DFID’s scale-up in fragile states – Terms of Reference

1. Introduction

1.1 The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review.

1.2 We have decided to undertake a review of the scaling up of the UK Department for International Development’s (DFID’s) support to fragile states. DFID has committed to spending 30% of Official Development Assistance (ODA) to support these countries and tackle the drivers of instability by 2014-15 (up from 22% in 2010). We will: examine the strategy and allocation process for scaled-up funds; review the capability of both DFID and the delivery chain to absorb these funds; and review the quality and impact of programming of the funds.

1.3 These Terms of Reference outline the purpose and nature of the review and the main themes that it will investigate. A detailed methodology will be developed during the inception phase.

2. Background

Context of fragility

2.1 There is no single agreed definition of a fragile state. DFID’s working definition of fragile and conflict-affected states includes countries where the government cannot or will not deliver core state functions, such as providing security and justice across its territory and basic services to the majority of its people.1

2.2 DFID compiles its list of fragile and conflict-affected states by drawing on three different indices: the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA), the Failed States Index of the Fund for Peace and the Upsala Conflict Database. Other donors and international organisations use different definitions and, as a result, there are several different lists of countries that are defined as fragile or conflict-affected. DFID categorises 21 of its 28 priority countries as fragile and conflict-affected states.

2.3 Poverty is becoming increasingly concentrated in fragile states. It is estimated that, by 2015, half of the world’s people surviving on less than $1.25 a day will be found in fragile states. People in fragile states are more than twice as likely to be undernourished as those in other developing countries; more than three times as likely to be unable to send their children to school and twice as likely to see their children die before the age of five. In 2013, the World Bank reported that twenty fragile and conflict-affected states had met one or more Millennium Development Goal (MDG) targets, however fragile states continue to lag behind the rest of the developing world as the majority of MDG targets in fragile states will still not be met by 2015.2 While most fragile states were low income a decade ago, today almost half are middle income, including five where DFID has bilateral programmes. These are Nigeria, the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPTs), Pakistan, Sudan and Yemen.3

2.4 Although not all fragile countries are in conflict (such as Liberia) and others are able to ensure service entitlements but have ongoing internal or external conflict,4 for example Ethiopia, there is a high correlation: a large proportion of fragile states are conflict or immediate post-conflict states. Fragility and conflict are mutually reinforcing: states can be pushed into fragility through the eruption of localised or regional conflict; and fragility can drive conflict. Fragility matters because of the risk it poses to regional and global stability. Furthermore, conflict in one fragile state has a tendency to create instability and conflict in neighbouring states, which over time can have serious effects on the regional economic and social indicators.

2.5 This review will focus on issues of fragility. Although many of the countries which are identified as fragile are also conflict affected, this ICAI report will not focus purely on programmes which seek to tackle issues of conflict prevention, in order to avoid any duplication of findings from the previous ICAI review on Conflict Pool activities.5

DFID’s approach and scale-up to fragile and conflict-affected states

2.6 DFID is scaling up its work in fragile and conflict-affected states more rapidly than in other countries, in recognition of the increasing share of poor people who are located in these countries. In 2010, the UK Government committed to spending 30% of UK ODA to support these countries and tackle the drivers of instability by 2014-15. In 2010, DFID’s bilateral annual expenditure in fragile and conflict-affected states was projected to rise from £1,839 million in 2010-11 to £3,414 million in 2014-15.

2.7 Although a considerable amount of the expenditure increase will be earmarked for transfers to central multilateral budgets, financial resources to country programmes is also increasing. In parallel, the 2011 Bilateral Aid Review (BAR)6 reduced the number of DFID focus countries from 43 to 28, graduating many of the less fragile countries from UK aid. The combination of the increase in resources, the increased proportion of fragile states amongst DFID’s focus countries and the commitment to spend 30% on fragile and conflict-affected states means that there will be significantly larger financial resources channelled through bilateral programmes in fragile and conflict-affected states.

