The cross-government Prosperity Fund

Executive summary

The Prosperity Fund is a new cross-government aid fund, under the authority of the National Security Council, that promotes economic reform and growth in developing countries. With a planned budget of £1.3 billion between 2016 and 2021, the Fund is a major new addition to the UK aid programme and part of a wider rebalancing towards economic development. It is intended that it will contribute to a reduction of poverty in developing countries and also create opportunities for international business, including UK companies.

The Prosperity Fund is still in its development phase. It has made significant progress in a short time frame and has responded positively to two independent reviews it commissioned which raised a number of critical concerns. Key aspects of how it will operate require further development and refinement. We have conducted a rapid review of its emerging structures and processes, to determine whether they are adequate to ensure effective programming and value for money. An Independent Commission for Aid Impact rapid review is a short, real-time review of an emerging issue or area of UK aid spending that is of particular interest to the UK Parliament and public. While we examine the evidence to date and comment on issues of concern, our rapid reviews are not intended to reach final conclusions on performance or impact, and are therefore not scored.

Overview of the Prosperity Fund

The Prosperity Fund was established to promote reforms and investments needed for economic growth in key partner countries, particularly emerging markets such as China, India, Mexico, Indonesia and Brazil. It will target thematic areas that promote greater competitiveness, such as improved business regulation, more efficient markets, free trade, anti-corruption, clean energy, and health and education services.

The Fund is also intended to create opportunities for international business, including UK companies, as a secondary benefit. Such opportunities may come from direct involvement in delivering Prosperity Fund projects, or from the resulting increases in investment opportunities or bilateral trade; however, most of the resources for the Prosperity Fund (over 97%) are Official Development Assistance (ODA). This requires each transaction to be ‘administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective’.1

The Prosperity Fund’s internal Operating Framework states that all expenditure will also be governed by the International Development Act, which requires that activities are likely to contribute to poverty reduction.

The Prosperity Fund is scaling up rapidly, from £55 million in 2016-17 to a planned £350 million expenditure of ODA during 2019-20 and 2020-21. Most of its spending will be in the form of large (over £50 million) or medium-sized (£10-50 million) multi-annual projects. Many of these projects will in practice be programmes covering multiple countries and thematic areas, so that individual interventions may be both much more

numerous and also much smaller in size.

The Fund has identified a set of priority countries in which there are opportunities to support prosperity, based on the number of people living in poverty and the potential for inclusive economic growth. A number of sectors and issues have also been identified where the UK has particular expertise to offer, for example financial services or trade reform. The analysis took into account areas where the UK private sector is assessed as playing a global leadership role, such as in financial and business services, infrastructure, pharmaceuticals and healthcare. The priority countries are those with both growth potential and strategic importance to the UK, with the highest priority going to ODA-eligible middle-income countries.

Any government department can bid for Prosperity Fund resources. Bids are assessed on their technical merit for their potential to deliver both primary development impact and secondary benefits to UK companies. There have been two bidding rounds to date. Nineteen concept notes were approved to proceed to full business case development (the final approval stage), with a combined budget of up to £1.1 billion. The Prosperity Fund may scale back or not proceed with some projects at business case stage. A third and final round will take place in the first half of 2017, after which all of the Fund’s resources (bar £40 million) will have been allocated.

Emerging issues and challenges

Our summary of findings by review question is at Annex 1. We acknowledge that the Prosperity Fund is complex and ambitious and has undergone a rapid process of set up. We have identified some important emerging challenges for the Fund in building and delivering a strategic portfolio that matches UK government priorities.

Combining primary purpose and secondary benefit:

A major challenge facing the Prosperity Fund is demonstrating impact and value for money against both its primary purpose (which must be economic development and welfare) and its secondary benefits to international and UK businesses. The concept notes that we reviewed contained limited detail as to how either objective will be achieved. The likelihood of reducing poverty is a requirement of the International Development Act. We are particularly concerned that, although the scoring guidance states that this is a condition, no threshold is specified. Nor is it clear that a sufficiently demanding threshold for this condition has been applied in practice. We also note that internal scoring criteria and guidance on secondary benefits refer only to strengthening opportunities for UK trade and investment.

Portfolio development and measurement

The Prosperity Fund is trying to build a strategic portfolio of programmes through a competitive bidding process, which creates a number of challenges. While it has set out broad thematic and geographical priorities, the actual distribution of resources will be determined by which bids are received and pass technical scrutiny. There is a risk that this results in a fragmented portfolio that is unable to achieve portfolio-level strategic impact that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Procurement issues

Each Prosperity Fund programme will propose its own approach to delivery, with some activities procured from commercial firms. The expectation among key stakeholders is that large firms with global reach will be awarded contracts, with smaller firms and non-government organisations limited to subcontracting. The Prosperity Fund is keen to avoid fragmentation and high transaction costs, but if this results in lengthy delivery chains, it may impact on value for money. We are also concerned that some of the potential suppliers of services to the Fund have been providing advice (often informally at embassy/high commission level) on programme design in ways that are not sufficiently transparent and could give rise to conflicts of interest.

Governance

The Prosperity Fund was initially directed by the Treasury to use a governance structure modelled on the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund, with no structured assessment as to whether this was the right model. This has since been adapted in a number of useful ways, following a review by the Infrastructure and Projects Authority and with reference to learning from other cross-government funds.However, there is still a lack of clarity between governance and biddings roles, leading to a perception that some departments may have privileged access to the Fund’s resources, although all government departments are entitled to bid.

Delivery capacity

Given the speed at which participating departments are expected to move from concept notes through to full business cases and implementation at scale, the lack of delivery capacity in key departments and diplomatic posts presents some serious risks. The Prosperity Fund is supporting departments with training, guidance, advice and, in some cases, with additional contractors, to improve delivery capacity.2 For departments that have not managed large aid programmes before, there is very little time to put in place the required systems and capacities.

Results measurement

The Prosperity Fund is subcontracting its monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning functions to contractors. While this is considered good practice for evaluation, there is a risk in contracting out these services in their entirety to external suppliers. There is a risk of poor integration with management and learning at portfolio and programme levels.

Transparency

Despite the UK government’s public commitment to promoting transparency in international aid, the Prosperity Fund has not operated so far in a fully transparent manner. There is limited information in the public domain about its strategy and ways of working, and its communications and external engagement started late and have not been sufficient.

Recommendations

As this is a rapid review of a fund that is still under design, we have not reached final evaluative judgements or scored the Fund’s performance to date. However, we make a number of recommendations for how the Prosperity Fund’s processes could be strengthened.

Recommendation 1

The government should consider adjusting the planned rate of expenditure of the Prosperity Fund as its delivery capacity develops, if necessary by spending its resources over a longer period. The Fund should consider holding back more resources for allocation in later years, and ensure it has adequate flexibility to reallocate funds between programmes to reflect their performance.

Recommendation 2

The Prosperity Fund should refine its strategic objectives and develop a set of portfolio-level results indicators, to which each programme should align. It should ensure that its monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning services are integrated with management and learning processes at both portfolio and programme levels.

Recommendation 3

For Prosperity Fund programmes spending UK aid, the process for ensuring ODA eligibility should be explicit and challenging. The Fund should ensure that business cases include a plausible strategy for delivering primary purpose and secondary benefits, based on sufficient evidence and analysis, and give adequate consideration to gender equality, in compliance with the International Development Act.

