CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states

Score summary

CDC has made progress in redirecting investments to low-income and fragile states, but has been slow in building in-country capacity to support a more developmental approach. CDC has not done enough to ensure or monitor development results, or to progress plans to improve evaluation and apply learning.

The CDC Group plc (CDC) is the UK’s development finance institution (DFI), wholly owned by the Department for International Development (DFID). Over the period of this review, from 2012 to 2018, CDC has played an increasing role in DFID’s economic development strategy. DFID has set CDC progressively more ambitious goals for achieving development impact in low-income and fragile states, and has reduced its financial return targets to facilitate this. DFID invested £1.8 billion of new capital into CDC over the four-year period from 2015 to 2018, with further injections planned through to 2021. This shift in strategy has required a fundamental transformation in the leadership and culture of CDC, a significantly expanded workforce with new skills, and major changes to products and practices.

CDC has made significant progress with this transformation, with more changes planned. It has successfully redirected new investments towards lower-income and fragile states and its priority sectors, though these are largely concentrated in a few countries and in the infrastructure and financial services sectors. It has diversified its investment products to include direct equity and debt; piloted innovative financial instruments and introduced a new ‘Catalyst Portfolio’ that invests in riskier markets; and it has increased its focus on development impact.

We welcome these changes, but note that a number of important activities have only recently been launched and it is therefore too early to assess their effectiveness or ultimate impact. Earlier progress on deployments to country offices, particularly in Africa, on the development of geographic and sectoral plans, and on monitoring and evaluation would have helped to accelerate the scale-up of investment and the achievement of broader development impact in these more challenging markets.

For most of the review period, CDC’s lack of clarity on expected development impact, its monitoring of a narrow set of impact metrics and the absence of comprehensive, independent evaluation made it difficult for us to assess its overall impact. From 2018, CDC began to significantly enhance its processes for impact management, monitoring and evaluation. However, there is more still to do to encourage impact, from the selection of investments through to portfolio management and exits. CDC’s leadership among DFIs in assessing and supporting the environmental, social and governance issues of its investees provides an indication of what could be achieved on impact more generally.

CDC has increased its resources for learning throughout the review period. There are examples of thoughtful and strategic research in priority areas, but these do not yet add up to a learning effort commensurate with the scale of CDC’s investment. We found that CDC has not maximised learning on development impact from its own investments, and that there is limited evidence of CDC gathering and applying learning on working in the most difficult investment markets.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Relevance: Does CDC have a credible approach to achieving development impact and financial returns in low-income and fragile states? |  |

| Question 2 Effectiveness: How effective are CDC's investments in low-income and fragile states? |  |

| Question 3 Learning: How well does CDC learn and innovate? |  |

Executive summary

CDC is the UK government’s development finance institution (DFI), wholly owned by the Department for International Development (DFID). Its mission is to promote economic development by investing in businesses in developing countries where markets are weak and where access to private finance is limited and expensive. As an aid-spending body, CDC aims to achieve a positive development impact. As a DFI, it is also expected to generate a financial return on its investment portfolio, which is recycled into future investments.

CDC’s importance within the UK’s aid portfolio has grown substantially. Between 2015 and 2018, it received investments of new capital from DFID totalling £1.8 billion. Further injections are planned through to 2021, with CDC projecting that its net assets may increase from £2.8 billion in 2012 to over £8 billion by 2021.

CDC plays a key role in DFID’s economic development strategy, which emphasises the reduction of poverty through building markets and trading ties, and catalysing private investment to create jobs and services. Aside from improving the investment climate and promoting economic growth, CDC also aims to contribute to poverty reduction through investments that improve access to essential goods and services for the poor.

Under a new investment strategy agreed with DFID in 2012, CDC shifted its investment focus towards lower-income and fragile states in Africa and South Asia, including challenging markets where investments are riskier and harder to find. This has required a fundamental transformation in the leadership, management and culture of CDC, a significantly expanded workforce with new skills and experience, and major changes to the organisation’s products and practices.

This performance review focuses on how well CDC has adapted its strategy, portfolio and organisational capacity to meet the challenge of achieving development impact in low-income and fragile states. It covers the period from 2012 to 2018.

Relevance: Does CDC have a credible approach to achieving development impact and financial returns in low-income and fragile states?

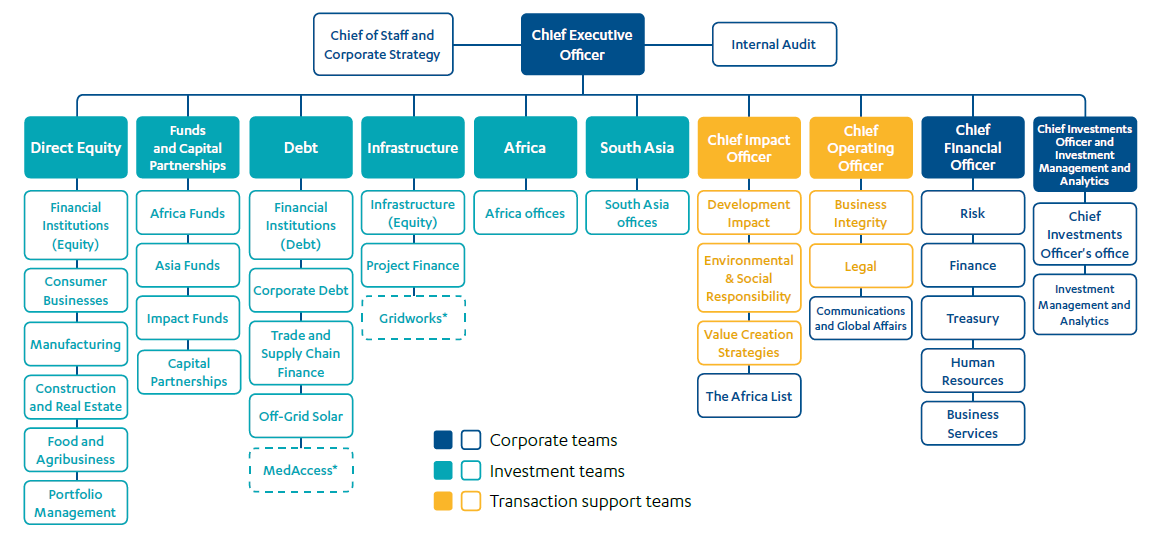

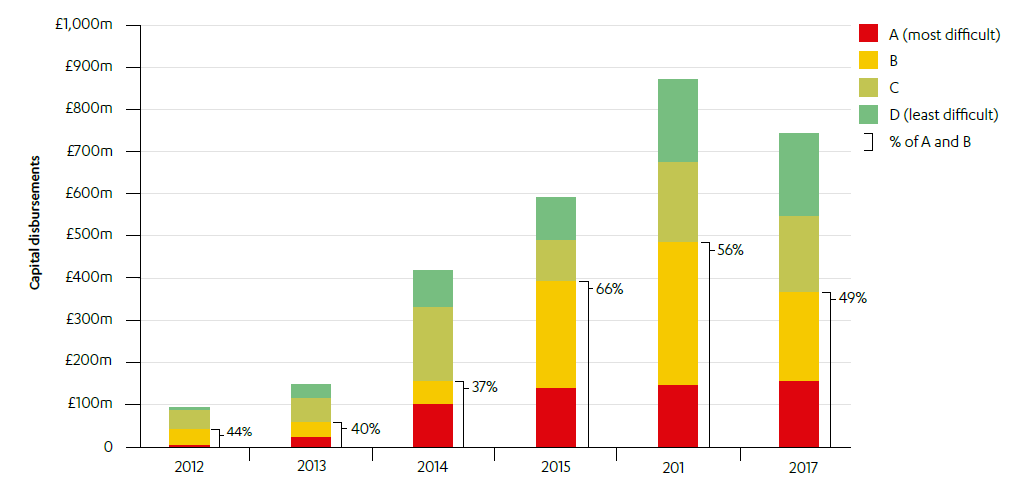

Since 2012, CDC has increased its emphasis on development impact and shifted its focus towards investing exclusively in low-income and fragile countries. In 2013, it began to use a Development Impact Grid, developed jointly with DFID, to screen potential investments and direct capital towards geographies and sectors with greater potential for development impact. The grid scores prospective investments along two axes: the investment difficulty of the country (or Indian state) and the potential of the sector to create jobs.

Between 2004 and 2012, CDC only invested indirectly, through intermediary funds. Since 2012, it has diversified its range of investment products to include direct equity and direct debt, has piloted innovative new financial instruments and is now expanding its technical assistance grants to give it more flexibility to support businesses in challenging investment environments.

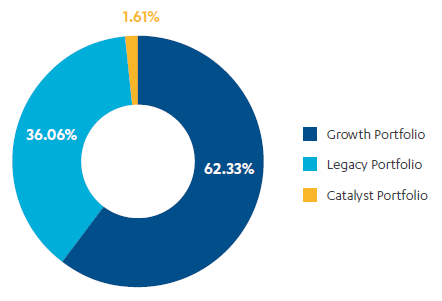

In 2017, CDC created a separate ‘Catalyst Portfolio’ to facilitate higher-risk investments with the potential for greater development impact in poorer communities and places. This has a lower ‘profitability hurdle’ (or target financial return) than its main portfolio, now called the ‘Growth Portfolio’. CDC has not set a firm target for the size of its Catalyst Portfolio but does not expect it to account for more than 20% of total investment by CDC.

CDC’s most recent corporate strategy, its 2017-21 strategic framework, includes commitments for new sector strategies, a larger in-country presence and enhanced monitoring and evaluation. CDC also aims to expand its knowledge of how to achieve development impact, including in areas such as women’s economic empowerment, and to develop new investment instruments to increase its reach in the most difficult markets. While we welcome these commitments, we conclude that CDC could have done more at an earlier stage in each of these areas. It is too early to determine how significant these changes will be in shaping future investment decisions or improving impact.

CDC collaborates well with DFID centrally, but the relationship is not as developed at country level, so there is a risk that opportunities for collaboration and knowledge sharing between CDC and DFID are being missed. We saw some positive examples of joint working on our country visits, but these were mainly one-off activities.

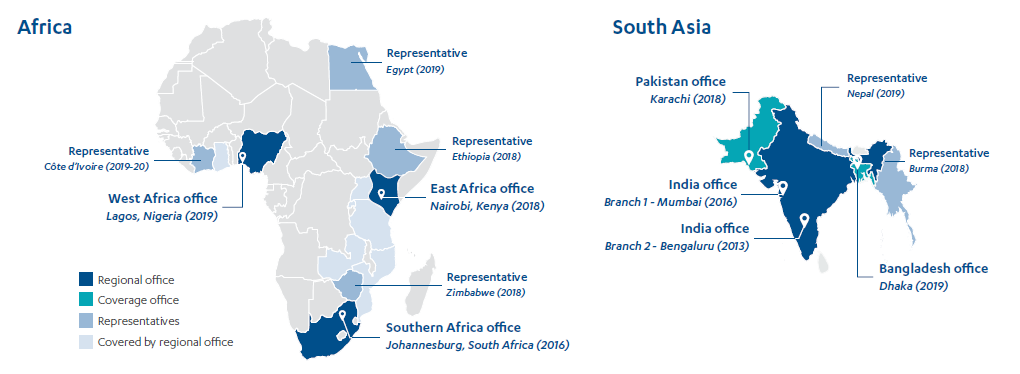

CDC re-established a country presence in India in 2013 but has been slow to establish offices elsewhere. At the end of 2017, it had ten staff in India but only seven in all of Africa, out of the total CDC staff of 266. A stronger country presence would help with sourcing investments, impact management and monitoring and evaluation. It would also facilitate coordination with DFID and with other development partners. CDC plans to open four regional offices in Africa by 2019, with single representatives in three further countries.

