ICAI Annual Report 2018 to 2019

Foreward

The last 12 months have seen plenty of public and political debate about the uses and effectiveness of the UK’s aid programme. In this context, it is evident that independent scrutiny based on rigorous evidence gathering is more important than ever.

The UK is undoubtedly experiencing a period of political turbulence, with the challenges of leaving the European Union preoccupying government. The strains across Whitehall have not made it easier to fulfil ICAI’s remit to scrutinise the impact of all UK government official development assistance.

It has also been a year of transition for ICAI. Having learned lessons from the experience of moving from Phase 1 to Phase 2 of the commission, a good deal of planning has gone into ensuring that appointing new commissioners and retendering our external supplier contract has not disrupted ICAI’s work programme (we intend to publish around the same number of reviews in the first year of Phase 3 as in the last year of Phase 2). I would like to take this opportunity to welcome our incoming commissioners, Sir Hugh Bayley and Tarek Rouchdy, who will take up their posts on 1 July 2019. I very much look forward to working with them.

Although formally chief commissioner only from 1 January 2019, I began to get involved with ICAI’s work from autumn 2018, working with the team in selecting the first set of Phase 3 review topics and laying the groundwork for new approaches. This has included greater integration of the voices of those UK aid is meant to help, which will be a core commitment of ICAI over the next phase. We have also embarked on some innovations, with more shorter pieces of work to ensure timely publications – for example, to inform the debate around the Spending Review – and new products, such as the first country portfolio review of Ghana.

Although all this external and internal change has sometimes created practical challenges, ICAI’s regular work, supporting the International Development Select Committee, has continued unabated. We have published ten reports this year, covering a range of government departments and focusing on some of the major themes in international development.

In preparation for Phase 3 of the commission, ICAI has also carried out an innovative consultation exercise on topics and products, both online and through several stakeholder meetings. We are very grateful to all those who contributed – it has been extremely helpful to ensure that we are focused on the most salient areas and work in the most effective ways. It has also been encouraging to get very positive feedback on our work to date.

As we complete the last year of Phase 2, it is time to pay tribute to the outgoing commissioners. Alison Evans provided remarkable leadership in building ICAI’s credibility and effectiveness until she left at the end of 2018, and I now have to say farewell to Tina Fahm and Richard Gledhill, who have worked tirelessly over the last four years to ensure that ICAI’s work is rigorous and ultimately improves UK aid.

To get some idea of their collective achievement, I would encourage you to read the follow-up review for 2018-19, as well as our overarching review The current state of UK aid: A synthesis of ICAI findings from 2015 to 2019. The latter, in particular, provides both a fitting legacy for the Phase 2 commissioners and a valuable exploration of how well the aid programme is equipped to respond to the challenges ahead.

Tamsyn Barton

Tamsyn Barton

ICAI Chief Commissioner

Highlights of 2018-19

The focus of our reviews

ICAI’s annual programme of thematic reviews, agreed by the International Development Committee (IDC), provides Parliament and UK taxpayers with evidence on the performance, impact and value for money of the UK aid programme, ensuring the government is held to account. In 2018-19, the topics for our work programme were selected based on four criteria:

- volume of aid spent or projected to be spent on the issue

- relevance to the UK aid strategy and the Sustainable Development Goals, and related policy and programming developments

- level of risk associated with a particular geography or issue

- potential added value of an ICAI review.

ICAI published eight scored reviews between July 2018 and July 2019, the annual follow-up review and, for the first time, a review of The current state of UK aid, looking back at some of the key issues that arose in ICAI Phase 2 and forward to ICAI Phase 3. Of the scored reviews, four were rated green/amber and four amber/red.

Table 1: ICAI 2018-19 reviews and scores

| Review topic | Review type | Publication date | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Achieving value for money through procurement Part 2: DFID’s approach to value for money through tendering and contract management | Performance | September 2018 | Green/amber |

| DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments | Performance | October 2018 | Green/amber |

| DFID’s contribution to improving maternal health | Impact | October 2018 | Amber/red |

| The UK’s approach to funding the UN humanitarian system | Performance | December 2018 | Green/amber |

| International climate finance: UK aid for low-carbon development | Performance | February 2019 | Green/amber |

| CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states | Performance | March 2019 | Amber/red |

| DFID’s partnerships with civil society organisations | Performance | April 2019 | Amber/red |

| The Newton Fund | Performance | June 2019 | Amber/red |

| The current state of UK aid: A synthesis of ICAI findings from 2015 to 2019 | Synthesis | June 2019 | Not scored |

| 2017-18 follow-up | Follow-up | July 2019 | Not scored |

Key themes emerging from 2018-19 reviews

Several themes have emerged from the reviews completed during 2018-19:

Influencing other international systems and standards

Three of our reviews (on International Climate Finance, UN humanitarian systems, and infrastructure) looked at how the UK seeks to influence the broader international system.

