Assessing the Impact of the Scale-up of DFID’s Support to Fragile States

Executive Summary

The UK Government has committed to spending 30% of Official Development Assistance (ODA) in fragile states by 2014-15, an increase from £1.8 billion of bilateral ODA (2011-12) to £3.4 billion (2014-15). This review looks at how DFID has taken this forward, to assess whether it will achieve impact for intended beneficiaries.

Green: The programme performs well overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Some improvements are needed.

Green-Amber: The programme performs relatively well overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Improvements should be made.

Amber-Red: The programme performs relatively poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Significant improvements should be made.

Red: The programme performs poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Immediate and major changes need to be made.

Overall

Assessment: Amber-Red

DFID has increased its focus on fragile states – countries which are prone to some of the highest levels of poverty, have intractably weak systems and create wider security challenges. This important ‘scale-up’ decision originated with the 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review and was part of a cross-government agenda. The targeted volume of expenditure and the planned pace of the increases was out of step with the capacity of DFID, its partners and, most importantly, the countries themselves to deliver. It has taken DFID four years for scale-up to start to deliver impact. Transformative impact in fragile states will take a generation to achieve and is dependent upon development of in-country state capacity. This was insufficiently recognised at the start of scaling up, where increased funding was directly linked to assumed greater impact.

The experience of scale-up in fragile states provides lessons for future policy initiatives. The focus needs to be on spending well (and not just more) and on ensuring that absorptive capacity preconditions are in place, if enhanced expenditure is to have the optimum impact.

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

DFID has responded to the real needs and under-resourcing of fragile states with a scale-up of funding. Although the rationale was clear, the strategy was insufficiently developed. The process for determining scale-up created focus on what could be delivered rapidly and measured quantitatively. Initial targets and timescales were not realistic, however, given the fragile states context and, as a result, expenditure targets have since been revised downwards. Country offices are working hard to deliver and new corporate-level policies are being introduced to support this. UK Government departments work together well in fragile states.

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

At a bilateral level, DFID has become an organisation specialising in fragile states. Over time, it has made improvements to systems and processes to deliver scaled-up funds in a fragile state environment, many of which were not suitable when scale-up started. Positive changes include diversification of delivery partners and better management of fiduciary risk. There is an appropriate appetite for risk-taking at country office level to push boundaries; this should be more explicitly defined at corporate level. Inclusion of targeted infrastructure components in development projects has been successful and should be used more strategically.

Impact

Assessment: Amber-Red

Transformative impact in fragile states will take many years to achieve and it is important that a realistic bar for success be set. Scaled-up funding, more coherent programming and increased focus on results have brought some influence and leverage at country level. Many programmes in our case-study countries are achieving specific planned results. There are, however, real challenges with sustainability of impact, rolling out pilot approaches and embedding them in locally-owned systems. At country level, more needs to be done, both to define the critical path from fragility and to track the effectiveness of the building blocks to be delivered by individual interventions. In many cases, there is limited evidence that trajectories are convincingly positive and will add up to reduction in fragility at a country level. It is not clear that the scale-up in funding is yet matched by an increased impact on overall fragility.

Learning

Assessment: Green-Amber

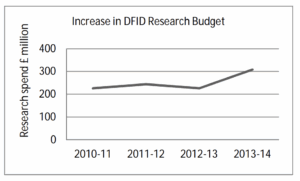

At country level, there is good, innovative learning practice supporting both effective design of new, and redesign of older, programmes. At the start of scale-up, DFID had limited learning to guide programme choices. DFID now has an impressive fragile states research agenda, to build evidence in key areas such as state-building and political settlements. Learning in fragile states is driven at the country level by individuals; central learning processes and incentives for learning remain less strong.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: DFID needs to develop fresh coherent guidance on working in fragile states, drawing on adaptations developed at country level, new research and learning and the evolved systems being developed in DFID centrally.

Recommendation 2: DFID should ensure that country-level targets realistically reflect the challenges of scaling up and the longer-term timescales needed for lasting impact in fragile states and calibrate funding accordingly. The targets should reflect the entire country portfolio, taking account of small as well as large programming through qualitative and quantitative targets.

Recommendation 3: DFID needs to provide guidance on the inclusion of targeted infrastructure components in development programmes to enhance sustainable impact in fragile states programming.

Recommendation 4: DFID needs to define its appetite for risk in fragile environments: there needs to be explicit alignment between the centre and the field about potential for failure and its consequences.

Recommendation 5: DFID should leverage its learning about operating in fragile states and take a clearer global leadership role with the international community to advance thinking on effective approaches.

1 Introduction

Introduction

1.1 The UK Government has committed to spending 30% of Official Development Assistance (ODA) to support fragile and conflict-affected states (collectively referred to henceforth as ‘fragile states’) by 2014-15.1 DFID’s current approach to measuring this target excludes multilateral expenditure and expenditure through centrally managed programmes. As a result, DFID’s overall spending in fragile states is likely to be much higher than 30%. In 2010-11, £1.8 billion of bilateral ODA was spent in fragile states. By 2014-15, that will have risen to £3.4 billion.2 This review assesses how well DFID – which contributes the majority of this funding – has implemented this commitment and whether the resulting increased expenditure in fragile states is achieving impact for intended beneficiaries.

The context of fragile states

What is a fragile state?

1.2 There is no single definition of a fragile state. DFID’s working definition of fragile states is ‘countries where the government cannot or will not deliver core state functions to the majority of its people, including the poor’.3 DFID’s list of fragile states draws on three different indices: the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment;4 the Failed States Index of the Fund for Peace;5 and the Uppsala Conflict Database.6 Annex A1 contains a map and tables setting out the 55 states categorised by DFID as fragile and identifying the 21 of these which are also included on its list of 28 priority countries, following the Bilateral Aid Review (BAR) in 2010.7

1.3 DFID’s list of fragile states covers a wide range of very different countries, including:

- middle-income countries, such as the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Indonesia;

- countries on the verge of graduating to stable developing states, for example Sierra Leone before the Ebola crisis took hold (when the fieldwork for this review was undertaken);

- countries that are fragile in some regions only, such as Ethiopia; and

- countries in actual conflict, in particular fragile states with asymmetric conflict.8

1.4 Other donors and international organisations use different definitions. As a result, there are several different lists of countries that are defined as fragile and conflict-affected.

Why is providing development assistance to fragile states important?

1.5 DFID stated in 2011 that ‘work to prevent and respond to conflict and fragility saves lives and reduces human suffering, it is essential for poverty reduction and progress against the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and it can help to address threats to global and regional stability’.9 It is unlikely to be possible to end extreme poverty without a concerted focus on fragile states:

- out of the seven countries unlikely to meet any MDGs by the 2015 deadline, six are fragile states;

- the eight most aid-dependent countries in the world are fragile states;10 and

- one third of the poor currently live in fragile states. By 2018, that share is likely to be a half and, by 2030, nearly two-thirds.11

1.6 In addition, fragility matters because of the risk it poses to regional and global stability. Many fragile states are conflict or immediate post-conflict states. Addressing fragility is considered to be important for international and UK security objectives. In 2011, the then Secretary of State told the International Development Committee (IDC) that ‘the Government was committed to working in fragile and conflict-affected states because it was the right thing to do, and because it was in our national interest’.12

Women and girls are particularly affected by fragility

1.7 Women and girls are badly affected by fragility.13 In fragile states, factors such as a lack of access to basic services, a lack of access to justice and physical insecurity – all of which marginalise, discriminate against and impoverish women – can be particularly marked.

