Achieving value for money through procurement Part 2: DFID’s approach to value for money through tendering and contract management

Score summary

An appropriate overall approach to procurement with good performance in most areas of tendering, but significant weaknesses in contract management.

DFID has made a concerted effort over the past decade to strengthen its procurement, with faster progress since 2015. New initiatives to address previous key areas of weakness include commercial delivery plans, sourcing strategies, codes of conduct, new contractual terms and conditions, and cost guidance. The 2017 Supplier Review has increased the focus on supplier transparency and accountability, giving DFID more visibility over costs and profits – although we are not convinced that new rules on recovering excess profits are the right solution. Lack of adequate consultation with suppliers during the Supplier Review increased the risks of unintended consequences, which need to be carefully monitored. Overall, DFID’s reformed procurement approach meets UK government guidance and should help to drive up value for money.

We reviewed contracts over a five-year period, finding significant improvement in DFID’s practices since recent reforms and capacity-building initiatives. The new sourcing process means that DFID now approaches procurement for major projects in a more strategic way. More early market engagement has helped to increase competition. However, DFID is over-reliant on quicker procurement methods, rather than using negotiated processes that would enable it to define its needs more clearly and potentially increase efficiency and effectiveness. The department has hired more procurement professionals and provided commercial training across the department. However, an antiquated management information system remains a significant limitation.

Contract management emerges as the major weakness in DFID’s commercial practice. The function is not well defined or adequately resourced, which limits DFID’s ability to manage supplier performance. Overly rigid contract terms and inception periods that are too short mean that contracts need frequent amendment. There are rigidities in DFID’s contracting process that work against its goal of more flexible and adaptive programming. DFID takes an appropriately cautious approach to payment-by-results contracting, but needs to be careful not to suppress innovation.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Relevance – To what extent is DFID’s strategy and approach to procurement appropriate to its objectives and priorities? |  |

| Question 2 Effectiveness – How well does DFID secure value for money through its tendering practices? |  |

| Question 3 Effectiveness – How well does DFID secure value for money through its contracting and choice of payment mechanisms? |  |

Executive summary

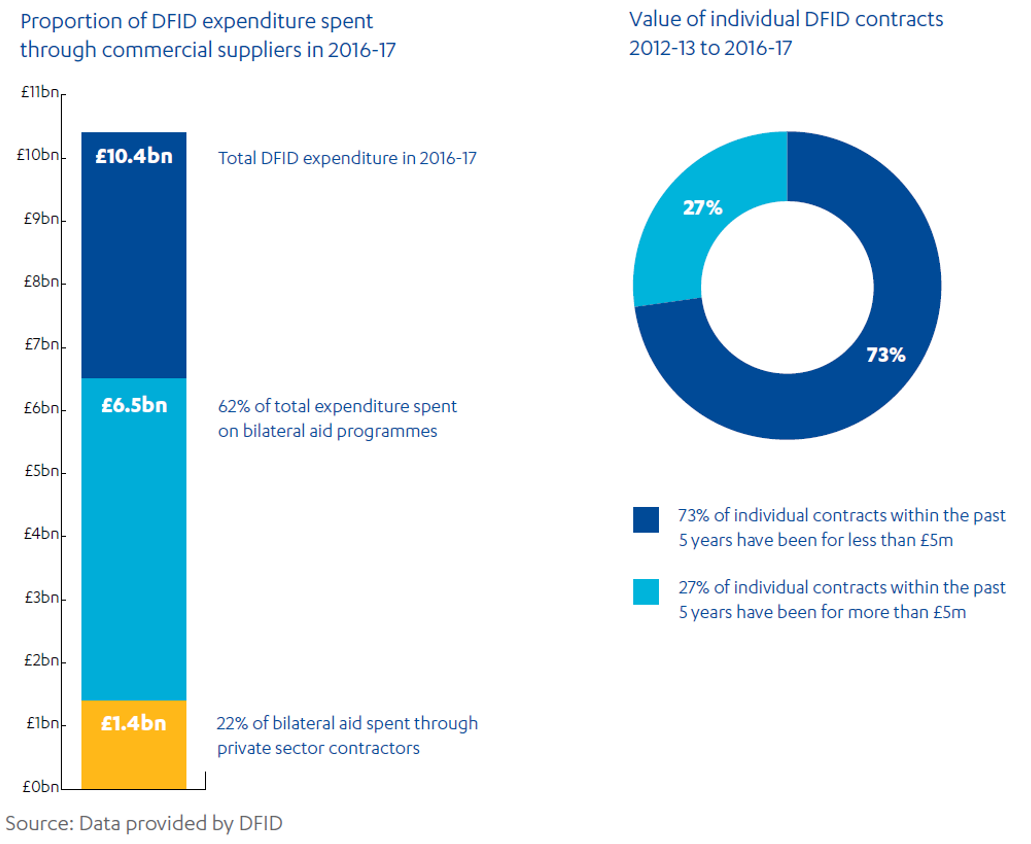

The Department for International Development (DFID) spent around £1.4 billion, or 14% of its 2016-17 budget, through commercial suppliers. The quality of its procurement and contract management – how it engages and manages commercial firms to support the delivery of aid programmes on time, to budget and at the appropriate quality – is a key driver of value for money for UK aid. It is also a subject of considerable Parliamentary and public interest. In recent years, DFID has implemented a range of initiatives to strengthen its procurement practice and embed commercial capability across the department – including its 2017 Supplier Review, undertaken to address concerns about excessive profit-making by DFID suppliers.

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) has conducted two reviews of how well DFID achieves value for money through procurement. The first, published in November 2017, explored DFID’s efforts to shape its supplier market. This second review examines whether DFID maximises value for money from suppliers through its tendering and contract management practices. We assess DFID’s procurement approach against UK government rules and guidance, and the commercial objectives that DFID has set for itself. We also reviewed a sample of 44 contracts, representing a third of DFID’s expenditure through commercial suppliers over the 2012-17 period. Our methodology included visits to Nigeria and Tanzania to explore some of these contracts in more detail.

Does DFID’s approach to procurement support its objectives and priorities?

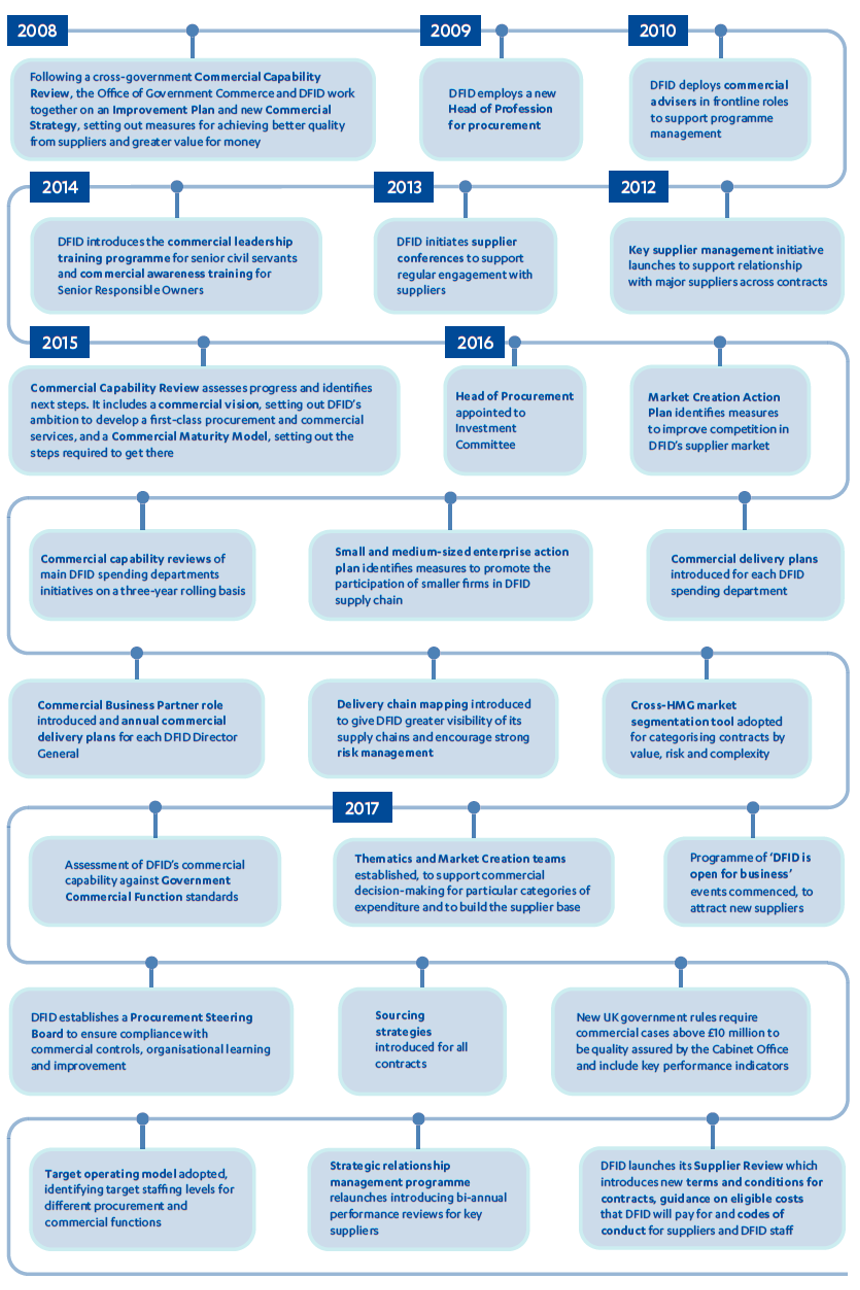

DFID’s procurement approach has developed progressively over the past decade. A cross-government review of commercial capability in 2008 placed DFID tenth of 16 government departments, noting that it treated procurement as an administrative cost rather than a management tool for enhancing value for money. From 2008 to 2015, DFID worked to establish a governance structure and operating model for procurement and to build up capacity in its central Procurement and Commercial Department and across its spending units. We found the pace of change over this period to be relatively slow, possibly indicating the lack of a strong champion for procurement at board level.

