DFID’s Health Programmes in Burma

Executive Summary

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review.

Green: The programme performs well overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Some improvements are needed.

Green-Amber: The programme performs relatively well overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Improvements should be made.

Amber-Red: The programme performs relatively poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Significant improvements should be made.

Red: The programme performs poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Immediate and major changes need to be made.

Burma (also known as Myanmar) is a fragile state, one of the poorest countries in Asia, with a long history of political unrest and armed conflict. Following elections in 2010, the country is now undergoing rapid change. The UK is the largest international donor to Burma. It spends almost half of its Burma expenditure on health, £110 million over the period 2010-15. This review assesses whether DFID is achieving impact and value for money in Burma through its aid to the health sector.

Overall

Assessment: Green

DFID has designed and delivered an appropriate health aid programme in a country where there is significant health need and where there are significant challenges of access and capacity. DFID has demonstrated clear leadership in working well with intended beneficiaries, other donors, delivery partners and the Government of Burma’s Ministry of Health. The health programme has addressed many health needs, although demonstrating the impact of DFID’s health programmes has been difficult given the lack of good data in Burma.

Objectives

Assessment: Green

DFID’s health programme has identified and balanced the health needs of the Burmese people with the longer-term objective of helping the Government of Burma to develop a robust public health system. We consider DFID Burma’s health objectives to be sound. DFID has taken the lead in a challenging environment, complementing the work of other donors and contributing to the peacebuilding process by working in conflict-affected and ceasefire areas. By developing relationships at the local level, DFID has helped to create a bottom-up approach to identifying health needs which has informed the design of health programmes and has prepared the ground for stronger state–citizen relationships in the future. There is, however, a lack of a clear approach for engaging with the informal and for-profit sectors which accounted for up to 85% of health expenditure in Burma in 2011.

Delivery

Assessment: Green

The health programme has delivered against its objectives and has helped to address the needs of intended beneficiaries. Good governance, sound financial management and risk management are integrated into the design and delivery of each intervention. Administrative and overhead costs of the programmes need to be understood better by DFID to help to ensure that delivery costs represent value for money.

Impact

Assessment: Green

Programme targets have, on the whole, been achieved. The health impact to date has been positive, insofar as it can be measured, although there is a risk that attribution to DFID may have been over-estimated by an independent evaluation. Intended beneficiaries who we met in Burma, including people living in the Irrawaddy Delta and intravenous drug users suffering from HIV/AIDS, supported this view of positive impact. Despite being largely humanitarian, the programme has been implemented in the light of longer-term, strategic objectives for the wider health sector. As a result, the prospects of generating better health impacts in the future, from the solid foundations built through DFID’s presence and leadership in the sector, are good.

Learning

Assessment: Green-Amber

DFID is sensitive to the context of working in Burma and is taking account of lessons learned. Recommendations from end-of-programme evaluations have been taken on board in new designs, especially around future monitoring and evaluation. The physical, political and aid context for generating evidence in Burma is very challenging. As a result, the monitoring of outcomes is difficult, due to a lack of robust baseline data. DFID could have done more work to establish baselines. It is now doing so for the new Three Millennium Development Goals (3MDG) Fund, which brings together previous programmes as well as new areas of health activities. The 3MDG Fund also presents significant risks as it needs to be highly flexible in a rapidly changing Burma. Also, there is a risk that critical corporate memory could be lost as long-serving DFID staff are replaced.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: DFID should leverage its relationship with the Ministry of Health and its experience in Burma to date to focus the in-flows of health aid and accelerate the building of a more robust health system, including better integration of the for-profit sector.

Recommendation 2: DFID should work with other donors and the Ministry of Health to capture better quality information about the health sector in Burma and to create stronger and more robust monitoring systems and data baselines across key health programme areas.

Recommendation 3: DFID should work with all parties to ensure the potential risks of the 3MDG Fund programme are identified and addressed, including management of the UNOPS contract, to ensure that the Fund is mobilised, executed and monitored effectively.

Recommendation 4: DFID should ensure that, at this crucial time in developing its health programme in Burma, the impact of key personnel changes in the DFID office is minimised, including the timing of staff transfers and the development of a robust plan to ensure that key relationships are maintained.

1 Introduction

Purpose of the review

1.1 The purpose of the review is to assess whether the Department for International Development (DFID) is achieving impact and value for money in Burma through its bilateral aid to the health sector.

1.2 DFID’s overall health goal for Burma is ‘to address the basic health needs of the poorest and most vulnerable and maximise the contribution of the programme to longer-term change that addresses the root causes of conflict and fragility in Burma’.1 We reviewed six of the nine projects in DFID’s health programme in Burma. This programme accounted for £23 million of UK expenditure in the period 2010-12 and an additional £87 million in the period 2012-15.2

Burma

The political environment in Burma is changing rapidly

1.3 Burma shares borders with Thailand, Laos, China, India and Bangladesh. It has a population of just over 48 million.3 Burma was under military rule from 1962 to 2011, which included extended periods of armed conflict between the Government of Burma and a number of domestic insurgencies.4 More than five decades of political unrest and armed conflict have displaced more than 450,000 people to the east of the country.5 Around 150,000 Burmese refugees are currently living in camps on the Thailand–Burma border.6

1.4 Elections in November 2010, although described by independent observers as falling well short of international standards,7 marked the beginning of a political transition. A largely civilian Parliament was convened in January 2011 and has since enacted a series of economic and political reforms. In 2012, however, there were serious incidents of violence between different ethnic and religious communities living in Rakhine State. The risk of further violence remains high.

Burma is a poor country with an inadequate public health service

1.5 Burma is one of the poorest countries in Asia. Decades of isolation and poor economic management have resulted in an underdeveloped private sector and very limited public expenditure on basic services. The population remains dependent on agriculture, which is mainly at subsistence level. Although poverty data are unreliable, a 2010 United Nations Development Programme survey suggested that a quarter of the population lacks the resources to meet basic needs.8

1.6 Burma’s health indicators are among the poorest in Asia. It is unlikely to meet its health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by 2015 without a significant improvement in service provision for the most vulnerable people. The average life expectancy is 65 years, while the child mortality rate is 62 per 1,000 births.9 The country has one of the highest burdens of disease from malaria, tuberculosis (TB) and malnutrition in the world. A strain of malaria that is resistant to the newest drug treatments has emerged along Burma’s eastern border. This presents a threat to malaria-control efforts in the region and, indeed, globally.

1.7 Burma’s public health system is in a very poor condition. The World Health Organization has identified the six building blocks of a functional health system as: health financing; health planning and management; a well-performing health workforce; infrastructure, drugs and supplies; health information systems; and leadership and governance.10 The health system in Burma displays significant weaknesses in all of these areas.11 This undermines its capacity to deliver basic health care, particularly to the poorest and most vulnerable.

1.8 In 2011, the Government of Burma spent £1.80 per person per year on health.12 This figure does not, however, include the substantial ‘out-of-pocket’ expenditure13 which accounts for over 85% of health expenditure in Burma. Spending in the informal and for-profit sectors represents a significant proportion of this expenditure. The informal and for-profit health sectors in Burma covers private clinics and doctors to non-qualified health workers and itinerant pharmaceutical sellers. The sectors also include fees charged for food and drug costs incurred at state-run public health facilities.

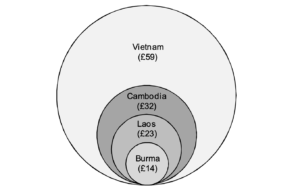

1.9 When the out-of-pocket expenditure is added to the provisions of the Government of Burma, total health expenditure in 2011 rises to £14 per person.14 This figure is low compared to other South East Asian countries; see Figure 1.

