DFID’s governance work in Nepal and Uganda

1. Purpose, scope and rationale

This performance review will assess the relevance and effectiveness of DFID’s governance programming in Nepal and Uganda. It will explore what progress has been made towards improved governance outcomes and how this has contributed to achieving DFID’s higher-level objectives, including promoting democratic governance, supporting economic development and providing sustainable basic services in the two countries. It will also consider how well DFID is adapting its governance approach as a result of lessons learned from its programming.

‘Governance’ is about the use of power and authority and how a country manages its affairs… It concerns the way people mediate their differences, make decisions, and enact policies that affect public life and social and economic development.

Governance is a substantial area of DFID’s programming. In 2015 DFID spent £628 million on its governance portfolio, 86% of the UK’s total governance aid.1 Within DFID, governance is both a substantive area of programming and a cross-cutting theme running across other sectoral programming, including on service delivery and inclusive growth. DFID identifies its specialist governance competencies as covering the following programming areas:

- security, justice and human rights

- accountability and inclusive politics

- public sector governance and service delivery

- inclusive growth and economic development

- public financial management and domestic resource mobilisation

- anti-corruption.

ICAI has previously looked at individual elements of DFID’s governance work,2 but has not reviewed how the whole of its governance portfolio works in its country programming. This review will therefore focus on DFID’s country-level governance programming in two countries, Nepal and Uganda. This will allow meaningful findings to emerge at the country level, but is also expected to highlight key themes relevant to DFID’s broader approach to governance.

The review will focus on DFID’s governance programming in Nepal and Uganda between 2009 and 2015 (inclusive), allowing ICAI to consider emerging evidence of sustainable impact. We will also review evidence from some programming after this period, noting that sustainable results may not yet be clear. The review will therefore take into account DFID’s strategic approach to governance to 2017.

At the country level, the review will look at all programmes specifically designed to support governance in Nepal and Uganda (hereafter referred to as ‘governance’ programmes). It will also look at other sectoral programmes where governance has been embedded as a strong cross-cutting theme (hereafter referred to as ‘other sector’ programmes). Finally, the review will encompass centrally managed programming that contributes to supporting governance in Nepal and Uganda.

This review will not cover governance programming by other UK departments, some of which is addressed in other past, ongoing or planned ICAI reviews.3 It will, however, consider how DFID works with other departments in the review countries to help achieve its governance objectives.

While the scope of this review is limited to Nepal and Uganda, the findings and recommendations are highly likely to be relevant to DFID’s broader governance portfolio. We expect the review to provide insights on how governance programming and governance advisory expertise help to achieve some of the most important high-level goals of the UK aid programme, such as overcoming conflict and fragility, promoting transparency, accountability and open democracy, and building a favourable policy and institutional environment for inclusive economic development. The review will also explore the changing role of DFID governance advisors and how well they support these strategic objectives.

2. Background

The UK government prioritises improved governance as a critical building block for overcoming fragility and promoting economic development. It has set out its commitments on governance in a number of policy and strategy documents, including the 2015 Strategic Defence and Security Review,4 the 2015 Aid Strategy,5 the 2016 Bilateral Development Review,6 DFID’s Single Departmental Plan7 and the 2017 Conservative Party Manifesto.8 The UK has also highlighted its commitment to building governance by using its influence to secure the inclusion of a Sustainable Development Goal on peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG 16).9

DFID has more than 110 specialist governance advisors. Their role is to understand governance evidence, policy and practice in a range of settings; demonstrate knowledge of political systems, core governance concepts and global, regional and transnational drivers of governance change; and have the ability to apply political and institutional analysis in order to influence strategic planning and programming decisions across DFID and the wider UK government.10

DFID has been a strong advocate within the donor community of improving approaches to governance programming, including through its work on the use of political economy analysis. It has also been a supporter of new approaches such as the ‘Doing Development Differently’ manifesto, the ‘Thinking and Working Politically’ community, and problem-driven, iterative approaches to capacity development.11 These approaches stress the importance of flexible, politically-informed programming to identify locally led solutions to complex development challenges.12

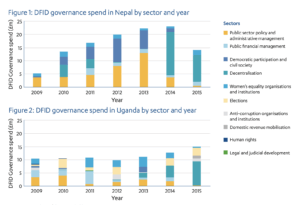

DFID has large governance programmes in both Nepal and Uganda. During the review period DFID Nepal spent £114.7 million on its country-level governance programming, accounting for 2.7% of the total UK aid spend on governance between 2009 and 2015 (inclusive). DFID Uganda spent £78.9 million on its country-level governance programming in the review period, accounting for 1.9% of the total UK aid spend on governance between 2009 and 2015 (inclusive).13 The range of programming in both countries includes significant support for central-level policy-making and administrative management, public financial management, decentralisation and democratic participation. Figures 1 and 2 on the following page provide an indicative breakdown of DFID’s governance spend in Nepal and Uganda respectively across the review period.

