UK aid for sustainable cities

1. Purpose, scope and rationale

The UK has long recognised the multiple challenges and opportunities posed by rapid urbanisation in developing countries. In 2015, the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) produced its Sustainable cities for growth policy framework, which set out three objectives for its support to urban development: generating economic growth; ensuring that growth is inclusive; and promoting sustainability and resilience.

This review of UK aid in support of sustainable cities – one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – will examine the UK’s urban development portfolio from an economic, social and environmental perspective, in accordance with the UK government’s stated objectives, and will examine the extent to which the portfolio is contributing to the delivery of the UK’s climate and sustainability goals. This is an area that has not yet received detailed attention from the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) or other scrutiny bodies.

The review provides an opportunity to build on previous ICAI work, including the 2018 review of DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments. It adds to a number of previous ICAI reviews exploring different aspects of the UK’s international climate finance. Sustainable cities is also the only SDG yet to be addressed under ICAI’s Third Commission.

The review covers both bilateral and multilateral programming over the 2015 to 2022 period. It covers aid-funded investments and research programmes, as well as grant-funded programmes, whether national or multi-country. It also covers the UK’s policy engagement and international advocacy on the theme of sustainable cities, and its efforts to mobilise other sources of finance, especially from the private sector. While the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is the primary spending department, the review also covers the work of other departments and bodies.

2. Background

The UN’s most recent World Urbanization Prospects projects that more than two-thirds of the global population will reside in urban areas by 2050. Developing countries are expected to see the biggest increase, with Asia and Africa accounting for nearly 90% of urban growth.

Urban areas are recognised as catalysts for economic growth. The clustering of businesses, industries and services in cities generates economies of scale and positive spillovers such as innovation and entrepreneurship, resulting in higher productivity and job creation. This dynamic environment is a key driver of global economic prosperity, with cities generating more than 80% of global GDP.

However, many cities are also characterised by congestion and other developmental challenges, including serious social and environmental issues. The UN reported that, in 2020, approximately 1.1 billion urban residents lived in slums or informal settlements. Over the next 30 years, an additional two billion people are expected to reside in such conditions, primarily in developing countries.

Good governance is a key enabler of sustainable urban development. The capacity of national, regional and local authorities (in dialogue with private sector and civil society actors) to plan, coordinate and deliver urban services and infrastructure is one of the most important factors affecting successful city development. In many countries, weaknesses in urban governance systems are a barrier, requiring technical assistance, capacity building and reform.

Another area of concern is climate change. According to a World Bank report, Thriving: making cities green, resilient, and inclusive in a changing climate, cities are responsible for 70% of global carbon emissions. While urban areas in high- and upper-middle-income countries generate the most emissions, cities in low- and lower-middle-income countries face the challenge of continuing to grow sustainably in ways that do not harm the environment. The report also indicates that cities in developing countries are less resilient to climate change-related shocks and stresses, experiencing more severe economic impacts from extreme weather events.

Cities therefore occupy a central position in global sustainability efforts. They are at the heart of the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda: the main objective of SDG 11 is to create “inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable” cities and communities, with a focus on ensuring access to basic services, energy, housing, transport and green public spaces. These principles align with the core tenets of the New Urban Agenda, agreed at the 2016 Habitat III conference, and the Paris climate agreement.

The UK has placed sustainable cities, particularly in rapidly urbanising countries in Africa and Asia, at the core of its global efforts to address climate change. In the March 2023 International climate finance strategy, ‘sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport’ is one of four priority areas for UK international climate finance.

The UK’s approach to sustainable cities has been operationalised through a range of delivery mechanisms, including bilateral programming, both centrally managed and country-led, and multilateral programmes, as well as development investment. On a preliminary assessment, the sustainable cities portfolio includes around 100 programmes, projects or investments in developing countries with a range of objectives, including climate change mitigation and adaptation, promoting economic growth, poverty reduction and the development of safe and inclusive cities. FCDO manages the majority of the programmes, while the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) each manage smaller portfolios. Development investments are managed by the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG) and British International Investment (BII).