From 2015 the pace of change accelerated. DFID introduced a range of new initiatives. It adopted the objective of becoming “a world-class commercial organisation”, supported by a strategy and delivery plan setting out the steps required. Reforms since then have included:

- Commercial delivery plans for spending departments.

- A new sourcing approach, which involves analysing the capacity of the market to deliver the services required and making more strategic decisions about how to approach procurement.

- Increased early market engagement with suppliers, to gauge the level of competition and how to maximise it.

- Codes of conduct for suppliers and for DFID staff when dealing with suppliers, to protect against collusion and conflicts of interest.

- New standard terms and conditions for supplier contracts, including a requirement for open-book accounting, giving DFID greater potential to scrutinise costs and profits and benchmark fee levels across suppliers.

- New guidance on the costs that suppliers can charge DFID.

- Measures to increase transparency and accountability of subcontractors in DFID’s supply chains.

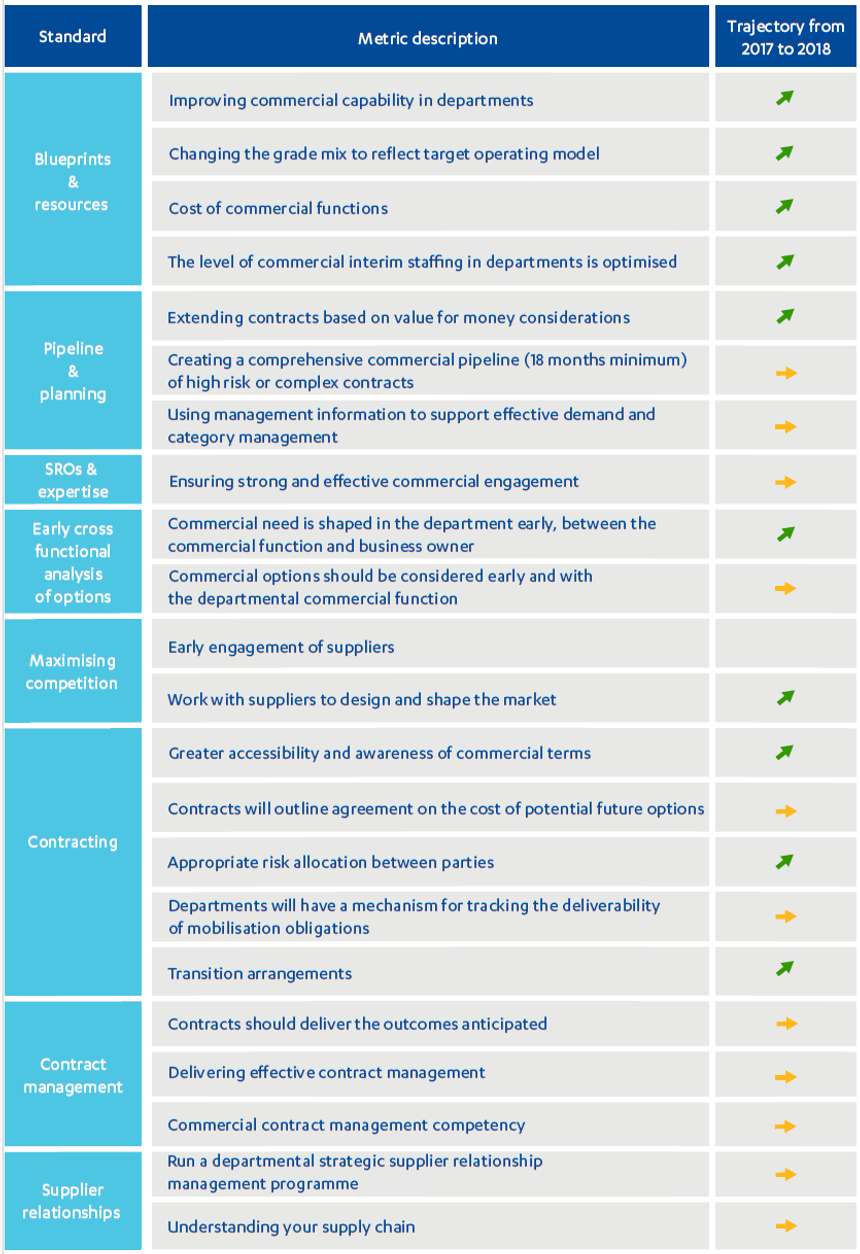

Some of these initiatives are now well established, while others are still being tested and refined. Overall, we find the approach to be consistent with UK government guidance and applicable legislation, with the potential to deliver significant improvements in value for money. In a recent assessment and peer review against the Government Commercial Operating Standards, DFID was found to have improved on 11 out of 22 measures, with only two areas rated as underperforming, compared to 12 months ago.

The Supplier Review was a nine-month, ‘root and branch’ reassessment of supplier practices, which concluded in October 2017. It drew together various ongoing initiatives, while announcing new measures to promote supplier accountability and transparency. It provides DFID with some useful new tools to monitor suppliers. It also introduces new contractual provisions entitling DFID to recover supplier profits if they exceed the level agreed for that contract. We are not persuaded that this is the right approach for ensuring fair profits. As we concluded in our 2017 procurement review, there is no hard evidence of excessive profit in DFID’s supplier market. Ongoing efforts to boost competition are a more appropriate strategy for keeping costs and profits in check. The new contractual rules may create incentives for suppliers to conceal their profits, which works against the objective of transparency. We also find that lack of consultation with suppliers during the Supplier Review – a result of the intense political pressure surrounding the process – has increased the risk of the reforms resulting in unintended consequences. This communication gap now needs to be overcome.

In early 2018, a scandal around the sexual exploitation of aid recipients in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake highlighted an urgent need to ensure that safeguards were in place in DFID’s supply chain. Since then, DFID initiated a review of its programme management processes and its contractual terms for grantees and suppliers, which needed to be adjusted to address this risk more explicitly.

DFID’s procurement approach is set out in its Smart Rules and associated guides and information notes. While these are comprehensive and well written, we identified various issues with internal consistency and version control.

Overall, we find that DFID’s procurement approach is appropriate to the department’s objectives and developing in the right direction to deliver value for money, meriting a green-amber score.

How well does DFID secure value for money through its tendering practices?

Our in-depth review of 44 contracts covers DFID’s procurement practice over a five-year period. We found considerable improvement over that time, as DFID has boosted its commercial capacity and introduced new tools and processes.

In most of the older programmes in our sample, advance planning on how to approach the procurement was inadequate. The commercial aspects of business cases lacked appropriate analysis of the supplier market or structured consideration of procurement options. In 2017, DFID introduced sourcing strategies – identifying options for sourcing goods or services from the market – for all programmes, which are approved by a new Procurement Steering Board. For the six programmes in our sample with such a strategy, we found that procurement decisions were based on a much better understanding of market conditions and supplier capacity, and that DFID had made efforts to structure its requirements to make the most of what the market could offer.

This has been supported by increased early market engagement, where DFID meets with potential suppliers to gauge the level of interest in forthcoming programmes. There has been an increase in the average number of bids per tender, from 2.5 in 2015-16 and 2.9 in 2016-17 to 3.3 in 2017-18, against a target of four by April 2019. However, more still needs to be done to improve the visibility of opportunities and make it easier for potential bidders to identify and prepare for opportunities. At the time of conducting our review, for example, no accurate pipeline could be provided.

We find that DFID has not always chosen the most appropriate procurement process from among the options permitted by the law. It has been overly reliant on open or restricted procedures and made too little use of negotiated options. The latter are often better suited to complex aid programmes where the package of services required cannot be specified in advance. The introduction of the sourcing strategy process is, in principle, an appropriate way of addressing this.

