Assessing UK aid’s results in education

Score summary

UK aid-funded education programming in developing countries has been ambitious and mainly well implemented. However, vast challenges remain for improving the quality of education. FCDO needs to do more to ensure that spending on education results in children learning better.

The former Department for International Development, and now Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (DFID/FCDO) reports that it has gone beyond its 2015-20 corporate target on education, by supporting 15.6 million children to gain a ‘decent education’. Although the methodology to calculate this figure is systematic and reasonable, it does not track learning achievements or other indicators of education quality. FCDO is working to develop an approach to tracking the quality of education it is supporting at the corporate level.

Our assessment of a sample of bilateral and multilateral education programmes supported by DFID/ FCDO suggests that they have achieved their overall goals. DFID/FCDO’s knowledgeable education advisers add significant value at the country level and have helped to make bilateral and multilateral programming more effective. However, a quarter of programmes with activities to support girls did not meet DFID/FCDO’s expectations in this area.

DFID/FCDO has been viewed by external stakeholders as a global leader in addressing inequalities in education. It has implemented programming relevant to the needs of highly marginalised children, particularly hard-to-reach girls, children in crises and children with disabilities. However, overall results in reaching disabled children are unclear and some multi-country programmes have faced challenges. The performance of the Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) for marginalised girls did not meet DFID/ FCDO expectations for attendance, learning and sustainability at the start of the review period but has improved since 2017 under phase 2 of the programme. DFID/FCDO has also made progress in influencing multilateral organisations to focus on the most marginalised, but there remain some areas where more progress is needed.

Vast challenges remain for improving the quality of education and learning in partner countries, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. While DFID/FCDO has contributed to improvements, data limitations mean that it is not able to judge impact on learning for many of its programmes. Among the 11 programmes that did collect such data, only six achieved their learning targets for children. All of the sampled DFID/FCDO programmes made valuable use of evidence of ‘what works’ in education, and most programmes supported education systems strengthening effectively. While DFID/FCDO has played an important role in coordinating education sector actors and been active in influencing key partners, it has had limited impact in encouraging these actors to embrace new sources of international finance for education, which has hindered new initiatives.

The pandemic has posed major challenges for education systems and for UK-supported education programmes across the world. We found numerous examples of DFID/FCDO adapting programming to limit disruption to education. Recent reductions in UK aid to education pose a potential risk to sustaining the UK’s influence on education globally.

FCDO needs to strengthen its emphasis on supporting and tracking children’s learning, maintain a consistent focus on girls’ education and reaching the most marginalised, continue to promote education systems strengthening, and enhance its convening and influencing role.

Individual question scores:

- Effectiveness: How effective is DFID/FCDO aid to education in delivering its intended results? GREEN/ AMBER

- Equity: To what extent are DFID/FCDO’s education interventions reaching the most marginalised? GREEN/ AMBER

- Impact: To what extent is DFID/FCDO achieving sustainable impact through its aid to education? GREEN/ AMBER

Executive summary

Education is a human right for everyone and realising this right has been a core focus of global development efforts over the last two decades. Supported by these efforts, developing countries have rapidly expanded access to schooling over this period.

Despite this, 121 million children of primary and lower-secondary school age were not in school in 2018. There is also an urgent need to improve education quality to resolve what has been described as a ‘learning crisis’, with children attending school but learning very little in many countries around the world, due to weak education systems. In addition, there remain huge inequalities in access to school and achievements in learning, especially for girls, in many contexts. These challenges have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic over the last two years.

The UK government is a major donor to global education. It spent £4.4 billion on bilateral aid to education during 2015-20 and invested an estimated £1.3 billion on education through core contributions to multilateral organisations during 2015-19. In 2015, the UK committed to help at least 11 million children in the poorest countries to gain a ‘decent education’ by 2020, and to promote girls’ education.

The purpose of this review is to assess the results of UK aid’s primary and lower-secondary (basic) education programming over the 2015-20 period. This work is led by the former Department for International Development (DFID), which in 2020 merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). The review has a particular focus on girls’ education because this has been a government priority over the review period. It covers both bilateral and multilateral education programmes being supported by the UK.

The results assessed in this review relate to the achievements of UK aid in terms of the number of children supported to gain access to school and to learn. We test the accuracy and significance of these results and assess a sample of programmes in depth. We judge DFID/FCDO’s achievements on education against the goals it has set, including in relation to reaching girls, targeting the most marginalised children and achieving sustainable impact.

This review assesses DFID/FCDO’s response to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on education. It also reflects on DFID/FCDO’s ability to sustain its impact on education following the recent reductions to the UK aid budget.

Effectiveness: How effective is DFID/FCDO aid to education in delivering its intended results?

DFID/FCDO estimated that, between 2015 and 2020, it supported at least 15.6 million children to gain a ‘decent education’ (see paragraph 4.6) – over half of whom were girls. DFID/FCDO calculated this figure by aggregating results across the programmes it financed, with each programme attributing a portion of the total number of children in the school system it was supporting to the UK’s assistance based on the share of resources or results it was responsible for. We judged this corporate-level results methodology to be a systematic and reasonable way to estimate the reach of UK-supported programmes, although it is likely to have resulted in an underestimate.

This results methodology does not track learning achievements or other measures of the quality of education being supported by the UK. DFID/FCDO justified this on the basis that there were no common metrics for measuring education quality during this period and UK support had helped children to gain a better education than they otherwise would have done without UK assistance. Nevertheless, being able to track and report on the UK’s aggregate results around children’s learning would provide FDCO with a better measure of its support for quality, or ‘decent education’. FCDO is currently working to develop such results approaches.

Our review of a sample of bilateral and multilateral education programmes supported by DFID/FCDO found that they largely met their overall expectations in delivering their planned activities effectively. However,

a quarter of the programmes which targeted girls explicitly in some way did not achieve their goals, although performance seemed stronger than that previously found by ICAI.6

DFID/FCDO has been influential in strengthening multilateral education programming, including through being a major donor to and supporting the governance and functioning of both the Education Cannot Wait fund (ECW) and the Global Partnership for Education (GPE). However, one area of weaker performance has been in relation to the quality of country education sector plans supported by GPE. FCDO judged that these remain overly ambitious and unachievable in some cases.7

There was a strong consensus among stakeholders engaged across all six focus countries that the presence of knowledgeable and skilled UK education advisers has strengthened the effectiveness of bilateral and multilateral programmes supported by the UK.

We therefore award a green-amber score for effectiveness.

Equity: To what extent are DFID/FCDO’s education interventions reaching the most marginalised?

DFID/FCDO committed to reaching the most marginalised children through its aid to education, and identified three priority groups: children with disabilities, children affected by crises and hard-to-reach girls.

It has implemented programming relevant to their needs, especially for hard-to-reach girls, and has been seen as a global leader in this area. The centrally managed Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) has been DFID/ FCDO’s largest single channel for supporting marginalised girls (£565 million during 2015-20). The first phase of GEC (2012-2017) fell short of achieving DFID/FCDO’s targeted levels of attendance, learning and sustainability. The second phase (2017-25) has so far been stronger around influencing systemic change, but is still not doing as well as DFID/FCDO expected on learning.

Factors that have helped DFID/FCDO to reach the most marginalised children, and support others to do so, include employing staff with strong contextual knowledge, locally linked delivery partners, and improving internal incentives for emphasising equity.

We therefore award a green-amber score for equity.

Impact: To what extent is DFID/FCDO achieving sustainable impact through its aid to education?

In many developing countries, the challenges for ensuring that children learn effectively in school are significant. It is therefore important that DFID’s 2018 Education policy8 committed the department to deepen its focus on tackling the ‘learning crisis’.

Despite this strategic focus, many of the DFID/FCDO programmes we sampled were not collecting the information required to assess their impacts on children’s learning. Among the 11 programmes which did track their impact on children’s learning, six met DFID/FCDO’s expectations. Those programmes not meeting expectations included GEC, with the evaluation of its first phase finding that significant changes in some projects’ design and delivery were needed to secure the required literacy and numeracy gains.

All the programmes we reviewed used evidence on the effectiveness of education interventions in their design and/or ongoing management. DFID/FCDO has also made significant investments in expanding global research on education – a valuable public good.

The majority of programmes supported by DFID/FCDO aimed to contribute to the strengthening of national education systems in some way. We judged that all but two of these programmes achieved their systems strengthening goals, and most external stakeholders noted that DFID/FCDO had strengthened systems effectively.

