DFID’s approach to disability in development

Executive Summary

Around one in six people in developing countries live with a disability. As a group, they tend to be poorer, and suffer more discrimination, exclusion and violence than the rest of the population. Without measures to include people with disability in development, the ambition of the Sustainable Development Goals to ‘leave no one behind’ will not be attained. This insight was at the core of an April 2014 report on disability and development by the International Development Committee, which urged DFID to become more ambitious in its approach to disability inclusion in its aid programming.

The UK government was a significant member of the international coalition that succeeded in including disability as a central concern of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. But DFID has been slower in systematically including the concerns and challenges facing people living with disability in its own development and humanitarian programming. The department created a disability framework in 2014, and renewed it in 2015, but a major change of emphasis only came in late 2016, when the secretary of state announced an aim to establish DFID as “the global leader in this neglected and under prioritised area”.

Since then, DFID has moved more forcefully to mainstream disability inclusion across the department, and has called a global disability summit for July 2018. In view of this increased attention to disability, ICAI decided to undertake a rapid review of DFID’s progress, and shed light on potential improvements DFID can pursue as this portfolio develops.

An ICAI rapid review is a short, real-time review of an emerging issue or area of UK aid spending that is of particular interest to the UK Parliament and public. We examine the evidence to date and comment on issues of concern, but do not draw final conclusions on performance or impact. Rapid reviews are therefore not scored.

Relevance: Has DFID developed an appropriate approach to disability and development?

DFID has made a useful start, and is scaling up activities ahead of the global disability summit, but a step change is needed to mainstream disability across the department

Disability is not the same as impairment. A disability arises only if individuals with impairments are prevented from participating in society on an equal basis with others. A strategy for disability inclusion is therefore about removing the barriers that prevent participation. In 2009, the UK ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, committing to ensure that its development programmes would be inclusive of people with disabilities.

DFID’s 2014 and 2015 disability frameworks made a start at mainstreaming disability inclusion, but anticipated that the process would take time. There were commitments and activities from the centrally located disability team and sectoral policy teams, but there were no timelines, no indicators, no financial targets and no commitments from country offices.

From late 2016 onwards, DFID senior management has provided clear leadership. A 2017-18 disability inclusion action plan set out appropriately ambitious outputs and outcomes, but its brevity (a one-page diagram) precluded guidance on outputs, targets or milestones. There is no dedicated funding to cover the start-up costs of mainstreaming – as Australia’s department responsible for development has for disability, and as DFID had for disaster resilience.

DFID has put a range of mandatory requirements into its programme management processes. In particular, staff are required to mark all programmes as to whether they target disability. They must also consider disability in all new business cases and take into account the ‘leave no one behind’ agenda in programme annual reviews. These requirements have caused DFID departments to consider disability inclusion. But in practice they have been too broad, with insufficient monitoring arrangements, to ensure that programmes have practical elements relevant to disability inclusion and that these elements are implemented in the field. By February 2018, only 22% of DFID’s 1,161 programmes were provisionally marked as containing deliberate activities to support disability inclusion and only six programmes as having disability inclusion as the primary objective. This demonstrates that DFID is starting from a low base and has a considerable distance to go to meet the secretary of state’s ambition to put disability inclusion at the heart of everything DFID does.

Disability inclusion requires specialist skills. The experience of comparable donors with similarly high levels of ambition to mainstream disability suggests that DFID should invest in more staff with technical expertise and experience. The disability team has done well on drawing on external advice, and the department’s network of social development advisers are knowledgeable about inclusion in general, but DFID would benefit from stronger in-house expertise on disability mainstreaming.

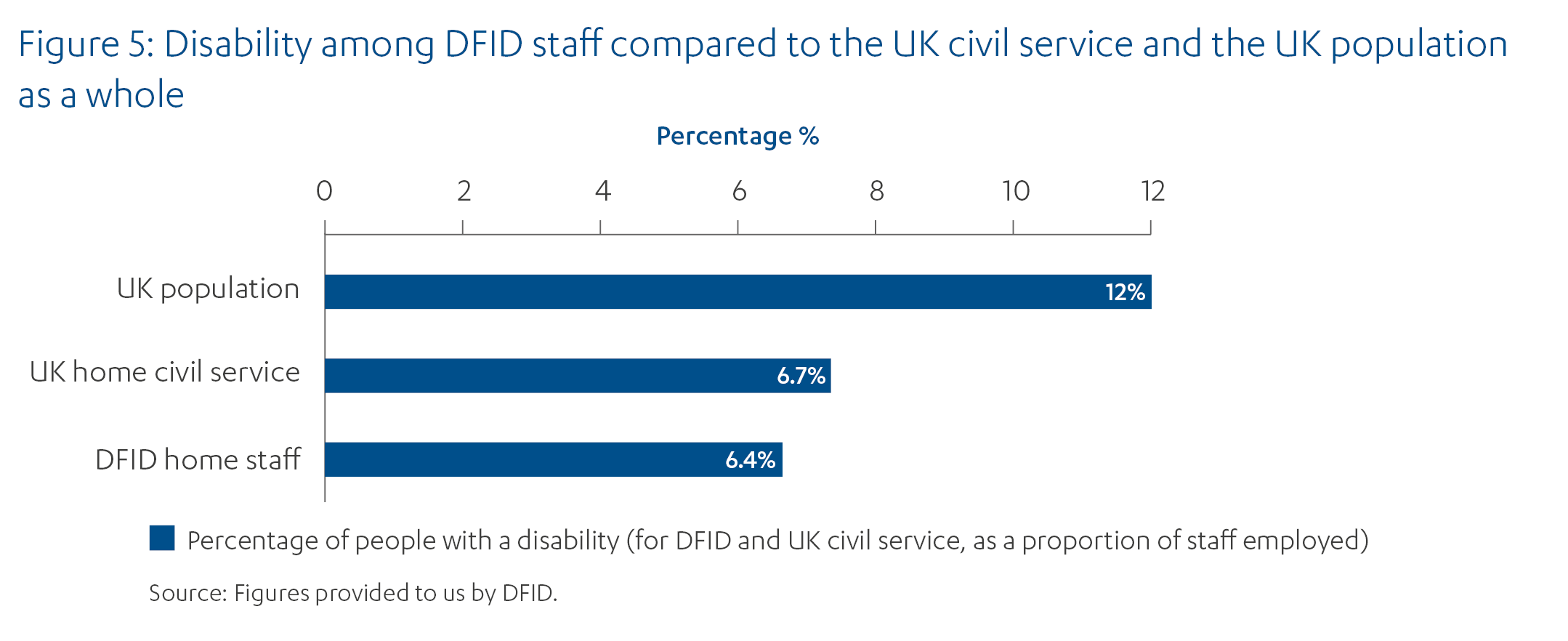

Only 6.4% of DFID home civil service staff, and 1.4% of locally engaged staff in country offices, self-identify as having a disability. This compares with 6.7% in the UK home civil service as a whole – which has an objective to be the most inclusive employer in the UK by 2020. DFID’s influence as a global advocate for disability inclusion would be strengthened if it is seen to practise what it advocates. Employing staff with disabilities raises the awareness and confidence of their colleagues to work to include disability in aid programmes. It signals a shift from perceiving people with disabilities as vulnerable individuals to perceiving them as colleagues and professionals whose insights and contributions include but are by no means restricted to disability issues.

While the disability mainstreaming process only started in earnest in late 2016, and could not be expected to be concluded at this stage, we find that more detailed planning, stronger disability expertise and faster implementation are now needed for DFID to achieve its mainstreaming ambition.

DFID’s disability-targeted programming in key sectors is too modest in scale and reach to be likely to deliver transformational results

DFID drafted an overall theory of change for disability inclusion in 2017, which identifies some of the barriers to disability inclusion and some steps that different actors might take to remove those barriers. However, this theory of change has not been used – by country offices or centrally – to guide the planning of disability inclusion activities. The one-page action plan lists some important steps towards disability inclusion (such as inclusive education systems and economic opportunities) and identifies some key actors. As part of the preparations for the global disability summit, there is now an increased focus on the private sector, and DFID country offices are more active in their efforts to influence governments in partner countries – but both start from a low base. DFID has developed appropriate value for money principles for disability, ensuring that value for money is about how best to include people with disabilities, not whether they should be included, but practice is not yet consistent.

