DFID’s Support to the Health Sector in Zimbabwe

Executive Summary

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review.

Since 2004, DFID has spent over £100 million in support to the health sector in Zimbabwe, mainly on the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS, support to maternal health and the supply of essential medicines. The purpose of this review is to assess how well that money has been spent and to make recommendations for the future.

Overall Findings

Assessment: Green-Amber

DFID’s support to the health sector in Zimbabwe has had a substantial and positive impact, most notably for those living with HIV/AIDS.

Overall, value for money has been good in the majority of the programme. The underlying health system, however, is still failing. DFID helped to avert a total collapse in 2007-09 but the likelihood that it can achieve sustained improvement in health outcomes will remain poor until there is a more secure political context.

Objectives

Assessment: Green

DFID’s support has been relevant and realistic and DFID is considered to be strategic and highly influential by other donors in the sector. It responded to immediate health needs during a period of crisis, balancing this with longer-term institutional support where possible. It ensured that funds did not go through the Government of Zimbabwe.

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

In the area of HIV/AIDS, DFID’s delivery has been responsive to needs, well co-ordinated with other donors and aligned with agreed priorities. The supply of essential medicines has also been efficient. Value for money here has been good. In maternal health, DFID has been operating less effectively, without the same donor support or local capacity and with poorer results.

Overall, we found financial and activity monitoring arrangements to be working well. We found little attempt, however, to bring together financial and performance information to monitor value for money on a regular or co-ordinated basis. Value for money assessment of local partners within the complex delivery chains is especially limited. For example, DFID has no consistent way of capturing and comparing administrative costs.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

In collaboration with other donors, DFID is contributing to a major effort to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic. As a result, there has been a significant positive impact on many people’s lives. Through its work, DFID has significantly increased the availability of free antiretroviral treatment and contributed to the halving of HIV/AIDS prevalence since the 1990s. DFID helped to avoid the total collapse of the health system during the crisis years of 2007-09 by providing essential medicines and supplementing the salaries of skilled staff. It also supported the international response to the nationwide cholera epidemic in 2008.

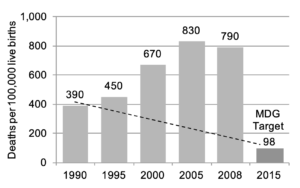

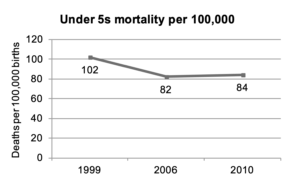

Impacts in maternal and child health, on the other hand, have been disappointing with maternal mortality still on a twenty-year deteriorating trend and improvements in child mortality stalled in the last five years. A major problem is the rise in user fees for maternal health services.

Sustainability of all results is uncertain: the costs of healthcare are set to rise considerably in the medium term, while the prospects for them being funded adequately from local sources are currently poor.

Learning

Assessment: Green

HIV/AIDS programmes have drawn on and influenced global best practice. DFID’s plans include changing the way it supports maternal health, reflecting the need to address this area more effectively.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: As noted by the International Development Committee, DFID should support the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health to strengthen its capability to manage the health system.

Recommendation 2: DFID should plan to address the risk of falling value for money if funding is scaled up further. This should include identifying the major value for money risks and specifying how they will be managed and monitored.

Recommendation 3: DFID should continue its efforts to promote the removal of user fees for pregnant women and children under five and ensure that this is a core objective in future support to maternal health.

Recommendation 4: DFID should ensure more comprehensive reporting across the delivery chains, with clearer linking of funding to performance delivered.

Recommendation 5: DFID should take the lead in the donor community to agree a common definition of administrative costs and require implementing partners to report administrative costs on that basis.

1 Introduction

1.1 This is a review of the Department for International Development’s (DFID’s) assistance to the health sector in Zimbabwe during 2004-05 to 2010-11, with a particular emphasis on the period after 2007. Over £100 million has been spent by DFID on the health sector during this time.1 The purpose of the review is to assess how well it has been spent and identify lessons for the future.

Background to the country and the economic and health crisis of recent years

1.2 Zimbabwe is a country twice the area of the UK. It has a population of 12 million, of which just over 1 million live in the capital, Harare.2

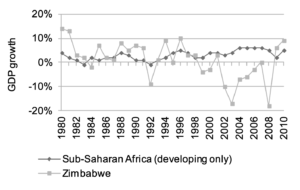

1.3 In spite of having once had a well-developed infrastructure and financial system, Zimbabwe’s economy declined rapidly from the late 1990s as its political situation deteriorated, falling well below other developing sub-Saharan African countries (see Chart 1). National income fell by half between 1998 and 2008: ‘the longest, deepest economic decline seen anywhere outside a war zone’.3

1.4 Economic decline took its toll: HIV/AIDS prevalence rose to be amongst the highest in the world during the 1990s4 and a series of failed harvests during the 2000s increased rural poverty and malnutrition.

1.5 In August 2008, a nationwide cholera epidemic broke out. At the same time, inflation reached record levels. Doctors and nurses found their salaries worthless, causing many to leave. A foreign currency crisis resulted in a serious drugs shortage. Hospitals and clinics closed. By 2009, HIV/AIDS accounted for half of the disease burden in the country. Life expectancy for women had fallen to 34 years from over 60 only a decade earlier.5

1.6 Since the formation of the Government of National Unity in 2009, there has been a recovery. Economic growth reached 9% in 2010.6 International relations are beginning to normalise, although some sanctions are still in place and the situation remains fragile.

Source: World Bank Development Indicators

Source: World Bank Development IndicatorsThe response of DFID and other donors to the crisis

1.7 The UK ended direct support to the Government of Zimbabwe in 2002.7 DFID put its regular country assistance plan on hold and reverted to humanitarian assistance. UK aid rose to £30-35 million a year during 2003-06.8 At this time, DFID reviewed its country strategy, drawing on its increasing experience of working in fragile states and increased the proportion of its funding allocated to the health sector.9

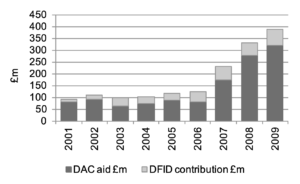

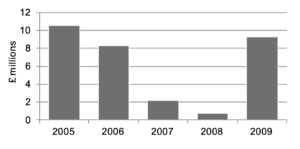

1.8 Aid to Zimbabwe from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)10 countries during the first half of the period of our review (2003-06) averaged about £100 million a year.11 It rose sharply during the crisis years of 2007-09 and has continued to rise, as illustrated by Chart 2 which also shows the increasing contributions from DFID.

1.9 The UK is the second-largest bilateral donor to Zimbabwe after the United States.12 Total direct UK spending in 2010-11 was just over £70 million.1314 This is set to rise to £80 million in 2011-12 and £84 million in 2012-1315 if recent progress by the Government of Zimbabwe is maintained. Support to the health sector is expected to be 35% of DFID’s total bilateral spending in Zimbabwe.16

1.10 The UK channels its aid through the UN and non-state organisations, rather than through the Government of Zimbabwe. Over the period under review, DFID spent just over 40% of its bilateral health sector support through UN partners; just under 60% was spent in collaboration with other bilateral donors (including through UN joint funds); and just under 70% was ultimately spent through local and international Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs).17

1.11 Over half of DFID support to health has been for the treatment and prevention of HIV/AIDS; around a quarter has been for contraceptives and maternal and newborn health; and the remainder has been for the provision of emergency medicines and a series of other smaller programmes. A summary of the programmes is set out in Table 1.

Source: OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Database18Table 1: UK Support to the Zimbabwe Health Sector by area, 2004-15

Source: OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Database18Table 1: UK Support to the Zimbabwe Health Sector by area, 2004-15

| Health Sector Support area | Total UK spend (£m) | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| HIV/AIDS Expanded Support Programme for HIV/AIDS | 35.0 | 2004-11 |

| HIV Prevention and Behaviour Change Programme | 21.0 | 2006-11 |

| Maternal and Newborn Health | 25.0 | 2006-11 |

| Emergency Medicines | 16.5 | 2008-11 |

| Emergency Hospital Rehabilitation | 2.3 | 2009-11 |

| Sanitation and Hygiene | 3.0 | 2010-15 |

| Demographic and health survey | 0.3 | 2010-11 |

| Nutrition Surveillance | 0.2 | 2010 |

Source: www.dfid.gov.uk/zimbabwe/whatwedo1.12 We have focussed our review work on the four largest DFID health programmes, which account for over 90% of health sector spending in Zimbabwe during the period:

- the Expanded Support Programme (ESP) for HIV/AIDS;

- the HIV/AIDS Prevention and Behaviour Change Programme;

- maternal and newborn health; and

- emergency medicines.