CDC identified seven priority sectors at the start of the review period but did not begin preparing comprehensive sector strategies until 2018. It does not have geographic strategies and instead plans to develop ‘country perspectives’ in the coming years that will collate existing information on economic development priorities and the private sector.

In summary, CDC has made important progress since 2012 in reorienting its strategy and plans, and transforming the organisation, to meet the very significant challenge of achieving both development impact and financial returns in more challenging markets. We have therefore awarded a green-amber score for relevance. However, the transition is not yet complete and many important initiatives are at an early stage. Given the commitment to additional capital injections by DFID, CDC needs to make further rapid progress in building staff capacity, strengthening its country network and developing and implementing its new strategies and plans for achieving development impact.

Effectiveness: How effective are CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states?

CDC has made progress in redirecting its capital towards priority sectors in lower-income and fragile countries. Between 2012 and 2017, 52% of the investments made in the Growth Portfolio were in countries classified as difficult investment environments (up from 23% in 2009-11). However, most of these investments were concentrated in a few of the larger economies in this category (such as Kenya and Nigeria) and most of its investee companies were headquartered in the more prosperous areas of these countries, particularly the capitals.

For most of the review period, CDC relied mainly on the Development Impact Grid to screen investments for their potential benefit to poor people, focusing on job creation potential. While it was a useful innovation, the grid is a relatively blunt instrument for assessing potential development impact, with a narrow focus on jobs. We believe that CDC should have done more to select impactful investments.

Beyond the decision to invest, CDC did not set targets or expectations for development impact, nor did it do enough to encourage opportunities to enhance development impact. Until recently, it also monitored only a narrow set of metrics, making it difficult to assess CDC’s overall impact, both at the investment level and for the portfolio as a whole, for much of the review period.

From 2018, CDC has introduced improvements to the assessment and monitoring of impact, supported by new ‘development impact cases’ for all potential investments and a significantly expanded team of development impact experts. We welcome these developments, which have the potential to broaden CDC’s impact and strengthen its approach to tracking progress. CDC needs to embed these new processes and resources quickly and systematically into investment sourcing, screening and management across its product teams, to support its ambitions for development impact.

CDC is a leader among DFIs in assessing and supporting environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. Its success in helping and encouraging funds and investees to improve their practices in these areas provides an indication of what could be achieved in relation to development impact more generally.

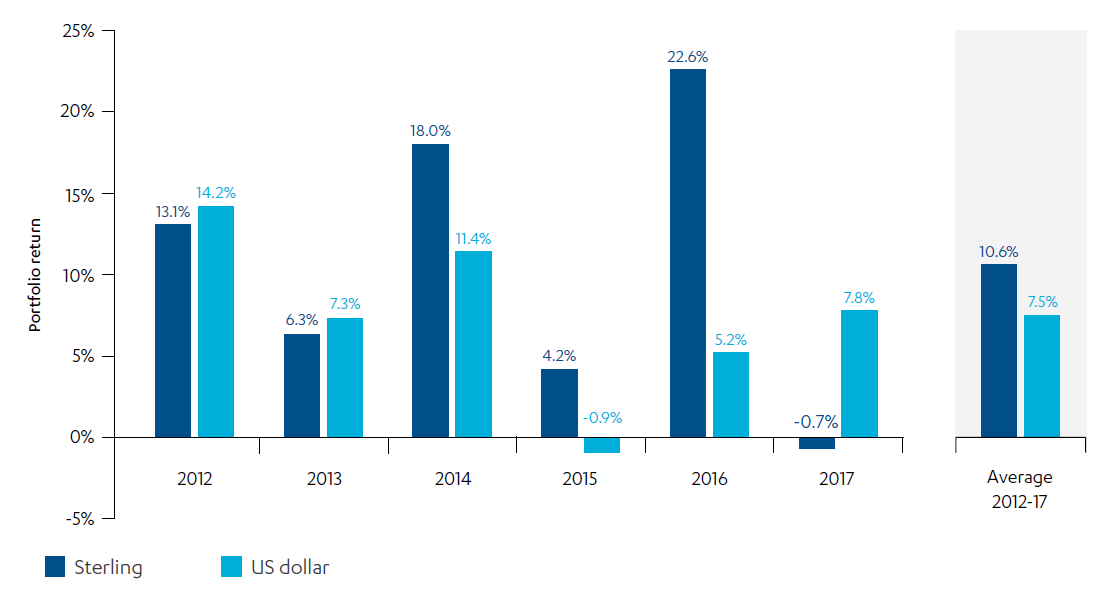

We recognise the scale of the challenge that CDC faces in delivering impact in more difficult markets while simultaneously expanding its portfolio, and the considerable progress that has been made. However, we also note that DFID has given CDC more room to pursue development impact by reducing its financial return targets to just 3.5% for its Growth Portfolio, and ‘at least break even’ overall. Yet in the six years to December 2017, CDC’s average financial returns across the portfolio were 10.6%. CDC forecasts lower returns in the coming period, due to a more challenging investment climate and because of the increasing focus on delivering impact in difficult markets. The figures nonetheless suggest that CDC could have pushed harder on achieving development impact, while still meeting its financial return hurdle.

We are encouraged by the increased emphasis on development impact, both at the investment selection stage, where DFIs have the greatest opportunity to maximise their impact, and through deploying additional resources and expertise to support the assessment and management of impact. However, we believe that these improvements could have been made earlier, and that CDC did not do enough to maximise the impact of its investments for most of the review period. We have therefore given CDC an amber-red score for the effectiveness of its $1.5 billion of new investment in low-income and fragile states between the start of 2012 and end of 2017.

Learning: How well does CDC learn and innovate?

Despite recent improvements, CDC’s learning efforts are not yet sufficiently adapted to its ambition to deliver development impact at scale in low-income and fragile states.

CDC commissioned a small number of thoughtful and strategic research projects during the review period. However, more could have been done earlier, particularly to support its priority sectors. The impressive health impact framework, published in 2017, provides an example of what could be achieved across these sectors.

Before 2017, CDC had no strategic plan for using monitoring and evaluation results to inform its investment choices and made limited attempts to investigate the development impact of investments through evaluation studies. It also did not do enough to capture learning systematically from across its investments in the most difficult markets. CDC has recently adopted new plans for strengthening its evaluation and learning practices. However, important sector-wide evaluation studies have yet to be commissioned, two years into the new strategy.

CDC has recently increased its focus on sharing learning. It has created new staff roles and revamped its website in order to help share learning, building upon an existing programme of seminars and speaker events. However, we saw only a few examples of learning on development impact informing CDC’s investment decisions and portfolio management practices. Embedding evaluation and learning as part of core working practices within CDC’s investment teams represents an ongoing challenge.

CDC is recognised as a thought leader by other DFIs in some areas, particularly on ESG issues. However, CDC could learn more from other DFIs and from relevant civil society organisations. More could also be done to share learning between CDC and DFID, in particular in relation to sector priorities and at the country level.

We have awarded CDC an amber-red score for learning, reflecting the weaknesses and gaps in evaluation and learning for most of the review period. We welcome the commitment to scaling up evaluation efforts and the production of sector-specific learning products, but believe that CDC needs to embed a stronger culture of learning across the organisation.

Conclusions and recommendations

CDC has made progress in redirecting investment to low-income and fragile states, but has not done enough to secure or monitor development gains, to improve evaluation or to apply learning. It is implementing ambitious plans to address these concerns, but these are mostly at an early stage. We have therefore awarded CDC an amber-red score overall.

We offer a number of recommendations to help CDC increase its development impact in low-income and fragile states:

Recommendation 1

CDC should incorporate a broader range of development impact criteria and indicators into its assessment of investment opportunities and ensure these are systematically considered in the selection process.

Recommendation 2

CDC should take a more active role in the management of its investments, using the various channels available to it to promote development impact during their lifetime.

Recommendation 3

CDC should strengthen the monitoring and evaluation of the development impact of its investments and the learning from this, working with DFID to accelerate their joint evaluation and learning programme.

Recommendation 4

CDC should work more closely and systematically with DFID and other development partners to inform its geographic and sectoral priorities and build synergies with other UK aid programmes to optimise the value of official development assistance.

Recommendation 5

In the presentation of its strategy and reporting to stakeholders, CDC should communicate better its approach to balancing financial risk with development impact opportunity, and the justification for its different investment strategies.

Recommendation 6

DFID’s business cases for future capital commitments to CDC should be based on stronger evidence of achieved development impact and clear progress on expanding their in-country presence.

Introduction

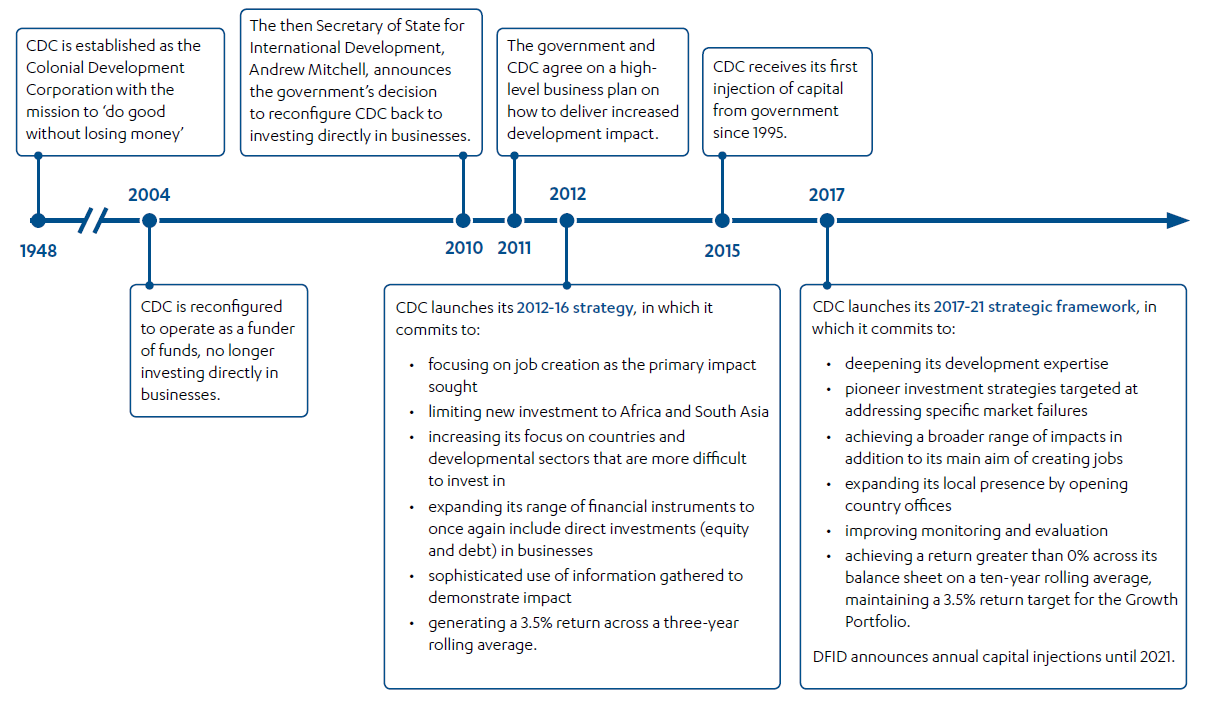

CDC Group plc is the UK’s development finance institution (DFI), wholly owned by the Department for International Development (DFID). It is the oldest DFI in the world: since its creation in 1948, it has invested in thousands of businesses in emerging markets and developing countries. Its mission today is “to support the building of businesses throughout Africa and South Asia, to create jobs and make a lasting difference to people’s lives in some of the world’s poorest places”. It is expected to generate a financial return on its investments which is then reinvested, enabling its portfolio to grow over time.

