UK aid’s approach to youth employment in the Middle East and North Africa

Purpose, scope and rationale

The purpose of this review is to assess whether the UK has been relevant and effective in promoting employment opportunities for young men and women in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

The review will cover programmes that include among their objectives support for youth employment in the MENA region. The portfolio under review includes programmes where youth employment is a direct objective, or those which promote youth employment as a component of other objectives, such as programmes that promote stability or support refugee populations. The portfolio covers Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPTs), Syria, Turkey, Yemen, Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. Our scope covers programming over the five years since the publication of the UK aid strategy (from 2015 to 2020), and includes aid spent by the former Department for International Development (DFID) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) – merged in September 2020 to become the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) – and other government departments, including by the UK’s development finance institution CDC. As our review is primarily of programming undertaken before the DFID-FCO merger, our findings will distinguish where appropriate between the two departments, while our recommendations will be addressed to the FCDO.

Over half the population in the MENA region is under 24 years old and a quarter of the young people in the labour force are unemployed. Lack of female participation in the labour market in the region is a particularly acute issue, with some countries having up to 60% of young women not in education, employment or training (NEET). A large proportion of these young unemployed people are also highly educated, with university graduates making up nearly 30% of the total. The youth employment challenge is exacerbated by both demand-side failures, such as a lack of access to finance, restrictive business regulations and cronyism which reduce the numbers of employment opportunities, and supply-side failures, such as education and skills that do not match labour market needs, making it harder for young people to compete for jobs.

Overall, the MENA region is characterised by economic and geopolitical instability. Economies face structural imbalances including large, inefficient public sectors, uncompetitive business environments and governance challenges, as well as high youth unemployment. They are vulnerable to shocks – including the current shocks created by COVID-19 and the simultaneous oil price shock impacting stability. The World Economic Forum highlights further challenges including widespread corruption in the job market, lack of economic diversification and a social contract dependent on public sector jobs.

Within this context, sustainable economic development and poverty reduction in the region are closely linked to the need to create decent work opportunities for young people. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) call for a reduction in the number of young people who are NEET by 2020. “Decent work and economic growth” is the focus of SDG 8, and SDG 5 promotes gender equality, including in the economy. Women’s workforce participation rates are not only low in MENA, but 80% of those with work are in vulnerable employment and women face a range of legal, institutional and cultural challenges to their participation in the labour force. Youth unemployment is also addressed in the UN Youth Agenda 2030, which highlights “support to young people’s greater access to decent work and productive employment” as one of its four priority areas.

Although the UK government does not have an explicit strategy for promoting youth employment in the region, job creation is referenced directly in the cross-government UK aid strategy, and youth employment in DFID’s Youth Agenda and Economic Development Strategy. UK development aid in the region has focused on broader economic development and poverty reduction goals, primarily economic and fiscal stability, rather than on creating jobs for young people. We see the review of youth employment in MENA as representative of the broader engagement on economic stability in the region, one where the outcomes of programmes, in terms of jobs created, are straightforward to identify and track. Indeed, since 2011, UK government assessments and policy documents concerning the MENA region have increasingly linked instability, fragility and vulnerability with economic grievances, particularly unemployment. These include the former DFID’s business plans for the region since 2015, where youth employment is highlighted as a priority outcome in some country programmes, including Jordan and North Africa. While economic stability more broadly is a common objective in the region, since 2015 £2.4 billion in UK aid has been invested in programmes that are relevant to youth employment in the MENA region. In many cases, the promotion of youth employment is only one component of wider programmes, making it impossible to calculate the level of spending specifically on youth employment.

COVID-19 adjustments

The design of this review has been impacted by the global coronavirus pandemic in the first half of 2020. As a result, the initial design was developed based on publicly available information on the UK government strategies and aid portfolio (Devtracker) rather than direct stakeholder engagement. As we move into the research phase, a decision has been taken that no travel will take place during this review to avoid the risk of doing harm to stakeholders and the review team. The review team will therefore use the opportunity to engage a broader range of stakeholders than would otherwise be possible using electronic means. Other implications to methodology are discussed in Section 6.

