DFID’s Empowerment and Accountability Programming in Ghana and Malawi

Executive Summary

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review.

DFID has made a strong commitment to promoting development through the empowerment of citizens. It has pledged to support 40 million people to have more control over their own development and to hold their governments to account. Currently, it has empowerment and accountability programmes in twelve African and five Asian countries contributing to this result. This review assesses one element of this portfolio, namely programmes that aim to strengthen citizen engagement with government. Looking at two contrasting African countries, Ghana and Malawi, we examine two grant-making funds for civil society organisations (CSOs) and a project that supports community monitoring of local services. With a combined budget of £41 million, these programmes support a wide range of activities, from helping local communities to become more engaged in the running of local schools to civil society campaigns on the management of the oil and gas sector in Ghana.

Overall

Assessment: Green-Amber

DFID’s approach to empowerment and accountability is still evolving but it is already generating some useful results. The social accountability programmes we examined were promoting constructive community engagement with government and thereby helping to address obstacles to the delivery of public services and development programmes. Support for CSO advocacy, however, produced more limited results and DFID’s more ambitious goals to promote accountability through social and political change appeared to be unrealistic. We are concerned that, when designing its programmes, DFID tends to default to CSO grant-making, which is not always the most strategic option. A clearer and more realistic set of objectives and a stronger rationale for programme design would help to maximise results.

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

As this is a relatively new focus area for DFID, it is still clarifying its objectives and is yet to produce detailed guidance on programme design. As a result, we found a tendency for country offices to opt for CSO grant-making as a familiar model for social accountability programmes. This produces a scattered portfolio of small CSO activities that are difficult to scale up or link together in a strategic way. The programmes we reviewed are not joined up with DFID’s wider sector programmes (such as education and health), even where they share similar goals.

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

The two grant-making programmes have sound procedures but are struggling with the high number of grants (STAR-Ghana has awarded 187). Their capacity building support and fiduciary risk management processes are, as a result, not sufficiently tailored to the needs of individual grantees. While the programmes pay close attention to cost control, competitive grant-making may not be the most cost-effective way of funding empowerment activities at the local level.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

We found that the programmes were achieving some promising results by empowering communities to engage constructively with government to resolve problems with the delivery of public services and development programmes. This type of social accountability approach works by benefiting both governments and communities. By contrast, support for CSO advocacy at the national level has had more limited impact and seems unlikely to generate significant improvements in government accountability. The programmes are yet to develop a strategy for ensuring the sustainability of their results.

Learning

Assessment: Green-Amber

The programmes are investing substantial effort in measuring results in a technically challenging area, using a range of quantitative and qualitative techniques. Though competently done, monitoring is used primarily to demonstrate efficient delivery, rather than to support learning. We are concerned that the programmes are not flexible enough to support their partners with innovation, rapid learning and the scaling up of successful results. At the central level, DFID has been assembling and disseminating an evidence base but is not well positioned to support shared learning across country offices.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Promoting constructive community engagement with government around the delivery of public services and development programmes should be the principal focus of DFID’s social accountability programmes and a shared goal with its sector programmes. When scaling up successful social accountability initiatives, direct grants to national CSOs to work with local communities are likely to be more effective than competitive grant-making.

Recommendation 2: DFID’s support for CSO advocacy and influencing at the national level should be more targeted, with smaller portfolios, longer partnerships and more tailored capacity building support.

Recommendation 3: Future social accountability programmes should be designed with the flexibility to test different approaches and scale up successful initiatives. DFID’s central policy team should guide this process of structured learning and ensure the continuous sharing of lessons among country offices and managing contractors and with relevant sector programmes.

1 Introduction

DFID has made a major new commitment to support empowerment and accountability

1.1 In June 2010, the then International Development Secretary, the Rt Hon Andrew Mitchell MP, announced a ‘fundamental change’ in the UK approach to development assistance. The UK would rebalance its aid programme from focussing on the state as the primary agent of development to investing in people. ‘Our approach will move from doing development to people to doing development with people – and to people doing development for themselves.’1 The current Secretary of State, the Rt Hon Justine Greening MP, has linked this to the ‘golden thread’ of open and democratic institutions, identified by the Prime Minister2 as essential to the development process.3

1.2 DFID is putting this new policy direction into practice by building up an area of its portfolio, known as ’empowerment and accountability’. It encompasses promoting human rights, reducing social inequality and giving poor people better access to resources and markets. It also includes programming that is designed to give citizens more influence over government, whether through formal political processes or through direct interaction between communities and service providers.4

1.3 These are not new objectives for DFID, which has, for many years, funded activities that support empowerment and accountability – usually on a small scale. Since the last election, however, these objectives are being pursued more intensively. In its Business Plan, DFID has pledged to ‘support 40 million people to have choice and control over their own development and to hold decision-makers to account’ by 2015.5 So far, DFID states that it has reached 33.4 million people through programmes in twelve African and four Asian countries (plus some international and regional programmes).6 We note that this is a ‘headcount’ indicator, showing the scale of the programming rather than its impact.

Empowerment and accountability in development thinking

1.4 Empowerment and accountability are complex ideas which have generated much policy analysis. Their translation into practical programmes capable of delivering real benefits to citizens is challenging. In this section, we briefly introduce the concepts and how they are used in development programmes. Figure 2 on page 5 sets out some illustrative examples of DFID’s programming in this area.

1.5 DFID defines empowerment as ‘enabling people to exercise more control over their own development and supporting them to have the power to make and act on their own choices’.7 Empowerment is both a way of promoting development and a development goal in its own right.8 It includes building individual capabilities, for example by ensuring that minority groups have access to education. It includes addressing barriers to fair participation in communities, the market and the political system. It can also mean enhancing the ability of citizens to act collectively through civil society and the democratic process.

1.6 Accountability refers to the ability of citizens to influence the behaviour of their representatives, whether elected politicians or appointed officials. Accountability is enhanced through rules governing how representatives should behave and through processes that monitor their compliance, require them to justify their actions and provide a means of redress if they fail to act as they should.

1.7 Development agencies often turn to empowerment and accountability programmes, where governments are seen as unwilling to reform. If politicians are not motivated to improve government performance, empowering citizens to articulate their demands may help to shift the political incentives in favour of reform. Institutional reforms, such as increased transparency in government, a more active parliament or a free media, are thought to help with shifting the balance of power in favour of citizens.

1.8 The potential for this kind of ‘demand side’ programming to shift political incentives in favour of improved government performance is, however, contested in the development literature. Recent DFID-funded research has concluded that a more vocal civil society is, on its own, a relatively weak source of performance pressure for government, in the absence of wider political change.9

1.9 In an influential 2004 report, the World Bank distinguishes between the ‘long route’ to accountability via the democratic process and the ‘short route’ of direct citizen engagement with government (sometimes called ‘social accountability’).10 The World Bank concludes that creating stronger democratic accountability through the political system is necessarily a long-term process, which may not be susceptible to influence through donor programming. There may, however, be short-term development returns from promoting community engagement with the delivery of public services and development programmes, even in the absence of strong democratic institutions. We find this distinction to be a useful one in interpreting the results we observed in this review.