Recommendation 4

The Prosperity Fund should formalise and be more open about its engagement with UK and international firms. It should manage its supplier pool with a view to avoiding conflicts of interest, securing value for money and achieving both primary purpose and secondary benefits.

Recommendation 5

As a new aid instrument, the Prosperity Fund should establish its procedures and report its progress on the basis of full transparency, in line with the government’s public stance on this issue.

Introduction

In November 2015 the UK government announced the creation of a new Prosperity Fund, with a provisional allocation of £1.3 billion between 2016 and 2021, to promote reform and economic growth in developing countries. It is a cross-government fund, to which any government department can bid for resources. It is intended that it will contribute to a reduction of poverty in developing countries and also create opportunities for international business, including UK companies.3

The establishment of the Prosperity Fund corresponds with a renewed emphasis on economic development in the international development agenda. The eighth Global Goal recognises the importance of economic growth, entrepreneurship and employment creation in tackling poverty. There has also been a rebalancing in the UK aid programme, from a strong emphasis on public services during the Millennium Development Goals period, towards promoting economic development and private sector-led growth.

The Prosperity Fund marks a new direction for the UK aid programme in a number of respects. It significantly increases the amount of Official Development Assistance (ODA) available to a range of government departments. It will focus its funding on ODA-eligible middle-income countries, which are not a focus area for DFID support. 4

It is also the first major UK aid instrument to include the provision of benefits to international business, including UK companies, as an explicit, though secondary, objective.5

“We will do more in emerging markets and in middle-income countries to encourage global economic growth… As well as contributing to a reduction in poverty in recipient countries, we expect these reforms to create opportunities for international business, including UK companies.”

National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015, HM Government, November 2015, p. 70.

The Prosperity Fund is still under development. In its first year, 2016-17, it committed £55 million in ODA and £5 million in non-ODA funds on a series of smaller projects across 13 countries and in the South East Asian region.6 During that time it began developing the structures and procedures required for programming a higher volume of funding over the remaining four years of the spending review period. The focus for this review is the development of these structures and processes, rather than the first year of programming.

As of the end of 2016, the Prosperity Fund Ministerial Board has approved 19 concept notes to proceed to full business case but these are still under development and none of the programmes have yet commenced.7

We conducted a rapid review of the Prosperity Fund to assess what progress has been made in putting in place the governance arrangements, systems and procedures required for the Fund to allocate resources effectively and with good value for money. Our review questions are set out in Table 1. We assessed the decisions made to date on the shape of the portfolio and the emerging processes for bidding, funds allocation and assessing results. We also reviewed the concept notes submitted for the first two rounds of bidding (July and September 2016). While it is too early to make final judgements on either the design or the effectiveness of the Prosperity Fund, our objective was to review progress to date and flag any areas of concern, to guide its continuing development. At this early phase of the Prosperity Fund’s development we are not offering a performance rating, as with other Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) rapid reviews.

Box 1: What is an ICAI rapid review?

ICAI rapid reviews are short, real-time reviews of emerging issues or areas of the UK aid spending that are of particular interest to the UK Parliament and public. While we examine the evidence to date and comment on issues of concern, our rapid reviews are not intended to reach final conclusions on performance or impact and are therefore not scored.

Other types of ICAI review include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries, performance reviews, which assess the quality of delivery of UK aid, and learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming.

Table 1: Our review questions 8

| Review criteria | Review question |

|---|---|

| 1. Effectiveness | Are the systems and procedures of the Prosperity Fund adequate to ensure effective programming and good value for money? |

| 2. Learning | Has the design of the Prosperity Fund been informed by learning from other cross-government aid funds and instruments? |

Many aspects of the Prosperity Fund are not yet in the public domain. We have agreed with the Fund not to discuss the detail of individual proposed programmes until they are approved and announced.

Box 2: Methodology

Our methodology for this rapid review consisted of:

- A review of Prosperity Fund documents concerning its governance, management, strategy and objectives.

- A review of the concept notes submitted for the first two rounds of competitive bidding, and of how

they were scored. - Key stakeholder interviews with the Prosperity Fund and participating departments.

- Consultations with external stakeholders, including focus groups with UK development Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and consultation with private businesses including a survey.

Our review was conducted in parallel with an unpublished review by the National Audit Office. We shared interviews and evidence with the National Audit Office. We also drew upon two recent reviews of the Prosperity Fund by the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA).

Overview of the Prosperity Fund

Purpose and function

The Prosperity Fund is intended to promote the economic reform and development needed for growth in key partner countries, particularly emerging markets and middle-income countries such as China, India, Mexico, Indonesia and Brazil. It will support reforms and investment projects that lead to greater competitiveness and economic growth, focusing on areas such as:

- improved business regulation

- more efficient markets

- addressing barriers to international trade

- tackling corruption

- promoting investment in key development sectors such as energy, education, healthcare and digital access.

The Prosperity Fund is expected to create opportunities for international business, including UK companies, as a secondary benefit.9 Such opportunities may emerge from their involvement in delivering Prosperity Fund investments, or from the creation of new investment opportunities or increased bilateral trade.

The Prosperity Fund has produced a high-level theory of change to guide its work (reproduced in the Annex 2).10 A recent update of the theory of change has made the link to eight of the Global Goals, which are themselves also broadly defined.11

Most of the funding for the Prosperity Fund (more than 97%) is designated as ODA. Its internal Operating Framework states that the legal basis for all ODA spending is the International Development Act.12 This means that the Fund may only support activities that are likely to contribute to a reduction of poverty in developing countries, as their main objective (see Box 3).13 The UK government has also been committed since April 2001 to ‘untying’ all UK aid14 – a pledge reaffirmed in the 2015 Conservative Party Manifesto.15 This means that the UK does not insist that its aid be spent on goods and services provided by UK companies.

Box 3: What is Official Development Assistance?

Under the internationally agreed definition, the main objective of ODA spending must be ‘the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries’. 16There is an agreed list of ODA-eligible countries and multilateral institutions. Given the UK’s commitment to spending 0.7% of gross national income on ODA, all aid must meet this international definition. In addition, most UK aid (including the ODA component of the Prosperity Fund) is spent under the International Development Act. Such aid must therefore be ‘likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty’, as well as give due consideration to reducing gender inequality.17

The limits of the International Development Act spending power have never been interpreted by the courts. It is clear from the current breadth of the UK aid programme that many different forms of development assistance are considered as contributing to poverty reduction – including investments that

promote economic development as whole, (which is widely considered a precondition for large-scale and sustainable poverty reduction).18

Since 1 April 2001, the UK aid programme has been completely untied. The UK is one of only a handful of bilateral donors who have untied all aid.19 This means that the implementation of Prosperity Fund programmes cannot formally be restricted to UK companies.

Budget

The original budget by year for the Prosperity Fund is given in Table 2. It shows a rapid scaling up over the next three years, to a maximum of £350 million per year.20 There are substantial practical challenges involved in selecting, designing and initiating this volume of programming in such a short time. In recognition of this, the spending target for 2017-18 is under active review, as part of the risk management of the overall spending profile.21 The implication of this for subsequent spending targets is not yet known, however, key stakeholders have expressed concern that unspent funds will need to be disbursed in the final year, creating a significant value for money risk.