For example, the UK has used the scale of its investment on low-carbon development to help shape the international architecture for climate finance and to influence how others spend their climate finance – more than half of the UK aid budget for climate finance is spent on mitigation, and a significant proportion of this is spent through multilateral climate funds.

The Department for International Development (DFID) is widely perceived as a strong global advocate for the rights of women and girls and has a strong international profile on family planning and safe abortion. It is the UN Population Fund’s largest donor and uses this influence to expand global access to family planning supplies. It has also coordinated effectively with other development partners to advance the family planning agenda – its relationship with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is particularly strong. At the 2012 and 2017 global summits on family planning, DFID was successful in securing new commitments of funding and action from other donors.

DFID invests in research on transport infrastructure to promote knowledge on cross-cutting issues. It has several very successful knowledge-based partnerships with the World Bank, aimed at developing the capacity building of national governments to make greater use of research findings.

Safeguarding

Unsurprisingly, after the intense focus on safeguarding by DFID, following the crisis in the international development sector in early 2018, we have looked carefully at safeguarding while undertaking our reviews. While our procurement review found that DFID’s procurement policies had been overhauled following the crisis, other reviews illustrated that there is still more to do in this important area. This will therefore remain an issue of focus for ICAI scrutiny.

The review on civil society organisations highlighted some of the issues a rigorous compliance-based approach can raise, especially for small organisations with limited capacity. Our infrastructure review noted how DFID relies on the safeguarding policies of its multilateral partners, but that implementation of these policies at country level can be very challenging. We found that DFID is not active enough in ensuring that the multilateral development banks and their national counterparts have adequate systems and capacities in place to implement safeguarding policies at country level.

The CDC review found that safeguarding issues (and other non-compliance with standards and policies) could be hidden from investors by investee companies and their management, and our review of UN humanitarian systems found that there is considerable work still to be done at both international and country level to identify and implement practical solutions.

Private finance mobilisation

Our reviews on infrastructure, International Climate Finance and CDC examined how aid investments by the UK can be used to mobilise private finance for development, to drive additional value for UK aid.

DFID is a relatively modest funder of infrastructure, focusing much of its portfolio on mobilising or leveraging other sources of infrastructure finance. While there is no shortage of multilateral finance available for infrastructure projects, the limiting factor is often a lack of investment-ready projects as low-income countries usually lack the technical capacity to carry out economic assessments, feasibility studies and detailed engineering designs, and are generally unwilling to borrow from the multilateral development banks to meet the substantial costs involved. DFID therefore contributes to project preparation facilities and multi-donor initiatives such as the Private Infrastructure Development Group (and previously contributed to the Regional Infrastructure Programme for Africa) to unlock or leverage additional finance and support project preparation. However, results have been uncertain, partly because of a lack of clear understanding and consistent measurement of what counts as ‘leverage’. At best, this prevents us from assessing the credibility of claimed results. At worst, it gives rise to the possibility that all the funders are claiming to have leveraged each other, which would not be meaningful. DFID is working with other donors through the OECD Development Assistance Committee to improve definitions in this area.

Our CDC review found that until very recently CDC has had no overarching strategy for encouraging the mobilisation of private finance. Its 2017-21 strategic framework includes mobilising private capital among its seven key goals, but only talks in general terms about how CDC will look for new ways to do this.

In contrast, we scored International Climate Finance (ICF) green-amber on promoting investment in low-carbon development. ICAI found a good range of achievements in the areas of capacity building, demonstration of the viability of projects and mobilising private investment. ICF uses key performance indicators to measure results such as finance mobilised. The cumulative result from 2011 to 2018 was the mobilisation of £3.3 billion in new public investments and a further £910 million in private finance.

Learning

Concerns around how effectively departments learn from their own and other departments’ experiences has been a recurring theme of ICAI’s work. Many of our 2018-19 reviews criticised the application of learning in the design and management of UK aid programmes. Capturing and sharing learning effectively is a big challenge for any organisation, and particularly for a matrix organisation like UK aid, operating across departments and geographies. But it is vitally important to ensuring the value for money and effectiveness of investment.

