Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition

Score summary

The Department for International Development (DFID) surpassed its goal of reaching 50 million people with nutrition services between 2015 and 2020. The result is valid but misses other important achievements of the department, including building global and national commitments to reduce undernutrition. DFID was successful in reaching many of the most vulnerable women and children, but could have done better by strengthening data systems and investing more in the development of local delivery capacity. The UK aid nutrition portfolio is making significant contributions to reducing malnutrition but could increase its impact by expanding work on healthy diets, and promoting the increased convergence of different programmes on the most vulnerable communities.

Malnutrition is a major cause of preventable deaths in all countries and constrains social and economic development. The Department for International Development (DFID), which has now been merged into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), played a leading role in advocating for nutrition to be a priority. It helped to strengthen political leadership and commitments on reducing undernutrition at both the global and national levels. The Government’s commitment to reach 50 million people with nutrition services between 2015 and 2020 was surpassed early. The methodology used to calculate these results is robust, and helped DFID advisers to understand better the importance of high-impact, multi-sector nutrition programming. However, measurement inaccuracies and inconsistencies across DFID’s country offices highlight the difficulty of applying complex results methodologies in practice. Despite improvements, the UK’s nutrition results are still overly focused on reporting outputs, and it is difficult to tell whether individuals have received support from several different sectors to tackle malnutrition.

Those targeted by DFID’s nutrition programmes – women of childbearing age, adolescent girls and children under five – are some of the world’s most vulnerable to undernutrition. DFID’s ability to work within highly constrained environments, including crisis contexts, to ensure that its nutrition programmes reached these target groups was impressive. Evidence of reaching acutely malnourished children in climate-affected and food-insecure regions demonstrated the department’s capacity to deliver life-saving nutrition services to some of the most vulnerable citizens. However, DFID did not consistently reach the most marginalised within its target groups, including the chronically ill, and did not always fully understand their needs. Weak national data systems, as well as the increasing burden placed on volunteers who often deliver nutrition services, continue to be major challenges.

By championing a multi-sector approach, which addresses the underlying as well as the direct causes of undernutrition, DFID’s programming aligns with the evidence on “what works”. Although most countries are not on track to meet global nutrition goals, many of DFID’s target countries have seen long-term decreases in stunting. DFID’s programmes have made positive contributions towards this trend, as well as influencing additional political and financial commitments to nutrition. Future impact on nutrition can be enhanced through working with FCDO’s partners to strengthen the portfolio’s approach to working across different sectors, including on nutritious food systems, and emphasising the convergence of different interventions on the most vulnerable.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Effectiveness: How valid are DFID’s reported nutrition results? |  |

| Question 2 Equity: Are DFID interventions reaching the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach women and children? |  |

| Question 3 Impact: To what extent is DFID helping to reduce malnutrition? |  |

Executive summary

“We know that if a child is not given the right foods, they will be stunted – they will have weak bodies, the child will be a slow learner.”

“The children should be given kapenta, bananas, boiled eggs, soya bean, groundnuts, milk, meat and vegetables. So that the children can have nutrients. But we don’t have such food or money to buy such food.”

“The parent should eat food important for the child’s growth such as fish, vegetables, so that the child can have nutrients. But [the foods] are very difficult to source for poor people like us.”

Focus group participants, Sioma District, Zambia

Good nutrition is a fundamental prerequisite for the development of an individual and a country. It is essential for a healthy immune system and cognitive, motor and emotional development. Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for good nutrition is further heightened: nutritional well-being can help protect the most vulnerable from the risk of severe illnesses. However, the burden of malnutrition remains alarmingly high and poses a significant threat to livelihoods, communities and economies. One in nine people in the world are hungry and around 45% of all deaths among children under five are linked to undernutrition. Now COVID-19 and the associated response are predicted to cause a huge increase in the number of people facing hunger and malnutrition.

In recent years, recognition of the benefits of investing in nutrition has increased and significant strides have been made to ensure that tackling undernutrition is a global priority. Nutrition interventions are consistently identified as highly cost-effective. The UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) and its nutrition policy team have been at the forefront of the increased focus on reducing undernutrition. In 2013, the UK held the first Nutrition for Growth Summit, culminating in the signing of the Global Nutrition for Growth Compact by 94 stakeholders, including development partners, businesses, scientific organisations and civil society groups. In 2015, the UK’s commitment to eradicate hunger and prevent undernutrition was highlighted through the government’s pledge to reach 50 million people, with a particular focus on women and children, with its nutrition services by 2020. Since this commitment, DFID has published its nutrition results, detailing the number of women of childbearing age, adolescent girls and children under five reached by its programmes.

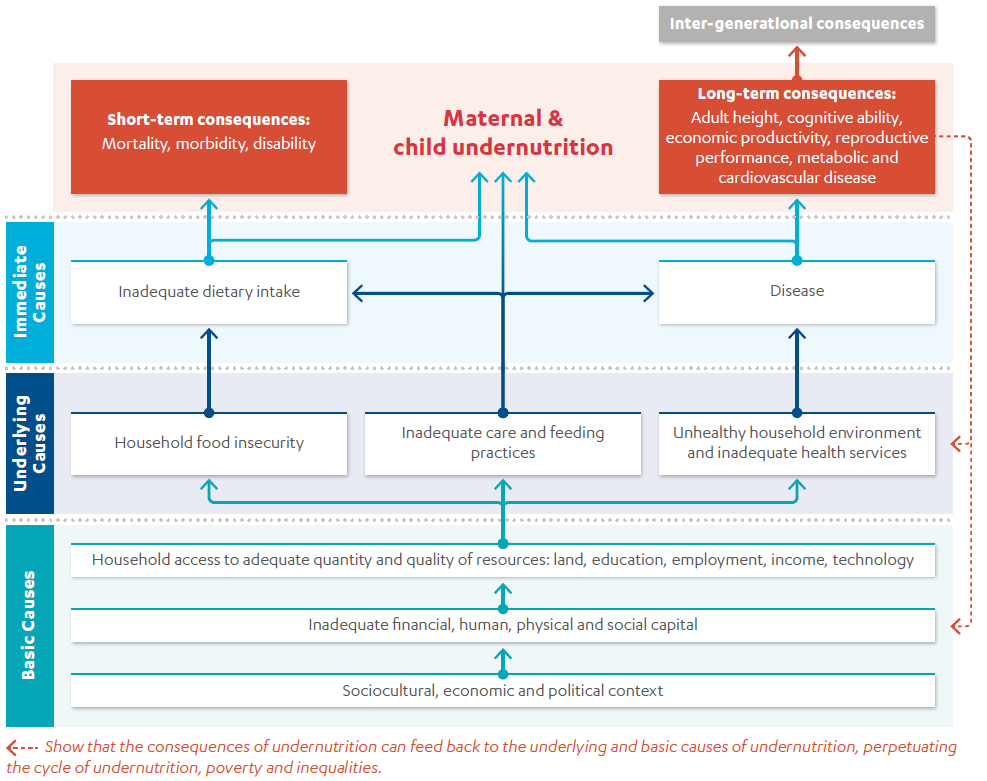

The causes of maternal and child undernutrition are complex. Undernutrition is the immediate consequence of an inadequate diet and disease. But it is also related to underlying problems including food insecurity, poor sanitation and hygiene and inadequate health services, as well as wider factors related to poverty, climate change and conflict. Tackling the problem effectively and sustainably therefore requires a combined, multi-sector approach. The literature recommends ‘nutrition-specific’ health interventions to address the direct causes of malnutrition (including micronutrient supplementation, breastfeeding advice and treatment for acute malnutrition). It also recommends ‘nutrition-sensitive’ approaches, which involve tailoring and/or targeting other sector programmes (such as water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), education, social protection and agriculture) to help address the underlying causes of malnutrition. DFID has encouraged an approach whereby these different interventions ‘converge’ on groups vulnerable to undernutrition, to help maximise their impact. The literature also recognises that achieving this approach is only possible if high-level political commitment is combined with strong technical capacities and if development partners align their actions with government-led plans. Technical assistance and advocacy work have therefore been further important elements of DFID’s work.

This review assesses the nutrition results claimed. It examines the methodology used to calculate these results and interrogates the validity of the reported global figure. It also considers how meaningful these results are through the lens of whether the nutrition programmes are meeting their objectives. Understanding whether the programmes reached and met the needs of the most vulnerable and marginalised is another central aspect of the review. Finally, the review judges the longer-term impact of DFID’s approach on undernutrition. This is based upon DFID’s use of evidence, the contributions of its technical assistance and advocacy work, and programme impact.

Overall, ICAI finds that DFID has made important advances in response to ICAI’s previous nutrition review, published in 2014, including significant progress on improving its nutrition results methodology, country programme implementation and national systems strengthening. Given that DFID only started scaling up its work on nutrition in 2013, these achievements are impressive. However, based on ICAI’s recommendations from 2014, progress should have been more rapid in the interrelated areas of targeting the most vulnerable mothers and children, and strengthening national data systems.

Effectiveness: How valid are DFID’s reported nutrition results?

Reported nutrition results have been based on the number of women of childbearing age, adolescent girls, and children under five reached through DFID’s nutrition interventions. The methodology used to calculate these results has been closely aligned with evidence of “what works”, since it encourages targeted interventions that combine nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive services (classified by DFID’s methodology as high-intensity interventions).

The methodology has provided a useful tool for DFID country offices to scrutinise the effectiveness of their nutrition programmes. The inclusion of the intensity categorisation enabled DFID advisers to explore how to achieve the convergence of a range of nutrition services that address the direct and indirect causes of undernutrition. However, the results methodology did not capture DFID’s wider advocacy and technical assistance work. ICAI found evidence that DFID secured political commitments and strengthened national systems to combat undernutrition, but these achievements have not been reflected in its results framework.

DFID reported that it reached 50.6 million women, children under five and adolescent girls through its nutrition programmes between April 2015 and the end of March 2019, mostly through what it defined as medium-intensity reach. The department pursued a cautious approach to calculating its results and acted to revise these where discrepancies were discovered. The reported results are broadly valid. However, ICAI found that reporting against the nutrition results methodology was complex and a resource-intensive exercise for staff, and that this led to some inaccuracies and inconsistencies across individual programmes. Reliance on poor-quality programming, and especially national data systems, presented a significant challenge in reporting results.