DFID has made a concerted effort to build its commercial capability. Its procurement department has expanded from 41 staff in 2010-11 to 121 in 2018. It has made efforts to recruit and retain more senior procurement experts, despite struggling to offer competitive salaries due to restricted pay levels set by central government. DFID is also rolling out training programmes to increase commercial knowledge across the department, and has introduced commercial delivery managers to support country offices and spending departments. The increase in capacity has allowed DFID to be more ambitious in its procurement and commercial work, but continued effort will be needed to embed commercial skills and awareness across the department.

One significant gap in DFID’s capacity is the lack of an integrated management information system to record all aspects of the procurement process. DFID’s procurement is currently supported by multiple, ageing IT systems that do not interact. As a result, there is no single audit trail for procurements, and DFID has difficulty generating the data required to make informed decisions. While this problem has been apparent for some time – and was raised in our 2017 procurement review – progress on addressing it has been slow.

Our analysis suggests significant improvement over the review period, with stronger performance on procurement in the most recent contracts. While DFID still has a way to go in building the capacities and systems required to achieve its ambitions, it merits a green-amber score for its recent performance.

How well does DFID secure value for money through its contracting?

While DFID has a well-established programme management process to guide aid delivery through third parties, the commercial and contractual aspects of its management of suppliers are not well articulated. To effectively manage a contract requires monitoring of whether suppliers comply with budgets, timetables and other contract terms, and maintaining a productive relationship between suppliers and DFID. Without active contract management, there is a risk that programmes may achieve poor commercial outcomes even if they successfully reach their targets.

Within DFID, no senior official or department had overall responsibility for the contract management function at the time of our review. The role was split among various personnel, without clear assignment of functions and responsibilities. While there is some reference to contract management in DFID’s Smart Rules and Guides, the processes are not clearly defined or supported by adequate training. Across our sample of contracts, we found that core management processes such as annual reviews make little reference to contractual or commercial matters. The lack of a formal contract management regime means that DFID often reacts to performance issues only after a poor annual review score, rather than using performance incentives and other tools proactively to prevent problems from occurring. DFID has acknowledged the weakness in its internal assessments of contracts, and it was also highlighted in the 2018 cross-government peer review of commercial capability.

Across our sample, we found that 34 out of 44 contracts had been subject to formal amendment, on average three times each. Over the past five years, the value of DFID’s 711 contracts has been extended by a total of £2 billion. As well as being costly and time consuming, this suggests that the programmes may have been procured based on incorrect assumptions, which distorts the tender process. We also found that the inception phases on DFID contracts are often too short for the preparatory processes (such as background research and consultation – the requirement will vary for each contract) needed to define targets and milestones accurately. For example, in one programme to tackle stunting in Tanzania, a performance-based contract tied payments to progress in changing community behaviours around nutrition, but the inception period allowed too little time to establish an accurate baseline against which to measure change.

DFID has set itself the goal of moving towards more flexible and adaptive programme management, to allow for learning through the implementation process. We heard concern from stakeholders both within and outside the department that DFID’s contracting practices do not support this level of flexibility, because activities and outputs are often written into contracts and can only be changed through formal contract amendment.

Payment-by-results (that is, where part of the payment is conditional on achieving agreed results) is now common in DFID contracts. In the right conditions, it can incentivise better supplier performance, but it is a complex tool to use with a risk of unintended consequences. We find that DFID has generally been cautious in its use. In most instances, only a portion of the fees is performance-based and generally linked to activities or outputs that are within suppliers’ control. While there is a risk that payment-by-results may discourage smaller firms and non-governmental organisations from participating, we saw examples of DFID managing this risk by adjusting the level of payment-by-results. It is difficult to assess at this point whether payment-by-results is in fact improving supplier performance. DFID is beginning to develop a better understanding of supplier incentives, but this is still a new field where further learning is required.

Overall, we find that contract management is a significant area of weakness for DFID that is not being adequately addressed by ongoing reforms, meriting an amber-red score.

Recommendations

DFID has now put in place most of the building blocks for a robust procurement system able to drive up value for money in aid programmes. However, there are some important gaps still to be addressed. We offer the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1:

Before the next major revision of its supplier code and contracting terms, or future changes that may materially affect suppliers, DFID should conduct an effective consultation process with its supplier market, to ensure informed decisions and minimise the risks of unintended consequences.

Recommendation 2:

DFID should accelerate its timetable for acquiring a suitable management information system for procurement, to ensure that its commercial decisions are informed by data.

Recommendation 3:

DFID should instigate a formal contract management regime, underpinned by appropriate training and guidance and supported by a senior official responsible for contract management across the department. The new regime should include appropriate adaptive contract management techniques, to ensure that supplier accountability is balanced with the need for innovation and adaptive management in pursuit of development results.

Introduction

DFID is committed to ensuring value for money across its portfolio. The UK aid strategy states: “We will ensure that every penny of money delivers value for taxpayers.” In 2016-17, the department spent £1.4 billion, or 14% of its budget, through commercial suppliers on contracts ranging from school construction to family planning services and the delivery of humanitarian aid. Poor procurement and contract management practice can result in DFID overpaying for services or obtaining poor quality from suppliers, at the expense of the beneficiaries of UK aid. The quality of its procurement and supplier management is therefore an important driver of value for money. In recent years, procurement has emerged as a subject of particular concern to both Parliament and the public.

This is the second of two reviews undertaken by ICAI of DFID’s approach to procurement. The first review assessed whether DFID influenced and shaped its supplier market in order to improve value for money. This second review assesses whether DFID has maximised value for money from suppliers through its tendering and contract management practices. These reviews complement a further ICAI review published in February 2018 on DFID’s approach to value for money in programme and portfolio management. Together, these three reviews cover the key processes by which DFID ensures value for money for the UK taxpayer and the beneficiaries of UK aid.

This is a performance review (see Box 1), providing Parliament and the public with an assessment of whether DFID makes appropriate use of competitive procurement, and whether its tendering and contract management practices secure quality programme delivery at competitive prices. It also assesses whether DFID has adequate controls in place against uncompetitive practices and unethical behaviour. Our review questions are set out in Table 1.

“At the procurement/mobilisation stage, achieving VfM [value for money] means minimising costs, given the quality and quantity of outputs required through robust and commercially savvy procurement; ensuring an appropriate balance of risk between DFID and our suppliers or delivery partners; ensuring that suppliers or delivery partners’ incentives are aligned with maximising development impact during programme delivery; and ensuring that the contract or agreement allows effective and suitably adaptive programme and contract management during delivery and at closure.”

DFID’s approach to value for money, DFID Smart Guide, March 2017

Box 1: What is an ICAI performance review?

ICAI performance reviews examine how efficiently and effectively UK aid is being spent on a particular area, and whether it is likely to make a difference to its intended beneficiaries. They also cover the business processes through which aid is managed, in order to identify opportunities to increase effectiveness and value for money.

Other types of ICAI reviews include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries; learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming; and rapid reviews, which are short, real-time reviews examining an emerging issue or area of UK aid spending.

This review covers DFID’s procurement of goods, works and services in relation to aid programmes over the period 2012-13 to 2016-17, including ongoing contracts initiated during that period. It assesses the full range of procurement and contract management practices, from defining supply need and identifying delivery options through contract award to oversight and monitoring of suppliers and contract compliance (a glossary of procurement terms is included in Annex A). It explores how well DFID captures and applies lessons on procurement. The review does not cover agreements with multilateral organisations, grant making to non-governmental organisations (NGOs), financial aid to partner governments, the procurement of goods and services for DFID’s own administrative use or procurement by other aid-spending departments.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review question | Review criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: To what extent are DFID’s strategy and approach to procurement appropriate to its objectives and priorities? | • Does DFID have a clear and appropriate approach to ensuring value for money through supplier procurement? • How well does the tender process reflect applicable legislation, regulations and guidance, DFID’s cross-cutting objectives and the objectives of individual aid programmes? |

| 2. Effectiveness: How well does DFID secure value for money through its tendering practices? | • Are DFID’s procurement decisions informed by commercial and technical expertise and knowledge of market conditions? • How well does DFID manage competitive tenders and contract negotiation? • How effective are DFID’s controls against anti-competitive practices? |

| 3. Effectiveness: How well does DFID secure value for money through its contracting and choice of payment mechanisms? | • How well does DFID’s supervision of its suppliers ensure that quality delivery and competitive prices are maintained through the programme cycle, including post-award modifications to contracts? • Does DFID make appropriate choices as to payment mechanisms? |

Methodology

Building on the data collected during our 2017 procurement review, our methodology consisted of four mutually reinforcing components designed to generate a holistic picture of DFID’s procurement practice:

- Literature review: an analysis of UK government rules and other commonly used guidance and best practices from across government and the international development sphere.

- Strategic review: an assessment of DFID’s procurement policies, strategies, systems and processes across the whole procurement cycle, benchmarking these against the requirements and best practices identified in the literature review. The assessment included analysis of data from DFID’s management information systems to identify patterns and trends in procurement.