1.8 Weak state-society relations are found in most fragile states. As a result, many people in fragile states turn to traditional, religious and customary law, which can further disadvantage women.14 There is also an increased risk of gender-based violence in fragile states.15

Why is working in fragile states different?

1.9 Working in fragile states requires a different approach to development. Donors have to deal with a number of difficult issues which are specific to – or magnified in – fragile states, including:

- there is a constantly changing and unpredictable political context;

- the state is unable or unwilling to deliver basic services to citizens;

- it may not be possible to disburse funding through government systems;

- there is a limited range of implementing partners;

- access is difficult, especially to conflict-affected areas;

- measuring progress is difficult and things can get worse before they get better; and

- humanitarian requirements are recurrent.

1.10 A fundamental principle of work in fragile states is to ‘Do No Harm’.16 Although this is an issue in all areas of development, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) recognises that the risk of doing harm – that is, creating unintended consequences or inadvertently making matters worse by, for example, creating divisions in society and worsening corruption and abuse – is particularly high in fragile states.17,18

The UK’s approach to the international challenge of fragile states

1.11 Work in fragile states has always been a key part of DFID’s overall portfolio. DFID’s current focus on fragile states is the product of a number of UK Government and international policy decisions.

1.12 The BAR in 2010 reduced the number of DFID priority countries from 43 to 28, of which 21 are considered to be fragile (see Annex A1). In parallel, the Strategic Defence and Security Review led to the 2010 commitment to spend 30% of UK ODA ‘to support fragile and conflict-affected states and tackle the drivers of instability’.19 This decision was significantly influenced by security considerations, as well as by development needs. The then Secretary of State defended the decision, commenting that ‘this is not a case of DFID being coerced to use its aid programmes to meet others’ objectives’.20

1.13 In 2010, DFID introduced a Practice Paper on working in fragile states. Building Peaceful States and Societies outlined a new, integrated approach, which put state-building and peace-building at the centre of work in fragile and conflict-affected countries.21 This practice paper predated the process and experience of scaling up and has not been revised since 2010.

1.14 On the international front, DFID took a lead in discussions which led to the 2011 Busan New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States.22 The UK Government has endorsed this agreement, along with over 40 other countries and international organisations. It is now being piloted in a range of fragile states.23

1.15 The Busan New Deal sets out five goals for peace-building and state-building: legitimate politics; security; justice; economic foundations; and revenue and services. It undertakes to support inclusive country-led and country-owned programming and commits donors to ‘doing things differently’: risk management that is better tailored to fragile contexts; timely and predictable aid; and building critical local capacities.

1.16 In 2011, the World Bank released the World Development Report: Conflict, Security, and Development.24 This highly influential report draws on experience from around the world to offer ideas and practical recommendations on how to move beyond conflict and fragility and secure development.

1.17 In early 2012, the IDC published its report on Working Effectively in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States: Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda.25 The report questioned the rationale for DFID’s patterns of spending in conflict-affected states and highlighted the lack of clarity about how priority countries had been identified. It also drew attention to the value for money and corruption risks of working in fragile states.

The UK has made major financial commitments to fragile states

DFID will meet its 30% target in 2014-15

1.18 The commitment to increase the proportion of money directed to fragile states to 30%, when added to the BAR (which resulted in 75% of DFID priority countries being fragile states), has transformed DFID’s bilateral programming to focus on fragile states. DFID’s planned bilateral expenditure in fragile states in 2014-15 is £3.4 billion, out of its overall budget of £10.3 billion. In 2014-15, therefore, DFID is expected to reach the target of spending 30% of its budget in fragile states, even without the contribution of other government departments, which contributed around 17% of total ODA (£1.96 billion) in 2012-13.26

1.19 DFID calculates its expenditure in fragile states using only bilateral ODA figures. It has decided not to attempt to quantify the amount of aid expenditure in fragile states which is channelled through multilateral funds. This means that the total actually spent in fragile states – taking bilateral and multilateral expenditure together – is currently unclear. The way in which expenditure in fragile states is calculated, however, results in DFID spending more in fragile states than the target set (see Figure 1 on page 5).

1.20 In 2013, the UK Government reached its objective to invest 0.7% of Gross National Income through ODA.27 As a result, aid expenditure levels in future are unlikely to increase significantly and may well fluctuate. Medium- and long-term financial planning may be more difficult and DFID will have to manage changes in country-level budgets.

DFID’s scale-up in fragile states should be seen in the wider UK and international contexts

1.21 DFID’s scale-up decisions came at a time when OECD figures indicated that the overall level of international aid to fragile states was falling,29 although funding to fragile states has increased again since 2013:30

- since peaking in 2005, the international volume of aid to fragile states followed an erratic but downward trend until 2012;

- global ODA to fragile states fell by 2.4% in 2011, at the point where DFID’s scale-up was starting;

- aid to fragile states is volatile, shooting up by 25% from 2011 to 2012 and then decreasing by 4% from 2012 to 2013. Surges of support to a small number of states with global security implications drive this volatility;31 and

- political and economic pressures over the past four years have led to refocussing and reduction in fragile states expenditure by a number of bilateral donors, including Canada (one of the ten largest donors before 2010).

1.22 DFID has, as a result of the scale-up decision, effectively become a specialist organisation for fragile states at the bilateral level. At the same time, DFID’s commitment to fragile states has to be balanced against other spending commitments. For example, in January 2014, the Secretary of State announced that DFID would spend £1.8 billion on economic development by 2015-16,32 more than doubling the amount spent in 2012-13.

Our approach and methodology

1.23 For this review, we:

- examined the strategy and allocation process for scaled-up funds;

- reviewed the capability of both DFID and the delivery chain to absorb these funds; and

- assessed the quality and impact of programming of the funds.

1.24 We reviewed overall policies, guidance and processes for scale-up and delivery in fragile states with DFID at a corporate level. There are critical central areas of responsibility, such as influencing international partners (both multilaterals and through major initiatives such as the Busan New Deal) and cross-Whitehall work on fragile and conflict states. We met with a range of DFID central staff responsible for policy and guidance on fragile states in order to understand their overarching strategy, desired impact and the success of scale-up in fragile states. We explored how systems and processes have changed and met with key stakeholders in other government departments to understand the issues, challenges and new approaches in working with DFID in fragile states.

1.25 We reviewed scale-up in six countries. Country case studies were drawn from those receiving the most significant increases in funding, although we attempted to avoid countries which have already received several ICAI reviews. Four of the six countries (Pakistan, Nepal, Sierra Leone and Yemen) were the subject of a desk review.

1.26 We made field visits to two countries, Somalia (including the office base in Kenya) and DRC:

- Somalia has experienced almost constant conflict since 1991 and faces major issues of fragility, with the militant group Al-Shabaab dominating rural areas in South Central Somalia. Somalia’s population of 10.5 million is highly vulnerable and famine recurs on a regular basis; and

- DRC has a population of 79 million. Although no longer formally subject to civil war, conflict continues at local, regional and national levels. The UK is a relatively new player in this French-speaking country and is now one of the largest donors, spending over £150 million in 2014-15.33

1.27 In reviewing Somalia, we spent time in Nairobi – DFID’s main base – and travelled to Hargeisa (Somaliland) and Mogadishu. In DRC, apart from visiting the DFID office in Kinshasa, we travelled to the provinces of Kasai Occidentale in the South and North Kivu in the East. We reviewed overall country portfolios and 11 programmes across the two countries. These are described in Figure 2 opposite and Figure 3 on page 7. Further details can be found in Annex A4.

