DFID’s approach to supporting inclusive growth in Africa

ICAI Score

Satisfactory achievement on DFID’s overall approach to economic development and learning at the central level, with mixed performance at country and programme levels.

DFID has doubled its expenditure on economic development in recent years to £1.8 billion a year, with the objective of promoting economic transformation and job creation. This is a learning review of its progress in identifying what works and developing a credible approach, focusing on Africa. We find that DFID has pursued a well-considered approach to building up its knowledge and expertise through staff recruitment and a strong research portfolio. A new generation of centrally managed programmes has helped to boost delivery capacity. Having correctly identified that programming must be context-specific, it introduced the inclusive growth diagnostic to support country planning. Its approach has evolved through several strategy documents, leading to the 2017 Economic Development Strategy.

At country level we found a more mixed record. The diagnostic work was of variable quality and did not always lead to greater prioritisation of effort and resources. Country portfolios show a clear focus on the poorest and include some innovative approaches to economic transformation, but their strategic focus is not always clear. Monitoring, evaluation and learning practices are not yet strong enough to support experimental programming. Our sampled programmes lacked an explicit approach to economic inclusion and to monitoring whether marginalised groups were being reached.

Overall, we find DFID’s focus on economic transformation to be an appropriate response to the development challenges facing Africa and a welcome increase in the ambition of its economic development work. The new strategy makes positive commitments to politically smart approaches and economic inclusion. However, to put these into practice, DFID will need a stronger focus on the policy and institutional dimensions of economic transformation and a more systematic approach to economic inclusion.

Executive Summary

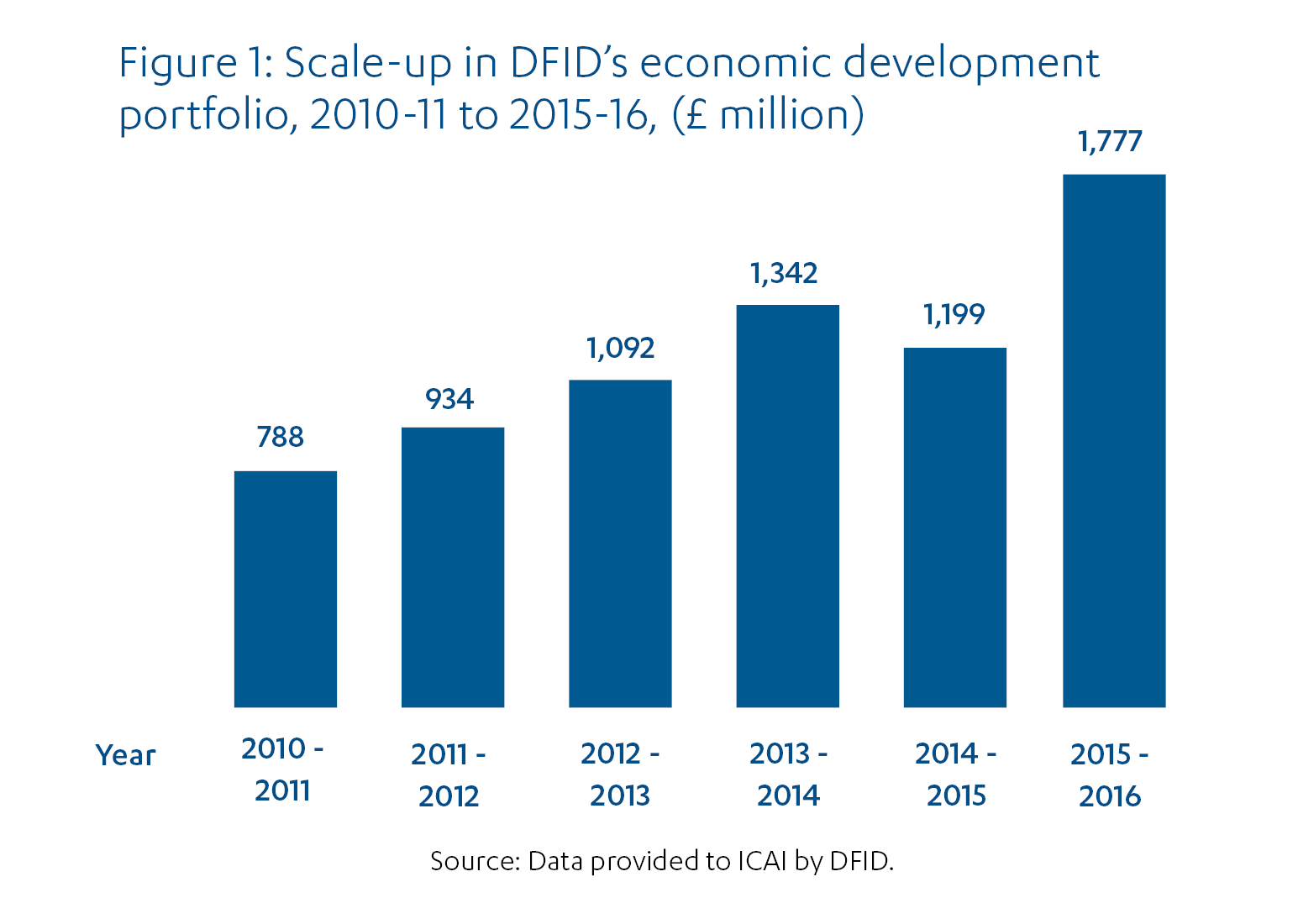

In recent years, DFID has been rebalancing its aid portfolio towards economic development. Its investments have doubled from £934 million in 2011-12 to £1.8 billion in 2015-16. In January 2017, it published a new Economic Development Strategy, announcing a focus on economic transformation and job creation as the key to achieving inclusive growth and sustainable poverty reduction. This represents a major shift in the orientation of DFID’s portfolio, which is still underway.

This learning review assesses how well DFID has gone about learning what works in the promotion of economic development. We have chosen to focus on Africa. While the continent has enjoyed a period of economic growth since 1998 (slowing in the last two years), this has not generated enough jobs to achieve large-scale poverty reduction. With 10 to 12 million young Africans entering the labour force each year, job creation in Africa is an urgent challenge. We have chosen to conduct a learning review, in recognition that global evidence on how to promote job creation on the scale required is still emerging. We explore the learning processes at both central and country levels that have contributed to DFID’s evolving approach. We then assess whether DFID has arrived at a credible overall approach to promoting economic development.