Across our six assessment countries, the UK has played a significant role in convening education actors to work together more effectively and in influencing education systems strengthening. There was a strong level of coherence across UK education aid channels in these countries. However, DFID/FCDO’s progress in encouraging mobilisation of new sources of international finance for education has been slow.

Since the first half of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused major disruption to education systems around the world. DFID/FCDO has taken effective action to adapt its programmes to limit the effects of COVID-19 on their impact, including through introducing a focus on community-based learning and supporting schools

to reopen safely.

Major reductions in total UK aid in 2020 and 2021 have affected UK bilateral and multilateral aid to education and may pose a risk to sustaining the UK’s influence on education globally.

DFID/FCDO has made positive contributions to national education systems strengthening through its programmes, coordination of development partners and use of evidence for decision making. FCDO should build on these strengths, including ensuring that programmes are aligned around learning.

We therefore award a green-amber score for impact.

DFID/FCDO’s aid to education has reached children affected by conflict and humanitarian disasters effectively through various channels. All six programmes we assessed which focused explicitly on children in crises fulfilled DFID/FCDO’s implementation plans. Central to this performance is the ECW fund, which has supported 4.6 million children in conflict zones to access education since 2016.

The focus on children with disabilities has grown in DFID/FCDO programming over the review period with interventions on school infrastructure, social attitudes and teacher support. There have, however, been deficiencies in results reporting, with DFID/FCDO unable to track how many children with disabilities are being reached by education programming, and relevant centrally managed programmes have been less successful than hoped. Stakeholders also noted that the UK’s focus on education for children with disabilities has recently decreased.

DFID/FCDO has also been active in influencing multilateral organisations such as GPE, ECW and the World Bank’s International Development Association to develop gender strategies and supporting their implementation, although further progress is required.

Recommendations

We offer five recommendations to FCDO to help improve its aid to education.

Recommendation 1:

Future FCDO aid for education should have a greater focus on children’s learning, based on evidence of ‘what works’ that is relevant to the context.

Recommendation 2:

FCDO should accelerate its work with partner governments to improve their ability to collect and use good data on children’s learning.

Recommendation 3:

FCDO should ensure that all its aid to education maintains a consistent focus on girls in its design and implementation.

Recommendation 4:

To promote systemic change that benefits the most marginalised, FCDO should have a greater focus on dissemination and uptake of evidence of ‘what works’ for these groups.

Recommendation 5:

FCDO should enhance the convening and influencing role it often plays in partner countries, to promote the impact of aid to education on learning.

Introduction

Education systems in developing countries have expanded access to schooling at a rapid rate in recent decades. Despite this progress, large numbers of children remain out of school and there is an urgent need to improve educational quality. There is a ‘learning crisis’, with many children attending school in education systems around the world learning very little. Even after several years in school, millions of students lack basic literacy and numeracy skills. At the end of 2019, 53% of children in low- and middle- income countries were living in ‘learning poverty’ – that is, they were unable to read and understand a simple text by the age of ten. In sub-Saharan Africa, this figure was closer to 90%.

More investment in education is needed globally. However, without greater focus on education quality in school systems, no amount of investment in schooling will provide students in the developing world with what they need. The World Bank’s 2018 report on education emphasises that there is little or no association across countries between levels of spending and levels of children’s learning. Countries such as India have more than doubled spending on education, but their learning levels have in fact deteriorated over time. Investment in education systems needs to be reoriented to be focused on improving learning outcomes.

There are also huge inequalities in access to and achievements in learning, made worse by the pandemic. An estimated three-quarters of primary school age children who may never start school are girls, and children with disabilities and those affected by conflict and crisis are also disadvantaged in their access to education. Tackling all of these problems is integral to meeting Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 – Quality Education.

There is no single approach to improving learning, due to the influence of many complex factors that are specific to the country context and the needs of individual children. National education sector plans designed to strengthen education systems address factors such as: teacher competence, teacher management, learning materials, the learning environment, school infrastructure, school leadership and the curriculum. For girls, there are many other factors that influence their ability to access and complete education, including attitudes to girls’ education, safety in school and on their journey to school and facilities for managing periods (see Box 6).

The purpose of this review is to assess the results of the work on education, particularly for girls, of the former Department for International Development (DFID), which merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020 to create the current Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). This review has a particular focus on girls’ education, which is a long- standing UK government priority.

This review covers DFID/FCDO’s global education portfolio since 2015, which was the start of its 2015-20 ‘results period’. In 2015, the government set a target to support at least 11 million children to gain a ‘decent education’ by 2020. It also committed to help 6.5 million girls in poor countries go to school. In this results review, we assess the accuracy of the results reported against this target, assess whether DFID/FCDO education programmes are being delivered effectively, including reaching the most marginalised, and assess whether DFID/FCDO programmes are achieving sustainable impact. Our review

also includes an assessment of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and recent reductions to the UK aid budget on the sustainability of the impact these programmes have achieved. It focuses on basic (primary and lower-secondary21) education, as this was the priority for UK aid to education set out in DFID’s 2018 Education policy22 and 2013 Education position paper.23 It covers bilateral, centrally managed, multilateral (core contributions and ‘multi-bi’24 programmes) and humanitarian spending. This review reflects on work carried out by the former DFID but makes recommendations for the new FCDO to take forward.

Our review also includes an assessment of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and recent reductions to the UK aid budget on the sustainability of the impact these programmes have achieved. It focuses on basic (primary and lower-secondary) education, as this was the priority for UK aid to education set out in DFID’s 2018 Education policy and 2013 Education position paper. It covers bilateral, centrally managed, multilateral (core contributions and ‘multi-bi’ programmes) and humanitarian spending. This review reflects on work carried out by the former DFID but makes recommendations for the new FCDO to take forward.

Box 1: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. The following SDGs are particularly relevant for this review:

Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all – ensuring that inclusive and equitable quality education is at the heart of DFID/FCDO’s commitments around education. The scope of this review is limited to basic education, rather than lifelong learning.

Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls – DFID/FCDO has made gender equality in education a focus of its aid to education over the review period.

Table 1: Review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness: How effective is DFID/ FCDO aid to education in delivering its intended results? | • How accurate and robust are DFID/FCDO’s education results claims? • To what extent are DFID/FCDO education programmes achieving their intended results, particularly in relation to girls’ education? • How well does DFID/FCDO use its influence as a major multilateral funder to strengthen the quality of multilateral education programming and international education initiatives? |

| Equity: To what extent are DFID/ FCDO’s education interventions reaching the most marginalised? | • To what extent are targeted DFID/FCDO interventions relevant to the needs of marginalised groups, including children with disabilities, children affected by crises and hard-to-reach girls? • How well has DFID/FCDO education support reached these target groups? • How effective is DFID/FCDO education programming in conflict- affected zones and for children displaced by humanitarian disasters? |

| Impact: To what extent is DFID/FCDO achieving sustainable impact through its aid to education? | • To what extent are DFID/FCDO education programmes based on evidence of ‘what works’? • How well does DFID/FCDO work with partners to strengthen the quality of national education systems? • How well is DFID/FCDO aid to education helping children in partner countries (and girls in particular) to gain a ‘decent education’? • To what extent has DFID/FCDO taken action to limit the effects of COVID-19 and UK aid budget reductions on the impact of its aid to education? |