2.8 DFID is not alone in increasing focus on fragile states. The World Bank has been consciously focussing on how it can work differently and more effectively in fragile states for a decade. At the 2011 4th High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness, the major bilateral and multilateral donors committed to the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States.7 DFID is at the forefront of this emerging focus on fragile states and is making a more concerted effort to focus increased resources on them. Findings from this study may be of interest to other donors who are New Deal partners. This review will also examine DFID’s scale-up in the context of the other donor scale-ups.

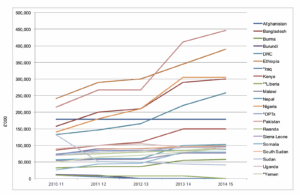

2.9 The Secretary of State announced that scaling up ODA in fragile and conflict-affected states, along with the creation of the National Security Council and the strong focus in the Strategic Defence and Security Review on conflict prevention, would facilitate and strengthen UK efforts to prevent and tackle conflict. ‘Work to prevent and respond to conflict and fragility saves lives and reduces human suffering, it is essential for poverty reduction and progress against the MDGs and it can help to address threats to global and regional stability’.8 Figure 1 on page 3 illustrates the volume of the scale-up.

2.10 According to the 2011 Bilateral Aid Review, the top five recipients for DFID’s budget allocations for fragile and conflict-affected states will experience budget increases from the 2010-11 baseline to the 2014-15 target. The top five aid recipients of overall scaled-up aid by 2014-15 include (numbers indicate percentage increase):

- Nigeria – 116%

- Pakistan – 107%

- DRC – 94%

- Bangladesh – 91%

- Ethiopia – 62%

2.11 Figure 1 on page 3 sets out the increases in DFID budget allocation from the 2010-11 baseline to planned scale-up by 2014-15. For a more detailed breakdown of these figures, see the Annex.

2.12 The largest jump in allocations for most countries occurred in 2013-14, with significant upward changes also in 2012-13. Further increases are planned in 2014-15 for some countries.

| 2010-11 to 2011-12 | 2011-12 to 2012-13 | 2012-13 to 2013-14 | 2013-14 to 2014-15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somalia (69.23%) | Nigeria (16.67%) | Somalia (73.91%) | DRC (17.27%) |

| Yemen (30%) | DRC (12.24%) | Nigeria (66.67%) | Ethiopia (13.04%) |

| Nigeria (27.66%) | Kenya (10%) | Pakistan (54.31%) | Yemen (12.50%) |

DFID Strategies

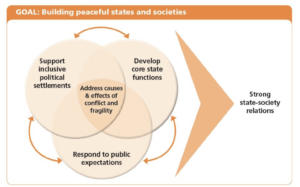

2.13 There are a range of DFID strategies that focus on working in fragile and conflict-affected states. DFID’s 2010 Practice Paper10 outlines a new, integrated approach, which puts state-building and peace-building at the centre of work in fragile and conflict-affected countries. The approach is based on four objectives, as illustrated in Figure 3 on page 4. These are:

- supporting inclusive political settlements;

- developing core state functions;

- responding to public expectations; and

- addressing causes and effects of conflict and fragility.

2.14 The operational implications of these objectives are outlined in the Practice Paper as:

- recognition that politics are central to work in fragile and conflict-affected states;

- building consensus with external partners;

- analysing the context using the integrated framework; and

- leading to different priorities and choices.

2.15 The Building Stability Overseas Strategy (BSOS) deals specifically with conflict countries, the majority of which are also fragile states. The strategy was produced jointly by DFID, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the Ministry of Defence (MOD) in July 2011 and commits the UK to an integrated approach to building stability, spanning its diplomatic, development and defence interventions. The commitment to ‘upstream prevention’ focusses on the need to address the underlying causes of fragility. DFID is investing more time analysing the initial context, through for example, a new conflict early warning system.

