DFID’s efforts to eliminate violence against women and girls

ICAI score

DFID has responded very actively to UK policy commitments on violence against women and girls (VAWG). It demonstrated global policy leadership through the 2014 Girl Summit and worked effectively with others in its campaign for the inclusion of VAWG in the Global Goals. It has supported international programmes to address female genital mutilation/cutting and child marriage. It has invested strongly in research and innovation to promote learning on what works. DFID country offices have significantly expanded their investments in VAWG, developing programmes that are of good quality but remain small in relation to the scale of the challenge.

DFID now needs to scale up its response by integrating VAWG into programming across a range of sectors, so as to achieve transformative impact. Learning how to deliver interventions at a scale large enough to make a real difference and encouraging others to programme at scale are the major challenges facing DFID in the coming period.

Executive Summary

The UK government has made a strong commitment to using the aid programme to tackle violence against women and girls (VAWG) in developing countries. The challenge is a daunting one. VAWG is deeply rooted in cultural norms and unequal power relations between women and men. One in three women around the world experiences intimate partner violence, and other forms of VAWG are also widespread. As well as being a violation of women’s fundamental human rights, VAWG has profound personal, social and economic consequences.

DFID has rapidly expanded its programming in these areas over the past five years. It now has 23 programmes dedicated to addressing VAWG with a total budget of £184 million, and more than 100 other programmes with one or more elements addressing VAWG. In this review, we explore how well DFID has translated ambitious policy commitments into effective programmes with the potential to make a real difference. We also examine DFID’s efforts to encourage others – both nationally and internationally – to tackle VAWG.

We have designated this a learning review because it examines a relatively new area of the aid programme where the evidence on what works is limited. It focuses on how DFID goes about building knowledge, testing new approaches and moving towards programming at scale. In particular, we explore three steps that are essential to achieving transformative impact in such a challenging area:

• Learning what works.

• Translating knowledge into credible programming.

• Influencing others.

DFID has positioned itself as a leading global investor in VAWG research

DFID has made a substantial commitment to learning what works in the prevention of VAWG. It has positioned itself as a leading global investor in VAWG research, engaging with some of the most influential researchers in the field. DFID-funded research programmes have identified knowledge gaps and are addressing them in a systematic way. In the next few years, they are likely to make a significant contribution to global knowledge. However, at present there is limited awareness of DFID funded research outside DFID, which means that the value of the investment may not be fully realised.

DFID has developed an overall ‘theory of change’ for VAWG prevention that is a fair reflection of current knowledge, but will need elaboration as that knowledge increases. DFID is progressively translating research findings into guidance for programming. However, DFID is not maximising learning from within its own portfolio, particularly on the key challenge of how to mainstream VAWG interventions into sectoral programmes.

DFID’s programming is innovative but remains small in scale

DFID is implementing a range of innovative programmes at both central and country levels. It is a major contributor to promising global programmes aimed at ending female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and child marriage. It is funding non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to pilot new approaches to VAWG prevention. In response to an earlier recommendation from the International Development Committee, much of its programming explores how to change social norms. Generally, we found DFID’s VAWG-focused programmes to be well designed and based on solid evidence and analysis. However, they remain small relative to the scale of the challenge.

Scaling up is the key challenge for DFID’s VAWG work

While this is a promising start, DFID will need to deliver results on a much larger scale across the full range of VAWG types if it is to achieve transformative impact. At present, DFID lacks clear strategies for scaling up its investments so as to draw on the specific context, problems, capacities and opportunities in each country. It is beginning to integrate VAWG interventions into its sectoral programmes. However, there is still a lack of understanding of what works at scale and how to mainstream VAWG initiatives without compromising their quality. The challenge now facing DFID is to continue to learn and innovate while scaling up successful interventions – both within its own programming and by demonstrating to others what works.

Scaling up is also the key value for money challenge in this portfolio. Stand-alone VAWG programmes will continue to be important for learning, but achieving value for money calls for a clear pathway for taking successful initiatives to scale. As it does so, DFID will need to invest more resources on collecting impact, expenditure and value for money data across its VAWG portfolio.

DFID has been a strong advocate for VAWG at the international level

At the global level, DFID has invested considerable effort in raising the profile of the VAWG agenda, with some success. The high-profile Girl Summit in 2014 helped to galvanise global campaigns against FGM/C and child marriage. Working with others, DFID also contributed to securing the inclusion of VAWG in the Global Goals. The stakeholders we consulted were in agreement that the UK’s strong commitment to the VAWG agenda had helped to mobilise political leadership and to build international momentum. DFID does not, however, have an explicit strategy for its VAWG influencing work nor does it systematically monitor the results, making it difficult to draw conclusions as to whether it has used its resources to best effect.

Having helped to raise the international profile of VAWG, the next challenge is to persuade other donors and partner countries to mainstream VAWG into their sectoral programmes. While DFID has worked closely with its multilateral partners to encourage them to focus on gender equality, it has not yet explored the potential for mainstreaming VAWG in multilateral sector programmes, such as health, education and water and sanitation. We found that DFID collaborates well with other UK government departments, including by bringing experience from its own programmes to joint challenges, such as tackling FGM/C within diaspora communities in the UK.

A strong start in a challenging area

We have given DFID a ‘green’ rating for its VAWG portfolio. This rating reflects DFID’s strong performance so far in building its knowledge from a low base and promoting this issue on the global stage. DFID’s systematic approach to identifying and filling evidence gaps stands as an example of best practice within the department.

When it comes to turning knowledge into credible programming, DFID has done reasonably well to date. Much of its programming is innovative and well designed. However, there are still difficult issues to resolve about how to turn a young portfolio into a large-scale, sustained engagement that can deliver transformative impact. Central to this is the need for a more considered approach to scaling up.

We make four recommendations, each of which is supported by one or more issues of concern that DFID will need to address:

Recommendation 1: Scaling up

DFID to explain how it plans to approach scaling up of successful VAWG interventions through centrally funded programmes, at country level and by working with other donors and agencies.

Issues of concern

• The small scale of DFID’s VAWG-focused programmes is not commensurate with the scale of the challenge.

• DFID does not yet have clear plans for scale up, including mainstreaming VAWG in sectoral programmes, either through its own interventions or its multilateral partners.

Recommendation 2: Learning

DFID to explain how it will step up its internal learning on VAWG and improve uptake of learning and evidence into the design and implementation of sectoral programmes.

Issue of concern

• DFID is not maximising learning from its own portfolio, particularly about how to mainstream VAWG interventions into sectoral programmes.

Recommendation 3: Learning

DFID to outline its plans to encourage uptake by external stakeholders of learning from the results of WhatWorks and other research.

Issue of concern

• Awareness of DFID’s WhatWorks and other external research is limited outside the department, so that the value from these global public goods may not be fully realised.

Recommendation 4: Data

DFID to set a path to including VAWG more fully in its data collection and measurement systems.

Issue of concern

• DFID does not systematically collect expenditure and value for money data for its VAWG work.

We also set out some longer-term challenges, or ‘learning frontiers’, that DFID and others need to grapple with if efforts to prevent VAWG are to have transformative impact.

Ending VAWG is a long-term challenge and this remains a young portfolio. We propose to return to it at a later date to assess whether these promising beginnings have been converted into real results.

Introduction

Purpose and scope of the review

Since 2010, the UK government has made a series of major policy commitments on tackling violence against women and girls (VAWG) internationally. The government’s Call to End Violence against Women and Girls1 includes pledges to address VAWG through the aid programme and has been regularly updated, including a new strategy for 2016-2020 published in March 2016.2 Since her appointment as International Development Secretary, Justine Greening has repeated her determination in speeches and articles to place ending VAWG “at the heart of UK development”.3

This review assesses how well the Department for International Development (DFID) has responded to these ambitious policy commitments in a new and challenging area for UK development assistance. We look first at DFID’s efforts to assemble evidence of what works and invest in research and innovation to fill knowledge gaps. Second, we review how well this emerging knowledge has been turned into a credible portfolio of programmes with the potential to make a real difference. Third, recognising that it will take more than UK aid to address a problem of this scale and complexity, we look at DFID’s efforts to promote greater engagement at the international level and at its collaboration with other UK government departments.

This is a learning review. VAWG is a new area of the aid programme, where it is too early to assess the impact of the work. The focus is therefore on how DFID goes about learning about what works to end VAWG and how well it translates emerging knowledge into relevant and coherent programming. DFID’s VAWG research and programming are still at an early stage, although they are able to draw on research in high-income countries and other donors’ efforts over several decades. As well as reviewing DFID’s performance to date, we draw attention to issues that DFID should address in taking forward its VAWG portfolio and areas where DFID could focus its learning in the future – which we call ‘learning frontiers’.