The funding has been earmarked across small, medium and large projects, as follows:

- £550 million for 5-10 ‘big ticket’ projects of £50 million or more

- £370 million for 23-34 medium projects (£10-49 million)

- £160 million for smaller, flexible projects.

It should be noted, however, that ‘big ticket’ and ‘medium’ projects may consist of sets of activities across several countries or subject areas, some of which may individually be small scale, so that there may be multiple activities under each project. Prosperity Fund projects will be multi-year over years two to five. The funding will be allocated in three rounds of awards (called ‘windows’), in 2016 and 2017. By mid-2017, it is anticipated that all the available funding, bar £40 million being held back, will have been allocated.

Table 2: Prosperity Fund planned funding allocation

| Year | Initial budget (£ million) | Non-ODA component (£ million) |

|---|---|---|

| 2016-17 | 55 | 5 |

| 2017-18 | 202 | 8 |

| 2018-19 | 300 | 10 |

| 2019-20 | 350 | 10 |

| 2020-21 | 350 | tbc |

| Total | 1,257 | ≥33 |

Note: The second-year target is under active review. The Prosperity Fund also anticipates an underspend in years 2018-19 and 2019-20. This could leave an overspend in the final year to meet the overall target by the end of 2020-21.

Priority sectors and countries

The Prosperity Fund has identified a set of priority sectors and issues for its programming. These priorities were based on cross-departmental economic analysis of the number of people in poverty and the potential for inclusive growth.22 A number of sectors and issues have also been identified that take account of areas where the UK private sector is assessed as having a global leadership role, such as financial and business services, infrastructure, environmental industries, healthcare and education.23 The former Prime Minister David Cameron’s ‘golden thread’ agenda of promoting open governments, economies and societies as the foundation for inclusion and prosperity is also included.24 Since the referendum on leaving the European Union, the promotion of trade has been given a higher priority by the Prosperity Fund.25

The Fund’s analysis suggests that there are major opportunities for working in ODA-eligible middle-income countries such as Brazil, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, South Africa and Turkey. These are countries where DFID has phased out its traditional forms of bilateral assistance, in whole or in part. Most of the concept notes submitted to date cover multiple countries and/or sectors, giving programmes considerable scope as to where to invest.

Governance

The Prosperity Fund is a cross-government instrument under the authority of the National Security Council (see Annex 1 for the governance structure). The National Security Adviser is the Senior Responsible Owner,26 and the Deputy Director for Foreign Policy in the National Security Secretariat acts as Deputy Senior Responsible Owner and manages the Fund.

Within policy priorities set by the National Security Council, the Fund is overseen by a Ministerial Board, chaired by the Chief Secretary to the Treasury.27 The Ministerial Board sets the strategic direction, reviews and endorses strategic allocations against sector and country priorities and reviews and endorses candidate programmes. 28

A cross-departmental Portfolio Board executes the strategy approved by the Ministerial Board, including recommending which programmes should be endorsed by the Ministerial Board. It also plays a key role in strategic risk management. A cross-departmental Directors’ Group performs an advisory function, providing country, regional and sector views on the strategy and proposed programmes.29 The Prosperity Fund Management Office (PFMO) is a cross-government unit housed in the FCO. It currently has a team of around 25, drawn mainly from the FCO, with five DFID staff and one each from DIT, BEIS and Defra.30 It provides managerial and technical support to the two boards, manages the bidding processes – including reviewing and scoring bids – and supervises the portfolio. It manages a series of contracts with commercial suppliers for monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning services.

The responsibility for delivering Prosperity Fund programmes lies with each recipient department. The lead department on each programme must account for the expenditure according to its own rules. Larger programmes may involve inter-departmental steering committees, potentially with a role for DFID in providing technical support on aid management. Some programmes will be managed from UK diplomatic posts and overseen by inter-departmental boards at the country or regional level.

While individual departments are responsible for programme delivery, the PFMO remains responsible for ensuring that Fund spending targets are met. The PFMO anticipates providing support on forecasting and financial reporting.

Parliamentary oversight of the Prosperity Fund is still evolving. The PFMO anticipates scrutiny by the International Development Committee, the Foreign Affairs Committee and the Public Accounts Committee. Spending departments will also be accountable to their own select committees.

Competitive bidding

The process for allocating funds is set out in the Prosperity Fund’s Operating Framework. There are two underlying principles. First, funding should be allocated towards sector and country priorities identified by the Ministerial Board. Second, a competitive bidding process will be used to identify the best candidates for funding.31

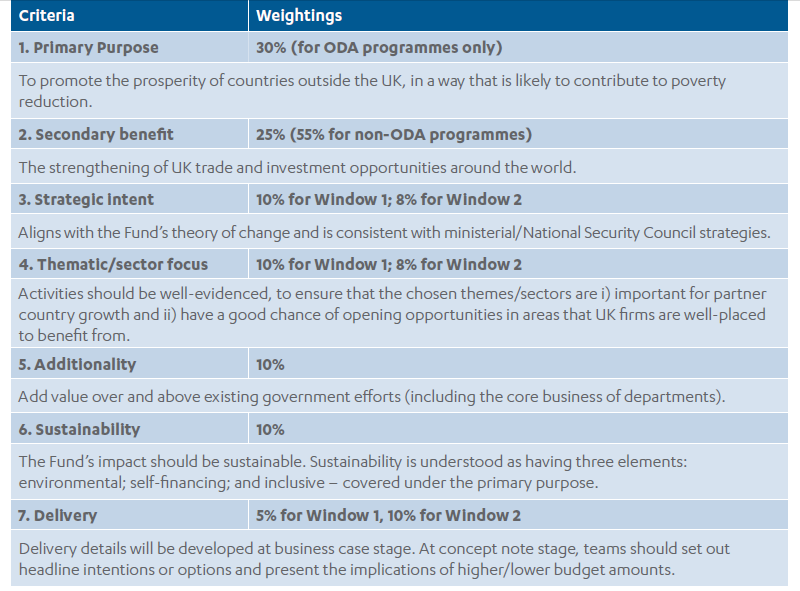

Departments initiate bids by submitting concept notes of five to six pages, outlining in broad terms the proposed area of activity and how the programme will deliver on the primary purpose and secondary benefits. Those submitted to date offer few details about programme designs or delivery arrangements. The PFMO assesses the concept notes against seven criteria (see Table 3). The PFMO assessments for all concept notes are passed through the Portfolio Board to the Ministerial Board with a recommendation on which concept notes the PFMO and the Portfolio Board have assessed to be of sufficient quality to proceed to business case. Ministers approve concept notes as ready to proceed to full business case.32

Following approval of a concept note, the bidding department prepares a full business case, following the Treasury’s recommended ‘five case’ model.33 These are much more substantial documents, setting out in detail the programme design and the projected benefits. The value of the business cases must be confirmed by the Portfolio Board and then approved by the recipient department, according to its own rules. ‘Big ticket’ or novel programmes (£50 million or more) and any programme greater than a departmental spending limit also require parallel approval by the Treasury. ODA spending will need to be compliant with the legal basis for the fund (the International Development Act) and with OECD DAC rules on UK spending at this approval stage.