Corruption and restrictions in Burma make delivering aid difficult

1.10 Burma ranks 172 out of 176 countries in the Transparency Corruption Perceptions Index 2012.15 Our report on DFID’s Approach to Anti-Corruption, published in 2011, recommended that DFID programme countries with high rates of corruption should ‘develop an explicit anti-corruption strategy’,16 which DFID Burma has done.

1.11 The UK has been bound by a European Union (EU) Council Decision that no development assistance to Burma should be implemented through the Government of Burma. Rather, it should be implemented through United Nations (UN) agencies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and local civilian administrations.17 In May 2013, the restriction on providing development support to the Government of Burma was lifted by the EU, in recognition of progress on political reform.

1.12 The Government of Burma restricts and controls the activities of international NGOs. A memorandum of understanding (MoU) between the government and the international NGO must be agreed, specifying what type of aid is to be delivered and where. It also places restrictions on which data may be collected by the international NGO. Local NGOs are not required to agree MoUs but are required to register with the Government of Burma’s Ministry of Home Affairs.

UK aid contribution to Burma

The UK is the largest donor to Burma

1.13 The UK Government spent £70 million in aid to Burma in 2010-12. Health expenditure represented a third of the total aid expenditure during this period.18 In 2012-15 health expenditure will increase to be almost one-half of the DFID Burma aid budget; see Figure 2.

![[Chart showing sector spending from 2010-11 to 2014-15, including Health, Governance, Education, Poverty/hunger/vulnerability, Humanitarian, and Wealth creation]](https://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/Screenshot-2025-03-31-at-16.11.18-300x182.png)

1.14 The UK Government is one of the largest donors of aid to Burma and in 2010-11 provided more aid than any other country (see Figure 3).

| Rank | Donor | £ millions |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | United Kingdom | 33.7 |

| 2 | EU institutions | 33.1 |

| 3 | Japan | 28.6 |

| 4 | Australia | 28 |

| 5 | United States | 19.1 |

| 6 | The Global Fund | 14 |

| 7 | Norway | 13.3 |

| 8 | UNICEF | 10.8 |

| 9 | Sweden | 10.2 |

| 10 | Germany | 9.5 |

Source: OECD–DAC, World Bank20

Our approach

1.15 This review focusses on DFID Burma’s spending on health. The projects we reviewed were at different stages of maturity, ranging from the development stage to end of life. Figure A1 in the Annex shows a timeline of DFID’s health programme.

1.16 We have, therefore, assessed the impact of more mature programmes and how the learning from these programmes has been incorporated into the design of the new programme. As part of the review, we:

- undertook a background literature review;21

- received briefings from DFID Burma staff; and

- conducted field visits to the Irrawaddy Delta region, Shan State region and camps for displaced people in northern Thailand.

1.17 The views of intended beneficiaries were very important to us and we met approximately 150 receivers of health care services provided through the programmes. During our field visits, we also undertook over 40 interviews, including with Burma Ministry of Health officials, the British Ambassador to Burma, UN organisations, the World Bank, other donors and project delivery partners.

The projects covered in this review ranged in complexity in terms of size, scope, coverage and funding

1.18 The DFID health programme from 2006-12 consisted of nine projects. Figure 4 provides details of DFID Burma’s health projects, indicating those that we reviewed. The Annex contains information on the intended beneficiaries, organisations and people interviewed during the ICAI review.

| Project title | Allocation | Dates | Funding channel and aims | Reviewed by ICAI? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3MDG Fund23 | Up to £80 million24 | 2012-16 | Multi-donor trust fund managed by UNOPS The programme has been in design since 2010 and started in January 2013. DFID is contributing £40 million to the programme in the period 2012-14 and up to £40 million more in the period 2014-16. The 3MDG Fund will provide maternal and child health services for the poorest and most vulnerable. It will help to strengthen the Burmese health system and continue to work on the prevention and treatment for HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria for groups and areas not covered by Global Fund programming following its return in 2011.25 The total budget for the 3MDG Fund is predicted to be £180 million, with contributions from Australia, the EU, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway.26 | Yes. |

| Three Diseases Fund27 | £34.1 million | 2006-13 | Multi-donor trust fund managed by the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) Focussing on HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria, it was set up following the withdrawal of the Global Fund from Burma in 2005.28 It receives contributions from the EU and the governments of Australia, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and the United Kingdom. DFID provided 41% of the funds which supported the prevention, treatment and care of affected people in the most vulnerable groups. | Yes – The National Audit Office also reviewed the Three Diseases Fund support to malaria as part of its recently published malaria review.29 We met with staff from the National Audit Office undertaking the review. |

| Addressing Drug-Resistant Malaria in Burma30 | £11.3 million | 2011-14 | Accountable grant to Population Services International (an NGO) It aims to improve access to quality-assured anti-malarial drugs in the Burmese health system. | No – We did not review this in detail as the National Audit Office is reviewing it as part of its malaria study. |

| Delta Maternal Health (Joint Initiative for Improving Maternal and Child Health after Cyclone Nargis)31 | £4.95 million | 2009-13 | Multi-donor trust fund managed by UNOPS It delivers maternal and child health services to five townships in the Irrawaddy Delta which were affected by Cyclone Nargis in 2008. | Yes. |

| Primary Health Care programme in Burma32 | £3.2 million | 2006-12 | Accountable grant with Health Poverty Action (NGO) It aimed to support maternal and child health for poor minority communities in marginalised areas of Burma. In September 2012 a new programme of support for these areas had been agreed for Health Poverty Action under the new programme of support for conflict-affected people and peace building.33 | No – We did not review this as it is located on the Burma/China border and access is difficult for foreign nationals. |

| Humanitarian assistance to conflict-affected areas with health components | ||||

| Mae Tao Clinic (Health Services Programme)34 | £532,000 | 2009-12 | Accountable grant to Mae Tao Clinic It aimed to provide health care for displaced Burmese people along the Thailand–Burma border. In September 2012 a new programme of support for these areas had been agreed for Mae Tao Clinic under the new programme of support for conflict-affected people and peace building.35 | Yes. |

| Emergency Healthcare (Emergency health care project in eastern Burma)36 | £834,000 | 2011-13 | Accountable grant to Christian Aid (NGO) This is for internally displaced people, particularly women and children, living in the target conflict-affected areas in eastern Burma. It gives access to emergency health care provided by trained health personnel. Basic health interventions are provided by trained community health workers to people in very hard to reach and conflict affected areas. | Partially – We were not able to meet the intended beneficiaries as they live in areas where foreign nationals are not permitted to visit. |

| Shoklo TB (Accessible Tuberculosis Treatment)37 | £177,000 | 2009-12 | Accountable grant to Shoklo Malaria Research Unit This was to provide testing and treatment for TB and multi-drug-resistant TB. In addition, it provided treatment for those who were also HIV positive, targeted on informal migrants on the Thailand–Burma border. In September 2012 a new programme of support for these areas had been agreed for Shoklo TB under the new programme of support for conflict-affected people and peace building.38 | Yes. |

| Health services for Burmese refugees in three camps39 | £85,000 | 2010-11 | Accountable grant to Aide Medicale Internationale (NGO) It aimed to provide curative health care, disease prevention and related control systems in three camps; HIV/AIDS and TB prevention, treatment and care provided in Mae La camp. | No – We did not review this programme as the value of the grant was small. Funding finished in 2011 and it would now be difficult to assess the impact given that the grant has now expired. |

2 Findings

Objectives

Assessment: Green

2.1 This section of the report examines the design and objectives of the DFID programmes. We assess DFID’s health objectives according to their clarity, relevance and appropriateness in Burma.