DFID rightly emphasises the importance of disabled people’s organisations, whose advocacy activities have contributed to governments making significant policy changes on disability inclusion. But DFID’s main mechanism of support, the Disability Rights Fund, operates in only eight of DFID’s 32-plus priority countries. We did not find that country office engagement with local disabled people’s organisations would usually extend to consultation on the design and implementation of programmes.

We examined DFID’s programming in five sectors. Of these, the education sector was most advanced, and the new 2018 education policy explicitly prioritises disability inclusion. Experience in the humanitarian field was more mixed. But in the last three areas identified in the 2015 disability framework as requiring more work across the department – economic empowerment, stigma and discrimination, and mental health and intellectual disabilities – DFID’s range and scale of activities were too modest to deliver the sort of transformational results anticipated in the framework and action plan.

DFID is a leader in promoting disability in the global development agenda

DFID is widely recognised as one of the main actors promoting disability in the global development agenda. Despite the limited resources spent on international influencing, DFID has made successful use of focused campaigns with clear objectives and good coordination with like-minded partners such as the International Disability Alliance of disabled people’s organisations. In addition to helping ensure that disability was included as a central concern in the Sustainable Development Goals, DFID was central to the establishment of the inter-agency Global Action on Disability (GLAD) network and has been at the forefront of efforts to create an international consensus on the collection and use of disaggregated data on disability.

DFID is working effectively with multilateral agencies. Considering the department’s role as a major multilateral donor, its efforts have the potential to significantly influence how multilaterals approach disability inclusion globally. DFID has influenced the World Bank’s disability inclusion and accessibility framework, and included disability in its Payment by Results approach to 11 agencies within the United Nations system. DFID could do more through its executive directors on the boards of the World Bank and other organisations: if projects were rejected due to lack of disability inclusion, this would prompt action.

A global disability summit in July 2018, to be hosted in London with the government of Kenya and the International Disability Alliance, is an opportunity to push for a step change in global disability inclusion efforts. Positive outcomes are expected in terms of awareness and commitments to action by donors, multilaterals, the private sector, developing country governments and civil society.

Learning: How well is DFID identifying and filling knowledge and data gaps on disability and development?

DFID has previously funded little research on disability, but is now planning a substantial Disability Inclusive Development programme, modelled on the What Works programme on violence against women and girls, which is delivering valuable results. Given the paucity of knowledge on what works for disability inclusion, investing in evidence and research is appropriate and underscores DFID’s willingness to take leadership of the agenda.

For research to effectively feed into programming choices, it is necessary to have a research strategy that identifies and addresses the most important evidence gaps. DFID is beginning to develop such a strategy. It is important that it is completed in time to influence the design phase of the planned investment in research and evidence gathering. It is not clear how far people with disabilities will be involved in steering DFID’s disability research. This is important, given the principle of participation in the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

There is no plan to mainstream disability into broader research, despite the positive experience of an earlier cross-cutting disability research programme. Such cross-cutting research is particularly relevant because many people with disabilities also encounter other forms of discrimination and exclusion due to their gender, race, age, sexual orientation, religion or other characteristics.

DFID staff have limited guidance on how to address disability in programming. A helpdesk is to be introduced in 2018; experience elsewhere suggests that this is likely to be useful. The proposed Disability Inclusive Development programme will promote research uptake, but could be complemented by a structured exchange of learning between country offices on the more practical aspects of mainstreaming disability, a community of practice of staff working on disability and a plan for evaluations.

DFID is also addressing the data gap created by the lack of robust and consistent methods for counting the number of people with disabilities. DFID is working closely with Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and other international actors towards reaching international agreement on using the so-called Washington Group Questions to collect this data. DFID has linked some of its core funding of UN agencies to the disaggregation of key results by disability.

Conclusions and recommendations

DFID has taken a leadership role internationally, and has rightly focused investment on research and on filling a key data gap. But its own mainstreaming efforts have been proceeding slowly until recently. Although activities to integrate disability into programming have been scaled up considerably ahead of the global disability summit, DFID does not yet have a thorough plan to mainstream disability inclusion across the department in a manner consistent with its stated ambition.

Recommendation 1

DFID should adopt a more visible and systematic plan for mainstreaming disability inclusion. The plan should be time-bound with commitments and actions at the level of programming, human resourcing, learning, and organisational culture.

Recommendation 2

DFID should increase the representation of staff with disabilities at all levels of the department, and increase the number of staff with significant previous experience in working on disability inclusion.

Recommendation 3

DFID country offices should develop theories of change for disability inclusion in their countries. These should propose a strategy for the country office, with a particular focus on influencing and working with national governments.

Recommendation 4

DFID should engage with disabled people’s organisations on country-level disability inclusion strategies, advocacy towards partner governments, capacity building, and the design of programmes, including research programmes.

Recommendation 5

In order to deliver its existing policy commitments, DFID should increase its programming on (i) tackling stigma and discrimination, including within the private sector, and (ii) inclusion of people with psychosocial disabilities and people with intellectual disabilities, noting that these are two different groups who face different sets of challenges.

Recommendation 6

DFID should create a systematic learning programme, and a community of practice, on the experience of mainstreaming disability into DFID programmes.

Introduction

Any attempt to end extreme poverty in the world must tackle disability: 18% – more than one in six – of adults in developing countries are estimated to have a disability. People with disabilities are poorer than the average, not just in income but also in health, education, employment and social inclusion. Furthermore, there is evidence that this gap widens as developing countries become richer: “The development process is not inclusive by default.”

A report by the International Development Committee (IDC) on disability and development, published in April 2014, found that DFID was not sufficiently ambitious in its work on disability inclusion, given the UK government’s considerable international efforts to promote a ‘leave no one behind’ agenda for the Sustainable Development Goals. The IDC report noted that if “DFID is serious that no one should be left behind in future work, a strong commitment to disability will be essential”. DFID responded with a disability framework in late 2014, and began to put in place staff and structures. The process was accelerated after a December 2016 speech by the then secretary of state, given on the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, which promised to “make disability a global priority”. Ministerial commitment to the issue has continued under the current secretary of state, Penny Mordaunt, who in a November 2017 speech promised to put disability at the “heart of everything” DFID does.

This is a moment of major attention to disability, both within DFID and internationally. The global disability summit, called by the secretary of state for July 2018, is an opportunity to set in motion a step change in global – as well as the UK’s own – efforts to include disability as a central concern across development and humanitarian assistance programming. It is therefore an appropriate time for ICAI to take stock of DFID’s activities in this area. We have conducted a rapid review, reflecting the fact that this is a relatively recent priority for DFID. The 2014 disability framework stimulated only piecemeal action: visible DFID investments, both in staffing and in programming, have mainly taken place after 2016, with a scale-up of efforts in recent months, in preparation for the global disability summit. It would therefore be premature to judge the effectiveness of this work. Instead, a rapid and real-time review provides DFID with an early assessment of the suitability of its approach to disability in development assistance. By assessing what is working and what could be done better in this emerging area, we can help shape the direction of this approach.

Box 1: What is an ICAI rapid review?

ICAI rapid reviews are short reviews carried out in real time to examine an emerging issue or area of UK aid spending. Rapid reviews address areas of interest for the UK Parliament or public, using a flexible methodology. They provide an initial analysis with the aim of influencing programming at an early stage. Rapid reviews comment on early performance and may raise issues or concerns. They are not designed to reach final conclusions on effectiveness or impact, and therefore are not scored.

Other types of ICAI reviews include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries, performance reviews, which assess the quality of delivery of UK aid, and learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming.

Box 2: What is disability?

Disability is not the same as impairment. Many individuals have impairments of some kind – for example physical or intellectual impairments. A disability arises only if individuals with impairments are prevented from participating in society on an equal basis with others. A strategy for disability inclusion is not about tackling the impairment. It is about removing the barriers that prevent participation. This was made clear in DFID’s first disability framework, which quotes the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: “Disability results from the interaction between people with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”

The term psychosocial disability is used to describe people who have or are perceived to have mental health support needs and who have experienced discrimination (including but not limited to infringements on their liberty, autonomy, and effective participation) based on their needs or presumptions about their needs. The term is used to replace phrases such as ‘mentally ill’ and ‘mental illness’, that were in common use previously, but are now seen as derogatory or stigmatising.

