The UK’s approach to funding the UN humanitarian system

ICAI score

DFID has a strong strategy for using its funding and influence to strengthen UN humanitarian agencies and global humanitarian practice, but its record to date in promoting practical reforms is mixed.

DFID seeks to use its influence as a major funder of UN humanitarian agencies to build their capacities and improve global humanitarian practice. It has pursued a clear set of reform objectives, including better coordination, more flexible funding and greater use of cash transfers. It has coordinated well with other donors and has been a thought leader in a number of areas. It has innovated in its own funding practices in order to build UN agency capacity and tackle systemic problems such as overlapping mandates and unclear lines of accountability.

DFID’s flexible, multiannual funding has helped to build the capacity of UN agencies and equip them to respond more effectively to emergencies. DFID is widely credited with introducing a stronger focus on value for money into humanitarian practice. Its reporting and due diligence requirements have given it greater ability to oversee how UK aid is spent, but are increasingly demanding, taking resources away from programme implementation.

DFID has been highly influential in promoting the use of cash transfers. Other reform objectives have not been pursued as intensely and have achieved mixed results. While DFID has begun to align its influencing efforts at international and country levels, its humanitarian cadre lacks the resources to support the ambitious ‘Grand Bargain’ reform agenda. The use of payment by results to encourage improvements in the UN’s collective performance is experimental, but weaknesses in design and delivery, and DFID’s initial lack of engagement with other donors, suggest that this approach will need refinement to achieve DFID’s objectives.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Relevance: To what extent have DFID’s choices of funding channels and mechanisms for UN humanitarian agencies been relevant to its strategy and objectives for strengthening the humanitarian system? |  |

| Question 2 Efficiency: Has DFID’s funding of UN humanitarian agencies led to improvements in their individual management practices, capabilities and performance? |  |

| Question 3 Effectiveness: Is DFID’s funding and influencing of UN humanitarian agencies likely to influence the overall performance of the humanitarian system? |  |

Executive summary

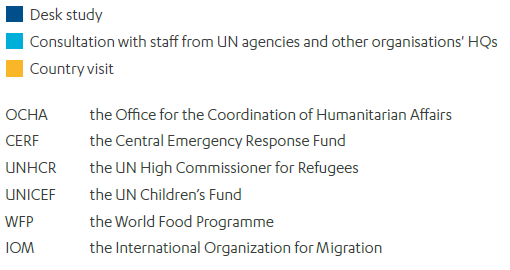

There has been a sharp rise in global humanitarian need over this decade, driven by large-scale conflicts in Syria, Yemen and South Sudan and the mass expulsion of Rohingya people from Burma. The UK is a major funder of humanitarian responses, providing £1.56 billion in 2017-18. Around half of this goes through UN humanitarian agencies, which have a unique mandate and capacity to provide humanitarian assistance at scale in the world’s most troubled places.

While the UN humanitarian system unquestionably saves a great many lives each year, it is large and unwieldy, with overlapping mandates and inbuilt inefficiencies. The traditional pattern of humanitarian funding places UN agencies in competition with each other, sometimes at the expense of the efficiency of the humanitarian system as a whole. There has been a long history of efforts to reform the system – including most recently a ‘Grand Bargain’ of reforms to humanitarian practice agreed at the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016.