ICAI learning reviews examine new or recent challenges for the UK aid programme. The focus is on knowledge generation and the translation of learning into credible programming. While learning reviews do not attempt to assess impact, they offer a critical assessment of progress to date and whether programmes have the potential to produce transformative results. Through our learning reviews, we recognise that the generation and use of evidence are central to delivering development impact.

Other types of ICAI reviews include performance reviews, which probe the efficiency and effectiveness of UK aid delivery, and impact reviews, which explore the results of UK aid.

A key theme for this review is how DFID moves from small, experimental programmes towards programming on a scale that could make a real impact on such a widespread problem. This means looking not just at programmes that tackle VAWG directly, but also at how the issue is taken up in programming in other sectors, such as health, education, economic development or water and sanitation. We are also interested in how aid programmes can challenge deeply rooted social norms and in particular, the accepted rules of behaviour within communities towards women and girls that contribute to making violence acceptable. Our review questions are set out in full in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Learning: how effectively is DFID harnessing and applying learning in the development and scale up of VAWG interventions? | • How effectively do VAWG programmes make use of available empirical evidence and contextual analysis? • How effectively is DFID identifying and addressing gaps in the evidence? • How effective is DFID’s approach to piloting, replication and scale up? |

| 2. Relevance: to what extent is DFID’s VAWG portfolio relevant, coherent and plausible? | • How relevant is DFID’s VAWG programming to the needs and preferences of survivors and intended beneficiaries? • How plausible are DFID’s theories of change for their respective objectives and contexts? • To what extent is DFID’s programming designed at a scale and intensity likely to achieve sustainable impact and deliver value for money? |

| 3. Influence: how effectively has DFID influenced wider efforts to tackle VAWG at the international and national levels? | • How effective has DFID been at securing and following up on international commitments on VAWG? • How effectively has DFID coordinated with other UK government departments in tackling VAWG at the international level? • How effectively is DFID linking up and aligning its VAWG programmes with its international influencing activities? |

Our review covers DFID’s portfolio of VAWG programmes and activities since 2010. It includes:

• Programmes designed specifically to tackle VAWG (‘VAWG-focused programmes’). There are 23 of these with a budget of £184 million.

• Wider programmes which include at least one element to address VAWG (‘VAWG-component programmes’). There are 104 of these, but DFID does not collect expenditure data on the VAWG elements. They range from contributions to international NGOs that work on VAWG alongside other issues, through to small components in larger sectoral programmes. An example of this is a £185 million health programme in the Democratic Republic of Congo that includes a small component to develop service standards for treating survivors of sexual violence in health clinics.

• DFID’s international influencing and work with other UK government departments.

We have also reviewed DFID’s response to the recommendations of a 2013 International Development Committee report on DFID’s VAWG programming.4

Action against VAWG in the UK is outside our scope, as is the work of DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) on VAWG in conflict and humanitarian emergencies, which has been covered by a House of Lords inquiry published in April 2016.5

This review does not assess support services for survivors of VAWG in detail, as this topic was covered in a previous ICAI review of DFID’s security and justice portfolio. 6However, we recognise the important links across all these areas of work.

Tackling violence against women and girls

VAWG is a vast but preventable problem

VAWG is a global epidemic with profound consequences. World Health Organisation figures show that more than a third of women in Africa, South Asia and the Middle East suffer from intimate partner violence at some stage in their lives.7 (In wealthy countries, the figure is not much better, at a quarter.) Across the countries where DFID works, VAWG takes multiple forms including: female infanticide, female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), child, early and forced marriage (CEFM), trafficking, sexual assault, sexual harassment, sexual exploitation, domestic abuse and abuse of widows. Each form raises distinct challenges. They all involve acute suffering and are a fundamental denial of women’s human rights and social and economic opportunities. They are driven by the abuse of power by men and the inequality of women and men in the public and private spheres.8

VAWG is not just a violation of the rights of individual women; it is also a problem with serious consequences for society at large. The costs of VAWG are estimated at between 1 and 2% of national income in developing countries.9 In Vietnam, a forthcoming DFID funded publication concludes that VAWG related absenteeism from the workplace costs in excess of 1% of national income.10

VAWG is a deeply rooted problem that will be very difficult to overcome. Yet there are encouraging signs that it can be prevented. The most promising approaches are multi-sectoral in nature and work at both national and local levels. Box 2 sets out some recent research conclusions.

In November 2014, The Lancet published a series of articles detailing how VAWG can be prevented. Reviewing the latest evidence, the authors showed that, around the world, increasing resources are devoted to supporting the victims of VAWG, but that not enough is being done to prevent violence in the first place. While there are studies suggesting that preventive interventions can make a significant difference, there are still gaps in the evidence base requiring further research. The authors summarised some of the characteristics of promising approaches: they should involve multiple sectors at multiple levels, challenge the acceptability of violence while addressing underlying risk factors, and engage with communities as a whole – including men.

The authors proposed that leaders and policy makers commit to five actions:

• Show leadership – recognise the problem and allocate resources.

• Create equality – develop and enforce laws, implement policies and strengthen capacity to address VAWG and promote gender equality.

• Change norms – invest in violence prevention programming to promote women’s empowerment and change social norms relating to VAWG.

• Work across sectors – develop a coordinated, multi-sectoral response.

• Invest in research and programming – to learn how best to prevent and respond to VAWG.

DFID’s engagement on VAWG

The UK government’s commitment to addressing VAWG, both domestically and internationally, has grown steadily in recent years through a range of policy statements. It has built on the Home Secretary’s 2010 Call to End Violence against Women and Girls,11 which has been regularly updated. DFID’s 2011 Strategic Vision for Girls and Women included four pillars for action, one of which was to ‘prevent violence against women and girls’.12 DFID’s Business Plan 2012-2015 identified VAWG as a priority area for the first time and committed DFID to developing new and innovative approaches for its prevention. These efforts are underpinned by the UK Government’s wider policy commitment.

