A preliminary investigation of Official Development Assistance (ODA) spent by departments other than DFID

Executive Summary

This investigation covers a selection of departments that have not yet been reviewed by ICAI. It responds to concerns expressed by various stakeholders that the scaling up of UK aid to 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) might be accompanied by substantial increases in non-DFID Official Development Assistance (ODA) and that this might, in turn, compromise either the quality or the pro-poor orientation of the UK aid programme.

In this report, we map the distribution of UK ODA across departments and how it has changed in recent years. We then examine ODA activities by eight departments. (We exclude the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and contributions to the International Climate Fund, which we have reviewed separately, as well as devolved expenditure by the Scottish and Welsh Governments, which falls outside our mandate.) Our scope covers £140 million of 2013 ODA by eight departments. We examine whether their objectives are clear and appropriate for the UK aid programme and whether they have management systems in place to ensure effective delivery and to measure results. We also look briefly at the process used to compile UK ODA statistics.

This is not a full ICAI review. We have not examined individual activities in the field to assess their effectiveness and value for money. We have not, therefore, scored individual programmes against our standard assessment framework.

Findings

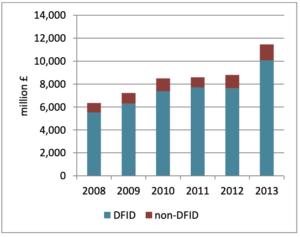

Over the past five years, UK ODA has nearly doubled, reaching £11.5 billion in 2013. Through this period of rapid scaling up, the share of non-DFID ODA has remained relatively constant, within the range of 10-13% of the total. Non-DFID ODA reached £1.4 billion in 2013 – an increase of £472 million since 2009. Most of this increase came from the establishment of the International Climate Fund and expansion of the Conflict Pool.

The scaling up of UK aid has not led to an increase in the proportion of non-DFID ODA. Nor has it led to any overall loss of pro-poor focus to UK aid – even though, unlike DFID, other departments are not bound by the International Development Act and its stipulation that aid must be ‘likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty’.

The activities examined here are all ODA eligible and appropriate to the UK aid programme. Now that the UK has achieved the ODA target of 0.7% of GNI, however, future increases in non-DFID ODA could lead to corresponding reductions in DFID’s budget. We propose to keep this issue under review.

The non-DFID ODA we examined fell into four categories. Programmable ODA (£52.3 million) refers to development initiatives with distinct objectives and management arrangements. It includes research on medical issues affecting developing countries, funding on biodiversity and a legacy programme from the London Olympics that promoted sport and physical education around the world. In each case, we found that the objectives were clear and appropriate and the management arrangements sound.

Departmental activities classed as ODA (£35.3 million) includes support for asylum-seekers during their first year in the UK and a selection of Ministry of Defence activities, including training programmes in developing countries. While refugee support costs are not obviously a contribution to international development, it is standard international practice to report them as ODA.

Debt relief (£30.4 million) refers to debts owed to the UK’s Export Credits Guarantee Department by developing countries that are written off under international debt relief schemes.

Finally, multilateral contributions (£22 million) relate to membership contributions to the budgets of international organisations.

DFID has no mandate to oversee, co-ordinate or control the quality of ODA spent by other departments. Its formal role is limited to compiling the UK’s annual ODA statistics. As co-funder of the major aid programmes examined here, it does, however, provide some support on grant-making and results measurement. We found DFID’s checking of other departments’ ODA returns to be appropriate and proportionate to the risks and expenditure involved. In borderline cases, DFID’s approach to ODA reporting remains appropriately conservative.

While UK ODA data are published in various forms, there is no single place where stakeholders can find a clear explanation of the amounts and objectives of non-DFID ODA. This feeds concerns among stakeholders about its appropriateness and quality.

Recommendation

DFID should request ODA-spending departments to accompany their annual ODA returns to DFID with an information note describing, in simple terms, the main activities or types of activity claimed as ODA. DFID should include this information in an annex to its Statistics on International Development in order to enhance transparency.

1 Introduction

Purpose

1.1 From 2012 to 2013, total UK spending on Official Development Assistance (ODA) increased by £2.7 billion, as the UK Government fulfilled its commitment to reaching the international ODA target of 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI). During this period of increase, there was concern among stakeholders that this rapid scaling up of UK aid would lead to an increase in the share of UK ODA spent by departments other than DFID. There were concerns that this might, in turn, compromise both the quality and the pro-poor focus of UK aid.

1.2 There is relatively little information on non-DFID ODA in the public domain. While DFID’s main statistical publication, Statistics on International Development,1 includes a breakdown of ODA by department and a brief explanation of its purpose, this disclosure is not sufficient for external scrutiny. This relative lack of transparency, as compared to the large amount of information available on DFID expenditure, has contributed to stakeholders’ concerns.

1.3 We decided, therefore, to conduct an investigation into ODA expenditure by other government departments. We set out to determine whether scaling up had encouraged other departments to increase their ODA and whether inappropriate items were being reported as ODA. We also set out to check whether ODA spent by a number of departments had appropriate objectives, management arrangements and systems for measuring and reporting on results.

1.4 This report provides a convenient summary of ODA expenditure by a range of departments, to increase transparency and accountability. It also assists us in identifying categories of UK ODA that may call for more detailed scrutiny in the future.

Scope and methodology

1.5 In past reports, we have already examined some of the major categories of non-DFID ODA, including the inter-departmental Conflict Pool,2 other Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) programmes3 and the International Climate Fund (ICF),4 to which the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) is a major contributor. To avoid duplication of those reviews, we decided to exclude FCO and DECC from the scope of this investigation.

1.6 Non-DFID ODA (see Figure 3 on page 4) includes expenditure by 12 departments or agencies and a number of items that are not attributed to the budgets of any specific department. The latter items are explained in Figure 5 on page 6 but are not further investigated in this review, as they do not give rise to any particular concern regarding ODA eligibility or management processes. We also excluded devolved ODA expenditure by the Scottish and Welsh Governments, as this falls under the responsibility of the regional parliaments and outside our mandate.

1.7 The remaining categories of ODA are those covered by this investigation (see Figure 1 on page 3). In 2013, they comprised £140 million in expenditure by eight departments. This represents just over 1% of the UK’s £11.5 billion of ODA for 2013.

1.8 Our methodology for the investigation included:

- consultations with DFID, other ODA-spending departments and external stakeholders;

- a mapping of non-DFID ODA and how expenditure patterns have changed in recent years;

- a review of UK Government systems for identifying and reporting on ODA; and

- a light-touch investigation of significant items of expenditure, covering:

- whether the objectives are clear and appropriate for UK ODA;

- whether there are management processes in place that are appropriate to the nature of the activity, including systems for reporting on results and improving over time; and

- whether there are adequate systems for identifying and reporting accurately on ODA.

