Transparency in UK aid

Acronyms

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| AMP | Aid Management Platform |

| ATI | Aid Transparency Index |

| BDD | Better Delivery Department |

| BEIS | Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus |

| CS | Chevening Scholarships |

| CSSF | Conflict, Stability and Security Fund |

| DAC | Development Assistance Committee |

| DevTracker | Development Tracker |

| DFID | Department for International Development |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office |

| GBCC | Great Britain China Centre |

| IATI | International Aid Transparency Initiative |

| LGBTQ+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning |

| MP | Members of Parliament |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| PPF | Policy Portfolio Framework |

| PrOF | Programme Operating Framework |

| SID | Statistics on International Development |

| WFD | Westminster Foundation for Democracy |

| WP | Wilton Park |

Executive summary

In the early 2010s, the UK made a series of commitments to promote the transparency of UK aid, which formed part of a package of measures to improve the value for money of UK aid, strengthen public trust in a growing aid budget, and empower stakeholders in countries receiving aid. The former Department for International Development (DFID) was one of the first development agencies to begin publishing aid data and programme documents. From 2015, the UK government set transparency standards for all aid-spending departments.

The period since 2010 has also seen the emergence of a global drive for aid transparency, in recognition of its value in driving quality development cooperation and accountability. This led to the introduction in 2011 of a global standard for the reporting of aid information across the aid community, which was developed collaboratively by DFID and a number of other development agencies, through the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI).

In recent years, the UK aid programme has undergone significant changes, including the merger of DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), successive reductions in the UK aid budget and the publication of a new UK international development strategy. ICAI’s recent work has identified concerns that these changes resulted in a loss of transparency.

This review examines how the transparency practices of DFID, FCO and now FCDO have evolved since 2015. It assesses the relevance of their approaches to transparency, the effectiveness of their transparency efforts and their engagement with aid information users to learn about their needs.

Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and coherent approach to aid transparency?

Over the decade from 2010, DFID established itself as a global leader on aid transparency. At a corporate level this was achieved through publishing detailed statistics on its aid spending and development results, although country-level results were not detailed in its annual report after 2015. At the programme level transparency was promoted through developing and applying rules, procedures and systems for the routine publication of programme documents to a public portal (DevTracker). Any exclusions from publication had to be formally applied for, justified based on specific criteria linked to freedom of information legislation, scrutinised rigorously and approved by ministers.

While DFID applied a clear and coherent approach to aid transparency, it lacked a full understanding of the various users of aid data and did not tailor its aid publications to their diverse information needs. As a result, its published information was used primarily by expert stakeholders in the UK (such as parliamentary clerks and development non-governmental organisations (NGOs)), rather than the UK public or stakeholders in developing countries. A 2010 commitment to publish programme documents in local languages was also not fully pursued and was effectively discontinued from 2017.

The former FCO had a more ad hoc and discretionary approach to publishing programme documentation, which resulted in a wide range of publication practices for different parts of its aid portfolio. In most cases – including the substantial aid spending delivered through the British Council – it only published general descriptions of aid programmes and summary data, in a variety of formats, but not programme design documents or monitoring reports.

FCDO is still in the process of unifying the management system of its two predecessor departments. FCDO’s new Programme Operating Framework (PrOF), adopted in early 2021, contains a commitment to aid transparency and a set of detailed rules to guide practice. These rules apply the reporting practices of the predecessor departments to their respective aid portfolios, and place a much stronger emphasis on protecting sensitive information, despite the fact that over 90% of FCDO’s spending was previously managed by DFID. FCDO plans to adopt a new, unified programme and financial management system by November 2022, and the PrOF will be revised in preparation for this. Procedures for publication will then also be updated. In this context, it is a concern that in the revised UK National Action Plan for Open Government FCDO has merely committed to improve its score in the next Aid Transparency Index and to publish more complete and timely programme-level data. More ambitious commitments had been discussed within the department but were not adopted.

In 2020 and 2021 there were major reductions in the UK aid budget, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the government’s decision to reduce the aid spending target temporarily to 0.5% of UK gross national income. The format of information on these reductions that was eventually provided to Parliament and made available to Members of Parliament was unclear and made it difficult for parliamentarians and NGOs to scrutinise these decisions.

Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK achieved its aid transparency objectives?

The former DFID was judged by the globally recognised Aid Transparency Index as the most transparent major bilateral aid agency during the 2012-20 period. Between 2017 and 2020, only 2% of DFID business cases for programmes were formally withheld from publication, with over 90% of DFID business cases published on DevTracker.

Over the same period, FCO performed more modestly on aid transparency standards. In most instances, it published only summary programme information – for example in relation to its arm’s-length bodies, such as the British Council (£140 million in aid spending in 2020) – with little information on budgets and performance. Although FCO succeeded in improving its score in the Aid Transparency Index over time (from 21.3% in 2012 to 48.6% in 2020), it failed to achieve the commitment set out in the 2015 UK aid strategy to achieve a rating of at least ‘good’ (60%-80%) in the Index.

The merged department was assessed in the Aid Transparency Index for the first time in 2022. Its score (71.9%) was 13.5 percentage points below that of DFID in the 2020 Index (85.4%), making it the fourth-most transparent major bilateral aid agency. To a large extent, this was the result of combining two predecessor departments with differing levels of transparency. However, there were also indications that transparency has reduced across FCDO in a number of areas, namely publication of country aid priorities, country and divisional budgets (which were absent from this year’s FCDO annual report) and some aspects of results reporting. Furthermore, transparency around aid budget reductions in 2020 and 2021 was weak. The department does, however, remain a global leader in publishing reviews and evaluations of its programmes, and our analysis suggests it could quickly achieve a ‘very good’ Index rating with targeted improvements.

The UK has played an important role internationally in promoting aid transparency, including through its efforts to promote transparency among delivery partners and multilateral agencies, and through its instrumental role in establishing IATI and its reporting standard.

Our engagement with the users of UK aid information identified that being able to access this information has supported more effective scrutiny of the aid programme and helped to promote efficiency gains within FCDO. However, we were informed of only a few examples of programmes providing substantive support to partner countries to make effective use of published aid data, and only limited examples of UK aid data feeding into improved effectiveness at the country level have been documented to date. We noted from FCDO officials that the publishing of aid information poses modest demands on staff because transparency systems are now embedded and automated; this strengthens the cost-benefit argument for sustaining ambitious transparency standards.

Learning: To what extent has the UK sought and learnt from feedback from users of UK aid data, both in the UK and in partner countries?

The UK has undertaken some consultation with and research on potential users of UK aid information, but this has been limited and mainly with UK-based stakeholders (particularly expert users). This has meant that there have been modest changes based on user feedback on existing aid transparency tools such as DevTracker and Statistics on International Development, but there are still limitations on the accessibility and usability of this information that need to be addressed. The development of more effective aid transparency tools has been held back by constraints on the financial and human resources allocated to the task and, more recently, by the demands of the merger and new recruitment restrictions.

IATI, a core channel for the UK’s global work on aid transparency, has also undertaken only limited engagement with aid information users, especially in partner countries, although it has recently scaled up its work in this area and its latest strategic plan identifies promoting the use of aid information as a priority. The UK has been less active in IATI in recent years, and while it is supportive of IATI’s work on data use, it has stepped back from engagement in the data use working group.

Recommendations

Overall, we find that transparency has added value to the efforts of DFID, FCO and FCDO to promote accountability for and the effectiveness of their aid. Since the creation of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in September 2020, however, the UK’s commitment to aid transparency has come into question. It is therefore important that FCDO retains a clear commitment to aid transparency, to signal its continuing commitment to excellence in development cooperation.

Recommendation 1

FCDO should set out clear and ambitious standards for transparency to be applied to all aid portfolios (including arm’s-length bodies) through its unified systems, including default and timely publication of full programme documents, and a rigorous process for assessing, approving and reporting on exclusions.

