Evaluation of the Inter-Departmental Conflict Pool – ICAI Report

Executive Summary

The Conflict Pool is a funding mechanism for conflict prevention activities, managed jointly by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, DFID and the Ministry of Defence. Based on case studies of Pakistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), this evaluation of the Conflict Pool’s Official Development Assistance element assesses whether it has led to a coherent, strategic and effective UK approach to conflict prevention.

Overall Assessment: Amber-Red

The Conflict Pool was established to combine the skills of the three departments in defence, diplomacy and development into a coherent UK approach to conflict prevention. It has proved effective at identifying and supporting worthwhile conflict prevention initiatives and has delivered some useful, if localised, results. It has, nonetheless, struggled to demonstrate strategic impact: it lacks a clear strategic framework and robust funding model; its governance and management arrangements are cumbersome; and it has little capacity for measuring results. While, in the past, the Conflict Pool may have contributed to a more joined-up approach to conflict prevention, the inter-departmental co-ordination role is now played more effectively by other mechanisms. The task of administering the Conflict Pool by consensus across three departments is so challenging that those charged with its management have tended to shy away from harder strategic issues. While we believe that the Conflict Pool is a useful and important mechanism, significant reform is required to enable it to fulfil its potential. This was recognised in the July 2011 Building Stability Overseas Strategy and the recommendations in this report are intended to contribute to ongoing reforms.

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

While the goal of achieving a joined-up approach to conflict prevention is important, it has been only partially successful and this role is now played more effectively by other mechanisms. The Conflict Pool’s multidisciplinary approach to conflict prevention and its comparative advantage in relation to DFID’s larger conflict prevention activities are not well articulated. At the country level, there needs to be a clearer link between high-level objectives and the activities supported.

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

The Conflict Pool functions well as a responsive, grant-making instrument for supporting small-scale peacebuilding activities by local partners in conflict-affected countries. We received very good feedback on its relationships with its implementing partners. It is less effective at concentrating its resources behind the achievement of strategic objectives. It needs to give more attention to choosing the funding model best suited to its specific objectives in different contexts, including leveraging resources from other sources to take pilot activities to scale. The volatile Conflict Pool budget has proved a significant constraint on effective resource use.

Impact

Assessment: Amber-Red

In Pakistan, we observed a range of encouraging results at the activity level and some emerging results at the strategic level. In DRC, while some objectives are being achieved, the activities are unlikely to deliver on their larger goals. We are concerned at the lack of attention to conflict sensitivity and the risks of unintended harm.

Learning

Assessment: Amber-Red

The Conflict Pool has operated for more than a decade without a coherent approach to results management. Reporting on results is limited to the project level and there is no formal mechanism for collecting and sharing lessons and experiences. There are plans to address this through a range of reforms launched in 2011.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The Building Stability Overseas Board should develop a clearer strategic framework specifically for the Conflict Pool, to clarify its comparative advantage alongside DFID (particularly in regional programming) and identify how it will integrate defence, diplomacy and development into a multidisciplinary approach to conflict prevention.

Recommendation 2: By the next Conflict Resources Settlement (starting in 2015-16), the three departments should simplify the management structure for the implementation of Conflict Pool activities, while retaining a tri-departmental approach to strategy setting and funding allocation.

Recommendation 3: At the next spending review, the three departments should work with the Treasury to reduce volatility in the Conflict Pool budget.

Recommendation 4: To maximise its impact, the Conflict Pool should match its funding model to its specific objectives, balancing a proactive approach to identifying partners for larger-scale activities with a flexible and responsive grant-making process for promising local initiatives and paying more attention to leveraging other resources to take pilot activities to scale.

Recommendation 5: The Conflict Pool should adopt guidelines on risk management and conflict sensitivity.

Recommendation 6: The Conflict Pool should develop a balanced monitoring and evaluation system which encompasses both strategic resource management and real-time assessment of the outcomes of specific projects.

1 Introduction

Scope of the evaluation

1.1 The Conflict Pool is a funding mechanism for conflict prevention activities managed jointly by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Ministry of Defence (MOD). It emerged from a joint funding mechanism created in 2001 to bring together the three departments’ expertise in defence, diplomacy and development and to encourage common approaches to addressing conflict around the world. This evaluation assesses whether the Conflict Pool has led to a coherent, strategic and effective approach to conflict prevention by the UK Government.

1.2 The Conflict Pool combines both Official Development Assistance (ODA) and other funds (non-ODA). As the Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI’s) mandate is limited to scrutinising ODA, we have not reviewed individual non-ODA Conflict Pool activities. We have, however, considered them as part of our review of strategy and co-ordination. While the Stabilisation Unit1 is now funded from the Conflict Pool, we did not look in detail at its operations as the UK Government has commissioned a separate review of it. Nor did we examine the Early Action Facility for rapid response to international crises, as this has just been created. We note that DFID also funds conflict prevention activities from the bilateral aid programme. While these are not covered by this evaluation, we consider the comparative advantage of the Conflict Pool as compared to DFID’s other spending on prevention.

1.3 Our evaluation has involved a number of elements. We reviewed the governance and management arrangements of the Conflict Pool, to assess its contribution to strengthening co-ordination and coherence across the three departments. We examined its processes for strategy development, activity selection and funding. We carried out detailed case studies of Conflict Pool activities in Pakistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). These involved field visits to both countries (in January and March 2012 respectively) and interviews with implementing partners and other stakeholders. We consulted at length with the three departments. We also interviewed or received submissions from a range of other stakeholders, including non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and members of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Conflict Issues. While our scope covered ODA-eligible activities delivered by all three departments, in practice the bulk of the activities in the two case study countries were administered by FCO.

Conflict Pool funding

1.4 The Conflict Pool originated in 2001 as two separate instruments (the Africa and the Global Conflict Prevention Pools) dedicated to conflict prevention, jointly administered by the three departments. These were merged in 2007-08 to form the Conflict Prevention Pool, subsequently renamed the Conflict Pool in 2009. This innovative funding mechanism enabled both ODA and non-ODA resources to be programmed jointly, helping the UK to engage in areas such as security sector reform that are only partly classified as ODA. The history of the Conflict Pool is summarised briefly in Figure 1 on page 3.

1.5 The Conflict Pool is funded from the Conflict Resources Settlement 2011-15, which also funds the UK Government’s Peacekeeping Budget. This covers the UK’s assessed contribution (a legal obligation as a member of these organisations) to United Nations peacekeeping, Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) field missions, European Security and Defence Policy military and civilian missions, NATO operations in the Balkans and the International Criminal Courts and Tribunals. Of the Conflict Resources Settlement (£630 million in 2011-12, rising to £683 million in 2014-15), £374 million is set aside each year for peacekeeping. In practice, the UK’s share of peacekeeping costs regularly exceeds this, depending on the scale of operations in any given year and exchange rate fluctuations. Any additional peacekeeping costs above the £374 million allocation are also met from the Conflict Resources Settlement, with the balance available to the Conflict Pool. As a result, funding for the Conflict Pool is volatile, creating significant management challenges.

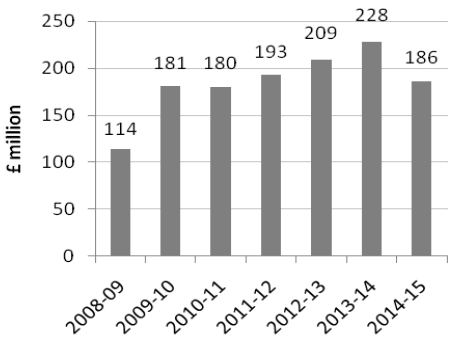

1.6 The Conflict Pool budget for 2011-12 was £256 million. Of this sum, £76 million went towards additional peacekeeping costs, leaving £180 million for programming through the Conflict Pool, as shown in Figure 2.

| Year | Development |

|---|---|

| 2000-01 | Spending Review 2000 establishes the Africa Conflict Prevention Pool (ACPP) and the Global Conflict Prevention Pool (GCPP), which commence operations in 2001. |

| 2004 | The Post-Conflict Reconstruction Unit (PCRU) is created, providing a standing UK civilian capacity for deployment to post-conflict situations. |

| 2007-08 | The ACPP and the GCPP merge to create the Conflict Prevention Pool. A Stabilisation Aid Fund is created to work in 'hot' conflict zones (namely, Iraq and Afghanistan), taking over from the Conflict Pool in these areas. The PCRU is renamed the Stabilisation Unit. |

| 2009 | The Stabilisation Aid Fund is merged into the Conflict Prevention Pool and renamed the Conflict Pool. |

| 2010 | The Strategic Defence and Security Review commits 30% of UK aid to fragile and conflict-affected states and scales up Conflict Pool resources. |

| 2011 | The Building Stability Overseas Strategy is adopted, providing an overarching policy framework for UK efforts to address instability and conflict overseas. |

1.7 The Conflict Pool budget is allocated to five geographical programmes (Africa; Afghanistan; the Middle East and North Africa; South Asia; and Wider Europe) and one thematic programme (Strengthening Alliances and Partnerships). The Conflict Pool also funds the Stabilisation Unit.

1.8 Of the geographical programmes, Afghanistan receives by far the largest allocation of resources, at 38% (£75 million expenditure in 2010-11 against an allocation of £68.5 million). After Afghanistan, the top countries by 2010-11 expenditure are Pakistan (£13 million), Somalia (£7.9 million), Sudan (£7.2 million) and Sierra Leone (£7.1 million). In 2011-12, £8.5 million was allocated to Libya. In the current financial year, additional resources are being allocated to Syria from the Early Action Facility. As can be seen, the country allocations are quite small relative to the scale of the conflicts they seek to address.

1.9 Funding decisions are made jointly by the three departments on a consensual basis through programming committees established either at country or headquarters level. These committees typically involve DFID conflict advisers, FCO first secretaries and defence attachés overseas and, in the UK, FCO and MOD desk officers. Each department may propose activities for funding from the Conflict Pool. If accepted, implementation of the activity is assigned to that department, to be managed according to its own rules and procedures. While the Conflict Pool budget is allocated initially from the Treasury to DFID, it is then divided between the three departments according to the proportion of activities and expenditure assigned to each in any given year.

Source: Conflict Pool annual returns 2008-09 to 2011-12; Spending Review 2010 settlement for 2012-154

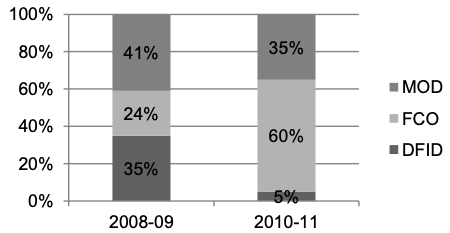

1.10 As a result, the share of Conflict Pool funds managed by each department varies over time. As Figure 3 on page 4 shows, in 2008-09, the split between the three departments was fairly even, with MOD spending 41%, DFID 35% and FCO 24%. By 2010-11, DFID expenditure was only 5% of the funds, while FCO expenditure had risen to 60%.

Source: Data provided to us by the Conflict Pool Secretariat

2 Findings

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.1 This section of the report looks at whether the Conflict Pool has clear and relevant objectives, at both global and country levels.

Promoting UK Government coherence

2.2 In the field of international conflict, it is often observed that prevention is better than cure.5 The costs of major post-conflict interventions are so large in both human and financial terms that effective investments in conflict prevention should provide good value for money by comparison. This proposition is, however, rarely put into practice. Funds are usually mobilised only once international crises reach the headlines, when it is too late to talk of prevention. The return on investment of conflict prevention activities is difficult to assess with any precision. Furthermore, as a multidisciplinary activity spanning diplomacy, defence and development (see Figure 4), conflict prevention does not fit comfortably within the mandate of any one government department or agency.

‘Work to prevent conflict is most likely to succeed when it marshals diplomatic efforts with development programmes and defence engagement around a shared strategy… We must work to address the causes of conflict and fragility; support an inclusive political system which builds a closer society; and strengthen the state’s own ability to deliver security, justice and economic opportunity.’

Source: Building Stability Overseas Strategy, 2011, paragraph 9.1

2.3 The UK Government created the Conflict Pool to address this deficit. Having a dedicated pool of funds administered jointly by the three departments creates the scope for timely and sustained investments in conflict prevention. It also encourages the three departments to work together, combining their respective expertise in diplomacy, defence and development. These are extremely important objectives that continue to be relevant today. The stakeholders we consulted, including UK parliamentarians and NGOs with an interest in conflict issues, uniformly endorsed the importance of these objectives.

2.4 The Conflict Pool appears to have been the first such dedicated instrument for conflict prevention to be created internationally. It was followed by the UN Peacebuilding Fund (2006), the European Union Instrument for Stability (2007)6 and a number of similar initiatives by other bilateral donors. Some observers credit the Conflict Pool as having been an influential model for these later developments.

2.5 The objective of promoting a coherent and multidisciplinary approach to conflict prevention was both novel and ambitious but has only been partially achieved. Until the adoption of the Building Stability Overseas Strategy7 (BSOS) in July 2011, the Conflict Pool operated without an overarching strategy document. Its approach to combining defence, diplomacy and development into a coherent approach to conflict prevention was left to emerge in an incremental way through its individual funding choices. In the absence of a more deliberate approach, there has been a tendency for the three departments to divide the resources between them, rather than work alongside each other. We saw few examples of activities that were genuinely multidisciplinary in nature.

2.6 We also found only limited contribution by the Conflict Pool to improving overall strategic coherence across the departments. Each department brings its own mandate and interests to the table. Decision-making is by consensus and tends to be slow and painstaking. The task of administering funds tri-departmentally is so challenging that those charged with the management of the Conflict Pool have tended to shy away from the harder strategic issues.

2.7 There is no question that inter-departmental coherence has improved in recent years but this is not clearly attributable to the Conflict Pool. It is apparent that the three departments now share a common set of UK objectives, particularly in countries that are strategically important. This has come about through a range of initiatives, including the creation of the National Security Council. There are now common delivery plans and management arrangements in many countries. We observed good interaction between the departments at the country level, where they have clear incentives to share information and collaborate. While the creation of the Conflict Pool may have made an early contribution to improving coherence, this role is now played by other processes and mechanisms.

Overall strategy

2.8 There appear to have been a number of reasons why the Conflict Pool has not treated strategy development as a priority. Until recently, its unpredictable funding allocation has worked against strategic planning. It comes under pressure to respond rapidly to crisis situations, leading to a preference for short-term decision-making. Strategy development by consensus among the three departments is challenging and time-consuming, resulting in a preference for operational flexibility over strategic planning.

2.9 The BSOS of July 2011 is the first overarching UK strategy on conflict issues.8 It is broader in its scope than the Conflict Pool and covers early warning, rapid response and other conflict-related interventions, including diplomacy, humanitarian action and development assistance to fragile states. Only two paragraphs in the BSOS are devoted specifically to the Conflict Pool (see Annex). They include commitments to scaling up its resources, introducing multi-annual planning and strengthening programme management and results orientation.

2.10 The BSOS outlines three broad categories of Conflict Pool programming:

- free, transparent and inclusive political systems;

- effective and accountable security and justice (including through defence engagement); and

- building the capacity of local populations and regional and multilateral institutions to prevent and to resolve the conflicts that affect them.

2.11 Specifying three categories of support was intended to provide greater focus, allowing the Conflict Pool to screen out less strategic programming choices. The three categories are, however, very broad and overlap substantially with DFID programming. They do not clearly present the comparative advantage of the Conflict Pool (see paragraph 2.15 on page 7 for our views on its comparative advantage). The categories have not, in practice, been used to guide programming choices.

2.12 Since the BSOS, the Conflict Pool has initiated some important reforms. From 2012-13, it has begun allocating funds to regional and country programmes on a multi-annual basis, giving them considerably more scope for strategic planning, although grants to implementing partners are still made on an annual basis. A new planning process has been introduced, modelled on DFID’s Bilateral Aid Review.9 Prior to the first multi-annual funding allocation round, each regional programme was required to develop a ‘results offer’ setting out the impact it hoped to achieve and its strategy for doing so. Not surprisingly, the first round of regional strategies involved an element of ‘retro-fitting’ or working backwards from an established set of activities. They were, nonetheless, welcome developments, setting out a core of strategic thinking at the programme level that the Conflict Pool will be able to build on over the remainder of the funding cycle.

2.13 Under the new planning process, Conflict Pool strategy continues to be developed from the bottom up, from the country and regional levels. We accept that this is broadly appropriate, given the diversity of conflict situations in which the Conflict Pool operates. We also observed that the Conflict Pool’s main strategic planning capacity is located at the sub-regional and country levels, particularly among the Regional Conflict Advisers, whom we found to be well-informed on local conditions and a strong technical resource.

2.14 A purely bottom-up planning process, however, leaves some significant strategic gaps. The Conflict Pool lacks an overall programming approach or philosophy, providing little or no strategic or technical guidance to staff. There is no strategy on the preferred scale of interventions (i.e. whether the Conflict Pool should concentrate its resources or support multiple smaller initiatives; how innovative interventions developed through Conflict Pool funding can be taken to scale). We found that Conflict Pool staff were often unclear as to what level or type of results they should aim for i.e. small-scale, localised impact on particular communities, strategic impact on larger conflict dynamics, or a combination. While one of the strengths of the Conflict Pool should be its ability to engage with regional conflict dynamics through cross-border activities, this is not identified as a priority or well supported by its programming approach.

2.15 Perhaps most importantly, the role and comparative advantage of the Conflict Pool in relation to DFID are not articulated. Since the creation of the Conflict Pool, the volume of conflict-related expenditure within DFID’s bilateral aid programme has increased substantially. At the same time, DFID has largely disengaged from a direct spending role in the Conflict Pool, with the administrative burden of accessing relatively small sums through the Conflict Pool an apparent disincentive. With the Conflict Pool no longer the sole or even primary UK instrument for conflict prevention, it needs to be clear about its role and comparative advantage and to concentrate its resources accordingly. We found that there are indeed a number of areas where the Conflict Pool has a potential comparative advantage over DFID acting alone, including:

- the ability to mobilise small-scale, flexible assistance in high-risk and politically sensitive areas;

- the ability to fund pilot or demonstration projects to attract funding from other sources in order to take them to scale;

- the ability to work across national borders to address regional conflict dynamics;

- the ability to fund projects that are not classed as ODA or which combine ODA and non-ODA in strategic ways; and

- the ability to combine defence, diplomacy and development into multidisciplinary approaches.

2.16 If the comparative advantage were more clearly articulated and reflected in guidance for staff, it would help to promote a clearer strategic orientation for the Conflict Pool.

Country programmes

2.17 The Conflict Pool’s approaches for responding to particular conflicts are necessarily varied. Our observations here are limited to our two case study countries of Pakistan and DRC.

Pakistan

2.18 Pakistan is of strategic significance to both the UK and the international community. The UK has a number of objectives specific to Pakistan, including reducing the terrorist threat to the UK, promoting regional engagement, helping to consolidate democracy and addressing internal threats to its stability. These objectives are supported jointly by MOD, DFID and FCO through a UK Integrated Delivery Plan for Pakistan.

2.19 The Conflict Pool in Pakistan contributes to these objectives through three strands of activities, focussing on Afghanistan/Pakistan relations and border areas, India/Pakistan relations and internal Pakistan issues. Each of these strands has a number of objectives (see Figure 5 on page 8). There are approximately 50 individual activities, each contributing to one or more of the objectives. The funding allocation is £13 million for 2010-11, giving an average project size of around £250,000. Just over half of the projects are below £100,000 in size.

| Strand | Objectives |

|---|---|

| 1. Afghanistan/Pakistan relations and border areas |

|

| 2. India/Pakistan relations |

|

| 3. Pakistan internal issues |

|

2.20 We saw many examples of relevant and strategic activities in Pakistan. Some of the strengths of the programme include its ability to identify and to work with influential voices in Pakistan, India and Afghanistan in ‘Track 2’ dialogue.11 Other strengths were its community-based activities in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and its support for electoral reform. A major challenge in Pakistan has been identifying credible implementing partners. This in turn limits the strategic choices available. We noted that there are a number of objectives in the Conflict Pool strategy for Pakistan that are yet to be matched with convincing partners and activities. This challenge also means that the Conflict Pool has a tendency to continue working with its established partners each year, even where their activities are not highly strategic.

2.21 The challenge of identifying partners also means the Conflict Pool struggles to implement its activities on a scale commensurate with its objectives. For example, it supports some activist groups which campaign against political extremism by organising civic events with young people. While this is relevant and worthwhile, it is done on far too small a scale to have a real prospect of countering the forces of radicalisation. Similarly, we were not convinced that some planned interventions into policing in Karachi were of a type or scale that could deliver results in such a challenging area (see the discussion on scale of impact in paragraphs 2.54-2.55 on page 14). We acknowledge that small-scale activities can be highly strategic in the right circumstances but we would expect to see a stronger assessment of what scale of intervention is appropriate for different types of objectives. Where the Conflict Pool supports innovative pilots, we would like to see a more considered strategy for leveraging resources from other sources in order to take them to scale.

2.22 Through the results offer process, the country management team has begun to articulate more clearly the linkages between individual Conflict Pool activities and broader UK goals in Pakistan. It has also begun to develop theories of change for each of its three programming strands. As part of the results offer process, these were challenged by a ‘Star Chamber’ of officials from the three departments. The officials found that project outputs and intended results were not clearly connected. At the time of our visit to Pakistan, the results offer was being revised accordingly. This is a welcome increase in the rigour of Conflict Pool programming.

Democratic Republic of Congo

2.23 The 1998-2003 conflict in DRC was the deadliest in Africa’s history, involving eight nations and about 25 armed groups and resulting in the deaths of over 5 million people. The conflict was formally brought to an end with the establishment of a transitional government in 2003. Since then, however, significant levels of violence have continued in eastern Congo, with atrocities against the civilian population perpetrated by both government forces and rebel groups.

2.24 The Conflict Pool’s Regional Conflict Prevention Strategy for Central and East Africa sets as one of its objectives: ‘armed conflict definitely resolved and security significantly improved in Eastern DRC’.12 The results offer for the region, finalised in December 2011, sets the objective of protecting the conflict-affected population from the official defence forces and other armed groups. The Conflict Pool programme for DRC is organised into three pillars:

- support for stabilisation in the East;

- support for creating the conditions for defence reform; and

- support for the UN peacekeeping mission (MONUSCO), through secondments.

2.25 The Conflict Pool allocation for DRC was £2.8 million in 2010-11, of which £1.2 million was ODA. In 2011-12, the ODA-eligible budget was reduced to £800,000, compared to a DFID country programme of £133 million. While its resources are small, the Conflict Pool in DRC has been able to address some ambitious objectives by channelling its funds through international partners and processes.

2.26 In recent years, its three main ODA activities have been:

- financial and material support to MONUSCO for disarmament, demobilisation, repatriation, reintegration and resettlement (DDRRR) of foreign armed groups in the East;

- secondments to the European Union Advisory and Assistance Mission (EUSEC) to support security sector reform, particularly payroll management for the national army; and

- a (now completed) DFID-led pilot project that aimed to reduce abuses of the population by the Congolese army by improving the living conditions of soldiers and their families.

2.27 While these objectives are clearly relevant, some of the assumptions behind them have proved unrealistic. Developed after the establishment of the transitional government, when the prospects for peacebuilding seemed much more positive, the Conflict Pool strategy in DRC assumed that fighting in the East would recede, that the national army would return to barracks and that the government would support security sector reform. The reality has turned out to be very different. The continued presence of Congolese and foreign rebel groups and the persistence of parallel lines of command within the army mean that the Conflict Pool is still dealing with a situation of active conflict. As a result, any progress on DDRRR with one rebel group creates a vacuum that is quickly filled by others. The DRC Government has proved unwilling or unable to move forward with security sector reform and elements of the national army still support themselves through predatory behaviour towards the civilian population. As a result, the prospects for any significant conflict prevention gains from the current Conflict Pool strategy are slim.

2.28 Given these circumstances, it is notable that the Conflict Pool has not sought to change or diversify its strategy – for example, by working with civil society organisations or international NGOs. By way of comparison, DFID has responded to the lack of political support by increasing its investments in the direct delivery of results for local communities. Reduced funding and the lack of credible Congolese partners seem to have inhibited the Conflict Pool from exploring alternative options. Conflict Pool staff also stress the importance of the relationships they have built with the two major international partners, MONUSCO and EUSEC, which give the UK significant influence. We note, however, that influencing international partners is merely a means to an end, not an objective in its own right.

Delivery

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.29 This section looks at the governance and management arrangements of the Conflict Pool and how well it has functioned as a funding instrument.

Funding model

2.30 We found there to be uncertainty in the Conflict Pool as to whether its role is to support diverse, small-scale initiatives aiming for localised impact, or to concentrate its resources in the hope of achieving strategic impact on larger conflict dynamics. This uncertainty is also present in its funding model.

2.31 On some occasions, the Conflict Pool acts as a responsive grant-making mechanism, supporting local organisations for peacebuilding activities. At other times, it is proactive in seeking out and procuring partners capable of implementing larger-scale initiatives. While there may be a good case for both approaches, we found a lack of clarity within the Conflict Pool as to how best to deploy its resources so as to achieve different types of objectives.

2.32 In many ways, the Conflict Pool is at its best when it acts as a venture capital fund for peacebuilding activities. Its strengths are its willingness to act quickly and flexibly in complex and dynamic environments and its ability to identify and nurture promising conflict prevention initiatives.

2.33 We were impressed by the approach taken by the Conflict Pool to doing this, in particular by FCO staff. They are skilled at identifying promising partners and encouraging them to develop their programmes in useful directions. They support their partners actively on problem analysis and activity design, while giving them the flexibility to adapt their activities as necessary. They build relationships of trust that leave space for debate and occasional disagreement.

2.34 The feedback from implementing partners on the quality of the funding relationship was uniformly positive, comparing the Conflict Pool favourably to other donors who were too rigid or intrusive in their approach. This flexibility is a clear asset in the conflict prevention field and represents the Conflict Pool’s core strength. The Conflict Pool is also discreet with its funding; it does not require partners to acknowledge publicly the UK’s support where that would be unhelpful.

2.35 There are, however, limitations to what can be achieved through this funding model. When the Conflict Pool acts as a responsive, grant-making fund, the extent of its engagement in any given area is determined by the number and quality of proposals that it receives. While it can specify its objectives, it may not receive credible proposals on a sufficient scale to achieve them. Instead, the model tends to produce a proliferation of small-scale activities that, however worthwhile, are unlikely to have strategic impact. In Pakistan, the Conflict Pool has supported as many as 60 separate activities for a budget of only £13 million. By contrast, DFID Pakistan has fewer than 20 programmes for a budget of over £200 million. New partners are usually taken on gradually with small grants that are increased in later years as a track record of delivery is built up. This leads to a clear preference for repeating activities year after year with established partners. It makes it difficult to keep the portfolio as a whole flexible and responsive.

2.36 If it is to become more strategic in orientation, the Conflict Pool needs the ability to concentrate its resources behind key objectives through active procurement of partners for larger interventions. To some extent, the Conflict Pool has already begun to do this. In Pakistan, for example, its activities in the area of control of illicit trade are carried out by the United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime and the UK’s Serious Organised Crime Agency – both organisations capable of acting on a larger scale.

2.37 We would not wish to see the Conflict Pool lose its ability to act as a venture capital fund for smaller-scale activities. In the area of conflict prevention, smaller-scale interventions can be very strategic and some parts of the Conflict Pool may not be suitable for scaling up. It should, however, give more consideration to the funding model and scale of intervention best suited for pursuing its various objectives and to concentrating its resources where necessary for strategic impact.

Governance and management arrangements

2.38 As a tri-departmental instrument, the Conflict Pool has a complex and rather cumbersome organisational structure, summarised in Figure 6. Decision-making is by consensus across the three departments. The high transaction costs associated with consensual processes are arguably a necessary part of inter-departmental working. There seems to be, however, considerable scope for simplifying the structure. A recent National Audit Office report cited an example of a funding decision that required nine signatures prior to approval. It concluded that there is ‘scope to improve the efficiency of this resource allocation process by streamlining and devolving responsibility down where capacity exists’.13

2.39 In each programme, a Senior Responsible Owner (SRO) is formally accountable for expenditure and results. In practice, however, the structure does not facilitate strong accountability relationships. The SROs are very senior staff from the three departments and the Conflict Pool is only a small part of their responsibilities. They are a long way from decision-making at the country level (particularly decisions taken by other departments) and have limited ability to assure the quality of funding choices.

2.40 Until the creation of the Building Stability Overseas Board in 2011, there was little capacity within the management structure for strategic planning. The Conflict Pool Secretariat is kept extremely busy with managing routine processes, particularly the financial management challenges associated with its variable funding. It has, therefore, had little time to spend on developing programming guidance or supporting results management at country, regional or global levels. While the Secretariat provides good support to the geographical programmes on administration and financial management, it lacks both the resources and the technical expertise to support activity design and monitoring and evaluation.

| Year | Composition and responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Building Stability Overseas Board | Created in autumn 2010 to provide strategic direction to the BSOS. Made up of the Conflict Directors of each department, it sets the overarching strategy for the Conflict Pool and oversees its reform. It has oversight responsibility for implementation of the BSOS as a whole. |

| Conflict Pool Secretariat | A five-member tri-departmental team which supports the Board on Conflict Pool-related matters. The Secretariat monitors finances and prepares financial reports (including ODA reporting) and provides guidance to programme teams. The Secretariat occasionally meets as the Secretariat Plus, including more senior staff, to address strategic issues. |

| Programme Boards | There is a Programme Board for each of the five geographical programmes (Africa; Afghanistan; South Asia; the Middle East and North Africa; and Wider Europe) and the Strengthening Alliances and Partnerships programme. The Programme Boards have management responsibility for their respective programmes, including approving expenditure decisions. Programme Boards can determine the level of delegation of expenditure authority to country level. Each Programme Board is chaired by an SRO who is accountable for the delivery of results. Each Programme Board is supported by a Programme Manager with administrative responsibility for the programme. |

| Regional Conflict Advisers | Regional Conflict Advisers are employed as needed, from Conflict Pool funds, to provide specialist conflict prevention expertise. |

| In-Country Teams | These vary in structure according to the size of the portfolio but typically include an inter-departmental committee that makes funding recommendations to the Programme Board. Senior management is provided by FCO, MOD or DFID staff on a part-time basis, with local project management staff employed as needed. |

Project management

2.41 While there are some central guidelines produced by the Conflict Pool Secretariat, management practices vary substantially across the departments. Individual activities are assigned to particular departments, which manage them according to their own rules and procedures.

2.42 For FCO, which is not traditionally a spending department, the Conflict Pool presents some significant management challenges. Its procedures are much lighter than those used by DFID and it has an institutional culture of relying on relationships of trust and oral reporting rather than formal project management systems. While this flexibility is sometimes an asset, we find that FCO needs to invest more in building up its project management capacity, particularly as it takes an increasingly prominent role in the management of the Conflict Pool.

Financial supervision

2.43 The Conflict Pool’s financial oversight of its partners appears to be appropriate and in proportion to the level of risk. Inevitably, many of its local partners have limited financial management capacity. Although it does not undertake formal due diligence assessments, it manages fiduciary risk through close supervision of its implementing partners and by building up relationships with them over time. New partners are usually brought on with relatively small grants and strict reporting requirements. Once they have built up a track record of successful delivery, they may qualify for more substantial grants. Financial reporting requirements are detailed in project agreements and are generally on a quarterly basis, with annual audit requirements for larger projects (for example, in Pakistan, for annual grants over £200,000).

2.44 FCO’s guidance on fraud states that there is a zero-tolerance approach to fraud and requires staff to satisfy themselves that implementing partners follow sound procurement processes. There is no specific guidance on how they should do this and, in practice, it is left to the judgement and capacity of individual FCO staff. We came across one instance, in Pakistan, where quarterly financial reporting by a project partner revealed a series of financial irregularities, including charges made improperly to the project. FCO swiftly detected the irregularities and suspended the project. A decision was later taken to reinstate the project with stricter reporting requirements and additional monitoring, after the partner had sought and received assistance from professional accountants to strengthen its financial management. The Conflict Pool in Pakistan has recently engaged a UK-based NGO to carry out assessments of its project partners to identify any other weaknesses in financial management.

2.45 There are particular difficulties associated with monitoring the implementation of activities in insecure areas where UK government staff are unable to travel. We noted that Conflict Pool staff were using a range of measures to satisfy themselves that activities were being delivered as reported. In Pakistan, one implementing partner carrying out opinion polling in FATA had instituted a process of random telephone calls to surveyed households as a safeguard against fraudulent behaviour by enumerators.

2.46 Overall, given the fact that the Conflict Pool often funds small NGOs operating in difficult environments, we find the level of fiduciary control to be appropriate. It would, however, be advisable for the Conflict Pool to establish clearer rules and guidance for staff in-country as to what level and type of financial supervision is appropriate to different types and size of funding arrangement. There should also be clearly established procedures to follow where financial irregularities are detected. Finally, in larger country programmes such as Pakistan, we are concerned that Conflict Pool staff may not have enough time for direct monitoring of and support to all the project partners. It would therefore be appropriate to engage external partners (NGOs or companies) to carry out assessments of partner financial management capacity and provide capacity-building support.

Budget volatility

2.47 Because the Conflict Pool and the Peacekeeping Budget are funded from the same financial settlement (see paragraph 1.5 on page 2), the Conflict Pool suffers from a volatile and unpredictable financial base. This results in significant management challenges. In 2009-10, for example, a sharp rise in peacekeeping costs led to a reduction of around £80 million in the resources available for Conflict Pool programming. This forced a series of in-year adjustments, including trimming £25 million (37%) from the Africa Programme, more than halving the budget for arms control and support to international organisations from £15.3 million to £6.5 million and discontinuing the £1.8 million Americas Programme. A number of country programmes (Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire and most of the Southern African programmes) were closed.

2.48 The original rationale for funding both peacekeeping and the Conflict Pool from the same financial settlement was that successful conflict prevention activities would lead to an eventual reduction in UK peacekeeping costs. If prevention indeed proved to be cheaper than cure, then the pool of resources available for conflict prevention should increase over time.14 This reasoning would hold true only over a very long time period. In practice, the volatility caused by this arrangement has significantly undermined the utility of the Conflict Pool as an instrument. Officials from across the three departments told us that budget volatility undermines planning and increases the management burden. When combined with cumbersome management processes, it creates disincentives for staff from the three departments to engage seriously with the Conflict Pool. We would suggest that the three departments work with the Treasury to reconsider this arrangement at the next spending review.

2.49 In addition, the difficult operating environment in many conflict-affected countries means that many activities cannot be implemented on schedule. As unused budget allocations are usually lost, pressure to spend unused funds can lead to poor programming choices. With the shift to multi-annual funding rounds, we encourage the three departments to adopt greater flexibility in budgetary procedures, working with the Treasury, to address this unhelpful pressure.

ODA and non-ODA resources

2.50 One of the comparative advantages of the Conflict Pool is its ability to combine ODA and non-ODA expenditure. This enables it to engage in areas such as security sector reform that combine ODA (for example, investments in civilian oversight of the military) and non-ODA (for example, direct support for the military) funding.

2.51 In the past, however, the Conflict Pool was set excessively high ODA targets while its non-ODA funding was absorbed by rising peacekeeping costs (see Figure 7). By 2010-11, the proportion of the Conflict Pool budget available for non-ODA spending had been reduced to only 15%, most of which was absorbed by the UK’s voluntary contribution of around £18 million per year to the UN mission in Cyprus. This significantly limited the Conflict Pool’s ability to make effective use of non-ODA expenditure. Since 2010-11, a more reasonable ODA target has been in place.

Until 2010-11, the Conflict Pool was set an excessively high target for ODA expenditure. As peacekeeping costs rose, absorbing the non-ODA allocation, non-ODA expenditure was reduced to a minimal level. In the current expenditure review, the ODA target (now a mandatory ring fence) has been adjusted downwards to 50%.

2.52 As a result, MOD has had an incentive to class more of its Conflict Pool expenditure as ODA, leading to some disagreements over classifications. Before 2010, the geographical programmes reported in aggregate on their ODA expenditure to the Conflict Pool Secretariat, with no checking process. Since 2010, when ODA was made part of UK national statistics, the classification has been more rigorous. Each programme is required to list the projects it claims as ODA and these are screened individually by the Conflict Pool Secretariat. We examined the 2010 ODA return16 in some detail and found that the screening system appears to be largely effective.17

Impact

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.53 This section looks at the impact of Conflict Pool programming on levels of conflict and conflict risk. It is not possible to make an overall assessment of impact across the Conflict Pool based on our two case studies. This section, therefore, sets out our findings in relation to Pakistan and DRC.

2.54 The question of the appropriate level to look for impact is critical to any evaluation of the Conflict Pool. Many of the Conflict Pool objectives (e.g. improving India–Pakistan relations or security-sector reform in DRC) are extremely ambitious relative to the scale of the programming. It would be unreasonable to hold the Conflict Pool accountable for progress at this level. On the other hand, a selection of worthwhile activities that made no measurable contribution to these high-level goals would be a poor return on the investment. Figure 8 shows how ‘theory of change’ analysis can be used to identify mid-level results (‘enabling conditions’) to link project outputs to higher-level objectives.

2.55 Using this logic, we would expect to see three levels of impact from Conflict Pool programming:

- First level: a range of relevant, localised impact at the activity level, particularly where catalytic in nature;

- Second level: plausible contribution to high-level objectives through progress in putting in place enabling conditions for peacebuilding and conflict prevention; and

- Third level: a more coherent and effective approach to conflict prevention by the UK Government.

Pakistan

2.56 In Pakistan, we saw a range of encouraging results at the first level but on a fairly limited scale relative to the wider UK objectives. The areas of impact that struck us as most significant were as follows.

2.57 In the India–Pakistan strand of work, the Conflict Pool has funded a number of NGOs and think tanks to promote unofficial dialogue among opinion leaders, including parliamentarians, in both countries. The 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai caused the official India–Pakistan dialogue to break down. Events and processes supported by the Conflict Pool provided an alternative channel of communication, helping to prevent a complete rupture in the relationship between the two countries. The process contributed to the resumption of official dialogue in February 2011, with joint declarations that it should be ‘uninterrupted and uninterruptible’. It is, therefore, plausible that modest expenditure by the Conflict Pool helped to defuse a potentially dangerous situation and identify ways for resuming India–Pakistan dialogue.

2.58 The Conflict Pool also made a small contribution to promoting moderate voices in the media on India–Pakistan relations. Against a background characterised by the ongoing influence of radical voices, however, it is unlikely that this was done on a sufficient scale to generate real impact.

2.59 The Conflict Pool has been supporting dialogue between the Pakistan military and parliament, to promote mutual understanding. Its activities have helped to support parliamentary oversight of the military. In 2011, the defence budget was discussed by the National Assembly Standing Committee on Defence ahead of the budget debate. A number of military–parliament dialogues were held, supported by research papers, to address civil–military relations and Pakistan’s defence and security interests. Some formerly taboo subjects, such as the military’s commercial investments, were raised. Against a history of military coups, improving civil–military relations will require major changes in military attitudes as well as increases in capacity on the civilian side. It is, therefore, a long-term endeavour. These were, however, promising beginnings in an important area.

2.60 Throughout Pakistan’s modern history, FATA have been administered under stringent emergency power regulations, outside the democratic process. The Conflict Pool has supported a set of activities to introduce democratic governance in FATA, in order to reduce space and support for militant groups. It has supported regular opinion polling in FATA, to gauge levels of public support for Pakistan government institutions and for militant groups. This has built an evidence base that the Conflict Pool and others can use to design peacebuilding interventions.

2.61 The Conflict Pool has worked with a number of partners to promote discussion among government officials and political parties on the status of FATA, supported by public information and media campaigns. Conflict Pool projects led to the creation of a Political Parties Joint Committee on FATA Reform. This was instrumental in facilitating two recent reforms: a Presidential Order permitting political parties to operate in FATA for the first time; and amendments to the Frontier Crimes Regulations, among other things limiting collective punishment and introducing rights of appeal. The Conflict Pool has also been working with local communities to make them more receptive to the extension of Pakistani civilian government into FATA. It has established a series of ‘FATA Reform Councils’ made up of traditional and religious leaders, professional and business people. It has trained them in networking and advocacy and the promotion of civic engagement in local government. While there are many other actors and influences in this area, it is plausible that the Conflict Pool has made a significant contribution.

2.62 The Conflict Pool supported the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) on electoral reform, during a period when other donor support for elections was unavailable. IFES worked with the Pakistan Electoral Commission on a series of important reforms to the electoral system and on the preparation of a new electoral register. Various stakeholders expressed the view that these reforms had significantly increased the credibility of the electoral process.

2.63 Finally, the Conflict Pool has helped to build the capacity of community-based organisations (CBOs) in various parts of the country to advocate human rights and good governance and act as a counterbalance to extremist voices. For example, one project, completed in September 2011, identified 392 CBOs, carried out capacity assessments and provided customised training on human rights and democratic governance, as well as organisational capacity. These CBOs then carried out a range of advocacy campaigns on issues ranging from the quality of local services to resolving local land disputes. They also campaigned for the creation of sporting and cultural opportunities for young people and the elimination of forced marriage of girls. The impacts are inevitably scattered and localised. We were, however, informed that one of the effects of radicalisation in Pakistan is that it inhibits alternative forms of social and cultural life and civic engagement. In helping to preserve and develop other community interactions, these local initiatives make an important contribution to peacebuilding.

2.64 Overall, this represents a good set of results at the activity level. The question is whether the results are on a sufficient scale to make a strategic contribution to the Conflict Pool’s larger goals. As one informed observer put it to us, there are so many drivers of conflict at play in Pakistan that the Conflict Pool could be highly successful at the activity level without achieving any overall reduction in conflict.

2.65 We conclude that there has been some impact at the second level – a plausible contribution to high-level objectives through progress in putting in place enabling conditions – although it has not been well measured or reported. The scattered nature of the portfolio also means that the programming generally lacks the scale or intensity required for substantial impact. Concerning the third level – a more coherent and effective approach to conflict prevention by the UK Government – we saw little evidence that the Conflict Pool had brought together defence, diplomacy and development approaches in a strategic way.

2.66 Assessed on its own, the Pakistan programme would merit a Green-Amber score for impact.

Democratic Republic of Congo

2.67 In DRC, the interventions we saw were competently run and largely successful at delivering their immediate objectives, although they were taking more time and resources than had been expected. In a very difficult country environment, however, they were largely failing to advance the Conflict Pool’s broader strategic goals.

2.68 Through its financial and personnel contributions to EUSEC, the Conflict Pool has been helping to establish effective administration of the army so that soldiers receive regular pay. Without regular pay, soldiers are more likely to support themselves through predatory behaviour towards the local community. The EUSEC programme has helped to separate control of the payroll from the military chain of command and to introduce identity cards for soldiers to reduce payroll fraud. According to EUSEC’s own reporting, 95% of soldiers are now integrated into the payroll system. There has also been a range of other reforms, including improved training of soldiers and new codes of conduct.

2.69 While funds for salaries are now regularly transferred to garrison level, it is not known whether the funds are actually reaching the soldiers. There is also no evidence of improvement in behaviour by the army, particularly in the East. The programme has, therefore, made some progress on putting in place one of the enabling conditions (an effective payroll system) for improved behaviour by the military. In the absence of wider progress on security sector reform, however, it has had no overall impact on the protection of civilians.

2.70 The Conflict Pool has supported MONUSCO’s work on demobilisation of foreign fighters through financial contributions designed to fill specific operational gaps – for example, by funding communications activities in support of demobilisation operations. MONUSCO has achieved some success in demobilising and repatriating foreign (principally Rwandan) combatants and their families from one of the major rebel groups, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR). Some 5,000 fighters were demobilised between 2009 and 2011, constituting around half of the force. MONUSCO informed us, however, that there had been no observable impact from the demobilisation on levels of conflict in the relevant areas. Though specifically targeted by the programme, the command of the FDLR remains largely intact and is now recruiting new fighters and forming alliances with other rebel groups.

2.71 One of the guiding principles for conflict-related programming is that it should be conflict sensitive, avoiding unintended harm.18 In practice, this means that conflict analysis is used to identify possible negative consequences of interventions in conflict-affected areas and programmes are designed so as to minimise any unintended harm. We were surprised to find no requirements for, or guidance on, conflict sensitivity for any Conflict Pool programming.

2.72 Demobilisation programmes in the context of ongoing military operations carry inherent risks for the civilian population. Alongside other organisations, MONUSCO has been encouraging traditional and religious leaders to facilitate the surrender of rebel fighters from the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). It also conducts periodic publicity campaigns targeting the FDLR, encouraging them to surrender. These are timed to coincide with joint military operations by government forces and MONUSCO. According to MONUSCO, this tactic maximises the numbers of fighters that surrender. It also means, however, that there is a risk that rebel groups view the demobilisation programme as part of military operations, which could lead to retaliation. According to the UN, on at least one occasion, in 2008, the LRA carried out retaliatory attacks on the civilian population, including abducting civilians to replenish its ranks. It was not alleged that any such retaliation has occurred in respect of Conflict Pool-funded activities. Nonetheless, where UK funds are used for high-risk interventions in conflict situations, we would expect to see careful analysis of the risks and benefits for the civilian population, together with active UK engagement with the implementing partners to ensure that the programme is designed so as to minimise risk. We saw no evidence that this had occurred.

2.73 Another Conflict Pool programme in DRC, the garrison project, was designed to improve the living conditions of soldiers and their families, in order to reduce army abuses of the civilian population. Although the Conflict Pool contributed to this project, the bulk of its funding came from the DFID bilateral aid programme to DRC. Commencing in 2008, the project improved living facilities in eight army camps, benefiting 2,000 soldiers and 9,000 dependants. Implementation by the United Nations Development Programme, however, proved very difficult, taking 54 months instead of the planned 20 months. The project made no provision for maintenance of the facilities, which was left to the army. As a result, they quickly deteriorated. In eastern DRC, many government buildings financed with donor money, including by EUSEC, remain empty and some have been subject to pilfering and vandalism.

2.74 Overall, we did not find much prospect of meaningful impact from Conflict Pool activities in DRC. Despite its small budget, providing resources through international partners has enabled the Conflict Pool to pursue larger objectives but has also locked it into strategies that have proved largely ineffective. In an environment as difficult as DRC, conflict prevention initiatives will inevitably have a high failure rate. We would, however, expect to see more evidence of the Conflict Pool learning from experience and adjusting its approaches accordingly.

Learning

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.75 The Conflict Pool has operated for more than a decade without an overall system for results management. This weakness was acknowledged in the BSOS in July 2011 and there are plans to strengthen monitoring and evaluation as part of the current round of organisational reforms, although these plans are yet to take concrete shape.

2.76 At present, reporting on results is largely confined to the project level. Individual project partners report quarterly on their activities. This reporting process is quite burdensome on both the partners and Conflict Pool staff, without generating robust information on results. Monitoring and evaluation capacity in the project partners is also often weak. In our two case study countries, we came across only two examples of independent evaluation reports. We would expect to see more use of real-time evaluation (perhaps of clusters of similar activities) to guide portfolio development.

2.77 There is no overall assessment of results at country, regional or global levels. This means that the Conflict Pool does not report regularly on progress towards its objectives, limiting the scope for both accountability and learning. This may explain why activities in DRC have been permitted to continue from one year to the next without achieving obvious results.

2.78 In the past, the Conflict Pool produced annual reports, which presented in narrative form some of the results from across the portfolio. The annual report, however, had little analytical content and was not used to support results management. It was found to be burdensome on the Conflict Pool Secretariat to produce and was discontinued after the 2009-10 edition.19

2.79 The last independent evaluation of the Conflict Pool was in 2004. A desk review of the Africa Programme was carried out in July 2010.

2.80 The Conflict Pool has shown little capacity to generate and draw on experience and good practice, except via the personal knowledge of a handful of specialist staff. There is no process for refining the Conflict Pool’s approach to conflict prevention and comparing it with trends in international practice. While there are resources available within the Stabilisation Unit for carrying out programme reviews and evaluations, these are not drawn on regularly by country offices.

2.81 There is insufficient information in the public domain to allow external scrutiny of the Conflict Pool’s portfolio. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Conflict Issues, while very supportive of the idea of the Conflict Pool, noted that there is insufficient information available for the Group to assess the quality of the Conflict Pool’s operations. We acknowledge that there may be a legitimate need to keep some activities confidential. We are concerned, however, that more effort has not been made to share information.

2.82 Since the July 2011 BSOS, the Conflict Pool has introduced a results offer process to produce a clearer link between the activities it funds and their intended results. The next step should be the introduction of a system for measuring and reporting on results at the country and regional levels, to enable programme teams to review the effectiveness of their portfolios and SROs to hold them to account against their results offers. The need for such a system has been recognised, although it has not yet been designed.

2.83 We recommend that the new results management system be carefully adapted to the specific needs of the Conflict Pool. A poorly designed results management system might have a number of unintended consequences, such as stifling risk-taking, imposing unrealistic time frames or pushing programme teams to focus on results that are measurable rather than meaningful.

2.84 In our view, a results management system appropriate for the Conflict Pool may look quite different from DFID’s system. DFID’s approach is designed for much larger unit-size activities and focusses on capturing the results of individual programmes. The Conflict Pool portfolio, by contrast, involves groups of activities clustered around the achievement of common goals. Results monitoring, therefore, needs to be carried out at the portfolio rather than the activity level and so cannot be passed entirely to implementing partners.

2.85 This suggests the need for a significant boost in monitoring and evaluation capacity within the Conflict Pool. This includes more training for staff in-country, more expertise at the centre to support country teams and more use of external experts to carry out real-time evaluations and strategic reviews.

3 Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

3.1 At its best, the Conflict Pool is an important, flexible and responsive tool for supporting conflict prevention initiatives. It has proved adept at identifying promising delivery partners and helping them to develop suitable activities. Conflict prevention is, by its nature, a somewhat speculative investment and it needs a ‘venture capital’ approach to funding that is open to new ideas and willing to tolerate risk. The feedback we received from implementing partners on the quality of their partnerships with the Conflict Pool was uniformly positive.

3.2 Nonetheless, the Conflict Pool is struggling to demonstrate real impact. In part, this is because of a lack of clarity as to what level of impact can be expected from relatively small sums directed towards influencing some of the world’s most challenging conflict situations. While one of the strengths of the Conflict Pool is its ability to nurture worthwhile local initiatives, it also needs to target its funds so as to deliver better impact. We have set out the three levels of impact we would expect to see from Conflict Pool operations, namely:

- a range of relevant, localised impacts at the activity level, particularly where catalytic in nature;

- a plausible contribution to high-level objectives through progress in putting in place enabling conditions for peacebuilding and conflict prevention; and

- a more coherent and effective approach to conflict prevention by the UK Government.

3.3 Despite improving its processes for strategy development at the country and regional levels, the Conflict Pool still suffers from a significant strategic deficit. It has not articulated how it will integrate defence, diplomacy and development into a multidisciplinary approach to conflict prevention, its role alongside DFID’s conflict prevention work or important elements of its funding model. This strategic deficit means that the Conflict Pool is not concentrating its resources into its areas of comparative advantage, which we have identified as including:

- mobilising small-scale, flexible assistance in high-risk and politically sensitive areas;

- funding pilot or demonstration projects to attract funding from other sources;

- working across national borders to address regional conflict dynamics;

- funding projects that are not classed as ODA or which combine ODA and non-ODA in strategic ways; and

- combining defence, diplomacy and development into multidisciplinary approaches to conflict prevention.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The Building Stability Overseas Board should develop a clearer strategic framework specifically for the Conflict Pool, to clarify its comparative advantage alongside DFID (particularly in regional programming) and identify how it will integrate defence, diplomacy and development into a multidisciplinary approach to conflict prevention.

3.4 Working in a consensual way across three departments inevitably comes with high management costs. These should, in principle, be offset by the benefits of improved coherence and a three-dimensional approach to programming. The Conflict Pool made a useful early contribution to cross-governmental coherence. This, however, has now been superseded by more recent developments, such as the creation of the National Security Council and joint UK delivery plans for strategically important countries. We saw few examples of genuinely multidisciplinary activities within the portfolio. We found that tri-departmental working was focussed on basic management tasks, to the neglect of strategy setting.

3.5 There is, therefore, a need for the three departments to streamline the management structure of the Conflict Pool. One option is for a single department to lead on the management and implementation of specific Conflict Pool activities, while retaining a tri-departmental approach to strategy setting and funding allocation. Were FCO to be selected (in the light of its increasingly prominent role in Conflict Pool management and DFID’s increasing disengagement from a direct spending role), it would have to increase significantly its investment in both management capacity and technical advisory resources (see paragraph 2.42 on page 12 regarding FCO’s project management capacity).

Recommendation 2: By the next Conflict Resources Settlement (starting in 2015-16), the three departments should simplify the management structure for the implementation of Conflict Pool activities, while retaining a tri-departmental approach to strategy setting and funding allocation.

3.6 Budget volatility, arising chiefly because the Conflict Resources Settlement has to fund peacekeeping costs as a priority, has been a significant constraint on the effectiveness of the Conflict Pool. While the Conflict Pool has become better at managing the volatility, it is likely to remain a problem in the future.

Recommendation 3: At the next spending review, the three departments should work with the Treasury to reduce volatility in the Conflict Pool budget.

3.7 The Conflict Pool’s ability to identify and support worthwhile conflict prevention initiatives is its core strength, which should be retained. The downside of this ‘venture capital’ funding model, however, is that the Conflict Pool cannot always find partners able to advance its objectives at the necessary scale. This can lead to a proliferation of small activities that do not add up to a strategic contribution to its higher-level objectives. The Conflict Pool, therefore, needs to combine its responsive, grant-making funding model with the ability to deliver high-priority activities on the requisite scale. This could be done by directly procuring implementing partners for larger Conflict Pool investments. The Conflict Pool also needs to pay more attention to identifying alternative funding sources to take promising pilots to scale. The different types of programming should be clearly differentiated in Conflict Pool strategies and procedures. The Conflict Pool should give more consideration to assessing which funding model is appropriate for different objectives. It should also provide clear guidance to staff as to what level and type of financial supervision is appropriate to different funding models.

Recommendation 4: To maximise its impact, the Conflict Pool should match its funding model to its specific objectives, balancing a proactive approach to identifying partners for larger-scale activities with a flexible and responsive grant-making process for promising local initiatives and paying more attention to leveraging other resources to take pilot activities to scale.

3.8 Conflict sensitivity (that is, the use of analysis and monitoring to avoid unintended harm) is a basic principle of conflict prevention and indeed any external interventions in conflict-prone areas. We recommend that the Conflict Pool develop guidelines for conflict-sensitive programming and ensure that they are supported by appropriate monitoring arrangements. When funding international organisations, the Conflict Pool should use its influence to ensure that they are also conflict-sensitive.

Recommendation 5: The Conflict Pool should adopt guidelines on risk management and conflict sensitivity.

3.9 We welcome the commitment made in the BSOS to develop a more rigorous approach to results management. We note, however, that the new system will need to be tailored to the unique situation of the Conflict Pool, to avoid unintended consequences. It is not appropriate to push the burden of monitoring results entirely down to the activity level. The Conflict Pool also needs to be able to capture the results of groups of activities aimed at common objectives. Better use of theory of change analysis can help identify intermediate objectives (‘enabling conditions’) between project outputs and high-level goals, allowing the Conflict Pool to target its resources more strategically.

Recommendation 6: The Conflict Pool should develop a balanced monitoring and evaluation system which encompasses both strategic resource management and real-time assessment of the outcomes of specific projects.

3.10 This should include:

- capturing project outcomes through information provided by implementing partners supplemented by external, formative or real-time evaluations where warranted by the size of the project or its strategic significance;

- tracking the results of groups of activities sharing common objectives, using additional monitoring information collected by the Conflict Pool;

- tracking changes in conflict dynamics, to enable country strategies to be adapted accordingly;

- reporting on the most significant results from each country and regional programme, using a combination of qualitative and quantitative information, to strengthen accountability under the results offer process; and

- monitoring the overall health of the Conflict Pool as a mechanism, with indicators to measure the quality of its portfolio and processes.

Annex

Extracts from the Building Stability Overseas Strategy, July 2011

- ‘We need to have the right funding mechanisms and capabilities to support an agile response. The UK’s tri-departmental Conflict Pool provides cross-government resources to prevent conflict but lacks the flexibility needed to fund responses to early warning signals and other opportunities that arise in situations of instability and conflict. We will therefore create a £20 million annual Early Action Facility (EAF) within the Conflict Pool. This will amount to £60 million over the current Spending Review period. It will be a cross- government facility drawing on a mixture of Official Development Assistance (ODA) and non-ODA resources. The EAF will help us move more swiftly in response to warnings and opportunities, for example to fund quick assessments to lay the groundwork for more significant support and help to leverage work by others.’

- ‘The Government’s Conflict Pool is an important mechanism which demonstrates joined-up delivery across DFID, FCO and MOD. The Pool, which includes a mixture of ODA and non-ODA resources, can be used to fund a wide range of conflict prevention work and also plays a number of important niche roles – for example it supports regional and cross-border work and invests in improving the effectiveness of international partners.’

- ‘The SDSR [Strategic Defence and Security Review] announced that the Conflict Pool’s programme resources will rise over the Spending Review period to a total of £1.125 billion. We need to ensure that Conflict Pool resources are invested strategically, contributing to the broader UK effort in a country in an efficient and effective way. We will therefore introduce a stronger results focus in the Conflict Pool, and improve programme management. We will work to ensure that the Conflict Pool provides predictable multi-year resources for country or regional strategies, where they exist, helping to build: free, transparent and inclusive political systems; effective and accountable security and justice (including through defence engagement); and the capacity of local populations and regional and multilateral institutions to prevent and resolve the conflicts that affect them.’

- ‘The Building Stability Overseas Board, established by the SDSR, will agree an appropriately resourced implementation plan and will have particular responsibility for the reform of the Conflict Pool.’

- ‘We will open up our work to more external challenge and evaluation, using an independent view of the Government’s conflict prevention performance to challenge our thinking and drive continuous improvement. As a first step the new Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) which reports directly to the International Development Committee in Parliament has signalled that it will carry out an evaluation of ODA spent through the Conflict Pool during financial year 2011/12. This will cover work by all three Departments. Building on this, we will put in place an evaluation strategy for the Conflict Pool, covering the Spending Review period. This will help to focus our programming and improve lesson learning.’

Abbreviations

- ACPP

- Africa Conflict Prevention Pool

- BSOS

- Building Stability Overseas Strategy

- CBO

- Community-Based Organisation

- DDRRR