is done at country level, while people smuggling is a regional challenge. In so far as CSSF works regionally (ie in East Africa), its regional set-up does not match the migration routes (ie from the Horn of Africa and West Africa to Libya). The CSSF acknowledges that it is not yet in a position to target its resources strategically along the smuggling “value chain”.

The CSSF is appropriately cautious in developing larger-scale programming on people smuggling and trafficking. For the time being, its contribution remains small in scale.

The Migrant Response and Resource Mechanism in Agadez, Niger

When asked for examples of successful programming for irregular migrants on the move, several UK government stakeholders mentioned DFID’s funding for the operational scale-up of an IOM office in Agadez, Niger. In Agadez, located on a traditional Saharan trade route, people smuggling has become an important element in the local economy. IOM’s Migrant Response and Resource Mechanism in Agadez provides migrants with information about the risks of the onward journey, together with an offer of assistance for migrants who wish to return home. The government describes the initiative as a success, largely on account of IOM arranging 1,595 and 4,788 voluntary returns in 2015 and 2016 respectively.

However, in interviews, two prominent experts questioned the significance that had been attributed to the voluntary return figures. They pointed out that if the initiative had significantly disrupted people smuggling operations, the people smugglers would have avoided Agadez by diverting to another route. There were suggestions that many of those who had taken up IOM’s offer were already on their way home, as part of a regular pattern of circular migration. Where migrants do decide to abandon their journey, there is no guarantee that they will not attempt to migrate again, once they have replenished their savings.

These comments confirm that many variables need to be considered when monitoring the effectiveness of programming on people smuggling and irregular migration.

Ensuring value for money

Value for money should be an important consideration in all forms of aid programming. We found that DFID is giving due attention to value for money management techniques in the preparation of its migration-related programmes. The business cases that we reviewed all contained value for money analysis and options appraisals. The business case for the £125 million Refugee and Migration Programme in Ethiopia – the largest programme we reviewed – was assessed positively by DFID’s

Quality Assurance Unit (albeit with the recommendation to make greater use of value for money monitoring). We encountered various efforts to secure economy in procurement and programme delivery. For example, in Ethiopia, DFID chose to redirect part of its humanitarian funding straight to NGOs, rather than via UNHCR, in order to achieve lower overheads. The delivery partners we spoke to reported that they are closely scrutinised and under pressure to deliver value for money. For the CSSF, the small and fragmented nature of its irregular migration portfolio suggests that there is scope for strengthening value for money. In this context, we note the intention to increase the unit size of programmes, thereby reducing transaction costs and increasing economies of scale and strategic impact.

However, the larger value for money issues in the migration area are the lack of a shared understanding of the nature of the challenge, insufficiently clear portfolio objectives, and the lack of evidence of what works. Until there is greater clarity on the problem that needs to be solved and on feasible ways in which this could be achieved, it is difficult to determine what “value” to assess. Only once a set of credible programming options emerge will it be possible to begin serious analysis of how to deliver them cost-effectively.

Conclusions on effectiveness

Our three country case studies cover three different types of programming and lead to different conclusions as to their potential effectiveness.

In Ethiopia, the Jobs Compact and the associated portfolio of both humanitarian and development interventions offers good potential to benefit both refugees and host communities. There are a number of significant assumptions underlying the approach that are, as yet, untested. We cannot say at this stage whether it will succeed in creating jobs on a scale sufficient to deter secondary migration. There are reasons to be cautious given the innovative nature of programming, the level of ambition

and the relatively poor track record of industrial parks in Africa. Nevertheless the Compact remains the most promising idea yet for shaping the UK aid response.

In Libya, where the operating environment severely constrains choices, the UK has identified some programming options with the potential to improve some of the conditions for migrants in detention. However, we are concerned about the risk that UK aid is contributing to a system that prevents refugees from reaching a place of safe asylum.

In Nigeria, while there has been some attempt to link existing programming to migration, the link is too complex to allow for any consideration of effectiveness.

The CSSF provides funding, in line with the NSC strategy, to tackle people smuggling and trafficking but, in the face of substantial practical challenges, has not yet developed a clear strategy that underpins how aid programming might contribute to this work.

Conclusions & recommendations

Conclusions

The UK aid response to irregular migration in the central Mediterranean remains at an early stage. The responsible departments are under considerable pressure to come up with a portfolio of relevant programming. Their efforts to do so are constrained by a number of difficulties:

• conflicting views on what the migration “crisis” consists of

• the unpredictability of migration flows

• a lack of evidence on what influences migration decisions, particularly in the short term.