Between 2004 and 2012 CDC invested mainly through intermediary funds, and between 2004 and 2009 it focused predominantly on middle-income countries such as India and South Africa. In 2010, the then secretary of state for International Development, Andrew Mitchell, announced plans to “reconfigure” CDC to align it better with DFID’s strategic priorities. He stated, “I want CDC to be more pro-poor focused than any other Development Finance Institution, doing the hardest things in the hardest places.”

This transformation began in earnest in 2012. CDC shifted its investment focus towards lower-income and fragile states in Africa and South Asia and into sectors with the greatest propensity to create jobs. It diversified into new investment products, piloted innovative financial instruments and, in 2017, introduced a separate portfolio, the ‘Catalyst Portfolio’, to support transformational change in difficult markets.

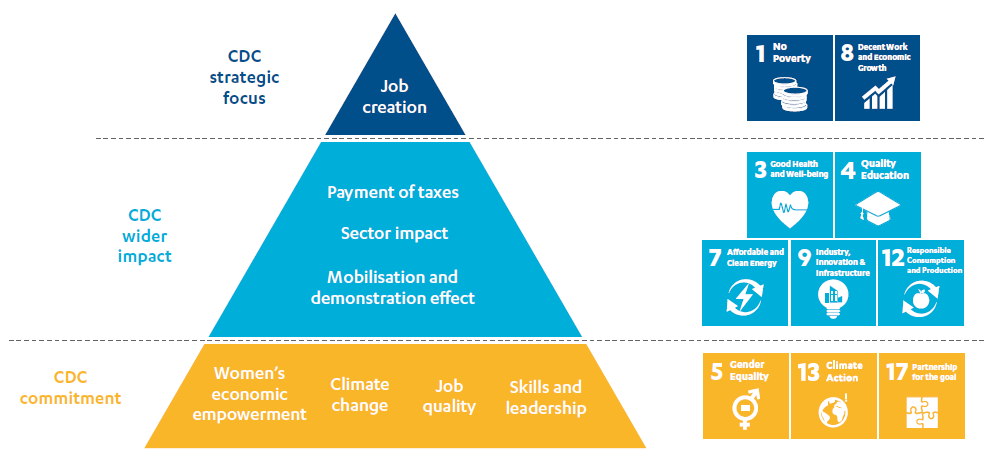

In its 2012-16 strategy, CDC’s primary focus was on delivering development impact through job creation. In 2017, CDC broadened its ambitions for development impact, for example to include support for a range of Sustainable Development Goals and women’s economic empowerment.

This shift in strategy and focus has involved wholesale organisational change at CDC, with a largely new management team, major changes in culture, systems and processes and significant recruitment – the workforce increased from just 47 in 2012 to 308 by mid-2018.

CDC has become an increasingly important channel for UK aid. Between 2015 and 2018, CDC received investments of new capital from DFID totalling £1.8 billion, and further capital injections of up to £703 million per annum are planned until 2021. CDC’s net assets are projected to increase from £2.8 billion in 2012 to above £8 billion by 2021 as a result of these capital injections and earnings.

This review covers the period from 2012 to 2018. During this time, DFID has become a more active and engaged shareholder in CDC. However, CDC remains a separate corporate entity. In particular, individual investment decisions by CDC are made independently of DFID.

Seven years on from the start of this transformation, this is an appropriate time to review the progress that CDC has made in refocusing its efforts towards promoting economic growth in low-income and fragile states. As CDC is a long-established DFI and because of the scale of new investment by DFID, we have conducted a performance review (see Box 1 for ICAI’s review types).

Box 1: What is an ICAI performance review?

ICAI performance reviews take a rigorous look at the efficiency and effectiveness of UK aid delivery, with a strong focus on accountability. They also examine core business processes and explore whether systems, capacities and practices are robust enough to deliver effective assistance with good value for money.

Other types of ICAI reviews include impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended beneficiaries, learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated on new or recent challenges for the UK aid programme and translated into credible programming, and rapid reviews, which are short, real-time reviews examining an emerging issue or area of UK aid spending.

The review explores how well CDC has reoriented its investment approach and portfolio to achieve development impact in low-income and fragile states, while still delivering its intended financial return. The review questions we have answered are set out in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does CDC have a credible approach to achieving development impact and financial returns in low-income and fragile states? | • What progress has CDC made towards establishing an appropriate and coherent strategy for achieving development impact at scale in low-income and fragile states? • How well has CDC adapted its ways of working to invest in more challenging markets while managing a rapidly growing portfolio? |

| 2. Effectiveness: How effective are CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states? | • How well does CDC select, manage and exit investments in lowincome and fragile states? • How effectively does CDC maximise its development impact while meeting financial return targets? • How well does CDC add value to individual companies, support their inclusive and sustainable growth and meet responsible investment commitments? • How effectively does CDC contribute to establishing and expanding investment markets in low-income and fragile contexts? |

| 3. Learning: How well does CDC learn and innovate? | • How well has CDC learned from global evidence on impact investment in difficult markets? • How well do CDC’s monitoring and evaluation processes drive learning within the organisation? • How well is CDC sharing learning (in support of a leadership role within the investment industry)? |

The review builds on previous parliamentary and National Audit Office (NAO) reviews of CDC (see Box 5). The 2016 NAO review focused on DFID’s oversight of CDC and CDC’s approach to managing its business. Our primary focus is on CDC’s ability to deliver results in low-income and fragile states.

Box 2: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. CDC’s investment in opportunities in developing and emerging markets can play an important role in achieving a number of SDGs.

Related to this review:

Goal 8: promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

Goal 8: promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

CDC prioritises job creation because it gives people the income, opportunity and dignity to live better lives. It aims to do this through supporting economic development and by growing businesses in developing markets where few large employers currently exist. Successful and well-managed investments could lead to significant and sustainable job creation in these markets.

Goal 1: end poverty in all its forms everywhere

Goal 1: end poverty in all its forms everywhere

CDC aims to tackle poverty through supporting businesses and through growing investment markets, thus contributing to economic growth, job creation, increased tax revenues and enhanced access to basic services.

In addition, CDC supports firms providing goods and services that are aligned with a number of other sectoral SDGs – for example SDG 3 (health), SDG 4 (education), SDG 7 (energy), SDG 9 (infrastructure, industrialisation and innovation) and SDG 13 (climate change). Due to the range of its investments, CDC’s work spans almost all the SDGs.

Methodology

The review covers the period from 2012 to 2018. It explores the reconfiguring of CDC and its strategy, approach and portfolio towards investment in low-income and fragile states.

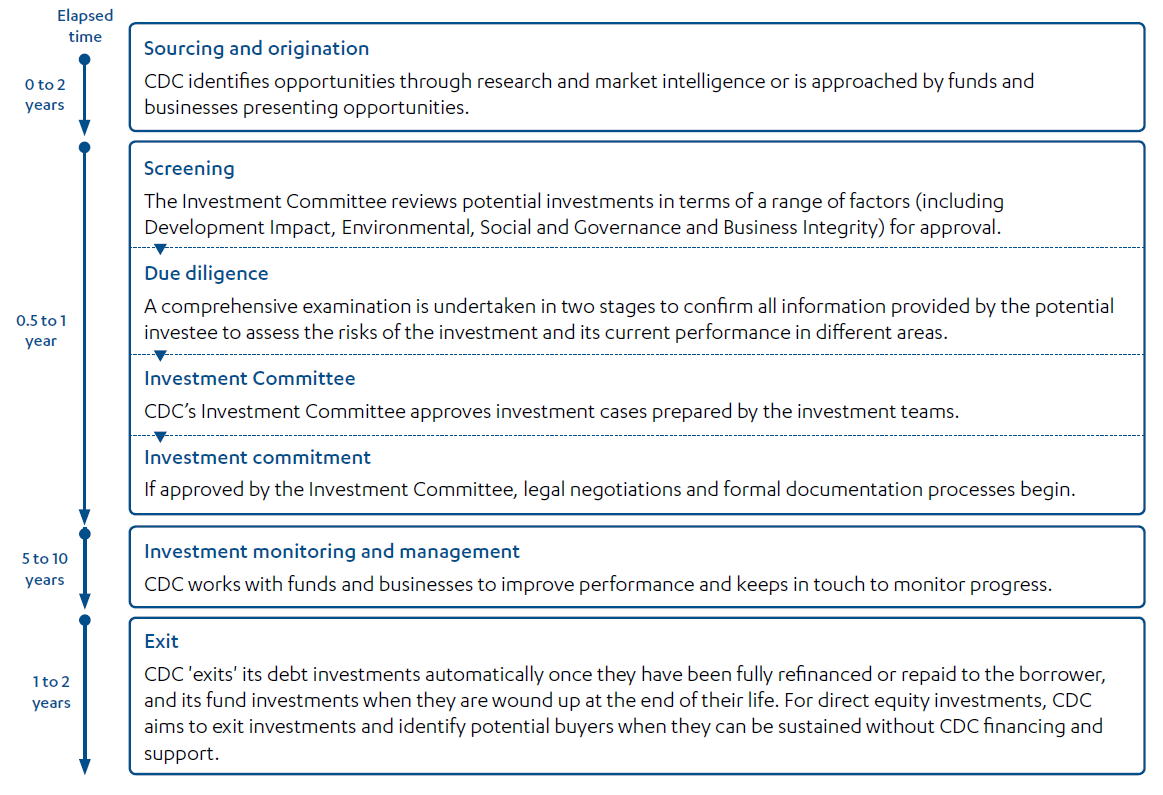

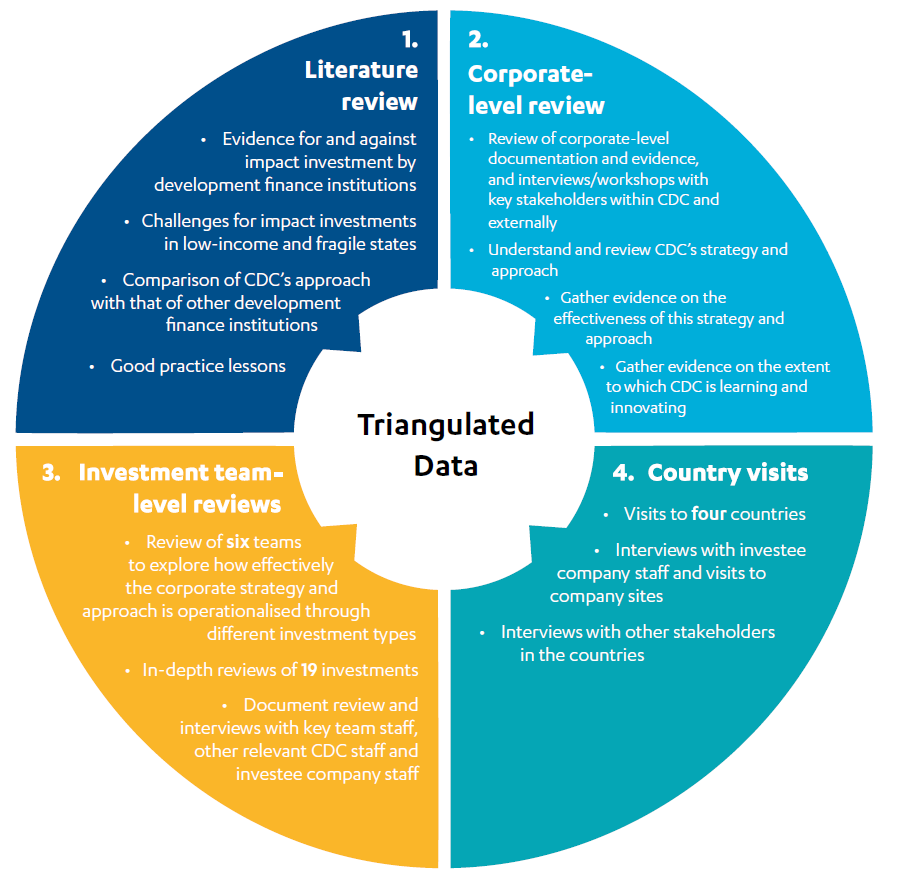

Our methodology included four components (see Figure 1), as follows:

- Literature review: We reviewed the literature on development finance institutions (DFIs), including academic literature and publications by bilateral and multilateral development institutions. This informed our understanding of current debates on impact investment by DFIs and the challenges of investing effectively in low-income and fragile states. We drew lessons from the literature on ‘what works’ in areas such as promoting development impact and on best practice in monitoring and evaluation.

