DFID’s Humanitarian Emergency Response in the Horn of Africa

1. Introduction

1.1 The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review.

1.2 We have decided to review DFID’s humanitarian emergency response efforts in the Horn of Africa since October 2010. These Terms of Reference outline the purpose and nature of the review and identify its main themes. A detailed methodology will be developed during an inception phase.

2. Background

DFID’s humanitarian aid spending

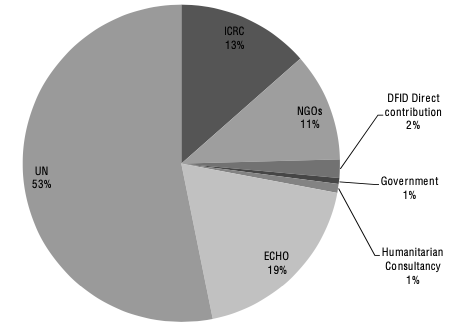

2.1 Humanitarian emergency response is one of the major priorities for UK assistance, an area in which the UK is a leading donor country. In 2009-10, DFID spent 8% of its budget (£528 million) on humanitarian assistance. Most of DFID’s expenditure is made through partners, encouraging a multilateral approach. DFID channels 86% of its expenditure through a combination of the United Nations (UN), the European Commission’s Humanitarian Office (ECHO) and the International Committee of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (ICRC). The remainder is channelled through non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and governments or spent on DFID’s own staff and consultants. Figure 1 shows the split between these funding streams.

2.2 DFID’s top ten humanitarian interventions in 2009-10 by expenditure, where it spent a total of approximately £230 million in humanitarian assistance, were in Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Somalia, Zimbabwe, West Africa, Pakistan, Haiti, the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Sri Lanka. Continuing chronic emergencies meant that many of the same countries from 2008-09 continued to be among the top ten recipients of humanitarian spending in later years. Exceptions were the inclusion of Sri Lanka, West Africa, Haiti and Pakistan due to the respective conflict, food crisis, earthquake and Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) crises.1

Pie chart showing: ICRC 13%, NGOs 11%, DFID Direct contribution 2%, Government 1%, Humanitarian Consultancy 1%, ECHO 19%, UN 53%

2.3 By definition, humanitarian aid is delivered in difficult circumstances. Speed is critical yet delivery channels are often undermined by challenges of poor infrastructure, security and a lack of the rule of law. The UK Government commissioned the Humanitarian Emergency Response Review (HERR) chaired by Lord Ashdown which examined the effectiveness of the UK government’s humanitarian interventions.3 DFID issued a response to the recommendations in the HERR in June 20114 and an updated humanitarian policy in September 2011.5

DFID’s humanitarian response in the Horn of Africa

2.4 From 2010-11, DFID focussed increasingly on the humanitarian crisis occurring in the Horn of Africa. This was a slow onset emergency; it built up over time as opposed to a sudden event such as a cyclone or earthquake. The crisis was brought on by a combination of severe drought, conflict and insecurity, governance failures, high food prices and limited humanitarian access. Oxfam and Save the Children estimate that more than 13 million people, most of them women and children, have been affected.6 In particular, over 260,000 refugees fled Somalia in 2011, putting increasing pressure on neighbouring Kenya and Ethiopia.7

2.5 While droughts are not uncommon, it is socio-economic factors that generally lead to humanitarian crises like this. The situation in the Horn of Africa was exacerbated by major governance failures. History repeated itself in Somalia where the BBC reported that ‘conflict, not drought, is the reason so many Somalis are dying needlessly’.8 The militant group Al-Shabaab sought to take control of humanitarian supplies in Somalia.9 Economic drivers can also exacerbate food shortages and famines, with farmers holding back food while prices rise. In Kenya, there were reports of ‘irregular disposal of three million-plus bags of maize from strategic grain reserves and subsidised fertiliser that senior ministry officials sold to farmers at exorbitant prices’ rather than being distributed on the basis of need as part of the national response.10

2.6 Even before the UN declared famine in parts of Somalia, DFID had ongoing humanitarian programmes focussed on vulnerable populations in Somalia and Kenya. In response to the unfolding crisis, DFID scaled up its activity in late 2010 and again in early 2011: some existing programmes were expanded and new programmes have been created. DFID anticipates that large-scale humanitarian needs will remain, especially in Somalia, during 2012.11