Methodology

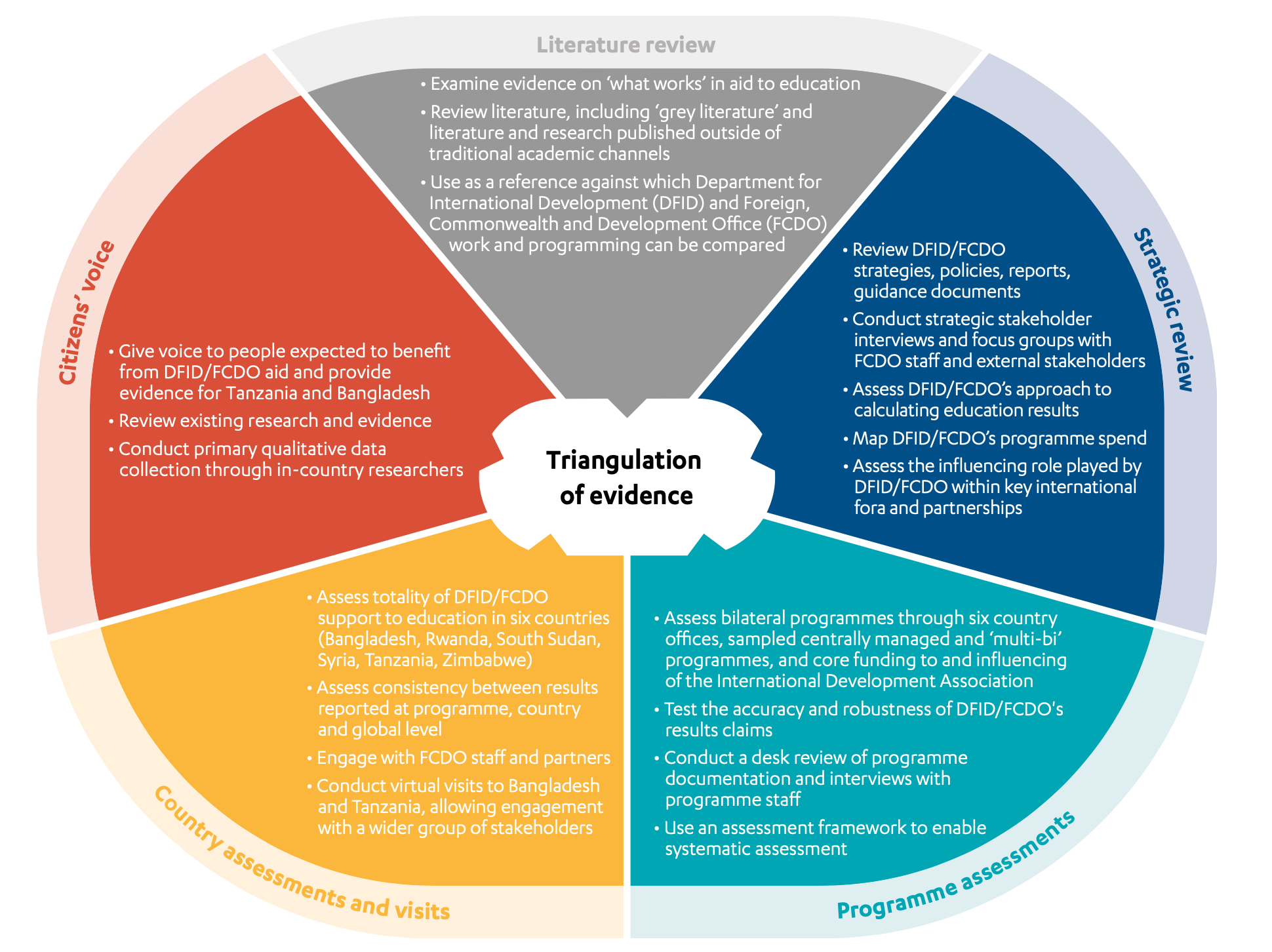

The review methodology included the following components, to allow for data triangulation to robustly answer the review questions.

Figure 1: Overview of methodology

Component 1 – Literature review: This component identified areas of consensus around ‘what works’ in aid to education. It examined evidence on ‘what works’ in terms of types of intervention (including for marginalised groups) and ways of working. The literature review was based on a synthesis of academic literature and ‘grey literature’ published outside traditional academic channels. It was used as a reference point for comparison of DFID/FCDO’s work and programming.

Component 2 – Strategic review: We reviewed DFID/FCDO’s relevant strategies, policies, reports, guidance documents and evaluations. We conducted strategic stakeholder interviews with FCDO staff, other bilateral donors with substantial education investments, and relevant multilateral agencies. We engaged with FCDO’s education adviser cadre through focus group interviews. We also consulted with other types of stakeholders such as civil society groups and academic experts. This qualitative data was systematically analysed using an analysis grid linked to the review questions. We assessed the approach adopted by DFID/FCDO when calculating its education results. Through the desk review and interviews, we also examined the influencing role played by DFID/FCDO within key international fora and partnerships.

Component 3 – Programme assessments: We selected a sample of programmes which contributed to DFID/FCDO’s reported results for assessment:

- the largest bilateral country programme contributors for six sampled countries

- the Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC), a major centrally managed bilateral programme

- bilateral support to multilateral funds – the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and Education Cannot Wait (ECW)

- core contributions to the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA).

These assessments involved reviewing programme documentation and conducting interviews with relevant staff. They used an assessment framework, which enabled systematic assessment against the review questions. We judged performance against DFID/FCDO’s own expectations set out in planning documents for each programme. These assessments also helped us to test the accuracy and robustness of the methodology and data that DFID/FCDO used to calculate the global results estimates.

Component 4 – Country assessments and country visits: We identified a sample of six countries (Bangladesh, Tanzania, South Sudan, Syria, Rwanda and Zimbabwe) in which to assess the totality of the UK’s contribution to education. We also used this component to assess the extent to which there is consistency between results reported at the programme, country and global levels. The assessments drew on the programme assessments, on documentation about the country context, and on evidence from interviews with additional stakeholders in each country. These included the DFID/FCDO education and results advisers and external stakeholders involved in the programmes selected. We used a country assessment template to allow systematic assessment across the countries. For two of these countries, Bangladesh and Tanzania, we conducted virtual country visits, which involved undertaking interviews remotely, because of the COVID-19 travel restrictions that were in place at the time of the review. These visits enabled us to engage in more depth with programme staff and external stakeholders than by using documents alone.

Component 5 – Citizens’ voice: For Bangladesh and Tanzania, we engaged with citizens to help ensure that the voices of those expected to benefit from UK aid to education are reflected in our findings, while providing another source of evidence to triangulate with other components of the methodology. This work was carried out through local researchers in each country, who carried out semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions with pupils, parents, teachers and community leaders.

Box 2: Limitations to the methodology

The review has examined DFID/FCDO’s work on basic education and the results of this activity. This is ambitious due to the scale and diversity of relevant basic education programming. Given this large and complex portfolio, the review has been limited in its coverage – we have only been able to examine selected countries and programmes in detail. To mitigate against this limitation, the strategic review has considered the whole of the portfolio in scope, to enable us to report findings which can be generalised with greater confidence.

There are also some methodological constraints to assessing the extent to which DFID/FCDO programmes are based on evidence of ‘what works’. While the literature on the effectiveness of aid for education is extensive, there remain areas where evidence is weaker, for example on ‘what works’ in crisis settings, and evidence can be context-specific or contested.

Disentangling DFID/FCDO’s impact on changes in education systems and children’s learning from the actions of other partners is challenging. DFID/FCDO has provided diverse support to governments and other organisations, which are usually investing significant volumes of their own resources, alongside a number of donors working on the same programmes. There are also a range of external factors affecting results achieved in education. Our approach to addressing this challenge was to look comprehensively at all UK spending and activity on basic education in our assessment countries, considering different documentary sources and talking to multiple different stakeholders.

Sampling approach: In sampling programmes funded by the different modalities of aid, we aimed to achieve a balance that broadly reflects the relative contributions of these different channels to DFID/ FCDO’s results estimates and the diverse nature of UK aid to education. Criteria that we used to select the countries and bilateral programmes included in our sample were: the scale of results, level of relevant spend, and range of programming and country contexts.

