DFID’s Support for Civil Society Organisations through Programme Partnership Arrangements

Executive Summary

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review.

Green: The programme performs well overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Some improvements are needed.

Green-Amber: The programme performs relatively well overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Improvements should be made.

Amber-Red: The programme performs relatively poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Significant improvements should be made.

Red: The programme performs poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Immediate and major changes need to be made.

This report examines the Department for International Development’s (DFID’s) Programme Partnership Arrangements (PPAs) – one of the principal mechanisms through which it funds civil society organisations (CSOs).1 In the current funding round (2011-14), DFID will provide a total of £120 million a year to 41 organisations, with grants ranging from £151,000 to £11 million. Through the PPAs, DFID supports CSOs that share its objectives and have strong delivery capacity. It provides CSOs with ‘unrestricted’ funding, giving them the flexibility to follow agreed strategic priorities. We assess the effectiveness and value for money of the PPA instrument, looking at partner selection, reporting and accountability. We comment in particular on six case study CSOs.

Overall

Assessment: Green-Amber

We recognise that a vibrant civil society sector is an essential part of the UK aid landscape. While it is too early to conclude on the overall impact of the current funding round, we identify that PPAs are helping to drive innovation in the recipient organisations. In particular, they are improving the quality of performance management and accountability for results. We think it is likely that these changes will lead to improved results for intended beneficiaries, not just from PPA funding but across the CSOs’ full range of activities. We conclude, however, that DFID would achieve more with its PPAs if it were to refocus on the added value they can provide as a strategic instrument, in particular when contrasted with the other CSO funding mechanisms that DFID uses.

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

Uncertainty on policy within DFID during implementation led to objectives being unclear for this round of the PPAs. DFID should have been more explicit about what it hoped to achieve with the PPA instrument and then more strategic with its selection of CSOs. First, it should have identified which corporate priorities it wanted the PPAs to support. It should then have used a competitive grant-making process designed to maximise that contribution, with fair and transparent competition. It is notable that DFID set funding levels based on an assessment of CSOs’ capacity and not the expected contribution of each PPA to DFID’s results.

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

DFID has placed a strong emphasis on making CSOs accountable for the delivery of PPAs, which has helped to improve their performance. DFID could have done more, however, to engage with CSOs on shared objectives. We are concerned that the PPAs have not, in practice, operated as partnerships. DFID failed to define what it hoped to gain from working with CSOs and, as a result, has gained less than it might have done. In particular, the CSOs’ knowledge, influence and expertise could be adding further value to DFID’s work.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

While it is too early to conclude on the impact of the current PPAs on intended beneficiaries and linking of strategic flexible funding with improved impact is difficult to verify at this stage, the prospects appear to be good. The CSOs we examined appear to be on track to deliver their expected results. This round of PPAs has helped to bring about a major and positive shift in the way that CSOs focus on results. The PPAs are also enabling improvements to CSOs’ governance, financial management and delivery.

Learning

Assessment: Amber-Red

DFID’s approach to monitoring and evaluation has been overly complex and poorly adapted to the strategic nature of the PPAs. Scrutiny has at times been disproportionate and CSO monitoring could usefully involve beneficiaries more. We are concerned that DFID is not obtaining best value from the contractor appointed to evaluate PPA performance (albeit DFID’s specification of the task was complex, making achievement difficult). On the other hand, the Learning Partnership has proved highly effective at promoting joint learning and innovation, to the benefit of both PPA holders and the wider community of development CSOs. On its own, the Learning Partnership would score well (a Green).

Key recommendations

Recommendation 1: If DFID decides to continue with PPAs, or a similar grant-making instrument, it should use the intervening period to develop a more strategic, transparent and fair process for selecting CSOs and allocating funding. DFID should consider, both for this round and for any future rounds, extending the PPAs to more than three years to allow the strategic and innovative aspects of this unrestricted funding to develop.

Recommendation 2: DFID should assign a technical counterpart to each PPA to ensure that both it and CSOs obtain full value from the partnership.

Recommendation 3: DFID should re-design the monitoring and evaluation system for PPAs so that it is less cumbersome and better suited to the long-term strategic nature of this funding.

Recommendation 4: DFID should strengthen the role of the Learning Groups, in order to ensure that lessons learned are shared more widely within DFID and with civil society partners.

1 Introduction

1.1 This review considers the Department for International Development’s (DFID’s) £120 million annual funding of civil society organisations (CSOs2) through 41 Programme Partnership Arrangements (PPAs). It considers the performance of the grant-making mechanism as a whole and in respect of six case studies: Christian Aid; Action Aid; WWF; a consortium led by Restless Development; Conciliation Resources; and the Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI).3 This represents a spread of large, medium and small organisations with a variety of specialisations and focusses.

1.2 The present round of PPA funding began in 2011 and is intended to run until 2014. While it is too early to draw conclusions as to the impact of the current PPAs, there is evidence on which we can assess their prospects for success. PPAs are not a new mechanism. DFID has been funding through PPAs since 2000; four out of our six case study CSOs have previously held PPAs.4 While this evaluation is primarily concerned with the current round, it also draws on learning from PPAs since 2000.

1.3 In this review, we do not offer an overall judgement on the merits of PPAs as a type of assistance, as it is not our remit to make recommendations on policy. The purpose of this evaluation is to assess the delivery, effectiveness and impact of DFID’s PPAs, with a view to improving implementation of the current round and helping to shape any similar CSO funding instrument in the future. We concentrated on DFID’s decision-making processes, on the quality of its performance management and on the impact of PPA funding.

CSOs working with DFID

The role of CSOs in international development

1.4 Civil society is a vital actor in international development. An important share of global aid flows is spent through CSOs. CSOs play several key roles in the development process. In a 2006 report, the National Audit Office (NAO) concluded that CSOs strengthen the voice of the poor, promote awareness in the UK of development issues, advocate for change, hold governments to account, provide humanitarian assistance, deliver services and build capacity in developing countries.5

1.5 The UK has a particularly vibrant community of CSOs active in development.6 They relate to DFID in different ways, which sometimes overlap:

- Delivering programmes: DFID engages CSOs to deliver programmes across the world, usually through direct grants but also, on occasion, through a competitive tender;

- As partners: DFID and CSOs work as partners in pursuit of joint objectives, such as the global campaigns to eradicate landmines and polio.7 DFID supports CSOs (such as Conciliation Resources) that can work in areas that other agencies (for instance governments) can find hard to access. They collaborate on generating knowledge and developing policy. Restless Development and Christian Aid, for example, have both worked with DFID on the development of the successor to the Millennium Development Goals after 2015; and

- As challengers: CSOs continuously lobby DFID and the UK Government, as well as recipient governments, for changes to policy. Christian Aid, for example, is campaigning for more action on corporate tax avoidance.8 DFID reports that it received over 100,000 letters, emails and petition signatures from the public in 2012, many as a result of CSO campaigns.9

CSOs have multiple entry points to DFID

1.6 DFID’s Civil Society Department (CSD), predominantly based in East Kilbride within the Policy and Research Division, is responsible for DFID’s overall policy towards CSOs.10 CSD and the Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department (CHASE), based in London, oversee most of the funding that DFID provides centrally to CSOs, including through PPAs.

1.7 These are not, however, the only points of contact between DFID and CSOs. One CSO might relate to many different DFID departments and staff, both centrally and in country offices. This is particularly the case for large international CSOs with multiple interests.

CSOs are an important funding channel for DFID

1.8 DFID spent at least £694 million through CSOs in 2011-12 (see Figure A1 in the annex). DFID staff informed us that the total is likely to be higher, since projects funded primarily through other channels (e.g. partner governments or multilateral organisations) may not report on the proportion of funds spent through CSOs.