1.9 This is not a full ICAI review. We have not visited the activities in the field or conducted our own assessment of their effectiveness and value for money. For each item, the depth of our investigation has been proportional to the sums involved. Given the limited remit of this investigation, we have not scored the ODA activities against our standard review framework.

| Category and spending department | £ million |

|---|---|

| Programmable ODA | 52.3 |

| ■ Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) – Medical Research Council | 48.5 |

| ■ Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) – Darwin Initiative | 3.1 |

| ■ Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) – International Inspiration | 0.7 |

| Other departmental activities | 35.3 |

| ■ Home Office – Refugee support costs | 32.3 |

| ■ Ministry of Defence – Miscellaneous | 3.0 |

| Debt relief | 30.4 |

| Multilateral contributions | 22.0 |

| ■ Home Office – International Organization for Migration (IOM) | 0.8 |

| ■ Department of Health – World Health Organization (WHO) | 11.7 |

| ■ Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) – International Labour Organization (ILO) | 9.5 |

| Total | 140.0 |

Source: Figures provided by the spending departments.

1.10 In parallel to our investigation, the National Audit Office conducted a review of how DFID managed the challenge of meeting the UK’s ODA target.5 The UK Statistics Authority, which oversees the preparation of UK national statistics publications, has a forthcoming routine quality review of DFID’s Statistics on International Development. As there are some areas of potential overlap between our investigation and these two processes, we have consulted with both agencies and agreed both to minimise duplication of work and to share findings.

2 Findings

Introduction

2.1 The findings from this investigation are organised into three sections. The first contains our mapping of how non-DFID ODA has changed in recent years and our findings in respect of whether the scaling up of UK aid has led to inappropriate ODA activities by other departments.

2.2 The second section looks at each of the four categories of ODA listed in Figure 1 on page 3. It discusses whether the objectives are suitable for UK aid, whether sound management arrangements are in place and, where appropriate, whether the systems for identifying and reporting on ODA expenditure are reliable. The third section looks briefly at the role of DFID in respect of ODA spending by other departments.

Mapping of non-DFID ODA

2.3 As shown in Figure 2, UK ODA has nearly doubled over the past five years, from £6.4 billion in 2008 to £11.5 billion in 2013. Non-DFID ODA has consistently been in the range of 10-13% of the total and this proportion has not been affected by scaling up.

Source: Statistics on International Development, 2008-14.

| Department or item | 2013 ODA £ million |

|---|---|

| Departmental ODA | |

| Department of Energy and Climate Change | 412 |

| Foreign & Commonwealth Office | 295 |

| Department for Business, Innovation and Skills* | 49 |

| Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs* | 40 |

| Home Office* | 33 |

| Export Credits Guarantee Department* | 30 |

| Department of Health* | 12 |

| Scottish Government | 11 |

| Department for Work and Pensions* | 10 |

| Ministry of Defence* | 3 |

| Welsh Government | 1 |

| Department for Culture, Media and Sports* | 1 |

| Other sources of UK ODA | |

| Conflict Pool (non-DFID) | 184 |

| EC Attribution (non-DFID) | 124 |

| CDC Capital Partners | 100 |

| Gift Aid | 91 |

| Colonial Pensions | 2 |

| Total | 1,399 Ɨ |

* Falls within the scope of this investigation. In respect of Defra, our scope includes its contribution to the Darwin Initiative but not its contribution to the ICF. Source: Statistics on International Development 2014, DFID, October 2014.

Ɨ Differences due to rounding.

2.4 As shown in Figure 3 above, non-DFID ODA reached £1.4 billion in 2013, which was an increase of £226 million over 2012. Most of the increase (£166 million) was accounted for by a planned expansion of the International Climate Fund, with the Conflict Pool and the UK’s attributed share of European Union aid also expanding. There was relatively little increase in expenditure by the departments covered in this investigation.

The international ODA definition is:

‘those flows to countries and territories on the DAC List of ODA Recipients and to multilateral institutions which are:

i. provided by official agencies, including state and local governments, or by their executive agencies; and

ii. each transaction of which:

a) is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective; and

b) is concessional in character and conveys a grant element of at least 25 per cent (calculated at a rate of discount of 10 per cent).’6

Of 12 UK Overseas Territories, 4 are ODA-eligible and 3 currently receive regular UK aid: Montserrat; Pitcairn and St Helena and Tristan de Cunha (excluding Ascension Island).

Certain activities are excluded from the ODA definition, including military aid, the use of donor armed forces to restore order and counter-terrorism activities. Donors may, however, report the marginal costs of using their own military to deliver aid.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) is in the process of modernising the ODA definition. One of the issues is an outdated definition of concessionality, which, in an era of low interest rates, leaves room for some donors to report loans provided at market rates as ODA (the UK does not do this). In December 2014, agreement was reached on updating the concessionality criterion.7 Only loans with a grant element of at least 45% will be reportable as ODA. Furthermore, only a grant-equivalent figure, rather than the entire loan, will count towards ODA. This way, the more concessional the loan, the greater its contribution to ODA, which creates positive incentives. When assessing the level of concessionality, different discount rates will be used for low income, lower-middle income and upper-middle income countries, so as to create incentives for more generous lending to poorer countries. The new definitions are expected to apply from 2016.

Debate continues within the OECD-DAC on modernising other aspects of the ODA definition, including the recognition of new financial instruments, such as guarantees, designed to leverage private finance for development.

2.5 We note that a proportion of the expenditure recorded as non-DFID is, in fact, transferred across from DFID’s budget. DFID is a contributor to the three ODA programmes in our sample (listed in Figure 1 on page 3 under ‘Programmable ODA’) and reimburses the Export Credits Guarantee Department (ECGD) for part of the costs of UK debt relief.

Stakeholder concerns about increased non-DFID ODA

2.6 During the period when UK ODA was being rapidly scaled up towards the 0.7% target, there was an assumption in some quarters that pressure to spend more ODA would lead to an increase in the share of non-DFID ODA.8 This was coupled with a concern that other ODA-spending departments, which are not bound by the 2002 International Development Act,9 would be less pro-poor in orientation, resulting in a deterioration in the focus or quality of the UK aid programme.

2.7 In March 2010, the International Development Committee noted:

‘we think that there is a very real danger that, as aid levels increase over the next few years to meet the already agreed 0.7% target, more ODA will be spent through other government departments which are not subject to the 2002 Act. Such expenditure may not therefore have poverty reduction as its primary objective. We are concerned that this would have an impact on the very high reputation of the UK as a donor.’10

2.8 The 2002 Act states that DFID’s Secretary of State may only provide development assistance if she or he ‘is satisfied that the provision of the assistance is likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty.’11

2.9 Other departments, if they wish to report their expenditure as ODA, need only satisfy the international ODA definition, which is set by the OECD-DAC – the body that collects international aid statistics. The internationally-agreed definition of ODA is given in Figure 4. At its heart is a ‘primary purpose test’: ODA must have ‘the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective’.12

2.10 The difference between these two definitions is a question for debate. It is widely assumed that the international ODA definition is broader. It might include, for example, assistance that is directed purely at economic growth but is not likely to contribute to poverty reduction. On the other hand, while the ODA definition expressly excludes military expenditure, the UK Act is silent on the point.