The term intellectual disability is used to describe people who have or are perceived to have cognitive/ developmental support needs and who have experienced discrimination (including but not limited to infringements on their liberty, autonomy, and effective participation) based on their needs or presumptions about their needs. It replaces terms such as ‘mentally retarded’ that are now seen as derogatory and stigmatising.

The review assesses DFID’s work on disability in development assistance since the publication of the 2014 IDC report. We look at DFID’s approach to mainstreaming disability across the department as a whole, designing programmes that address barriers to disability inclusion, and building international coalitions. Little is known internationally about the most effective ways to include people with disabilities in development and humanitarian programming. We therefore examine DFID’s activities to build more evidence on what works and to share it both within DFID and outside. Since there is a global shortage of data about disability, we look at DFID’s efforts to promote filling the evidence gaps and data gathering. Table 1 sets out the review questions.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Has DFID developed an appropriate approach to disability and development? | • Does DFID have a suitable approach to mainstreaming disability issues into its programming across the department? • In DFID programmes that include disability-related activities, is the approach likely to deliver meaningful results? • Is DFID adopting a suitable approach to promoting disability in the global development agenda? |

| 2. Learning: How well is DFID identifying and filling knowledge and data gaps on disability and development? | • Does DFID have an appropriate strategy for building its knowledge on what works in improving conditions for people with disabilities? • How well is DFID addressing data gaps on disability in development within its own programming and at national and international levels? • Does DFID have an appropriate strategy for sharing new knowledge and evidence both internally and externally? |

Methodology

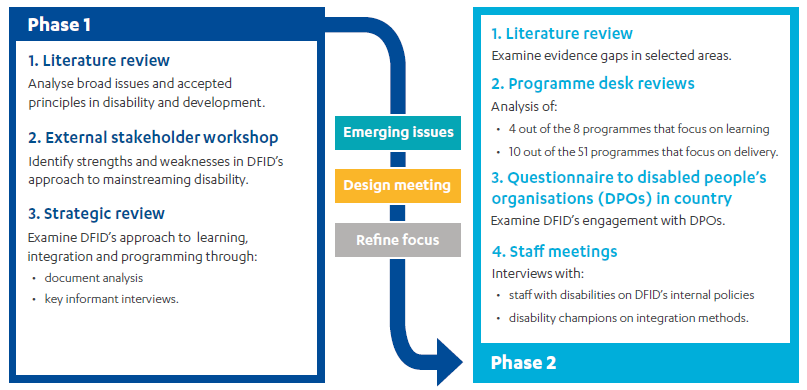

For this rapid review, we adopted an approach over two phases (see Figure 1). In Phase 1, we developed overviews of DFID’s disability inclusion strategy and of the research literature on disability in development. We held a stakeholder workshop with civil society and academics to identify key issues, and conducted initial interviews with DFID staff, outside experts, and other donors.

In Phase 2, we conducted more in-depth investigations into DFID’s disability approach in five sectors: stigma and discrimination, economic empowerment, mental health and intellectual disabilities, humanitarian, and education. In addition, we:

- assessed the extent to which DFID has an overall strategy and theory of change about disability

- conducted a sectoral analysis of DFID’s disability marking of programmes

- compared 2014 country operational plans with 2016 country business plans

- mapped DFID’s employment of people with disabilities against UK civil service commitments to equal opportunities. We were also invited to observe the annual general meeting of the Disability Network of DFID staff with disabilities, and we spoke with members of the Listening Network of DFID staff with mental health challenges.

The approach also included a strong comparative element. We compared DFID’s approach to mainstreaming disability inclusion with that of other bilateral agencies, particularly Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which has had a substantial disability emphasis since 2009. We also used DFID’s own previous mainstreaming experiences as points of comparison, particularly in two areas: disaster resilience and measures to combat violence against women and girls.

Figure 1: The review’s methodology

With the help of the Bond Disability and Development Group, we administered a questionnaire to disabled people’s organisations in countries where DFID has a presence, focusing on DFID’s approach to disability. We received responses from 16 organisations in eight countries. As such, the sample is too small to draw statistically valid conclusions, but it provides useful illustrations. The same is true of the 14 responses to a separate questionnaire sent to the offices of British non-governmental organisations working on disability in nine countries.

In November 2017, 59 of DFID’s 1,145 programmes were registered as spending at least 10% of their budget on disability-related activities. We undertook desk reviews of a sample of 14 of these programmes, looking at four out of the eight programmes focused on research on disability, and ten out of the 51 programmes delivering activities on the ground.

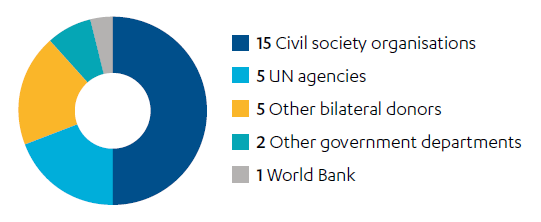

In all, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 53 DFID staff, 15 experts and 31 representatives from other government departments, civil society organisations, other bilateral donors, UN agencies and the World Bank. Annex 3 provides a list of interviewees organised according to institutional affiliation.

Box 3: Limitations to our methodology

While DFID’s disability framework was produced in 2014, the emphasis was greatly increased at the end of 2016. As a result, almost all substantive programmes are relatively recent – five of the 14 programmes in our desk review had not reached their first Annual Review – and so it is too early to assess effectiveness in delivery, let alone impact. Meanwhile, policy and implementation are evolving, with the risk that a finding may refer to a policy now outdated. We have mitigated against this by triangulating documentation with key informant interviews.

Background

If DFID is serious that no one should be left behind in future work, a strong commitment to disability will be essential

Disability and Development, International Development Committee, April 2014.

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities provides the legal framework for disability inclusion in UK aid

In December 2006, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was adopted at the United Nations. The convention describes people with disabilities not as objects of charity and social protection, but as subjects with rights who are active members of society. The UK ratified the convention in June 2009, committing itself to implementing the rights and obligations that it sets out. The convention should therefore be central to any approach to disability.

Box 4: The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The eight principles of the convention are:

- respect for inherent dignity and individual autonomy, including the freedom to make one’s own choices, and independence of people

- non-discrimination

- full and effective participation and inclusion in society

- respect for difference and acceptance of people with disabilities as part of human diversity and humanity

- equality of opportunity

- accessibility

- equality between men and women

- respect for the evolving capacities of children with disabilities, and respect for the right of children with disabilities to preserve their identities.

The implications of these principles are spelt out in the convention. For example, on nondiscrimination, states are required to prohibit discrimination on the basis of disability, and “take all appropriate steps to ensure that reasonable accommodation is provided”. Participation means that states have an obligation to consult people with disabilities through their representative organisations in the development and implementation of legislation and policies. For accessibility, states need to undertake audits in consultation with disabled people’s organisations, and devise and implement plans to remove barriers.

Of particular significance to this review, the convention’s Article 32 requires that states ensure that “international cooperation, including international development programmes, is inclusive of and accessible to persons with disabilities”, and calls for capacity building to enable organisations to do so. Article 11 extends that to situations of risk and humanitarian action.

There has been little progress globally on disability inclusion in development assistance

There is little robust evidence, in any sector, about what works for disability inclusion in aid programming. This was true in a 2011 overview, and surveys since have confirmed the lack of information on disability inclusion in fields as varied as employment, education and violence against women and girls. The World Health Organization and World Bank did not follow up their 2011 World Report on Disability with a research programme, despite the report’s substantial list of research recommendations.

It is widely agreed that a twin track approach is needed. On one track, all development programmes across sectors should be designed in a manner that does not exclude people with disabilities – so that, in other words, they ‘leave no one behind’. On the other track, specific disability-targeted programmes are needed, to support the empowerment of people with disabilities and to remove barriers that prevent their inclusion in society. Yet progress is limited. The experts we interviewed confirm that development actors tend to revert to relatively small, disability-targeted programmes, which have proved easier than incorporating people with disabilities into sectoral programmes.