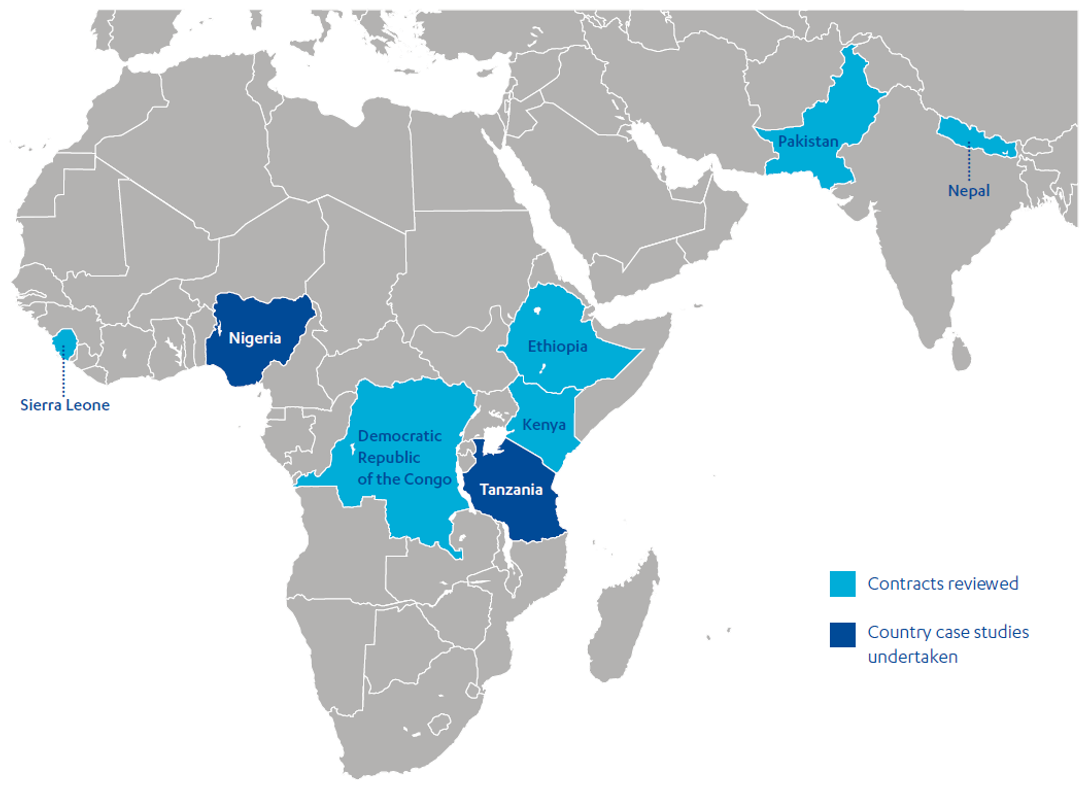

- Desk reviews of contracts: reviews of a sample of 44 DFID contracts, including programmes from eight countries plus three centrally managed contracts, featuring different contract types and market conditions, to identify strengths and weaknesses in DFID’s procurement practice (see Box 2 for our sampling approach and Annex 1 for details of our sample). The sample accounts for 33% of DFID’s total planned expenditure through commercial suppliers between 2012-13 and 2016-17.

- Country case studies: visits to two DFID country offices (Nigeria and Tanzania) to review procurement practices at the country level. This included following a subset of our sample contracts from tender through to contract delivery, consultation with programme teams and interviews with delivery partners and other stakeholders to assess how well any performance issues were identified and dealt with.

We used a stratified sampling approach to select contracts for detailed review, choosing contracts from each of seven categories (see Box 2) to provide a representative picture of DFID’s procurement practices. For selecting country case studies, we identified Nigeria and Tanzania as offering the best coverage across these categories. Nigeria had the third largest DFID country programme in 2017-18, at £282 million. It has a large number of contracts across sectors (eg health and infrastructure) and contract types (eg fund managers, logistics, technical assistance and purchase of commodities). Nigeria also presents a challenging operating environment, with implications for procurement practices. Tanzania is a mid-range country for DFID in terms of expenditure, with a high number of contracts of lower average value. We visited Nigeria for two weeks and Tanzania for one.

Box 2: Our sampling approach

Based on DFID’s current contract data, we categorised all open and completed contracts between 2012-13 and 2016-17 according to the following, non-exclusive criteria, in order to ensure that our sample covered the main procurement challenges that DFID faces. Note that these are attributes, rather than types of contract.

- High value: the top 30% of contracts by value.

- Medium value: the middle 40% of contracts by value.

- Kraljic Strategic: procurements with a high risk of dependency on a small number of suppliers.

- Kraljic Bottleneck: where there are a limited number of potential suppliers and risk of exposure to price increases or supply disruption.

- Key suppliers:12 contracts awarded to key suppliers (accounting for approximately 40% of DFID’s contactor spend).

- Mid-tier suppliers: suppliers accounting for the next 30% of DFID’s contractor spend.

- High and medium country spend: countries in the top 30% and middle 40% of expenditure through procurement.

During our country visits, we interviewed a range of key stakeholders, including DFID staff, suppliers and government officials. In the UK, we also held face-to-face interviews with a wide range of internal and external stakeholders, including DFID staff, suppliers, NGOs, representatives of other government departments, and independent procurement experts.

Figure 1: Map of country case study and contract locations

Box 3: Limitations to our methodology

DFID’s procurement practices have evolved continuously over the review period, and changes take time to impact on supplier behaviour and the supplier market. As we have reviewed contracts over a fiveyear period, our findings do not always reflect the latest changes. Where we identify weaknesses in DFID practices, we also assess whether the shortcomings are likely to have been addressed by subsequent reforms.

While our sample of contracts provides coverage of eight countries and accounts for 33% of DFID’s planned expenditure through suppliers from 2012-13 to 2016-17, it is not fully representative and some sectors and contract types may receive greater focus than others.

Background

Procurement and contract management in DFID

DFID does not deliver aid programmes directly, but acts as a commissioning organisation. Its programmes may be procured from a contracted supplier, delivered through a third party such as a multilateral organisation or NGO, or be granted as financial aid to a developing country. Over recent years, the amount of aid spent through suppliers has increased rapidly, from £0.7 billion in 2012-13 to £1.4 billion in 2016-17, rising to 13.6% of DFID’s total expenditure (see Figure 2). In 2016-17, DFID awarded 114 contracts to private sector companies, NGOs and academic institutions.

Figure 2: DFID’s supplier expenditure over the last five years

Responsibility for procurement at DFID is shared between the central Procurement and Commercial Department and the units responsible for managing aid programmes (country offices and central spending departments). For contracts above a certain threshold, a competitive procurement must be conducted (except in limited circumstances where the regulations allow alternative procedures). The Procurement and Commercial Department identifies the most appropriate route to market and manages the process, but the spending department retains responsibility for key elements, including preparing the business case and managing the resulting contract. For contracts below the threshold, procurement is managed solely by the spending department. Each programme has a Senior Responsible Owner, responsible for ensuring appropriate use of public funds, supported by programme managers. The Procurement and Commercial Department is responsible for ensuring that all procurement complies with EU and UK law, meets UK government policy, delivers DFID’s commercial needs and provides value for money.

DFID’s efforts to build commercial capacity

In 2008, the government undertook a procurement capability review of key spending departments. A National Audit Office analysis of the results placed DFID equal tenth out of 16 departments. It reflected that procurement in DFID at that stage was viewed as an administrative cost, rather than a core business process capable of enhancing value for money. It concluded that:

- insufficient value was placed on procurement by the departmental board, highlighted by the standing of the head of procurement three levels below the board in the department hierarchy;

- poor performance was not monitored and shared through the department, allowing suppliers with poor performance records to win contracts;

- there was evidence that the central procurement department was delegating contract management to untrained in-country staff, increasing the risk of poor contract outcomes.

Since then, DFID has made a sustained effort to build up its commercial capacity. The Procurement and Commercial Department has expanded from 41 staff in 2008 to 121 in August 2018, with plans to have 142 staff by the end of 2018-19. DFID has also implemented commercial awareness training for non-specialist staff, including all senior civil servants. The Procurement and Commercial Department has adopted a Procurement and Commercial Vision setting out its ambition to develop a first-class commercial and procurement service (see Box 4).

Box 4: Extract from DFID’s Procurement and Commercial Department ‘Vision’

First class commercial and procurement service within DFID

- Providing expert commercial advice to design and manage development

programmes - Robust assurance and governance: agile and flexible, with appropriate control, risk and contract management

- Service excellence, enabling the business to be ambitious and innovative in

programme delivery - Meeting the Government Commercial Standards as set out by Cabinet Office

Maximising and shaping markets

- Shaping both international and local markets alike

- Collaborates with other donors, multilateral organisations and across UK

government to ensure opportunities are visible to the market, to include both

local and UK SMEs - Developing key markets that grow the supply base, build local sustainable capability and increase choices

- Creating greater assurance on market capability and capacity, increases competition and improved value for money

Our commercial influence and impact on the wider sector

- DFID understands the wider international development system and the

impact of its commercial choices, not just on its own programmes, but on the work of others - Developing ever-stronger links with the private sector and bring about economic growth

- Ensure policy decisions consider commercial effectiveness and drive sustainable commercial reform across the multilateral system

These efforts form part of a wider UK government initiative to drive up commercial standards, under the leadership of a new Chief Commercial Officer. The government has recognised that departments lack the capacity to deliver commercial functions at the standard and scale required. It is therefore going through a process of building the capability of 4,000 civil servants in commercial functions across central government and establishing a new Government Commercial Organisation to provide centralised employment and development opportunities for 400 of the most senior staff in the commercial profession.