2.11 In this investigation, we have not found any evidence that the scaling up of UK aid has led to a loss of pro-poor orientation. First, Figure 2 on page 4 shows that the proportion of non-DFID ODA has not increased. Second, our more detailed examination of non-DFID ODA expenditure (set out in the following section) found that, with very minor exceptions, the objectives satisfied both the international ODA definition and the International Development Act.

2.12 There are a few items that are not obviously contributions to international development. For example, the Home Office reports part of the costs of supporting refugees and asylum-seekers in the UK as ODA (see paragraphs 2.46-49 on pages 11-12). This is, however, permitted under international rules and is standard practice among donor countries. It also represents just a fraction of one per cent of UK ODA.

2.13 While we have not found any distortion in the UK aid profile as a result of the scaling up of UK ODA, the issue remains a live one. Now that the UK has achieved the 0.7% target, the aid budget is no longer expanding as rapidly. It is expected to increase only in line with growth in GNI, so as to remain on target.13 In the future, therefore, any major increases in other departments’ ODA may be offset by reductions in DFID’s budget.

The UK’s ODA return includes a number of items that are not attributed to the budgets of any particular department. As these items do not raise any particular concerns of principle as to ODA eligibility or aid management, we have not investigated them in detail. To assist with transparency, however, we include a brief explanation of each item here.

Conflict Pool (non-DFID): Direct contributions to the Conflict Pool from HM Treasury.

EC Attribution (non-DFID): The UK’s share of European Union ODA-eligible expenditure from funds that are not primarily for international development (namely, ODA spent by agencies other than the Directorate-General for Development Cooperation).

CDC Capital Partners: CDC is a development finance institution owned by DFID that invests in firms in developing countries. While CDC’s loan finance is not classed as ODA, its net equity flow (investments less sale of shares) is ODA-eligible. CDC is self-funding and has not received any new capital from the UK Government since 1995. In 2013, it invested £416 million and made a total profit after tax of £117 million.14

Gift Aid: The Gift Aid scheme enables charities to recover from HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) the tax paid on donations at the basic rate of 20%. Where these funds are spent on overseas development, they constitute UK ODA. To calculate the amount, every third year DFID sends a questionnaire to a sample of charities active in international development, asking them to identify the proportion of their annual budget spent on ODA-eligible activities. This proportion is then applied to the total amount of Gift Aid paid by HMRC to charities active in international development, to produce an estimate of ODA-eligible expenditure.15

Colonial Pensions: DFID’s Overseas Pensions Department pays pensions to former members of the UK Overseas Civil Service who were employed directly by former colonies following their independence, including India and Sudan. In 1970, the UK Government agreed to take over responsibility for these pensions. The total pension payment in 2012-13 was £92 million.16 Of this, around £2 million went to individuals in developing countries, making it ODA-eligible.

Programmable ODA

2.14 Programmable ODA refers to aid programmes or projects with discrete objectives and management arrangements. There are three in our sample: medical research grants; a biodiversity grant-making fund; and an Olympic legacy programme promoting sport and physical education.

The Medical Research Council (BIS)

Objectives

2.15 The Medical Research Council (MRC) is one of seven UK Research Councils funded through BIS. It funds UK research institutions or individual researchers working on public health issues, including global health. Where the research is primarily addressed to health challenges in the developing world, such as tropical diseases or HIV-AIDS, it can be reported as ODA.17 In 2013-14, MRC had an annual budget of £845 million and an ODA target of £31 million (ODA targets are set by HM Treasury for each multi-annual Comprehensive Spending Review period).

2.16 The MRC and DFID have a ‘Concordat’ to support UK-led biomedical and public health research to tackle health issues for poor people in developing countries.18 Under this 2013 agreement, DFID commits to providing £45 million over five years for activities of mutual interest. These include research into public health systems, treatment and prevention research (including clinical trials) for HIV-AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and other tropical diseases and capacity development for research institutions in developing countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.

2.17 In addition to its individual research grants, MRC funds two long-term research units based in Africa. Its unit in The Gambia is the UK’s largest investment in medical research in a developing country and focusses on tropical infectious diseases. It undertakes laboratory research, clinical studies and field-oriented science, together with research into clinical and public health practices. The other unit is based in Uganda and focusses on HIV-AIDS and related infections. Its research is intended to support the response to the HIV-AIDS epidemic, both in Uganda and across Africa. Together, these two units account for almost 30% of MRC’s ODA spending.

| Department | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFID | 12.0 | 13.0 | 6.6 |

| BIS | 36.0 | 35.0 | 41.9 |

| Total | 48.0 | 48.0 | 48.5 |

Source: Figures provided to ICAI by MRC and DFID

The ARROW clinical trial in Zimbabwe and Uganda19 explored treatment options for children with HIV. Currently, the treatment regime requires laboratory tests every 12 weeks, to assess whether the anti-HIV drugs are working. These tests are both expensive and difficult to provide in developing countries. This randomised trial established that children on HIV treatment could be safely monitored through clinical examination, without routine laboratory tests. In doing so, it helped to drive down the costs of HIV treatment, ensuring that more children in poor countries have access to treatment.

The FEAST clinical trial20 tested the appropriate use of fluids to resuscitate children suffering from shock as a result of malaria and other severe infections. The trial has informed important advances in treatment methods, potentially preventing thousands of deaths each year.

Management

2.18 Applications for MRC research funds are decided by one of a series of research boards or committees, each focussing on different areas of medical science or on particular strategic initiatives. Most ODA-eligible grants go through the Infections and Immunity Board or to one of a number of dedicated strategic schemes on global health issues. Each application is reviewed by independent scientists, in accordance with the Haldane principle.21 The principal award criteria are significance, scientific potential and value for money.

2.19 MRC’s grant-making processes are, for the most part, shared across the UK Research Councils and as such are subject to various independent review22 and audit23 processes. The grant-making system is elaborate, with detailed rules and guidance available for applicants. MRC also has detailed financial governance and anti-fraud requirements for supporting institutions in developing countries. The two units in The Gambia and Uganda are directly administered by MRC, to reduce fiduciary risk.

2.20 Some of MRC’s strategic initiatives, such as those supporting Joint Global Health Trials and African Research Leaders, are entirely ODA-eligible. In most cases, however, research applications are decided purely on scientific merit and their ODA eligibility is determined after the event. As a result, MRC has no real system for forecasting its ODA commitments each year. In 2013, it reported £48.5 million in ODA, (including DFID’s contribution of £6.6 million), well exceeding its target of £31 million.