2.16 BSOS comprises three key pillars:

- early warning: improving DFID’s ability to anticipate instability and potential triggers for conflict;

- rapid crisis prevention and response: taking fast, appropriate and effective action to prevent a crisis or stop it from escalating; and

- investing in upstream prevention: helping to build strong, legitimate institutions and robust societies in fragile countries that are capable of managing tensions and shocks.

2.17 Both the DFID Practice Paper and BSOS acknowledge the critical challenge of understanding poverty within the wider political context and the need to address (not avoid) the root causes of fragility. Both highlight the need to move beyond ‘one size fits all’ models and work to strengthen the conceptual foundations for engagement and overall evidence base in fragile and conflict-affected states. The question remains, however, as to how this has been translated into practice.

2.18 The UK Government has also endorsed the 2011 New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States, along with over forty other countries and international organisations, at the Busan High Level Forum. The New Deal is being piloted in a range of fragile states and has three core elements:

- five Peacebuilding and Statebuilding Goals: legitimate politics; security; justice; economic foundations; and revenues and services;

- a shared commitment to supporting country leadership; and

- donor commitments to working more effectively by, among other things, increasing aid transparency, sharing risk and providing timely and predictable aid.

2.19 The 2011 New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States commits fragile states and international partners to ‘do things differently’. It calls for approaches to risk management that are better tailored to fragile contexts. It includes a commitment to greater investment in country systems, to timely and predictable aid and to building critical local capacities. It pledges to structure interventions around peace-building and state-building goals.

2.20 The commitment to spend 30% of UK aid in fragile contexts potentially exposes DFID to a range of new risks, especially fiduciary risks. Scale-up is likely to be more difficult to achieve well in fragile countries. At a country level, DFID is likely to face a number of key challenges in terms of scale-up, including:

- weakness of government agencies;

- lack of capability in local partners;

- weakness of local civil society;

- limited absorptive capacity of local partners, resulting in slow scale-up;

- reliance on third parties (UN agencies, international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and contractors) to do much of the work on the ground;

- mixed capabilities of multinational delivery agencies;

- the ability to establish reliable logistical chains;

- lack of access to parts of the country (or even the country as a whole) for DFID staff because of security issues;

- difficulty in getting DFID staff to deploy to the country for long periods; and

- poor evidence of what works in such environments.

2.21 These challenges create enhanced risks for DFID. It remains to be seen whether there is sufficient internal capacity or good programming in country, to absorb the levels of funds that DFID is now committing. DFID is already aware that the mechanisms for project design and delivery of aid in fragile and conflict-affected states need to be strengthened. According to the 2010 Synthesis of Country Programme Evaluations Conducted in Fragile States report, DFID has committed ‘to finding better ways of delivering aid to fragile states’ and believes that ‘a broader range of adapted aid instruments should be used in fragile states, than those used in good performers, in order to minimise risk’.11

3. Purpose of this review

3.1 The purpose of this review is to consider whether DFID additional funds in fragile states have delivered worthwhile additional impact that is likely to be sustained. We will examine the strategy and allocation process for scaled-up funds, to review the capability of both DFID country offices and the delivery chain to absorb these funds. We will then review the quality of programming of the funds and assess whether the additional funds have achieved additional impact for intended beneficiaries.

4. Relationship to other evaluations and studies

ICAI reports

4.1 We have conducted reviews in almost all of the DFID priority countries identified as fragile and conflict-affected states, through our work to date. Some examples of these include:

- ICAI’s review on the Inter-Departmental Conflict Pool,12 where we conducted fieldwork in Pakistan and the DRC to assess the Conflict Pool’s multidisciplinary approach to conflict prevention. The report highlights that more work needs to be done to develop a clear strategic framework and robust funding model;

- ICAI’s review on DFID Programme Controls and Assurance in Afghanistan,13 which concluded overall that DFID needs to improve its financial management processes in a fragile state environment; and

- ICAI’s review on DFID’s Approach to Anti-Corruption,14 where we visited Bangladesh, Nepal and Zambia DFID country offices. The review concludes that DFID’s planned focus on fragile states, along with the planned increase in the aid budget, exposes the UK to higher levels of corruption risk. The review makes recommendations on how DFID can reduce these risks and work better with partner countries to address the root causes of corruption.