Only once business cases are approved will the final budget for each programme be determined. The Prosperity Fund intends to ‘over-programme’ by approving concept notes whose total provisional value exceeds the available budget by a substantial margin, in anticipation that some programmes may be scaled back at business case stage.

Table 3: Scoring of Prosperity Fund bids34

Proposals (concept notes) are scored by the PFMO against seven criteria, on a seven-point scale. The criteria are weighted as indicated below, and also given a red/amber/green rating. Bids are considered to be of good quality or have programming potential and are recommended for approval if they received a combined score of 35 or more, from a possible 49. The scoring was subject to a moderation process by an externally engaged assessor to ensure consistency of scores. There was also feedback from a development practitioner, DIT and the FCO Economics Unit. In some instances, unsuccessful concept notes were revised following technical advice from the PFMO and resubmitted in the next funding round.

For the first round of bids (Window 1), the proposed delivery arrangements were given a weighting of only 5%. For the second round, this was revised up to 10%, to signal the need for more attention to this aspect in the concept notes, although mathematically this makes only a marginal difference to project scoring.

Source: Operating Framework and assessments. Note that with these revisions under Window 2 the total comes to 101%, which is used in the actual score sheets. We note a slight inconsistency with the scoring guidance in the Operating Framework in this regard.

Progress to date

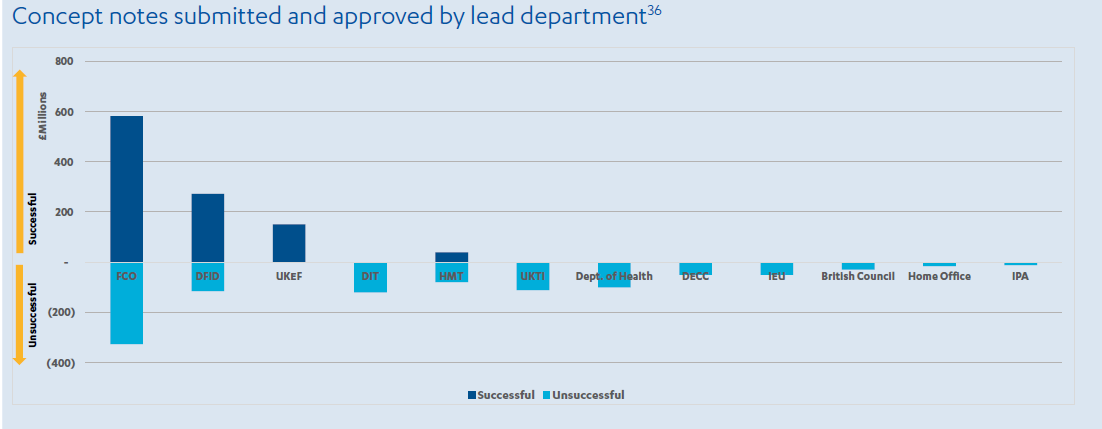

By the end of 2016, the Prosperity Fund had completed two of three planned rounds of competitive bidding (Windows 1 and 2). Of 47 concept notes submitted (including some repeat submissions), 20 were assessed by the PFMO as meeting the technical assessment threshold, and all but one of those were endorsed by the Ministerial Board. They have a combined budget of up to £1.1 billion (see Table 4).

Table 4: Outcomes of the first two bidding rounds

| Bidding round | Concept notes submitted | Concept notes scoring 35 or more | Concept notes endorsed by Portfolio Board | Total indicative budget of concept notes in development (£ million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Window 1 | 25 | 12 | 13# | 659.2# |

| Window 2 | 22 | 8 | 7 | 449.5 |

| Total | 47 | 20 | 20 | 1,108.7 |

# This includes the concept note for the Monitoring, Reporting, Evaluation and Learning contract which was not scored (see section 3.38-42). Total indicative budget would be £594.2 million without this concept note. Source: PFMO documentation

Table 5: Prosperity Fund programmes announced to date

| Programme | Amount (up to £ million) | Lead department | Timing |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Investment and Infrastructure Fund – India | 120 | DFID | Announced with Prime Minister’s November 2016 visit to India |

| Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank | 39 | HMT | Announced with the eighth UK-China Economic and Financial Dialogue in November 2016 |

| Multisector – Colombia | 25 | FCO | Announced with President of Colombia’s November 2016 state visit to the UK |

Box 4: Results of the bidding process so far

In the first two bidding ‘windows’, the FCO has been the most successful department. It is the departmental lead on 13 approved concept notes with a total budget of up to £582.2 million (subject to business case approval). UK Export Finance has a single approved concept note of up to £150 million and DFID is departmental lead on four with total budgets of up to £272.5 million. The Treasury has one concept note totalling up to £39 million, although this is a contribution to an existing fund, rather than a programme delivered by Treasury.

The leading sectors addressed by approved concept notes are infrastructure / infrastructure finance (up to £334 million), trade (up to £150 million) and digital access (up to £82.5 million). Following guidance from the Ministerial Board, many of the concept notes are for multi-sectoral programmes (up to £266 million). The emerging allocation across countries is shown in Annex 2. Most approved concept notes cover multiple countries. So far, India has two single-country bids and China, Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia and Colombia each have one single-country bid. India is the largest prospective country recipient, with double the value of approved concept notes as compared to China, the next largest.

IEU: International Energy Unit, IPA: Infrastructure & Projects Authority, UKEF: UK Export Finance, UKTI (now DIT) UK Trade & Investment, (now Department for International Trade). Concept notes were submitted before the July 2016 restructuring of departments. During the process ICT was renamed Digital access and Future Cities bids were incorporated into multi-sectoral bids. Bids that were resubmitted in the second window are counted only once. Some early concept notes were less clear about their sectors.

Source: Derived from PFMO documentation

Findings and emerging challenges

In this section, we consider whether the emerging systems and procedures of the Prosperity Fund are adequate to ensure effective programming and good value for money. Many of these processes are still under design, or are being continuously developed by the PFMO. It is therefore not our intention to reach final conclusions at this stage. However, we draw attention to a number of emerging issues and challenges facing the Fund that should be addressed in the coming months, before major funding decisions are taken. We also explore the question of whether the Fund has drawn on lessons from other cross-government ODA funds and instruments.

Governance

Improvements in the governance structure

At its establishment, the Prosperity Fund was directed by the Treasury to make use of some existing governance structures used by the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), including a cross- Whitehall officials-level board and a series of regional boards. However, according to key stakeholders, this encouraged competition for resources across countries and regions, rather than collaboration in building a coherent portfolio of complementary interventions selected to achieve priority objectives. A March 2016 review of the Prosperity Fund by the IPA concluded that this governance model was ‘based on inherited structures rather than designed to meet the requirement going forwards’.35

There does not appear to have been any structured assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the CSSF model or its suitability for the Prosperity Fund before the Treasury recommended this structure in its settlement letter.36 ICAI has not reviewed the CSSF’s central management arrangements but some of the challenges discussed in this report – such as developing a strategic portfolio and measuring portfolio impact – appear to be common between the two funds.37

The Prosperity Fund has since adapted its structure. Responding to the IPA’s recommendations, it created the Portfolio Board, with the cross-government Directors’ Group limited to an advisory role (see Annex 1). While the main delivery departments for the Prosperity Fund are represented on the Portfolio Board, it has now been made more explicit that they have a joint responsibility to maximise the quality of the portfolio as a whole.