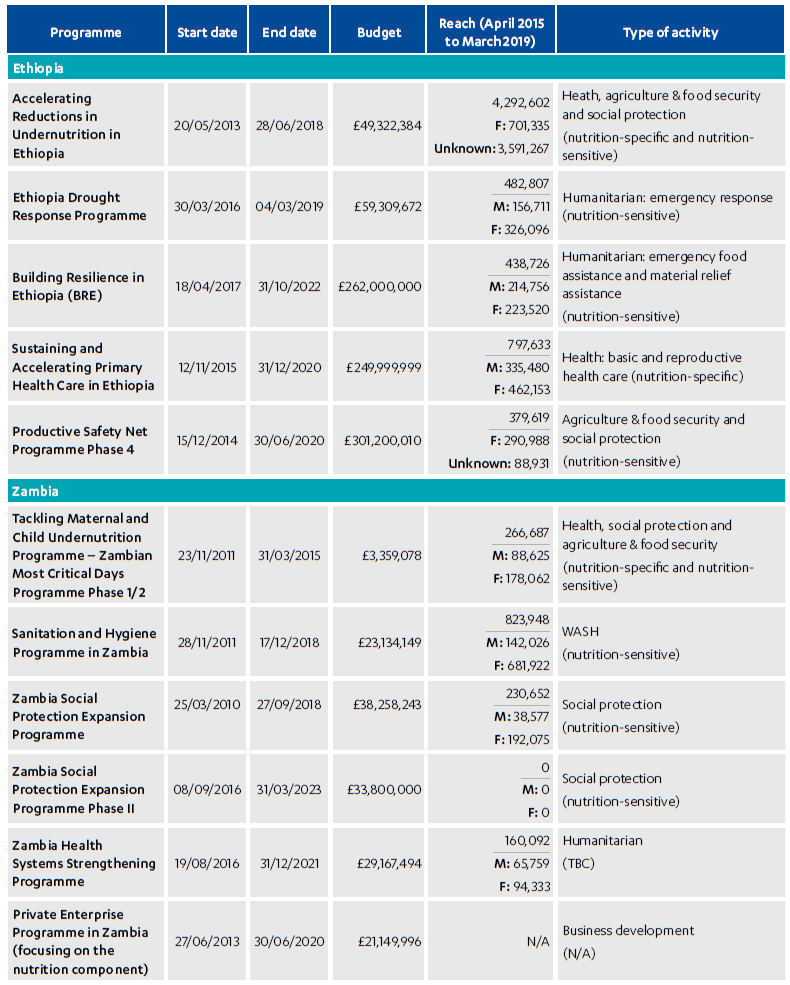

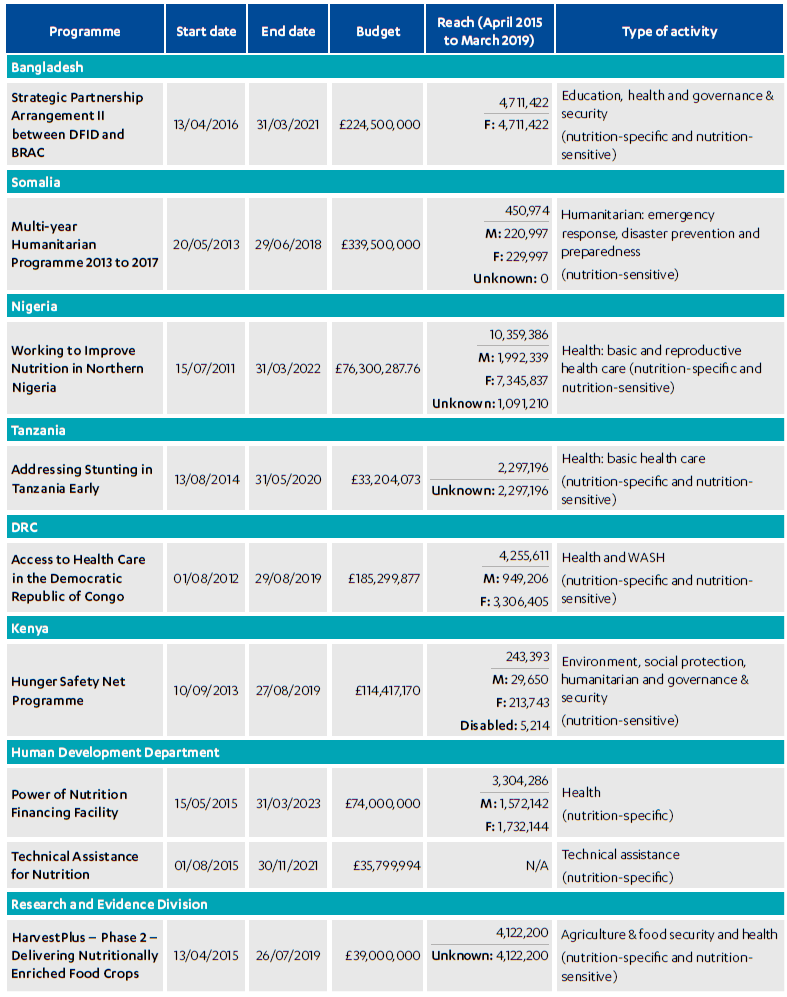

The review includes a sample of 20 nutrition programmes, 18 of which contributed to the overall nutrition results. Most of these programmes have been judged by ICAI to be effective in achieving their immediate objectives, based on nutrition output and outcome targets. Programmes are most successful when there are efforts to strengthen the political and technical coordination of services, secure political commitments to nutrition and strengthen local delivery capacity.

DFID met its reach target and pioneered a new results methodology, and most of its nutrition programmes have been delivering against their immediate objectives. The accuracy of programme results and the measurement of their outcomes are, however, areas for future improvement. ICAI has therefore scored the effectiveness of the approach as green-amber.

Equity: Are DFID interventions reaching the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach women and children?

The UK’s Global Nutrition Position Paper reaffirms UK aid’s commitment to ’leave no one behind’ and reach the most vulnerable, excluded and disadvantaged people. The most vulnerable to undernutrition are children, especially during the first 1,000 days of life, as well as women of childbearing age and adolescent girls. Support to these groups will deliver the most benefit. DFID’s interventions to date have demonstrated impressive results in reaching these groups, including treating children with acute malnutrition within crisis contexts.

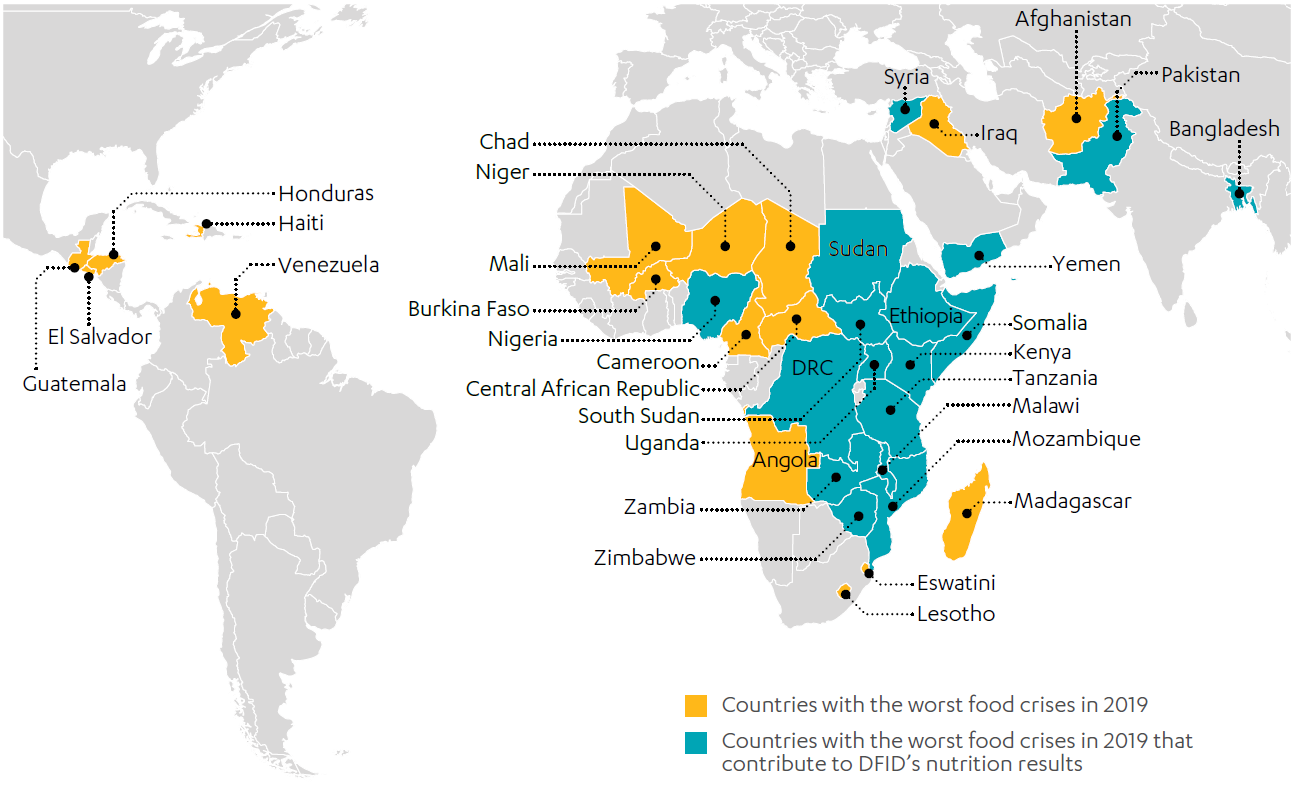

Good practice in targeting nutrition interventions involves a combination of geographic targeting and targeting households with vulnerable groups. DFID’s nutrition programmes have targeted countries (and regions within countries) with a high burden of undernutrition. DFID reported that 85% of its nutrition results have come from countries categorised as ‘highly fragile’ or ‘fragile’, where stunting and wasting tends to be most acute. Sixteen out of the 55 countries classified by the Integrated Food Security Classification as having the worst food crises contributed to the results (from 23 countries with bilateral nutrition programmes).

Through its nutrition portfolio, the UK has been working within challenging environments facing extreme poverty, drought and conflict, where the capacity to identify, target and reach the poorest households is limited. However, ICAI was impressed with DFID’s ability in many cases to navigate these obstacles, including by building on and strengthening existing community structures and resources such as ward committees and health volunteers.

However, ICAI found that DFID’s interventions did not always reach the most marginalised within the target groups, for example households headed by a disabled person, migrant women, and those in the remotest communities, nor did they always monitor their take-up of services. ICAI also found insufficient understanding within DFID of who the most vulnerable are and how to reach them, due to a lack of detailed guidance, sharing of lessons learnt and targeted citizen consultation.

The achievement of reaching vulnerable women and children through nutrition programmes in such challenging contexts is impressive. However, a lack of disaggregated targets, weak data systems, and limits to the capacity of volunteers mean that there is room for improvement in reaching the most marginalised. ICAI has scored DFID’s work in this area as green-amber.