- Corporate review: We assessed the effectiveness of CDC’s processes for identifying investments and measuring their development impact, and of its evaluation and learning processes, up to the end of 2018. We mapped how CDC has adapted its staffing, resource allocation and ways of working to build its capacity to work in more difficult markets and maximise its development impact. This included a review of CDC’s corporate-level documentation and management information, including relevant policies, frameworks and operational plans, and interviews with key stakeholders within CDC and DFID. We also engaged with a wide range of external stakeholders, including academics, experts and representatives of other DFIs.

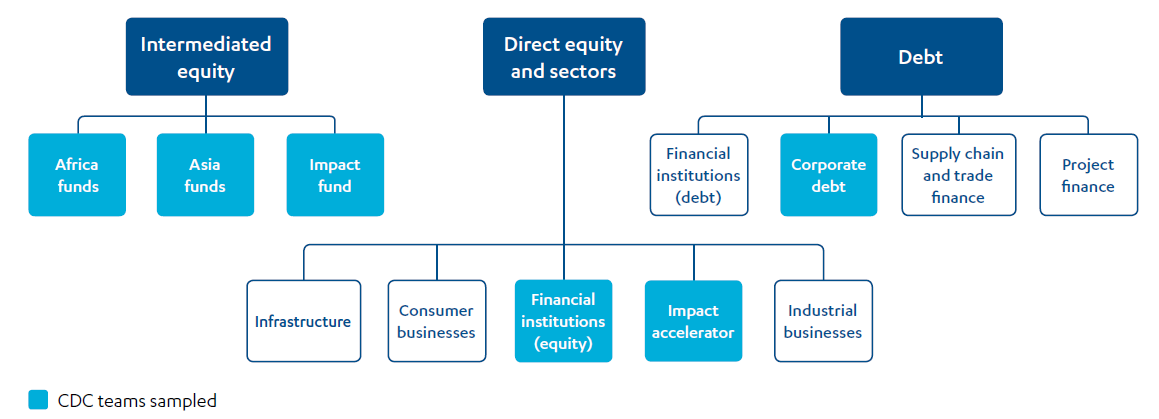

- Investment team reviews: Investment teams are the internal structures through which CDC identifies, assesses, executes and monitors investments, dealing with different product types, sectors or regions. We selected six out of CDC’s 12 investment teams and sampled 19 investments made by these teams between 2012 and 2017, to explore how CDC operationalises its approach to achieving development impact and financial returns in more difficult markets (see our sampling criteria and approach below, and further details in Annex 1). We also examined 12 potential investments that were ultimately not made. For each of the investment teams in our sample, we reviewed documentation and evidence, and interviewed relevant staff, investees and other stakeholders, in relation to the decisions to invest and the subsequent management of the investments. Where the investment was in a fund, we reviewed the documentation in relation to that investment at a portfolio level, but also reviewed an additional sample of investments made by that fund. For all sampled investments, we reviewed their development impact and the quality of CDC’s assessments of potential and achieved development impact.

- Country visits: We visited Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria and Tanzania to assess a sample of investments in each country. We interviewed CDC and investee staff, as well as other in-country stakeholders, such as DFID economic advisers and external sector experts, and explored the relevance of CDC’s investment approach to the country context, and the plausibility and significance of its reported development impact.

Figure 1: Overview of the methodology

Both our approach and this report have been independently peer- reviewed.

Sampling criteria and approach

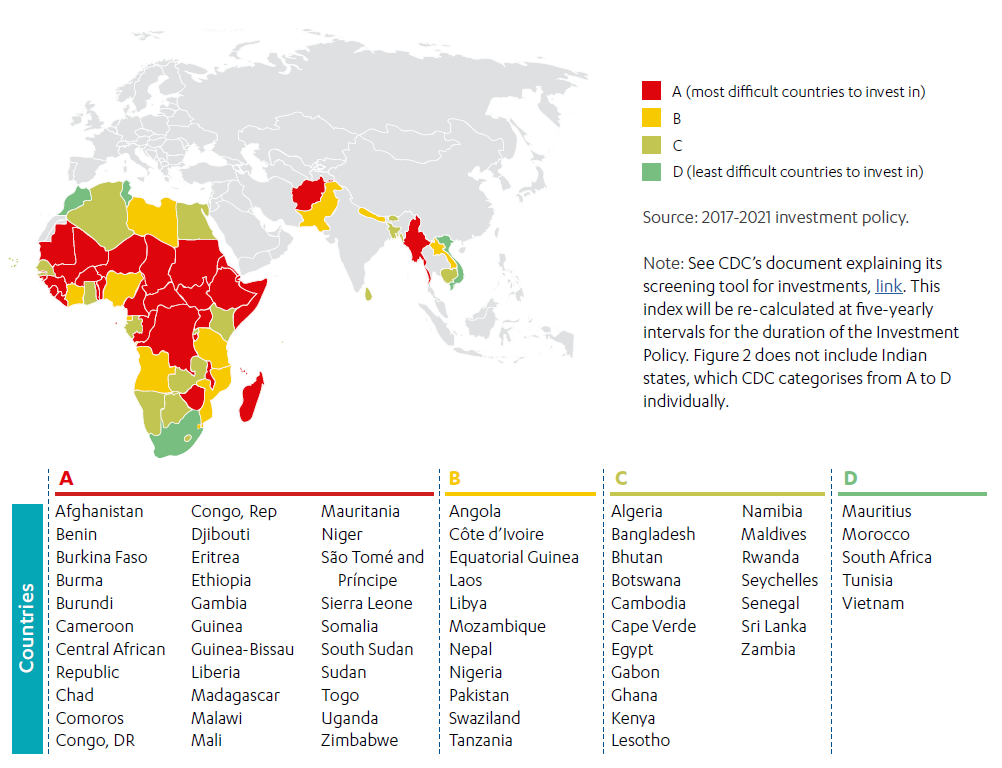

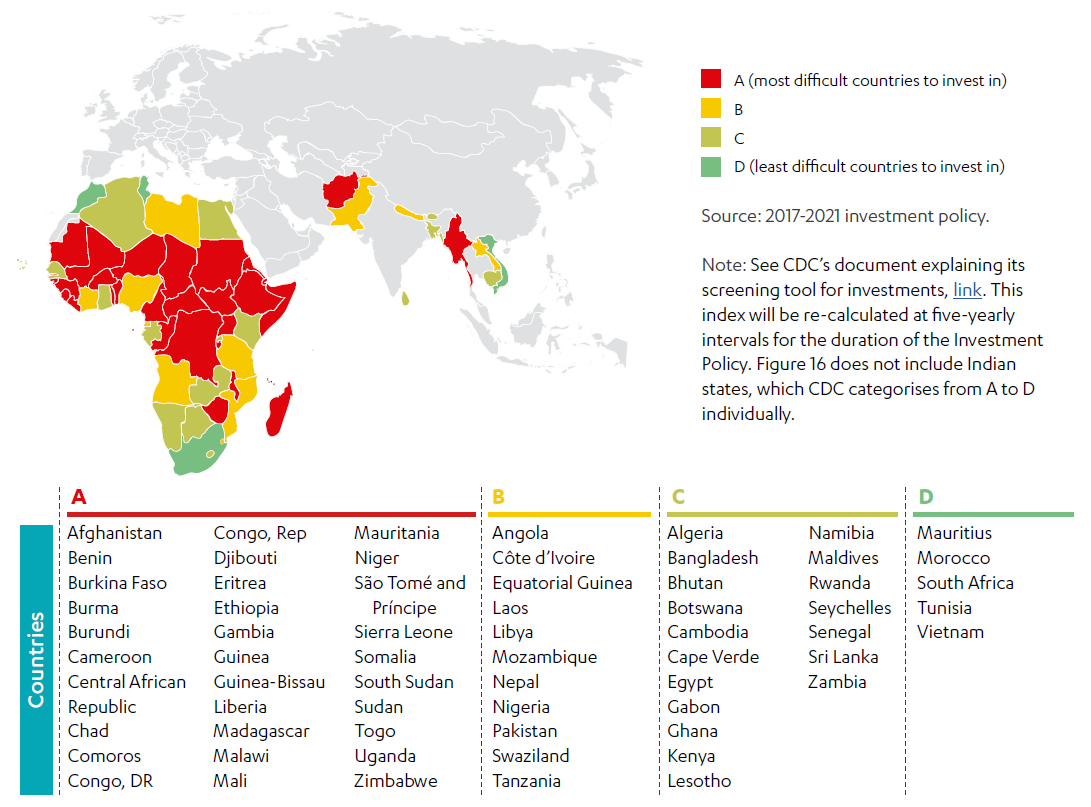

The review focuses on CDC’s progress in building its portfolio in low-income and fragile states. We used CDC’s own categorisation to identify its most difficult investment locations and selected only countries that over the period were classified as A and B – the two most difficult investment categories (see Figure 2).

We selected six out of CDC’s 12 investment teams (based on CDC’s internal organisation structure as of the start of 2018). We then selected a small, random sample of investments by these teams within the two most difficult investment categories, as well as a small sample of rejected deals, for in-depth review. (For more information on the sample of investments, see Annex 1.) The six teams were chosen based on the significance of their investment in difficult markets, their use of both direct and indirect investments, and their ‘market building’ strategies – this last factor being particularly relevant in low-income and fragile countries.

The majority of our sample was drawn from investments made between 2012 and 2016, to allow a sufficient period after the investment was made to be able to assess likely impact. However, it included a small number of fund and Impact Accelerator transactions through to December 2017.

Figure 2: CDC’s categorisation of countries in which it invests in by investment difficulty

Box 3: Limitations to the methodology

Some of the changes to CDC’s resourcing, systems and processes were only set in motion with its new strategic framework in 2017. It is therefore premature to assess the effectiveness of these new developments. In these circumstances, we have focused on likely effectiveness, based on analysis of the strategies and approaches being pursued and early evidence of performance, triangulated through interviews with expert stakeholders.

We reviewed a sample of 19 out of 345 new investments made between 2012 and 2017. This sample is not representative of CDC’s portfolio or of its investments in more challenging markets. However, these investment reviews, complemented by our review of CDC’s investment strategies and processes, enabled us to make informed judgments about CDC’s approach to investing in low-income and fragile states. We did not review any new investments made in 2018 because it was too early to assess their impact or effectiveness, although we reviewed the processes involved in their selection.

Some of the information that CDC holds on its investee companies is commercially sensitive. In writing this report, we have respected CDC’s obligation to keep this information confidential. This has not restricted our ability to make informed judgments.

Background

The rise of development finance institutions

Since the early 2000s, donors have made more use of development finance institutions (DFIs) to promote private sector development and economic growth in developing countries. Between 2002 and 2014, new investments by DFIs grew from $10 billion to around $70 billion per year – an increase of 600%. This is equivalent to half the value of all annual global official development assistance (ODA). An important part of the rationale for DFIs is that they can successfully demonstrate the viability of investment in developing country markets that are neglected by private investors and the financial markets – thereby helping to mobilise or ‘leverage’ larger flows of private finance. They therefore have a key role in the ‘billions to trillions’ agenda, which recognises that the Sustainable Development Goals will require a huge increase in funding from many sources, not just ODA.