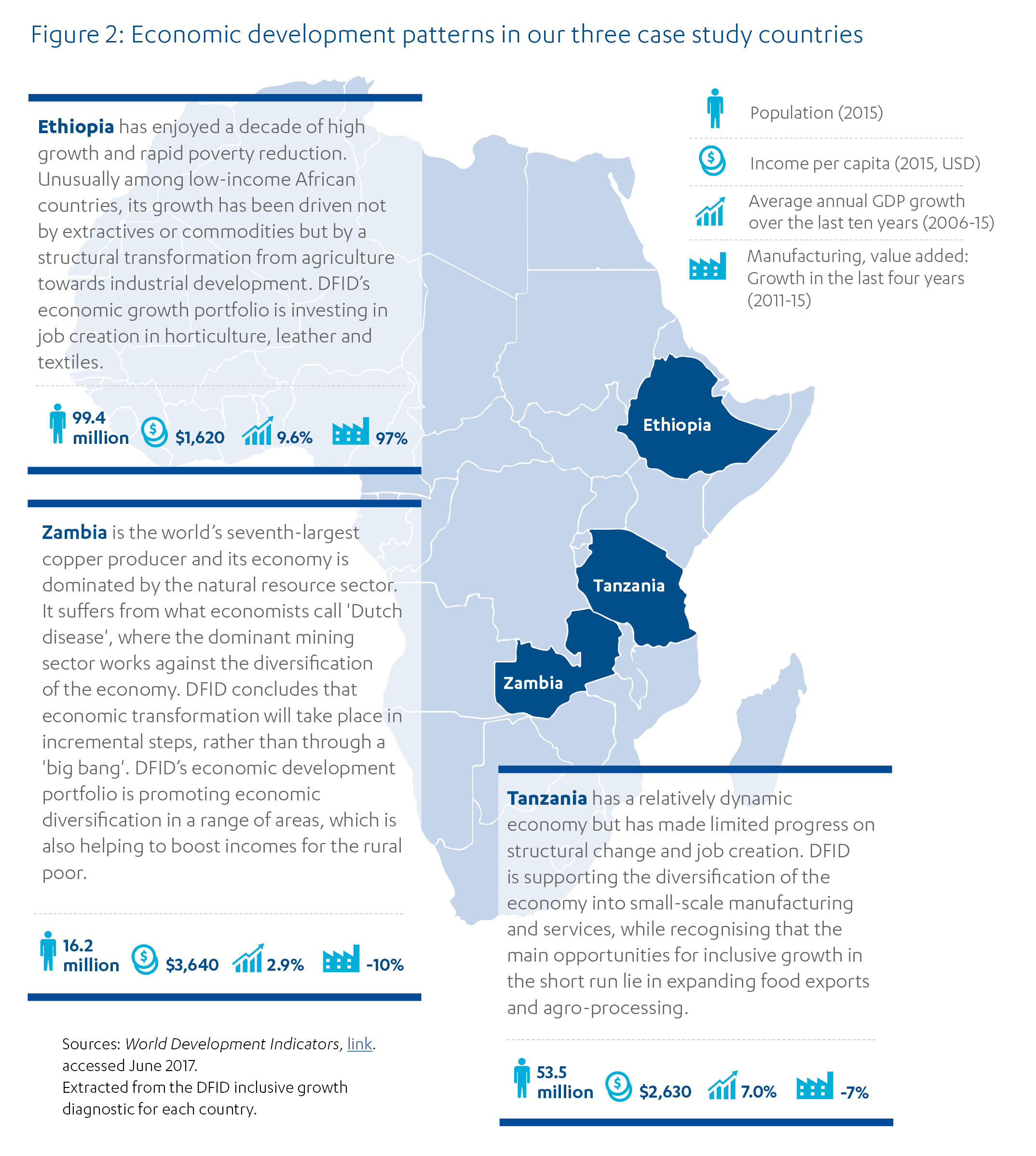

This is a high-level strategic assessment of a very broad portfolio. We have focused on the evolution of DFID’s strategy, its growth diagnostics and its portfolios in three case study countries: Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia (we visited the latter two). We have not covered DFID’s development capital portfolio (loans, equity and guarantees) or its development finance institution, CDC, as these were the subject of a recent National Audit O ce review. We also chose not to look at conflict-affected countries, in order to focus on Africa’s core development challenges.

How well has DFID’s research and diagnostic work informed its approach to inclusive growth and job creation?

In 2013, DFID conducted a stocktake of its readiness to scale up its economic development work, providing a useful baseline against which to measure its learning. At that point, DFID had no economic development strategy. Its wealth creation portfolio was described as deeply heterogeneous, with a good focus on reaching the poorest but limited ambition towards tackling constraints on economic growth. The stocktake concluded that, to scale up successfully, DFID would need to strengthen its organisational capacity, its in-country analytical work and its ability to measure results.

In 2014-15, DFID conducted an inclusive growth diagnostic across 25 countries to identify the constraints on growth and opportunities for DFID to influence them. This was DFID’s first such diagnostic exercise, based on a common conceptual framework. We encountered mixed views on the quality of the work. The analysis was led by country economists. Participation from other professional disciplines varied across countries, resulting in weaknesses in areas such as political economy analysis, social inclusion and climate change. Country offices used different data and analytical techniques to reach their conclusions, and it was not always clear how consistent or robust their answers were. The diagnostics were nonetheless an important learning tool for DFID, showing the strengths and weaknesses of the economic development portfolio and indicating areas where country offices needed further guidance. This informed the development of DFID’s research portfolio and sectoral strategies.

The diagnostics revealed a number of gaps in DFID’s economic development work, in areas such as energy, trade and job creation. Some of these have since been addressed through the development of new centrally managed programmes. While past ICAI reviews have pointed out problems of coherence and coordination between country-level and centrally managed programmes, the new centrally managed programmes are designed in a more strategic way to address gaps in delivery capacity in country offices.

DFID has developed a large research portfolio on economic development, with a total investment of £282 million over the period from 2011 to 2022. The research corresponds well to the knowledge and evidence gaps identified by DFID, and is designed to contribute both to the global pool of knowledge in the area and to DFID’s own programming. There are challenges, however, in applying such a complex body of research. The Research and Evidence Division has produced some useful summaries of emerging findings, but staff in country offices prefer to learn directly from other DFID staff and programmes.

Individual research programmes have uptake reporting requirements, but it is difficult to quantify the uptake of findings across a research portfolio. This means that at this point we are unable to reach a conclusion as to how much the research has contributed to learning.

DFID’s approach to economic development has evolved through successive strategy documents. A series of papers from the chief economist have made the case for a more ambitious portfolio aimed at transformational growth. DFID has developed sectoral strategies on agriculture, infrastructure, sustainable cities and energy (the latter two are not yet approved). The 2017 Economic Development Strategy reflects this process of learning, with a much clearer articulation of DFID’s objectives and overall approach. It also contains some new policy commitments – such as changing international trading rules, leveraging commercial investment through ‘patient capital’ and helping firms from developing countries raise funds in London – that are not grounded in past learning.

Overall, we find that DFID has engaged in a concerted effort to build its knowledge and expertise on economic development, and that its strategy has become progressively clearer and more ambitious as a result, meriting a green-amber score.

Are DFID’s country economic development portfolios informed by evidence?

The Economic Development Strategy correctly states that there is no standard recipe for promoting economic development and that programming must be context-specific, based on in-country diagnostics. In our three case study countries, the impact of the inclusive growth diagnostics on country portfolios has so far been limited, for several reasons. They were out of sync with the programme cycle, coming after the main scale-up of country portfolios in 2012-14 when funds had already been committed. We encountered a few examples of new initiatives that emerged from the diagnostics, amid a wider concern that they were often used to justify existing portfolio choices. However, we recognise that aligning country programmes with diagnostic work necessarily takes time to achieve.

Given differences in country context, the three case study countries show varying levels of ambition towards economic transformation. Ethiopia has identified a clear set of strategic investments with the potential to support both transformational growth and economic inclusion. In Tanzania and Zambia, economic transformation is a more distant prospect. The two offices are experimenting with some potentially transformative interventions, while continuing to invest the bulk of their resources into agriculture, where most poor people work.

We found that all the portfolios have a strong focus on reaching the poor, with a range of interventions targeting different socio-economic groups. However, few programmes are specifically designed to address the exclusion of women and girls, youth or marginalised groups (although there are signs of an increased focus on the economic empowerment of women in more recent programmes). We also found that programmes were not monitoring their distributional impacts to make sure that intended beneficiaries were being reached. We found that monitoring and evaluation practices were not strong enough to support and learn from the level of experimentation that is underway. Along with other donors in this area, DFID lacks standard methods of measuring the results of its economic development programming, particularly on job creation (although it has a partnership with the World Bank to address this). DFID has made some effort to apply value for money analysis to its portfolio, but progress so far is limited in the face of some substantial technical challenges.

Overall, while recognising that the inclusive growth diagnostics were an important step forward, we find that DFID still has some way to go in developing country portfolios that reflect robust in-country diagnostics and learning from programming. This area merits an amber-red score.

Does DFID have a credible approach to promoting inclusive growth and jobs in Africa?

The core objective of DFID’s approach, as it has evolved in recent years, has been to refocus the portfolio towards economic transformation in Africa in order to achieve poverty reduction on a larger scale through job creation. This is a major change in the orientation of DFID’s portfolio, which will take time to work through into programming. We find the new focus on economic transformation to be an appropriate objective and a welcome increase in the ambition of DFID’s economic development work. It responds well to research and evidence on the causes of jobless growth in Africa.