Background

The series of popular uprisings across the MENA region in 2011 that become known as the ‘Arab Spring’ brought specific attention to the youth employment challenge. The uprisings occurred against the backdrop of relatively slow economic growth in many countries, combined with rising inequality. With five million new workers entering the market every year, unemployment, particularly among young people, became a source of discontent. The Arab Spring protests highlighted lack of economic opportunity as a major grievance, with youth and women being particularly marginalised in the labour markets of the region, as well as the wider political and economic context.

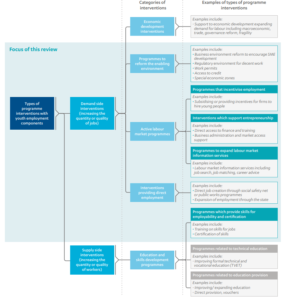

The range of potential interventions to address youth unemployment is broad. The typology in Annex 1 sets out our working typology of interventions. It was developed by the review team for the purposes of mapping the scope of this review and draws on a broad range of literature about youth employment programming that will be included in the literature review (to be published alongside the final report). Our working typology of potential interventions includes:

1. Measures to promote the demand side of youth employment, to increase the quality or quantity of jobs,

including:

- measures to promote economic development and reform the business environment

- active labour market programmes (ALMPs) including employment subsidies, support for entrepreneurship, labour market information or job search services

- direct job creation programmes, such as through public works.

2. Measures to address the supply side, by improving the capacity of young people to compete for jobs, such as through support for education and training.

The UK official development assistance (ODA) portfolio encompasses both demand- and supply-side measures. Many of the programmes in the portfolio seek to promote wealth creation by tackling barriers to economic development. This has included supporting the business environment and improving access to financial services, as well as more direct support to job creation and improving the supply of labour. Our review will address defined elements of the typology, including business environment reforms, ALMPs, job creation programmes and skills for employability programmes. To ensure we focus on the most relevant elements of the typology and ensure a manageable portfolio, we will exclude broad economic development programmes as well as education or technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programmes.

Mapping the UK aid approach to youth employment

Although there is no single strategy governing the UK’s contribution to youth employment in the region, the 2015 UK aid strategy emphasises the role of global prosperity in combatting endemic poverty and the need to overcome barriers to prosperity through interventions that are tailored to national and regional contexts. Youth employment is a key element of the prosperity challenges faced by the region. Further, the 2015 National Security Strategy sets out job creation as an overarching goal of the UK’s aid programme:

“We will help to address the causes of conflict and instability through increased support for tackling corruption, promoting good governance, developing security and justice, and creating jobs and economic opportunity. These are essential elements of the golden thread of democracy and development, supporting more peaceful and inclusive societies.”

This goal is further elaborated in the former DFID’s 2017 Economic Development Strategy, which identifies the need to tackle systemic barriers to employment for youth and women. The strategy highlights the links between youth unemployment, youth political marginalisation and instability in developing countries as damaging to UK interests, and emphasises the potential for young people to be drivers of change. The 2016 DFID Youth Agenda further highlighted the role of young people as both agents and advocates for sustainable development, and committed DFID to including youth voices and concerns in all aspects of its programming.

UK aid strategies in some countries of the MENA region also highlight the importance of youth employment. For example, as yet unpublished Country Business Plans for 2020-21 list jobs for youth as a priority outcome for Jordan and North Africa. Joint UK government analyses to inform planning in Jordan, Tunisia and Egypt emphasise youth employment as a significant challenge. This has been an ongoing area of importance. Earlier strategic documentation highlights the theme too. The former DFID country profiles of 2018 highlight employment as a significant challenge in Jordan, Lebanon and the OPTs.17 DFID’s 2011-16 MENA Operational Plan, for example, notes that “unemployment in MENA is amongst the highest in the world, with youth unemployment particularly severe.”18 It goes on to prioritise economic development programming, targeting results including the creation of jobs, financial support and business advice to entrepreneurs and skills development. However, the plan stops short of explicitly targeting youth for this support. Country-specific operational plans for 2011-16 for Yemen,19 the OPTs20 and Lebanon21 all mention economic growth and supporting jobs and livelihoods as main objectives, but also stop short of explicitly targeting youth in their work.