1.13 Our review looked at four key areas of DFID’s work in the health sector:

- Objectives: Does the programme have clear, relevant and realistic objectives?

- Delivery: Is the choice of funding and delivery channels appropriate? Do managers ensure sound financial management? Are risks identified and managed effectively?

- Impact: Is the programme delivering clear benefits for the intended beneficiaries? Is there transparency and accountability to the intended beneficiaries and communities as well as to donors and UK taxpayers?

- Learning: Has the programme been designed to facilitate impact measurement? Is there evidence of innovation and sharing of best practice?

1.14 We sought to answer these questions through the following approach, which included desk-based research and a two-week visit to Zimbabwe in September 2011:

- interviews with DFID, UN organisations, bilateral development partners, independent consultants, Ministry of Health staff and NGOs;

- four field visits to public and private health facilities, including talking to a range of intended beneficiaries and hospital staff;

- research on independent views on the health situation and the role of donors in Zimbabwe; and

- reviews of DFID programme documentation and technical papers on health interventions.

1.15 To assess value for money in particular, we:

- analysed financial and performance reporting through the supply chains;

- reviewed administrative costs and used benchmarks and comparisons; and

- interviewed DFID’s implementing partners along the delivery chains of the four programmes and reviewed their records.

1.16 Our focus in this report was on examining governance at various levels, rather than a detailed review of corruption risks. In our examination of DFID’s programmes, however, we found no evidence of instances of fraud or corruption.

1.17 Where possible we have triangulated our information against independent sources.19 More detail on sources, a summary of the methodology, case studies and a glossary are given in the Annex.

2 Findings

2.1 We have set out our findings under the headings we use in our evaluation framework: objectives, delivery, impact and learning.

Objectives

Assessment: Green

2.2 In this section, we review the objectives of the programme.

2.3 DFID’s objectives during this period were to:

- focus on the health sector;

- prioritise expanding support to the treatment and prevention of HIV/AIDS by focussing assistance on hard-to-reach districts not supported by other donors;

- provide essential support to maternal and newborn health;

- work alongside the Ministry of Health where this was appropriate and feasible (known as shadow alignment), whilst ensuring that no funds went through the Government system;

- respond swiftly to a fast-moving emergency; and

- promote donor co-ordination.

2.4 We found these objectives to be appropriate and effective. With the health situation deteriorating dramatically, support to the health sector was essential to save lives. As a relatively non-political area, it was possible for DFID to engage here during a difficult time in UK-Zimbabwe relations.

2.5 The focus within the health sector was also appropriate: HIV/AIDS was, at the time, responsible for over half the total disease burden20 in the country and there were gaps in treatment coverage which DFID could fill. Shortcomings in maternal and newborn health provision were the next most important cause of illness and death, often linked to HIV/AIDS. DFID’s aim to provide support here, at a time of serious challenge in the health system, was the right one.

2.6 We found that DFID was willing to respond swiftly to emerging issues in a rapidly-changing economic and health crisis: for example, in financing the import and distribution of vital medicines to health facilities when there were serious shortages; or stepping in to supplement health workers’ salaries when other donor funds fell short. This demonstrated decisiveness and leadership. A consistent UK presence in the country when other donors were pulling out gave DFID a capacity for critical and strategic thinking, which others acknowledged to us that they often lacked and found valuable.

‘Wise investments have been made.……. DFID has provided leadership, guidance and strategy.’

‘The expanded programme of support to HIV/AIDS was an example of good governance …… there was allowance for thinking at local leadership level. Community leadership has been important. This has included: pastors, local counsellors, village heads.’

‘It has been a crisis (humanitarian) response with a systems approach.’

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.7 In this section, we look at how the four main programmes were delivered. We had a particular focus on whether value for money was achieved.

2.8 DFID has not conducted a systematic assessment of value for money. It has, however, focussed on delivering value for money through a combination of periodic revision of contracts with suppliers, close supervision of implementation and testing and adoption of best practice. Our assessment of the cost-effectiveness of DFID’s interventions and its control of administrative and other costs is included in this section.

Expanded Support Programme (ESP) for HIV/AIDS

2.9 DFID has spent £35 million over the past five years through the Expanded Support Programme for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. The programme is a joint fund of five bilateral donors: Canada, Ireland, Norway, Sweden and the UK. The UK provides two-thirds of the funds for the Expanded Support Programme,21 which in turn accounts for one-third of the total funding for HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe during 2007-09.22

2.10 The Expanded Support Programme began in 2007 and has focussed on three of the Government of Zimbabwe’s priorities for HIV/AIDS:

- HIV prevention through behaviour change promotion;

- treatment and care through the procurement and distribution of antiretroviral drugs; and

- management and co-ordination of the provision of HIV/AIDS treatment.

2.11 It has also occasionally filled gaps in other donors’ funding of the Health Worker Retention Scheme (see Box 1).

Box 1: Health Worker Retention Scheme

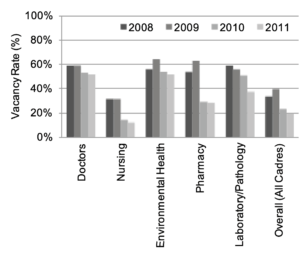

The Health Worker Retention Scheme supplements the salaries of public sector health workers in Zimbabwe. Eligible workers receive a monthly allowance, with basic salaries paid by government. It began on a small scale in 2007, funded by the EU and the Global Fund for Aids, TB and Malaria to support the delivery of HIV/AIDS treatment. In 2008, DFID contributed £650,000 for retention payments to staff in areas affected by the cholera epidemic. It provided a further £1.3 million in 2009. The scheme is now nationwide, targeted on the higher-skilled grades most likely to leave the public service.

A number of other donors (including UNICEF, Australia and Denmark) have also contributed, although the Global Fund is the major donor. When the cost of the scheme escalated to £18 million in 2010 due to an unanticipated growth in staff eligible for payment, the Global Fund decided to phase out its support. Progressive cuts in the monthly allowance have already begun. The scheme has recently been evaluated and shown to have contributed to reduced vacancy rates for nurses. The cut in the monthly allowance as the cost of living continues to rise is causing discontent and the proposal that the Government of Zimbabwe take over the cost of the scheme over the next five years looks, in current circumstances, to be overly optimistic.

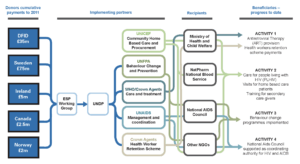

2.12 The Expanded Support Programme uses UN agencies to manage the joint donor fund and act as primary implementing partners. Responsibility for different activities is allocated to different UN leads, with co-ordination by the five donors and the Zimbabwe National Aids Council (NAC).

2.13 In reviewing the programme, we interviewed the other bilateral donors to the fund, all but two23 of the UN implementing partners, the National AIDS Council, the Ministry of Health and the Global Fund Manager. We visited a provincial hospital where we interviewed HIV/AIDS patients. We also visited community behaviour change and community care programmes (in Manicaland) and interviewed a range of stakeholders there.

2.14 The UN agencies implement their programmes through a combination of local NGOs and the private sector24 to procure commodities or deliver services (see summary of the delivery chain in Chart 3 on page 8).

2.15 Channelling resources through the UN was driven by the political situation: DFID needed to operate in concert with the UN when UK-Zimbabwe relations were strained. There have been criticisms of the arrangement from the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health25 and from some NGOs,26 who have pointed to high administrative costs and delays (in the procurement of drugs by UNICEF) and missed opportunities for local capacity development.

2.16 DFID (and other bilateral donors involved in the Expanded Support Programme to whom we spoke) said they found working with the UN in Zimbabwe at this time to be effective, given the political situation. A small group of players, a clear focus of purpose and some notably high-quality personnel in the different UN agencies were identified as the key reasons. UNICEF, in particular, is a trusted partner for DFID in difficult country contexts when risks are high.