The scope and purpose of our review

1.10 For this review, we examine three DFID empowerment and accountability programmes in two contrasting African countries, Ghana and Malawi (see Figure 1 on page 4 for the country contexts). Two of the programmes provide grants, primarily to civil society organisations (CSOs), for a wide range of social accountability activities, plus some support for parliamentary committees and media organisations. The third is a project that supports citizen monitoring of public services in Malawi. The programmes are:

- Strengthening Transparency, Accountability and Responsiveness in Ghana (STAR-Ghana), 2010-15: this is a £27.2 million programme, co-funded by DFID, Denmark, the European Union and the United States.11 It has a budget of £21.5 million for grants, of which £15.7 million has been awarded so far, with 187 grants averaging £75,000;12

- Tilitonse, 2011-15: this is a £14 million programme in Malawi, co-funded by DFID, Ireland and Norway, of which £11.9 million is available for grants.13 It has, so far, awarded £4.4 million, with grants averaging £127,000; and

- Kalondolondo, 2011-14: this is a direct grant of £2.5 million to a group of Malawian CSOs to run a programme promoting citizen monitoring of public services through the use of community scorecards.

1.11 Our review assesses whether these programmes are designed and delivered effectively and whether they are likely to achieve meaningful results for their intended beneficiaries. We recognise that this is an area in which DFID is still developing its overall approach. Our review is intended to contribute to this learning. The programmes we reviewed were part way through their implementation, which makes it premature to draw conclusions on their final impact. We focussed, therefore, on identifying patterns in the emerging results, in order to assess whether the objectives are realistic and whether the design and delivery options are best suited for achieving those goals.

Ghana has a more open political environment. It is one of a limited number of African countries to have achieved the peaceful transfer of power through successive elections. It has a vibrant press and a strong civil society, including an array of CSO networks and platforms and a strong community think tank. Despite Ghana’s strong development performance, the state continues to demonstrate significant institutional weaknesses and there are concerns that oil and gas production may lead to a deterioration of the quality of governance, as has occurred in other African states.15

Malawi presents a more difficult political environment. Until recently, CSOs were subject to a range of restrictions by the state. In 2011, concern over a deteriorating human rights record, among other factors, led DFID and other donors to discontinue budget support to the government. While the situation has improved under the current government, civil society in Malawi is fragmented, with little tradition of influencing government.

Both countries have, in the past, launched decentralisation reforms that have subsequently stalled. As a result, there are very limited resources and decision-making powers at the local government level.

Our methodology

1.12 Our methodology for this review consisted of the following elements:

- a review of academic and donor literature on empowerment and accountability, including DFID-funded research programmes, such as the Africa Power and Politics Programme (APPP) and the Development Research Centre on Citizenship, Participation and Accountability;

- a review of DFID’s policy statements and guidance material;

- interviews with DFID staff in Ghana, Malawi and the UK (principally, Africa Regional Department and the Politics, State and Society Team); and

- detailed reviews in Ghana and Malawi of the three programmes, including programme documentation, stakeholder and beneficiary interviews and visits to a range of project sites.

1.13 From the two grant-making programmes, we chose a sample of 22 projects for detailed review, out of 97 that had been under implementation for at least 6 months. Although the projects were mostly for periods of only 6-12 months, in many cases the CSOs in question had also received DFID funding in the past for the same or similar activities, giving us an opportunity to assess impact over a longer time period. In particular, many of the STAR-Ghana grantees had received past funding under two predecessor programmes, the Rights Accountability and Voice Initiative (RAVI) and the Ghana Research and Advocacy Programme (G-RAP). The sample was chosen to cover a representative range of issues and activities. In each case, we interviewed the implementing partner and, where possible, the agency that the project sought to influence. We held focus groups and individual interviews with the intended beneficiaries and, in some cases, observed events, such as community meetings. We compared the feedback from stakeholders and intended beneficiaries to project reports.

1.14 For our sample projects, we assessed the types of result that had been achieved, using a qualitative scale of our own design (see Annex A1 and accompanying methodological note). This methodology was designed to enable us to identify patterns in the results to date, rather than draw conclusions on the overall impact of these programmes. This, in turn, enabled us to assess whether the design and delivery of the programmes were appropriate.

1. Promoting community engagement in education

The Regional Advisory Information and Network Systems (RAINS) is a Ghanaian CSO working to improve community management of the education system in the economically deprived Volta region of northern Ghana. According to RAINS, school governance arrangements, envisaged under the 2009 Education Act, are barely functional. RAINS, therefore, is working to support the community supervision of schools through school management committees (SMCs) and parent teacher associations (PTAs). It has also established a multi-stakeholder platform at the district level that brings together local authorities, the media and other stakeholders to address issues of concern.

2. Empowering women

Tilitonse supports Oxfam Malawi and a number of local partners to strengthen women’s engagement with local government in 320 villages across 4 districts of Southern Malawi. The project supports community sensitisation and mobilisation through an approach that was originally developed for empowering people living with HIV-AIDS. It brings together 20-25 representatives of the target group and, with external facilitation, helps them to analyse their needs, understand their rights and develop strategies to engage with local duty bearers.

3. Responding to the impact of oil and gas production

Since commercial oil production began in Western Ghana in 2010, local communities in the affected coastal region have reported a range of negative impacts, including environmental damage, deterioration of infrastructure, high inflation and the near collapse of the local fishing industry. With the oil and gas industry generating little local employment, there have been few compensatory benefits. The oil companies provide some support to local communities in the form of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) projects. In the absence of participatory processes to establish community needs, however, these projects appear arbitrary and many of the community leaders we met described them as a source of conflict. According to one, ‘CSR is a system of divide and rule. Oil companies pick a few CSOs, give them Christmas presents, then go on to do whatever they want’.

STAR-Ghana is responding with a number of projects designed to improve community interaction with the oil and gas sector and the responsible government institutions. The Community Land and Development Foundation is developing a multi-stakeholder platform involving government, the private sector and communities, to improve co-ordination of CSR projects. At the time of our visit, only one oil company had publicly committed to the process. The Platform for Coastal Communities is an association of local communities that intends to track how government uses oil revenue to support the Western Region, in order to assess whether the benefits are being shared fairly. STAR-Ghana is also supporting the Ghana National Canoe Fishermen Council to establish a system to monitor whether oil companies comply with their environmental commitments.

4. Using social media to prevent election conflict

The social media organisation, Penplusbytes, received a grant from STAR-Ghana to establish a ‘crowd-sourced’ website that monitors comment on social media (e.g. Twitter and Facebook) regarding problems occurring on election day. Where issues emerged (e.g. a lack of materials at a particular polling station, leading to long queues), Penplusbytes passed the information on to the National Election Task Force for action. Through rapid citizen feedback, gathered through social media, problems that might have triggered security incidents were quickly resolved, contributing to a peaceful election.