DFID’s objectives are appropriate and identified from and targeted at Burma’s health needs

2.2 DFID Burma aims to design programmes that not only meet basic needs but also contribute to addressing the root causes of conflict.40 DFID Burma has three strategic objectives for health programming:

- to improve reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health and reduce the communicable disease burden;

- to maintain a special focus on the global health threat posed by drug-resistant malaria in Burma through a regional response, the 3MDG Fund and support for critical gaps in the response; and

- to address targeted humanitarian health needs of refugees and internally displaced and other conflict-affected populations where there are critical gaps in the response.41

2.3 The two main programmes by expenditure are the Three Diseases Fund and the 3MDG Fund. The Three Diseases Fund was set up in response to the withdrawal of the Global Fund. The 3MDG Fund, which is the latest, largest and most ambitious in DFID Burma’s health portfolio, is the natural successor to the Three Diseases Fund. It also combines key elements of the Delta Maternal Health programme, which grew out of the humanitarian response after Cyclone Nargis in 2008. We found that there was a clear and sensible progression from one programme to another to build towards a coherent response to priority health needs.

2.4 The other, smaller programmes in DFID’s health portfolio target specific matters focussing on one disease or a contained geographical area.

2.5 DFID’s health programme includes direct health services targeted at reducing the burden of disease. Through some of its interventions there is health education that will help reduce the incidence of disease going forward. The model of expected change is appropriate in Burma’s situation, where there is very little in the way of health education provided by the state.

2.6 From our discussions with intended beneficiaries, we found these objectives to be appropriate, effective and responsive in a country where there are significant health needs.

2.7 It is clearly not possible for DFID’s health programmes to cover all the health needs of the population. DFID has prioritised and targeted its programme in discussion with intended beneficiaries. For example, DFID’s design for the Delta Maternal Health programme built on relationships that it had established in the Irrawaddy Delta area. These were with local state officials, delivery partners and, most importantly, intended beneficiaries through its humanitarian aid response following Cyclone Nargis.

2.8 DFID Burma staff worked – and continue to work – closely and effectively with key Ministry of Health staff, including the Minister of Health. The Burmese Ministry of Health’s objectives are to enable every citizen to attain full life expectancy and enjoy longevity of life and to ensure that every citizen is free from disease.42 It plans to achieve this by disseminating health information and education widely to reach rural areas, by enhancing disease prevention activities and by providing effective treatment for prevailing diseases. We consider that DFID has successfully combined a ‘top down’ approach in working with the Ministry of Health and a bottom-up approach in identifying the needs of intended beneficiaries.

2.9 Overall, DFID’s health programme has been designed from the ‘bottom-up’, taking into account intended beneficiaries’ views and targeting their needs. It has also taken account of the health priorities that are identified by the Government of Burma’s Ministry of Health in a ‘top-down’ manner. Where these needs and priorities are in conflict, DFID has helped to manage the expectations of both groups.

2.10 Health is seen as a relatively neutral sector and DFID Burma was able to support the objectives of the Ministry of Health, whilst working outside official channels of the Government of Burma. In a period of tight sanctions, DFID could not fund the Government of Burma directly. This, however, did not preclude DFID Burma working with the Ministry of Health to help meet the health needs of the Burmese people. Excellent relationships have been developed between the Ministry of Health and DFID Burma staff. Now that sanctions are lifted, there are significant opportunities for closer co-operation with the Government of Burma.

DFID showed leadership in designing programmes targeted at health needs

DFID showed leadership in developing the Three Diseases Fund

2.11 Other donors and delivery partners state that DFID showed clear leadership and that it was key in the development and implementation of the Three Diseases Fund, which quickly filled a gap left by the withdrawal of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) in 2005. The core aim of the Three Diseases Fund was to provide a simple and transparent way to:

- finance a nationwide programme of activities in areas where the three diseases were prevalent;

- inform and educate the public on the prevention and treatment of the three diseases;

- reduce the transmission of the diseases; and

- enhance patient care and treatment through access to essential drugs and services.43

2.12 There has been general agreement from partners and the Burmese Ministry of Health that the objectives of the Three Diseases Fund were correct.

The Delta Maternal Health programme was designed to meet intended beneficiaries’ needs

2.13 Following Cyclone Nargis in May 2008, DFID Burma led the way in conducting a needs assessment in the Irrawaddy Delta, building on good relationships with the local communities, including local government officials.44 This resulted in the creation of the Delta Maternal Health programme, which aimed to improve maternal and child health in the townships most affected by Cyclone Nargis. It also aimed to increase access to quality maternal and child health services, working through township health plans. These township plans sought to address the needs of intended beneficiaries at the local level, with flexibility to be updated to reflect changing priorities.

2.14 In the Delta Maternal Health programme, DFID has used its knowledge of what intended beneficiaries need from the work it did with them following Cyclone Nargis on how best to deliver health services. It has laid the foundation for stronger state–citizen relationships and capacity-building in the future. By developing relationships at the township level, DFID Burma aims to integrate services with those provided by the regional and national authorities.

2.15 The re-entry of the Global Fund in 2011 provided more funding and resources for the diseases which the Three Diseases Fund sought to address. The return of the Global Fund meant that DFID Burma could refocus resources and concentrate on meeting its maternal health objectives. DFID Burma is also now able to expand into other health priority areas, such as improving public sector health care systems. Working with other donors, DFID has developed the 3MDG Fund to deliver these aims.

The 3MDG Fund built on previous programmes

2.16 The 3MDG Fund is the latest DFID Burma health programme with other donors. Its overarching goal is to contribute towards national progress in achieving the health MDGs. This includes support for mechanisms that enable communities and beneficiaries to engage in the design, implementation and monitoring of health services. The focus is on non-discrimination and excluded and marginalised groups, equality of access to health services and transparency of information.45 This aligns with DFID Burma’s wider objective of addressing the root causes of conflict.

2.17 The programme objectives for the 3MDG Fund are:

- to increase access to and availability of essential maternal and child health services for the poorest and most vulnerable in areas supported by the fund;

- to provide HIV, TB and malaria interventions for populations and areas not readily covered by the Global Fund; and

- to help Burma’s Ministry of Health provide more equitable, affordable and quality health services that are responsive to the needs of the country’s most vulnerable populations.

2.18 We assess that all the objectives of the 3MDG Fund have been correctly identified as current health priorities. There is also a good fit with DFID Burma’s overall strategic objectives for health.

2.19 At the time of our review, however, the 3MDG Fund was still in the process of being designed. Much remains to be done. Progress so far shows that the design of the fund incorporates features that have worked well from the Three Diseases Fund and the Delta Maternal Health programme.

2.20 There are, however, a number of significant issues outstanding on the 3MDG Fund. These are being addressed by consultants employed by the fund but have required considerable support from DFID and other donors, including technical support from DFID. Outstanding issues include finance arrangements, monitoring and evaluation and the development of value-for-money indicators. More work remains to be done in approving and agreeing work plans.

2.21 We assess that there is a risk that the 3MDG programme may be too narrowly focussed, with the bulk of the thinking to date being targeted at maternal and child health services to the detriment of other health priority areas.

DFID also funds smaller programmes that focus on specific health needs

2.22 The two programmes which serve refugees and displaced people in Thailand (Mae Tao Clinic and Shoklo TB) were more traditional in their design. These programmes are significantly smaller in value than the other programmes. They took the form of bilateral grants to organisations that rely on funding from donors such as DFID. The objectives of these programmes align with DFID Burma’s objective of supporting refugees and displaced people.