2.21 We checked a sample of MRC-funded projects and had no concerns as to their ODA eligibility. In some cases, however, scientific expertise would be required to verify that the research primarily benefits developing countries and meets the ODA definition. DFID informs us that it checks the ODA eligibility of MRC projects on a sample basis, where necessary drawing on medical expertise within its own staff.

2.22 The outputs, outcomes and impacts of MRC-funded research are collected through an online monitoring system called ‘Researchfish’.24 Developed by MRC itself for tracking results, including publications, further funding awards, partnerships, policy influence, patents, medical products and external recognition, this sophisticated system is now used by a range of UK medical research funding bodies.

2.23 There are inherent challenges in demonstrating impact from medical research, owing to the often long time lag between scientific research, the development of new drugs or treatment methods and impacts on public health. In view of this time lag, grantees are asked to continue reporting their results for five years after the completion of their research. This is a good practice that we would like to see used more widely in aid programmes.

2.24 Overall, we are satisfied that MRC has robust management processes and results management systems in place.

The Darwin Initiative (Defra/DFID)

Objectives

2.25 The Darwin Initiative is a grant-making scheme that helps to protect biodiversity and the natural environment through projects in developing countries and UK Overseas Territories. It was first established at the time of the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro to help developing countries to implement the Convention on Biological Diversity.25 Since 1992, its scope has been extended to other related international conventions.26 It supports action against species loss, habitat degradation, invasive species, pollution and climate change mitigation and adaptation. Its projects include scientific research, capacity building and local action.

2.26 Since 1992, the Darwin Initiative has supported 903 projects in 158 countries, at a total cost of £105 million. In 2013, it disbursed £3.1 million in ODA-eligible grants, averaging £250,000 for a typical three-year project.

2.27 Protecting biodiversity is not in itself within the ODA definition. For most of its existence, the Darwin Initiative was funded solely by Defra and was not reported as ODA. In 2011, DFID became a co-funder of the portfolio. Its contributions are set out in Figure 8. DFID’s contribution goes towards ODA-eligible projects, while Defra’s contribution is spent in countries or territories or on projects that are not ODA eligible.

| Department | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFID | 2.4 | 2.4 | 3.1 |

Source: Figures provided to ICAI by Defra

2.28 Darwin projects funded from DFID’s contribution must include both poverty alleviation and biodiversity goals. Bringing these two objectives together reflects contemporary approaches to the protection of biodiversity. The underlying causes of habitat and species loss are often poverty and underdevelopment, which lead to over-exploitation of natural resources and poor environmental management. Communities need to be encouraged away from environmentally-destructive practices through the promotion of alternative livelihoods.

2.29 The Darwin Initiative portfolio contains some examples of projects that successfully marry the two objectives very well. For example, one 2012 grant of £290,000 supported a project that worked to incorporate the Batwa people into the management of Uganda’s national parks. The Batwa are a forest-dwelling people who were adversely affected by the creation of the parks. The loss of their traditional forest livelihoods and cultural practices brought them into frequent conflict with the authorities. The project is helping the Batwa to gain access to jobs in park management and to eco-tourism revenues, which in turn reduces poaching of gorillas and other vulnerable species.

2.30 Some of the earlier ODA-eligible projects were less successful at marrying the two objectives. According to Darwin Initiative guidance, both poverty reduction and biodiversity goals should be clearly identified and incorporated into project results frameworks. In one project whose documents we examined, the UK Royal Society for the Protection of Birds received a grant of £295,000 to help to save the critically-endangered spoon-billed sandpiper from extinction. The project aims to develop alternative livelihood activities for local communities living adjacent to nesting areas in Burma, so as to reduce trapping. These activities, however, appeared marginal to the main project goals and the project has been unable to measure its impact on local livelihoods.27

2.31 Since DFID joined the Darwin Initiative, DFID and Defra have worked with applicants to assist them with integrating poverty reduction objectives into their projects and to measure the development results. In 2014, they issued a Learning Note containing useful guidance on how to support and measure poverty reduction.28

Management

2.32 The administration of the Darwin Initiative grant scheme has been contracted out to a UK company, LTS International. Grants are awarded on a competitive basis, with applications assessed for scientific merit by an independent expert committee. The application process, eligibility rules, award criteria and expenditure are all transparent and widely publicised. Defra provides extensive guidance to applicants, as well as a helpdesk facility.

2.33 To qualify for a grant, applicants must demonstrate their financial capacity (based on audited accounts) and past implementation experience. They submit activity-based budgets, which are assessed against value-for-money criteria. If successful, they are required to submit activity and financial reports every six months and full reports with audited accounts on project completion. The final disbursement is withheld until audited accounts are received. Each year, the managing company performs audit ‘spot checks’ on 10%, by value, of live projects that have just completed their first year of implementation, to identify any issues or problems requiring intervention. The ODA eligibility of individual projects is assessed by LTS and subject to spot-checks by DFID.

2.34 Reporting of results by grantees is not particularly strong, although this is common with small grants of this nature. While each project reports against the indicators in its logframe, robust data are not always available. LTS carries out periodic evaluations by theme (for example, forest or island diversity) or geographical region to assess wider impact. It also disseminates lessons learned, in the form of periodic ‘Learning Notes’. While the monitoring system is appropriate to the size and nature of the grants, some of the grantees are clearly unused to measuring results in a systematic way and may need more support in this area.

2.35 Nonetheless, apart from needing more attention on results measurement, we are satisfied that the Darwin Initiative has suitable management arrangements in place for its portfolio.

International Inspiration Programme (DCMS/DFID)

Objectives

2.36 The International Inspiration Programme was a legacy programme from the 2012 London Olympic and Paralympic Games. It ran from April 2007 until June 2014. As part of its bid to host the Olympic Games, the UK committed to ‘enrich the lives of 12 million children and young people of all abilities in 20 countries around the world through high quality and inclusive sport, physical activity and play’.29 This was the first time that a host country had made a legacy commitment that was global in nature.

2.37 The programme worked to support sport and physical education (PE) at three levels:

- legislative and policy change;

- training and capacity building, such as developing training curricula for PE teachers and pairing schools in developing countries with UK schools; and

- creating opportunities for young people to participate in sport, through youth clubs, sports centres, enhanced PE and extra-curricular programmes in schools.

2.38 While the promotion of PE may not be an obvious priority for the UK aid programme, it rests upon a body of theory and empirical literature about the contribution of sport to educational attainment and life skills. The programme operated in 20 countries, including middle-income countries such as Turkey, Malaysia and Brazil. DFID funds, however, were used in only eight countries,30 while DCMS ODA funds were limited to Egypt and Bangladesh. Both the objectives and the partner countries fall within the international ODA definition.

| Department | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFID | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1 |

| DCMS | 1.4 | 0.1 | - |

| Total | 4.1 | 2.0 | 1 |

Source: Figures provided to ICAI by DCMS.

