The UK Department of Health and Social Care’s aid-funded global health research and innovation

Score summary

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) funds relevant and effective global health research and innovation portfolios and is working to enhance low- and middle-income country leadership of research projects, but increased attention to impact is needed.

A significant share of UK official development assistance (ODA) for health is spent on research, including through DHSC. Between 2018-19 and 2024-25, DHSC’s ODA spend on global health research will total almost £1 billion. This ODA is used to fund a Global Health Research portfolio of DHSC-managed partnerships and large programmes managed by the National Institute for Health and Care Research, and a Global Health Security research and innovation portfolio managed by DHSC. We find that both portfolios support research that is ODA-eligible and generally relevant to health challenges in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). DHSC is working to improve LMIC access to research funding but has further to go in untying its aid and in embedding the principle of equitable partnership across all its research activities.

DHSC makes innovative use of community engagement and involvement to strengthen research projects and deliver localised benefits, and some projects are already contributing to improved health outcomes, most obviously through vaccine development for typhoid and COVID-19. LMIC researchers are also benefitting from support to develop their individual capacity. However, DHSC’s approach to capacity strengthening at the institutional and system levels is less considered, attention to research impact pathways is insufficient, and coordination in LMIC contexts with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office is patchy. This limits the prospect of DHSC’s significant ODA expenditure contributing to transformational change and greater LMIC leadership in global health research.

Overall, DHSC’s ODA-funded global health research is focused on generating benefits for people in LMICs. ICAI observed a range of well-designed and context-appropriate projects, and some have already yielded impressive results. The department is taking a proactive approach to learning and is applying this on an ongoing basis to adapt its programming. We also see a positive trajectory on many of the challenges noted in our review.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How relevant are DHSC’s ODA-funded global health research portfolios to the UK’s strategic objectives on global health? |  |

| Effectiveness: How effectively does DHSC’s ODA-funded research contribute to improving global health outcomes? |  |

| Learning: Has the design of DHSC’s global health research portfolios been informed by its own monitoring, evaluation and learning, and by lessons from other ODA-funded health research? |  |

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| AARs | After Action Reviews |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| CAB | Community advisory board |

| CAG | Community advisory group |

| CARB-X | Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator |

| CEI | Community engagement and involvement |

| CEPI | Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations |

| CHAI | Clinton Health Access Initiative |

| DFID | Department for International Development |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| DSIT | Department for Science, Innovation and Technology |

| ESSENCE | Enhancing Support for Strengthening the Effectiveness of National Capacity Efforts |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCDO EQuALS | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, Evaluation Quality Assurance and Learning Service |

| FCDO RED | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, Research and Evidence Directorate |

| FIND | Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics |

| GAMRIF | The Global Antimicrobial Resistance Innovation Fund |

| GARDP | Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership |

| GCC | Grand Challenges Canada |

| GECO | Global Effort on COVID-19 Research |

| GHR | Global Health Research |

| GHS | Global Health Security |

| GRIPP | Getting research into policy and practice |

| HAC | Health advisory committee |

| HFF | Health Funders Forum |

| HIC | High-income country |

| IATI | International Aid Transparency Initiative |

| IDRC | International Development Research Centre |

| InnoVet AMR | Innovative Veterinary Solutions for Antimicrobial Resistance |

| ISAG | Independent Scientific Advisory Group |

| JGHT | Joint Global Health Trials Initiative |

| LGBTQIA+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, asexual |

| LMICs | Low- and middle-income countries |

| MEL | Monitoring, evaluation and learning |

| MERS | Middle East Respiratory Syndrome |

| MLW | Malawi Liverpool Wellcome |

| MODARI | Mapping ODA research and innovation |

| MRC | Medical Research Council |

| NIHR | National Institute for Health and Care Research |

| NIHR Global HPSR | National Institute for Health and Care Research, Global Health Policy and Systems Research |

| NIHR RIGHT | National Institute for Health and Care Research, Research and Innovation for Global Health Transformation |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD-DAC | Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| R&D | Research and development |

| RSTMH | Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene |

| SCOR | Strategic Coherence for ODA-funded Research |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SIN | Science and Innovation Network |

| SPARC | Short Placement Award for Research Collaboration |

| SR | Spending Review |

| TDR | The Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases |

| UK-PHRST | UK Public Health Rapid Support Team |

| UKCDR | UK Collaborative on Development Research |

| UKRI | UK Research and Innovation |

| UKVN | UK Vaccine Network |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| Glossary of key terms | |

|---|---|

| Aid untying | The practice of removing restrictions that require aid to be spent on goods and services from the donor country or from a small group of specified countries. Untied aid can be used to purchase goods and services from any country, promoting greater efficiency and effectiveness in aid delivery, and improving value for money. |

| Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) | The ability of microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi, to resist the effects of antimicrobial drugs, rendering them ineffective in treating infections. |

| Capacity building | The planned development or increase in knowledge, output rate, management, skills, and other capabilities of an organisation through acquisition, incentives, technology and training. It is a process that supports the initial stages of building or creating capacities, assuming that there are no existing capacities to start from. |

| Capacity strengthening | The process of developing and enhancing the capabilities of individuals, organisations and systems to perform functions, solve problems, and set and achieve objectives in a sustainable manner. In global health research, the focus is on strengthening capacity to conduct, manage, share and apply research in ways that inform health policy and practice. |

| Equitable research partnerships | Collaborations between researchers and institutions that are based on mutual respect, shared responsibilities and shared benefits. These partnerships aim to ensure fair distribution of resources, recognition and opportunities, especially between high-income and low- and middle-income countries. |

| Global disease burden | The collective impact of diseases, injuries and risk factors on the health of populations worldwide, often measured in terms of mortality, morbidity, disability-adjusted life years, or economic costs. |

| Global health | A field of study, research and practice that prioritises improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide. It addresses transnational health issues, determinants and solutions, involving many disciplines within and beyond the health sciences. |

| Global health research | International scientific study aimed at understanding health issues, developing interventions, and improving health outcomes across diverse populations and regions. |

| Health systems | The organisations, people and actions whose primary purpose is to promote, restore, or maintain health. This includes the provision of health services, a well-performing workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines, financing, leadership and governance. |

| Infectious disease | A disease caused by pathogenic microorganisms, such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, or fungi, which can spread directly or indirectly from one person to another. |

| Innovation | The process of translating an idea or invention into a good or service that creates value or for which customers will pay. In the context of global health, it involves developing new methods, products, or services that improve health outcomes. |

| Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) | Chronic diseases that are not passed from person to person. They include cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes. NCDs are often caused by genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioural factors. |

| Pandemic | An epidemic that has spread over multiple countries or continents, affecting a large proportion of the global population and requiring coordinated international efforts to control and mitigate its impact. |

| Pathogen | A microorganism, such as a virus, bacterium, parasite, or fungus, that can cause disease in its host. |

| R&D (Research and development) | The process of scientific investigation, experimentation and innovation aimed at discovering new knowledge, technologies, products, or solutions to address various challenges and needs. |

| Social and environmental determinants of health | The non-medical factors and conditions relating to society and the environment, including economic and cultural characteristics, that influence an individual’s health status and well-being. These determinants encompass aspects such as income, education, employment, housing, access to healthcare, social support networks, environmental quality and exposure to hazards. Understanding and addressing these factors is essential for promoting health equity and improving overall population health outcomes. |

Executive summary

Global health research aims to advance knowledge and innovation to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity globally, with particular attention to health challenges and potential solutions in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In recent decades, the UK has played an important role in many global health research initiatives and programmes, contributing funds from the official development assistance (ODA) budget managed by the former Department for International Development (DFID). The 2015 Aid Strategy broadened this responsibility, and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) received its first ODA allocations, including for global health research, through the 2015 spending review. In 2023, DHSC’s ODA spend was the third-largest of all government departments, after the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the Home Office.