Clarity of roles remains a concern

While this was a step in the right direction, we remain concerned at a lack of role clarity in the Prosperity Fund’s governance. Early experience from both the CSSF and the International Climate Fund (ICF) suggests that competition between departments for resources can undermine strategic decision-making, and needs to be managed carefully.38 Although there is a neutral chair from the Cabinet Office, there is a risk that departmental representatives on the Portfolio Board may be tempted to promote their own department’s interests. We heard concerns from some key stakeholders that, of the 12 departments that submitted bids as lead department, those represented on the Portfolio Board39 have been the most successful.

“The Portfolio Board is still very much in its formative stages but needs to become a focussed forum for the discussion of strategic Fund issues and to support the [Deputy Senior Responsible Owner], whose role is better reflected by the title Portfolio Director… It is crucial that time together in the Portfolio Board is used to develop a better understanding of the Fund’s strategic intent, on a true cross Whitehall basis.”

Cross Whitehall Prosperity Fund Gateway Report V1.0, September 2016

There has been lack of role clarity around the PFMO. While it is formally an inter-departmental body managed from Cabinet Office, it sits within the FCO and is staffed by a majority of FCO officials. Given that the FCO is short on staff with programming experience, the PFMO has played a key role in supporting the preparation of FCO bids to the Prosperity Fund. This was not compatible with its role as technical assessor of bids, and also drew resources away from the core functions of the PFMO. The IPA has made a number of recommendations that the PFMO’s roles and responsibilities should be clarified to focus on portfolio business. These have been accepted.

The PFMO and the FCO are aware of the risks around conflict of interest and are working to further clarify their roles and responsibilities.

Portfolio development

Risks of fragmentation

The Operating Framework states that the Prosperity Fund is ‘adopting a portfolio approach’, funding a range of programmes with a shared focus on strategic countries and sectors. It also states that a competitive bidding process will be used to identify the most promising programmes and drive up standards.40

The Prosperity Fund’s approach of using competitive bids to develop a portfolio is similar to that of challenge funds. These funds are commonly used to identify demand-led solutions to development challenges and to promote innovation and value for money, often with a focus on private sector development. A key difference between challenge funds and the Prosperity Fund is that the former are typically targeted directly at private sector companies or NGOs, whereas the Prosperity Fund’s competition takes place within government before funding is made available externally. Nevertheless, learning from challenge funds is relevant to the Prosperity Fund and is summarised in Box 5.

Challenge funds need to be focussed on a specific development challenge, so that the bids are comparable.41 In contrast to this, the Prosperity Fund is trying to build a portfolio across a range of several sectors and countries. There also needs to be a sufficient ratio of applications to final approved programmes, to ensure genuine competition in challenge funds. ODI, for example, suggests that average ratios are one or two awards for every 50 applications.42 The Prosperity Fund has received only 47 applications (concept notes) in total. With 20 of those cleared to progress to the final business case stage, its award ratio looks set to be significantly lower than the average for challenge funds. While the Prosperity Fund informed us that it had learned from similar funds and earlier iterations of the Prosperity Fund, we found no clear evidence of learning from wider challenge fund research and literature, including that done by DFID.43

Box 5: Learning from challenge funds relevant to the Prosperity Fund44

- Challenge funds should ‘not be used as a short-cut to good development practice and require strategic frameworks, plausible results chains and theories of change’.

- Challenge funds need to promote wide participation to generate sufficient numbers of quality submissions and to have clear eligibility and selection criteria.

- Poorly defined funds can cause damage and distortion to local markets and economies or the environment.

- Challenge funds are most effective where viable solutions are not available due to perceived risk to the private sector.

- Monitoring and evaluation are key to learning what works and informing decisions on scale-up and replication.

Learning from other cross-government instruments, such as the Conflict Pool and the ICF, suggests that competitive bidding is less suited to allocating funding in a strategic manner across multiple priorities. However rigorous the scrutiny of bids, the allocation of resources across sectors and countries will be a product of which bids are received. This makes it difficult to match resources to needs and opportunities, avoid gaps and overlaps, or promote complementary interventions. This is reflected in the Prosperity Fund’s theory of change, which states: ‘As we gain more information on likely bidding strands we can adapt the theory of change to reflect more clearly the areas where the

fund will be working’.45

Box 6: ICAI findings on competitive bidding in the Conflict Pool

‘When the Conflict Pool acts as a responsive, grant-making fund, the extent of its engagement in any given area is determined by the number and quality of proposals that it receives. While it can specify its objectives, it may not receive credible proposals on a sufficient scale to achieve them. Instead, the model tends to produce a proliferation of small-scale activities that, however worthwhile, are unlikely to have strategic impact… If it is to become more strategic in orientation, the Conflict Pool needs the ability to concentrate its resources behind key objectives through active procurement of partners for larger interventions.’

Evaluation of the Inter-Departmental Conflict Pool, ICAI, July 2012, paras. 2.35-36

Missed opportunities for delivering strategic impact

So far, the Prosperity Fund has articulated its overall objectives only in very broad terms. For the first window, it did not set out an indicative allocation of funds across sectors or countries, to guide the approvals process.46 Many of the concept notes contained only an indicative list of sectors and countries to focus on, and most covered multiple countries and sectors. By the time the second Window decision-making process was in train, a Portfolio Balance Guide was available, providing guidance on the amount of funding to go to different sectors and countries. The Fund’s eventual de facto geographical and sectoral priorities will be known only once final business cases are approved.

Learning from the ICF suggests that the development of portfolio-wide results indicators is an important part of building a strategic portfolio. After struggling with similar challenges, the ICF developed a set of 17 such indicators. The process of developing them was important to developing a shared understanding of the ICF’s key results areas and the importance of impact data. Each ICF project was then required to report against at least one of these indicators every six months. That meant that all projects were aligned with the strategic objectives of the ICF and generated data on its global impact. It took nearly two years for the ICF to achieve portfolio-level results indicators, however, there is greater urgency for the Prosperity Fund, as all its resources will soon be allocated.

We agree with the finding of the IPA that the Prosperity Fund should continue to work on the articulation of its strategy and objectives, and consider taking a more proactive role to developing its flagship programmes in high-priority areas.

Primary purpose and secondary benefits

Challenges in combining primary purpose and secondary benefits

One of the challenges facing the Prosperity Fund is the need to reconcile its primary purpose (poverty reduction) with the need to strengthen secondary opportunities for UK firms. In the scoring criteria for concept notes, these objectives are weighted at 30% and 25% of the total score, respectively.

How these goals are articulated and balanced varies considerably across concept notes. All the concept notes relate to proposed work on widely accepted areas of development assistance, such as trade liberalisation, the business environment, anti-corruption, financial services or infrastructure. They all assert that the proposed programme has the potential to promote economic growth. Some go a step further, suggesting that the resulting growth will be inclusive in nature, thereby contributing to poverty reduction. The Fund’s understanding of sustainability is based on three dimensions – green (environmental), self-financing and inclusive. This is supposed to run through programme design. We found this to be weakly articulated in concept notes.

