Blue Planet Fund

Executive summary

Launched in June 2021, the £500 million Blue Planet Fund is the UK government’s main vehicle for official development assistance (ODA) to help developing countries protect their marine ecosystems and reduce poverty through the sustainable management of the ocean and its resources. The Fund forms part of the UK government’s broader commitment to provide £11.6 billion in international climate finance (ICF) to support developing countries’ efforts to address climate change, of which at least £3 billion will be invested in efforts to protect nature.

The Blue Planet Fund is jointly managed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), with Defra the strategic lead and delivering the largest portion of the Fund. Investments are made in four thematic areas: marine biodiversity, climate change, marine pollution, and sustainable seafood. Defra started the five-year delivery of its £310 million majority share of the Fund in 2021, while FCDO only began delivering its £190 million share in 2023. The two departments had, as of November 2023, allocated more than 90% of the Fund to programmes.

This review assesses the Fund’s relevance to the needs of developing countries; how well Defra and FCDO coordinate the Fund’s delivery; and whether it has the governance arrangements, systems and procedures in place to allocate its funds to help developing countries protect the marine environment and reduce poverty.

Findings

Relevance: How relevant is the Blue Planet Fund to developing country needs as part of meeting the UK’s international climate finance objectives?

The Blue Planet Fund represents a significant increase in the UK’s contribution to tackling key marine issues and supporting the globally underfunded UN Sustainable Development Goal 14 “to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”. The majority of the Fund’s spending is counted as ICF and falls under the International climate finance strategy pillar ‘nature for climate and people’. For programme spending that is counted as ICF, the Blue Planet Fund is required to collect and report results against at least one of the ICF key performance indicators (KPIs). The Fund’s own KPIs remain in draft form, with three of its draft indicators mapping to five ICF indicators.

The Blue Planet Fund is centrally managed, and its design suffered from a lack of adequate consultation on country and regional needs, both in assembling its list of priority countries and in how funding is apportioned across those countries. Some of Defra’s allocations were to programmes that were already established or in the pipeline and were re-assigned to the Fund. The department took this approach to launch the Fund before the UK government hosted two major international summits in 2021: the G7 and the international climate conference COP26. However, by choosing to scale up, adapt, merge or rename ongoing activities, the department limited opportunities to design a Fund portfolio primarily focused on countries with the greatest needs.

Coherence: How coherent and coordinated is the Blue Planet Fund within and across the two departments (Defra and FCDO)?

FCDO started delivery of Blue Planet Fund programmes two years after Defra, because it was the department which absorbed the majority of the aid budget reductions owing to COVID-19’s impact on the economy and the UK government’s decision to reduce its ODA spending commitment. This staggered timeline has, in our opinion, impeded the coherence of the Fund. By prioritising the quick launch of the Fund, Defra’s funding allocations were made before key management processes were in place. The Fund has emerged as a collection of programmes rather than a jointly managed and coherent fund. Defra and FCDO each lead on different strategic outcomes as set out in the Fund’s delivery framework. However, in practice there is both overlap between the two departments’ activities and gaps in delivery against some strategic outcomes.

While coordination between the Fund and the departments is guided by the delivery framework, there is no apparent overarching strategy. With different timelines across two departments and the seven different outcome areas, the burden falls on the overarching theory of change to provide a strategic framework for delivering development results through the Fund. The theory of change has just been refreshed and expanded to include underlying theories of change for each priority outcome.

Core management functions are not in place two and a half years after the Fund’s launch. This includes a portfolio-level monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) framework and KPIs which remain in draft form.

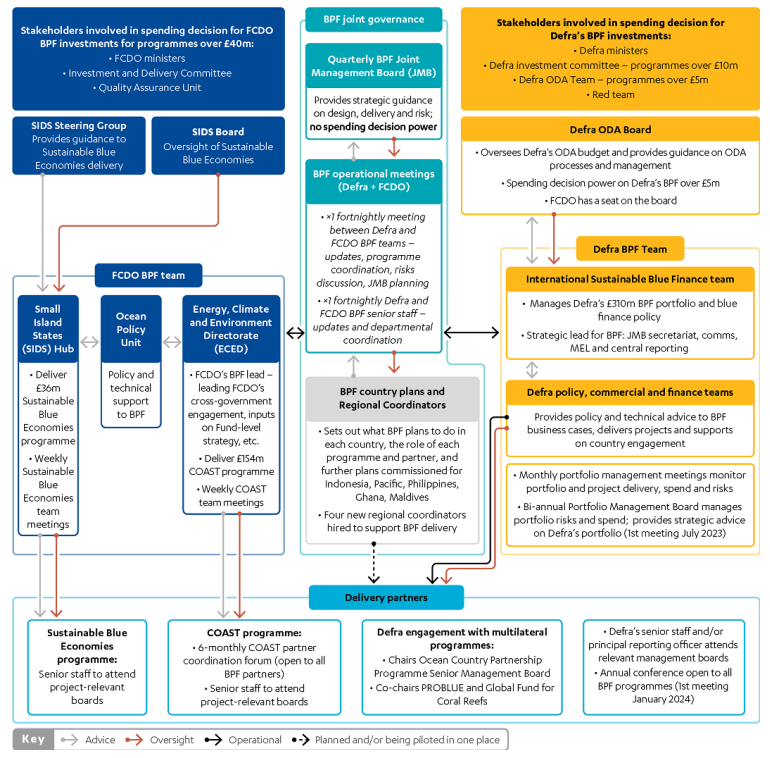

There is a complex governance, oversight and delivery management framework, but we found important gaps in oversight of the Blue Planet Fund. The two departments work together under the oversight of the Joint Management Board (JMB), which holds quarterly meetings. The JMB provides strategic guidance on design, delivery and risk but does not have spending decision authority. As is standard practice across the UK government, Defra and FCDO are each accountable for their own expenditure and each department has its own internal approval processes. The Defra ODA Board oversees all of the department’s ODA budget, including its Fund programmes. FCDO has a representative on the board, but there is no representation from Defra in FCDO’s internal approval process.

Although most of the Blue Planet Fund is earmarked as international climate finance (ICF), neither the ICF Management Board nor the ICF Strategy Board have had oversight of the Fund since its inception as part of the strategic implementation of the ICF. When the JMB recently identified several “severe” risks (similar to the weaknesses in coordination and oversight of delivery identified in this review) across the Fund, these were not discussed at the ICF Management or Strategy Board. That is, there is no effective cross-government oversight to ensure that, once flagged, such risks are adequately and urgently addressed.

Meanwhile, there has been a lack of coordination at country level, between the two departments and between their delivery organisations, with limited communication around portfolio opportunities or consideration of how different programmes fit together or with other programming in-country. There have been cases where FCDO staff at High Commissions or embassies were not informed about planned activities or about a visit by Fund delivery teams to the country. To improve coherence and coordination of Blue Planet Fund delivery, the Fund has recently appointed four of five planned regional coordinators to support stakeholder engagement and delivery at the country level. The Fund is also developing country plans, of which the one for Mozambique is the most advanced and is awaiting formal sign-off from the country’s government. Five other country plans have been recently commissioned and are under development.

Effectiveness: Are the systems, controls and procedures of the Blue Planet Fund adequate to ensure effective programming and good value for money?

The Fund decisions on programme selection are guided by a list of priority countries and a set of ten Blue Planet Fund investment criteria. Contributing to efforts to reduce poverty is a statutory requirement for UK ODA. The Fund’s investment criteria for programme scoping were finalised in February 2021. We are concerned that assessment of the poverty reduction potential is only one of ten weighted criteria, used in a two-stage process, which makes the assessment of this programme aspect less significant. Many concept notes and some of the business cases reviewed had not provided adequate assurance that the programme would contribute to poverty reduction. The lack of evidence on poverty reduction potential has been recognised by FCDO’s COAST programme, which seeks to strengthen this evidence base.

Gender is not included as one of the Fund’s investment criteria but is included under the criteria of poverty reduction potential and ‘do no harm’. There is significant variation in the level of attention paid to gender in programming. Some business cases make only passing references to promoting gender equality, while others have gender-focused activities and KPIs.

The design and delivery of FCDO’s programmes are governed by the Programme Operating Framework (PrOF). Defra has a relatively new but growing ODA hub team. In May 2023, Defra streamlined and combined guidance from FCDO’s PrOF and other material, including Cabinet Office and Defra’s own material, into a new operating manual.