Between 2015 and 2022, UK aid support for sustainable cities amounted to £861.3 million. This included £486.3 million spent via bilateral programmes (£266.2 million of which was spent through multilateral partners), in the form of grants. It also included £375 million in development investment via PIDG and BII, which was invested in private sector opportunities with a view to generating positive development impacts while at the same time making a financial return. It is likely that this total figure under-represents the actual UK spending on sustainable cities as it does not include the share of the UK’s core contributions to multilateral funds that also spend in this area. There is also a wider range of programming in related sectors such as infrastructure, sanitation, finance and governance not necessarily badged as ‘sustainable cities’, which has not been included in the above figures.

3. Review questions

This review will examine how well the UK is using official development assistance (ODA) to support sustainable cities, with a particular focus on how it is balancing three sets of objectives: economic (growth and prosperity), social (inequality and poverty) and environmental (climate change, sustainability and resilience). The review will also look at how well the UK is improving governance arrangements, to help cities achieve these objectives. The review questions are built around the evaluation criteria of relevance, effectiveness and coherence. Our review questions and sub-questions under each of these criteria are set out in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: Does the UK have a clear and credible approach to promoting sustainable cities that aligns with its broader objectives? | • To what extent does the UK’s sustainable cities portfolio balance the objectives of climate change adaptation and mitigation, promoting economic growth, poverty alleviation and the development of safe and inclusive cities for marginalised groups, including women and children? • To what extent has the design of the sustainable cities portfolio focused on addressing the most significant constraints to sustainable urbanisation? • How well does the UK aid approach to sustainable cities support inclusive urbanisation and economic growth and poverty reduction? • How well does the UK’s approach align with the policies and priorities of local actors responsible for management and governance of cities and promote accountable governance? |

| Effectiveness:How effectively is the UK’s support for urban programmes achieving its intended results on sustainable cities? | • How effectively has UK aid contributed to making cities more prosperous, inclusive and sustainable? • How well does the UK mobilise other sources of finance for sustainable cities, including multilateral funding and private investment? • How well does the UK use its influence to strengthen the effectiveness of multilateral programming? • Is FCDO making efforts to maximise value for money? |

| Coherence: How coherent is the UK’s approach to promoting sustainable cities? | • How well does the UK ensure coherence across its ODA programme to promote action on sustainable cities? • To what extent does UK aid complement the efforts of other development partners to promote action on sustainable cities? |

4. Methodology

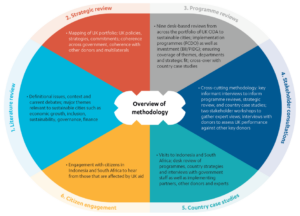

The methodology for this review will involve six main components to address our review questions and ensure sufficient triangulation of the evidence (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Methodology

Component 1 – Literature review: A review of the available peer-reviewed and grey literature, commenting where appropriate on the quality of evidence underlying the main conclusions. The literature review will assess the evidence base on the context and current debates around major themes related to sustainable cities, such as economic growth, inclusion, sustainability, municipal governance and finance.

Component 2 – Strategic review: A review of the strategies, policies and commitments relevant to the UK’s sustainable cities portfolio. We will supplement this desk-based research with key informant interviews with staff from UK government departments and other bodies, including PIDG and BII. This component will assess whether, and how well, the UK’s approach effectively balances economic, social and environmental objectives.

Component 3 – Programme reviews: Desk reviews of a sample of programmes and investments through different channels and instruments. We have selected a sample of programmes based on the criteria described in Section 5, which includes programmes operating in our case study countries.

Component 4 – Stakeholder consultations: A cross-cutting component of our methodology, key informant interviews will support our programme reviews, strategic review and country case studies. In addition to interviews with UK government officials, we will interview external stakeholders, including bilateral and multilateral development agencies, subject matter experts, and city officials.

Component 5 – Country case studies: Two country visits to Indonesia and South Africa. The case studies will assess the UK’s aid support for sustainable cities in each country, collecting and analysing evidence on the relevance, effectiveness and coherence of the UK’s programmes and contributions.

Component 6 – Citizen engagement: National research partners will hold consultations with people directly and indirectly affected by UK aid support for sustainable cities in Indonesia and South Africa. The consultations will aim to determine whether the UK’s aid support for sustainable cities is relevant to and addresses citizens’ needs and priorities, and whether aspects of their lives have changed as a result.

5. Sampling

Our methodology involves two sampling components: a selection of programmes for desk review and a selection of case study countries.