Source: ICAI analysis of data provided by DFID.

Spend by category calculated using DFID data on spend against each OECD DAC governance sub-sector.

3. Review questions

This review is built around criteria of relevance, effectiveness and learning, and will address the questions listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Area of spend | Total expenditure April 2024 to March 2025 |

|---|---|

| Secretariat pay costs | £812,170 |

| Commissioners’ pay and honoraria costs | £184,923 |

| 2024-25 office rent costs | £92,280 |

| 2023-24 office rent costs* | £6,340 |

| Travel costs | £9,789 |

| Office costs including training and office equipment | £30,422 |

| Total administration spend | £1,135,924 |

4. Methodology

This review will use a variety of methods to collect and triangulate evidence. It will begin with a thorough review of relevant strategic and operational literature (both internal and external to DFID). This will capture DFID’s key policy commitments and strategic approach to governance, setting these in the context of wider UK government thinking on development. A review of other donor approaches to strengthening governance will also support assessment of the relevance of DFID’s governance programming in light of the broader donor landscape. The review will then focus evidence gathering on reviews of DFID’s governance work in the two countries over seven years of recent programming. This will seek to establish whether programming was consistent with UK government policy, relevant to the country context and coordinated with the broader donor landscape. It will also explore the effectiveness of DFID’s country-level engagement on governance and the sustainability of its governance programming (in other words whether benefits continued or are likely to continue beyond the programme period). It will include looking at the approaches used to seek reform, with both state and non-state actors. Our evidence gathering approach will be deliberately in-depth, with an emphasis on testing sustainability. It will also explore how DFID’s approach to governance programming and related policy advocacy has developed over time and will include looking at how DFID considers and manages value for money across its governance work.14 Wherever possible the review will seek to identify and highlight key themes relevant to DFID’s broader approach to governance.

Component 1 – Literature review: We will carry out a succinct summary literature review exploring development assistance in the governance area. It will cover themes such as: (i) how theories of change in governance programming have evolved over the past decade; (ii) good practice in technical assistance, policy influence, capacity building, promoting democratic accountability and related areas; (iii) the evidence on what kinds of results are achievable in governance programming and how to identify sustainable results. This will enable us to reflect on and assess DFID’s strategic approach to governance, including how this is interpreted and made operational at the country level in Nepal and Uganda.

We will also prepare literature reviews on each of the two countries. These will assess literature on the governance context, including the type of political system, political economy analysis, links between governance conditions and economic performance, and any literature on governance in particular sectors or thematic areas relevant to DFID’s programming (for example democratic governance and deepening democracy, public financial management and revenue reform and decentralisation). The reviews will also cover the donor landscape and the history of donor efforts to support governance reform. They will provide contextual evidence to support our assessment of whether DFID’s approaches, programming and results are appropriate in each country.

Component 2 – UK-based interviews, focus groups and survey: We will undertake a series of interviews and focus groups with DFID centrally. This will enable us to explore DFID’s corporate and strategic approach to governance over the review period. It will also allow us to locate the review findings in DFID’s current operational context, exploring, for example, the changing role of DFID’s governance advisors and transitions towards more flexible and adaptive programming at the central level. Where possible we will also meet with previous DFID governance advisors who were based in Nepal or Uganda during the review period but are now based elsewhere. We will also undertake a short web-based survey of the current DFID governance cadre.

Component 3 – Country portfolio analysis: We will explore DFID’s approach to governance in Nepal and Uganda through in-depth desk-based reviews of the portfolio in each country, along with country visits. The desk-based component will include two main parts.

Part one will review DFID’s country-level policies, strategies and analytical work relating to governance, such as drivers of change, political economy analysis, conflict analysis, inclusive growth and country poverty reduction diagnostics. These will be assessed by reference to DFID’s overall policies, strategies and guidance and to the findings of our literature reviews.