The first movers on disability inclusion in development assistance have been Finland, Norway, Sweden, Germany and Australia. Australia has had two five-year strategies since 2009, and has played a major advocacy role. Its programme implementation is largely through non-governmental organisations; an evaluation noted that the focus on gender and on disability “has a positive effect on the sector as a whole… [and has] elevated the profile of these themes amongst in-country partner organisations, which could potentially have far-reaching effects”. Elsewhere, however, evaluations have not been encouraging. A 2012 evaluation of NORAD concluded that the “policy and guidelines on mainstreaming disability in Norwegian development initiatives have not translated into concrete action by development partners”. In 2013, Germany adopted an action plan to systematically mainstream disability in development cooperation, but a 2018 evaluation rated its achievements as low to moderate. Likewise, a 2016 evaluation of disability-inclusive development at UNDP noted its failure to live up to its potential role, owing to limited capacity and resources committed.

The Sustainable Development Goals have given a new impetus to disability inclusion

As the 2014 IDC report noted, people with disabilities were left behind in progress towards the Millennium Development Goals. This changed with Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals, partly as a result of a civil society campaign and lobbying by some governments, including the UK. The Agenda says: “As we embark on this great collective journey, we pledge that no one will be left behind… And we endeavour to reach the furthest behind first.”

Box 5: Disability inclusion and the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to

action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy prosperity and peace.

Related to this review

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Agenda 2030 document, which launched the SDGs, makes clear that the needs of people living with disabilities, together with other vulnerable, marginalised and hard-to-reach groups, must be reflected if the ambition to end poverty and ensure prosperity for all is to be attained. Within this ‘leave no one behind’ agenda, we find explicit disability-specific targets for six of the SDGs.

SDG 1, to end poverty in all its forms, notes the need to include people with disability, alongside other marginalised and vulnerable groups, in social protection systems.

SDG 4, to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education, commits to providing equal access to education for the vulnerable, including people with disabilities, and “to build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive”.

SDG 8, on sustainable economic growth and decent work for all, commits to achieving full and productive employment for all, including people with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value.

SDG 10, to reduce inequality within and among countries, highlights the need to empower, and promote the inclusion of, people with disability.

SDG 11, to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable, includes a commitment that safe and affordable transport, as well as green and public spaces, should be available to people with disabilities.

SDG 17, to strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, notes that capacity building to attain the SDGs should include increasing “significantly the availability of high-quality, timely and reliable data disaggregated by income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status, disability, geographic location and other characteristics relevant in national contexts”.

DFID’s attention to disability inclusion began in 2014

Our Prime Minister made a promise… to fulfil the pledge of the Global Goals for Sustainable Development to leave no one behind. Ensuring people with disabilities benefit equitably from international development is central to this promise

Justine Greening, Introduction to the 2015 Disability Framework, DFID, December 2015.

In April 2014, the International Development Committee released a report on Disability and Development, arguing that DFID needed to step up its efforts in this area to correspond with its ambitions for the SDGs. Up until then, disability had not been a prominent topic within DFID. It was not mentioned in the 2013 results framework, and the key staff member working on disability at the time told us that there “was no political appetite”.

The 2014 disability framework committed to “systematically and consistently” include a focus on disability in all of DFID’s work. Despite this commitment, it had a limited ambition. It outlined sectoral work-streams and organisational capacity, and laid out some basic principles of inclusion. But it focused on inspiring, rather than directing, DFID staff to increase their focus on disability.

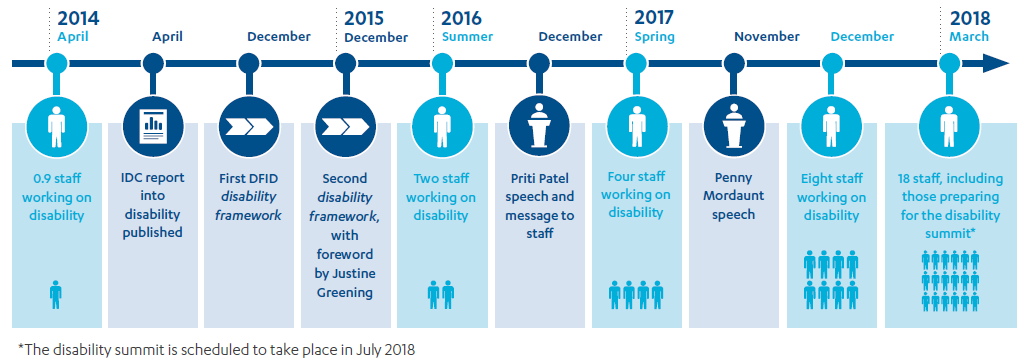

Figure 2: Timeline of DFID and disability

The framework was renewed and expanded in 2015, this time with an introduction by the secretary of state. In addition, a topic guide was produced for staff, though not as official policy. Despite the increased high-level attention to the topic, the November 2015 UK aid strategy did not explicitly mention disability, nor did the September 2016 single departmental plan. The Civil Society Partnership Review (November 2016) and the Research Review (October 2016) made no mention of disability.

The priority given to disability accelerated in late 2016

In December 2016, the secretary of state announced that DFID would aim to lead a “step-change in the world’s efforts to end extreme poverty by pushing disability up the global development agenda” and “establish DFID as the global leader in this neglected and under prioritised area”. Disability inclusion has been a clear priority for DFID ever since, beginning with the Bilateral Development Review of December 2016, which repeated the disability framework’s commitment to systematically and consistently include people living with disabilities in UK aid, and went on to make more specific commitments on education, employment, stigma and discrimination, and data. The Multilateral Development Review (December 2016) had three limited references to disability, the most significant being that “[h]alf of all the agencies reviewed should do more to ensure that disadvantaged social groups, such as people with disabilities, benefit from their work”.

The prioritisation of disability inclusion was confirmed by the incoming secretary of state in November 2017; who promised that DFID “will put disability at the heart of everything that we do”. The December 2017 single departmental plan stated that “DFID is committed to ‘leave no one behind’, including by transforming the lives of people living with disabilities.”

Findings

Relevance: Has DFID developed an appropriate approach to disability and development?

In this sub-section, we examine DFID’s work to mainstream disability across the department. We then turn to individual programmes and ask whether DFID’s approach to programming is likely to lead to disability inclusion. And we assess DFID’s influencing activities to strengthen global efforts to deliver for people with disabilities.

DFID’s disability framework was not enough to get the mainstreaming of disability off the ground

The 2015 disability framework stated an ambition to mainstream disability in policies and programmes and to support disability-targeted programmes. Its actions were focused on centrally located disability and policy teams, but they were not accompanied by commitments from the country offices or multilateral departments that control most programming. Nor did the framework contain targets.

A disability team with (at the time) three staff members was established within the Inclusive Societies Department. The team’s primary role was to support, inspire, catalyse and share good practice, building the confidence of colleagues. It was also to engage in international advocacy, and “take a proactive approach” to disability inclusion in three areas: economic empowerment, mental health and intellectual disabilities, and stigma and discrimination.

In addition, policy teams set out disability-related commitments in a range of sectors: education, data, humanitarian, social protection, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), infrastructure, climate and environment, violence against women and girls, gender, research and evidence, and DFID’s own employment practices. Box 6 sets out the commitments developed by the education policy team as an example.

Box 6: Education commitments in the 2015 disability framework

We will build on progress we have already made on inclusive education by:

- continuing to ensure that all school building directly funded by DFID adheres to our policy on accessible school construction

- working closely with the Global Partnership for education to ensure they include a specific strategy for children with disabilities as criteria for assessing education sector plans and data on disability in their reporting

- working with the UNESCO Institute of Statistics and Education for All Global Monitoring Report to ensure they regularly report on education indicators disaggregated by disability

- collating and disseminating lessons learnt from our disability-focused education programmes such as Zimbabwe, Pakistan and Tanzania from the UK’s Girls’ Education Challenge.