2.23 The remaining project, Emergency Healthcare, is more innovative in its design. It delivers health care in hard-to-reach and conflict-affected areas along the Thailand–Burma border. The project is designed to deliver services to communities which currently receive little or no health care. DFID acknowledges that this programme is not sustainable due to the transportation methods and cost in the long term, although it helps to meet needs in the short term.

DFID’s work has complemented the efforts of other aid donors

2.24 DFID’s engagement in health in Burma since 2006 has mainly been through UN-administered funds, such as the Three Diseases Fund, the Delta Maternal Health programme and, more recently, the 3MDG Fund. DFID has harmonised the objectives across donors and improved communication amongst implementation partners.

2.25 DFID has been instrumental in securing the inclusion of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) as a board member in the 3MDG Fund. DFID has acted as an influential member of the boards of both the Three Diseases Fund and Delta Maternal Health. For a long time, DFID was the only major donor with a health adviser in-country, enabling it to take the lead in co-ordinating, advising and learning for other donors. DFID continues to be well respected for the role it has played and the introduction of health advisers from other donors has helped to strengthen the support it can provide.

Delivery

Assessment: Green

2.26 This section examines the delivery of DFID’s health programme in Burma. We assess whether the delivery mechanisms have been right for Burma and whether DFID has ensured appropriate oversight of the health programme. Figure 5 on page 11 shows the chain of partners (delivery chains) between DFID and the intended beneficiaries for each project under review. We also consider how well DFID has managed political and conflict issues and how DFID’s health programme can adapt in a period of rapid change in Burma.

DFID’s aid delivery mechanisms have been right for Burma

DFID uses an appropriate variety of delivery mechanisms

2.27 The options for aid delivery have been restricted by the EU’s Council Decision on Burma, which until recently had ruled out operations through the Government of Burma. Although this restriction has recently been lifted, we found that the public sector finance system in Burma remains fundamentally weak. This means that it may still be some time before money can be channelled directly to the Government of Burma.

2.28 Smaller value health programmes have used an appropriate variety of NGOs through bilateral contracts. A fund manager has been used for the larger programmes where multiple donors, including DFID, are involved.

UNOPS is integral in delivering DFID’s health programme

2.29 DFID has used UNOPS as a fund manager for a significant proportion (88%) of its health programme. The decision to operate the Three Diseases Fund in a similar manner to the Global Fund and use an independent fund manager to manage the Three Diseases Fund was sound. No donors had the capacity or experience to take on this role.

2.30 Multi-donor funds often require an independent fund manager, particularly when the fund covers a wide geographical area and includes a high number of donors, as did the Three Diseases Fund. A fund manager contracts with NGOs and UN institutions to provide aid in a specific geographical area. The fund manager disburses the money to the contracted organisation and monitors and evaluates programme delivery.

2.31 UNOPS was selected as the fund manager for the Three Diseases Fund. The choice of fund manager was limited. The Government of Burma’s restrictions on operations and the importation of drugs and supplies supported the case for a UN trust fund. As fund manager, UNOPS operates in Yangon to disburse grants and monitor funded activities implemented by NGOs and UN agencies.

2.32 The Three Diseases Fund contained a degree of risk as neither the donors nor the fund manager (UNOPS) had previously undertaken a project of this nature and size in Burma. The final evaluation of the Three Diseases Fund identified that the fund operated on a mainly reactive basis. The evaluation considered that the Three Diseases Fund Board and UNOPS should have been more proactive and used their influential position to increase effectiveness.46

2.33 UNOPS was appointed fund manager for Delta Maternal Health and, following a competitive selection process, was selected as fund manager for the 3MDG Fund. UNOPS is addressing the areas for improvement identified in the final evaluation of the Three Diseases Fund. DFID, with other donors through the 3MDG Fund board, is supporting these changes and monitoring the progress being made.

2.34 We consider that UNOPS has a number of strengths that support its appointment as fund manager. These include that it:

- works well with donors;

- works well with the NGO community; and

- has experience and knowledge of Burma.

2.35 We did, however, find that the 3MDG Fund has taken time to be established and UNOPS in the past has been slow to adapt to new circumstances. For example, we consider that the UNOPS reimbursement procedures to delivery partners for the Three Diseases Fund were slow and took some time to be changed.

![[Diagram showing delivery chains from DFID to intended beneficiaries for different projects]](https://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/Screenshot-2025-03-31-at-16.21.21-300x129.png)

DFID has used appropriate implementing partners and processes have improved

2.36 For the Three Diseases Fund and Delta Maternal Health programme, DFID and UNOPS undertook a rigorous process of review to select delivery partners; this included due diligence and detailed assessment. For bilateral programmes, such as Mae Tao Clinic and Shoklo TB, DFID is able to communicate and work directly with the implementing partner to design the delivery channels and address any concerns that arise. DFID’s relationship with UNOPS has matured over the lifespan of the programmes and they now work closely together on the management of implementing partners.

2.37 The evolution of the Three Diseases Fund illustrates how the relationship with delivery partners has improved. Initially, delivery partners were invited to express interest in securing support for programmes and activities that could be started immediately. On this basis, they submitted three-year work plans and budgets. The fund manager committed only to the first year of funding with allocations for subsequent years to be determined by performance against certain criteria. Delivery partners did not know whether they would receive continued funding, were uncertain how their performance was being measured and were confused about timescales for decisions on future funding.

2.38 The system was challenged by delivery partners and by the Three Diseases Fund Board and was subsequently amended to provide multi-annual grant allocations. Improvements were also made to performance assessment processes, with increased transparency through feedback sessions between UNOPS and the delivery partners. The time taken, however, to resolve the issue and the extensive discussions involved between the Fund Board and UNOPS were concerns identified in the mid-term evaluation of the fund.47 These matters have been addressed and lessons were implemented for the Delta Maternal Health programme.

Evidence on cost-effectiveness is mixed and not always robust

2.39 UNOPS receives a management fee for its role as fund manager. This fee is approved by the Fund Board. Under this agreement UNOPS is able to deduct a maximum of 7% of the funds paid to delivery partners as an administrative fee. The percentage of administrative fee depends on the level of services that UNOPS provides to the delivery partner. If UNOPS is providing no services the funds are passed directly to the delivery partner with a 1% deduction made by UNOPS. This allows the delivery partner to potentially use up to a maximum 6% of the funds received to cover administrative costs. Some NGOs, for example the Asian Harm Reduction Network, choose not to make an administrative cost deduction and apply all funds received to benefit intended beneficiaries. The overall sum of administrative or overhead charges cannot exceed 7% of the total funds.

2.40 From our review of a sample of delivery partners’ financial statements, we found that expenditure which we would classify as overhead and administrative costs amounted to considerably more than the 7% ceiling. This, we consider, is due to a lack of a clear definition of what constitutes administrative or overhead costs, both for UNOPS and for delivery partners. We do not believe it is due to inaccurate accounting or inefficient and costly levels of administration. We also consider that, while the costs are higher, the charge made for administrative costs by UNOPS and delivery partners did not exceed the 7% ceiling.

2.41 A recent joint study by DFID Burma and other donors of the Delta Maternal Health programme initially found that using international NGOs to manage on-the-ground operations was not cost-effective48 when compared to World Health Organization benchmarks. The study notes that this was largely attributable to start-up costs and the extra cost of providing services to poor populations in hard-to-reach areas.49 In view of the fact that the Delta Maternal Health programme’s approach is to be replicated by the 3MDG Fund, it is important that action is taken to monitor value for money of future implementing partners.

2.42 The number of delivery partners involved in the 3MDG Fund is likely to increase, possibly to well over the 34 partners funded under the 3DF. It is important that DFID and UNOPS, as the fund manager, have a strong understanding of costs in the delivery chain and, in particular, of overhead costs. An opportunity exists for DFID to secure efficiencies in the delivery chain so that savings can be directed to meeting further the needs of intended beneficiaries.