We found a broad consensus among external stakeholders, including academic experts and development non-governmental organisations, that this was the right direction of travel. However, this increased level of ambition for the portfolio raises a set of complex challenges that will need to be addressed over the coming period.

There are concerns among some stakeholders and in the literature about the extent to which the Asian model of mass job creation through industrialisation can be replicated in Africa. DFID will need to be realistic about the pace of change and open to the idea that job creation in Africa may take different forms, including a higher level of informality.

Some external stakeholders expressed a concern that DFID is not prioritising its investments based on its comparative advantage relative to other development actors. The current strategy correctly identifies that prioritisation should occur at the country level. The inclusive growth diagnostic is an important step in this direction. The first round of diagnostics, however, did not do enough to push country offices to make strategic choices. We saw some evidence, particularly in Tanzania, that investments were spread too widely for strategic impact. While a period of experimentation may be necessary in some contexts to identify what works, DFID should move as quickly as it can towards more focused investment in specific sectors, value chains or issues.

The Economic Development Strategy recognises the importance of the state in driving economic transformation and calls for a politically smart approach to economic development. We welcome this focus on the political dimension of economic transformation. Politically smart programming should be part of DFID’s comparative advantage in this area. While political economy analysis forms part of DFID’s diagnostic work, it was not a strong feature of the portfolios we reviewed. In our case study countries, DFID had identified areas where it hoped to influence government policy. However, several stakeholders in Zambia were concerned that DFID is too detached from government to be influential. We therefore welcome the commitment in the Economic Development Strategy to a stronger focus on the political and institutional constraints on economic transformation.

The strategy makes a clear statement on the importance of economic inclusion. Looking across the portfolio, we see three main strands to DFID’s approach to inclusion: supporting mass job creation through economic transformation; promoting income growth for the poor in existing livelihood areas; and ensuring that particular social groups (women and girls, youth, people with disabilities) are reached through DFID programming. At the country level, we found that country portfolios had a strong focus on the rural poor (the second form of inclusion). Most programmes did not target particular social groups, although there is increased attention to women’s economic empowerment in more recent programmes. Although the strategy makes a clear statement about the importance of providing improved jobs for the poorest, most DFID programmes in our sample are currently focused on the quantity rather than the quality of jobs created.

Overall, we welcome DFID’s increased ambition towards economic transformation, and we dind that the new strategy sets out some good foundations, including politically smart approaches, context-specific programming and economic inclusion. While there are substantial challenges ahead in implementing these commitments, we dind the approach to be a relevant and credible one, meriting a green-amber score.

Conclusions and recommendations

We find that DFID has taken a structured and considered approach to building up the learning required for a more ambitious economic development portfolio, meriting an overall green-amber score. A number of the concerns we raised in past ICAI reports have been addressed, but others remain outstanding. We have made recommendations in a number of areas where we believe the portfolio could be improved.

Recommendation 1

DFID’s diagnostic and planning tools should more clearly support and encourage country offices to prioritise and concentrate their investments into areas with the greatest potential for DFID to contribute to transformative growth.

Recommendation 2

DFID should provide more guidance on how to build a portfolio that balances investments in long-term structural change and job creation with programming to increase incomes for the poor in existing livelihood areas, taking into consideration the time required for economic transformation in each country context.

Recommendation 3

Recognising the centrality of the state to economic transformation alongside the private sector, DFID should prioritise learning on how to combine politically smart and technically sound approaches to economic development.

Recommendation 4

To meet the commitments in its Economic Development Strategy and drawing on broader learning on inclusion, DFID should ensure that, in each of its partner countries, opportunities for addressing the exclusion of women, young people and marginalised groups are identified and built into programme designs and results frameworks wherever feasible, and that distributional impacts (whether intended or unintended) of its programming are routinely monitored and assessed.

Introduction

In recent years, DFID has set about rebalancing its aid portfolio towards the promotion of economic development as the engine of poverty reduction. From its traditional focus on social services, the department has worked to build up its knowledge on the drivers of and constraints on growth. Its economic development portfolio has doubled from £934 million in 2012 to £1.8 billion per year.1 The portfolio is diverse, covering the business environment, infrastructure, the financial sector, agriculture, industrialisation and urbanisation, among other areas.

The purpose of this learning review is to assess how well DFID has gone about learning what works in the promotion of economic development, and how far it has come in developing credible portfolios of programmes that are adapted to the opportunities and challenges in the countries where it works. We have chosen to focus on Africa. While parts of Asia have seen dramatic declines in poverty in recent decades, driven by mass employment creation, this dynamic is yet to be replicated in Africa. Africa has enjoyed a period of relatively buoyant economic growth over the past two decades, based on strong global demand for its primary resources, although this has slowed since 2014. However, the continent’s growth has been largely jobless in nature and has not translated into large-scale poverty reduction. An estimated 10-12 million young Africans enter the labour force each year, but only three million find formal sector jobs.2

In choosing to conduct a learning review, we recognise that this rebalancing of the portfolio towards economic development is an ongoing process that will take time to accomplish. We also recognise that it takes DFID into areas where the evidence of what works is patchy – particularly at the scale at which DFID now seeks to operate. Our interest here is not whether DFID knows all the answers, but whether it is going about the challenge in a structured manner to enable rapid learning and effective policy engagement and programming.

Box 1: What is an ICAI learning review?

ICAI learning reviews examine new or recent challenges for the UK aid programme. The focus is on knowledge generation and the translation of learning into credible programming. Learning reviews do not attempt to assess impact. They o er a critical assessment of progress to date and whether programmes have the potential to produce transformative results. Our learning reviews recognise that the generation and use of evidence are central to delivering development impact.

Other types of ICAI reviews include performance reviews, which probe the efficiency and effectiveness of UK aid delivery, and impact reviews, which explore the results of UK aid.

DFID published a new Economic Development Strategy in January 2017.3 While it is too soon to review its impact on the portfolio, the strategy summarises an approach to economic growth that has emerged over several years, together with some novel elements. It identifies economic transformation and job creation as key to inclusive growth and large-scale poverty reduction. One of our central concerns in this review is whether DFID’s approach is genuinely inclusive – that is, whether the benefits are likely to reach the poorest and most marginalised, in keeping with the Sustainable Development Goals and the ‘leaving no one behind’ pledge.4

Box 2: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to

action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

Related to this review

Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all

Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all

Sustainable economic growth will require societies to create the conditions that allow

people to have quality jobs that stimulate the economy while not harming the environment.

Job opportunities and decent working conditions are required for the whole working-age population.

![]()

Build resilient infrastructure, promote sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation

Inclusive and sustainable industrial development is the primary source of income

generation, allows for rapid and sustained increases in living standards for all people, and

provides the technological solutions to environmentally sound industrialisation.

The SDGs show a strong concern for inequality within and between societies. Goal 8’s targets seek aspects of economic growth and productivity that would be inclusive and include groups in society that may often be neglected, such as women, youth and those with disabilities. Goal 9 encompasses three important aspects of sustainable development: infrastructure, industrialisation and innovation. The report assesses how DFID programmes are supporting attempts in Africa to create growth opportunities that are inclusive in nature. It also assesses whether such ventures are creating appropriate employment opportunities in transformative industries. Such programmes are a key part of efforts to achieve Goals 8 and 9 of the SDGs.

We begin by looking at DFID’s approach to learning what works – first at the central or strategic level and then at the country level. We then assess the relevance of DFID’s overall approach and emerging portfolio to the objectives of promoting large-scale poverty reduction through inclusive growth. Our review questions are set out in Table 1. The assessment draws on our case studies of DFID’s economic growth portfolios in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia (we visited the latter two).

ICAI has looked at aspects of this portfolio on two previous occasions. In May 2014, we published a report on DFID’s Private Sector Development Work,5 while our May 2015 Business in Development report reviewed the role played by business in the UK aid programme.6 The findings from those reviews form part of the baseline for our assessment, and we conclude with some observations of how far the situation has moved on since the earlier reports.