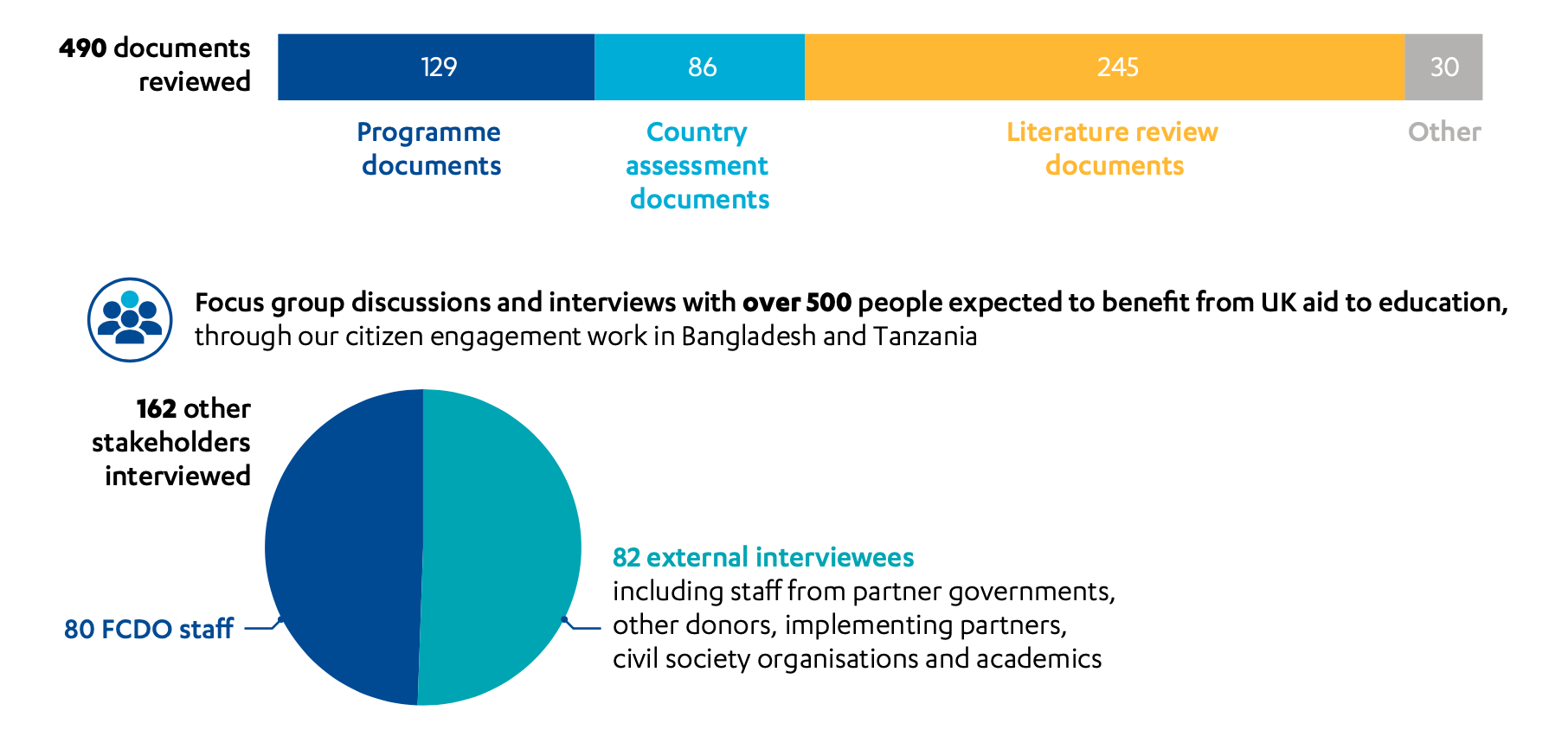

Figure 2: What we did

Figure 3: DFID/FCDO education spending assessed in detail for this review

Background

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that education is a fundamental human right for everyone. DFID’s 2013 Education position paper reaffirms this right and states that education is “a global public good and a necessary ingredient for economic development and poverty reduction”. DFID’s 2018 Education policy emphasised that education “unlocks individual potential and benefits all of society, powering sustainable development”.30 DFID/FCDO has viewed girls’ education as a particularly “smart investment” because “the benefits are wide-ranging enough to stop poverty in its tracks between generations”.

Alongside all UN member states, in 2015 the UK adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which included a commitment to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” by 2030 (SDG 4). Global progress towards the targets associated with this goal – increasing access to school and improving the quality of education so that it leads to relevant and effective learning outcomes – is currently too slow. Even before the pandemic, in 2018, 59 million primary school age children and 62 million lower-secondary school age children were not in school.

In 2017, around 90% of children in low-income countries and 75% of children in lower-middle-income countries could not read or complete basic maths questions by the end of primary school. There were also major inequalities in access to and achievements in learning, with disparities between rich and poor students beginning early in their lives, widening over time and being compounded by other sources of disadvantage, such as gender, disability and location. For example, between 2010 and 2019, almost half of the countries with data did not achieve gender parity in primary school completion. These inequalities have been exacerbated by the pandemic, which the UN has described as a “generational catastrophe”.

UK commitments and reported results

The UK government has made a range of commitments to global education over the last decade, especially to girls’ education. DFID’s 2013 Education position paper37 outlined three priorities: to improve learning, to reach all children, and to keep girls in school. In 2015, the UK government set a target that, by 2020, it would help at least 11 million children in the poorest countries gain a ‘decent education’ and promote girls’ education.38 In 2015, the UK also committed to help 6.5 million girls in poor countries go to school.39 In 2018, under the Education policy published by DFID, the UK government committed to improving quality and equity in education by focusing on three priorities: investing in good teaching, supporting system reform which delivers results in the classroom, and stepping up targeted support to poor and marginalised children.

In 2020, DFID estimated that it had supported at least 15.6 million children, over half of whom were girls, to gain a ‘decent education’ between 2015 and 2020. In May 2021, FCDO published its action plan for girls’ education, in which it committed to “re-double” its efforts as a champion of education for girls. In 2021, the UK co-hosted a Global Partnership for Education replenishment summit to urge world leaders to invest in getting children into school, and girls’ education was a central theme of the UK’s G7 presidency in 2021.

DFID/FCDO’s education portfolio

DFID/FCDO’s education portfolio is diverse. It involves programmes supported through different channels of aid: bilateral programmes managed by DFID/FCDO in country, bilateral programmes managed centrally, ‘multi-bi’ programmes (where DFID/FCDO channels aid earmarked for education through a multilateral institution), and core contributions to multilateral funds. The delivery architecture for DFID/FCDO’s education portfolio is complex, involving different kinds of implementing partners.

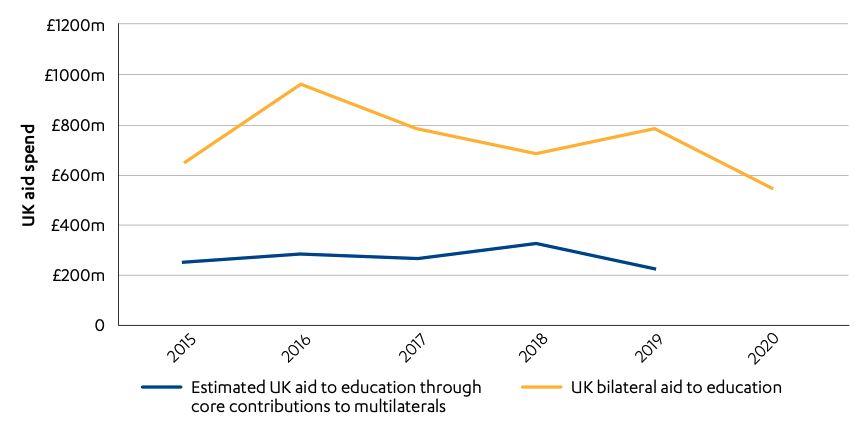

The UK has been a major donor to education and has allocated more of its aid to basic education and to low-income countries than most other donors. The UK spent £4.4 billion on bilateral aid to education between 2015 and 2020, during which time this spending fluctuated from a high of £961 million in 2016 to a low of £545 million in 2020. 117 bilateral programmes spent more than £1 million on basic education between 2015 and 2021. 29 of these were centrally managed programmes, including approximately £60 million through DFID/FCDO’s Research and Evidence Division. The rest were programmes managed through 26 DFID/FCDO country or regional teams. The countries in which DFID/FCDO spent the most on basic education during this period (through bilateral programmes managed by DFID/FCDO in country) included Pakistan, Nigeria, Tanzania, Syria, Ethiopia and Bangladesh. Basic education received the largest share of UK aid to education over the review period (see Figure 5). UK aid to education through core contributions to multilateral organisations was an estimated £1.3 billion between 2015 and 2019.

Figure 4: Amount of UK bilateral and multilateral aid to education since 2015

Source: Statistics on International Development: Final UK aid spend 2020, FCDO, September 2021, link.

Note: 2019 is the latest year with an available estimate of UK aid to education through core contributions to multilaterals.

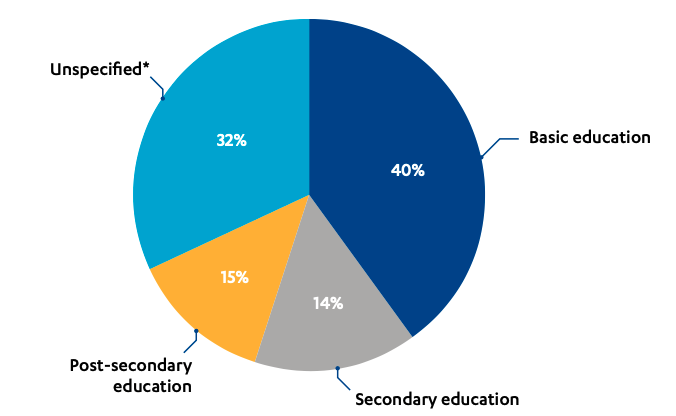

Figure 5: Proportion of UK bilateral aid to different levels of education between 2015 and 2020

Source: Statistics on International Development: Final UK aid spend 2020, FCDO, September 2021, Table A7, link.