Staff disagree on whether DFID is doing enough

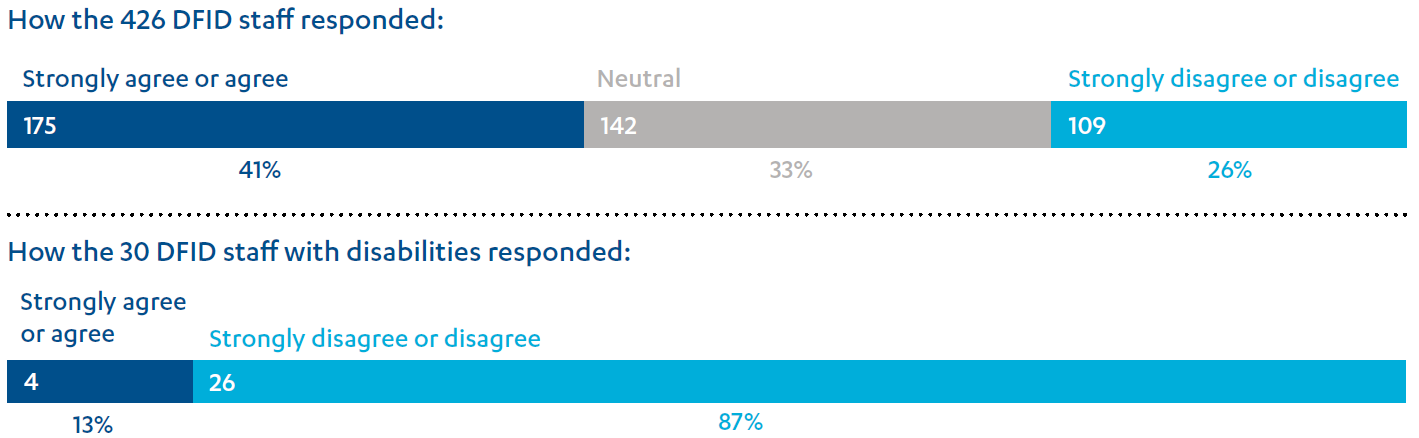

DFID conducted a baseline questionnaire on diversity and inclusion in the summer of 2017, with responses from over 400 staff. As Figure 3 shows, 41% agreed that “DFID is doing enough on disability”, while 26% disagreed. However, among the 30 staff responding who had disabilities themselves, only four (13%) said that DFID was doing enough.

Figure 3: DFID staff views

DFID staff response to the question: “Is DFID doing enough on disability?”

Note: This was the wording of the question, but it is possible that staff interpreted it as applying only to DFID’s employment policy. Source: Diversity and inclusion update (13 December 2017), Annex 2 – Disability in DFID, unpublished.

From late 2016 onwards, disability inclusion became a clearer priority, but DFID’s disability mainstreaming plans are not sufficiently detailed and practical

Following the then secretary of state Priti Patel’s speech in December 2016, DFID produced a onepage disability inclusion action plan. The plan had three desired outcomes, each arrived at through a number of outputs, as summarised in Table 2. It recognised the scale of the challenge of disability mainstreaming in its list of outputs. Its success criteria are reasonable, and accompanied by an explanatory sentence for each outcome. But as a one-page diagram, the action plan provided little detail, and there was no column showing the activities that were intended to deliver the outputs. For example, it had an output of “country office and policy scale-up”, with the explanatory sentence that “secretary of state ambition is rolled out to all country offices and policy teams across DFID”. But there was no information on how this was to be done. Neither the action plan nor the earlier disability framework contained a phased plan with a timeline, targets or milestones for a process of mainstreaming disability across DFID.

Table 2: Summary of outcomes and outputs of the Disability Inclusion Action Plan 2017-18

| Outcome | Outputs |

|---|---|

| Government policies and DFID programmes are inclusive of people with disabilities | • Country office and policy scale-up. • Alliances forged across the government. • Senior leadership, technical cadres and programme managers are inspired and informed. • DFID internal systems report progress. |

| The international system delivers for people with disabilities | • Disaggregated data collected. • Partnerships developed with the private sector to deliver economic opportunities such as through Aid Connect. • Global moments produce concrete deliverables, including Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, leading up to a global summit. • Work to create a global coalition. |

| The government delivers and communicates evidence and impact for people with disabilities | • High-quality communications build support for disability inclusion. • High-quality research delivers robust evidence. • Continue funding disabled people’s organisations and support rights. |

This lack of a phased plan stands in contrast to the recent mainstreaming of resilience against natural disasters that ICAI identified as on the whole successful. For resilience, DFID had an approach paper, providing a list of seven minimum measures for the country offices to implement in order to mainstream resilience into their programming. The country offices were divided into three tiers, with those offices most eager and ready to start the process making up Tier 1, and Tiers 2 and 3 following in succession. There is no equivalent strategy for disability inclusion to reach country offices.

DFID’s approach to mainstreaming its programme on violence against women and girls was also more systematic.27 Within a year of the issue being given priority, DFID produced a theory of change, which became widely referenced and used by DFID staff as a starting point for developing programmes in specific country contexts. The theory of change was followed by a rigorous mapping of DFID programmes. Again, we found no equivalent for disability at this level of acceptance or rigour.

In February 2018, a paper presented to DFID’s departmental board proposed to update DFID’s disability framework to reflect the new and expanded approach, to launch ambitious new commitments, and to form the basis for accountability across DFID in the future. We welcome this.

Introduction of a disability marker showed that two thirds of programmes do not target disability

In April 2017, DFID introduced a disability marker in its management information systems to allow tracking and analysis of the mainstreaming effort. The senior responsible officers for programmes across DFID were asked to mark all their programmes according to the degree to which they included disability objectives. Programmes could be marked as:

- principal, where inclusion and empowerment of people with disabilities is the primary objective

- significant, where the project contains deliberate activities or mechanisms to support the inclusion and empowerment of people with disabilities

- not targeted, where the project does not have a deliberate focus on the inclusion of people with disabilities.

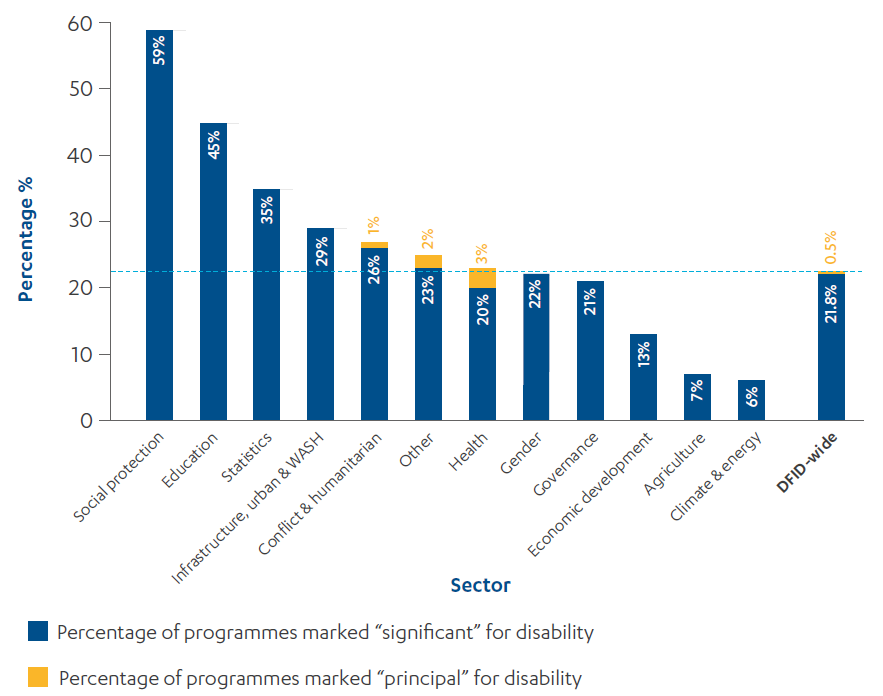

The introduction of the marker has been an important step in enabling DFID to gain a better understanding of current programming on disability inclusion, and has helped to identify both areas of good practice and gaps. Our review of the disability marker found that, as of February 2018, 68% of programmes across DFID did not target disability, 22% of programmes were marked “principal” or “significant”, while the remaining 10% had not been marked one way or another. Only six of a total of 1,161 programmes were marked “principal”.

There was some sectoral variation in the proportion of programmes marked “principal” or “significant”, as Figure 4 shows. Most were in the 21 to 29% range, but education and social protection programmes were notably higher. On the other hand, despite the emphasis given in the 2015 disability framework to economic empowerment, only 13% of economic development programmes and 7% of agriculture programmes were marked “significant”. The lowest percentage was for climate and energy programmes.