2.17 UNICEF’s long-established, global procurement practices and multilateral agency status are seen as rigid. These negatives are balanced, however, by the economies of scale it can achieve in importing drugs. UNICEF told us that its global status, with associated long-term agreements and bulk orders, results in competitive drug costs, with discounts of 20-60%27 achieved on standard prices. Comparing 2010-11 prices of antiretrovirals confirmed that UNICEF achieved prices comparable to (and in some cases significantly lower than) other similar organisations.2829

2.18 Overall, DFID’s delivery under the Expanded Support Programme has been responsive to needs, well co-ordinated with other donors and aligned with priorities articulated in the Government of Zimbabwe’s National Aids Plan.30 The increasing use of alternative delivery channels should continue to provide competition for UNICEF’s price and delivery performance.

HIV/AIDS Prevention and Behaviour Change Programme

2.19 £21 million has been spent during 2006-10 through the Population Services International’s (PSI’s) HIV/AIDS Prevention and Behaviour Change Programme. PSI is an international NGO which has been operating in Zimbabwe since 1996. It initially provided only family planning services and subsequently expanded into HIV/AIDS prevention. DFID provides just over 40% of the total cost31 of the prevention programme. The programme includes:

- distribution of subsidised female and male condoms;

- promoting behaviour change;

- voluntary testing and counselling for HIV/AIDS; and

- male circumcision.32

2.20 We looked at DFID’s financial and activity reports for the programme. We interviewed PSI senior staff and financial managers. We also assessed the technical literature upon which its programmes were based. We visited a field testing site, a male circumcision centre and behaviour change promotion activities.

2.21 The programme works through 40 local partners.33 It has national coverage, with a focus on high-risk areas such as border towns and vulnerable groups such as sex workers.

2.22 Our review found the programme to be strongly focussed on drawing on international best practice, piloting new approaches and monitoring results. From a sample review of the many local partners, we found delivery to be effective, with good support from PSI, detailed financial and activity monitoring and regular audits. A recent DFID-funded impact evaluation34 drew similar conclusions.

The cost-effectiveness of DFID’s HIV/AIDS Programme in Zimbabwe

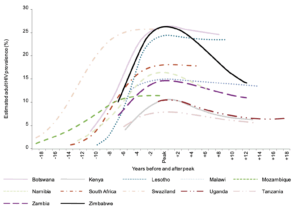

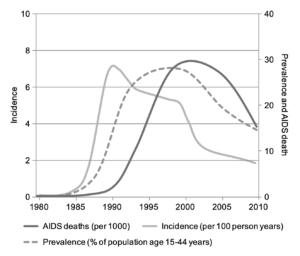

2.23 DFID spends over half of its health budget in Zimbabwe on HIV/AIDS through the Expanded Support and Prevention and Behaviour Change programmes.35 Overall, donor spending on HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe has been low compared to other countries in the region with similar HIV/AIDS prevalence. This can be attributed to the political situation in Zimbabwe over the past ten years, which has deterred donors from operating in the country. For example, Zambia – a country with the same population as Zimbabwe, a similar level of income and also classed as experiencing a mature36 epidemic – received £100 million from donors in 2006 alone: more than three years’ worth of support to Zimbabwe.37 As can be seen in Chart 4 on page 10, while the HIV/AIDS prevalence rate in Zambia has also reduced, it has done so from a lower peak and more slowly than in Zimbabwe. This supports our conclusion that this part of DFID’s programme has been cost-effective.

Source: Zimbabwe Analysis of HIV Epidemic, Response and Modes of Transmission, UNAIDS/Zimbabwe National Aids Council, August 2010.

Source: Zimbabwe Analysis of HIV Epidemic, Response and Modes of Transmission, UNAIDS/Zimbabwe National Aids Council, August 2010.Maternal and newborn health

2.24 The third programme we examined was support to maternal and newborn health. DFID has spent £25 million since 2006 on:

- training of health workers in prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV/AIDS;

- procurement of contraceptives; and

- support to research and evaluation.

2.25 In our review, we interviewed the DFID programme managers, UK health consultancy Liverpool Associates in Tropical Health (LATH) and the programme’s two main implementing partners – Elizabeth Glaser Paediatric AIDS Foundation and Crown Agents. We reviewed DFID’s project documents. We interviewed nurses trained in preventing mother to child transmission.

2.26 We found support for maternal and newborn health has been less effective than that for HIV/AIDS. There have been problems with the management of the DFID programme from the start, when the original intention for a combined UNICEF/UNFPA/WHO programme proved unworkable. As a result, DFID took the decision to tender the function to a managing agent. The project was managed in-house up to that point. This was modified in 2008, when LATH was contracted to provide a range of services that could not be delivered through a combined UN plan.38 While the individual components have delivered results, activities have been fragmented and lack cohesion. Without close co-ordination with other donors – as in the HIV/AIDS programme – serious inroads into the problems around maternal health have not been made. The weakness of the Department for Reproductive Health in the Ministry of Health has also been a contributing factor. These findings explain and are reflected in the limited impacts on improving maternal and child health. They will also be sources of risk to the value for money of DFID’s planned scale-up of support in this area.

Emergency Medicines

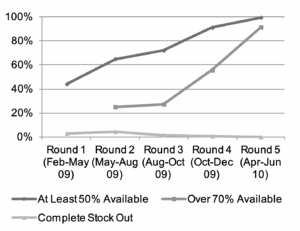

2.28 DFID has contributed £16.5 million to a multi-donor fund managed by UNICEF for the supply of primary health care kits to district health facilities. The support began in 2008 when hyperinflation and foreign currency shortages meant that the Government of Zimbabwe was unable to purchase drugs. It now includes the Vital Medicines Survey (which initially was undertaken by Crown Agents under the maternal and newborn health programme), a regular nationwide survey of health facilities designed to track the availability of supplies over the life of the programme (see Chart 5 on page 14).

2.29 We interviewed UNICEF senior staff and reviewed the Vital Medicines Survey quarterly and annual reports. We visited the pharmacy stores of a provincial and a district hospital. We interviewed pharmacy technicians and asked medical staff at the district hospital about medical supplies.

2.30 UNICEF described to us their procurement process and the basis on which they are able to achieve competitive prices. We were told that a Medical Supplies Co-ordinating Team, consisting of donors, the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and the national drugs procurement agency (NatPharm), has been established which enables national requirements for primary health care commodity needs to be forecast and co-ordinated.

2.31 Medical supplies in Zimbabwe are procured and distributed through three separate supply chains. This represents significant streamlining of the six that were once in operation.39

2.32 We were concerned to note that dependency on the international community, not only for commodities but for management and logistics support, by NatPharm is very high. NatPharm’s financial situation is weak. A recent audit report40 signalled serious concerns with financial management. DFID is dependent on UNICEF as its implementing partner and USAID on its contractor John Snow, Inc. to address these concerns as they are the lead donors for the relationship with NatPharm but the latter’s weakness represents an important risk to the whole system.

Administrative costs and financial management

2.33 One of the costs of DFID’s decision to deliver aid outside government systems is the multiple administrative costs and overheads that are charged at each stage. We took a closer look at these costs.

2.34 We found that overheads charged to DFID by its implementing partners (mainly UN agencies) and to those implementing partners by recipients (international and national NGOs) vary between 4-13% – see Table 2. While this is within what is considered acceptable for a range of UK-based charities,41 it is high when benchmarked more specifically against the World Bank, larger UK international charities and the private sector.42

| Organisation | Overhead % |

|---|---|

| UN Agencies (general) | 11-12% |

| UN Agencies (specialised) | 13% |

| PSI | 12% |

| Elizabeth Glaser Foundation | 12% |

| Crown Agents | 4.25% |

Source: ICAI Review team

2.35 We were given examples of how DFID has challenged administrative charges in the past and negotiated them down. We noted a general downward pressure on administrative costs charged to donors over time, as implementing partners have found efficiencies in delivery. This pressure has intensified recently as donors have begun to challenge up-front costs more frequently in their various service agreements. In assessing the scope to go further, DFID will need to strike the right balance between driving down costs through greater efficiency and ensuring that funds are administered and protected effectively.

2.36 We could find no consistency in what costs were permitted as administration. There was less clarity than is desirable amongst DFID partners on what their own charges took into account. This can be a significant issue amongst local NGOs who do not distinguish between administrative and field staff or between fund-raising activities and other ‘headquarters’ costs.