There are important weaknesses in Defra’s management of some of its delivery partners. In the case of Defra’s arm’s-length bodies that deliver its Ocean Country Partnership Programme (OCPP), investments have been disbursed without a completed memorandum of understanding (MOU). As of 30 October 2023, there is a signed MOU in place. The arm’s-length bodies charge high overheads ranging from 15% to 37% – much higher than the norm for the delivery of ODA-funded activities, with UN agencies, for instance, charging 4% to 12%. The high management costs involved in Fund delivery chains raise the question of how much UK ODA in fact reaches the recipient countries. It is hard to identify a coherent approach to value for money for the Defra portion of the Fund, given its lack of due diligence and adequate supervision of some of the delivery partners. Defra informed us that a new governance structure and payment arrangements are being put in place for OCPP to ensure that future payments are made in line with the agreed and costed programme of work at the beginning of each financial year.

The Blue Planet Fund lacks an effective system for tracking its overall results, without portfolio-level MEL arrangements in place, with only draft Fund KPIs, and with only some reporting of the Fund’s programmes towards the ICF KPIs. Without these in place, a major challenge the Fund will face in the future will be how to demonstrate its impact and value for money. Weak communication is also inhibiting effectiveness as there is limited information about the Fund and how it functions publicly. Officials recently updated the Blue Planet Fund GOV.UK page with a list of programmes, which somewhat increases visibility. A communications plan is currently under development. Increased transparency would support stronger accountability and engagement with developing countries.

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations to the UK government on how to improve the Blue Planet Fund.

Recommendation 1: As the strategic lead for the Blue Planet Fund, Defra should put in place formal core central management functions, including results management and reporting systems to enable the Fund to demonstrate impact and value for money.

Recommendation 2: Given the major risks identified by this review, cross-government oversight of the Fund should be strengthened.

Recommendation 3: The Fund should ensure that poverty reduction, as the statutory purpose of UK aid, is the primary focus of its programming.

Recommendation 4: Defra and FCDO should ensure that governments and other national stakeholders in the countries where the Fund operates are empowered to shape programmes by creating formal channels for them to communicate their priorities and needs.

1. Introduction

1.1 In January 2021, the UK government announced plans for a new £500 million Blue Planet Fund with the aim of supporting developing countries to protect the marine environment and reduce poverty. The announcement was made as part of a commitment to invest at least £3 billion in development solutions that protect and restore nature within a broader commitment to spend £11.6 billion on international climate finance (ICF) by the financial year 2025-26.

1.2 The Blue Planet Fund was launched in June 2021 with a timespan of at least five years. It is jointly managed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), with Defra as the strategic lead. It is one of several cross-government funds created in recent years to target development challenges while drawing on the expertise available across the UK government.

1.3 As the main vehicle for UK official development assistance (ODA) support for protecting the marine environment and reducing poverty, the Fund is of considerable public interest. Oceans and marine habitats are fundamental to maintaining the planet’s health and addressing critical challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss. They are also key to sustainable development as marine resources form the basis of a significant portion of the global economy, supporting sectors such as tourism, fisheries and international shipping.

1.4 Oceans play a critical role in the global climate and hydrological systems. They regulate worldwide temperatures, generate a minimum of 50% of the Earth’s oxygen and absorb approximately 25% of carbon dioxide emissions. Addressing climate issues hinges on maintaining a thriving and healthy ocean.

Box 1: The Blue Planet Fund and Sustainable Development Goals

The UN Sustainable Development Goals, also known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure all people enjoy prosperity and peace. The Blue Planet Fund directly supports Goal 14, on ocean protection and sustainable management, and relates to Goal 13 on climate action.

![]() Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.

Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.

![]() Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts – including building resilience and capacity to adapt.

Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts – including building resilience and capacity to adapt.

1.5 Oceans support the livelihoods, food security and economies of many countries and their populations, including developing countries. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the UN, more than three billion people, primarily in developing countries, rely on ocean resources for their livelihoods, especially in industries such as tourism and fisheries. According to the World Bank, the ocean’s annual contribution to the global economy amounts to $1.5 trillion and is projected to reach $3 trillion by 2030, marking a doubling of its current impact on the global economy. Oceans are also a source of nutrition, especially high-quality protein, for individuals in low-income coastal countries.

1.6 Despite their critical significance, oceans face unparalleled challenges which impact livelihoods and biodiversity. Climate change is causing harm to vital marine ecosystems such as coral reefs and mangroves as sea levels rise and oceans get warmer. Overfishing, meanwhile, jeopardises the stability of fish and marine life populations.

1.7 Three years after the Blue Planet Fund was announced, this rapid review examines the Fund’s establishment and development. It assesses (i) the relevance of the Blue Planet Fund through an analysis of governing policies and strategies, paying particular attention to how the Fund responds to developing country needs as part of meeting the UK’s wider international climate finance objectives; (ii) the coherence of programme delivery within and between the two responsible departments; and (iii) whether it has the governance arrangements, systems and procedures to allocate its funds effectively in support of its objectives.

1.8 The review questions are set out in Table 1. We have not attempted to make judgments on the effectiveness of the Fund’s individual programmes. However, as the Fund has already approved more than 90% of its budget, it is appropriate to review its design and work to date and to make suggestions for its continuing development. As with other ICAI rapid reviews, we do not provide a performance rating but offer a number of recommendations to assist in the continuing improvement of the Blue Planet Fund’s operations.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions |

|---|

| Relevance: How relevant is the Blue Planet Fund to developing country needs as part of meeting the UK’s international climate finance objectives? |

| Coherence: How coherent and coordinated is the Fund within and across the two departments (Defra and FCDO)? |

| Effectiveness: Are the systems, controls and procedures of the Blue Planet Fund adequate to ensure effective programming and good value for money? |

2. Methodology

2.1 This rapid review of the Blue Planet Fund was originally commissioned in April 2023 as an information note but was converted to a rapid review in July 2023. The review methodology has three main components to gather evidence against our review questions and ensure sufficient triangulation of findings. For each component, evidence-gathering and analysis took place in two stages: a first stage within the work on the planned information note, followed by a second stage once it was decided to develop the report into a rapid review. The components are explained below.

2.2 Our methodology combined the following elements:

- Strategic review: We reviewed documentation on the establishment and operations of the Fund, including relevant policies, strategies, frameworks, and coordination mechanisms. We also reviewed wider strategies and key documents on the funding approach at portfolio and programme levels, and results management.

- Key informant interviews: We interviewed staff working for the Fund in the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). Interviews covered the Fund’s direction and operations including strategy, governance, and management processes; funding decision-making including approval processes, procurement, and contracting processes; the Fund’s results management; and the shape and coherence of the Fund’s emerging portfolio. Coherence across departments and countries was also considered.

- Country case studies: We examined the Fund’s relevance, effectiveness and coherence through its investment and programming in two developing countries – Fiji and Mozambique. This involved reviewing relevant country and programme documents and conducting virtual interviews with delivery partners in the two countries as well as UK staff in-country to triangulate data. Fiji and Mozambique were selected based on the following criteria: regional diversity, a high number of relevant programmes and a good balance between bilateral and multilateral spend.

2.3 We reviewed more than 500 documents from the two departments and other key stakeholders including delivery partners and UK government staff in-country. We interviewed a total of 44 key informants in the UK, Fiji, Mozambique and Indonesia.

Box 2: Limitations to the methodology

- Scope: The scope of this review covers the Fund-level operations, governance, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of the Blue Planet Fund. The individual programmes were not evaluated but are reviewed to inform how the Fund works as a whole.

- Timing: Our findings cover the period until November 2023. Nine-tenths of the Blue Planet Fund has been allocated to programmes via approved business cases but spending is still at less than one-fifth. Our findings therefore reflect the relatively early days of the Fund expenditure. Defra plans to spend until 2027, while FCDO plans to spend until 2030.