The disability marker reveals another dimension in which DFID mainstreaming of disability has some way to go. Box 7 gives some examples of programmes that in February 2018 were marked “not targeted” by their programme manager, but where, in fact, disability inclusion would be relevant. We understand that two of these cases have since been marked as significant.

Figure 4: The focus on disability in DFID’s programmes

Shows proportion of DFID programmes marked as having a “principal” or “significant” focus on disability, by sector

Box 7: Examples of programmes with “not targeted” disability marker

The following programmes are examples of programmes marked “not targeted” by their programme manager in February 2018, but where, in fact, disability inclusion would be relevant:

- UNCD: Investment in the UN Development System to Achieve Agenda 2030 – Agenda 2030 explicitly includes people with disabilities.

- Global Statistics: Monitoring the SDGs – six of which have indicators for disability inclusion.

- DFID Nepal: Market development programme to increase the incomes of poor and disadvantaged people – people with disabilities face particular barriers of access to markets.

- Research: Education technology research to deliver learning outcomes for all children – “all children” includes children with disabilities, with specific interventions needed.

- DFID Sierra Leone: Support for adolescent girls’ empowerment – girls with disabilities face particular discrimination.

Australia has a different method of assessing progress towards mainstreaming

Box 8 describes the method that Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) uses to assess and monitor progress towards mainstreaming disability in its aid programme. By asking whether the programme identifies barriers to inclusion, and whether disabled people’s organisations are involved, it is more clearly addressing mainstreaming than DFID’s disability marker with its focus simply on whether a programme includes activities (of whatever size) to support inclusion.

Box 8: Australia’s method of assessing disability inclusion

The Australian government uses annual Aid Quality Checks to assess the performance of their aid investments of $3 million and above. The checks include two sub-questions on disability inclusion. In 2015, investment managers used them to rate disability inclusion as follows:

- In 46% of programmes: “The investment actively involves disabled people’s organisations in planning, implementation and monitoring and evaluation.”

- In 56% of programmes: “The investment identifies and addresses barriers to inclusion and opportunities for participation for people with disability.”

- These are self-assessments by managers, so the Office of Development Effectiveness was planning an independent review of their accuracy.

Source: 2016 Disability inclusive development: Phase 1 – Strategic evaluation, Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Office of Development Effectiveness, 18 August 2016, unpublished.

Senior management is providing leadership

We found good engagement from DFID senior management. A director-general has chaired monthly meetings on disability. The disability team has presented at senior civil service conferences. The quality assurance unit, which has the power to reject and request resubmission of business cases for large, novel or contentious programmes, has challenged programme proposals for insufficient attention to disability. Key informants told us that this was a step change from the situation before 2017, when senior management had been more cautious in light of competing priorities.

There is no specific finance for the transaction costs of mainstreaming

Mainstreaming has start-up costs. In March 2016, Australia’s official development agency, DFAT, launched a fund to provide technical assistance and funding over four years to assist country programmes to strengthen disability inclusion in their aid investments, build the evidence base, and enhance staff capacity. Likewise, DFID’s resilience programme had a £4.1 million Catalytic Fund to cover such costs, which the ICAI review found mostly effective. DFID has no direct equivalent for disability, although the planned Disability Inclusive Development programme includes dedicated funding for evidence generation, uptake and advice to staff.

DFID has incorporated disability into management systems, but this in itself will not be enough to mainstream disability inclusion

DFID has put a range of mandatory requirements into its programme management processes. In particular, staff are required to give all programmes a disability marker (as noted above), and to consider disability in all new business cases. Heads of department must include disability in their annual departmental reports, and in the return for the Public Sector Equality Duty. We found evidence that these mandatory requirements have prompted departments to consider what actions to take.

The Public Sector Equality Duty requires public bodies to have due regard to the need to eliminate discrimination and to advance equality of opportunity. In March 2017, to take an example from one central team, DFID’s Growth and Resilience Department made an interim assessment of its departmental performance in this regard, noting that: “Analysis and targeting of disability is in very early stages. Better understanding of barriers, evidence of what works and a clearer implementation plan will be important.(…) our strategy on disability needs further development and agreement.”

Business cases are required to “outline any measures to ensure that people with disabilities will be included”, but there is no explicit requirement that programmes have to include such measures. Nor, importantly, is there a requirement to consider how people with disability might be excluded if no action is taken. DFID has just amended the annual review template for its programmes to include for the first time mention of disability. But the requirements are only (i) that monitoring data, evidence and learning should consider the ‘leave no one behind’ agenda, including disability, and disaggregate data as far as possible, and (ii) that the assessment of value for money should include equity and hence disability.

Commitments on disability made in the business case are not always carried through into terms of reference for fund managers and suppliers, or into implementation. We found an example in an education programme in Kenya, where a partner constructing school buildings was not following universal design principles. DFID’s code of conduct for suppliers mentions people with disabilities only in an annex and as one of a number of vulnerable groups whose rights need to be protected. There are no specific expectations to be monitored for compliance – for example on the employment of people with disabilities or the use of universal design principles. A review of USAID projects shows that such requirements make a difference: inclusive programming only happened when the project terms of reference contained specific language requiring the inclusion of people with disabilities throughout all components of the project.

However, our desk review shows a recent increase in disability focus introduced after the business case. In four of the ten programmes we studied, disability activities or indicators that had been absent from the business case were added in the design or tendering phase, or after the latest annual review. This may reflect the increased emphasis within DFID on disability. As an interviewee told us, “the priorities of the programme have evolved, and given the emphasis on equity, the programme will strive to target people with disabilities”.

DFID has too few staff with specific expertise, or long experience of work, on disability inclusion

Disability inclusion is a specialist area. There is a particular legal framework in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, with varied implementation by governments around the world. Engagement with disabled people’s organisations is essential, yet complex, as explored below. There are challenges regarding which organisations representing disabled people and which international non-governmental organisations have relevant experience for different types of programming.

DFID needs to be able to access this experience and expertise. Disability is in the competency framework for DFID social development advisers, and there is a learning programme underway for them, but they have a wide range of responsibilities beyond disability and it was clear from our interviews with social development advisers that knowledge is patchy and they still lack the confidence that comes with experience.

The central disability team in DFID is the obvious place for DFID staff to seek out such knowledge. The team does not currently include any staff who came to DFID with disability inclusion expertise. Interviewees strongly appreciated the support of the DFID disability team, while noting that the current team does not have the length of experience of some of the previous staff. This is an enduring problem: the 2014 IDC report commended “the dedication of DFID’s current disability team”, but was concerned over the lack of full-time disability specialists.

The DFID disability team has wisely drawn on external expertise, from non-governmental organisations, academics and the International Disability Alliance – for example to help draft a guide on value for money, a strategy for influencing the World Bank, and the theory of change for the upcoming global disability summit. However, DFID’s use of outside expertise would be more effective if DFID’s own team included a stronger element of in-house specialist interlocutors.

Other development agencies with a disability focus have recognised this need. The Australian disability team has a mix of public service and technical skills around disability. By contrast, an evaluation of Finnish development cooperation expressed concern about insufficient disability expertise and experience in the Finnish ministry that oversees development cooperation. An evaluation of the German Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development, BMZ, noted that staff resources proved to be inadequate, even though GIZ, the closely associated implementation agency, had a sector team of six disability advisers.

DFID’s commitment to disability inclusion also requires more staff with disabilities

Across DFID in June 2017, 6.4% of home civil service staff and only 1.4% of staff appointed in country had self-identified as having a disability. This compares with 6.7% in the UK home civil service as a whole.

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities requires that states “closely consult with and actively involve” people with disabilities in the “development and implementation of legislation and policies”, and calls on state parties to “employ persons with disabilities in the public sector”. The DFID disability framework acknowledges the demand of many disabled people’s organisations: “Nothing about us, without us”. The business case for the planned Disability Inclusive Development programme notes: “Best practices for disability inclusion in development and humanitarian work include actively and meaningfully involving people with disability in the process of forming policies and programmes”. DFID’s plausibility as a global advocate for disability inclusion will be strengthened to the extent that it is seen to practise what it advocates.