2.37 At 3%, DFID Zimbabwe’s own administrative cost for its entire programme is low.43 For its health sector programme alone – managed by a small number of the available UK staff and constituting 35% of total spending – the administrative cost is considerably less. DFID has acknowledged,44 in the light of its growing programme, that this is now too low and has increased staff time on health and education.

2.38 In addition to administrative charges, we looked at other costs and assessed DFID’s and its main implementing partners’ financial monitoring. We found good examples of DFID and others squeezing out costs: for example, generic procurement of the vital medicines; repeated cutting of costs in delivering health worker retention payments; and downward revisions of administrative charges.45

2.39 We also observed examples of regular stock audits, spot checks and ad-hoc surveys.46 This reflects a genuine concern we found amongst donors and international NGOs about the political sensitivity of aid spending and the risk of its misuse in Zimbabwe. DFID’s own policy of keeping aid money outside Government of Zimbabwe systems was demonstrated to have been a wise move when in 2007, £5 million held by the Global Fund for Aids, TB and Malaria in Zimbabwean banks was confiscated (see Box 2).

Box 2: The Global Fund in Zimbabwe

The Global Fund was created in 2002 to channel donor funds towards fighting AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. To date, it has committed £14 billion in 150 countries to support large-scale prevention, treatment and care programmes. The Global Fund has granted £55 million to Zimbabwe to date for HIV/AIDS.

In late 2007, £5 million of Global Fund money, which had been deposited in Zimbabwean commercial banks to cover training and other local costs, was confiscated by the Central Reserve Bank when commercial banks were directed to ‘lodge’ all foreign currency with the Bank. The Central Bank failed to release foreign currency back to the banks on request as promised.

The action was discovered through a Global Fund audit. The Fund halted its programme until the Reserve Bank returned its money. The money was eventually returned in November 2008.

2.40 Our review of DFID’s main programmes and implementing partners found evidence of monitoring arrangements operating effectively, with implementing partners required to submit quarterly or six-monthly financial and narrative reports to DFID detailing expenditure against budget and progress against project plan. Reporting did not, however, allow consistent assessment of value for money or provide sufficient transparency in how to link expenditure to results. Apart from the Expanded Support Programme, where the donors scrutinise expenditure against activities, financial monitoring is not subject to systematic management review to ensure that money spent matches targets set.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.41 This section considers the extent to which these programmes are having positive impacts.

2.42 UK funds provided critical support to a health system that was pushed to breaking point between 2007 and 2009.47 They helped to put vital medicines back into health facilities (see Chart 5 on page 14) and contributed to reducing vacancies in some key health posts (see Chart 6 on page 14). These findings were backed up by our discussions with other donors and intended beneficiaries at local hospitals.48

Source: UNICEF Vital Medicines Final Report, 2010

Source: UNICEF Vital Medicines Final Report, 2010

Source: Health Worker Retention Scheme Impact Assessment, September 2011

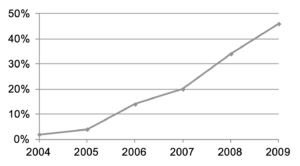

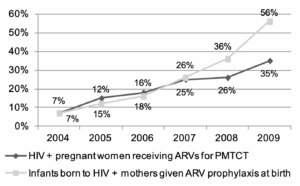

2.43 Through the Expanded Support Programme, antiretroviral therapy (ART) is now reaching 50% of adults who need it free of charge49 (see Chart 7), while prevention of transmission to children through treatment with antiretrovirals (ARVs)50 for mothers and babies has also risen significantly51 (see Chart 8 on page 15). Despite problems with prescribing ARVs for infants,52 Zimbabwe recorded some of the highest increases in enrolment in ART of both adults and children between December 2008 and December 2009.53

Source: UNGASS Report on HIV and AIDS, Zimbabwe Country Report, December 2009, http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/monitoringcountryprogress/2010 progressreportssubmittedbycountries/zimbabwe_2010_country_progres s_report_en.pdf.

Source: UNGASS Report on HIV and AIDS, Zimbabwe Country Report, December 2009

2.44 DFID support through the Expanded Support Programme has contributed to a major improvement in the quality and length of life of over 325,000 HIV/AIDS sufferers.55 Antiretroviral therapy now increases average life expectancy by approximately 20 years and vastly improves quality of life – as confirmed by our interviews with the people we met on our field visits.56 AIDS-related deaths have also begun to decline.57 The number of new infections – one of the key indicators of the effectiveness of prevention interventions – has also been declining since the early 2000s.58 Some of these changes may be attributable to the natural course of the disease but there is expert consensus that behaviour change interventions supported by DFID have also contributed.59

2.45 For maternal and newborn health, outputs from DFID support are:

- contraceptives and essential maternal health commodities for rural facilities;

- training of health personnel in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV/AIDS; and

- technical support (in planning, monitoring and analysis) to the Reproductive Health Unit of the Ministry of Health.

2.46 Outcomes have been mixed. Contraceptive prevalence rates have been broadly maintained and remain among the highest in sub-Saharan Africa,60 yet the percentage of unmet need has stayed unchanged at 13% for some years.61

2.47 Nearly all women receive some skilled care during pregnancy: 93% were reported to have utilised antenatal care services at least once during pregnancy in 2009; while 60% had a skilled attendant during delivery.62

2.48 There are, however, major income and geographical disparities. Skilled assistance at delivery increases significantly with education and wealth. For example, 92% of the richest women had a skilled attendant while less than 40% of the poorest did.63 The urban-rural divide is only slightly better (urban 90%, rural 50%). What is more, these indicators are deteriorating over time: the 60% skilled birth attendance in 2009-10 was 69% in 2005. The percentage of deliveries in a health facility has had a similar decline over the same period: 69% to 61%.6465

2.49 As a result, overall impacts in maternal health – based on progress with reductions in the maternal mortality ratio – have been poor. Little progress has been made over the past two decades on maternal deaths: the rate is still on an underlying upward trend while the previously falling trend in child mortality appears to have stalled (see Charts 9 and 10).

Source: A Situational Analysis on the Status of Women’s and Children’s Rights in Zimbabwe 2005-10, UNICEF, 2010

Source: Zimbabwe Demographic Health Survey 2010-11

Equity and Access

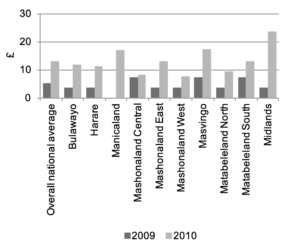

2.50 In addition to the geographical differences in availability of services, there is a serious problem around user fees and transport costs. While donors are ensuring that antiretroviral treatment is free (and in recent years have introduced outreach programmes and decentralised dispensing to local clinics to reduce further the costs to patients), other health services, including maternal health, are subject to variable, high and rising charges. Although key services and vulnerable groups are in principle exempt from charges, lack of clarity in the provisions of the policy and shortage of resources at the facility level have prompted the ad hoc introduction of user fees. These can reach several hundred pounds sterling for emergency caesareans, for example. We found that user fees have risen significantly in the last two years (see Chart 11 on page 17).

2.51 While knowledge and concern about the charging of user fees for health services was widespread, we found limited monitoring of these costs and no evidence of a concerted effort on the part of the Government of Zimbabwe to tackle the issue until recently.

Source: Comparison of the Community Monitoring Programme and the Vital Medicines Availability and Health Services Survey, 2009-2010

Sustainability

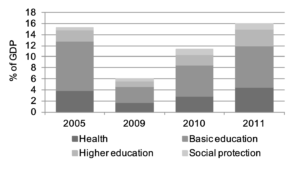

2.52 Current prospects for the sustainability of achievements overall across DFID’s health programme are mixed. There are some positive developments:

- Government allocations to health have improved, recovering to 2005 levels (see Chart 12); and

- the National Aids Levy, a 3% tax on personal and corporate income earmarked for HIV/AIDS, has recovered since 2009 (see Chart 13) and should continue to increase with economic growth.