1.9 There are two main channels within DFID for this spending:

- DFID country offices: of the £327 million spent through CSOs in 2011-12 by DFID’s country offices, £154 million went to Africa, £102 million to South Asia and the remaining £71 million to other countries (Pakistan, Afghanistan, Libya and Yemen); and

- DFID headquarters: each year, DFID central departments oversee £367 million spending through CSOs. DFID’s Policy and Research Directorate accounts for £265 million, of which the majority (£201 million) is managed by CSD, including £120 million in annual funding for PPAs.

1.10 PPAs are, therefore, DFID’s largest central funding channel for CSOs. Figure A2 in the annex lists all centrally administered funding mechanisms used by DFID.

Programme Partnership Arrangements

Flexible funding to CSOs

1.11 DFID funding to CSOs falls into two categories. Using terminology from UK charities law, these are:

- restricted funds, which can only be used for a named purpose;11 and

- unrestricted funds (also called ‘core funds’), which can be used as flexible funding at the discretion of the CSO.12

1.12 It will be noted that the majority of the funding arrangements set out in Figure A2 in the annex are for restricted funding, whereas the PPAs (and the Strategic Grant Agreement for VSO) are for unrestricted funding.

1.13 Since the 1990s, DFID (and its predecessor, the Overseas Development Administration) has provided unrestricted funds to a small number of CSOs that were seen as strategic partners. Predictable and flexible finance was seen as a means of supporting their organisational development and allowing them to pursue their own development priorities. From 2000, these block grants developed into PPAs, with a typical length of 3 to 4 years. These are now in their fourth round of funding (2011-14).

1.14 In principle, the value of an unrestricted funding instrument like a PPA is that it strengthens CSOs’ capacity. Flexible funding enables CSOs to set their own priorities and to develop their own areas of comparative advantage. It fosters risk-taking and innovation, allowing them to pilot untested initiatives that donors might not wish to fund directly.13 It enables them to invest in their own organisational development, including their governance and management structures, their fundraising capacity and their systems for learning. According to CSOs, it is very difficult to cover any of these items through conventional, restricted funding. Although it may take time, these strategic changes are expected to lead to improved impacts for intended beneficiaries.

1.15 Unrestricted funding also, in principle, allows for a different kind of relationship between donor and recipient. It demonstrates a level of trust by DFID in the CSOs’ mission, integrity and capacity, allowing for a more genuine partnership. Potentially, it enables DFID to influence the overall strategy and programming choices of the recipient, thereby influencing a much larger pool of funding. It also gives DFID a basis on which to influence CSOs’ organisational development – for example, by sharpening their focus on achieving concrete results.

1.16 DFID does not generally deliver aid itself, using others, such as CSOs, to do so. Channelling funding through CSOs enables the reach of UK aid to be extended. In particular, CSOs will often have infrastructure and delivery capabilities in fragile and conflict states, which are now a priority in DFID’s strategic approach.

1.17 While DFID’s criteria have changed over the years, PPAs have generally supported organisations that share DFID’s priorities and values, have high standards of corporate governance and offer an extensive reach in poor countries (or within the UK, for building support for development). These have usually, but by no means exclusively, been large CSOs. Small organisations are now equally capable of being eligible for such funding, to their and DFID’s potential benefit.

The current round of PPAs (2011-14)

1.18 The current round of PPAs began as DFID was seeking to measure results better and improve accountability. DFID’s thinking on these issues was evolving as it put the current PPAs in place. At the same time, there was a general uncertainty about the future of PPAs (see paragraphs 2.7 to 2.9 on page 8). Consequently, the 2011-2014 PPAs were subject to a variety of different emphases than their predecessors. Evidence from DFID’s documentation also indicates that the corporate expectations from these PPAs were subject to critical shifts as they were being put in place (see paragraph 2.11 on page 8).

1.19 A notable break from the past was that the 2011-14 round was the first in which CSOs openly competed for funds. Any CSO could apply, including those based outside the UK (again a first for this round). For the first time, DFID introduced two new independent layers: a due diligence process and an evaluation manager to assess CSO performance. It was also the case that the level of funding could be adjusted in the third year, depending on the level of achievement.

1.20 Figure 1 on page 5 lists the CSOs that were awarded PPAs for 2011-14. Of the £120 million total, £20 million is reserved for Conflict, Humanitarian, Security & Justice (CHSJ) PPAs, administered by CHASE.14 The remainder is for general PPAs. Four CSOs receive both General and CHSJ PPAs.

| Recipient | General PPA | Conflict, Humanitarian, Security and Justice PPA | Annual funding (£ million)15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxfam GB (Joint PPA) | ✓ | ✓ | 11.2 |

| Save the Children UK (Joint PPA) | ✓ | ✓ | 9.4 |

| International Planned Parenthood Federation | ✓ | 8.6 | |

| Christian Aid (Joint PPA) | ✓ | ✓ | 7.3 |

| Marie Stopes International | ✓ | 4.4 | |

| WaterAid | ✓ | 4.2 | |

| CAFOD | ✓ | 4.2 | |

| ActionAid | ✓ | 4.1 | |

| Plan UK | ✓ | 4.1 | |

| World Vision UK | ✓ | 3.9 | |

| International HIV/AIDS Alliance | ✓ | 3.9 | |

| Sightsavers | ✓ | 3.7 | |

| Transparency International (Joint PPA) | ✓ | ✓ | 3.4 |

| CARE International | ✓ | 3.2 | |

| GAIN | ✓ | 3.1 | |

| WWF UK | ✓ | 3.1 | |

| Farm Africa / Africa Now / Self-help Africa | ✓ | 3.1 | |

| Fairtrade Labelling Organisation | ✓ | 3.0 | |

| Practical Action | ✓ | 2.9 | |

| Restless Development / War Child / Youth Business International | ✓ | 2.8 | |

| HelpAge International | ✓ | 2.7 | |

| Malaria Consortium | ✓ | 2.7 | |

| Norwegian Refugee Council | ✓ | 2.5 | |

| Asia Foundation | ✓ | 2.4 | |

| Progressio | ✓ | 2.0 | |

| International Alert | ✓ | 1.7 | |

| Saferworld | ✓ | 1.7 | |

| British Red Cross | ✓ | 1.6 | |

| Avocats Sans Frontieres | ✓ | 1.5 | |

| Islamic Relief | ✓ | 1.2 | |

| ADD International | ✓ | 1.1 | |

| Penal Reform International | ✓ | 1.1 | |

| Conciliation Resources | ✓ | 1.0 | |

| Gender Links | ✓ | 0.6 | |

| Womankind Worldwide | ✓ | 0.6 | |

| Article 19 | ✓ | 0.5 | |

| CDA Collaborative Learning Projects | ✓ | 0.5 | |

| Ethical Trading Initiative | ✓ | 0.4 | |

| Development Initiatives | ✓ | 0.4 | |

| People in Aid | ✓ | 0.2 | |

| MapAction | ✓ | 0.2 | |

| Total | 120.2 |

Source: DFID financial reporting

Our approach

1.21 This evaluation looked in detail at the six PPA recipients shaded in Figure 1. These were chosen as broadly representative of the types and size of CSOs currently funded through PPAs.

1.22 DFID’s documentation shows some changes in emphasis in its objectives for PPAs over time. We, therefore, used the justification for funding made to the Secretary of State in July 2010, as the key statement of intent to Ministers, to frame our discussion of the PPAs’ achievements (see paragraph 2.11 on page 8).

1.23 We have drawn on a range of other relevant reviews, such as:

- a 2006 NAO report;16

- evaluations of previous rounds of PPAs (both individual grants and the mechanism as a whole);

- annual review reports from individual PPA recipients;

- Independent Performance Reviews (IPRs) of each of the PPAs undertaken in 2012; and

- a mid-term review prepared in 2012 by Coffey, DFID’s independent evaluation manager, assessing performance to October 2012.