Recommendation 2

FCDO should commit to achieving a standard of ‘very good’ in the Aid Transparency Index by 2024.

Recommendation 3

FCDO should resume publishing forward aid spending plans, cross-departmental development results and country aid priorities.

Recommendation 4

In FCDO priority countries, the department should work with other donors to support greater use of IATI data and other aid information sources, to strengthen aid effectiveness and accountability.

Introduction

1.1 Over the past decade, the UK has made clear commitments to ensuring the transparency of UK aid. The former Department for International Development (DFID) was one of the first development institutions around the world to commit to the routine publication of aid data, and from 2015 onwards the UK set down transparency objectives for all aid-spending departments. The UK was also active internationally in promoting transparency as part of good development practice.

1.2 Aid transparency is recognised in international policy documents and academic literature as an important principle: both taxpayers in donor countries and citizens or stakeholders in developing countries have a legitimate interest in knowing how international aid is used and what results it achieves. Aid transparency is also considered to be a means of improving the quality and effectiveness of aid, by making those involved in the delivery of aid more accountable. There are a range of actors potentially involved in that accountability chain, including parliaments and civil society organisations in donor countries. In recipient countries, these include governments (particularly ministries involved in preparing national budgets), parliaments, civil society organisations and citizens. However, the degree to which these actors actually make use of information on aid remains an open question.

1.3 In September 2020, DFID merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to create the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). Other important changes to UK aid followed, including successive reductions in the aid budget and the publication of a new international development strategy. In the context of these changes, ICAI’s reports following up on recommendations from its 2019-20 and 2020-21 reviews raised important questions around FCDO’s commitment to aid transparency. The new department is in the process of developing its policies and practices around the publication of aid data.

1.4 In these circumstances, a rapid review of the UK’s approach to aid transparency appeared timely. The review examines aid transparency practices by DFID and FCO over the period from 2015 until their merger, and by FCDO since its establishment in September 2020. It also assesses the role that DFID and FCDO have played in promoting aid transparency standards across the UK government and at the global level. In addition to checking compliance with the UK’s commitments on aid transparency, the review assesses whether the publication of aid data has helped improve the accountability and effectiveness of UK aid, and whether there has been effective engagement with aid information users to better respond to their needs.

1.5 The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, effectiveness and learning. It addresses the following questions and sub-questions as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and coherent approach to aid transparency? | • Does the UK have clear and defensible criteria to guide decisions on what aid information to publish? • How well does the type and format of aid data that is published reflect the needs and interests of intended users of the data? |

| 2. Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK achieved its aid transparency objectives? | • How well has the UK promoted cross-government standards and good practices on aid transparency? • How well is the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office performing in meeting its aid transparency commitments, compared to its predecessor departments and to other similar donors? • To what degree have transparency efforts helped improve the accountability and, subsequently, the effectiveness of UK aid? |

| 3. Learning: To what extent has the UK sought and learned from feedback from users of UK aid data, both in the UK and in partner countries? | |

Methodology

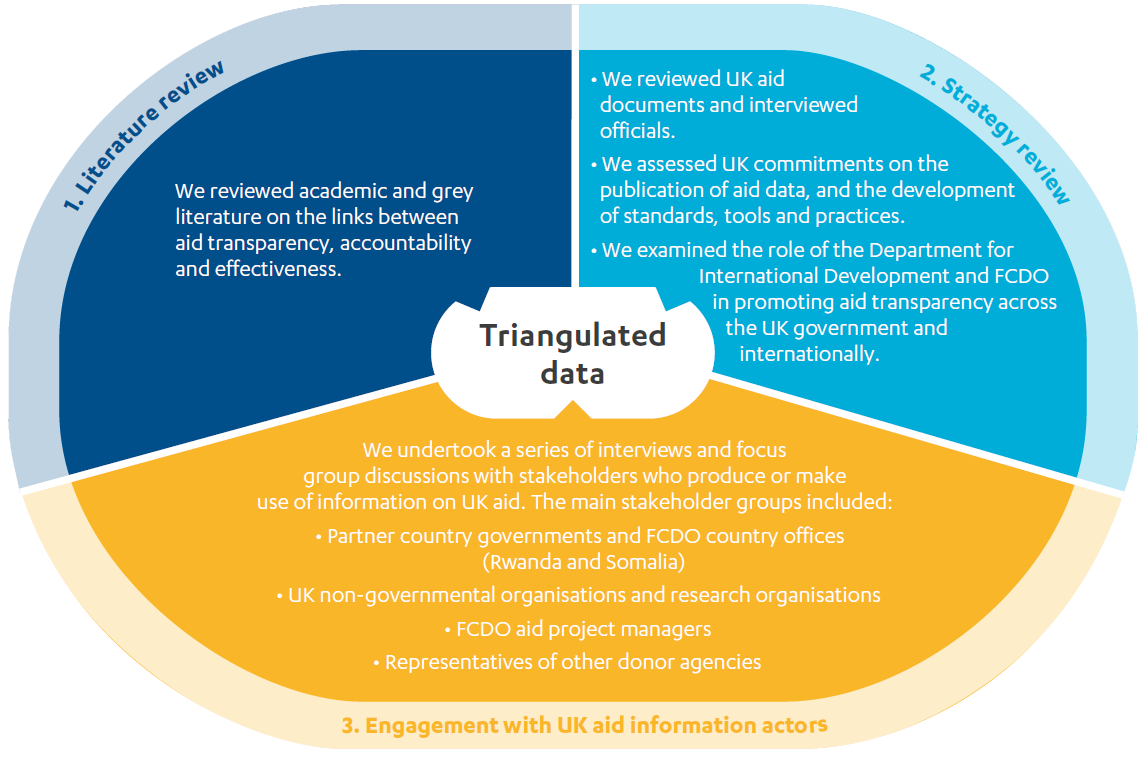

2.1 The review used a mixture of methods to answer the review questions and to provide a sufficient level of triangulation to ensure robust findings. The review methodology encompassed three intersecting elements:

- A literature review: By reviewing academic and ‘grey’ literature, we explored potential channels through which transparency helps to make aid more accountable and effective, as well as empirical evidence on how well these channels operate in practice.

- A strategy review: We explored how the UK’s approach to aid transparency has evolved since 2015 (with some contextual references to the period looking back to 2010). We looked at how policy and practice has evolved under the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), as well as, the UK’s role promoting transparency globally.

- Engagement with UK aid information actors: Through interviews and focus group discussions we collected feedback on the relevance, utility and impact of UK aid transparency efforts. We engaged with four groups of stakeholders:

i. Partner country governments (in Somalia) and FCDO country offices (in Rwanda and Somalia) – to explore country-level experiences

ii. UK non-governmental organisations and research organisations – to explore their use of aid information for scrutiny purposes

iii. FCDO aid project managers – on their experiences in applying UK aid transparency requirements

iv. Representatives of other donor agencies – on the UK’s role in promoting aid transparency globally

Figure 1: Summary of methodological elements of the review

2.2 Rwanda and Somalia were selected as countries in which we could explore how information on UK aid has helped them to more effectively manage and account for UK aid investments. They were chosen on the basis that they are significant recipients of UK aid and there have also been recent efforts by the donor community in both countries to improve the use of aid information. We interviewed FCDO officials in both countries to understand how they share aid information with local stakeholders, and we interviewed the Ministry of Planning in Somalia, to understand how they use UK aid information. We had planned to interview the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning in Rwanda but they were not available for interview within the timeframe of this review.

Box 1: Limitations to our methodology

A focus on transparency related to operational delivery – This review focused on transparency related to operational delivery of programmes, and did not focus on issues of wider corporate transparency, such as procurement processes or human resource management.