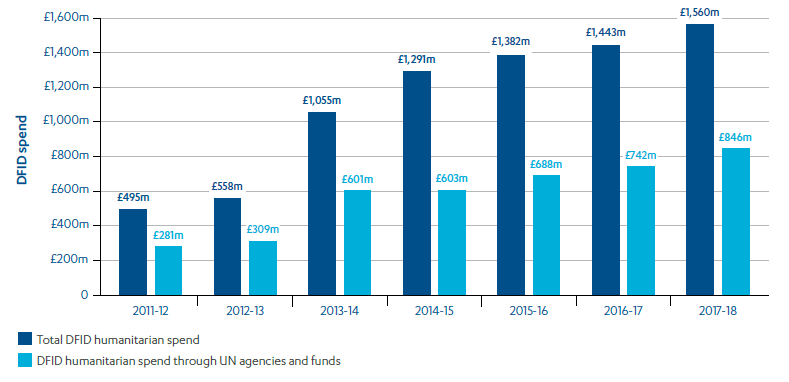

In this review, we explore how well DFID has used its position as a major donor to improve the value for money and effectiveness of humanitarian aid spent through UN agencies. Our primary focus is on core funding to UN humanitarian agencies – that is, unconditional funds paid into their central budgets, which can be used to support core functions or allocated flexibly to particular emergencies. Core funding accounts for just under a quarter of DFID’s humanitarian funding through the UN. The rest is allocated in response to specific crises. Over our review period, from 2011 to 2018, DFID has experimented with different ways of providing core funding – including most recently by introducing a ‘payment by results’ element, where part of its funding is conditional on satisfactory progress against Grand Bargain commitments.

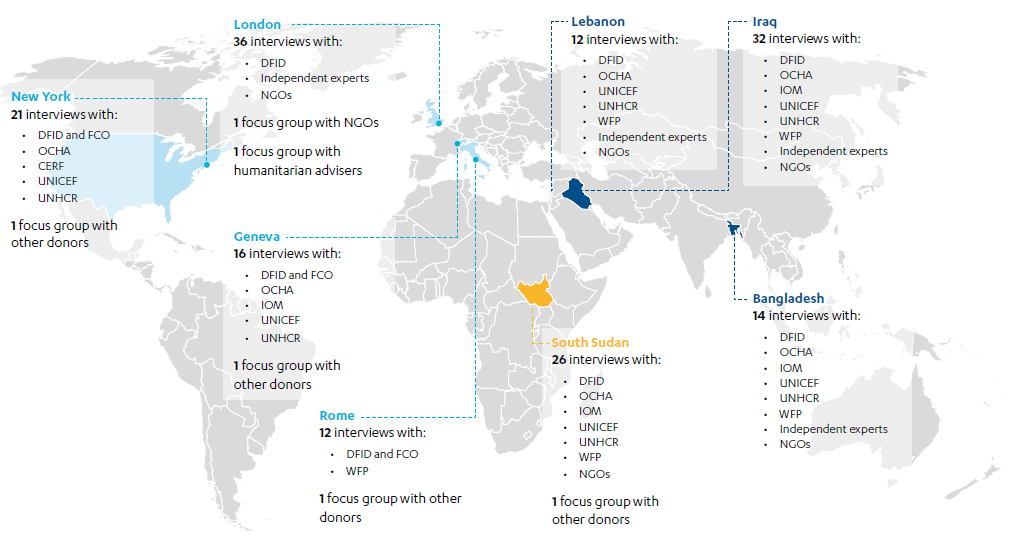

We look at whether DFID has a clear set of reform objectives and a credible strategy for using its core funding to advance them. We assess how effective it has been in strengthening the performance of individual UN humanitarian agencies and in encouraging improvements in global humanitarian practice. Our methodology included reviews of DFID’s work with six agencies, four country case studies (Bangladesh, Iraq, Lebanon and South Sudan, the last of which we visited) and thematic case studies on the use of cash transfers and accountability to affected populations.

Does DFID have an appropriate strategy and objectives for strengthening the UN humanitarian system?

Over the review period, DFID has pursued a clear and well-justified set of reform objectives for the UN humanitarian agencies. Its priorities have included:

- strengthening the UN’s leadership and coordination of humanitarian response

- promoting collaborative approaches to assessing humanitarian needs in crisis situations

- promoting pooled funding mechanisms, both centrally and in particular countries

- promoting more investment in building resilience to disasters

- increasing the use of cash transfers as a form of humanitarian assistance

- increasing transparency and accountability in humanitarian aid delivery

- putting national and local actors at the centre of humanitarian response (known as localisation).

These objectives have both reflected and influenced international agreements on humanitarian reform. In a number of areas, such as the use of cash transfers, DFID is recognised as a thought leader on improving global humanitarian practice.