1.24 Given the wealth of existing review material (the IPRs alone ran to over 5,300 pages), our evaluation methodology was designed to build on existing knowledge. It sought to avoid unnecessary additional burden on DFID or the CSOs in a process that has already been heavily scrutinised by DFID’s contractors over the course of 18 months.

1.25 For each of our six case study CSOs, we interviewed representatives and assessed their programme management capacity, focussing in particular on financial reporting.

1.26 We interviewed DFID staff, consultants who had undertaken IPRs, DFID’s independent evaluation manager, the NAO and a range of informed observers. We met with representatives of CSOs who benefit from PPAs but are not case-study organisations and also with others who failed to obtain PPAs in the 2011-14 round.

1.27 Investigative work for this review was undertaken by Agulhas Applied Knowledge, one of the organisations in ICAI’s contractor consortium, under direct contract to ICAI. ICAI’s lead contractor, KPMG, had provided due diligence assessments to DFID for these PPAs and was, therefore, excluded from any involvement in this report.

1.28 This study took place in parallel with ICAI’s review of DFID’s use of contractors to deliver programmes. That report covers, as one of its case studies, KPMG’s contract with DFID during 2010-13 to provide due diligence for CSOs. We used Concerto LLP, not our contractor consortium, to undertake that review.17 The two investigative teams shared information and co-ordinated findings.

2 Findings

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.1 In this section, we examine the strategy behind DFID’s use of PPAs. We discuss DFID’s lack of clarity of purpose for this round of PPA funding. We also note how DFID did not explicitly match its strategic objectives to those of the grantees and how the process of CSO selection left room for improvement.

DFID’s design of the PPA instrument

DFID’s objectives for its work with CSOs

2.2 DFID has five overarching corporate objectives for its work with CSOs. These are that CSOs:

- ‘deliver goods and services effectively and efficiently;

- empower citizens in developing countries to do things for themselves;

- enable civil society to influence, advocate and hold to account national, regional and international institutions including improving aid effectiveness;

- build and maintain capacity and space for active civil society; and

- build support for development in the UK.’18

DFID sought to use PPAs as a complementary mechanism to other approaches

2.3 The PPAs were developed as one funding channel that DFID could use to support CSOs to achieve these objectives. PPAs were seen by DFID as having particular added value over other, more restricted funding mechanisms. They were complementary and distinctive from grants that were narrowly focussed on achieving specific deliverables.

2.4 The NAO acknowledged such potential advantages of PPAs in its 2006 report, finding that they ‘offer the prospect of a more strategic approach to long-term development challenges, better co-ordination and reduced transaction costs – where they can be based on well-specified and monitorable strategic objectives’.19 It noted that the benefits can include greater predictability, flexibility and reduced administration costs for both DFID and the recipient. A report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) also commends the way that DFID’s PPAs allow recipients to ‘focus on strategic and substantive issues instead of constantly chasing funds’.20 PPAs were thus inherently intended to be a mechanism that encouraged freedom and innovation.

The use of PPAs has merit but is unproven

2.5 There is, however, nothing automatic about the benefits of unrestricted funding. Whether benefits are achieved largely depends on the design of the PPAs and on the quality of the partnership they create. The 2006 NAO report also notes a number of potential disadvantages of unrestricted funding, in particular that DFID has less control over the use of the funds and finds it more difficult to assess their impact. Overall, the NAO concluded that the PPA mechanism is most likely to be ‘suitable for well established CSOs where DFID has assessed governance arrangements to be strong’.21

2.6 The NAO recommended that DFID review all its CSO funding mechanisms to identify ‘better evidence of the circumstances in which different approaches are likely to be best’.22 DFID undertook an internal portfolio review of its CSO projects in 2010 but was not able to find enough evidence to conclude on the comparative effectiveness of different civil society funding instruments. Nor was it able to conclude on the merits of civil society versus other funding channels. DFID therefore embarked on the current phase of PPAs believing, although without clear evidence, that the mechanism worked to improve aid effectiveness.23

Altered corporate priorities affected the PPA’s strategic direction

2.7 Following the change of government in 2010, the then Secretary of State for International Development indicated that the 2011-14 round of PPA funding would be the last (a final decision on this remains pending). His preference was for restricted funding linked more closely to specific outputs and outcomes, emphasising the importance of holding CSOs accountable for their use of public funds.

2.8 This shift in policy direction brought some clear benefits to the design of the current PPAs. It sharpened the focus of both DFID and PPA recipients on the need for greater rigour in measuring results.

2.9 It also created an uncertain policy context for the current round of PPAs. This produced a lack of clarity about the use of unrestricted funding and the medium-term future of the approach. This, in turn, affected the coherence of the instrument.

DFID failed to design the PPAs around clear development objectives

2.10 We note that DFID does not appear to have used its corporate results framework (set out in Figure 2) to set priorities for this round of PPAs. This was published in December 2010, prior to the agreements being finalised with CSOs. DFID uses this framework to manage and report on its results. It was developed while DFID was putting in place the PPAs. We would have expected the two processes to be co-ordinated. DFID did not consistently set out what development outcomes or results it wanted the funding of CSOs through PPAs to support.

2.11 We have seen a range of documents setting out different objectives for PPAs at different times. The most authoritative of these was a submission to the Secretary of State in July 2010, on which the approval to implement this round of PPAs was given. We have, therefore, used this as the key statement of DFID’s intent against which to frame our comments on the PPAs’ impact. It stated that the 2011-14 round of PPA funding would focus on four key areas:

- Innovation: encouraging CSOs to test and scale up new ideas;

- Results: supporting CSOs with monitoring and evaluation systems and the ability to demonstrate results and value for money;

- Efficiency: supporting CSOs to lead reform, put into practice high standards of transparency and demonstrate efficiency; and

- Leverage: supporting partners to drive improvements and set high standards of excellence across the CSO sector.

| Level 1: Progress on key development outcomes | |

|---|---|

| MDG1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger MDG2: Achieve universal primary education MDG3: Promote gender equality & empower women MDG4: Reduce child mortality MDG5: Improve maternal health MDG6: Combat HIV&AIDS, malaria & other diseases MDG7: Ensure environmental sustainability |

|

| Level 2: DFID Results | |

| Bilateral programme results, set out under the 'pillars' of wealth creation, poverty, vulnerability, nutrition and hunger, education, malaria, reproduction, maternal and neo-natal health, water and sanitation, humanitarian and emergency response, governance and security, climate change. Multilateral programme results set out under the 'pillars' of wealth creation, poverty, vulnerability, nutrition and hunger, health, education, water and sanitation, infrastructure, humanitarian. |

|

| Level 3: Operational Effectiveness | |

| Portfolio quality Pipeline delivery Monitoring and Evaluation Performance against DFID's structural reform plan |

|

| Level 4: Organisational Effectiveness | |

| Human resources Employee engagement Workforce diversity Finance Procurement Estates |

Source: DFID Results Framework, DFID, 201024

2.12 We think that these objectives have merit. DFID is a funder, not a deliverer, of aid. These objectives are seeking to improve the quality of DFID’s aid delivery. The PPA mechanism enables DFID to align with CSOs as important deliverers of aid, supporting their innovation and capacity building. The objectives do not, however, set out what development outcomes DFID wanted PPAs to support. These were left for the CSOs themselves to define (see paragraph 2.26 on page 10).

2.13 Within DFID’s corporate results framework (set out in Figure 2 on page 8), the objectives set out above could be seen to fall in level 3 under the headings of ‘Portfolio Quality’ and ‘Monitoring and Evaluation’. The logic of DFID’s results framework is that improving the quality of DFID-funded aid will, in turn, contribute to improving DFID’s results and global development outcomes.

2.14 Our view is that DFID should have been more explicit about what it hoped to achieve with the PPA instrument. It should have identified which corporate results and outcomes it wanted the PPAs to support in order to improve the targeting of funds. Consequently, we think that DFID failed to ensure that the design maximised the potential benefits of this type of funding.