4.2 All three of these reports scored an Amber-Red rating and will provide initial material on which to draw.

4.3 In addition to those mentioned above, other ICAI reports relevant to the topic of fragile states include ICAI’s published reports on DFID’s Bilateral Support to Growth and Livelihoods in Afghanistan,15 DFID’s Work with UNICEF16 and the UK’s Humanitarian Emergency Response to the Horn of Africa.17 We will draw on findings and consider the conclusions from all relevant ICAI reviews throughout this study.

4.4 ICAI has planned further reviews on Impact, Anti-corruption and Security and Justice, relating to the context of delivering aid in fragile states. We will liaise with other review teams to avoid duplication and ensure links are made where appropriate.

Other reports

4.5 DFID’s Evaluation Department (EvD) annually commissions a series of Country Programme Evaluations (CPEs). The Synthesis of DFID’s Country Programme Evaluations Conducted in Fragile States report was published in 2010.18 This report examined DFID country programmes in ten fragile states19 over an eight-year period (2002-09). It examined five key areas:

- the scaling up of aid;

- the links between security and development;

- state-building and support to core state functions;

- DFID’s partnerships; and

- DFID’s operational efficiency and monitoring and evaluation processes.

4.6 The report found positive examples of DFID engagement in state-building and peace-building in fragile states. The report highlighted that DFID saw itself as a champion of promoting aid effectiveness in fragile settings and as being better equipped than other donors to do this. The conclusions and recommendations in this synthesis which have particular relevance for this review include:

- DFID had scaled up its aid frameworks substantially and devolved offices had performed well in finding more locally appropriate solutions and adapting policy guidance to national contexts but building greater country presence requires better staffing responses; and

- staff recruitment is difficult, turnover is high and applicants are few. Where DFID expands its funding in fragile states, its Directors for HR must match this with earlier build-up and better sequencing of staff with sufficient seniority and expertise.

4.7 The International Development Committee’s (IDC’s) Twelfth Report, on Working Effectively in Fragile and Conflicted-Affected States, focusses on DFID’s work in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda.20 It is the first of a series of IDC reports to be published on fragile and conflict-affected states. The IDC reported that DFID needs to be clear and open about the reasons for which it operates in different fragile countries and the basis on which it makes its choices. It found that the needs effectiveness indicator which has been used by DFID has a bias towards large populous countries with large numbers of poor people, while giving insufficient weight to the proportion of people living on less than $2 a day.

4.8 We will draw on the reports mentioned above to inform our work.

5. Analytical approach

5.1 Our review will examine whether DFID has the capacity to deliver the desired scale-up of aid and whether the scale-up of ODA is likely to achieve the intended impact on the poor. This review will focus on the following questions:

- How does DFID make its choices of which countries and by how much to scale up?

- Does DFID have in place the right systems and processes internally to absorb scaled-up funds, while limiting the risks of corruption and inefficiency?

- Are the potential delivery channels in fragile states capable of absorbing and appropriately spending additional funding at the pace and volumes allocated by the scale-up?

- What evidence is there that DFID country offices in these environments have fit-for-purpose structures and organisational capabilities?

- Does DFID have the right strategy and capacity to identify, design and manage effective and appropriate interventions to achieve results in relation to a specific country context?

- Is DFID able to show that its interventions can make sufficient difference/impact for intended beneficiaries in fragile states to justify the incremental risks and costs and how is DFID dealing with the additional difficulties of evaluation and measuring impact in such situations?

- Has DFID met its share of commitments to do things differently in fragile states, including Practice Paper and New Deal commitments to ‘doing things differently’ and BSOS commitments to early warning, rapid crisis prevention and response and investing in upstream prevention?