Listening to intended beneficiaries was important to our work

1.28 To ensure that we reached a sufficiently broad sample of stakeholders and intended beneficiaries and to capture the diversity of views, we contracted a team of regional and local consultants to undertake follow-up focus groups with key beneficiary groups in Somalia and DRC. The results of this beneficiary work are presented in Annex A5.

1.29 The main purpose of the focus groups was to ask beneficiaries about the impact of DFID’s programmes. Consultants also interviewed key informants to identify how programmes contribute to state-building and how these interact with the root causes of instability and fragility.

1.30 Capturing the perspective of beneficiaries is an important part of our methodology, as it enables us to triangulate evidence from other stakeholders (DFID, implementing partners and country partners). Feedback from beneficiaries is fed into our assessment matrices, to ensure that we consider all evidence to identify consistent perspectives.

Somaliland Development Fund. This is a £25 million programme, jointly funded by DFID, Denmark and Norway (the Netherlands are also in the process of joining), to deliver a portfolio of high-priority infrastructure investments across a range of sectors, aligned to government priorities. We refer to it as Somaliland Development Fund.

Health. We reviewed the £38 million Health Sector Consortium and the £31.5 million Joint Health and Nutrition Programme. Health Sector Consortium is focussed on helping regional health authorities to implement essential health services, with a priority on family planning and maternal and child health. The Joint Health and Nutrition Programme is a pooled fund delivered by United Nations (UN) agencies. It aims to support sustained and improved reproductive, maternal and child health and nutrition outcomes for Somali women and children. We refer to these programmes as Health Consortium Somalia and JHNP Somalia.

Multi-year Humanitarian Programme. This £145 million programme has an emphasis on resilience: helping people to address food needs through different forms of agriculture. Its internal risk facility of £40 million over four years gives the Head of Office authority to approve up to £10 million each year, on the basis of early warning triggers and thresholds that have been surpassed. We refer to it as Somalia Humanitarian.

Supporting peace and stability in Eastern DRC. The objective of this programme is to promote peace and stability in Eastern DRC, with funds of up to £80 million. No DFID funds had been disbursed at the time of our field visit. Since then, an initial portfolio has been finalised and £1.6 million has been disbursed. It will support national, multilateral and bilateral efforts to end conflict and build lasting peace. We refer to it as Supporting Peace in DRC.

Accès aux soins de santé primaires. This £180 million programme started in 2012. It supports 56 health zones (out of 515) in DRC, to provide at least six million people with access to essential primary and secondary healthcare services.34 We refer to this programme as DRC Primary Healthcare.

Security Sector Accountability & Police Reform Programme. This is a £61 million, five-year programme to promote accountability of the security and justice sector and to support national police reforms to improve security and rule of law. We refer to it as DRC Police Reform.35

Tuungane Community Driven Reconstruction. This £106 million programme, mainly in Eastern DRC, empowers rural communities to have a greater voice and help them to become active agents of their own development. We refer to it as DRC Tuungane.

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. A number of programme elements come under the £159 million Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) umbrella in DRC. We reviewed ‘Villages et Ecoles Assainis’, which is implemented by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the Urban WASH programmes implemented by Mercy Corps. The former is a national programme which focusses on areas such as drinking water, waste disposal, household waste, cooking habits and general hygiene (including hand washing). The Urban WASH programme is based in Goma and focusses on water infrastructure, improved management and behaviour change. We refer to the two programmes we reviewed as DRC UNICEF WASH and DRC Urban WASH.

2 Findings: Objectives

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.1 In this section, we review how the overall strategy for scaling up in fragile states was put into effect at the country level. We also assess the central policies for scale-up in fragile states and how cross-Whitehall work on fragile states is evolving. We explore new DFID approaches in fragile states and we examine whether the decision to scale up aid in fragile states was based on sound and coherent allocation processes that reflected specific country contexts and the needs of intended beneficiaries.

The ‘results offer’ process distorted planning for scale-up

2.2 Scaled-up resources were allocated to country offices through a new process introduced in 2010 by the BAR. This process aimed to produce a clear rationale for country allocations and spending priorities.36 Country offices were asked to set out the results that could be realistically achieved in their country over the four-year period from April 2011 to March 2015.

2.3 From July to September 2010, country offices developed these bids for scaled-up resources. Indicative budgets were agreed in December 2010 and implementation of the spending plans started in April and May 2011.

2.4 Country offices worked through the bidding process without major changes to guidance on working practices. There was limited clarification of the changes to systems needed to make DFID more fit for purpose as a specialist agency for delivering aid in fragile states. As timescales for the development of bids were short (around six weeks), analysis was often limited. This also led to a high degree of dependence on expanding existing programmes, rather than breaking new ground.

2.5 The process was competitive and some country management teams have admitted that the focus on large and quantifiable results encouraged overbidding. There was insufficient focus on what was feasible, taking into account the capacity of the relevant government and the available delivery mechanisms.

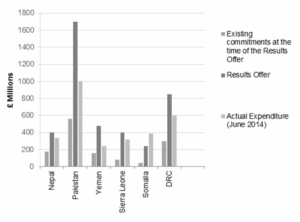

2.6 The bids for our case study countries varied in scale, both in absolute and relative terms. This is set out in Figure 4 on page 9. More details can be found in Annexes A2 and A3. The numbers were very large. For example, the Pakistan bid amounted to an additional £1.7 billion – a 300% increase from 2011-12 to 2014-15. Over the same period, Sierra Leone’s scale-up amounted to an increase of 476% over existing commitments.

Over-ambitious plans have since been revised to be more realistic and flexible

Expenditure targets have been revised downwards

2.7 Scale-up plans at country level were unrealistic. By the time most Operational Plans, containing the final agreed ‘results offer’ amount signed off by the Secretary of State, were finalised in 2011, they had been revised down from the initial bids. These were further revised down in 2013. In a number of cases, results targets have similarly since been revised downwards. Figure 4 on page 9 demonstrates the level of reduction of expenditure targets: Pakistan and Nepal revised targets downwards by 18% and 23% respectively in 2011 and Pakistan revised targets downwards again in 2013 because of operational challenges. In DRC, the then Secretary of State halted the scale-up in 2012, following a visit to the country and a review of the programme. DRC expenditure targets were revised upwards in 2013, following a review by the new Secretary of State. Yemen significantly revised downwards its scale-up plans following the events of the Arab Spring in 2011. Only Somalia’s spending targets have increased. This is the result of a later start to implementation – given the famine in 2010-11 – and the decision to include humanitarian expenditure in the totals, which was not in the original results offer.

2.8 The country offices in our case studies are now likely to meet their expenditure targets but only because these, and in some cases consequent results targets, have been revised downwards (and in some cases the timescales to meet those targets have been extended by an additional year). The original results offer exercise may have been flawed due to the competitive nature of the bidding process and its timescales, but we do recognise that DFID has since shown greater realism in adapting plans and funding to circumstances.

Figure 4: Scale-up ambitions – and the reality

2.9 Planning and programming in fragile states will always need to be a dynamic and responsive process. External factors will continually require DFID to revise and change its plans.

