Assessing DFID’s results in nutrition

Introduction

Overview

This literature review provides evidence to inform ICAI’s review assessing the UK’s Department for International Development’s (DFID) results in nutrition. The overall ICAI review questions are as follows:

- Effectiveness: How valid are DFID’s reported nutrition results?

- Equity: Are DFID interventions reaching the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach women and children?

- Impact: To what extent is DFID helping to reduce malnutrition?

The review questions were developed in 2019 to evaluate the UK’s current and previous work on nutrition, which at the time was being delivered through DFID. In order to maintain consistency with the review’s approach paper, these questions have not been updated to reflect the merger of DFID into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). As nutrition programming will continue, the questions remain relevant for continued UK programming.

DFID’s nutrition strategy over the last five years focused on tackling undernutrition. This literature review therefore focuses on undernutrition, while also considering the implications of the growing burden of overnutrition (Development Initiatives, 2020, p. 14).

Literature review approach

We began with a review of the literature that informed ICAI’s 2014 review of DFID’s nutrition work (ICAI, 2014). Building on this, an initial set of relevant, influential or widely cited documents relating to the literature review questions was identified and reviewed. This in turn led to the identification of further documents that were also reviewed.

For each of the three review questions, online searches were undertaken of academic, research and development literature written over the past 15 years, in order to identify further relevant documents. This included refereed articles, think tank reports, UN and non-governmental organisation (NGO) operational guidelines, policies produced by donor governments and multilateral international agencies and organisations. We categorised and analysed information relevant to the literature review questions, to identify evidence-based good practice.

Limitations of the literature review

This literature review does not provide detailed information on the evidence base and good practice for individual nutrition interventions. The range of possible and necessary interventions is too broad, as will be demonstrated in Chapter 3. Rather, the literature review identifies interventions with a strong evidence base, those where there is a need for further research, and explores how a range of interventions across multiple sectors is needed to achieve sustainable impacts on nutrition. The following section outlines core documents that are referred to throughout this literature review, and which provide detailed information on the evidence base and good practice guidance for individual interventions.

Overview of key literature

Nutrition actors benefit from a strong, synthesised evidence base on “what works” in reducing malnutrition and associated deaths, as well as a relatively comprehensive set of operational guidelines on how to implement interventions, compared with other development issues. The publications highlighted below are core documents that provide detailed evidence and operational guidance for nutrition interventions.

The Lancet journal produced three series of papers on nutrition in 2008, 2013 and 2019.These series of papers include analyses of studies examining the success of nutrition interventions. They also identify the interventions with the strongest evidence base in terms of their impacts on nutrition and associated mortality. The African Development Bank (AfDB) provides the most recent evidence review on the impact of a range of nutrition interventions, looking at both nutrition outcomes and intermediate outcomes (outcomes known to influence nutrition outcomes, for example household income or food expenditure) (African Development Bank, 2017b). For each of the AfDB’s relevant departments (Health, Agriculture, WASH, Social Protection), the report reviews the evidence base for:

- nutrition-specific interventions with evidence of impact on nutrition outcomes

- nutrition-sensitive interventions with a growing body of evidence showing impact on a range of intermediate outcomes

- the available guidance on how existing interventions can be made more nutrition-sensitive.

The strength of the evidence of impact for each intervention is rated on a scale.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) publication “Essential Nutrition Actions” (WHO, 2019a) is a comprehensive collection of nutrition-specific interventions which are recommended by the WHO to address malnutrition in all its forms. The purpose of the document is to aid decision-making processes for integrating nutrition interventions in national health policies, strategies and plans. The publication includes a checklist of essential nutrition actions at different stages of the life cycle of women and children. It also indicates the relevance of each intervention for specific settings and/or populations. This is followed by information on WHO recommendations, a summary of key evidence and key actions for implementation.

The WHO’s e-Library of Evidence for Nutrition Actions (eLENA) serves as an online library of evidence-informed guidelines for nutrition interventions and aims to provide a single point of reference for the latest nutrition guidelines, recommendations and related information. The extent to which these actions are implemented by countries is monitored through the WHO Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA).

The “Essential Nutrition Actions” document and eLENA are both important resources for implementing agencies, as well as for those assessing whether interventions are evidence-based and being implemented in line with good practice guidelines.

The United Nations (UN) Network for Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement and Renewed Efforts Against Child Hunger and Undernutrition (REACH) Secretariat have produced a “Compendium of Actions for Nutrition” (CAN) which comprehensively compiles, in one place, a concise description of all possible nutrition actions (UN Network for SUN and REACH, 2016). It also includes all of the essential nutrition actions recommended by the WHO (WHO, 2019a, p. 4). Actions are classified into three evidence categories: synthesised evidence exists; published primary studies exist; practice-based studies exist.

The CAN provides the most comprehensive ‘one-stop shop’ for evidence-based nutrition actions. Reviewers of nutrition programmes can use the CAN to check the strength of evidence underpinning different interventions and identify relevant implementation guidelines.

Report structure

The literature review is divided into five chapters, including this introduction. The second chapter is an overview of the global nutrition situation. The third chapter explores good practice in sustainably reducing undernutrition. The fourth chapter examines good practice in reaching the most vulnerable and the fifth examines good practice in measuring results of nutrition programmes and actions.

The global nutrition context

This chapter explores the nature, extent, causes and consequences of malnutrition, as well as the most vulnerable countries. It also outlines the benefits of investing in nutrition and provides an overview of key global commitments and initiatives designed to support reductions in malnutrition.

Malnutrition refers to deficiencies, excesses or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and/or nutrients. The term malnutrition covers two broad groups of conditions:

- Undernutrition, which includes stunting (low height for age), wasting (low weight for height), underweight (low weight for age) and micronutrient deficiencies (a lack of important vitamins and minerals).

- Overnutrition (high weight for height), which includes overweight[1] and obesity, both of which can cause diet-related non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes and cancer, and also excesses of micronutrients (DFID, 2017b, p. 5).

Undernutrition and overnutrition often co-exist in the same countries, communities, households and individuals. This co-existence is referred to as “the double burden of malnutrition” (Lancet, 2019, p. 2).

Levels and trends in undernutrition

Globally approximately 149 million children under five years of age suffer from stunting. The prevalence of stunting is declining (from 32.5% of children under five in 2000 to 21.9% in 2018), but it is still unacceptably high (UNICEF, WHO and World Bank Group, 2019, p. 3). In 2018, over 49 million children under five (7.3%) were wasted and nearly 17 million were severely wasted[2] (UNICEF, WHO and World Bank Group, 2019, p. 7).

More than half of all stunted children live in Asia and more than one third live in Africa. More than two thirds of wasted children under five live in Asia and more than one quarter live in Africa (FAO et al., 2020, p. 6). Africa is the only region where the number of stunted children under five has risen – from 50.3 million to 58.8 million between 2000 and 2018 (UNICEF, WHO and World Bank Group, 2019, p. 5). There are huge geographical variations in the prevalence of undernutrition within countries. For example, in India stunting varies between 12% and 65% across different districts (Menon et al., 2018, p. 1).

Some of the highest rates of undernutrition are found in countries affected by protracted conflict and fragility. Levels are significantly higher than the average for low- and middle-income countries. In fragile contexts, the average prevalence of childhood wasting is 11.8% compared with 8.9% in all low- and middle-income countries, and the average prevalence of stunting is 37% versus 25% (ENN, 2020, p. 2). In many of these countries, prevalence of global acute malnutrition is permanently higher than the 15% threshold, signifying a humanitarian emergency (Young, 2019, p. 2).