The scope of this review is broad. Many types of development programme contribute directly or indirectly to inclusive growth. Our review covers any programmes that DFID identified to us as part of its economic development portfolio – although we excluded social protection programming, which was covered under a previous ICAI review.7 We have not covered DFID’s development capital portfolio (that is, equity investments, loans or guarantees) or the work of its development finance institution, CDC, as this has been the subject of a recent review by the National Audit Office.8 In our choice of case study countries, we chose not to examine the specific economic development challenges caused by conflict and fragility but to focus on the wider challenges of job creation and economic inclusion.

Because of the breadth of the subject matter, our assessment is necessarily at a strategic level. We hope to come back in future reviews to explore the effectiveness of particular categories of economic development programming in more depth.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions |

|---|

| 1. Learning: How well has DFID’s research and diagnostic work informed its approach to inclusive growth and job creation? |

| 2. Learning: Are DFID’s country economic development portfolios informed by evidence and learning? |

| 3. Relevance: Does DFID have a credible approach to promoting inclusive growth and jobs in Africa? |

Methodology

The main methodological elements to our review were as follows:

- We reviewed academic literature on the opportunities for and constraints on inclusive growth in Africa and the record of development interventions designed to promote it. We also compared DFID’s research investments with the international literature to assess how well DFID has contributed to building the evidence base.

- We reviewed the evolution of DFID’s strategies and guidance, the design and application of in- country diagnostic tools and the thematic coverage of DFID’s economic development research portfolio.

- We carried out key stakeholder interviews with 127 people familiar with DFID’s strategy, programming and research portfolio on inclusive growth. This included 46 DFID staff and 23 experts from UK-based non-governmental organisations, academic institutions and think tanks. We also interviewed 58 stakeholders during our two country visits, including other donors, national government officials, implementers and local civil society. We sought out critical voices to help us challenge DFID’s thinking.

- We carried out country case studies of DFID’s inclusive growth portfolios in three countries: Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia. Two of these countries, Tanzania and Zambia, were visited by the review team. The countries were selected for having a sizeable economic growth portfolio with several years of delivery, and representing a range of economic and political conditions. In each country, we assessed the process for preparing the country growth diagnostic, including the evidence and learning it drew on and how it translated into programming choices. We visited a sample of programmes to interview implementers and counterparts to gain a better understanding of the learning processes involved.

- We selected a sample of 12 programmes from the three case study countries for more detailed review. These were selected from lists of relevant programming provided by DFID, and limited to programmes with at least 50% of their expenditure on economic development. A list of the programmes is included in Annex 1. For each programme, we assessed the design and available results data for its potential to promote growth and job creation, its attention to inclusion and the quality of its results management.

Box 3: Limitations of our methodology

Our sample of countries and programmes was relatively small and designed to cover a substantial range of sectors and intervention types. It focused on new and innovative programming, to assess learning. The sample is therefore not intended to be representative of DFID’s economic development portfolio as a whole, and the findings from our country case studies and programme reviews may not be fully applicable to other countries and programmes.

As a learning review, our focus is on learning, strategy and programme design, rather than effectiveness. While some of DFID’s results data is presented here, we have not carried out full assessments of the effectiveness or impact of any programme or portfolio.

Background

DFID’s commitment to economic growth and transformation

Since the start of the coalition government in 2010, DFID has set about rebalancing its portfolio towards the promotion of economic development. In 2010, it announced wealth creation as one of its main priorities.9 A Growth Refresh in 2012 affirmed that economic growth is indispensable for long- term poverty reduction and that, as countries move up the income ladder, the focus of development assistance should shift from the direct provision of social services for the poor towards promoting an enabling environment for growth. The centrality of growth was reaffirmed in a 2014 Economic Development Strategic Framework and,10 most recently, in a new Economic Development Strategy, published in January 2017. 11 The latter adds a new dimension to the economic growth agenda by stressing that bilateral trade and investment in developing countries can help promote mutual prosperity and project ‘Global Britain’.

Over the next decade a billion more young people will enter the job market, mainly in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Africa’s population is set to double by 2050 and as many as 18 million extra jobs a year will be needed. Failure will consign a generation to a future where jobs and opportunities are always out of reach; potentially fuelling instability and mass migration with direct consequences for Britain. Our ambition must be to create an unprecedented increase in the number and quality of jobs in poor countries; enable businesses to grow and prosper; and support better infrastructure, technology, connectivity and a skilled and healthy workforce.

DFID has also increased the level of ambition of its economic development portfolio. From an initial focus on livelihoods for the poor, DFID has come to see economic transformation as a key objective. ‘Economic transformation’ refers to a structural change in the economy where labour and other resources move from low-productivity activities, such as subsistence agriculture, into more productive areas, such as commercial agriculture, manufacturing and services.12 Large-scale poverty reduction in Asia in recent decades began with the creation of mass employment, particularly in low- skilled sectors such as textiles, supported by high levels of public investment and building on prior advances in agriculture and education. In Africa, over the past decade, there has been little economic transformation, and economic growth has not translated into jobs on the scale required to make major inroads into poverty (see Box 4). DFID sees the creation of jobs through economic transformation as key to achieving sustainable development and ending poverty.

Box 4: A decade of jobless growth in Africa

Since the turn of the century, Africa has enjoyed a period of buoyant economic growth. Sub-Saharan Africa has achieved average growth rates of 5.2% for 20 years, driven by strong global demand for its raw materials, including oil, other minerals and agricultural products. The rate of growth has slowed over the past two years as global economic conditions have become less favourable, showing the risks of high dependence on commodity exports. Despite this lengthy period of growth, poverty rates have been slow to decline and are o set by high population growth, so that the total number of people living below the international poverty line has continued to rise, from 358 million in 1996 to 415 million in 2011. In fact, poverty rates have proved less responsive to economic growth in Africa than in any other developing region. Capital-intensive industries like oil and mining do not generate enough jobs to make significant inroads into poverty. As a result, the benefits of growth are concentrated in larger cities and commodity- producing areas.

This contrasts sharply with East Asia’s development path in the late 20th century, where growth was driven by industries such as textiles and footwear that created large-scale employment for the poor. This rapid movement of people from traditional agricultural livelihoods into more productive employment – which economists call structural economic change – is yet to materialise in Africa. The share of manufacturing in Africa’s gross domestic product in 2010 was just 10% – slightly lower than it had been in the 1970s. However, there are some positive trends. Urbanisation has led to a growing African middle class, estimated at 310 million in 2011, which offers an increasingly attractive market for African businesses and foreign investors. Moreover, as wages rise in China and other parts of Asia, manufacturing in Africa becomes more competitive – particularly in larger countries like Ethiopia, where factory wages for unskilled labour are only a quarter of those paid in China. If other conditions for production can be created, such as energy and transport infrastructure and a supportive business environment, Africa has the potential to participate in global value chains. There are also growth prospects through the production of higher-value agricultural goods, both for export and for local urban consumers. Countries such as Kenya, Uganda and Senegal are already successfully exporting processed fruits and vegetables to international markets.

The challenge for DFID is to ensure that its investments translate into poverty reduction. Promoting economic transformation may not immediately benefit the poor, while the contribution to poverty reduction through employment creation may be long and uncertain. While there has long been debate among development economists as to whether economic growth on its own is sufficient to achieve poverty reduction,13 a recent consensus has emerged that growth must also be equitable if it is to make a significant impact on poverty.14 The Sustainable Development Goals and other development agendas therefore emphasise inclusive growth,15 although there is no settled definition of the term (DFID’s Economic Development Strategy uses the term ‘economic inclusion’). One of our themes for this review is to assess how DFID manages the dilemma between focusing on transformational growth and ensuring that the poor are able to benefit from it.

Expenditure and programming

There is no precise way of measuring DFID’s expenditure on economic development, as it covers a wide range of sectors, activities and delivery channels. By DFID’s own calculation, its expenditure on economic development has more than doubled over the past four years. From £788 million in 2010- 11, it reached £1.8 billion in 2015-16 (see Figure 1). Within Africa, DFID runs economic development programmes from 12 regional or country offices.16 It also has a growing portfolio of centrally managed programmes, mainly managed by the Private Sector Department or Africa Regional Division.