3. Background

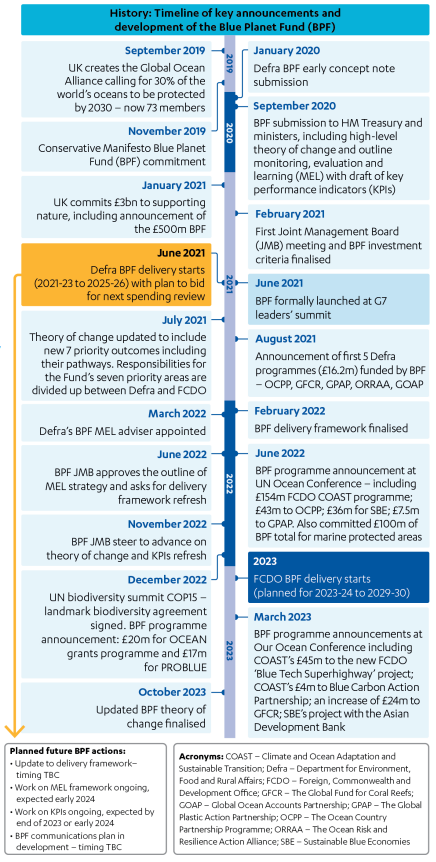

Figure 1: Timeline of the Blue Planet Fund

3.1 The UK government heralded 2021 as a pivotal year for the ocean and sought to assist international leadership on ocean issues through its role as host of both the G7 and the Glasgow international climate conference, COP26. The UK government also brought marine conservation to the forefront of discussions at events such as the UN biodiversity conference (COP15) and supported the initiation of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (Ocean Decade). The £500 million Blue Planet Fund was announced in January 2021 and launched by the then prime minister Boris Johnson at the June 2021 G7 leaders’ summit. It was intended to underpin the UK’s global leadership on the issue.

Evolution of the Blue Planet Fund

3.2 The Blue Planet Fund is categorised as 100% official development assistance (ODA). It supports developing countries to protect and enhance marine ecosystems and reduce poverty through the sustainable management of ocean resources. The Fund’s four thematic areas are: marine biodiversity, climate change, marine pollution, and sustainable seafood.

3.3 The Fund supports the delivery of the UK government’s Integrated review, which puts tackling climate change and biodiversity loss at the heart of the government’s international priorities, and the 2022 Strategy for international development, which positions climate change and biodiversity as the UK’s ‘number one’ international priority. The Fund contributes to a range of commitments made by the UK in recent years. It is key to the UK commitment to protect at least 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030 (the 30by30 target) as part of the Global Ocean Alliance, a 77-country-strong group led by the UK. It champions ambitious ocean action with the Convention on Biological Diversity including the 30by30 target. It also contributes to the UK commitment to the Commonwealth Clean Ocean Alliance, a UK and Vanuatu led Commonwealth initiative to stop plastic pollution entering the ocean. It supports delivery of the December 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 203014 and aims to advance Sustainable Development Goal 14, Life Below Water, on conserving and sustainably using the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.

3.4 In January 2020, based on a concept note developed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), Lord Goldsmith, then joint minister of state for the Pacific and international environment at Defra, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the Department for International Development (DFID), agreed that the design and implementation of the Blue Planet Fund should be shared between the three departments – soon to be two, when FCO and DFID merged to become the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) later that year – with Defra acting as strategic lead and retaining a majority share of the Fund’s £500 million pot. A year later, in June 2021, the Fund was launched. See Figure 1 for a timeline of the Fund.

How the Fund is managed

3.5 While both Defra and FCDO were engaged in managing the Blue Planet Fund since its launch, the delivery timelines for the two departments are very different. In the first two years after the Fund’s launch, only Defra was involved in its delivery. Defra started delivery of its £310 million majority share of the Fund from financial year 2021-22 and will continue to 2025-26, with the option to request further funding in the next spending review. FCDO only began delivering its smaller £190 million share this financial year (2023-24) and will continue to 2029-30. The delivery of the Fund is guided by a delivery framework agreed in February 2022. The framework lists UK commitments and priorities on marine issues. At the time of writing, an update to the framework was underway.

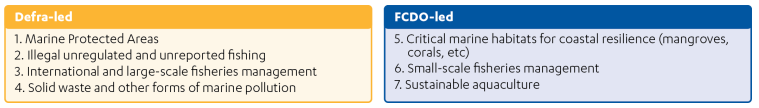

3.6 Defra and FCDO are jointly responsible for ensuring the coherence and coordination of the Fund portfolio, with Defra acting as the Fund’s strategic lead. In 2021, seven strategic outcomes were developed to guide delivery, with Defra allocated as the lead on delivering four of the outcomes and FCDO as the lead on three (see Figure 2). Different programmes can contribute to multiple outcomes.

Figure 2: The seven priority outcomes split by department

Overview of the Fund portfolio

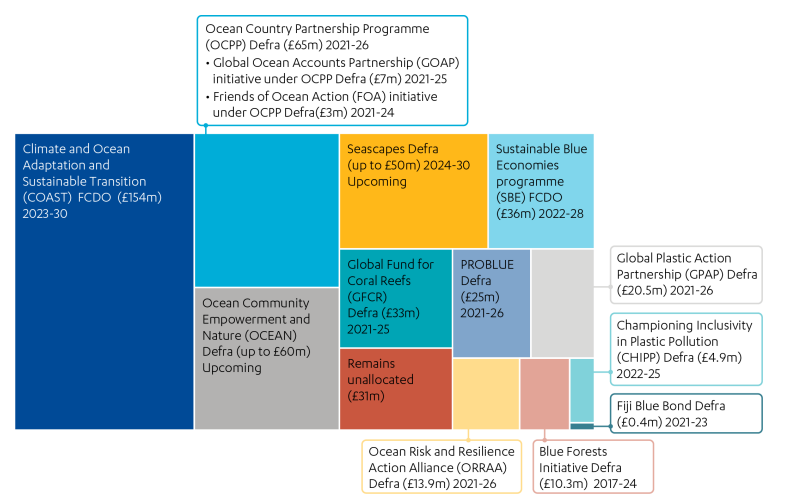

3.7 As of October 2023, the portfolio consists of 12 programmes. Two of these are led by FCDO, while the rest are led by Defra. Out of the 11 active programmes (Fiji Blue Bond has just completed15), six are multilateral, three bilateral and two bilateral with some components delivered through multilateral channels. One programme, Seascapes, is currently going through business case approval. See Figure 3 for the portfolio of programmes by size and Annex 1 for a full list of programmes with short descriptions.

Figure 3: The Blue Planet Fund portfolio of 12 programmes arranged by value (in £) as of October 2023

3.8 Defra’s portfolio includes eight active programmes, plus one completed programme and one under development. Its flagship bilateral initiative is the Ocean Country Partnership Programme (OCPP), which aims to build long-term local and regional marine science capacity in support of policymaking to address marine environmental challenges. OCPP focuses on three key themes: marine pollution, marine biodiversity, and sustainable seafood.

3.9 FCDO started the delivery of its two programmes in 2023. The first is the Climate and Ocean Adaptation and Sustainable Transition programme, which aims to help vulnerable coastal communities improve their adaptive capacities and resilience to climate change and increase their prosperity through more sustainable management of their marine environment. The second is the Sustainable Blue Economies programme for supporting ODA-eligible small island developing states and their economies to improve their ability to withstand the impacts of climate change and economic shocks.

3.10 The allocation of the Blue Planet Fund has been front-loaded. Of the total £500 million, only £31 million (or 6.2%) remains unallocated in October 2023, two and a half years since the Fund’s inception.

4. Findings

4.1 The findings are organised by review question, considering the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of the Blue Planet Fund. The findings highlight key risks and weaknesses within the Fund that should be addressed.

Relevance: How relevant is the Blue Planet Fund to developing country needs as part of meeting the UK’s international climate finance objectives?

4.2 This section first considers the Fund’s strategic and programme approach and then turns to the question of how the Fund is aligned with the UK’s ICF objectives.

The Blue Planet Fund is a highly relevant contribution towards Sustainable Development Goal 14

4.3 The UK’s establishment of the Blue Planet Fund as its main vehicle for UK Official Development Assistance (ODA) support on marine issues is relevant to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 commitment “to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”. Recognising the importance of oceans for sustainable development and the fact that this SDG is one of the most underfunded, the establishment of the Fund was part of the efforts by a range of multilateral and bilateral donors and foundations was to increase ODA in this area. Despite this, aid spending in pursuit of SDG 14 continues to represent only a small fraction of global aid.