2.10 We saw this in our case study countries (further details can be found in Annexes A2 and A3):

- Yemen’s original bid and agreed results offer were effectively made obsolete by unforeseen political events during the 2011 Arab Spring. As a result, the Yemen Operational Plan, finalised in 2012, was based on a new set of assumptions, with a lower level of expenditure and a stronger focus on humanitarian assistance; and

- scale-up in Somalia was delayed by the 2010-11 famine, the severity of which was only becoming apparent during the results offer process.

Country offices recognise the importance of flexible programming in fragile states

2.11 Scaling up brings internal pressures towards fewer, bigger programmes. The unpredictability of fragile states, however, as well as the need to work experimentally – given that the body of research on what works in fragile states is still developing – requires smaller, more reactive or opportunistic programming or greater inbuilt flexibility. For example, DFID Nepal has used the Enabling State Programme for small-scale engagement in new areas, some of which (including right to information, public financial management and violence against women) have been expanded. There is a risk, however, that a ‘flexible’ programme can become an unstructured ‘umbrella’ programme, with no coherent strategy or with goals so general that it is impossible to identify impact or roll out on a wider scale. The business case for the Supporting Peace in DRC programme, for example, promotes it as a ‘flexible, responsive funding instrument that incentivises synergy and enables multi-faceted approaches and adaptation’. DFID’s Quality Assurance Unit questioned the broad scope of the portfolio and how decisions to stop components showing poor results or to scale up others which were producing good results would be made.38 Our review echoes these concerns.

2.12 DFID’s recently introduced Country Poverty Reduction Diagnostic (CPRD) tool is intended to help country offices to analyse the context in which programming choices are made and to enhance portfolio coherence. It could help country offices to design appropriate and achievable programmes.

2.13 We believe that the CPRD is a step forward but, nevertheless, we identified some important gaps in the CPRD process. The CPRDs which we reviewed had a section for looking at longer time horizons, but the primary focus was on the shorter term, whereas development plans in fragile states need to have a 15 to 20 year timeframe. We also noted that the CPRDs which we reviewed were generally focussed on DFID and did not detail partner government priorities, commitments and capability or the work of the wider international community. As such, they may not contribute enough to the important work of partner co-ordination, to identify DFID priorities or ways of increasing impact through synergy.

Programme design needs to be context specific

Approaches to state-building in fragile states must take account of the absorptive capacity of the local context and expectations of beneficiaries

2.14 The traditional approach to development, built on a paradigm of capable, accountable and legitimate states, by definition does not hold in fragile states. Some of DFID’s programmes in fragile states appear to assume that the government is an active and collaborative partner and that a key objective of development programming is to build its capacity.39 This is true in some fragile states but not all. Emerging research suggests that basic service delivery does not always have the potential to contribute to state-building, especially when dealing with states as dysfunctional as Somalia or DRC.40

2.15 In a number of the programmes which we reviewed, in both Somalia and DRC, we observed a ‘missing middle’. We saw programmes that built good accountability systems and linked communities and basic services at the local level. In a number of cases, however, there was no capable or engaged state apparatus (at national, provincial and local levels) with which to connect, above the less formal local level. Beneficiaries of the health reform programmes in Somalia highlighted this problem. In two locations, they commented on the minimal involvement of the government, viewing non-governmental organisations (NGOs), instead, as the sole provider for basic primary healthcare services. The opportunity to build capacity in the state was, therefore, lost. Without engagement by higher-level institutions, the potential for governance programmes to achieve sustainable change is limited. To be scalable and effective in the long term, supporting the development of effective state institutions, in particular at sub-national levels, is necessary.

2.16 We visited DFID’s DRC Tuungane programme and found it to be an example of where conditions are not conducive to linking basic service delivery and state-building (see Figure 5 for more details).

- there was little evidence of improved accountability and empowerment. Although the process has several opportunities for engagement between the communities and the local authorities, these have not been routinely taken up or necessarily resulted in higher degrees of trust and mutual support, in many cases as a result of weaknesses in local government structures and funding;

- despite efforts to involve established community structures to ensure continuity and ownership, sustainability is an issue;

- it was designed with a highly participatory and elaborate process, through which villagers select projects in a fair and transparent manner and about which beneficiaries spoke positively. The focus on achieving quantitative targets, however, led to short-term programme interventions and DRC Tuungane was more focussed on delivering ‘assets’ to communities than on local governance transformation; and

- a school had been built through the DRC Tuungane programme but was not delivering the expected impact because the teaching staff, who were supposed to be funded by the local government, were not being paid. Our beneficiary survey highlighted instances where poor quality infrastructure had been built.

2.17 It was not clear to us that DFID takes sufficient account of the views of community beneficiaries when designing programmes. We believe that this is particularly important in fragile states, as beneficiaries may have very different ideas about what they expect the state to deliver. Further evidence is provided in Annex A5. By way of example, our field work and our beneficiary research showed that:

- Somaliland Development Fund is well aligned with government priorities but we saw less evidence that the process for selecting projects for investment took account of beneficiary priorities. Ministers were viewed as proxies for their citizens and there was a high focus on gaining their buy-in, as opposed to that of their constituents;

- although DRC Police Reform has set up community consultation ‘Forums de Quartier’, which have been used to shape and refine programme delivery, the ultimate community beneficiaries told us that they had merely been informed of the programme, after it had already been designed; and

- community beneficiaries of the DRC Primary Healthcare programme have strong and nuanced views on the issues faced by the health sector, as well as areas of current effective service provision, which could have enhanced programme design.42

The Busan New Deal sets out key principles but there are differences in expectations between DFID and country partners

2.18 Somalia and Sierra Leone are Busan New Deal pilots and DRC is to become one. The New Deal provides a framework to incentivise the partner government to improve systems and accountability.43 DFID country offices can make good use of these incentives in programme development. We noted, however, that although DFID’s Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department (CHASE) has been providing support to countries with New Deal pilots, there is no formal guidance collated, considered and disseminated to country offices from the centre on how to navigate New Deal issues in fragile states.

2.19 We also noted a misalignment of expectations in relation to the New Deal. Partner governments, for example in Somalia, believe that the New Deal implies a rapid shift to general budget support. The UN system assumes that it means a shift from targeted DFID programming to un-earmarked, UN-administered trust fund mechanisms. To DFID, the New Deal is a ‘how’ – a support to transparent partnership working; to the partner government, the New Deal is a ‘what’ – a shift to budgetary aid. There is a tension created by the New Deal’s emphasis on partner government institutions for delivery in the very places where their capacity is weakest. The implementation of the New Deal will need to take this into account.

Humanitarian and development programming cannot be separated or traded-off in fragile states

2.20 We saw some operational plans in fragile states which were based on an assumption that, as development expenditure increases, humanitarian requirements will diminish. The reality, however, is that humanitarian needs do not disappear in the short – or even the medium – term in fragile states. We would, therefore, question efforts to trade off humanitarian spending with development in DFID’s planning assumptions.

2.21 Humanitarian assistance and Poverty, Hunger and Vulnerability programming constitute 80% of DFID Yemen’s portfolio, for example. Any theory of change that suggests humanitarian requirements in Yemen will reduce in a three- to five-year horizon is unrealistic. In our view, building resilience, through multi-year flexible funding, along the lines of the recommendations in our review of the UK Humanitarian Emergency Response in the Horn of Africa44 and our review of DFID’s Humanitarian Response to Typhoon Haiyan,45 is the right approach.

2.22 We observed new and positive thinking initiated by DFID Somalia around a multi-year humanitarian programme, incorporating both resilience and rapid response (see Figure 6). We note that other countries, including Yemen and Pakistan, are adopting similar approaches.