The portfolio includes work on governance (public financial management, business regulation), agriculture, infrastructure (especially energy and transport), trade facilitation, urban development, access to finance, skills and education, forestry and fisheries, and a range of business development activities. The delivery channels are diverse, including private contractors, partnerships with multilateral agencies, grants for non-governmental organisations, and financial and technical assistance for government. In recent years, several centrally managed programmes have been launched to increase the scale of programming in a number of areas, such as urban growth, energy and job creation for women (see Box 8).

Some programmes invest directly in businesses, for example by providing access to finance, linking them to business development services or supporting their entry into international value chains. Most seek to create a more favourable environment for business development by focusing on key enablers for the private sector, such as building trade-related infrastructure, creating a more skilled labour force, strengthening property rights and reforming business regulations and taxes. The major activities in our case study countries are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: DFID’s economic development portfolio in our case study countries

| Country Portfolio | Principal Activities |

|---|---|

| Ethiopia

11 programmes £371.2 million |

Ongoing:

In the pipeline:

|

| Tanzania

17 programmes £376.1 million |

Ongoing:

In the pipeline:

|

| Zambia

11 programmes £108.4 million |

Ongoing:

In the pipeline:

|

Source: Based on data provided to ICAI by DFID. There is no precise method for calculating the size of DFID’s economic development expenditure in any given country. The numbers given here follow DFID’s method for calculating its global expenditure on economic development. The portfolio is de ned as including all programmes with expenditure in the input sectors identified by DFID as falling within its economic development portfolio, which were live in August 2016. The portfolio budget figure includes the share of the lifetime budget of each programme assigned to those sector codes. The figures do not include budgets from centrally managed programmes active in each country, as these do not yet report their expenditure per country.

Findings

In this chapter, we set out the findings of our review. We begin with DFID’s learning processes at central level and then turn to the use of evidence and learning in DFID’s country portfolios. Finally, we assess the relevance of the overall approach and emerging portfolio.

How well has DFID’s research and diagnostic work informed its approach to inclusive growth and job creation?

DFID’s commitment to rebalancing its portfolio towards economic development began after the coalition government was elected in 2010. A doubling of its economic development portfolio (see Figure 2) was accompanied by measures to strengthen its organisational capacity,17 map its existing programming, develop new centrally managed programmes and establish a large research portfolio. Along the way, DFID developed its approach to economic development through several strategy documents. In this section, we explore these processes and how they have contributed to and drawn from DFID’s learning on economic development.

In 2013, DFID conducted a stocktake of its readiness to scale up its economic development work.18 This provides a useful baseline against which to measure subsequent learning. At the time, DFID had no economic development strategy, but implicitly followed the conclusion of a 2008 World Bank Commission on Growth and Development.19 The Growth Portfolio Review described DFID’s wealth creation portfolio as deeply heterogeneous, with varying levels of contextual analysis. Most of its market interventions were at household, farm or small rm level, particularly in agriculture and access to finance. While the portfolio was often innovative and had a good record of targeting the poorest (as con rmed in the past by ICAI),20 it showed limited ambition towards tackling the most important constraints on growth. The review concluded that, to scale up its portfolio, DFID would need to strengthen its organisational capacity, its in-country diagnostic work and its ability to measure results.

Growth is not an end in itself. But it makes it possible to achieve other important objectives of individuals and societies. It can spare people en masse from poverty

and drudgery. Nothing else ever has. It also creates the resources to support health care, education, and the other Millennium Development Goals to which the world has committed itself.

Box 5: ICAI’s 2014 review of DFID’s private sector development work

A May 2014 ICAI review of DFID’s private sector development work pointed to a mismatch between DFID’s high ambitions and its capacity to deliver. It found that the portfolio had a good record in delivering results for the poor at the individual programme level. However, DFID staff lacked experience of working with the private sector, and needed to develop practical approaches to translating its objectives into viable programme models, based on a clear idea of its comparative advantage alongside other actors. It called for DFID to find an appropriate balance between short-term measures that directly benefit the poor and longer-term investments in systemic change.

The inclusive growth diagnostic informed strategy development, programming and research

The 2013 Growth Portfolio Review observed that there is no standard recipe for generating economic growth and that better diagnostic analysis was needed in each country to identify opportunities and constraints.21 In 2014, DFID developed the inclusive growth diagnostic, to be undertaken across 25 countries, three regions and five thematic areas. The contribution of the diagnostic to the country programming is considered in the next section. Here, we look at its contribution to learning at the central level.

Our approach is context-speci c. We conducted an in-depth assessment of the constraints to inclusive growth in 28 of our partner countries. This helped determine how and where we should focus our e orts. The analysis put a spotlight on jobs

and showed, for example, the need to step up e orts on energy, infrastructure,

urban development, manufacturing and commercial agriculture. It underlined how economic development has to contend with vested interests that block progress; with violence and instability; and with barriers that prevent large parts of society, including girls and women, from economic participation. It also showed the need to avoid an overloaded reform agenda that tries to x everything at once and instead to focus on what is feasible in each context and will make the greatest di erence. Our country-by- country assessment is helping us reshape our programmes and priorities.

The inclusive growth diagnostic is a template for diagnosing the constraints on inclusive growth in DFID’s partner countries. It was developed in consultation with leading economists, development non-governmental organisations and other donors. It defines inclusive growth as “growth which creates employment across society and which transforms the structure of the economy, enabling the productivity of workers to rise”. It also uses the term ‘holding pattern growth’ for growth that is not transformational but which generates sufficient income to alleviate poverty in the interim until other opportunities emerge. Country offices were tasked with answering a series of questions (see Box 6). The exercise was done in two parts, over several months: the first examining constraints on growth and the second focusing on the opportunities for DFID to make a difference. Each diagnostic was subject to internal peer review.

Box 6: DFID’s inclusive growth diagnostic template

The inclusive growth diagnostic prompted DFID country offices to address the following questions and issues, summarising the results in a 15-page document.

| Questions | Areas to consider |

|---|---|

| What has driven the currently observed pattern of growth? |

|

| What are the sectoral opportunities for inclusive and transformational growth? |

|

| What factors constrain inclusive growth? | Cross-cutting factors

Sectoral factors

|

| What political or institutional factors enable constraints to persist? |

|

| What are the options for DFID actions to address constraints? |

|

This was the first time that DFID had developed and implemented a common diagnostic tool to guide its sectoral programming (although its country poverty reduction diagnostic had involved a similar exercise at the country portfolio level). We encountered a range of views across DFID staff on the quality and usefulness of the exercise. In many instances, the analysis was conducted by the country economist; participation from other professional disciplines varied by country. As a result, some DFID stakeholders told us that the diagnostics were relatively weak on political economy analysis, social inclusion and climate change. While a standard set of questions were addressed, there were no standard methods for answering them. Country offices prepared their analysis based on different types and levels of data and evidence, and were not always clear as to how they had reached their conclusions, making it difficult to assess how consistent or robust the answers were (see Box 7).

Box 7: Possible inconsistency across inclusive growth diagnostics

The inclusive growth diagnostic provided country offices with a template of questions, but no standard methodology for answering them. Each country office drew on different data sources and the basis for their conclusions was not always specified, making it difficult to assess whether the analysis was consistent across countries. For example, in the area of workforce skills:

- The Ethiopia diagnostic assessed that skills and workforce capacity were not a primary constraint on growth. Its analysis was that, while basic numeracy and literacy were low, “systematic evidence of business constraints, evidence of wage premiums for skilled labour and the existence of underemployment even amongst skilled groups” all suggested that general skills were not yet a constraint on manufacturing growth.

- The Tanzania diagnostic concluded that low education standards were a major constraint on growth, based on surveys of businesses. DFID Tanzania has a number of skills development programmes.

- The Zambia diagnostic assessed the skills gap as a barrier to young people participating in the labour market and as a long-term constraint on investment and economic transformation. Yet Part II of the diagnostic noted that DFID Zambia had decided prior to the diagnostic not to be directly involved in skills development given that evidence suggests this is not a binding constraint.