“[T]he best outcomes can be achieved when commercial professionals work closely together to understand whether achieving policy goals requires outsourced services, significant new technology or property procurement, or the involvement of external parties in other ways. It also means taking a broad view of commercial needs within departments and across government, and considering whether existing markets can meet our needs. Once we have procured the products or services, we need to continue to get the best from them.”

Government Commercial Excellence

DFID’s procurement became subject to heightened external scrutiny in 2016 as a result of allegations that one of its major suppliers had engaged in unethical practice in order to gain a competitive advantage, leading to an inquiry by the International Development Committee. The allegations exacerbated concerns raised by the Committee about perceived high profits earned by commercial suppliers in the aid sector. As well as an internal investigation into those allegations, the then International Development Secretary commissioned a far-reaching review and reform of DFID’s procurement practices, which became known as the Supplier Review. The Supplier Review drew together and accelerated procurement reforms that had been in train for some time. The results are considered as part of this report.

Findings

This section sets out the findings of our review. We first assess relevance: to what extent are DFID’s strategy and approach to procurement appropriate given its objectives and priorities. We then turn to effectiveness: whether DFID secures value for money through its tendering practices. Finally, we assess how well DFID secures value for money through its contracting and choice of payment mechanisms.

Relevance: To what extent are DFID’s strategy and approach to procurement appropriate to its objectives and priorities?

Since 2015, DFID has progressed towards a more mature procurement approach

The procurement function in DFID has been developing progressively over the past decade (see Figure 3 for a timeline of key changes), driven by increased procurement spend, increasing complexity of DFID’s procurement and high levels of external scrutiny.

In 2008, a cross-government commercial capability review found that DFID lacked a clear and comprehensive procurement strategy, and viewed procurement as an administrative cost rather than a strategic management tool capable of enhancing value for money. It identified that improvement was needed in nine areas, with three of them classed as urgent: leadership, client capability, and information and performance management.

From 2008 to 2015, DFID’s reforms focused on creating an appropriate governance structure and operating model for DFID procurement, strengthening the Procurement and Commercial Department and, in later years, embedding commercial skills across the department. The impact of these measures on DFID’s organisational capacity is considered below under Effectiveness. There were also a number of measures undertaken to improve DFID’s approach to market shaping, including the introduction of frameworks for particular categories of procurement, a supplier management programme and more regular interaction with suppliers. These areas were assessed in our 2017 procurement review.

While it was logical for DFID to build up its commercial capability before introducing more sophisticated approaches to procurement, we find that progress over the 2008 to 2015 period was too slow and cautious, given the shortcomings identified in 2008 and the fact that DFID’s volume of procurement was growing so rapidly. This was indicative of the lack of a strong champion for procurement within DFID’s senior management structure – an issue that had been pointed out in the 2008 commercial capability review.

From 2015, however, the pace of change has picked up. DFID adopted a commercial vision (see Box 4) stating its objective of becoming “a world-class commercial organisation”. The commercial vision is supported by a strategy and a delivery plan which describe a range of ongoing initiatives to strengthen the procurement function. The strategy includes a Commercial Maturity Model, describing the steps required to move from a ‘basic’ approach (procurement as an administrative function, without much focus on wider commercial issues) to a ‘best in class’ approach, with a strategic approach to sourcing and commercial functions integrated into the department’s management processes.

Figure 3: Timeline of DFID procurement reforms

Some of the key reforms introduced since 2015 have included:

- Commercial delivery plans for each spending department, which encourages them to give more strategic consideration to their procurement needs and how to interact with their supplier markets.

- First steps towards the introduction of a ‘Thematics’ process – namely, procurement strategies for particular segments of the market (eg medical supplies or evaluation services).

- Sourcing strategies for all contracts, to encourage forward planning on how to approach the market and how to interact with suppliers.

- A quality assurance process for commercial cases above £5 million, including review by a new Procurement Steering Board (see paragraph 4.13) of senior procurement experts.

- Increased dialogue with suppliers and early market engagement around forthcoming tenders, to collect feedback on how best to approach the tender process.

- Codes of conduct for DFID suppliers and for DFID staff which articulate ethical standards and set clear rules prohibiting collusion and conflicts of interest (see Box 5).

- New standard terms and conditions for supplier contracts. Among other things, these set out the requirements for open-book accounting, whereby suppliers are required to disclose details about their costs and profits. This provides DFID with greater market intelligence, giving it the potential to benchmark across contracts and suppliers.

- Guidance on costs that can be charged to DFID by suppliers, designed to ensure that taxpayer money is only used as intended. It includes items that cannot in any circumstances be charged to DFID (such as the cost of petitioning the UK government for additional funding, or the cost of funds lost to fraud and corruption). It clarifies when and to what extent suppliers can charge for capital costs and management overheads, as well as project delivery costs, and sets out allowable expenses for travel.

- Measures to increase transparency and accountability of subcontractors in DFID’s supply chains.

- A redesigned strategic relationship management programme, including bi-annual cross-contract performance reviews for major suppliers.

These reforms were supported by a programme of training across the department to promote better understanding and implementation.

Some of these reforms are now well established, while others are still at an early stage of implementation and will need to be tested and refined. Overall, we find that the approach is consistent with the Commercial Operating Standards set by the Government Commercial Function. If backed by adequate capacity across the department and implemented effectively, the package of reforms has the potential to ensure a strong commercial orientation and to deliver improved value for money in procurement and contract management.

Box 5: DFID Supply Partner Code of Conduct

DFID’s Supply Partner Code of Conduct introduced in October 2017 at the conclusion of the Supplier Review, formalised voluntary commitments in DFID’s earlier Statement of Priorities and Expectations. The Code of Conduct sets out five overarching requirements of DFID suppliers:

- Act responsibly and with integrity

- Demonstrate commitment to poverty reduction and DFID priorities

- Demonstrate commitment to wider government priorities

- Seek to improve value for money

- Be transparent and accountable

The value for money requirements include a transparent, open-book approach to facilitate external scrutiny, pricing structures that align payment to results and an acceptance of performance risk.

The ethical requirements include avoiding conflicts of interest, regular ethical training of staff and a workforce whistleblowing policy. Suppliers are also required to meet DFID’s requirements on human rights, social responsibility and environmental protection.

Prime contractors are responsible for ensuring that their subcontractors also comply with the code. This provision has caused some concern among suppliers, who may have limited capacity to oversee the conduct of local suppliers, particularly when operating in conflict-affected countries. As we discussed in our review of DFID’s fiduciary risk management in insecure environments, it is generally more helpful for DFID to engage with suppliers on how to manage risks around corruption and aid diversion, rather than simply pass all the risks and responsibilities to the contractor.

DFID’s tender process follows current EU legislation and UK government guidelines

The legal framework for the procurement of goods, works and services within the UK public sector is set down by EU Procurement Directives and UK public procurement regulations. The central requirement of the rules is fair, open and transparent international competition (see Box 6). We find that DFID’s procurement practices are in compliance with the legal requirements and that commercial controls have been tightened to minimise the use of exceptions or waivers to good procurement practice.

Box 6: The legal and policy framework governing DFID procurement

All procurement above the ‘EU threshold’ (currently, £118,133) is governed by UK public procurement regulations and EU Procurement Directives. These rules require fair, open and transparent international competition. The Crown Commercial Services has produced a range of guidance to support implementation of these regulations. The value for money principles applicable to public procurement are set out in two HM Treasury documents: Managing public money (a handbook for public expenditure) and The Green Book (which sets out rules for project appraisal and evaluation). DFID has set out additional principles to guide procurement in its Smart Rules, its Procurement and Commercial Vision and its code of conduct for suppliers.

DFID’s Smart Rules require Senior Responsible Owners to engage with the Procurement and Commercial Department on all procurement requirements with a value above the EU threshold (currently £118,113). The Procurement and Commercial Department is responsible for ensuring that the tender proceeds in accordance with the relevant regulations.

The rules permit government departments to dispense with competitive procurement in certain circumstances. Good practice, however, suggests that these be kept to a minimum.

In the past, the Procurement and Commercial Department granted a large number of exemptions from competitive procurement. Between September 2013, when it started to log waivers, and July 2016, a total of 194 waiver requests were approved, covering contracts and contract extensions with a combined value of over £600 million (see Table 2). The reasons included extreme urgency, the fact that the previous tender procedure had failed or that there was only one suitable provider. These figures were too high, giving rise to value for money and reputational risks.