Source: Challenges in Social Sector Financing in Zimbabwe, Government of Zimbabwe, February 2011

Source: Expanded Support Programme Impact Evaluation, 2011

2.53 There are also signs of structural changes which should reduce costs and increase efficiency in the future. These include greater integration of primary health services and continued rationalisation of the procurement and supply chain for commodities. The Ministry of Health now has – unlike many other ministries – a costed strategy which sets out what the health system should deliver in the future and how much it is estimated that will cost.66 This is a sign that the Ministry has started to consider its financial needs.

2.54 There are, however, major budget distortions, donor dependencies and increasing costs which overshadow these positive signs:

- Underspending in the health budget: while Government of Zimbabwe budget allocations to health have begun to recover since 2009, the actual amount spent appears to be falling. In 2009, spending was only 65% of the original budget;67

- Underfunded drugs budget: the government budget for drugs is grossly underfunded – it was less than 1% of the health budget in 2010, compared to 13% in 2003.68 This is clearly a consequence of donors taking over responsibility for supply;

- Underfunded wages bill: through the salary supplements of the Health Worker Retention Scheme, donors now fund 40% of the health sector wage bill;69 and

- Rising costs: future costs for HIV/AIDS treatment are set to increase significantly, especially in the medium term. The new World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines, which Zimbabwe has adopted, will increase the number of people on treatment, while an improved antiretroviral combination – also being adopted – is reported to be three times the current cost.70 The ongoing decentralisation of antiretroviral therapy provision, while it cuts transport cost for users, shifts that cost onto government.

2.55 These factors constitute a major challenge to the sustainability of DFID’s health programme. The health sector’s dependency on donors is significant. Donor support has risen from 12% of total health expenditure in 1995 to a sum equal to the entire Government health budget by 2010.71 Reducing this level of dependency and strengthening the health budget will depend on politically sensitive and very challenging wider public sector reform. That remains on hold until the political situation shows improvement and DFID can engage more fully with the Government. Until that time, DFID needs to monitor this dependency as future support increases. Careful consideration needs to be given to what can reasonably be expected on health budget improvements and what the limits should be to additional donor funding under these circumstances.

Learning

Assessment: Green

2.56 This section reviews what lessons are being learned.

2.57 DFID has in place its usual arrangements for monitoring inputs, outputs and results. These are well established and, on the whole, effective for managing individual programmes. The information generated could also be used to track and test original assumptions about cost-effectiveness and to compare the cost-effectiveness achieved against other programmes.

2.58 Recent impact assessments have been carried out for the Expanded Support Programme, the Prevention and Behaviour Change Programme and the Health Worker Retention Scheme. Their conclusions are informing the design of the new phase of health support. We note there has not yet been an impact assessment for maternal and newborn health, although plans for future support through a joint donor fund are based on lessons learnt from this less successful programme.

2.59 In terms of innovation, DFID’s HIV/AIDS programmes in Zimbabwe have both drawn on and influenced global best practice, including through research funded specifically by DFID.72 DFID has gradually increased its use of the private sector for delivery of various components of its support. Although it is still small because of the poor policy climate for business, the private sector is now providing some competition to the UN agencies’ procurement functions.

Follow-up of the House of Commons International Development Committee (IDC) recommendations on aid to Zimbabwe

2.60 The report of IDC’s visit to Zimbabwe in 2010 contained several recommendations for DFID’s health sector support. We asked DFID to provide a current assessment of progress supplementing the work we carried out for our review. Each of the health sector-related recommendations together with the current position are set out in Table 3.

| IDC Recommendation | DFID's current position |

|---|---|

| 'We...recommend that [DFID] continue to give priority to supporting the rebuilding of health services.' | DFID has recently reassessed the balance between its humanitarian and development assistance and considers it appropriate to move cautiously towards rebuilding the wider health service. We note DFID is currently proposing a new joint donor fund, based on the successful Expanded Support Programme approach, to support the health sector from now on. Details of DFID's contribution to the programme are still under development, although the programme itself was launched on 31 October 2011. |

| 'The male circumcision programme...appears to be a very cost-effective method of reducing HIV transmission in a country with a prevalence rate as high as Zimbabwe's. We would encourage DFID to support the [male circumcision] programme as it moves from the pilot to full implementation.' | Through the HIV/AIDS Prevention and Behaviour Change programme we have examined in this report, DFID is supporting the scaling-up of male circumcision. |

| 'We request that DFID shares the outcome of its impact assessment of ESP with us when it is available.' | We understand that DFID has done this. |

| 'DFID has recently published a Nutrition Strategy and has included Zimbabwe as one of the six countries where it will focus its efforts to tackle malnutrition. We would welcome more details, in response to this Report, on how the Strategy will guide DFID's work on child health in Zimbabwe.' | We understand that DFID has done this. Child health, including nutrition, is to be a significant component of future DFID support to the health sector. |

| 'We recommend that…DFID provide us with more details of its plans to provide further support to maternal and child health, to assist Zimbabwe to get back on track on these two central Millennium Development Goals.' | The objective of the proposed new joint donor fund mentioned above is to improve maternal and child health and nutrition in Zimbabwe. |

| '[DFID and its donor partners] must ensure health and humanitarian programmes do not lose sight of the importance of public health and hygiene in reducing the spread of disease.' | We understand DFID is in the process of developing a new water and sanitation programme. It is also contributing £10 million to an African Development Bank ZimFund for infrastructure.75 Steps are being taken to ensure child nutrition is tackled through multiple routes, including agriculture and education programmes. |

| 'We recommend that…DFID set out how much of the £60 million of British aid provided in 2009-10 for Zimbabwe was actually spent in Zimbabwe. We also recommend that the Department review the circumstances in which it may be right to buy in-country to stimulate local economic activity, even where this is not the cheapest option.' | We understand DFID has provided IDC with estimates of how much UK aid is spent in-country. We note that for health commodities there is very little domestic production, so the share for domestic health sector spending is likely to be lower than for the UK programme in Zimbabwe as a whole. |

| 'The international community's focus should be on strengthening the capability of the Government of National Unity so that it is better placed to determine its own development priorities.' | We can confirm that focussing donors on strengthening the capability of the Government of National Unity is increasingly the purpose of DFID support to the health sector as it moves out of the crisis period. |

3 Conclusions and Recommendations

3.1 DFID has made valuable and immediate contributions to the health of the people of Zimbabwe during a period of unprecedented crisis. Since 2009, it has also begun to lay tentative foundations for longer-term recovery of a once highly effective public health service.

3.2 In a challenging political and economic context, DFID has succeeded in safeguarding aid flows, ensuring that no funds pass through the Government of Zimbabwe. This has been at a price of limiting engagement with public financial management in the Ministry of Health.

3.3 Assuming that the situation in Zimbabwe continues to stabilise, DFID expects to focus more on strengthening the Ministry of Health’s ability to manage the health system by itself. This needs to form part of DFID’s longer-term exit strategy. As part of this capacity-building, DFID will need to help the Ministry of Health to deal with the budget distortions set out in paragraph 2.54, without increasing donor dependency.

Recommendation 1: As noted by the International Development Committee, DFID should support the Zimbabwe Ministry of Health to strengthen its capability to manage the health system.

3.4 We believe that value for money has been achieved across the majority of the DFID programme. This appears to have been helped by the relatively limited funds flowing to the country in the recent past and close attention to the risk of misuse of aid. Assuming that the situation normalises and that DFID and others commit more to the health sector, there is a risk that these conditions will no longer hold. The risk is that increased levels of aid cannot be as quickly absorbed by a generally weak health system. In particular, donors’ eagerness to demonstrate support to a reforming Government by using its financial systems could run ahead of its capacity, thus raising risks that value for money will fall.

3.5 DFID Zimbabwe has already articulated an overall value for money strategy in its latest Operational Plan. Future planning should show how, in scaling up support for the health sector, the major value for money risks will be managed and monitored, especially in the less proven areas targeted for future support such as maternal health.

Recommendation 2: DFID should plan to address the risk of falling value for money if funding is scaled up further. This should include identifying the major value for money risks and specifying how they will be managed and monitored.

3.6 DFID support to maternal and child health, when other donors were focussing on HIV/AIDS, was the right thing to do. It lacked, however, the donor co-ordination and government capacity of the HIV/AIDS effort to make it fully successful. Whilst we acknowledge that DFID has done some work on the issue of user fee removal, we were concerned to see evidence of high and rising user fees. This is a particular issue for maternal health, which is contributing to a high degree of inequity in access to services. At the current rate of progress, neither maternal nor child health Millennium Development Goals76 will be reached by 2015.