In a Call to Action to World Leaders in April 2020, food companies, farmers’ organisations, the UN, academics and civil society groups warned that as a consequence of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the number of people suffering from hunger on a daily basis, already estimated at over 800 million, could double, with a huge risk of increased malnutrition and child stunting (The Food and Land Use Coalition, 2020).

The causes of undernutrition

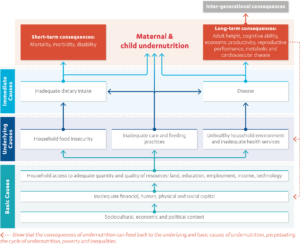

The widely referenced UNICEF conceptual framework of the determinants of child undernutrition (Figure 1) highlights the multiple factors that can cause undernutrition. Undernutrition is a consequence of an inadequate diet and disease, such as diarrhoea, pneumonia and tuberculosis. These immediate causes are a consequence of limited access to sufficient and nutritious food, inappropriate maternal and childcare practices, inadequate access to health services and to safe water and sanitation, and poor hygiene. Food, health and care are affected by social, economic and political factors including poverty, gender inequality, child marriage, poor education (especially for girls), political and economic marginalisation and poor governance (UNICEF, 2013, p. 4).

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of the determinants of child undernutrition

The double burden of malnutrition

Worldwide, 2 billion adults and over 40 million children under five years old are overweight or obese, leading to diet-related non-communicable diseases that contributed to 4 million deaths between 198 and 2015 (FAO et al., 2019, p. xiv). The number of children who are overweight or obese is increasing almost everywhere (UNICEF, WHO and World Bank Group, 2019, p. 10). People in low- and middle-income countries have the highest risks of dying from non-communicable diseases (Bennett et al., 2018, p. 1072). Increases in overnutrition are the result of changes in the global food system that make less nutritious food cheaper and more accessible, as well as a decline in physical activity (Popkin, Corvalan and Grummer-Strawn, 2019, p. 2).

The vast majority of countries (87%) are now experiencing a double burden of at least two types of malnutrition (Development Initiatives, 2020, p. 40). Evidence from many countries indicates that undernutrition and overnutrition can coexist in a country, a household and an individual (Nugent et al., 2019, p. 1). For example, over 8 million children experience both stunting and overnutrition (Development Initiatives, 2018, p. 42).

Undernutrition and overnutrition have an important common denominator: “food systems that fail to provide all people with healthy, safe, affordable, and sustainable diets” (Branca et al., 2019, p. 8). Poor diets are a major contributory factor to the rising prevalence of malnutrition in all its forms (FAO and WHO, 2019, p. 5). Suboptimal diets are responsible for one in five (22%) adult deaths globally (Afshin et al., 2019, p. 1959).

The High Level Panel of Experts of the Committee on World Food Security (CFS HLPE) defines a food system as: all the elements (environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures, institutions etc) and activities that relate to the production, processing, distribution, preparation and consumption of food, and the output of these activities, including socioeconomic and environmental outcomes (HLPE, 2014, p. 12).

Not only are food systems failing to provide people with healthy diets, they are both a cause of climate change and impacted by it. Currently, food systems generate 30% of greenhouse gases (IPCC, 2019, p. 10). Climate projections of 2°C warming suggest there will be an additional 540-590 million undernourished people and another 4.8 million stunted children globally by 2050 (Ebi et al., 2018, p. 4). Climate models estimate more than 500,000 additional deaths by 2050 due to climate-related changes in diets (Springmann et al., 2016, p. 1937).

The case for investing in nutrition

Malnutrition is a critical contributor to ill health, disability, vulnerability, poverty and excess mortality. It is responsible for five times the death and disability burden of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria combined. Undernutrition is a cause of 3.1 million child deaths annually, or 45% of all child deaths in 2011 (Black et al., 2013, p. 427).

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is highlighting the importance of nutrition. Good nutrition is essential for a healthy immune system. Malnourished people are more likely to become ill and die from communicable diseases. A malnourished child is nine times more likely to die of pneumonia than a well-nourished child. Those who are malnourished are therefore particularly vulnerable during pandemics such as COVID-19 (CFS HLPE, 2020, p. 2).

Children suffering from stunting may never attain their full possible height and their brains may never develop to their full cognitive potential. They face more learning difficulties in school, earn less money as adults, and face barriers to participation in their communities. Children suffering from wasting have weakened immunity, are susceptible to long-term developmental delays, and face an increased risk of death, particularly when wasting is severe. These children require urgent feeding, treatment and care to survive (UNICEF, WHO and World Bank Group, 2019, p. 7).

Malnutrition also has dire consequences for nations and economies. Malnutrition increases health care costs, reduces productivity and slows economic growth, which can perpetuate a cycle of poverty and ill health (WHO, 2018b). Poor nutrition is known to have devastating economic effects – studies estimate that stunting alone costs Africa $25 billion annually (African Development Bank, 2017a). Malnutrition in all forms could cost society up to $3.5 trillion per year, with overnutrition alone costing $500 billion per year (Development Initiatives, 2017, p. 21). Malnutrition is responsible for an 11% loss of gross domestic product (GDP) annually in Africa (IFPRI, 2016, p. xviii).

Averting malnutrition will help achieve at least 12 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), helping to create a healthy, prosperous and stable world in which no one is left behind (UN Network for SUN, 2019). Investing in child nutrition is key to creating human capital as nutrition is central to children’s growth, cognitive development, school performance and future productivity. Nutrition interventions are consistently identified as one of the most cost-effective development actions (Horton and Hoddinott, 2018, p. 367).

Reductions in stunting could increase overall economic productivity, as measured by GDP per capita, by 4% to 11% in Africa and Asia (Shekar et al., 2017, p. 14). Returns from investment in nutrition are high. Every dollar invested in reducing stunting generates an economic return equivalent to about $18 in countries with a high burden of malnutrition (UNICEF, 2019, p. 10). The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has calculated that an annual investment of $1.2 billion in improving the micronutrient supply globally, through a) supplementation, b) food fortification and/or c) biofortification of staple crops, would result in “better health, fewer deaths and increased future earnings” of up to $15.3 billion per year: a 13:1 benefit-to-cost ratio (FAO, 2013, p. 2).

Global commitments and initiatives to end malnutrition

Increasing recognition of the political, economic and social benefits of investing in nutrition has led governments to recognise nutrition as a priority within the global development agenda, set global targets for eradication and agree on international policy guidance to inform the development of national nutrition strategies and plans.

In 2012, the World Health Assembly (WHA)[3] endorsed the first-ever global nutrition targets, focusing on: achieving reductions in stunting, wasting, anaemia and low birth weight, preventing increases in overnutrition, and increasing rates of exclusive breastfeeding. At the Second International Conference on Nutrition in 2014, more than 170 governments committed to establish national policies and plans aimed at achieving the WHA nutrition targets (FAO and WHO, 2014a). They also agreed a set of policy options and strategies to guide the development of national nutrition plans (FAO and WHO, 2014b). In 2015, world leaders enshrined these commitments in SDG 2 and committed to end all forms of malnutrition by 2030 (United Nations, 2015).

Over the last decade a range of major global initiatives has been established, aimed at turning these global-level political commitments into coordinated action and accountability.

The Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement, established in 2010, is a collection of national governments and other stakeholders, including the UN, civil society, donors and businesses, which have committed to work together to set and achieve nutrition targets at the national level. Multi-stakeholder platforms have been established in member countries to strengthen national multi-sectoral nutrition plans, mobilise resources, oversee aligned implementation and monitor progress. National platforms are assisted by the SUN global support system, which brings stakeholders together at the global level in order to coordinate support in response to country priorities and needs. The SUN Movement promotes good practice in the planning and implementation of multi-sectoral nutrition programmes and interventions, monitoring progress and impacts, and mutual accountability for investments and actions.