We have used several criteria to support the sampling of the portfolio of projects and programmes within this review – all of which are considered important factors in influencing the degree to which results claimed by departments have been met. For the programme reviews, our sample was selected from 98 programmes that the UK government identified as part of its sustainable cities portfolio. We used purposive sampling based on seven principal criteria, as shown in Table 2. Nine programmes were then selected as offering a representative sample across these criteria (listed in Table 3).

Table 2: Sampling criteria applied in this review

| Principal criteria | Categories |

|---|---|

| Overall project/programme goal | Governance and city powers; infrastructure; poverty reduction; climate change; finance |

| Funding channel | Bilateral; multilateral; multi-bilateral; private sector |

| Programme type | Centrally managed programme; country-led programme; multi-donor trust fund; development investment |

| Department/agency | FCDO; DESNZ; Defra; BII; PIDG; Asian Development Bank; World Bank |

| Geography | Africa; Asia; Latin America |

| Spending commitment | High spend: Greater than £100,000,000 Moderate spend: £10,000,001 to £100,000,000 Low spend: Less than £10,000,000 |

| Intervention type | Technical assistance; development investment (direct/intermediated); research; funding/accountable grants |

Table 3: Sample of programmes selected for desk review

| Programme name | Description |

|---|---|

| Cities and Infrastructure for Growth (CIG) (£167 million) | • Designed to be FCDO’s largest bilateral and centrally managed programme in the sustainable cities portfolio, operating in Uganda, Zambia and Myanmar. It aims to provide technical support to help city economies become more productive, deliver access to reliable and affordable power for businesses and households, and strengthen investment in infrastructure services. |

| Infrastructure and Cities for Economic Development (ICED) (£33 million) | • A former DFID centrally managed programme operating globally, which aimed to improve the enabling environment for sustainable, inclusive and growth-enhancing infrastructure service delivery, including harnessing the benefits of cities for sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction in DFID focus countries. • FCDO’s Green Cities and Infrastructure Programme (GCIP), which sits under the Green Cities and Infrastructure Centre of Expertise, builds on the work of ICED. |

| Global Future Cities Prosperity Fund (GFCP) (£80 million) | • A major FCDO centrally managed programme in the sustainable cities portfolio. It aimed to work with a select number of cities in middle-income countries to improve the way cities are planned and managed, increase local prosperity and quality of life, and create mutually beneficial trade opportunities for the UK in sectors where the UK has a comparative advantage. It has since been succeeded by country-led future cities programmes. |

| Support to Bangladesh’s National Urban Poverty Reduction Programme (NUPRP) (£56 million) | • A bilateral country-led programme operating in 19 cities and towns in Bangladesh. It aims to inform overall urban policy and poverty reduction through improvements in the integration of poor communities into municipal planning, budgeting and management, with a particular focus on women and girls and climate resilience. |

| Climate Leadership in Cities (CLiC) (£28 million) | • A moderately sized FCDO centrally managed programme, which aimed to support cities in developing countries to plan, and attract finance for, ambitious climate actions in Asia, South America and Africa. • FCDO’s recent Urban Climate Action Programme (UCAP), which began in April 2022, is a successor to CLiC. |

| Managing Climate Risks for Urban Poor (£85 million) | • A large multi-donor trust fund in partnership with the Rockefeller Foundation, the Asian Development Bank, and other donors. It aims to help cities plan for, and invest in, reducing the impacts of weather-related changes and extreme events for two million poor and vulnerable people in 25 medium-sized cities in six Asian countries. |

| African Cities Research Facility (£33 million) | • FCDO’s largest ODA-funded research programme in the sustainable cities portfolio. It aims to produce new operationally relevant knowledge and evidence to help policymakers and those who manage cities tackle the most significant problems constraining growth and development. |

| PIDG Investments ($61 million) | • A series of PIDG investments, with technical assistance support, funding the construction of environmentally friendly student accommodation in a major city of a lower-middle income country. |

| BII Investment ($35 million) | • A direct equity investment commitment to a low-cost housing platform, which aims to provide quality, low-cost and environmentally sustainable housing for low- and middle-income households in underinvested neighbourhoods in major cities of an upper-middle income country. |

Our country case study sampling process also took account of practical considerations, including the need to avoid overburdening FCDO staff in countries recently visited by ICAI. The countries were selected to ensure good coverage of the review’s themes (governance, infrastructure, poverty reduction, climate change and finance) and the range and depth of programming managed by different departments and arm’s-length bodies. We also considered the countries’ geographic, demographic, social and urban characteristics, such as the proportion of the population living in urban areas, number of megacities and levels of inequality. Based on these criteria, five potential case study countries were identified. Taking into account considerations such as national elections and safety concerns, Indonesia and South Africa emerged as the most suitable choices, covering both Asia and Africa.