Our review of the Newton Fund found that it lacks a coherent system for monitoring or capturing development outcomes and therefore has very limited evidence on the results of its work so far, hampering efforts at cross-fund learning. Our CDC review also found weaknesses in monitoring and evaluation. CDC has stepped up efforts in this area, supported by DFID. However, CDC’s learning efforts are not yet sufficiently adapted to its ambition to deliver development impact at scale in low-income and fragile states. The review of civil society organisations found that DFID had not been sufficiently focused on filling knowledge gaps in the design of its partnerships and funding instruments and that its funding approach did not facilitate innovation. There was also insufficient evidence of sharing and uptake of learning and innovations. Our procurement review found that the lack of investment in a suitable procurement information system remains a constraint on DFID’s capacity to understand, exploit and learn from its management information.

The exception was ICF, which scored well on learning in recognition of the substantial investment in results measurement and knowledge generation, and the UK’s influencing of multilateral partners to strengthen results measurement.

Cross-government working

The continuing trend of increased aid spending by other government departments and cross-government funds underlines the central importance of effective coordination.

We saw further improvements in engagement between DFID and CDC, particularly at the centre, though there is more to do at the country level. And the follow-up review reported much strengthened coordination, in particular between DFID, the Department of Health and Social Care and Public Health England. But at a strategic level we remain concerned. As an increasing proportion of official development assistance (ODA) is spent outside of DFID, the issue of how to manage cross-government programmes effectively (using the skills and expertise found across government) becomes ever more salient.

Our review of the Newton Fund found that DFID plays a role within the governance of the Fund, with representatives on two Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) boards: Research and Innovation ODA and Portfolio and Operational Management. However, ICAI found little evidence of direct and active learning between BEIS and DFID on best practice in delivering ODA-funded research programmes, including how to measure value for money and guidance on getting research into policy and practice. We did, however, find evidence of some efforts by in-country teams to communicate with DFID on research activities in cases where there were shared country partners with the Newton Fund.

Our review of ICF flagged a risk that the divergent approaches being adopted by BEIS and DFID towards low-carbon development may lead to gaps in the portfolio. Since 2016, responsibility for managing climate finance spending targets and programmes has been devolved to the three spending departments (DFID, Defra and now BEIS), albeit still with the ‘UK International Climate Finance’ branding.

In our review of civil society organisations, ICAI found that DFID and the UK government more generally do not have clear and shared objectives for their work on the maintenance of civic space. Both DFID and the Foreign Office work on the issue – and lead on various aspects – but there is no agreement on ‘what good looks like’ in a field where anti-terrorism, security and human rights agendas all play a role. The review recommended DFID work with other government departments on a joint approach to addressing the decline of civic space at international level.

UK aid and the “national interest”

Funds created to pursue a combination of UK national interests and development goals now spend a significant proportion of UK ODA. During 2018-19 ICAI followed up on progress against its previous reviews of the Prosperity Fund, the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) and the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), and reviewed for the first time the Newton Fund.

The Newton Fund is one of several ‘dual purpose’ funds designed to promote both international development and UK national interests. The stated national interest objective is to promote UK ‘soft power’ by positioning the UK as a global leader in research and innovation and by building ties between UK institutions and their counterparts in emerging markets. We found that the Fund is poorly designed to deliver development goals, and that in reality its secondary objectives have been the main driver of its choice of partnerships, research themes and approach. ICAI also found that the Newton Fund has been used to help meet the government’s commitment to spending 2.4% of GDP on research and innovation by 2027.

The follow-up review on the GCRF, the CSSF and the Prosperity Fund has shown that the new funds and programmes have responded well to the concerns raised by ICAI and have made considerable progress in putting in place the necessary systems and processes to ensure value for money and compliance with ODA rules. However, challenges and risks remain, some of which are legacies of the lack of strategic direction and ODA management structures and processes when the funds were first launched.

The government has reaffirmed that UK aid spending will continue to support the UK’s national interests (in addition to combating extreme poverty and tackling global challenges). This theme is therefore likely to recur in ICAI’s reviews in future.

Leave no one behind

Finally, ‘leave no one behind’ has been a recurring theme in many ICAI reviews, including CDC, climate change financing, infrastructure and civil society organisations, as well as in The current state of UK aid: A synthesis of ICAI findings from 2015 to 2019, which clearly covers a longer time period.

The UK was a global champion of the ‘leave no one behind’ principle during the negotiation of the Sustainable Development Goals. It has pledged to “put the last first” by prioritising “the world’s most vulnerable and disadvantaged people; the poorest of the poor and those people who are most excluded and at risk of violence and discrimination”.