2.43 A cost-effectiveness review50 of the Three Diseases Fund used a mix of actual cost data from implementing partners51 (for HIV/AIDS), national average data (for TB) and international averages (for malaria). This was combined with assumptions about the typical effectiveness of Three Diseases Fund-supported interventions. It concluded that, overall, the HIV/AIDs and TB interventions were very cost effective, while the data for malaria were too poor to report robust results. We concur with these conclusions and we positively note that the exercise was commissioned by the donors as this is often not common enough in final evaluations. This confirms the need and the demand for similar work in the future, which is being integrated into the design of the 3MDG Fund.

DFID has ensured appropriate oversight of the health programme

2.44 DFID’s health programme demonstrates sound financial management and good governance in a country where there is a high perceived risk of corruption. DFID Burma has been firm in its approach to ensure that funds disbursed are appropriately accounted for and that safeguards are in place to prevent and detect fraud and corruption.

2.45 There is a general view from NGOs that this approach and, in particular, the programme of audit and review is over-burdensome. Given the current context and operating environment of Burma, however, it is in our view both right and appropriate that DFID requires this level of review and audit.

2.46 Detailed audit and regular monitoring take place for health programmes that are funded through bilateral contracts. DFID Burma staff undertake and document these reviews personally. For areas where travel restrictions for foreign nationals are in place, DFID uses Burmese nationals to carry out the review. We were told by NGOs that DFID’s monitoring programme is ‘tough but fair’. Our review of a sample of monitoring reports found that they were appropriately rigorous and detailed. In some cases, the findings in these monitoring reviews led to the suspension of programmes or a change in the location of health service delivery. NGOs were consulted and allowed to comment on draft reports before they were finalised.

2.47 There is also a comprehensive programme of audit and regular monitoring for health programmes where multilateral funds are employed. The first layer of this is undertaken by UNOPS as fund manager. This is supplemented by DFID, which carries out its own programme of reviews. This helps to provide a reality check on UNOPS’ monitoring and helps DFID to monitor UNOPS’ own performance. One consequence of this programme of audit and monitoring is that it has helped to improve the systems of financial accountability of local NGOs. Examples of these are the Myanmar Medical Association and the Myanmar Anti-Narcotics Association. Along with the other donors for the managed funds, DFID should be given credit for insisting that a robust monitoring and audit programme is in place.

2.48 DFID Burma has recently published an anti-corruption strategy.52 Although the strategy is new, DFID has considered many of the aspects of this strategy in its monitoring of NGOs. The anti-corruption strategy is appropriate for the Burmese context and considers the fiduciary risks for implementing partners. The strategy has meant DFID Burma’s approach has not had to change but it has helped to formalise current working practices.

2.49 DFID Burma has developed good risk management arrangements. For the health programmes managed by UNOPS as the fund manager, risk registers have been established. These are regularly reviewed, updated and include the views of donors. For the bilateral programmes, DFID considers the key risks as part of its monitoring processes.

DFID has managed political and conflict issues well

2.50 Burma is a challenging environment in which to deliver aid. The political situation, conflict and ceasefire issues have placed restrictions on how DFID Burma can operate. DFID’s health team is highly respected by Burma’s Ministry of Health, other donors and NGOs. DFID’s technical expertise and the high quality of its people are commonly cited. DFID Burma has worked effectively with the Ministry of Health, even during the period of EU sanctions which places DFID in an excellent position to continue to support the Ministry.

2.51 DFID’s health programme in Burma has aimed to deliver aid in conflict-affected and ceasefire areas. Through its delivery partners, it has helped to deliver health services to displaced people in northern Thailand and to people in conflict zones and ceasefire border areas. For example, the Emergency Healthcare project has helped to deliver health care to people where there is little or no state health provision.

2.52 There is now the opportunity to deliver aid in other conflict-affected and ceasefire zones through the 3MDG Fund. The provisional list of townships to benefit from the 3MDG Fund includes townships in ceasefire zones.

DFID needs to ensure that delivery of its health aid in Burma can adapt to significant change

2.53 The Government of Burma is becoming more receptive to change. Political reforms and the changing views of the international community mean that it is likely that more aid will come into Burma. While this increased aid will be welcomed in a country that has significant needs, it is unknown what proportion of this aid will be directed to the health sector.

2.54 It is estimated that up to 85% of total health care expenditure in Burma is paid by service users and a significant amount is provided through the informal and for-profit sectors. Using its highly respected position, DFID should engage further with the Government of Burma and other donors on how to manage and improve the informal and for-profit health sectors in Burma. Two examples of where DFID could be involved are to help the Government of Burma to ensure that:

- drugs delivered outside the public health care system are quality assured and prescribed correctly; and

- the quality of work of doctors is adequately monitored.

Impact

Assessment: Green

2.55 This section examines the impact of DFID’s contributions to the Three Diseases Fund, the Delta Maternal Health programme and the Thailand–Burma border programmes (Emergency Healthcare, Shoklo TB and Mae Tao Clinic programmes). There has, as yet, been little new spend under the 3MDG Fund so there is no impact to assess. Instead, we appraise the 3MDG Fund’s plans and prospects.

Overview

2.56 DFID support has been in the context of a general long-term improvement in most of the relevant health indicators in Burma, due to general economic growth, vigorous for-profit and traditional health sectors and established (though under-funded) national communicable disease programmes. Definitive attribution of improved health outcomes is not possible. We therefore judge DFID’s performance on the basis of the targets they have selected and the extent to which they have been achieved. Figure 6 on page 16 summarises the main programmes’ key results.

Impact of the Three Diseases Fund

2.57 The Three Diseases Fund has clearly made an important contribution during its five years of operation. On the whole, results improved year on year and targets were achieved (even overachieved in several instances). The final evaluation of the Three Diseases Fund estimates that, with £28 million spent directly on HIV/AIDS,53 £15 million on malaria and £9 million on TB, the fund has contributed, on average, half of all identified external funding for each of the three diseases during 2007-11. It is responsible for achieving between one and two thirds of national programme targets.54

2.58 There is probably, however, an overestimate of impact, particularly in TB and malaria, where it is known that informal and for-profit health providers are commonly used for diagnosis and treatment.55 The Three Diseases Fund evaluation itself acknowledges that not all official funding sources have been identified.56 It was also unable to show that it could isolate the trust fund component of implementing partners’ total resources.

2.59 Although programme targets were frequently achieved, they tended to be set according to the availability of funding57 rather than to drive the desired levels of coverage. The Three Diseases Fund’s ability to reach the most affected districts and to maximise coverage and cost-effectiveness were compromised by:

- the geographical restrictions on the operation of international NGOs;

- the limited capacity of the local NGOs; and

- the absence of ongoing quality assessments (and subsequent standardisation) of programme-funded services,58 which may have further limited overall cost-effectiveness.

2.60 The evidence of impact from our meetings with intravenous drug users receiving assistance from the Three Diseases Fund was, however, very positive. As well as seeing to the medical needs of this group of users, the programme provided counselling, support and education to them, their family members and friends. They told us that the key benefit is that it has helped to reduce some of the social stigma of HIV/AIDs in their communities. This made sufferers more able to retain their self-esteem, more likely to stay with their families and in employment and more likely to seek treatment.59 No support of this type is provided by the state health system.

HIV/AIDS

2.61 The national HIV/AIDS epidemic is small, currently affecting only 0.6% of the total population. General prevalence had already started to decline in 2004,60 before the start of DFID support in this area.

