Assessing UK aid’s results in education

Purpose, scope and rationale

Education systems in developing countries have expanded schooling at a rapid rate in recent decades, but there is now an urgent need to drive up quality and learning to resolve what has been described as a “learning crisis”. There are also huge inequalities in access to and achievements in learning, including for girls (for example, an estimated three-quarters of primary school age children who may never start school are girls), children with disabilities and those affected by conflict and crises, made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic. Tackling these problems is integral to meeting Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 – Quality Education.

The purpose of this review is to assess the results of work by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the former Department for International Development (DFID, now part of FCDO) on education, particularly for girls. In 2020, DFID estimated that, between 2015 and 2020, it supported at least 15.6 million children to gain a decent education. This review will test and explore the integrity of these estimated results through: assessing the accuracy and significance of the results reported, testing whether DFID/FCDO education programming has achieved its stated objectives, including boosting the quality of education, improving learning outcomes and directing resources to children at risk of being left behind, and assessing whether DFID/FCDO is achieving sustainable impact through its aid to education.

The review will cover DFID/FCDO’s global education portfolio since 2015, and will assess the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and recent cuts to the UK aid budget on its impact. It will focus on primary and lower secondary education, as these were key areas of DFID’s 2018 education policy. It will cover bilateral, centrally managed, multilateral (core contributions and ‘multi-bi’ programmes) and humanitarian spending. We will consider girls’ education in particular as we answer the review questions. This review will reflect largely on work carried out by the former DFID but it will make recommendations for the new FCDO to take forward.

Background

DFID’s 2018 education policy stated that “education is a human right which unlocks individual potential and benefits all of society, powering sustainable development”. Global progress in education is too slow to achieve the SDG education targets by 2030. Even before the pandemic, in 2017, around 90% of children in low-income countries and 75% of children in lower-middle-income countries could not read or complete basic maths by the end of primary school. In 2018, 59 million children of primary school age and 62 million of lower secondary school age were not in school. There were also major inequalities in access to and achievements in learning, with disparities between rich and poor students beginning early, widening over time and being compounded by other sources of disadvantage, such as gender, disability and location. These inequalities have been exacerbated by the pandemic. The UN has described it as a “generational catastrophe” and found that two in three students are still affected by full or partial school closures one year into the crisis.

The UK government has made successive commitments to global education, especially to girls’ education. In particular, the Conservative Party’s 2015 manifesto set a target that, by 2020, the government would help at least 11 million children in the poorest countries gain a decent education and promote girls’ education.

n 2018, under an education policy published by DFID, the UK government committed to improving quality and equity in education by focusing on three priorities: investing in good teaching, supporting system reform which delivers results in the classroom, and stepping up targeted support to poor and marginalised children. In May 2021, FCDO published its ‘action plan’ for girls’ education, in which it committed to “re-double” its efforts as a champion of education for girls. In 2021, the UK co-hosted a Global Partnership for Education replenishment summit to urge world leaders to invest in getting children into school, and girls’ education was a central theme of the UK’s G7 presidency in 2021.

The UK’s bilateral official development assistance to education in 2019 was £789 million (of which DFID spent £695 million) and the UK’s imputed share of multilateral aid to education in 2019 was £223 million. Following the merger of DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020, government ministers listed girls’ education among the priority areas for development. In April 2021, it was announced that FCDO would spend £400 million on girls’ education in 2021–22. According to analysis by the Center for Global Development, this is a modest increase in the share of the aid budget but a decrease of around £175 million in actual spending since 2019.

DFID claimed that it supported at least 15.6 million children to gain a decent education between 2015 and 2020.19 DFID attributed these results to programmes managed by DFID/FCDO country offices (11.9 million children), programmes run by DFID/FCDO UK-based teams (2.4 million children, through centrally managed and ‘multi-bi’ programmes) and to DFID/FCDO’s contributions to core multilateral funding (2.2 million children).

ICAI’s previous review of education, published in 2016, focused on girls, particularly those who are marginalised and disadvantaged. It awarded DFID an amber-red score. It noted a lack of coherence between the different UK aid channels in terms of addressing girls’ marginalisation in education and a loss of focus on marginalisation during the implementation of programmes run by DFID/FCDO country offices. In 2018, ICAI’s follow-up of the government’s response to this review noted that DFID had made impressive improvements to address the shortcomings identified.22 This current review will build on that work but will assess education results more generally. This review will also build on ICAI’s review of DFID’s approach to disability in development, published in 2018, which examined DFID’s programming in five sectors, including education. In addition, it will complement the review by the National Audit Office (NAO) of DFID’s broader commitment to support gender equality.