From the UK aid portfolios in the region, we have identified 115 programmes with a total value of £2.4 billion which include a youth employment element within the scope of our review (referred to as “the youth employment in MENA portfolio”, and as identified in the focus of our review typology – see Annex 1). The programmes vary widely in size and scope, ranging from large (over £225 million) programmes of humanitarian support to refugees in the Middle East with specific components on youth employment, to small and focused interventions (such as British Council support to skills training). While all 115 programmes include components from our youth employment typology, 60% include a primary or secondary focus on either youth or employment, with only 20% of programmes focusing explicitly on youth employment (16% by value).

Figure 1 maps the youth employment in MENA portfolio by country. Expenditure has been heavily focused in the Middle East, accounting for 76% of the portfolio, with North Africa accounting for just 6% and the remainder in the form of cross-regional programming. This is consistent with UK priorities: the former DFID’s 2011-16 Operational Plan for the Middle East and North Africa Department notes that Yemen, the OPTs, Syria, Jordan and Lebanon were its priority countries within the region.22 The Middle East encompasses larger programmes of support for Syrian refugees that have youth employment as a secondary focus, whereas the North Africa programmes include much smaller interventions.23 The majority of programmes in the portfolio have been delivered to date by DFID (78% of spend), with 9% from the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), 5% from the Prosperity Fund and 4% from CDC and the FCO respectively. The programmes delivered by DFID and FCO are now expected to come under the FCDO. Significant features of the portfolio include high shares of programming being delivered jointly with multilateral organisations (62% of the portfolio by value), working in conflict or fragile contexts (57%) or working with refugee populations (41%).

Figure 1: Share of value of youth employment in MENA portfolio by country

Table 1 maps the youth employment in MENA portfolio by categories and examples of youth employment interventions, in accordance with the typology set out in Annex 1. Table 1 shows that the majority of spend on youth employment in the region is formed of programmes relating to enabling environment reform or skills for employability. Programmes to expand labour market information services form the smallest share, although these programmes tend to have a lower cost (for example, the 6% share includes 11 distinct programmes).

Table 1: Share of the youth employment in MENA portfolio by intervention

| Category of intervention | Examples of types of interventions | Percentage share of portfolio value |

|---|---|---|

| Programmes to reform the enabling environment | 59% | |

| Active labour market programmes | Programmes that incentivise employment | 26% |

| Interventions which support entrepreneurship | 25% | |

| Programmes to expand labour market information services | 6% | |

| Programmes that provide direct job creation | 27% | |

| Education and skills development programmes | Programmes which provide skills for employability and certification | 36% |

Note: These shares do not add up to 100% as some programmes address more than one intervention typology category

Review questions

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, coherence and effectiveness. It will address the following questions and sub-questions about programming relevant to youth employment:

Table 2: Our review questions

| Review criteria | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: Is the UK’s approach to promoting youth employment in MENA relevant to needs? | • Is UK aid’s approach to promoting youth employment responsive to the context? • To what degree does the UK government’s approach to youth employment aim to reduce drivers of fragility and conflict? • How well is the UK’s programming aligned with the needs and priorities of the young people expected to benefit? • To what extent are UK aid programmes based on good evidence and learning on ‘what works’, and contributing to further evidence? |

| Coherence: How coherent is UK aid’s approach to promoting youth employment? | • How well is the UK’s work on youth employment in the region coordinated across departments? Is the overall approach coherent? • How well has the UK worked with multilateral and other development partners to promote youth employment in MENA? |

| How effective is the UK’s support to youth employment in MENA? | • How well has UK aid contributed to youth employment in the MENA region, and to what degree have the UK’s efforts supported the goals of economic development and reducing fragility? • How well do UK aid programmes on youth employment deliver on gender and inclusion objectives in MENA? • Where UK aid has contributed to improving employment outcomes, how well have they been sustained or how likely are they to be sustained? |