* Most unspecified spend consists of contributions to education multilaterals (primarily the Global Partnership for Education) and spending on management, facilities, training and research. Much of this is focused on primary education. See Education policy 2018: Get Children Learning, DFID, 2018, p. 11, link.

Up until 2020,49 DFID/FCDO did not allocate a budget specifically to girls’ education. DFID/FCDO argued in its recent action plan for girls’ education50 that its focus on girls does not mean that it values boys’ education less highly, and that most of its education work supports education as a whole, benefiting boys as well as girls.51 However, much of DFID/FCDO’s education programming has had specific objectives for girls’ education, and some has targeted groups of girls who are marginalised in education because of the way that gender can interact with other forms of disadvantage, such as extreme poverty or disability. Most notably, DFID/FCDO has spent £565 million through the centrally managed Girls’ Education Challenge over the review period, which aims to support marginalised girls. In this review, we have assessed the whole of DFID/FCDO’s basic education portfolio, but with a focus on how girls have been supported through general education programmes and girls’ education programmes.

ICAI’s previous review

ICAI’s previous review of education, published in 2016, focused on marginalised and disadvantaged girls. It awarded DFID an amber-red score, noting a lack of coherence between different UK aid channels addressing girls’ marginalisation in education and a loss of focus on marginalisation during the implementation of bilateral programmes managed in country. In 2018, ICAI’s follow-up of the government’s response to this review noted that DFID had made impressive improvements to address the shortcomings identified. This current review is not a follow-up review. It builds on the previous review but also assesses education results more broadly.

Findings

Effectiveness: How effective is DFID/FCDO aid to education in delivering its intended results?

In this section we set out our main findings on the effectiveness of DFID/FCDO aid to education in delivering its intended results since 2015. We do this through assessing the total results reported across DFID/FCDO’s education portfolio, before presenting more in-depth insights on the effectiveness of the implementation of UK aid to education. Throughout, we make judgements around whether DFID/FCDO met the scale of its own expectations, both for sampled programmes and more broadly.

The UK government reported that it achieved its commitments on the number of children (and girls in particular) supported to gain a ‘decent education’ between 2015 and 2020

As part of its Single Departmental Plan results framework, DFID/FCDO estimated that, between 2015 and 2020, it supported at least 15.6 million children to gain a ‘decent education’. This exceeded the 2015 commitment of at least 11 million children. Of these 15.6 million children, for those results that could be disaggregated by gender, over 50% were girls, which exceeded the commitment DFID made in 2015.

Bilateral programmes managed by DFID/FCDO in country contributed 11.9 million children to these results. Central DFID teams contributed 2.4 million children to these results through centrally managed and ‘multi-bi’ programmes (although, as noted in Figure 6, DFID discounted 0.9 million because of the risk of ‘double-counting’). The biggest contributions to this figure for centrally managed and ‘multi-bi’ programmes came from DFID/FCDO’s support to the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) (1.2 million children), Education Cannot Wait (ECW) (0.5 million children) and the Girls’ Education Challenge (GEC) (0.6 million children).58 DFID/FCDO’s core contributions to multilateral organisations contributed 2.2 million children to these results. Of these, 1.3 million were attributed to DFID/FCDO’s support to the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA).

Figure 6: The breakdown of DFID’s results estimates between 2015 and 2020

DFID/FCDO’s corporate-level results estimation process has been systematic and consistently applied, but may have underestimated the number of children supported in education

DFID/FCDO’s estimate that it supported at least 15.6 million children to gain a ‘decent education’ is based on aggregating results across each of DFID/FCDO’s programmes between 2015 and 2020. It tracks the number of children that were supported in school for at least a year. Where DFID/FCDO was providing at least approximately 75% of funding, all children were counted.61 Where, as is common, DFID/FCDO only provided a proportion of the support for the education of a group of children (measured on the basis of funding shares, data on children’s learning or other relevant data), then only this proportion of the total number of children was attributed to the UK’s support. The figure that emerges from this methodology was referred to by DFID/FCDO as the full-time equivalent number, which it uses so as not to overestimate the number of children supported.

We reviewed this results estimation methodology as it was applied to the sampled programmes and countries. DFID/FCDO used a reasonable methodology and provided staff with clear guidance to promote consistency in applying it. Results estimation across these programmes and countries was consistent with this methodology. DFID/FCDO had thorough systems for quality assurance of the reported results and avoided ‘double-counting’ (such as children being claimed as fully supported by one programme and the same children being claimed as partially supported by another programme). This cautious approach to ‘double-counting’ was the one area where we were not convinced by the accuracy of the results estimation process. In practice, 0.9 million multilateral results (from ECW and GPE) were discounted because they were reported in countries where DFID/FCDO also had bilateral programmes. This was not necessary in cases where both channels could have ‘claimed’ a proportion of results based on their funding contributions, making the 15.6 million result an approximate underestimate (see Figure 6).

FCDO is not yet able to measure or report on its contribution to improving children’s learning globally, but is working to improve measurement in order to do so

The phrase ‘decent education’, adopted in the government’s 2015 manifesto, was in practice understood by officials to mean the provision of quality education. At the time, there was no consensus on comparable global metrics for quality education. DFID/FCDO’s working definition of what counted as quality or ‘decent education’ included results from programmes where they were confident that:

i) quality education was being provided, ii) education quality was being improved, or iii) there was no alternative education provision (for example emergency settings). The results target for the number

of children supported to gain a ‘decent education’ is therefore an indicator of how many children were reached with better-quality education than they would otherwise have received, rather than a measure of how many children were supported to learn effectively. DFID/FCDO has stated that all its education programmes have included a focus on improving the quality of education to raise learning levels. All of the programmes and areas of spending that we assessed were supporting quality improvements. However, DFID/FCDO’s reporting of its education results against its Single Departmental Plan results framework62 did not include information on the quality of education.

Robust evidence of impact on learning is not available for all programmes, although DFID/FCDO is supporting the generation of this evidence (see paragraphs 4.50-4.55 for more detail).

This approach also does not generally capture UK aid’s support beyond its financial contribution, including support to education system reform and building the evidence base for effective education interventions. Indeed, for the countries and programming that we assessed, we found good evidence of DFID/FCDO’s wider contributions to capacity building and systems-level reforms. We describe DFID/ FCDO’s impact on systems strengthening within our findings on impact (see paragraphs 4.61-4.62).

In future, FCDO is planning that its results reporting will be related to the education commitments and targets agreed by the G7 in May 2021, including ensuring that more girls in low- and lower-middle- income countries are in school and learn to read. FCDO staff told us that they are working to find the best ways to measure progress towards these commitments, but that the approach was not yet agreed (see paragraph 4.53). Measuring learning would provide a better measure of how many children DFID/ FCDO has supported to gain a quality education.

DFID/FCDO bilateral and multilateral aid to education has been well implemented over the review period

We assessed whether a sample of UK aid-funded education programmes have delivered their planned activities effectively. We judged that all but one out of 18 met the scale of DFID/FCDO’s own broad expectations, as set out in programme plans, for what they would do to support education. We note that DFID/FCDO’s expectations for its programmes were ambitious, and therefore meeting them indicates a good level of performance. For example, the first phase of GEC aimed to ensure that up to one million marginalised girls completed a full cycle of primary or secondary education. We were unable to judge the effectiveness of DFID/FCDO’s contribution to IDA for education overall due to insufficient reporting as this support is for all IDA’s activity in various sectors.

Box 3: Examples of strong bilateral country programme implementation

Srategic Partnership Agreement II between DFID and BRAC, Bangladesh (£222 million; 2016-2021)

This programme aimed to improve access to quality basic services, including education for the poorest, most marginalised people in Bangladesh. The programme exceeded its targets for education. Students from Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) schools achieved a higher pass rate at in the Primary Education Completion Examination, compared to the national average. The programme overall achieved or exceeded expectations against targets for the number of children enrolled and graduating from BRAC schools and attendance rates. The programme also introduced additional expectations around delivering education to the most disadvantaged groups.