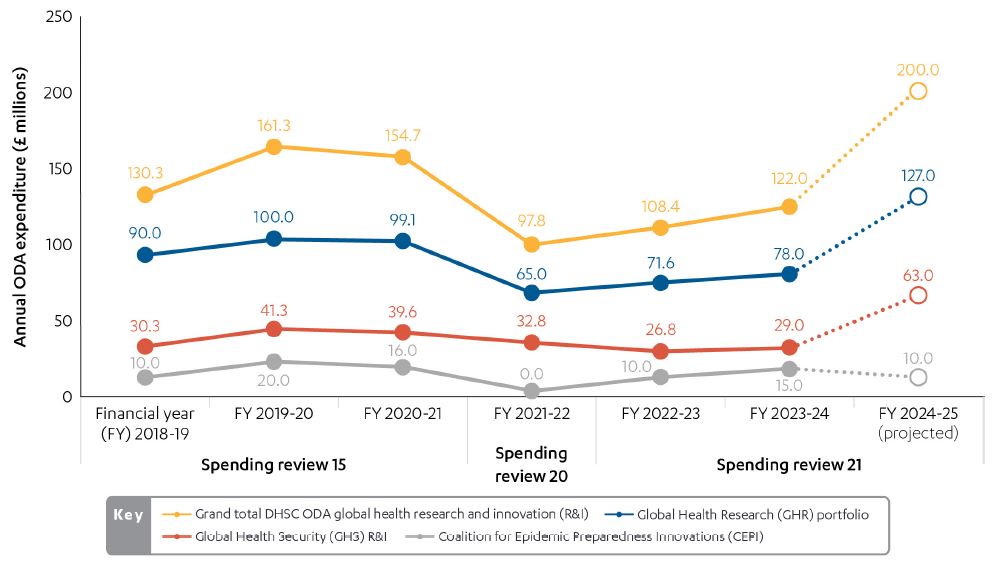

DHSC’s ODA for global health research is now considerable and will total almost £1 billion over the period 2018-19 to 2024-25. This funds two portfolios. The first, Global Health Research (GHR), consists of programmes managed through the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and partnerships managed by DHSC. The second portfolio, Global Health Security (GHS) research and innovation, is managed by DHSC as part of wider departmental and UK government efforts to improve health security and health resilience.

The purpose of this review is to assess the relevance of DHSC’s strategy and approach to global health research and the effectiveness of its programming in this area. It also looks at how well the department is learning and adapting its global health research portfolios.

Relevance: How relevant are DHSC’s ODA-funded global health research portfolios to the UK’s strategic objectives on global health?

DHSC’s programming aligns with UK government strategies related to global health research, which prioritise economic and trade objectives alongside resilience to health threats. In developing its ODA-funded research portfolios, DHSC initially aimed to complement the work of other government departments, funding research in the areas of global health security, non-communicable diseases and health issues affecting people in ODA-eligible middle-income countries (rather than low-income countries). However, DHSC’s focus has broadened considerably over time, to include research areas where FCDO has been active such as health systems, to address health challenges in low-income countries, and to fill funding gaps. In interviews with ICAI, several stakeholders commented on the increased breadth of DHSC and NIHR programming, perceiving a lack of focus or comparative advantage. Some stakeholders also raised the question of whether NIHR’s initial narrow remit had made it more difficult to spend its ODA allocation.

ICAI’s country case studies and citizen engagement confirmed that the research projects funded by DHSC are generally relevant to the health challenges experienced in LMICs, including issues that are stigmatised or underfunded. Projects seek to identify and test appropriate solutions to these challenges, in some cases through multi-country clinical trials.

ICAI found that DHSC takes account of global stakeholder and expert views when scoping new areas of programming, including through an Independent Scientific Advisory Group that influences the shape of the GHR portfolio and has strong LMIC expert participation. This portfolio is also informed by DHSC involvement in fora that bring together UK and international funders of health and development research. However, DHSC has no staff in-country, or processes for engaging with the research priorities of LMIC governments, and aside from in India, we found from interviews and our three country case studies that the department has little engagement with UK embassies and FCDO health advisers. This limits opportunities for DHSC to connect its ODA-funded portfolios with national health research plans, FCDO programming, or the work of other development partners in LMICs.

DHSC references ‘equitable partnerships’ as a principle guiding the development and implementation of its ODA-funded research. NIHR provides its applicants with guidance to support the development of equitable partnerships between UK and LMIC researchers, and additional funds have been made available through some programmes to enable LMIC researchers to participate in the design of research projects and the ultimate dissemination of findings. Nevertheless, until recently, most of DHSC’s global health research programmes required projects to be led by UK institutions. While the majority of schemes are now opening calls to LMIC proposals, few applicants have been successful, even for projects that need no science and innovation infrastructure. This lack of success indicates a need for process adjustments or improved guidance and support for LMIC applicants, as well as for wider capacity strengthening. Furthermore, LMIC researcher voices are missing from many learning activities and in project and programme reporting, and feedback loops from LMIC communities and stakeholders to DHSC are limited, even where community engagement and involvement approaches are used at project level.

DHSC told ICAI that it is committed to the principle of aid untying. However, its approach to doing so in global health research seems inconsistent. In interviews with DHSC and NIHR, when asked about aid untying, responses almost always conflated this with the different but linked objectives of equitable partnership with and direct funding to institutions in LMICs. Among DHSC’s programmes, the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Innovation Fund offers the best example of aid untying, where delivery partners are selected with the aim of funding the best science to meet global health needs and leverage additional investment, with few if any geographical restrictions. However, until late 2020, NIHR was unable to issue contracts to non-UK entities, and NIHR appears comfortable with UK institutions being the only high-income country participants engaged through its programming. This has limited the ability of LMIC institutions to choose their research partners, going against the general stance of the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD-DAC), the body overseeing aid rules, that untying fosters aid effectiveness.

DHSC programming is generally well aligned with the DAC’s ODA eligibility criterion related to LMIC primary benefit, and NIHR has established robust processes for screening proposals for ODA eligibility and for managing ODA funds. However, NIHR’s financial reporting is used to monitor ongoing ODA eligibility and the requirements are burdensome, particularly for LMIC researchers.

We award DHSC a green-amber score for relevance, in recognition of the department’s efforts to complement other funders of global health research and to address topics that are underfunded relative to the illness, injury and death they cause. DHSC is attentive to the issue of ODA eligibility, and the department is working to improve LMIC access to its funding schemes, but it has further to go in ensuring that its research partnerships are equitable and to untie aid.

Effectiveness: How effectively does DHSC’s ODA-funded research contribute to improving global health outcomes?

DHSC-funded global health research projects offer the prospect of improving health practice and ultimately health outcomes. ICAI visited projects in India and Malawi that were testing healthcare interventions or developing new products with the potential to improve outcomes in neonatal and maternal health or communicable diseases, for example. Some DHSC-funded projects are already contributing to improved health outcomes, most obviously through the development of vaccines, such as for typhoid and COVID-19. However, project-level monitoring primarily captures research activities and outputs, as well as some localised benefits delivered through community engagement and involvement (CEI) approaches, in areas such as health promotion and patient advocacy. More generally, NIHR’s CEI requirements have encouraged researchers to engage communities in their projects, with community advisory groups in Malawi involved in the design and delivery of research activities, patient recruitment and community outreach.

Many programmes lack detailed results frameworks, and approaches to impact reporting vary. For example, the GHR portfolio uses theories of change alongside a core indicator set against which all programmes should report, although some indicators are optional, and reporting is not consistent. The GHS programmes use logical frameworks (logframes) with targets and milestones, but unrealistic output and outcome targets mean some of these have not been very useful. In addition, many programmes indicate a patchy understanding of pathways for evidence translation, which could limit their potential to shape policy and practice. In part, this reflects limited guidance from DHSC and NIHR, including on more complex pathways to impact involving rigorous evidence synthesis. Collaboration between DHSC and FCDO has enabled some projects to access additional funding and partnerships to advance their research or bring new products to market. However, such potential is constrained by DHSC’s patchy engagement with FCDO health and science advisory networks, which also lack capacity, and by the lack of up-to-date and easily accessible data about many of the research projects funded by DHSC ODA.