DFID did not set out clearly how PPAs enable CSOs to deliver more effectively

2.15 DFID did not set out a clear ‘theory of change’25 or programme logic for how the PPAs would contribute to improving the quality of delivery and, in turn, to improved development results. While DFID did not formally require a theory of change until January 2011, we expect any expenditure of public money to be based on a logical and clear justification. In fact, the causal chain from improving how CSOs operate to development impact is long and complex, with multiple links that are difficult to observe and verify. This makes it all the more important that the assumptions are made clear, so that the instrument can be managed appropriately and its results tested. The absence of a theory of change or programme logic was, therefore, a significant omission.

2.16 After the PPA awards had been made, DFID sought to address this gap by hiring an independent evaluation manager, Coffey International Development, appointed in January 2011. Its role has included the drafting (in consultation with DFID and CSOs) of two high-level theories of change. These are framed as questions, concerning (a) why DFID should support civil society; and (b) how DFID should fund CSOs. Coffey is testing hypotheses that may enable it to answer these questions, using evidence both from the PPAs and from DFID’s Global Poverty Action Fund. Given the sequence of events set out above, this process could only provide a retrospective justification for DFID’s current work with CSOs.

2.17 The lack of clarity on how PPAs would work resulted in some unresolved tensions between objectives. Coffey’s Mid-Term Review of the PPAs notes, in particular, the challenge of DFID demanding concrete results while also seeking to drive innovation. Our view is that innovation necessarily involves risk and uncertainty and concrete results cannot be guaranteed in the short term.

Objective-setting and funding decisions for organisations

The competitive process for choosing partners left scope for improvement

2.18 In 2006, the NAO recommended that selection of grantees should include ‘greater use of competition by specifying the changes [DFID] wants to engender, and letting CSOs bid for associated support’.26 DFID responded to this only in part. It introduced a competitive application process but without first identifying the specific goals it wanted to achieve or how much funding was available to each organisation. Instead, it was left to CSO applicants to identify the objectives in limbo.

2.19 DFID put in place a two-stage application process: following an initial concept note, short-listed applicants were invited to submit a detailed proposal. The issues they were asked to address in their applications are set out in Figure 3.

Step 1: Concept Note

DFID invited initial applications for PPAs on 10 August 2010. CSOs were asked to justify why they should receive PPA funding under the following headings:

- benefit to DFID of funding through a strategic partnership;

- fit with DFID’s values and priorities;

- policy engagement with DFID or similar organisations at international level;

- leadership role of the organisation in its sector;

- main achievements; and

- specialist role in development.

Over 450 CSOs submitted concept notes.

Stage 2: Proposal

DFID then invited 109 short-listed applicants to submit proposals for why they should be funded, addressing the following criteria:

- strategic fit with DFID;

- partnership behaviour;

- vision and impact;

- monitoring, evaluation and learning;

- results delivery;

- institutional capacity;

- value for money; and

- transparency and accountability.

Proposals also included a provisional logical framework, identifying likely outputs.

2.20 All applicants went through a single assessment process. While we agree that an element of competition was useful, it is surprising that a small organisation such as the Ethical Trading Initiative (income £1.6 million) should be assessed through the same process as an organisation the size of Christian Aid (income £95.5 million).

2.21 The assessment was based only on documents submitted. DFID’s assessors were told not to use their prior knowledge of the organisation to avoid privileging previous PPA holders. This appears to be a rather artificial mechanism for achieving a level playing field. We would have expected DFID to use all the information available to it about the applicants, including past PPA or project performance (whether funded by DFID, for instance via country offices where a reported £327 million was spent on CSOs in 2011-12, or by other donors), governance (including an assessment of leadership) and future potential.

2.22 DFID did not meet with representatives from applicant organisations at any time during the process. DFID informed us that this was due to resource constraints.

2.23 The time frames for the application process were short (see Figure 7 on page 14). According to several CSOs, this adversely affected the quality of their applications. Respondents from organisations with a long-standing relationship with DFID told us they found the application process easier. They felt that they were able to match the wording of their applications more closely to DFID’s expectations.

The selection process involved a mixture of objective and discretionary elements

2.24 DFID scored CSOs based on their applications. The resulting ranking was then adjusted in order to balance the selection across ‘niches’ or programming areas.27 DFID also sought to ensure strategic fit (we could find no criteria for assessing that), geographical representation and inclusion. A shortlist (with indicative funding) was then put to the Secretary of State, leading (after some further modification) to the final selection.

2.25 The process of modifying the overall list to achieve ‘balance’ allowed an element of discretion. Some lower-ranked organisations were included in the final selection, while some former PPA recipients with higher scores were excluded. If DFID had used the lowest score of the CSOs it finally funded as the base level, an additional 13 CSOs would have received PPAs.

DFID retrospectively identified which development outcomes individual PPAs should support

2.26 In their applications for PPAs, CSOs were asked to set out their objectives in the form of a logical framework.28 These were then finalised during 2011 and incorporated into the grant agreements. Only at this stage did DFID begin to match individual PPAs with its particular strategic priorities. DFID’s expected results from the PPA round were, therefore, built from the bottom up, through decisions on individual applications, rather than as part of an overall strategy (see Figure 4 for illustrative results for the case study CSOs).29

Christian Aid (Chase PPA only)

- Communities better prepared to anticipate/reduce risks and respond to disasters.

- Local stakeholders actively participate in policy discussions on Hyogo framework,30 advocating for and influencing improved enabling environment for resilience.

- Beneficiaries develop resilient livelihoods and safety nets, with reduced vulnerability to shocks and hazards.

- Christian Aid puts into practice, tests and evaluates a consolidated multi-hazard/context, disaster reduction policy, framework and guidelines.

Action Aid

- Women’s groups strengthened to contribute to planning and integration of national strategies to support women’s rights.

- Community leaders and government trained to support women to effectively access/exercise rights.

- CSOs and farmers’ groups established/strengthened to develop effective food security policies.

- Organisation and skills of poor farmers strengthened to promote access to productive assets and climate resilient practices.

- CSOs trained to demand greater accountability and transparency from governments and effectively monitor budgets and decision-making processes.

- Government officials trained on accountability and transparency to effect positive change in governance practices.

- Schools increase capacity to respect children’s rights and gender equality.

Conciliation Resources

- 20 peacebuilding organisations receive capacity-building support.

- Support provided to ensure exchanges and/or dialogues generate new ideas and provide opportunities for constructive relations.

- Influence government and multilateral policies and practices to promote alternatives to violence that reflect local interests/rights.

- Media activities and resources raise public awareness of peace and conflict issues and challenge widely held stereotypes.

Ethical Trade Initiative

- Collaboration between businesses, CSOs and government to improve working conditions in prioritised supply chains.

- Poor and vulnerable workers in prioritised supply chains better prepared to act on rights.

- ETI member companies operate in a way that supports improvements in working conditions in prioritised supply chains.

Restless Development

- Delivery of evidence-based programmes and services to critical mass of young people.

- Provision of technical support to critical mass of national youth CSOs.

- Sustained engagement with partners to work more effectively with and for young people on core strategies and business models.

- Capturing and disseminating best practice, replicable models and learning.

WWF

- Communities receive WWF training and/or participate in processes for equitable and adaptive safeguarding of ecosystems.

- Policy frameworks and practices relating to adaptation, REDD+31 and low carbon development that are climate-smart, environmentally sustainable and pro-poor, are identified, advocated and supported.

- Climate smart, socially and environmentally sustainable policies and practices for stakeholders investing in infrastructure and natural resources are identified, advocated and supported.