The programme’s internal risk facility allows the Head of Office to approve up to £10 million each year over the four years of the programme, which can save three to four months in mobilising resources at early warning points. There is a large and structured research and third party monitoring component. This adds cost but, in a context where there is limited knowledge and few answers, it is designed to pay for itself by targeting and improving programming and adding to DFID’s learning of what works in fragile states.

Country portfolios have changed considerably

2.23 In DRC, Sierra Leone and Pakistan, DFID country offices took the scale-up opportunity to engage more broadly across sectors and now manage a broad and diversified portfolio. Sierra Leone took on a substantial new commitment in education and all three countries enlarged commitments in wealth creation and governance and security.

2.24 In contrast, DFID Somalia decided to withdraw from the education sector. Although it is right that DFID is not trying to address every issue in every sector, it nevertheless needs to make sure that the system as a whole is covering critical issues and gaps. Although there are now plans developed for European Union (EU) interventions in South Central Somalia, as well as the existing EU programmes in Somaliland and Puntland, the mobilisation has been slow and will start from 2015. This has left a key aspect of development in Somalia relatively untouched, despite its importance, which was stressed to us in our meetings with, for example, the Prime Minister’s Office in Mogadishu. There need to be joined-up plans across all key donors with regard to the landscape of support in such states.

2.25 Recent trends in development have been to encourage donors to focus their efforts, thus reducing overlap and the burden of transaction for the partner government. There are, however, good reasons why – in some fragile states – DFID might choose to cover a broader range of sectors. There are often fewer active donors in fragile states and so there is less likelihood of overlap and duplication. In addition, a broad portfolio is likely to give DFID greater access and influence with the partner government, in particular as a result of competent sectoral advisors.

There are tensions between central programmes and bilateral country programmes

2.26 Tensions have been created as a result of the increase of resources to devolved country offices, at the same time as DFID is launching big programmes operating in the same countries from the centre. Good communication between country offices and centrally managed programmes is important to ensure coherence and alignment, to share lessons and to supplement oversight from DFID headquarters. We saw little evidence of systems to inform country office teams routinely about central programme plans, decisions and progress on delivery.

2.27 As noted in paragraph 2.24, DFID Somalia decided to exit the education sector. A further issue emerged when, shortly afterwards, the centrally managed Girls Education Challenge Fund instigated substantial programming in Somalia.46 As DFID Somalia no longer has an education advisor, having agreed that the EU would take responsibility for this sector, it has proved difficult to monitor or build influence through the programme.

2.28 This issue has now been recognised at the centre. Tensions between centrally managed and country programmes may be addressed by the new protocols for co-ordination and communication that have been recently developed at the corporate level.47

Infrastructure is an important element in fragile states programming

2.29 Research commissioned by DFID shows that infrastructure needs are important in fragile states.48 Investment in infrastructure can put what is lacking or has been destroyed in place (as we saw in the various health programmes in DRC and Somalia and with DRC Police Reform). It can serve to create community cohesion (as with the DRC urban WASH programme ‘Improved WASH for Goma’s Poor’ or the Somaliland Development Fund), to leverage good governance practices at a community level and to increase the accountability of authorities (as DRC Tuungane did).

2.30 We saw some good examples of infrastructure programming in our case study countries. These included large-scale road construction and water systems in DRC, significant high-priority investments through Somaliland Development Fund and smaller-scale infrastructure integrated into wider programming, such as the construction of police facilities within the DRC Police Reform programme. We also saw poorer practices, where build quality was poor (as in the DRC Tuungane programme), where there was lack of apparent focus on the local-level health centre infrastructure (as in JHNP Somalia, despite the critical importance of this identified by beneficiaries to us) or where there was limited thinking about sustainability and maintenance (as with some aspects of DRC Tuungane and the Somaliland Development Fund).

2.31 We noted that DFID has no clear guidance about how effectively to incorporate targeted infrastructure elements in sector programmes; nor about how to ensure that it is sustainable, involves the community and meets critical beneficiary needs. The research on this topic, noted in paragraph 2.29 above, will be a good starting point for development of such guidance. We note that only 12 of DFID’s 21 fragile states have an infrastructure advisor in country.

The new priority placed on economic development will require careful targeting and scale-up in fragile states

2.32 Economic development programming in fragile states is important and necessary but not easy. Although in some fragile states the private sector can actually function well and provide a point of entry for development, there are many issues to be addressed (including capture by the elite). Beneficiaries of health programmes in both Somalia and DRC spoke convincingly of the need for private sector service provision to be built into programming. If DFID is to engage in economic development work in fragile states, this needs to be conflict sensitive and requires deep contextual analysis. Programming must be flexible and exploratory in its approach. In consequence, economic development programmes in fragile states are likely to be small-scale in the early years.

2.33 Somalia’s new private sector development programmes are small and flexible. We saw franchising in private pharmacies in Hargeisa being used to good effect to deliver key health services and a successful Business Development Challenge Fund. In DRC, we saw a new private sector development programme which is highly flexible and exploratory. Links to upstream conflict prevention, however, in particular the potential of economic development to address youth unemployment, are not fully developed.

2.34 Economic development in fragile states is an important new focus. It is, however, different and complex. DFID’s plans to target £1.8 billion of DFID’s budget in 2015-16 on economic development (more than doubling the amount spent in 2012-13), have – as with the scale-up decision – been framed more in terms of expenditure than on what can realistically be achieved over the medium to long term.49

3 Findings: Delivery

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

3.1 In this section, we examine how delivery approaches and processes have been adjusted as DFID has become a specialist bilateral organisation for fragile states. We assess whether DFID is now fit for purpose to deliver scaled-up funds in a fragile state environment. We also review DFID’s efforts to co-ordinate its work with other government departments.

Interdepartmental co-ordination and cross-government working have been effective

3.2 There is progress with co-ordination in Whitehall. We saw good evidence of effective cross-government working in relation to fragile states, in particular between DFID, the MOD, the FCO, the Home Office, the Stabilisation Unit, the Cabinet Office and the Ministry of Justice. CHASE has led much of this work, along with the International Divisions and other parts of the Middle East, Humanitarian, Conflict and Stabilisation Directorate. Cross-government working between DFID, the FCO and the MOD produced the Building Stability Overseas Strategy in July 2011.50 DFID has worked through the National Security Council (NSC) to facilitate and strengthen UK efforts to prevent and tackle insecurity and has worked closely on the former Conflict Prevention Pool and on the development of the new Conflict, Stability and Security Fund.

3.3 We observed that there is still work to be done to align strategies and identify the most appropriate way forward. It will be important to align DFID country portfolios with emerging NSC priorities. DFID country staff comment that they expect the joint NSC strategies for individual countries to provide a better basis for joint working and programming.

3.4 It will be important to ensure strategic coherence between cross-government NSC strategies and the bottom-up, CPRD-led planning process. There is some strategic alignment and interaction between the NSC processes and the CPRDs but there are also risks – given their very different drivers and fundamental analyses – that these two separate prioritisation tools may not result in a coherent set of sustained priorities at a country level. Central political and security concerns could also distort the programming priorities and poverty focus of the activities in-country.

3.5 In our discussions, we were told that there are concerns around whether the most appropriate part of the UK Government is undertaking work in some fragile states. Almost all interventions in fragile states have political implications and, as a result, DFID needs to ensure that it focusses its efforts on the areas where it has competence and a competitive advantage and leverages other government departments, such as the FCO, where appropriate. Partnerships developed through enhanced NSC co-ordination processes may assist with this.