2.62 High-risk sub-groups are, however, much more seriously affected and it is these high-risk groups that were the target for the Three Diseases Fund, consistent with the priority of Burma’s first National Strategic Plan for HIV/AIDS.61 The prevalence of HIV/AIDS is most recently estimated at 9% amongst female sex workers (FSW), 8% amongst men who have sex with men (MSM) and 22% amongst intravenous drug users.62

| 1. Three Diseases Fund | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose: To reduce transmission and enhance provision of treatment and care for HIV/AIDS, TB and malaria for the most in need populations | |||

| Indicator | Target | Result | Conclusion |

| Number of persons at high risk accessing voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) | Targets for 2010: 4,730 sex workers 2,560 men who have sex with men (MSM) 2,957 intravenous drug users (IDUs) | Achieved for 2010: 7,593 Sex workers 4,358 MSM 3,753 IDUs All targets exceeded for 2010. October 2012 final evaluation reported targets for 2011 also met. | Targets achieved for all at-risk population groups |

| Number of people in need of treatment receiving anti-retroviral treatment (ART) | 14,856 by 2010 | In 2010, 15,898 people received ART. October 2012 final evaluation reported 22,000 people were receiving ART through 3DF-supported services.67 | Target achieved (although absolute number amounts to 20-25% coverage, which is low by international standards)68 |

| Percent of adults and children known to be alive and on treatment 12 months after initiation of antiretroviral therapy | 85% by 2010 | All implementing partners achieved the threshold target of a minimum 85% survival rate 12 months after initiation of ART. | Target achieved |

| Percentage of known HIV-infected pregnant women who received ART | 71% by 2011 | In 2011, 54% of mother and baby pairs received a course of ART of an estimated 3,536 pregnant women in need. | Target not achieved |

| TB case detection rate, by sex | 75% by 2011 | TB case detection rate was considered to be good (range 87%-94%)69 until new 2010 national TB prevalence survey. Applying new (higher) prevalence rates, the national TB programme detects 65% of all cases. | Target achieved (in light of recent significant upward revision in prevalence estimates; TB case detection rate targets are now under review) |

| Percentage of households in project area that have at least one bed net | 5% | 12% | Target achieved (although questions raised over how this indicator is measured and we are concerned that this is a relatively low target) |

| 2. Delta Maternal Health Programme | |||

| Purpose: To increase access to essential maternal and child health services, particularly in hard-to-reach areas in the cyclone-affected Irrawaddy region | |||

| Indicator | Target | Result | Conclusion |

| Percentage of pregnant women who receive antenatal care one or more times | 82-87% (varies by township) by 2012 | 89-95% | Target achieved (for reporting townships only)70 |

| Number of referrals for emergency care during pregnancy | 2,246 by 2012 | 3,113 | Target achieved |

| Percentage of one year olds vaccinated against: (i) measles and (ii) Diphtheria, Pertussis and Tetanus (DPT3) | 88% for measles; 91% for DPT3 | 91% for measles; 94% for DPT3 by 2011 | Target achieved |

| 3. Health Programmes on Burma/Thailand border (includes Mae Tao Clinic, Shoklo TB and Emergency Healthcare) | |||

| Purpose: To provide humanitarian assistance to displaced people and people in conflict-affected areas | |||

| Indicator | Target | Result | Conclusion |

| Improve the quality of life and reduce the vulnerability of refugees and displaced persons along Burma's border | Under-five mortality rate in Burmese refugee camps in Thailand Annual target: less than 8 in 1,000 | Under-five mortality rate in 2010 was 4.2 per 1,000 in all camps (2009: 6.1 per 1000, 2008: 5.8 per 1000, 2007: 4.7 per 1000). This shows a return to the downward trend from 7.2 in 2003. The data also continued to compare favourably to rates for the population of Thailand (8 per 1,000) in 2010. | Target achieved |

| Number of new/improved sanitation facilities provided | 4,000 | 4,144 had been provided in 158 villages by the end of 2010. | Target achieved |

| Meet more of the basic humanitarian needs of Burmese refugees and displaced persons in conflict-affected border areas in Burma | Crude mortality rate in refugee camps. Annual target: less than 8 in 1,000 | Crude mortality rate was 3/1,000 in 2010, continuing decreases (2009: 3.8; 2008: 3.3; 2007: 3.5; 2006: 3.6; 2005: 3.9; 2004: 4.1; 2003: 4.2). Since 2003 the rates have been maintained below the average for the East and Pacific Region. In addition, the rate in all camps compared favourably to rates for the population of Thailand at 9/1,000 population. | Target achieved |

| Number of people in communities affected by conflict and displacement benefiting from needs-based humanitarian relief | 70,000 through village-based community support by 2010 70,000 per year through cash support | In 2009 and 2010 local partners reached 61,930 people in 133 conflict-affected communities with community-based humanitarian aid. On top of the baseline of 14,012 from 2008, this brings the total beneficiaries to 75,942.people in 158 villages. | Target achieved |

2.63 Over the Three Diseases Fund period 2007-11, 30,000 FSW, 16,000 MSM and 13,000 people who inject drugs are reported to have been reached with counselling, testing, condoms and behaviour change advice.63 Estimating how this coverage relates to total populations is naturally difficult. The final evaluation, drawing on advice from the in-country HIV Technical and Strategy Group (which uses local knowledge and rules of thumb to estimate the absolute numbers of people in each group for the regular Asian Epidemiological Model updates),64 concluded that the coverage of FSW achieved by the Three Diseases Fund was above 60%,65 of MSM ‘far from 60%’. The coverage of intravenous drug users was estimated to be a low 20%.

TB

2.64 Burma has been identified by the World Health Organization71 as one of 22 global ‘high-burden’ TB countries, with an estimated 23,000 deaths and 180,000 new cases per year.72 In addition, multi-drug resistant TB in Burma has been on a steady increase since at least 1995.73 A survey in 201074 found that TB prevalence may be two to three times higher than previously thought. The general picture, as shown in Figure 7, however, is of a disease being contained by a longstanding national programme.75 There is now more extensive diagnosis and notification of the disease and, as shown in Figure 8, a decline in mortality rates, though at a slower rate in recent years.

2.65 The Three Diseases Fund is reported to have been responsible for identifying around 42,000 new TB cases per year since 2008, around 20% of all new cases in Burma.76,77 Treatment success has been observed at above the 85% global minimum target.78

![[Chart showing incidence and notifications of TB from 1990-2011]](https://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/Screenshot-2025-03-31-at-16.50.12-300x152.png)

![[Chart showing annual deaths from TB from 1990-2010]](https://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/Screenshot-2025-03-31-at-16.51.41-300x203.png)

Malaria (The Three Diseases Fund)

2.66 Burma accounted for the majority of malaria cases in the region:83 it accounts for 80% of all cases and 75% of deaths.84 It is endemic in 80% of the townships in Burma (where 70% of the population lives). After good progress during the past 20 years in reducing deaths and illness from the disease (see Figure 9 on page 19), it is suggested that malaria is re-emerging as a public health problem. We understand that this is due to high internal migration and the emergence of drug-resistant strains.85

2.67 The Three Diseases Fund reports that it has provided 680,000 bed nets86 to protect against malaria since 2007. It has doubled its distribution of rapid diagnostic test kits from 350,000 per year in 2008 to over 700,000 per year in 2010 and 2011.87 Cases treated ‘with support of the Three Diseases Fund’ have averaged 450,000 per year since 2008, possibly 10% of the estimated annual total of new cases.88 This represents a low level of coverage.