5.2 In this review, we will assess whether DFID’s scale-up of aid in fragile states has been based on sound and coherent spending allocation processes, in a way that reflects specific country contexts (including their drivers of fragility) and the needs of intended beneficiaries. Questioning wider UK Government policy – in this particular case, the initial decision to scale up aid in fragile states – remains outside the remit of our review.

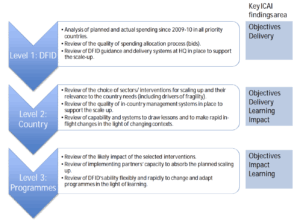

5.3 DFID has committed to scale up ODA in fragile and conflict-affected states through both increased bilateral aid and an increased contribution to multilateral aid. In this review, we will focus on the former: the programming at country level. This will include scrutiny of programming decisions that involve use of multilaterals, as this is a common programming decision in fragile states. During our country visits, our selection of case studies at programme level will include multilateral as well as bilateral programmes. Our approach will entail a three-level analysis, as shown in Figure 4.

5.4 This approach will enable us to address all relevant questions under the ICAI assessment framework on objectives, delivery, impact and learning. Selected questions are given in Section 6.

5.5 The choice of country case studies will be confirmed at inception stage, drawing on our initial review of DFID HQ spending allocation processes. We will select 2-3 countries for which DFID has made a significant commitment to scaling-up, as set out in Section 2 on page 1.

5.6 We will ensure that our final choice of countries offers a representative sample of DFID’s different forms of engagement in fragile states. Selection criteria will include:

- the level of planned versus actual spending, in particular identifying countries where financial records indicate that DFID has not been able to spend all of its planned budget commitments and where spending has been concentrated at certain phases of the budget cycle;

- countries where there has been rapid and substantial scale-up;

- the choice of aid delivery mechanisms, type of implementing partners and their capacity;

- the main characteristics of the country’s fragility and poverty; and

- the nature and level of maturation of the interventions begun as part of the scale-up process.

5.7 With this approach, our final case studies will focus on 1-2 programmes in each of the selected countries, with the aim of providing contrasting examples of DFID’s choice of priority sectors, aid delivery models and implementing partners. Our choice of selected interventions will include a range of service delivery programmes (education, health, water and sanitation) and governance programmes (justice, public financial management and decentralisation) as well as different delivery mechanisms.

5.8 Overall, our approach will enable a combination of breadth and depth in the review: from analysis of the initial robustness of the aid allocations between priority countries, to an overview of selected country programmes and into the detail of 4-6 specific programmes designed to address the drivers of fragility in these countries.

6. Indicative questions

6.1 Objectives

6.1.1 Does DFID spending allocation centrally and at country level have clear, relevant and realistic objectives that focus on the desired impact and are in line with DFID’s commitments in the 2010 Practice Paper and with the BSOS three pillars?

6.1.2 Are the selected programmes based on both sound evidence and credible assumptions, given the fragile country context, as to how their activities will lead to the desired impact (a theory of change)?

6.1.3 Are DFID’s spending allocations at country level and the selected programmes’ design and objectives responsive to intended beneficiary needs and to the context, including the key challenges of operating in fragile states and the need to address core drivers of fragility?

6.1.4 Are DFID’s spending allocations at country level and selected programmes well designed, with appropriate choices of partnerships, funding and delivery options, bearing in mind the challenges of fragile states and the potentially weak capacity of partners?

6.1.5 Do DFID’s spending allocations, at country level and for the selected programmes, complement the efforts of government and other aid providers and avoid duplication?

6.2 Delivery

6.2.1 Is there evidence of ‘doing things differently’ in terms of programming and delivery approaches, in line with DFID’s commitments?

6.2.2 Is DFID adequately addressing the challenges of programming and delivery in fragile states, including the weaknesses of local systems and capacity of partners?

6.2.3 Is DFID able to make appropriate programming decisions that make effective use of its increased resources?

6.2.4 Do the programmes actively involve intended beneficiaries and take their needs into account during implementation?

6.2.5 Is there good governance at all levels, with sound financial management and adequate measures to avoid corruption?

6.2.6 Are DFID’s spending allocations, at country level and for the selected programmes, leveraging resources and working holistically alongside other donor programmes?