2.7 Since the beginning of the 2010-11 financial year, DFID has spent £162 million on humanitarian assistance in the Horn of Africa, £84 million of this in Somalia. This includes:

-

- multi-sectoral programmes (covering nutrition, food assistance, water, health, protection, shelter and/or livelihoods) currently targeting over 1 million people in Somalia, over 300,000 in drought-affected Kenya and 130,000 refugees in Dadaab, Kenya;

- World Food Programme food distributions and a third of the funding made available to the UN Humanitarian Response Fund in Ethiopia;

- support for the UN High Commission on Refugees to provide water and shelter for Somali refugees; and

- a wide range of policy lobbying and influencing activities with affected states, donors, the international humanitarian response community and the media, in an effort to seek a bigger and more effective international response and to advocate the rights of affected people.

2.8 Figure 2 shows how DFID’s humanitarian expenditure in the Horn of Africa has been split between Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia. More detail is included in the Annex. At this stage, the data received from DFID is aggregated from different years and sectors across humanitarian programmes and is not comparable. We aim to receive a further break-down of this data from DFID during our review.

| Country | Year | Expenditure |

|---|---|---|

| Kenya | 2010 | £8.8 million |

| 2011 | £16.9 million | |

| Somalia | 2010 | £30.3 million |

| 2011 | £55.5 million | |

| 2012 | £55.0 million (budgeted) | |

| Ethiopia | 2010-12 | £56.7 million |

3. Purpose

3.1 To assess the value for money and effectiveness of DFID’s humanitarian emergency response in the Horn of Africa, from early warning to the transition to longer-term development.

3.2 We will specifically focus on:

- the linkage between early warning, early action and longer-term preventative interventions;

- how intended beneficiaries’ needs were identified;

- the effectiveness of supply chain management to meet these needs;

- DFID’s role in leadership and co-ordination of aid and evidence of innovation; and

- how DFID has applied learning from previous interventions in the Horn of Africa and what it has learned to help build resilience and prevent future emergencies.

4. Relationship to other evaluations/studies

4.1 Recommendations in the HERR12 set out the need to:

- develop a more anticipatory approach to prepare for disasters and conflict;

- create resilience through both longer-term development and emergency response;

- improve the strategic, political and operational leadership of the international humanitarian system;

- innovate to become more efficient and effective;

- increase transparency and accountability towards both donor and host country populations;

- create new partnerships and build and strengthen existing ones; and

- defend and strengthen the humanitarian space.13

4.2 In terms of meeting the needs of intended beneficiaries, the HERR reported that ‘there is an accountability deficit. The people who are on the receiving end of our assistance are rarely if ever consulted on what they need, or able to choose who helps them or how. This means that gender-based issues and the needs of the vulnerable are too often overlooked. Whilst this has long been recognised as an issue, too little has been done about it.’

4.3 The HERR also acknowledged the key challenges of logistics and value for money in humanitarian interventions. Speed of response is critical, while also adding to the cost of assistance. The review reported that ‘logistics can account for as much as 80 per cent of the effort of humanitarian organisations during a relief operation, the global supply chain warrants special consideration. If DFID wants to improve its ability to respond at the right time for the right price and with the appropriate quality, supply chain management needs to be recognised as an integral part of preparedness and response.’ The review noted a number of examples of poor value for money through procurement errors. It recommended that DFID should ‘encourage the Independent Commission for Aid Impact to examine a range of Humanitarian cases and resilience building work’.

4.4 Regarding the Horn of Africa humanitarian response, in September 2011, the World Bank published a response plan for the drought, which provides an overview of the Bank’s response and how it worked with other key players such as the EU and bilateral donors.14 In January 2012, Oxfam and Save the Children published a report on the world’s humanitarian response in the Horn of Africa.15 They found that ‘the scale of death and suffering and the financial cost, could have been reduced if early warning systems had triggered an earlier, more substantial response’. They also reported the disproportionate impact on women who ‘generally eat last and least’. This affects their children’s health and has long-term development implications. Women and girls face even greater risks due to insecurity. (DFID’s 2005 study on the impact on women in conflict and post conflict environments highlights how this is exacerbated by forced migration where women are particularly ‘vulnerable to violence and exploitation’.16)