‘Leave no one behind’ has profound implications for how aid programmes are designed and delivered, and several of our reviews have explored how well DFID has risen to the challenge. Overall, DFID has made good progress on implementing the ‘leave no one behind’ commitment, while other aid-spending departments have not taken on this commitment, and the shift in the geographical focus of non-DFID aid towards upper-middle-income countries is a potential cause of concern.

CDC has developed some investment instruments to target the poor, but we found it could adopt a sharper focus on poverty reduction across its portfolio. In an effort to target the poorest in society, DFID appointed CDC to manage two new investment vehicles, the Impact Fund and the Impact Accelerator, in 2013 and 2015 respectively, but these remain small in scale compared with CDC’s Growth Portfolio, accounting for just 6% of CDC’s new commitments in 2017. Beyond the Impact Fund and Impact Accelerator, we found mixed levels of engagement in CDC in relation to the challenge of reaching the poorest.

Our infrastructure review found that DFID’s approach to poverty reduction and the inclusion of women and marginalised groups was inconsistent. In our sample, there were several investment and research programmes that directly targeted the poor and marginalised groups. These included a programme designed to reduce the isolation of remote communities in western Nepal and a research project exploring how to bring down the global toll of road accident deaths, which disproportionately affects the poor. The portfolio also showed a clear geographical focus on the poorest states and areas within states. However, for those programmes focused specifically on economic growth, we found that insufficient consideration is given to poverty reduction and the needs of women, people with disabilities and other marginalised groups.

The civil society organisations review found that DFID encourages organisations to embrace the ‘leave no one behind’ commitment. Before 2015, DFID projects did not systematically prioritise hard-to-reach groups, but the inclusion of equity in value for money metrics means that reaching this demographic has now become a key feature of value for money. As a result, we saw a trend where centrally funded projects worked more clearly and deliberately towards the ‘leave no one behind’ commitment at the end of the review period than at the beginning.

Functions and structure

This chapter sets out the current structure and functions of ICAI. It also reports on the performance of ICAI’s supplier (a specialist international development consultancy).

ICAI’s structure and functions

ICAI was established in May 2011 to scrutinise all UK ODA, irrespective of spending department. ICAI is an advisory non-departmental public body. ICAI is sponsored by DFID but delivers its programme of work independently and reports to the IDC.

To do this, ICAI:

- carries out a small number of well-prioritised, well-evidenced, credible thematic reviews on strategic issues faced by the UK government’s aid spending

- informs and supports Parliament in its role of holding the UK government to account

- ensures its work is made available to the public.

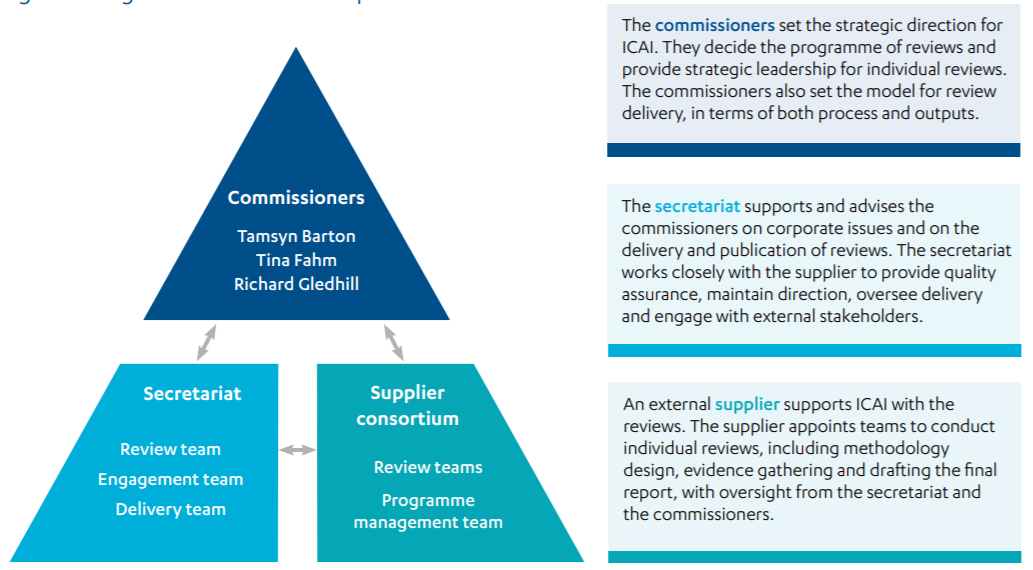

ICAI is led by a board of independent commissioners, who are supported by a secretariat and an external supplier. These three pillars – commissioners, secretariat and supplier – work closely together to deliver reviews. The high-level roles and responsibilities of the three pillars are detailed in the diagram below.

