DFID’s Approach to Supporting Inclusive Growth in Africa

1. Purpose, scope and rationale

The purpose of this review is to examine DFID’s approach to supporting inclusive growth in Africa, with a particular focus on job creation.1 The review will explore DFID’s inclusive growth diagnostics, its country strategies and its economic development portfolio, in order to assess how the department is delivering on its commitments to economic inclusion and job creation. It will also assess whether DFID is being effective in applying knowledge and evidence to achieve value for money in its investments. The review will cover DFID’s economic development work in Africa from 2010 onwards and cover both country programmes and centrally managed programmes by the Economic Development Directorate and Africa Regional Department. It will not cover programming in situations of conflict and fragility, which raise distinct challenges.2

This review is timely given DFID’s commitment to scaling up its investment in economic development. According to DFID’s 2014 strategy, UK aid seeks to “eradicate poverty and transform economies by helping poorer countries achieve a secure, self-financed, timely exit from poverty through economic development.”3

This is a learning review that will explore new and emerging areas of DFID’s economic development portfolio in Africa, to assess the efficacy of the current approach and inform future decision-making.

2. Background

Since the mid-1990s, many countries across sub-Saharan Africa have enjoyed strong economic growth, with particularly high growth levels in countries such as Nigeria, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Angola.4 In 2014, Africa’s low-income countries averaged GDP growth of 5.8%, buoyed by improved macroeconomic management and high global demand for commodities.5 Economic growth has lifted significant numbers of African citizens out of poverty – a 2016 World Bank report estimates that the proportion of the population living in poverty on the continent fell from 57% in 1990 to 43% in 2012.6 However, growth has been concentrated in a few sectors and geographic areas, and has not been particularly inclusive in nature.7 As a result, the rate of poverty reduction has lagged behind the rate of population growth, causing the absolute number of Africans living in poverty to increase.8

DFID considers economic growth to be the principal enabler of long-term poverty reduction and has committed to giving it a more central role in its development assistance. In 2013, the then International Development Secretary, Justine Greening, stated that accelerating progress in economic growth was essential if the goal of zero extreme poverty by 2030 was to be achieved.9 In line with the Global Goals’ principle of ‘leaving no one behind’,10 DFID has committed to promoting growth that is inclusive, with an emphasis on growth that generates jobs and prosperity for the poorest.11 The new Secretary of State has committed to promoting “economic development, prosperity, jobs and empowerment in many of the poorest parts of the world”.12 DFID’s stated long-term aims for economic transformation involve growth in both manufacturing (including commercial agriculture and food processing) and services. In recent years, DFID has significantly increased its cross-departmental spending on economic development, more than doubling expenditure from around £800 million in 2011-12 to £1.8 billion in 2015-16.13

Following an initial mapping and categorisation of DFID’s programming, we determined that its economic development portfolio is composed of 268 programmes over our review period. This amounts to nearly £4.7 billion in expenditure.14 This was spent across 14 thematic areas and 12 bilateral country programmes, as well as through regional and centrally managed programmes.

Table 1: Categorisation of DFID’s economic development portfolio over the review period

| Department | No. of programmes | Expenditure (£m) |

|---|---|---|

| Private Sector Department | 4 | £1,020 |

| Africa Regional Division | 40 | £602 |

| Africa country programmes | 185 | £2,657 |

| Other regional and centrally managed programmes | 39 | £409 |

| Total | 268 | £4,688 |

3. Review questions

The review is built around the evaluation criteria of relevance and effectiveness.15 It will address the following questions and sub-questions:

Table 2: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: Does DFID have a credible approach to promoting inclusive growth and jobs in Africa? |

|

| 2. Effectiveness: How effectively does DFID programming target the poor and marginalised? |

|

| 3. Learning: How well has DFID learned from its research, diagnostic work and past programming to inform its approach to inclusive growth and job creation? |