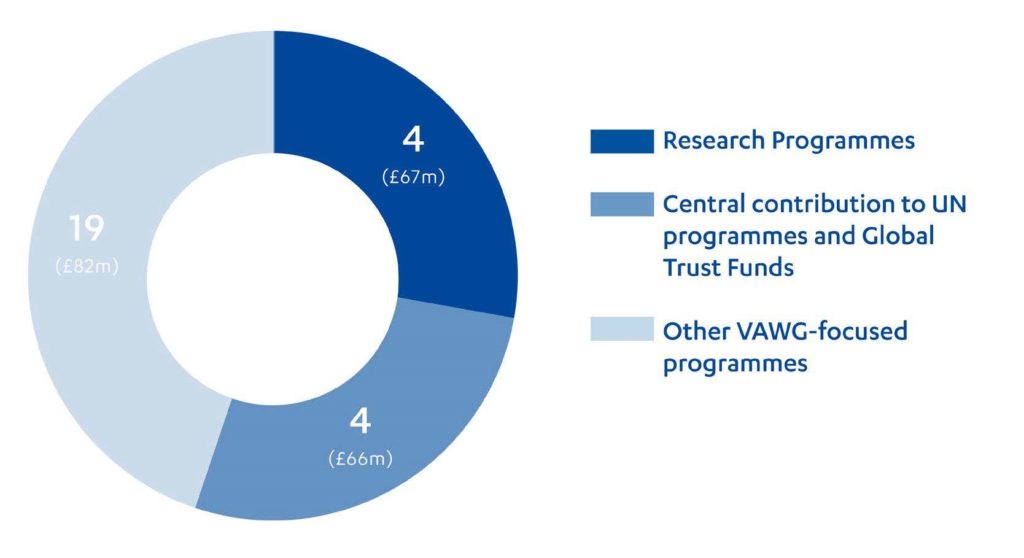

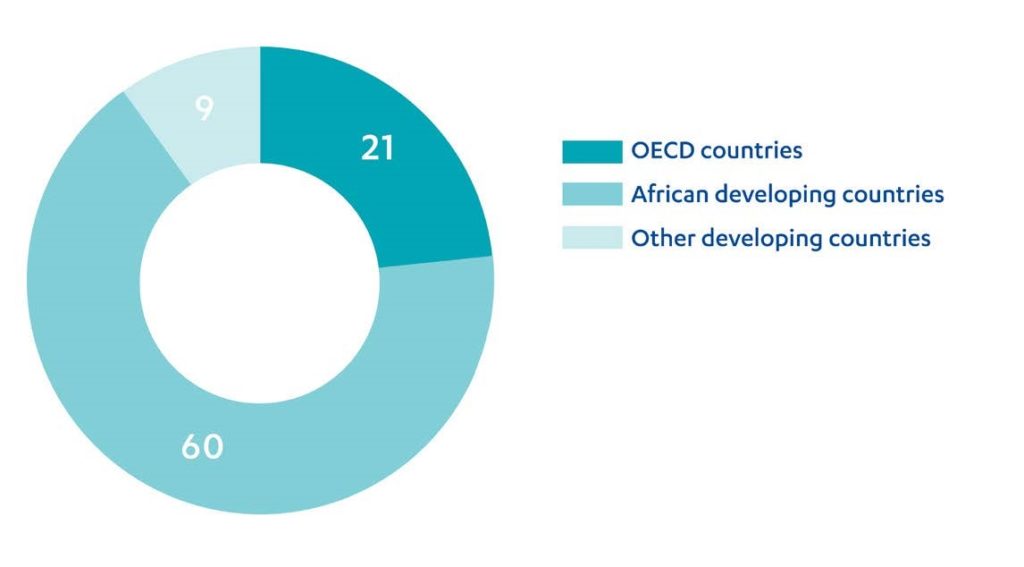

In response to these commitments, DFID has substantially expanded its programming on VAWG, with expenditure on VAWG-focused programmes rising from £20 million in 2012 to £184 million in 2015. It has a number of centrally managed programmes, including £52 million in contributions to United Nations programmes on FGM/C and CEFM. It is spending £67 million on four research programmes, provides grants to a number of civil society organisations and has contributed £6 million to the UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women, which tests innovative approaches. At the country level, DFID has 73 programmes that relate to VAWG (not counting VAWG in conflict and humanitarian contexts, which is outside our scope). Of these, 19 programmes are dedicated to VAWG, with a combined budget of £82 million, while the remainder are wider programmes with a VAWG-component (see Figure 2). To provide context for the reader, Box 3 introduces five of these programmes and how they operate, drawn from our desk reviews.

Figure 2: Summary of DFID’s VAWG programming

DFID’s VAWG programmes combine four main types of intervention: engaging with national policies and institutions; changing social norms; empowering women and girls; and providing support services to survivors. Most individual programmes combine two or more of these elements.

DFID’s VAWG programmes include:

• An African regional campaign on FGM/C run by the United Nations Population Fund and Unicef, to which DFID is the largest donor (£35 million contribution over five years). It contains a wide range of activities, including encouraging governments to address the issue and individual communities to formally abandon the practice.

• A programme that aims to reduce VAWG in South Africa through national policy development and leadership, evidence-based advocacy, school-based social mobilisation and community empowerment (£3.8 million over three years).

• A ‘voice and accountability’ programme in Pakistan, which works with a network of local organisations to strengthen the opportunities for citizens, and in particular women, to engage in local governance. While not exclusively about VAWG, it explores the links between VAWG and other aspects of women’s equality (£34.5 million over five years).

• A project that aims to empower Rwandan girls aged 12 and above. It provides them with assistance on health, social and economic issues while promoting reduced tolerance for VAWG. It also promotes girl-focused national policies (£6.5 million over five years).

• A programme that works with marginalised populations, including dalits, women and other excluded groups across seven Indian states, reaching up to 9 million people. It works by strengthening civil society organisations and community groups. It has a strong focus on women, including access to justice on VAWG, and engages with communities, including men, leaders and perpetrators of violence (£28.2 million over eight years, with five years of operational activity).

Our methodology

Our methodology for this review consists of five main components:

i. A literature review drawing mainly on existing syntheses of research.

ii. A strategic review of DFID’s VAWG policy commitments and its efforts to build knowledge on what works, and to translate this into strategies and guidance. We undertook an updated mapping of the portfolio, a review of DFID’s approach to value for money and an assessment of the treatment of VAWG in country strategies.

iii. Desk reviews of a sample of 23 of DFID’s VAWG programmes, including global, regional and national programmes and two grants to international NGOs, with total budgets of £806 million. The sample covers a third of the programmes we identified as of most interest to this review.

iv. Country case studies of VAWG programming in Ethiopia and India, to explore relevance, quality and links with programming in related areas such as health, education and livelihoods. In each country, we interviewed a wide range of stakeholders and visited a sample of implementation sites. Ethiopia and India were selected because of their high density of VAWG programming, their interaction with DFID’s international influencing work (Ethiopia) and the strength of research and civil society work (India). The two countries are not necessarily representative of the portfolio as a whole, but they yielded useful insights to complement other data sources.

v. A review of DFID’s international influencing work. We chose to focus on DFID’s support for two major international events, the agreement of the Global Goals in 2015 and the London Girl Summit in 2014. Both were significant attempts to advance the profile of VAWG in the international policy agenda. We checked DFID’s claims about the results of its influencing efforts against feedback from stakeholders and other evidence in the public domain.

We undertook 70 interviews including 24 with DFID staff, 7 with other government departments, 15 with donors and 15 with academic researchers. More detail on our methodology is provided in Annex 1. Both our methodology and this report were independently peer reviewed, and the methodology can be read in full in our Approach Paper on the ICAI website.

As a learning review of a relatively new portfolio, our focus was on the relevance and plausibility of DFID’s VAWG programming. We excluded some aspects of DFID’s portfolio, particularly VAWG in conflict and humanitarian emergencies. Our review of DFID’s influencing work was constrained by DFID’s lack of a system for monitoring its own influencing activities and the fact that many of these activities were necessarily confidential. We were therefore able to reach only broad conclusions about DFID’s contribution to international processes. Finally, evidence on the value for money of DFID VAWG programmes is currently limited, despite growing interest in this area from DFID. We were not able to make comparisons on this between different programmes from the available data.

Building evidence on what works

Our review questions were based around three elements. Each is key to building a credible portfolio of programmes in a relatively new area with the potential for transformative impact:

• Building evidence on what works.

• Developing a credible portfolio of programmes.

• Working with others to achieve large-scale impact.

In this chapter, we explore the progress that has been made to date in these three areas and the challenges we see ahead.

Building evidence on what works

DFID has positioned itself as a leading global investor in VAWG research

Until recently, most of the available research on VAWG came from high-income countries. In recent years, DFID has made substantial investments in research on VAWG in developing countries, positioning itself as a leading global investor in the field. Its most substantial commitment is to the £25 million ‘WhatWorks’ programme (2013-2019),13 which focuses primarily on the prevention of intimate partner violence, non- partner sexual violence and child abuse. Working on a larger scale than would be possible without the support of a major donor, the WhatWorks consortium includes some of the most widely cited researchers in the field. It also includes grants to NGOs to test new ideas for VAWG programming. No other donor has invested comparable resources into VAWG research. In our interviews with other donors and NGOs, those who were aware of WhatWorks gave feedback that this is a highly respected initiative with the potential to make a major contribution to knowledge in the field.

Other DFID funded research programmes include the Global Girls Research Initiative, 2014-2024 (£31 million), a long-term study which aims to generate new evidence on effective approaches to helping adolescent girls from poor backgrounds to escape poverty, including through addressing violence. There are also smaller research programmes on FGM/C (£8 million for a programme implemented by the international NGO Population Council) and CEFM (£3 million). The four research programmes total £67 million, which is a significant investment in knowledge.

The research has already highlighted a range of useful learning about VAWG prevention. For example, it has found that advocacy and media campaigns are unlikely in isolation to bring about social norm change, which has implications for some of DFID’s older programming. It has shown that the most successful interventions are likely to be multi-sectoral, including health, education, economic empowerment and other areas. It has highlighted the value of community mobilisation, women’s empowerment and gender equality education (see Box 5 for more lessons).

The DFID-funded ‘WhatWorks’ research programme has set out to identify and address gaps in the evidence on VAWG prevention. It began by producing a range of synthesis reports on the current state of research.

Some of the lessons include the need to:

• Address power and gender inequality as structural roots of VAWG.

• Integrate VAWG across multiple sectors (including health, education, economic empowerment and water and sanitation) and at multiple levels (national, local).

• Address underlying drivers of VAWG, particularly social norms that make VAWG acceptable and notions of masculinity and poverty.

• Support the development of new skills, including in communications and conflict resolution.

• Promote engagement with all community members.

• Integrate violence prevention into existing development platforms.