4.5 Since we are interested to see how DFID has applied learning, reports and evaluations on other humanitarian responses will also be useful. For example:

- Horn of Africa pre-2010: several studies have been conducted of the humanitarian context in the Horn of Africa prior to 2010, which will help us to understand how existing programmes and experience affected later interventions;17

- Pakistan floods: in May 2011, the International Development Committee published a report on the humanitarian response in Pakistan.18 This raised concerns about the pace of disbursement by the UN: only 60% of funds raised (approximately £450 million) were disbursed between August 2010 and February 2011; and

- Haiti earthquake: a DFID evaluation of the response to the Haiti earthquake highlighted areas of good practice but also that ‘old mistakes were repeated and new ones made’.19 This report emphasised the lack of co-ordination amongst donors and delivery organisations and the lack of proper engagement with local stakeholders.

4.6 Assessments by other development agencies, such as USAID, on their humanitarian interventions will also provide important reference points for learning.20 There are also many other reports examining humanitarian aid work:

- the National Audit Office (NAO) has produced reports on humanitarian aid in 2003, specific interventions such as the tsunami in 2005 and operating in insecure environments in 2008;21

- ECHO and UN agencies (such as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR, and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, OCHA) have conducted a range of country, thematic and partnership evaluations.22 These cover topics such as Humanitarian Negotiations with Armed Groups and assessments of partners such as ICRC. ECHO also produced a study of quality management tools in 2002, which provides a useful framework relating to assuring the quality of NGO procurement;23 and

- agencies such as the Overseas Development Institute’s (ODI’s) Humanitarian Policy Group and ITAD carry out independent evaluation studies. These include Dependency and Humanitarian Relief, Measuring the Impact of Humanitarian Aid and Preventing Corruption in Humanitarian Assistance.24 One example of a study which considered cost-effectiveness issues more fully was ODI’s evaluation of an Oxfam emergency cash transfer programme in Zambia in 2006.25

5. Analytical approach

5.1 We will focus on four phases of DFID’s assistance in the Horn of Africa:

- the early warning systems and decision to mobilise major resources;

- the initial response after the decision to mobilise major resources;

- the consolidation of the humanitarian response; and

- a window later on, when DFID was working on the transition to a longer-term intervention and on promoting resilience and prevention. We will determine the exact timeframe to be examined during the inception phase.

5.2 First, we will consider the linkages between phases:

- between early warning and early action;

- between pre-existing interventions and humanitarian emergency assistance; and

- between humanitarian emergency assistance and longer-term development programmes.

5.3 Second, we will consider how DFID identified which groups of people it should target and their needs. We will specifically consider how DFID assesses the needs of women and marginalised groups. We will focus on how DFID engages with and is accountable to its intended beneficiaries, considering how the other six areas outlined in the HERR can influence this, in particular, DFID’s leadership, innovation and learning and its anticipatory approach.

5.4 Third, we will look at the distribution and flow of funding from DFID to intended beneficiaries via a range of international organisations and NGOs. We will examine the link between money flows and supply processes and the efficiency of these. We will consider the extent to which value for money considerations were used appropriately and fit-for-purpose standards of procurement and accounting were followed. We will assess these in the wider context of the impact on the local community, including:

- assessing the impact on local markets of employment and procurement decisions (e.g. purchasing locally as opposed to imports);

- assessing how well the assistance supports the transition from crisis response to ongoing development; and

- analysing intended and unintended changes in local institutions and relationships between stakeholders.

5.5 Fourth, we will look at how DFID used its influence to help raise the profile of the needs in the Horn of Africa and to co-ordinate the delivery of aid. We will examine how effectively DFID used early warning signals to initiate its humanitarian response and how DFID engages with other donors and actors (especially DG ECHO, UN agencies and ICRC and national and regional governments and stakeholders) to help ensure that aid is co-ordinated. We will specifically look at DFID’s leadership and co-ordination in relation to identifying intended beneficiaries’ needs and getting value for money from supply chains. We will consider how DFID works with other UK government departments who are also active in the region.

