DFID’s contribution to improving maternal health – An impact review

1. Purpose, scope and rationale

ICAI has decided to conduct a review of DFID’s contribution to improving maternal health. It will be an impact review, as this is a mature area of UK aid programming for which there is a broad range of evidence about what works. It is also an area in which DFID has set itself ambitious targets and reported significant results.

ICAI impact reviews involve a thorough assessment of the programmes that underpin DFID’s results claims and the significance of their development impact. They include a strong focus on evidence of results and on the quality of DFID systems used to capture that evidence.

The purpose of this review is to explore the contribution that the UK has made to achieving international goals on maternal health. The review will assess the validity of DFID’s results claims in particular countries and the overall UK aid contribution to achieving global targets.

The review will focus on DFID’s programming related to maternal health from the 2010-11 financial year onwards. This corresponds to the final phase of efforts to meet the Millennium Development Goals and to the initial phase of the Sustainable Development Goals, and includes programming linked to DFID’s most recent results framework for maternal health (2011-2015).1

The review will examine DFID policies, strategies and guidance, and assess selected country programme portfolios, relevant multi-country programmes and multilateral contributions, in the context of international consensus about what works to improve maternal health. It will also look at the results of DFID’s health system strengthening work and its impact on the maternal-neonatal continuum of care and on maternal health outcomes. The primary focus will be on health sector interventions, including family planning, but the review will also consider whether this programming is anchored in wider strategies to address other determinants of maternal health – such as water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), nutrition, and the empowerment of women and girls.

2. Background

Maternal health continues to be one of the most pressing development challenges. Each year, nearly 300,000 women worldwide die from causes related to pregnancy or childbirth, mostly in developing countries, where the maternal mortality rate is on average 14 times higher than in OECD countries.2 Pregnancy-related conditions are the number one killer of 15- to 19-year-old girls worldwide, and most of these deaths are preventable.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about 25 million unsafe abortions are undertaken globally each year. Africa accounts for 29% of unsafe abortions but 62% of related deaths. Many of the women who survive an unsafe abortion will nevertheless experience serious, long-term medical consequences.4 Poor maternal health is linked directly to poor neonatal health, and a mother’s death has a major impact on the wellbeing and life prospects of her children.

Substantial progress was made internationally during the Millennium Development Goal period, although it fell short of the global target to reduce maternal mortality by three quarters. The maternal mortality ratio fell by 44% between 1990 and 2014,5 to 216 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births globally,6 though progress within and between countries varied significantly.7 The Sustainable Development Goals now include the more ambitious target to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to below 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030. Maternal health is linked closely to other Sustainable Development Goals and targets, including on neonatal and child mortality (target 3.2), universal access to sexual and reproductive health care services (target 3.7), universal health coverage (target 3.8), gender (Goal 5) and nutrition, safe water and sanitation.8

The Goals include a commitment to ‘leaving no one behind’, an equity principle strongly promoted by the UK government which entails focusing development efforts on the most vulnerable and disadvantaged.9

DFID’s 2015 single departmental plan includes a commitment to “work to end preventable child and maternal deaths”, alongside pledges on improving nutrition (including for women of childbearing age), water and sanitation, and helping an additional 24 million girls and women to access family planning between 2012 and 2020.10

This is a mature area of programming for DFID, which published its first maternal health strategy in 2004.11 In 2010, DFID committed to saving 50,000 maternal lives over the period 2011 to 2015.12 It has reported aggregate results from the UK aid programme on skilled birth attendance (5.6 million; 2011-15),13 additional women reached through modern methods of family planning (8.5 million; 2012-17)14 and total maternal lives saved (103,000; 2011-14).15