DHSC and NIHR have stated an intent to strengthen LMIC research capacity at individual, institutional and system levels, consistent with UK and international definitions and guidance. In practice, DHSC capacity-strengthening initiatives focus on individuals, with demonstrable impact at this level. Almost 1,000 individuals who have been funded or otherwise supported through DHSC’s GHR portfolio have received advice and support as members of the NIHR GHR Academy (which offers training and development opportunities). Around 90% of NIHR GHR Academy members are from LMICs, and many researchers have been funded to complete postgraduate degrees. Some DHSC programmes have provided training in technical skills, in areas such as clinical trials and vaccine manufacture. ICAI found that this support is welcomed, particularly by early- and mid-career researchers in LMICs. However, without associated growth in institutional and system-level capacity, there is a clear risk of individual capacity ebbing away through researchers moving out of the sector or relocating. Some DHSC programmes do include complementary support to institutional capacity strengthening, for example in financial management, and ICAI visited laboratories in India that had been upgraded under one project. However, institutional capacity-strengthening outcomes are not systematically monitored and only one relatively recent programme (which was not in our sample) has a focus on this. DHSC ambitions related to system-level capacity strengthening are also unclear, and the department’s ODA funds are spread widely and thinly, limiting their transformative potential.

We have awarded DHSC’s global health research programming a green-amber score for effectiveness. This reflects some impressive achievements in areas such as vaccine development, alongside the department’s innovative use of CEI to strengthen research projects and deliver localised benefits, and its evident contribution to strengthening individual research capacity in LMICs. However, DHSC is not sufficiently deliberate in planning, monitoring and reporting its contribution to strengthening institutional and system-level capacity. The department is not doing enough to realise the transformative potential of its large GHR portfolio through, for instance, promoting rigorous evidence synthesis, or by supporting the uptake of research findings and innovations through purposeful collaboration with FCDO.

Learning: Has the design of DHSC’s global health research portfolios been informed by its own monitoring, evaluation and learning, and by lessons from other ODA-funded health research?

DHSC is an active participant in fora that enable the department to learn from other UK and international funders of global health research. When DHSC was first allocated ODA, the department engaged proactively with DFID to understand how to spend this money effectively. Since then, learning and coordination have become more ad hoc and dependent on personal relationships. NIHR’s ODA learning curve appears to have been steeper than necessary due to an emphasis on learning by doing, rather than learning from and adapting relevant elements of established ODA approaches used by the Medical Research Council, Wellcome and DFID/ FCDO, such as the effective use of logframes for research projects or best practice in developing pathways to research impact. NIHR has, however, since sought help from FCDO in specific areas.

There has been limited portfolio-level learning within DHSC, particularly related to impact, until recently. However, within the GHR portfolio, this is starting to improve, aided by NIHR’s engagement of a new GHR programme director and a recently concluded GHR portfolio evaluation. Reviews are also planned of the portfolio-level theory of change and of key areas such as CEI. However, while learning is evident within GHS programmes, there is currently no formal approach for GHS portfolio-level learning. There are also few mechanisms within DHSC for cross-portfolio learning between GHR and GHS on shared principles and challenges, such as equitable partnerships and capacity strengthening.

Formal monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are not yet used consistently across the GHR and GHS portfolios, and DHSC has been slow to complete and publish programme-level annual reviews. However, ICAI found good evidence that, where evaluations have been conducted, findings are being used to support learning and improvement. For example, all GHS programmes have been evaluated, with the recommendations shaping future programme phases.

Mechanisms for learning and adaptation within programmes have improved during the period under review. Some programmes have been specifically designed to pilot new approaches and to enable iterative learning and adaptation, in particular the Research and Innovation for Global Health Transformation programme. After Action Reviews are also well used by DHSC and NIHR to support learning and improvement within and across programmes. Although these and many other learning activities have been UK-dominated, there are some signs that LMIC researchers are becoming more involved, including through country-level roundtables convened by DHSC and NIHR.

With an increased emphasis on learning and adaptation evident, alongside some signs of improved engagement by LMIC researchers, DHSC is strengthening its ability to share, scale up and adapt effective global health research practice across its GHR portfolio, if not yet across the GHS portfolio. The department is evidently keen to adapt and improve its ODA-funded programming, and it has used opportunities to pilot and innovate to good effect. In recognition of this, we award a green-amber score for learning.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: DHSC should focus on pathways to impact across its global health research portfolios, including by strengthening guidance for potential applicants and putting in place mechanisms for planning and measuring impact.

Recommendation 2: DHSC should ensure that its principle of equitable partnership is embedded and tracked across all areas of activity related to its global health research portfolios, including research funding, knowledge translation, learning, programme monitoring and evaluation.

Recommendation 3: DHSC should progressively untie its aid for global health research, to ensure value for money and to allow low- and middle-income country researchers to identify the most appropriate partners for their projects.

Recommendation 4: DHSC should purposively collaborate with FCDO to strengthen UK health ODA coherence and alignment to partner country needs and priorities.

Recommendation 5: DHSC and NIHR should take a more strategic approach towards institutional and system-level capacity strengthening in low- and middle-income countries, and develop metrics to track plausible contributions in these areas.

1. Introduction

1.1 Global health research aims to advance knowledge and innovation to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity globally. As the burden of ill health is highest in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), studies are centred on problems and solutions in these contexts. This area of research grew significantly in scale and importance globally during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it has become more central to the strategic priorities of the UK international development programme. Aid-funded global health research is also central to the UK’s contribution to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (see Box 1).

2.2 This is the first ICAI review that looks at global health research as a topic and the first to focus solely on aid spending by the UK Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), which until now has not been covered as extensively as other government departments that spend large amounts of official development assistance (ODA). The review adds value by casting a light on an area of aid expenditure that has received little attention from scrutiny bodies. Our review questions are set out in Table 1.

1.3 The review looks at currently active and recently closed DHSC ODA-funded global health research and innovation programmes, particularly those that have been active since 2018. It covers programmes that aim to advance knowledge as a global public good, as well as to generate research and innovation with intended benefits for LMICs. These programmes fall into two broad portfolios: a Global Health Research (GHR) portfolio, with some of the research managed through the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and the rest through partnerships managed by DHSC, and a Global Health Security (GHS) research and innovation portfolio managed by DHSC.

1.4 Programming that is out of scope for this review includes research funding calls that are still in the commissioning phase, and global health security programmes that are not focused on research and innovation such as the Fleming Fund. The deployment and capacity-building components of the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team were also deemed out of scope. We reviewed a sample of the programmes that were in scope. The full list of sampled programmes can be found in Annex 1.

1.5 This review builds on earlier ICAI reviews, including the review of the UK’s response to global health threats and research-focused reviews such as those of the Global Challenges Research Fund and the Newton Fund. It is also linked to ICAI’s COVID-19 reviews. ICAI’s synthesis review of findings from ICAI reports between 2019 and 2023 specifically mentions global health research, and it notes that DHSC awards to Oxford University through the UK Vaccine Network from 2016 onwards laid important foundations for, and subsequently supported, the development of the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

Box 1: Global health research and the Sustainable Development Goals

The UN Sustainable Development Goals, also known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure all people enjoy prosperity and peace. Funding for global health research directly supports Goal 3 on good health and well-being and Goal 9 on fostering innovation, which contributes to Goal 8 on decent work and economic growth. Goal 17 echoes the need for equitable partnerships between low- and middle-income countries and high-income countries to conduct global health research.

![]() Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. The targets and indicators for this goal include vaccine coverage, access to medicines, and total ODA to medical research and basic health sectors.

Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. The targets and indicators for this goal include vaccine coverage, access to medicines, and total ODA to medical research and basic health sectors.

Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. Targets for this goal underline the importance of innovation to economic development.

8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. Targets for this goal underline the importance of innovation to economic development.

Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation. The targets and indicators for this goal include numbers of researchers as well as research and development expenditure as a share of gross domestic product.

Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation. The targets and indicators for this goal include numbers of researchers as well as research and development expenditure as a share of gross domestic product.

![]() Goal 17: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development. This goal includes targets and indicators related to capacity building, to enhancing knowledge sharing and access to science, technology and innovation, and to North-South, South-South and triangular cooperation.