The research programmes began by assessing the state of knowledge in the field, and have then proceeded to fill the evidence gaps in a structured way. For example, relatively little is known about how to achieve change in social norms – that is, the rules of behaviour that are considered acceptable in a group or society and which play a major role in sanctioning or minimising VAWG. DFID’s research has already highlighted the importance of engaging with ‘reference groups’ (including peer groups, families and religious leaders), who have a strong influence on social norms and the preferences and attitudes of individuals. Drawing on these early findings, DFID recently published new guidance on social norm change around VAWG.14

The research has highlighted the importance of working with men and boys (see Box 6). Twenty out of the 23 programmes we reviewed showed evidence of this. DFID’s research has also identified knowledge gaps on women’s lifetime experiences of VAWG, from birth through to old age, and how different forms of VAWG interconnect. Research from high-income countries suggests strong links between violence experienced in childhood and adulthood, for both perpetrators and survivors. CEFM is also associated with high levels of domestic violence. There is little research as yet into the efficacy of education for young people about what equal and respectful relationships look like.

The major research activities are still at a relatively early stage. The FGM/C and CEFM research programmes were both initiated in 2015. The CEFM research programme has yet to formally start as the main implementation phase of the programme was only launched in March 2016. WhatWorks started in 2013 and has set up 26 research projects in 17 countries, but these have yet to deliver results and innovation pilots have only recently started. Substantial new results are still two to five years away for these programmes. These will have the potential to inform DFID’s own programming and influence other actors in the field. Based on the level of investment, the quality of researchers and the range of issues covered, this seems to be a very credible set of research programmes which give DFID a global leadership role in this area.

Working with men and boys to prevent VAWG is a contested area. The literature stresses that, with men occupying positions of power at all levels of society, it is their attitudes and behaviours that must change if VAWG is to end. However, some commentators are concerned that working with men might divert resources from women-only and women-focused programmes and services.

DFID’s guidance promotes working with men and boys, but cautions that this might inadvertently reinforce unequal power relations unless programmes remain accountable to women and girls. It suggests that interventions challenging gender roles by promoting alternative versions of masculinity and working to transform unequal power relations between women and men are more effective than those that overtly target violent behaviour. Working with perpetrators, however, has helped to expand knowledge, which in turn has informed prevention work.

All but three of the 23 DFID programmes we reviewed were engaging with men in some way, mostly as a core activity. Examples include:

• India – Poorest Areas Civil Society Programme: this aims at social mobilisation of communities and engages strongly with men, leaders and perpetrators of violence.

• Pakistan – Aawaz Voice and Accountability Programme: men participate alongside women in awareness-raising sessions and ‘change agent’ training on participation in public spaces and political processes and women’s right to freedom from violence.

• Sudan – Free of FGC: local partners facilitate community discussions on female genital cutting (FGC), led by village chiefs, members of village councils, religious leaders, health-care providers and other influential community members (and including younger generations).

DFID’s overall theory of change on VAWG is credible but will require updating

DFID has developed a plausible theory of change governing its overall approach to VAWG (attached as Annex 3).15 It offers programme designers a structured way of critically thinking about the VAWG challenge and options for tackling it. It was developed in consultation with civil society organisations and other stakeholders and published in June 2012. It includes a problem statement, barriers to progress and desired results, but is not specific to any particular form of VAWG. In our interviews with DFID staff and our programme reviews, we found that it is widely referenced and used by DFID staff as a starting point for developing programmes in specific country contexts.

The theory of change pre-dates the WhatWorks programme, but is broadly consistent with the current state of knowledge. However, there is still much to be learnt about VAWG prevention and DFID recognises that the theory of change will need to be updated as new evidence becomes available. There are some acknowledged shortcomings in the theory of change, including the implicit assumption that change occurs continuously, without setbacks and reversals. Greater clarity is also needed about how to address perpetrators of violence and about the role of promoting equal and respectful relationships in ending VAWG.

DFID has actively promoted internal learning about VAWG

DFID has a range of mechanisms for sharing VAWG knowledge internally. The central VAWG team supports the VAWG policy agenda, manages external relationships and supports country teams. An external VAWG Help Desk has been established to provide analysis and advice to country programmes and others and which also produces a quarterly research digest. Between its establishment in May 2013 and November 2015, the Help Desk handled 95 enquiries, of which 34 were from DFID country offices. While not all countries have used the service, it has provided a useful source of additional VAWG expertise, including on specific countries and themes, such as child sexual abuse, working with men and boys and intimate partner violence. The Help Desk is also available to other government departments and has been accessed in particular by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, the Stabilisation Unit and the Home Office.

DFID has been translating the available evidence into guidance notes to make it more accessible to country teams and to help integrate VAWG into wider programmes. ‘How To’ notes have been created for addressing VAWG in the health, education, economic development and security and justice sectors and, most recently, on achieving social norm change. More than 5,000 people accessed these resources on the external website in 2015.16 Similar guidance is also available for the water, sanitation and hygiene sector.17 Our interviews with DFID staff and review of DFID documents suggested that the ‘How To’ notes are being used by DFID country staff to help guide the design of programmes.

DFID has established communities of practice for VAWG and for CEFM and FGM/C. The former had 134 members in January 2016, including head office staff, heads of country offices and country-based staff, primarily advisers. They provide an environment in which specialists and non-specialists on VAWG issues can interact. The groups hold virtual meetings regularly and share resources and insights. Learning is also facilitated by work within advisory groups (especially among the social development cadre) and through the rotation of advisers between head office and country programmes.

A key aspect of a learning portfolio is openness among staff to new knowledge. During our interviews with DFID staff in headquarters and country offices, we encountered a high level of awareness of current research among the DFID staff and a willingness to engage with its findings. We found good examples in our desk reviews and country visits of staff drawing on research in programme design, especially for VAWG-focused programmes.

DFID still has some way to go on building knowledge on VAWG for non-specialists. While the larger subject of gender equality has been mainstreamed fairly effectively across the department, including in results frameworks and staff training, VAWG remains an emerging area. In India, interviews with programme staff who were not VAWG specialists demonstrated good knowledge and awareness of VAWG issues. In Ethiopia, however, programme staff were more reliant on social development advisers for technical support. Yet, importantly, social development advisers have limited time to engage in depth with sectoral programmes. As we suggest below, one of the pathways to scaling up impact is to incorporate VAWG interventions into programming in other sectors. To accomplish this, DFID will need to provide more help on VAWG for non-specialists.

DFID is not as focused on learning from its own VAWG portfolio

There is limited evidence that DFID is systematically capturing lessons from its own VAWG programmes and sharing them across countries. At this early stage, much of its programming is experimental in nature, designed to test new approaches in different contexts. It should be accompanied by an active process of drawing lessons that could be applied more broadly. For VAWG-focused programmes, DFID could do more to build continuous innovation into programme designs. We did not see evidence of DFID trying out different interventions in different contexts and adjusting quickly in response to early evidence of what works.

The evaluation function in DFID is decentralised to country offices, which make their own decisions on how best to use their limited evaluation resources. This means that there is no overarching evaluation strategy for the VAWG portfolio. While there are a number of evaluations planned in the coming years, they are not necessarily focused on addressing knowledge gaps so as to inform the development of the VAWG portfolio as a whole. A stronger role for the central VAWG team in the planning of evaluations and the dissemination of results would enhance learning.

Some of the planned evaluations will be randomised control trials. We encountered a lively debate about the value of these in the VAWG portfolio (see Box 7). Although the number of randomised control trials available so far is limited, they are relied upon extensively as a source of rigorous evidence. A number of stakeholders whom we interviewed, however, suggested they were less appropriate for measuring the results of experimental programmes, which need to be delivered in a flexible manner.

Randomised control trials are considered by some to be the gold standard in evaluation practice. They offer robust evidence of attribution – that is, whether an intervention is really the cause of a claimed result.

The relatively few randomised control trials globally that have been carried out in the VAWG area have been highly influential, as demonstrated by the WhatWorks evidence reviews. Yet some interviewees argued that DFID puts too much emphasis on this kind of trial. In a complex field such as VAWG, results may be linked to the quality of implementation, which calls for different assessment methods. Furthermore, randomised control trials take a long time to generate results and require a hands-off approach during implementation. This works against in-programme experimentation and active learning.

Our view is that, in a relatively young portfolio like VAWG with many small, innovative programmes, there is a good case for lighter assessment methods that generate learning quickly and at low cost to support flexible and adaptive programming. However, as the portfolio matures, there will be a need to identify effective VAWG interventions that can be scaled up by building them into sector programmes, including those funded by partner countries and other donors. Randomised control trials will play an important role in proving the value of these interventions and persuading others to take them on.

Challenges ahead on generating and applying learning

DFID has embarked on an ambitious knowledge journey in this complex field. It has made a significant commitment to generating new research, engaging with some of the leading researchers in the field. It has been systematic in identifying knowledge gaps and putting in place a programme of research and innovation to fill them. While the research is still at an early stage, emerging results have been captured in internal guidance for sharing across countries and departments. This represents a strong example of how to develop research programmes and apply knowledge to respond to a new policy priority.