Figure 1: High-level roles and responsibilities

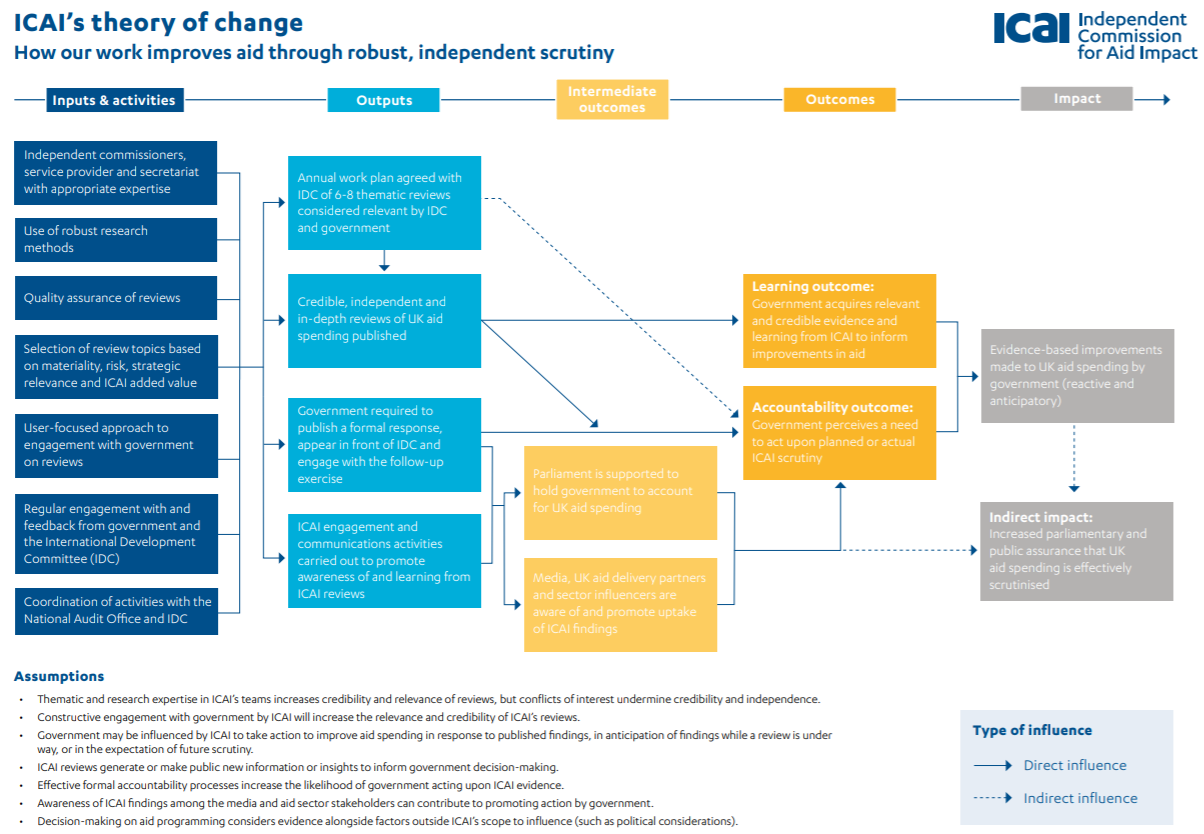

ICAI’s theory of change

ICAI has developed a theory of change following the 2017 Tailored Review (see below), illustrating how our work is expected to deliver improvements in the impact and value for money of UK aid spending. In addition, the theory of change is expected to assist our continuous improvement. The diagram below summarises the theory of change. This will be reviewed during Phase 3.

The ICAI team

The commissioner team is headed by Dr Tamsyn Barton, ICAI’s chief commissioner. ICAI’s other commissioners are Tina Fahm and Richard Gledhill. Tamsyn Barton commenced her term as chief commissioner in January 2018 (taking over from Dr Alison Evans, who stepped down from ICAI to become Director-General, Evaluation, at the World Bank Group). The commissioners’ biographical details are published on the ICAI website.

ICAI’s secretariat is headed by Ekpe Attah and is made up of ten civil servants. They are accountable for business delivery, contract management, communications and engagement. A team of review managers from the secretariat works alongside the service provider to deliver the reviews. The secretariat is based in Gwydyr House, Whitehall.

Agulhas Applied Knowledge, a specialist international development consultancy, is ICAI’s external supplier. During Phase 2 Agulhas has been supported by Integrity, a development consultancy which specialises in working in complex environments, and Ecorys, an international company providing research, consultancy and management services.