6.2.7 Is robust programme management in place, taking account of the specific local challenges, to ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of the delivery chain?

6.2.8 Are the delivery arrangements flexible enough to respond to the specific risks, opportunities and changing circumstances of fragile states and has this, in fact, occurred?

6.2.9 Are there mechanisms for ongoing contextual analysis and understanding of drivers of fragility to inform evaluation, lesson learning and flexible and rapid refocussing of the programme to meet changes in the country context?

6.3 Impact

6.3.1 Are there appropriate arrangements for monitoring inputs, processes, outputs, results and impact? Are the views of intended beneficiaries taken into account?

6.3.2 Have the selected programmes delivered or are they likely to deliver their planned results?

6.3.3 Are DFID’s spending allocations centrally, at country level and for the selected programmes maximising impact for the intended beneficiaries, including women and girls?

6.3.4 Are the results and impact of the selected programmes likely to be long-term and sustained in a way that addresses the drivers of fragility?

6.4 Learning

6.4.1 Is there transparency and accountability to intended beneficiaries, UK taxpayers and other parties with a direct interest in the selected programmes?

6.4.2 Is there evidence of DFID learning from challenges and failures and identifying and sharing lessons from approaches that have not worked in practice?

6.4.3 Is there evidence of innovation and use of global best practice in fragile states programming?

6.4.4 Is there anything currently not being done in respect of the programmes that should be undertaken?

6.4.5 Have lessons about the objectives, design and delivery of the programmes been learned and shared effectively across the organisation and its partners?

7. Methodology

7.1 The methodology for this review will be developed during the inception phase. We have outlined below what aspects the methodology for this review is likely to include.

Desk Review

- a review of DFID’s strategies, policies and guidance which are related to or directly accompanied scale-up. These will include, for example, human resourcing strategies, risk strategies and fiduciary guidance;

- a review of DFID’s spending allocation processes and their links with DFID’s country office operational plans and business cases; and

- a review of DFID documentation outlining spending requests versus actual commitments in fragile countries since 2010-11 (the baseline in Figure 1) and, with it, choice of interventions.

Country visits

- we envisage two or three country case studies, with one likely to be desk-based (probably Somalia or Yemen);

- country visits will entail: a review of DFID’s overall spending decisions and their relevance to the country context; and, on the delivery side, a review of DFID’s delivery choice and safeguard mechanisms in place; and

- field visits will take place to meet with delivery partners and beneficiaries of the selected programmes. The capacity of implementing partners to absorb DFID’s planned spending will be assessed, as well as the impact/potential impact of the programme.

7.2 There are a number of challenges and limitations to consider for this review. Notably, given some of the modes of operation in fragile states, it may not be possible to separate DFID’s contribution from those of other donors. Security concerns may also restrict our choice of destinations for the field visits.

7.3 This review is ambitious, covering aspects from strategic resource allocation decisions made at HQ to details of programme delivery to beneficiaries. The focus is on the robustness and rigour of the decision-making cycle and the systems that support this – which will be illustrated through the case studies. The overall Green-Amber-Red rating will focus on our findings at a country programme level to illustrate the efficacy of DFID-wide systems issues, including central allocation and decision making. This review, however, will not attempt to rate the individual programme interventions that are selected as case studies.

7.4 The range of stakeholders to be interviewed is as follows:

London-based Interviews

These interviews will be carried out both before the start of the country-based studies and after the country visits, to follow up some issues identified as a result:

- senior DFID staff responsible for fragile states, to understand overarching strategy, desired impact and success of strategy;

- DFID staff and consultants who worked on the design and implementation of fragile states strategy; and

- third party experts in the UK and overseas (mainly by telephone conference).