Recommendation 3: DFID should continue its efforts to promote the removal of user fees for pregnant women and children under five and ensure that this is a core objective in future support to maternal health.

3.7 DFID requires regular and detailed financial and activity reporting. It also undertakes annual reviews and occasional impact assessments. These reports, however, are rarely brought together to test value for money or to ensure that aid funds can be tracked right through the delivery chain.

Recommendation 4: DFID should ensure more comprehensive reporting across the delivery chains, with clearer linking of funds provided with performance delivered.

3.8 The proposed new joint donor fund on health would be an opportunity to make a major improvement here – not just for DFID but for all donors in the health sector – and to improve public reporting on all donor flows in health.

Recommendation 5: DFID should take the lead in the donor community to agree a common definition of administrative costs and require implementing partners to report administrative costs on that basis.

3.9 This would promote transparency and comparability in costs.

Annex

Introduction

1. This annex has been designed to support the main report, providing details of the methodology and evidence which underpin our conclusions on the impact which DFID support has had, on health and on HIV/AIDS in particular, in Zimbabwe. It covers:

- an outline of our methodology;

- a summary of the evidence on the effectiveness of the HIV/AIDS interventions DFID has supported and whether programmes have followed global best practice;

- a summary of views from interviewees.

Methodology

2. Our review looked at four key areas of DFID’s work in the health sector, focussing on the four largest programmes:

- the Expanded Support Programme for HIV/AIDS;

- the HIV/AIDS Prevention and Behaviour Change Programme;

- maternal and newborn health; and

- emergency medicines.

3. A common framework of questions guided the investigation, considering the programme’s objectives, delivery mechanisms, impact and learning. We sought to answer these questions through the following approach, which included desk-based research and a two-week visit to Zimbabwe in September 2011:

- interviews with DFID, UN organisations, bilateral development partners, independent consultants, Ministry of Health staff and NGOs;

- four field visits covering public and private health facilities in Harare and provincial and district facilities and community programmes in Manicaland in eastern Zimbabwe, including interviews with patients, doctors, nurses and administrative staff;

- research on independent views on the health situation and the role of donors in Zimbabwe; and

- reviews of DFID programme documentation and technical papers on health interventions.

4. In order to assess value for money, we:

- analysed financial and performance reporting for the four largest DFID health sector programmes (accounting for over 90% of health sector spending during the period);

- reviewed administrative costs and used benchmarks and comparisons;

- interviewed DFID’s implementing partners for the four programmes and reviewed their records; and

- visited a sample of facilities that DFID supported and talked to a range of the intended beneficiaries.

Evidence that DFID-supported HIV/AIDS interventions have followed best practice

5. Best practice in effective response towards HIV/AIDS points towards combinations of interventions focussing on both treatment and prevention and developing the right mix of these to meet a country’s requirements.7778798081

6. DFID in Zimbabwe has utilised this approach (see Table A1 on page 26). For example, the Expanded Support Programme combines both medical and non-medical interventions e.g. antiretroviral treatment, behaviour change communication (BCC) programmes and community mobilisation. The BCC interventions reflect global best practice by aiming to reduce multiple long-term partnerships and promote male circumcision.8283 Community mobilisation initiatives have included the use of HIV positive clients as counsellors.

Summary of evidence on the effectiveness of DFID-supported HIV/AIDS behaviour change interventions

7. There are many challenges in assessing the effectiveness of HIV/AIDS interventions. There is a particular difficulty in assessing the effectiveness of those aimed at behaviour change. We provide a summary of the academic literature on behaviour change for HIV/AIDS prevention. We conclude that there is evidence to support the view that donor interventions have contributed to the reduction in prevalence in Zimbabwe.

8. Zimbabwe has experienced one of the most severe HIV epidemics globally but, since the late 1990s, it has also witnessed one of the most substantial and sustained declines in HIV prevalence.

9. Declines in new HIV infections and prevalence can occur through the natural dynamics of an epidemic. This is because, once the infection saturates and ages within the most vulnerable groups, the rate of transmission within the population as a whole tends to slow and can fall to the point where numbers of AIDS deaths exceed numbers of new infections. Declines in HIV prevalence and HIV incidence are therefore not sufficient indication of the impact of donor-supported interventions.84 Other possible reasons include:

- high rates of mortality;

- extreme poverty;

- selective international migration; and

- higher levels of literacy and marriage amongst the adult population85 and the strong track record of the health service in Zimbabwe.

10. Research in Zimbabwe has shown that these reasons alone could not have contributed to the decline in HIV shown in Chart A1.

Source: Gregson et al., 2010

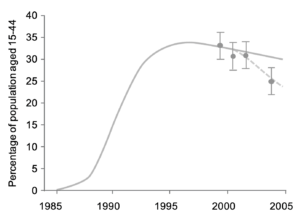

11. In Zimbabwe between 2002 and 2004 a decline in prevalence from 29% to 24% was recorded among 15–44 year old women.86 The observed changes could not be reproduced through modelling the natural evolution of the epidemic by itself but could be generated if the overall probability of infection was reduced by half in 2001 – something which could not have been accomplished without behaviour change.87 Other studies have concluded that there have been behavioural changes that reduce HIV transmission. These include reductions in extramarital, commercial and casual sexual relations and increased openness about HIV.88

12. Chart A2 demonstrates what the prevalence would have been (solid line) in the absence of behaviour change and what was actually observed among women aged 15-44 years old (dashed line).

Source: Hallett, T. B. et al., 2006

13. The overall conclusion is that the pace of decline in HIV prevalence could not have occurred without changes in behaviour and that this can be attributed at least in part to behaviour change programmes.

14. Evidence gathered by our review supported this view of increased openness about HIV and AIDS in Zimbabwe. We witnessed first-hand community leaders and others speaking openly about their HIV status and sexual relations.

| Intervention | Evidence | DFID Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Condom use | Reduces transmission by 90% when used correctly and consistently. | DFID provides support to Population Services International (PSI) who in 2010 distributed 24 million male condoms and 1.4 million female condoms accounting for 35% of all condoms distributed in the country. |

| Medical male circumcision | Reduces the risk of HIV infection in men by approximately 60% when conducted by well-trained professionals. | DFID is supporting a programme of male circumcision run through PSI. In 2010, 11,000 men were circumcised and this was estimated to have averted 770 new infections. |

| Antiretroviral treatment (ART) | Greatly reduces the risk of HIV transmission per exposure. Reduces transmission by 50–90% in sero-discordant couples. Is widely used to prevent vertical transmission to newborns. | DFID supported counselling and testing of 379,000 people during 2010, accounting for 36% of all testing and counselling in the country. Through its maternal and newborn health programme, DFID supports PMTCT (Preventing Mother To Child Transmission) services. This includes supporting training for staff and encouraging mothers to undertake HIV tests so that health professionals can then provide targeted advice to new mothers around preventing mother to child transmission for those tested positive. One example of the success of this programme comes from seven districts where DFID is supporting training for staff providing PMTCT services. In these districts there was an increase from 67% of mothers agreeing to HIV testing in 2007 to 97% in 2011. |

| Social and behavioural change communication | Social marketing and the use of mass media influence attitudes and increase uptake of HIV-related services. | DFID supports behaviour change initiatives targeting young people: for example, Road Shows which are designed to provide information on sexual health and which allow young people to make the safer choices around their sexual behaviour. DFID also provides support through community behaviour change volunteers who provide information on safer sex at community level and through campaigns such as the one run through hairdressers in Zimbabwe, which is designed to promote the use of female condoms. |