Assessment of supplier performance in 2018-19

The supplier consortium continues to deliver high-quality technical knowledge and expertise on a wide range of ODA-related topics throughout the review process, from scoping to participation in IDC hearings. It has demonstrated a high degree of flexibility and consistently high performance in meeting ICAI compliance standards for conflict of interest and security clearances and in supporting the commissioners at IDC hearings.

2018-19 has seen significant change in ICAI, with an incoming chief commissioner and retendering of the supplier contract. Despite the potential for operational disruption, continued close working between the ICAI secretariat, the commissioners and the supplier ensured that ten reviews were delivered between July 2018 and July 2019.

Corporate governance

ICAI’s commissioners, who lead the selection process for and production of all reviews, were appointed after a recruitment process overseen by the Commissioner for Public Appointments. They hold quarterly board meetings, the agendas and minutes of which are published on our website.

Our primary governance objective is to act in line with the mandate agreed with the Secretary of State for International Development, set out in our Framework Agreement with DFID.

The cross-government focus of ICAI’s work was reiterated in the UK aid strategy, published in November 2015. This whole-of-government strategy included a commitment to sharpen oversight and monitoring of spending on ODA and emphasised that ICAI is one of the means of conducting this scrutiny and ensuring value for money, irrespective of the spending department.

Risk management

Our approach to risk management is pragmatic. We identify, manage and mitigate risks to an appropriate level in line with what is required to achieve our aims and objectives.

We have a corporate risk register which identifies and monitors ICAI’s corporate risks. This is reported monthly to the ICAI commissioners. Risks relating to individual reviews are monitored and we also monitor supplier risks as part of the monthly contract management meetings.

ICAI’s risk registers include an assessment of gross and net risk, mitigating actions and assigned risk owners. Risk is discussed regularly and is included as a standing item at every board meeting where commissioners review risks in detail.

Annual audit

ICAI is subject to annual audit coverage, undertaken by DFID’s Internal Audit Department, to provide assurance to ICAI and DFID on the effectiveness of the systems and processes in place to manage risk and deliver objectives. This year the audit looked at:

- follow-up on last year’s audit on transition to ICAI Phase 3

- ICAI’s alignment with the Cabinet Office’s Code of Good Practice for Partnerships between Departments and Arm’s-length Bodies

- management of ICAI’s conflict of interest (COI) policy

- ICAI’s risk management approach.

The audit confirmed that good progress has been made on the ongoing transition process, that ICAI is operating in line with the Code of Good Practice, that COI risks are well managed, with a clear process across the secretariat, commissioners and the service provider, and that the overall design and operation of ICAI’s controls are managing risks within appetite.

Conflict of interest

ICAI takes conflicts of interest, both actual and perceived, extremely seriously. Our independence is vital for us to achieve real impact.

Our Conflict of Interest and Gifts and Hospitality policy is included on our website. We update the Commissioners’ Conflict of Interests Register every six months. We maintain an internal register for secretariat staff and review potential conflicts of interest for all supplier team members before beginning work on reviews.

Any conflict of interest is managed in a transparent way and decisions are taken on a case-by-case basis. The specialist nature of our work, and the requirement for strong technical input, means that we need to weigh the risk of a possible or perceived conflict with the need to ensure high-quality and knowledgeable teams conduct our reviews.

Whistleblowing

ICAI’s capacity to investigate concerns raised by the public is limited, and not part of our formal mandate. Our whistleblowing policy can be found on our website.

In line with the policy, if we receive allegations of misconduct we offer to put the complainant in contact with the relevant department’s investigations team, if appropriate, or with the National Audit Office’s investigations function.

Safeguarding

ICAI has updated its safeguarding policies during the year. ICAI complies with all DFID safeguarding and reporting standards. There have been no reports this year under its safeguarding policy.

Financial summary

This chapter sets out:

- the overall financial position of ICAI

- ICAI’s work cycle

- expenditure from July 2018 to June 2019

- spending plans for the forthcoming year.

Overall financial position

ICAI has been allocated a budget of approximately £13.5 million for 2015-19. We estimate that we will have spent £12.4 million by the end of June 2019. The underspend of £1.1 million over the four years of Phase 2 between July 2015 and June 2019 is largely attributable to a reduced number of reviews in the first year of Phase 2, as a result of the transition to new commissioners. We have ensured that our work programme as we transition from Phase 2 to Phase 3 will not suffer similar disruption.

ICAI’s work cycle

ICAI implements a rolling programme of reviews. On average, full ICAI reviews take around nine months to complete and the shorter, rapid reviews take around six months to complete. Costs payable this year also include initiation costs for work on reviews for the following year.