In-Country Interviews

As part of the review process, we will conduct a range of interviews with stakeholders and intended beneficiaries to include:

- DFID staff and consultants responsible in-country for the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of programmes in fragile states;

- staff of partner organisations implementing DFID bilateral or multilateral projects;

- other donors and development actors;

- intended beneficiaries; and

- governments (where possible) and other country stakeholders.

8. Timing and deliverables

8.1 The review will be overseen by Commissioners and implemented by a small team from ICAI’s consortium. The lead Commissioner will be Mark Foster.

8.2 The review will start in January 2014, with a final report available in Autumn 2014.

Annex: Table showing DFID budget allocations from baseline (2010-11) to planned scale-up (2014-15) and annual percentage change21,22,23,24

| Country | 2010-11 | Percentage Change 2010-11 to 2011-12 | 2011-12 | Percentage Change 2011-12 to 2012-13 | 2012-13 | Percentage Change 2012-13 to 2013-14 | 2013-14 | Percentage Change 2013-14 to 2014-15 | 2014-15 | Percentage Change baseline 2010-11 to planned scale-up 2014-15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 178,000 | 0% | 178,000 | 0% | 178,000 | 0% | 178,000 | 0% | 178,000 | 0% |

| Bangladesh | 157,000 | 22% | 200,000 | 5% | 210,000 | 28% | 290,000 | 3% | 300,000 | 91% |

| Burma | 32,000 | 11% | 36,000 | 0% | 36,000 | 35% | 55,000 | 5% | 58,000 | 81% |

| Burundi | 12,000 | -20% | 10,000 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | -100% |

| DRC | 133,000 | 10% | 147,000 | 11% | 165,000 | 25% | 220,000 | 15% | 258,000 | 94% |

| Ethiopia | 241,000 | 17% | 290,000 | 3% | 300,000 | 13% | 345,000 | 12% | 390,000 | 62% |

| *Iraq | 10,000 | -100% | 5,000 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | -100% |

| Kenya | 86,000 | 14% | 100,000 | 9% | 110,000 | 27% | 150,000 | 0% | 150,000 | 74% |

| **Liberia | 10,000 | -25% | 8,000 | 0% | 8,000 | 0% | 8,000 | 0% | 0 | -100% |

| Malawi | 72,000 | 20% | 90,000 | 0% | 90,000 | 5% | 95,000 | 3% | 98,000 | 36% |

| Nepal | 57,000 | 5% | 60,000 | 0% | 60,000 | 40% | 100,000 | 3% | 103,000 | 81% |

| Nigeria | 141,000 | 22% | 180,000 | 14% | 210,000 | 31% | 305,000 | 0% | 305,000 | 116% |

| *OPTs | 74,000 | 13% | 85,000 | 0% | 85,000 | 0% | 85,000 | 3% | 88,000 | 19% |

| Pakistan | 215,000 | 19% | 267,000 | 0% | 267,000 | 35% | 412,000 | 8% | 446,000 | 107% |

| Rwanda | 70,000 | 7% | 75,000 | 6% | 80,000 | 6% | 85,000 | 6% | 90,000 | 29% |

| Sierra Leone | 54,000 | 7% | 58,000 | 0% | 58,000 | 25% | 77,000 | 0% | 77,000 | 43% |

| Somalia | 26,000 | 41% | 44,000 | 4% | 46,000 | 43% | 80,000 | 0% | 80,000 | 208% |

| South Sudan | 100% | 89,000 | 2% | 91,000 | 5% | 96,000 | 3% | 99,000 | 0% | |

| Sudan | 132,000 | -159% | 51,000 | -4% | 49,000 | -11% | 44,000 | -7% | 41,000 | -69% |

| Uganda | 90,000 | 10% | 100,000 | 5% | 105,000 | -11% | 95,000 | -6% | 90,000 | 0% |

| *Yemen | 50,000 | 23% | 65,000 | 7% | 70,000 | 13% | 80,000 | 11% | 90,000 | 80% |

| Zimbabwe | 70,000 | 13% | 80,000 | 5% | 84,000 | 11% | 94,000 | 1% | 95,000 | 36% |

Footnotes

- Reducing poverty by tackling social exclusion: a DFID policy paper, DFID, 2005, http://www2.ohchr.org/english/issues/development/docs/socialexclusion.pdf.