Methodology

The methodology for the review will involve five main components, each used to inform and triangulate findings in the others. The methodology includes a field component (although this will be conducted remotely due to COVID-19 constraints) and will also make extensive use of FCDO programme data and remote data gathering. The review will draw on expert and stakeholder opinion, including that of young people from the MENA region, and a robust literature review. Each component is detailed below, with Figure 2 representing how the methods fit together.

Figure 2: Methodology

Component 1 – Strategic review: We will undertake a desk-based mapping exercise of relevant policies, strategies and guidance, a broader document review and key informant interviews (KIIs) with relevant UK government staff, particularly from FCDO, supplemented by selected interviews with academic experts and other development partners. To address our review questions on relevance, we will trace the evolution of UK strategies and the focus and composition of aid directed towards youth employment goals. This will include reviewing how strategies at global, regional and country levels address youth employment in MENA, and whether they are based on sound theories of change and map any important changes over time. We will assess the extent to which strategies, approaches and programmes address employment challenges in MENA based on sound understanding of the context, including whether they are designed based on clear analysis of the expressed needs of the target groups, reflect and respond to rapidly changing local contexts across the region, and draw on evidence of ‘what works’ in promoting youth employment. We will examine the degree to which the UK approach aims to reduce fragility and conflict (and the extent to which any such efforts reflect literature review findings and current best practice). To address coherence, we will examine how the UK coordinates its youth employment work with other actors in MENA, as well as cross-government coordination. We will identify any mechanisms which exist to share evidence and learning within and between the responsible departments (and externally) and examine their approach to working with multilaterals on youth employment, assessing the quality of their multilateral partnerships.

Component 2 – Literature review: Our literature review, which will be published alongside the report, will outline evidence of ‘what works’ in youth employment programming globally, as well as specific evidence from the MENA region, where available. It will explore the balance of evidence linking increased youth employment to outcomes and impacts such as economic development and reducing fragility. The review will identify the causes of youth unemployment in the MENA region, placing the UK’s strategy and interventions in their broader social and economic context. It will offer a concise summary of the key issues and conclusions emerging from both academic and ‘grey’ literature, commenting as appropriate on the state of knowledge and the quality of evidence underlying the main conclusions. The review will make full use of existing literature reviews and summaries. The literature review will incorporate relevant published research already undertaken for the UK aid programme or other development actors.

Component 3 – Detailed review of specific programmes: We will conduct case studies of a sample of 19 programmes and projects, including a document review and selected virtual KIIs. We will explore the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of each programme, identifying issues for later exploration during the fieldwork phase. The sampling approach below describes how the portfolio will be sampled to ensure we review a mix of interventions addressing different aspects of our review questions. These case studies will also offer the opportunity to gather external perspectives on the added value of UK aid programming in tackling youth employment. Each case study will contribute to answering all of our review questions, enabling us to triangulate the data we are collecting with data from other sources. Through the case studies, we will also analyse the extent to which the portfolio has addressed gender and other social issues, for example around equity/inclusion and youth voice and agency, in a consistent and coherent way, and identify any gaps in approach. We remain reliant on the availability of documentation for the detailed reviews.

Our detailed reviews will include an assessment of how the UK has targeted value for money through each programme, identifying any gaps. We will supplement this with analysis of the cost-effectiveness of each programme. Where data is available in programme documentation, our analysis will compare job creation results achieved through different programme types and their unit costs. These will be compared with available benchmark data from other development partners, including that identified through the literature review.