Impact: To what extent is DFID helping to reduce malnutrition?

By committing to a comprehensive approach that targets both the direct and the underlying causes of undernutrition, DFID’s nutrition strategy has been strongly evidence-based with the potential to be highly impactful. ICAI found that DFID has been considered a strong global leader in nutrition and has played an important role in increasing the international focus on undernutrition. The UK convened international events and supported the development of indicators for global nutrition targets. At the national level, DFID strengthened political leadership and helped to increase financial commitments to nutrition. In Zambia, Ethiopia and Nigeria, ICAI found impressive examples where DFID’s advocacy and technical assistance work contributed to the longer-term integration of nutrition within government services and programmes, and particularly health care. External stakeholders observed that further work is needed to promote greater cross-government cooperation and investment in nutrition from different sectors.

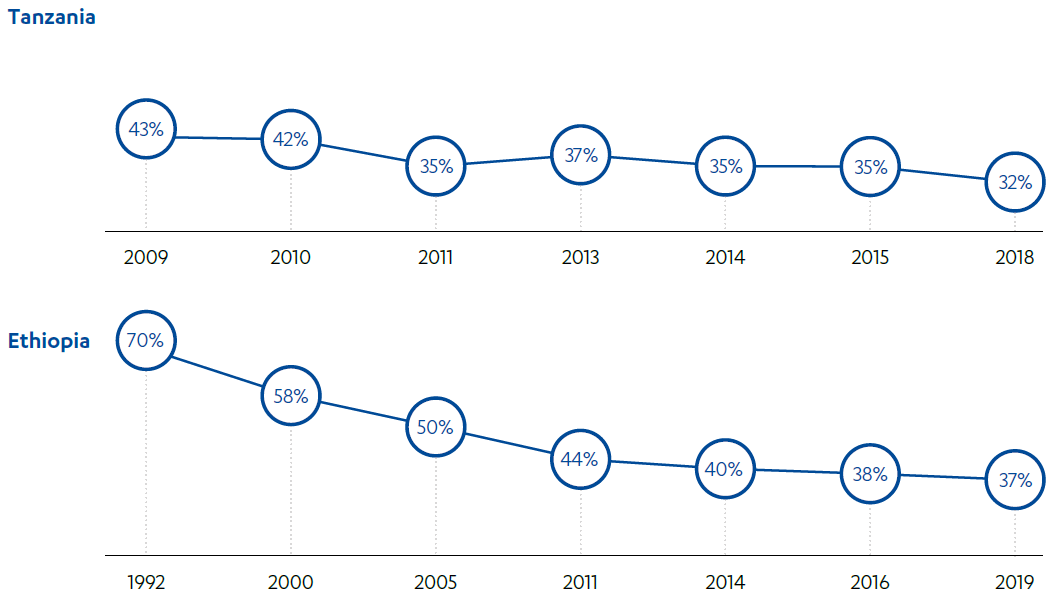

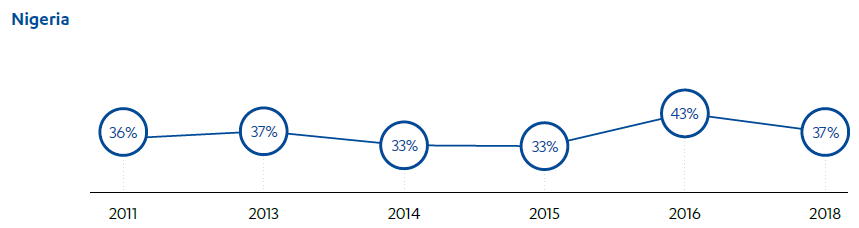

While most countries are not on track to meet the global nutrition targets set for 2025, or the Sustainable Development Goal of ending malnutrition by 2030, many target countries are experiencing long-term decreases in stunting. DFID’s programmes have made positive contributions to this trend. In the most extreme contexts, such as Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Northern Nigeria, they helped to prevent the situation from worsening, through treating large numbers of children suffering from acute malnutrition.

Programme impacts on undernutrition are nonetheless not as great as anticipated, and robust evaluations helped DFID to learn critical lessons. These include the importance of increasing population coverage, ensuring convergence of services (for example nutrition and WASH) on the most vulnerable communities, and addressing the underlying drivers of malnutrition more comprehensively. For example, DFID has made some progress in improving the contribution of commercial agriculture work to nutrition but there is a need to accelerate the approach to strengthening food systems at country level, to help make sustainable and nutritious diets accessible to all. More generally, the department had begun to assemble learning on “what works” across nutrition-sensitive programming, but this is not yet fully embedded across the portfolio.

DFID’s evidence-based approach and effective programmes mean that the portfolio has strong potential to support reductions in undernutrition over the longer term. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and its partners will need to do more to strengthen nutrition work in sectors such as agriculture, and to develop a comprehensive intervention package that converges on the most vulnerable communities. ICAI has therefore awarded a green-amber score for DFID’s nutrition impact.

Recommendations

Although this report looks back at the work of DFID, our recommendations are directed to the FCDO following the merger of DFID with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. They are intended to strengthen the new department’s future approach to nutrition.

Recommendation 1

FCDO should capture and communicate progress against all goals in its nutrition strategy, including strengthening systems and leadership for improved nutrition.

Recommendation 2

FCDO should strengthen statistical capacity and quality assurance in-country and centrally, to support more accurate measurement of programme coverage and convergence, and to use the data to improve nutrition programming.

Recommendation 3

FCDO should strengthen systems for identifying and reaching the most marginalised women and children within its target groups.

Recommendation 4

FCDO should more consistently gather citizen feedback to help improve and tailor its nutrition programmes.

Recommendation 5

FCDO should scale up its work on making sustainable and nutritious diets accessible to all, to help address the double burden of malnutrition, through nutrition-sensitive agriculture and private sector development.

Recommendation 6

FCDO should work more closely with its partners to achieve the convergence of nutrition interventions, by aligning different sector programmes to focus on those communities most vulnerable to malnutrition.

Introduction

“The livelihoods of many people became very hard, living like chickens not knowing what to eat the following day…”

“A lot of people were dying. Children and adults alike … my own children nearly died.”

Focus group participants, Shangombo District, Zambia

Malnutrition is a critical contributor to ill health, vulnerability, poverty and mortality. Worldwide, 820 million people are ‘chronically undernourished’ – 8.9% of the world’s population is believed to be hungry. Infants, young children and pregnant and breastfeeding women are most vulnerable to undernutrition. Their bodies have a greater need for nutrients per kilogram of body weight, such as vitamins and minerals, and are often more susceptible to the harmful consequences of deficiencies. 47 million children under five years of age are wasted, 14.3 million are severely wasted and 144 million are stunted. Undernutrition in children often leads to deficiencies in height and can impact brain development, meaning that full cognitive potential is not reached. Poor nutritional status in women often perpetuates a cycle of poverty and ill health for both the mother and her child. Children are at the highest risk of dying from wasting. Many infant and young child deaths in lower-middle-income countries are attributable to the poor nutritional status of the mothers. Malnutrition also encompasses overnutrition (the ‘double burden’) – a further 2 billion people are overweight or obese worldwide, according to UN joint estimates. The UK aid nutrition strategy is focused on tackling undernutrition, although it aims to minimise the risk of obesity.

Unsurprisingly, those countries with the highest burden of undernutrition are low- and middle-income countries. More than half of all stunted children live in Asia and more than one third in Africa. More than two thirds of wasted children under five live in Asia and more than one quarter in Africa. Across 53 countries, 113 million people experience acute hunger and 135 million people experience acute food insecurity as a result of conflict, climate shocks and economic turbulence, alongside structural factors related to poverty. Those already experiencing protracted crises, including in fragile and conflict-affected states, are more vulnerable to malnutrition.

Nutrition interventions are consistently identified as one of the most cost-effective development actions, with significant economic returns. Every $1 invested in reducing stunting can yield $11 in return. The Lancet Series has identified the ten key clinical interventions that can help solve the problem (see Box 4). However, reaching the most vulnerable with basic health care is complex in countries with few resources. Furthermore, UNICEF’s framework for the determinants of child undernutrition demonstrates that the problem has multifaceted causes and requires multifaceted solutions (see Figure 1). Undernutrition is a consequence of an inadequate diet and disease, such as diarrhoea, pneumonia and tuberculosis. These immediate causes are a consequence of limited access to sufficient and nutritious food, inappropriate maternal and childcare practices, inadequate health services and insanitary environments. Food, health and care are affected by social, economic and political factors including poverty, gender inequality, child marriage, poor education (especially for girls), political and economic marginalisation, and poor governance. These underlying factors explain why progress on reducing undernutrition is stalling in the poorest countries, and especially in the regions with the most vulnerable people within these countries.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of the determinants of child undernutrition

Source: Adapted from Improving Child Nutrition: The achievable imperative for global progress, UNICEF, 2013, p. 4.

Combatting malnutrition is both a development and a humanitarian priority worldwide. In 2012, the World Health Assembly endorsed the first ever global nutrition targets, which included tackling stunting, wasting, anaemia and low birth weight. At the Second International Conference on Nutrition in 2014, more than 170 governments committed to establish national policies and plans aimed at achieving the global nutrition targets. In 2015, world leaders enshrined these commitments in Sustainable Development Goal 2 and committed to end all forms of malnutrition by 2030.

However, most countries are lagging behind their targets and World Bank analysis highlights that there is still a large gap in the investment needed to reach the global nutrition goals. Data from UNICEF and the World Health Organisation shows that the number of stunted children under five in Africa increased from 50.3 million to 58.8 million between 2000 and 2018. Climate-related shocks and conflict are important drivers of this increase, with problems concentrated in the poorest countries and increasingly the poorest regions within countries. The global food system adds to the challenges of reducing malnutrition. Food chains prioritise processed products, to increase quantity of sales and profit margins, rather than nutritional quality, therefore making it difficult for consumers – especially those below the poverty line – to make healthy and affordable food choices.

Following the Nutrition for Growth Summit hosted in London, in 2015 DFID pledged to reach 50 million people. In late 2017, DFID launched its new global nutrition strategy to tackle undernutrition, prioritising support to the first 1,000-day window from conception through to two years of age, as well as preventing “the most severe forms of undernutrition” in children up to the age of five.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is exacerbating the immediate and underlying causes of malnutrition and significantly threatens the potential for the global nutrition targets to be achieved. The World Food Programme has warned that an additional 130 million people could be pushed to the brink of starvation by the end of 2020. Due to preventative measures restricting the movement of people and goods, COVID-19 presents an unprecedented threat to economies, food systems and health systems. This could lead to an additional 1.2 million child deaths. The most vulnerable population groups, and those already experiencing protracted climate and conflict related crises, are likely to be disproportionately affected. The need for multi-sectoral action to combat the added pressures of COVID-19 and continue to deliver life-saving assistance is recognised by the global community. The coronavirus pandemic makes the topic of this review more relevant than ever.