3.6 The new Conflict, Stability and Security Fund will come into operation in 2015-16 and is intended to bring a more strategic cross-government approach to shared priorities. It has the potential to encourage the application of skills from a wider range of departments in such environments. It will have a budget of £1 billion. There are concerns, however, including from FCO staff in-country, which echo the concerns expressed by ICAI in previous reviews,51 that FCO processes and financial management systems – despite efforts to improve these in recent years – may not be fit for the purpose of administering this much larger fund and that the FCO, and other departments that will access the fund, can learn from DFID’s experience of scaling-up.

At a country level, cross-government working is very effective

3.7 We saw examples of effective cross-government working in the countries which we visited. The MOD, the FCO and DFID demonstrate good integration in their work in Somalia, where scale-up has increased UK influence. There are good examples in DRC as well, although aspects of cross working are limited by the small number of FCO staff in-country.

DFID is expanding its range of delivery partners

The UN is no longer the default delivery partner

3.8 For DFID (as for many other donors), the UN has almost been the default delivery partner in many fragile state contexts. The UN is often the only international organisation to have established a presence in difficult environments. DFID perceives that the UN has the mandate, capacity and legitimacy in a number of areas, such as health, elections and rule of law, and is often a more acceptable delivery partner to government than, for example, private sector or NGO implementing agents. The Multilateral Aid Review evaluation process conducted in 2010 also reinforced the alignment of policy focus of many key agencies with DFID’s priorities.

3.9 DFID is now moving away from over-reliance on the UN, for a number of reasons. For example, at country level, UN agencies are sometimes unable to deliver results to the extent required or expected:

- the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) delivered some aspects of the Somalia Economic Development programme well. It did not, however, deliver the market development work at the pace or with the dynamism required. This was a factor in DFID deciding to use a private sector contractor for Phase 2; and

- in Somalia, we identified that UN agencies were finding it difficult to move beyond delivery approaches suited to humanitarian aid. For example, the UN was chosen as the implementing partner for the Somalia JHNP. Although the UN has made progress on aspects of health systems development, this has taken time. Only limited progress has been made in the delivery of basic services, because of delays in procurement and issues with disbursement of funds, as well as staff access to the affected areas.

3.10 Other reviews have found examples of UN agencies not delivering to the standard required:52

- in DRC, our report on DFID’s work with UNICEF identified issues with UNICEF’s delivery of the WASH programme, such as improvements in sanitation not being sustained over the long term.53 UNICEF has since made changes to its delivery model to ensure that improvements in sanitation are maintained over the long term;

- ICAI’s report on DFID’s Education Programmes in Nigeria contrasted two programmes, noting more effective and sustainable delivery and impact of the private sector implementing agent compared to that of UNICEF;54 and

- the IDC has recently commented on DFID’s difficulties in managing multilaterals, including UN agencies.55

3.11 DFID country offices are able to manage performance issues with UN agencies, both through liaison in-country and by escalating issues which require negotiation with UN headquarters to DFID’s United Nations and Commonwealth Department. The regular review mechanisms of the United Nations and Commonwealth Department, specifically the Portfolio Delivery Review, which was being rolled out during 2014, mark a step forward in terms of addressing performance issues for DFID country programmes delivered through UN agencies. As noted in ICAI’s 2014 Annual Report, we remain concerned that, unless properly implemented, the Portfolio Delivery Review process might not lead to quick enough improvements in poorly performing programmes.56 These issues were recently acknowledged by DFID to the IDC.57

DFID is diversifying its partner base

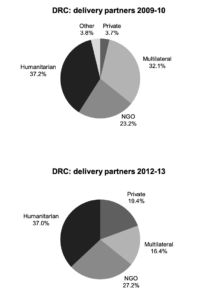

3.12 We observed that DFID has diversified its partner base over the past three to four years, as can be seen in Figure 7, relating to the DRC portfolio. On the Somalia Economic Development programme, we note that DFID has decided to use a private sector contractor in Phase 2. We also saw increasing use of NGO consortia to deliver and manage programmes. For example, a new component of the DRC WASH programme is being delivered by an NGO consortium. It is taking a different approach to DRC UNICEF WASH, thus enabling DFID to assess alternative models for scale-up of water and sanitation.

3.13 There were relatively few effective delivery channels and partners in place at the start of scale-up. The increased focus on these fragile environments has created a new marketplace for private contractors and NGOs to engage. This has increased the range of potential partners but also brought new challenges with regard to: potential over-concentration in a few big global players; slow evolution of contracting and procurement practices; and struggles to set appropriate risk transfer and duty of care approaches. This new reality needs to be more formally reflected as part of an evolved set of working practices for DFID in these countries.

3.14 There is no strategic guidance for fragile state country offices on when or how to use different types of delivery partners to maximise their different strengths. We have, however, seen the start of engagement by the procurement team and by commercial advisors in the quality assurance of business cases, in order to help country offices make the right choice of type of partner.

3.15 Third party contractors – from both the private and NGO sectors – are playing an increasingly important role in fragile states. They are becoming an important part of the delivery landscape, as they have the more flexible human resource policies and duty of care approaches, as well as appropriate compensation models which encourage people to work for sustained periods in such environments. There needs to be a clearer strategy for the use of such players, as we recommended in our 2013 review of DFID’s use of contractors to deliver aid programmes.59

3.16 It will take time for alternative delivery channels to develop the capacity required to absorb the levels of funding now available in fragile states. The number of private sector contractors willing and able to work in fragile states such as Somalia is currently limited. The availability of appropriate delivery partners should be a clear prerequisite for the design of large programmes. Scale-up of funding based on an assumption that delivery partners will materialise or that the UN system will be able to absorb the work, even in sectors where they have limited track record, is premature. DFID has recognised this issue, albeit sometime after initial scale-up. DFID’s procurement and commercial teams have increased their early market engagement. This involves engaging with a broad range of suppliers, including the private sector and NGOs, to assess their interest in working in countries like Somalia. They also provide support to country offices at the business case stage to help to consider alternatives.

DFID presence on the ground in fragile states is vital

3.17 We observed, during our country visits, the importance of DFID’s presence on the ground, if programming is to be effective in fragile states. Communication with stakeholders, understanding of the context and the ability to exert influence are significantly enhanced if DFID staff are co-located with project delivery.

3.18 In DRC, we contrasted the positive benefits of DFID’s (relatively recent) permanent presence in Goma with its approach in Kasai Occidentale, where we identified that opportunities to create synergies and add value were being missed. In Goma, the presence of a DFID programme manager, with good experience of the country context, was adding considerable focus and influence to the organisation’s engagement with the peace and stability agenda in this complex environment. By contrast, all three programmes in Kasai Occidentale engage in different ways on the issue of sexual and gender-based violence but without co-ordination or attempts to link processes or share lessons. The impact of the new permanent British Embassy facility in Mogadishu, in a secure compound, is tangible: the influence and visibility of DFID in Somalia has increased considerably. Plans for a permanent office in Hargeisa were held back earlier in the year but are currently being assessed by the FCO. We are concerned that, without one, DFID’s ability to manage a complex set of programmes on the ground, increase stakeholder engagement and enhance programme outcomes will be limited.