Modest country engagement – In a rapid review, there is limited scope for country-level engagement, which for this review was limited to remote interviews with ministries of finance and FCDO offices in both Rwanda and Somalia.

Light-touch evaluative approach on the links between UK aid transparency, accountability and effectiveness – We have relied mainly on existing research and insights from engaged stakeholders to identify some of these potential links.

Institutional memory on policy and practice in the early phase of UK aid transparency efforts – While we were able to identify some key individuals involved in the early years of UK aid transparency efforts to understand their objectives, others were more challenging to identify and engage.

Background

Global aid reform and transparency

3.1 ‘Aid transparency’ – the publication of information on aid flows, activities and impacts – has been an internationally agreed principle of effective development cooperation since 2005. The importance of transparency to aid effectiveness is referenced in agreements adopted at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) High Level Forums on Aid Effectiveness, a key international platform for agreeing principles of good development cooperation, which has met periodically since 2002.

3.2 At the High Level Forum in Paris in 2005, and at the High Level Forum in Accra in 2008, donors committed to sharing information on aid commitments and disbursements with partner country governments. These commitments were intended to support mutual accountability between donors and partner countries, and to enable finance ministries to record aid flows on national budgets, helping them to make better choices on allocating their development finance. In 2011, at the High Level Forum in Busan, South Korea, the transparency commitment was broadened to emphasise the importance of sharing aid information with all relevant stakeholders (including citizens, organisations, constituents and shareholders), not just governments (see Box 2).

Box 2: Relevant quotes from the Paris, Accra and Busan agreements

“Donors commit to: Provide timely, transparent and comprehensive information on aid flows so as to enable partner authorities to present comprehensive budget reports to their legislatures and citizens.”

(Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, 2005)

“We will make aid more transparent. Developing countries will facilitate parliamentary oversight by implementing greater transparency in public financial management, including public disclosure of revenues, budgets, expenditures, procurement and audits. Donors will publicly disclose regular, detailed and timely information on volume, allocation and, when available, results of development expenditure to enable more accurate budget[ing], accounting and audit[ing] by developing countries.”

(Accra Agenda for Action, 2011)

“Transparency and accountability to each other. Mutual accountability and accountability to the intended beneficiaries of our co-operation, as well as to our respective citizens, organisations, constituents and shareholders, is critical to delivering results. Transparent practices form the basis for enhanced accountability.”

(Busan Partnership Agreement, 2011)

3.3 Donor countries also agreed to publish their aid data in a standard format, so that it can be used more effectively by stakeholders, including those in developing countries receiving aid. To that end, at the Accra High Level Forum in 2008, a group of bilateral, multilateral and philanthropic donors – including the UK Department for International Development (DFID) – collaborated to launch the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI). IATI has developed a common standard for the publication of aid information and has played a central role in promoting aid transparency (see Box 3). DFID was the first donor agency to publish its aid data according to the IATI Standard in 2011.

Box 3: Background on IATI

The IATI Standard is a set of rules and guidance for publishing information about development and humanitarian aid. It identifies a wide range of categories of aid information that are important to publish, including: basic project attributes, financial data, performance information, documents, and the sub-national locations of projects. The Standard also specifies the format in which this information should be published, so as to allow this information to be more easily accessed and integrated with other financial and planning information.

So far, over 1,400 organisations – including bilateral and multilateral development organisations, private foundations and non-governmental organisations – have published aid data according to the IATI Standard, although the amount and timeliness of the data publishing varies significantly across these organisations.

IATI’s Members’ Assembly approves strategic decisions and changes to IATI’s governance, and is formed of all IATI members. IATI’s Governing Board is made up of seven representatives elected by IATI members, and its role is to make recommendations on IATI’s strategic direction to the Members’ Assembly and to oversee the implementation of IATI’s work plan by the Secretariat.

3.4 IATI aims to complement and build on aid reporting processes managed by the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC), which collects and reports information on official development assistance (ODA) provided by OECD members on an annual basis. While OECD aid statistics provide a limited level of detail and are retrospective and produced with a significant delay, the aim is that IATI data provide much more extensive detail on the nature of aid activities and are updated monthly or quarterly, to facilitate closer to real-time scrutiny and accountability.

The UK and aid transparency

3.5 Aid transparency has been an explicit commitment for successive UK governments for more than 15 years.

3.6 In 2006, Parliament passed the International Development (Reporting and Transparency) Act, which requires the government to report in detail on its aid spending and its results in supporting poverty reduction. As a signatory to the Paris and Accra agreements, the UK committed in its 2009 development White Paper to apply the highest standards of transparency to its aid. In its 2008-09 annual report, DFID also began reporting against a set of development results indicators across the organisation.

From 2010, DFID introduced an ambitious new agenda on transparency as part of a wider package of reforms aimed at promoting value for money from UK aid spending. These included efforts to promote more rigorous and evidence-based programme designs and a stronger emphasis on setting and reporting against results targets. DFID’s transparency commitments complemented these changes by providing UK taxpayers and citizens in developing countries with the means to hold DFID and its partners to account against the high standards that had been set for UK aid.

This new transparency agenda was initiated through the announcement of the UK Aid Transparency Guarantee in 2010. The Guarantee committed DFID to begin publishing detailed project data and summary information in local languages. The preamble to the Guarantee stated that these and other measures would help to ensure “that UK taxpayers and citizens in poor countries can more easily hold DFID and recipient governments to account for using aid money wisely”. DFID first published aid information to the IATI Standard in January 2011, and launched its public aid information portal, Development Tracker (hereafter referred to as ‘DevTracker’) in 2012. Both of these actions helped to enable the department to deliver this commitment. The internal procedures and rules for publishing this programme information were initially set out in the DFID Blue Book, and subsequently elaborated further in DFID’s Smart Rules, which were introduced in 2014.

3.9 The introduction of the UK Aid Transparency Guarantee was followed in 2012 by DFID’s announcement of the Aid Transparency Challenge. This committed the department to ensuring that its delivery partners also began reporting according to the IATI Standard.

3.10 Alongside a commitment to increase the volume of aid managed by other government departments, the 2015 UK aid strategy also included a commitment for all of these departments to achieve a rating of ‘good’ (score of 60%-80%) or ‘very good’ (score of 80%-100%) in the globally recognised Aid Transparency Index by 2020. This is the main commitment against which we assess the aid transparency performance of DFID, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) over the period since 2015.

3.11 In 2018, DFID published its Open aid, open societies strategy which reiterated the policy approach on aid transparency and was used as a tool for communications. Over the period from 2015 to 2019, the volume of UK aid managed by DFID increased (from £9,772 million to £11,107 million) although its share of total UK aid fell (from 80.5% to 73.1%).

Figure 2: Timeline of key UK and global events, agreements and policies on transparency

3.12 FCO signed up to IATI in 2012, and started publishing shortly after, following the publication of its IATI implementation plan in March 2013. However, it was only in 2019 that the department followed DFID by introducing a formal framework guiding its aid transparency efforts, through the publication of its Policy Portfolio Framework, which set out its rules and processes for programme management. This was despite the fact that between 2015 and 2019 the volume of UK aid managed by FCO increased from £391 million (3.2% of total UK aid) to £679 million (4.5% of total UK aid), with additional FCO-managed programmes funded through cross-government aid funds.

3.13 Following the merger of DFID and FCO to form FCDO in September 2020, the new department began work on a Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) to guide programme management and replace the DFID Smart Rules and FCO Policy Portfolio Framework. The PrOF was finalised in early 2021 and includes a set of rules and procedures guiding transparency efforts.