Part two will involve a thorough review of project documentation for all governance programmes and for selected other sector programmes in the two countries, using a programme assessment framework developed alongside the overarching methodology framework. We will explore how DFID’s approach and programming choices have evolved over time. We will explore how well DFID has advanced governance objectives across its other sector programming. We will, for example, consider whether DFID has appropriate resources in place to effectively deliver governance objectives across other sector programmes and how governance challenges to programme delivery are being identified and addressed at the sector level. We will also explore whether DFID’s programme management systems support good practice in governance programming, including the shift towards more flexible and adaptive programming. We will assess the coherence of the country’s portfolio against DFID’s stated objectives and explore issues of coordination. We will collect evidence of results and compare these to programme objectives, to identify patterns of performance. We will also collect evidence of lesson learning feeding into programmes (for example highlighted in business cases) and lesson learning being captured from programmes (such as from annual reviews and programme completion reports). This will allow us to identify whether lessons learned have led to changes in the design and approach of new programming and also whether changes are being made to active programming as a result of lesson learning.

Component 4 – Centrally managed programme analysis: Assessing DFID’s approach to governance programming in Nepal and Uganda will also involve reviewing relevant centrally managed programmes active during the review period. This will include centrally managed governance programmes with activities in Nepal or Uganda and similarly any centrally managed programmes in other sectors that include a strong governance focus in either of the two countries. Given the large number of centrally managed programmes active in the two countries, we will select a sample for review. During our country visits, we will also consult with DFID country office staff and review evidence of what contributions these centrally managed programmes have made.

Component 5 – Country visits: We will undertake two country visits, one in Nepal and one in Uganda. These will build on and triangulate evidence and findings from the country portfolio analysis and the centrally managed programme analysis, as well as from the literature reviews. For each visit, an independent governance expert based in Uganda and Nepal will join the core team. During the visits, we will meet with a range of stakeholders, including DFID staff, other donors, implementing partners, beneficiaries and independent observers. In-country stakeholder interviews and focus groups will allow feedback on the relevance and effectiveness of DFID’s governance approach and programming, including how well DFID works with a range of partners and how well its approach is aligned to national strategies and priorities. Most of our interviews and consultations will be held with stakeholders based in the capital cities, supported by targeted field visits. Field visits will be used primarily to verify DFID’s claimed results and assess the extent to which they have been sustained over time.

5. Sampling approach

ICAI has chosen to review DFID’s governance work in one Asian and one African country. Nepal and Uganda were selected from a shortlist of ten countries. The main selection criteria for the shortlist were the overall size of the governance portfolio, sustained governance spends across the review period and breadth of thematic coverage within the governance portfolio (based on OECD aid statistics coding). The selection also sought to include different country contexts, including the policy and institutional environment (using the World Bank’s country poverty and institutional assessment scores and trends),15 levels of corruption and quality of electoral processes.

DFID Uganda had a good level of active programming in ten out of the 12 governance sub-sector classifications in the OECD aid statistics during the review period, while DFID Nepal had a good level of active programming in seven. The total expenditure on governance programmes (in other words total expenditure under all 12 sub-sectors) during the review period was £114.7 million in Nepal and £78.9 million in Uganda.16 The two countries therefore have sizeable governance portfolios. Both also face a range of fragility and governance challenges, and are therefore likely to offer insights and lessons with implications across DFID’s governance portfolio.

As this is an in-depth performance review focused on only two country portfolios, we will review all of the governance programmes in Nepal and Uganda active within the review period. We will also review a sample of other sector programmes at country level and a sample of centrally managed programmes with a governance focus in Nepal and Uganda. Our sampling strategy will identify a selection of DFID’s programmes that include varying spends being delivered through a variety of implementing partners and delivery mechanisms. We will ensure the programmes selected are as representative of DFID’s work in those countries as possible. This will enable us to review DFID’s large-scale programming and also smaller, often more innovative work, across a range of thematic and geographical areas.

Across the two countries, we expect to review 44 governance programmes, implemented by at least 40 different partners, including other bilateral donors, multilateral agencies, international non-governmental organisations and research foundations, national government agencies, and local non-governmental organisations and civil society organisations. The other sector and centrally managed programmes with a governance focus will be in addition to these 44 governance programmes.