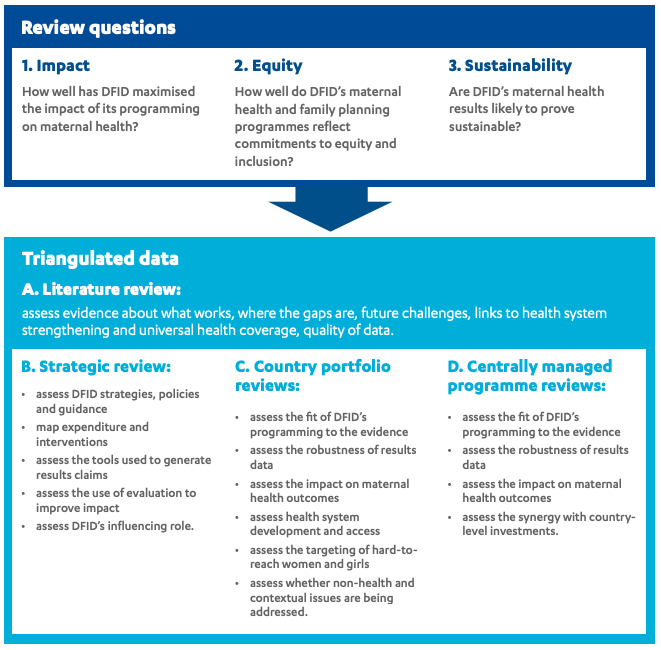

3. Review questions

This review is built around the criteria of impact, equity and sustainability.16 It will address the following questions and sub-questions:

Table 1: Our review questions

| Time | Agenda item |

|---|---|

| 13:30-13:35 | Introduction and welcome |

| 13:35-14:00 | ICAI formal update: - Minutes and actions from February 2025 Board - Business update |

| 14:00-14:20 | Corporate risk register |

| 14:20-14:40 | Internal audit 2025 |

| 14:40-14:55 | Break |

| 14:55-16:20 | Theory of change |

| 16:20-16:30 | AOB and close |

4. Methodology

Our methodology has been designed to allow an assessment of DFID’s contribution to improving maternal health outcomes against an understanding of what works. Our approach is therefore framed by a literature review, to determine areas of consensus and disagreement as well as gaps in the evidence base for maternal health. With reference to this evidence base, our strategic review will assess DFID policies, strategies and guidance, as well as the analytical tools that DFID uses to generate results data. We will look in detail at DFID’s work in two case study countries to explore whether the programming is contributing to improved maternal health outcomes and whether DFID is contributing to building sustainable national health systems. We will also undertake a series of reviews of DFID’s multi-country programmes and contributions to multilateral funds. We will focus on the impact of DFID’s programming from 2010-11 onwards, on what DFID has learned from this, and on how well it is positioned to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goal targets for 2030.

Component A – Literature Review: To help us address our review question on impact, we will undertake a review of the literature to identify areas of consensus about what works to improve maternal health outcomes, including with respect to health system strengthening and the more recent push towards universal health coverage. We will assess the literature to identify gaps in the evidence base, determine the quality of maternal health data and define the key challenges ahead. The relevant literature includes systematic reviews, evaluations, journal articles and reports.

Component B – Strategic Review: To assess DFID’s strategic approach towards maternal health, including its focus on equity and sustainability, we will review DFID strategies, policies, annual reports and guidance documents, and any relevant evaluations. We will also map DFID expenditure since 2010-11 on to a spectrum of potential interventions to improve maternal health outcomes. To test the validity of DFID’s results claims, we will conduct a light-touch comparative assessment of the tools available to measure impact in the area of maternal health, and a more detailed assessment of the analytical approach adopted by DFID (the Lives Saved Tool). This will include an assessment of modelled lives saved attributed to DFID alongside national and global data on maternal health outcomes for the period 2010-11 onwards.

We will also assess the influencing role played by DFID within key international forums and partnerships, such as the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health and the International Health Partnership (which has transformed into Universal Health Coverage 2030 (UHC2030) in line with the Sustainable Development Goals). We will complement this with key informant interviews with multilateral agencies and other bilateral donors. To explore the equity issues within maternal health, and to assess DFID’s strategic focus on ‘leaving no one behind’, we will undertake the key informant interviews and group discussions with experts in the field and with relevant civil society organisations.