- Stop Conflict, Reduce Fragility and End Poverty: Doing Things Differently in Fragile and Conflict-affected Situations, World Bank, 2013, http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/Feature%20Story/Stop_Conflict_Reduce_Fragility_End_Poverty.pdf.

- Twelfth Report, Working Effectively in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States: DRC and Rwanda, IDC, 2011, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmintdev/1133/113302.htm.

- Fragile States, Working Paper 51 Centre for Research on inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity, January 2009, http://economics.ouls.ox.ac.uk/13009/1/workingpaper51.pdf.

- Evaluation of the Inter-Departmental Conflict Pool, ICAI, July 2012, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Evaluation-of-the-Inter-Departmental-Conflict-Pool-ICAI-Report.pdf.

- Bilateral Aid Review: Technical Report, DFID, 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/214110/FINAL_BAR_20TECHNICAL_20REPORT.pdf.

- A New Deal for engagement in fragile states, 2011, http://www.newdeal4peace.org/wp-content/themes/newdeal/docs/new-deal-for-engagement-in-fragile-states-en.pdf.

- Working Effectively in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States: DRC and Rwanda, IDC, January 2012, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmintdev/1133/113302.htm#evidence.

- Building Peaceful States and Societies, DFID, 2010, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67694/Building-peaceful-states-and-societies.pdf.

- Chapman, N and Vaillant, C., Synthesis of country programme evaluations conducted in fragile states, February 2010, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67709/syn-cnty-prog-evals-frag-sts.pdf.

- Evaluation of the Inter-Departmental Conflict Pool, ICAI, 2012, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Evaluation-of-the-Inter-Departmental-Conflict-Pool-ICAI-Report.pdf.

- DFID: Programme Controls and Assurance in Afghanistan, ICAI, 2012, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ICAI-Afghanistan-Final-Report_P1.pdf.

- DFID’s Approach to Anti-Corruption, ICAI, 2011, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/DFIDs-Approach-to-Anti-Corruption.pdf.

- DFID’s Bilateral Support to Growth and Livelihoods in Afghanistan, ICAI, March 2014, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/ICAI-Report-DFID’s-Bilateral-Support-to-Growth-and-Livelihoods-in-Afghanistan.pdf.

- DFID’s Work with UNICEF, ICAI, March 2013, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ICAI-report-DFIDs-work-with-UNICEF.pdf.

- Humanitarian Emergency Response to the Horn of Africa, ICAI, September 2012, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ICAI-report-FINAL-DFIDs-humanitarian-emergency-response-in-the-Horn-of-Africa11.pdf.

- Chapman, N and Vaillant, C., Synthesis of country programme evaluations conducted in fragile states, February 2010, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67709/syn-cnty-prog-evals-frag-sts.pdf.

- These include: Afghanistan, Cambodia, Nepal, Pakistan, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, DRC, Sudan and Yemen.

- Working Effectively in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States: DRC and Rwanda, IDC, January 2012, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmintdev/1133/1133we02.htm.

- Bilateral Aid Review: Technical Report, DFID, 2011. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/214110/FINAL_BAR_20TECHNICAL_20REPORT.pdf.

- Twelfth Report, Working Effectively in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States: DRC and Rwanda, IDC, 2011, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201012/cmselect/cmintdev/1133/113302.htm.

- These are scale-up plans as set out by DFID at 2010.

- We have excluded Tajikistan as it is part of a broader budget allocation for Central Asia. Budget allocations for Central Asia are £14 million in each of 2011-12, 2012-13, 2013-14 and 2014-15. (Total: £56 million); *Country Plans not published externally, **The Liberia programme reviewed after the elections in 2012.