5.6 Fifth, we will look at the extent to which DFID has learnt from previous aid efforts and applied this knowledge to the Horn of Africa intervention. We will also consider how effectively learning took place during the intervention to improve aid delivery and outcomes. Finally, we will look at the mechanisms DFID has to identify and share learning from the Horn of Africa with other current and future interventions.

6. Indicative questions

6.1 This review will use as its basis the standard ICAI guiding criteria and evaluation framework, which are focussed on four areas: objectives, delivery, impact and learning. The questions outlined below comprise those questions in our standard evaluation framework which are of particular interest in this review, as well as other pertinent questions we want to investigate. The full, finalised list of questions that we will consider in this review will be set out in the inception report.

6.2 Objectives

6.2.1 How well did DFID gather and respond to early warning signals indicating the onset of crisis?

6.2.2 Does DFID’s approach in the Horn of Africa have clear, relevant and realistic objectives that focus on the needs of intended beneficiaries? How did DFID identify its intended beneficiaries and their needs?

6.2.3 Is DFID’s approach complementary across all Horn of Africa countries and consistent with its overall humanitarian strategy?

6.2.4 Does DFID co-ordinate effectively with other donors and demonstrate leadership? Does DFID engage effectively with local, national and regional stakeholders to help create an effective humanitarian space?

6.2.5 Are DFID’s Horn of Africa interventions based on robust analysis of the regional and local contexts, building on its existing initiatives in the region?

6.3 Delivery

6.3.1 Is DFID’s choice of delivery options appropriate and focussed on how it can deliver the best impact for its intended beneficiaries?

6.3.2 Have governance and financial management systems appropriately addressed the risks of operating in challenging environments, while ensuring accountability to donor and host country populations? What measures are in place to prevent corruption and wastage?

6.3.3 Are resources being leveraged so as to work best with others and maximise impact and provide value for money?

6.3.4 Were appropriate steps taken to involve and consult with intended beneficiaries and local stakeholders to ensure that appropriate goods and services were supplied?

6.3.5 Is there a clear view of costs throughout the delivery chain? What were the costs of delivery, were unit costs monitored and did they reflect good value for money?

6.3.6 Was adequate speed of delivery achieved in the circumstances while managing governance and financial risks?

6.4 Impact

6.4.1 Are initiatives delivering clear, significant and timely benefits for the intended beneficiaries in an accountable and transparent way?

6.4.2 Is there a long-term and sustainable impact from initiatives and are they contributing to building resilience to disasters in the target countries and populations?

6.4.3 Is there an appropriate exit strategy for humanitarian initiatives involving effective transition to longer-term development programmes?

6.4.4 Are there any unintended impacts of note, including on institutions and other actors?

6.5 Learning

6.5.1 Are there appropriate arrangements for monitoring inputs, processes, outputs, results and impact?

6.5.2 Is there evidence of innovation and use of global best practice? How has experience from previous interventions helped to influence Horn of Africa interventions?

6.5.3 Is there anything currently not being done in respect of the programme that should be undertaken?

6.5.4 Have lessons about the objectives, design and delivery of the programme been learned and shared effectively?

6.5.5 What lessons have been learned, particularly those which may assist DFID in responding to the HERR recommendations?

7. Outline methodology

7.1 The review will involve a number of elements, including:

- a brief review and synthesis of evidence available internationally from evaluations of humanitarian and emergency programmes;

- evidence-gathering through discussions with DFID senior management and relevant stakeholders and headquarters staff of relevant agencies that have played a major role in the delivery of UK humanitarian emergency assistance;

- undertaking field visits within Kenya to review systems and documentation, and meet with intended beneficiaries and staff from DFID, partners, other donors and stakeholders;

- reviewing publicly-available reports from major humanitarian institutions to identify lessons learned from humanitarian interventions in the last two years; and

- completing a final report based on the evidence gathered.

8. Timing and deliverables

8.1 The review will be overseen by Commissioners and implemented by a small team from ICAI’s consortium. The review will take place during the second quarter of 2012, with a final report available by the end of this quarter.