This ICAI review assesses the accuracy of DFID’s claimed results (2015-19) and the robustness of the methodology used to calculate these results. It assesses the extent to which the nutrition portfolio targets and reaches the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach households, and the mechanisms used to understand their needs. Finally, the review assesses the impact of the nutrition programming that contributes to the reported results. This includes advocacy and technical assistance work at global and national levels, to foster action on nutrition.

The review questions were developed in 2019 to evaluate the UK’s current and previous work on nutrition, which at the time was being delivered through DFID. In order to maintain consistency with our approach paper, we have not updated these questions to reflect the merger of DFID into FCDO. As nutrition programming will continue, the questions remain relevant for continued UK programming.

Table 1: Review questions

| Review criteria and question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness: How valid are DFID’s reported nutrition results? | • How relevant is DFID’s results methodology? • How accurate are DFID’s nutrition results? • To what extent are DFID’s nutrition interventions achieving their immediate objectives? • What are the key factors influencing the achievement of immediate objectives? |

| Equity: Are DFID interventions reaching the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach women and children? | How well do DFID interventions reach the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach women and children? |

| Impact: To what extent is DFID helping to reduce malnutrition? | • Is DFID’s portfolio likely to achieve outcomes of reducing undernutrition over the longer term? • To what extent is DFID delivering high-impact interventions? |

Box 1: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. Nutrition is relevant to several SDGs, most directly Zero Hunger (SDG 2) and Good Health and Well-being (SDG 3).

Related to this review:

![]() Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere. Preventing malnutrition is one of the UK’s primary objectives to tackle extreme poverty. Combatting malnutrition helps people escape extreme poverty, increases economic growth, and supports people to be more resilient in the longer term.

Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere. Preventing malnutrition is one of the UK’s primary objectives to tackle extreme poverty. Combatting malnutrition helps people escape extreme poverty, increases economic growth, and supports people to be more resilient in the longer term.

![]() Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture. UK aid’s nutrition portfolio aims to combat malnutrition in women of childbearing age, adolescent girls and children under five. It aims to provide nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive services together to help maximise impact on malnutrition.

Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture. UK aid’s nutrition portfolio aims to combat malnutrition in women of childbearing age, adolescent girls and children under five. It aims to provide nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive services together to help maximise impact on malnutrition.

![]() Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. The nutrition portfolio aims to integrate nutrition services into wider health systems, strengthening those systems where possible through capacity building and technical assistance.

Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. The nutrition portfolio aims to integrate nutrition services into wider health systems, strengthening those systems where possible through capacity building and technical assistance.

![]() Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. DFID aimed to enhance the nutrition-sensitivity of its investments, including water, sanitation and hygiene. Clean water and sanitation can positively contribute to improved nutritional status, especially in children under five.

Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. DFID aimed to enhance the nutrition-sensitivity of its investments, including water, sanitation and hygiene. Clean water and sanitation can positively contribute to improved nutritional status, especially in children under five.

![]() Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries. UK aid’s nutrition portfolio demonstrates a commitment to ‘leaving no one behind’ through reaching the extreme poor and the most vulnerable. DFID’s establishment of nutrition target groups (women of childbearing age, adolescent girls and children under five) helps to tackle inequalities because undernutrition disproportionately affects these sub-groups.

Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries. UK aid’s nutrition portfolio demonstrates a commitment to ‘leaving no one behind’ through reaching the extreme poor and the most vulnerable. DFID’s establishment of nutrition target groups (women of childbearing age, adolescent girls and children under five) helps to tackle inequalities because undernutrition disproportionately affects these sub-groups.

Methodology

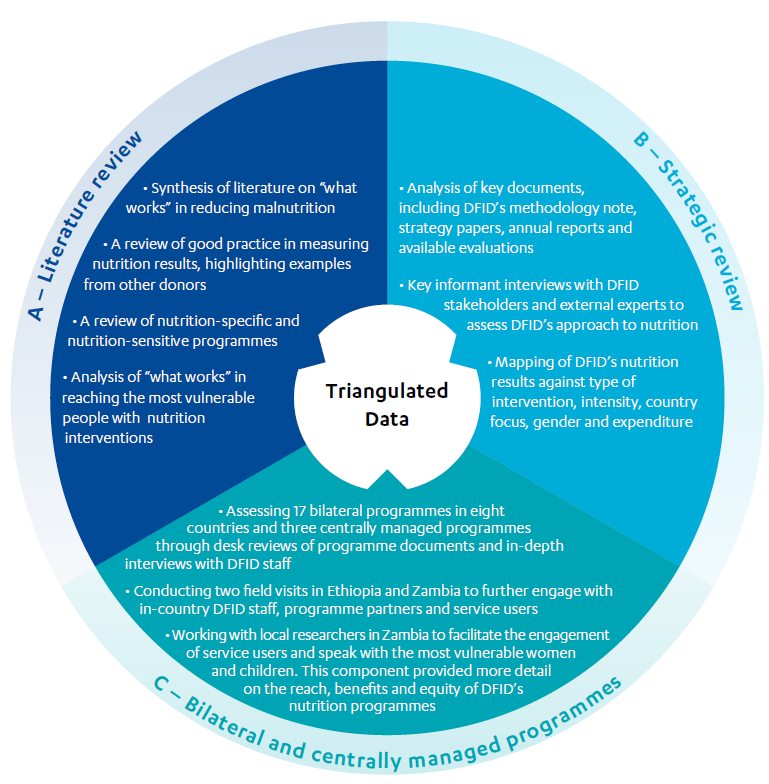

To assess DFID’s nutrition approach and results at portfolio level and at programme level, this review adopted a methodology consisting of three components.

Figure 2: Methodological approach

Component A – Literature review

A literature review was produced to identify areas of consensus around “what works” in reducing undernutrition.

Component B – Strategic review

Based on interviews with DFID staff and external experts, and desk reviews of key documents, including DFID strategies, annual reports, guidance documents and policies, we conducted a detailed assessment of DFID’s nutrition portfolio including its approach to calculate nutrition results. We also mapped DFID programme expenditure and results since 2015 against the intervention typologies including intensity of provision, the range of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions, country focus and gender split, as well as against stated targets in business cases and logframes. We also assessed the influencing role played by DFID within key international forums and partnerships to support the assessment of the department’s wider and longer-term impacts.

Component C – Bilateral and centrally managed programme assessments

Through a sample of 17 bilateral programmes implemented across eight countries and three centrally managed programmes, we have tested the quality of programme data that fed into DFID’s global results claims (see Annex 1 for a complete list of programmes and countries included in the sample). We also assessed DFID’s ability to reach the most vulnerable population groups through these programmes, and how far the programmes have aligned with best practice to reduce undernutrition, and triangulated these findings with evidence of impact. The programme reviews involved desk reviews of programme documentation (business cases, monitoring data, annual reviews and independent evaluations), followed by in-depth interviews with DFID programme managers. A detailed assessment framework was used to gather, analyse and triangulate evidence for each programme, enabling systematic analysis against each review question.

We also conducted analyses at country portfolio level, across eight countries. This was to help assess whether DFID had adequately mitigated the risk of double-counting results, and to understand the extent of multi-sector programming and integration of activity, as well as broader impacts on undernutrition. In two of these countries, Ethiopia and Zambia, we conducted field visits, which enabled us to engage in more depth with programme partners, external stakeholders and service users, and explore whether programmes are reaching the most vulnerable, as well as strengthening government systems and capacity.

In Zambia, we undertook a longer visit to enable more in-depth engagement with service users and citizens. We worked with national researchers to identify and access vulnerable women and children involved in DFID’s programmes. Semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions were undertaken in hard-to-reach programme areas, supported by clear guidelines and ethical protocols. This helped ensure that the voices of ordinary citizens were reflected in our findings and recommendations.

Box 2: Limitations of the methodology

Review scope and coverage: The multi-sector nature of nutrition programming, as well as the range of intensities and fragile/non-fragile state locations, presented a challenge for the review as a very large potential scope of work. We therefore narrowed the scope of the review to ensure sufficient depth. Work focusing on the macro-level drivers of nutrition outcomes, such as climate change, trade, economic growth, food prices and land use policies, is not included within the scope of the review. The review’s focus is on DFID’s achieved results and impact, although the evolving strategic approach is considered.

Data on effectiveness and equity: The nutrition portfolio’s results data are aggregated from individual programmes but come from a variety of secondary sources. We were not able to complete detailed verification exercises with the data. Instead, we interrogated the indicators, methodologies and assumptions behind the data, and triangulated reported results with other sources. For example, to help understand whether the most marginalised have benefited from DFID’s nutrition programming, we included a programme of service user consultation. However, this only represents a small sample of citizens.

Data on impact: The long causal pathways associated with reducing undernutrition (and associated measures of stunting and wasting), the range of other actors involved and frequent data limitations means that assessing and attributing impact at country level is challenging. To provide a credible assessment of impact, we triangulated a range of available evidence. This included the extent to which DFID’s nutrition strategy and interventions have been aligned with global literature on “what works”, evidence of shorter-term programme effectiveness (in other words nutrition outcomes, such as dietary improvements or changes in feeding practices), and evidence of programme impact from robust external evaluations.

Background

The UK government is a leading advocate for tackling malnutrition in the world’s poorest countries. Following the UK’s hosting of the global Hunger Summit during the London 2012 Olympic Games, in 2013 the UK co-hosted the first Nutrition for Growth Summit. This aimed to galvanise global efforts to tackle undernutrition, helping to secure £2.7 billion in new financial commitments from donors, alongside £12.5 billion from nutrition sensitive investments. DFID’s subsequent pledge in 2015 to reach 50 million people was a significant advance on the UK’s previous goal of reaching 20 million people from 2011-15. In 2015, DFID disbursed a record $1 billion of official development assistance to nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive programmes, reportedly reaching a total of 13.3 million children under five, women of childbearing age and adolescent girls. The share of bilateral aid spent on nutrition grew from 9% in 2013 to 11% in 2017, reflecting global increases in spend on nutrition. Box 3 provides a summary of DFID’s nutrition approach and goals.

Box 3: DFID’s nutrition approach and goals

Following the UK’s commitment in 2015 to reach 50 million people through nutrition services, DFID’s Global Nutrition Position Paper (2017) set out new priorities for scaling up nutrition interventions:

- preventing wasting, micronutrient deficiencies and low birth-weight, alongside existing work to prevent child stunting

- addressing the nutritional needs of women and adolescents, particularly adolescent girls

- strengthening the breadth and quality of DFID’s nutrition-sensitive multi-sector investments

- enabling countries to be ready for the future by strengthening leadership and delivery, and by building resilience to future shocks

- achieving a global architecture for nutrition that works in support of countries that face a high burden of malnutrition

- improving the quality and availability of nutrition data.