|

4. Methodology

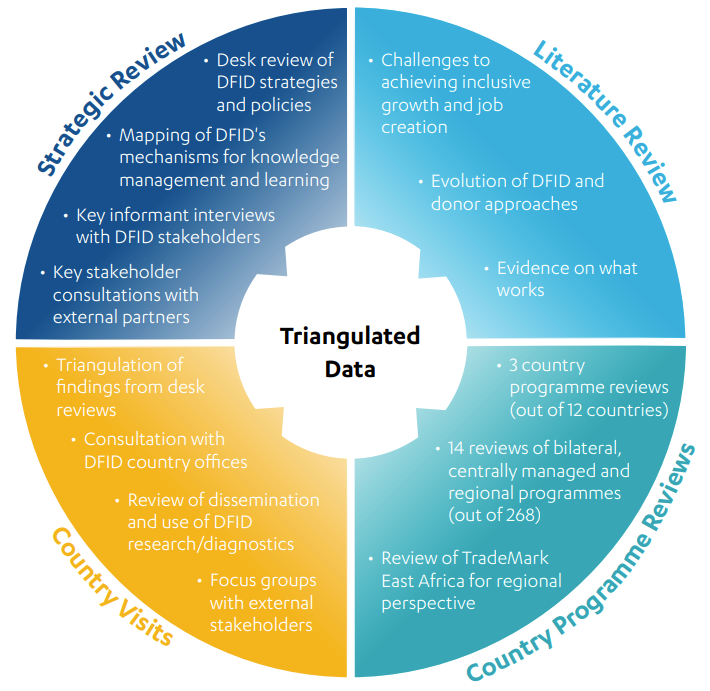

Our methodology will consist of four main components, summarised in the figure below. Together, these four components will enable us to examine the interaction between DFID’s diagnostic work, its investment in research and evidence and its strategies and programme development, at both the central and country levels.

Figure 1: Methodology

Component 1 – Literature Review: We will summarise available evidence on: i) the challenges to achieving inclusive growth and job creation in Africa; ii) the evolution of donor and DFID approaches; and iii) existing evidence and knowledge on the effectiveness of interventions. The literature review will provide historical and contextual background for our assessment of the relevance and coherence of DFID’s strategy against existing knowledge on effective interventions for inclusive growth and job creation. It will also inform our assessment of DFID’s investments in research and evidence collection.

Component 2 – Strategic Review: We will review DFID’s overall strategies and approaches for promoting economic growth and benchmark them against international evidence to assess their relevance and likely effectiveness in promoting inclusive growth and jobs. This will include: i) a qualitative assessment of DFID’s strategies and guidance related to inclusive growth and job creation, by reference to evidence from the literature review on which interventions work; ii) a mapping and review of DFID’s mechanisms for knowledge management and learning, to assess how well DFID has invested in knowledge to strengthen its approach; and iii) consultation with DFID stakeholders in London and external partners (academics; development non governmental organisations (NGOs); implementing partners) to elicit expert views on the relevance and effectiveness of DFID’s approach to inclusive growth and job creation.

Component 3 – Programme Desk Reviews: We will examine the composition of three DFID country portfolios on economic development in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zambia. We will assess the credibility of each country portfolio, by referring to evidence from each country on growth dynamics and the barriers to inclusive growth and job creation. We will assess how diagnostics, research and learning have informed country strategies and programming. We will explore the extent to which each country programme has built up a body of data and learning on how to achieve impact and value for money (including information on the economic return on different programming options). To provide a regional growth perspective, we will also review two additional TradeMark East Africa (TMEA)16 programmes in Burundi and one programme from Tanzania.

Component 4 – Country Visit: To test key lines of enquiry and tap into locally generated assessments of DFID’s work on growth and jobs, we will visit Zambia and Tanzania. We will spend approximately one week in each country, to conduct detailed consultations with DFID country offices on their use of diagnostic tools, their development of country strategies and portfolios, and to consult with DFID’s implementing partners. This will enable us to triangulate information collected on the relevance and effectiveness of particular programmes through our desk reviews. Key informant interviews with external stakeholders (government counterparts, the private sector, academia, donors and civil society organisations (CSOs)) will be used to verify the relevance and effectiveness of DFID in-country approaches towards inclusive growth. DFID’s influencing will be tested through a review of country-level mechanisms for the dissemination of DFID research and diagnostics, and key stakeholder consultations held to validate the value of this work.

For components two to four, interviews with external stakeholders (including critical voices) will triangulate our findings, deepen our insights and reduce any potential bias that comes with this review’s reliance on UK government documents and interviews.

5. Sampling approach

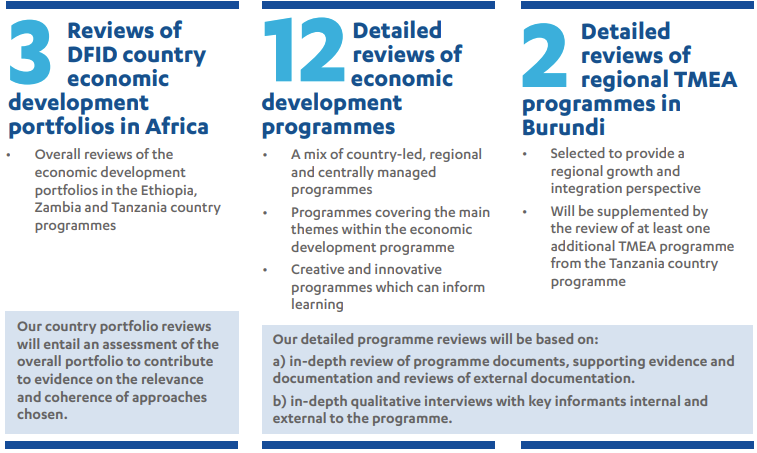

We have chosen a sample of three DFID country programmes (Ethiopia, Zambia and Tanzania) out of 12 in sub-Saharan Africa with relevant portfolios. We will conduct country visits to Zambia and Tanzania, while Ethiopia will be a desk review. These three countries have been selected so as to offer a representative view of the contexts in which DFID operates, covering:

- Two sub-regions (Southern and Eastern Africa)

- different growth patterns (an emerging industrial sector in Ethiopia, a strong natural resource sector in Zambia and a predominantly agricultural economy in Tanzania)

- the main DFID economic development programmes, by thematic area.17

Within these country portfolios, we will select 12 programmes for in-depth review once we have received detailed information on each country portfolio from DFID. The sample will cover a range of thematic areas and a mixture of country-led and centrally managed programmes. In addition, we will include two TMEA programmes from Burundi and one TMEA programme from Tanzania, to assess how regional growth issues are addressed within the DFID portfolio. Overall, the sample covers a third of the relevant DFID country programmes and 17% of the economic development portfolio for Africa by planned expenditure.

Figure 2: Our sampling

6. Limitations to the methodology

Sample size: DFID’s definition of economic development programming is broad. To manage the scope of the review, we have restricted the sample to programmes that map most directly onto our review questions. While the country programmes selected are representative of the overall portfolio, the sample covers only 17% of all planned expenditure in the Africa portfolio. Given the sample size, we will be explicit in our report about the extent to which our conclusions can be generalised. This particularly relates to fragile states, which have not been systematically included.

Attribution: The impact of DFID programming on inclusive growth and job creation may be difficult to isolate from other possible causes. We will explore literature and data in each country, to identify rival hypotheses and assess whether DFID has made a plausible contribution.

7. Risk management

| Risk | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| Disruption to fieldwork plans due to unforeseen events | There is a possibility that either of the two proposed field visits could be cancelled or delayed due to unforeseen events. If this occurs, one of the country visits will be downgraded to a desk review. |

8. Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI Lead Commissioner Tina Fahm with support from the ICAI Secretariat. The review will be subject to quality assurance by the Service Provider consortium.

Both the methodology and the final report will be peer reviewed by Frances Stewart from Queen Elizabeth House, Oxford University. Frances is a former Director of Oxford University’s Department for International Development and an expert on economic development, inequality and poverty with a distinguished publication history.

9. Timing and deliverables

The review will be executed within nine months starting from early August 2016.

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach Paper: November 2016 |

| Data collection | Country visits: 21 November – 16 December 2016 Evidence pack: January 2017 Emerging Findings Presentation: February 2017 |

| Reporting | Final report: April 2017 |

Footnotes

- ↩ There are no widely agreed definitions of ‘Inclusive Growth’, however, the term stems from a recognition that prioritising economic growth alone cannot meet the development needs of poor people, as it fails to directly address issues such as inequality and unemployment.

- ↩ This review will not cover CDC Group (CDC Group PLC – formerly known as Commonwealth Development Corporation), or Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG) investments as reviews of these programmes have been recently undertaken by the National Audit Office (NAO). See Department for International Development: investing through CDC, National Audit Office, 2016, link and Oversight of the Private Infrastructure Development Group, National Audit Office, 2015, link.

- ↩ Economic development for shared prosperity and poverty reduction: a strategic framework, DFID, January 2014, link.

- ↩ 2014 African Transformation Report – Growth with Depth, ACET, 2014, link.

- ↩ Sub-Saharan Africa Region, World Bank, 2013, link.

- ↩ Poverty in a rising Africa, World Bank, 2016, link.

- ↩ See footnote 6.

- ↩ See footnote 6.

- ↩ Justine Greening: The UN High Level Panel Report on the Post 2015 Development Framework, [speech] 2013, link.

- ↩ See UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 8: Promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment and decent work for all, link.

- ↩ Economic development for shared prosperity and poverty reduction: a strategic framework, DFID, January 2014, link.

- ↩ Priti Patel, Statement in Parliament, 14 September 2016, link.

- ↩ This includes funding to CDC Group and PIDG as well as bilateral programmes, and is on top of indirect funding on economic development through core contributions to multilateral organisations.

- ↩ The team defined the economic development portfolio as programmes with a 50% or more spend on economic development. It excluded programmes in the pre-pipeline stage, those that were completed prior to 2012, work in fragile states (apart from Burundi) and the provision of development capital investment. As it includes some programmes which were started prior to 2010 and were still active in 2012, it is not possible to provide a definitive time period for the portfolio.

- ↩ Based on the OECD DAC Evaluation criteria. See OECD DAC 1991, Principles for Evaluation of Development Assistance, link.

- ↩ TradeMark East Africa (TMEA) is funded by a range of development agencies with the aim of growing prosperity in East Africa through trade, link.

- ↩ The main themes include infrastructure, governance and security, agriculture and business development, energy and power, access to finance, transport, trade, urban, development of other productive sectors, education, manufacturing, research, forestry and fishing.