Review questions

This review is built around the evaluation criteria of effectiveness, equity and impact. It will address the following questions and sub-questions. Review questions and sub-questions have been developed for each of the above criteria (see Table 1).

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Effectiveness: How effective is DFID/ FCDO aid to education in delivering its intended results? | • How accurate and robust are DFID/FCDO’s education results claims? • To what extent are DFID/FCDO education programmes achieving their intended results, particularly in relation to girls’ education? • How well does DFID/FCDO use its influence as a major multilateral funder to strengthen the quality of multilateral education programming and international education initiatives? |

| 2. Equity: To what extent are DFID/ FCDO’s education interventions reaching the most marginalised? | • To what extent are targeted DFID/FCDO interventions relevant to the needs of marginalised groups, including children with disabilities, children affected by crises and hard-to-reach girls? • How well has DFID/FCDO education support reached these target groups? • How effective is DFID/FCDO education programming in conflict-affected zones and for children displaced by humanitarian disasters? |

| 3. Impact: To what extent is DFID/FCDO achieving sustainable impact through its aid to education? | • To what extent are DFID/FCDO education programmes based on evidence of ‘what works’? • How well does DFID/FCDO work with partners to strengthen the quality of national education systems? • How well is DFID/FCDO aid to education helping children in partner countries (and girls in particular) to gain a decent education? • To what extent has DFID/FCDO taken action to limit the effects of COVID-19 and UK aid budget cuts on the impact of its aid to education? |

Methodology

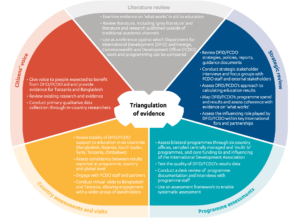

The review methodology includes the following five components, to allow for data triangulation to robustly answer the review questions.

Figure 1: Overview of the methodology

The earlier components of the methodology provide a foundation for the later ones. For example, the programme assessments will inform the country assessments and visits. Similarly, the strategic review will inform the other components.

Component 1 – Literature review: This component will identify areas of consensus around ‘what works’

in aid to education. It will explore evidence on ‘what works’ in terms of types of intervention (including for marginalised groups) and ways of working, the conditions for sustainable impact, and best practice in results measurement. The literature review will be based on a synthesis of academic literature, ‘grey literature’, and literature and research published outside of traditional academic channels. It will be used as a reference against which DFID/FCDO’s work and programming can be compared.

Component 2 – Strategic review: We will review DFID/FCDO’s strategies, policies, reports, guidance documents and any relevant evaluations. We will conduct strategic stakeholder interviews with DFID/FCDO staff, other bilateral donors with substantial education investments, and relevant multilateral agencies. We will also consult with other types of stakeholders such as civil society groups and academic experts. We will engage with DFID/FCDO’s education adviser cadre through focus group interviews. Interviews and focus groups will be semi-structured and will explore all the review questions. All such qualitative data will be systematically analysed using an analysis grid linked to the review questions and judgment criteria.

To help test the validity of DFID/FCDO’s results, we will assess the approach adopted by DFID/FCDO when calculating its education results. This will include assessing how this approach has been applied in practice by country offices and central departments.

We will map DFID/FCDO programme expenditure and results since 2015 in terms of modalities, intervention types and extent of focus on girls and marginalised groups. This will enable us to provide an assessment of how DFID/FCDO has intended to achieve its education results and how this has compared with the evolving evidence on ‘what works’.

Through the desk review and interviews, we will also assess the influencing role played by DFID/FCDO within key international fora and partnerships, including what has been achieved through this influencing.

Component 3 – Programme assessments: DFID/FCDO’s education portfolio and the spending and activity that contribute to its reported results are diverse. It involves programmes funded or supported through four different modalities or channels of aid. We will therefore select the following contributors to these results for assessment:

- A centrally managed programme – Girls’ Education Challenge.

- Support for ‘multi-bi’ programmes – the Global Partnership for Education and Education Cannot Wait.

- Core contributions to a multilateral fund – the International Development Association (IDA). It is notedthat FCDO’s core contribution to IDA is governed in a different way to bilateral programming, and this will be reflected in our review methodology. FCDO’s policy engagement with the World Bank is not exclusive to IDA.