In 2013, the UK co-hosted the first Nutrition for Growth (N4G) summit, which aimed to galvanise global efforts to tackle undernutrition, helping to secure £15.2 billion in new financial commitments (Nutrition for Growth, 2013, p. 1). The government of Japan was planning to hold a second N4G summit in Tokyo in December 2020 to mobilise new policy and financial commitments[4] (Government of Japan, 2019) . At the time of writing, the summit had been postponed until December 2021 in response to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The Global Nutrition Report, first published in 2014, provides updates on the state of nutrition around the world and progress in meeting nutrition targets and makes recommendations for actions to accelerate progress. The report also provides a mechanism for tracking progress against commitments made within the N4G process. The report aims to inspire action and help hold stakeholders to account on the commitments they have made towards tackling malnutrition.

The UN Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016-2025 (UNGA, 2016) aims to encourage increased nutrition investments, and implement policies and programmes to improve food security and nutrition within the framework agreed at the Second International Conference on Nutrition. It provides an umbrella for all relevant stakeholders and initiatives to consolidate and align actions across different sectors.

Progress in achieving nutrition targets

Despite these commitments and initiatives, the world is not on track to meet the WHA targets and SDG 2 (UNICEF, WHO and World Bank Group, 2019, p. 38). Several countries are on course to meet at least one of the globally adopted nutrition targets set for 2025, but most are off track, and none are making progress on the full set of targets (Development Initiatives, 2020, p. 13). Key factors hindering progress are very weak service delivery systems and capacities in low- and middle-income countries, and inadequate investments by domestic governments and donors (Development Initiatives, 2020, p. 13). There is widespread failure to turn political rhetoric into investments, scaled-up programmes and accelerated reductions in undernutrition (Development Initiatives, 2020, p. 26).

Good practice in sustainably reducing undernutrition – "what works"

This chapter reviews good practice in country-wide multi-sectoral, multi-stakeholder efforts to sustainably reduce undernutrition. Donor agencies are among a range of actors contributing towards the achievement of this common goal. Benchmarks for reviewing donor practices and results must be derived from an understanding of good practice in wider multi-stakeholder processes and the role of donors within them.

A framework for action to improve nutrition

Black et al. (2013, p. 428) present a widely utilised framework for action to achieve optimum foetal and child nutrition (Figure 2). This is an adaptation of the UNICEF conceptual framework (Figure 1) showing the means of promoting nutrition rather than the causes of undernutrition.

Figure 2: Lancet framework for action to achieve optimum foetal and child nutrition and development

Source: Adapted from Black et al., 2013, p. 428.

This framework is widely referenced in subsequent publications reviewing best practice as an evidence-based guide for the development of nutrition policies, plans and processes (for example see Quinn, 2013).

The framework highlights that if improved nutrition is going to be achieved and sustained, then a multi-sectoral, multi-stakeholder approach is required, addressing the different determinants of nutrition. Actions are classified into three broad groups:

(1) nutrition-specific interventions

(2) nutrition-sensitive interventions

(3) building an enabling environment.

Nutrition-specific interventions are those that address the immediate determinants of foetal and child nutrition and development, such as inadequate nutrient intake, caregiving and parenting practices, and infectious diseases (eg nutrient supplementation for women and children, support for infant and young child feeding, or treatment for acute malnutrition).

Nutrition-sensitive interventions are those that address the various underlying causes of undernutrition (eg household food insecurity, inadequate caregiving resources at the maternal, household and community levels, poor access to health services, and a safe and hygienic environment) and incorporate specific nutrition goals and actions (eg providing access to safely managed water and sanitation to prevent diarrhoeal disease, which contributes to undernutrition) (Ruel and Alderman, 2013, p. 2).

Actions to build an enabling environment include promoting high-level political commitment and leadership, policies and legislation, coordination mechanisms, technical capacities and financial resources. Enabling environments are “the wider political and policy processes which build and sustain momentum for the effective implementation of actions that reduce undernutrition” (Gillespie and Haddad, 2013, p. 553).

Nutrition-specific interventions

In the 2013 Lancet Series, Bhutta et al. (2013, p. 453) identify ten key nutrition-related interventions which have the strongest evidence base for their contribution to reductions in child mortality. They are:

- periconceptional folic acid supplementation or fortification

- maternal balanced energy protein supplementation

- maternal calcium supplementation

- multiple micronutrient supplementation in pregnancy

- promotion of breastfeeding

- appropriate complementary feeding

- vitamin A supplementation in children aged between six and 59 months

- preventive zinc supplementation in children aged between six and nine months

- management of severe acute malnutrition (SAM)

- management of moderate acute malnutrition (MAM).

The authors conclude that if these ten interventions were to be scaled up to 90% coverage, then the current total of deaths in children younger than five years could be reduced by 15%, stunting reduced by 20.3% (33.5 million fewer stunted children), and the prevalence of severe wasting reduced by 60% (Bhutta et al., 2013, p. 453). Additionally, access to and uptake of iodised salt can alleviate iodine deficiency and improve health outcomes. The interventions with the largest potential effect on mortality in children younger than five years are SAM, preventative zinc supplementation, and promotion of breastfeeding. Scaling-up interventions through community-based approaches can not only reduce the overall burden of childhood mortality but also substantially reduce existing inequities in access and mortality (Bhutta et al., 2013) – as discussed further in Section 4.4 below.

In addition to the ten nutrition-specific interventions identified by Bhutta et al. (2013, p. 453), the African Development Bank (AfDB) synthesis of evidence (African Development Bank, 2017b) identifies other interventions that have demonstrated impact on nutrition outcomes, including: intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and insecticide treated nets for pregnant women, iron and iron-folate supplementation for pregnant women, delayed cord clamping, iron supplementation for children, multiple micronutrient supplementation including iron for children, lipid-based nutrient supplementation for children, lactose-free diets during acute diarrhoea,[1] deworming for children, and intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in children.

Gillespie et al. (2019, p. 133) identified a core set of proven nutrition-specific interventions. They combined the recommended list in the 2013 Lancet Maternal and Child Nutrition Series (Bhutta et al., 2013) with current WHO global guidance for nutrition-specific interventions that can be feasibly delivered in low- and middle-income countries (WHO, 2019a).

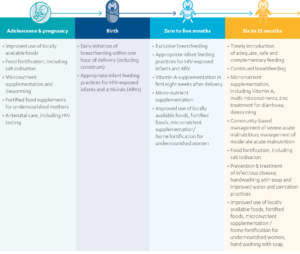

Different interventions are required at different points in the life course of mothers and children. Table 1 provides guidance on which evidence-based actions should be promoted when during the life cycle. The interventions are mostly nutrition-specific, although some nutrition-sensitive interventions are also included, including improved use of locally available foods, handwashing with soap, and improved water and sanitation facilities.

Table 1: Proven nutrition interventions throughout the life cycle

Source: Adapted from UNICEF, 2013, p. 18.

There is considerable evidence of positive health and nutrition outcomes resulting from integrating nutrition‐specific interventions into health systems, in particular, increases in breastfeeding initiation rates, improved recovery, reduced relapse of children with SAM and MAM, and improved coverage of vitamin A supplementation. Nutrition-specific interventions can be integrated into various programmes, including integrated community case management, integrated management of childhood illness, child health days, immunisation and early child development. However, current knowledge on establishing and sustaining effective integration of nutrition into health systems is limited (Salam, Das and Bhutta, 2019, p. 2).