6. Limitations of the methodology

The challenge of measuring and attributing results from governance programmes is widely recognised in development literature.17 Governance programming typically involves attempts to influence broader change processes that play out over years, if not decades. The volatile nature of governance, particularly in fragile states, can also result in regressions during the lifetime of a programme. Results therefore take time to emerge, and are often difficult to attribute to DFID’s specific programmes of support.

Our judgements will be informed at two levels. We will use DFID’s own evaluative standards, as set out in its strategic and programmatic documents,18 to look for evidence of how DFID is assessing its performance at the programme level, and, based on the evidence available, what can be said about a programme’s contribution to its expected results. We will also test whether DFID’s programming is having an impact at a more strategic level; in other words whether it has made a plausible contribution towards achieving the UK’s broader policy objectives. Our evidence will to some extent therefore depend on the quality and availability of DFID’s project and programme assessments in its country offices.

This review’s focus on two country-level governance portfolios could limit how useful the review findings are to DFID more broadly. While our findings will not be representative of the governance portfolio as a whole, we do expect the review to highlight key themes relevant to DFID’s broader approach to governance. This may include, for example, findings on the changing role of governance advisors and changes in the quality of governance portfolios over time.

7. Risk management

The following table captures the main risks identified and the mitigating actions that will be taken.

Table 2: Main risks and mitigating actions

| Area of spend | Phase 3 April 24 to June 24 | Phase 4 July 24 to March 25 | Total expenditure April 2024 to March 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier costs | £312,171 | £734,545 | £1,046,716 |

| External engagement activities | £6,320 | £45,047 | £51,367 |

| Total programme spend | £318,491 | £779,592 | £1,098,083 |

8. Quality assurance

The review will be carried out under the guidance of ICAI commissioner Tina Fahm, with support from the ICAI secretariat. The review will be subject to quality assurance by the service provider consortium.

Both the methodology and the final report will be peer reviewed by Pierre Landell-Mills, a principal of The Policy Practice, a consulting company specialising in political economy issues.

9. Timing and deliverables

The review will be conducted within around nine months starting from September 2017.

| Phase | Timing and deliverables |

|---|---|

| Inception | Approach paper: December 2017 |

| Data collection | Country visits: November 2017 to January 2018 Evidence pack and emerging findings presentation: February - March 2018 |

| Reporting | Final report: summer 2018 |

Footnotes

- ↩ Calculated from data provided by DFID.

- ↩ For example DFID’s approach to anti-corruption and its impact on the poor, 2014, link and DFID’s empowerment and accountability programming in Ghana and Malawi, 2013, link.

- ↩ Including The cross-government Prosperity Fund, ICAI, 2017, link, and the upcoming review Conflict, Stability and Security Fund, ICAI, 2017, link.

- ↩ National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015, UK government, link.

- ↩ UK aid: tackling global challenges in the national interest, HM Treasury and DFID, 2015, link.

- ↩ Rising to the challenge of ending poverty: the Bilateral Development Review 2016, DFID, link.

- ↩ DFID’s Single Departmental Plan 2015-2020, DFID, 2016, link.

- ↩ The Conservative and Unionist Party Manifesto 2017, link.

- ↩ UK implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals, First Report of Session 2016-17, House of Commons International Development Committee, June 2016, link.

- ↩ Technical Competency Framework for Governance, DFID, 2016, link.

- ↩ ‘Escaping Capability Traps through Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA)’, Andrews, M, Pritchett, L & Woolcock, M, Center for Global Development, Working Paper 299, June 2012, link.

- ↩ The World Bank’s World Development Report 2017 on governance also recognises the importance of moving from a focus on achieving the right policies for development to understanding the bargaining processes through which policies emerge, given local institutions and power relations, link.

- ↩ Calculated from data provided by DFID.

- ↩ Where relevant, this review will build upon analysis and evidence gathered in ICAI’s ongoing review of DFID’s approach to value for money in portfolio and programme management.

- ↩ Historical scores are available on the World Bank website: link.

- ↩ Calculated from data provided by DFID.

- ↩ See On Measuring Governance: Framing Issues for Debate, World Bank, 2007, link and The difficulty of measuring Governance and Stateness, EUI, 2015, link.

- ↩ For example, targets set out in original programme documentation, including the business case and annual reviews, and reflected also in DFID’s own evaluations.