We have included a separate section (see Table 3) which sets out supplier costs per review for reviews published in 2018-19.

Expenditure from July 2018 to June 2019

Table 2 provides a breakdown of 2018-19 expenditure. The table includes actual expenditure for July 2018 to March 2019, and forecasts for the period from April to June 2019.

Between July 2018 and March 2019, ICAI spent £2.405 million. We anticipate spending a further £845,000 between April and June 2019, meaning that by the end of June we will have spent around £3.250 million.

Table 2: Expenditure July 2018 to June 2019

| Area of spend | Actual expenditure July 2018 to March 2019 (£k) | Forecast expenditure April to June 2019 (£k) | Total forecast expenditure in 2018-19 (£k) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier costs | 1,700 | 563 | 2,263 |

| Engagement activities | 17 | 8 | 25 |

| Total programme spending | 1,717 | 571 | 2,288 |

| Commissioner honoraria | 127 | 45 | 172 |

| Commissioner expenses | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Commissioner country visit travel, accommodation and subsistence | 3 | 9 | 12 |

| Commissioner training | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| FLD* secretariat staff costs | 270 | 114 | 384 |

| FLD* staff expenses | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| FLD* staff country visit travel, accommodation and subsistence | 9 | 3 | 12 |

| FLD* staff training | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Total frontline delivery (FLD)* spending | 416 | 179 | 595 |

| Secretariat staff costs | 228 | 76 | 304 |

| Staff expenses | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Staff country visit travel, accommodation and subsistence | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Staff training | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| ICAI accommodation and office costs | 34 | 15 | 49 |

| Total administrative spending | 272 | 95 | 367 |

| Total | 2,405 | 845 | 3,250 |

*FLD or frontline delivery costs relate to staff and associated expenses which are directly associated with running programmes.

ICAI spends most of its money on supplier costs. In 2018-19, costs of the supplier consortium for its work in the production of reviews (programme spend) will be around £2.3 million.

Some of this cost will be for initiating the work on Phase 3 reviews to maintain the pipeline of review production. Our pipeline is designed to achieve our corporate objective of delivering six to eight full reviews per year together with a selection of other products, including rapid reviews, follow-up reports, annual reports and information notes for the IDC.

ICAI’s administration budget will continue to be carefully managed to ensure that all expenditure contributes directly to meeting ICAI’s objectives. In keeping with the Tailored Review recommendation in 2017, we will continue to seek further efficiency savings on relevant administration costs.

Table 3 sets out total supplier costs for each review published in 2018-19.

Table 3: Supplier costs for reviews published in 2018-19

| Review | Total costs paid to the supplier |

|---|---|

| Achieving value for money through procurement Part 2: DFID’s approach to value for money through tendering and contract management | £342,144 |

| DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments | £257,673 |

| DFID’s contribution to improving maternal health | £287,929 |

| The UK’s approach to funding the UN humanitarian system | £277,573 |

| International climate finance: UK aid for low-carbon development | £256,088 |

| CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states | £335,529 |

| DFID’s partnerships with civil society organisations | £309,444 |

| The Newton Fund | £279,998 |

| The current state of UK aid: A synthesis of ICAI findings from 2015 to 2019 | £131,152.50 |

| Follow-up | £192,184.50 |

| Annual report* | £5,386 |

*The Annual report is compiled by the ICAI secretariat with minimal support from the supplier.

The variation in the costs of ICAI reviews is driven by:

- the breadth of the topic under review

- the methodological approach required to provide robust, credible scrutiny of the topic (including whether and how many country visits may be required).

Where relevant, our reviews entail country visits. Commissioners undertook three country visits and ICAI secretariat staff visited a further five countries as part of the evidence gathering for reviews.

Spending plans for 2019-20

During 2019-20 we plan to continue with our published work plan and we anticipate spending approximately £3.8 million between July 2019 and June 2020.

ICAI’s performance

This chapter sets out performance during the year, including:

- overall number and type of reviews published, including follow-up on previous reviews

- levels of media/public engagement with our work

- performance against budget.

Table 4: Performance summary

| Key performance indicator | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Reviews published | 10 reviews 1 annual report |

| External engagement* | 22 |

| Finance | ICAI operates within authorised budget |

* External engagement figures refer to the period from July 2018 to May 2019.

ICAI completed ten reviews, seven performance reviews, one impact review, a follow-up review of last year’s recommendations and a synthesis of ICAI findings from 2015 to 2019.