Spending through the Blue Planet Fund is counted towards the UK’s ICF commitment, but the Fund is only directly linked to ICF through some key performance indicators

4.4 The Blue Planet Fund is referenced in the March 2023 International climate finance strategy, which directly mentions FCDO’s two Blue Planet Fund programmes and Defra’s Blue Forests Initiative programme, which was adapted from the previous ICF portfolio:

Largely funded through ICF, the UK is delivering a portfolio of programmes under the £500m Blue Planet Fund to support the protection and restoration of marine environments and the development of sustainable blue economies in developing countries to deliver positive outcomes for climate, biodiversity and poverty.

UK international climate finance strategy, March 2023

4.5 The ICF strategy has no theory of change to explain how it aims to achieve results. It identifies four broad themes, also called ‘pillars’: clean energy; nature for climate and people; adaptation and resilience; and sustainable cities, infrastructure and transport. These pillars describe in general terms what ICF will work on as part of the larger UK climate and environment ambitions. The Blue Planet Fund is listed under the ICF pillar on nature for climate and people and its high-level commitment on nature.

4.6 The Fund was announced as part of the UK government’s £3 billion nature commitment in 2021, under the wider UK ICF commitment. The majority of the Fund’s activities are counted towards the UK’s ICF spend. The Fund’s connection to ICF management is through reporting programmes that count as ICF against at least one of the UK’s ICF portfolio-level key performance indicators (KPIs) (see more in paragraph 4.66).

Country and regional needs were not sufficiently sought in the early stages of the Fund’s development

4.7 In the early stages of the Blue Planet Fund, there was internal consultation with UK government staff in the UK and abroad on its geographical remit. A top-down country prioritisation exercise was undertaken, scoring countries against four environment and two poverty indicators to give a composite score

4.8 However, no mapping of marine work globally was done to inform the Fund’s priority country selection, and consultation with governments and national stakeholders on global, regional and national needs and priorities was inconsistent and generally insufficient during the overarching design period.

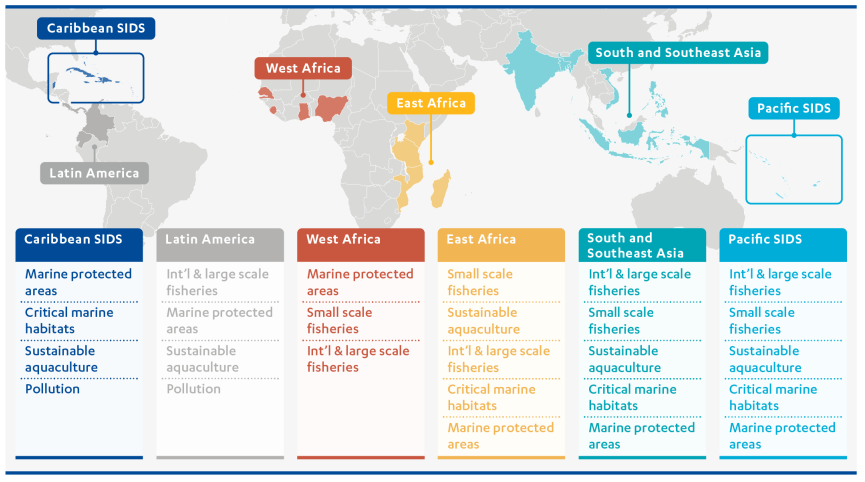

4.9 According to interviewees, some survey data from FCDO staff abroad was collected in 2020, for the Fund to identify its list of priority countries (see Figure 6 for an overview of priority countries and regions). However, since many of the Blue Planet Fund’s early programmes were pre-existing programmes repurposed for the Fund – by scaling up, adapting, merging or renaming ongoing activities – there was limited opportunity to design a Fund portfolio focused on countries with the greatest needs. Instead, in many cases country selection was informed by whether there was already programming in place which Defra could re-assign as coming under the Blue Planet Fund.

Although country needs did not inform the overall priority country selection, just over half of the Fund’s programmes are sensitive to country needs in the countries where they are active

4.10 The Blue Planet Fund and its programmes are centrally managed and were centrally designed. Engagement with countries was limited in the early stages of development and primarily conducted through the Fund teams engaging with UK staff in partner countries. Based on our interviews and the documentation we reviewed, the Fund’s Defra team did not adequately consider feedback from countries and regions on their needs as early programmes were adapted, scaled up or designed. Where business cases were shared with staff at UK embassies and High Commissions, it was only in the latter stages of the design process, and not enough time was provided to allow feedback from UK government staff abroad or regional experts to influence the design. The Fund teams are trying to address this issue through increased consultations and the development of Blue Planet Fund country plans to support coherent delivery in the Fund’s priority countries – although these come after the design and approval of the vast majority of the Fund’s programmes.

4.11 In total, we found a mixed picture when it comes to the extent to which the Fund’s activities within priority partner countries are demand-led and responsive to partner country needs. Assessing the business cases of the Blue Planet Fund programmes, we found that more than half of the programmes or some of their components were seen as demand-led either by partner countries or local communities. The FCDO flagship Climate and Ocean Adaptation and Sustainable Transition (COAST) programme, which was not launched until 2023, and FCDO’s Sustainable Blue Economies (SBE) programme, do not face the same problem with retrofitting found in some of Defra’s programming, as the design was based on evidence gathering to ensure that partner country needs and priorities were taken into account. Box 3 provides two examples of Blue Planet Fund bilateral programmes that reflect partner country needs.

Box 3: Two examples of Blue Planet Fund bilateral programmes considering country needs and priorities in their design

- Climate and Ocean Adaptation and Sustainable Transition (COAST) – £154 million, 2023-30 – FCDO’s new multi-component programme’s aim is to improve vulnerable coastal communities’ adaptative capacities and resilience to climate change and increase their prosperity through more sustainable management of coastal resources. The largest programme component (60-70% of the budget) is planning to provide support in up to six priority countries through sub-components i and ii below, and wider support in sub-component iii:

i. Reforming planning and policy in priority countries through technical assistance (TA), analysis, and capacity building.

ii. Inclusive coastal stewardship and livelihoods in priority countries: grants to support projects, activities, capacity building and action at local levels, for example stewardship and sustainable use of coastal resources.

iii. Responsive coastal management and governance support: provision of demand-led TA, analysis and capacity building to national and sub-national governments, regional bodies and institutions located outside the programme’s priority countries, with requests for support submitted by UK embassies.

This component, as noted in its business case, will provide TA, capacity building and analysis on a demand-led basis, ensuring it is tailored to country context, aligned to priorities identified by embassy staff, and informed by political economy, sensitivity, and other analysis. Sub-components focus on COAST’s six priority countries and national and sub-national governments, regional bodies, and institutions in any ODA-eligible country, with requests for support submitted by UK embassies.

- The Ocean Country Partnership Programme (OCPP) – £65 million, 2021-26 – Defra’s programme, mainly delivered through the department’s arm’s-length bodies, provides technical assistance to partner countries to deliver positive impacts on the livelihoods of coastal communities across three key themes: marine pollution, marine biodiversity, and sustainable seafood. The programme is designed to be demand-led, with activities developed with partner countries. These activities are directed towards capacity building for marine science in local institutions, organisations, and communities. The programme currently has partnerships in ten countries and is scoping two more.

4.12 Among the Blue Planet Fund programmes delivered by multilaterals, we noted that PROBLUE, which supports the development of blue economies across small island developing states (SIDS) and coastal least developed countries, is designed to be demand-led, working with World Bank country offices. The Global Fund for Coral Reefs, a multi-partner trust fund integrating public and private grants and investments for coral reefs with particular attention to SIDS, is led by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) which aims to engage with communities, but not necessarily with their governments (such as in Fiji). The programme will be mobilising a network of UNDP country-based teams to convene with in-country stakeholders. One investment criterion outlines that it will deliver directly on country priorities as understood by UNDP. However, it is a relatively new fund with a limited track record.

4.13 Three programmes directly involve local organisations and aim to address local community needs. These are the Global Plastic Action Partnership (GPAP), a public-private partnership established in 2018 by the World Economic Forum to accelerate the global response to the problem of ocean plastic pollution; the Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA), a multi-sector alliance focusing on de-risking investments in critical ecosystems; and the Global Fund for Coral Reefs (GFCR), a UNDP grant programme to save coral reefs and support communities that rely on them.