Goal 17: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalise the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development. This goal includes targets and indicators related to capacity building, to enhancing knowledge sharing and access to science, technology and innovation, and to North-South, South-South and triangular cooperation.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| Relevance: How relevant is DHSC’s ODA-funded global health research portfolio to the UK’s strategic objectives on global health? | •Does DHSC have a credible strategy for directing health research to meet global health needs and priorities? •How appropriate is DHSC’s approach to building equitable research partnerships? •How effectively does DHSC screen and monitor its research grants for ODA eligibility and for consistency with UK commitments on tied aid? |

| Effectiveness: How effectively does DHSC’s ODA-funded research contribute to improving global health outcomes? | •How well has DHSC-funded global health research contributed to improvements in health practice in low- and middle-income countries? •How well have DHSC-funded research programmes disseminated their results and supported other pathways to impact? •How well has DHSC enhanced research capacity in low- and middle-income countries? |

| Learning: Has the design of DHSC’s research portfolio been informed by its own monitoring, evaluation and learning, and by lessons from other ODA-funded health research? | •How well has DHSC learned from other ODA programmes that aim to carry out research or to build research and innovation capacity? • How well do DHSC managers of global health research programmes and their implementers adapt in response to lessons learned? |

2. Methodology

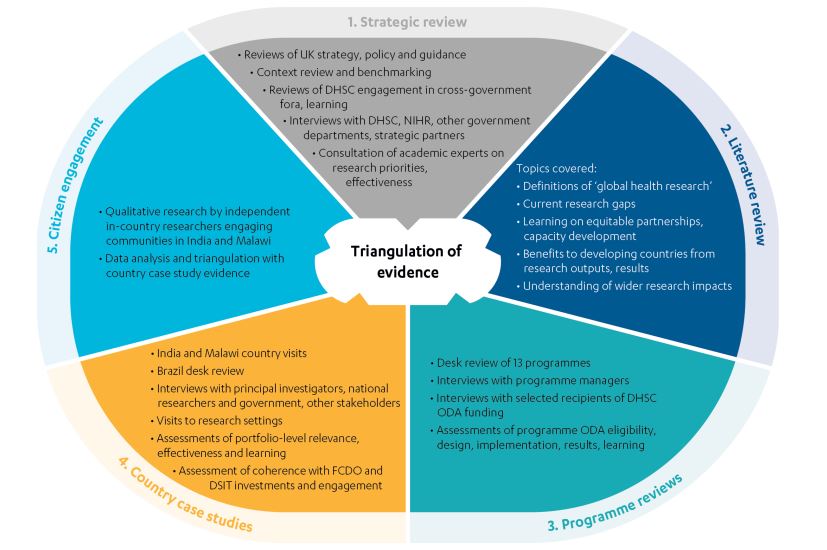

2.1 The methodology for this review has been designed around five components (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Review methodology

2.2 As set out in Figure 1, the components of our methodology enabled us to address our review questions and ensure sufficient triangulation of findings:

- Strategic review: The strategic review covered relevant UK government and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) strategies, policies and guidance related to global health research, alongside guidance on official development assistance (ODA) and research from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC), which the UK is expected to follow. It also examined DHSC engagement in coordination and learning mechanisms. Document review was complemented by interviews with a wide range of UK government representatives, DHSC delivery partners and external stakeholders.

- Literature review: The literature review covered relevant peer-reviewed literature on global health research alongside key grey literature, enabling us to assess DHSC’s approach in relation to the broader evidence base.

- Programme reviews: We conducted desk reviews of 13 DHSC programmes (see Table 2) identified using the sampling criteria outlined in our approach paper. We examined relevant documents and conducted interviews with programme managers in DHSC, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and relevant partner organisations, as well as with selected research institutions. The programme reviews focused on whether programme designs are evidence-based and consistent with rules on ODA eligibility and commitments to untied aid, whether programmes are implemented effectively and achieving their intended results, and the degree to which learning leads to adaptation and improvement.

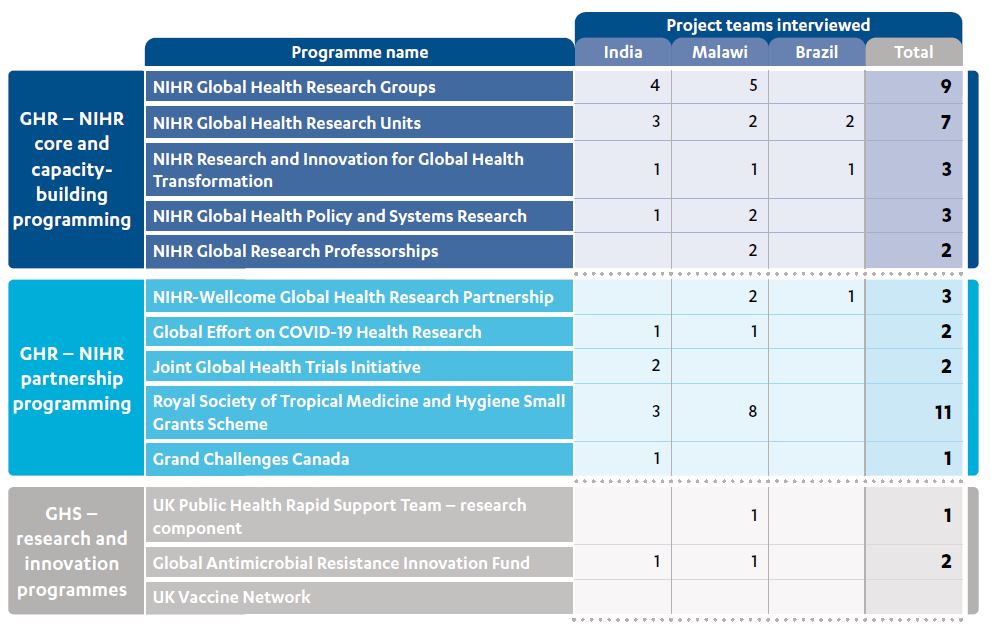

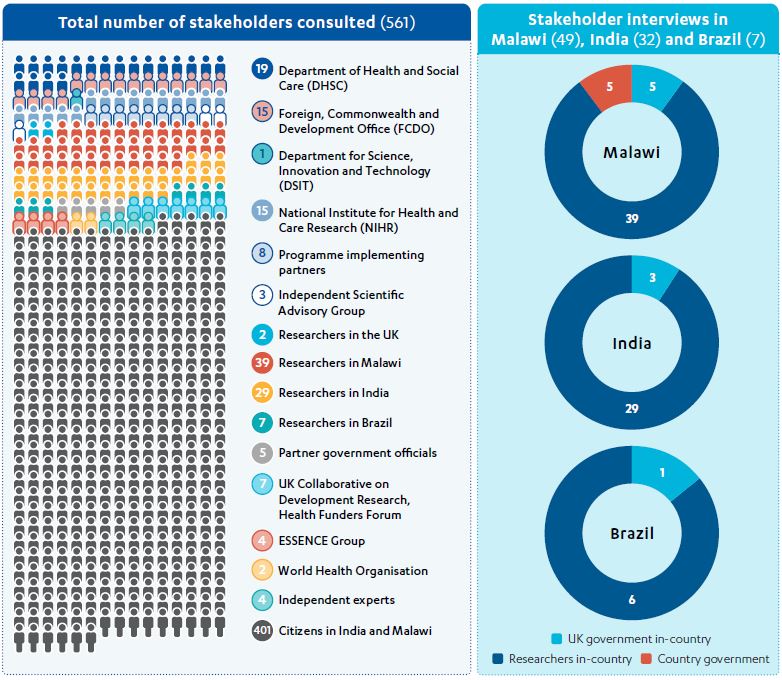

- Country case studies: We conducted two country visits to India and Malawi and one country desk review of Brazil. The case studies assessed the DHSC global health research portfolio in each country (Figure 2), collecting and analysing evidence from interviews with principal investigators and other researchers, national government, FCDO staff in LMICs, and other stakeholders (Figure 3). Information from the country visits was triangulated with project and programme documentation, as well as with feedback from citizen engagement research in India and Malawi.