Table 4: Case study countries

| Country | Reason for selection |

|---|---|

| Indonesia | Fifty-eight per cent of Indonesia’s population reside in urban areas,19 and the megacity of Jakarta is home to over ten million inhabitants. At the current rate of growth in urbanisation, it is projected that more than 73% of Indonesians will live in cities by 2030, increasing pressures on infrastructure, basic services, land, housing and the environment, and levels of urban poverty and inequality.20 The UK is committed to supporting sustainable and inclusive growth in Indonesia, and has provided aid for sustainable cities from several UK government departments including FCDO, Defra and the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, as well as via multilateral agencies. This includes both centrally managed, country-led programmes and multi-donor trust funds, and involves a range of intervention types such as technical assistance, ODA-funded research and accountable grants. |

| South Africa | South Africa is one of the most urbanised countries in Africa, with 68% of the country’s population residing in urban areas, mostly in a small number of major urban hubs.21 By 2035, it is projected that 74% of its population will live in cities. Cities are powerful economic engines in South Africa, but they are growing in resource-intensive ways while suffering from inefficiencies across different sectors, including energy, food, water, waste and transport. Climate change is also taking a toll on South African cities.22 The UK is committed to supporting South Africa’s ambitions for green recovery, sustainable growth and institution building,23 providing aid for sustainable cities across the UK government and via multilateral agencies. This includes both centrally managed, country-led programmes and multi-donor trust funds, and involves a range of intervention types such as technical assistance, development investment including BII, ODA-funded research and accountable grants. |

6. Limitations to the methodology

Geographical focus: Our choice of two upper-middle-income countries as case studies means that we will have less of a focus on programming in low-income settings. However, given the large inequalities of income and opportunity seen within the two case study countries, particularly in urban environments, we are able to look at programming aimed at poverty reduction. By visiting secondary cities in those countries, we will also gain insights into programming in lower-capacity environments. Our programme desk reviews will include programming in low-income countries.

Breadth of sampling: We have selected a sample of nine programmes and investments from the sustainable cities portfolio to review in depth, out of 98 programmes and investments identified as active over the review period, which span globally and operate across multiple focus areas relevant to sustainable cities. This will limit the extent to which we will be able to report findings which can be generalised across the whole of the UK’s sustainable cities portfolio. However, the sample is reflective of the UK’s strategic focus areas, and different types of spending and funding channels. Furthermore, we will be able to triangulate findings from our programme desk reviews and our strategic review, which will consider the wider sustainable cities portfolio. In addition, a consideration for selecting our country case studies is because they offer a breadth of programming across the main spending areas, allowing us to assess programming beyond our sample.

7. Risk management

We have identified several risks associated with this review and propose a series of mitigating actions, where necessary, as presented below.

| Risk | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| Capacity constraints within the responsible UK departments hamper access to information in a timely manner, or lead to incomplete information sharing. | We have initiated a constructive and collaborative relationship with FCDO and its points of contact with other departments in order to help with troubleshooting issues for the ICAI team. |

| Reduced evidence-gathering stage and team size limit the ability to cover all the material in the time period. | We have proposed a proportionate and robust methodology that focuses on deriving findings within achievable parameters. Our review topic has a relatively low level of spend and limited programming, which should result in time efficiencies. |

8. Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI Lead Commissioner Sir Hugh Bayley, with support from the ICAI secretariat. Our approach paper and the final report will be peer-reviewed by Claudette Forbes, a leading expert on city regeneration and former executive director of the London Development Agency. Our outputs will be subject to quality assurance by the service provider consortium.

9. Timing and deliverables

The review will take place over a nine-month period, starting from October 2023.

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach paper: January 2024 |

| Data collection | Country visits: November-December 2023 Evidence pack: February 2024 Emerging findings presentation: February 2024 |

| Reporting | Report drafting: March-June 2024 Final report: June 2024 |