2.39 The International Inspiration Programme was jointly funded by DCMS and DFID, alongside contributions from the delivery partners (UK Sport, British Council and UNICEF) and private donors, for a total budget of £40 million. Figure 9 shows the funding shares over the final three years of ODA funding. While public funding has now stopped, the initiative continues as a charity (International Inspiration) with funding from other sources.

Management

2.40 In 2010, a charitable foundation was established to govern the International Inspiration Programme and receive both public and private funding. The management of the programme was provided by UK Sport, the body that channels public funds into elite sport in the UK.31 Its overseas activities were delivered by UNICEF and the British Council, in partnership with a range of local organisations, including ministries of education, sports and youth, National Olympic and Paralympic Committees, sports federations, teacher training institutions, schools and community-based organisations.

2.41 The programme’s governance structure and delivery arrangements were complex, involving a range of partners with different interests and approaches. It appears to have taken some time to settle in as a coherent programme. In 2009, a common results framework was introduced to improve integration across its components, with Key Performance Indicators for each delivery partner.

2.42 In each country where it operated, the programme began with a situational analysis, to identify needs and potential partners. It then worked with national counterparts to develop a Country Plan, setting out objectives and activities. Budgets were then assigned and activities were implemented by UNICEF and the British Council, each using their standard project and financial management systems. On one occasion, when one country (Ethiopia) was not performing as expected, funds were reallocated to International Inspiration Programme activities in two other DFID countries, Pakistan and Uganda.

2.43 Monitoring and evaluation support was provided by an independent contractor. There was a thorough final evaluation, which found that the programme’s results substantially exceeded its targets. Over 18.7 million children and young people were found to be regularly engaged in International Inspiration programme activities, against a target of 12 million. The results data do not reveal the socio-economic status of the beneficiaries. The programme did, however, make an effort to target poorer communities and marginalised groups, with a particular focus on children and young people living with disabilities. In addition, the programme trained over 250,000 teachers, coaches and community leaders, while influencing 55 laws and policies in 19 countries – in many cases leading to the first ever national strategy on sport and PE.32

2.44 Overall, we are satisfied that the International Inspiration Programme had management arrangements that were suitable for the activities in question and that it demonstrated the capacity to monitor its results and improve over time. International Inspiration continues to operate as a private charity, which contributes to the sustainability of results. We are informed that the success of the International Inspiration Programme has contributed to increased interest in the role of sport in developing countries, with the British Council, amongst others, developing new activities in this area.

Departmental activities reported as ODA

2.45 We move now to the second type of non-DFID ODA, which consists of existing departmental activities that are reported as ODA. Because these are not aid programmes or projects, they do not give rise to the management questions considered in the previous section. We look instead at whether the objectives are ODA-eligible.

Refugee support costs (Home Office)

2.46 The Home Office reports as ODA the costs of supporting refugees and asylum-seekers during their first 12 months in the UK while their asylum claims are being processed. Asylum seekers who are destitute or likely to become so are entitled to subsistence payments, accommodation and advisory services, amounting to £32.3 million in 2013-14. Subsistence payments are calculated per person according to a formula33 and paid weekly via the Post Office. Accommodation is provided free of charge to eligible asylum seekers through private firms contracted by the Home Office. An independent charitable organisation receives Home Office funding to provide orientation, advisory and referral services.

| Department | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | 2013-14 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home Office | 19.5 | 28.4 | 32.3 |

Source: Data provided to ICAI by the Home Office.

2.47 Historically, support for refugees was counted as aid only where the refugees were located in developing countries. In 1988, by decision of the OECD-DAC member countries, it was broadened to include first-year support costs for refugees in donor countries. The rationale was that the ODA definition should not penalise donor countries willing to accept refugees onto their own territory. Some observers have questioned the link between refugee support costs spent within a donor country and the ‘economic development and welfare of developing countries’.34 The link is, nonetheless, widely accepted by donor countries; in 2013, nearly US$4.5 billion in ODA was reported globally under this category.35

2.48 The UK historically declined to claim refugee support costs as ODA. According to DFID, it began to do so only in 2010 after the UK Statistics Authority pointed out that this made UK ODA statistics inconsistent with international practice.36

2.49 We are aware that there are controversies over the level and quality of support that the UK currently offers to asylum seekers. In April 2014, following a legal challenge brought by the charity Refugee Action, the High Court ruled that the level of support offered to refugees (currently £36.62 per week for a single adult) was inadequate and should be reviewed.37 The Home Office’s recent consolidation of the supply of refugee accommodation into three large contracts has also come in for criticism from the Public Accounts Committee, which noted that ‘the standard of accommodation provided was often unacceptably poor’.38 The adequacy of the support is not, however, for us to judge.

MOD ODA activities

2.50 The MOD reported just over £3 million in ODA in 2013. Its ODA portfolio consisted of a number of different activities which, after the event, were assessed as meeting the ODA definition (see Figure 11 on page 13).

2.51 All of the categories of expenditure reported by the MOD in 2013 are in line with the International ODA definition. Training of civilian police is a common form of development assistance. Courses on security sector governance qualify as ODA to the extent that they are provided to civilians (for example, MOD officials or civilian police), rather than military personnel. (Training of military personnel never qualifies as ODA, even if the training is in a non-military area such as human rights.) Although we were not able to see supporting evidence, MOD informs us that it keeps records of the exact proportion of civilian participants at each course, enabling it to identify accurately the ODA-eligible share of the costs.

2.52 The MOD currently has an ODA target of £5 million each year. In 2012, it had no system for recording its actual ODA expenditure and reported an estimate of £5 million. It argued that the small sums of money involved did not warrant the development of a system for tracking individual expenditure items. In 2013, on DFID’s encouragement, the Defence Resources Department sent out a request to the MOD’s top-level budget holders to report actual ODA expenditures, which were compiled and submitted to DFID. The result left MOD £2 million short of its ODA target. We are not entirely satisfied that the current MOD system is sufficient to identify all its ODA expenditure, although any items missed are unlikely to be material to the total. MOD informs us that it is now introducing a system for forecasting and tracking ODA more accurately. It is also producing guidance for its spending departments on ODA reporting rules.

| Activity | £ '000s |

|---|---|

| MOD Police Deployment to Afghanistan Use of MOD civilian police to train Afghani police | 994 |

| MOD Police Deployment to Kosovo Witness protection services to the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX) | 137 |

| UK-based and overseas courses on security sector governance A share of the cost of each course, according to the level of civilian participation | 1,811 |

| Disaster relief training for the Royal Navy | 24 |

| Attachment of Spanish speaking officer to Peacekeeping Centre in Santiago, Chile for eight months | 37 |

| Assistance with school painting (four days) in Kenya | 7 |

| Total Ɨ | 3,009 |

* Data provided to ICAI by MOD.

Ɨ Differences due to rounding.