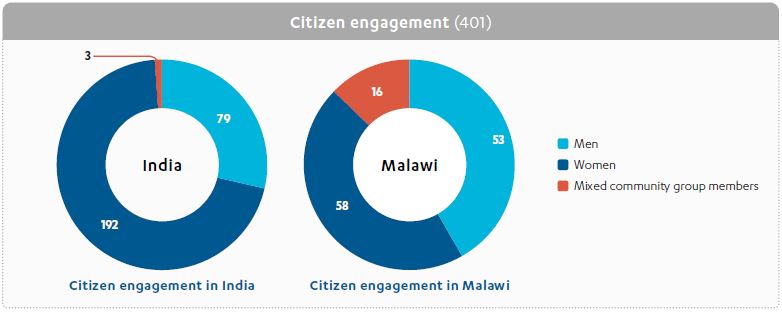

- Citizen engagement (with people affected by or expected to benefit from UK aid): ICAI is committed to incorporating the voices of people affected by UK aid into its reviews. Qualitative research in India and Malawi was undertaken by national research partners. Their consultations included citizens in poorer communities who are expected to benefit from research outputs such as new health products or technologies, and a small number of community groups advising DHSC ODA-funded research projects and institutions (see Figure 3).

Table 2: Programme sample

| Programmes | Spend (actual and projected) in review period | Brief description |

|---|---|---|

| NIHR-managed programmes | ||

| NIHR Global Health Research Groups | £145.93m | The NIHR Global Health Research Groups programme funds research to address locally identified challenges in LMICs, by supporting equitable research partnerships between researchers and institutions in LMICs and the UK. It aims to generate evidence for improved health outcomes and build sustainable research capacity in LMICs. Funding is available to research groups either new to delivering applied health research globally or wishing to expand an existing partnership. |

| NIHR Global Health Research Units | £103.63m | The NIHR Global Health Research Units programme funds ambitious collaborative research projects to address locally identified challenges in LMICs, by supporting equitable partnerships between universities and research institutes in LMICs and the UK. It aims to generate evidence for improved health outcomes and strengthen research capabilities in LMICs. Funding is awarded to partnerships with established track records in delivering internationally recognised global health research. |

| NIHR Research and Innovation for Global Health Transformation (RIGHT) | £73.09m | The NIHR RIGHT programme funds interdisciplinary applied health research in LMICs on areas of unmet need where a strategic and targeted injection of funds can result in a transformative impact. It prioritises research benefitting LMIC populations while fostering capacity building and knowledge exchange through equitable partnerships in LMICs and between LMIC and UK researchers, and by promoting interdisciplinary collaboration. Each funding opportunity has a focus on a different thematic priority. |

| NIHR Global Health Policy and Systems Research (Global HPSR) | £32.09m | The NIHR Global HPSR programme funds health policy and systems research that is directly and primarily of benefit to people in LMICs, by supporting equitable partnerships in LMICs and between LMICs and the UK. It aims to generate evidence to improve health systems and inform policy and practice in LMICs, which will lead to improved outcomes for the most vulnerable and address issues of health equity. |

| NIHR Global Research Professorships | £18.65m | The NIHR Global Research Professorships programme funds research leaders with a track record of applied health research in LMICs, to promote effective translation of research and to strengthen research leadership at the highest academic levels. |

| NIHR partnership programmes | ||

| NIHR-Wellcome Global Health Research Partnership – Wellcome | £16.96m | The NIHR-Wellcome Global Health Research Partnership funded existing work developed by Wellcome to support postgraduate students and postdoctoral and early-career researchers from LMICs and the UK, with a focus on research in health priority areas for LMICs and activities to improve research uptake into policy. |

| Global Effort on COVID-19 (GECO) Health Research – MRC | £8.07m | GECO was a rapid UK cross-government funding call aiming to support applied health research that would address COVID-19 knowledge gaps in ODA-eligible countries, aligned to the WHO COVID-19 research roadmap. |

| Joint Global Health Trials Initiative (JGHT) – MRC | £30.40m | JGHT is a UK cross-government initiative aiming to generate new knowledge to contribute to improving health in LMICs. It focuses on late-stage clinical research and smaller pilot studies that yield implementable results and address the major causes of mortality or morbidity in LMICs. |

| Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (RSTMH) Small Grants/Early Career Grants Scheme – RSTMH | £4.94m | The RSTMH Early Career Grants Scheme supports LMIC-based early-career researchers to develop their research skills and expertise. This partnership contributes to the NIHR Global Health Research priority to strengthen research capacity in LMICs. |

| Global Mental Health programme – Grand Challenges Canada (GCC) | £6m | This programme supports high-impact innovations that improve treatments and expand access to care for people living with or at risk of mental health disorders, with a focus on the mental health needs of young people in LMICs. |

| Global health security research and innovation programmes | ||

| UK Public Health Rapid Support Team (UK-PHRST) – research component | £13.90m | The research component of UK-PHRST collaborates with partners to conduct research to develop the evidence base for best practice in epidemic preparedness and response in ODA-eligible countries, and to develop local research capacity. |

| Global Antimicrobial Resistance Innovation Fund (GAMRIF) | £114.14m | GAMRIF is a UK aid fund that supports research and development around the world to reduce the threat of antimicrobial resistance in humans, animals and the environment, for the benefit of people in LMICs. |

| UK Vaccine Network (UKVN) | £137.08m | UKVN targets funds to support the development of new vaccines and vaccine technologies for emerging infectious disease threats in LMICs, to support better control in the future of disease outbreaks that risk becoming epidemics. |

2.3 A more detailed table with key data for each sampled programme is in Annex 1.

2.4 Figure 2 demonstrates how our programme sample was reflected in the country case studies for this review, and it shows the number of relevant project teams that were interviewed in each country context.

Figure 2: Sampling infographic

Figure 3: Sample of stakeholders consulted

2.5 Our methodology and approach were independently peer-reviewed. We provide a full description of our methodology and sampling in our approach paper. Our programme review sample accounts for approximately 73% of DHSC’s actual and forecast global health research expenditure during the period 2018-19 to 2024-25. Our country case studies encompassed low-income, lower-middle income and upper-middle income countries with different levels of health system coverage and of health threat readiness. The three countries also offered the opportunity to look at a range of funded projects within our broader programme sample (see Figure 2). The principal limitations to our methodology are outlined in Box 2.

Box 2: Limitations of the review methodology

- Data on impact: Research commissioning is carried out over long periods of time, with long and complex pathways to impact. Most research projects funded by DHSC ODA have not yet been completed and most findings have not been reported. We could not assess research quality in the time available for this review, which is a critical factor affecting uptake and impact.

- Generalisability of findings: Our country case study project sample represents a relatively small share of the research funded by large and complex programmes.

- Timescale: This review has a shorter timeline than would normally be the case for a full ICAI review because of delays in extending the third ICAI commission, which means that the evidence gathering period was condensed and that different components of the methodology had to run in parallel.

2.6 Evidence gathering for the review was undertaken during the period November 2023 to January 2024. Altogether, we conducted 122 interviews covering 160 key stakeholders, including more than 30 representatives of UK government departments and agencies, and we reviewed more than 1,000 documents. Through our citizen engagement component, researchers in Malawi and India spoke with more than 400 people (see Figure 3).

3. Background

The global context

3.1 The field of global health research has its historical roots in colonial health practice and the concept of ‘tropical medicine’. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, tropical medicine research centres were established in the global North, including the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in the UK. Alongside this, the funding of research units in Africa and Asia, which were linked with research institutes and universities in the global North, created islands of capacity in countries with limited wider infrastructure.

3.2 Within today’s international health architecture, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has among its functions the promotion and conduct of global health research. The Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR), launched in 1975, is co-sponsored by WHO and three other international agencies. It focuses on strengthening research capacity in “disease-affected countries” and translating evidence into practice to reduce infectious disease and build resilience in the most vulnerable populations.