The absence of an established methodology left a risk that country offices drew inconsistent conclusions from similar evidence or used the analysis to support existing portfolio choices. In interviews with us, the Growth and Resilience Department stated that it would like to introduce standard methodologies into future diagnostics.

The diagnostics treat inclusive growth as involving a combination of economic transformation and ‘holding pattern growth’, where people realise higher incomes from existing activities without changing their mode of production. According to an internal guidance note, there are limits to the extent of poverty reduction that can be achieved through ‘holding pattern growth’, but it may nonetheless be appropriate for alleviating poverty in the short term, if mass employment creation through economic transformation is judged as being some way off.22 The diagnostic itself offers no guidance on how to analyse the level or pace of job creation that is feasible across sectors. Nor does the analysis support the important choice facing country offices about the balance of their investments between transformative and ‘holding pattern growth’. It is notable that the World Bank’s growth diagnostics (which are more elaborate exercises) look in more detail at poverty, sustainability and inclusion, as well as growth prospects.23

While DFID acknowledges that there is scope to improve its diagnostic work in the future, the exercise has nonetheless been influential on the department’s evolving approach to economic development. It pointed to a series of opportunities for and constraints on transformational growth that were not receiving enough focus in DFID’s portfolio, including energy, transport, trade, job creation, growth policy and a politically informed approach to reforming the business environment. It emphasised the continuing importance of agriculture in ensuring economic inclusion and the need to do more for the economic empowerment of women and girls.24 It also pointed to various areas where DFID country offices lacked the evidence, resources or expertise to expand their portfolios.

Some of the programming gaps have been addressed through the development of new centrally managed programmes (see below). In areas where country offices indicated that they needed further support, DFID prepared new sector strategies: on agriculture (2015), infrastructure (2016), energy and urbanisation (not yet published).25 Evidence gaps became the subject of new research programmes, including on the role of transport and energy infrastructure in inclusive growth. The diagnostics also prompted a stronger emphasis on inclusion and gender mainstreaming in the 2017 Economic Development Strategy. They therefore had a significant influence on the evolution of DFID’s overall approach to inclusive growth.

DFID has since been engaged in a joint learning exercise with the World Bank on their experience with diagnostics, and has agreed to future collaboration on strengthening diagnostics relating to jobs, gender, governance and political economy analysis. No decision has yet been taken as to whether another round of growth diagnostics will be conducted.

Centrally managed programmes are boosting DFID’s capacity on economic development

One of the challenges of scaling up in economic development is the breadth of expertise required, spanning multiple sectors, themes and intervention types. The 2013 Growth Portfolio Review identified skills shortages within DFID in labour economics, infrastructure and all productive sectors other than agriculture and extractives.26 To increase its capacity, in 2014, DFID established the Economic Development Directorate as a centre of expertise. The directorate encompasses the Growth and Resilience Department, the Private Sector Department and teams working on international trade and the multilateral system. The number of private sector advisors has increased from approximately 30 in 201127 to 93 in 2016-17.28 In its recruitment, DFID has prioritised people with finance and investment experience. The private sector development technical competency framework (which sets out the skills required for recruitment, performance management and promotion) has been updated to include economic development, inclusive growth and poverty reduction. Furthermore, the competency frameworks for other advisory disciplines have also been updated to require an understanding of economic development processes and policy as a cross-cutting theme. DFID also increased its investment in staff training and professional development, including through annual conferences, training courses, seminar series, topic guides and other online learning resources.29

While DFID’s overall capacity has increased, the greater size and diversity of the economic development portfolio is challenging for country teams to support, particularly in small offices. To address this constraint, DFID is making more strategic use of centrally managed programmes, managed either by the Private Sector Department or by the Africa Regional Division. These comprise 28% of our sample by budget, but their significance will increase in the coming period with the launch of a number of large new centrally managed programmes, targeting areas such as foreign investment and urbanisation, commercial agriculture and job opportunities for women (see Box 8).

Box 8: New centrally managed programmes on economic growth

In recent years, DFID has turned to centrally managed programmes to expand the scale and range of its economic development portfolio. Some of the most important recent and pipelines investments include:

- Invest Africa (up to £100 million; underway): The programme aims to create 90,000 jobs in Kenya, Ethiopia and other African countries by generating significant increases in foreign investment in the manufacturing sector, agro-processing and high-value services. It will provide flexible technical assistance tailored to individual country needs, in areas such as investment promotion agencies, local content units, trade facilitation, special economic zones and growth diagnostics.

- Cities and Infrastructure for Growth (£82 million; underway; 2017-22): Operating in Burma, Uganda and Zambia, the programme will deliver a series of interventions to help city economies become more productive, deliver access to reliable and affordable power for businesses and households and strengthen investment into infrastructure services (including from UK investors). It will deliver technical assistance to help strengthen policies and institutions to promote investment, growth and job creation.

- Work and Opportunities for Women(£12.8million; underway;2016-21):The programme aims to provide 300,000 women with improved access to better jobs in agricultural supply chains, manufacturing and other sectors in multiple countries in Africa and Asia. It will work with businesses (including British companies) and their suppliers to address barriers to women’s employment, such as childcare obligations, discrimination and violence in the workplace, and help women move into higher-paying roles in farms, factories and distribution networks. The programme aims to support increases in the number of women beneficiaries in 35 other DFID economic development programmes.

Source: DFID business cases and other information provided by DFID

ICAI’s 2015 Business in Development report found that DFID struggled to ensure coherence and coordination between centrally managed programmes and its country portfolios.30 Country office staff lacked the time to engage with centrally managed programmes operating in their territory. Similarly, DFID’s own analysis raised questions as to how embedded these programmes can be in the country context.31 DFID is now using centrally managed programmes in a more strategic way. They are designed to fill gaps in country portfolios identified by the inclusive growth diagnostic, and country offices are consulted as to where they will work. Country offices have the option of co-funding centrally managed programmes, in order to scale up their work or help them to adapt their programming models to local conditions. We saw this with AgDevCo in Zambia and TradeMark East Africa in Tanzania. A number of new centrally managed programmes come with additional advisory support based in country or regional offices. DFID staff in Zambia told us that this additional support is highly valued. Among other things, these centrally managed programmes are enabling DFID to develop multisector programmes that support growth opportunities in urban areas. These are technically demanding programmes that would be difficult to manage within country teams.

The growth in centrally managed economic development programmes is therefore a useful innovation for overcoming capacity constraints and increasing the breadth and scale of DFID’s portfolio. However, it opens up a series of new questions about which activities are most efficiently managed at which level and what the proper role of country-managed programmes alongside centrally managed programmes and development capital platforms should be. For example, should country-based programmes focus on getting the policy and institutional environment right and piloting innovative approaches, while leaving it to centrally managed programmes to take successful initiatives to scale? These are important questions for the future of DFID’s delivery model in economic development and other areas.

DFID’s large research portfolio broadly matches identified evidence gaps

DFID has developed a large research portfolio on economic development. Economic development is one of five priority themes for DFID’s research portfolio. It has grown from five programmes totalling £43.7 million in 2011 to 25 programmes, with a total investment of £282 million, over the period from 2011 to 2022.32 As with most DFID research, it is intended both as a contribution to global knowledge in the development eld and as a source of learning and evidence for DFID’s own programming.

Most of the research is managed by DFID’s Research and Evidence Division and organised around four themes: macroeconomic issues and economic development; productivity; infrastructure; and jobs and people. The Growth and Resilience Department also funds research programmes, while country offices commission research through the Economic and Private Sector PEAKS facility and the East Africa Research Hub.33 The research partners include UK universities, multilateral agencies, private contractors and research institutes. Two of the primary research partners are African (the Africa Economic Research Consortium and the Partnership for Economic Policy, both based in Kenya), and others collaborate with local research partners.