Component C – Country Portfolio Reviews: Improving maternal health outcomes requires an integrated approach, which includes interventions in family planning and reproductive health, safe delivery, and antenatal and postnatal care. The broader health system and socio-cultural context, as well as non-health factors such as nutrition and access to water and sanitation, can affect the impact of these interventions. We therefore propose to select two case study countries, for which the entire DFID programme portfolio related to maternal health in those countries can be assessed. This includes considering interventions within the context of broader health system strengthening activities and local socio-cultural norms and practices that affect women’s and girls’ health and rights (such as early marriage, sexual initiation rites, female genital mutilation/cutting).

For each country, we will undertake short case study visits to review the range of relevant DFID-funded health programmes in operation since 2010-11, focusing on the extent to which they address equity and vulnerability, complement DFID’s multilateral programming and demonstrate sustainable impact. We will pay particular attention to programmatic links to broader health system strengthening within the context of the new international goal of universal health coverage, and to any DFID efforts to address issues related to the rights and empowerment of women and girls. We will review programme documentation to assess how evidence about what works and concerns about equity have informed programme design and implementation and the setting of goals and targets. We will interrogate the programme-level outcomes data that fed into DFID’s global results claims. We will undertake a limited number of field visits to discuss achievements and ongoing challenges with those involved in programme delivery and, where possible, to verify results claims.

Component D – Centrally Managed Programme Reviews: We have identified eight centrally managed programmes for desk review. These include multi-country programmes and UK contributions to multilateral programmes and funds. We will assess their impact, equity and sustainability using a combination of desk reviews of programme documents and interviews with the DFID teams responsible, any external delivery agent and key partners. We will also use the country case study visits to collect further evidence, where applicable, of the impact and sustainability of centrally managed programmes. This could be further supplemented by interviews with key informants from some additional DFID country offices if necessary.

5. Sampling approach

The methodology involves two sampling elements: the choice of case study countries and the selection of centrally managed programmes for desk review.

Case study countries

DFID has recent or ongoing bilateral programming in at least 24 countries focused on family planning or maternal and neonatal health. This represents aid expenditure of more than £1 billion over the financial period 2010-11 to 2015-16.

We have assessed key data for these 24 countries, including:

- The maternal mortality ratio in both 2010 and 2015, to assess progress made during the period covered by DFID’s results framework and as an indicator of the ongoing challenge in maternal health.

- The number of maternal lives saved attributed to DFID investments between 2011 and 2015, as measured using the Lives Saved Tool, to assess the significance of each country programme within DFID’s global results claims.

- The level of UK investment in programmes relevant to maternal health across the financial years 2010-11 to 2015-16.

In sampling the DFID programme portfolios in these countries to identify potential case studies, we have also considered the following criteria:

- The breadth of the DFID portfolio related to maternal health, including programmes covering family planning, the continuum of care for maternal health, health system strengthening, water, sanitation and hygiene, and nutrition.

- Complementary investments in efforts to improve the rights of women and girls (such as programmes addressing gender equity or violence against women).

- Country context, specifically the opportunity to explore issues of culture, vulnerability and equity.

We wish to study one portfolio with a strong focus on family planning, to contrast with another that more explicitly emphasises the maternal-neonatal continuum of care and health system strengthening. This will help us gain insights into the different ways that DFID has generated outcomes and achieved impact. The combination of country case studies is therefore critical to our sampling strategy.

Finally, we have also considered the distribution of country visits for all ICAI reviews over the last two years, to avoid over-concentration of reviews in the countries with the greatest UK aid expenditure.