| Programme | Positive | Constructive | Negative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expanded Support Programme (ESP) | 'In 2007-08 the ESP working group was the only place where stakeholders were meeting, once a month without fail. It was a good structure, everyone knew the agenda and strong leadership was provided by DFID…ESP did more than provide money. It was a catalysing factor. It got donors thinking and prioritising together.' 'There was a strong element of equity in selecting the districts for ESP. These were districts where there was limited access to ARVs.' Flexibility of programme design for ESP meant that 'there was allowance for thinking at local leadership level. For example, if in a province there was a training programme which was running, staff from neighbouring districts not included in the 16 DFID-funded ESP districts could attend the training if provincial level staff believed this to be of benefit.' 'DFID funds helped build confidence and allowed donors to plan collectively.' 'The level of knowledge of HIV has increased…fewer people are getting sick and there are fewer deaths….My community are evidence of that…Without this programme there would have been more deaths.' 'We encourage information sharing. ..Husbands talk about sex now and people are willing to get tested because they have knowledge.' 'Previously we blamed each other.' 'Access to HIV treatment has reduced denial and stigma around HIV/ AIDS.' 'My own child died in 2004. I was depressed and lost weight and another care giver approached me. I thought I was a social outcast …now I have a role in the community.' 'I had rashes, stomach problems and coughs. Now I'm taking my ARV pills… I'm looking after my daughter.' 'Now I'm on ARVs I'm working. I'm doing ploughing and growing onions and other vegetables to feed my family.' | 'The strength of Zimbabwe is the community and the women in particular. …..women are powerful in Zimbabwe but need to be (further) empowered……to use this strength.' 'Zimbabwe is further ahead than other countries. It is important to continue to strengthen national capacity and thinking. Management practice in particular needs to be strengthened.' 'Zimbabwe has the biggest potential to achieve the MDGs because previously Zimbabwe health systems were already working well. It's not fiction…there is a high level of health-seeking behaviour and high levels of education. The two factors which are discouraging service use are quality of care and user fees.' | 'The AIDS levy goes straight to NAC. ARVs are purchased [using this] but the tax base is shrinking so they can't rely on this fund.' |

| HIV Prevention and Behaviour Change | 'Community leadership has been important. This has included: pastors, local counsellors, village heads…… Behaviour change facilitators are selected by the community… The community home-based care giver could also be the behaviour change facilitator. Where Village Health Workers also exist these groups form a network. Referrals are made between these groups.' 'Previously it was a taboo to ask for a [female] condom. Now it's an everyday product…it [the hairdressers' female condom campaign] is making a difference in women's health.' | 'It's important to invest in preventing new infections. It's like turning off the tap at the primary source.… Behaviour change has to be a longer-term investment.' 'We need to make prevention more comprehensive. Scale up male circumcision and PMTCT. Biomedical interventions have been neglected.' | 'The service has been very slow. I've been here four hours...I'd change the management of the service.' |

| Maternal and Newborn Health Programme (MNH) | MNH programme 'was a critical addition because funding focus was on HIV…key achievements include distributions systems and addressing stock-outs. It was these health services which really kept the health system afloat.' 'DFID provided practical support for training materials. Training was practical, not just designed to provide figures for numbers trained. The training used a case studies approach which encouraged trainees to discuss and compare real cases.' The District Nursing Officer (DNO) supervises all sites. 'Previously they [the DNO] hardly got out to visit clinic sites. Through this programme, they do get out and it also provides a good opportunity to look at needs overall in the District.' 'There is participation of beneficiaries for example at the provincial level...We build strong relationships with Ministry staff…we have planning meetings at provincial level to agree training plans. We don't believe in parallel structures and systems…we build relationships and work with the Ministry of Health.' 'There has been use of technology for example in follow-up data from the clinics if the data is late. This is done using instant messaging devices such as Blackberries.' | 'Now there has been more movement towards a health systems approach.' A roadmap for national maternal and newborn health was developed. This was a 'catalyst in promoting dialogue and integration'. But 'integration is a problem at national level. The AIDS and TB unit at the Ministry of Health is strong'….it is 'externally funded...Other units are not externally funded.' | 'User fees have impacted on the number of pregnant women delivering at a health facility.' |

Abbreviations

- AIDS – Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome

- ART – Antiretroviral therapy

- ARV – Antiretroviral

- BCC – Behaviour change communication

- CHBC – Community and home based care

- DFID – Department for International Development

- DNO – District Nursing Officer

- EGPAF – Elizabeth Glaser Paediatric AIDS Foundation

- ESP – Expanded Support Programme

- GFATM – Global Fund for Aids, TB & Malaria

- HIV – Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- M&E – Monitoring and Evaluation

- MOHCW – Ministry of Health & Child Welfare

- NAC – National AIDS Council

- NATPharm – National Pharmaceutical Company of Zimbabwe

- NGO – Non-Governmental Organisation

- OECD-DAC – Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development – Development Assistance Committee

- PMTCT – Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission

- PSI – Population Services International

- UNAIDS – Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- UNDP – United Nations Development Programme

- UNICEF – United Nations Fund for Children

- UNFPA – United Nations Population Fund

- UNGASS – United Nations General Assembly Special Session

- USAID – United States Agency for International Development

- VCT – Voluntary Counselling & Testing

- WHO – World Health Organization

- ZAN – Zimbabwe AIDS Network

- ZNASP – Zimbabwe National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan

Footnotes

- DFID’s Projects Database, DFID, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/What-we-do/How-UK-aid-is-spent/Project-information/

- UN estimate, 2008.

- DFID Departmental Report 2006, DFID, 2006, Chapter 2, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/departmental-report/2006/CHAP%2002.pdf?epslanguage=en.

- UNGASS Report on HIV and AIDS, Follow-Up To The Declaration Of Commitment On HIV and AIDS: Zimbabwe Country Report, 2010, http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/monitoringcountryprogress/2010progressreportssubmittedbycountries/zimbabwe_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf

- Dead by 34: How Aids and starvation condemn Zimbabwe’s women to early grave, The Independent, 17 November 2006.

- IMF Zimbabwe Staff Report for the 2011 Article IV Consultation, International Monetary Fund, May 2011, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2011/cr11135.pdf.

- DFID Zimbabwe Head of Office 2004-07 and ICAI interviews.

- Statistics on International Development 2003/04-2007/08, DFID, November 2008, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/sid2008/FINAL-printed-SID-2008.pdf.

- DFID Zimbabwe Health Adviser and Deputy Head of Programmes 2005-09 and ICAI Review team interviews.

- International Development Statistics Online, OECD, http://www.oecd.org:80/dac/stats/idsonline.

- Annual average 2009 dollar/sterling exchange rate of £1 = $1.60 has been used throughout the report.

- OECD Zimbabwe Aid at a Glance, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/12/60/1883524.gif.

- A further £5-8 million a year is estimated as UK contributions to Zimbabwe through multilateral programmes (DFID Annual Report, 2011, Volume 1, Table A.5). Funds made available through the Civil Society Challenge Fund/Global Poverty Fund are not included.

- Annual Report and Accounts 2010-11, Volume 1, DFID, 2011, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/departmental-report/2011/Annual-report-2011-vol1.pdf.

- Annual Report and Accounts 2010-11, Volume 1, DFID, 2011, Table B.6, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications1/departmental-report/2011/Annual-report-2011-vol1.pdf.

- From Zimbabwe project data in DFID Key Facts, http://www.dfid.gov.uk/Where-we-work/Africa-Eastern–Southern/Zimbabwe/Key-facts/.

- ICAI Review team estimates. This does not include core contributions made separately by DFID to multilaterals such as the UN and the Global Fund for Aids, TB and Malaria spent by them in Zimbabwe or awards from the DFID Civil Society Challenge Fund to NGOs operating in Zimbabwe. During the period under review, DFID estimates (see Statistics in Development) that the former amounted to approximately £30 million and the latter to £6.5 million (DFID Civil Society Department), covering all sectors.

- For HIV/AIDS, independent monitoring is provided by the UN General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) and UNAIDS.

- G Chapman et al. The burden of disease in Zimbabwe in 1997, Tropical Medicine & International Health, May 2006.

- Review estimates based on reported data.

- UNGASS 2010 figures in Expanded Support Programme Impact Assessment, Health Partners International report to DFID, July 2011.

- International Organisation for Migration and World Health Organisation were not interviewed because they were minor partners or are no longer funded through the Expanded Support Programme.

- Local partners for the UNFPA Behaviour Change were selected through a competitive tender and UNICEF procurement of antiretrovirals is through regular global procurement exercises.

- Ministry of Health interview with ICAI Review team.

- DFID’s Assistance to Zimbabwe, International Development Committee – Eighth Report, March 2010, http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmintdev/252/25202.htm

- Interview with UNICEF representative: Chief of Health, UNICEF Zimbabwe.

- Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) and the Supplier and Contract Management System (SCMS), a web-based procurement portal.