4.14 In many cases, the work on country needs came after the programme design and was not informed by country analysis prior to approval of the programme. With a ready pipeline of programmes from Defra that could be adapted or scaled up, access to funding was predetermined rather than informed by country needs. The country plans are aiming to redress this but their impact will be limited by the fact that almost all of the Fund has been allocated. The aim of the country plans currently under development is to improve programme delivery and to drive focus on in-country priorities and needs.

The Fund has emerged as a broad portfolio of programmes

4.15 In the absence of a strategy and given the speed with which the Fund was established, the portfolio that has emerged is scattered across a range of marine themes. Many decisions on themes, geographies and programmes were made ahead of the Fund’s seven priority outcomes being set. The Fund itself is sometimes referred to by stakeholders as a ‘wrapper’ or ‘umbrella’, given the disparate nature of its activities. Due to the limited consultation done before spending began, it will not be possible to tell whether the Fund is additional or complementary to other development partners. Adapted and scaled-up programmes and new programmes are now being retrofitted into country plans and theories of change.

4.16 The original ministerial steer had been for the Fund to prioritise bilateral delivery. However, due to the speed with which the Fund was launched, the priority focus was on programme design, delivery and spend. This meant that most of Defra’s early Fund programmes were multilateral. To speed up delivery, some pre-existing projects that were focused on marine protection, fisheries and pollution were brought under the Fund’s umbrella. Some were scaled up while others were merged. For example:

- The Blue Forests Initiative programme started in 2017 and was managed by Defra’s International Biodiversity and Climate directorate. In July 2022, Defra’s Blue Planet Fund team took over the programme delivery.

- The Global Plastic Action Partnership (GPAP), a multilateral partnership, was funded by Defra prior to June 2021 and was subsequently scaled up with Blue Planet Fund resources.

- Defra’s flagship bilateral programme, the Ocean Country Partnership Programme (OCPP), incorporated and adapted existing UK programming and partnership work including the Commonwealth Litter Programme and One Health Aquaculture, both delivered by the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), a Defra arm’s-length body. Two new multilateral programmes Global Ocean Accounts Partnership (GOAP) and Friends of Ocean Action (FOA) were merged under OCPP after one year of delivery.

4.17 Only six of the Blue Planet Fund’s current programmes were developed specifically for the Fund. Several interviewees from the government in headquarters and in-country questioned the coherence, creativity and ambition of this approach (see Figure 4). While FCDO designed programmes to support its three allocated objectives, Defra’s early portfolio was more opportunistic, working with multilateral funding for speed and in some cases retrofitting its existing bilateral programmes. This made it difficult to identify or prioritise country needs.

Figure 4: Blue Planet Fund portfolio typology

| A programme typology | |

|---|---|

| Blue Forests Initiative, 2017-24 | Legacy |

| Global Plastic Action Partnership (GPAP), 2021-26 | Scale-up |

| Fiji Blue Bond, 2021-23 | New |

| PROBLUE, 2021-26 | New |

| Ocean Country Partnership Programme (OCPP), 2021-26 | Legacy / adapted |

| - Global Ocean Accounts Partnership (GOAP) | New |

| - Friends of Ocean Action (FOA) | New |

| Global Fund for Coral Reef (GFCR), 2021-25 | New |

| Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (ORRAA), 2021-26 | New |

| Championing Inclusivity in Plastic Pollution (CHIPP), 2022-25 | Legacy / adapted |

| Sustainable Blue Economies (SBE), 2022-28 | Adapted |

| Climate and Ocean Adaptation and Sustainable Transition (COAST), 2023-30 | New |

| Ocean Community Empowerment and Nature (OCEAN), 2023-30 (new) | New |

| Seascapes, 2024-30 (new) | Approved |

| Unallocated £31m | Unallocated |

Developing countries lack opportunities to access bilateral funding, although this will be addressed through a planned competitive fund

4.18 There is so far no direct process by which developing countries can apply for support from the Fund. Country selection for bilateral programmes is done by central teams, and there is only one example (the small Fiji Blue Bond programme) where a programme was taken up based on a recommendation from staff in-country at the request of a government. Multilateral programmes have their own processes for project application. The Fund offer to countries, as well as programmes they support (including multilaterals) has not been clearly communicated to country governments.

4.19 Alongside a small number of sub-components of existing programmes, the upcoming Ocean Community Empowerment and Nature (OCEAN) competitive fund might reduce this direct funding gap and provide some access to funding for local non-governmental organisations (NGOs). OCEAN is planned to run from 2023 to 2030 with a possible budget of up to £60 million. The competitive fund will have two application rounds, both of which will support all seven Fund priority outcomes:

- Small grants: up to £250,000 targeting smaller, in-country organisations and local communities with a focus on capacity building.

- Large grants: up to £3 million targeting larger organisations or consortia partnering local organisations, both of which can absorb increased funding to scale up existing activities and reach higher numbers of people.

Coherence: How coherent and coordinated is the Blue Planet Fund within and across the two departments (Defra and FCDO)?

The departments are working to different timelines, which impedes coherence and coordination

4.20 Defra programmes were announced in 2021, while FCDO programmes came on stream in 2023 (see Figure 1). The stakeholders we interviewed provided several explanations for the staggered timeline. As described in other ICAI reports, because of its role in managing the ODA spending target, FCDO’s resources were impacted by the UK government’s decision to reduce its ODA spending commitment from 0.7% to 0.5% of gross national income following the COVID-19 outbreak. This led to successive reductions in FCDO’s aid budget in 2020 and 2021, followed by a pause in non-essential ODA spending for several months in 2022, caused by the soaring costs of accommodating asylum seekers and refugees in the UK categorised as ODA. Interviewees explained that Defra, in contrast, had a ready pipeline of projects that it could rebadge. There was also a strong ministerial preference to launch the Fund at the 2021 G7 summit and to use its announcement to support other high-level events such as COP26 in Glasgow.

4.21 As a result of the desire to launch in 2021, to support ministerial priorities, the establishment of the Fund’s essential management processes came after launch and the start of delivery. The Blue Planet Fund emerged as a relatively disparate collection of programmes rather than a jointly managed coherent Fund, with many management processes still being finalised and insufficient Fund-level oversight.

While there is duplication in some areas there are delivery gaps in others

4.22 Defra and FCDO each lead on different strategic outcomes for the Fund (see Figure 2 for the division). The selection of departments to lead on each outcome was made in 2021 based on their expertise, previous programmes and Defra’s planned Blue Planet Fund pipeline. However, across these seven areas there is a level of overlap, and some programmes span the work of both departments. Defra programmes, such as OCPP, ORRAA and OCEAN, are delivering against the three FCDO outcome areas, while the FCDO programmes, COAST and SBE, deliver against the four Defra outcomes in addition to their own three priority areas. We were told that some of these overlaps were created due to Defra’s earlier start and its funding through multilateral programmes. The split between departments to deliver the Fund is not guided by geography, which makes it hard to coordinate at country level. Both departments now recognise that in cases where programmes’ activities overlap, the programme leads must coordinate delivery to avoid duplication. The country plans now under development are needed to set clear objectives for the programmes of both departments in-country (see paragraph 4.35).

4.23 Recent mapping of the programmes undertaken as part of the refresh of the Fund’s theory of change showed, for example, that there are gaps in delivery against some of the Blue Planet Fund (BPF) priority outcomes, particularly the large-scale fisheries and illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing outcomes. Defra is now trying to address this gap with new programming, but with almost all the Fund allocated already there is limited opportunity for additional programming. The Joint Management Board (JMB) has recognised that this presents a risk that the ‘BPF does not deliver a publicly stated BPF priority or an international HMG priority’.

The Fund lacks strategic direction, and parts of its delivery framework remain in draft form

4.24 The Blue Planet Fund’s delivery is guided by a delivery framework, which is an operational plan consisting of: a list of UK commitments and priorities labelled strategic aims; a high-level theory of change and broad impact statement; an outline of the Fund’s governance structure; an outline of the Fund’s delivery structure, dividing ownership of seven priority outcomes between Defra and FCDO; and a long list of priority countries. Some key elements of the delivery framework remain in draft form, including portfolio monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) and KPIs. The updated theory of change for the Fund and each of the priority outcomes have been recently finalised, in October 2023.

4.25 There is no overarching Fund strategy on how best to capitalise on a diverse portfolio of marine environment-related programmes managed by two departments, with different timelines, across seven different outcome areas.