The government has six weeks to publish a response to an ICAI review. By the end of May 2019, we had received responses from the government for seven of our reviews published in 2018-19. To date, all of ICAI’s recommendations this year have been accepted or partially accepted by the government.

Efficiency

ICAI continues to deliver within budget while delivering its planned programme of work. Overall, in the financial year 2018-19, ICAI remained within its budget by operating with tight financial controls over key areas of spend. ICAI continues to scrutinise all areas of its expenditure to drive continued improvements in its operational efficiency.

Follow-up on 2017-18 reviews

Through the annual follow-up review, we found a range of positive actions relating to 2017-18 ICAI reviews, leading to significant progress in several areas of UK aid, most notably:

- UK aid and the national interest: In 2017-18 we reviewed two cross-government funds: the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) and the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF). In this year’s follow-up review, we also looked again at the Prosperity Fund, which we reviewed in 2016-17. We found that there has been a sustained effort by these funds to review their governance controls, with notable improvements in the monitoring and evaluation of the funds.

- Do no harm: A key principle of good development practice is that aid programmes should avoid causing inadvertent harm to vulnerable individuals, particularly in conflict-affected settings. Our review of the CSSF recommended that programmes should do more to mitigate the risks of doing harm. We found that the CSSF has strengthened its guidance and training, and introduced new processes, related to the identification, management and mitigation of risks of doing harm. In our 2016-17 review on the UK’s aid response to irregular migration, we recommended that interventions should be underpinned by careful analysis of the drivers of conflict and human rights risk. In this year’s follow-up we found that the programme team is rigorously following its ‘do no harm’ approach in the assessment stage, and we have seen several thorough political economy, human rights and conflict sensitivity assessments.

- Disability: In December 2018 DFID published its Disability Inclusion Strategy, which set specific and ambitious standards for all DFID’s business units. While it is too early to assess the impact of the strategy, it addresses many of ICAI’s recommendations, such as adopting a more visible and systematic plan for mainstreaming disability inclusion, increasing the representation of staff with disabilities at all levels of the department, engaging with disabled people’s organisations and increasing its programming on tackling stigma and discrimination and psychosocial disabilities.

Working with the International Development Committee

Our relationship with the IDC is vital in ensuring effective scrutiny of UK aid. We have worked closely with the committee’s members and clerks throughout the year, for example to ensure ICAI’s review of International Climate Finance complemented the IDC’s wider inquiry into climate change. This strong relationship has bolstered parliamentary scrutiny, with ICAI’s reviews frequently being cited by IDC members when probing the government.

The IDC signs off ICAI’s work plan and holds public hearings into ICAI reviews. A change in the format of these hearings, so that ICAI and the government appear at the same time and can therefore respond to each other, has proved successful.

Paul Scully MP, chair of the International Development Committee’s sub-committee on the work of ICAI, said:

“ICAI continues to make an important contribution to the Committee’s work.

“Over the past 12 months, ICAI has published ten reviews, spanning a wide range of objectives of the UK aid strategy, government departments and other partners involved in aid delivery. ICAI also gave oral evidence at ten Sub-Committee sessions and supported the Committee’s inquiry on DFID’s work on disability.

“2019 marks the start of a new phase in ICAI’s existence under the leadership of its new Chief Commissioner, Dr Tamsyn Barton, who took up post in January. I should also like to thank Dr Barton’s predecessor, Dr Alison Evans, for her valuable work over the past four years scrutinising UK aid spending and supporting the work of the International Development Committee.”

External engagement

From July 2018 to the end of May 2019, ICAI held nine learning events focused on our reviews with relevant government departments, civil society organisations and the private sector, and participated in 13 events related to the wider context of aid scrutiny.

ICAI’s digital presence continues to grow. ICAI now has over 5,700 Twitter followers, an increase of over 18% since June 2018. There has been steady traffic to the ICAI website, with over 4,574 unique downloads of reviews published since July 2018.

ICAI reviews continue to attract national and sector press coverage, with 57 mentions for reviews published this year.

Between February and April 2019, ICAI consulted publicly on what topics it should review over the next four years and how, if at all, it should update its methodology. More than 100 responses were received from a wide range of stakeholders and members of the public, which have provided very helpful input to help ICAI develop its work plan. Further details of the consultation will be published separately.

Annex 1 ICAI’s work plan July 2019 to June 2020

ICAI’s current projected work plan for July 2019 to June 2020 is updated throughout the year on our website. Reviews under way include:

| How UK aid learns | UK aid to Ghana | Part 1: Sexual violence in conflict Part 2: Sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers | The African Development Bank | Mutual prosperity |