- In this case, Crown Agents Zimbabwe which procures for DFID’s maternal health programme.

- Zimbabwe National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan (ZNASP) 2006-2010, July 2006, National AIDS Council, Harare, Zimbabwe, http://www.safaids.net/files/ZNASP%202006-2010.pdf.

- PSI Zimbabwe Country Director.

- Recent evidence shows that medical circumcision reduces the risk of HIV infection in men by approximately 60% when conducted by well-trained professionals.

- PSI breakdown of partner organisations.

- Mackay, Bruce and Steve Cohen and Kathy Attawell, PSI Behaviour Change Communication Programme Zimbabwe 2006-2010 Impact Assessment, July 2011.

- ICAI Review team estimate.

- UNAIDS definition of “mature” is that HIV transmission is not primarily attributable to identified high-risk groups.

- Zimbabwe Country Report, UNGASS, 2010, http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/zimbabwe_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf.

- DFID Maternal and Neonatal Health Project Annual Reviews.

- ICAI Review team interview with UNICEF senior staff.

- Zimbabwe: Assessment of the National Pharmaceutical Company, Roadmap to Improvement, USAID, April 2011.

- ‘We wouldn’t want to support an organisation spending less than 5% on good management. Without this we would lack confidence that the objectives of the organisation would be achieved. Similarly we would have concerns about a charity spending more than 15% of its income on administration. Such charities we would ask to justify their level of expense.’ http://www.charityfacts.org/charity_facts/charity_costs/what_is_an.html.

- In this case, Crown Agents Zimbabwe.

- ICAI Review team estimates based on information provided by DFID Zimbabwe and DFID East Kilbride.

- ICAI Review team discussion with DFID Zimbabwe.

- ICAI Review team discussion with Crown Agents Zimbabwe.

- By USAID, PSI and UNICEF.

- Interviewees including other donors and national and international donors supported this view of DFID. See quotes from these groups provided in the Annex on page 27.

- See quotes from these groups provided in the Annex on page 27.

- Measured at the old WHO guidelines of treatment starting for those with a viral load of CD4 <200. At the new WHO guidelines of CD4<350 (introduced in 2009), the proportion is 38%.

- Antiretrovirals (ARVs) are drugs which have a suppressive effect on HIV. ART is an anti-HIV treatment using a combination of ARVs.

- ARV treatment for pregnant women dramatically reduces the risk of mother to child transmission of HIV. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: towards universal access, WHO, 2006, http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/arv_guidelines_mtct.pdf

- A lack of trained paediatricians to prescribe ARVs for infants has limited the coverage achieved (Dr Greg Powell, Director Kapnek in ICAI Review team interview). The shortfall in prescribing for infants is illustrated by the difference between the two lines in Chart 8 on page 15.

- Towards Universal Access: Scaling up HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector – Progress report 2010, UNICEF, UNAIDS and WHO, 2010, http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/2010progressreport/full_report_en.pdf

- DFID Expanded Support Programme Impact Evaluation, April 2011, quoting Towards Universal Access, WHO/UNICEF/UNAIDS, 2010.

- See quotes from beneficiaries in Table A2 in the Annex on Page 28.

- Zimbabwe Country Progress Report, UNGASS, 2010, http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/zimbabwe_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf.

- Zimbabwe Country Progress Report, UNGASS, 2010. http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2010/zimbabwe_2010_country_progress_report_en.pdf.

- See a discussion of the debate about the attribution of these impacts in the Annex on page 26.

- Zimbabwe Statistical Factsheet, WHO, 2010. Approximately 60% of married women between 15-49 years old use a modern contraceptive method.

- Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2010-11: Preliminary report, Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, June 2011, http://countryoffice.unfpa.org/zimbabwe/drive/2010-11ZDHSPreliminaryReport-FINAL.pdf

- Multiple Indicator Monitoring Survey (MIMS) 2009: Preliminary Report, Central Statistical Office, Zimbabwe, November 2009, http://ochaonline.un.org/OchaLinkClick.aspx?Link=ocha&docId=1165073.

- Multiple Indicator Monitoring Survey (MIMS) 2009: Preliminary report, Central Statistical Office, Zimbabwe, November 2009, http://ochaonline.un.org/OchaLinkClick.aspx?Link=ocha&docId=1165073. The ‘richest’ and ‘poorest’ are defined by a wealth index using household assets, housing quality, water and sanitation facilities and fuel types used as the main measures of wealth.

- Zimbabwe Demographic and Health survey 2005-2006: Preliminary report, Central Statistical Office, Zimbabwe, July 2006.

- Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2010-11: Preliminary report, Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, June 2011, http://countryoffice.unfpa.org/zimbabwe/drive/2010-11ZDHSPreliminaryReport-FINAL.pdf

- The National Health Strategy for Zimbabwe 2009-2013. Equity and Quality in Health: A People’s Right, Ministry of Health and Child Welfare, 2009, http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s17996en/s17996en.pdf

- John Osika et al., Zimbabwe Health System Assessment 2010. Bethesda, MD: Health Systems 20/20 Project, Abt Associates Inc., January 2011, http://www.healthsystems2020.org/files/2812_file_Zimbabwe_Health_System_Assessment2010.pdf.

- Challenges in Financing Education, Health, and Social Protection Expenditures in Zimbabwe, Government of Zimbabwe, February 2011.

- Challenges in Financing Education, Health, and Social Protection Expenditures in Zimbabwe, Government of Zimbabwe, February 2011.

- Zimbabwe Ministry of Health ICAI Review team interview.

- Challenges in Financing Education, Health, and Social Protection Expenditures in Zimbabwe, Government of Zimbabwe, February 2011.

- Zvitambo Research Programme Director, ICAI Review team interview.

- DFID Zimbabwe project data, http://projects.dfid.gov.uk/project.aspx?Project=202107.

- MDG Goal 5, to reduce maternal mortality by three-quarters and achieve universal access to reproductive health; and MDG 4 to reduce mortality by two-thirds amongst children under five. http://www.beta.undp.org/undp/en/home/mdgoverview.html

- Practical Guidelines for Intensifying HIV Prevention: Towards Universal Access, UNAIDS, 2007, http://data.unaids.org/pub/Manual/2007/20070306_prevention_guidelines_towards_universal_access_en.pdf.

- McCoy, Sandra I., and Rugare A. Kangwende and Nancy S. Padian, Behavior Change Interventions to Prevent HIV Infection among Women Living in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review, 2010, AIDS Behavior 14:469–482. 2010, http://www.3ieimpact.org/admin/pdfs_synthetic2/008%20Review.pdf.

- Opportunity in Crisis. Preventing HIV form Early Adolescence to Young Adulthood, UNICEF, June 2011, http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Opportunity_in_Crisis-Report_EN_052711.pdf.

- The Interagency Task Team on Prevention of HIV Infection in Pregnant Women, Mothers and their Children. Guidance on global scale-up of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: Towards universal access for women, infants and young children and eliminating HIV and AIDS among children, WHO/ UNICEF, 2007, http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/PMTCT_enWEBNov26.pdf.

- Wilson D. and Halperin D. T., Know Your Epidemic, Know your response: a useful approach, if we get it right, The Lancet, Volume 372, August 2008.

- Practical Guidelines for Intensifying HIV Prevention Towards Universal Access, UNAIDSM, 2007, http://data.unaids.org/pub/Manual/2007/20070306_prevention_guidelines_towards_universal_access_en.pdf.

- Wilson D. and Halperin D. T., Know Your Epidemic, Know your response: a useful approach, if we get it right, The Lancet, Volume 372, August 2008.

- Gregson et al., HIV Decline in Zimbabwe due to reductions in risky sex? Evidence from a comprehensive Epidemiological Review, International Journal of Epidemiology, 39: 1311-1323, 2010.

- Literacy rates for adults 15+ years of age were 92% and for those aged 15-24 the rates were 99%, according to 2009 statistics: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/socind/literacy.htm.

- Epidemiological Factsheet on HIV/AIDS Core Data on Epidemiology and Response Zimbabwe 2008 Update, WHO/UNAIDS/UNICEF, October 2008.

- From Hallett, T. B. et al., Declines in HIV prevalence can be associated with changing sexual behaviour in Uganda, urban Kenya, Zimbabwe and urban Haiti, Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2006, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1693572/.