Annex

| Agency | Location | Sector | Start | End | Programme/ project total | Expenditure to date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somalia Humanitarian Programme 2010 | National (mostly south central) | Multi-sectoral | Oct 2010 | March 2012 | £30,400,000 | £30,340,229 |

| Programme Subcomponents | ||||||

| World Health Organisation | National | Health – Child Health Days | 1st Nov 2010 | 31st March 2011 | £1,400,000 | 1,400,000 |

| Oxfam GB | South Somalia & Somaliland | Water and Sanitation | 1st Nov 2010 | 31st Dec 2011 | £1,000,000 | £1,000,000 |

| Action Against Hunger | Bakool & Mogadishu, South Somalia | Nutrition | 1st Oct 2010 | 31st Dec 2011 | £1,700,000 | £1,670,346.24 |

| MEDAIR | Somaliland | Health, Nutrition & WASH Programme | 1st Nov 2010 | 31st Jan 2012 | £850,513 | £850,513 |

| GIZ | Bay, South Somalia | Health and Nutrition | 1st Nov 2010 | 31st March 2012 | £610,040 | £610,040 |

| NGO Security Programme Grant 2011 (£250k) and South Central Zone (SCZ) Evaluation (£30k) (Danish Refugee Council) | National | Staff safety and training; SCZ Evaluation | 1st Nov 2010 | 31st Dec 2011 | £280,000 | £280,000 |

| Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit | National | Food Security and nutrition assessment and analysis | 4th Oct 2010 | 31st March 2011 | £1,000,000 | £1,000,000 |

| International Committee for the Red Cross | South central | Multi-sectoral | 7th Dec 2010 | 31st Dec 2011 | £4,000,000 | £4,000,000 |

| Somalia Common Humanitarian Fund 2010 | National (mostly south central) | Multi-sectoral | Nov 2010 | 31st March 2011 | £15,840,000 | £15,840,000 |

| Somalia United Nations OCHA 2010 | National | Co-ordination | Dec 2010 | 31st March 2011 | £160,000 | £160,000 |

| Somalia United Nations Children’s Fund 2010 | National (mostly south central) | Nutrition & WASH | Oct 2010 | 31st March 2011 | £3,500,000 | £3,500,000 |

| Somalia Humanitarian Programme 2011 | South central Somalia | Multi-sectoral | July 2011 | Jul 2012 | £57,270,000 | £55,496,305 |

| Programme Subcomponents | ||||||

| Oxfam – Emergency WASH and Livelihoods Project | Lower Juba, Mogadishu | WASH | 1st Aug 2011 | 31st Jul 2012 | £2,500,000 | £2,019,189 |

| International Committee of the Red Cross – Multi-Sectoral Appeal 2011 | South central | Multi-sectoral | 1st Aug 2011 | 31st Dec 2011 | £4,500,000 | £4,500,000 |

| Common Humanitarian Fund – Somalia (UNOCHA)- Multi-Sectoral Appeal | National | Multi-sectoral | 1st Jul 2011 | 31st Dec 2011 | £4,000,000 | £4,000,000 |

| United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) | South central | Nutrition, Water and Sanitation | 15th Jul 2011 | 31st Dec 2012 | £3,500,000 | £3,500,000 |

| Action Against Hunger | Bakool | Nutrition and Food Assistance | 1st Aug 2011 | 29th Feb 2012 | £2,000,000 | £1,794,928.97 |

| Concern Worldwide | Lower Shabelle, Bay, Mogadishu | Food and Nutritional Support cash-based | 1st Aug 2011 | 30th Sept 2012 | £2,000,000 | £1,820,531 |

| Save the Children | Bay and Bakool | Health, WASH, Food Assistance | 1st Aug 2011 | 30th Jul 2012 | £3,000,000 | £2,715,127 |

| World Food Programme | Southern Somalia | Food Aid | 1st Aug 2011 | 31st March 2012 | £2,900,000 | £2,900,000 |

| Food and Agriculture Organizations | South central | Livelihoods | 18th Aug 2011 | 31st Dec 2011 | £4,000,000 | £4,000,000 |

| United Nations Children Fund | South central | Health & Nutrition | Aug 11 | Mar 12 | £26,126,347 | £26,136,347 |

| World Health Organisation | South central | Vaccinations and Health Cluster Coordination- | 1st Sep 2011 | 31st March 2012 | £1,830,000 | £1,830,000 |

| Somalia Humanitarian Programme 2012 | National (mostly south central) | Multi-sectoral | Jan 2012 | March 2013 | £55,000,000 | £22,000,000 |