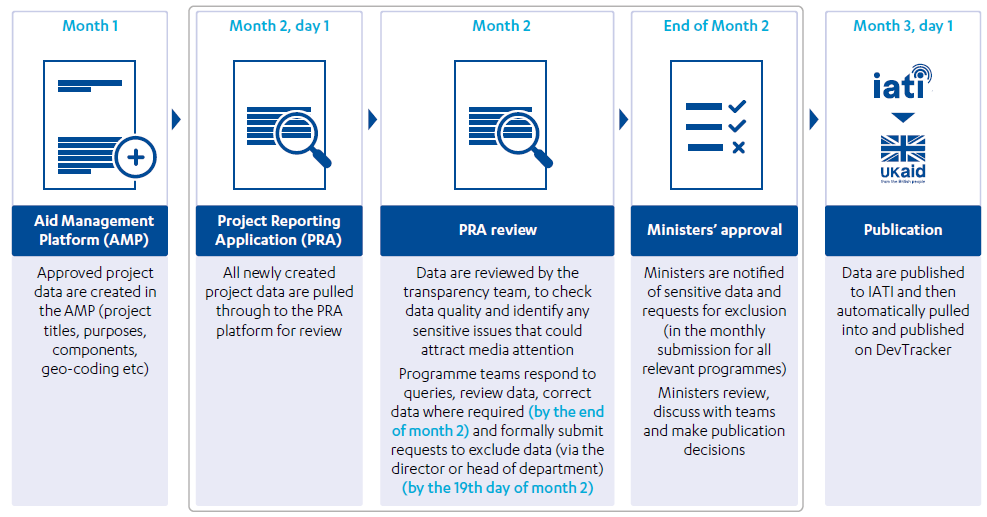

3.14 A number of cross-departmental bodies and processes have supported efforts to deepen aid transparency efforts over the period since 2015, including:

- The International Development Sector Transparency Board (2013-15) brought together government officials and UK development sector experts to explore aid transparency challenges and priorities.

- The Senior Officials Group (2016), led by DFID (now FCDO) and HM Treasury, focused initially on managing the 0.7% aid spending target before its mandate was broadened to include transparency in 2017.

- The Transparency Community of Practice was established by DFID in 2018, and used by the department to share best practice with and promote cooperation across government departments on aid transparency.

3.15 A key tool developed by DFID to support the management and publication of its information on financial flows, activities and results related to aid programmes is an internal information management system known as the Aid Management Platform (AMP). The AMP was used by DFID (and is still used for the ex-DFID portfolio in FCDO) to manage data on programme activities and view financial information, to support evidence-based management at both programme and portfolio level. A data pipeline was developed between AMP, ARIES (ex-DFID finance system), IATI and DevTracker, so that programme and financial information would be published in an automated way to DevTracker. DevTracker is powered by IATI data. The process provides for a one-to-two-month period of review (using the ‘Project Reporting Application’) to allow project information and document quality and sensitivity to be reviewed by the Information Rights Department and any decisions on non-disclosure to be appropriately addressed by ministers. This process and the timeline for publication are presented in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Illustration of the UK aid project data publication process

Source: Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 2022 (unpublished)

3.16 At the time this report was finalised, the project management systems of DFID and FCO were still in use in parallel within FCDO, as work was ongoing to develop unified programme and financial management systems for the merged department. As a result, FCDO programmes previously managed by DFID still use the AMP and follow DFID’s publication practices.

3.17 Within DFID, oversight of aid transparency policy was the responsibility of the Better Delivery Department (BDD), which was part of the Finance, Corporate and Performance Department. The transparency team in BDD was supported by a technical team in the Business Services Department, and a person responsible for handling data and exclusions in the Information Rights Department. Within FCO, oversight of aid transparency policy sat in the Portfolio Management Office and was supported by information leads in the Knowledge and Information Department. Between 2015 and 2018, the total number of officials working on aid transparency in DFID and FCO increased from around five (full-time equivalent) to 11.6, before beginning to fall thereafter. In 2022, transparency was supported by 8.1 full-time equivalent roles in FCDO.

Why aid transparency matters

3.18 Aid transparency is seen in the policy and academic literature as an important principle in its own right. Those contributing to aid (such as taxpayers and private donors) and those affected by the activities it funds should be able to see how aid is being used.

3.19 Aid transparency is also widely seen as a means of promoting accountability for aid. Building on core principles of good public administration more generally, transparency allows those contributing to aid and people affected by the activities it funds to scrutinise the performance of aid agencies and to ensure that they are ‘answerable’ to these actors.

3.20 While transparency is important for all public spending, it could be said to be particularly important for aid, given the particular dynamics of accountability facing this resource. Donors are primarily accountable to their own citizens, parliaments and media, but these citizens do not have the same direct experience or knowledge of aid as they might for domestic expenditure. Conversely, the citizens of partner countries who are intended to benefit from aid spending have few formal channels for holding donors to account.

3.21 Transparency is also seen as a means of promoting more effective aid. The precise causal link from transparency to improved effectiveness is not yet settled in the literature, but is thought to run through a range of stakeholders in both donor and partner countries, who in theory can make use of aid information for a variety of purposes. An illustration of the benefits of aid transparency and relevant stakeholders is presented in the transparency section of FCDO’s PrOF (see Box 4).

Box 4: FCDO’s case for transparency

Transparency helps us to be more accountable, efficient and effective by:

- supporting evidence-based decision-making by feeding into FCDO management information

- improving engagement with programme constituents (‘beneficiaries’), enabling empowerment of choice and control in programmes

- providing better oversight and coordination of spend

- reducing duplication by sharing information with others

- delivering comprehensive, relevant and accessible aid information to the public domain via DevTracker and gov.uk

- enabling sharing of information with countries where ODA spend supports better outcomes

- helping to track funds to downstream partners and to address corruption.

Source: FCDO Programme Operating Framework, FCDO, May 2022.

3.22 As in other areas of public policy, the links between transparency and effectiveness can be complex and involve long chains of causality, especially regarding the role of partner country stakeholders. The literature review published with this report finds that empirical evidence on these causal links is relatively scarce. Nonetheless, there was a broad consensus among stakeholders consulted for this review that, at the very least, the publication of aid data creates incentives for those managing aid to operate more diligently, thereby helping to promote higher-quality development cooperation.

Findings

4.1 In this section, we assess the relevance, effectiveness and learning approach related to the UK’s aid transparency efforts over the period since the publication of the UK aid strategy in November 2015, and especially since the establishment of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) in September 2020.

Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and coherent approach to aid transparency?

4.2 This section examines whether the Department for International Development (DFID), the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and FCDO have had clear and defensible criteria to guide decisions on what aid information to publish, and how well the type and format of aid data they published reflected the needs and interests of intended users of the data.

DFID published detailed corporate information and applied a presumption of disclosure as regards programme information, with clear and coherent criteria applied for withholding this information

4.3 Over the period from 2010 until its merger with FCO in September 2020, DFID published regular detailed reports on its operations and applied a presumption of disclosure as regards information about its programmes. Programme documentation could only be withheld from publication through an explicit decision involving ministers, based on clear and limited criteria.

4.4 At the corporate level, DFID’s transparency was facilitated by the publishing of detailed annual reports and accounts, beginning in 1999. The annual report contained information on spending across countries and thematic areas, and reported on results and performance against UK and global reform commitments and in DFID priority countries. From 2008-09, it also included information on DFID’s global development results across its main thematic portfolios, which was supplemented by publishing separate detailed corporate results reports covering the period 2011-15 and annually during 2015-20. However, to date FCDO’s annual reports have only reported on a narrow set of corporate development results, and dedicated results reports have not been published.

4.5 Since 2012, DFID/FCDO has also produced the publication Statistics on International Development (SID), which reports on official development assistance (ODA) spending across government. Provisional SID ODA data for the previous year disaggregated by department and region are normally published in April. A later version of SID (usually in September) presents final data on ODA spending for the previous calendar year, and disaggregates this data in more detail, including by country, sector and multilateral delivery partners.