Research and our own interviews highlight that employing more staff with disabilities will likely improve programming by increasing the pool of competent people and having a positive impact on the attitudes of other DFID staff. In two country offices, we heard that the presence of a staff member with disabilities had raised both the awareness and the confidence of their colleagues in working on disability. Such a shift in perception is important. It shows non-disabled people that people with disabilities are not just vulnerable and dependent, but colleagues who contribute their subject matter expertise (which may or may not be disability-specific).

The UK civil service has a goal to be the most inclusive employer in the UK by 2020. We were told that DFID is preparing a new Diversity and Inclusion Strategy with the aim of supporting this goal and turning DFID into one of the most diverse and inclusive places to work across the civil service. Publishing this strategy, with a timeline and an implementation plan, would be an essential part of DFID’s commitment to disability inclusion.

To be the most inclusive employer, a culture change is needed

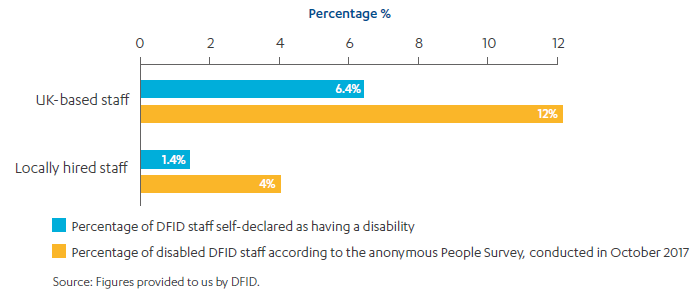

To be an inclusive employer, it is key to provide a safe environment where staff with disabilities can raise issues and be treated with respect. We found evidence of a shortfall of trust among staff with disabilities towards DFID managers. In a baseline diversity and inclusion questionnaire, conducted in 2017, some staff told DFID that they do not feel comfortable discussing their disability with their line manager. This was reinforced by views we heard from the three networks in DFID related to disabilities: the DFID Disability Network of staff with disabilities, the network of parents of children with disabilities, and the Listening Network, which is concerned with psychosocial disabilities. People with disabilities are often unwilling to declare a disability for fear of discrimination, and there is statistical evidence that this is true within DFID: the anonymous People Survey, conducted in October 2017, recorded 12% of UK-based staff and 4% of locally hired staff as disabled – considerably higher than the 6.4% and 1.4% that have self-declared.

Figure 5: Disability among DFID staff compared to the UK civil service and the UK population as a whole

Figure 6: Disability among DFID staff: Comparison between UK-based and locally hired staff and between staff who self-declare their disability and the results of an anonymous survey

The three networks of staff concerned with disabilities were consulted by DFID in 2017 and asked how DFID could improve its organisational culture to make it more diverse and inclusive. They called for changes in the department’s organisational culture. These included shifting the mindset towards what people with disabilities can contribute (and away from only looking at their needs), recognising the individuality of people with disabilities and facilitating a “culture change where disability is no longer a ‘hidden’ topic”. One area where DFID is succeeding in changing the culture is in attitudes towards staff with mental health challenges. Box 9 describes the Listening Network.

Box 9: The Listening Network

A Listening Network in DFID has created a safe space for staff to speak confidentially about any issues they are dealing with, including psychosocial disabilities. It was set up on the initiative of five staff members, with the support of their director. To date, 70 staff are volunteer listeners, and 46 staff are mental health first-aiders, trained to support each other in dealing with stress, anxiety, depression and other mental health conditions. As well as offering confidential support, the network also shares personal stories and blogs. These help others realise that they are not alone, giving them confidence to share their own experiences and reduce the stigma of talking about mental health issues. In the two years since the launch of the network, volunteers have supported over 50 colleagues.

The current approach to mainstreaming is too cautious to match DFID’s ambition

We conclude on mainstreaming that to achieve the secretary of state’s ambition to place disability at the heart of all DFID activity would involve a step change across the department – in staff, skills, systems and processes and in organisational culture. That in turn would require DFID to put in place an explicit and structured plan with timelines, backed with technical expertise and finance for transactions costs.

DFID does not have an agreed global theory of change to guide programming

DFID lacks a fully articulated theory of change about how disability inclusion might come about in the world, and thus of what DFID’s role might be in encouraging positive change. Staff preparing for the new research programme on disability did produce in 2017 a diagram of a meta-theory of change, outlining what might be needed globally to achieve disability inclusion. It helpfully starts by listing barriers to inclusion – legislative, institutional, attitudinal, social and environmental – and concludes with people with disabilities being fully included within society. However, it has not been debated externally, or agreed internally. It is neither widely known nor used as a guide for programming.

Country contexts differ widely, and country-level theories of change would be essential complements to a global one. They would encourage DFID country offices to identify important barriers, the potential forces to remove those barriers, and where DFID could most usefully intervene. However, there is no guidance for a country-level theory of change. At least six DFID offices have made a disability stocktake of their existing programmes, but we came across none that have drafted a theory of change. Encouragingly, as part of a new diagnostic exercise examining what is needed to reduce poverty in Nepal, DFID Nepal is planning to commission research to assess the critical challenges facing people living with different types of disabilities, and to present options for how DFID can contribute to addressing these.

In the absence of an agreed global theory of change, the disability framework and the one-page action plan for 2017-18 provide the main overall guidance. They list some important steps towards disability inclusion (such as inclusive education systems and economic opportunities) and identify some key potential actors. But it is less clear what might cause the actors to act, and how barriers could be overcome.

To date, there has been a lack of attention to the role of the private sector

Many institutional and other barriers to the inclusion of people with disabilities lie in the private sector. For example, discrimination or lack of accessibility can prevent people with disabilities from being employed, or being able to trade. Conversely, there are benefits to inclusion: evidence from high-income countries presents a business case for hiring people with disabilities, including higher retention rates, lower absenteeism and equal performance.

The private sector can act to remove barriers. Some large companies are important actors in the global north in identifying and removing obstacles to employment and tackling stigma, and could do the same in the south. There are cases of donors working with the private sector in developing countries – for example the International Labour Organization and Canada with the Bangladesh Employers Federation, encouraging firms to recruit people with disabilities. Donors can also insist that the firms they contract follow good practice. A business interviewee suggested to us that areas of donor engagement with the private sector could include procurement, technology, education, working practices and employment. Box 10 sets out a range of market-based interventions, aimed at small enterprises as well as large ones.

Yet the private sector did not appear in DFID’s meta-theory of change. In the action plan it was limited to delivering economic opportunities, and only as a consortium member in the new UK Aid Connect centrally managed programme. Ahead of the global summit, DFID has now commissioned urgent investigative work on the role of the private sector. A draft theory of change for economic empowerment indicates roles for different elements of the private sector. Private sector actors are invited to the summit, and a list of ‘asks’ of the private sector has been prepared.

Box 10: Market-based interventions to promote inclusion

In 2016, a research programme involving ADD International, the Coady Institute, the Institute of Development Studies and other experts concluded:

“Market-based solutions can deliver at scale. …[T]he most effective approaches not only supported individuals to access markets but also sought to make markets themselves more accessible. The examples ranged from supporting marginalised seaweed farmers in the Philippines to linking individuals on the autism spectrum with job opportunities in IT. Yet across this diversity, we identified a small number of underlying strategies that seemed to show consistent promise. These included: turning marginalised individuals’ disadvantage into advantage by identifying particular skills or assets that gave them a niche; organising collectively amongst the most marginalised; linking highly marginalised people to other less marginalised economic actors in the same community; and working with employers to help marginalised people access in-demand roles.”

There is also insufficient attention to policy dialogue with national governments

The disability framework and the action plan suggested three main routes to influence governments in developing countries. These routes are appropriate, but all have limitations:

- advocacy by disabled people’s organisations – but disabled people’s organisations generally do not have much political weight on their own

- evidence from civil society organisations about what works, which governments can then scale up – but evidence alone rarely induces action

- attendance at the global disability summit – which could galvanise efforts, but will require follow-up.

There is only one mention in the disability framework of a fourth route – the potential role of DFID country offices in policy dialogue with governments, especially in partnership with disabled people’s organisations. Nevertheless, we identified examples of a DFID country office having effective influence on national policy – for example on social protection and the census in Rwanda and on education policy in Nigeria. We understand that DFID country offices have convened meetings with governments and other donors to identify potential commitments on disability ahead of the global disability summit.