| Common Humanitarian Fund – Somalia | National | Multi-sectoral | Jan 2012 | Dec 2012 | £16,000,000 | £16,000,000 |

| Food and Agriculture Organization | National | Livelihoods | Feb 2012 | Dec 2012 | £6,000,000 | £6,000,000 |

| Ethiopia | 2010-12 | £69,926,514 | £56,709,848 | |||

| UNOCHA in management of the Humanitarian Response fund (HRF) | Country wide | Multi-sectoral Humanitarian Response | Mar 2011 | Feb 2013 | £25,000,000 | £14,000,000 (in 2011-12) |

| UNHCR | Dolo Ado refugee camps in South eastern Ethiopia | Shelter, water and sanitation, non-food items and registration for refugees | Jul 2011 | Dec 2011 | £4,000,000 | £4,000,000 |

| WFP | Country wide | Food and nutrition | Aug 2011 | Jan 2012 | £38,000,000 | £38,000,000 |

| UNICEF | Amhara, Oromia, SNNPR, Somali, and Afar | Nutrition Surveillance | Nov 2010 | Nov 2012 | £ 2,000,000 | £550,000 (in 2011-12) |

| Mercy Corps | Somali Region | Humanitarian capacity building | Jan 2011 | Dec 2013 | £926,514 | £159,848 (in 2011-12) |

| Kenya humanitarian programme 2010 | Focus on drought prone arid and semi arid lands | Multi-sectoral | Oct 2010 | March 2012 | £8,800,000 | £8,751,969.11 |

| Programme subcomponents | ||||||

| UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) | Dadaab & Kakuma | Multi-sectoral refugees | 1st Nov 2010 | 31st March 2011 | £2,000,000 | £2,000,000 |

| Save the Children UK | Wajir, mandera | Nutrition and Health | 15th Oct 2010 | 30th Sept 2011 | £1,199,888 | £1,199,888 |

| Action Against Hunger | Isiolo, Kenya | Health & Nutrition | 1st Oct 2010 | 31st Oct 2011 | £1,240,000 | £1,240,000 |

| SOLIDARITES International | Marsabit | Disaster Risk Reduction | 1st Oct 2010 | 31st Oct 2011 | £825,000 | £825,000 |

| Islamic Relief Kenya | Wajir | Nutrition & Health | 1st Nov 2010 | 31st Oct 2011 | £601,000 | £601,000 |

| UNICEF Nutrition Support 2011 | Arid and semi arid north | Nutrition & WASH | Dec 2010 | March 2011 | £1,533,916 | £1,533,916 |

| UNOCHA Emergency Response Fund | Arid and semi arid north | Multi-sectoral | Feb 2011 | March 2011 | £1,000,000 | £1,000,000 |

| UNOCHA | National | Co-ordination | 17th Feb 2011 | 31st March 2011 | £150,000 | £150,000 |

| Kenya humanitarian Drought response 2011 | Arid and semi arid north | Multi-sectoral | Jul 2011 | March 2012 | £11,250,000 | £10,900,141.28 |

| Programme subcomponents | ||||||

| United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) | Arid and semi arid north | Emergency livelihoods, WASH and health | 10th Aug 2011 | 31st March 2012 | £3,200,000 | £3,200,000 |

| World Food Programme (WFP) | Northern & North Eastern | Food and Nutrition | Aug 2011 | Dec 2011 | £5,000,000 | £5,000,000 |

| Save the Children, UK (SCUK) and NGO | Northern Kenya | Consortium – Food Security, livelihoods and Provision Water | 1st Aug 2011 | 31st March 2012` | £3,000,000 | £2,682,923 |

| Kenya humanitarian refugee programme 2011 | Dadaab | Multisectoral | Jul 2011 | March 2012 | £6,000,000 | £6,000,000 |

| Programme subcomponents | ||||||

| UNHCR | Dadaab | Multi-sectoral | Aug 2011 | Jan 2012 | £3,630,000 | £3,630,000 |

| WFP | Dadaab | Nutrition | Aug 2011 | Jan 2012 | £1,250,000 | £1,250,000 |

| CARE | Dadaab | WASH | Aug 2011 | Mar 2012 | £620,000 | £620,000 |

| OXFAM | Dadaab | WASH | Aug 2011 | Mar 2012 | £500,000 | £500,000 |

Footnotes

- DFID’s Expenditure on Humanitarian Assistance 2009/10, DFID, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/humanitarian-spend-report0910.pdf.