4.6 As regards individual aid programmes, DFID’s 2010 Aid Transparency Guarantee committed the department to publishing information about budgets, activities and results. This commitment led to the publishing of programme documents on DevTracker – a portal the department established for making programme information publicly available – from 2011 onwards.

4.7 The specific requirements for delivering on the programme transparency commitment were initially presented in the DFID Blue Book, which guided operational management in the department. The Blue Book stated that business cases, translated intervention summaries, logframes and project reviews were to be published on DevTracker.

4.8 In 2014 DFID introduced its Smart Rules, which presented a framework of principles, rules, qualities and standards to be applied in delivering DFID programmes. Among the principles set out in this document was the requirement to be transparent, and its rules included an elaboration of the programme documents that were required to be published. These documents initially included full business cases, logframes, formal arrangements and agreements (such as contracts, Memoranda of Understanding and grants/non-fiscal programmes), correspondence, assurance documents, annual reviews and project completion reviews. Over time, this list of documents was expanded and formalised, and the main additions made in later versions of the Smart Rules were to require publication of any changes to business cases and any external evaluations.

4.9 As regards sensitive information, the Smart Rules noted that such information should “only be excluded from publication as a last resort”. When applying to withhold programme documents from publication, officials were required to justify non-disclosure based on the criteria set out in UK freedom of information legislation. There followed a process, led by the Information Rights Department, to try and resolve these sensitivities without withholding data or documents, such as through redacting certain information. If no solution was found, the application for withholding project data or documents was passed to the designated minister responsible for transparency to make a final decision.

4.10 This process is still applied to FCDO programmes managed using the Aid Management Platform (AMP), ie ex-DFID programmes. Information shared by FCDO on exclusions relating to these programmes indicates that, from July to December 2021, there were no cases where programme documents for new AMP programmes were excluded altogether, as all requests for exclusion were resolved through anonymisation or redacting of sensitive information. From January to June 2022, 19 new programmes managed through the AMP were fully excluded from publication, all of which were being implemented in Ukraine, as the department judged that they contained potentially sensitive information that could put the safety of delivery partners at risk. In addition, through a separate process, in August/September 2022 FCDO removed from DevTracker documents for all its ongoing programmes in Afghanistan, due to similar security sensitivities. Information on these programmes in Afghanistan and Ukraine is currently being reviewed so as to address sensitivities (such as through redactions), and the department plans to publish it following this process.

4.11 FCDO also shared other recent examples of ex-DFID programmes for which partial exclusions of information were agreed. These included withholding the names of implementing partners in Syria due to safety concerns, withholding the business case for a project working on LGBTQ+ rights due to safety concerns for implementing partners, and a number of programmes for which the publication of the business case was withheld temporarily to avoid publishing financial information that could undermine ongoing procurement processes. FCDO confirmed that these types of commercial confidentiality issues have historically been the most common reason for delays to publishing business cases.

4.12 Overall, these examples indicate that in practice DFID utilised clear and coherent criteria to guide exclusion decisions, and that this has continued under FCDO regarding AMP programmes.

DFID’s comprehensive approach to publication was not supported by sufficient analysis of the needs of user groups

4.13 DFID’s bold approach to publishing programme documents was not complemented with sufficient analysis of what aid information users wanted and needed. DFID lacked a structured process for engaging with and responding to user groups. We found no substantive analysis of the diverse needs of aid information users, and no attempt to tailor the form of aid data to reflect their needs.

4.14 In interviews with officials overseeing the management and development of DevTracker and SID, we heard that user analytics for these publishing tools suggested that the main users were ‘experts’ from developed countries (namely DFID/FCDO staff, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and research organisations), and that there had been limited use of data by the UK general public or by stakeholders in developing countries. As regards DevTracker, independent research commissioned by DFID in 2017 suggested that issues around the accessibility of language and the complexity of the data were a barrier to greater use by the public. We did not see any analysis undertaken by DFID with developing country users on their experiences with DevTracker and SID. The fact that such analysis was not undertaken suggests that DFID did not actively pursue the vision of its 2010 Aid Transparency Guarantee to ensure that aid transparency efforts engaged UK taxpayers and citizens in poor countries (see paragraph 3.7). This conclusion is also supported by our analysis using the UK’s International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data which found that, despite the Guarantee committing DFID to publish summary programme information in local languages, only 90 intervention summaries for UK aid programmes have been published in local languages over the last decade and the number of programme documents of any type produced in local languages fell from 54 in 2013 to just five in 2017 and three in 2020.

4.15 In addition, we noted that IATI has also faced challenges related to engaging partner country stakeholders, with implications for UK data published through this channel. The 2015 evaluation of IATI concluded that there had been limited effort to engage the users of aid information since its establishment in 2008, and more recent independent analysis suggests that developing country stakeholders are still struggling to access and make effective use of IATI data. IATI’s most recent strategic plan emphasises promoting “the systematic use of IATI data usability” as one if its three core priorities, thereby acknowledging the challenge (see paragraphs 4.91-4.93 for more discussion on IATI and user engagement). A key challenge to be addressed here is to support potential users to develop and access information technology systems for accessing, analysing and making use of IATI data, which are published in a machine-readable format and therefore require tools to be developed for processing.

FCO did not pursue a clear and coherent approach to aid transparency, leading to diverse practices across its aid portfolios and challenges for usability

4.16 Over the review period, FCO did not set out clear and coherent standards to be applied for publishing aid information, which led to a discretionary approach to publishing programme documentation.

4.17 FCO’s first specific commitments on aid transparency were set out in its March 2013 implementation plan for beginning to report its aid information to IATI. This plan was presented in the form of a spreadsheet which identified the broad categories of aid information that the department would publish, and included a commitment to ensure that information reported would be compliant with the IATI Standard by March 2014. However, this plan only provided limited detail on the types of programme documents 14 that would be published and it did not set out how reporting would be adapted to and managed across FCO’s various aid portfolios.

4.18 In October 2019 FCO published its Policy Portfolio Framework (PPF), which set out guidance and requirements for programme management and delivery. The PPF set out a commitment to the principle of transparency, but did not commit to publishing specific documents across its portfolio. Instead, the PPF noted that programme documentation such as business cases and project completion reports would be published only “in some cases”. This wording sanctioned discretionary and ad hoc decision-making on publication.

4.19 In ICAI’s view, the absence of clear guiding principles and requirements set by FCO on the publication of its programme documents allowed a discretionary approach to be pursued, resulting in a variety of publication practices across FCO aid portfolios. Programmes funded from FCO’s own aid budget, including those implemented by the British Council (£140 million in ODA in 2020) and other arm’s length bodies, generally released only summary information. However, in contrast, FCO programmes funded through the two cross-government aid funds, the Prosperity Fund (established 2014) and the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) (established 2015), routinely published some programme documentation, although not to the extent of DFID’s publication practice (see Table 2).

4.20 The two cross-government funds were supported by a dedicated administrative structure for allocating and overseeing the funds, and a set of operating rules for the recipient departments. These included transparency requirements. The CSSF required all programme teams to “produce Programme Summaries and Annual Review summaries for publication each year”, and any exemptions from publication required the agreement of the head of the CSSF. The Prosperity Fund required reporting of summary information to IATI, but left it to each department whether or not to publish programme documents.