There are staff turnover and skillset challenges

It is important that staff in-country have the right experience and skill set

3.19 An important aspect of scale-up was the assurance from DFID headquarters that there would be additional frontline staff to support the delivery of results. In particular, this meant an increase in the number of advisors, many of whom had to be recruited from outside DFID. The time needed to recruit these additional staff was underestimated, however. It is only in the past year that offices have managed to bring on board the necessary staff numbers initially identified to take their plans forward. This slow pace of recruitment and the limited experience of some of the new staff mean that impact and influence have been compromised.

3.20 The IDC’s 2013 report noted that ‘DFID staff do not always have a good institutional memory or appropriate levels of local language skills, nor knowledge of cultural issues’.60 This can limit staff effectiveness in overseas postings. We noted that these issues impacted programme design. In DRC Police Reform, for example, the original design of the programme revealed limited understanding of how police institutions operate in a French/Belgian model; and a key term – accountability – had no direct French translation and meant little to Congolese stakeholders. In DRC, DFID is seeking to ensure that staff have some proficiency in French and provides intensive language training before staff arrive in-country. It also provides ongoing language training during the posting.

Staffing issues remain a challenge

3.21 Many of the human resource issues identified in ICAI’s previous reports61 and in other reports were apparent to us in this review, often exacerbated by the challenges of working in fragile states and the associated security issues, poor infrastructure and lack of facilities. For example, we observed:

- high staff rotation, which can lead to inefficiency and to loss of institutional memory, knowledge of local contexts and understanding of programmes;

- difficulty in attracting senior staff, especially as many postings are unaccompanied; and

- handovers which are not yet systematic.62

3.22 DFID is not alone in facing these challenges in fragile states. Most parts of the international system face difficulties in attracting quality staff to fragile states and suffer from a lack of continuity of senior staff, meaning that teams are rarely consistent or aligned. DFID’s issues are compounded across its partners in-country. This creates challenges if deep-rooted issues are to be addressed.

3.23 Despite the shift to a position where almost all DFID offices are in fragile states, DFID does not have a standard corporate operating model to address the challenges of deploying staff on the ground in difficult contexts or leveraging local personnel. DFID’s human resource function is, however, analysing the various deployment models being used by DFID country offices to learn what works.

DFID is improving its professional programme and financial management capacity

3.24 As part of its response to ICAI’s report on DFID’s Use of Contractors to Deliver Aid Programmes,63 DFID is taking steps to professionalise programme management.64 This is particularly important in the context of fragile states, where there is a greater risk of corruption due to weaker public financial management and a need for remote management if security and logistical issues make it difficult for DFID staff to monitor and manage projects directly. As a result, DFID is likely to rely much more on experienced third party contractor staff, which puts an onus on DFID to match their programme management competence.

3.25 The professionalisation of programme management is supported by new programme management systems and processes. It aims to help programme managers and advisors to understand more clearly the division of responsibilities between them. We found that, currently, this is not always the case, mainly because – as staff in DFID Somalia commented to us – advisors need to get involved in more complex programme management and respond to one-off (but frequent) requests from the centre, which reduces time for programme design, working with partners and learning activities. We realise, however, that there needs to be flexibility in the division of labour, in order to be dynamic and responsive.

3.26 DFID has recognised that financial management is a skills gap, particularly overseas.65 In early 2012, out of 14 qualified accountants working in DFID’s finance function, only one was posted overseas. By mid-2014, 13 of DFID’s 41 qualified accountants were posted overseas. Strong financial management capacity is essential in fragile states as portfolios expand, particularly given that fiduciary risks can be higher in fragile states and robust financial monitoring is needed. We believe that finance managers based in fragile states will improve the quality of financial management skills in country offices. There is not yet, however, sufficient budget for a finance manager in each fragile state country office.

3.27 DFID has also established 18 commercial advisor posts overseas to increase commercial support and early market engagement with a wider range of suppliers; and more recruitment is planned.66 This is particularly important in fragile states, where the market is complex and fewer suppliers are available. For example, we heard that DFID Somalia’s commercial advisor has run training for DFID staff on contract and key supplier management, output-based contracting, commercial and procurement skills.

Fiduciary risks in fragile states are high but recognised and addressed appropriately

3.28 Fiduciary risk is a central aspect of engagement in fragile states.67 DFID’s processes for fiduciary risk management recognise this and work to address risk where it exists. At the centre, lessons are being learned on fiscal support mechanisms to identify how they can be used effectively.

3.29 We undertook a range of meetings on and reviews of fiduciary risk management and financial management approaches during our field visits. In Somalia, fiduciary and corruption risk is a significant issue, particularly in humanitarian work. The UN Monitoring Group on Somalia noted in its 2010 report that this had become an accepted cost of aid efforts68 (although DFID Somalia does not accept this and is working with partners to reduce the risks of diversion).

3.30 To address this kind of risk, the UN in Somalia has set up new risk management arrangements for the Common Humanitarian Fund, with DFID encouragement and funding.69 A verification of the new risk management arrangements by the Swedish Embassy found them to be adequate for high-risk humanitarian work, although DFID is clear that it will need continuously and rigorously to assess the effectiveness of these risk management systems.70

3.31 The country offices which we visited have good anti-fraud strategies in place. DFID DRC’s strategy was robust, considering fiduciary risk at the corporate and programme levels and with strategies in place to address it.71 We saw cogent approaches to preventing diversion of funds and some small anti-corruption elements in existing programmes, including programmes seeking to improve public financial management for greater transparency. DFID DRC has directly engaged around the anti-corruption pact with the Prime Minster. There was, however, no direct, holistic anti-corruption programming or programmes that focussed on corruption as experienced by the poorest in society in either Somalia or DRC, as was also identified in our recent Review of DFID’s Approach to Anti-Corruption and Its Impact on the Poor.72 The reality of the wider corruption environment within which DFID is operating is not yet being tackled with sufficient vigour.

The ‘Do No Harm’ principle is central to programme design but may not be followed through in delivery

3.32 We saw good evidence that ‘Do No Harm’ is thought through in programme design, especially in more difficult environments (for example, in the Somalia Stability Fund and Core State Functions programmes). Nevertheless, there is the ongoing risk of unintended consequences in delivery. There is recent evidence that community-based interventions in very fragile environments can exacerbate conflict, causing inter-personal and inter-group disputes.73

3.33 When we visited the DRC Tuungane programme, we saw how pre-existing land and resource-based conflict can be exacerbated by DFID programme interventions. We observed conflict between villagers and pastoralists over water, where the latter were accused of damaging the DRC Tuungane-supported water supply system to feed their cows. Tensions were running high. DRC Tuungane monitoring reports detail other examples of conflicts and disputes arising in relation to the implementation of the project: disputes exacerbated between villagers and contractors; amongst village development committee members; and, in early 2014 in the town of Rutshuru – an area prone to conflict and tension – activities were suspended for two weeks, when a civil society youth movement took to the streets to protest against the International Rescue Committee. The systems and structures of the International Rescue Committee helped to defuse the situation and the project resumed in March.

3.34 ‘Do No Harm’ is not always monitored in a systematic way during programme implementation. The heightened risk of increasing tensions and causing damage though such community-based programmes operating in the midst of communities in conflict increases the need for DFID to be sensitised to this risk at all points of delivery. Monitoring of the risk of doing harm needs to be planned for and built into the regular review process.