Component 4 – Country case studies: We anticipate conducting two case studies of MENA countries, in Jordan and Tunisia, to facilitate our assessment of the range and scope of youth employment-focused programming and to allow for more detailed assessments and in-depth interrogation of relevance, effectiveness and coherence. Case studies will be conducted remotely, using telephone and electronic communication tools as a result of the current pandemic and to ensure that the review does not endanger the stakeholders we are consulting. KIIs will be held with FCDO staff, government officials, local academics working on youth employment dynamics, workers’ unions and associations where appropriate, civil society and other development partners, as well as direct consultations with target populations (ie young people – see Component 5). In light of travel restrictions, we will also take the opportunity to interview stakeholders more broadly: we will conduct additional country research into three further countries with enhanced stakeholder engagement in Turkey, Lebanon and Egypt. This enhanced stakeholder engagement will focus on interviews with FCDO staff and main implementing partners. Interviews will enable the review team totriangulate and deepen the analysis emerging from the strategic review and the case studies. In-country stakeholder interviews will also allow the team to assess how well the UK’s approach aligns with national strategies and priorities.

The in-depth country case studies will enable us to assess how well UK aid programmes and projects reflect best practice and contextual needs in relation to gender equity, inclusion and other social concerns (such as equity, youth voice and agency, disability and rural/urban balance). We will look at any project mechanisms in place for soliciting feedback from target groups and the degree to which any such feedback is used to inform programme quality.

Component 5 – Citizen voice: A core component of our methodology is capturing the voices of citizens who are intended to benefit from the UK government’s portfolio in the region. To do this, we will combine the use of several tools to explore the needs of young people in the region and their perspectives on the UK’s programmes. This will help us to highlight the voices of target groups of young people in the region as well as to triangulate our findings from other components of the methodology. It will also allow us to illustrate our findings with ‘real life’ examples. Direct feedback may also bring out any unintended consequences of UK programming.

In addition to seeking feedback from individuals targeted by programmes in our sample, we also propose a limited degree of engagement with a broader constituency of young people to explore some of the wider social and cultural challenges around youth employment in the region. This may include issues from our initial review of literature including the employment preferences of young people themselves (such as for public versus private sector employment) and reasons driving the low labour force participation of women. We will undertake citizen engagement in one or more of our case study countries. This will be done remotely through a combination of working with in-country researchers and intermediaries as well as through electronic means. We will identify and engage with youth participants in two or three appropriate projects from our sample. Although not representative, we anticipate that the data collected from these groups will triangulate results data from other sources and help us to illustrate findings from the primary data with more personal and nuanced perspectives. The exact questions for citizens will be determined after we have completed our detailed project reviews, informed by the specifics of each project. We will work with local consultancy teams in these two countries to manage implementation of e-focus group discussions and individual interviews. A full design of this component will follow the detailed reviews and will include detailed risk assessment, research ethics and safeguarding protocols as well as data collection instruments before beginning the component.

Sampling approach

Two approaches to sampling have been employed: to identify the countries for case study reviews and to identify the programme list for analysis under the detailed review component. For country case studies, we have selected the countries with a large share of the youth employment in MENA portfolio in terms of value, a large number of individual programmes of relevance and where youth employment has featured most strongly in the UK government’s planning documents. Our aim was to ensure representation of each sub-region of the Middle East and North Africa. Although North Africa as a whole only accounts for 6% of the portfolio by value, there are smaller interventions in the sub-region that are of particular interest for answering our review questions. We have selected Jordan for the Middle East and Tunisia for North Africa. Because of the breadth of focus of the portfolio, we have chosen to add enhanced stakeholder engagement in Egypt, Lebanon and Turkey. Overall, our case studies and country engagement will encompass 40% of the portfolio by value.