In addition, DFID also outlined the following objectives:

- Increasing its support for nutrition-sensitive interventions to address the underlying and root causes of malnutrition alongside nutrition-specific services in the same places, to maximise impact and improve value for money.

- ‘Leaving no one behind’ by focusing on reaching the extreme poor, the most marginalised and those in fragile and conflict affected states.

- Preparing for the future by supporting government leadership, capacity and system strengthening to deal with current and new challenges to nutrition, including from climate and environmental change and urbanisation.

- Leveraging private sector investments that are beneficial to nutrition – for example, by helping to remove barriers that prevent poor people from accessing markets for nutritious foods and promoting responsible business behaviour.

DFID also committed to empower international leadership and coordination, facilitate effective action by multiple partners and actors, drive innovation and build evidence of good practice, and promote accountability on a global scale by leading by example.

DFID’s approach to nutrition programming has reflected the global literature by classifying interventions into two groups: ‘nutrition-specific’ and ‘nutrition-sensitive’. Nutrition-specific interventions aim to address the problem directly (and include nutrient supplementation for women and children, support for infant and young child feeding, and treatment of acute malnutrition). Nutrition-sensitive interventions are those that address the multiple underlying causes of undernutrition (for example a lack of access to safe water and sanitation – which leads to diarrhoeal disease, food insecurity and inadequate health care systems). While the evidence base is strongest for nutrition-specific programmes (see Box 4), both are needed to tackle undernutrition sustainably.

Box 4: The nutrition-specific intervention package with a strong evidence base

A 2013 Lancet article identified the ten nutrition-specific interventions with the strongest evidence for contributions to reductions in child mortality. These are:

- periconceptional folic acid supplementation or fortification

- maternal balanced energy protein supplementation

- maternal calcium supplementation

- multiple micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy

- promotion of breastfeeding

- appropriate complementary feeding

- vitamin A supplementation in children aged between 6 and 59 months

- preventive zinc supplementation in children aged between 6 and 59 months

- management of severe acute malnutrition

- management of moderate acute malnutrition.

If these ten interventions were to be scaled up to 90% coverage, the authors argue that the current total of deaths in children younger than five years can be reduced by 15%, stunting reduced by 20.3% (33.5 million fewer stunted children) and the prevalence of severe wasting reduced by 60%.

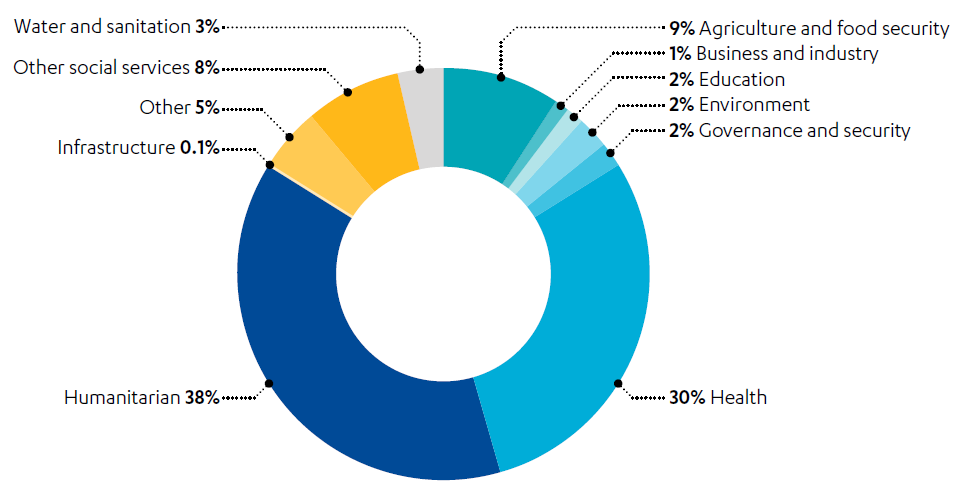

UK aid’s portfolio of nutrition programmes therefore span a range of sectors. In some countries, DFID has supported stand-alone, multi-sector nutrition programmes, which integrate nutrition-specific interventions with WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene), nutrition-sensitive agriculture and livelihoods, women’s empowerment, and/or education campaigns. In other countries, DFID has mainstreamed nutrition across different sector programmes, such as humanitarian response, social protection and private sector development. According to a classification of DFID’s nutrition projects, 40 out of 147 in 2017 included both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive components.

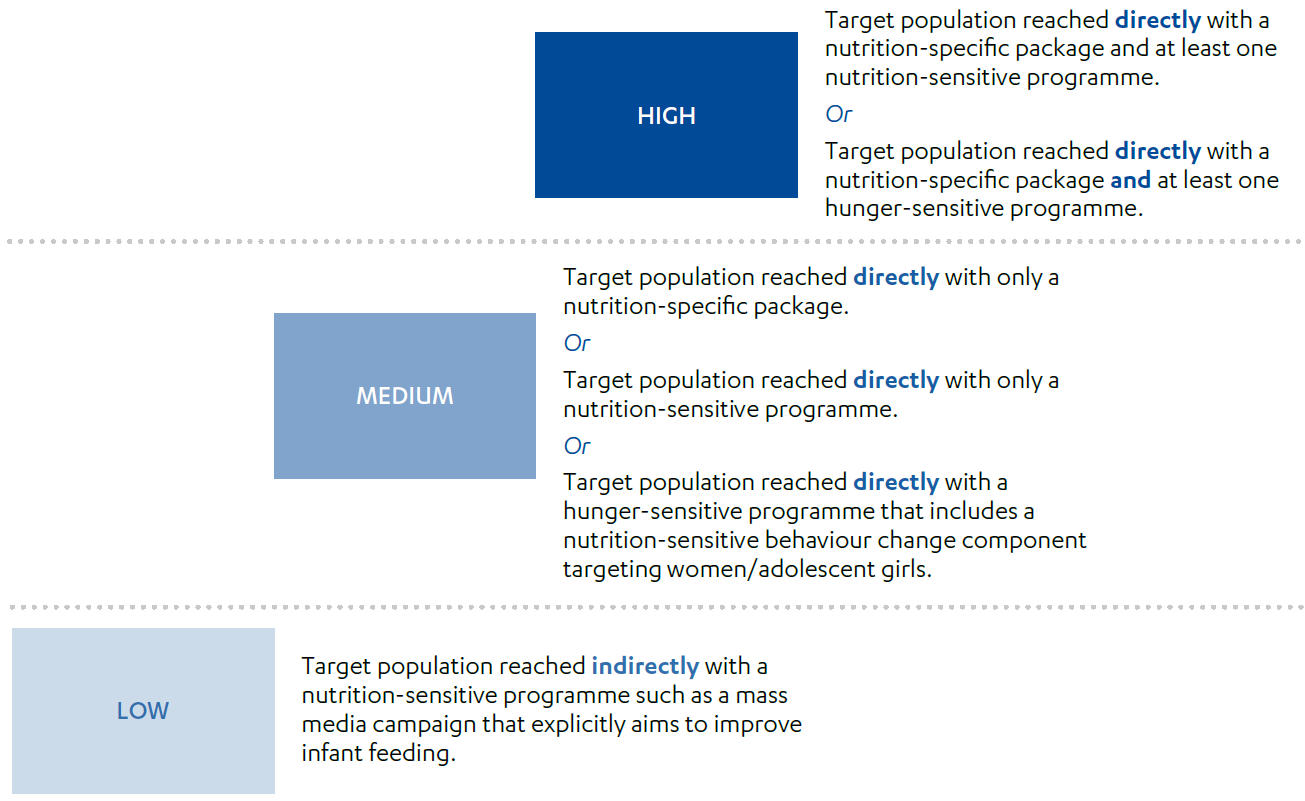

DFID’s methodology to calculate its nutrition results and reach has also evolved. Up to 2015-16, DFID defined ‘reach’ as “the number of children under five, and breastfeeding and pregnant women reached through DFID’s relevant projects”. However, this did not distinguish between those people reached by a single nutrition intervention, and those receiving both nutrition-specific support and nutrition-sensitive interventions tackling underlying causes. Since 2015-16, DFID classified reach into high, medium and low intensity, with the aim of promoting a ‘convergence’ of interventions on target groups (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: DFID’s intensity classification of nutrition interventions

DFID’s methodology note introduced further criteria to encourage the reporting of quality results. Results should only be counted as nutrition-specific if a woman or child is receiving a comprehensive package of support, and if the treatment for acute malnutrition is successful. Nutrition-sensitive results should only be counted where a programme has a clear nutrition objective and outcomes and impacts are being monitored, and ideally where there is evidence of nutritional change.