Debt relief (ECGD/DFID)

2.53 The Export Credits Guarantee Department (ECGD)39 is the UK’s export credit agency. It helps UK exporters by providing insurance to them and guarantees to banks to share the risks involved in providing export finance. It also makes loans to overseas buyers of goods and services from the UK. If an overseas buyer or borrower defaults on a debt that has been guaranteed and ECGD pays out on an insurance claim, it becomes the owner of the debt.

2.54 Some of this debt is owed by developing country governments and may be eligible for debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative. HIPC was launched in 1996 by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, with the aim of ensuring that no developing country faces an unsustainable debt burden. It is supported by the UK and other OECD member countries through the Paris Club.40 Debtor countries that meet the eligibility requirements, including agreeing IMF- and World Bank-supported reform programmes and developing a national poverty reduction strategy, are given interim relief from interest payments. In due course, after further progress on reforms, they receive a debt write-off.41 The UK also provides debt relief to developing countries outside the HIPC process, including recently to Burma/Myanmar.

| Department | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECGD ODA | 91 | 19.7 | 30.4 |

| Beneficiary countries | Democratic Republic of Congo A | Guinea,A Côte d'Ivoire,A the Seychelles B | Burma/Myanmar,B Guinea A |

A = HIPC; B = non-HIPC. Source: Figures provided to ICAI by ECGD.

2.55 Developing country debt that is written off counts as UK ODA, with the cost shared between ECGD and DFID. Where the Paris Club has agreed to write off less than the full debt under HIPC, it is UK Government policy to write off the whole amount. The difference between the debt relief offered by the Paris Club and the total debt is then transferred to ECDG by DFID.

2.56 The HIPC process is now drawing to a close. With debt relief already provided to 36 countries, only Sudan, Somalia and, possibly, Zimbabwe may still be eligible. There may, however, be additional ODA-eligible debt relief in the future as a result of further Paris Club agreements.

2.57 We note that relief on debt from the purchase of weapons does not qualify as ODA. In 2012, in response to queries from stakeholders, the ECGD produced a document that analysed its sovereign debt by country and trade sector. This document was placed in the House of Commons library.42 It enables the ECGD to exclude any ineligible debt relief from its ODA return.

2.58 We also note that the UK Government does not sell public debt to speculators or ‘vulture funds’, which have been a cause of considerable financial distress in countries such as Argentina and the Democratic Republic of Congo.43 In 2010, the UK Parliament passed a private members bill preventing vulture funds from making unfair claims in UK courts against 40 HIPC-eligible countries.44

2.59 We conclude that UK debt relief raises no concerns as to either ODA eligibility or fund management.

Multilateral contributions

2.60 The final category of ODA expenditure consists of compulsory membership dues for international organisations. Most of the UK’s ODA contributions to international organisations come from DFID’s budget. In three cases, however, where the UK’s membership of the organisations serves both UK domestic interests and international development goals, the contribution comes from the budgets of other departments, either in full or in part (see Figure 13). The responsible department also represents the UK on the governing body of each organisation – although in the case of the World Health Organization, both the Department of Health (DOH) and DFID participate in the annual meetings in Geneva.

2.61 The governing body of each organisation decides on the overall level of core contributions from member states. The contribution to be paid by each member is then calculated through a formula based on GNI. The amounts to be paid are denominated in foreign currencies, which can lead to some volatility in the annual payment. For each organisation, the proportion of the contribution to be reported as ODA is agreed internationally (76% for WHO, 60% for ILO and 100% for IOM).45

| Department | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| World Health Organization – DOH | 14.8 | 14.8 | 11.7 |

| International Organization for Migration – Home Office | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

| International Labour Organization – DWP | 9.9 | 9.8 | 9.5 |

| Total | 25.6 | 25.5 | 22 |

Source: Figures provided to ICAI by DFID

2.62 Multilateral contributions raise no particular issues as to ODA eligibility, management or reporting.

DFID’s role in ODA spent by other departments

2.63 DFID has no formal mandate to co-ordinate or control the quality of ODA spent by other departments. Its responsibility is limited to ensuring ODA eligibility and compiling the UK’s annual ODA statistics. Beyond accurate reporting and achieving the 0.7% target, there are no UK Government-wide rules or processes governing the spending of ODA and no common oversight mechanism, other than ICAI itself. In that sense, ODA is merely a statistical category.

2.64 In practice, this investigation has shown that DFID does play a larger role. DFID is a contributor to the three examples of programmable ODA assessed here (the Medical Research Council, the Darwin Initiative and the International Inspiration Programme) – and, indeed, also the International Climate Fund and the Conflict Pool, which we have reviewed elsewhere. As a contributor, it must assure itself that the objectives satisfy the International Development Act’s focus on poverty reduction and that appropriate programme management arrangements are in place. We noted some examples of DFID providing advice and support to other ODA-spending departments on their aid practices.

2.65 DFID is also closely involved in the process of granting debt relief. It does not, however, play any role in respect of the MOD’s ODA activities or the Home Office’s refugee support costs, beyond ensuring their eligibility for ODA.

2.66 Each department submits a provisional ODA estimate, monthly updates on ODA expenditure and a final ODA return to DFID. DFID compiles the data into two annual National Statistics publications: Provisional UK ODA as a proportion of Gross National Income (GNI), released in March, and Statistics on International Development, published in October.46 As designated National Statistics, these publications must meet the standards set out in the Code of Practice for Official Statistics,47 covering areas such as quality assurance and engagement with end users. The publications are reviewed every three years by the UK Statistics Authority.

2.67 DFID’s quality assurance of departmental ODA returns involves several processes. There is ongoing dialogue with each department on which types of expenditure meet the ODA definition. Doubtful cases can be referred to the DFID ODA team, the DFID Chief Statistician and, ultimately, to the OECD-DAC Secretariat. DFID also engages in dialogue with the departments about the adequacy of their systems for identifying ODA expenditure.

2.68 DFID then checks each departmental ODA return, using a series of internal logic tests that identify inconsistencies in the data, taking into account previous returns and forecasts. Any discrepancies are discussed with the reporting department. DFID also checks the ODA eligibility of individual expenditure items on a sample basis, proportionate to the amount of expenditure and the level of risk. For the MRC, DFID informs us that a sample of the grants is checked by its own health policy team to verify that the research is indeed primarily for the benefit of developing countries.

2.69 Beyond checking compliance with the ODA definition, DFID does not attempt to verify the accuracy of the expenditure data. For example, MOD’s reported ODA expenditure on training courses involves calculations as to the proportion of civilians attending each course. In such cases, DFID may wish to ask MOD to submit the details of its calculations, with supporting documentation.

2.70 It appears likely that some departments are not yet reporting all of their ODA. Several departments with activities abroad, including the Department of Health, the Home Office and the Ministry of Justice, are yet to introduce a system for identifying ODA expenditure. The MOD has made progress on establishing such a system. We hope that DFID will continue to work with other departments to raise their awareness of the need to report ODA and improve their systems for doing so. It is unlikely, however, that the omissions are significant in statistical terms.