DFIs deploy development capital through loans, equity investments, guarantees and other investment instruments to generate development impact and financial returns. They may also provide grants and non-financial support. The main types of investment instruments used by CDC are set out in Box 4.

Box 4: Main investment instruments used by CDC

Debt: CDC provides loans to businesses and projects in its priority sectors in four ways: project finance (with tenors of up to 18 years), corporate finance, trade finance and loans to financial institutions.

Direct equity: CDC provides capital funding to investee companies by purchasing shares (‘equity’) in companies. Where it is a significant shareholder, CDC generally has a position on the company’s board of directors and so is able to influence the strategy and operations of the investee.

Intermediated equity: CDC continues to invest via funds that invest in a range of companies, helping to develop local investment capacity and mobilise capital from commercial investors. The funds are able to invest in more and smaller businesses than CDC is able to directly.

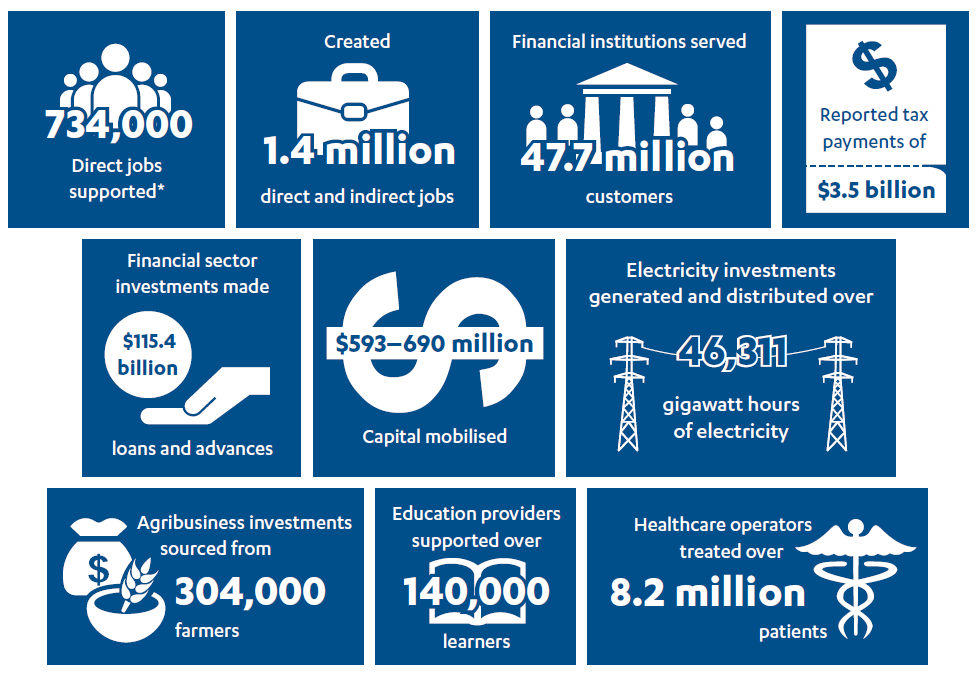

Through their investments, DFIs aim to contribute to a range of development impacts. Their objectives include creating jobs, expanding the provision of goods and services, increasing tax receipts for developing country governments, building investment markets and improving the management practices of investee firms and funds. It is widely believed that, by contributing to private sector development, DFIs promote economic development and poverty reduction.

However, there is a relative lack of rigorous evidence of DFIs’ impact on poverty. This is due in part to methodological challenges in establishing the links between a portfolio of investments and wider development outcomes, but also to gaps and weaknesses in monitoring and evaluation. For example, in 2011, the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group concluded that fewer than half of the investments made by the World Bank’s DFI, the International Finance Corporation, were accompanied by the systematic collection of evidence on their impact on poverty reduction.10 Historically, some DFIs have also been criticised for focusing too much on middle-income countries such as India, where investment opportunities are relatively plentiful.

Box 5: Previous scrutiny of CDC and its development impact

In the past decade, a number of scrutiny bodies have undertaken assessments of CDC and its development results:

- In 2008, the National Audit Office (NAO) published a report on DFID’s oversight of CDC. It concluded that CDC had “made a credible contribution to economic development” while also encouraging the engagement of other foreign investors. However, it highlighted the challenges that CDC faced in converting its pipeline of potential deals into investments, raised questions about its additionality, and noted that further evidence was needed on whether CDC’s investments were an effective way of providing direct or indirect economic benefits for the poor.

- A report by the Public Accounts Committee, which built on the NAO report together with an evidence session with senior officials from DFID and CDC, also found that there was limited evidence of CDC’s effects on poverty reduction, as well as emphasising the need to invest more in low-income countries.

- In 2011, the International Development Committee published a report on the future of CDC. It raised concerns as to whether CDC was delivering sufficient development impact. In particular, it questioned whether some of its investments duplicated those that would have been made anyway by private investors, potentially distorting rather than building investment markets. It also found that over half of its investments were in middle-income countries, and too few in sectors that most benefit the poor.

- In 2016, the NAO conducted another review of CDC. It found that CDC had made progress in aligning its portfolio with DFID’s priorities, but that more evidence was needed on its development impact. It criticised DFID for not doing enough to evaluate its impact.

- This was followed by another report from the Public Accounts Committee, which commented on DFID’s failure to seek independent advice before its 2015 capital injection in CDC and the lack of targets reflecting the varied nature of CDC’s portfolio. It also noted the difficulty of reaching firm conclusions about CDC’s development impact.

The increasing focus on economic development, the private sector and CDC in the UK’s aid strategy

The growing importance of development capital and leveraging private sector investment to address global challenges has been reflected in developments in UK aid. DFID has rebalanced its portfolio towards the promotion of economic development, with an increasing emphasis on growth and job creation as engines of poverty reduction. DFID’s Structural Reform Plan in 2010 announced wealth creation as one of its main priorities. In 2011, DFID’s new Private Sector Development Strategy stated that it would engage with firms, directly and indirectly, to help them generate jobs, opportunities, income and services for poor people. Promoting global prosperity is also one of the strategic priorities of the UK’s 2015 aid strategy, while new economic development strategies in 2014 and 2017 set out DFID’s priorities on economic development, including affirming CDC as a major partner in this work.

CDC’s 2011 Business Plan and 2012-16 Investment Policy, formulated and issued jointly with DFID, signalled important changes to CDC’s strategy, with the intention of increasing its development impact. This heralded a major transformation in CDC’s organisation and investment activities.

Figure 3: The history of CDC

From 2012, CDC shifted its investment focus away from middle-income countries and towards lower-income and fragile states in Africa and South Asia, in sectors that create the most jobs. It also diversified into new investment products, investing directly as well as through funds, and piloted innovative financial instruments. In 2017, it introduced a separate ‘Catalyst Portfolio’ to support transformational change in difficult markets.

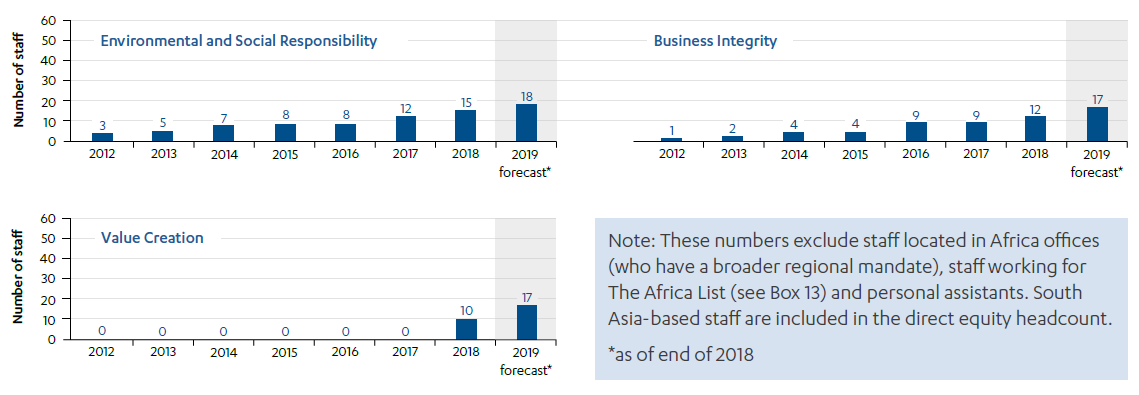

New product teams were established to manage direct investments, and a new Development Impact team was formed. Most recently, CDC set up a value creation strategies team to focus on its commitments in the areas of skills and leadership, job quality, gender equality and climate change, working alongside the established environmental and social responsibility (E&S) team. The E&S team ensures that companies meet minimum environmental and social standards, as well as supporting those with the potential to improve their practices through what CDC terms its ‘value additionality’ offering.

These changes involved major adjustments in the leadership and management of CDC, a considerably expanded workforce and wholesale changes in the culture, systems and practices of the organisation.

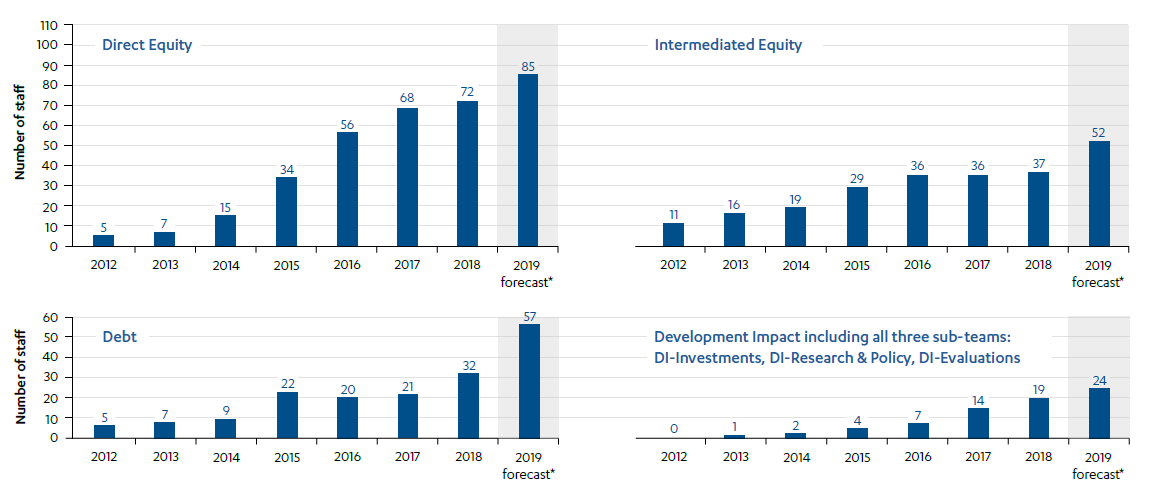

Figure 4: Evolution of staffing of CDC’s teams relevant to the investment process

Figure 5: CDC organisational structure

* MedAccess and Gridworks are fully-owned subsidiaries of CDC, attached to the Debt and Infrastructure teams but with their own management and staff

Source: CDC

Before 2011, CDC had operated largely independently of DFID, recycling its financial returns into new investments. During the review period CDC and DFID have begun to work more closely together.

CDC contributes to poverty reduction first and foremost by creating jobs and catalysing sustainable economic growth. It also aims to reduce poverty by improving access to essential goods and services, both directly through investment in private sector service provision and indirectly through its contribution to increasing tax revenues.

To support its focus on more challenging markets, and priority sectors, in Africa and South Asia (see Figure 2), CDC worked with DFID to develop new criteria for screening and prioritising potential investment, including a Development Impact Grid. This grid is CDC’s primary tool for screening investment opportunities to ensure that it focuses on the countries that are most in need of investment, and on the sectors in those countries that have the greatest potential for job creation (see Box 6 in the Findings section for a more detailed description). Further details of CDC’s investment process are provided in Annex 2.