Table 2: Overview of information published across FCO aid portfolios, as of 2020

| Mainly basic IATI overview data | Some summary programme documents | Some full programme documents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programmes funded from FCO’s aid budget | |||

| British Council (£140 million in 2020) | Tick also published annual reports and one programme report | ||

| BBC World Service (£70 million in 2020) | Tick also published annual reports | ||

| Arm’s-length bodies (Chevening Scholarships (CS), Great Britain China Centre (GBCC), Wilton Park (WP), Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD). (In 2020: CS – £2 million, GBCC – £0.5 million, WP – £1.4 million, WFD – £8.1 million (for 2020-21)) | Tick most also published annual reports | ||

| Frontline diplomatic activity (£12 million in 2020) | Tick | ||

| International subscriptions (£45 million in 2020) | Tick | ||

| International Programme (£1 million in 2020) | Tick | ||

| Programmes funded by cross-government aid funds | |||

| Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (£388 million of ODA in 2020) | Tick | ||

| Prosperity Fund (£139 million of ODA in 2020) | Tick | ||

FCDO’s internal operational guidance includes an explicit commitment to aid transparency, but maintains the publication practices of predecessor departments for FCDO’s ex-DFID and ex-FCO aid portfolios and puts a disproportionate emphasis on the issue of information sensitivities

4.21 FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) was published in April 2021 and sets out programme operating procedures for the department, replacing the DFID Smart Rules and the FCO Policy Portfolio Framework.

4.22 The PrOF sets out an explicit rule that “[a]ll FCDO programmes and projects should be as transparent as possible”, which it justifies on the basis that “British taxpayers, beneficiaries, and constituents in the countries where we operate have a right to know what we’re doing, why and how we’re doing it, how much it will cost and what it will achieve”. It is notable, though, that the use of the word “should” contrasts with the use of the word “must” in introducing virtually all of the other rules in the PrOF, which could give the impression that this rule has a different status.

4.23 In elaborating the requirements for implementing this rule, the PrOF notes that “[a]ll programmes must consider transparency at the early design stage” and that “documents and information need to be saved in a way that allows publishing to DevTracker or for Freedom of Information purposes”. It also notes specifically that for AMP programmes (that is, ex-DFID programmes) there is a requirement for records to be kept up to date and project documents to be saved correctly, as they are published automatically. However, the PrOF itself does not indicate what information is to be published for non-AMP programmes (that is, ex-FCO programmes).

4.24 In addition to the PrOF, the FCDO transparency team has produced a guide on ‘FCDO’s approach to aid transparency’ that aims to provide further guidance in this area of policy and practice across the department. The guide identifies a list of 12 documents (identical to those listed in the last version of the DFID Smart Rules) that should be published for aid programmes. It notes that these documents should be published “where they are available, and it is appropriate”, which seems to allow for some flexibility in terms of what information is published. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the diverse pattern of reporting practices applied by programmes previously managed by FCO (see Table 2) has continued since the formation of FCDO.

4.25 It is also important to note that the PrOF and its accompanying guide to aid transparency place a much stronger emphasis on managing potential sensitivities than in the DFID Smart Rules. The PrOF documents reference sensitivities much more widely than the Smart Rules and identify seven criteria most relevant to decisions to exclude information from publication compared to the five in the transparency guide accompanying the DFID Smart Rules guide. Furthermore, while in DFID’s Smart Rules the provisions on information sensitivity made it clear that exclusion from publication was “a last resort” and only for “a compelling reason”, similar qualifying statements are absent from the PrOF.

4.26 FCDO staff advised us that the PrOF’s stronger emphasis on information sensitivities reflects the greater sensitivity of the ex-FCO portfolio, and that these criteria would not necessarily lead to more extensive use of exclusions for other programming. We acknowledge that the part of FCDO’s portfolio inherited from FCO is likely to involve more sensitivities than a typical former DFID programme. However, this is a relatively small proportion of the FCDO portfolio. We estimate that, in 2020-21, only around 10% of total FCDO programme spending was on legacy FCO activities. It would therefore be unfortunate if transparency standards for the aid programme as a whole were lowered, to accommodate a small minority of cases.

4.27 We were informed that once FCDO’s unified programme and financial management systems are in place (scheduled for November 2022), there will be revisions to the PrOF to set out a more consistent and coherent approach to transparency and procedures for withholding information across the department. Discussions on these unified guidelines are yet to start, and they may not be finalised until after the department’s new systems are in place.

4.28 It is planned that, once all programmes are brought on to the AMP, the existing publication practices for AMP programmes will continue to apply. However, this is not guaranteed. A number of FCDO officials noted in interviews that there is some nervousness in parts of the department about taking a systematic approach to publication of programme information across all aid portfolios. One emphasised that transparency is not ingrained into the culture of diplomats, who are now formally overseeing aid spending in-country. Another noted that the core challenge in the department around transparency is partly culture, as the two predecessor departments had very different perspectives on this issue. Given the diverse views on transparency in FCDO, there are risks that the department will opt for a more discretionary approach to publication as its procedures and practices evolve in the coming months. Another key question is whether the current practice of rapid publication will be maintained, as significant delays to publication could undermine accountability.

4.29 In summary, the PrOF essentially maintains the pre-merger status quo for publication within FCDO, that is, with AMP (ex-DFID) programmes publishing a wide range of documents through an automatic process and non-AMP (ex-FCO) programmes publishing more selectively through a more manual process. The strong emphasis on the need to address information sensitivities in the PrOF may signal that a more cautious approach to the publication of programme documents will emerge in the future. However, key decisions on FCDO’s approach remain to be made in the coming months as the PrOF and related procedures are revised to establish unified transparency practices across the department.

There are concerns about the format of information on aid spending plans (and budget reductions) provided to Parliament

4.30 As illustrated in ICAI’s review Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target in 2020, extensive changes were made to UK aid spending plans in the first half of 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and weaker than expected economic growth, which led to adjustments of £2,347 million in DFID’s spending. Even larger additional budget reductions were announced in November 2020 as a result of a decision to temporarily reduce the UK aid spending target from 0.7% to 0.5% of UK gross national income from 2021. Information on these budget reductions and revised spending plans was only released after a significant delay (discussed in more detail in paragraph 4.70), and when it was released, the format of the information made it difficult for Parliament and other stakeholders to scrutinise these decisions.

4.31 The first detailed information from FCDO about the department’s aid allocations for 2021-22 was presented in a letter that Dominic Raab, the then foreign secretary, sent to the UK Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC) in April 2021. This letter set out aid allocations for sectors and regions, but we were informed by external stakeholders that these allocations were shared in a format that differed from previous reporting of spending and budgets, making comparisons with previous years very difficult. For example, it was not clear which countries were included in which regional groupings (such as the Indo-Pacific and South Asia region), and nonstandard sector breakdowns were used (for example, girls’ education was referenced without details on broader education spending). Stakeholders we interviewed noted that the lack of clarity on these figures hindered their efforts to scrutinise spending changes and engage in dialogue with FCDO on these decisions.

4.32 We were also informed by external stakeholders that the format of FCDO Main Estimates (details on planned departmental spending which are shared with Parliament early in each financial year) for 2021-22 grouped programmatic spending previously managed by DFID under one heading, which did not allow for scrutiny on how spending had changed within key areas of the budget.

4.33 It was noted, however, that FCDO officials worked closely with the IDC to ensure that the FCDO Main Estimates for 2022-23 included more detailed information on planned spending, which allowed for closer comparisons with previous spending plans and more effective scrutiny.

Conclusions on relevance

4.34 DFID pursued a clear and coherent approach to aid transparency, with a presumption of disclosure subject to only limited exceptions. FCO’s approach to aid transparency was more discretionary, rather than based on clear rules. FCDO has made a broad commitment to aid transparency and outlined a rules-based approach, but with ambiguities relating to the publication of programme documents across non-AMP (ex-FCO) programmes and the procedures to be followed for non-disclosure. Important decisions on FCDO’s approach to transparency will be made in the coming months.

Effectiveness: To what extent has the UK achieved its aid transparency objectives?

4.35 This section examines how well DFID, FCO and FCDO have performed in meeting aid transparency commitments and in promoting cross-government standards and good practices on aid transparency. It also presents findings from a range of stakeholder engagement activities aimed at gathering insights on the degree to which UK transparency efforts have helped improve the accountability and effectiveness of UK aid.