5. Controlling corruption in fertiliser subsidies

The Kalondolondo programme in Malawi uses community scorecards to collect feedback on the delivery of development projects and public services, such as building schools, HIV-AIDS services and the use of local development funds. The process generates evidence on local problems and issues, which are then raised with the responsible authorities through community meetings. Kalondolondo also shares its findings with national authorities, often inviting local community members to testify to their accuracy.

2 Findings

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.1 In this section, we look at DFID’s progress in developing its overall approach to empowerment and accountability programming, including its emerging theory of change, its efforts to construct an evidence base and the emerging guidance it has produced for its country offices. We then review the strategies and designs of the three programmes in our sample.

DFID’s overall approach to empowerment and accountability

DFID’s theory of change and programming guidance is under development

2.2 DFID’s approach to empowerment and accountability begins from a broad policy commitment (see paragraph 1.1 on page 2), rather than a strong evidence base of past impact. DFID currently offers its country offices only provisional or ’emerging’ guidance, while encouraging country offices to come up with their own approaches and programme designs, based on their particular goals and the country context. Over time, as an evidence base emerges, DFID plans to develop more detailed guidance.

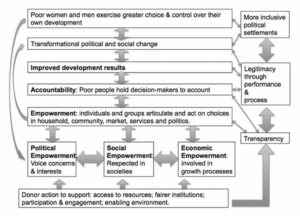

2.3 In its emerging guidance, DFID sets out a preliminary theory of change (see the DFID flowchart, Figure 3 on page 7). It suggests that donor programmes that promote citizen engagement with government can lead to greater political empowerment, as citizens become better able to voice their concerns and interests. This, in turn, can lead to greater government accountability, improved development results and transformational political and social change.

2.4 The model acknowledges that the causal links also go in the other direction. Political and social change may, in turn, generate greater empowerment and accountability. Empowerment sits at both ends of this change process, in recognition that it is both an entry point for programming and an outcome of wider development processes.

2.5 DFID has also developed a more elaborate theory of change, which is being tested as part of a forthcoming macro-evaluation of the empowerment and accountability portfolio (see paragraph 2.115 on page 23). This explores, in more detail, the change mechanisms that can be supported through empowerment and accountability programming. It posits that social accountability initiatives, such as community monitoring of public services, can lead to stronger demand for accountability by poor people and incentives for service providers to be more responsive and inclusive. It also posits that supporting civil society organisations (CSOs) to voice the interests of the poor in the political process can lead to pro-poor policy outcomes. These change processes closely match the objectives of the programmes we reviewed. It also describes other change mechanisms, including the economic empowerment of citizens, increased government transparency and the reform of political institutions.

2.6 An assumption behind DFID’s empowerment and accountability programming is that democratic accountability can emerge incrementally, through the gradual strengthening of citizen voice through civil society. This assumption cannot, at this point, be verified through evidence from developing countries (see paragraphs 2.9 to 2.11 on page 7). Nor is it necessarily supported by accounts of the historical development of longer established democracies. One recent historical work, for example, suggests that major institutional change is often linked to ‘critical junctures’; that is, major events or sets of circumstances that disrupt the existing economic and political balance in society.16

2.7 At this stage, DFID leaves it to country offices to identify the change mechanisms that they would like to support, based on their own contextual analysis. The emerging guidance on DFID’s internal website provides working definitions of empowerment and accountability and suggests various ‘entry points’ (for example, parliament, the media and civil society) for programming. It encourages country offices to engage in political economy analysis to gain a better understanding of existing power relationships. It advises them to support ‘coalitions for change’ between citizens and elites around specific issues and to invest in the underlying conditions for empowerment and accountability, for example, by encouraging greater transparency in government. It does not, at this stage, offer a menu of programme options from which country offices can choose the elements that best fit their objectives and country conditions.

DFID, undated.

2.8 We accept that, at this early point in a new and complex area of programming, DFID’s approach should not be too prescriptive. It should allow country offices the space for experimentation and learning. In practice, however, in the absence of clearer guidance, country teams seem to be falling back on the social accountability programme designs with which they are most familiar, namely, CSO grant-making funds. This suggests that DFID needs to move more quickly to develop practical guidance on programme design options.

The evidence behind DFID’s approach remains limited

2.9 In 2011, DFID commissioned a review of evidence on the impact of empowerment and accountability programming. Based on theoretical literature and evaluations of past programmes, the review concluded that the evidence was ‘fragmentary’. While it revealed some good examples of social accountability initiatives leading to local improvements in development outcomes, the results tended to be context-specific and difficult to replicate. Diverse and often inconsistent definitions of empowerment and accountability made results hard to measure and compare. Evidence that empowerment and accountability programming leads to wider changes in political dynamics was ‘particularly hard to find’.17

2.10 DFID-funded research programmes have produced similarly mixed results. In a review of over 100 case studies in 20 countries,18 the Development Research Centre on Citizenship, Participation and Accountability found that 75% had produced useful results, although not necessarily the results expected by donors. It noted that donor expectations are often unrealistic and that there is a need to measure a ‘middle ground’ of changes to attitudes and behaviours that are the more direct outcome of such programmes. The research was, nonetheless, optimistic that a critical mass of empowerment and accountability initiatives could lead to an accumulation of benefits over time, including a growing sense of citizenship, greater knowledge of rights and entitlements and a ‘thickening’ of civil society alliances and networks. This gradually leads to more pressure on states to improve their performance, although the process can be ‘long and arduous’.

2.11 The multi-country APPP has produced findings that, in our view, challenge some of the assumptions behind DFID’s past empowerment and accountability programming. APPP is sceptical that ‘demand-side’ programming can generate genuine performance incentives for governments, in the absence of changes at the political level. The Development Research Centre on Citizenship, Participation and Accountability similarly emphasises the importance of interventions that work on both sides of citizen-state relations. DFID informs us that it is working to incorporate these findings into its approach.

Programme design

The two grant-making instruments aim to increase civil society influence over government decision-making

2.12 The two grant-making programmes we examined – STAR-Ghana and Tilitonse in Malawi – share similar objectives. Both aim to increase the accountability and responsiveness of government as their ultimate impact. The intended outcomes are improved voice and influence for citizens and CSOs:

- for STAR-Ghana: ‘increased CSO and Parliamentary influence in the governance of public goods and service delivery’; and

- for Tilitonse: ‘citizen voice in achieving more inclusive, accountable and responsive governance strengthened’.

2.13 Both programmes aim to increase the influence of CSOs, so that they can become more effective intermediaries between citizens and the state. They support CSOs to increase citizens’ awareness of their rights, to generate evidence on government performance and to use that information to influence government decision-making. Both see the media and parliamentary committees as important channels through which CSOs can influence government.

2.14 Both programmes pursue these goals primarily by providing grants to CSOs for particular projects. They also provide their grantees with a range of non-financial support, including training on organisational development and on specialised topics, such as advocacy.