- Humanitarian Emergency Response Review, Humanitarian Emergency Response Review, March 2011, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/HERR.pdf.

- Humanitarian Emergency Response Review, Humanitarian Emergency Response Review, March 2011, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/HERR.pdf.

- Humanitarian Emergency Response Review: UK Government Response, DFID, June 2011, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/hum-emer-resp-rev-uk-gvmt-resp.pdf.

- Saving lives, preventing suffering and building resilience: The UK Government’s Humanitarian Policy, DFID, September 2011, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/1/The%20UK%20Government’s%20Humanitarian%20Policy%20-%20September%202011%20-%20Final.pdf.

- A Dangerous Delay: the cost of late response to early warnings in the 2011 drought in the Horn of Africa, Oxfam and Save the Children, 18 January 2012, http://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/a-dangerous-delay-the-cost-of-late-response-to-early-warnings-in-the-2011-droug-203389.

- DFID documentation

- Somalia drought: Tragic history repeats itself, BBC, 10 August 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-14481103.

- Somalia: UN strongly condemns seizure of aid agency assets by insurgent group, UN News Centre, 28 November 2011, http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=40539

- Hard times getting tougher for poor Kenyans, The Standard, 28 May 2011, http://www.standardmedia.co.ke/InsidePage.php?id=2000036074&cid=4.

- DFID documentation

- Humanitarian Emergency Response Review, Humanitarian Emergency Response Review, March 2011, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/HERR.pdf.

- Humanitarian space refers to the access and protection of humanitarian workers when providing humanitarian assistance. This requires assistance to be given on the basis of need and need alone in return for access and protection in conflict affected areas.

- Response Plan: Drought in the Horn of Africa, World Bank, September 2011, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTAFRICA/Resources/Drought_in_the_Horn_of_Africa_7.28.2011.pdf.

- A Dangerous Delay: the cost of late response to early warnings in the 2011 drought in the Horn of Africa, Oxfam and Save the Children, 18 January 2012, http://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/a-dangerous-delay-the-cost-of-late-response-to-early-warnings-in-the-2011-droug-203389.

- ‘Evaluation of DFID Development Assistance: Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment’, Nicola Johnston for DFID, March 2005, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/evaluation/wp12.pdf.

- For example, Horn of Africa Crisis Report, UN Office for the coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 2009, http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/newsroom/docs/Horn%20of%20Africa%20Crisis%20Report%20February%202009.pdf; Mid Term Evaluation of DG ECHO’s Regional Drought Decision in the Greater Horn of Africa, DG ECHO, 2009, http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/evaluation/2009/GHA_2009.pdf; and Evaluation of the Danish Engagement in and around Somalia 2006-10, DANIDA, 2010, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/55/3/49649335.pdf.

- International Development Committee Seventh Report: The Humanitarian Response to the Pakistan Floods, House of Commons, April 2011, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmintdev/615/61502.htm.

- Haiti Earthquake Response: Emerging Evaluation Lessons, Jonathan Patrick for DFID, June 2011, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/58/42/48373454.pdf.

- See http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/humanitarian_assistance/disaster_assistance/.

- Department for International Development: Responding to Humanitarian Emergencies, NAO, 2003; Tsunami: Provision of Financial Support for Humanitarian Assistance, NAO, 2005; and Department for International Development: Operating in Insecure Environments, NAO, 2008.

- See http://www.unocha.org/about-us/publications, http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/search?page=search&query=evaluation+report and http://ec.europa.eu/echo/evaluation/index_en.htm.

- Report on the Analysis of ‘Quality Management’ Tools in the Humanitarian Sector and their Application by NGOs, European Commission Humanitarian Office, September, 2002, http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/evaluation/2002/thematic_qm.pdf.

- See: http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/docs/277.pdf; http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/docs/281.pdf; and http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/docs/1836.pdf respectively.

- Independent Evaluation of Oxfam GB Zambia’s Emergency Cash-Transfer Programme, ODI Humanitarian Policy Group, May 2006, http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/download/606.pdf.

- DFID documentation