4.26 In the absence of such a strategy, the burden falls on the theory of change, which is now being refreshed and expanded. This is a complicated process with additional theories of change developed for each outcome and existing programmes mapping how they support individual outcomes. This approach looks like simply retrospectively building a series of theories of change around approved programmes, rather than programmes being informed by any strategic direction for the Fund.

There is limited oversight of the UK’s flagship £500 million marine environment fund

4.27 The two spending departments work together under the oversight of the Joint Management Board (JMB), which holds quarterly meetings, the first of which was in February 2021. The JMB is chaired by Defra as the strategic lead. The JMB provides strategic guidance on design, delivery and risk, but does not have spending decision power. Staff interviewed noted that over two years the board has improved its strategic guidance, but some have indicated that it has limited capacity to drive direction. For instance, no annual report is issued by the Fund and presented to the JMB, and while the JMB reviews initial concept notes to provide early guidance, it does not have a formal role of approving business cases. If these measures were introduced, both would improve accountability and the former would also improve the transparency of the Fund.

4.28 Both departments have Blue Planet Fund teams which hold joint operational meetings to share updates, aid coordination and support JMB planning. A diagram of the key elements of the Fund’s complex coordination and governance can be found in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Governance of the Blue Planet Fund

4.29 As is standard practice across the UK government, Defra and FCDO are each accountable for their own Fund expenditure and each department has its own internal approval processes. Defra’s ODA Board has responsibility for overseeing Defra’s ODA strategy and budget, including its Blue Planet Fund programmes. FCDO has a representative on the Defra ODA Board, but there is no representation from Defra (or other departments) in FCDO’s internal ODA programme approval process. However, FCDO consulted with Defra teams during the design of COAST and SBE to benefit from their expertise and support portfolio coherence. Until September 2022, the Blue Planet Fund team reported regularly to Lord Goldsmith as the joint Defra-FCDO minister responsible for international climate and environment. While there was no joint minister, each department reported to its own separate ministers. On 15 November 2023, a new joint Defra-FCDO minister was appointed. The Fund only reports to other cross-government boards on climate and nature on an ad hoc basis.

4.30 As the Fund is largely counted as UK international climate finance, the ICF Management Board and Strategy Board should oversee and steer it as part of the strategic implementation of ICF. However, we were informed that the Fund has not been discussed at either of these boards, even though several ‘severe’ and ‘major’ risks – recognising the same problems evidenced by ICAI in this rapid review – have been highlighted at the JMB since the Fund’s inception. We have been told that the ICF Management Board does not generally consider individual programmes, but instead may take decisions on the strategic implementation for ICF, undertake thematic deep dives and support lesson sharing. However, in interviews, government stakeholders recognised that risks identified at portfolio level could have been reported to the ICF Management Board. We find that there has been a failure of oversight of this flagship Fund, with ‘major’ and ‘severe’ risks identified by the JMB that were not escalated to the ICF Management or Strategy Boards.

4.31 The Blue Planet Fund’s delivery framework included an option to create regional boards to provide strategic advice. However, it was subsequently decided that the departments did not want to create new boards and preferred to use existing regional boards as needed. When asked if these boards have been used to communicate or discuss the Fund’s work, programmes or upcoming plans, the Fund team informed us that “discussion on the Fund at regional boards has been limited”. For example, no specific Fund item has been presented and discussed since January 2021 at the UK government’s Southeast Asia Regional Climate Board, its Regional Africa Climate Board, or its Pacific Strategy Governance Board. (Only one programme, SBE, is consistently discussed at the SIDS Board, having been discussed at every meeting since the SIDS Board’s inception). This lack of engagement seems like a lost opportunity given the lack of visibility at regional and country level of this centrally managed fund.

4.32 There are a lack of opportunities for staff in-country to engage in Fund governance or strategic direction. A small number of Blue Planet Fund programmes engage staff in-country in governance and decision-making (for example SBE, COAST) and project selection (for example COAST, SBE, ORRAA, OCPP, GFCR). We have been told that FCDO embassies and High Commissions have not been invited to attend the JMB, nor have meeting minutes been shared with them, even though this was requested. The JMB ran a deep-dive session on the Pacific region in November 2022, inviting representatives from High Commissions and embassies to share their concerns. However, this was a one-off event, and has not been replicated for other regions.

There are risks to the coherence of the Blue Planet Fund portfolio at country level

4.33 The Blue Planet Fund teams in Defra and FCDO are aware of flagged risks to the coherence of the portfolio at country level, as recognised in the July 2023 JMB risk register, which noted: ‘Lack of strategic cross-government coordination leads to uncoordinated Defra and FCDO programming in country, impacting UK reputation and effective programme delivery (rated as severe risk) with mitigation identified that might move this to down to major risk.’

4.34 Feedback from in-country stakeholders indicated that coordination of the portfolio at country level has been poor. This is especially clear in our Fiji case study, where we found a lack of coordination between programmes, with no communication around portfolio opportunities or consideration of how different Blue Planet Fund programmes fit together and with other programming in-country. There were even cases in which FCDO High Commission staff were not informed about planned projects or visits to the country (see further information in country case studies from Fiji and Mozambique below).

4.35 The Fund is appointing five regional coordinators to support delivery at the country level, four of whom have recently taken up their positions. As of November 2023, a Blue Planet Fund country plan has been developed for Mozambique, but final approval from the Mozambique government has been pending for six months. Five other country or regional plans have recently been commissioned, with FCDO leading on Indonesia and the Philippines, and Defra leading on the Pacific, Ghana and the Maldives. Such plans should provide an opportunity for country governments and FCDO heads of mission to discuss country capacity, capability, needs and preferences, supporting a more informed and coordinated approach to programme delivery in-country. We have been advised, however, that these will not be ready until later this year.

Fiji case study: Coherence and transparency challenges

4.36 The ocean is critical to Fiji’s sustainable development as a small island developing state. Fiji’s blue economy supports livelihoods in fishing, tourism, aquaculture and transport. While interest in marine protection and ocean resources is high among development partners in the region, SIDS governments such as Fiji often have limited capacity to manage parallel interventions from multiple donors. Effective coordination among donors is therefore vital.

4.37 As of October 2023, three programmes operate in Fiji: OCPP, GFCR and PROBLUE, with Fiji Blue Bond just completed. Under the OCPP programme, the Friends of Ocean Action initiative helps to develop a Blue Recovery Country Strategy and Hub for Fiji following the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Global Ocean Accounts Partnership (GOAP) initiative (under OCPP) is supporting Fiji to establish ‘ocean accounts’ – integrated records of social, economic and environmental data, aligned with national accounts systems, that allow a country to measure and manage economic activities related to its oceans and to build sustainable development maps for the use of its ocean resources. PROBLUE has supported an environmental and economic analysis of development options for Fiji, with a focus on tourism, which will inform the assessment of the country’s blue economy potential. For the GFCR programme in Fiji, see the case study in Box 4.

4.38 Stakeholders we interviewed in Fiji appreciated the financial support but wanted to see a coherent and Fiji-led approach across programmes. This is made difficult by the lack of a coherent framework for the Fund’s delivery in-country and across the Pacific region. A new Blue Planet Fund regional coordinator in the High Commission in Fiji has recently been recruited. The post will support portfolio coordination and delivery in the region, and facilitate engagement between staff in the region and staff in headquarters. However, the relatively junior level of the post may prove to be a limitation.

4.39 Some UK heads of mission have asked to be represented on the Fund’s JMB. The High Commission in Fiji stressed to ICAI in interviews the importance of using its in-house regional and SIDS expertise. There were cases where the High Commission in Fiji was not informed about planned projects or country visits carried out by Defra’s central teams or arm’s-length bodies. We were also told of examples where the High Commission and other stakeholders in Fiji were unable to identify which activities the Fund supported, due to a lack of information on these centrally managed programmes.