Underprivileged Children’s Educational Programme, Bangladesh (£25 million; 2012-2016)

The programme exceeded its target for ensuring access to school, providing both general and vocational education for children from urban slums. It supported over 44,000 children.

Girls’ Education South Sudan Programme Phase 2 (£70 million; 2018-2024)

In 2019, this programme exceeded its targets for the number of girls it supported in education, reaching nearly 400,000 girls. The programme also exceeded its targets for providing grants to improve the learning environment (for example through providing toilets, educational materials and equipment).

It supported 4,300 primary and nearly 200 secondary schools. The programme also performed well against objectives for improving teaching quality.

The majority of programmes included specific expectations for supporting girls’ education, such as the number of girls reached or support for specific activities, although these were not always met

Most external stakeholders spoke very highly about DFID/FCDO’s success in targeting and supporting girls. For all but one of the programmes that we assessed, DFID/FCDO had set specific expectations for activities targeting girls. Another programme had insufficient information for us to make a judgement. Of the remaining 16 programmes, 12 met the scale of these expectations.

For the bilateral education programmes in our sample, ten out of 13 met their expectations for girls’ education (one did not set such expectations). These expectations varied across programmes and included targets relating to the number of girls attending, developing gender-sensitive approaches to teaching and action to make the learning environment more suitable to the needs of girls. This is an improvement on the situation we found in our 2016 review of support for marginalised girls’ education, which judged that only eight out of the 19 bilateral programmes assessed met DFID’s own expectations around girls’ education.67 While performance for girls has improved, given the priority attached to girls’ education by DFID/FCDO over the review period, we would expect more consistently good performance.

The bilateral country programmes that we assessed performed particularly well in improving the teaching and learning environment for girls, including making education safer and more accessible, and through increasing the gender-responsiveness and inclusiveness of teaching practices. For example, Rwanda’s Learning for All Programme (£96 million; 2015-2023) and the Education Quality Improvement Programme in Tanzania (£89 million; 2012-2021) both introduced gender-sensitive approaches to teaching, leading to more gender-balanced interactions between teachers and pupils (see Box 4).

Performance of targeted support for girls was insufficient overall for two of the older bilateral country programmes that we assessed. In the Bangladesh Education Development Programme (£115 million; 2011-2018), the girls’ education action plan developed under the programme was not implemented effectively. Stakeholders suggested that this may have been due to insufficient commitment from government partners to ensure implementation, monitoring and learning. For the Education Quality Improvement Programme in Tanzania (EQUIP-T) (see Box 4), a secondary school preparedness programme and school clubs designed to support girls were not as successfully implemented as anticipated. Some FCDO staff and external stakeholders felt that further efforts were needed to understand girls’ needs and the barriers to their education and to develop more targeted activity.

Box 4: For DFID’s Education Quality Improvement Programme in Tanzania, the level of achievement for girls was not in line with DFID’s original expectations

At its outset, DFID/FCDO expected that the programme would provide better-quality education, especially for girls, and support 27,500 more girls to make the transition from primary to secondary school. Activities aimed at addressing barriers to girls’ education fell short of DFID/FCDO’s expectations. The secondary school preparedness intervention was not implemented beyond the pilot stage. School clubs became a key approach to tackling barriers for girls in education, but achievement also fell short of expectations, with only about half of schools in the regions where the programme was originally operating having active clubs. The independent evaluation of EQUIP-T did find some evidence that the programme contributed to larger learning gains for girls compared to boys through training for teachers on gender-responsive approaches to teaching.

For GEC, DFID/FCDO’s expectations have not been met. In the first phase (£355 million; 2012- 2017), performance fell short of DFID/FCDO’s own expectations for girls’ attendance and learning and the sustainability of activities supported. Factors hindering performance included projects not understanding which barriers were the most critical in preventing girls from improving their learning or the scale of the needs of the marginalised girls they aimed to reach. The second phase of GEC (£500 million; 2017-2025) has been stronger, including the approach to using the experience of the programme to influence systemic change (see paragraphs 4.34-4.35 for more detail). However, DFID/ FCDO’s own expectations have not been met for learning or achieving projects’ shorter-term goals and the number of the most marginalised girls targeted has been substantially reduced.

The overall performance for girls was lower than expected in partner countries supported by GPE, the largest multilateral partnership programme designed to improve the quality of education systems (£374 million since 2015). DFID/FCDO has recognised that the level of ambition for girls within GPE needs to increase (see paragraph 4.39).

DFID/FCDO has been influential in strengthening multilateral education programming and international education initiatives at a global level

DFID/FCDO has been a leading donor on education globally over the review period, in terms of both financing and policy leadership. The range of bilateral and multilateral channels that DFID/FCDO has used as part of its education portfolio is a strength. Working through multilateral channels has given DFID/FCDO an opportunity to leverage additional funds globally to support girls’ education. It has also increased the reach of DFID/FCDO’s influence, beyond the countries where it works bilaterally.

Our assessments of support to ECW, GPE and IDA show that UK aid has played a strong role in coordinating their activity and influencing their performance at a global level. DFID/FCDO has been a key driver in building ECW’s capability to provide education in emergencies and protracted crises during 2015-20, combining its roles as chair and major financial contributor with providing strong technical support to its functioning centrally. DFID/FCDO has also played an active role in GPE’s governance, including through the head of DFID/FCDO’s Children, Youth and Education Department sitting on the board. DFID/FCDO has influenced IDA to increase its focus on inclusive education, quality and learning. In addition, through contributions to trust funds and other World Bank activities linked to IDA’s education portfolio, DFID/FCDO has funded technical assistance which has supported implementation of IDA’s evolving policy commitments on education.

There are some areas where multilateral education programming that DFID/FCDO has supported has not met DFID/FCDO’s own expectations, particularly around the quality of education sector plans that GPE supports and coherence between GPE and ECW

GPE’s theory of change assumes that the national education sector plans which it supports countries to develop and deliver will lead to impact around improved and equitable learning. However, these plans, which are a key building block in strengthening education systems, continue to be overly ambitious and unachievable. Improvements to the extent that these plans were assessed as achievable have not met DFID/FCDO’s expectations. The recent independent evaluation of GPE also concluded that its effectiveness around education sector plan implementation and its subsequent contribution to more effective and efficient education systems remains a challenge.

Internal and external stakeholders also pointed out that there is a lack of coherence between the multilateral programmes that DFID/FCDO has supported, including competition between ECW and GPE in support for education in crisis situations. They thought that FCDO should have a stronger role in addressing this.

The presence of knowledgeable education advisers has enabled the effectiveness of bilateral and multilateral channels in partner countries, supported by investment in evidence building

Both internal and external stakeholders, including in the six countries we assessed, recognised DFID/ FCDO’s contribution to education as being high-quality. They frequently referred to the technical expertise of its staff and its strong reputation for research and using evidence. They also commonly noted that the in-country presence of highly knowledgeable education advisers, with good understanding of the local political economy, enabled DFID/FCDO to be effective in influencing partner governments and donors and supporting capacity building for system reforms. One senior FCDO stakeholder summed this up, describing “staff with fantastic relationships of trust and confidence with ministers in partner countries that help leverage the financial help given”.

We also found that DFID/FCDO in-country staff have helped to promote the effectiveness of the investment it makes in the multilateral programmes that we assessed. As well as shaping GPE’s work globally, DFID/FCDO has often had a highly influential direct role in GPE in the countries where it has an education adviser. This is either through DFID/FCDO being the grant or coordinating agent for GPE programming, or because it designs bilateral programmes to work alongside GPE.

In Zimbabwe, for example, where DFID/FCDO has acted as coordinating agent for GPE, in-country education staff engaged with stakeholders including donors, government and civil society organisations to facilitate constructive sector dialogue. They helped to galvanise activity on the priorities of the education sector plan. In Tanzania, external stakeholders told us that DFID/FCDO has played a substantial role in aligning GPE with other donor and national government investment in education, which among other things has contributed to improvements in education information management systems, learning assessments and plans for teachers’ continuing professional development. We heard similar stories in Bangladesh, South Sudan and Syria.

Of the three assessed countries that received IDA funding for education during the review period, DFID/FCDO’s efforts to influence relevant programmes were particularly successful in Rwanda and Tanzania, but less so in Bangladesh. In Tanzania, a range of external stakeholders noted that DFID/FCDO had influenced the success of the multi-donor Education Programme for Results, particularly through funding independent verification of results and technical assistance to strengthen government systems. In this way, DFID/FCDO has positively influenced the effectiveness of GPE and World Bank IDA money channelled through this programme, as well as DFID/FCDO’s bilateral funding to it. While the World Bank has expertise in basic education, they are relatively new partners in the sector in Rwanda, and FCDO has been key in leading and coordinating IDA spend.