2.71 Overall, we are satisfied that DFID’s checking of the UK ODA return against the international ODA definition is appropriate, risk-based and proportionate to the levels of expenditure involved. We leave it to the UK Statistics Authority to comment on other aspects of DFID’s National Statistics publications.

2.72 In our view, DFID takes an appropriately conservative approach to ODA reporting. It avoids including borderline items that might be harmful to the UK’s reputation as a donor, while following settled international practice. For example, unlike some donors, it does not report the costs of voluntary repatriation of asylum-seekers, recognising that the difference between a voluntary and a forced repatriation may be a fine one. It does, however, follow standard practice in claiming first-year refugee support costs. While we recognise the concern of other commentators as to whether this is really a contribution to international development, we see little value in the UK refusing to follow established reporting practices, which would merely result in inconsistent statistics at the international level.

2.73 We find that there is insufficient information available on the nature and objectives of non-DFID aid to meet the needs of transparency. Some of the individual departments are fully transparent in their ODA spending, provided that the public knows where to look. For those looking for a summary of non-DFID ODA as a whole, statistics are published in Statistics on International Development only at the level of departmental totals. Although project-level data are available on the OECD-DAC website, the descriptions of each project are very limited. While DFID helpfully includes an explanation of some of the activities covered in an annex to its Statistics on International Development publication,48 there is no clear explanation for the public of the full range of activities that the UK reports as ODA. Our report is intended as a contribution to improving transparency. In Section 3, we also make a recommendation as to how DFID could achieve this.

3 Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

3.1 This section summarises our main conclusions from this investigation. It also provides a recommendation for how to strengthen the reporting of non-DFID ODA.

3.2 Over the past five years, as UK ODA has nearly doubled, the proportion of DFID and non-DFID ODA in the total has remained approximately the same. The bulk of the additional funds for scaling up the aid budget have, therefore, come from DFID. The increases in non-DFID ODA have come mainly from the International Climate Fund and the Conflict Pool. There has been little increase in ODA spent by the departments covered in this investigation. As a consequence, we have found no evidence that the scaling up of the UK aid budget has led to a loosening of UK ODA reporting practices or a loss of pro-poor orientation to the aid programme as a whole.

3.3 In an era of budgetary restrictions, however, other departments may still face incentives to increase their ODA. With UK aid no longer scaling up as rapidly as before, this could lead to corresponding decreases in DFID’s budget. We suggest, therefore, that this area be kept under review. Each year, we may examine any major new categories of non-DFID ODA and comment in our Annual Report on their appropriateness.

3.4 For the programmable aid examined here, we found that the objectives (medical research on health issues affecting developing countries; the promotion of biodiversity through the strengthening of local livelihoods; and the promotion of sport and physical education) were clear and appropriate. They are directly linked to the departments’ own mandates, as well as appropriate for the UK aid programme. As co-funder, DFID has played a role in ensuring that these programmes are poverty focussed and in improving their aid-management practices. We found that the management arrangements were appropriate for the activities in question, with sound grant-management processes and fiduciary controls. The Darwin Initiative faces challenges in measuring and reporting on its results. We suggest that DFID continue to work with Defra to strengthen its approach to results management.

3.5 ODA reported by the Home Office and MOD complies with the international definition. The MOD is still developing a system for capturing its ODA expenditure accurately. While any unreported items are unlikely to be material, we suggest that DFID continue to work with relevant departments to develop a more accurate system for recording their ODA.

3.6 We have no concerns as to the appropriateness of or management arrangements for debt relief or the multilateral contributions.

3.7 We found DFID’s quality assurance of ODA returns from other departments to be appropriate, risk-based and proportionate to the levels of expenditure involved. In borderline cases, DFID’s approach to ODA reporting remains appropriately conservative.

3.8 The International Development Committee asked us to consider whether there are appropriate accountability arrangements over non-DFID ODA. The question is an apt one. As ODA is just a statistical category, there is no overall accountability for UK ODA. Some of the programmes we examined here, such as the MRC and the International Inspiration Programme, had quite elaborate accountability mechanisms built into them. Departmental activities reported as ODA had no particular scrutiny process, other than those applying to the department’s budget as a whole. ODA expenditure is not separately identified in the accounts of the individual departments.

3.9 There is, therefore, no parliamentary oversight of UK ODA as a category. In particular, parliamentary oversight of expenditure under the new Conflict, Stability and Security Fund, which is the successor to the Conflict Pool, is shared between the Foreign Affairs Committee, the Defence Committee, the International Development Committee and potentially others, with no single committee having oversight of the instrument as a whole. In our 2012 report on the Conflict Pool, we expressed our concern at the lack of sufficient parliamentary oversight over this part of the aid programme.49 This concern remains.

3.10 A related point is transparency. It was clear from our consultations with stakeholders that the lack of published information on non-DFID ODA was contributing to widespread concern that inappropriate items might be classed as UK ODA. We have not found this to be the case. The lack of transparency is, nonetheless, a concern in its own right. We would like to see DFID’s Statistics on International Development include a more complete explanation of the main categories of ODA spent by other government departments, to enable the public – and the International Development Committee – to understand the expenditure data.

Recommendation

DFID should request ODA-spending departments to accompany their annual ODA returns to DFID with an information note describing, in simple terms, the main activities or types of activity claimed as ODA. DFID should include this information in an annex to its Statistics on International Development in order to enhance transparency.

Abbreviations

- BIS

- Department for Business, Innovation and Skills

- DCMS

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport

- Defra

- Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

- DECC

- Department of Energy and Climate Change

- DOH

- Department of Health

- DWP

- Department of Work and Pensions

- ECGD

- Export Credits Guarantee Department

- FCO

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office

- GNI

- Gross National Income

- HIPC

- Heavily Indebted Poor Countries

- HMRC

- Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs

- HIV-AIDS

- Human Immuno-deficiency Virus – Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- ICAI

- Independent Commission for Aid Impact

- ILO

- International Labour Organization

- IMF

- International Monetary Fund

- IOM

- International Organization for Migration

- MRC

- Medical Research Council

- MOD

- Ministry of Defence

- ODA

- Official development assistance

- OECD-DAC

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – Development Assistance Committee

- PE

- Physical Education

- UK

- United Kingdom

- UNICEF

- United Nations Children’s Fund

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Footnotes

- DFID Statistics in International Development are available at https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-international-development/about/statistics.

- Evaluation of the Inter-Departmental Conflict Pool, ICAI, July 2012, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Evaluation-of-the-Inter-Departmental-Conflict-Pool-ICAI-Report.pdf.

- FCO and British Council Aid Responses to the Arab Spring, ICAI, June 2013, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/FCO-and-British-Council-Aid-Responses-to-the-Arab-Spring-Report.pdf.