Box 4: Global Fund for Coral Reefs in Fiji – Investing in Coral Reefs and the Blue Economy (CRBE)

| Convening organisation: UNDP | The GFCR is a multi-partner trust fund focused on mobilising resources and action by private and public investment capital to protect and restore coral reef ecosystems and support coral reef dependent communities. |

| Timeline: 2021-30 | |

| Budget: $5.1 million (multi-donor) | |

| Country implementors: Beqa Adventure Divers, Blue Finance, Matantaki | |

| CRBE in Fiji aims to create a blended finance facility and to build capacity to mobilise private and public investment capital for initiatives that have a positive impact on Fijian cora reefs and the communities that rely on them. It aims to build a pipeline of projects with a blend of technical assistance, performance grants and concessional capital for de-risking. | |

Mozambique case study: Piloting a more coherent, joined-up approach for Fund delivery

4.40 Mozambique’s 2,770 km of coastline offers a wide diversity of habitats that shape its blue economy industries such as fishing, tourism and shipping. Two-thirds of the country’s population live in the coastal region. Mozambique’s marine sector plays an important role in food security, job creation and economic growth. The blue economy contributes up to 10% of the country’s gross domestic product.

4.41 As of October 2023, the Fund supports four programmes and one initiative in Mozambique:

- OCPP is planning to provide technical assistance to the government of Mozambique on sustainable fisheries. It aims to support Mozambique’s government in expanding its marine protected area, and to build the technical capacity of the government and national NGOs to protect the environment and better manage Mozambique’s fisheries. A case study in Box 5 describes the GOAP initiative in Mozambique, which falls under OCPP.

- The activities of COAST, through the international organisation WorldFish, will include data collection and management of small-scale artisanal fisheries, reducing food waste and loss, and piloting community-led fish farms. COAST’s larger bilateral technical assistance and local grants component is planned to start in four priority countries, including Mozambique, in 2024 following central procurement.

- PROBLUE is preparing to deliver a $1.85 million multi-country project (including Mozambique) to support the reduction of marine plastic pollution.

- GFCR is in the process of approving a project in Mozambique, with the aim of promoting sustainable financing of coral reef conservation by leveraging private market-based investment and financial models.

4.42 A Blue Planet Fund delegation visit to Mozambique in November 2022, to discuss possible bilateral support, brought to light the need for the Fund to provide a clearer offer of support to the government, and for Fund programmes to have a more joined-up approach, both among themselves and with other projects funded by the UK and other donors. This would be consistent with longstanding good practice in ODA delivery, but at the time had not featured in the approach to the delivery of the Fund.

4.43 The Fund is in the process of establishing a Mozambique Blue Planet Fund country plan to show how the portfolio can support the government of Mozambique’s blue economy priorities. The framework outlines mechanisms for coordinating Fund-supported work in Mozambique, including a Fund delivery partner coordination forum (an initiative to be set up by COAST), a technical working group involving the Fund and the Mozambique government, and the Fund’s participation in the existing Cooperating Partners Blue Economy Working Group. A Blue Planet Fund regional coordinator has been recently hired to facilitate in-country and regional work. The framework will be updated annually with progress achieved and upcoming activities to improve effectiveness and coherence.

Box 5: The Global Ocean Accounts Partnership project in Mozambique

| Convening organisation: GOAP | The Global Ocean Accounts Partnership (GOAP) is a global, multi-stakeholder partnership established to enable countries to develop ocean natural capital accounting to inform decision-making on the sustainable and equitable use of marine resources |

| Timeline: 2021-25 | |

| Pilot budget (phase 1): £100,000 | |

| Mozambique - Bazaruto archipelago | |

| GOAP has a pilot project in Mozambique. The goal is to help Mozambique manage its ocean resources sustainably by creating ocean accounts and developing roadmaps to guide the country's development related to the ocean. | |

Effectiveness: Are the systems, controls and procedures of the Blue Planet Fund adequate to ensure effective programming and good value for money?

Resource allocation by country was based on a top-down formula

4.44 Fund decisions on programme selection and priority countries were guided by a country prioritisation exercise, followed by an investment criteria screening process (see below). This centrally driven prioritisation exercise started with an economic analysis of 140 ODA-eligible countries. Countries were scored against six indicators, weighted equally between environmental and poverty indicators. The top 60 countries were further refined by the Fund team by adding in the UK’s geographical priorities from the Integrated review and taking into consideration delivery challenges. We note that this somewhat UK-centric approach did not consider what other donors and partners were already doing. The outcome was a rather long list of five priority regions and 24 countries where the Fund aims to deliver its bilateral programme portfolio.

4.45 It was noted that multilateral funding would require a different approach, given that the Fund would be providing funds to programmes which were already established. We were told that the country list was expanded from 24 to include additional countries in Latin America, following ministerial preference to support a transboundary marine protected area (MPA) project in the region.

Figure 6: The six priority regions and 24 priority countries (plus new Latin American countries) of the Blue Planet Fund

South and Southeast Asia: Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Vietnam

West Africa: Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone

East Africa: Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania, Madagascar

Latin America: Transboundary marine protected area including Ecuador, Costa Rica, Colombia and Panama

Caribbean small island developing states (SIDS): Belize, Grenada

Pacific SIDS: Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu

There are weaknesses in how investment criteria are scored and in the evidence used to assess a project’s poverty reduction potential

4.46 The Fund’s investment criteria were finalised in February 2021 and used for initial programme scoping (see Annex 2). The investment criteria are applied in two stages, and proposed programmes must pass the first stage to move to the second.

- Stage one has five assessment criteria: Poverty reduction, environmental benefits, do no harm, UK priorities, and country needs. The first two are given a higher weighting than the next three.

- Stage two has five criteria: Financial soundness, delivery potential, additionality, mobilisation potential, and stakeholder engagement. The first three are given a higher weighting than the last two.

We understand that these criteria are under review, although this will be relevant only to the funding that is not yet allocated. A small number of programmes (for example COAST and Seascapes) are using an adapted form of investment criteria for project selection during delivery.

4.47 A concept note summarising the proposed programme and the results of the investment criteria screening is shared with the JMB for feedback, before advancing to the detailed design and preparation of the business case. The investment criteria are also used in the appraisal process during business case development. According to FCDO officials, no proposed programme (concept note) has ever been assessed as failing to meet the Fund’s investment criteria, although Defra officials offered one example of a concept note that was returned for revision. No assessment was done retrospectively for existing Defra-funded programmes that have been rebadged and moved under the Fund’s umbrella.

4.48 There is no separate ODA eligibility check for Fund programmes. ODA eligibility is screened first through the selection of priority countries (all of which must be ODA-eligible) and then through the poverty reduction criterion used in the two-stage investment assessment process described above. At stage one, a concept note must score at least two out of three points on the poverty reduction criterion to be allowed to proceed to stage two. As this is only one of ten weighted criteria, poverty reduction potential is not a strong focus.

4.49 The concept notes that we reviewed do not contain enough explanation for their scoring against the poverty reduction criterion to provide adequate assurance that they are likely to contribute to poverty reduction. Several business cases also do not provide sufficient evidence of links to poverty reduction (for example OCPP, ORRAA and CHIPP). This weakness was recognised multiple times in quality assurance reviews, as part of the business case approval process. In some cases, concerns raised during the approval process were addressed only through minor textual revision, rather than through a review of the project design.

4.50 The issue of lack of evidence on poverty reduction potential for Defra’s programmes and within marine environment programming more broadly has been recognised by FCDO’s COAST programme. This programme has been built around areas where evidence was stronger and knowledge is planned to be built. We must note that this evidence gap reflects a wider lack of evidence on the poverty impact of marine programming. It is positive that FCDO has recognised this evidence gap and sought to address it in programme design.

Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) guidance and tools are available. There is limited evidence of their application, but Defra’s ongoing work gives more attention to GESI

4.51 The UK International Development (Gender Equality) Act 2014 requires all UK aid programmes to give due consideration to the potential for reducing gender inequality. Gender is one of the five crosscutting priorities for Blue Planet Fund delivery. Both departments have a range of guidance and tools on GESI, including FCDO’s 2021 Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) guide on gender and Defra’s ODA operational guidance (strengthened in May 2023).

4.52 Gender is not included as one of the Fund’s investment criteria, but we were told by Defra that it is ‘folded in’ under the criteria of poverty reduction potential and ‘do no harm’. Our review of concept notes and business cases found that most, but not all, concept notes refer to gender, while all business cases do. Among the business cases, there was significant variation in the level of attention paid to gender: some made only passing references to promoting gender equality, while others had gender-focused activities and KPIs. The latter included FCDO’s COAST programme and Defra’s GPAP. The variability suggests a need for gender equality to be given more emphasis in the criteria and guidance. In 2023, Defra undertook an internal GESI review of its programming, which led to some immediate action, such as updating the PROBLUE logical framework with stronger gender indicators.