Source: PPA logical frameworks

2.27 Our view is that DFID should have set out which strategic priorities it wished the PPAs to contribute to first, then ensured that the individual CSOs’ objectives matched these. This would not have undermined the benefits of funding through an unrestricted mechanism; CSOs would have had full flexibility in defining how they supported such corporate objectives. This approach would, however, have ensured that PPA funding was more explicitly matched to what DFID prioritised. We note that DFID’s experts in the various programming areas were not generally involved in setting the objectives.

2.28 Many of the grantees went on to develop theories of change for their PPAs once they were already underway (for instance, in preparation for the 2012 Independent Performance Reviews). This involved revising their logical frameworks, in some cases several times. Through this process, individual CSOs have gradually achieved more clarity as to what they hope to achieve through their PPAs. The DFID evaluation manager has been tasked with aggregating these objectives into a set of theories of change for the instrument as a whole (see paragraph 2.16 on page 9).

2.29 The whole strategy-setting process has, therefore, been approached retrospectively to make up for the original lack of clarity. As the original goals of the PPA were not clearly identified, the instrument has not been designed in a strategic manner, to maximise the potential advantages of unrestricted funding of this type and to avoid the risks to effective delivery.

DFID’s funding decisions were not transparent, predictable or linked to results

2.30 The funding envelope for the 2011-14 PPAs was £120 million per year. DFID’s decision as to how to allocate these funds across the successful applicants was not based on clear and objective criteria (see Figure 5). The level of funding given to each CSO was not linked to the achievement of any defined set of results, nor was the process transparent to the participants. CSOs have told us that they have not been formally informed how their allocations were decided.

DFID determined the size of individual PPAs through a ‘resource allocation model’.32 The model began with a base level derived from each CSO’s annual income. It then adjusted this level based on the ratings that had been given to each applicant by DFID staff against the criteria of results delivery, value for money, partnership behaviour and evaluation and learning. A final stage allowed for other factors to be taken into account, leaving DFID the discretion to adjust the final funding level as it wished. An overall ceiling was imposed so that no CSO could receive more than 40% of its turnover, in order to reduce dependency on DFID.

2.31 Apart from setting a funding ceiling of 40% of a CSO’s turnover, DFID did not inform applicants what levels of funding were on offer, nor were CSOs asked to bid for a specific amount. There was no negotiation or discussion.

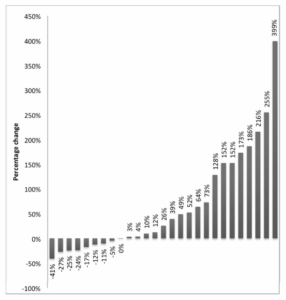

2.32 Figure 6 on page 13 shows the changes in annual funding for successful applicants that had also held PPAs under the previous round. Of these, 18 had their annual funding increased and 8 decreased, with an average increase of 67%. Eight CSOs had their allocation more than doubled. In some cases, funding was up to four times as large as CSOs had been expecting. In some cases it was less than the CSOs had planned for.

2.33 The lack of predictability on the scale of funding hampered CSOs’ ability to plan ahead. This was exacerbated by the grant process, in many cases, not corresponding with the CSOs’ own budget and planning cycles.

VSO was treated as a special case

2.34 DFID found additional unrestricted funding to allow it to accommodate Voluntary Services Overseas (VSO), an organisation that funds volunteer development work internationally. VSO had previously held a PPA with DFID worth £31.66 million in 2009-10, representing 59% of VSO’s total income that year. VSO applied for PPA funding under the 2011-14 round. There was a concern, however, that the ceiling of 40% of turnover represented a substantial reduction from its previous funding levels. There was direct lobbying from VSO and interest from MPs33 and VSO was removed from the PPA mechanism on 3 December 2010 (11 days before DFID’s deadline to notify its PPA applicants) and awarded a Strategic Grant Arrangement (SGA). This operates exactly as a PPA, allows for unrestricted funding and Coffey International includes VSO in its reporting of the operation of the PPA mechanism. It is structured to reduce further VSO’s dependence on DFID. The approval of VSO’s funding (£78 million) had the effect of increasing DFID’s overall unrestricted funding for CSOs by 22% for the period 2011-14. A smaller, restricted SGA of £543,520 was also awarded to the network organisation Bond, which was unsuccessful in its application for a PPA in the current round.34

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.35 As funder, DFID is not directly involved in the delivery of activities under the PPAs. In this section we look at the delivery of the funding mechanism itself, including the partnerships that were established with grantees.

Implementation

2.36 Figure 7 on page 14 sets out the timeframe over which the PPAs have been delivered to date. We note that CSOs were not informed clearly at the start of the process of all the key steps or timings, which in some cases affected their planning (particularly financial).

2.37 Our view is that this timing was too compressed at the initial stages. For instance, if compared with the rules for procurement that DFID usually abides by, the first stage of an open procurement should last at least 36 days (where there has been prior notice of the intended procurement).35 In this case, CSOs had 24 days (in August when many staff were away) to respond to DFID’s request for concept notes. As has been noted in the Objectives section, our view is that the sequencing of some of this process was also out of step, particularly the setting of individual PPA targets prior to the development of a theory of change.

Due diligence process contributed to organisational development

2.38 DFID informed applicants of its decision and how much they would receive on 14 December 2010. It then began a process of preparing grant agreements. Most organisations received their first funding in Summer 2011 (e.g. Christian Aid’s initial tranche arrived in August).

2.39 Finalisation of the grant documentation required an agreement on objectives, an environmental assessment and a ‘due diligence’ review of each applicant’s organisational capacity. Organisations had not been previously advised that these would form part of the approval process. The latter was DFID’s main tool for the risk management of each grant. DFID does not maintain a separate risk register for the PPA mechanism.

| Year | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 6 May | UK General Election |

| 10 August | DFID calls for PPA concept notes | |

| 3 September | Deadline for concept notes | |

| 28 September | Successful applicants asked to submit second stage proposals | |

| 29 October | Deadline for proposals | |

| 2-26 November | CSD assessment of proposals and resource allocation | |

| 13-14 December | Final decisions made by Secretary of State and communicated to CSOs | |

| 2011 | 17 January | Coffey made evaluation manager |

| 26 January | Organisations notified of grant requirements | |

| Late February | Organisations submit grant documentation, including logical framework | |

| February/ March | Due diligence process begins (KPMG led) | |

| March | Coffey begins logical framework review and revision | |

| April | Grantees begin to be notified of due diligence results | |

| 9 May | Environmental impact assessments | |

| 21 May | DFID outlines IATI / transparency requirements | |

| 20 May | DFID begins to sign 2011-12 PPA contracts | |

| 30 June | Deadline for final evaluation report on 2008-11 PPAs | |

| July | First steering committee meeting of the Learning Partnership | |

| 11 August | Theory of change workshop held | |

| August | PPA holders begin to receive funding | |

| November | Coffey circulates first draft of evaluation strategy | |

| 15 December | Consultation on draft evaluation strategy | |

| 2012 | 13 February | Workshop with PPA holders on final evaluation strategy |

| 22 February | Evaluation strategy and report format published | |

| April 2012 | First Annual Reports begin to be compiled by CSOs and sent to DFID | |

| July-September | Independent Performance Reviews (IPRs) commissioned and undertaken | |

| 4 September | New Secretary of State appointed | |

| October | IPRs submitted to Coffey | |

| 19 October | Coffey submit draft Mid Term Review (MTR) using IPR information | |

| 23 November | DFID responds to draft MTR | |

| 2013 | 16 January | Coffey submits second draft MTR |

2.40 The due diligence process was completed by KPMG during February and March 2011.36 Overall, the process was the same for all CSOs, irrespective of their size or prior relationship with DFID. KPMG tailored its approach for each CSO, including to the nature of the work and size of grant being considered. The results were not initially routinely shared with CSOs to support their own learning but this was subsequently corrected.