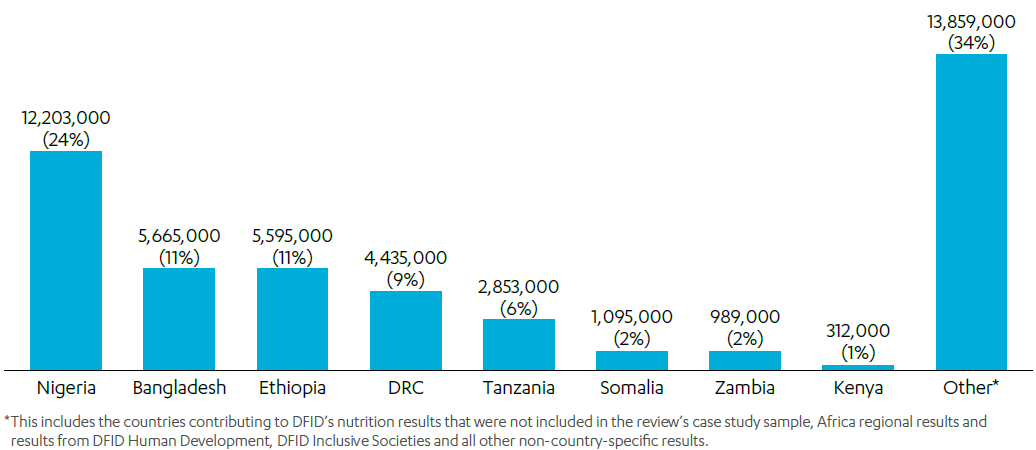

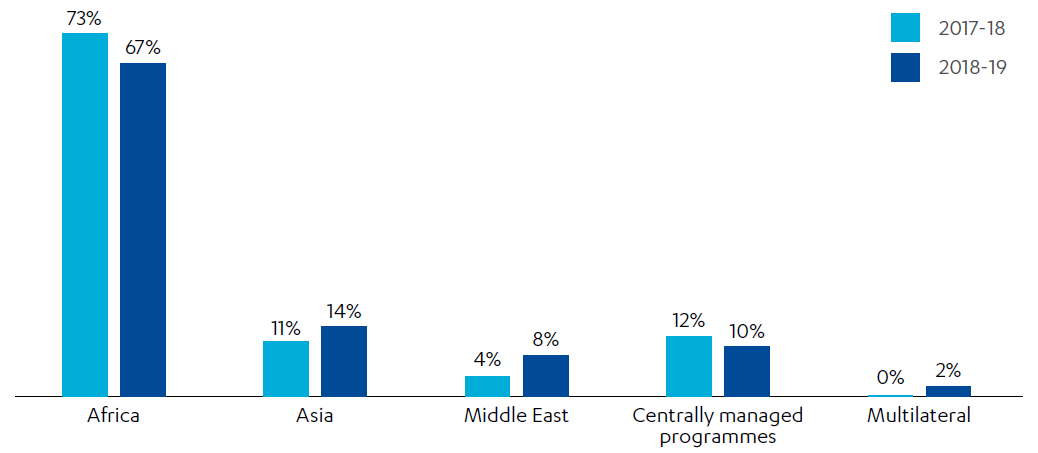

The nutrition portfolio’s results from bilateral programmes span 23 countries across Africa, South Asia, the Middle East and South East Asia (the remainder come from centrally managed and other non-country-specific programmes). The eight countries covered by this review account for 65% of DFID’s nutrition results or reach overall, between 2015 and 2019 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Number of children under five, women of childbearing age, and adolescent girls reached in review countries and their contribution to DFID’s nutrition results (%) (2015-2019)

In addition to reaching the most vulnerable, a further priority for the nutrition portfolio is eradicating undernutrition over the longer term. DFID recognised that it could not do this alone and should work with and help strengthen the capacities of other actors, not least governments, to achieve adequate coverage of services and sustainable impact. The 2017 Nutrition Position Paper frames DFID’s advocacy and technical assistance work as central to this goal. Through this work, DFID aimed to build the necessary leadership, capacity, funding and action to tackle undernutrition, working with global and national partners. Programming includes the centrally managed Technical Assistance for Nutrition programme (£35.8 million), through which UK aid supports the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement and strategy development within SUN countries.

In 2014, ICAI reviewed DFID’s emerging work on nutrition, awarding it a green-amber score. While there were promising signs of progress, ICAI found that the potential impact of the portfolio could be increased through more targeted and integrated interventions (see Box 5). At the time of the review, however, it was too early to tell whether DFID’s nutrition programmes had been successful, with very few evaluations completed. With this current review, we have had more evidence from which to assess effectiveness and impact, as well as for checking DFID’s results. Now is a timely opportunity to provide an update on progress.

Box 5: Key findings and recommendations from ICAI’s 2014 nutrition review

Findings:

- DFID played a key role in mobilising the global community to invest in nutrition through the scale-up of its own work since 2010.

- The pace and scale of DFID’s global work was positive, although country-level programme implementation could have been more rapid.

- DFID’s work was appropriately balanced between nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific programming and was based on sound evidence. However, nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive programmes were not always implemented in the same communities, and the nutrition-specific package was not always focused on interventions with the greatest impact on stunting.

- DFID provided valuable technical assistance to build government delivery capacity and was effectively coordinating with other donors.

- Service users were appropriately involved in the design of projects, but projects needed to be tailored to target the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach children better.

- DFID’s use of reach figures had limitations as they only measured a single intervention and was often based on unverified assumptions.

- Theories of change required a greater focus on intermediate outcomes and risks, and DFID needed to improve the monitoring of its programmes and ensure that results were not over-reported.

Recommendations:

- DFID should make longer-term commitments to maintain the pace and scale of its nutrition investments.

- DFID should target the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach mothers and children better.

- DFID should invest in country- and global-level systems that generate robust data on nutrition.

- DFID should explore how to effectively engage the private sector to reduce undernutrition.

Findings

In this section, we set out our findings on the accuracy of DFID’s claimed nutrition results (2015-19) and the effectiveness of the nutrition programmes in achieving their immediate goals. We also include our findings on DFID’s ability to reach the most vulnerable citizens, and the likely longer-term impact of the department’s strategy and programmes on undernutrition, based upon the available evidence.

Effectiveness: How valid are DFID’s reported nutrition results?

The measurement of reach is innovative and drives an increased focus on quality programming, although it does not reflect all goals within UK aid’s nutrition strategy

DFID’s nutrition results are based on the number of children under five, women of childbearing age and adolescent girls reached by nutrition programmes. Responding to a key criticism of the 2014 ICAI review (see Box 5, above), as well as the general limitations of a results measure based on reach, in 2015-16 DFID introduced the intensity classification. The intensity classification closely reflects the scientific evidence on what works: that combined nutrition interventions (high-intensity reach) will have a greater impact on nutrition than nutrition-specific or nutrition-sensitive programmes alone (medium- and low-intensity reach). By counting individuals who receive multiple interventions, and including other quality criteria (see para 3.5), the new methodology has driven the reporting of more meaningful nutrition results.

ICAI found that reporting against the global target of reaching 50 million people with nutrition services has been helpful for increasing a general focus on nutrition within DFID, and prioritising this within country offices. Country staff told ICAI that the revised results methodology has also helped them to scrutinise the effectiveness of their nutrition programmes more closely, and to hold key delivery partners (such as UNICEF) to account. Specifically, counting high-intensity reach has encouraged country advisers to think about how to achieve the convergence of different nutrition programmes to achieve greater impact for vulnerable populations. This also responds well to a key finding from the 2014 ICAI review, that DFID needed to make greater efforts to implement different programmes in the same communities.

DFID used the guidance to count broadly relevant nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive activities in the portfolio’s reach results. Nutrition-specific interventions relate to the high-impact package recommended by The Lancet, including the provision of vitamin A supplements, deworming tablets, iron and folic acid tablets, and counselling on infant and young child feeding. Nutrition-sensitive results come from a range of relevant interventions, from water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), women’s empowerment and small-scale agriculture through to social protection. Some programmes, including in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia, span both (see Box 6).

Box 6: Tackling Maternal and Child Undernutrition Programme, Zambia

The Tackling Maternal and Child Undernutrition Pilot Programme (2011-13) aimed to improve nutrition by delivering vitamin A and deworming tablets to children in nine districts of Zambia and was assessed by ICAI in its 2014 review. Phase I of the programme (2013-18), known as Zambia’s First 1,000 Most Critical Days Programme (MCDP), was launched through a pooled Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) fund with contributions from DFID, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) and Irish Aid.

MCDP is a multi-sector programme that aims to reduce stunting in Zambia to 25% in targeted districts by focusing on the most critical period: the first 1,000 days of a child’s lifetime. The programme focuses on scaling up a set of routine evidence-based nutrition-specific interventions proven to reduce stunting. As the theory of change highlights, improved nutritional intake is necessary but not sufficient to improve nutrition outcomes. Therefore, nutrition-sensitive interventions, for example promotion of safe water, hygiene and sanitation and complementary feeding, are implemented alongside these direct nutrition-specific interventions. Volunteers from different sectors often come together to conduct joint community outreach activities. Because the programme aims to ‘converge’ the package of services on the same population, programme results are classified as high-intensity.

Through focus groups with local citizens, ICAI heard how they have had access to infant and young child feeding counselling, seeds (beans, groundnuts and sorghum), and treatment and care for acutely malnourished children. Households are taught to grow, preserve and consume a diverse range of more nutritious foods. Service users highlighted their increased knowledge of good nutritional practice:

“A child should be given different types of food. Vegetables, foods that give energy like nshima, fish and the body building foods, they are important for the health of a child and for the child’s growth.”

“We add groundnuts to the porridge, sugar or milk.”

Focus group participants, Sioma District, Zambia

Under Phase I of MCDP, DFID reported that it reached 266,687 women of childbearing age and children under five during its ‘peak year’. This is a pro-rated estimate based upon DFID’s financial contribution to the pooled fund. An independent evaluation found positive effects on feeding practices, young children’s nutritional intake and reduced probability of diarrhoea, relative to children in comparison districts, as well as reductions in stunting among target districts for children aged between six and 23 months. However, less progress was made on increasing the coverage and take-up of nutrition-specific services (iron and folic acid supplements and deworming pills) by pregnant women, and effective convergence of services was not always possible to achieve in practice, due to the difficulty of coordinating different government sector budgets.

The programme has also helped increase engagement from senior leadership within the Zambian government and the political prioritisation of nutrition. For example, in 2018 Zambia hosted a National Nutrition Summit, supported by DFID, UNICEF and other partners, where the vice president announced several commitments, including allocating budgets to prevent stunting. Phase II of the programme (2019-2021) supports the scale-up of interventions to over 30 districts and is currently funded by the UK, the government of Zambia, the US, Germany and Sweden. In addition, USAID provides funding for a learning and evaluation component. The EU is also planning to support Phase II.

The results methodology does not capture wider strategic commitments and contributions to nutrition, achieved through advocacy and technical assistance work. These have included securing political commitment and systems strengthening, leveraging the private sector, and fostering effective international leadership and coordination. ICAI found that DFID has not systematically reported on these results. This represents a missed opportunity to communicate and learn from DFID’s overall ‘story of change’. By contrast, USAID reports on progress against all of the objectives within its Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Strategy (2014-2025), guided by a monitoring and learning plan. USAID undertakes three periodic assessments to monitor progress and gather evidence for learning (the first of which was undertaken in 2019).