Defra has been slow to put consolidated ODA delivery guidance in place

4.53 Beyond the broad outline provided by the Fund’s delivery framework, guidance on programme delivery differs between Defra and FCDO. The £190 million tranche of funding spent by FCDO is governed by the PrOF, which provides the guiding framework for all FCDO programme delivery.

4.54 Defra has a relatively new but growing ODA hub team, which is progressively putting in place consolidated ODA programming guidance. In May 2023, the ODA hub combined guidance from FCDO’s PrOF and from the Cabinet Office with Defra’s own governance and assurance processes, creating a new operating manual. While Fund allocation and programme design is mostly complete, the new procedures will apply to the remaining Defra programmes.

4.55 The challenges of allocating ODA to departments with less experience in its management was raised by Parliament’s International Development Committee in 2019, which noted risks to coherence, transparency and poverty focus. ICAI has also noted that other ODA-spending departments often lack the standards and guidance outlined in FCDO’s PrOF. Despite these concerns, Defra’s ODA budget has increased significantly, along with an increase in staffing to deliver its portion of the Fund, shown in Figure 7.

There are uncertainties over the Fund’s classification as international climate finance

4.56 Not all of the Blue Planet Fund’s spending counts as ICF, since some Defra programme activities do not meet the internationally recognised OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Rio Markers for Climate. For example, programming on illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and plastic pollution do not necessarily qualify as climate finance. In the first year of the Blue Planet Fund’s operation, Defra marked around 30% of its spending under the Fund as ICF, but in the second year this increased to 70%, after a steer to increase this percentage and analysis of expected ICF activities within each programme. We were told that this estimation is done retrospectively after each financial year, based on an evidence based qualitative judgement of what percentage of actual spend under each programme’s activities is relevant to climate change. After several months of requesting to see the assessment done for Defra’s ICF programme allocation, we have only received guidance on increased scoring against general areas, and can therefore not verify its accuracy. One hundred percent of FCDO’s two Blue Planet Fund programmes will count as ICF.

4.57 Defra’s delivery team has been growing with the Fund’s portfolio. There are currently 26.4 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff supporting delivery, including five coordinators in posts in priority countries (supporting both Defra and FCDO delivery), with plans for a staff increase to 35.4 in 2024. FCDO’s delivery is managed by 4.05 FTE staff. We have been told that in the early years of delivery, lack of staff capacity resulted in slow implementation of processes at the Fund level. Figure 7 below shows the projected and approved disbursement profile of the Fund.

Figure 7: Fund disbursement profile over time and by department

| Blue Planet Fund £500m ODA | ||||||||

| Defra: FY 2021-25 (£310m) | FCDO: FY 2022-29 (£190m) | |||||||

| Defra's BPF managed by 26.4 FTE (as of October 23)*, projected to increase to 35.4 FTE (2024)* | FCDO's BPF managed by 4.05 FTE (as of October 23) | |||||||

| Projected spend (£m) | Approved spend (£m) | Actual spend (£m) | ICF (£m) | Projected spend (£m) | Approved spend (£m) | Actual spend (£m) | ICF (£m) | |

| 21/22 | N/A | 32 | 32 | £7.7 (actual) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 22/23 | N/A | 43.4 | 43.4 | £30.7 (actual) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 23/24 | 55.4 | 49.8 | 7 | £45 (projected) | 7.7 | 7.7 | 1.091 | 7.7 |

| 24/25 | 75.5 | 47.9 | N/A | £60.8 (projected) | 14.75 | N/A | N/A | 14.75 |

| 25/26 | 103.7 | 60.6 | N/A | £72.8 (projected) | 34.4 | N/A | N/A | 34.4 |

| 26/27 | - | - | - | - | 39.5 | N/A | N/A | 39.5 |

| 27/28 | - | - | - | - | 41.9 | N/A | N/A | 41.9 |

| 28/29 | - | - | - | - | 27 | N/A | N/A | 27 |

| 29/30 | - | - | - | - | 24.75 | N/A | N/A | 24.75 |

| Totals | 234.6* | 233.7 | 82.4 | 217 | 190 | 7.7 | 1.091 | 190 |

| *For Defra, £279 million is allocated to approved programmes plus those under design. £31 million remains unallocated to any programme, all within Defra's total allocation of the BPF. | ||||||||

There is a lack of transparency over the delivery arrangements between the Fund and its wide range of delivery partners, and in particular between Defra and its arm’s-length bodies

4.58 A large share of the Blue Planet Fund’s programming is delivered by multilateral partners, including the UNDP, the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank. Some programmes have multiple components delivered by a mixture of commercial partners and multilateral organisations. Others are delivered by UK-based arm’s-length bodies with whom Defra already had a relationship: the Centre for Environment,

Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas), the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) and the Marine Management Organisation (MMO). In many instances, the primary partners deliver through implementing agencies, sometimes through lengthy supply chains.

4.59 There is insufficient transparency, accountability and guidance on delivery along these supply chains, particularly in the case of the arm’s-length bodies that deliver Defra’s Ocean Country Partnership Programme (OCPP). We noted that the process outlined in the OCPP business cases has not been followed. Delivery responsibilities are outlined in an incomplete and unsigned memorandum of understanding (MOU), with gaps in key areas such as programme governance and management arrangements, reporting, and transparency requirements. This suggests a lack of adequate due diligence and supervision.

The arm’s-lengths bodies have high overheads – higher than donors usually allow for ODA funding

4.60 Each arm’s-length body has its own payment arrangements and should have individual MOUs in place with Defra. We have been advised that payments are made in advance, based on an agreed workplan and activities. This is contrary to the OCPP business cases, which specify payment in arrears, with robust KPIs for monitoring progress. More than £17.5 million has been disbursed without an adequate control framework.

4.61 The overheads charged across the three arm’s-length bodies range from 15% (MMO) to 37% (JNCC). These rates are significantly higher than those charged by UN agencies, which can typically range between 4% and 12%. Overheads were higher in the first year of delivery and are now declining as arm’s length bodies in turn sub-contract to third parties. The high management costs involved in Fund delivery chains raises the question of how much UK ODA in fact reaches the recipient countries. It is hard to identify a coherent approach to value of money for the Defra portion of the Fund, given its lack of due diligence and adequate supervision of delivery partners.

4.62 Defra informed us that new arrangements with the arm’s-length bodies are being put in place for OCPP, including a draft MOU to cover all three partners, led by Cefas. It will outline a new governance structure and payment arrangements, noting that future payments will be made at the point of need and in line with an agreed and costed programme of work at the beginning of each financial year.

The Fund lacks an effective system for tracking its overall results

4.63 Two and a half years after the launch of the Fund, there are several key management processes that either remain in development or are under review, including portfolio MEL and KPIs. The portfolio-level theory of change was finalised in October 2023, after ICAI concluded its evidence gathering. We have been told that priority has gone to activity design, rather than to Fund-level systems and processes. Several government interviewees noted the lack of a secretariat function or dedicated staff, which are common features for other ODA funds. This has made it more difficult to establish an effective management process.

4.64 The Fund produced an initial high-level theory of change in summer 2020. Both this and the updated version in 2021 were short on detail about how the Fund would deliver its intended results. The newly updated theory of change from October 2023 includes seven nested theories of change for each priority Fund outcome. It provides more detail on impact pathways and assumptions, and maps Blue Planet Fund programmes towards each outcome.

4.65 The current ten KPIs remain indicative. Developed at the launch of the Fund, they were intended to provide a basis for a final, comprehensive set of KPIs that would allow aggregation of results across the portfolio, helping the Fund to monitor its overall performance. Three indicators map to five ICF indicators; these ICF indicators are already accompanied by a well-developed methodology. These are the only indicators that the Fund’s programmes currently report against, as all ICF spending programmes must report results against at least one ICF KPI. At programme level, all programmes have or are developing their own logical frameworks with programme-specific indicators.

4.66 FCDO’s two programmes will report on ICF KPIs from next year, as they are just starting delivery. From eight active Defra programmes that are funded or partly funded by ICF, seven are reporting or planning to report on ICF KPIs, while one (the smaller Fiji Blue Bond programme) did not report at all. A working group was established to review the Fund’s KPIs, with several consultations and workshops undertaken to propose a new set of indicators.