Nutrition-sensitive interventions

If the estimate of Bhutta et al. (2013, p. 453) that nutrition-specific interventions have the potential to reduce stunting by 20% is correct, then the vast majority of improvements need to come from other types of programmes. “Acceleration of progress in nutrition will require effective, large-scale nutrition-sensitive programmes that address key underlying determinants of nutrition and enhance the coverage and effectiveness of nutrition-specific interventions” (Ruel and Alderman, 2013, p. 1). The evidence on the contribution of nutrition-sensitive interventions to improved nutrition is explored in the following sub-sections on agriculture, social protection, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), and women’s empowerment, as they are highly relevant to the underlying determinants of undernutrition and receive substantial attention in the literature.

Agriculture

Reviews show that agriculture programmes that promote production diversity, micronutrient-rich crops (including biofortified crops), dairy, or small animal rearing can increase production and improvements in access to nutritious foods and the quality of the diets of mothers and young children. There is limited evidence, however, on the impact on diets of adolescent girls and the elderly (Ruel, 2019, p. 95).

The AfDB report finds that interventions with the strongest evidence of impact on nutrition are biofortification, mass fortification and home vegetable gardening (African Development Bank, 2017b, p. 22). The evidence also suggests that aflatoxin control, animal rearing, aquaculture, irrigation and pricing policies may influence nutrition. Production diversification, improvement of processing, storage and preservation, and nutrition education are also supported by UN FAO guidelines (African Development Bank, 2017b, p. 23).

However, the evidence that agriculture programmes on their own have a direct impact on nutritional status is modest. There are some cases, especially with biofortified vitamin A-rich sweet potatoes, in which increased production and consumption led to improvements in vitamin A status and health in young children, but there is little evidence overall of impacts on child undernutrition. Agriculture programmes are most likely to have an impact on nutrition when combined with other interventions, including nutrition behaviour change communications, interventions to empower women, and WASH programmes (Ruel, Quisumbing and Balagamwala, 2018, p. 129).

Priority areas for further research include: evaluating long-term impacts and sustainability, how to scale up nutrition-sensitive agriculture programmes, the impacts of co-located sectoral programmes compared with integrated programmes offering the same interventions, and the importance of contextual factors in determining nutrition outcomes (Ruel, 2019, p. 100).

Social protection

Evidence of the impact of social protection interventions on maternal and child nutrition is limited. Grants, the most rigorously examined of these interventions, have been shown to have a mixed impact on child growth and development. In certain settings, however, grants have been found to have a positive impact on levels of haemoglobin and anaemia by increasing the ability of families to purchase foods rich in minerals and vitamins. The evidence suggests that grants, as well as asset transfers, in-kind transfers and user fee removal/vouchers for health services, can improve intermediate outcomes for health, including increasing food expenditure, dietary diversity, household income and participation in health services (African Development Bank, 2017b, p. 45).

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)

WASH interventions can potentially contribute to improved nutrition status by reducing diarrhoeal diseases, intestinal parasite infections and environmental enteropathy.[2] WASH interventions may also impact nutritional status indirectly by reducing the need to walk long distances in search of water and sanitation facilities, freeing up the time of mothers for childcare (Fenn et al., 2012, p. 1752).

WASH services and interventions have been found to have positive impacts on diarrhoea incidence and prevalence, and on the incidence of soil-transmitted helminth infections. The impact on diarrhoea depends on factors such as: the type and quality of the interventions, populations targeted, pathogens circulating in the environment, study design and methodological quality (WHO, UNICEF and USAID, 2015, p. 7).

Improvements to household water treatment and handwashing have a proven impact on nutrition outcomes (African Development Bank, 2017b, p. 36). A Cochrane review found evidence for a small but statistically significant effect of WASH interventions on stunting. The interventions reviewed improved water quality and/or hygiene practices and were of short duration. No study considered the effect of a complete package of WASH interventions (Dangour et al., 2013, p. 6).

The WHO systematically analysed over 1,000 studies between 2012 and 2017, finding that improved sanitation helped prevent infectious diseases and thereby contributed to improved nutrition outcomes, especially when entire community coverage of sanitation was achieved (WHO, 2018a, p. 13).

In 2018, three high-quality studies showed little or no impact of selected WASH interventions on reducing childhood diarrhoea and stunting (Null et al., 2018; Luby et al., 2018; Humphrey et al., 2019). In a review of these studies, the WHO concluded that the interventions failed to block all pathways for contamination of the environment, and thus prevent human exposure to faecal pathogens, and that improving WASH alone is unlikely to significantly reduce the high burden of stunting. The WHO calls for programming addressing context-specific risk factors, seeking to improve WASH for whole communities with a more comprehensive package of WASH interventions, in combination with other sectoral interventions (WHO, 2019b, p. 7).

Women’s empowerment

Women’s empowerment[3] interventions for nutrition include maternal education, maternal literacy and interventions which aim to improve women’s financial autonomy and participation in household decision making. There is emerging evidence that women’s empowerment and education could have a positive impact on child nutritional outcomes, as well as the potential to reduce wasting. There is some evidence to suggest that mothers with greater financial independence and participation in household decision making were more likely to breastfeed and had infants that were better nourished (Shroff et al., 2011, p. 1). In a study of the links between women’s empowerment in agriculture and the nutritional status of women and children in Ghana, Jean, Malapit and Quisumbing (2014, p. 54) found that women’s empowerment is more strongly associated with infant and young child feeding practices, and only weakly associated with child nutritional status, while women’s empowerment in credit decisions is positively and significantly correlated with women’s dietary diversity, but not body mass index.

Nutrition-sensitive programmes as delivery platforms for nutrition-specific interventions

Not only can nutrition-sensitive programmes contribute to improved nutrition, but they can also provide a vehicle for the delivery of nutrition-specific interventions. Nutrition behaviour-change communications, which are incorporated in several agriculture, social safety net, early child development and school health programmes, are one example. Other opportunities include the distribution of micronutrient-fortified products to nutritionally vulnerable adolescent girls, mothers and young children, or preventative health inputs to agriculture, social safety net, early child development or school programmes (Ruel and Alderman, 2013, p. 2).

Ways of optimising the nutrition impact of sectoral programmes

It is possible and necessary to adapt some interventions to increase their impact on nutrition. For example, programmes aimed at increasing the production of nutritious and healthy foods can focus on a diverse range of produce rather than only on staple foods. However, in many cases, there is no need to change the content of interventions but rather the methods of implementation. The literature provides a number of examples of how to optimise the nutrition impact of sectoral interventions (Alderman, 2016; FAO, 2017; Action Against Hunger, 2017) including:

- Facilitate production diversification and increase production of nutrient-dense crops and small-scale livestock.

- Identify interventions which address the context-specific causes and types of undernutrition.

- Include nutritionally vulnerable people in target groups.

- Integrate other types of nutrition interventions, such as nutrition education and behaviour change communication.

- Scale up social protection and other sectoral programmes during crises to prevent malnutrition.

- Empower women within sectoral programmes.

- Collaborate with other sectors and co-locate programmes in communities most at risk of undernutrition.