- The largest bilateral country programme contributors for six sampled countries: Bangladesh, Tanzania, South Sudan, Syria, Rwanda and Zimbabwe.

These ‘programme’ assessments will involve desk reviews of programme/fund documentation and interviews with relevant staff. They will use an assessment framework, which will enable systematic assessment of this sample of programmes/funds against the review questions. These assessments will also help us to test the quality of the methodology and data that DFID/FCDO has input into its global results claims.

Component 4 – Country assessments and country visits: We will assess the totality of the UK’s contribution to decent education in our sample of six selected countries, particularly through the selected bilateral, centrally managed and ‘multi-bi’ programmes, the work of the selected multilateral to which DFID/FCDO provides core contributions, and DFID/FCDO’s influencing activity in those countries. We will also assess the extent to which there is consistency between results reported at the programme, country and global levels. The assessments will draw on the bilateral country programme assessments and on documentation about the

country context and about the other channels operating in those countries. They will also draw on evidence from interviews with a handful of additional stakeholders in each country, including the DFID/FCDO education adviser and statistics adviser in country and stakeholders from the partners involved in the other types of spending selected. We will use a country assessment template to allow systematic assessment across the countries.

For two of these six countries, Bangladesh and Tanzania, we will conduct a virtual country visit to enable us to engage in more depth with programme staff, partners and external stakeholders. This will enable us to interrogate DFID/FCDO’s results claims and examine the extent to which programmes reach the most vulnerable and the extent to which the totality of UK support to education in these countries is delivering sustainable impact.

Component 5 – Citizens’ voice: For Bangladesh and Tanzania, we will also engage citizens to help ensure that the voices of those expected to benefit from UK aid to education are reflected in our findings, give a human face to the findings, and provide another source of evidence to triangulate with that from other components of the methodology. We will work with local researchers on this component. We will review existing research and evidence on the education needs of particular groups in these countries and carry out semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions with those intended to benefit from UK aid (using either in-person or remote data collection methods). We will develop and provide clear guidelines to field researchers on ethical protocols.

Sampling approach

In sampling activities funded by different modalities of aid, we have aimed to achieve a balance that broadly reflects the contributions of these different channels to DFID/FCDO’s results claims.

We have selected the centrally managed and ‘multi-bi’ programmes that contributed the most to the global results and which had the greatest basic education spend to date:

- Girls’ Education Challenge – £569 million spent over two phases since 2015.

- Support for the Global Partnership for Education – £374 million spent over two phases since 2015.

- Support for Education Cannot Wait – £92.7 million spent over two phases since 2015.

The multilateral fund that made by far the largest contribution to DFID/FCDO’s imputed education results through the UK’s core contributions was IDA. We have therefore selected it for assessment. We will ensure that we learn from, and do not duplicate, the work of ICAI’s ongoing review on the UK’s spending through IDA.

Criteria for the countries and bilateral programmes included in our sample are: contribution to results, relevant spend, range of programming and range of country contexts. As a result, we selected Bangladesh, Tanzania, South Sudan, Syria, Rwanda and Zimbabwe. We plan to conduct virtual visits and in-person citizens’ voice work in Bangladesh and Tanzania.

Table 2: Selected countries – UK aid to education received through different channels since 2015

| Total basic education spend through the DFID/ FCDO country office over the results period | Was Girls’ Education Challenge operational? | Was the Global Partnership for Education operational? | Was Education Cannot Wait operational? | Was the country eligible to receive IDA resources?* | Children that the DFID country office claimed to have supported to gain a decent education over the results period** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | £136 million | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,859,000 | |

| Tanzania | £161 million | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 657000 |

| South Sudan | £57 million | Yes | Yes | Yes | 890,000 | |

| Syria | £150 million | Yes | Yes | 408,000 | ||

| Rwanda | £66 million | Yes | Yes | Yes | 364,000 | |

| Zimbabwe | £56 million | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 133,000 |

We selected 13 bilateral country programmes from these six countries, choosing the programmes with the greatest relevant spend and contribution to DFID/FCDO’s results over the review period.