While recognising their preliminary nature, the level of analysis in the concept notes does not give full confidence in the likelihood of successful achievement of results. In the concept notes, the case for poverty reduction is backed up by brief references to development literature suggesting that the proposed outcomes (for example, increased openness to trade or a better regulated business environment) are associated with higher growth. Nonetheless, we noted instances where the texts cited were more equivocal than suggested in the concept notes. Analysis of the country context is usually very brief. A few concept notes refer to DFID’s diagnostic work.47 In most instances, the proposed activities are not described in sufficient detail to allow for meaningful assessment of the likelihood of success.

Most concept notes contain no mention of, or only a passing reference to, promoting gender equality, although this is a requirement of the International Development Act. Contrary to the guidance on scoring concept notes which calls attention to the obligation to consider gender equality,48 we noted only one instance where the concept note summary scoring drew attention to gender. The PFMO has indicated that they have requested bidders to pay more attention to gender at business case stage.

Box 7: Experience of other donors with similar instruments

A number of other bilateral donors have developed aid instruments that promote bilateral economic ties with developing countries, for mutual benefit. For example, the Danish development agency Danida has a Business Explorer programme (approximately £900,000 in 2016), that provides funding to Danish companies operating in developing countries, to promote growth in both developing countries and Denmark. A Dutch programme called Development Related Infrastructure Vehicle (£125 million in 2015-16) offers subsidies, loans and guarantees to support the development of infrastructure in eligible countries.49 The aid is untied but the announcement of opportunities is in Dutch, so is likely to be challenging for non- Dutch companies. The UK Export Finance Prosperity Fund programme has been informed by discussions with this Dutch programme.

The limited evaluation evidence available on such programmes suggests that they find it difficult both to deliver and to demonstrate positive impact on growth and employment creation.50 In some instances, programmes have been terminated or redesigned because they were found to be incompatible with EU state aid rules, which prohibit government support to companies that confers a trading advantage over competitors.51

Most concept notes are more specific regarding their proposed secondary benefit to UK firms. Some make an effort to quantify the expected benefits, such as the anticipated increase in bilateral trade or exports. However, the evidence and analysis behind these estimates is not always explained.

The benefits to UK firms suggested in concept notes can come about in two ways. One is direct involvement in the delivery of the assistance. As the aid is untied, this form of benefit often depends on UK firms being able to win contracts against international competition. The other is as a consequence of the primary purpose. For example, concept notes argue that, if the proposed programmes succeed in liberalising trade, improving the business environment, reducing corruption or strengthening intellectual property rights, benefits will accrue to UK firms in the form of trading advantages. Both types of benefit rest on significant assumptions that are not explored in any detail in the concept notes, even though the guidance note on scoring states that any risks to the achievement of secondary benefits must be noted.

We note that, while the Aid Strategy talked about creating opportunities ‘for international business, including UK companies’ in line with the commitment to untied aid,52 the secondary benefit scoring criterion for concept notes refers solely to ‘strengthening UK trade and investment opportunities around the world’.

From the concept notes, it appears that departments are finding it difficult to develop programmes that combine the primary purpose and secondary benefits in a convincing way. To be successful in its aims, the Prosperity Fund will need to continue to provide training and advice to stakeholders to help them identify areas where both primary purpose and secondary benefits can be pursued without making unrealistic assumptions.

The Operating Framework states that ‘a project or programme proposal cannot progress without demonstrating that this primary purpose is met’53 but this was not clear from the scoring process. Concept notes were rated out of seven and given a green/amber/red rating against each assessment criterion. 42% of concept notes were endorsed to proceed to full business case development. Of these, only 75% were rated ‘green’ for primary purpose. Several concept notes that were rated amber, scoring between three to five out of seven, were invited to proceed to business case. There was no explicit minimum score for primary purpose. It would have been more appropriate to include a yes/no condition on ODA eligibility and a separate rating on overall contribution to poverty reduction at this stage.

Box 8: A contribution to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank

One of the three approved concept notes that has been publicly announced (on a provisional basis) is a contribution of up to £39 million to the newly established Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank’s (AIIB) Special Fund. The AIIB is a new multilateral development bank launched by China, which the UK government has pledged to support. The Special Fund will provide grants to the poorest Asian countries for technical assistance for project preparation, to help them access infrastructure finance from the AIIB.

Primary purpose: The concept note refers to existing data and analysis from the AIIB on the infrastructure gap in Asia, especially in transport and energy, and the likely contribution of investment projects to promoting growth and poverty reduction. The primary purpose case is strong, although the calculations used to quantify the impact, annexed to the concept note, were incomplete, suggesting that they were not scrutinised.

Secondary benefit: The anticipated secondary benefits include UK companies winning contracts from the Special Fund to provide technical assistance for project preparation, and then going on to win followup contracts for project delivery. The concept note states that the UK has world-leading expertise in the preparation of infrastructure projects. In 2016, the UK was the tenth largest supplier of consultancy services to the World Bank, with $70 million in contracts. Over the last decade, the UK was the second largest supplier of consultancy services to the World Bank with $1.7 billion of contracts.54 The concept note found that UK firms have a poor record at winning major delivery contracts from other development banks, with the UK ranking just 28th in the world in terms of World Bank contracts won (China ranks first and India second). It states that the AIIB’s focus on green energy projects and public-private partnerships will advantage UK firms, and that the government will provide diplomatic support to firms bidding for AIIB business.

In our view, some of the current concept notes do not contain enough detail on their proposed activities and impacts to provide a sufficient assurance as to a likelihood of poverty reduction, for the purposes of the International Development Act. We would hope to see this much better articulated in business cases, and that the Prosperity Fund includes a check on ODA eligibility (including due consideration of gender equality) before approving business cases.

Delivery speed and capacity

Progress in establishing the Prosperity Fund

During 2016-17, the Prosperity Fund operated on a smaller scale, using the processes of its predecessor FCO programme, to allow time for the necessary systems and processes for operating at scale to be put in place. Our observation is that, despite the best efforts of the small but highly committed PFMO team, it was not able to achieve that in the time available. Rather, it has been forced to design each stage of the process as it came to it. This speed of working leads to some substantial delivery risks.

The PFMO has been expanding its staff and hiring external contractors to fill skills gaps in areas such as procurement and programme design. Even so, the speed at which the Fund plans to move from broad concept notes to approved business cases (less than six months) is unprecedented. For comparison, DFID, even with its long experience of designing and delivering aid programmes, frequently takes more than 12 months to develop a business case for a major new programme and secure ministerial approval.

Risk of speed and scope out-pacing capacity in some areas

Delivery arrangements for Prosperity Fund programmes will be tailor-made for each programme. Larger programmes may involve several components, each with different delivery channels. The approved concept notes include a diversity of delivery channels, including:

- contributions to multilateral organisations and funds

- activities delivered directly by UK government agencies

- technical assistance and investment projects procured from the private sector

- challenge funds, managed by external contractors, which may be open to bids from companies,NGOs and government agencies in the UK or developing countries.

Responsibility for delivery belongs to the spending department holding the budget for that programme or programme element. Several of them, including FCO and DIT, are recruiting in anticipation of the delivery load. Many programmes will include inception periods to give more time to refine designs and produce implementation plans. Nonetheless, the pace of the planned scaling up of ODA spending by certain departments is remarkable.