2.15 The two programmes began from different premises. In Ghana, DFID and other donors had been funding CSOs for a number of years, including core funding for national research and advocacy organisations and project funding for initiatives with local communities. While Ghanaian civil society was highly vocal, DFID was concerned that it was not engaging with government effectively. The STAR-Ghana design documents note that, while there had been some successes with influencing government policy, this had not translated into sustained improvements in service delivery. STAR-Ghana, therefore, set out to promote more productive engagement of civil society with government through influencing activities across the government business cycle (planning and policy-making, budgeting, implementation and monitoring).

2.16 The Tilitonse programme in Malawi was designed as a joint donor fund to support democratic governance, at a time when the scope for civil society engagement in the democratic process appeared to be shrinking. Before it began operations, however, a change of president led to a more open political environment, enabling Tilitonse to focus on supporting CSOs to interact constructively with government.

The programmes are yet to develop convincing strategies for increasing CSO influence over government

2.17 The key strategic challenge facing these programmes is how to increase civil society influence over government decision-making. They have used a number of creative approaches but still lack a fully convincing strategy.

2.18 First, the programmes group their grants around particular themes or sectors, such as health, education, elections, local governance and the extractive industries (although these are not strategically linked to DFID’s sector programming in the same areas). By supporting a portfolio of projects working in different ways towards common goals, the programmes aim for a critical mass of pressure for improved government performance.19

2.19 Second, the programmes seek to link activities at the local and national levels. Their portfolios include grants to local CSOs to help communities to engage more effectively with local government and service providers. In the process, these projects generate evidence on government performance and collect feedback from communities on how it could be improved. The two programmes then encourage the CSOs to use the evidence for policy advocacy at the national level.

2.20 Third, the programmes encourage their grantees to increase their influence by forming partnerships. In Ghana, there are many existing civil society networks and platforms, some of which are supported by STAR-Ghana. In fact, we were concerned that STAR-Ghana may be creating yet more dialogue structures, when there already appear to be many. In Malawi, the Tilitonse design documents acknowledge that civil society is more fragmented. Grantees are, therefore, encouraged to forge alliances with more powerful groups, such as business interests or professional associations. In practice, we did not find any successful examples of this.

2.21 Fourth, the programmes encourage CSOs to work with parliament and the media. They provide some financial support to media organisations and parliamentary committees to facilitate these alliances. Although this support is too recent to evaluate its results, it appears to be a long-term strategy. The parliamentary committees we visited had few resources for travelling and interacting with the public and, therefore, welcomed CSO support for collecting community input. On the other hand, they also acknowledged having very little influence over government policy. We were also informed that CSO lobbying of parliamentary committees rarely influences the way their members vote in parliament.

2.22 Finally, both programmes provide their grantees with training on advocacy techniques. They are taught to identify their advocacy goals and formulate a strategy for achieving them. Common advocacy techniques include organising public meetings between government officials and stakeholders, issuing press releases, making radio programmes and lobbying parliamentary committees.

2.23 While a few of the CSOs we visited had well-defined advocacy goals and approaches, most were new to the advocacy field and had only a tentative idea of what they were trying to achieve and how. Their attempts to provide feedback to government on its performance were only occasionally successful. Government agencies in both countries typically face significant financial and human resource constraints, as well as an overwhelming reform agenda. Their willingness and ability to take on board new evidence or policy ideas is limited. In this environment, unstructured or ad hoc feedback from communities is unlikely to have significant influence.

2.24 Successful advocacy campaigns are, by nature, complex to plan and execute. They involve co-ordinated efforts across multiple actors over a sustained period and are informed by sound political analysis. At present, most of the CSO grantees in both programmes have not yet achieved this capacity. We were not always convinced that project-based grant funding was the right instrument for developing this capacity. In many of the projects we reviewed, it was difficult to establish how major influencing goals could be achieved within a 12-18 month project cycle.

2.25 We were also concerned that the programmes, in some cases, appeared to be encouraging CSOs with a service delivery background to move into advocacy. In some cases, it appeared that CSOs had included advocacy activities in service delivery projects in order to access the funding. For example:

- Youth Alive helps street children in three districts of northern Ghana to access health and education services;

- the Integrated Action Development Initiative supports English language clubs in 26 schools in western Ghana; and

- the Sinapi Aba Trust in Ghana provides management training to private schools.

2.26 In these cases, the grantees were focussed on service delivery and were struggling to identify policy-relevant information that could be used for advocacy.

2.27 Overall, we found that both STAR-Ghana and Tilitonse lacked a realistic assessment of the current strengths and limitations of CSOs and how they might feasibly develop over the life of the programme. In the absence of such analysis, we found that the expectations of CSO grantees and the extent to which they would be able to influence government were often unrealistic.

Empowerment and accountability programmes are not linked to national policy-making processes or DFID’s own sector programmes

2.28 Given the challenges involved in mounting effective advocacy campaigns, we would have expected to see the programmes making more use of established channels for civil society to input into government policy-making. In both countries, donors have, for many years, encouraged the governments to open up their policy-making processes to civil society input and to introduce joint monitoring through annual sector reviews. In a few instances, such as within the education sector in Ghana and the water and sanitation sector in Malawi, these programmes are helping CSOs to contribute more effectively to such processes. In general, however, the programmes are not targeting existing channels for CSO influence.

2.29 The programmes are also not well linked to DFID’s own sector programmes. DFID’s education programmes in Ghana, for example, contain a range of social accountability elements, such as strengthening community management of schools. Several STAR-Ghana grantees are pursuing similar goals. Although there is some consultation between the programmes, they are not designed to be mutually supporting. As strengthening school management committees and parent teacher associations is part of the government’s national education strategy, it is not clear what STAR-Ghana is adding by pursuing the same goals in a few districts.

2.30 In this respect, DFID needs to be clearer about the different strategies required for ‘long-route’ and ‘short-route’ accountability; that is, promoting accountability through the democratic process or through direct engagement of citizens with service providers (see paragraph 1.9 on page 3). In the latter case, the goal is to promote regular, constructive engagement between communities and government. This is most likely to happen where DFID works with both civil society and government to promote behaviour changes on both sides and to create more opportunities for institutionalised interaction.

The criteria for choosing and designing delivery instruments remain unclear

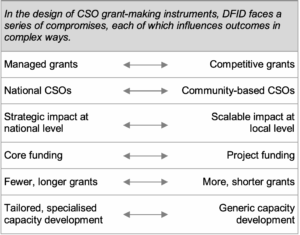

2.31 At present, DFID lacks clear criteria for choosing among the different delivery options for its social accountability programmes. While DFID’s guidance lists a wide range of possible entry points and approaches for empowerment and accountability programming, it appears that the majority of country offices are defaulting to civil society grant-making instruments as a programme model. We encountered significant reservation among DFID advisers and implementing partners on whether competitive grant-making to CSOs is the best approach.

2.32 Competitive grant-making is useful for identifying and providing seed funding for the most innovative proposals among a wide circle of potential applicants. It also has some inherent disadvantages. As our past reviews of the Conflict Pool20 and the Arab Partnership Participation Fund21 have found, it tends to result in a scattered portfolio of small-scale activities that are difficult to scale up or link into a strategic whole. While strong on innovation, it is relatively weak on focus and intensity of engagement.