3.3 Despite historical funding and the efforts of TDR, in 1990 an independent Commission on Health Research for Development found a “stark contrast between the global distribution of sickness and death, and the allocation of health research funding”, with less than 10% of health research spending devoted to 90% of the global disease burden. This came to be known as the 10/90 gap. An increase in aid funding for global health research and related capacity strengthening, to 5% of health ODA, was recommended.

3.4 The late 1990s and early 2000s witnessed a proliferation of public-private partnerships and other global health research initiatives designed to close the 10/90 gap. These included the Global Forum on Health Research, the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, and the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative, alongside a wide range of disease-specific product development partnerships such as the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and the Medicines for Malaria Venture.

3.5 The UK played an important role in many of these global health research initiatives and partnerships, primarily through official development assistance (ODA) contributions made by the former Department for International Development (DFID). However, many other UK institutions have also played their part. For example, the Royal College of Physicians hosted a 2012 meeting to agree the London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases, which aimed to control or eliminate ten neglected diseases by 2020 through public and private sector financing of health research and development (R&D). New opportunities for R&D have been created through the work of the Wellcome Sanger Institute to provide the reference genome sequences of all human infectious disease pathogens.

UK aid funding for global health research

3.6 The allocation of UK ODA to global health research remained DFID’s responsibility until relatively recently. DFID’s work in this area included funding to research consortia and product development partnerships, the agreement of research concordats with key institutions such as the Medical Research Council, and the creation of health resource centres focused on evidence for policy and practice.

3.7 The 2015 Aid Strategy signalled a growing role for other government departments in ODA management. The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) received its first ODA allocations through the 2015 spending review, as global health security concerns intensified across the UK government and internationally due to the 2014-16 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, and with the O’Neill Review on Antimicrobial Resistance ongoing. Indeed, the 2015 UK Aid Strategy referenced several new global health research initiatives, including the UK Vaccine Network (UKVN) and the Global AMR Innovation Fund (GAMRIF), under its objective on “strengthening resilience and response to crises”. In 2023, DHSC’s ODA spend was the third-largest of all government departments, after FCDO and the Home Office.

3.8 DHSC now manages two global health research portfolios. The first is the Global Health Research (GHR) portfolio. This includes programmes managed through the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), which was set up to improve the health of the UK through research but from 2016 also took on the task of managing aid-funded research programmes for the primary benefit of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (see Box 3). The GHR portfolio also includes NIHR partnerships that are managed by DHSC. The second is the Global Health Security (GHS) research and innovation portfolio, which is managed by DHSC as part of wider departmental and UK government programming to improve health security and health resilience. DHSC also contributes to the Coalition on Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). We set out the DHSC ODA-funded research programmes that we sampled across these two portfolios in Table 2 and Figure 2 above. Box 4 summarises eligibility criteria for the use of ODA to fund global health research.

Box 3: The National Institute for Health and Care Research

The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) is funded by DHSC “to improve the health and wealth of the nation through research” across six core workstreams. NIHR’s boards report to DHSC’s Science, Research and Evidence Directorate, and senior staff have dual roles. The DHSC Chief Scientific Adviser acts as NIHR Chief Executive, for example. NIHR’s funding schemes are managed through its Coordinating Centre.

NIHR’s ODA-funded global health workstream – which is in effect DHSC’s GHR portfolio – was established in 2016, and by the 2018-19 financial year it accounted for almost 10% of NIHR expenditure. NIHR describes its work on global health as having three strands:

- Programmes: researcher-led and targeted thematic research calls, which NIHR directly commissions and manages.

- Partnerships: schemes to fund global health research, which NIHR contributes to or co-creates with other organisations that have a strong track record in this field.

- People: support for research capability, training, and the development of global health researchers and future leaders in the UK and LMICs, including activities delivered through the NIHR Global Health Research Academy. This work cuts across the programmes and partnerships.

During 2022-23, NIHR’s total spend was £1.32 billion, of which £71.6 million was ODA. According to NIHR, this supported research across 53 LMICs. NIHR has now established itself as a major funder of global health research in the UK and internationally.

Box 4: The use of ODA to fund global health research

For health research to be eligible for ODA funding, it must be conducted for the primary benefit of LMICs, in line with the rules established by the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD-DAC).

Benefits to LMICs that align with OECD-DAC definitions include:

- Public health or social welfare, for example where research is focused on diseases or health issues that primarily affect people in ODA-eligible countries.

- Health research capacity development, such as training, the sharing of knowledge and intellectual property, and the transfer of technologies.

- Economic development, for example where research is undertaken by institutions in ODA-eligible countries.

3.9 Figure 4 shows actual and projected DHSC ODA expenditure on global health research from the 201819 financial year through to the end of the current spending review period in 2024-25. Within this timeframe, DHSC’s ODA spending and programming has been shaped by several factors beyond its control, including reductions to UK gross national income (GNI) and to the target for ODA as a share of GNI, HM Treasury requests for ODA savings across government, and the sharp increase in the use of ODA to support refugees and asylum seekers in the UK.

Figure 4: DHSC ODA expenditure on global health research 2018-19 to 2024-25

Figure 4 shows actual spend by UK financial year for 2018-19 to 2023-24 and projected expenditure for 2024-25. Projections are indicative and future expenditure may be affected by changing global needs, including humanitarian crises, fluctuations in GNI and other ODA allocation decisions.

Alongside DHSC, the main UK government departments spending ODA on global health research are the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT). The UK spends a much larger share of its health ODA on research than other countries, significantly exceeding the 5% recommended to overcome the 10/90 gap. According to the WHO Global Observatory on Health R&D, the UK spent $1.44 billion on health ODA in 2020, of which 33.45% was for “medical research”. In comparison, Germany’s health ODA expenditure was $1.7 billion, with just 3.17% going to “medical research”. After the UK, Belgium spends the greatest share of its health ODA on research (14.71% in 2020).

Within the UK, there are several cross-government ODA governance, oversight and coordination mechanisms for global health research. The UK Collaborative on Development Research (UKCDR) sits outside government and is hosted by Wellcome, its only non-government member. UKCDR aims to map all ODA for research and improve its coherence, including through meetings of the Strategic Coherence of ODA-funded Research (SCOR) Board, which brings together the major UK funders of development research. UKCDR also convenes several research funders’ groups on specific topics, including the Health Funders Forum.

3.12 The UK’s Global Health Framework, agreed in 2023, is a key document aimed at ensuring government coherence in this area, and it includes an objective on research. However, a wide range of UK government strategies are relevant to ODA and other global health research programmes. The principal publications during the period under review are set out in Box 5.

Box 5: UK government strategy and global health research

Since 2018, the UK government has published several strategy documents related to global health research.

The 2021 UK Innovation Strategy stated that UK aid “finances innovation around the world to reduce poverty, stimulate growth, create opportunities for UK business and build trading partners of the future”, while also emphasising the role of innovation in the COVID-19 pandemic response. This was underscored in the 2021 autumn budget, which showed an upward trajectory for total R&D ODA across all departments, rising from £600 million in 2021-22 to £1 billion in 2024-25.

The 2021 Integrated Review of security, defence, development and foreign policy confirmed the spending review 2020 allocation of £1.3 billion to DHSC (ODA and non-ODA) for R&D. It committed to accelerating the development and deployment of vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics for “emerging diseases”. Global health security was cited as an ODA priority for 2021-22, alongside science and technology.

The 2022 Strategy for International Development stated that the UK will “invest in the research and innovations needed to keep driving breakthroughs in health systems and health security… to respond to the changing burden of disease and health threats, including from COVID-19, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and zoonoses”. The strategy referred repeatedly to the need to draw on UK expertise, research and technology for development gain.

The 2023 Integrated Review Refresh identified global health as an “area of vulnerability” for the UK, emphasising the importance of “strengthening health resilience at home and overseas”. Objectives include the UK “leading a global campaign on ‘open science for global resilience’, making the case for a secure, collaborative approach to science that ensures low- and middle-income countries have access to knowledge and resources that can support improved resilience”.