![[Chart showing confirmed cases, admissions and deaths from Malaria from 2000-2011]](https://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/Screenshot-2025-03-31-at-16.53.05-300x136.png)

Comparison of HIV/AIDS programmes in Burma and Cambodia

2.68 As a further check on how we should judge the Three Diseases Fund outcomes, we took the example of HIV/AIDS (the disease with the best globally comparative data) and looked at results in Cambodia. This is a significantly smaller country but with similar political history and a similar type of epidemic. Burma, with one fifth of the health expenditure per head, is achieving similar or better outreach to high-risk groups but there is significantly less provision of anti-retroviral treatment (ART)89 (see Figure 10). Reaching high-risk groups with prevention interventions is the relatively easy part of an HIV/AIDS campaign. Given its lower budget, Burma appears to have performed well in comparison to Cambodia.

| Indicator | Burma | Cambodia |

|---|---|---|

| HIV prevalence | 0.6% | 0.6% |

| People living with HIV | 220,000 | 64,000 |

| Total expenditure on HIV (millions, 2009)90 | £22.0 | £34.4 |

| Expenditure per adult with HIV91 | £100 | £540 |

| Estimated ART coverage92 | 32% | >95% |

| Percentage of people who inject drugs that have received an HIV test in the past 12 months and know their results | 27% | 35% |

| Percentage of men who have sex with men reached with HIV prevention programmes | 70% | 69% |

| Percentage of sex workers reached with HIV prevention programmes | 76% | not available |

Source: UNAIDS Global Report 201293

Reaching those most in need

2.69 Those most in need in terms of health risks have been reached with good effect, especially in HIV/AIDS (see Figure 10). It is difficult, however, to judge the extent to which the poorest or excluded groups have been reached, since there has been little socio-economic or gender monitoring. We can say, however, that a good geographic distribution across the country appears to have been achieved. Also, it is plausible to assume, from meeting intended beneficiaries (for HIV/AIDS), that the target groups of sex workers and intravenous drug users tend to be from lower-income and social groups.

Impact of the Delta Maternal Health programme

Overview

2.70 The programme appears to have made valuable contributions to maternal and child health services in the region. The absence of a programme-specific baseline means that conclusions must be tentative. A recent end-of-programme review,94 however, found independent evidence of improving service levels combined with high achievement of programme targets for vaccinations, antenatal care and regular outreach to hard-to-reach villages. It also found that the costs of doing so were high, though this could be largely attributable to the difficult geography of the Delta. In addition to service improvements, the programme is making valuable first steps to build, from a very low base, the capacity of the township health authorities.

2.71 The evidence from our field visits to the Irrawaddy Delta supports the view of positive impact. We heard first-hand accounts of greater access to health services, better quality services and help with costs (in the case of pregnant women needing hospitalisation). We also heard convincing reports from volunteer health workers who now, for instance, feel more motivated and no longer have to pay for transport costs out of their own funds.

Maternal Health results

2.72 The Delta Maternal Health programme aimed to target the main causes of maternal deaths. It did this through simple interventions such as shared knowledge on pregnancy danger signs, having a prepared delivery plan and increased access to emergency obstetric care. By mid 2012, in a target area of 2,500 villages,95 the programme had helped to ensure that 62% of villages had a trained health worker and 32% had an auxiliary midwife. The programme prioritised hard-to-reach villages when deploying newly trained staff and by 2012 these villages achieved significantly higher coverage, at 79% and 52% respectively. While this is a justification for a potentially higher cost, there is no programme-specific baseline with which rigorously to assess impact. In the absence of other major support to maternal health in the area, however, it is plausible to attribute at least some part of the improved indicators for the targeted hard-to-reach villages to the Delta programme.

2.73 National maternal health indicators have been improving steadily over the past twenty years (see Figure 11 on page 21). Maternal deaths due to abortions and the continued preference for traditional birth attendance are, however, still high. It is estimated that 2,400 pregnant women die every year. The end-of-programme review96 found that targets for improved childbirth care were difficult to achieve. This is not uncommon. Maternal health programmes often encounter difficulty in changing preferences for place of childbirth and resolving access problems, due to the unpredictable timing of labour. The 3,000 emergency referrals supported by the programme in 201197 are, therefore, noteworthy.

2.74 Malnutrition, a major cause of child deaths, was added to the programme’s objectives in 2011 but little progress appears to have been made so far. We were told this was due to the difficulty in identifying appropriate interventions, although we saw little evidence that this had been attempted.98 Addressing malnutrition is often a relatively simple intervention but we found that technical difficulties – and the challenge to educate mothers – prevented such rapid progress by the Delta Maternal Health programme.

Reaching the most in need

2.75 The Delta Maternal Health programme explicitly targeted geographically hard-to-reach villages in the Irrawaddy Delta area. Although there are no specific social monitoring results, remoteness is known to be generally correlated with exclusion.

![[Chart showing maternal death rates from 1990-2015]](https://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/Screenshot-2025-03-31-at-16.55.37-300x174.png)

Source: Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group, 2012100

Thailand–Burma border programmes

2.76 The Thailand–Burma border programmes had less data and no end of programme evaluations have been conducted to date in order to demonstrate impact. We found, however, that they provided services to populations living in conflict-affected areas with severe health needs that are not met by the Government of Burma or other providers. Programme management processes were good. These included the identification of target villages using set criteria and critical health indicators, such as limited or no access to health services and the incidence of malaria. Communities are participating in project activities, such as the construction and maintenance of water and sanitation facilities, contributing to ownership and lower programme costs.

2.77 There is a variety of faith-based and other NGO health programmes along the Thailand–Burma border. With the ceasefire and changes in official attitudes, they are now seeking to start a process of ‘convergence’. This would bring together all those involved in health services on both sides of the border to find a common way forward in meeting the basic health needs of the most marginalised. This is potentially the groundwork for a uniquely effective health service in remote areas for people who, around the world, tend to be left behind in the provision of basic services.

2.78 The service users that we met in northern Thailand that are resident in the displaced people’s camps were positive about the services provided in the clinics. They felt that the health services provided to them were ‘better’ than those provided in Burma.

Other impacts

2.79 The Three Diseases Fund has been a major vehicle for provision of aid to Burma. We found a strong consensus that both it and the Delta Maternal Health programme have positively influenced the operating environment for health donors in the country. These programmes allowed donors to share the high political risk of providing aid to Burma at the time. Aid interventions were harmonised and allowed the Global Fund to make a rapid return to the country (with £74 million of new aid money now approved) as soon as the time was right.101 Staying engaged in the country through the Three Diseases Fund has enabled early action to be taken on the containment of drug resistance in both malaria and TB.

Prospects for sustainability

2.80 The emergency and humanitarian nature of aid to Burma in recent years and the difficult political context in which aid has been delivered have so far precluded meaningful consideration of sustainability. The situation is, however, rapidly changing. More aid is already being committed and the Government of Burma is both increasing its own funding of the health sector and setting itself more targets to deliver results.102 DFID’s leadership has helped to lay the foundations for the structures, relationships and programmes that will channel potentially significant amounts of new aid into securing and extending the results already achieved. The component of the 3MDG Fund that strengthens the health sector will enable donors to engage with the Government of Burma on financing and sustainability issues. The 3MDG Fund has the potential to link into important initiatives on wider public expenditure reform. DFID is well placed, as a key participant in both, to ensure this happens.

Learning

Assessment: Green-Amber

Data challenges have hampered impact monitoring and lesson learning

2.81 There has been no national census since 1983103 and few of the usual donor-sponsored surveys (such as the five-yearly Demographic and Health Survey104) upon which donors rely for baseline information and to validate their other data. Burma therefore suffers from a more acute lack of data than many other developing countries. In addition, Burma’s national ethical committees must approve all health studies and surveys; this can be a lengthy process taking over a year.