The contribution of nutrition-sensitive interventions to improved nutrition

In general, evidence of the impact of nutrition-sensitive interventions on nutritional status is limited. The literature gives three main reasons for this. First, nutrition-sensitive sectoral interventions can only address some of the underlying causes of poor nutrition (Ruel, 2019, p. 94). For example, while a social safety net or agricultural programme may improve access to food, children may still become malnourished if they do not have access to adequate sanitation and consequently become ill. Second, many sectoral programmes are not designed with improved nutrition as an intended outcome even though they have the potential to achieve this (Ruel and Alderman, 2013, p. 12). Third, despite improvements over the last few years there is a need to further improve the quantity and quality of evaluations of nutrition-sensitive interventions to better explore ways in which different sectoral interventions can contribute to improved nutrition (Leroy, Olney and Ruel, 2016, p. 131).

The evidence is clear that nutrition-sensitive interventions are effective in addressing underlying causes of undernutrition, particularly if their contribution to improved nutrition is an explicit consideration in the design and evaluation of programmes, and there is collaboration with other sectors to maximise collective impact (Ruel and Alderman, 2013, p. 2). Nutrition-sensitive interventions are therefore essential elements of a multi-sectoral approach to sustainably reducing undernutrition, even if the direct impact of any one intervention on nutrition outcomes is limited.

A comprehensive package converging on the same at-risk populations

Since nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions address different determinants of nutrition, a combination of both is needed to make the greatest possible improvements in maternal and child nutrition, and to sustain those gains (Ruel and Alderman, 2013, p. 2). “A comprehensive package of nutrition-specific interventions, coupled with nutrition-sensitive programmes, is the most likely to make a lasting impact on maternal and child nutrition” (Teague, 2017, p. 4). The literature also makes clear that the comprehensive package of interventions must be specific to the causes of undernutrition in any given context. There is no one-size-fits-all bundle of interventions that can be applied in all contexts.

Ruel and Alderman (2013, p. 12) ask whether it is better to have stand-alone nutrition programmes, which integrate actions from several sectors, or to co-locate programmes managed by different sectors so that they converge on the same at-risk populations. While it is logical to plan multi-sectorally, public services are implemented through sectoral processes. Budget allocations are made by sectors or ministries, and governance and accountability structures follow the same lines, with sectors holding themselves accountable for results within their own domains. It is therefore necessary to plan multi-sectorally and act sectorally, mainstreaming nutrition interventions and objectives into sectoral services and programmes (World Bank, 2013, p. 21).

In order to achieve sustained reductions in undernutrition, there is a need to converge proven interventions from different sectors on the same at-risk populations. However, the number and scale of interventions being implemented in any one location is often inadequate to significantly improve and sustain reductions in undernutrition (Development Initiatives, 2018, p. 42).

This cross-sectoral convergence is highly challenging as it requires, among other factors, high-level political leadership, cross-government coordination, multi-sectoral financial investments and skilled community-based workers. These enabling factors are discussed in more detail in Section 3.6 below. In reality, the requisites for convergence are not adequately in place in most contexts (Mokoro, 2015, p. 328). These challenges lead to demands for a focus on the shortest possible list of priority, evidence-based interventions, while enabling political and technical environments for improved convergence are being built. As described above, significant progress has been made in the last 15 years in identifying priority interventions and sectors. However, there is a need for continued research in order to further identify interventions and approaches which can contribute most to sustained reductions in undernutrition.

There is a trade-off between converging resources and interventions on a smaller number of people, and reaching more people with interventions which may have wider benefits for livelihoods, food security and health, even if they do not have a direct impact on nutrition outcomes. Ultimately, the choice is a political one and decisions will depend on the extent to which improved nutrition is considered to be a political priority, in terms of its contribution to economic and other national development goals. Advocates for improved nutrition need to make the case for cross-sectoral investments and coordination, while also promoting the integration of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions and approaches into wider sectoral programmes in ways which minimise costs and burdens on limited capacities (Baker et al., 2018, p. 12).

Addressing all forms of malnutrition through double-duty actions and food system transformation

As highlighted in Section 2.3, there has been a steadily growing recognition of the double burden of malnutrition around the world. Currently, actions to address different forms of malnutrition are typically managed by separate policies, programmes, structures and funding streams. For example, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Guatemala (three countries with a high double burden of malnutrition) have separate strategies and different interventions to tackle different forms of malnutrition. The Tanzania National Multisectoral Nutrition Action Plan, published in 2016, is a rare example of a strategy that explicitly aims to reduce both undernutrition and overnutrition. Nevertheless, it lists separate actions for different forms of malnutrition (Hawkes et al., 2019, p. 143).

In contrast, double-duty actions for nutrition aim to simultaneously prevent both undernutrition and overnutrition with the same intervention, programme or policy. The available evidence indicates that there are ten evidence-based areas where double-duty actions could be introduced across different sectors (Hawkes et al., 2019, p. 146):

- Implement WHO antenatal care recommendations.

- Programmes to protect, promote, and support breastfeeding.

- Redesign guidance for complementary feeding practices and related indicators.

- Redesign existing growth monitoring programmes.

- Prevent undue harm from energy-dense and micronutrient-fortified foods and ready-to-use supplements.

- Redesign cash payments and food aid, subsidies and vouchers.

- Redesign school feeding programmes and devise new nutritional guidelines for food in and around educational institutions.

- Scale up nutrition-sensitive agriculture programmes.

- Design new agricultural and food system policies to support healthy diets.

- Implement policies to improve food environments from the perspective of malnutrition in all its forms.

Double-duty actions are based on the rationale that all forms of malnutrition share common drivers that can be addressed with multiple impacts. These drivers include early life nutrition, diet diversity, food environments and socioeconomic factors (Hawkes et al., 2019, p. 142).

Recognising that undernutrition, overnutrition and diet-related non-communicable diseases are, to a significant extent, a consequence of unhealthy diets resulting from unsustainable food systems, there has been a growing demand for food system transformation (Wells et al., 2019, p. 1). This demand is also driven by the understanding that food systems are both a cause of, and impacted by, climate change (Willett et al., 2019, p. 1). The current COVID-19 pandemic has increased calls for the transformation of food systems to reduce the risk of, and increase resilience to, communicable diseases (Dutkiewicz, Taylor and Vettese, 2020).

Food system transformation involves changing the way in which food is produced, processed, distributed, prepared and consumed in order to increase sustainable access to nutritious food, reduce malnutrition, promote health and reduce negative impacts on the natural environment, including the climate (Committee on World Food Security, 2020, p. 4).

The High Level Panel of Experts of the Committee on World Food Security suggests policies and programmes that are considered to have the potential to transform food systems through: (1) improving food supply chains, for example producing nutritious foods through environmentally friendly farming practices, improving connectivity between rural and urban areas, and reducing food waste, (2) improving the quality of diets, for example phasing out advertising and promotion of unhealthy foods and regulating health claims on food packaging, (3) creating consumer demand for nutritious food, for example developing guidelines for healthy and sustainable diets and establishing evidence-based tax policies on foods of differing nutritional value (HLPE, 2017, p. 11).

Food system transformation requires better harmonisation between global, large-scale, industrialised food systems and local, smaller-scale, agro-ecological systems and actors. Changes in global and national governance, financing and technical capacities are required in order to promote double-duty actions and food system transformation (Hawkes et al., 2019, p. 142).

Building enabling environments

Bhutta et al. (2008, p. 435) argue that “the evidence for benefit from nutrition interventions is convincing. What is needed is the technical expertise and the political will to combat undernutrition in the very countries that need it most.” The Lancet framework for action (Figure 2) identifies some of the main actions that are required to promote an enabling environment for impactful nutrition programming and sustainable reductions in undernutrition. Building on the framework, this section describes good practice in this regard.