Based on these criteria, we have identified Malawi and the Democratic Republic of Congo as the two preferred country case studies for this review. These countries have high levels of maternal mortality, to which DFID has responded with significant investment in relevant programming. The portfolios contrast in their approach – with family planning interventions given stronger emphasis in Malawi than in the Democratic Republic of Congo – but both make significant contributions to DFID estimates of maternal lives saved.

Centrally managed programmes

We have assessed DFID’s portfolio of 15 relevant centrally managed programmes in maternal health, reproductive health and family planning. We have identified a sample of eight that are most suited to illustrating the themes of interest to this review. These programmes account for more than 90% of such expenditure since 2010-11, through wide-ranging partnership and delivery mechanisms (multilateral fund, contractor, non-governmental organisation, academic institution).

An important feature of DFID’s work on maternal health is its contribution to and relationship with the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), a key multilateral agency in this area. UNFPA is a forum for global debate on issues related to women’s reproductive health and rights, as well as a supplier of family planning and reproductive health commodities. As such, it is an implementing partner for several DFID programmes relevant to this review. Other relevant multilateral agencies include the WHO, UNICEF and the World Bank. We propose to review in detail three multilateral programmes that DFID funds through UNFPA and the World Bank.

DFID’s work on maternal health also includes a number of large, centrally managed multi-country programmes which contribute towards DFID’s results claims in this area. We propose to review in detail five centrally managed programmes, which represent the majority of DFID’s expenditure via this route and have good availability of impact data (including through independent evaluation).

Table 2 below sets out the centrally managed multi-country programmes and multilateral contributions proposed for detailed review.

Table 2: Centrally managed multi-country and multilateral programmes for review

| Programme | Commitment | Timescale | Implementing partners | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn, Women and Children - Saving Lives through access to essential health commodities | £75m | 2014 - 2016 | UNFPA, WHO and UNICEF | Family planning and reproductive health commodities |

| Multi-country support for increased access to reproductive health, including family planning | £356.4m | 2013 - 2020 | UNFPA | Maternal, sexual and reproductive health commodities |

| Support to the Health Results Innovation Trust Fund | £114m | 2011 - 2022 | World Bank | Results-based financing to improve access to basic health services |

| Prevention of Maternal Deaths from Unwanted Pregnancy | £139m | 2011 - 2018 | Marie Stopes International | Family planning and reproductive health |

| Evidence for Action to Reduce Maternal and Neonatal Mortality | £20.6m | 2010 - 2016 | Options | Evidence to improve the quality of maternal and neonatal services |

| Making It Happen (Phase 2) | £15.9m | 2011 - 2016 | Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine | Training in obstetrics and neonatal care |

| Toward Ending Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Africa and Beyond | £26m | 2013 - 2018 | Options and UNFPA | Female genital mutilation/cutting |

| Reducing maternal mortality through supporting in-country initiatives to tackle unsafe abortion and improve access to services | £3m | 2013 - 2016 | International Planned Parenthood Federation | Safe abortion and reproductive health services |

6. Limitations of the methodology

Results data: In assessing the impact of DFID’s programming on maternal health, we will rely primarily on monitoring data generated by the programmes themselves, and on evaluations commissioned by DFID. We will not conduct our own impact assessments. We will manage the resulting risk of bias by triangulating in a number of ways. We will assess the quality of DFID’s outcome data by checking source data coherence on a sample basis and by comparing DFID data with national datasets and broader statistical trends. In case study countries, we will interview national government representatives and other development partners and will consult those involved in DFID programme delivery about how results were maximised and how likely they are to be sustained. This will enable us to reach some conclusions about the accuracy of DFID’s results data and the validity of results claims.