Table 2: Waivers of competitive tendering granted 2013-16

| Reasons | Total contract value (£ million) |

|---|---|

| Additional works | 288.0 |

| Extreme urgency | 117.3 |

| Failure of previous procedure | 13.0 |

| Research requirement | 19.2 |

| Sole provider | 74.2 |

| Reason not recorded | 118.1 |

| Total | 630.9 |

Source: Data provided by the Procurement and Commercial Department.

In May 2017, DFID established a Procurement Steering Board of procurement experts and other senior staff to tighten its compliance with the rules. The Board must approve all waiver requests. For contract extensions, the request must be made 9-12 months in advance of need, to reduce the need for lastminute waivers. The Board also reviews sourcing strategies for contracts above £10 million and those considered to be strategic. For all programmes under £10 million, a sub-committee of the Board reviews to ensure that the right approach to procurement is being taken.

These measures have reduced the number of contracts awarded without a competitive process to just seven in 2017-18, with a combined value of £148 million, compared to an average of nearly 50 per year in the 2013 to 2016 period. This has significantly reduced the risk of legal challenge and increased competition, which helps to demonstrate value for money.

Cross-government peer reviews confirm improvements in DFID’s procurement approach

In 2016, the Government Commercial Function issued guidance articulating the commercial standards expected of central government departments, with a road map for continuous improvement. The standards are accompanied by an annual peer review process, to facilitate sharing of experience across departments. Each department completes a self-assessment, which is then reviewed by senior officials from other departments. There are 22 indicators, each of which DFID grades on a four-point scale (development, good, better or best). This has now become the primary monitoring system for the continuing development of DFID’s commercial function.

The latest peer review from April 2018 finds that DFID has made considerable progress since a baselining exercise in 2017. It has improved its grade on 11 out of the 22 indicators, making it one of the fastest improvers across government. Two areas, management information and contract management, have been identified as still developing and these will be areas of focus in the 2018-19 improvement plan.

While we have not conducted our own assessment against each individual indicator, the peer review accords with our finding that DFID’s reforms in recent years are moving the department’s commercial approach in the right direction on multiple fronts. We also identified management information and contract management as the main lagging areas (both are analysed in more detail below). Some of the assessments (such as on the commercial pipeline) reflect preparatory work that is not yet operative. However, we concur that there have been improvements across a range of areas, including staffing, strategic sourcing, contractual terms and supplier relationships.

The results suggest that there is still some way to go towards DFID’s objective of having a first-class procurement and commercial service. However, there has been an acceleration of progress.

Table 3: DFID’s progress against UK government Commercial Operating Standards

Source: DFID Commercial Operating Standards performance report, 2018 (not published).

The Supplier Review lent momentum to the reforms but risks having unintended results

In January 2017, the then International Development Secretary initiated a ‘root and branch’ review of supplier practices, which become known as the Supplier Review. Over a nine-month period, DFID suspended much of its routine procurement activity while it assessed how to respond to concerns raised by the International Development Committee and the International Development Secretary.

The package of reforms announced in October 2017 included some that had been in preparation for some time, such as measures on open-book accounting, supply chain transparency and early market engagement. The new measures included:

- Codes of conduct for DFID suppliers and staff, setting out the ethical standards expected of both. Suppliers must declare their compliance with these standards in advance of contact award and on an annual basis.

- Eligible cost guidance, clarifying which types of expenses suppliers are allowed to charge to DFID.

- New standard terms and conditions for DFID contracts, giving DFID new contractual rights to scrutinise costs and profits. Contracts will specify the level of profit that suppliers calculate they will make. DFID will have the right to recover from the supplier any profit achieved above the level agreed.

These measures were intended to address concerns raised in Parliament, by ministers and in the press that DFID did not have sufficient oversight of its contractors and might be vulnerable to anti-competitive practices. The new measures provide DFID with some useful tools to monitor supplier costs and profits. However, we have continuing concerns about the focus on supplier profit levels, as distinct from overall value for money.

First, we are concerned that the underlying problem that the Supplier Review was intended to solve has not been accurately identified. The former International Development Secretary announced her intention to prevent “excessive profiteering” by suppliers. As we noted in our 2017 procurement review, there is no accepted method of determining what is fair or excess profit in any given market. Ensuring a fair procurement process in a competitive market is the usual approach to ensuring that profits are reasonable. The available data (although not definitive) suggested that DFID’s supplier market is not hugely concentrated overall, although it may be in particular countries or niche areas. We were therefore unable to find any hard evidence of excessive profits, and that remains the case.

Second, the new supplier profit clause does not directly address the issue of supplier profit levels. While it gives DFID a contractual right to recover profits over an agreed level, the actual level will vary from contract to contract depending on what the supplier is able to negotiate.

Third, to the best of our knowledge, the clause on recovering supplier profits is unproven in this marketplace. Its enforceability, both in legal and practical terms, will need to be tested. It may create incentives for suppliers to overstate their costs in order to conceal profits, which would work against DFID’s stated objective of increasing transparency. It is not possible at this stage to determine whether a focus on supplier profit will improve value for money or detract from it.

Poor consultation around the Supplier Review has heightened the risk of unintended consequences

To inform the Supplier Review, DFID consulted with other donors, public sector bodies and private sector organisations outside the development sector, in order to identify best practice. It did not consult with its own current suppliers and it put its regular supplier dialogue on hold. DFID told us that this was to allay concerns that discussion with suppliers would appear collusive in an environment of heightened media scrutiny. This lack of consultation caused unnecessary friction with suppliers and, in our view, ran contrary to Cabinet Office guidelines on consultation by excluding a stakeholder group (see Box 7).

Box 7: Consultation – the Gunning principles and Cabinet Office guidance

In 1985, the landmark judgment in R v. London Borough of Brent ex parte Gunning set out principles that government departments should follow when engaging in public consultations:

- Consultation must take place when proposals are still at a formative stage.

- Those involved in the consultation need to have sufficient information to respond meaningfully.

- Adequate time must be given for consideration and response.

- Decision-makers must demonstrate they have taken the responses into account.

These principles are reaffirmed in Cabinet Office guidance on consultation, which also states that consultations should include “the full range of people, business and voluntary bodies affected by the policy”.

It is too early to assess the full impact of the Supplier Review on DFID’s market, but the lack of consultation with the market heightened the risks of unintended negative consequences. In our key stakeholder interviews, we heard concerns that some of the new measures – particularly the supplier code of conduct and the new contractual terms – may discourage smaller firms and NGOs from competing for DFID contracts, potentially reducing competition and therefore value for money. Suppliers were also concerned at the extent of their obligations to ensure compliance with the new rules by subcontractors further down the delivery chain.

So far, these concerns have not resulted in any measurable reduction in competition for DFID contracts. There has been a modest increase in the average number of bids per tender to 3.3 for 2017-18, compared to 2.5 in 2015-16 and 2.9 in 2016-17,46 but it remains short of DFID’s goal of four by April 2019. The improvements appear to have come about through DFID’s increased early market engagement, which stimulates supplier participation, but it is too soon to assess whether the figures will be impacted by the Supplier Review. However, DFID will need to monitor for the emergence of any unintended consequences, which may take time to emerge. To do so, it will need to re-establish its communication channels with current and prospective suppliers, as recommended by our 2017 procurement review.

There was also significant disruption during the process, as normal procurement functions were suspended. While some disruption may be inevitable with a major change process, it could have been minimised with better planning and communication. Some country offices, such as Nigeria, tried to mitigate the impact by using accountable grants to keep programmes operating. Even so, some programmes were significantly delayed as a result – such as the Support to National Malaria Programme (£146.3 million; 2008-16) – leading to gaps in the distribution of key supplies, such as anti-malaria bed nets.

DFID is reviewing its business processes to protect aid recipients from sexual abuse and exploitation

In early 2018, safeguarding aid recipients from sexual exploitation emerged as an area of acute concern following allegations relating to humanitarian operations by NGOs in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. At a Safeguarding Summit in March 2018, DFID announced a number of initiatives to tackle sexual exploitation including a review of its standards and codes of conduct. Some of these initiatives focus specifically on the NGO sector but others relate to commercial suppliers and multilateral partners. The new guidance on value for money for aid-spending departments states: “Safeguards are a vital part of all development and humanitarian programmes. It is essential that robust safeguarding procedures and checks are built into the programme from the outset, and that we are confident that our partners and their collaborators are taking a similarly robust approach.”

It requires Senior Responsible Owners to ensure that partner organisations have appropriate policies and procedures in place to “expressly prohibit sexual exploitation and abuse”, including staff codes of conduct and policies on safeguarding, whistleblowing, risk management and modern slavery.

Pending the results of these initiatives, DFID’s procurement and contract management processes do not currently meet these standards. DFID’s Smart Rules note an overarching obligation to “avoid doing harm” and include a non-exhaustive list of possible unintended negative consequences from aid programming. However, they made no specific reference to sexual exploitation by individuals involved in delivering aid at the time of our review. By contrast, other ethical issues (bribery and corruption, fraud, terrorism financing, modern slavery and staff safety and security) receive much more detailed treatment.