DFID data shows that it met its global nutrition target (50 million people), despite taking a conservative approach to estimating its overall reach

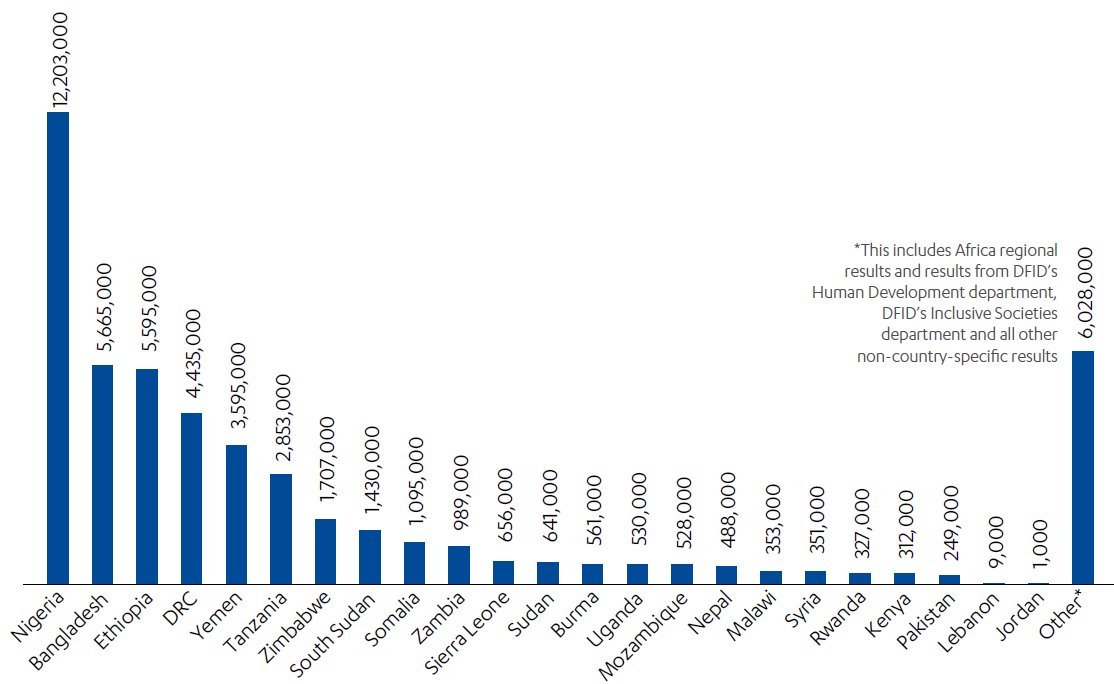

DFID reported that 50.6 million women, children under 5 and adolescent girls were reached by its nutrition interventions over the period 2015-19. Figure 5 shows all countries which contribute to DFID’s overall nutrition results, by volume.

Figure 5: DFID’s nutrition results by country (number of children under five, women of childbearing age, and adolescent girls reached, 2015-19)

Source: DFID results dataset 2018 to 2019, DFID, 2019, link. The data for this graph has been taken from Table 8 of the dataset: Number of children under five, women of childbearing age and adolescent girls reached by DFID through nutrition-related interventions.

While ICAI found some inaccuracies for individual programmes (see paras 4.9 to 4.15), overall DFID has taken a cautious approach to estimating its global nutrition results, avoiding overstatement of its success. In the case of some programmes, DFID’s reported results are likely to represent an underestimation of true reach. On this basis, ICAI concludes that DFID’s nutrition result is broadly valid. DFID has taken a conservative approach to estimation through adopting the following methods:

- Avoiding double-counting the same individuals benefiting from different programmes, different components within the same programme, and nutrition support received over multiple years.

- Adjusting its programme results downwards where other donors are providing funding, based upon its proportional funding contributions.

- Excluding results from programmes which could potentially be classified as nutrition-sensitive, but which neither had a clear nutrition objective, nor were monitoring nutritional improvement, in line with the results guidance. The clearest examples of this relate to WASH programming.

In January 2020, a major revision resulted in DFID’s nutrition reach being revised downwards by 9.7 million people (from 60.3 million). DFID’s central nutrition team and country office staff had identified potential double-counting in Somalia and Yemen and within the Power of Nutrition programme. The revision also incorporated further improvements to the quality of the results data, including in the attribution of results to DFID (based upon the latest financial information), and the exclusion of children unsuccessfully treated for malnutrition (in Yemen). DFID provided a public amendment and statement explaining these changes.

There have been inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the results measurement for some nutrition programmes. The nutrition portfolio has faced challenges in classifying intensity

Generating an accurate picture of reach within a country is important, since increasing the population coverage of nutrition services is a critical element of the nutrition strategy and theory of change. As noted in the Lancet Series and DFID’s methodology note, population coverage of 90% is required for the nutrition-specific package to have a significant impact on stunting and wasting.

The nutrition portfolio’s results reporting is more sophisticated than before, but the downward revision of the global figure highlights the difficulties with the methodology. ICAI found that reporting against the nutrition results framework has been a complex and resource-intensive exercise for staff. Not all programmes were previously monitoring reach in the same way, and it has taken time to align and improve existing processes. Errors and inconsistencies have arisen in some instances. From the 12 programmes where we reviewed their accuracy in depth, ICAI found the results for one programme to be “very reliable”, seven “reliable” and four “less than reliable”. This assessment was based upon a review of the calculation methodologies employed (including whether actual or estimated results figures were used), and the approach to avoiding double-counting, as well as comparisons with other programme monitoring data and discussions with responsible officers.

Reliance on poor-quality programming and especially national data systems has been one of the most significant challenges for DFID in accurately calculating its nutrition reach (which is why the department has been working to improve systems in some countries). This weakness is recognised in the methodology note, and ICAI found several examples of this in practice. In some countries, a lack of robust monitoring data means that nutrition results are estimated based on local population data (in turn derived from national census data of variable quality). Results in Tanzania had to be revised several times – the country’s nutrition programme did not have a robust methodology in place for measuring the reach of a mass media educational campaign. It was concluded that the reported results were too conservative. One inaccuracy observed by ICAI related to a simple human error made in counting results.

Other problems related to inconsistency in the approaches to aggregating nutrition results across countries and avoiding double-counting. The country team in Ethiopia disaggregates programme results by region, and then adjusts the results based upon the estimated geographical overlap in each region. This is more sophisticated than approaches observed in some other country teams, which apply a more arbitrary percentage reduction at country level. ICAI found that country teams have developed their own data sheet for aggregating country results, which is contributing to inconsistency as well as duplication of effort. Errors and inconsistencies increase the requirement for quality assurance and the burden on the department’s statistical cadre.

Recognising these challenges, the statistical cadre and central nutrition team have provided an important quality assurance function at the global level to supplement the quality assurance conducted by programme teams as an ongoing part of programme monitoring. However, they have not always immediately spotted errors (for example in the case of the major revision noted above) for a range of reasons. Ensuring regular, scheduled quality assurance of the results is an important way to spot and address errors. ICAI also found that statistical capacity has not always been sufficient within country teams. Quantitative skills and capacity are required not only to help avoid double-counting, but also to provide longer-term support for strengthening monitoring and data systems to measure coverage more accurately. For example, DFID said that the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) office now has a new statistics officer who is helping to improve monitoring systems, calculate reach more accurately, and classify programme results by their correct intensity.

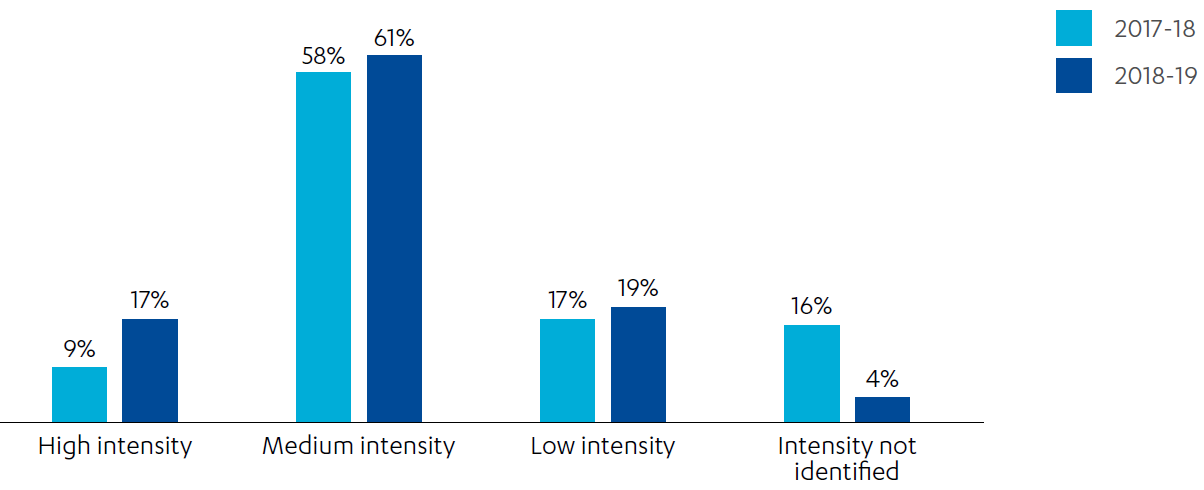

ICAI also found evidence that DFID has been underestimating its high-intensity reach. Most of the nutrition results (over 60%) are classified as medium-intensity. DFID improved in classifying the intensity of its results in 2019, with only 3.5% of results not classified (compared with 16.4% in 2018). However, country teams have faced challenges in identifying high-intensity reach. In most cases, this is because programme or country management information systems are not yet sophisticated enough to record whether individuals have received services from different ministries. Ethiopia has not reported high-intensity reach at all, despite its Accelerating Reductions in Undernutrition programme (with 4.3 million people reached) providing a package of interventions across a range of sectors. DFID Zambia, in collaboration with USAID and the Zambian government, planned to introduce at least two indicators to measure the convergence of services at the household and health facility levels through surveys.

The other main area of inconsistency across country teams has been in the treatment of nutrition-sensitive programmes. The country team in Zambia classifies its nutrition-sensitive programmes as low-intensity, due to their lack of a targeted approach. However, two of these programmes, covering social protection and WASH, also had no nutrition objectives or clear indicators at the outcome and impact levels. The impact on nutrition was, however, assessed by the evaluations for these programmes. By contrast, the Ethiopia country team decided not to include any low-intensity results, in part due to the risk of double-counting. In the case of WASH, Ethiopia’s programme was excluded noting that its impact on nutrition has not been measured and that the evidence for a direct impact of WASH on nutrition outcomes is mixed. ICAI found that DFID’s methodology note lacks sufficient detail on which activities can be considered nutrition-sensitive and on relevant indicators.

DFID’s methodology note also encourages country teams to provide brief narrative reports outlining what is being done to strengthen national policies, the coverage and effectiveness of nutrition interventions, and monitoring systems. However, ICAI found that these narratives and associated lessons learnt have not been systematically collected by country teams or shared internally or externally. As a result of this and data limitations, ICAI found that the portfolio’s nutrition results are not consistently used to improve programme implementation. For example, there is scope to link the learning from measuring high-intensity reach with planning for improving the convergence of programmes on vulnerable populations and improving national data systems. This could in turn be linked to performance indicators to measure and report better on the impact of UK aid on systems strengthening.

More than half of the nutrition programmes assessed by ICAI have achieved their immediate nutrition objectives

Since the 2014 ICAI review, DFID made significant progress in implementing its nutrition programmes, and overall they are judged to have been effective in delivering their immediate objectives.

Of the 20 nutrition programmes reviewed by ICAI (see Annex 1), more than half (13) have met most (at least three quarters) of their output targets. Five programmes met more than a quarter but less than three quarters of their output targets. Two programmes had not met any output targets relevant to nutrition.