2.41 All but one of our case study CSOs found the due diligence assessment process itself helpful in identifying areas for improvement. These included updating risk registers, strengthening procurement policies and defining key performance indicators. One CSO reported to us that the process added no value and was ‘a missed opportunity’. We are also aware of non case study CSOs that found the process too burdensome.

Reporting and accountability

2.42 Funding under PPAs is provided on a quarterly basis. CSOs informed us that the first payment was considerably delayed, due to additional information requests from DFID. Subsequent payments have been made according to schedule.

2.43 CSOs provide annual activity and financial reports to DFID. They report on the activities set out in their performance framework (logframes) and on the finances of the organisation as a whole. CSOs are also required to submit audited Statutory Accounts to DFID.37

2.44 Visibility of costs has improved during this round of PPAs and may improve further when the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) is implemented. For our six case study organisations, support costs for the PPAs were between 3% and 14% of total expenditure, in line with the overall support costs reported in the case study CSOs’ Statutory Accounts (see Figure A3 in the annex for how they allocated their funding).

2.45 Two of the three larger organisations (WWF and Christian Aid) decided to treat their PPAs as restricted funds.38 Although this was not a DFID requirement, they did this partly in response to a perceived demand from DFID for measurable results. By allocating the PPA funds to specific activities, it was easier to link them to a particular set of development results. This suggests that the accountability mechanisms around the PPAs may be working at cross purposes to the strategic objectives of the instrument.

Relationship to other funding sources

2.46 Among our six case study organisations, the flexible funding offered by a PPA is most significant for the three smaller CSOs. It represents a higher proportion of their turnover, ranging from 14% to 25%, compared to 5% to 8% for the larger organisations. The larger CSOs in our case study sample also have a greater diversity of funding sources, giving them inherently greater flexibility. As the VSO example illustrates (see paragraph 2.34 on page 12), however, this is not always the case.

2.47 It is notable that Christian Aid receives considerably more income from DFID through other mechanisms (£10.6 million) than from its PPA (£7.3 million). In contrast, some CSOs were excluded from receiving other funding from DFID, such as from the Civil Society Challenge Fund, once they were awarded a PPA.

Management of the partnership

2.48 PPAs are managed by the Civil Society Department (CSD), predominantly based in East Kilbride. All of the grant recipients we interviewed noted that CSD was perceived as peripheral to DFID’s main departments. Other stakeholders (including DFID staff) agreed with this assessment but noted that, recently, CSD had been achieving a higher profile. Given the role of civil society in UK aid, we think that managing the relationships with CSOs should be clearly seen as part of DFID’s core business.

2.49 CSD staff ensure performance monitoring takes place and authorise the transfer of funds to CSOs. Six programme managers in CSD (two of whom are part time) share the responsibility for managing PPAs, together with other central grant instruments. In addition, eight programme staff and twelve advisers in CHASE support PPAs as a small component of their roles. A knowledge and learning adviser facilitates learning partnerships among PPA holders and other CSOs. A results and evaluation adviser was appointed in March 2012.

DFID has prioritised accountability over partnership

2.50 CSD has not led the engagement with CSOs on the substantive contribution that they make to DFID’s development goals. DFID’s technical experts in the relevant areas were not involved in setting PPA objectives and, to date, have played little role in managing the PPA partnership. This has been a key shortcoming.

2.51 It is notable that CHASE chose to adjust the management of the Conflict, Humanitarian, Security & Justice PPAs. In August 2012, CHASE assigned both a programme manager and a specialist advisor to engage with each CSO. This improved the quality of collaboration between CHASE and its PPA holders, thereby increasing the value that DFID derives from these relationships.

2.52 In principle, PPA recipients were selected in part because of their ability to work collaboratively with DFID. It does not appear, however, that PPAs have contributed to the quality of this collaboration. Many of the CSO respondents informed us that they could contribute more to DFID’s work. One chief executive from a case study organisation stated that ‘the policy people no longer recognise the value of a relationship with us’.

2.53 All of this suggests that the nature of the partnership that DFID hoped to achieve with PPA holders was not clearly identified. Instead, it was left to develop by chance. This has been a key weakness of the delivery of this round of PPAs. DFID could have tasked its advisory staff to pursue a more substantive relationship, as CHASE has now done.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.54 As the current round of PPAs only began in mid-2011, it is premature to conclude on their impact for intended beneficiaries. In this section, we consider the impact of the funding on the organisational effectiveness of the CSOs. We also assess some of the outputs achieved to date.

Impact on organisational effectiveness

2.55 As set out in paragraph 2.11 on page 8, DFID’s rationale for providing this round of PPAs when seeking Ministerial approval included improving four dimensions of CSOs’ organisational effectiveness: innovation; leverage; results; and efficiency. We look at the organisational outcomes of the PPAs in each of these areas.39 It is notable that these elements were not included in DFID’s logframe monitoring of PPA recipients.

Innovation

2.56 While DFID does not require CSOs to report meaningfully on innovation in their annual reviews, this was assessed as part of the Independent Performance Review (IPR) process.40 Those reviews and our own observations both suggest that the PPAs are encouraging innovation, to different degrees across the case study organisations. For example, Christian Aid has used £400,000 of PPA funds to establish a Learning, Development and Innovation Fund focussed on its PPA themes. It is also scaling up its use of Participatory Vulnerability Capacity Assessments to make its learning process more systematic. Conciliation Resources is using PPA funding to expand its engagement with the private sector. ActionAid and WWF are both using PPA funds to strengthen learning across their programmes.

2.57 We agree with the Mid-Term Review’s observation that there is an unresolved tension between DFID’s demand for concrete results and its desire for innovation. Innovation is often risky and vulnerable to failure and its impact can take time to become evident. This is another case where poorly designed accountability can work against achieving strategic impact.

Leverage

2.58 Reporting indicates that PPA funding has enabled 80% of holders to leverage additional sources of income. They have done this by hiring new staff members, including as fundraisers, or using PPA money as seed funding. Figure 8 on page 17 sets out examples of where case study CSOs report that PPA funding has assisted them in leveraging additional resources.

2.59 One of our case study CSOs obtained £1.25 million from another donor, who chose to fund the CSO in part because it held a DFID PPA. In this way, the PPAs have an accreditation effect, signalling to other donors that the recipients are well-governed and effective organisations. ActionAid reports it has used PPA funding to strengthen its secretariat, which has in turn enabled affiliates in emerging markets to raise an additional £2.2 million. Similarly, the Ethical Trading Initiative and Conciliation Resources informed us that PPA support had helped them to exceed their fundraising targets.

2.60 Signals from DFID that this would be the final round of PPAs have also encouraged the grantees to pursue alternative funding options. Restless Development, like many other recipients, has used the PPA to diversify its income base, putting in place a new revenue model. It has developed a five-year business plan that includes a targeted funding limit from any one source of 30% of turnover, prioritises in-country funding and targets the private sector. Other CSOs have initiated similar fundraising strategies.

ActionAid

- ActionAid Afghanistan secured £72,000 from the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office, a further contract for US$ 80,000, and US$ 240,000 from UN Women for a violence against women initiative.

Conciliation Resources (CR):

- CR reported that the logframe workshop held to redefine the PPA enabled it to improve its submissions for funding to the EU.

- €1.1 million secured from the EU for a Kashmir programme. £175,000 from PPA funds allowed the programme to continue during an 18-month period of reduced funding.

- PPA funds have also been used in the Horn of Africa, leveraging new funds; secured £300,000 from Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Switzerland and £90,000 from the UK Government’s Conflict Pool.

- In West Africa, PPA funding enabled CR to dub a Talking Borders film into other languages, enabling its use in other countries beyond Sierra Leone.

Ethical Trading Initiative

- £77,000 has been leveraged from members for work in supply chains.41

Restless Development

- Trusts & Foundations Co-ordinator has generated total grants of £576,455.