- The UK’s International Climate Fund, ICAI, December 2014, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/ICAI-Report-International-Climate-Fund.pdf.

- Managing the Official Development Assistance Target, National Audit Office, January 2015, page 7, http://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Managing-the-official-development-assistance-target.pdf.

- Is It ODA?, OECD-DAC Factsheet, November 2008, http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/34086975.pdf.

- DAC High Level Meeting Final Communiqué, Development Assistance Committee, 16 December 2014, http://www.oecd.org/dac/OECD%20DAC%20HLM%20Communique.pdf.

- See, for example, evidence presented to the International Development Committee in 2010. Draft International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Bill, Seventh Report of Session 2009-10, International Development Committee, 23 March 2010, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmintdev/404/404.pdf.

- See http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2002/1/pdfs/ukpga_20020001_en.pdf.

- Draft International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Bill, Seventh Report of Session 2009-10, International Development Committee, 23 March 2010, page 14, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmintdev/404/404.pdf.

- International Development Act 2002, Section 1(1).

- Is It ODA? OECD-DAC Factsheet, November 2008, http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/34086975.pdf.

- ‘The requirement to hit, but not significantly exceed, aid spending equal to 0.7% of gross national income every calendar year means the Department has to hit a fairly narrow target against a background of considerable uncertainty.’ Managing the Official Development Assistance Target, National Audit Office, January 2015, page 7, http://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Managing-the-official-development-assistance-target.pdf.

- See http://www.cdcgroup.com/Who-we-are/Key-Facts.

- Gift Aid Methodology Note, DFID, 7 October 2013, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/248648/gift-aid-methodology-note.pdf.

- Overseas Pensions Department Annual Report April 2011-March 2012, DFID, 2012, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/214045/overs-pens-dept-annl-rpt.pdf.

- The international ODA definition includes ‘financing by the official sector, whether in the donor country or elsewhere, of research into the problems of developing countries’. DAC Statistical Reporting Directives, Development Co-operation Directorate, DAC, November 2010, paragraph 51(iv), http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/38429349.pdf.

- Further details can be found at http://devtracker.dfid.gov.uk/projects/GB-1-203085/.

- For more details, see http://www.ctu.mrc.ac.uk/our_research/research_areas/hiv/studies/arrow/ and http://www.arrowtrial.org/ts_overview.asp.

- For more details, see http://www.ctu.mrc.ac.uk/our_research/research_areas/other_conditions/studies/feast/.

- The Haldane principle states that decisions on allocation of research funds should be made by scientists, rather than politicians. Putting Science and Engineering at the Heart of Government Policy, Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills Committee, Eighth Report of Session 2008-09, Volume I, 23 July 2009, paragraph 138ff, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200809/cmselect/cmdius/168/168i.pdf.

- Triennial Review of the Research Councils: Final Report, BIS, April 2014, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/303327/bis-14-746-triennial-review-of-the-research-councils.pdf.

- Described here: http://www.rcuk.ac.uk/about/aboutrcuk/aims/units/aasg/involved/auditprocess/.

- See https://www.researchfish.com.

- Convention on Biological Diversity, United Nations, 1992, https://www.cbd.int/doc/legal/cbd-en.pdf.

- The Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-Sharing, the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

- Darwin Initiative Annual Report Review, Project 19-012, June 2014.

- Learning Note: Poverty and the Darwin Initiative, Defra, http://www.darwininitiative.org.uk/assets/uploads/2014/05/DI-Learning-Note-poverty-and-biodiversity-2014-Final.pdf.

- See http://www.internationalinspiration.org/international-inspiration-programme.

- Ethiopia, Indonesia, Jordan, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, South Africa and Uganda.

- UK Sport invests around £100 million of public funds each year into high-performance sport under the supervision of DCMS. It also plays a role in promoting sport internationally, mainly in Southern Africa: http://www.uksport.gov.uk/pages/about-uk-sport/.

- Final Evaluation of the International Inspiration Programme, Ecorys UK, http://www.internationalinspiration.org/sites/default/files/attachments/Final%20IIP%20Evaluation%20Report%20130614.pdf.

- See https://www.gov.uk/asylum-support/what-youll-get.

- Hynes, William and Simon Scott, The Evolution of Official Development Assistance: Achievements, Criticisms and a Way Forward, OECD Development Co-operation Working Papers No. 12, 2013, http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/5k3v1dv3f024.pdf?expires=1423439773&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=30E52C020C64796F96580EF55E47100E.

- OECD-DAC International Development Statistics, at http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx.

- Statistics on International Development and the ODA:GNI Ratio: Department for International Development, UK Statistics Authority, Assessment Report 9, July 2009, paragraph 4.12, http://www.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/assessment/assessment/assessment-reports/assessment-report-9—statistics-on-international-development-and-the-oda-gni-ratio–27-july-2009.pdf.

- Bowcott, Owen, Asylum-seeker subsistence payments defeat for government in high court, The Guardian, 9 April 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/apr/09/asylum-seeker-subsistence-payments-defeat-government-theresa-may, accessed 8 November 2014.

- COMPASS: Provision of asylum accommodation, House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, Fifty-fourth Report of Session 2013-14, 24 April 2014, page 3, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmpubacc/1000/1000.pdf.

- Operating under the name UK Export Finance: see https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/uk-export-finance.

- The Paris Club is an informal group of official creditors whose role is to find co-ordinated and sustainable solutions to the payment difficulties experienced by debtor countries: see http://www.clubdeparis.org/en/.

- For more details, see https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/hipc.htm.

- Sovereign Debts: Explanatory Note, UK Export Finance, October 2012, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/190838/ukef-sovereign-debt-data.pdf.

- Eichengreen, Barry, Restructuring debt restructuring, The Guardian, 9 September 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/sep/09/restructuring-debt-restructuring-barry-eichengreen, accessed on 8 November 2014.

- Debt Relief (Developing Countries), Act 2010, Chapter 22, http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/22/pdfs/ukpga_20100022_en.pdf.

- DAC List of ODA-Eligible International Organisations: General Methodology, OECD-DAC, December 2011, http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/49194441.pdf. The ODA-eligible proportion for each organisation for 2013 is posted here: http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/documentupload/Annex%202%20for%202013.xls.

- The publications can be found here: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-international-development/about/statistics.

- Code of Practice for Official Statistics, UK Statistics Authority, January 2009, http://www.statisticsauthority.gov.uk/assessment/code-of-practice/code-of-practice-for-official-statistics.pdf.

- Statistics on International Development 2014, DFID, October 2014, Annex 3 – Data Sources, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/368613/Annexes-SID-2014.pdf.

- Evaluation of the Inter-Departmental Conflict Pool, ICAI, July 2012, page 18, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Evaluation-of-the-Inter-Departmental-Conflict-Pool-ICAI-Report1.pdf.