- Eight programmes showed strong performance on delivering nutrition-specific outputs. These include the provision of vitamin A, iron and folic acid supplements, counselling on child feeding and maternal nutrition (and associated training for health workers), and the management of moderate and severe acute malnutrition. For example, between 2011 and 2017, the Working to Improve Nutrition in Northern Nigeria programme reached 10,086,704 children under five with vitamin A supplementation, 7,469,116 pregnant women with iron supplementation and 814,437 pregnant women and mothers of young children with feeding counselling.

- At least six programmes, including several in Ethiopia and Zambia, delivered strongly on outputs despite operating during humanitarian crises caused by droughts, floods and/or conflict. For example, between 2012 and 2016, over 200,000 children with severe acute malnutrition were treated at community sites in Northern Nigeria. Conversely, three programmes struggled in humanitarian contexts, due to challenges with partner coordination and government delivery capacity, as well as reaching the poorest regions. For the Productive Safety Net Programme 4 in Ethiopia, this resulted in delays in the distribution of food transfers.

- Six programmes demonstrated positive progress in engaging with government, and delivering outputs related to strengthening government leadership, coordination and delivery capacity. The Power of Nutrition centrally managed programme also contributed positively to supporting government engagement, although it did not meet its targets to leverage additional funds for nutrition from other donors, philanthropists, the private sector and high-net-worth individuals. DFID reported that the programme has since been working with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to adjust its investment model and increase private sector and philanthropic contributions.

Progress on delivering nutrition outcomes is more mixed, although positive overall. 11 of the 16 programmes measuring outcomes relevant to nutrition have met most (at least three quarters) of their outcome targets. Two programmes have met some (more than a quarter but less than three quarters) of their outcome targets, and three programmes have met less than a quarter of their targets.

- Six programmes reported positive outcomes highly relevant to nutrition, including improved breastfeeding and complementary feeding knowledge and practices, an increase in dietary diversity and meal frequency among women and children, and reductions in severe acute malnutrition. Programmes that provided more comprehensive packages of nutrition-specific support tended to deliver more positive nutrition outcomes. Citizens living in Mongu District, Zambia explained:

“Way back we never used to know about feeding and what the baby requires. We didn’t know that we can eat goat milk or even put meat or pumpkin leaves in the porridge but because of this programme we have come to learn about it. We just used to give them soup and plain porridge but that’s no longer the case.”

Focus group participant, Mongu District, Zambia

- Four further programmes reported successfully increasing population access to nutrition services – including feeding counselling and vitamin A supplementation. Although these programmes assessed their impact on nutrition (through measures of stunting), they lacked any further outcome indicators beyond coverage (for example influencing feeding practices or diets). Without this, it is difficult to judge the quality of support received and their specific contribution towards reductions in undernutrition.

- Through advocacy and technical assistance, four country-based and one centrally managed programme (see Box 7) reported successfully strengthening the capacity of government systems for planning, coordinating and delivering nutrition services. For example, and despite initial delays in procuring technical assistance, Building Resilience in Ethiopia reported progress in supporting the government to lead and manage humanitarian response services better. This includes building early warning systems (‘hot spot mapping’) that can anticipate local droughts and crop failure, support early intervention and help avert larger nutrition crises.

Box 7: Achievements of the Technical Assistance for Nutrition programme

The Technical Assistance for Nutrition programme funds technical assistance and knowledge management for the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement through Nutrition International, Maximising the Quality of Scaling Up Nutrition Plus (MQSUN+) and the Emergency Nutrition Network, as well as providing direct support for the SUN Movement Secretariat. The programme has also provided technical assistance capacity to country teams. Overall, the programme has helped to strengthen governance, capacity and knowledge management for nutrition at global and country levels. Key contributions have included ensuring that evidence-based, costed country action plans are in place, for example in Somalia, Afghanistan and Ethiopia, and developing national nutrition policies and programmes for Madagascar, Kenya and Uganda, behind which donor investments can then align. In Ethiopia, the implementation of the Seqota Declaration, a multi-sector plan to eradicate the underlying causes of chronic undernutrition and end child stunting by 2030, has been supported by the programme. Technical Assistance for Nutrition has also helped develop budget tracking and other systems to review progress. Globally, the programme has effectively built the capacity of country teams to deliver on their nutrition and humanitarian goals, through the MQSUN+ mechanism and the production of various knowledge outputs and guidance (including in areas relating to equity). Its success has been aided by its flexible and demand-driven approach, and range of expert and nimble partners able to operate in this way, as well as proactive engagement from staff.

Based upon evidence of outputs and outcomes, the nutrition-sensitive components of some multi-sector programmes have sometimes been less effective. The small number of nutrition programmes with integrated WASH components have had less success in delivering behaviour change in hand washing and using clean sources of drinking water. The Productive Safety Net Programme in Ethiopia, a social protection programme that integrates nutrition-sensitive behaviour change activities and small-scale food production (alongside its general aims of reducing poverty), has faced challenges including the low uptake of nutrition counselling (which involves providing advice on feeding and hygiene practices). This suggests that a more intensive approach might be needed for these activities, either within multi-sector nutrition programmes or through convergence with other programmes.

Three programmes have not met any outcome targets relevant to nutrition. The Hunger Safety Net Programme in Kenya provides an example of some of the typical challenges faced.

Box 8: Challenges faced by the Kenya Hunger Safety Net Programme

The Hunger Safety Net Programme (2013-19) in Kenya was classified as a low-intensity, nutrition-sensitive social protection programme. While it broadly fulfilled its function as a safety net for the extreme poor, DFID reported that the programme fell slightly short of its outcome targets, including for the quantity and quality of food consumption. This reflects failures in delivering cash payments to some users, linked to weak financial infrastructure within target districts and late government payments. While the programme successfully developed a model social safety net for Kenya, scalable to support early crisis response, and DFID influenced the government’s social protection policy, systems were not strengthened to the extent required to ensure full coverage and sustainability. This is attributed to overambitious targets and external factors beyond the programme’s control (including Kenya’s existing budget deficit). DFID responded by increasing the flexibility of its own financial contributions and extending the programme into a third and final phase.

For four programmes, outcomes relating to undernutrition or its underlying causes were not being monitored sufficiently. Logframes for some nutrition-sensitive programmes, including in private sector development and social protection, lacked the most relevant outcome indicators. One WASH programme was focused on monitoring outputs rather than outcomes. Two programmes were not monitoring nutrition outcomes despite having relevant nutrition indicators in their logframes. This was due to a lack of relevant data collection methods and targets. DFID said that improvements were planned.

Where relevant nutrition outcomes are being monitored, ICAI finds that the nutrition portfolio has often collected high-quality and globally recognised performance data, such as indicators of dietary diversity and minimum acceptable diets, working with implementing partners such as UNICEF. However, overall, ICAI found room for improvement in the monitoring of outcomes among those programmes contributing to nutrition results. This was particularly the case for nutrition-sensitive programmes. Because of this, it is not always straightforward to judge their effectiveness (and “what works”), and some programmes needed a sharper focus on nutrition. Now a more comprehensive results framework is being developed, linked to an overarching ‘nutrition theory of change’. Examples of relevant intermediate outcomes and impacts are also included within DFID’s recently finalised value for money guidance. Programmes need to draw on this to help improve the consistency of their outcome measurement, including underlying causes.

Factors commonly influencing the effectiveness of the nutrition programmes include effective political leadership and coordination mechanisms, national and community-level delivery capacity, and systems for data and learning. External shocks are a major constraint

We identified a range of enabling factors that influence the effectiveness of nutrition programming from the literature, and through interviews with external experts (see Figure 6). We then applied this framework to help identify the key success factors influencing the portfolio’s nutrition programmes.

Figure 6: Enabling factors that influence the effectiveness of nutrition programming

Strengthening political and technical coordination (across partners and government) was the most prevalent enabling factor, for eight out of 12 programmes. In countries such as Bangladesh, the DRC and Zambia, this was important for achieving consistency of nutrition service delivery, comprehensive population coverage and/or co-located services. For around one third of programmes, ineffective coordination mechanisms were a major constraint.

Securing political leadership and commitment was a key enabling factor for seven out of 12 programmes. A strong example of this is found within the Tackling Maternal and Child Undernutrition Programme in Zambia, where strong political commitment was in place at the national, district and village levels (including down to chiefs and village heads). For some other programmes, a combination of weak government and fiscal crises – leading for example to non-payment of health worker salaries and low motivation – presented significant programme constraints on effectiveness.

Five out of 12 programmes benefited from strengthening national and local capacity to deliver nutrition services. Working to Improve Nutrition in Northern Nigeria and programmes in Zambia provided training and technical support to community health workers and other volunteers (for example in growth monitoring, and the promotion of infant and young child feeding practices), which improved the quality of services. Despite these efforts, weaknesses in delivery capacity, including underfunded and overburdened health care systems and community volunteering structures, were still major constraining factors for some programmes, including in Nigeria and Zambia as well as Ethiopia.

External experts highlighted DFID’s evaluation and learning systems as a further success factor. ICAI found that most of the portfolio’s nutrition programmes demonstrated flexibility in response to changes in their context or evaluation evidence. Examples of adaptive management included flexible and rapid response to new humanitarian emergencies and crises (for example treating cases of acute malnutrition during the recent flooding in Zambia’s Northern Province, and in response to COVID-19 in Ethiopia), cost extensions to support the scale-up of services, and the incorporation of nutrition-sensitive components to help increase impact. Conversely, one third of programmes reported inadequate monitoring and evaluation as a constraining factor – including limited data systems to help identify, track and reach target groups, and to supply data on undernutrition.

Most constraining factors, however, related to external threats, including protracted environment and climate-related shocks, conflict and extreme poverty (reported by 11 out of 12 programmes). Shocks exacerbate periodic outbreaks of acute malnutrition, make access to the most vulnerable groups difficult (including when communities are displaced), and divert resources from longer-term activities. For example, the 2016 drought in Ethiopia, resulting from the El Niño weather effect, placed delivery pressures on most of the nutrition programmes reviewed. The Somalia country office flagged that working within an environment where both famine risk and ongoing conflict are daily challenges has placed severe pressures on its nutrition programmes.

Successful DFID nutrition programmes worked to mitigate these risks. ICAI found that DFID’s nutrition team played an important role in supporting country offices to improve their effectiveness, for example through sharing evidence of “what works”, as well as through the centrally managed Technical Assistance for Nutrition programme. The central-country team relationship is particularly strong in this area of programming. However, the nutrition team has had limited capacity, and inevitably it has not been possible to provide sufficient support across all areas.

Summary