It is too early to see the uptake of evidence from the new research initiatives into operational programmes. Over the next few years, however, DFID’s research projects, pilots and internal evaluations will generate a wealth of new knowledge. Turning this into programming at scale and with impact will be a major challenge, requiring new programme designs and more sophisticated theories of change. Having positioned itself as a global leader on funding VAWG research, DFID will need to focus on disseminating its research results to help guide the actions of its own and others’ programme managers.

The major challenges that we see ahead for DFID over the next five years in the area of knowledge generation and application are:

• Assimilating the learning from a substantial volume of research.

• Generating more learning from DFID programmes.

• Updating and elaborating theories of change in the light of new research.

• Improving the dissemination of research, which also provides opportunities for building partnerships and widening ownership.

• Developing results measurement processes and indicators that are effective in the VAWG area.

• Generating the next level of questions and continuing to learn.

Building a credible portfolio of programmes

DFID country strategies are increasingly addressing VAWG

Since the Secretary of State signalled the UK’s commitment to tackling VAWG through the aid programme, DFID country programmes have significantly increased their engagement on the issue. We reviewed 27 of DFID’s Country Operational Plans, comparing the focus on VAWG analysis and programming in 2011/12 to the 2013/14 updates. There was evidence of increased analysis and commitments on VAWG in 19 of the countries, leading to a range of new initiatives and programmes:

• Setting VAWG as a strategic priority in the Afghanistan programme with a commitment to developing new programmes and better tracking of results for girls and women.

• Establishing new VAWG programmes in Ghana and strengthening gender capacity in the country office.

• Increased programming at sub-national level in Mozambique to reduce violence against girls, including by working with civil society and developing a new economic programme to reduce gender inequality.

• A new programme empowering women to address VAWG in Pakistan, linked to analysis of the multiple forms of discrimination driving VAWG and underpinned by enhanced gender-disaggregated data.

• Addressing VAWG in the education and reproductive health programmes in Tanzania, including strengthening of school management and leadership and training health workers to support women affected by VAWG.

Strategic thinking at the country level is key to the future development of the VAWG portfolio. In particular, DFID needs to work out how to move from small-scale programming to interventions at the scale required for transformative impact. The pathway to scale is likely to be different in each country, depending on the nature of the VAWG challenge, the available entry points and the capacity of local partners. We have little evidence to date that DFID approaches this challenge systematically in its priority countries. However, recent developments in the Malawi programme are a good example of how this can be done in a strategic way (see Box 8).

Following the arrival of a new Head of Office in 2014, DFID Malawi is providing an example of how to scale up and mainstream its response to VAWG across all its programmes. Initial contextual and data analysis was undertaken by the VAWG Help Desk, which then sent a consultant to help DFID Malawi develop a country- level theory of change, reflecting the local context and the opportunities within its sector programmes.

In addition to a focus on gender-based violence in its justice programme, DFID Malawi is working to develop VAWG components in education, resilience, savings and loans, and health and family planning programmes. The team are finding the ‘How To’ notes helpful in developing sectoral approaches. Programme design will have an initial emphasis on ‘do no harm’, moving to an increasing focus on changing social norms and prevention. Key challenges ahead include providing VAWG expertise for the design process for sectoral programmes and not overloading the delivery agents for key programmes at community level.

DFID has moved quickly to build its VAWG portfolio drawing on its theory of change

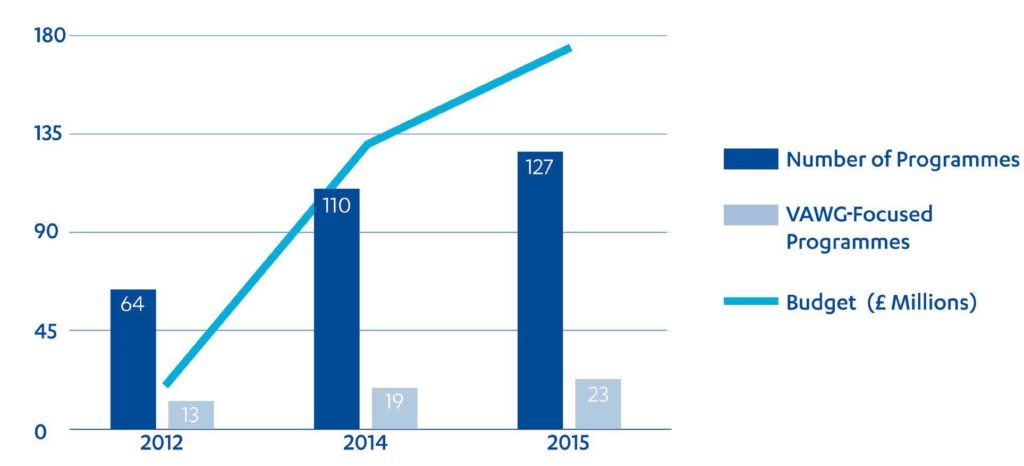

DFID’s VAWG portfolio expanded rapidly between 2012 and 2014, at a period when the UK aid programme was increasing to meet the 0.7% target. A DFID mapping exercise in 2014 identified 110 VAWG programmes in 2014 – up from 64 in 2012.18 Seventeen new programmes were added in 2015 (including 11 in conflict and humanitarian contexts). This represents a slower rate of expansion, which the DFID VAWG team described as a ‘consolidation phase’. Of programmes focused exclusively on VAWG, the total budget rose from £20 million in 2012 to an estimated £184 million in 2015.19

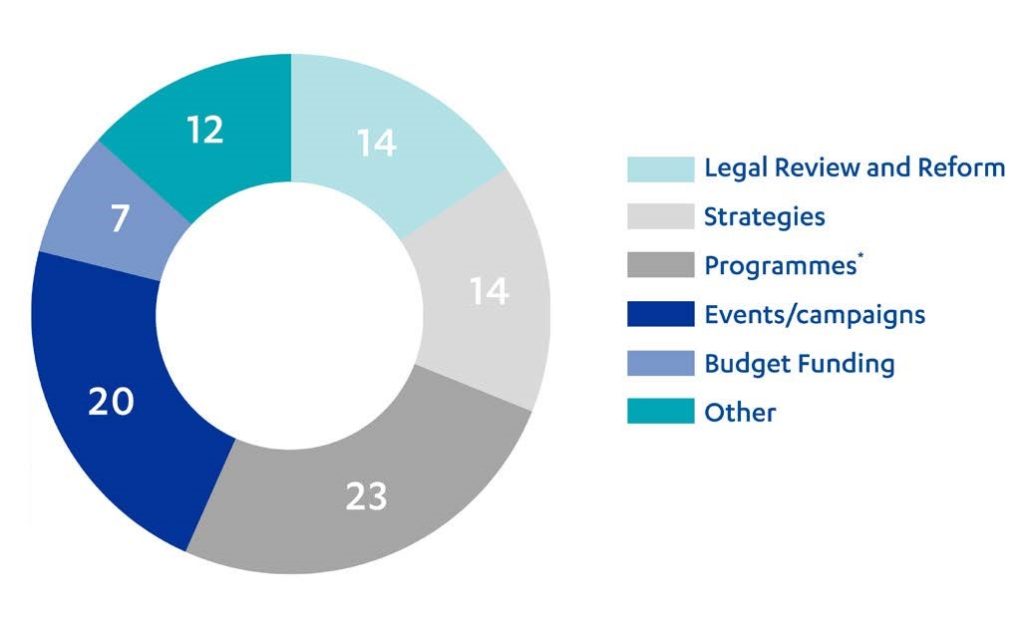

Figure 3: Summary of DFID’s VAWG programming

DFID is not as focused on learning from its own VAWG portfolio

The theory of change sets out four types of intervention:

• Building political will and legal and institutional capacity.

• Changing social norms, including behaviours and practices.

• Supporting the empowerment of women and girls.

• Strengthening and expanding specialist women’s services.

This has proved to be a useful framework for DFID staff in classifying VAWG interventions. DFID country offices have taken and adapted it to their specific programmes. For example, the Rwanda programme for girls aged 12 and above has a theory of change based on girls economic and social empowerment. A programme addressing gender-based violence in South Africa has a theory of change focused on addressing the root causes of VAWG, including changing belief systems, attitudes and behaviours towards women.

The portfolio shows a good balance across the four intervention types, with most programmes including two or more of these interventions. Work on social norm change was previously under-represented in the DFID portfolio. As recommended by the International Development Committee, the focus on social norm change has increased markedly, from 23% of programmes in 2012 to 63% at the time of the portfolio mapping exercise in 2014. A strong example of the social norm approach is the Nigeria Voices for Change programme (see Box 9).