Table 3: Sampled bilateral programmes

| Dates | Total programme budget | Spending on basic education since 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | |||

| Bangladesh Education Development Programme | 2011–2018 | £115 million | £31 million |

| Underprivileged Children's Education and Skills Programme | 2012–2016 | £24 million | £5 million |

| Youth Education and Skills Programme for Economic Growth | 2016–2021 | £26 million | £5 million |

| Strategic Partnership Arrangement II between DFID and BRAC | 2016–2021 | £224 million | £58 million |

| Tanzania | |||

| Education Quality Improvement Programme – Tanzania | 2012–2021 | £90 million | £74 million |

| Education Programme for Results (EP4R) | 2014–2021 | £104 million | £95 million |

| South Sudan | |||

| Girls' Education in South Sudan | 2013–2019 | £61 million | £44 million |

| Girls’ Education in South Sudan Phase II | 2018–2024 | £70 million | £17 million |

| Syria | |||

| Syria Education Programme | 2017–2022 | £63.5 million | £49 million |

| Rwanda | |||

| Rwanda Learning for All Programme | 2014–2021 | £96 million | £76 million |

| Zimbabwe | |||

| Zimbabwe Education Development Fund Phase II | 2012–2019 | £59 million | £35 million |

| Zimbabwe Girls Secondary Education 2012–2022 | 2012–2022 | £40 million | £22 million |

Limitations to the methodology

The review sets out to examine DFID/FCDO’s work on basic education and the results of this spending and activity. This is ambitious due to the scale and diversity of relevant basic education programming, which takes place through different channels. This review is therefore at a strategic level, giving a broad understanding of the spending priorities attached to this area of work and the contribution of different funding channels. The methodology has a number of limitations.

First, given the large and complex portfolio, the review will only be able to examine selected countries and programmes. This will limit the extent to which it will be able to report findings which can be generalised. Our assessment will be based on a sample of countries that provides good overall coverage of the expenditure of basic education programmes, including good coverage of those that contribute to DFID/FCDO’s reported results. Six country assessments, including two visits, will look at performance across multiple funding streams. In addition, the strategic review will consider the whole of the portfolio in scope.

Second, COVID-19 has disrupted education programmes since March 2020, posing a risk to the sustainability of the results reported. We will, therefore, explore available qualitative evidence concerning the response to COVID-19 and the extent to which results reported between 2015 and 2020 have been affected, including implications for sustainability.

Finally, there are some methodological constraints to assessing the extent to which DFID/FCDO programmes are based on evidence of ‘what works’ and the needs of targeted communities. Although the literature on the effectiveness of aid for education is extensive, there remain areas where evidence is weaker, for example on ‘what works’ in crisis settings. Evidence can also be context-specific. The review will therefore take into account available evidence from the literature and draw on qualitative evidence from stakeholders, including citizens, in selected case study countries. Areas where evidence is missing or inconclusive will be noted.

Risk management

There are a range of risks that need to be addressed in undertaking this review. The table below identifies these risks as well as the mitigating actions that we will take in order to ensure they do not undermine the research.

Table 4: Risks and mitigation

| Risks | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| n-person country visits by the review team are not possible due to COVID-19 restrictions on entry, movement and quarantine | • We will conduct virtual country visits, involving interviews with a range of stakeholders. We will apply the lessons learned from virtual visits undertaken on other recent ICAI reviews. |

| Citizens’ voice research cannot be undertaken face to face by local researchers due to COVID-19 restrictions in the visit countries | • Local researchers will use either in-person or remote data collection methods. We will learn from other recent ICAI reviews about what remote methods have been used most successfully to engage with people expected to benefit from UK aid. |

| Issues around COVID-19 overshadow longer-term issues in the review’s focus | • The review largely covers the pre-pandemic period and will examine the whole of that period as well as more recent developments. |

| Because the basic education portfolio is large and covers a number of different funding channels, the review either fails to adequately cover the whole portfolio or fails to provide in-depth insights | • The strategic review will ensure that the whole range of UK aid to education is covered while the country- and programme-level assessments will allow deeper assessment in some cases. |

Risks will be reviewed on a regular basis and any mitigating actions adjusted as the external operating environment changes and if any new risks emerge.

Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI commissioner Tarek Rouchdy, with support from the ICAI secretariat. Both the methodology and the final report will be peer-reviewed by Professor Keith Lewin, Emeritus Professor of International Development and Education at the University of Sussex.

Timing and deliverables

The table below sets out the timing of the key phases and deliverables for this review.

| Key stages and deliverables | Dates/timeline |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach paper: September 2021 |

| Data collection | Desk research: July–September 2021 Fieldwork: September–October 2021 Evidence pack: October 2021 Emerging findings presentation: November 2021 |

| Reporting | Report drafting: December 2021–March 2022 Final report: April 2022 |