2.82 The situation is improving rapidly. The Ministry of Health is becoming more enthusiastic about data-driven analysis. New health programmes need to be ready to meet this new demand. Past programmes have had good financial analysis but less ongoing technical health data monitoring than we would expect to see. This may be partly because, until now, the humanitarian focus of aid does not tend to prioritise establishing baselines and implementing partners often lack the capacity to monitor results effectively. We consider, however, that both the Three Diseases Fund and the Delta Maternal Health programme should have done more to standardise definitions of the service delivery they supported. They should have monitored against these definitions and analysed the results.

2.83 Work is being undertaken on the 3MDG Fund to try to address the issue of standardising definitions of service delivery. This work is in the development stage and much still needs to be done.

Project plans are complex and difficult to monitor

2.84 All programmes have project plans (‘logframes’) with milestones and indicators. These, however, often do not capture DFID’s important influencing and sector development activities. This is at a time when the basic building blocks of a public health system still have to be established and aid relations still have to be normalised. Measurable health outcomes must remain paramount but more effort should be put into defining and recording key intermediate activities.

2.85 We found that programme logframes are too long and challenging to monitor effectively. The Delta Maternal Health programme has over 30 indicators, while the current draft of the 3MDG logframe has 40. There is a need for fewer, key indicators more directly linked to interventions which can be prioritised for a more intense monitoring effort.

Evaluations have generated lessons learned

2.86 Final evaluations of the Three Diseases Fund and the Delta Maternal Health programme have been undertaken and their findings are feeding into the ongoing design of the 3MDG Fund. Both evaluations have included cost-effectiveness assessments which, although lacking good data, have generated some useful findings for programme management. They have indicated, for example, areas where costs appear to be high or where activities appear to be particularly fruitful. This has prompted a level of interest and debate which bodes well for the future. The recent return to Burma of traditionally analytically strong donors, such as USAID and the World Bank, adds to our confidence in this regard.

2.87 A 2009 mid-term evaluation105 of the Three Diseases Fund highlighted issues around the division of roles and responsibilities between the Fund Board (made up of the donors) and the Fund Manager (UNOPS). This led to a revision of the governance arrangements for the new 3MDG Fund and the inclusion of a new Technical Support Facility to allow UNOPS to draw on additional technical expertise as needed. Beyond this, we have not seen any more recent evaluation of donors’ performance management of the Three Diseases Fund. Neither have we seen consideration of management options for the future (such as performance clauses or contract breaks) of UNOPS as the fund manager of the 3MDG Fund. This is an important omission.

Changes in key personnel and succession planning

2.88 The DFID Burma health programme has benefited from staff being in post for an extended period of time. A key feature, which in our view has contributed to the overall success of the Burma health programme, has been the good relationships amongst DFID staff, Ministry of Health officials, other donors, UNOPS and delivery partners. The feedback from this group is highly positive and DFID is considered to be a trusted friend. This is particularly worthy of note when considering the difficult political and operating environment that has been in place in recent years.

2.89 Maintaining excellent relationships is critical to the success of any enterprise. The EU Council Decision is suspended and the lifting of sanctions is likely to occur this year. This puts DFID in an excellent position to use these relationships to the benefit of intended beneficiaries and improve the impact of its health programme.

2.90 There is, however, a significant risk to this opportunity as a number of key staff are leaving their posts. The Head of the DFID Burma office and the Lead Adviser for health are both due to leave later this year. Similarly, the British Ambassador to Burma, who has worked closely with the DFID Burma staff, is also leaving at around the same time.

2.91 A replacement for the Head of the DFID Burma country office has been identified and shadow working has already commenced to try to achieve a smooth transition. At the time of our fieldwork in Burma and Thailand, the replacement Lead Adviser for health was still to be identified.

2.92 There is a risk that these changes could have an unintended adverse impact on relationships, particularly at a time of rapid change in Burma. The potential loss of corporate memory presents another major risk. It is very important that the impact of these changes is minimised, including by appropriate timing of staff transfers and preparation of robust handover plans.

3 Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

3.1 DFID has played a very positive role in supporting health in Burma. In a country where it is difficult to deliver aid, due to sanctions, conflict and restrictions in movement for foreign nationals, DFID has developed a programme that is well suited to this environment.

3.2 DFID’s health programme in Burma has shown that it is possible to deliver aid effectively in conflict-affected and ceasefire areas. DFID has targeted these areas in line with its objectives. Through its delivery partners, it has helped to deliver health services to displaced people in northern Thailand and to people in conflict zones and ceasefire border areas.

3.3 Several factors appear to have been critical to this success. The strong leadership and technical expertise of DFID Burma staff and, in particular, the health team, have helped to build good relationships with Burma’s Ministry of Health, other donors and delivery partners. DFID has successfully combined a ‘top down’ approach in working with the Ministry of Health and a bottom-up approach in identifying the needs of intended beneficiaries.

3.4 In addition, DFID has employed a range of mechanisms to deliver its health aid programme in Burma. It has invested significant time and resources in developing relationships with its delivery partners. It has also established a robust programme of audit and review to ensure that these programmes are delivering. This diversification not only showed a good awareness of Burma but also a good understanding of the population’s health needs and how best to meet them.

3.5 Overall, our view is that the health programme has worked well. In a difficult context and environment, DFID has made the most of opportunities and circumstances that have arisen. There is a clear and rational progression from the Three Diseases Fund and the Delta Maternal Health programme to the 3MDG Fund. This has seen a more varied range of health care interventions, a broader geographical spread and a greater provision in a country with significant health needs. This has been achieved in partnership with the Government of Burma, other donors, delivery partners and, most importantly, the intended beneficiaries.

3.6 In addition, the programme of bilateral health projects is clearly in line with DFID’s objectives. This has targeted specific health issues, displaced people and those in conflict and ceasefire zones.

3.7 The key strength of the health programme in Burma has been the high quality of the DFID staff. The country and health teams have benefited from having some staff that have been in Burma for an extended period of time. This continuity has helped to foster good relationships with the Ministry of Health, other donors and delivery partners. The feedback on the quality of DFID staff from these groups has been consistently high.

Recommendations

3.8 The lifting of sanctions and a changing political environment presents significant opportunities for DFID Burma to have more impact in addressing the health needs of the Burmese people. We do, however, have some concerns about how DFID’s programme needs to develop to respond to these economic and political changes in Burma. DFID, through its good relationships with the Ministry of Health and other donors, has the opportunity to engage further on how to manage and improve the informal and for-profit health sectors in Burma. This is particularly important given that it is estimated that a significant proportion of the health care in Burma is provided outside the public health care system. Two areas that we consider DFID could help the Government of Burma is in:

- drugs delivered outside the public health care system being quality assured and prescribed correctly; and

- the quality of work of doctors being adequately monitored.

Recommendation 1: DFID should leverage its relationship with the Ministry of Health and its experience in Burma to date to focus the in-flows of health aid and accelerate the building of a more robust health system, including better integration of the for-profit sector.

3.9 It has been difficult to assess the impact that DFID’s health programmes have had. This has mainly been because of the lack of reliable baseline data. We recognise that this is, in part, due to the restrictions placed on what data can be collected and the lack of adequate state-collected public health data. Our interviews with intended beneficiaries, however, did identify the positive impact that the DFID Burma health programme was having on their health needs. For the future, the health system-strengthening element of the 3MDG Fund offers the opportunity to help to address the deficiencies in the lack of reliable data and inform health programmes.

Recommendation 2: DFID should work with other donors and the Ministry of Health to capture better quality information about the health sector in Burma and to create stronger and more robust monitoring systems and data baselines across key health programme areas.