DFID’s largest research investment has been the International Growth Centre (£51 million; 2013-16), which supports a global network of researchers around the world, including in Africa. It provides research and advice to policymakers in developing countries, at arm’s length from DFID, to help them adapt international learning to local contexts.34 In Ethiopia, for example, it has run research projects on roads, trade liberalisation, youth unemployment, urban housing, smart cities, rural electrification and climate change.

We mapped the research portfolio against knowledge and evidence gaps identified in DFID’s various economic development strategies and found a good level of correspondence. DFID has focused its research on areas identified as of strategic importance, including labour markets and job creation, gender equality, private enterprise development, urbanisation and energy. We found a strong consensus among both internal and external stakeholders that the research is targeted in the right areas.

While many of the research programmes are ongoing, the Research and Evidence Department has made efforts to capture and disseminate emerging results through its Research for Development website. It has produced rapid evidence assessments, which synthesise results both from its own portfolio and from other research, in a range of areas including the business environment, investment, trade facilitation, urban finance and property rights. For example, a recent Jobs Evidence Review provides an overview of research on job creation and links through to ongoing research programmes that address the issue.35 We heard feedback from a number of DFID staff in country offices that these synthesis products helped to make the research more accessible.

Across our sample, we found a limited number of concrete examples of DFID’s research portfolio having a direct impact on programme design. There are some references to research papers or synthesis products in DFID strategies (such as the 2015 Conceptual Framework on Agriculture and the 2015 Infrastructure Policy Framework) and in the design of centrally managed programmes. DFID informs us that the Overseas Development Institute’s Supporting Economic Transformation programme (2014-18)36 had a significant impact on the 2017 Economic Development Strategy, even if not directly cited. The Growth and Resilience Department also funded the 2016 UN High-Level Panel for Women’s Economic Empowerment (former international development secretary Justine Greening was a member). Research from this initiative informed the 2017 strategy and a new centrally managed programme on women and work.

Each individual programme has its own reporting requirements and DFID’s Research and Evidence Division collates examples of research impact, such as influence on government policy. However, it is difficult to quantify the uptake of findings across a research portfolio, whether in its own programmes or by other development actors. This finding applies across DFID’s research portfolio, not just in economic development. This means that at this point we are unable to reach a conclusion as to how much the research has contributed to learning. Given the scale of investment in research in this area, a more systematic approach to measuring its influence would be warranted.

DFID’s approach to inclusive growth has become progressively better articulated

In 2012, DFID had no economic development strategy of its own. Over successive documents, its approach has become better articulated, drawing on learning from the inclusive growth diagnostics and think pieces from the chief economist.

A series of papers produced by DFID’s chief economist synthesising the latest economic theory and evidence have been influential on DFID’s approach. A Growth Refresh paper in 2012 outlined the importance of basing interventions on country-level economic and political diagnostics, in order to identify binding constraints on growth. A follow-up Changing Needs paper explored transmission mechanisms from economic growth to poverty reduction, identifying three main channels: job creation, the ‘general multiplier’ and social policy. In 2013, there was further analysis on ‘growth transmission mechanisms’, identifying the importance of focusing on productive sectors with the potential for substantial job creation. In 2014, an Inclusive and Transformational Growth paper centred on the concept of economic transformation; elements of its analysis then appeared in the growth diagnostic template.

From 2015, DFID began to develop sector strategies, recognising the need for more guidance on how to put its 2015 Economic Development Strategy Framework into practice. The Conceptual Framework on Agriculture defines DFID’s long-term objective as encouraging the majority of the rural poor to find work outside primary agricultural production.37 A policy framework on sustainable infrastructure from 2015 discussed DFID’s comparative advantages alongside the multilateral development banks as including flexible, politically astute technical assistance, mobilising private finance and investing directly in community-facing infrastructure for the poorest.38 It calls for scaling up of DFID’s investments on urbanisation and regional infrastructure.

Two other sector strategies – on sustainable cities and energy – have been developed but not yet published.39 The first stresses that urbanisation poses not just development challenges (such as the growth of slums and new forms of poverty and vulnerability) but also opportunities, as cities are engines of economic growth. It stresses the importance of secondary cities in reducing poverty.

Through these documents, DFID has become clearer about the core objective of its work. Achieving economic transformation by moving the poor into more productive work is identified as the primary mechanism for achieving poverty reduction and DFID’s preferred goal wherever circumstances permit. This emphasis on economic transformation is consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals and the African Union Agenda 2063. Beyond identifying broad sectors for engagement, the strategy offers relatively little practical guidance to country offices on how to achieve economic transformation, instead stressing the need for context-specific approaches based on in-country growth diagnostics.

Achieve transformation of economies towards higher levels of productivity through diversification with a focus on high value-added sectors.

We aspire that by 2063… economies are structurally transformed to create shared growth, decent jobs and economic opportunities for all.

There is a real opportunity for Africa to create jobs and promote inclusive economic transformation through domestic manufacturing and a commodity-based industrialisation process, capitalising on the continent’s resources and opportunities presented by the changes in the structure of global production.

Investing in incremental growth in incomes for the poor (‘holding pattern growth’) is an interim solution for alleviating poverty, until such time as structural economic change can be achieved. This is expressed most clearly in the Conceptual Framework for Agriculture. Moving poor people from traditional agricultural livelihoods into more productive employment is described as ‘stepping out’. While this takes place, the agriculture sector is key to inclusive growth, both through the promotion of commercial agriculture and agribusiness (‘stepping up’) and by raising incomes from small-scale farming (‘hanging in’). The need for balance across these objectives is not stressed in the 2017 Economic Development Strategy. However, we saw it reflected in the growth diagnostics and country portfolios in Tanzania and Zambia.

Overall, DFID’s approach to economic development has become clearer and more focused overtime. However, there are also novel elements in the 2017 strategy. It stresses the need for better and fairer trading rules – including the UK’s own trade policy after exiting the European Union – to help developing countries trade with the UK and the rest of the world. It calls for ‘patient capital’ investments to demonstrate the viability of commercial investment in low-income countries, so that DFID’s development capital investments can leverage much greater investment from the private sector. It also calls for building links between the City of London and local financial sectors in developing countries, to help local businesses raise finance in London. These are new policy initiatives that are not grounded in DFID’s past experience and will therefore open up new learning challenges for DFID.

Conclusion on strategy, research and learning

Over the past few years, there has been significant expansion of DFID’s knowledge and capacity on promoting economic growth. It has introduced the first in-depth sectoral diagnostic tool, which reflects on, and helps to build a common understanding of, the components of the economic development challenge. It has helped DFID to identify gaps and areas of weakness in its portfolio. These are being addressed through the development of new strategies and guidance, research programmes and centrally managed programmes. Its research programme is large and ambitious. While most of the research is yet to have a direct impact on programming, emerging results are being captured and shared, and used to inform strategy documents and the design of centrally managed programmes. However, DFID acknowledges that key aspects of how to promote economic growth and job creation remain unknown. DFID is beginning to use centrally managed programmes more strategically to supplement its country programmes, expand its delivery capacity and scale up its portfolio. Given past coordination problems between country offices and centrally managed programmes, the new programmes are being developed in a more consultative way and come with additional advisory resources, making it more likely that country offices will engage with them.

DFID’s thinking on how economic growth translates into poverty reduction through productivity improvements and job creation has become better articulated over successive strategies that reflect the available evidence and theoretical work. This adds up to a concerted effort to raise DFID’s knowledge and expertise on economic development and to articulate a clear strategy. It merits a green-amber score.

Are DFID’s country economic development portfolios informed by evidence?

In this section, we explore learning from the country office perspective, looking at how country portfolios are shaped by knowledge and evidence, at how learning is captured from programmes and at DFID’s progress on integrating value for money considerations into programme management. This section draws primarily on our three case study countries: Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia.

The impact of the inclusive growth diagnostic on country portfolios has so far been limited

The 2017 Economic Development Strategy places considerable weight on in-country growth diagnostics as the mechanism for identifying growth and opportunities for programming. The inclusive growth diagnostics were done in two stages: having assessed the context, country offices were asked to “propose a set of potential DFID interventions to unlock transformative investment and inclusive growth”.40 We therefore looked for evidence of country strategies and portfolios being adapted in response to diagnostic work.