The vision set out in the 2023 Biological Security Strategy is that “by 2030, the UK is resilient to a spectrum of biological threats, and a world leader in responsible innovation, making a positive impact on global health, economic and security outcomes”. The document stresses the importance of health R&D throughout. The Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine features as a case study, which notes the vital importance of long-term funding through UKVN and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). GAMRIF is cited as an example of UK leadership on AMR.

The 2023 White Paper on International Development outlines the UK’s commitment to champion collaborative global health research with LMICs. It aims to utilise UK scientific expertise to develop new technologies, strengthen health systems, and improve healthcare access worldwide. The White Paper sets out an ambition to expand funding of Southern-led partnerships “to accelerate research and innovation, and to ensure that findings translate into impacts at scale”, and it highlights initiatives such as UKVN and GAMRIF.

The UK government has also published several roadmaps and frameworks, which outline how key strategies will be translated into expenditure and action:

- The 2017 Industrial Strategy committed to spending 2.4% of UK GDP on R&D by 2027, and the 2020 UK Research and Development Roadmap articulated how this target would be achieved. The Roadmap underlined that the UK’s ODA ‘investment’ in R&D “leverages soft-power influence to position the UK as the partner of choice, securing access to future markets, beyond aid”. It framed LMIC capacity strengthening in similar terms: “ODA funds also support the development of researchers and R&D ecosystems in ODA eligible countries – these are our partners of today and for tomorrow”. It referenced 100 Science and Innovation Network officers working across 40 countries to promote UK research and identify opportunities for collaboration, and three UK “science, technology and innovation platforms” in African regional hubs (based in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa) that “link UK researchers, innovators and entrepreneurs to African policy makers and innovation ecosystems”.

- The 2023 Science and Technology Framework set out the government’s ‘science and technology superpower’ agenda and outlined ten key actions to achieve the goal of becoming “the most innovative economy in the world” by 2030. It also stated aspirations for a UK “diplomatic network with strong science and technical knowledge and in-country networks, and greater international technology leadership”.

- The 2023 Global Health Framework outlined cross-government objectives “to strengthen global health security, reform the global health architecture, strengthen health systems in the UK and globally, and advance the UK’s position as a leader in global health science and technology”, alongside related actions to be taken during the period 2023-25.

4. Findings

Relevance: How relevant are DHSC’s ODA-funded global health research portfolios to the UK’s strategic objectives on global health?

UK government strategies related to global health research have prioritised economic and trade objectives alongside resilience to health threats

4.1 During the period under review, the UK government has generated a wide range of strategy documents related to global health research, a selection of which are set out in Box 5. The government’s science-focused strategies emphasise the need for the UK to build global research and development (R&D) partnerships, with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) characterised as critical partners for the future. Examples include the 2020 Research and Development Roadmap, the 2021 Innovation Strategy, and the 2023 Science and Technology Framework. Meanwhile, other international strategies stress the importance of funding research and innovation to improve health security and health resilience, within LMICs and globally. Examples include the 2021 Integrated Review and its 2023 refresh, as well as the 2022 Strategy for International Development.

4.2 The more recent White Paper on International Development, which was published in November 2023, emphasises the health needs of people in LMICs and opportunities for UK aid to strengthen research leadership and capacity in these countries. The paper specifically highlights the need for development research to be led by the Global South and for research and innovation partnerships to be equitable, noting that research partnerships based on mutually agreed priorities can have significant development impact.

“Long-term, predictable commitment, secure funding and less bureaucratic open competition would increase the ability of researchers to generate locally relevant high-quality evidence and insights, to inform evidence-based national policy and investments.”

White Paper, 2023, p. 121, link

“We will strengthen our bilateral science and technology partnerships with low- and middle-income countries. We will expand our investments and UK private sector support to southern-led, equitable research and innovation initiatives, tapping into the energy and ambition of early career scientists and researchers.”

White Paper, 2023, p. 123, link

4.3 The government’s Global Health Framework was published in May 2023. It was developed jointly by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), along with three other government departments. It pulls together the themes from other UK strategies in its fourth objective, to “advance UK leadership in science and technology, strengthening the global health research base of UK and partner countries, while supporting trade and investment”. Proposed actions in this area centre on the role of UK science and technology, including in international partnerships for health R&D and in preparations for future pandemics. The Global Health Research Unit on Global Surgery, funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), is highlighted as an equitable partnership between researchers in the UK and LMICs.

4.4 We found that, during the period under review, DHSC’s global health research programming has remained closely aligned with core UK priorities and interests in building the science base, supporting R&D, and improving global health security.

In developing its ODA-funded research portfolios, DHSC initially focused on complementing the work of other government departments

4.5 When DHSC received its first ever official development assistance (ODA) allocation for research through the 2015 spending review, the department aimed to complement the work of the former Department for International Development (DFID, now FCDO) and the former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (now the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, DSIT) through a focus on global health security, non-communicable diseases, and health issues primarily affecting poor people in ODA-eligible middle-income countries (rather than low-income countries). DHSC launched its Global Health Research (GHR) portfolio in 2016, managed by NIHR. In interviews with ICAI, some stakeholders perceived NIHR’s engagement as an opportunity to involve the National Health Service in global health research, but this has not featured in DHSC’s ODA-funded research programming.

4.6 An early priority within this GHR portfolio was to pivot UK researchers not previously active in this area towards global health, and to ‘level up’ related research funding by engaging a wider range of UK universities through new NIHR awards. The apparent aim was to broaden the range of UK institutions involved in global health research, expanding UK capacity beyond the tropical medicine schools and other universities that had dominated the field.

4.7 In addition to the GHR portfolio managed by NIHR, DHSC also developed a Global Health Security (GHS) research and innovation portfolio. The main objective of this portfolio, referenced in the 2015 UK Aid Strategy and launched the same year, was to address gaps in research identified during the West Africa Ebola epidemic of 2014-16 and through an assessment of the global burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). To deliver the GHS portfolio, the department opted to engage expert delivery partners in the UK and internationally.

Over time, the GHR portfolio has broadened considerably

4.8 DHSC’s GHR portfolio has evolved since its inception, and it now covers a wide spread of global health needs and challenges. Many of the portfolio’s newer areas of research fill gaps: for instance, there is now research on some neglected tropical diseases. DHSC has also extended its GHR portfolio to include researcher capacity strengthening and communicable disease research, for example to address COVID-19. Several stakeholders highlighted DHSC’s support for research topics that are underfunded internationally, such as accidents and injuries, as well as the department’s strong focus on AMR and its funding for vaccine development and clinical trials that cuts across both the GHR and GHS portfolios.

4.9 The broadening of DHSC’s GHR portfolio has encompassed areas of FCDO strategic and programmatic focus such as mental health and health systems, leading to greater overlap. FCDO and DHSC have sought to clarify their respective roles and areas of collaboration, including through a 2022 presentation to the Strategic Coherence of ODA-funded Research (SCOR) Board managed by the UK Collaborative on Development Research (UKCDR), which covered UK government coherence on global health research. Stakeholders told us that, to avoid duplication with NIHR awards, the Medical Research Council (MRC) has withdrawn its own health systems research funding scheme. DHSC has sought to limit overlap and increase coherence by joining pre-existing partnerships, such as the Joint Global Health Trials Initiative (JGHT), which it now co-funds with the MRC, FCDO and Wellcome. Other partnerships have been co-created in response to emerging priorities, including the Global Effort on COVID-19 (GECO) Health Research, which was developed by DHSC, NIHR, and the MRC under UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) to address areas highlighted in the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) coronavirus research roadmap. In interviews with ICAI, several stakeholders commented on the increased breadth of DHSC and NIHR programming, perceiving a lack of focus or comparative advantage. Some stakeholders also raised the question of whether NIHR’s initial narrow remit had made it more difficult to spend their ODA allocation.

DHSC’s ODA-funded research in LMICs is generally relevant to key health challenges in these contexts

The country case studies and the citizen engagement for this review confirmed the general relevance of both the GHR and GHS portfolios to the health challenges experienced in these contexts, including those that are stigmatised or underfunded. For example, we engaged with researchers working on cutaneous leishmaniasis in Brazil, LGBTQIA+ wellbeing in India, and multi-morbidity in Malawi. The research projects funded through DHSC ODA are focused on identifying and testing appropriate solutions to health issues that disproportionately impact LMICs, often with practical application in clinical or community settings. For instance, in both India and Malawi, ICAI met with teams assessing interventions to improve neonatal care. Some country-level studies form part of longer-term initiatives such as multi-country clinical trials.

4.11 However, ICAI’s citizen engagement research in India and Malawi identified additional community-level priorities that are not well represented in DHSC portfolios. These include longstanding health system challenges such as access to medicines and the quality and affordability of care, and social and environmental determinants of health such as nutrition, water and sanitation. Health systems research is traditionally a stronger feature of FCDO’s research portfolios, although it is now also supported by DHSC. Focus group participants in both countries, when asked about the most pressing community health priorities, often mentioned that although healthcare facilities exist, they do not provide poor community members with access to appropriate and affordable medicines and diagnostic tests.

“The facilities are available, and most people have access to them, but the problem is usually the same, the lack of drugs. And a lot of people here cannot afford to pay the fees that are charged in the private facilities.”

Man, Lilongwe, Malawi

“The private clinic has helped to ease the problem of accessibility, yes, but at what cost? Too many medications given, sometimes wrong.”

Woman, Lilongwe, Malawi

Another frequently raised topic was that poor members of the community often do not receive the respectful and professional healthcare that they need.

“No ambulance came here. I was transported in an E-rickshaw. Even at the hospital, I lay on the bed, screaming in pain, and eventually delivered the baby without medical assistance. The nurse only arrived to cut the cord. No family member was allowed inside, and my pleas for help went unanswered.”

Woman, Sonia Camp, Delhi, India

“My grandson was sick and was turning blue. We took him to [a government hospital], but they didn’t even test him and told us that he had taken contaminated water and would be fine and asked us to take him home. We requested and begged there but no action was taken and later that evening I brought back the dead body of my nine-year-old grandson.”

Man, Sonia Camp, Delhi, India

“The diagnosis of serious ailments is very poor here. Doctors don’t pay attention to patients and hustle through. Our father had cancer, and the hospital kept treating him for TB. Cancer was diagnosed in Rohtak and by then he already had reached the severe stage, and he suffered a lot during his last days.”

Woman, Panipat, India

Finally, focus group participants in both countries highlighted that public health is not only about medical treatment and access to facilities, but also hygiene and nutrition. This point is also made in the academic literature on best practice in global health research, which emphasises the holistic and multidisciplinary nature of global health challenges.

“They [Malawian health authorities] may give us messages on how to prevent getting cholera, but still we are poor here and many times we lack food, and we are forced to eat food that may not be safe to eat. In that regard we still end up getting cholera, and we have lost family members before because the distance to the hospital was too great.”

Man, Dedza, Malawi

“They [Indian health authorities] think it’s our fate to be born in filth and live in it till we die, [so] why would they bother?”

Man, Panipat, India

4.12 The community members contributing to ICAI’s focus group discussions raised issues that are likely to affect many poor people in ODA-eligible middle-income countries, a priority population for DHSC’s global health research programming, as well as those in low-income countries. While ICAI found that DHSC’s ODA-funded global health research in India and Malawi is relevant to health needs in the two countries, ICAI’s citizen engagement research highlights the many barriers to good health that the poorer communities within the two countries continue to face.

DHSC takes account of global expert views when scoping new areas of programming, but has no process for engaging with the research priorities of LMIC governments

4.13 In December 2021, DHSC commissioned an evaluation of its GHR portfolio, which has recently concluded. The portfolio-level evaluation found that more needed to be done to engage with LMIC policymakers at the design stage of GHR programmes and projects. ICAI’s own research found that this applied equally to the overall design of both the GHR and GHS portfolios. The GHS research and innovation portfolio is part of a wider UK government effort to strengthen global health security, preparedness and resilience, which is led from Whitehall and influenced by UK engagement with key international partners, including in fora such as the G7. The GHR portfolio is informed by DHSC involvement in the UKCDR, including its Health Funders Forum. DHSC also serves on the Steering Committee of ESSENCE (Enhancing Support for Strengthening the Effectiveness of National Capacity Efforts) on Health Research, an initiative among international funders to strengthen donor harmonisation and alignment of investments in research capacity. Its working groups have limited LMIC representation.

4.14 DHSC has established an Independent Scientific Advisory Group (ISAG), which influences the overall shape of the GHR portfolio and the scoping of GHR programmes. This group has strong LMIC expert participation, and its members told ICAI that DHSC and its delivery partners listen to and act upon ISAG views. There is no equivalent portfolio-level forum influencing GHS programming. However, DHSC has sought expert input when scoping individual GHS programmes. For example, an expert panel made recommendations on the priority pathogens for the UK Vaccine Network (UKVN) programme and this work was later published. To develop the Global AMR Innovation Fund (GAMRIF), DHSC drew heavily on the O’Neill Review and the recommendations of UN agencies.

4.15 Unlike FCDO, DHSC is not in a position to deploy staff abroad. In India, FCDO science and health advisers are supporting both ODA and non-ODA programming to develop UK-India research partnerships. DHSC also told us about its engagement with FCDO health advisers during several visits to Bangladesh. Aside from this, ICAI found that DHSC had little engagement with UK embassies and FCDO health advisers, who generally lack the capacity to support ODA-funded programmes managed by other government departments. This lack of interface limits the opportunity for DHSC to connect its global health research portfolios with LMIC government priorities and national health research plans, or with FCDO’s bilateral programming and the work of other development partners. We also heard from global and country-level interviews that many national research ethics committees approve all applications to conduct research within their country context, which suggests a lack of agency or capacity. Some LMIC researchers told ICAI that their projects would not have progressed without external support, due to a lack of interest or funding from national ministries of health.

4.16 Engagement with governments and other stakeholders in LMICs is generally researcher-led, with discussions focused on specific projects or undertaken within the context of wider institutional relationships. For example, ICAI documented evidence of longstanding collaboration between the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome (MLW) programme, the government of Malawi and other national institutions, including the principal hospitals and medical training centres. The MLW Policy Unit meets regularly with the Ministry of Health to discuss research project design, findings, and potential impacts.

“MLW respects community structures, and they really try to inform people in an orderly manner of what they are doing. The staff are easily recognisable as they all have proper identification. They have a good rapport with the community through involving chiefs, the HAC [health advisory committee], and us as CAG [MLW institutional community advisory group] and CAB [project-level community advisory board] members.”

Community advisory board member, Multilink project, Malawi

4.17 Project-level engagement with LMIC governments may also occur through community engagement and involvement (CEI) approaches, which have been rolled out across NIHR’s ODA-funded schemes. CEI allows LMIC stakeholders, communities and healthcare users to share their perspectives and inform research on an ongoing basis, particularly during project implementation. In some cases, government is represented within these project-level community advisory groups.

DHSC references ‘equitable partnerships’ as a principle guiding the development and implementation of its ODA-funded research

4.18 DHSC uses the definition of equitable partnerships set out in Box 6 below, which was developed by UKCDR. In discussion with ICAI, stakeholders stressed that equitable partnerships are dependent on research capacity strengthening in LMICs. This connection is made in UKCDR’s guidance, particularly in relation to institutional capacity. UKCDR also notes the importance of inclusive agenda-setting processes, equitable budgets, and engagement with LMIC governments (see Box 6). Within DHSC’s GHR portfolio, this is echoed in NIHR’s guidance to applicants. The NIHR website lists resources from UKCDR and elsewhere, steering research applicants towards actions that support equitable research partnerships. NIHR Call Guidance includes equitable partnerships as a key selection criterion, although specific requirements vary across programmes and across different calls within programmes.

“We expect equity to be strongly reflected in research leadership, decision-making, capacity strengthening, governance, appropriate distribution of funds, ethics processes, data ownership, publication and dissemination of findings.”

Build equitable partnerships, NIHR website, link