The FCO is the lead department on 56% of the approved concept notes by value, with a total budget of up to £582.2 million over four years. By way of comparison, its most recent published annual ODA expenditure is £391 million and its total annual budget just over £1 billion.55 Key stakeholders and independent reviews suggest that this large increase will require fundamental changes to the department’s financial management model.56 The Department for International Trade and its ministerial department, UK Export Finance, may also be beneficiaries of significant funding. Neither has any previous experience of managing ODA.57 Key stakeholders in several departments informed us that they were concerned at the scale of the challenge they faced in delivering both primary purpose and secondary benefits in Prosperity Fund programmes.

“The FCO financial systems were not designed for managing programmes and are a constraint on effective delivery on the ground. The FCO’s financial management system, PRISM, is a receipting system mainly designed for procuring items for the FCO’s own use. It has been adapted to include some programme management and project accounting capacity… [but] does not facilitate effective real-time tracking of expenditure.”

FCO and British Council Aid Responses to the Arab Spring, ICAI, June 2013, p. 11.

Some Prosperity Fund programmes will be delivered by UK diplomatic posts. In some countries, such as India, China or Mexico there is already some delivery capacity in place, in others, such as Colombia (which has already received an indicative allocation of up to £25 million), that capacity will need to be created.

Given their capacity constraints, the departments will be particularly reliant on contractors to support the preparation of business cases. In some instances, they may use ‘design and build’ contracts, where suppliers are paid both to design programmes and to implement them. While this can be an appropriate way to proceed for flexible programming, there are significant value for money risks if the departments do not have sufficient capacity to select, oversee and manage their contractors effectively. The PFMO is aware of these risks and seeking to ameliorate them through changing the programme staff profile and providing training.

The PFMO and the FCO informed us that they are seeking support from DFID on the detailed design and delivery of Prosperity Fund programmes. It is likely that there will be cross-department steering committees, whether at programme level, by country or by sector, on which DFID will be represented. DFID may also be called upon to provide support on procurement, results management and ODA eligibility, however, it is not clear at this stage what level of resource DFID will be willing or able to devote to supporting the Prosperity Fund, either centrally or in-country.

Procurement challenges

A range of procurement approaches is emerging

Prosperity Fund procurement will follow EU rules. The procurement approach is the responsibility of the individual bidding departments, and will be assessed according to best fit for the specific project. Our interviews and documentation suggest that a range of approaches is emerging. These include existing and planned DFID procurement frameworks, new Prosperity Fund frameworks, some direct procurement (with or without competition), memoranda of understanding with multilateral partners and challenge funds for competitive grant-making.

Many of the concept notes assume that UK firms will be procured to deliver the activities – indeed, this is sometimes cited as part of the secondary benefit. The Prosperity Fund, however, is also required to comply with UK commitments against the tying of aid and it will therefore need to ensure open international competition. It may also wish to consider whether engaging local firms and NGOs in partner countries would be helpful in promoting prosperity.

At a recent engagement event, the PFMO informed potential suppliers that much of the procurement under the Prosperity Fund would likely be awarded to large firms with global reach. Smaller firms would be more likely to be involved as subcontractors. Economies of scale in procurement can be generated through having few large suppliers. However, long supply chains can give rise to other value for money concerns, if they result in several layers of management overheads. The PFMO is aware of the risk of long supply chains and will focus on impact and value for money.

Box 9: Views from the private sector and civil society

We consulted ten suppliers that are targeting Prosperity Fund for contracts via a survey. Seven of these are among DFID’s 11 strategic providers.58 The other three are major providers of international development consultancy. We also spoke with British Expertise (a private sector organisation for British companies offering professional services internationally which has over 200 corporate consultant member companie)59 and with an existing multi-donor fund manager with significant private sector development experience. Key supplier feedback is summarised here:

Suppliers saw the Prosperity Fund as a major opportunity for them to delivery services in middle-income countries not prioritised by DFID.

They supported the vision of the Prosperity Fund as important for long-term development and alleviation of poverty, and highlighted areas of competitive strength where UK firms could add significant value.

They also raised important concerns.

Half of respondents highlighted concerns about the fund’s management as a major risk to its success. They commented that the Fund’s management appeared disorganised, especially being 18 months in, and raised concerns that this could result in a rush to spend to meet budget targets.

Over half of the suppliers expressed concern about an apparent lack of an overarching strategy and the way in which concept notes were prepared.

They described the process as opaque and exclusive and raised concerns that the Prosperity Fund appears to be trying to build a portfolio based on an insufficient number of quality ideas from participating departments and country diplomatic posts.

The ability for the Prosperity Fund to work across programmes, thematic areas, centrally and in-county postings was also raised as a key concern.

Three respondents queried whether the primary purpose was a pretext for delivering benefits to UK companies and noted that the Fund had become more explicit about the role of UK business following the EU referendum.

Five respondents commented that earlier engagement by the PFMO with suppliers was poor but that information and engagement had improved towards the end of 2016. Three commented that communication around procurement strategy and the actual projects remains insufficient which has limited the amount of market preparation possible.

We also spoke to six UK and international development NGOs, including the UK membership body, BOND, and UK CSO policy and advocacy network for aid effectiveness, UKAN. They expressed concern that formal communication with civil society came later in the process, several months after the Prosperity Fund was announced, and only after request by civil society. They noted that informal communication and follow-up has not in their view been substantive and that a lack of transparency makes the Fund difficult to access. Their preference would be to build a longer-term productive partnership. They noted that, if used only as subcontractors to large firms, they would be restricted in their ability to bring their own perspective and operating models to the programmes. They may also be constrained from working with some companies due to their own ethical standards. NGOs have raised similar concerns with regard to the CSSF.60

Our analysis of the concept notes to date indicates that there has been a wide variety of approaches to consulting UK business. Of the 40 concept notes we reviewed:

- four referred to formally contracted scoping studies

- 29 referred to some kind of interaction with UK firms, on an informal or unspecified basis and

- four referred to major UK firms (potential suppliers) contributing to the design.

Transparency will be critical to avoid potential conflicts of interest

From the findings summarised in the previous paragraph, we note some conflict of interest concerns regarding the involvement of major firms. At least four large firms have advised on the development of the Prosperity Fund or individual concept notes. While these inputs may have been useful, and the Prosperity Fund states that it has followed the procurement rules, the process has not been transparent. This risks creating the perception that firms have been shaping the operation of the Fund or the design of particular projects for their own benefit, without competition or transparency about opportunities to engage (see Box 9 above).

Monitoring, evaluation and learning

Ambitious plans in place for monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning

Demonstrating the impact of a diverse portfolio of Prosperity Fund programmes on both poverty reduction and UK business opportunities will be a complex challenge, both technically and managerially. The Prosperity Fund’s budget allocates 5% (£65 million) to monitoring, evaluation and learning. The Fund has decided to procure the bulk of its monitoring and evaluation work (£48.2 million) from external suppliers. The options of delivering it in-house or leaving it to individual programmes to

arrange were considered in the business case but discounted, due to the desire for independence and coherence in approach across the Fund and the limited monitoring and evaluation capacity.