Recognising CDC’s potential to support its economic development strategy, DFID made a series of investments of new capital between 2015 and 2018 – the first CDC had received for 20 years – totalling £1.8 billion. DFID has committed to further injections through to 2021, by which time CDC’s net assets are projected to grow to more than £8 billion, compared with £2.8 billion in 2012. While DFID has committed £620 million per year of new capital to CDC, with an option to increase this to £703 million per year, the actual amounts drawn down to date by CDC have been lower: £375 million in 2017 and £360 million in 2018.

The objective of these additional commitments was to enable CDC to scale up its investment, while giving it the capacity to accept higher levels of investment risk and lower returns as it moved into riskier markets and sectors. To facilitate this, DFID introduced a separate ‘Catalyst Portfolio’ (alongside the main commercial portfolio, now called the ‘Growth Portfolio’) and also reduced CDC’s overall financial return hurdle to ‘greater than break even’ to encourage CDC to take greater financial risks in return for greater development impact. CDC’s financial return hurdle for the Growth Portfolio remained at 3.5%.

CDC’s new strategic framework for 2017-21 reinforces the organisation’s commitment to maximising development impact in the most challenging markets. The framework includes plans for a series of ‘market building strategies’ to help tackle market failures in specific sectors (as part of the Catalyst Portfolio), as well as new commitments on women’s economic empowerment, job quality and climate change, consistent with DFID’s priorities across its economic development work.

As a result of these developments, the significance of CDC’s role within DFID’s economic development strategy, and in the UK’s aid portfolio as a whole, has grown substantially over the period of this review.

Findings

Does CDC have a credible approach to achieving development impact and financial returns in low-income and fragile states?

In this section we examine the progress that CDC has made between 2012 and 2018 in establishing a coherent strategy for achieving development impact at scale in low-income and fragile states, while at the same time managing a growing portfolio of investments.

There is a clear development case for CDC’s strategic shift towards low-income and fragile states

DFID’s policies for economic development since 2012 and its business cases for the recapitalisation of CDC set out a broad but credible rationale for providing development capital in poorer countries. This is based upon the financing gap in meeting the Sustainable Development Goals, the continuing barriers to private investment in much of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (including the high levels of risk faced by private sector investors), and the importance of job creation as a mechanism for lifting people out of poverty.

In our review of DFID’s approach to promoting inclusive growth in Africa, we praised the department’s ambitions for achieving transformative growth and creating jobs at scale, while noting the many practical difficulties associated with this. Development capital plays a central role in these ambitions.

Within the literature and in the countries we visited, we found strong evidence of the need for additional capital – in particular for ‘patient’ capital that is invested for the long term, without the expectation of early returns. CDC investees and external experts identified the high interest rates on bank lending and the limited availability of longer-term loans in countries such as Nigeria and Malawi, as well as the relatively underdeveloped private equity markets across Africa, as barriers to the growth of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). There is consequently strong demand for support from development finance institutions (DFIs) such as CDC, which offer finance on terms that are generally more favourable than those offered by commercial banks and investors, often in combination with the provision of technical assistance.

In sub-Saharan Africa, countries such as Nigeria and Kenya have seen growth in their private equity markets in recent years (Kenya shifted from B to C in terms of CDC’s categorisation of investment difficulty over the review period). However, there are sharp regional variations within countries. In Nigeria, for example, experts told us that private equity investment was concentrated in Lagos and Abuja, as well as in sectors such as property and infrastructure. Growth in investment markets remains constrained by risk factors such as currency volatility, falling commodity prices and unhelpful financial regulation. We heard from a country representative of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) that private equity funds in sub-Saharan Africa consequently face challenges in raising finance from private investors.

CDC’s shift in strategy also helps to respond to successive concerns raised by the National Audit Office (NAO) and the International Development Committee (IDC) that CDC’s investment in middle-income countries may not have been fully benefiting the poor, and risked displacing commercial investment (see Box 5).

There is therefore a strong case for the decision to refocus the CDC portfolio towards low-income and fragile states. Nonetheless, it is also clear that investing at scale in these much more difficult markets and delivering development impact and financial returns where these are often difficult to predict has involved significant new challenges for CDC.

Since 2012, CDC has successfully reoriented its investment activities more towards low-income and fragile countries

CDC’s plans for the period of this review reflect a progressive focus on low-income and fragile states. CDC’s strategy for 2012-16 was to invest exclusively in Africa and South Asia, with an aspiration to shift CDC’s capital to more challenging regions over time. The more recent strategic framework, covering the period 2017-21, commits CDC to increasing the volume of its investments in poorer and more fragile countries and regions, where its “capital is most needed”. DFID’s 2015 and 2017 business cases for new investment in CDC also reaffirm CDC’s commitment to investing in fragile and conflict-affected countries.

The introduction of the Development Impact Grid in 2013 has played an important role in helping CDC to focus new investment on low-income and fragile countries. By weighting countries according to their level of investment difficulty, the grid provided a means of encouraging investment towards poorer countries. The grid includes 33 fragile and conflict-affected countries (according to DFID’s classification), which in most cases are both low-income and high-risk (the exceptions being Egypt, Bangladesh, Kenya and Cambodia). The grid also provides a simple but useful tool for encouraging investment in sectors with the greatest potential for job creation in these countries (see Box 6).

Box 6: CDC’s Development Impact Grid

In order to strengthen the development impact potential of its investment activities, CDC worked with DFID to develop a Development Impact Grid, an investment screening tool that scores potential investments based upon country and sector characteristics. The grid was designed to guide investment to those countries and states most in need of finance and those sectors most likely to create jobs and economic growth.

Country ranking: The grid divides the countries and Indian states in which CDC invests into four categories of investment difficulty – from A to D, with A being the most difficult investment environment (see Figure 2). It measures investment difficulty by applying an equally weighted index combining five indicators: (i) market size, (ii) income level, (iii) available credit to the private sector, (iv) ‘doing business’ rankings of the regulatory environment for the private sector and (v) a composite measure of state fragility designed by DFID.

Sector ranking: The grid divides CDC’s priority business sectors

into three categories of job creation potential – high, medium

and low, depending on their propensity to generate employment

directly or indirectly (see Figure 2).

It then combines the sector and country rankings into a score from 1.00–4.00, based upon the matrix shown here. DFID set CDC an overall Development Impact hurdle score of 2.4 in 2012 and 2017.

CDC is now more geographically concentrated on difficult markets, including fragile and conflictaffected states, than other DFIs. In our interviews with external stakeholders, including other DFIs, economic think tanks and civil society organisations, CDC’s reorientation towards more challenging markets and greater development impact was both recognised and welcomed.

New investment products, increasing staff capacity and lower financial targets have facilitated CDC’s reorientation towards low-income and fragile states

In order to successfully expand its portfolio into more challenging and complex markets, CDC recognised that it must work harder to find suitable investments, provide its investees with a broader range of support and manage its portfolio in new ways. CDC’s 2012-16 strategy set out plans for introducing new investment products and building up its staffing levels and expertise. DFID supported this reorientation towards riskier markets by lowering CDC’s financial targets.

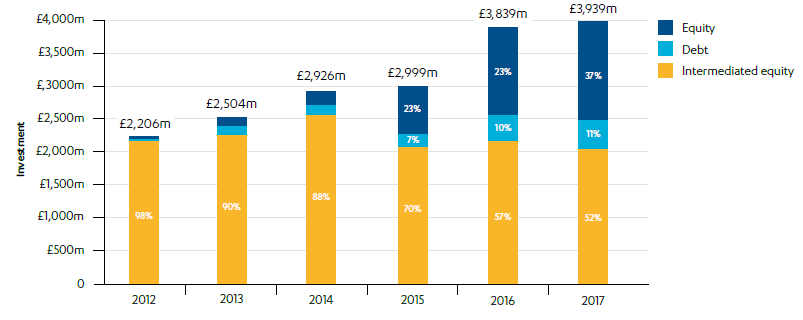

A key part of CDC’s transition strategy was to diversify its investment products to include direct equity and direct debt funding, in addition to indirect investments through private equity funds. Between 2012 and Q3 2017, 61% of all new CDC investments were made through direct equity and 22% through direct debt, with only 17% through funds. There was strong agreement among those consulted for the review that this shift has given CDC more flexibility to respond to the needs of businesses, including early-stage SMEs, in more difficult markets in Africa. Reflecting this, we found that CDC’s direct investments have higher average Development Impact Grid scores than its indirect investments via funds.

Figure 6: Composition of the portfolio by investment type

Source: Annual Accounts 2017, CDC Group plc, p. 5.

To enable it to deliver these strategies, and in particular to originate and manage direct investments, CDC has significantly expanded its management and operational capability. Staff numbers have increased from 47 employees in 2012 to 308 by July 2018, with 79 staff now working on direct equity. CDC nonetheless told us that it had underestimated the time that it would take to build up the resources required to implement its new strategy. Progress had therefore been slower than planned, for example on building the direct debt team. CDC plans to continue building its resources and capability, aiming to employ 450 staff by 2021.

To facilitate greater risk-taking in pursuit of development impact, DFID has progressively reduced CDC’s financial return targets. Before the review period, CDC’s target for financial return was 5%. From 2012, CDC was required to achieve a minimum ten-year average return of just 3.5%. This enabled CDC to build up a higher-risk portfolio and pursue investments in more challenging markets and nascent sectors, with lower short-term returns but long-term growth potential. The 2017 Investment Policy left the existing ‘profitability hurdle’ for the Growth Portfolio in place (a ten-year average return of at least 3.5%) but also introduced a second, lower profitability hurdle for CDC as a whole, requiring the Growth and Catalyst Portfolios taken together to achieve a positive net profit (in other words a return of more than 0%), measured over a ten-year period. Depending on the relative size of the two portfolios, these two hurdles would therefore allow the Catalyst Portfolio to operate at a significant loss.

CDC is piloting some innovative financial instruments, but is yet to develop a clear and comprehensive strategy for identifying and supporting opportunities in challenging markets

In building up its portfolio in low-income and fragile states, a key challenge facing CDC is in finding a sufficient pipeline of suitable businesses in which to invest. The economies are typically smaller, the business environment is more challenging and many firms do not meet CDC’s stringent environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards. CDC is therefore required to take a more active approach to identifying and developing new investment opportunities.

In the poorest and most fragile states investable opportunities are rare, and often have to be created, sometimes over many years… as countries become more developed, investable opportunities increase.

Investing to transform lives: Strategic framework 2017-2021, CDC, 2017.

CDC is piloting some innovative financial instruments that it hopes will increase its ability to operate in more challenging markets:

- Platform investments, through which a single investment by CDC can support multiple businesses. Under this model, CDC makes a direct equity investment in a company which it knows and trusts in one of its priority sectors. This new capital enables the investee to invest in other opportunities in the sector, often in different countries (see Box 10 on CDC’s investment in Globeleq).

- Permanent capital vehicles, which are a means of making longer-term equity investments beyond the standard ten-year private equity model, in order to help businesses grow in difficult markets. CDC’s first investment in a permanent capital vehicle was made in 2017, with a $20 million investment in Solon Capital Holdings in Sierra Leone. Solon Capital Holdings has since made investments in two of CDC’s priority sectors – education and construction – among others.

- Risk-sharing facilities, designed to increase small business access to commercial finance. The first such facility was an innovative $50 million partnership with Standard Chartered Bank in Sierra Leone (see Box 7).

- A supply-chain finance initiative, which aims to improve the cash flow of SMEs within domestic supply chains in Africa and South Asia, again in partnership with Standard Chartered Bank. In August 2018, the first supply chain facility was approved ($150 million, of which CDC contributed $75 million). Suppliers in Nigeria and Ghana will be the first to benefit from the programme. Other countries are also in the pipeline.