Box 5: Strengthening aid to education in Bangladesh via in-country presence

UK aid has supported the multi-partner75 Bangladesh Primary Education Development Programme (PEDP-3) to improve access to school and drive up the quality of learning, including for marginalised children. It was supported by DFID bilaterally via the Bangladesh Education Development Programme (BEDP, £115 million; 2011-2018) as well as multilaterally through the UK’s contributions to IDA and GPE. DFID/FCDO staff co-chaired two PEDP-3 technical working groups on quality and inclusion, and influenced other donors supporting the programme through chairing the formal donor education consortium. Through these and other roles, DFID/FCDO staff were influential in shaping the success of the programme. In particular, DFID/FCDO staff used their expert understanding of marginalisation issues to advocate for addressing the challenges faced by children with disabilities. As a result, BEDP under PEDP-3 enrolled 96,000 children with disabilities, constructed infrastructure to help them access school and improved the learning environment for them.

Conclusions on effectiveness

DFID/FCDO’s estimation of its results on the number of children it supported to gain a ‘decent education’ across its education portfolio was systematic and reasonable. The figure produced represents an estimate of how many children were supported to go to school and get a better-quality education than they otherwise would have done. However, DFID/FCDO is not yet able to measure its aggregate results around children’s learning globally, which would provide a better measure of how many children it had supported to gain a quality or ‘decent education’. We return to the need for FCDO to better measure learning in the section of our findings on impact.

DFID/FCDO bilateral and multilateral aid to education has been well implemented over the review period. The presence of knowledgeable and politically informed DFID/FCDO education advisers in partner countries has contributed to the effectiveness of bilateral and multilateral channels, supported by investment in evidence building. Its programmes have met the ambitious expectations that it set for itself. However, not all programmes have done as much as DFID/FCDO set out to do for girls. In particular, for two of the older bilateral programmes, some interventions for girls were not sustained. DFID/FCDO has been influential in strengthening the quality of multilateral education programming but one area where multilateral performance has not met DFID/FCDO’s own expectations is around the quality of education sector plans supported by GPE. We therefore award a green-amber score for effectiveness.

Equity: To what extent are DFID/FCDO’s education interventions reaching the most marginalised?

In this section we set out our main findings on the extent to which DFID/FCDO aid to education has reached the most marginalised children since 2015. Throughout, we make judgements around whether DFID/FCDO met the scale of its own expectations on support for marginalised children, either for particular programmes or more broadly.

DFID/FCDO has committed to reaching the most marginalised children, has implemented programming relevant to their needs (especially for marginalised girls) and has been seen as a global leader in this area

Over the review period, DFID/FCDO has been seen by external stakeholders as a global leader on addressing inequalities in education, especially for marginalised girls. DFID’s 2013 Education position paper76 identified reaching marginalised children as a priority. However, the previous ICAI review on marginalised girls’ education, which covered the period between 2011 and 2015, identified the lack of a clear strategic approach on UK support for marginalised girls’ education, creating challenges for promoting coherence and complementarity across the various strands of DFID’s work.77 DFID’s response to this recommendation was positive. In particular, its 2018 Education policy provided a clearer direction for education programming to focus on marginalised groups, particularly hard-to-reach girls, children with disabilities and children affected by crises.79 DFID/FCDO staff thought that this had led to an organisational shift in the extent to which the department’s education programmes aimed to take marginalisation into account during their design and implementation.

Our high-level review of DFID/FCDO programming found that, of those programmes that had spent at least £1 million on basic education since 2015, 80% had some element of targeted activity for girls, 36% for children with disabilities and 43% for children affected by crisis or conflict. For the programmes that we assessed in detail, activities targeting children with disabilities most commonly included support to staff around identifying and meeting the specific needs of these children. For example, the Syria Education Programme (£63 million; 2017-2022) trained school staff to identify children’s physical and learning needs and provide tailored support. Other relevant activities included making school infrastructure more physically accessible and communicating information on the value of education. For the assessed programmes, activities addressing the needs of marginalised girls included training on gender-sensitive teaching, promoting school-level policies for making education more suited to girls’ needs, addressing financial constraints and tackling negative perceptions about the value of education. For example, the Learning for All programme in Rwanda included support for girls’ education policy development. The Girls’ Education in South Sudan programme (£61 million; 2013-2021) included a behaviour change communications campaign to promote knowledge about the value of education for girls.

Box 6: The barriers to education for marginalised groups

Our literature review documented the barriers to education faced by the marginalised groups that DFID/ FCDO has prioritised. Through our citizens’ voice research, we heard from children experiencing some of these barriers.

For hard-to-reach girls, common barriers include a lack of safety on the way to and within school (in particular from gender-based violence), inadequate menstrual hygiene management facilities in schools, attitudes to gender roles, unsupportive views from the community and poverty.

One of my friends wants to study, but her parents said, ‘What would a girl do after studying?’ and forced her to get married. She is only 16.

Secondary school pupil, Bangladesh

There are some chores that only we girls do such as cooking tea for staff and cleaning the classrooms. Even at home these types of chores are only done by girls.

Secondary school pupil, Tanzania

Sometimes I miss school because I am on my period and I could not go school because I know the toilets are in very poor condition and so I decide to stay at home.

Secondary school pupil, Tanzania

Many girls have got pregnant because they live far [from school] and walk on foot, so they become vulnerable.

Secondary school pupil, Tanzania

Nowadays, Eve teasing* happens less than earlier, but when we have exams or extra classes, we leave our school late, and it happens sometimes. We ignore it, but when it became harsh, we try to get support from some senior passer-by.

Secondary school pupil, Bangladesh

* Eve teasing is a euphemism used for public sexual harassment or sexual assault of women by men.

For children with disabilities, common barriers include inaccessible school infrastructure and transport, attitudes towards educating children with disabilities and curricula and approaches to teaching that are not adapted to their needs.

There are a few parents who have disabled children who tend to hide them and would not let them come to school.

Secondary school pupil, Tanzania

There are some children that treat [children with disabilities] poorly. They despise them.

Primary school pupil, Tanzania

It is tough for those with disabilities because they are obliged to use motorcycle drivers [to get to school].

Secondary school pupil, Tanzania

Disabled children are also treated the same but facilities to support them to study and move around are missing.

Primary school pupil, Tanzania

For children affected by crises, common barriers include destruction of infrastructure and the disruption of education services, insecurity, psychological trauma, medical needs and poverty.

DFID/FCDO has been successful in reaching highly marginalised children through its aid to education, although we cannot determine the scale of success globally for children with disabilities

For children affected by crises, all six programmes assessed that targeted this group met DFID/FCDO’s expectations. DFID/FCDO judged that its support to ECW for education in emergency situations has been implemented as planned. Since its inception in 2016, the fund has reached an estimated 4.6 million children and adolescents in conflict-affected countries and countries hosting large numbers of refugees, including Syria, Chad, Bangladesh and Uganda. In Syria, the bilateral Syria Education Programme has exceeded DFID/FCDO’s expectations and is on track to reach nearly 500,000 children. Under the first phase of GEC, three-quarters of girls reached were in fragile and conflict-affected states, including Afghanistan and Somalia. In Somalia, GEC is addressing educational barriers for girls in conflict-affected areas including the burden of household chores, early marriage and a ‘no return to education’ policy for pregnant girls. Feedback was generally positive from both internal and external stakeholders on DFID/ FCDO’s work in conflict-affected zones.

For children with disabilities, of the 11 programmes that we assessed where DFID/FCDO programme plans outlined expectations around children with disabilities, eight met the scale of these expectations. Six of the programmes that we sampled had no expectations around children with disabilities and for one, we had insufficient information to make a judgement. However, while DFID/FCDO has tracked and reported on how many girls it has reached globally (at least 8.2 million girls), and how many of the children reached lived in fragile states (10.8 million children, including 3.6 million living in extremely fragile states81), it has not tracked and reported on its aggregate reach for children with disabilities.