Build the enabling environment at sub-national as well as national levels

There has been considerable effort through the SUN Movement to build enabling environments at national level in SUN countries. However, there is increasing recognition that to scale up programming and achieve impact, attention needs to be given to leadership, processes and capacities at the sub-national level, especially in contexts of increasing political decentralisation (Manning et al., 2018, p. 31). Key decisions about priorities and resource allocation are increasingly made at sub-national levels, so political commitment, planning and other capacities must be built there, as well as at the national level (Bryce et al., 2008, p. 511).

Promote political leadership and commitment

High-level political leadership is necessary to promote coordination and coherence between sectors, the alignment of programmes of different stakeholders and the mobilisation of resources and mutual accountability (Baker et al., 2019, p. 30). Awareness raising and advocacy are often required to stimulate political commitment, so that politicians and senior government officials recognise the benefits of investing in a multi-sectoral approach to nutrition and for it to be a high national development priority (Arnold, 2013). Leadership needs to be at a sufficiently high level to convene across sectors and stakeholders, and promote the necessary coordination and alignment. This cross-government commitment then needs to percolate down to ministers responsible for each relevant sector to ensure nutrition is a priority within sectoral plans and programmes, and aligned with overall development objectives (Transform Nutrition, 2017, p. 6).

Ensure political and technical coordination

High-level political forums, involving representatives of government and development partners, are necessary to provide strategic and financial oversight. These are often not nutrition-specific but rather address nutrition as part of the broader sustainable development agenda. Many countries have also established multi-stakeholder platforms at a technical level in order to inform national policies, develop multi-sectoral plans and coordinate their implementation. It is essential to ensure the participation of the broad range of stakeholders (government, civil society, business, UN agencies, donors etc) in order to utilise comparative advantages and ensure alignment and accountability of actions, while also mitigating against conflicts of interest (Manning et al., 2018, p. 19).

Establish national targets, policies, legislation and plans

Some countries have developed national nutrition policies, committing to a multi-sectoral approach to nutrition (see for example Government of Malawi, 2018). These countries also produce common results frameworks, identifying the nutrition targets and outcomes which different sectors will contribute towards. Each sector then integrates actions to promote nutrition into its own plans (SUN Movement Secretariat, 2016b, p. xi). Policies and plans need to be informed by evidence and country-specific analysis of trends and causes of malnutrition, including risk analysis (SUN Movement Secretariat, 2016a, p. 4). However, plans are often limited in quality and overly ambitious given the limited capacities and financial resources (Mokoro, 2015, p. xiv). They need to be costed and prioritised in order to ensure resources are not spread too thinly with minimal impact, and accompanied by capacity building and resource mobilisation plans, which enable the scale-up of programmes as quickly as possible. Risk management actions need to be identified (including to mitigate the impact of shocks and emergencies and respond to them). Plans should identify clear and coherent divisions of responsibility between implementing agencies and identify respective roles on the basis of comparative advantage, ie who can deliver the desired results most efficiently, without causing undesirable impacts (SUN Movement Secretariat, 2016a, p. 39).

Strengthen national and local capacities

Capacities in coordination, planning, situation analysis, implementation, resource mobilisation, and monitoring and evaluation need to be built horizontally (across sectors) and vertically (from national to local levels). Even in conflict situations it is often possible to work with, and strengthen, public and other service providers, even if there is a need to maintain distance from political authorities in the interests of neutrality and impartiality (Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium, 2017, p. 2).

Galvanise more and better financing

The commitment of governments to improved nutrition for their citizens should be demonstrated through increased domestic resource commitments. Especially in an era of constrained international development assistance, there is increased expectation that national and local governments will assume an increasing share of the cost of service provision (Development Initiatives, 2018, p. 96). International donors are increasingly seeking to use their resources in a strategic manner to catalyse domestic, political and financial commitments and processes. Nutrition donors have further committed to follow the agreed principles of aid effectiveness of the Paris Declaration and the Accra Agenda for Action, including ensuring their own investments are aligned with national priorities and plans, and are well coordinated (SUN Donor Network, 2010).

Monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning

The implementation and results of nutrition programmes need to be monitored and evaluated continuously. This monitoring should include regular analysis of the contributions of different stakeholders through mutual accountability mechanisms (IFPRI, 2014, p. xxi). Lessons learnt should feed into improved planning and implementation, and be shared with others regionally and globally. The SUN Movement promotes the use of Joint Annual Assessments in SUN countries, in which all relevant stakeholders review progress towards building an enabling environment and the scaling-up of multi-sectoral programmes. Good practice in measuring results, promoting learning and mutual accountability are explored in more detail in Chapter 5.

Build an enabling environment at international level

Historically, global governance has been highly fragmented, resulting in countries being inundated by conflicting and inequitable advice and support (Morris and Cogill, 2008, p. 608). Country-level actions need to be supported in a coordinated and coherent manner, with policy, technical and financial assistance at the global level. The global initiatives described in Section 2.5 aim to improve the coordination and quality of country support. The Second International Conference on Nutrition provided policy guidance, the Decade of Action for Nutrition aims to mobilise commitments and actions, the SUN Movement aims to facilitate better coordinated support to member countries and the N4G process aims to mobilise financial and policy commitments, while the Global Nutrition Report tracks progress on commitments and impacts on rates of malnutrition.

Adapting practice in contexts of protracted fragility and conflict

In contexts of protracted crisis, where rates of undernutrition are extremely high over a long period of time, short-term humanitarian responses are not appropriate (FAO, 2016, p. 13). There may be a need for multi-year emergency programmes alongside national sectoral programmes, and to strengthen these, where long-term sectoral capacities are outstripped.

In contexts where there are frequent shocks (such as droughts, floods and conflicts), long-term nutrition programmes should be flexible so that they can be scaled up in response (OECD DAC, 2019). Emergency interventions should not be regarded as a separate sector but as a scale-up of longer-term programmes. Many emergency responses are identical to interventions used in non-emergency settings, ie the management of severe and acute malnutrition, the delivery of micronutrients, treatment of diarrhoea with oral rehydration therapy or zinc, and the prevention and treatment of vitamin A deficiency (African Development Bank, 2017b, p. 57). In emergencies, the rapid scale-up of coverage may require different and accelerated protocols.

The AfDB (2017, p. 58) identifies four interventions which it considers specific to emergency settings: general food distribution, supplementary food and nutrition assistance (including assistance targeted at vulnerable populations), infant and young child feeding, and psychosocial support with nutrition response. However, even these could be seen as extensions of, or complementary to, longer-term interventions. For example, general and supplementary distributions could be a scaling-up of an existing social protection programme providing financial or in-kind food resources to vulnerable people.

In contexts where governments or other political authorities are contributing to undernutrition, for example as parties to conflict, it may not be desirable or feasible to promote political ownership. It is necessary to ensure that programmes are implemented in accordance with humanitarian principles. This often requires programmes to be implemented by UN and non-government humanitarian organisations, whose independence, neutrality and impartiality help ensure access to affected populations (IFPRI, 2016, p. 44). However, even in these circumstances it may still be possible to implement at least some interventions through national service delivery systems, and to strengthen these, thereby promoting early recovery and longer-term sustainability.

The special needs of fragile situations may require the adoption of interim nutrition strategies in place of a national plan and programmes. Though creating a sustainable, multi-sectoral approach to prevent malnutrition should remain a priority in conflict situations, there may be a need to prioritise interventions to save lives and meet immediate needs (IFPRI, 2016, p. 111).

What is good practice in reaching the most vulnerable?