2.33 The larger the instrument and the more grants it provides, the more difficult it is to maintain a clear strategic approach. We found that both STAR-Ghana and Tilitonse have large (relative to their management capacity) and fairly fragmented portfolios. The high volume of grant-making creates a substantial management burden (see the Delivery section on page 12), allowing the programme management teams limited time to work with individual grantees on their strategies.

2.34 We were unable to find any evidence that the choice of a competitive grant-making instrument and the decision on the volume of funding was based on an explicit consideration of the compromises involved. This is an area where DFID needs to develop more explicit guidance.

2.35 Furthermore, there are important choices to be made in the design and delivery of grant-making instruments, which also involve compromises between competing objectives (we have summarised some of the choices in Figure 4). A key choice is between competitive grant-making (where funds are awarded on the basis of the most promising applications) and managed grant-making (where the programmes make strategic choices as to which partners to support and help to shape their activities). There are also important choices to be made on which types of CSOs to support, between national and local projects, in the number and size of grants and in the types of capacity building support that are offered.

2.36 Many of these choices are made by the contractor managing the programme, in consultation with DFID, either through the bidding process or during the inception phase. The implications of each choice are complex and may emerge only after several years of implementation.

2.37 We found that each programme was wrestling, independently, with a similar set of questions, without the benefit of experience from other programmes. One report of a learning event among some of DFID’s managing contractors concluded: ‘There was little evidence that these various country designs were based on any explicit comparative advantage of what the alternative designs could have been… In fact many of the programme staff in the room were surprised at how different their programme was from those of the others without really knowing why this was the case.’22 DFID needs to begin developing guidance on the merits of different delivery options and design parameters, so that country offices can understand the compromises involved.

Kalondolondo has more limited objectives, allowing for a more straightforward design

2.38 The goal of the Kalondolondo programme in Malawi is to improve service delivery by promoting constructive engagement between communities and service providers. It is an example of what the World Bank calls the ‘short route’ to accountability through direct citizen-government interaction, with no explicit goals on transformative political change (see paragraph 1.9 on page 3). DFID funds a group of Malawian CSOs to conduct community monitoring of development initiatives (e.g. HIV-AIDS programmes, school construction projects and the distribution of subsidised farm inputs) by means of a ‘scorecard’ (see Figure 2 on page 5).

2.39 The programme has a number of strong design features. It teaches communities that government services and development projects are an entitlement, rather than a gift from influential individuals. It generates knowledge of government programmes and processes. It helps communities to identify and resolve barriers in the delivery of particular services; for example, where local chiefs are acting in their own interests, rather than in those of the community. It encourages them to engage in self-help, including contributing their own labour and materials to develop local infrastructure.

2.40 The scorecard process also generates evidence on how well government programmes are delivered. Kalondolondo collects this data and provides it to the national authorities, often inviting local community members to present their experiences. Over several years, Kalondolondo has built up credibility with national service providers and is often invited to share its findings.

2.41 This influencing strategy is effective, mainly for resolving problems in the delivery of existing government programmes, in cases where national authorities share an interest in improving services. It is not set up to campaign for new programmes or entitlements. These more modest objectives enable it to make effective use of existing capabilities within civil society and local communities. By building on what is already there, it is more likely to deliver practical benefits in the short run. Had we been scoring each of the programmes individually, Kalondolondo would score green for Objectives, owing to its well-conceived design.

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.42 In this section, we look at how effectively the three programmes are delivered. We consider the quality of the grant-making process, the adequacy of financial management and the attention given to securing value for money.

Grant-making processes

Selection criteria and grant-making methods are sound but not sufficiently flexible

2.43 In STAR-Ghana and Tilitonse, we found that grant-making processes were competently managed. In both cases, however, some quality in delivery has been sacrificed due to the high volume of grants. This led to processes that are somewhat standardised and inflexible. Both programmes provide a combination of competitive grants (where applicants bid for funds on the strength of their project proposals) and managed grants (funding provided directly to selected partners). The competitive funding rounds may be open or limited to specific themes or areas. STAR-Ghana provides managed grants for capacity development and for ‘strategic opportunities’, for example, to scale up a successful initiative. Tilitonse plans to provide managed grants, although this component of the programme is still under development.

2.44 Both programmes have clear, transparent and appropriate selection criteria for their grantees. These include minimum organisational requirements and a track record of successful delivery. We saw some evidence that STAR-Ghana’s practice of holding thematic or sector-specific funding rounds to access funding was pushing CSOs into unfamiliar areas. If, for example, the programme issues a request for proposals for a health project, CSOs in need of funding may attempt to create a health project, without prior expertise in that area. Improved sequencing of the funding rounds would assist in resolving this problem.

2.45 Applicants are assessed on the quality of their proposals, their ability to formulate clear reasons for change, their anticipated results and the strategic fit in terms of the programme. Innovatively, STAR-Ghana seeks to ensure a spread of interventions across the government-directed business cycle and at different levels of government, to ensure various approaches to influence government.

2.46 In its first funding round, STAR-Ghana required its grantees to enter into new partnerships and alliances, as a condition to access funding. This was partially successful. While we recognise the value in promoting linkages between local and national CSOs, forcing alliances can lead to ineffectual, short-lived partnerships – a lesson that STAR-Ghana has now taken into consideration.

2.47 We are also concerned that, in trying to broker partnerships, the programmes may be displacing the work of existing CSO networks and alliances. Both programmes fund a number of CSO umbrella organisations (i.e. membership organisations of CSOs working in a particular area). We observed that providing project funding to umbrella organisations can result in building up their own delivery capacity, thus placing them in competition with their own members. In initial funding rounds, STAR-Ghana offered short-period grants of 6-12 months. The grantees informed us that this time frame was too limited for substantial results. In subsequent funding rounds, STAR-Ghana has offered grants of up to three years, which appears to be a more effective use of its resources.

2.48 While STAR-Ghana’s and Tilitonse’s grant-making procedures are generally well conceived, the quality of implementation is affected by the large number of grants. The programme management teams are constrained in their ability to work with grantees individually, in order to develop their proposals or address implementation challenges. As a result, the focus of the relationship is on compliance with programme requirements, rather than on strategy and learning.

Delivery capacity is being developed but wider organisational change is less apparent

2.49 Both programmes provide capacity development support to their grantees, which is key to achieving results that will outlast the project cycle. Grantees carry out an organisational self-assessment, against set criteria, to diagnose their own capacity needs. They then agree to a capacity building plan, to be implemented over the life of the grant. The STAR-Ghana grantees report annually on their capacity building progress and their reports are reviewed by the programme’s quality assurance team.

2.50 Both programmes are searching for the most effective way to support capacity development. Capacity building initially took the form of a standardised package of support, mainly aimed to help grantees to manage properly grant funds and reporting requirements. STAR-Ghana, for example, offered grantees a training package on monitoring and evaluation, financial management, gender and social exclusion and policy advocacy. Programme reviews point to the need for a more holistic approach, with specialised support tailored to the needs of individual grantees. STAR-Ghana now has a greater focus on mentoring by specialist private sector or other CSO trainers.