Box 11: DFID Rwanda and disabled people’s organisations in policy dialogue with the national government

DFID Rwanda supported the redesign of the Vision Umurenge social protection programme to integrate a stronger focus on disability. DFID Rwanda supported the National Union of Disabled Organisations of Rwanda to carry out participatory research to inform and influence government. The research highlighted that:

- The programme involved only households where the head was a person with disability – ignoring the burden on carers of a child with disability. The guidelines were changed as a result.

- People with disabilities could participate in public works programmes if appropriate work was on offer. As a result, a new scheme of less labour-intensive work has been put in place.

Source: ICAI interview with DFID Rwanda staff.

DFID rightly emphasises the importance of disabled people’s organisations, but provides limited support

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities obliges states to consult with organisations representing people with disabilities. There is also evidence that the advocacy activities of disabled people’s organisations have contributed to governments making significant policy changes on disability inclusion, and to some extent pushing governments to implement their policies. A substantial Norwegian study concluded that the most relevant and effective NORAD interventions were those supporting advocacy and capacity building of disabled people’s organisations.

At the global level, DFID engages well with disabled people’s organisations through the International Disability Alliance (IDA), which co-chairs the donor Global Action on Disability (GLAD) network with Australia and will co-host the global disability summit with the UK and Kenyan governments. IDA is an alliance of networks bringing together over 1,100 organisations representing people with disabilities and their families. While some smaller organisations fall outside the IDA umbrella, IDA is the obvious international interlocutor for DFID.

However, in developing countries, DFID is at an early stage of engaging with disabled people’s organisations. The most substantive funding is provided through the US-based Disability Rights Fund. Evaluations of the Fund have been generally positive. Our desk review suggests that the Fund has enabled national disabled people’s organisations to press governments to incorporate the UN Convention in their policy considerations, though it has been less effective in pushing for implementation. But in 2017, its funding reached only eight of DFID’s more than 32 priority countries: Ghana, Malawi, Rwanda, Uganda, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Burma and Haiti. The Fund is part of DFID’s Disability Catalyst programme, which also supports the International Disability Alliance and the UN Partnership on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (see Box 17) – but neither of those provide medium-term capacity-building support to disabled people’s organisations at country level.

Box 12: Disabled people’s organisations’ advocacy in Bangladesh

In 2012, the Bangladesh government was drafting a disability rights act. With funding from the Disability Rights Fund, the Access Bangladesh Foundation and other disabled people’s organisations arranged a dozen workshops and meetings, including national consultations with government officials and relevant policy makers, to advocate for the review of the draft act. Their recommendations are reflected in the final revised act, which stipulates 21 rights of people with disabilities, including rights to national identity cards and inclusion in the voter list.

DFID country offices have engaged with disabled people’s organisations to varying extents. Our questionnaire distributed to disabled people’s organisations showed that they engaged DFID country offices in seven of the eight countries from which we received a response. However, interviews and the focus group with staff from DFID country offices suggest that, in most cases, DFID country office engagement is at the level of conversations rather than detailed consultation during the design and implementation of programmes. This is confirmed by our desk review of delivery programmes. Only two out of the ten programmes we studied involved substantial engagement with disabled people’s organisations – and both of those programmes related to the funding of the Disability Rights Fund described above. In the remaining eight programmes, disabled people’s organisations were partially involved in three programmes at the design stage; of those three, two had disabled people’s organisations still involved at the implementation stage, and only one at the evaluation stage. As described in paragraph 4.68 below, the preparations for the global disability summit are stimulating more country office engagement with disabled people’s organisations.

While engagement with disabled people’s organisations is essential, donors should take into account important challenges, including:

- Capacity: the vast majority operate at quite low capacities and are under-resourced.

- Inclusivity: a particular set of disabled people’s organisations may not represent all significant impairment groups; some do not represent women well, while some tend not to include the poor.

These challenges emphasise the need for DFID country offices to access and share their experience on relating to disabled people’s organisations. When it comes to supporting them and building their capacity, DFID will do well to also make use of expert intermediaries such as the Disability Rights Fund (offering to fund it to expand the number of DFID’s priority countries in which it operates), umbrella associations of disabled people’s organisations, or relevant non-governmental organisations.

It is difficult to judge the likely effectiveness of programming with disability inclusion aims

There is general agreement, sector by sector, that we have little rigorous evidence about what works for disability inclusion. This makes it hard to judge whether the approach that DFID takes in a particular sector is likely to deliver meaningful results. We examined five sectors – two (humanitarian and education) where DFID has more experience, and so there should be more indication of success, and three that were highlighted in the 2015 disability framework.

The education sector is the most advanced, with ambitions taken even further in the 2018 education policy. One of its three priorities is targeted support to the most marginalised and especially children with disabilities. Disability is also incorporated into the other priorities of investing in teaching, and system reform. We found examples of impactful education programmes in Nigeria, Rwanda and Zimbabwe (see Box 13). But not all initiatives have been successful. On occasion, DFID’s policies have run contrary to national government priorities, for example when governments have overridden DFID’s requirement for universal design in schools.

Box 13: An effective education programme

From 2013 to 2016, DFID’s Education Sector Support Programme in Nigeria helped six state governments introduce inclusive education policies and deliver changes at school and community level that have brought more of the most excluded children into education. Its activities included:

- awareness-raising campaigns for children with disabilities to be enrolled in local schools; messaging that children with disabilities do not only have to attend special schools

- enrolment drives with a strong focus on disability, gender and ethnicity

- training teachers in supporting children with disabilities, such as training in sign language, Braille and attitudes to disability

- conducting of out-of-school surveys to identify which groups of children are commonly out of school

- small-scale efforts to bring special schools and mainstream schools closer together

- small-scale funding of equipment for schools to support disabled learners.

Source: Education Sector Support Programme in Nigeria (ESSPIN) Inclusive Education Review, Helen Pinnock, ESSPIN, June 2016.

In the humanitarian sector, the situation is more mixed. Our desk review of three humanitarian programmes found small but promising disability elements. We understand that other DFID humanitarian programmes and DFID-funded research have included mental health support and treatment for people affected by disasters and conflict. However, the 2017 DFID humanitarian reform policy makes only four mentions of people with disabilities, seeing them as passive – among the “most marginalized and vulnerable in times of crisis”. By contrast, the UN’s 2015 Sendai Framework for Disaster Reduction also identifies the active role that people with disabilities can play in disaster preparedness and disaster response. Internationally, DFID supported the development of the Minimum Standards for Age and Disability Inclusion in Humanitarian Action, and the (non-binding) Charter on Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities in Humanitarian Action. Disappointingly, the multi-stakeholder Grand Bargain that emerged from the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit was weak on disability.

At the current pace and scale of programming, DFID is unlikely to achieve results at scale for the three areas highlighted in the disability framework

We examined three areas where the 2015 disability framework had announced “a proactive approach to further enhancing DFID’s work”: economic empowerment, stigma and discrimination, and mental health and intellectual disabilities. The latter two were also specific recommendations of the 2014 IDC report.

For economic empowerment, we judge that DFID’s current approach is too small to be effective at scale. We found programmes that combine a number of the micro-approaches recommended in the literature as best practice. But they benefit a small proportion of the number of people with disabilities in a country, and constitute a small proportion of DFID’s investment in economic development. For example, the Burma Business for Shared Prosperity programme has a disability sub-project on micro-finance intended to benefit 1,000 people with disabilities, at a cost of £500,000. It funds the Myanmar Centre for Responsible Business to produce guidance on employing people with disabilities, and it hopes to include people with disabilities in a £500,000 grant for micro-insurance, and in work on textiles. But these are a small part of the £55 million budget for the total programme. It is of course entirely appropriate to pilot approaches, but we would have expected a DFID programme to plan to take successful pilots to scale – as the planned Disability Inclusive Development programme is likely to do.

Looking at the macro level, the International Labour Organization estimated the cost of excluding people with disabilities from the workforce as 3 to 5% of GDP.50 DFID has expressed doubts regarding the International Labour Organization’s econometrics, but has commissioned no alternative work. DFID’s chief economist’s office told us that some actions changing social norms on disability could influence the overall economic growth path and have a long-term payoff, but this has not fed through as a reason for DFID to focus on social norm change.