The ‘Voices for Change’ programme in Nigeria (£41 million, 2011-17) aims to change social norms towards women and girls, including those relevant to VAWG. It raises awareness among men and women through social media, branding and the use of ‘virtual safe spaces’. It also aims to build civil society capacity to collaborate on action to support gender equity, including advocacy for policies and legislation to protect women and girls against violence.

We found that the programme design was informed by strong contextual analysis and wide consultations, including with young people. It also drew on a thorough assessment of the empirical evidence supporting the proposed interventions. The limited evidence about how social media and new communication technologies can be used to deliver social change is acknowledged, and the programme explicitly sets out to generate new learning in this area. In an important innovation, the programme has developed a new tool for measuring social norm change, drawing on international expertise. This has been widely shared across DFID and externally.

The VAWG-focused programmes we reviewed were well-designed with good use of contextual analysis, strong links to the theory of change and adequate VAWG indicators. However, four of our 16 reviews of VAWG- component programmes did not include VAWG specifically in their theories of change, which creates the risk that the VAWG elements of these programmes will not be designed or monitored appropriately.

We looked at the balance of the portfolio across the different types of VAWG, but were not able to reach any firm conclusion. FGM/C or CEFM were addressed by 9 of our 23 desk review programmes, as well as by a number of central programmes. Only four of the programmes specified in their design documents that they were addressing intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence, which are amongst the most prevalent forms of VAWG. In 12 of the programmes the documentation was not specific about the types of VAWG being addressed. This suggests that interventions may not be covering the full range of VAWG or being appropriately tailored to the prevention of particular types of VAWG. A number of stakeholders, including DFID staff, multilateral donors and civil society organisations, stressed the point that intimate partner violence should not be neglected and is likely to require specific types of intervention.

Women’s voices are not being heard adequately

Research has demonstrated the important role of women’s rights organisations in bringing about policy change on VAWG.20 One route to scaling up VAWG prevention is strengthening grassroots women’s rights organisations and networks. However, the 2014 mapping study found that DFID’s programmes had limited focus on building the capacity of such organisations.21 DFID has made contributions of £8 million to the Amplify Change programme and £6 million to the United Nations Trust Fund to End Violence against Women. We support the views of a range of stakeholders from other government departments, donors, civil society organisations and academic institutions that this remains a relatively neglected area in DFID’s programming.

There is mixed evidence as to the extent and quality of beneficiary engagement in DFID’s VAWG programming. Consultation with beneficiaries was mentioned in only 5 of the 23 business cases that we reviewed, and only 2 of our desk reviews showed evidence of beneficiaries’ involvement in the governance of the programmes. We did, however, see good examples of beneficiary engagement in the Girl Effect programme in Ethiopia, where in-depth consultations have shaped programme design and content, and the Poorest Areas Civil Society Programme in India, where women and other excluded groups affected by violence play a leadership role in the organisations supported under the programme. Given this mixed evidence, DFID should assess whether there is potential to strengthen the role of women, and particularly survivors, in the design, governance and monitoring of VAWG programmes, to make them more responsive to the needs of the intended beneficiaries, giving due consideration to the needs of confidentiality and safety.

Effective management of DFID’s VAWG portfolio requires better information

Despite its strong policy commitment to VAWG, DFID has not as yet set itself global targets on VAWG. DFID’s Results Framework includes a commitment to providing ten million women and girls with access to improved security and justice services,22 but there is no specific indicator on VAWG. While we do not think that a numerical beneficiary target is appropriate for VAWG, we are concerned that the absence of any kind of overarching target on the scale of programming has led to a lack of attention to collecting basic management information about the portfolio.

DFID does not routinely track its expenditure on VAWG programming, especially for VAWG-component programmes. It commissioned a mapping exercise in 2014 that produced an estimate of programming commitments, but this has not been kept up to date.

As the portfolio matures, DFID will need to become more rigorous in its data capture. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development is already pushing ahead in this area and will be introducing a VAWG ‘marker’ to its international aid statistics from 2017. DFID has stated that it will respond to this. In addition, the inclusion of a VAWG target in the Global Goals offers an opportunity for DFID to draw from indicators currently under development at the global level for its own frameworks. These will include indicators to measure intimate partner violence, sexual violence, CEFM and FGM/C.23

DFID is innovating but lacks a clear approach to scaling up successes

Innovation is a key element in portfolio development. DFID’s programming includes a good range of innovation. Many of these initiatives aim to capture learning, but they are not for the most part embedded in structured processes for assessing whether they are suitable for piloting and then scaling up.

The central ‘WhatWorks’ programme includes a component that provides grants to national organisations and international NGOs for innovative pilot projects. These projects are engaging with new stakeholder groups to promote social norm change, such as religious leaders in Yemen and the Democratic Republic of Congo and peer educators in garment factories in Bangladesh. There are projects exploring the underlying causes of VAWG within relationships, the challenges facing migrant women in Nepal and programmes challenging men’s attitudes towards women in the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Africa. There is also a multi- media project aimed at changing social norms on VAWG across the Occupied Palestinian Territories. While it is too early to look for results, the projects include baseline studies and a mixture of quantitative and qualitative research methods, so as to maximise learning. The goal is to contribute to global knowledge; there is no specific plan for taking successful initiatives to scale.

There is also innovation within DFID’s country-based, VAWG-focused programmes. In Kenya, for example, DFID is using football as a tool to challenge harmful social norms, drawing on the brand strength of the English Premier League. The programme reaches 600 young people each week with a combination of football training, education and mentoring. There is a strong focus on monitoring and evaluation to learn lessons and it is intended that these should feed into other programmes working with sports coaching to address VAWG. The use of branding is potentially a powerful way of engaging men and boys, as well as working with women and girls. However the efficacy and risks of such partnerships have not yet been fully considered.

There is scope for greater engagement to address VAWG that is taking place in private sector contexts. From our desk reviews we saw little evidence that DFID programmes were tackling VAWG in the workplace. DFID’s ‘How To’ note on addressing VAWG in the context of economic empowerment programmes notes that: ‘Women and girls experience violence in the home, in the workplace, in market places and on the way to work. This not only prevents women from earning an income but also restricts business productivity and profitability and therefore impacts on economic growth.’ 24 25

Partnerships with the private sector, NGOs and philanthropic foundations with marketing skills also have potential for addressing Brand and marketing techniques developed in a commercial context can be drawn on as a source of innovation and learning. Through the ‘Girl Effect’, DFID is working with the Nike Foundation26 to build a strong brand identity that can drive social change for adolescent girls. Girl Effect has developed brands in Nigeria, Ethiopia and Rwanda which are being used to encourage girls to make use of services and to challenge the acceptability of violence. The approach is innovative but its impact is yet to be clearly demonstrated. Engaging with the private sector and using marketing techniques to support social norm change are identified as a learning frontier in the final section of the report.

It is notable that the major initiative for piloting new approaches to VAWG has come within a centrally-funded DFID There are limits on DFID’s ability to manage small and innovative programming at country level. Piloting, with its associated monitoring and assessment requirements, is a time-consuming activity, for which DFID staff constraints and pressure for larger programmes leave limited space. One striking exception was the ‘Safetipin’ initiative in India. Its launch was supported through the initiative of DFID advisers (see Box 10).

Safetipin is an innovative phone app developed in Delhi that enables women in urban areas to report on the safety of their surroundings. By combining volunteer reports with those generated by Safetipin staff, the app is able to build up a picture of the overall safety of a range of locations around the city. Safety apps have been subject to the criticisms that some women have no choice but to enter unsafe areas and that the apps put the onus on women to ensure their own security. However, Safetipin has also encouraged urban authorities to invest in improving infrastructure such as street lighting in dangerous locations. Safetipin’s development depended on the willingness of DFID staff to devote time to an innovative pilot. In September 2015, Safetipin announced an alliance with the company Uber to take the app to 50 cities, including in Africa, South America and Asia.

While there are examples of innovative programming across the portfolio, they rarely include explicit plans for how successful innovations will be taken to scale. This is understandable at the current stage in the life of the portfolio, when the priority is to generate new knowledge. However, DFID’s current VAWG-focused programmes are too small to generate transformational change, with numbers of beneficiaries typically in the tens of thousands. At a certain point, the focus will need to turn to delivery at scale so that VAWG can be addressed for a significant proportion of the populations in countries and regions where DFID is working.