There is a lack of clarity about DFID’s corporate appetite for risk

3.35 Engaging in fragile states is inherently risky. Risk-taking is essential to deliver long-term results.74 Work on establishing a federal system in Somalia, for example, is likely to create conflict, as it generates competition over access to power.75

3.36 DFID’s 2010 briefing paper on risk management in fragile contexts states that ‘DFID has a relatively high risk appetite and is often willing to tolerate high levels of risk where there are substantial potential benefits’.76 There are many different types of risk to be assessed, including: the risk of failure; the risk of inefficiency; the risk of diversion of funds; the risk of doing harm; and risks to human rights. These risks can be managed but will not always be avoided in a fragile state context. Heads of DFID country offices recognise that they need to take risks to be effective in fragile states but do not have clarity on how far DFID at the centre supports them in taking such risks. In DRC, for example, the country office is advancing the discussion with DFID centrally about its risk appetite regarding working with government.77

3.37 We understand that DFID is currently reviewing its approaches to risk management and is considering changes in the management of risk at a corporate level. We observe, however, that without ‘top cover’ from DFID centrally and politically, country offices may not be incentivised to take on the risks required to be effective.78 It will be important for the centre to recognise that the risk appetite and incidence of programme failure or delay will vary from context to context.

4 Findings: Impact

Impact

Assessment: Amber-Red

4.1 This section reviews the impact that scaled-up funds have had on intended beneficiaries, and assesses their potential for impact in the future. We have assessed impact at a number of different levels:

- at the strategic level – which, for this review, is the critical level – our focus has been on whether scale-up to date has had any impact on the overall objectives of reducing fragility or conflict or, given the relatively short time that has elapsed since scale-up, whether there is clear progress towards these objectives;

- at the country portfolio level, we assess the cumulative overall impact, in particular against the targets set out in the results offers; and

- at the programme level, we assess the impact of individual programmes.

4.2 We have tried to take appropriate account of the difficulty of creating high levels of transformative impact in such environments and to judge DFID against its own definitions of strategic success, as well as the absolute levels of impact.

4.3 We have seen many good programmes producing some positive results in fragile states and good work by country offices. The key issue we have sought to answer, however, is whether scale-up is likely to have the anticipated meaningful impact on fragile states, not only in the four years since the decision was made but also in the longer term. Despite the positive outputs achieved by a number of the programmes that we have reviewed and some progress at country level, it is not yet clear that this adds up to a convincing positive trajectory towards achievement of the UK Government’s stated goal of tackling conflict and fragility. We saw little evidence that there was clarity about the path from fragility to stability in DFID’s priority countries and the ‘building blocks’ of progress on the way. Consequently, it is difficult to track the progress towards making these states less fragile as a result of DFID’s scale-up.

It is difficult to measure the impact achieved as a result of scale-up

4.4 Fragile state environments are highly complex. Lasting impact has multiple dependencies and there is a constant risk of setbacks from outbreaks of conflict or natural disasters. There are difficulties of access and a lack of data for establishing a baseline and measuring progress. It is not surprising, therefore, that the results achieved against country plans, which are summarised in Annex A6, show a mix of on- and off-track results and a significant number of targets where there are, as yet, no data on progress.

4.5 Shortcomings in national systems and issues around access for data collection create difficulties in tracking results and measuring impact. In Sierra Leone, for example, real progress cannot be assessed in the health and justice sectors because DFID is reliant on national statistics, although DFID is committed to developing the evidence base as a part of its programming in these sectors.79 There has been no population census in Somalia since 1992.80 At present, DFID Yemen is reliant on its delivery partners for effective reporting. There is a lack of national data, with key surveys not conducted since 2004-05. As a result, DFID has difficulties measuring progress of the large Social Fund for Development (which accounts for 45% of the country portfolio). We recognise that DFID, like all donors, has to deal with this reality. It is important that this is reflected more in the levels of ambition that DFID sets and the types of goals that it asks of specific interventions, as well as looking to innovate in monitoring and measurement processes for such environments.

Programme monitoring is a challenge in fragile states and DFID needs to innovate and develop realistic, pragmatic and systemic approaches

4.6 As a result of the issues presented above, monitoring is a challenge in fragile states. Data are not available, there are often no government systems on which to rely and ongoing or potential conflict makes monitoring on the ground very difficult. In fragile states, there is a tendency to focus on monitoring delivery of outputs rather than seeking to assess outcome and impact. It is also hard for DFID staff to validate the level of performance being achieved through personal field visits to hard-to-reach areas. The logistical and security challenges facing the whole aid community need to be recognised.

4.7 Nevertheless, we saw some good evidence of oversight and programme reporting. We noted innovative approaches to third party monitoring and research, especially in Somalia (see Figure 8). We also saw efforts to build capacity in partners to monitor and drive performance through verification, whilst ensuring ownership of results.

- verify results reported by partners (by 2016, 150 field verification visits will be undertaken each year, covering 20 projects and 5 project evaluations);

- collect data to determine baselines, results and impacts of interventions;

- build partner capacity to monitor results and impact (to date, the programme is working with 13 implementing partners);

- undertake 50 district-level governance and security assessments per year; and

- determine the population of Somalia, by community, district and zone (the last census was in 1992).

4.8 The approach to programme monitoring being implemented in Somalia requires strong organisational support and incurs a significant financial overhead but has great potential to enhance DFID’s ability to demonstrate impact of programming on the ground. We understand that Yemen is establishing similar approaches to monitoring and that DFID’s Research and Evidence Division is carrying out evaluations of these approaches to identify good practice. We encourage more of this activity.

Scale-up has brought increased DFID influence in-country

4.9 Scaled-up funding, coherent programming and an increased focus on results have brought DFID influence at a country level. This has the potential to result in increased impact over time, assuming the advice is effective and the counterpart is stable. Some positive examples of influence we heard in the course of our review are given in Figure 9.

‘There is much greater clarity in DFID’s thinking as a result of the base in Mogadishu. Impact is symbolic but also allows capacity-building of the Government because DFID is actively engaging them in dialogue.’ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Somalia

‘DFID now has a seat at the table in health.’ Implementing Partner, DRC

4.10 In Somalia, DFID (working with other parts of the UK Government) has been able to exert considerable top-level influence on the Somalia Compact and peace-building processes. A combination of UK political interests at the highest level transmitted through diplomatic efforts, reinforced by DFID’s presence on the ground and funding for specific interventions, has added up to a unique and influential role for the UK. The policy impact obtained in Somalia is undoubtedly greater than that so far obtained in DRC, where very large amounts of funding and effort have led to a lesser degree of access to critical policy drivers. The UK had limited prior interests in DRC and it would appear that influence is being gained more at a sectoral level.

Many individual projects are meeting beneficiaries’ needs

4.11 Overall, at a programme level, we saw good evidence of programmes meeting beneficiaries’ needs, especially newer programmes and those that have been redesigned since scale-up. If this review were only focussed at individual programme level, we would consider impact to be at Green-Amber. A detailed assessment of the impact of the programmes which we reviewed can be found in Annex A7. For example, we observed that:

- Somalia Health Consortium has improved access to health services and met basic health needs. It has brought innovations, such as social franchising of pharmacies, to plug gaps in government systems;

- even though it is a new programme, DRC Primary Healthcare has already delivered and built capacity in existing faith-based networks, linking to and building state capacity where there are opportunities. It is working with the state to develop health information systems; and

- the centrally managed DFID Global Poverty Action Fund’s ‘Improved WASH for Goma’s Poor’ is specifically bringing better access to water to around 150,000 beneficiaries in Eastern DRC.81 The Mercy Corps has established a close partnership with and works alongside the water utility at the provincial level. The Somaliland Development Fund is meeting infrastructure and basic needs and also supporting the re-established National Planning Commission.