2.51 During our visits to grantees, there was evidence of capacity development, particularly around financial management, value for money analysis and monitoring and evaluation. It was more difficult to attest to improved policy advocacy, although it may be too early to judge.

2.52 Tilitonse has experienced difficulties with making its capacity building programme operational, owing to poor performance by a local non-governmental organisation (NGO) brought into the managing consortium to run the capacity building component. Following a review of the programme’s capacity building approach, commissioned by the governing board, this arrangement was terminated and a full-time capacity building manager within the Secretariat has been engaged. Grantees will, in future, receive support from individual mentors.

2.53 It is helpful to note that both programmes use external contractors to provide capacity development support to complement their own capacity and achieve better value. They have learned, however, that the support delivered by contractors tends to be insufficiently tailored to the needs of individual grantees and, therefore, not as effective as it could be. While outside providers can play a useful role, the programme management teams should remain closely involved in the design and delivery of capacity development activities to ensure they meet the needs of each grantee. Both programme management teams have recently requested permission from DFID to increase their in-house capacity building expertise.

Governance and financial management

Governance arrangements provide for stakeholder representation but at the expense of clear lines of accountability

2.54 Both programmes have a governing board, consisting of donors and a number of eminent nationals. The governing board oversees the programme management team, sets the strategic approach and approves the individual grants, based on the recommendation of the programme management team. By including various prominent figures from civil society, the boards provide some indirect representation for the intended beneficiaries.

2.55 The two governing boards have taken some time to define their role and become effective. In the case of STAR-Ghana, the board was quite passive during its first year of operation. In response to a recommendation from the first annual programme review, the board has now adopted new terms of reference and become more active. In the case of Tilitonse, the first annual review found that the board had been too closely involved in management decisions, to the detriment of its operations.

2.56 While it is not surprising that such boards require time to become effective, they have been held back by a lack of clarity relating to their role. The Ghanaian board members pointed out to us that the lines of accountability are blurred by DFID’s direct contractual relationship with the managing contractor (a consortium led by the international consulting firm, Coffey International). The board has no direct role in overseeing this contractual relationship and, therefore, has no authority in matters such as levels of staffing or management overhead. There is also on-going debate within the board on whether STAR-Ghana should move towards becoming a permanent national entity with its own legal status, which would change the role of the board.

Fiduciary controls are broadly appropriate but programme management is stretched by the high volume of grant making

2.57 The managing contractors are faced with two competing sets of pressure from DFID. First, they need to manage the significant fiduciary risks involved in providing grants to CSOs with limited organisational capacity. Second, they need to meet ambitious spending targets for high-volume grant-making. From the outset of the programme, they are under pressure to begin grant-making as soon as possible. In the case of Tilitonse, this led to the commencement of grant-making before all the management systems were fully in place.

2.58 Our review of the financial management procedures of STAR-Ghana and Tilitonse showed that they are, generally, well designed. There are, however, signs that both programmes are struggling to implement their respective procedures effectively while, at the same time, managing large volumes of grants.

2.59 Applicants are required to present two or three years of audited accounts. With regard to STAR-Ghana, potential grantees undergo a ‘light touch’ due diligence process, based on a questionnaire setting out minimum standards across 18 areas. The assessment is limited to verifying compliance with minimum standards, which are the same for all applicants, whether large and established CSOs or new, local organisations. This does not allow for the identification of specific risk areas for individual grantees to inform capacity development. Tilitonse’s due diligence procedures are more substantial, based on an assessment tool originally developed for UK CSOs.

2.60 Grantees receive their funding in quarterly or semi-annual advances, upon presentation of evidence that the previous advance was properly spent. For STAR-Ghana, this means providing copies of bank statements and cash books; for Tilitonse, it means submitting original receipts. Both programmes provide grantees with capacity development on financial management.

2.61 STAR-Ghana grantees are required to undergo external audits every year, while Tilitonse grantees are required to undergo external audits at least once during the life of the project. There are audit committees within the governing boards that can commission additional internal or external audits.

2.62 An external audit of STAR-Ghana, commissioned by DFID in its second year of operation, found evidence that the due diligence and expenditure monitoring systems were not operating effectively. It examined 15 grantees and discovered that, in many cases, payment transactions were unsupported, bank reconciliations had not been prepared and cash books had not been properly maintained. The Board responded by commissioning an audit of the remaining 66 grantees. It found similar problems in 60% of them. STAR-Ghana responded by suspending grants to the CSOs with the most serious problems, requiring them to take remedial steps as a condition of resumption. It also strengthened its due diligence and monitoring processes. This included the creation of a risk register, in which each grantee is assigned a risk rating and prioritised for monitoring visits, accordingly.

2.63 Beyond these basic fiduciary controls, neither programme has a comprehensive approach to managing fraud and corruption risk. Both programmes include anti-corruption clauses in their grant agreements, which define corrupt practices and provide that any violations are grounds for immediate cancellation. Neither programme has the resources to follow through actively on this provision, with Tilitonse in particular lacking adequate staffing in the financial management area.

2.64 Providing grants to CSOs inevitably entails some level of fiduciary risk, which needs to be mitigated through grant-making procedures that limit DFID’s financial exposure, while building up grantee financial management capacity. While the programmes are attempting to do this, the STAR-Ghana experience suggests that the capacity building support may not be producing the desired results. This appears to be because the volume of grants is too high, making it difficult for the project management teams to give each grantee the individual support and monitoring it requires. DFID should take this into consideration, when deciding on the scale of funding for CSO grant-making programmes.

2.65 We recognise that increasing the level of fiduciary oversight across the board would have significant resource implications for the programme management team. The solution is to have a more active risk-based approach. A more detailed risk assessment of each individual grantee should be carried out during the initial due diligence process. Capacity building activities should be designed to address already identified risks and each grantee’s progress should be individually monitored. Oversight of fraud and corruption should then be proportionate to the level of residual risk posed by each individual grantee. We note that STAR-Ghana’s introduction of a risk register is a step in this direction. Figure A2 in the Annex contains our suggestions on how a more active fiduciary risk management approach can be implemented.

Value for money

DFID should ensure sufficient management resources and non-financial support for the level of grant-making

2.66 The cost-effectiveness of a grant-making instrument is influenced by a wide range of factors, including the level of administrative cost, the balance between financial and non-financial support to grantees and the level of individualised attention they are given by the management team. While there are some economies of scale that can be achieved with larger programmes, the trade-off is that procedures become more standardised, resulting in a potential decline in effectiveness.

2.67 For future programmes, based on the experience of STAR-Ghana, there may be a value for money case for decreasing the number of grants, in order to allow for greater expenditure on capacity building and to increase the scope for the programme managers to provide individualised support to grantees.