In the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, UN member states pledged to ensure that no one will be left behind and to reach the furthest behind first (United Nations, 2015). This commitment recognises that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will not be achieved by 2030 unless the most socially and economically excluded and marginalised are put front and centre of planning and implementation. This chapter explores: who the most vulnerable are and therefore priorities for intervention, the extent to which programmes are reaching the most vulnerable, and good practice in identifying, targeting and reaching them.

Who is most at risk of undernutrition?

Poverty amplifies the risk of, and risks from, malnutrition. People who are poor are more likely to be affected by different forms of malnutrition. Malnutrition increases health care costs, reduces productivity and slows economic growth, perpetuating a cycle of poverty, ill health and undernutrition. The people most at risk are those that are most exposed to the immediate and underlying causes of undernutrition:

- illness and disability

- food and income insecurity (inability to produce or purchase food of adequate nutritional quality)

- low awareness of adequate child feeding and caregiving practices

- persistently poor access to adequate basic services (social protection, health, water, sanitation, education etc).

These underlying characteristics of the most vulnerable are themselves influenced by factors like discrimination, poor governance, geography (such as remoteness), access to natural resources and exposure to shocks, conflict and fragility.

Infants, young children and women of childbearing age are most vulnerable to undernutrition. Their bodies have a greater need for nutrients, such as vitamins and minerals, and are more susceptible to the harmful consequences of deficiencies.

Children are at the highest risk of dying from wasting. They become undernourished faster than adults. Severely wasted children are 11 times more likely to die than those with a healthy weight. Undernourished children catch infections more easily and have a harder time recovering because their immune systems are impaired. Many infant and young child deaths in low- and middle-income countries are attributable to the poor nutritional status of their mothers (WHO, 2020).

In households where food security is precarious, women are often more vulnerable than men to malnutrition because of their different physiological requirements and because of power relationships within the household (often men claim more and better food than women). In most cases, a woman requires a higher intake of vitamins and minerals in proportion to total dietary intake than a man. When women are pregnant or lactating, their foods need to be even richer in energy and nutrients.[1] Teenage mothers and their babies are particularly vulnerable to malnutrition. Girls generally grow in height and weight until the age of 18, and do not achieve peak bone mass until about 25 years old. The diet of a chronically hungry adolescent girl cannot adequately support both her own growth and that of her foetus. Malnourished young women often give birth to underweight babies (FAO, 2000, p. 11).

The 2008 Lancet Series on maternal and child nutrition identified the need to focus on the period of pregnancy and the first two years of life (the 1,000 days from conception to a child’s second birthday, during which good nutrition and healthy growth have lasting benefits throughout life). Undernutrition experienced before the age of two causes irreversible damage for future development towards adulthood (Horton, 2008, p. 179).

As the bearers and carers of children, women’s health and economic potential is entwined with that of future generations. Unless girls grow well in early childhood and adolescence and enter into motherhood well nourished, are lent support during pregnancy, protected from heavy physical labour and empowered to breastfeed and provide good food for their babies and toddlers, the intergenerational cycle of undernutrition will not be broken (Black et al., 2013, p. 443).

Nutrition interventions therefore often target the following groups of women and children:

- women of childbearing age, including adolescent girls (15 to 49 years old)

- pregnant and lactating women and girls

- new-born babies

- breastfeeding mothers and children under six months

- infants between six and 23 months

- young children between two and five years old.

Implementing agencies also recognise that other vulnerable groups should be considered according to the context and type of intervention, for example people living with HIV and/or tuberculosis, elderly people, people with disabilities, refugees and emergency-affected populations (WFP, 2017, p. 18).

What is the evidence on whether nutrition interventions reach the most vulnerable in practice?

Coverage of essential nutrition actions through health systems is limited. Many of the most vulnerable women, girls and children do not receive the assistance they require. The 2017 Global Nutrition Report provides data on the extent to which essential nutrition actions are reaching the people who need them. For example, it shows that only 5% of children aged between zero and 59 months are receiving zinc treatment (Development Initiatives, 2017, p. 12).

There is a range of factors, internal and external to service delivery systems, that impact on the extent to which the most vulnerable are reached. Internally, they may include lack of analysis of who and where is most at risk of undernutrition, inadequate financial and human resources and a lack of know-how on the part of implementers. Externally, inhibiting factors may include geographical remoteness, a lack of physical infrastructure, including roads, and conflict. Discriminatory attitudes and behaviours among political authorities, service providers and communities on the basis of gender, age, disability, ethnicity, religion etc also lead to the exclusion of vulnerable groups.

What is good practice in identifying the most vulnerable?

Reaching the most vulnerable and ensuring no one is left behind requires context-specific, disaggregated data and analyses of who is most vulnerable, where they live and why they are at risk (Development Initiatives, 2020, p. 11). This information can then inform the planning and targeting of programmes. National nutrition information systems should provide data including:

- Geographical areas most affected by undernutrition (rates of stunting, wasting and micronutrient deficiencies).

- Disaggregated information on the underlying causes of undernutrition.

- Geographical areas most at risk.

- Trends and risk factors, providing early warning of potential increases in undernutrition due to risk factors such as drought and conflict.

- The type of people who are most affected or at risk.

- Times of the year when risk is greatest and when services may need to be scaled up to respond to seasonal variations in risk factors.

Given the multi-sectoral nature of undernutrition, there is a need to draw information from multiple sectors and sources into a common or unified information system. There is no ‘blueprint’ for information systems. Countries need to develop their own unique approaches (SUN Movement Secretariat, 2014). National Information Platforms for Nutrition is an initiative set up by the European Commission, DFID and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to provide support to countries in order to strengthen their information systems for nutrition and improve the analysis of data, so as to better inform strategic decision making. The initiative currently involves Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Ivory Coast, Laos, Niger and Uganda.

Despite this type of capacity-building support, many countries do not yet collect the necessary data. In particular there is a “shocking gap in micronutrient data which needs to be filled as a matter of urgency” (Development Initiatives, 2018, p. 18). In the absence of comprehensive and reliable national multi-sectoral information systems, implementing agencies often need to undertake their own needs and risk assessments, often leading to duplication of efforts.

What is good practice in targeting and reaching the most vulnerable?

For both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions, the first step in reaching the most vulnerable is to target geographical areas with the highest rates of undernutrition and risk factors such as poverty, food insecurity and exposure to shocks, informed by the types of data described in the previous section. This approach is illustrated in the phased implementation of the government of Ethiopia’s Seqota Declaration, which aims to end stunting in children under the age of two by 2030 (Odhiambo et al., 2019, p. 1).

An innovative approach to the prioritisation and targeting of resources is the Optima Nutrition tool (Pearson et al., 2018). Optima Nutrition has been applied to countries in Asia, the Pacific and Africa to address national and sub-national policy and programming questions. The purpose of the tool is to provide practical advice to governments to assist with the allocation of current or projected budgets across nutrition programmes, on the basis of data from national information systems. It enables the targeting of geographical areas that are the most vulnerable to undernutrition. It also supports decision making on priority interventions under different funding scenarios, in order to maximise impact on the nutrition of the most vulnerable groups.

Targeting nutrition-specific interventions through health systems

Nutrition-specific actions (by definition) target the poorest, most vulnerable and marginalised populations (WHO, 2019c, p. 4).Two key ways to improve access to nutrition interventions by women and children most at risk of malnutrition are by minimising the financial cost of accessing services and integrating nutrition interventions into existing health services delivered by community health workers.