The business case states that the model draws on learning from the ICF and DFID’s Girls’ Education Challenge fund but does not specify what that learning is. The PFMO also states that it consulted extensively with DFID, however, the business case notes that ‘DFID programmes are usually defined more clearly at this stage and it is possible to be more specific about which evaluation methodologies will be deployed in order to best measure impact. Likewise, a ‘normal’ DFID programme will be clearer about the indicators that will be measured in line with the programme’s theory of change and logical framework [before commissioning evaluation services].’61 This will make it challenging for prospective bidders to define their approaches and for the PFMO to appraise bids.

The Prosperity Fund’s monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning contract will be contracted in three parts:

• Support to programmes on monitoring and reporting: up to £13 million.

• Evaluation and learning at portfolio level: up to £16 million plus three additional contracts totalling up to £4.2 million.

• Programme level evaluations: up to £15 million.

The first part will be procured by the PFMO itself (its only direct procurement responsibility) through a competitive process. The latter two will be procured through DFID’s Global Evaluation Framework Agreement.62 The tenders were announced in October 2016 and were due to be completed by January 2017, so that the suppliers can be in place to support the start of the new programmes launching in April. This is an extremely short period for such a large and complex procurement. Given that it is likely to involve a complex delivery structure, the PFMO will also need to give adequate resources to managing the contract.

Potential challenges ahead in integrating with programme management

We are concerned about contracting out these services in their entirety to external suppliers at such a pace and scale. As monitoring and evaluation capacity in the PFMO and most lead departments is weak, this risks poor integration with management and learning at portfolio and programme levels.

Transparency

More work is required to meet government undertakings on transparency

The UK government has made a public commitment to promoting aid transparency. The recent Bilateral Development Review states that the UK will ‘push for a global transparency revolution, opening up budgets at every level so that people around the world can see how their money is being spent and hold the powerful to account’.63 It has committed that all UK ODA-spending departments will be ranked as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ in the Aid Transparency Index within the next five years, that is by 2020.64

This timetable leaves the Prosperity Fund and its delivery partners scope to operate with minimal transparency. At present, there is very little information on the Fund in the public domain. None of its strategy documents have been published, and there has been limited information published as to how it will work, beyond the initial announcement of its establishment.65 The transparency challenge was recently referenced in relation to the CSSF at the Joint Committee hearing on the National Security Strategy.66

The Prosperity Fund has been raising awareness among government departments, with various stakeholder events and engagement led by the procurement team, however, key stakeholders from UK firms, NGOs and even some government departments expressed their concerns about the difficulty of obtaining information on the Prosperity Fund and its operations.

The IPA review in September 2016 found that the focus of communications has been largely internal with limited formal external communication. It recommended that as the Fund moves towards the implementation phase, the balance of activity should shift to ensure greater focus on external communication. We agree with this view.

Conclusions and recommendations

Recommendation 1:

The government should consider adjusting the planned rate of expenditure of the Prosperity Fund as its delivery capacity develops, if necessary by spending its resources over a longer period. The Fund should consider holding back more resources for allocation in later years, and ensure it has adequate flexibility to reallocate funds between programmes to reflect their performance.

The Prosperity Fund is a complex and ambitious fund, with systems and processes which are still being developed and refined. The planned scale and pace of its aid spending poses a number of risks. Chief among them is the risk that those lead government departments with little experience of large aid programmes may struggle to design and deliver programmes capable of achieving intended results. It is therefore particularly important that the Fund has the flexibility to adjust the allocation of resources if needed, as capacity develops and evidence of what is working emerges.67

Departments are being asked to move from broad concepts to full programme designs within a very short time, and then meet large spending targets. This has been recognised, and the Fund recently discussed adjusting the spending target for 2017-18, although this could increase the risk that the Fund will then be required to spend an excessive portion of its budget in its later years. This may require extending the scheduled 2021 end date for the current £1.3 billion budget.

We are also concerned about plans to commit the entire budget for funding to programmes by mid-2017 (bar £40 million). Although there is a commitment to active portfolio management, so that projects can be reduced or closed, there will be limited opportunity for resource allocation to be informed by experience. We suggest that the Prosperity Fund holds back some resources for allocation in later years and ensures that it has the flexibility to reallocate funds away from under performing programmes. The current approach of managing down the portfolio on a business case-by-case basis will not deliver this flexibility and space for learning.

Recommendation 2:

The Prosperity Fund should refine its strategic objectives and develop a set of portfoliolevel results indicators, to which each programme should align. It should ensure that its monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning services are integrated with management and learning processes at both portfolio and programme levels.

The objectives and strategy of the Prosperity Fund have been set out in very broad terms: increased capacity for trade and economic growth in partner countries, and higher rates of sustainable growth. The specific allocation of funds across countries, sectors and themes will emerge from the results of the bidding process, and from the mix of activities that are subsequently adopted within the large multi-country and multi-sector programmes. There is a risk that the portfolio that emerges will be fragmented. This would make it difficult for the Prosperity Fund to achieve and demonstrate strategic impact that is greater than the sum of individual programme parts, commensurate with a £1.3 billion initiative.

The Fund is procuring the bulk of its monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning work from external suppliers, including the creation of results indicators. While accepting the value of independent evaluation, we consider it a high-risk choice to contract out so much of the monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning. In such a novel and high-risk instrument, learning needs to be fully integrated into the Fund.

Recommendation 3:

For Prosperity Fund programmes spending UK aid, the process for ensuring ODA eligibility should be explicit and challenging. The Fund should ensure that business cases include a plausible strategy for delivering primary purpose and secondary benefits, based on sufficient evidence and analysis, and give adequate consideration to gender equality, in compliance with the International Development Act.

We are not convinced that the current set of concept notes assure the likelihood of programmes satisfying the requirements of the international ODA definition and, where relevant, the International Development Act. It is therefore important that the assessment of ODA eligibility is tested to a challenging threshold at business case stage. When scoring future concept notes and at the business case stage, we would suggest that the technical scrutiny involve both a clear yes/no assessment of ODA eligibility and an increase in the weighting of the primary purpose case to ensure the Fund is compliant with the relevant aid rules.

Designing programmes that can credibly deliver both primary purpose and secondary benefits is a challenge – there is little experience or evidence on how to do this, either in the UK or internationally. From our analysis of concept notes and feedback from key stakeholders, departments are struggling to combine these two objectives in a plausible way. A clear strategy is needed to help in the design of these programmes.

Recommendation 4:

The Prosperity Fund should formalise and be more open about its engagement with UK and international firms. It should manage its supplier pool with a view to avoiding conflicts of interest, securing value for money and achieving both primary purpose and secondary benefits.

We found a lack of clarity in communication and an opaque approach to communication and engagement with potential suppliers. Engagement appears to have been selective and without consideration of the potential implications for the competitiveness of procurement processes. This does not inspire confidence in the Fund’s approach to securing value for money through procurement and to achieving primary purpose and secondary benefit.

Recommendation 5:

The Prosperity Fund should establish its procedures on the basis of full transparency in line with the government’s public stance on this issue.

The UK government has made a public commitment to ensuring aid transparency, however, there is currently very limited information on the Prosperity Fund in the public domain (although we understand that a communications plan will be implemented early in 2017). Key stakeholders, including some government departments, expressed concerns about the difficulty of obtaining information on the Prosperity Fund and its operations, leading to a lack of clarity about its work and purpose.