At the more precise level of sampling programmes for the detailed review component, multi-criteria analysis was conducted to identify a stratified sample of 19 programmes reflective of the broad portfolio and accounting for 52% of the overall portfolio value. Box 1 highlights the sample and the criteria used to select it. The sample focuses on Jordan (five programmes with a combined value of almost £389 million), Lebanon (four programmes with a combined value of £74 million), Tunisia (two programmes with a combined value of almost £28 million) and Egypt (one programme with a value of £20 million). Our sample also includes programmes in Turkey, Yemen and the OPTs, plus two regional programmes covering both the Middle East and North Africa.

Box 1: Sampling approach

All programmes in the portfolio were scored according to sampling criteria to generate a stratified sample to encompass: shares of the portfolio by typology category, whether programmes work with multilaterals, whether they have a primary or secondary focus on youth employment, whether they work in contexts of fragility or with refugees, whether they have a specific focus on gender and social issues, whether they have evaluative material available and the share of different UK aid agencies leading programmes (before the FCDO merger).

Our sample includes 19 programmes, worth half of the full portfolio (£1.2 billion (52%) out of 115 programmes in the full UK government portfolio worth £2.4 billion).

We have sampled a mixture of youth employment approaches across the typology categories – with more enabling environment and skills for employability programmes, commensurate with higher portfolio shares (see Table 1).

Twelve of our sampled programmes are former DFID programmes, five are CSSF, one is a former FCO programme and one a Prosperity Fund programme. Our sampling reflects the balance of the overall portfolio, but we have placed emphasis on CSSF because in some of the countries sampled (notably Tunisia and Egypt) CSSF has been the main funder of programmes covered by our review.

Limitations to the methodology

The COVID-19 pandemic places substantial additional limitations on our methodology. This section highlights these limitations, identifying those which predate COVID-19 and others that relate directly to the pandemic. We outline how we will minimise the impact of these limitations and conclude with a statement of residual limitation.

Pre-existing limitations

1. Scope of subject matter and lack of overarching UK government strategy: Youth employment is a wide topic encompassing a broad range of programmes (see Annex 1 for our typology). There is no single UK strategy on the subject for this region, making it more difficult to frame the boundaries of the review and ensure a representative sample. We have addressed this challenge by using youth employment as an entry point to economic stability and taking a broad definition of youth employment interventions, encompassing broader economic reform programmes in our sample and prioritising the most commonly used intervention types across the typology in our sampling framework.

2. Data limitations: Although some programmes within our scope focus primarily on youth employment, much of the relevant programming includes a youth employment objective among other goals. This will make it difficult to attribute any results achieved (on youth employment, gender etc) to individual programme components on youth employment. Programme design documents, results frameworks, periodic reviews and, where available, evaluations may not explicitly or sufficiently explore or disaggregate youth employment results from other activities, making it difficult to explore our review questions on, for example, gender equity, intergenerational fairness and disability. Our approach to sampling has taken the variety of programme types into account and we have coded programmes for impact, gender and other relevant variables. As such, we have endeavoured to select a broad and representative range of programmes

for analysis.

3. Safeguarding and due diligence: We are not conducting an audit of the portfolio. We will not therefore be analysing the due diligence processes employed by the UK government and cannot warrant that programmes reviewed meet safeguarding and due diligence requirements. As per FCDO guidelines, we will report any suspicions of aid diversion, fraud, money laundering or counter-terrorism finance to the Counter Fraud and Whistleblowing Unit. The review will be conducted in accordance with FCDO’s safeguarding guidelines, and we will report any safeguarding concerns if we uncover them.

4. Understanding sustainability and value for money: Preliminary research suggests that youth employment projects struggle to capture and analyse value for money, and to measure sustainability of change. This challenge is not unique to the UK government. The lack of data and research on this matter may complicate our analysis of the efficacy of existing methods and our recommendations on how value for money could be approached in future. In our literature review, we will highlight where and how sustainability and value for money have been measured and identify best practice in this regard. This provides a basis for our subsequent UK government-specific analysis which can only be as in-depth as data availability allows.