- A new £65 million grant facility available to all investees in the Catalyst and Growth Portfolios to access technical assistance support, as well as for testing solutions to systemic issues affecting multiple CDC investees, for example in relation to environmental sustainability or gender issues.

Box 7: Innovative support for SMEs through a risk-sharing facility in Sierra Leone

In response to the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone in late 2014, CDC and Standard Chartered Bank developed a risk-sharing facility to provide SMEs access to capital that was unavailable in the country at the time. Through the risk-sharing facility, CDC assumes a share of the risk of financial loss alongside Standard Chartered Bank. This allowed the bank to lend the larger amounts necessary to keep SMEs operating through the crisis.

The original facility provided $26 million in working capital to nine companies, enabling them to scale up the supply of essential consumer items (including staples such as rice, flour and cooking oil, hygiene products and building materials) in areas where supplies had been badly affected by the Ebola crisis. The facility was renewed and expanded in 2016, 2017 and again in 2018 following these early successes, with $33 million provided in 2018 to 13 companies. The expected benefits include job creation and higher levels of trade.

Although individually promising, we are concerned that these innovations are unlikely to drive the scale of investment and development impact that CDC is seeking in low-income and fragile countries without being underpinned by a more comprehensive strategy or approach for sourcing investment opportunities and supporting investees in the most difficult markets.

CDC is moving towards a stronger sector focus, but could be more transformational in its approach

DFIs such as CDC aim to achieve their most important development impact by unlocking private sector investment, building markets and promoting the transition towards more productive economies. Successive DFID economic development strategies and business cases for CDC, as well as CDC’s own strategies and plans, have emphasised this catalytic role. In its 2017-21 strategic framework, CDC asserts that “life-changing progress comes from growth that transforms economies” and commits to investing “to transform whole sectors”.

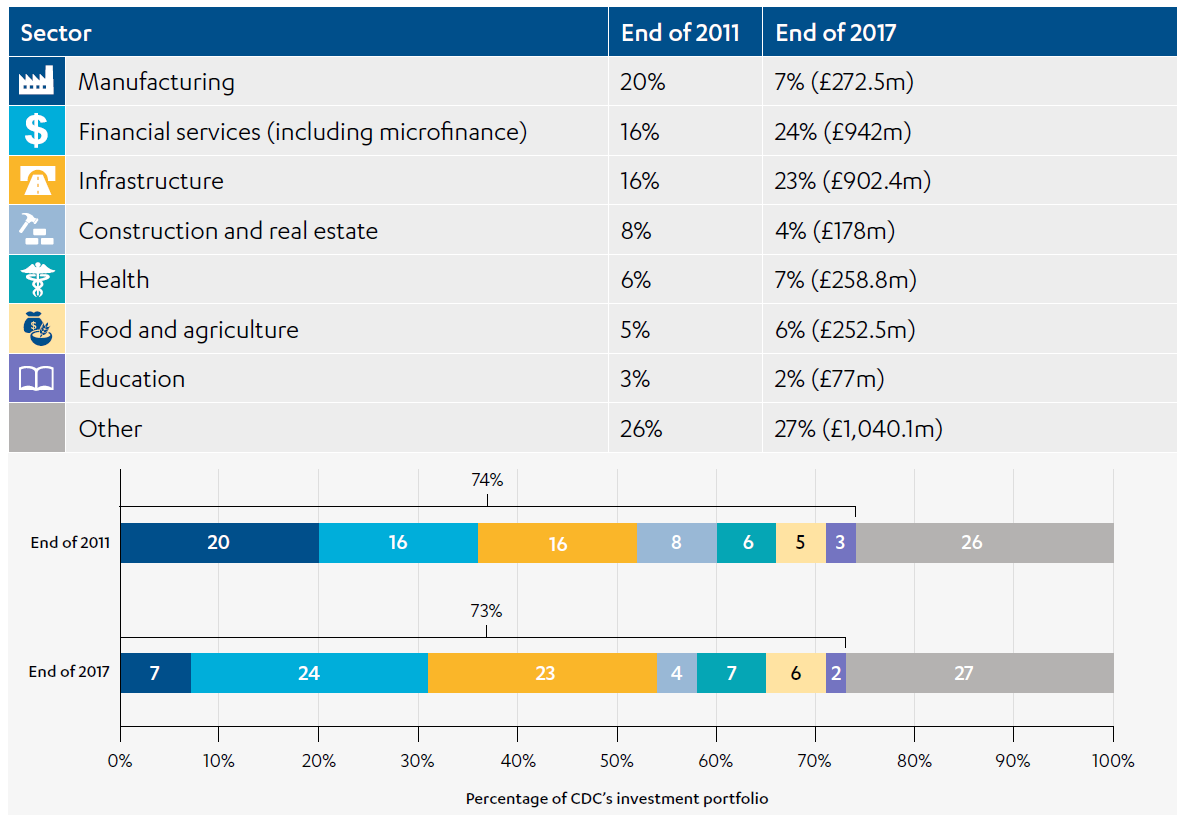

From 2013, the Development Impact Grid encouraged CDC to focus its investment on specific sectors that create the most jobs. CDC’s 2017-21 strategic framework confirmed that CDC will focus on seven priority sectors: construction, education, financial institutions, food and agriculture, health, infrastructure and manufacturing. To support this sector focus, CDC has produced a variety of market analyses, investment criteria and some strategy documents for a limited number of sub-sectors. However, it has been slower to develop comprehensive sector strategies to guide its investment teams and help support more transformational impact, working with other partners.

In 2017, CDC introduced a range of ‘market building strategies’ under its Catalyst Portfolio in an attempt to support more transformational change. The initial pilot strategies covered a limited number of specific sector priorities, including access to medicines and other health commodities, energy and climate change adaptation. DFID told us that they have asked CDC to be even more ambitious with its investments under its Catalyst Portfolio.

One example where ICAI believes CDC could show more ambition is in its Off Grid Solar strategy. This is helping to improve access for the approximately 1.2 billion households that lack electricity worldwide, but is focused on the pay-as-you-go home solar sector, where there is existing demand from lower-middle-income consumers and interest from other investors. Reflecting this, CDC also invests in this sector under the Growth Portfolio. CDC’s investments under the Catalyst Portfolio are distinguished by providing riskier local currency debt loans, to help support the sustainable growth of the nascent sector. CDC says that it is also investing in financially riskier and larger-scale mini-grids, which the World Bank currently invests in to help bring power to poor rural communities, through other strategies.

CDC now has plans to develop comprehensive strategies for its seven priority sectors in 2019, which will set out how it will build, manage and monitor a portfolio of impactful investments (including through market building activities) in each sector. Sector specialists are being recruited into CDC’s direct equity team and it is expected that they will work closely with DFID’s sector specialists.

We welcome these important developments but believe that more could have been done earlier in key sectors to help drive transformational change. A number of commercial fund managers and academic experts we consulted also thought that CDC could have done more to address specific development challenges and capital constraints in sectors such as healthcare, agriculture and affordable housing, and to encourage transformation, working with country governments and other DFIs.

CDC has been slow to build its country presence outside of India, and to develop geographic strategies or priorities

CDC has been slow to build a country presence in its priority markets. From 2013, CDC re-established offices in India, and has since developed closer interactions with DFID as a result. In 2013, CDC also hired its first Regional Director for Africa, charged with supporting its expansion into direct equity and debt investments across the continent. The 2016 NAO report emphasised the importance of CDC expanding its physical presence in Africa and South Asia, but noted that CDC did not yet have a fully developed plan for expansion. At the end of 2017, out of 266 CDC staff, ten staff were based in India, but only seven in the whole of Africa.

The wide cross-section of expert stakeholders that we spoke to consider a strong in-country presence important for engaging with SMEs, originating investment opportunities and supporting active portfolio management to help firms succeed and create development impact.

CDC now has firmer plans in place to expand its overseas presence. It has prepared an Africa Coverage Strategy, which sets out how its Africa personnel will support CDC’s investment agenda in these more difficult markets, and is projecting 33 employees there by 2021, alongside 43 in South Asia. The aim is to replicate the capability of CDC’s offices in India across its office network.

Plans for Africa currently involve regional offices in Johannesburg (established in 2016), Lagos and Nairobi, and single representatives in Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Egypt and Côte d’Ivoire. The selection of countries took account of portfolio management needs, market potential, development needs, the UK government’s existing footprint and accessibility. However, initial plans for a representative based in the Democratic Republic of Congo were dropped when the nominated employee moved to Ethiopia. CDC says that it intends to expand to four or five more countries in the next five years.

Figure 7: CDC planned overseas presence and coverage 2018-2021

We recognise the significant challenge of building an effective local presence in difficult markets, particularly at a time of considerable change and expansion throughout the organisation in the UK. But we believe that more could have been done earlier, given the emphasis on growing direct investment in low-income and fragile states, and the subsequent capital increase approved by DFID. CDC made direct investments in Africa totalling $1.6 billion between 2012 and 2017. CDC’s weak country presence there has meant that these investments have been largely unsupported by country-based staff.

We consider the expansion of a strong country presence to be an urgent priority for CDC. Failure to do so could undermine plans for the continued scale-up of CDC’s investment activities in Africa and the broadening of its development impact there.

CDC’s 2017 strategic framework notes that the significant differences in investment readiness between countries requires a tailored approach. An internal strategy document from 2016, concerning CDC’s investments in fragile and conflict-affected states, outlined plans to foster transformational growth at country level by coordinating multiple investments in key sectors, as CDC did in Sierra Leone following the Ebola crisis when it developed a risk-sharing facility with Standard Chartered Bank (see Box 7). However, CDC has not prepared detailed strategies or plans for any individual country or geography. Instead, CDC is now producing ‘country perspectives’ for key markets, based upon a synthesis of economic data and consultation with DFID.

We recognise the difficulty of producing comprehensive plans without a strong local presence. However, we see considerable value in developing a more comprehensive analysis of the investment challenges and opportunities in individual countries or geographies, ideally in conjunction with the country governments and with DFID and other DFIs and development partners, and agreeing shared priorities to help improve the investment climate, build markets and guide investment.

CDC has moved from a narrow focus on job creation towards a broader understanding of development impact, but there is more work to do to fully operationalise this

CDC’s primary method of selecting investments with the potential to deliver development impact in low-income and fragile countries is to prioritise sectors with the greatest potential for job creation. From 2012, DFID encouraged CDC to introduce a strong focus on jobs as the primary route to poverty alleviation, given for example that the rate of job creation in Africa is well below the growth rate of its labour force. Working with DFID, CDC commissioned an analysis to identify sectors with a higher propensity to create jobs, and then designed its Development Impact Grid to prioritise these. It has recently updated this analysis with fresh data (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: CDC’s priority sectors

By focusing narrowly on job creation, CDC may have missed opportunities to maximise its development impact. A report commissioned by DFID in 2016 expressed a concern that “one possible disadvantage [of the grid] would be if it led to an excessive focus on jobs at the expense of other areas of development impact”. While it concluded that CDC used the grid flexibly in selecting its investments, the report recommended that additional development impact areas should be tracked. Some external stakeholders we interviewed also suggested that CDC should give more consideration to addressing economic inequality (including across geographical areas and between social groups), to help ensure that CDC’s investments benefit the poorest.

CDC now recognises the need for a broader approach to development impact. Its 2017 strategic framework considers development impact at three levels – people and communities, companies and local economies, and broader capital markets (covering mobilisation). There is a stronger emphasis on the wider contribution of CDC’s investments to poverty reduction and gender equality, including through providing a clearer articulation of the links with the Sustainable Development Goals (see Figure 9). CDC’s development impacts are to be achieved primarily through a combination of job creation, sector effects and the introduction of four ‘strategic initiatives’ – women’s economic empowerment, climate change, job quality and skills and leadership.