Our country assessments and citizens’ voice research also provided clear examples of where DFID/ FCDO has reached highly marginalised children. For example, the ECW Bangladesh Multi-Year Resilience Programme has provided support to Rohingya children in refugee camps. GEC has also supported many marginalised girls, but it has fallen short of DFID/FCDO’s ambitions on reaching the most marginalised. The reach of the GEC ‘Leave No Girl Behind’ funding window was scaled back dramatically, from an original expectation of 500,000 to 190,000 marginalised girls, in part due to DFID/FCDO realising the cost of meaningfully supporting the most marginalised.

The performance of GEC in supporting marginalised girls has improved since its first phase, including on influencing systemic change

DFID intended that the first phase of GEC (which ran between 2011 and 2017) should have a transformative effect, leveraging support for marginalised girls’ education from other donors and country governments, and demonstrating sustainability, particularly through working with governments. In our previous ICAI review on marginalised girls’ education we concluded that for this first phase of GEC, impact was generally limited to the girls who were reached directly, rather than via changes to education systems, and that little attention was given to the sustainability of the interventions. This first phase was also weak on using GEC learning to influence policy and programme decisions, both across DFID and with wider stakeholders.

For the second phase of GEC (2017-2025), DFID expected that projects would focus on securing buy-in from national stakeholders, including partner governments, to addressing educational challenges for marginalised girls. The ICAI follow-up of our previous review in 2018 found that the GEC fund manager had increased GEC’s country-based capacity and that DFID had created new regional adviser positions to help ensure that GEC learning informed wider policy and programming, and that GEC and DFID’s bilateral programming was more coherent.

For this review period, in all three of our six assessment countries where GEC has been operational, we found evidence of GEC projects influencing other DFID/FCDO programming and the activity of governments and other stakeholders. For example, in Zimbabwe, GEC project implementers engaged regularly with DFID/FCDO as well as with other stakeholders in sector coordination groups. Facilitated by FCDO, GEC implementers also brought in technical advice to the Ministry of Education on the country’s COVID-19 catch-up strategy and had learning materials for self-study that they produced during the pandemic approved by the Ministry for use on a larger scale. FCDO and external stakeholders confirmed that the way in which GEC has been operating in supporting national education systems has improved over the review period. However, weaknesses remain, including in putting in place a system for planning and tracking progress on implementing activities to promote lasting change.

DFID/FCDO’s focus on children with disabilities in its programming has grown over the review period, although ministerial focus on this issue has declined

The 2018 ICAI review on DFID’s approach to disability in development assessed DFID’s work in five sectors, including education. It found that education was the most advanced of these sectors in terms of the likely effectiveness of programming in addressing disability inclusion aims. In this review, across the programming that we assessed, the degree of focus on children with disability varied, but there were examples of strong focus in this area (see Box 7) and we observed a trend of increasing focus on children with disabilities in this programming.

Box 7: The Phase II Education Development Fund for Zimbabwe (£59 million; 2012-2019) had a strong focus on children with disabilities

This programme trained over 80,000 Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education personnel to understand and support education of children with disabilities. It sensitised 28,790 community members to send their children with disabilities to school. It also provided more funding to special schools serving children with more complex needs.

However, our interviews with internal and external stakeholders indicated a more cautious narrative on DFID/FCDO’s progress on addressing disability in education. While some felt that there has been a continued interest in children with disabilities over the review period, a larger number felt that this has seen reduced prioritisation by UK ministers. For example, a few civil society stakeholders suggested that the UK government could have been more active in using the 2021 G7 summit and the most recent GPE replenishment to promote the educational needs of children with disabilities. In addition, centrally managed disability programming has not been as successful as hoped.

We have students with mild disabilities but can’t enrol students who need special care because they need specialised support that our teachers are not trained to provide. However, we do accept students with physical disabilities because they can learn easily, they just need some assistance.

Headteacher, Bangladesh

Many internal and external stakeholders conceded that addressing educational inequalities for children with disabilities in developing countries is challenging, given that these children face significant barriers and there is a lack of data to support efforts to identify and address their needs. For example, in Tanzania, stakeholders within and outside FCDO were clear that DFID/FCDO has emphasised the importance of inclusion of disabled children, highlighting relevant DFID-funded technical assistance and the successful production of an inclusive education strategy by the Tanzanian government. However, they also commonly acknowledged that this area is “work in progress”, due to the scale of the challenge and given resource constraints.

DFID/FCDO has made progress in influencing multilateral organisations to focus on the most marginalised, but more progress is needed

FCDO staff told us that DFID/FCDO has been pushing GPE to do more on gender equality and that some progress has been made. GPE reported that its implementation grants approved between 2016 and 2020 allocated 30% of funds, or $640 million, to activities specifically promoting equity, gender equality and inclusion, with $147 million allocated to activities exclusively promoting gender equality.87 However, the recent independent Summative Evaluation of GPE88 concluded that the operationalisation of GPE’s own internal gender equality strategies and plans, in particular at the country level, is only at an early stage. Similarly, FCDO has itself judged that the level of ambition of GPE investments to improve the inclusion and learning of marginalised children, especially girls and children with disabilities, still needs to increase.

Internal and external stakeholders informed us that DFID/FCDO has helped to promote a recent shift among donors towards focusing more on education in emergencies, including through its influential role in establishing and promoting ECW. We also found that DFID/FCDO has supported the development of ECW’s institutional strategy, and that in-country staff have supported the tailoring of ECW in different country contexts. However, our country assessments in Bangladesh, South Sudan and Syria presented more mixed evidence of the success of ECW on the ground, particularly in Syria where there are weaknesses in its coherence with wider education programming. At the end of the first phase of DFID support to ECW (implemented between 2016 and 2019), DFID/FCDO concluded that, despite the support it had provided around gender (including for the development of ECW’s Gender Strategy), ECW still needs to enhance its focus on inclusion and gender equality in programming.

DFID/FCDO’s substantial contributions to IDA89 have ensured influencing power. DFID/FCDO is recognised by other donors as a strong advocate for inclusive education and a focus on learning outcomes. FCDO staff thought that the increased focus on education and marginalised groups in successive IDA replenishments can be partly attributed to DFID/FCDO influence.

A number of aspects of the way DFID/FCDO has worked have enabled programmes to reach marginalised groups

One factor that has helped DFID/FCDO to reach highly marginalised children has been effective partnership with implementing partners who already had good community outreach to the most marginalised. For example, GEC projects run by Camfed in Tanzania have been highly relevant to the needs of marginalised girls, including through providing social support and guidance, informed by the way Camfed draws on the understanding of local people in implementing its projects. For example, Camfed supports some young women who have completed school to work as ‘learner guides’ in their communities, providing peer support and a link between home and school.

Other factors enabling DFID/FCDO to reach marginalised children include having staff in country with good contextual knowledge, as well as having effective internal mechanisms to promote equity in programming, including equity now being a key component of value for money assessments.

Conclusions on equity

DFID/FCDO has had some success in reaching highly marginalised children through its aid to education, although we cannot determine the scale of overall success for reaching children with disabilities. DFID/ FCDO is seen as a global leader in using its aid to provide education for marginalised girls.

The performance of GEC in supporting marginalised girls has improved since the first phase of GEC, including around influencing systemic change. DFID/FCDO’s aid to education has reached children affected by conflict and humanitarian disasters effectively through various channels. Its focus on children with disabilities in its programming has grown over the review period.

DFID/FCDO has made progress in influencing multilateral organisations to focus on the most marginalised, but more progress is needed. In particular, GPE’s level of ambition in promoting the inclusion and learning of the most marginalised still needs to increase. We therefore award a green-amber score for equity.

Impact: To what extent is DFID/FCDO achieving sustainable impact through its aid to education?

In this section we set out our main findings on the extent to which DFID/FCDO has achieved sustainable impact through its aid to education since 2015. While the section on our findings around effectiveness considered whether programming has been implemented as intended to support children to gain an education, this section considers the extent to which it has made a difference to children’s progress in learning. DFID/FCDO’s approach to promoting sustainable impact through its aid to education involves support for developing teachers’ skills, efforts to build capacity and strengthen education systems, as well as the generation of evidence to promote best practice. However, sustainable impact will require continued resourcing beyond DFID/FCDO programmes, from governments and others, therefore this section also looks at how effectively the UK has leveraged resources for education from others. Finally, it presents some reflections on how the UK has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and the implications of budget reductions for aid to education for sustaining the impact that DFID/FCDO has achieved. Throughout, we make judgements around whether DFID/FCDO met the scale of its own expectations in planning documents, either for particular programmes or more broadly.

The challenge of the ‘learning crisis’ that DFID/FCDO has aimed to address is substantial