DFID was the most transparent major bilateral donor agency during 2012-20

4.36 Over the last decade, IATI’s aid transparency standards have emerged as the standard global metric against which the transparency of aid agencies is judged. The Aid Transparency Index, published biannually by the campaign group Publish What You Fund since 2012, uses indicators linked to the IATI Standard to track and compare the levels of aid transparency achieved by aid agencies. As noted in paragraph 3.9, the Aid Transparency Index was also referenced in the 2015 UK aid strategy, to set transparency standards for all aid-spending departments.

4.37 The Aid Transparency Index identified DFID as the most transparent major bilateral aid agency over the period 2012-20, and during 2012-18 it was among the four most transparent aid agencies overall (see Table 3 below). DFID performed well against all criteria in the Aid Transparency Index, especially in terms of reporting information on ‘organisational planning and commitments’ (including organisational strategies, policies and reports) and ‘joining up development data’ (reporting on the types of aid provided). In achieving a score of 85.3% (a ‘very good’ rating) in 2020, DFID achieved the standard required by the 2015 UK aid strategy.

4.38 According to DFID’s internal monitoring records, over the period from 2017-18 to 2019-20 only 2% of DFID business cases were formally excluded from publication due to sensitivities, and over 90% of DFID business cases were published on DevTracker. These data suggest that exclusion criteria were used sparingly to manage issues around information sensitivity. However, DFID did not monitor the publication of other categories of programme documents, such as Annual Reviews and evaluations, and trends related to their publication are therefore not clear.

Table 3: Aid Transparency Index scores and rankings for DFID and FCO, 2012-20

| Year | DFID (score / ranking) | FCO (score / ranking) |

|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 91.2% / 1st | 21.3% / 60th of 72 |

| 2013 | 83.5% / 3rd (top bilateral) | 34.7% / 26th of 67 |

| 2014 | 88.3% / 2nd (top bilateral) | 35.8% / 35th of 68 |

| 2016 | 88.3% / 4th (2nd bilateral) | Not included in ATI 2016 |

| 2018 | 90.9% / 3rd (top bilateral) | 34.3% / 40th of 45 |

| 2020 | 85.4% / 9th (2nd bilateral) | 48.6% / 34th of 47 |

Note – from 2014 the Aid Transparency Index was published biannually.

FCO aid transparency performance was much more modest, but improved, largely due to more timely reporting

4.39 FCO’s performance in the Aid Transparency Index was much weaker than that of DFID during 2012-20, and it was mostly among the bottom half of donor agencies over this period. In a 2019 assessment of aid transparency across UK government departments, FCO ranked seventh out of ten departments assessed.

4.40 Among the criteria that make up the Index, FCO scored especially poorly in relation to publishing information on its ‘performance’ and ‘finance and budgets’. This outcome was also driven by the fact that there was limited publication of programme documents for FCO-managed aid portfolios, with the exception of those funded through the CSSF and the Prosperity Fund.

4.41 However, between 2012 and 2020, FCO’s performance in the Aid Transparency Index consistently improved (by 27.6 percentage points overall), with improvements across all criteria except in relation to information on ‘performance’.

4.42 We noted from interviews that FCO’s improved score in the Index was achieved as a result of a corporate effort to improve transparency following a ‘poor’ Index rating (20%-40% score) in 2018. This effort focused mainly on streamlining the manual approval process for publication so that FCO aid information could be published in a more timely manner. Despite these improvements, FCO only increased its score from 34.3% in 2018 to 48.6% in 2020, and was 34th out of 47 donors. As a result, FCO failed to deliver on the aid transparency commitment set out in the 2015 UK aid strategy, which required an Index score of at least 60% in 2020.

FCDO’s performance in the 2022 Aid Transparency Index was lower than DFID’s

4.43 The 2022 Aid Transparency Index was the first to assess FCDO. The Index scored FCDO at 71.9% (a ‘good’ rating), which is 13.5 percentage points below that of DFID and 23.3 percentage points above that of FCO in the 2020 Index. This places FCDO 16th in terms of transparency among all donors and fourth among all bilateral donor agencies.

4.44 The FCDO performance rating is primarily an averaging of the performance of the two predecessor departments, since their portfolios are still run on separate platforms. However, given that more than 90% of FCDO aid activities which were available to be assessed in the 2022 Aid Transparency Index were ex-DFID activities (broadly in line with their share of FCDO aid spending), FCDO’s score in the 2022 Aid Transparency Index could have been expected to be much closer to DFID’s score in the 2020 Index. This outcome suggests that transparency has declined across the FCDO portfolio (including for ex-DFID programmes), a conclusion which is supported by our detailed analysis of FCDO scores against the criteria which make up the Index. This analysis identifies that FCDO scores significantly worse than DFID in relation to publishing country priorities (see Box 5), budget information, geo location of projects and (to a lesser degree) results information. It is also notable that the FCDO annual report no longer presents aggregate development results achieved by the department.

Box 5: Significant declines in transparency on country priorities for DFID/FCDO

From 2011 to 2015, DFID prepared operational plans for each of its priority countries. Detailed versions (commonly 10-15 pages) of these were published, which included an overview of the vision and objectives for DFID’s work, a framework of results indicators and targets across sectors, an overview of budget allocations, monitoring and evaluation approaches, and value for money and transparency priorities.

From 2016-17 to 2019-20, these were replaced by country business plans. Only short summaries (usually just two pages) were published, providing an overview of budgets, priority sectors and results targets, the country context, objectives and partners.

In 2020, as part of the announcement of the DFID/FCO merger, the government confirmed that all UK activity (including aid and development engagement) in priority partner countries would be directed by a single UK country plan for each country. These country plans are not public documents and no form of redacted or summary version has been published to date. As a result, there is currently no information in the public domain about the strategic objectives being pursued by UK aid in individual countries.

4.45 FCDO officials informed us that the department’s score in the 2022 Index was affected by the absence of a UK development strategy, the lack of public country plans and the fact that 2022-23 budget allocations within FCDO had not been set at the time of the final assessment undertaken for the Index (in March 2022). Although a new UK development strategy was published in May 2022, the FCDO annual report and accounts 2021-22 (published in July 2022) included only a high-level summary budget for the department, without breakdowns by sector or country, as had previously been standard. In addition, we were not made aware of any plans to publish information about FCDO country plans. This decline in transparency related to FCDO’s country plans and budgets is likely to hinder efforts to hold the department accountable for ongoing aid delivery, and will need to be addressed as a part of any effort to improve its Aid Transparency Index rating.

4.46 While FCDO’s score is markedly lower than DFID’s, it is also worth noting that the department is still helping to set the global standard in terms of the information it publishes about reviews and evaluations of its programmes. In the 2022 Aid Transparency Index, FCDO scores second-highest (after Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development) on these criteria, as a result of its routine publication of annual reviews and project completion reports for programmes. FCDO has also performed well in applying consistent referencing of delivery partners in its reporting (referred to as ‘networked data’).

4.47 The government has set out its future ambitions for aid transparency in a set of commitments in its recently updated National Action Plan for Open Government. This document includes a commitment that FCDO will improve its performance in the 2024 Aid Transparency Index and actively engage with the recommendations of the 2022 Aid Transparency Index. While valuable, this commitment fails to signal that FCDO will make substantive improvements to its aid transparency, and creates the risk that recent transparency declines will not be reversed.

4.48 Proposals for FCDO to make a more ambitious commitment to achieving an Aid Transparency Index score of ‘very good’ (by scoring 80%-100%) have been discussed in the department, but have not been adopted. We assess this level of ambition to be realistic and possible for FCDO to achieve within a short timeframe.

There was very limited transparency in relation to the 2020 aid budget reductions

4.49 As already noted, there have been extensive challenges around transparency related to the 2020 aid budget reductions (see paragraphs 4.30-4.31). The key challenge has been the long delays in publishing information on these reductions.