The quality of VAWG interventions is lower when integrated into sectoral programmes

One important means for achieving impact at a larger scale is to integrate successful VAWG interventions into wider sectoral programmes, whether government or donor In Bihar, India, we saw a good example of how DFID was able to integrate VAWG interventions into a government-led health programme, which were then moved rapidly to scale (see Box 11). DFID’s internal VAWG guidance and research already points to a range of opportunities for doing this across various major sectors of development work (summarised in Box 12).

The Sector Wide Approach to Strengthening Health (SWASTH) programme is a partnership between DFID and the Indian state of Bihar. DFID is contributing £145 million to a much larger government initiative on rural health, nutrition, water and sanitation. The programme offers a strong example of how collaboration with government can provide a means for the sustainable scaling up of VAWG interventions.

One component of the programme is ‘Gram Varta’ (Hindi for ‘village talks’), an innovative, community-based initiative that works with nearly 80,000 self-help groups and covers about 10% of the population of Bihar. The objective of the programme is to develop a cadre of staff trained to respond to women in distress, including through a helpline and short-stay refuges. These services are intended to give the survivors access to a range of medical, legal and counselling services while protecting privacy and confidentiality.

The programme offers a number of examples of how successful pilots can be taken to scale by leveraging national resources.

• A Gender Equity Model in schools was first piloted in 40 schools in four districts, and is now being extended to 100 schools in 10 districts, addressing 40,000 children.

• Twenty-three special facilities for women were established in police stations. In March 2015, the Chief Minister of Bihar announced that this would be extended to 112 police stations, making use of central government funding.

• Village dialogue work has been scaled up and is now reaching over a million women.

DFID has a range of VAWG-component programmes in operation, but we found the quality of their VAWG interventions to be lower than in VAWG-focused programmes. They are weaker in their contextual analysis and their use of evidence about what works. Over 30% of our sample of VAWG-component programmes have theories of change that do not incorporate VAWG, almost 40% of these programmes lack adequate indicators to support the monitoring and evaluation of VAWG and 50% showed weaknesses in VAWG contextual analysis. This is in contrast to VAWG-focused programmes, where 100% of our sample demonstrated theories of change consistent with the corporate model and adequate indicators and contextual analysis.

This comparison is important, pointing to a dilemma ahead for DFID. While VAWG-focused programmes will remain important for learning and piloting, incorporating VAWG interventions into sector programmes offers a more promising route to delivery at scale. It is therefore likely that DFID’s future VAWG programming will not, in the main, be managed by VAWG specialists. DFID will need to ensure that VAWG expertise is made available during programme design. It must also make sure that the level of understanding of VAWG issues is raised across the department to maintain the quality of interventions. It is important that learning from VAWG-focused programmes and wider research is applied in VAWG-component programmes.

Security and justice

• Legal reform including recognition of marital rape as a crime.

• Improving women’s access to justice and specialist support services.

• Improving formal and informal security and justice systems’ treatment of women and girls.

• Enforcement of child marriage laws.

Health and family planning

• Screening of pregnant women for VAWG.

• Improved medical responses to VAWG.

• Strengthened referral systems between health facilities and support services.

• Ensuring safe access to contraception for women.

Water and sanitation

• Location of water points addressing vulnerability of women to sexual assault.

• Provision of sanitation facilities reducing vulnerability due to open defecation.

Education

• Establishing gender norms in schools

• Teacher training and girls support services.

• Prevention and elimination of VAWG in education system.

Economic empowerment

• Economic empowerment of women and girls to protect against VAWG.

• Building capacity to tackle VAWG within the workplace.

• Enabling environment that does no harm.

DFID is innovating but lacks a clear approach to scaling up successes

FGM/C and, to a lesser extent, CEFM are the most prominent issues where DFID is systematically working at scale internationally and nationally, through a complementary mix of programming, research and advocacy, with identified indicators. These efforts are beginning to yield results. A major part of these initiatives is managed from headquarters and takes the form of contributions to global and regional programmes on FGM/C and CEFM. These are also the issues that DFID chose to promote at the 2014 Girl Summit, which raised awareness and attracted commitments for action. The choice of issues is strategic. While other types of VAWG are more widespread, FGM/C and CEFM lend themselves to focused international campaigns aimed at their eradication – another possible pathway to impact at scale. DFID’s centrally-funded FGM/C programme aims for a reduction of cutting by 30% in 10 countries over 5 years, with the vision to see an end to the practice within a generation. Within our desk review sample, a further six programmes also focused on FGM/C.

DFID’s £35 million five year programme, Towards ending FGM/C in Africa and Beyond is the largest single donor investment ever targeted specifically at FGM/C. The largest FGM programme component, receiving £20 million, is the United Nations Joint Programme on FGM/C. The programme combines advocacy for changes to national laws and policies with mobilising communities to abandon the practice. It aims at a 40% reduction in incidence for girls aged 14 and under in at least 5 countries by 2017. It has reported a range of early results,27 including new policies or legislation in 12 countries and new protocols for treating FGM/C survivors at 5,500 health centres. In addition, 12,700 communities and 20,000 religious and traditional leaders have made public declarations of abandonment (these results pre-date DFID’s funding). While this is a culturally sensitive issue, DFID believes that there is growing African leadership and momentum for change to which it can contribute.

FGM/C is a social practice that is deeply rooted in cultural norms. Despite promising approaches, there is still little solid evidence about how to change these norms (see for example, the Sudan Free of FGC Programme in Box 13). We also noted another instance, in Somalia, where a DFID programme had begun to scale up without a strong evidence base. While it is justified to experiment in this area, given the severity of the issue, the programming will need to be amended in the light of evidence as it emerges. While there is some evidence of success in West Africa, for example,28 there is a lack of evidence showing whether community declarations on the abandonment of FGM/C actually lead to real and sustainable behavioural change in a diverse range of locations. Studies to date mainly focus on changes in attitudes (eg mothers’ intentions regarding their own daughters), rather than actual prevalence.29 DFID funded research on FGM/C through the NGO Population Council is designed to address these gaps with research in up to nine countries to develop cost-effective approaches to eliminating FGM/C at community level.

The Sudan Free of Female Genital Cutting (FGC) Programme is using two social norms change approaches, named in Arabic, ‘Saleema’ (meaning intact, whole or complete) and ‘Almawadah wa Alrahma’ (meaning affection and mercy). These approaches reframe the discussion of female genital cutting in positive and non- threatening terms, while maintaining a clear position that it is not acceptable. Face-to-face communication and social marketing through mass media is complemented by community-level discussions facilitated by local partners. However, we found that the programme, which had been run by its implementing partners since 2013, did not have a robust approach to monitoring and evaluation and was scaled up with limited evidence of its effectiveness. DFID is now working to collect this evidence.

Scale up is the key value for money challenge

The potential economic and social returns to reducing VAWG are significant. There are no readily available techniques however, for calculating the value for money of individual approaches or comparing between alternatives. In 2014, the WhatWorks programme produced a short summary paper on the issue,30 drawn from a research paper which was subsequently published as a longer report in September 2015.31 The papers concluded that, while a number of VAWG interventions had been found to be effective, “little is known about their costs, value for money and how to take them to scale.” At that stage, only eight studies had examined value for money for VAWG programmes in low and middle income countries, and their approaches had been inconsistent. Wide variations in the unit costs of certain interventions, such as post-rape care and gender training, suggested that the design of the interventions was too different for cost comparison to be meaningful. As a result, we cannot reach any clear conclusions at this point as to the value for money of the portfolio.

DFID has begun to focus on value for money in its guidance and programme design, including through the development of standard value for money measures. The cost-benefit analysis undertaken for the Finote Hiwot programme in Ethiopia32 (see Box 14) demonstrates good value for money for this programme, but also illustrates some of the limitations of a conventional approach to value for money in the VAWG context. In particular, it underscores the importance of the scale and replicability of interventions to the value for money equation.

The Finote Hiwot or End Child Marriage Programme in Ethiopia is a five year, £10 million VAWG-focused programme (2011 to 2016) that aims to keep girls in school and reduce child marriage. One of its interventions gives women economic incentives in the form of business loans to keep their daughters in school. The programme is widely praised as innovative and effective. It demonstrates positive value for money with a discounted benefit-to-cost ratio of 2.6, according to a 2015 independent evaluation. A total of 783 girls’ and 259 boys’ child marriages were stopped in 2014/15 in the Amhara region.

Finote Hiwot also exemplifies many of the weaknesses of VAWG-focused programmes. The beneficiary target was scaled down from an initial 200,000, which was unrealistic, to 37,500. While DFID has taken measures to reduce the costs, some of the activities, particularly the financial incentives, are too expensive to be affordable by the Government of Ethiopia, despite the benefits. This is a barrier to any significant expansion of the programme in its current form.