In all three of our case study countries, the impact of the diagnostics on programming has so far been limited. There were a number of reasons for this. They were undertaken only a year after DFID had carried out another cross-country diagnostic exercise, the country poverty reduction diagnostic, to inform 2014 updates to its country operational plans. These were broader exercises, covering the whole country portfolio and involving the whole country team. They analysed constraints on inclusive growth, but without going into particular economic sectors. As the inclusive growth diagnostics came a short time afterwards and did not involve any additional research, they tended to reach broadly the same conclusions.41 The diagnostics were also out of sync with the programming cycle, coming after the scaling up of the economic development portfolio (2012-14), when funds had already been committed. For all these reasons, the common view among the stakeholders we spoke to was that the analysis served more to con rm existing choices rather than challenge them.

There was nonetheless some influence from the inclusive growth diagnostics on programming. DFID Zambia stated that, while its strategy was already focused on jobs, the analysis contributed to decisions to draw on two new centrally managed programmes on urban growth.42 DFID staff in Tanzania informed us that the diagnostic prompted them to reflect more on inclusivity and women’s empowerment, which influenced a new Dar Urban Jobs programme (still under design).43 All three offices agreed that the second part of the diagnostic exercise, which focused on identifying new programming options, was the weakest and least influential.

Some key informants at country level also noted a tension between a bottom-up diagnostic and the top-down priorities set by ministers. Some suggested that the conclusions emerging from the growth diagnostic were inevitably influenced by central priorities.

While the first-round inclusive growth diagnostics have so far had only a limited impact on programming, they were an important step in an ongoing process of building a deeper understanding of the constraints on growth in each country. We have seen that the new country business plans for all three countries (not yet published) reflected some of the conclusions from the country poverty reduction diagnostics, the inclusive growth diagnostics and other analyses. In addition, at the time of writing, the department is going through a process of reviewing its spending, in anticipation of budget reductions in some country programmes.44 DFID informs us that the inclusive growth diagnostics may help to guide that process by providing a basis for greater selectivity.

DFID’s country portfolios show varying ambition towards transformative growth

In the three case study countries, DFID’s analysis of the opportunities for transformative growth is clearest in Ethiopia, where conditions – including government policy – are most favourable, and its strategy is the most focused and coherent. In both Zambia and Tanzania, DFID identified a wide array of growth constraints, making it more difficult to be selective in its interventions. In both countries, it continues to invest most of its resources in agriculture, while making some experimental investments in transformative growth in other areas.

In Ethiopia, the diagnostic revealed potential for transformative growth in light manufacturing, given Ethiopia’s large reserves of low-cost labour. Through its Private Enterprise Programme Ethiopia (£70 million; 2013-20), DFID has chosen to invest in three value chains (cotton-textiles-garments, livestock- leather-apparel and horticulture) with the potential for job growth, particularly for women. All three value chains link back to the agriculture sector and therefore also have the potential to improve rural livelihoods. To support industrial growth, DFID Ethiopia is also participating in a new centrally managed programme, Invest Africa, designed to brand Africa as a global manufacturing base and link it with international buyers. This set of interventions therefore contributes both to transformative growth and to inclusion.

Box 9: DFID Private Enterprise Programme Ethiopia

The Private Enterprise Programme Ethiopia (£70 million; 2013-20) supports access to finance for poor households, small and medium-sized businesses (especially those owned and run by women), and larger enterprises through equity investment. It promotes productivity and growth in the horticulture, leather and textile sectors, in order to raise incomes and create jobs. It also supports investment climate reform.

The programme targets domestic value chains, from farmers through to end producers and exporters. Poor coordination between farmers and factories currently leads to losses in productivity. For instance, many textile businesses have had to set up their own cotton farms, as existing smallholders are unable to meet their quality requirements. There are similar problems in the horticulture and leather sectors. By targeting both smallholder farmers and companies with high employment-creation potential, especially for women, the programme has the potential to transform aspects of the Ethiopian economy in ways that benefit the poor.

The national context in Zambia is less favourable for widespread economic transformation and the DFID portfolio is less ambitious in this regard. The inclusive growth diagnostic analyses why Zambia’s dominant mining sector works against structural change (a combination of ‘Dutch disease’45 and the effect on elite incentives). It notes opportunities in commercial agriculture, small-scale manufacturing and services, but states that these are unlikely to generate significant employment. It concludes that economic transformation will occur through the gradual diversification of the economy, and that large numbers of rural poor will need support for a long time. Against this backdrop, DFID has chosen to focus most of its investments on agriculture, while making some smaller and more experimental investments in transformational growth. It is providing business support services and access to finance for small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises and helping to link them up with larger businesses. This includes working with South African supermarkets to increase their use of Zambian produce. It funds AgDevCo, a UK-based social impact investor (also funded from a centrally managed programme) that leverages private investment for agricultural enterprise and infrastructure. It is also working with new centrally managed programmes to develop the growth potential of Zambia’s cities, focusing on energy and other infrastructure.

The likes of the South African supermarket chains may be interested to use Zambian products for some political gain. But they’d rather get their products in from the traders they already have relationships with back at home. The Zambian producers, if they want to get in to these huge buying chains, need proper levels of capital. [Name of South African supermarket] have such advanced logistics networks so they’re not worried about Zambian products being cheaper to ship. They’re just worried about what products will actually sell on the shop floor to wealthier Zambians.

Tanzania has had the largest scale-up of the three, from £53 million in 2013-14 to £116 million in 2016-17, linked to a 2014 decision to terminate general budget support and redirect much of the funding into economic development. As a result, it has the most fragmented portfolio, with 17 bilateral programmes. In the past, DFID had a strong partnership with the government on economic development and contributed to several national programmes designed to improve the investment climate and raise agricultural productivity. From 2012, however, that partnership began to weaken, linked to corruption scandals and a waning consensus between government and donors on development policy. We found this inclusive growth diagnostic to be the least convincing of the three, with more limited analysis of data and a rather generic set of conclusions. It identified a large number of binding constraints on economic transformation, including the poor business environment, inadequate infrastructure, a lack of access to finance, low human capital (caused by poor education and high levels of malnutrition), weak firm competitiveness and growing climate change impacts. It concluded that, in the short term, inclusive growth was most likely in agriculture, with some potential for transformative growth in the oil and gas sector, light manufacturing and in urban centres.

DFID Tanzania has retained a large agricultural portfolio, with a shift over time from focusing on livelihoods towards agro-processing and value chains, including supporting regional markets for staple foods. Its agricultural portfolio is backed by investments in rural roads and land titling. To promote trade, DFID is helping to upgrade the main port at Dar es Salaam and to develop regional transport corridors by investing in preparatory work for large projects that will eventually be funded by other organisations such as the World Bank. It supports trade facilitation through the TradeMark East Africa programme, which is working to improve border management across the region so as to reduce the time and cost involved in trading across borders.

While the growth diagnostic identified the regulatory environment as a significant constraint on business development, earlier work in this area produced few results and has been discontinued, although work on modernising the tax system continues. DFID has a Financial Sector Deepening programme, to improve access to finance. It is now turning to a number of centrally managed programmes to support job creation, and developing a new Dar es Salaam Urban Jobs Programme, which will support various areas relevant to urban growth, including light manufacturing, solid waste management and childcare. DFID also set out to promote more local jobs in the oil and gas sector by supporting training on relevant skills, using an innovative approach. The fall in global prices has resulted in lower than expected investment into the sector, and the programme is now supporting skills development in other extractive industries, such as graphite.

Agriculture has to be the source of inclusive growth, given that 80% of people in the country work in the sector. However, banks are not giving loans for agricultural activities for various reasons. We are still engaging in peasant-traditional-level agriculture in this country. There is a complete lack of processing industries here.

Rural-urban migration is so high, with most people feeling they can’t make a living rurally in agricultural activities. But there aren’t available jobs in the city for unskilled, semi-literate young people.