2.68 It is notable that DFID’s procurement process resulted in the selection of managing contractors offering very different levels of administrative support for similar programmes. During their inception period, when the two programmes faced similar challenges in putting in place grant-making procedures, Tilitonse had just 6 full-time equivalent positions, compared to 12.4 for STAR-Ghana.23 Although both programme management teams have subsequently been increased, at the time of our visit Tilitonse remained under-resourced. It appears, therefore, that the initial tender process did not make the best assessment of value for money. We are informed that DFID’s tender assessment criteria have subsequently been revised.

The programmes are actively controlling costs

2.69 Both programmes pay close attention to controlling costs within their grant-making but would benefit from a more rounded approach to assess value for money.

2.70 Applicants are required to present budgets that are broken down into individual activities and are transparent on their unit costs (e.g. for a seminar, specifying the daily cost for each participant). There are clear rules on what costs are eligible for inclusion. STAR-Ghana maintains a database of unit costs, based on market rates across the country. These are used to challenge applicants on their budgets. Cost-effectiveness measures also have to be included in project-result frameworks and monitored continuously, with grantees requested to report quarterly on measures they have taken to improve value for money. All this suggests good attention to cost control.

2.71 Both programmes routinely revise proposed project budgets downwards when making their awards; in the case of STAR-Ghana, by 50-60% across the board. The management team informed us that this is often because budget proposals contain overpricing or inadmissible items. We note, however, that this has resulted in most grantees being required to reduce the scope of their activities, either by removing project components or working in a narrower geographic area. In some cases, the grantees informed us that this had compromised their overall strategy. We note that reducing the costs of projects does not necessarily result in increased value for money. Because the budget cuts have been uniform across the portfolio, we are concerned that value for money assessments are not being made individually.

The Kalondolondo delivery model suggests that better value for money options are available for local interventions

2.72 A final value for money issue relates to the use of CSO grant instruments. Running a competitive selection process and providing capacity building support and oversight across a diverse group of grantees necessarily entails substantial management cost.

2.73 By contrast, the Kalondolondo model shows that a direct grant to an established CSO can be used to fund simpler, more standardised interventions far more cost-effectively. Kalondolondo is managed by a consortium comprising Plan Malawi, Action Aid Malawi and the Council for Non-Governmental Organisations, which is a civil society umbrella organisation. It implements its community scorecard assessments through 40 local CSOs, which receive ‘sub-grants’ of no more than £5,000 each on a non-competitive basis. The partners are selected by Kalondolondo on the basis of their ties to the communities where they operate. In addition, they must have, at a minimum, legal identity, a physical office, a project accountant and a basic accounting system.

2.74 Kalondolondo provides its partners with five days of training on how to implement the scorecard methodology. Because most of them work through volunteers, their implementation costs are low. We observed that, even though Kalondolondo’s activities are similar to those of many of the Tilitonse grantees, it is able to deliver them at a fraction of the cost.

2.75 The question of which model – a competitive grant-making process or a direct grant to deliver a standardised activity – represents better value for money depends upon the objectives. A grant-making instrument is better suited to promoting a range of unique and innovative activities. The Kalondolondo model is better suited to tried and tested interventions that need to be implemented in a standard way across multiple sites. STAR-Ghana and Tilitonse have, to some extent, tried to pursue both objectives, with the risk that they are unable to do either one cost- effectively. Kalondolondo, on the other hand, has delivered some significant development impact for modest expenditure, as discussed in the next section.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.76 In this section, we look at the emerging impact from the three programmes. The programmes are at a mid-point of implementation and we viewed only a part of their total activities. Our findings, therefore, are based on the results observable at present and our scoring relates to whether the programmes appear able to deliver the type of results they intend.

The numerical targets set for the programmes provide little information on results for the intended beneficiaries

2.77 Each of the programmes has indicators, milestones and targets for measuring its outcomes and outputs. We found, however, that these indicators are of little help in assessing what has been achieved for the intended beneficiaries. The milestones appear to be arbitrary, with the programmes over-shooting their targets as often as failing to meet them. Although there is some narrative description of individual results in STAR-Ghana’s reports, it is not sufficient to enable us to interpret the significance of the results. Indeed, we find that the emphasis on numerical measures of results is getting in the way of qualitative analysis of what changes are occurring and their significance.

2.78 STAR-Ghana and Kalondolondo appear to be broadly on track to achieve their planned outputs and outcomes. Tilitonse’s first annual report contains few data on results, although it does provide some examples of outputs achieved by individual grantees.

2.79 STAR-Ghana’s intended outcome is ‘increased civil society and parliamentary influence in the governance of public goods and service delivery’. It measures progress towards this goal through the following indicators:

- the number of times duty bearers (i.e. government, traditional authorities or the private sector) have engaged with citizens as a result of STAR-Ghana projects:24 currently 31 against a milestone of 15;

- the number of grant partners invited to contribute to duty bearer decision-making: currently 38 against a milestone of 70; and

- the number of times parliamentary committees have engaged proactively with STAR-Ghana grantees: currently 3 against a milestone of 3.

2.80 At the output level, there has been an improvement in grantee capacity, in both technical areas and general organisational capacity. The grantees are delivering their projects on schedule. A key output is the generation of evidence to inform government policy and practice. To this end, 41 grantees have generated evidence, which has been communicated to policy-makers in 32 cases and taken into consideration in 21 (all three figures are ahead of target).

2.81 Kalondolondo reports that it has involved 35,000 citizens in its scorecard assessments (against a milestone of 20,000), carried out 1,869 individual assessments of services or development projects (against a target of 2,000) and organised 55 meetings between communities and local authorities (above the target of 45). It has helped to influence local authorities in 35 cases over 14 districts (against a target of 30). On six occasions, it has been invited by government agencies to carry out a scorecard assessment, outside its planned programme (ahead of target).

The programmes are achieving constructive community engagement with government

2.82 We conducted our own assessment of emerging results from the 22 projects we visited in Ghana and Malawi (see Figure A1 in the Annex for the full details of our methodology and the results). We categorised the results from each project, according to a qualitative scale of our own devising, in order to identify patterns in the emerging results. The exercise demonstrated that the three programmes are generally achieving a good range of results at the local community level, corresponding broadly to what the World Bank calls the ‘short route’ of accountability through direct citizen engagement with government. These results included:

- communities reporting increased collective sense of empowerment (14 out of 22 projects);

- community members demonstrating improved knowledge of their rights and the responsibilities and performance of government (16 out of 22);

- community decision-making processes being more coherent and inclusive (13 out of 22);

- increased and more constructive interaction between the intended beneficiaries and local duty bearers (17 out of 22); and

- localised solutions having been found to problems identified by communities (15 out of 22).

2.83 These local results were most striking in Malawi and in the poorer regions of northern Ghana, where community empowerment starts from a lower base. Examples of some of the results we saw are given in Figure 5 on page 18.

2.84 This assessment methodology has some limitations. As we did not have baselines (i.e. analysis of the situation prior to the project), we relied on beneficiary accounts of the changes that had occurred, which may lead to some over-statement of results. We mitigated this risk with questions designed to identify the sequence of changes claimed by the communities and how they had occurred. Any residual bias is likely to be towards over-claiming of results.