COVID-19-related limitations

5. Understanding stakeholder views and voice of target groups: The coronavirus pandemic and the cancellation of country visits risks impeding our ability to understand the broader views of stakeholders, including the voice and priorities of our target groups of young people in the region. This impedes our ability to address review questions related to the relevance and responsiveness of programming (including to young people’s priorities), as well as their coherence and effectiveness. We will use virtual meetings where possible to engage partners in country and are exploring options for using local partners to conduct consultations with target populations.

Residual limitations: The broad scope of this review will impact the generalisability of findings. Although the COVID-19 restrictions on engagement with the UK government and travel will be managed where possible, to ensure continued progress, they are likely to impact on the timing and cost of the review and limit the scope of stakeholder consultation.

Risk management

We provide an overview of core delivery risks below.

Table 3: Risk and mitigation

| Review criteria | Risks |

|---|---|

| Access to information - classification | Some data needed for this review is sensitive and classified. There are risks that the review team will not be able to access all required restricted information or that some data will not be able to be included in a public report. To manage these risks, all team members will be security cleared and we will liaise with FCDO to agree protocols on access to and use of restricted information, while strictly respecting the UK government information security guidance. |

| Access to information – interviews | Due to COVID-19, there is a risk that we will not be able to engage with UK government counterparts as closely as for previous ICAI reviews. We will therefore focus on remote data collection and interviews through electronic means. The risk remains that such methods limit openness and our ability to build professional rapport with interviewees. Where possible, we will endeavour to engage interviewees in person and will limit questions to those essential to triangulate findings and address gaps from documentary reviews. |

| Review delays | The COVID-19 pandemic is severely affecting timelines, with the initial engagement with the responsible departments delayed to the end of the design phase. We have flexed our work plan to allow for these access challenges and we will monitor the situation closely and adjust timelines as necessary. We will also endeavour to reach early agreement with the responsible departments on the protocols for engaging with them, and with implementing partners, so as to minimise the demands on their time while retaining the access to information we need for the review. |

| Challenging context (global pandemic, economic crisis and changing UK aid architecture) | The current context will make it difficult to ascertain the effectiveness of youth employment programming, particularly from earlier in the review period. Current concerns relate to COVID-19, economic crises (as well as the broader crisis in Lebanon) and, for the UK government, changes to the UK aid architecture. We will mitigate this risk by reviewing original documentation for each programme and seeking to identify the stakeholders who were involved at the time. However, the consultation on citizen voice in particular may well reflect current concerns of youth in the region. |

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI commissioner Tarek Rouchdy, with support from the ICAI secretariat.

Both the methodology and the final report will be peer-reviewed by Nader Kabbani, the director of research at the Brookings Doha Center. Mr Kabbani is a well-published expert on economic development and labour markets in the Middle East, focusing on youth employment.

Timing and deliverables

Due to the interruption of business as usual across the UK government because of the COVID-19 crisis, the review timeline has been adapted. The design phase therefore took place over an elongated period, running until September 2020. The standard review timeline for data collection, analysis and reporting begins in September 2020 and runs to publication of the final report, expected in June 2021.

| Review criteria | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Design | Approach paper: September 2020 |

| Data collection | Virtual country case studies: October/November 2020 Evidence pack: December 2020 Emerging findings presentation: January 2021 |

| Reporting | Final report and literature review: June 2021 |

Annex 1: Typology of youth employment interventions

This typology of youth employment interventions was developed by the review team for the purposes of this review. It draws on a broad range of literature about youth employment programmes, which will be outlined in the forthcoming literature review. It has enabled us to identify and sample the youth employment in MENA portfolio and will allow us to compare substantially different programmes across the region. The below graphic sets out this working typology and highlights the 115 programmes identified as the portfolio that will be the focus of our review. We have excluded broad economic development programmes and education or technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programmes in order to focus on the most relevant elements for this review.