- Uganda increases to funding (partially attributable to PPA) include;

- Uganda Aids Commission: In-country funding, £64,000

- Irish Aid: £124,000

- USAID: £183,000

- Marie Stopes: £45,000

Managing for results

2.61 Another priority for DFID was that the PPAs strengthen the CSOs’ attention to results. This has been a key focus of this round, with impacts beyond the funded CSOs (notably as a result of the Learning Partnership – see paragraphs 2.86 to 2.90 on page 21).

2.62 All of our case study organisations have increased their focus on results. Conciliation Resources has used PPA funds to appoint a Director of Planning and Organisational Performance. It is also putting in place new corporate performance management systems, including a corporate performance dashboard and balanced scorecard reporting. Christian Aid has used PPA funds to pilot new agreements with its partners, which are now being rolled out across the globe. WWF is also using PPA funds to improve reporting systems and tools and to promote beneficiary participation in the monitoring and evaluation of its work.

Efficiency

2.63 The recipients are improving their approaches to value for money. Christian Aid, ActionAid, Restless Development and WWF are all using PPA funding to test new value for money assessment tools. Bond, the network of UK NGOs working in international development, is helping to co-ordinate this work and share the lessons more widely. The New Economics Foundation is providing an advisory role.

2.64 PPA funding was also used by the smaller CSOs to support improvements in financial reporting systems. This included rolling out new financial procedures and reporting templates to overseas branches. The result was more rigorous comparison across branches, leading to better cost control and efficiency improvements.

Other impacts

2.65 PPA holders report that the process has, in turn, led them to renegotiate their relationships with CSO partners in developing countries. These secondary partnerships have been strengthened to include greater transparency and accountability, in large part to meet the PPA requirements.

2.66 The funding is also helping to improve accountability to funders, the public and intended beneficiaries. DFID has stated that, by April 2013, its grantees must comply with International Aid Transparency Initiative standards for disclosure of information on their funding and activities.42 One of the organisations we examined is using PPA funding to help embed the Humanitarian Accountability Partnership standard across its work.43

Delivery of intended outputs to date

2.67 While still early days, CSOs report tangible outputs from the PPAs to DFID. These are the outputs set out in the logical frameworks that the CSOs report against annually to DFID. We are not, however, convinced that these intended outputs fully represent all that the DFID funding is in fact achieving (for instance using PPA funding to leverage new funds that are then used for other activities). We are also not convinced that DFID is measuring activities at the appropriate level for what is intended to be a strategic instrument.

2.68 Some examples of achievements from the six case study CSOs are provided in Figure 9 (see Figure A5 in the annex for outputs from the remaining case study organisations). We report these results without having undertaken our own verification. DFID’s own process of monitoring has been extensive (see paragraph 2.73 on page 19).44 This has included verification by the evaluation manager of CSOs’ early results as set out in the IPRs.

2.69 These activities suggest that a range of impacts is likely to be delivered to the intended beneficiaries, across the diverse areas on which PPA holders focus. All of our case study organisations, except ActionAid, appear to be substantially on track to deliver their intended outputs.45 Figure 9 indicates a pattern of overachievement against Year 1 targets. If this were to be sustained in the remaining two years, it would indicate that the targets being set are not sufficiently stretching.

2.70 In all cases, the PPAs are driving improvements in the ability of CSOs to demonstrate results. In addition, CSOs are seeking to improve the quality of attribution of achievements to PPA funding. It is likely that these changes will lead to improved results for intended beneficiaries. PPAs also have an influence beyond the recipient organisations to their local partners. There is evidence of useful organisational innovations being passed on to the recipients’ partners in developing countries.

| Intended results46 | Performance to date against Year 1 targets |

|---|---|

| Christian Aid (General PPA) | |

| Support development of profitable and resilient livelihoods | - 64,419 marginalised producers and landless labourers supported to develop more resilient livelihoods (Target: 45,000) |

| Support development of livelihood strategies to adapt to climate trends and risks | - Risk analysis conducted in 207 vulnerable communities (Target: 50) - 144 vulnerable communities supported to build links with climate science actors (Target: 30) |

| Influence policy/ practice to promote profitable and resilient livelihoods | - 20 cases of advocacy on livelihoods, risk and resilience (Target: 4) |

| Improved health for women, children and people with HIV | - 3.7 million people reached with health prevention programmes/ supported to access health services (Target: 600,000) - 58,763 people with HIV reached through activities aimed at reducing discrimination (Target: 40,000) |

| Conciliation Resources | |

| Support capacity development of partner organisations | - Average 25 days capacity building support to partners (Target: 20) |

| Support generation of new ideas for conflict transformation | - 4 local dialogues/ exchanges between women across the Line of Control in India Pakistan Kashmir programme (Target: 4) |

| Influence governments and multilaterals to promote alternatives to violence | - Approx. 8,500 people received copies of Accords and policy briefs (Target: 4,000) |

| Increased public awareness of peace and conflict related issues | - 5 conflict analysis papers produced, 1 Accord publication sent to 6,000 people, 6 policy briefs sent to 2,500 people (exceeded targets) |

| Improved planning, M&E systems and communications | - Web visits increased by 1.5% (Target: 5%) - 20% increase in e-news bulletin subscribers (milestone 5%) |

Source: Annual reports and Independent Performance Reviews

2.71 Our view, however, is that seeking to identify and demonstrate results early in the life of what is intended to be a strategic instrument might be counter-productive. CSOs may be encouraged to fund activities that can readily provide reportable results, rather than activities that seek to result in meaningful longer-term change.

Learning

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.72 In this section, we assess how DFID is managing the monitoring and evaluation of its PPAs. We also consider how PPAs are contributing to learning, both by the CSOs and by DFID.

Monitoring and evaluation

Monitoring is not fully appropriate to PPAs’ strategic purpose

2.73 These PPAs have been subject to considerable scrutiny. Within the first year, CSOs underwent due diligence assessments and had to report on the PPAs’ environmental impact. DFID has also put in place three levels of monitoring for PPAs:

- Annual Self-Assessment Reviews: CSOs use a format provided by DFID to report progress against logical framework targets and on (selected) improvements to organisational effectiveness. DFID provides comments in response;

- Independent Performance Reviews (IPRs): Experts hired by CSOs review the progress of each organisation, including a verification of the annual review results. Their findings provide information that assists the evaluation manager to assess the PPAs as a whole. So far, each PPA has been through one IPR, in mid-2012, with another planned for 2014; and

- Mid-Term and End-of-Project Reviews: These are synthesis reports undertaken by the evaluation manager, drawing on information from annual reviews and IPRs. These reviews provide the evidence for evaluating the instrument as a whole and DFID’s overall engagement with CSOs.

2.74 DFID has not clearly differentiated its monitoring of PPAs from project-based funding. A key justification for PPA funding is that the mechanism is strategic and significantly different from project-based funding and, therefore, the emphasis of monitoring should be appropriate to that. Within 18 months of the PPAs beginning, however, the level of scrutiny has been considerable.47

2.75 Monitoring and evaluation should effectively encourage mutual learning. While a number of individuals in CSD are engaged with the CSOs, the outsourcing of much of its monitoring and evaluation of PPAs appears to distance DFID from PPAs.

2.76 In 2006, the NAO said that ‘DFID must develop new tools to measure the effectiveness of its funding of CSOs’. It particularly noted the requirement for this to be put in place because ‘donors are shifting their emphasis towards building capacity and promoting accountability in developing countries’.47

2.77 The principal tool used for monitoring performance is the logical framework. This tool is best suited for monitoring projects with clearly defined outputs and relatively predictable results. It is less suitable for more open-ended processes such as policy advocacy. CSO respondents (whether they were case study organisations or not) consistently reported that the logical frameworks do not sufficiently enable them to describe the impacts they wished to achieve. This particularly referred to their longer-term advocacy objectives, echoing the findings of the 2006 NAO report.48

2.78 Monitoring based on logical frameworks can, therefore, provide only a partial picture of the impact of PPA recipients. DFID has, as a result, asked CSOs to report on such additional factors in their annual reviews. We note also that monitoring by beneficiaries is not prioritised, which is a key deficit.