Figure 9: How CDC aims to contribute to the SDGs

Source: CDC strategic framework 2017-21.

To support this broader emphasis, CDC has embedded 12 development impact professionals in its investment teams, with recruitment under way for two further posts. Since January 2018 these staff have been responsible for formulating a more comprehensive ‘development impact case’ for each potential investment at the screening stage, and for identifying appropriate performance measures to help monitor and manage the impact of CDC’s investments throughout their lifecycle. CDC’s Development Impact team (alongside the E&S and Value Creation Strategies teams) now report to CDC’s newly appointed Chief Impact Officer, who sits on CDC’s executive committee. These improvements should enable CDC to better understand and enhance its development impact.

There is more work to do to fully operationalise this new thinking on impact across CDC’s investment practices. The development impact case is a largely qualitative narrative, and CDC’s accompanying Investment Process Overview (2018) does not set out how evidence of development impact should be weighed against other investment criteria. CDC does not yet have a consistent set of wider development impact measures, beyond the grid score and a limited set of sector metrics, that could be systematically applied to its investments and help guide the decision-making of investment managers from deal origination through to approval.

A number of other DFIs score their investments against a wider range of impact factors, including additionality, promotion of corporate social responsibility, and the potential for mobilising other investment finance. FMO, the Dutch DFI, told us that they now specifically ‘label’ whether their investments contribute to Sustainable Development Goal 10 (reducing inequality), and also adopt targets for investment that promote gender equality and smallholders. The IFC recently announced a new assessment framework, the Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring system (AIMM), which takes a comprehensive view of development impact and quantifies potential impact across a range of measures.

Within the scope of this review, it is not possible for ICAI to assess the relative merits of alternative approaches to investment assessment. CDC’s initial rollout of the development impact cases provides an important opportunity for internal and external learning and for refining CDC’s procedures in this area.

As part of its new approach to development impact, CDC is paying closer strategic attention to job quality and gender equality, but there is room for improvement

CDC has addressed job quality over the review period through the E&S team’s compliance requirements, which are based on IFC performance standards and cover issues such as core labour conditions, working hours, pay and grievance mechanisms. Deficiencies are then addressed via a legally binding E&S action plan. The E&S team has also produced several helpful due diligence guides and products over the period.

Although this compliance activity is important, we believe that CDC could do more to strengthen its approach to measuring and supporting job quality, in support of the International Labour Organization’s broader definition of ‘decent work’ and Sustainable Development Goal 8.53 We note that the NAO report of 2016 found that CDC had been considering how to measure job quality since 2012, but without making much progress. By 2018, CDC told ICAI that its strategic initiative on job quality was behind its newer work on gender, and that it had not yet completed its strategy for this area. CDC continues to engage with other DFIs on this issue, as part of the Let’s Work Partnership administered by the World Bank.

Before 2018, CDC’s objectives related to gender were focused on working with investees to help them comply with the social requirements in its ‘Code of Responsible Investing’, some of which disproportionately affect women. However, we found limited evidence in our sample of investments from this period of objectives specifically related to gender. The 2017 strategy included a new emphasis on furthering women’s economic empowerment, in support of Sustainable Development Goal 5 (gender equality), in keeping with DFID’s economic development strategy. A gender strategy was introduced in 2018 to help raise awareness across CDC of the potential of its investments to promote women’s leadership, job quality and access to finance and services. This also committed CDC to helping to tackle more systemic barriers to women’s empowerment. CDC is continuing to improve its approach to this issue. It recently introduced an investment objective in relation to gender, joining other G7 DFIs in committing to mobilise $3 billion for businesses supporting women.

Building on the non-optional requirements in its E&S Code, CDC currently frames its work on women’s economic empowerment (as well as support for other strategic initiatives such as job quality) as part of its value additionality support. Different aspects of value additionality are pursued where specific opportunities are identified, rather than being scored or assessed systematically as part of producing each development impact case. This targeted approach is a helpful initiative to focus efforts but may miss opportunities that a more comprehensive approach might identify. CDC says that it recognises some of the tensions and overlap between its development impact and value additionality work and is looking to further harmonise its approach.

CDC has developed some investment instruments to target the poor, but could adopt a sharper focus on poverty reduction across its portfolio

In an effort to target the poorest in society, DFID appointed CDC to manage two new investment vehicles, the Impact Fund and the Impact Accelerator, in 2013 and 2015 respectively. In September 2017, these DFID funds were transferred onto CDC’s balance sheet, as part of the Catalyst Portfolio. Both are designed to invest in businesses that provide goods, services and income-earning opportunities for vulnerable and underserved groups, or to work in more challenging places (such as conflict-affected areas) with limited investment activity. Investments by these funds are expected to be higher-risk but with long-term commercial potential, and to help catalyse other investments. Investees have access to technical assistance, as well as financial support. There are examples of investments in nutrition, agribusiness, renewable energy and construction in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Malawi and Rwanda.

Box 8: Examples of CDC’s Impact Fund and Impact Accelerator

The Impact Fund

- CDC committed $15 million to Novastar Ventures East Africa Fund in 2014. Novastar Ventures is a Nairobi-based venture capital firm, which invests in innovative, early-stage businesses in the education, healthcare, agribusiness, food and water sectors, targeting low-income communities. The fund’s investments include Sanergy, a Kenyan franchise which provides high-quality sanitation facilities in Nairobi’s urban slums, and Bridge International Academies, which operates a chain of low-cost nursery and primary schools in Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria and India.

- In 2017, CDC committed $15 million to the Fund for Agricultural Finance in Nigeria (FAFIN), managed by Sahel Capital, which targets SMEs across the agricultural value chain in Nigeria. FAFIN made five investments in the agribusiness sector in Nigeria between 2015 and 2018, including in a dairy producer and processor, a poultry farm, a cassava starch processing company and a rice producer and processor, which work with smallholder farmers and/or employ local labour. According to Sahel Capital, FAFIN-backed businesses support over 400 jobs directly and more than 1,200 indirectly. Of the direct jobs supported, 77% are taken by women and young people. One of these investments is located in northern Nigeria, where there is limited investment activity.

The Impact Accelerator

- Agricane is an agricultural engineering and development company founded in 1996. It owns three farms totalling 3,700 hectares of land in Malawi. CDC invested $5.5 million in 2017 to help the company set up remedial irrigation works in a commercial sugar cane plantation, to address soil salinity problems. The investment helped preserve 88 permanent and 150 seasonal jobs. There is the potential to develop a platform relationship with Agricane, which would allow CDC to establish a pipeline of investments in Malawi without requiring its own local presence.

Though innovative, these two investment vehicles remain small in scale compared with CDC’s Growth Portfolio. In 2017 they accounted for just 6% of CDC’s new commitments.

Figure 10: Composition of CDC’s overall portfolio, 2018 (%)

Beyond the Impact Fund and Impact Accelerator, we found mixed levels of engagement in CDC in relation to the challenge of reaching the poorest. The latest direct equity strategy includes an objective to support businesses that serve the poor and that work in poorer regions, alongside companies with the potential for growth. There is no explicit reference to the poor in the objectives of CDC’s other product strategies, although the intermediated equity strategy does make reference to supporting companies graduating from the informal economy. Some of the CDC staff we interviewed thought that CDC could use its influence as an investor more to encourage pro-poor initiatives in investee companies, for example where CDC has board representation as a result of a direct equity investment or where it is co-investing alongside a fund investment.

In our investment sample we identified a number of possible opportunities to increase the pro-poor focus of individual investments which had not been actively encouraged by CDC. For instance, in Nigeria we found promising initiatives around corporate social responsibility that had not been fully implemented or sustained, and innovative ideas for providing products and services to underserved areas that had not been pursued. We also saw scope for more proactive support for women’s employment, particularly within sectors and occupations where women are under-represented. Some of these examples related to intermediated equity investments through fund managers. In these cases, CDC does not ordinarily have a direct relationship with investees, making it more difficult to influence their strategy and practices.

Positively, CDC’s new development impact professionals have been tasked with helping investment managers with ‘impact management’. This includes identifying opportunities to enhance impact throughout the investment lifecycle, as well as improving CDC’s monitoring of development impact.

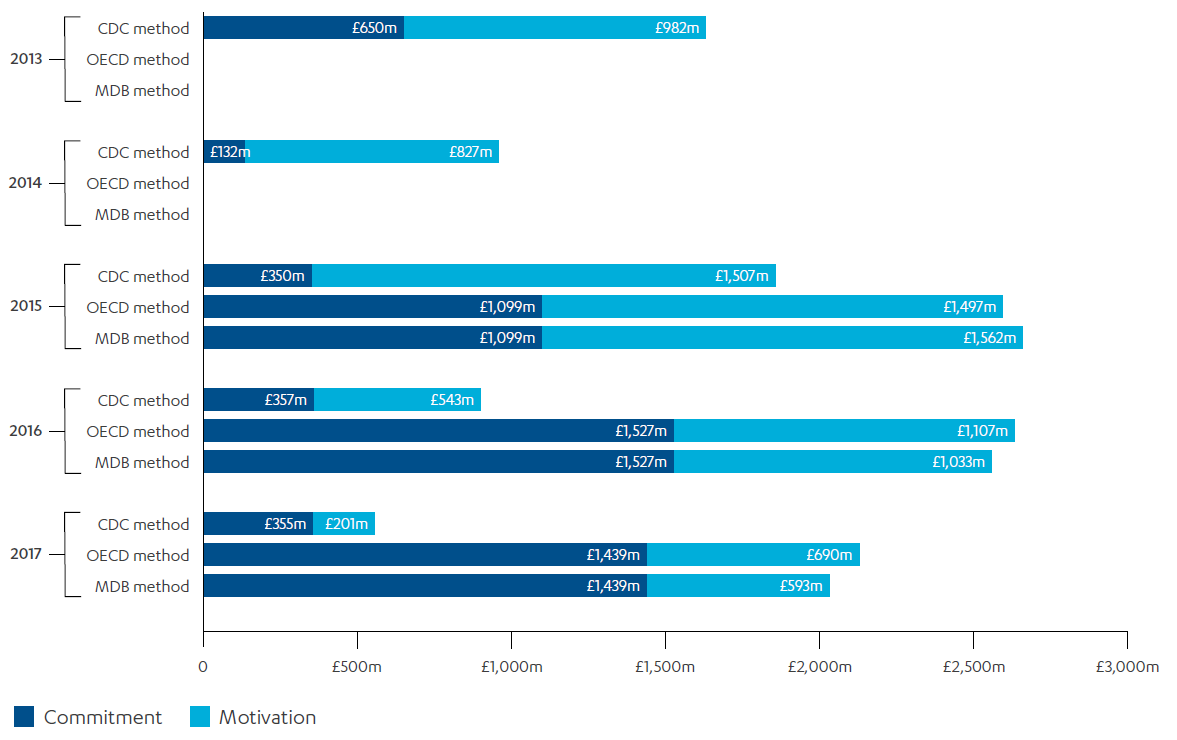

Until very recently CDC has had no overarching strategy for encouraging the mobilisation of private finance

DFIs achieve development impact at scale by demonstrating that commercial investments are viable in sectors and areas neglected by the market, thereby unlocking larger financial flows. This is particularly challenging in low-income and fragile states, where there are fewer sources of private capital to influence.

CDC has no overarching strategy for mobilising private finance. Its 2017-21 strategic framework includes mobilising private capital among its seven key goals, but it only talks in general terms about how CDC will look for new ways to do this, and there are no specific plans for difficult markets. DFID suggested that CDC put in place a specific strategy for mobilising private finance by the end of 2018. CDC recently confirmed that it had submitted a proposed strategy to its Board in November 2018.