The supplier code of conduct (for both contractors and grantees) and terms and conditions of contracting were adopted prior to the reporting of the Haiti scandal. These contained some relevant provisions, including:

- An overarching obligation to avoid conduct that might undermine DFID’s reputation.

- The requirement for a workforce whistleblowing policy.

- Ethical training for staff, including on modern slavery and human rights.

- Suppliers’ duty of care towards their own personnel, which can include issues of workplace harassment.

- ‘Social responsibility and human rights’ is one of six priority areas that are subject to key performance indicators and compliance checks, to reduce the risk of human rights abuses and exploitation of workers on UK aid programmes.

- Suppliers are required to sign up to the UN Global Compact and to align with standards set down by the International Labour Organization and the Ethical Trading Initiative.

None of these provisions are specific to the risk of sexual exploitation of aid recipients by aid workers. They are much less prescriptive than, for example, DFID’s rules on bribery and corruption, which include a requirement that suppliers inform DFID’s internal fraud investigation unit of any suspicions or allegations through a specified phone number and email.

In the months since March 2018, DFID has appointed internal focal points for staff to report safeguarding concerns. The department is in the process of updating its supplier code and contracting terms and conditions, along with other core business processes, to include more robust safeguarding processes. As part of this process, during August 2018, DFID updated its supplier code to include specific clauses relating to sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment. These will come into effect for new contracts.

DFID needs to ensure clarity and consistency in its guidance

DFID’s procurement approach is set out in a range of internal and external procurement policies. These include a combination of broad principles and mandatory rules, as outlined in the Smart Rules, Smart Guides and other codes of conduct and information notes. The external rules and procedures are published on the ‘Procurement at DFID’ website.

However, as a result of the Supplier Review, DFID’s commercial and procurement landscape is evolving rapidly. A significant number of new processes and policies have been created and incorporated into the Smart Rules or Guides although their impact remains to be seen.

We also find that there are issues with internal consistency within the Smart Rules and Guides – for example, ‘DPOs’ are variously referred to as Department Procurement Officer and Delegated Procurement Officers. DFID’s new contract format also refers to ‘Contract Officers’, but it is not clear to whom this refers. There is also a lack of clarity as to what is mandatory and what is advisory – for example, the front page of every guide states that “nothing [in this guide] should be seen as mandatory” yet many go on to say in the body of the guide “DFID staff must…”. We have concerns about version control, having observed some undated guides and staff using hard copies of out-of-date guides. Furthermore, with increasing numbers of Smart Guides which necessarily overlap, there is increased risk of contradiction or confusion.

Conclusions on relevance

DFID’s commercial model and procurement approach has evolved in response to higher levels of expenditure and increased external scrutiny. While the pace of change was relatively slow up to 2015, it has since accelerated with a package of new initiatives. With the exception of two areas – management information and contract management – we find that these initiatives have addressed, or are in the process of addressing, the most important gaps in DFID’s commercial approach.

Many of its efforts are not yet mature and DFID has some way to go to achieve its objective of a first-class procurement and commercial service. However, we find that the approach is consistent with UK government rules and guidance, and is aligned with ongoing efforts by the Government Commercial Function to drive up commercial standards.

The Supplier Review has lent additional momentum to these reform efforts, as well as introducing new measures designed to increase supplier transparency and accountability. It has clarified the expectations of suppliers and given DFID useful new tools for scrutinising costs. However, we are not convinced that the new contractual provisions on recovering excess profits are the right approach; the ongoing work to increase competition in the supplier market is a more suitable strategy for ensuring that profits remain fair.

We encountered concern among suppliers that DFID’s procurement processes are becoming overly complex, and that this could have negative consequences for competition and diversity. The lack of consultation with suppliers has added to the risks of unintended consequences, which will need to be carefully monitored.

Overall, we judge that DFID’s approach to procurement is appropriate to its objectives, meriting a green-amber score. However, many of the changes are novel and will need to be adjusted in light of experience.

Effectiveness: How well does DFID secure value for money through its tendering practices?

The findings in this section are based substantially on our in-depth review of 44 DFID contracts awarded from 2012-13 to 2016-17. Most of these contracts were let prior to the most recent procurement reforms. Where we note deficiencies in past practice, we also consider whether the causes are addressed in ongoing reforms.

A new strategic sourcing process has resulted in stronger procurement planning

Forward planning for procurement is recognised as good practice across government and industry. When planning programmes, DFID’s Procurement/Commercial Smart Guide recommends identifying early on how resources and risks will be managed, how tenders will be assessed, what contractual arrangements are appropriate and how programme teams will work with suppliers.

For most of the contracts in our sample, we found decision-making about how to approach procurement to be inadequate. In accordance with standard UK government practice, DFID’s prepares a business case at the beginning of each programme, which includes five interdependent assessments to determine whether the programme is justified and offers value for money. They include: a strategic case, setting out the need and rationale for the programme; an appraisal case, showing the expected economic return; and a commercial case, identifying which delivery options are available and which offer the best value for money.

Across our sample of contracts, we found that the majority (82%, or 36 out of 44) set out their strategic and appraisal cases with an appropriate level of detail and a clear strategic rationale linked to DFID’s objectives, some form of cost-benefit or similar economic analysis, and an adequate technical assessment of delivery options. The commercial cases were significantly weaker – only 32% (14 out of 44 contracts) contained a convincing assessment of the services required and the capacity of the market to deliver them, and suitable consideration of the options for sourcing, commissioning and contracting. Most would have benefited from pre-market engagement, to allow a more informed assessment of the market’s capacity to deliver the services required, as well as more exploration of potential routes to market and more discussion of contract management issues. In the absence of informed decision-making, DFID proceeded without clarity as to which commercial option offered the best value for money. In our interviews, DFID staff, including in the Procurement and Commercial Department, acknowledged this shortcoming.

For example, the Ethiopia Land Investment for Transformation programme (£72.7 million; 2014‑20) demonstrated a poor approach to sourcing. The contract was let before the business case was approved, which was poor practice (although the only instance in our sample). The documentation contains no evidence of pre-market engagement, no solid information on market conditions and no clear rationale for the choice of procurement approach or payment mechanisms or for subsequent decisions to extend the contract.

In 2017, DFID introduced a new strategic sourcing process to improve its procurement planning. For programmes above £10 million, programme teams work with the Procurement and Commercial Department to produce a sourcing strategy that analyses the market (including its capacity to supply the services, its competitiveness and whether it is open to new entrants) and makes strategic choices about which procurement approach is likely to offer the best value for money. (Appropriately, contracts under £10 million need only a “light touch sourcing strategy”.) Sourcing strategies are signed off by the Procurement Steering Board and those over £10 million are approved by the Cabinet Office.

Six of the contracts in our sample included a sourcing strategy. We found that their commercial cases and their pre-procurement decision-making were significantly better. There were signs that preparing this analysis in advance had enabled programme teams to bring commercial considerations into the programme design, allowing them to consider not just how best to source the services required, but also how to package the services so as to make the most of what the market had to offer.

The Women’s Integrated Sexual Health (WISH) programme (£209 million; 2017-20) is a pilot programme for the new strategic sourcing approach. This is the second phase of a centrally managed, cross-country fund providing family planning and reproductive health services. DFID conducted four early market engagement sessions – one in advance of the business case to inform programme design and three after to maximise competition. The sourcing strategy includes analysis of supplier capacity and expected levels of competition, based on information collected during the early market engagement sessions. It notes the likelihood of strong interest from NGOs and assesses the implications for the contracting model (especially the appropriate level of risk transfer through payment-by-results contracting, which we discuss below). It analyses the factors that will drive cost and value for money (for example the cost of medical supplies and of reaching hard-to-reach groups) and their implications for the procurement. It assesses options for splitting the procurement into parts (known as ‘lotting’) including by function, country or continent. It assesses the likely impact on competition and quality of delivery, ultimately opting for two multi-country lots in order to ensure an integrated package of services within each country while facilitating cross-county learning. It considers six sourcing options (including through a multilateral channel), opting for a restricted procedure because the deliverables were clearly defined on the basis of experience from the first phase. We find this to be a strong example of structured decision-making around sourcing.

Overall, the introduction of the new sourcing strategies has improved DFID’s understanding of costs, service drivers and market levers. Together with the new eligible cost guidance, this will help to increase transparency in contracting and to ensure that value for money assessments are made on hard evidence.

DFID continues to increase its early market engagement

In the past, DFID programme management staff were cautious about engaging with potential suppliers before a competitive tender, fearing that it would lead to a breach of the rules. In fact, both pre-market engagement (interaction with suppliers and potential suppliers around general issues) and early market engagement (dialogue on procurement options for specific programmes) are recognised as good procurement practice provided that all companies are treated equally and fairly.