2.79 DFID’s corporate objectives for CSOs stress their ability to ‘influence, advocate and hold to account national, regional and international institutions’. This is an important aspect of the role played by civil society in the development process. It includes activities such as helping to mobilise poor people to hold their governments to account. Activities of this kind are difficult to incorporate within logical frameworks. The changes they bring about are difficult to measure or verify. We note that DFID has been encouraging its partners to develop innovative methods for capturing this type of impact.

2.80 CSOs were not asked to specify their own organisational development as an output of the PPAs. They are not included in PPA logical frameworks. Given the purpose of the instrument, this seems a significant omission. DFID did, however, ask PPA holders to report in their annual reviews on how the PPAs are helping them to strengthen their performance in areas such as value for money, relevance, lessons learned and transparency.

2.81 The Mid-Term Review has sought to assess some outcomes of the PPAs at too early a stage. DFID tasked the evaluation manager with undertaking assessments of CSO performance, to inform DFID’s performance-based funding decisions for the third year of the PPAs. This assessment was based on evidence from the IPRs, gathered after only one year of PPA funding. Some organisations had yet to implement the changes enabled by their PPA. Given the very different starting points of the organisations, undertaking assessments so early was not a reasonable assessment method.49

The monitoring burden has been disproportionate

2.82 DFID’s need for accountability has resulted in monitoring and evaluation processes that have proved to be unwieldy and burdensome. PPAs were originally intended to reduce transaction costs for both DFID and CSOs, thereby improving the effectiveness of delivery. One CSO noted in its annual review, however, that ‘evaluation and reporting requirements continue to place significant burdens on… programmes and partners’. Another CSO calculated that engaging with DFID had taken more than 18 weeks of staff time in one year. The Evaluation Manual was particularly criticised by PPA holders and IPR evaluators. A typical observation was that it was ‘over-long, over-engineered, poorly thought through and internally inconsistent – an extraordinary behemoth of a document’.

DFID’s outsourced evaluation function does not provide best value

2.83 DFID chose to outsource the role of managing the evaluation process to an external contractor, in part as a result of internal resource constraints. While we commend DFID for prioritising the evaluation function, this arrangement has not fully served the needs of either DFID or CSOs. The terms of reference stressed the need for the contractor to be independent (as befits an evaluator) while tasking it with supporting the grantees to put in place monitoring and evaluation. These tasks have proved incompatible.

2.84 In practice, Coffey, the contractor, has prioritised maintaining independence over building the relationships that would be required for effective support and guidance. For instance, Coffey set out a format and issued written guidance for IPRs but did not respond to (written or verbal) requests for clarification on these from the expert reviewers hired by CSOs. This then potentially weakened the performance of these reviews.

2.85 Our view is that DFID’s terms of reference for the role were over-ambitious, complex and somewhat contradictory. Any contractor would have struggled to deliver all the expected tasks effectively.

Learning by CSOs and DFID

The Learning Partnership has been very productive

2.86 A highly successful Learning Partnership has been established to support this round of PPAs. It is notable that, while learning was a component of the PPA approach, the creation of the Learning Partnership did not form part of the original design for these PPAs. It emerged out of previous experience with Latin American CSOs and has substantially been driven by a key member of the CSD team, the Knowledge and Learning adviser. Figure 10 describes how it is organised.

The Learning Groups organise events to share information and experience, commission reviews of good practice and hold meetings as required, often attended by senior DFID officials. In this way, they provide the only clear mechanism for PPA holders to engage with DFID beyond CSD.

2.87 In the 18 months that it has been operating, the Learning Partnership has already led to some changes in CSO practice. One of the most advanced Learning Groups has been on Measuring Results in Empowerment and Accountability. It organised an event in 2012 chaired by DFID’s Director-General for Policy and Global Issues to identify shared concerns and priorities. It then formed seven thematic work streams and commissioned a review from the Institute of Development Studies on ways of evaluating empowerment.

2.88 The Learning Partnership is encouraging innovation among PPA holders and the wider CSO community. It is notable that DFID’s emphasis on measuring results has stimulated innovative thinking by PPA recipients, especially in areas where measuring results and impact is difficult (such as improving organisational effectiveness). It has also helped to change practice. For instance, both CAFOD and Oxfam report that they are now more open and rigorous when reporting on and learning from unsuccessful activities.

2.89 We assess the Learning Partnership to be an excellent example of DFID and PPA holders engaging at a more strategic level. By bringing PPA grantees and other CSOs into thematic groups, learning is shared among PPA recipients. An evidence base is being developed on successful approaches in areas identified as learning priorities.

2.90 There is, however, considerable potential for this process to enrich DFID and CSO learning further. By involving a broader spectrum of DFID staff, particularly technical experts and country-based personnel, learning would be more clearly embedded across DFID (as well as among CSOs).

DFID is not learning systematically from PPA holders

2.91 We are concerned that DFID is not using all available opportunities to learn from the CSOs it funds. They have much to contribute on a wide range of issues, such as delivering in difficult environments and to hard-to-reach groups, building CSO capacity in developing countries, working with the private sector, multi-stakeholder collaborations, developing delivery standards and leveraging funding and influence. The Learning Partnership demonstrates the creativity and reach of the CSOs and their potential when they work collaboratively.

2.92 By choosing to relate to PPA holders primarily as service deliverers who are accountable to it, DFID is missing out on further opportunities to learn. We would expect a clearer engagement with CSOs as partners (especially given the name of this instrument is Partnership Arrangement). We also think this would increase aspects of the value for money that DFID obtains from the PPAs, by directly building its knowledge and skills.

2.93 In practice, the operation of the contracting out of the evaluation function for these PPAs (both overall and also for the IPRs) has outsourced key aspects of the learning process (for both DFID and CSOs). We are concerned that, since DFID technical staff were not systematically involved in the evaluation of CSOs, opportunities for corporate learning are being missed. It is notable that such technical experts were also not systematically involved in the selection of the CSOs.

3 Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

3.1 We recognise that a vibrant civil society sector is an essential part of the UK aid landscape. A strategic investment in this sector to strengthen CSO capacity and effectiveness through flexible funding is, in principle, an appropriate use of DFID funding.

3.2 To maximise its effect, DFID should have been more explicit about what it hoped to achieve with the PPA instrument and more strategic with its selection criteria. First, it should have identified which corporate priorities it wanted the PPAs to support. It should then have designed a competitive grant-making process designed to maximise that contribution, with fair and transparent competition.

3.3 As the current round of PPA funding only began in 2011, it is too early to draw conclusions on its impact. The evidence from our case studies and other reports suggests, however, that most PPA holders are delivering effectively on their expected outputs to date.

3.4 We found that PPAs have been driving important changes in the way that CSOs operate. In particular, they are improving the quality of performance management and accountability for results. We think it is likely that these changes will lead to improved results for intended beneficiaries, not just from PPA funding but across their full range of activities.

3.5 The complexity of DFID’s processes for reporting results and ensuring accountability has affected the ability of recipients to manage PPA funds flexibly. While the focus on demonstrating impact is important, it has been implemented in such a way that some of the grantees have chosen to use and manage the PPA funds more like conventional restricted funding. This diminishes the additional value of the instrument. Finding an appropriate balance between flexibility and accountability would have required greater clarity by DFID about the overall presumed causal chain (or theory of change) linking PPA funding and improved development impacts. The focus at this stage should be on identifying the planned and actual trajectory of impact rather than encouraging the publication of very short-term outputs.