Review coverage: The review will examine how DFID’s maternal health programming is aligned with and complemented by investments in health system strengthening, which will include assessing how DFID health system programmes in case study countries contribute to maternal health outcomes. This will involve looking at whether and how DFID investments in health system strengthening support improvements in the maternal-neonatal continuum of care, but we will not specifically assess DFID’s impact in the area of neonatal health. Synergy with DFID’s efforts to improve the rights of women and girls will also be documented, but we will not specifically review the effectiveness of DFID’s programming in areas such as gender equity or violence against women and girls. ICAI undertook a learning review of DFID’s efforts to eliminate violence against women and girls (VAWG) in 2016, which may yield useful data. The VAWG review found that to achieve transformative impact, DFID would need to integrate VAWG work into other areas of programming which is clearly relevant to maternal health.17

7. Risk management

| Risk | Mitigation and management actions |

|---|---|

| Security concerns disrupt field work | Security risks are significant in some areas of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the country suffers frequent and sometimes serious disease outbreaks. In the event that the risks are considered too great to undertake planned travel, alternative methods will be used to gather the required data. If there is sufficient time, we will discuss with DFID the option of substituting another case study country from the shortlist in our sampling strategy. If the cancellation occurs too late to visit a different country, we will use alternative methods for collecting data on the Democratic Republic of Congo, such as interviews by telephone and video conference, document reviews and consultations with former DFID country office staff now in new posts. |

8. Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI lead commissioner Dr Alison Evans, with support from the ICAI secretariat. The review will be subject to quality assurance by the service provider consortium. Both the methodology and the final report will be peer reviewed by Professor Joy Lawn, director of the Centre for Maternal, Adolescent, Reproductive, and Child Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

9. Timing and deliverables

The review will be completed within ten months starting from November 2017, with the final report likely to be published in September 2018.

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Literature Review: November 2017 to January 2018 Approach paper: January 2018 |

| Data collection | Data collection: February to April 2018 Evidence pack: April 2018 Emerging findings presentation: May 2018 |

| Reporting | Final report: September 2018 |

Footnotes

- Choices for women: planned pregnancies, safe births and healthy newborns: The UK’s Framework for Results for reproductive, maternal and newborn health in the developing world, DFID, December 2010, link.

- Maternal mortality, World Health Organization (WHO), accessed November 2017, link.

- Adolescents: health risks and solutions, WHO, accessed November 2017, link.

- Preventing unsafe abortion: factsheet, WHO, accessed January 2018, link.

- The ‘maternal mortality ratio’ is maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. ‘Maternal death’ is defined by the WHO as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management but not from accidental or incidental causes”. See WHO website, link.

- Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015, WHO, 2015, p. xi, link.

- For example, the maternal mortality ratio fell to only 510 per 100,000 live births across Sub-Saharan Africa over the same period. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015, WHO, 2015, p. 3, link.

- Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world, United Nations, link.

- The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2016 – ‘Leaving no one behind’, link, and DFID policy paper ‘Leaving no one behind: Our promise’, January 2017, link.

- Single departmental plan: 2015 to 2020, DFID, updated 1 September 2016, link.

- Reducing maternal deaths: Evidence and action – A strategy for DFID, DFID, September 2004, link.

- Choices for women: planned pregnancies, safe births and healthy newborns: The UK’s Framework for Results for reproductive, maternal and newborn health in the developing world, DFID, December 2010, link.

- Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16, DFID, July 2016, link.

- Single Departmental Plan – Results Achieved by Sector in 2015-2017: Family Planning, DFID, link.

- This figure is based on modelling of preliminary estimates from programming in reproductive and maternal health, HIV, malaria, water, sanitation and hygiene, humanitarian assistance, and general and sector budget support to the end of the 2014-15 financial year. Approximately 75% of these lives saved resulted from family planning interventions. Annual Report and Accounts 2015-16, DFID, July 2016, link.

- Based on the OECD DAC evaluation criteria. See OECD DAC 1991, Principles for evaluation of development assistance, link.

- DFID’s efforts to eliminate violence against women and girls, ICAI, May 2016, link, ICAI follow-up of: DFID’s efforts to eliminate violence against women and girls, ICAI, June 2017, link.