Over our review period, DFID has undertaken early market engagement events on a contract-bycontract basis as the need has arisen. The majority of contracts in our sample did not demonstrate strong engagement with the marketplace, although we saw a marked improvement in recent years, confirming our finding from the 2017 procurement review. Early market engagement is now routinely conducted, with details published on DFID’s supplier portal and circulated on Twitter (@DFIDProcurement). Suppliers interviewed during our visits to Tanzania and Nigeria expressed the view that this had improved communication and collaboration.

One indicator of effective early market engagement should be an increase in the average number of bidders for tenders. As noted above, there has been a steady increase from 2.5 in 2015-16 to 2.9 in 2016-17 and 3.3 in 2017-18, against a target of four by April 2019. While it is likely that increased early market engagement has contributed to this, other market shaping initiatives will also be required, as we discussed in our 2017 procurement report.

Our previous review also identified DFID’s failure to publish an accurate pipeline of future procurement opportunities as a significant barrier to market entry. We recommended that DFID accelerate its efforts to address this. In its response, DFID noted that it already used social media and digital platforms to advertise procurement opportunities, but indicated it was working on other changes that it claimed would increase the visibility of procurement opportunities.56 DFID subsequently published an offline spreadsheet of pipeline opportunities dated 31 July 2018. The publication of a pipeline is still not adequate, however, owing to weaknesses in DFID’s management information system (see paragraphs 4.68 to 4.72).

DFID does not always choose the most appropriate procurement process

UK and EU legislation permit a range of procurement approaches (see Table 4). DFID needs to make an informed decision as to which approach is likely to produce the best outcome for each programme. This is a complex judgement that needs to be made by a suitably qualified person as one element of a sourcing strategy. Across our contract sample, one of the consequences of weak sourcing processes was a failure to choose the most appropriate procurement procedure, causing issues later in the lifecycle of the contract.

Table 4: Procurement procedures outlined in Public Contracts Regulations 2015

| Procurement procedure | Details |

|---|---|

| Open procedure | Any party that responds to the tender notice receives a full set of programme documentation and is invited to tender, without pre-qualification or shortlist. The winning bid is accepted without negotiation. |

| Restricted procedure | Interested parties respond to a selection questionnaire. Shortlisted candidates are then invited to bid. Contract negotiations are again prohibited. |

| Competitive dialogue procedure | Following a pre-qualification process, shortlisted candidates are invited into a process of dialogue, during which any aspects of the project may be discussed and solutions developed. Dialogue continues until the procuring authority identifies one or more solutions that satisfy its requirements. It then closes the dialogue in order to invite final tenders. |

| Competitive procedure with negotiation | As with the Competitive Dialogue Procedure, except that the negotiation process can continue until the contract is signed. |

| Innovation partnerships | Commonly used for research and development activities. The procuring authority calls for tenders on the basis a statement of need, without knowing in advance what specific services it requires. There is a negotiation phase before contracts are signed with one or multiple suppliers. |

| Negotiated procedure without prior publication | Contracting authorities enter into a negotiated phase without prior publication where no tenders, suitable tender, requests to participate or suitable requests are submitted by candidates during an open or restricted procedure. |

Our contract assessments, stakeholder consultations and analysis of DFID data show that DFID relies mainly on restricted procedures, although there has been an increase in the number of open procedures since 2015. DFID also makes use of framework agreements, where suppliers prequalify through a competitive procedure and are selected for call down contracts through mini-competitions (see our analysis of DFID’s use of framework agreements in our 2017 procurement review). These are better suited to common goods and services where the requirements can be precisely defined in advance. For more complex contracts where the specific services required are not yet known, it is usually more appropriate to use a negotiated procedure, where the department enters into dialogue with bidders to refine their offer (the ‘negotiated’ or ‘competitive dialogue’ process).

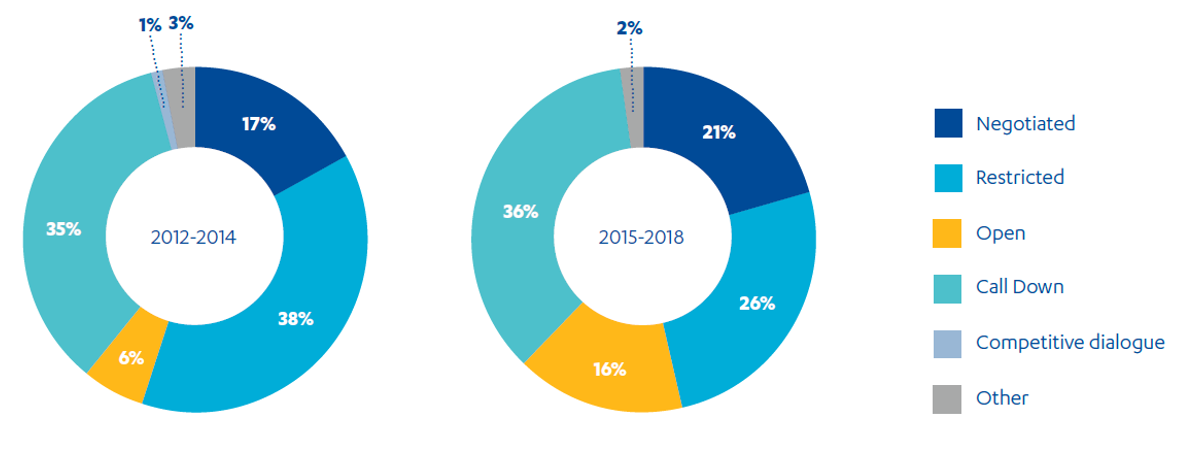

Prior to 2015, only 17% of tenders were undertaken via the more complex negotiated or competitive dialogue procedures (see Figure 4), with a slight upwards trend since 2015.

Figure 4: Proportion of contracts let by procurement procedure type

The use of negotiated options is less than what we would expect to see, given the services that DFID procures. For many of DFID’s programmes, it is not possible to define the required services or intended outputs precisely at the time of the procurement. The supplier is required to complete the design of the programme, as well as implement it. In these circumstances, choosing a negotiated process allows DFID to enter into dialogue with two or more potential suppliers, to build up a stronger understanding of the expertise they offer, the options for scoping the services and what commercial terms are likely to be most appropriate (see Box 8 for a positive example). By contrast, when DFID opts for an open or restricted procedure, it is required to define the service or outputs in an overly restrictive way, requiring costly contract amendments. While the negotiation process can be time consuming, in the right circumstances it can lead to better value for money.

One factor that may be restricting the use of negotiated processes is unrealistic timetables. For the first phase of the Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) (£672 million; 2012-18), the initial procurement of the fund manager failed to produce a strong enough candidate, requiring the tender to be re-run. To minimise the delay, DFID opted for an accelerated restricted procedure. The successful bidder was then given less than two weeks from contract award to the launch of the first funding window to make key decisions about governance arrangements and funding mechanisms. According to an external review, this “caused confusion for applicants and grantees that had knock-on effects throughout the commissioning and baseline process”. We found other instances where DFID prioritised adhering to timetables over good procurement practice.

It is too early to assess whether the new strategic sourcing process will resolve this issue, but in principle it is the right way to ensure better procurement choices.

Box 8: A positive example of sound procurement choices

The Partnership to Engage, Reform and Learn programme (£39 million; 2016-21) supports governments in Nigeria at the federal and state levels with core planning and budgeting processes. It is a complex programme operating in a high-risk environment. The business case summarises the results of research into the capacity of the supplier market and opts to split the procurement into three components in order to attract suppliers with a range of strengths. DFID decided to follow a negotiated procedure, giving it an opportunity to hone the programme design in dialogue with potential suppliers before letting the contract. The commercial case evidences structured decision-making around the procurement method. While it is never possible to link programme performance directly to procurement, DFID Nigeria tells us that the programme has so far exceeded its output targets and is expected to achieve good results.

DFID has built up its commercial capability, but this will need to be an ongoing process

In 2015, DFID undertook an internal commercial capability review, overseen by the Chief Commercial Officer and HM Treasury. This review looked at commercial capability both in the Procurement and Commercial Department and across the organisation, against the competencies set out in DFID’s Commercial Maturity Model (see Box 9). It identified significant gaps in DFID’s capacities and capability.

Since then, DFID has made a sustained effort to build its procurement capability. It has substantially expanded the size of the Procurement and Commercial Department, from 41 staff in 2010-11 to 121 in August 2018. It has made efforts to recruit more senior procurement experts, including from the private sector. It has provided commercial leadership training to all senior civil servants and appointed commercial delivery managers to work with programme teams. It introduced a new Procurement Steering Board to oversee DFID’s compliance with commercial controls and to guide organisational learning and the development of greater commercial acumen. It has also elevated the procurement function within the departmental hierarchy, with the head of procurement now a member of the Investment Committee, which is responsible for ensuring value for money across the department. Through our key stakeholder interviews, we found that the rationale for and objectives of these reforms were well understood across the department and supported by senior management.

Box 9: Building DFID’s commercial maturity