4.50 Limited information was published in relation to the aid reductions introduced in mid-2020 until April 2021, and full information on these reductions was not made public until the publication of the 2020-21 FCDO annual report in September 2021. UK NGOs informed us about their repeated requests for this information, which were turned down. They then took the step of making a freedom of information request for this information in February 2021, which was rejected by the government on the basis that it would be published in the 2020-21 FCDO annual report (seven months later) and due to concerns about its publication harming the reputation of FCDO.

4.51 The UK Parliament’s International Development Committee also faced similar challenges in obtaining information about these reductions and, after significant delays, received only limited information that Members of Parliament (MPs) were unable to use easily to scrutinise the changes made to UK aid spending plans (see paragraph 4.70).

4.52 These issues around transparency in reporting on aid reductions to stakeholders in the UK meant that partner organisations and the people expected to be affected by aid programmes similarly experienced reduced transparency. It was reported that even when information on revised lower budgets was provided to UK aid contractors, they were instructed not to discuss these reductions publicly.

DFID (and now FCDO) have supported modest but useful in-country work on aid transparency

4.53 Through our interviews in Rwanda and Somalia, we identified some examples of ongoing efforts by FCDO to support transparency and reporting of aid information from across the donor community to governments.

4.54 In Rwanda, FCDO is supporting a detailed mapping of donor support on teacher training, to help local government better coordinate the support and to allocate its own budget for teacher training to regions and schools that are not receiving donor support.

4.55 In Somalia, DFID helped to develop the Aid Management Information System, which is used to facilitate donor reporting of aid. This system has enabled the Ministry of Planning to generate more detailed reports on the aid being provided to different sectors and regions, helping to facilitate more detailed planning and coordination.

4.56 During our evidence gathering phase we requested information from FCDO on all programmes with a specific focus on promoting aid transparency at the country level. In response, FCDO informed us of a project in Nepal called Evidence for Development which included support to the Ministry of Finance to upgrade its own Aid Management Platform, which facilitates donor reporting on aid. The objective is to link this platform to the government’s budget management systems, and eventually to enable public access to aid data.

4.57 We are not aware of any other major DFID/FCO programmes at the country level to support aid transparency specifically. This does not include work on aid transparency through support for strengthening public financial management, or supporting country governments to be transparent with their own citizens about their budgets, where FCDO has carried out work. Overall, it seems that this area of programming has so far been modest. However, we note that the UK funds IATI, which has carried out some work in this area.

DFID (and now FCDO) played an important role in supporting other departments on aid transparency

4.58 The commitment in the 2015 UK aid strategy for all departments to achieve the standard of ‘good’ or ‘very good’ in the Aid Transparency Index helped to leverage a role for DFID to support efforts to improve aid transparency in other departments.

4.59 DFID played this role primarily through two formal cross-government groups and one other informal group that it convened. First, DFID co-chaired (with the Treasury) the cross-government Senior Officials Group, which was formed in 2016 and brought together officials at director level to discuss aid issues, including transparency, on a quarterly basis. Second, DFID established the Transparency Community of Practice in 2018, which also met quarterly and was used to convene technical-level officials to share best practice and address challenges on transparency. Finally, on a more informal basis, from 2018 DFID also attended a monthly meeting with the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) to discuss and address ongoing transparency challenges.

4.60 Officials from BEIS, DHSC and FCDO noted that these groups were especially important in supporting departments in the lead-up to and during major assessments of UK aid transparency. For example, we were informed that during a 2019 review of UK aid transparency, DFID used the Transparency Community of Practice to help departments understand the methodology of the review, to coordinate departments’ work in engaging with the review and to troubleshoot any problems they faced during the process.

4.61 We noted from BEIS and DHSC that through their regular meetings and follow-up activity (which was supported by programme resources), DFID supported them to develop their own internal aid information management systems, to develop guidance on internal procedures and delivery partner transparency, and to troubleshoot technical problems as they emerged. We also noted that FCDO worked closely with BEIS to support it during the assessment for the 2022 Aid Transparency Index (in early 2022), as it was the first time that BEIS had been through this process. Finally, the CSSF informed us that FCDO had played a challenge function role in encouraging the Fund to expand the information it publishes about its programmes.

4.62 The Transparency Community of Practice did not meet between January 2020 and November 2021. This was largely due to the redeployment of transparency team members to roles supporting the response to COVID-19 in early 2020, and also because of demands for designing new transparency rules, procedures and systems to support the DFID-FCO merger.

4.63 Beginning in November 2021, the Transparency Community of Practice began a more regular cycle of meetings. Discussions at the November 2021 meeting focused mainly on the upcoming Aid Transparency Index assessment of FCDO and BEIS, the treatment of Afghanistan data, the international development strategy and a range of issues around DevTracker and IATI reporting. It then met again in April 2022 to discuss updates for this ICAI review, delivery partner transparency guidance, monitoring of internal compliance and a potential future cross-government transparency review. Its most recent meeting was in July 2022, when departments met to discuss commitments on transparency that could be made through the National Action Plan for Open Government, engagement with IATI, and the application of FCDO’s IATI guidelines to UK government delivery partners.

4.64 Finally, it is important to note that DFID/FCDO have organised an annual ODA learning day for departments managing UK aid, which has included a focus on transparency. The most recent of these learning days, in April 2021, included a focus on learning around external ODA reporting, among other themes.

DFID took a leading role in promoting aid transparency, both globally and in the UK

4.65 The UK, led by DFID, was one of the founders of IATI in 2008 and was the first agency to publish data according to the IATI Standard, in 2011. Officials from other donor agencies that we interviewed all agreed that, without DFID’s support, IATI would not have been established, and that DFID had played a central role over an extended period in supporting the technical work needed to develop the IATI Standard, which became the global norm for publishing aid information. This in turn helped encourage higher levels of aid transparency from other UK government departments managing aid, as they were judged against this standard.

4.66 In addition, since the introduction of the 2012 Aid Transparency Challenge (see paragraph 3.7), DFID’s delivery partners and their subcontractors have been required to report to IATI and to make efforts to improve their transparency. Officials from other donor agencies that we interviewed noted that this step led to a significant increase in new organisations reporting to IATI, which in turn increased pressure on those agencies not yet engaging with the Initiative. DFID also advocated for multilateral aid organisations to improve their transparency, including by making transparency a criterion when assessing their effectiveness during the 2016 Multilateral Development Review, which informed the decisions on the allocation of UK multilateral aid.

4.67 However, a clear insight from our interviews with officials from other donor agencies was that the UK’s political and technical leadership in IATI has waned in recent years. FCDO officials informed us that this outcome was due to the reduced human resources available on transparency (see paragraphs 4.86-4.91), which resulted largely from the competing demands of the COVID-19 response and the merger of DFID and FCO, as well as restrictions applied within FCDO on recruiting new staff externally.

Information on UK aid is widely used to undertake scrutiny of UK aid spending, but recent transparency weaknesses have hindered this scrutiny

4.68 In our roundtable with UK NGOs and research organisations, a wide range of examples were presented of how these organisations have used available aid information to undertake scrutiny of and promote public debate on UK aid (see Box 6).

Box 6: Examples of NGO and research organisations’ use of published UK aid information

- The effects of aid reductions – A number of NGOs used the UK’s IATI data to identify patterns of expenditure emerging after the reductions in aid introduced in 2020 and 2021, and to identify the potential impacts of these reductions on particular sectors.

- Ambitions on aid to support women and girls – An NGO used published information on UK support for women and girls before the aid reductions to produce a briefing which set out the spending commitments required to reverse reductions in this area of spending.

- Promoting awareness of the impacts of UK aid – One NGO noted that it used results information presented in DFID/FCDO annual reports to promote awareness of the impact of UK aid among its supporters.