Promoting community engagement in education

The Regional Advisory Information and Network Systems (RAINS) is a Ghanaian CSO working to strengthen School Management Committees (SMCs) in Northern Ghana and it has established a multi-stakeholder platform to address issues of concern to the community (see Figure 2, Example 1 on page 5). In the two villages we visited, we learned that the SMCs had become much more active through the encouragement of RAINS, with a clearer understanding of their role and responsibilities. By lobbying the district authority and the Ghana Education Service, the SMCs had achieved the recruitment of additional teachers and funding for new school buildings. The stakeholder platform successfully negotiated with the lorry drivers’ union not to allow unaccompanied girls to hitchhike, a practice that exposes them to the risk of trafficking.

Empowering women

Oxfam Malawi is working to empower local women across four districts in southern Malawi (see Figure 2, Example 2 on page 5). According to one of the beneficiaries we interviewed, the project ‘urges people to get angry about their situation and to take action for change’. The women we met reported a range of results, many of them of a self-help nature. Many people living with HIV-AIDS have disclosed their status and begun speaking out in community groups and forums. Local networks have been formed to tackle violence against women. Communities have come together to carry out community policing, create nursery schools and develop Village Savings and Loan groups. The latter help to protect vulnerable women from economic shocks, while enhancing their self-confidence and social status.

The communities have also increased their interaction with local authorities. The project has organised a number of meetings between communities and government officials. The latter informed us that they appreciate these efforts, as local authorities otherwise lack the resources to engage with communities. There has been some resulting improvement in local services, including the introduction of mobile health clinics and improvements to the administration of the Farm Input Subsidy Programme (FISP). The project has also supported some local women to participate in national consultations on Malawi’s Post-2015 Development Agenda.

In many cases, however, local authorities are unable to respond to the demands made by communities, due to inadequate financial and human capacity. The project acknowledged the risk that communities will become disillusioned if their heightened expectations cannot be met.

Controlling corruption in fertiliser subsidies

The Kalondolondo programme in Malawi uses community scorecards to collect feedback on the delivery of development projects and public services (see Figure 2, Example 5 on page 5). Community members in several villages that we visited reported to us that the evidence collected through the scorecard process had made them better placed to negotiate with local authorities. In one of several successful initiatives, Kalondolondo surveyed the FISP programme, through which the poorest rural households across Malawi receive coupons for the purchase of subsidised seed and fertiliser. According to the communities we met, the FISP programme has had major corruption problems, with subsidised inputs often acquired fraudulently by merchants, causing the intended beneficiaries to miss out. Kalondolondo produced evidence that a poorly organised distribution system was exacerbating the problem. Following its representations to national authorities (although not solely attributable to Kalondolondo), the distribution system was modified. All beneficiaries from a particular group of villages are now scheduled to purchase their inputs on a particular day, in alphabetical order, with the community itself policing the process. Because community members are well known to each other, interlopers are easily detected and excluded. The communities we visited reported that this had resulted in major improvements to the programme.

2.85 The pattern is, nonetheless, instructive. It suggests that the projects are delivering localised results at a good rate. They are promoting community empowerment and self-help and encouraging better interaction with local service providers. Many have proved effective at identifying blockages or inequities in the delivery of services and at negotiating local solutions, often with elements of community self-help. For example, they encourage communities to participate actively in the running of local schools or to contribute their labour to local development projects. These types of impact are not currently being captured by programme monitoring systems. Our project sample included various techniques for community empowerment, such as community scorecard assessments of local services, economic literacy training and participatory planning. Provided they were competently administered, it appeared to make little difference which approach was used. They all shared the common element of skilled facilitators helping communities to analyse and articulate their needs and engage constructively with local authorities. The facilitators were often local volunteers. The most effective projects were those delivered by CSOs that have established strong relationships with the communities where they work.

2.86 It is notable that the results we identified at this level did not involve adversarial accountability processes. They worked by finding solutions that were in the common interest of all parties. In fact, the projects also delivered clear benefits for local service providers. The local authorities in question were able to operate more effectively within the limits of their resources and enjoyed greater legitimacy, as a result of improved interaction with communities. We observed that local accountability emerged from the increased frequency and quality of interaction between communities and local authorities, rather than through explicit redress for poor performance.

2.87 We observed a good example of this type of result in northern Ghana, where a local community-based organisation, called the District Civic Union (DCU),25 had been working with a group of women traders. The women refused to pay a charge to the District Authority for the use of the local market because they believed the revenues would not be properly used. Communication between the two sides had broken down. DCU brokered a solution whereby the women began paying the charge after the District Authority agreed to post details on its notice board of how much revenue was collected and how it was spent, as well as giving the women a right to negotiate over the level of the charge. The initiative opened up a regular channel of communication between the women and District Councillors, through which a number of other local problems were raised and resolved. This kind of ‘collective action problem’, stemming from a lack of trust and poor communication, is often amenable to solutions identified by an external facilitator.26

2.88 It is important, however, to be realistic about the results that can be achieved through local social accountability initiatives. In both countries, impacts were constrained by the limited power and resources available to local authorities. In Malawi, we noted some instances where community mobilisation without an effective government response had led to frustration and a sense of disempowerment. Linking local empowerment activities to increased local development budgets (as is commonly done in community-driven development programmes) might be one way of reducing this risk.

2.89 In Ghana, we visited fishing communities in the Western Region that were affected by the oil and gas industry, who were clearly already angry and highly mobilised. In this context, offering further awareness raising without credible solutions runs a real risk of triggering conflict.

Results at the national level are more difficult to achieve

2.90 Our scoring reveals a thinner set of results for CSO advocacy at the national level. While 11 of the 22 projects had collected evidence to feed into national decision-making processes, we saw only 4 instances where it had been taken into consideration. This had led to three examples of changes to national programmes, two instances of changes to policies or plans and two changes to budget allocations or expenditure patterns. In terms of concrete impact for the intended beneficiaries (namely, the public at large), the projects in our sample achieved improved security in Ghana’s last election (Penplusbytes), reduced corruption in Malawi’s fertiliser subsidy programme (Kalondolondo) and, arguably, made some improvements to basic education in Ghana (Ghana National Education Coalition Campaign). While some of these projects may deliver additional advocacy results in due course, it is clear that national impact is significantly harder to achieve.

2.91 In earlier programmes in Ghana, DFID has helped to finance civil society campaigns, such as gender equality and the rights of people with disabilities, in areas that are not particularly contentious in national politics. In the absence of strong political interest, sustained lobbying eventually led to the adoption of new policy statements and laws. We are informed, however, that implementation of these commitments has been slow and the practical results limited.

2.92 In politically contested areas, such as oil and gas in Ghana, policy-making is necessarily a very complex process. CSOs are only one voice among many. While a CSO campaign may, from time to time, make a decisive difference, such successes depend upon sets of political conditions that are transitory and difficult to replicate. Furthermore, successful instances of CSO lobbying fall within the normal politics of policy-making.27 They would not, of themselves, result in more accountable and responsive government, which is the kind of transformative social and political change that DFID seeks in its theory of change (see Figure 3 on page 7).