Across the portfolio as a whole, the key value for money challenge, in our assessment, is developing credible approaches to scaling Innovative, small-scale programming is only good value if it generates significant learning that can be applied elsewhere, or if the experience is picked up and replicated. In Bihar, India, we saw a good example of how DFID was able to integrate VAWG interventions into a government-led health programme (see Box 11). If successful VAWG interventions can be introduced into other sectoral programmes, whether or not DFID-financed, they have the potential to generate a much higher return on the investment.

Working with others to achieve transformative impact

The scale of the VAWG problem is too great for DFID or any other agency to address on its own. DFID’s partnerships with and influencing of others are therefore central to any strategy for scaling up. In this section, we examine DFID’s efforts to change international norms and to encourage other governments, multilaterals and civil society organisations to act on VAWG

Our review question was about DFID’s effectiveness in influencing others at the international and UK levels. Our ability to make this assessment was constrained by the confidentiality of some of the international processes and the fact that DFD itself does not systematically monitor its influencing activities in detail. Nonetheless, we were able to reach a number of conclusions about DFID’s contribution, alongside other actors. These were based on comparisons between DFID’s objectives and achievements, and through interviews with 15 multilateral and bilateral partners.

DFID has helped promote VAWG in the international development agenda

DFID has made a concerted effort to raise the VAWG agenda in international processes and events. It has helped to increase further the profile of VAWG at the United Nations, including supporting the General Assembly resolution on CEFM in December 2014. It has also been active in the Human Rights Council and the Commission on the Status of Women. While women’s rights organisations, academics and other donor countries have worked on these agendas for longer, civil society and government interviewees welcomed DFID’s entry into the field. As one of the world’s largest bilateral donors, DFID helps to set priorities within the global system. It has used this influence to promote the cause of VAWG, as evidenced by our interviews and published speeches and interventions by UK ministers.

DFID campaigned to secure the inclusion of gender and VAWG into the Global Goals, with a range of activities to co-ordinate and influence partners. Its objective was achieved in the form of a stand-alone gender goal (‘achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’) and an associated VAWG target (‘the elimination of all forms of violence against women and girls in the public and private spheres’). DFID was only one voice among many that were pursuing this goal. However, from the involvement of the Prime Minister in co-chairing the High Level Panel through to the negotiation of the final declaration, the stakeholders we spoke to, from seven governments and six multilateral organisations, were in agreement that the UK had made a positive contribution, particularly in mobilising political leadership.

The Global Goals come with an overarching commitment to ‘leave no one behind’. Given the barrier that VAWG creates to achieving other development goals and the tendency for survivors to be marginalised, this commitment should help to give the VAWG agenda greater priority. It also calls for a focus on ‘intersectionality’ – that is the experience of women affected by multiple discriminations, including those living with disabilities, those from lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender communities and minority ethnic and religious communities. Our interviews with other government departments indicated that the global nature of the Goals, including those focused on VAWG, means that they are given a much higher profile across government than the Millennium Development Goals, which applied only to developing countries.

The Girl Summit helped raise the profile of CEFM and FGM/C

In 2014, the UK organised the Girl Summit, co-hosted with Unicef, which focused on ending FGM/C and CEFM. This high-profile event was attended by the Prime Minister, other UK ministers and a wide range of senior figures from partner countries, as well as broad representation from civil society. The event was notable for giving a strong profile to the voices of adolescent girls and was accompanied by an effective social media campaign. With DFID expenditure of £123,000, supplemented by contributions from the Home Office and the private sector, it proved to be a very cost-effective means of adding momentum to global campaigns on these issues.

Over 490 signatories were secured for the Girl Summit Charter on Ending FGM/C and CEFM, including those from key countries such as Brazil, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen. The Summit has been followed by national Girl Summits in Uganda, Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Nepal, and an African Union regional event in Zambia. Eighteen Governments in Africa, the Middle East and South Asia where FGM and child marriage are prevalent have made commitments to end the practices; 16 on eliminating child marriage, 12 on ending FGM and 10 on ending both practices33. These events suggest that the issues are gaining greater profile in developing countries. Following the London Summit, the governments of Bangladesh and Ethiopia made specific commitments to ending child marriage. The responsible Ethiopian minister commented to us that the London Girl Summit ‘crystallised the Government of Ethiopia’s support for ending child marriage.’

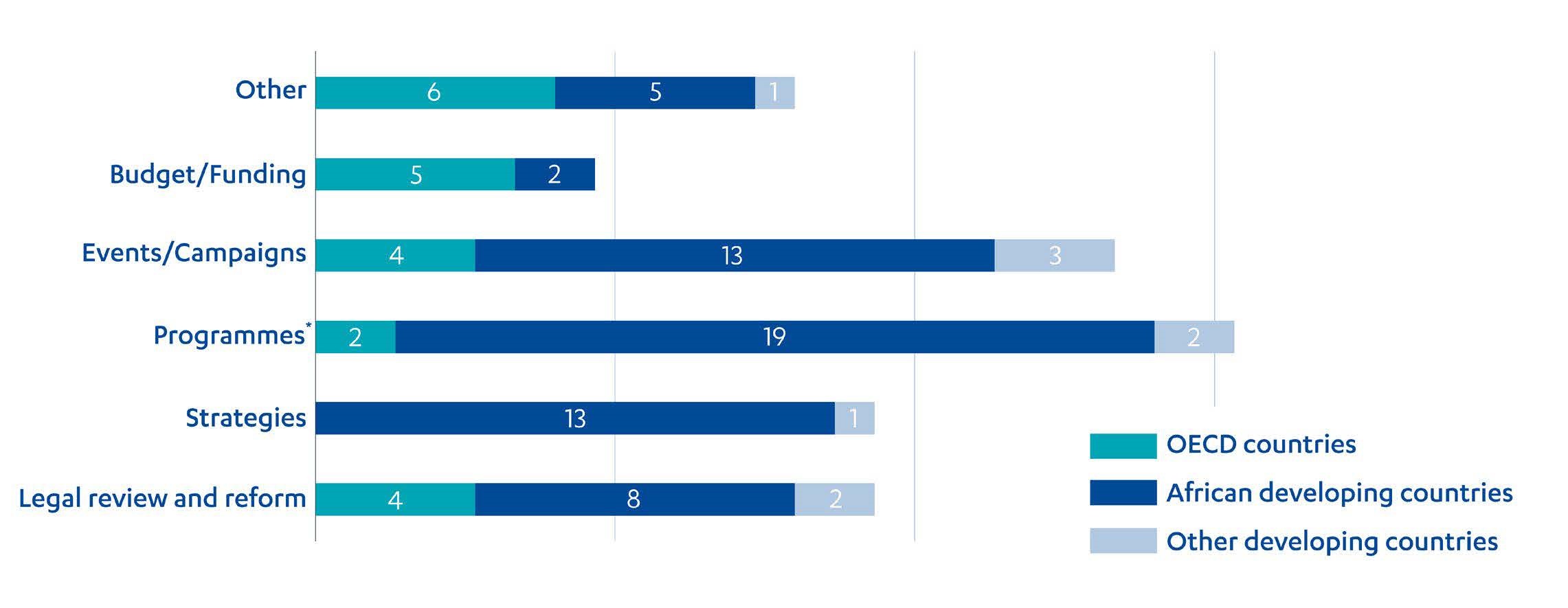

At the Summit, participants were invited to make specific commitments to follow-up actions. While there were commitments from 27 national governments, most of these were modest in ambition (see Figure 4). Since then, progress on the more challenging actions, such as increasing budgets and reforming laws, has been slow. However, as of December 2015, the Girl Summit pledge website34 had recorded over 12,500 pledges and 130,000 messages. Most interviewees agreed the value of the initiative lay in raising the profile of the issues, rather than garnering specific actions.

Figure 4: The composition of Girl Summit Pledges by 27 national governments

DFID could do more to encourage multilateral partners to engage on VAWG

DFID has worked closely with a range of multilaterals, including the World Bank and the European Union, on the wider issue of gender equality. DFID contributed to the strengthening of the World Bank’s gender strategy and the European Union’s Gender Action Plan. It does not however, have specific VAWG objectives for its multilateral influencing. There is a strong argument for leading with VAWG within gender, particularly in politically challenging contexts. Addressing the underlying drivers of VAWG, such as abuse of power and gender inequality, can be a good entry point for addressing gender justice.

Among the multilateral development banks, the World Bank has pushed ahead with research and policy work on VAWG, with DFID support, and is at a stage where it could mainstream VAWG through its sectoral programmes. Other development banks lag further behind. Mainstreaming of VAWG in sectoral programmes funded by multilateral organisations should be a significant element of DFID’s future plans for overall scale up of the global VAWG response.