The integration of nutrition-specific interventions into universal health coverage[2] has the potential to improve equity by reducing or eliminating health expenditure and other barriers to access nutrition interventions (Government of Japan, 2019). The costs associated with accessing nutrition services can be a major barrier to reaching the most vulnerable. Financial incentives have the potential to promote increased coverage of some but not all child health interventions, but the quality of evidence available is low. The removal of user fees for access to health services appears to be more effective (Bhutta et al., 2013, p. 453).

Bhutta et al. (2013, p. 452) find that community health workers are able to implement many health and nutrition interventions at scale and have substantial potential to improve nutrition outcomes among difficult-to-reach populations through communication and outreach strategies. Much potential exists for scaling up nutrition promotion and therapeutic interventions through such platforms and hence integrating the two at point-of-service delivery. This integration could also help achieve reductions in inequities in the short term. Nutrition services may be integrated with health services such as immunisation and antenatal care. Child health days, during which children under five are targeted for immunisation as appropriate, can also be used to provide vitamin A capsules, deworming treatments, information messages and, in some instances, screening for wasting (UNICEF, 2014, p. 52).

The effectiveness of community-based service delivery depends on the availability of trained community health workers or volunteers, as well as transport and other logistical capacities. There is potential for overload and breakdown of systems that rely on very low-paid or volunteer workers. In many countries, the coverage and effectiveness of community-based services is highly dependent upon NGO support (Bhutta et al., 2010, p. 13). As highlighted in Section 3.3, nutrition-specific interventions can also be integrated with nutrition-sensitive programmes which are targeting the most vulnerable.

Targeting of nutrition-sensitive interventions

In the 2013 Lancet Series, it was considered that a three-stage process is most effective in targeting nutrition-sensitive programmes (Ruel and Alderman, 2013, p. 12): geographic targeting on the basis of poverty and food insecurity, community-based identification of the poorest and most vulnerable households, and finally identifying poor households with women of childbearing age and young children.

More recent evidence suggests that it is more realistic to include geographical areas most at risk of undernutrition as targets for nutrition-sensitive programmes and then ensure that poor households with limited access to essential health, WASH and livelihood extension services are targeted – not necessarily households with women of childbearing age and young children (Ruel, 2019, p. 100). This is in recognition of the fact that nutrition-sensitive interventions address underlying causes, but have limited direct impact on nutritional status.

Registration systems for social protection programmes targeting the poorest and most food-insecure people can provide a common source of data to inform the targeting of a range of different programmes, including nutrition programmes. This is the intention behind the establishment of the Single Registry System in Kenya, for example (Government of Kenya, 2020). In most contexts such information systems do not yet exist, though, and there is a widespread reliance on community-based targeting methodologies which have been found to be effective in identifying people most in need of assistance, including disabled people (McCord, 2017, p. 8). However, community-based targeting approaches do need to take account of possible ‘elite capture’ and discrimination against certain types of household and individuals, and are likely to perform less well in communities where there are low levels of social integration. There is therefore often a need for independent verification of samples of community-identified households and individuals and the establishment of complaints mechanisms, accompanied by strong community sensitisation.

What is good practice in measuring results?

This chapter reviews practice in measuring the results of nutrition programmes and actions. Before focusing on measuring results, the chapter first discusses how information on results is used to inform learning and accountability. After all, results data is only useful if it informs improved nutrition practice and impacts (Wongtschowski, Oonk and Mur, 2016, p. 2).

National nutrition learning and accountability mechanisms

There is a need for mutual accountability at national and sub-national levels between the different actors who are responsible for enabling sustainable reductions in undernutrition, as well as between those actors and the broader public. Mutual accountability is: “a process by which two (or multiple) partners agree to be held responsible for the commitments that they have voluntarily made to each other. It relies on trust and partnership around shared agendas, rather than on ‘hard’ sanctions for non-compliance, to encourage the behaviour change needed to meet commitments. It is supported by evidence that is collected and shared among all partners” (OECD, 2008, p. 1). Accountability processes need to be supported by monitoring and evaluation systems which provide disaggregated data on programme performance and results.

In some countries, high-level multi-stakeholder platforms (ie ministerial and heads of agency levels) responsible for the development of multi-sectoral nutrition policies, strategies and resource mobilisation are the forums where mutual accountability takes place. These high-level platforms utilise monitoring, evaluation and learning information to review progress, impacts and the contributions of different actors. However, in other countries, participation in platforms is not at a high enough level to ensure that action is taken on the basis of lessons learnt (Manning et al., 2018, p. 29).

The SUN Movement encourages member countries to undertake Joint Annual Assessments (JAAs) for learning and accountability purposes. These assessments are promoted as opportunities for in-country nutrition stakeholders to come together, reflect on progress and challenges in implementing national multi-sectoral plans, and identify priorities and where support is needed to realise joint goals at country and sub-national levels. The identification of support needs is intended to guide technical and financial assistance provided by donors and other stakeholders. The JAAs also review the contributions of different stakeholder groups (business, civil society, the UN, donors and academia) towards collective progress – for example see the Bangladesh nutrition multi-stakeholder platform JAA (2019) for analysis of the contributions of donor agencies.

The JAAs are considered to be valuable learning and accountability processes when they are transparent and inclusive of all stakeholders, and provide the opportunity to scrutinise evidence on progress, strengths and weaknesses, and revise plans and service delivery systems on the basis of lessons learnt. However, it is reported that these exercises frequently do not meet these criteria and there is often a desire by national governments to paint a ‘rose-tinted’ picture (Manning et al., 2018, p. 26).

Although learning and accountability should be compatible, there are often tensions between the two. In accountability processes, there may be a reluctance to acknowledge weaknesses and failures to achieve results if there is fear of negative consequences arising through these processes (Wongtschowski, Oonk and Mur, 2016, p. 4). For accountability to be useful there is a need to introduce a culture of learning into the process, where weaknesses and failures are acceptable as long as actions are well intentioned and there is demonstrable willingness to improve future practices (Adams, 2007, p. 12). Key elements of effective accountability mechanisms are reciprocal trust, government leadership, credible incentives and integration into national systems and processes (OECD, 2008, p. 4).

Monitoring and evaluation systems for nutrition

The monitoring of programme implementation, results and impact in relation to national multi-sectoral nutrition plans should be led by national governments. Ideally, there should be one national nutrition monitoring and evaluation system incorporated into a wider, unified national nutrition information system (Bezanson and Isenman, 2010) which measures the results of multi-sectoral, multi-stakeholder actions for nutrition, such as the Government of Kenya National Nutrition Monitoring and Evaluation Framework (Kenya Ministry of Health, 2013).

The SUN Movement has developed a Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning (MEAL) system intended to measure results in sustainably reducing undernutrition in member countries. The results are summarised and presented in country dashboards which contain information in relation to a set of 79 indicators covering the eight domains of the SUN Movement theory of change. Information in the dashboards is summarised in country profiles in the SUN Movement annual reports (SUN Movement Secretariat, 2019).

Data relating to the indicators comes from multiple sources, such as the WHO, UNICEF and the Global SDG Indicators Database, as well as from the SUN Joint Assessment, SUN Movement Secretariat, Nutrition International Technical Assistance for Nutrition project and Maximising the Quality of Scaling Up Nutrition Plus. In particular, data comes from national surveys carried out by national government agencies, often together with Demographic and Health Surveys or UNICEF Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys and possibly other data collection systems.

There are reported tensions between national and the SUN Movement systems, as countries may not always have the data requested on the global level and may have to spend extra time collecting additional information and feeding data into a system structured in a different way to their own. Moreover, it is difficult to discern progress in relation to nutrition outcomes from the SUN data as trends are not shown.

Monitoring and evaluation systems need to consider the following types of results: