The UK’s work with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

Introduction

This information note comes in the context of the 2020 funding replenishment for Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (‘Gavi’). It provides background for the International Development Committee on the UK’s relationship with Gavi as its largest bilateral funder and on the development case for investing in Gavi, with a brief discussion of the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Gavi is seeking at least $7.4 billion (approximately £6 billion) from international donors for its Phase 5.0 strategy (2021-2025), to support the immunisation of 300 million children and save up to eight million lives. The UK is hosting the Global Vaccine Summit virtually on 4 June 2020, chaired by the Prime Minister, to raise the funds Gavi needs for Phase 5.0.

What is Gavi?

Launched in 2000 at the World Economic Forum, Gavi is a public-private partnership of national governments, multilateral agencies, non-governmental organisations and the private sector to vaccinate children in the world’s poorest countries (see Box 1). In a crowded global health field, Gavi plays a unique role in improving immunisation access and uptake. Its work supports 14 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals and addresses many of the most pressing global health threats identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) – including protecting the world from disease pandemics.

Box 1: Gavi’s mission and scope

- Support for routine childhood immunisation and mass vaccination campaigns

- Grants for health and immunisation system strengthening

- Logistics support, including for cold chain infrastructure

- Vaccine stockpiles for emergency response

- Market-shaping activities (eg demand forecasting, supply and procurement roadmaps, price negotiation)

- Use of innovative financing instruments.

Gavi supports low-income countries with a per capita income below $1,580, of which there were 49 in 2019, being those who most need assistance in funding routine vaccination. Once above the threshold for three years, countries transition out of Gavi support over a five-year period by increasing their financing levels for the vaccines they receive until they are paying for them in full. After transition they may retain some access to affordable vaccines for a further period. Gavi’s eligibility policy is a point of debate, as some countries will graduate with substantial populations of under-vaccinated children. Due to competing health priorities, growing vaccine hesitancy, rapid urbanisation and other middle-income country challenges, these countries may struggle to expand or even maintain vaccination financing.

Since its inception, Gavi has helped to vaccinate more than 760 million children, preventing more than 13 million deaths worldwide from illnesses such as hepatitis, pneumonia, measles, meningitis, diarrhoea, rubella, yellow fever, liver cancer and cervical cancer. It helps partner countries to pay for vaccines and organise national immunisation programmes. Because Gavi funds vaccines for almost half the world’s children, it plays a key role in shaping the global market for vaccines. In 2018, there were 17 manufacturers supplying quality-assured Gavi vaccines (of which 11 were in Africa, Asia or Latin America), compared to just five in 2001. Between 2010 and 2018, the cost of immunising a child with pentavalent, pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines fell by 55% in Gavi eligible countries. Market-shaping activities have also achieved price benefits for non-Gavi countries, although there have also been challenges and some unintended negative consequences. Some commentators have suggested that Gavi should continue to adapt its market-shaping strategy to changing market conditions, to ensure that any unintended consequences are addressed.

Box 2: Innovative financing instruments

In 2006, the UK played a pivotal role in setting up Gavi’s innovative financing mechanism, the International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm), and has committed £1.63 billion to the Facility through to 2029. IFFIm sells Vaccine Bonds on the capital markets, thereby borrowing against financial commitments from donors. This has enabled Gavi to frontload and scale up its investments, and respond rapidly to immediate, unbudgeted needs. In the period 2016 to 2020, IFFIm disbursed £488 million to Gavi, representing 7% of its resources. It was originally expected to disburse £1.1 billion, but the additional funds were not required due to Gavi’s success in raising funds from other sources and enabling cheaper prices for vaccines. While this has led some stakeholders to question the need for IFFIm, it has been identified as a potential mechanism for funding the COVID-19 response.

The UK also played a key role in the Advanced Market Commitment (AMC) for the pneumococcal vaccine – that is, a commitment by Gavi to purchase the new vaccine at a set price for a given number of years, which incentivises producers to invest in its development and manufacture. The AMC was launched in 2007 with five countries (UK, Canada, Italy, Norway and Russia) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation jointly committing $1.5 billion to accelerate the availability of a vaccine that is expected to save the lives of seven million children by 2030. A similar mechanism has been proposed to support Gavi’s COVID-19 response.

The recommended childhood immunisation package has broadened in recent years through the addition of new vaccines. This has made comprehensive immunisation more expensive – an issue that particularly affects middle-income countries transitioning out of Gavi support. In some cases, pressure to deliver new vaccines has drawn resources away from routine immunisation. Non-Gavi countries have not always enjoyed the benefits of market savings. Many countries also lack effective national systems, which has made the balancing of health priorities and cost effectiveness particularly difficult.

The UK and Gavi

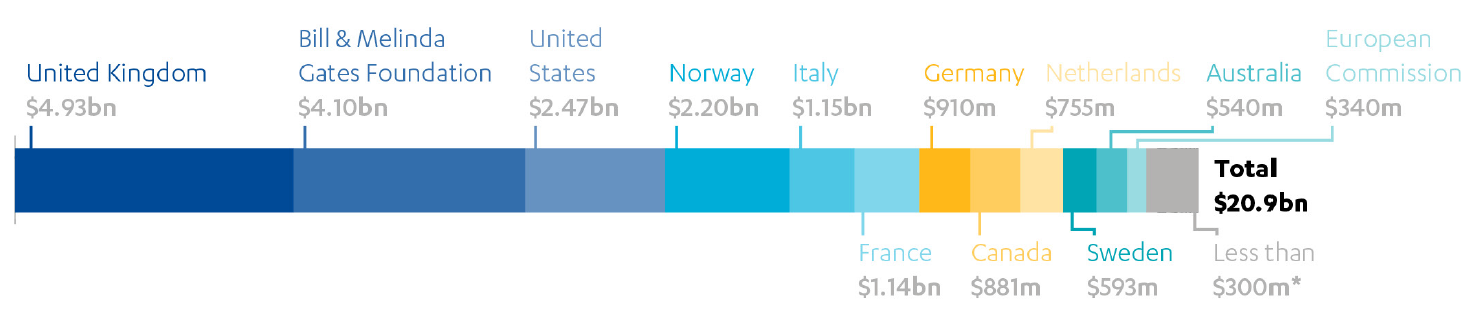

The UK has committed £4 billion (approximately $4.93 billion) to Gavi since its inception, making it the biggest funder at around a quarter of total contributions (see Figure 1). As well as making direct grants to Gavi, the UK has also contributed to its two innovative financing mechanisms (see Box 2, above) – the International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm) and the Advanced Market Commitment (AMC). For the forthcoming replenishment, covering 2021 to 2025, the UK has announced that it will contribute £1.65 billion, which includes past pledges and commitments that extend into Phase 5.0. The UK’s major financial contribution gives it an influential role on the Gavi board, alongside multilateral and bilateral donors, developing countries, industry representatives, research institutions and civil society. It also sits on the Governance Committee, the Market Sensitive Decisions Committee, the Policy and Programme Committee, the Partners Engagement Framework (PEF) Management Team and the Audit and Finance Committee. This has enabled the UK to promote its strategic priorities, such as increasing support for fragile states and strengthening stockpiles in preparation for outbreaks of epidemic diseases.

In a 2018 review, ICAI found that DFID had successfully encouraged Gavi to strengthen its epidemic preparedness and its mechanisms for country-level accountability. Following DFID encouragement, Gavi strengthened its investments in fragile and conflict-affected states, with DFID’s latest annual review praising its work in Syria and the Central African Republic. DFID has also placed strong emphasis on equity, encouraging Gavi to support national immunisation systems that can reach the poorest and most marginalised children and avoid leaving behind populations of zero-dose children, who could be a potential source of future outbreaks. This is an area where Gavi has received some criticism over the years. Coverage rates of Gavi-funded vaccines remain variable and below its Phase 4.0 targets, particularly in countries with the largest birth cohorts, including some of those transitioning out of Gavi support. Gavi has responded by increasing its investments in strengthening national health systems and making a commitment to putting ‘the last mile first’ in its 2021-2025 strategy, including by investing at least £900 million in health system strengthening grants to extend immunisation services to hard-to-reach communities.

“Between 2010 and 2018, the cost of immunising a child with pentavalent, pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines fell by 55%.”

Figure 1: Funding contributions over Gavi’s 20-year life

*The list of countries and foundations contributing less than $300m is available in Annex 9 of the source listed below.

Source: Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance: Prevent, Protect, Prosper. 2021-2025 Investment opportunity, p 45. Figures as of June 2019.

DFID’s 2016 Multilateral Development Review assessed Gavi to be a high-performing multilateral organisation, scoring as ‘very good’ on both strategic fit with UK priorities and organisational capacity. It rated particularly well on value for money and transparency, but poorly on risk and assurance. DFID conducted an audit of Gavi in 2015-16 and helped it to upgrade its risk management processes. A member of DFID’s Internal Audit Department now sits on Gavi’s Audit and Finance Committee. In DFID annual reviews, Gavi has received A or A+ scores since 2015, despite missing key equity milestones, indicating that it is generally performing at or above expectations. DFID reviews single out Gavi’s co-financing model as particularly effective, with 98% of partner countries meeting their financial commitments to avoid incurring sanctions.

Is Gavi a good investment?

DFID’s Single Departmental Plan for 2015 to 2020 set the goal of immunising 76 million children against killer diseases by 2020. DFID’s results against this target come entirely from Gavi (it claims a share of Gavi’s total results based on the UK’s share of total funding – although there are some inconsistencies in the published data on the UK’s funding share). DFID’s latest Annual Report states that DFID supported the immunisation of 56.4 million children by December 2017, saving 990,000 lives. While data for 2018 and 2019 are not yet available, DFID reports that it is on track to achieve its 2020 goal.

While DFID is yet to develop a business case for its new pledge to Gavi, it has been able to articulate a strong argument for investment in the concept note. Immunisation has long been considered an international development “best buy”. The Decade of Vaccine Economics (DOVE) group recently calculated the return on investment for childhood immunisation over the period 2021-2030, accounting for the benefits of averting ill health and its wider social and economic costs. This suggested a return of $54 for every $1 spent, leading Gavi to project $80-100 billion in economic benefits from its Phase 5.0 plan. However, the COVID-19 pandemic will inevitably impact on this figure.

Gavi’s multilateral structure acts as a multiplier of UK investment in a number of ways and may be one reason DFID argues that investment represents good value for money. It helps the UK to encourage contributions from other donors, scaling up the investment for greater impact. It also gives the UK, through its role in Gavi’s governing bodies, a degree of influence over the entire funding pot, helping to raise the quality of expenditure and direct it in ways that support the UK’s development priorities. This influence has been enhanced through the use of innovative financing. The UK’s early engagement with IFFIm encouraged other donors, such as Norway, to support the concept of vaccine bonds in Gavi’s initial phases. This enabled Gavi to borrow against future donor commitments in its early phases.

Box 3: Gavi Phase 5.0 objectives, 2021-2025

- Empower countries to take on vaccine financing and transition a further ten countries into self-financing.

- Catalyse country contributions of $3.6 billion in domestic co-financing and self-funded vaccine programmes.

- Continue to engage the 18 countries that have already transitioned with activities to sustain progress.

- Contribute to a further $80-100 billion in economic benefits.

- Enhance the competitiveness and supply security of at least five Gavi-supported vaccine markets.

- Deliver over 3.2 billion doses of lifesaving vaccines to 55 eligible countries.

- Facilitate 1.4 billion touchpoints between families and health services through vaccination.

- Insure the world against polio reemergence through implementing routine inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) programmes across Gavi countries, in collaboration with the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI).

- Fund vaccine stockpiles for emergency use to stop dangerous outbreaks.

Source: Prevent, Protect, Prosper: 2021–2025 Investment opportunity, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

Central to Gavi’s value-for-money proposition is its ability to shape the vaccine market. Historically, this market has not worked for the benefit of the developing world. The pharmaceutical industry has had little incentive to produce the commodities needed by developing countries at prices they can afford. By concentrating their buying power and ensuring predictable demand over a long period, Gavi has changed the market dynamics. International producers now have more incentive to produce a reliable supply of vaccines and to innovate around the development of new products. The number of suppliers producing quality assured vaccines for developing countries has increased significantly. Long-term supply agreements under the AMC and Gavi’s ability to negotiate prices with pharmaceutical companies has also led to significantly lower prices. For example, the average price of the pneumococcal vaccine dropped by $0.40 (from $3.30 to $2.90 per dose) between 2017 and 2019, which is expected to save $96.6 million over the next decade. In this way, the combined purchasing power of Gavi’s donors has dramatically increased the impact of the investment. However, the vaccine market continues to evolve rapidly, with new competing buyers, such as China, changing its dynamics. Gavi will need to adapt its approach to sustain this price advantage.

DFID also argues that its investment in Gavi supports the immediate UK national interest. Building developing country capacity to deliver immunisation programmes helps in the global fight against epidemic disease, which is both a good development investment and a means of reducing public health threats to the UK. As discussed in the next section, an effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic has to be global in reach, including developing countries, which would otherwise act as a source of future outbreaks. Furthermore, DFID sees the Global Vaccine Summit as an opportunity to showcase the UK’s leading role on health-related research and innovation, including the work of UK-based vaccine developers and pharmaceutical companies.

“In 2018, there were 17 manufacturers supplying quality-assured and appropriate Gavi vaccines, compared to just five in 2001.”

Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic

The Global Vaccine Summit takes place in the context of international debate about the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Gavi’s work. A number of Gavi donors have requested that a COVID-19 response plan be part of the replenishment discussions, given the urgency of strengthening national health and immunisation systems in developing countries and Gavi’s potential role in deploying a future COVID-19 vaccine. The UK’s pledge of £1.65 billion (equivalent to £330 million per year) is intended for core Gavi activities, and stands alongside the £744 million in UK aid committed to the COVID-19 response through other channels so far in 2020. This includes a £250 million contribution to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) to support the development of a COVID-19 vaccine.

The COVID-19 pandemic has already had a major impact on Gavi’s core mission. In accordance with WHO guidance, mass vaccination campaigns have been suspended. Routine childhood immunisation has also been heavily disrupted in most countries, due in part to vaccine supply constraints. This will make it more difficult for countries to respond to outbreaks of preventable disease, such as measles in DR Congo. Gavi has voiced its concern that the countries with the most zero-dose children – such as India, Pakistan and Indonesia – are also among those most severely affected by COVID-19, and that rumours related to COVID-19 are fuelling vaccine hesitancy. Furthermore, countries that have transitioned from Gavi support may fall back under the eligibility threshold again as a result of the economic impacts of the pandemic.

There is a strong public health case for continuing Gavi’s routine childhood immunisation work despite the pandemic. Modelling by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), funded by Gavi and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, found that for every death due to COVID-19 infections acquired through immunisation visits in Africa, as many as 140 child deaths could be prevented. Nevertheless, immunisation programmes are likely to be extensively disrupted throughout 2020 and potentially into 2021.

Gavi has updated its objectives for this replenishment to reflect its potential role in the global COVID-19 response. Gavi and CEPI jointly lead the vaccine component of the new Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator, a global collaboration launched in April 2020. CEPI is focused on vaccine research and development and Gavi on vaccine deployment to developing countries. Ensuring that most of the world’s population have access to a vaccine is central to the global goal of controlling the pandemic. The Coronavirus Global Response Summit on 4 May 2020 led to donor pledges of $8 billion (approximately £6.5 billion) some of which will support the ACT Accelerator. The cost of deployment is likely to exceed $20 billion (approximately £16.5 billion), far surpassing the amount pledged; the source of the remaining funding is not yet known.

“The health benefits of sustaining routine childhood immunisation in Africa far outweigh the excess risk of COVID-19 deaths associated with vaccination clinic visits.”

The implications of COVID-19 funding needs on the forthcoming Gavi replenishment remain unclear. Gavi’s appeal for at least $7.4 billion (approximately £6 billion) for its Phase 5.0 plan predates the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 response will inevitably compete for resources with Gavi’s planned activities – a tension that Gavi has acknowledged. At Gavi’s March 2020 board meeting, four COVID-19 actions were agreed: (i) engage in partnership to make an affordable vaccine accessible and available to Gavi countries, (ii) until a vaccine becomes available, take a flexible approach to manage the impact on country health systems, (iii) plan for deployment of the COVID-19 vaccine, and (iv) work closely with UNICEF Supply Division on vaccine procurement and delivery. However, it was agreed that this programme will need to be managed carefully to avoid ‘crowding out’ Gavi’s core mission.

Both IFFIm and a new AMC have the potential to be important elements in Gavi’s COVID-19 response. IFFIm issued a bond against a commitment by the Norwegian government to support CEPI with vaccine development pre-COVID-19, while an AMC could facilitate increased vaccine production and affordable pricing for Gavi countries.

Suggested lines of enquiry

We conclude by suggesting a number of lines of enquiry that the International Development Committee may wish to pursue.

- Is Gavi achieving the right balance between immunisation campaigns and strengthening national health systems?

- How will DFID ensure that global momentum is sustained on child immunisation? Will the UK’s contribution to Gavi’s routine vaccination programming be ring-fenced for that purpose?

- What should Gavi do differently to prevent leaving behind pockets of zero-dose children?

- Where does Gavi need to improve as an organisation? Does DFID propose to include

performance incentives in its funding agreement? - How should Gavi manage the trade-off between comprehensive delivery of a basic package of vaccines for all, and delivery of more expensive vaccines to selected populations?

- How can DFID support Gavi to ensure that developing countries gain timely and equitable access to a future COVID-19 vaccine, in the face of global competition?

- In light of the economic impact of the pandemic, should Gavi reconsider its eligibility and graduation criteria?

- The government has drawn attention to the benefits of investing in Gavi for the UK and its industry, as well as the benefits to people in developing countries, and clearly there are win wins. But are there any potential trade-offs if donor country immediate interests are placed more to the fore?

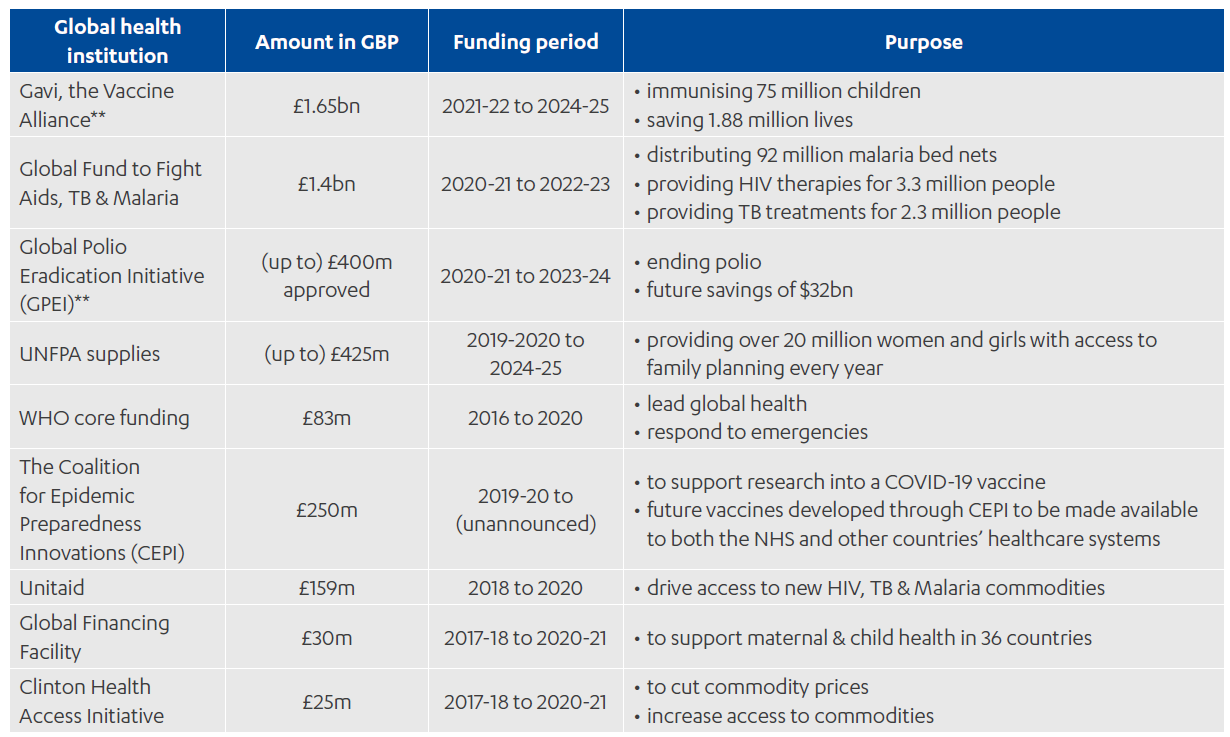

Annex 1: UK investment in global health institutions