DFID has used its core funding strategically to build up the coordination and leadership roles of the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and to encourage more donors to support the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), which allocates funding to sudden or neglected emergencies. It is active on UN agency boards and committees, and generally coordinates well with other donors.

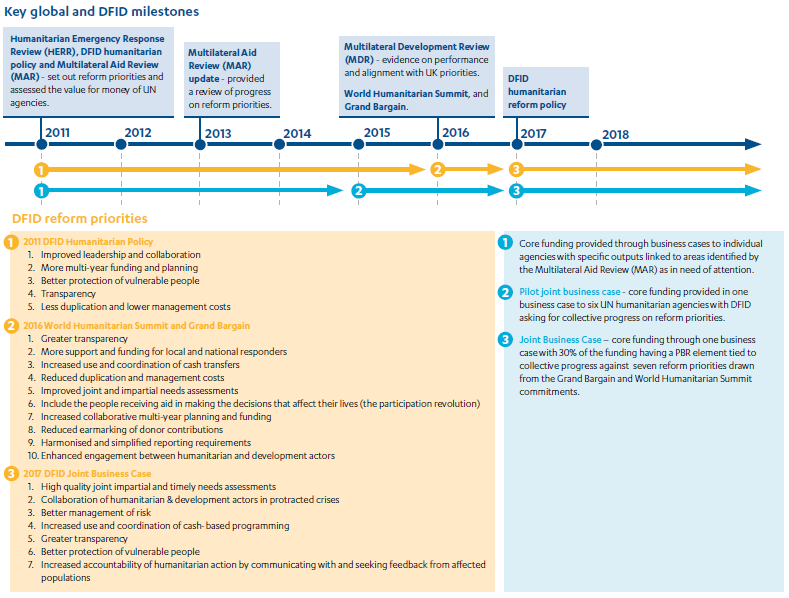

Over the review period, DFID has introduced a number of innovations in its funding practices to encourage better performance by UN humanitarian agencies. The Multilateral Aid Review process introduced in 2011 included assessments of each agency’s organisational capacity. DFID used its core funding agreements to encourage agencies to address shortcomings in their management practices, particularly around results and value for money. From 2015, DFID moved to a joint business case for core funding to the UN humanitarian agencies, to encourage agencies to work collaboratively on improving the performance of the UN humanitarian system as a whole. In 2017, it introduced a payment by results mechanism, whereby 30% of its core funding was made conditional on joint progress across the UN system towards reform commitments made under the Grand Bargain. Overall, we find that DFID has used its core funding strategically to support its reform objectives.

There are, however, some gaps in DFID’s reform priorities. It has not focused on the role played by the UN in subcontracting non-government organisations (NGOs), which deliver a substantial share of humanitarian assistance, and lacks visibility of the overheads that UN agencies levy for the subcontracting function. It could also have done more to address issues of gender equality and disability.

Overall, DFID’s clear reform objectives and its willingness to innovate in its core funding approach merit a green-amber score for relevance.

Has DFID’s core funding led to improvements in the capacities and performance of individual UN humanitarian agencies?

DFID has been a consistent provider of multiannual and core funding to UN humanitarian agencies. In contrast with short-term funds earmarked for specific purposes, core funding enables agencies to plan further in advance, invest in organisational capacity and respond flexibly to emergencies. For example, core funding has enabled the World Food Programme (WFP) to build up its capacity to provide cash transfers, while in countries such as South Sudan, the shift to multiannual funding has allowed humanitarian agencies to invest more in preparing for disasters, saving more lives at a lower cost.

DFID has used its core funding to encourage managerial reforms in UN humanitarian agencies, and we saw evidence of improvements in areas such as monitoring results and risk management. DFID’s strong focus on value for money has also encouraged the agencies to monitor unit costs and identify ways of improving efficiency. While these changes have been positive, the pace has been relatively slow. DFID has recognised the need to support its core funding with stronger engagement and in 2017 appointed additional full-time counterparts to manage the relationship with each UN agency.

DFID’s approach to value for money remains controversial within the UN. Many of the UN officials we interviewed believed that DFID was focused on driving down costs, rather than innovating to improve results. There was a common view that DFID should focus more on the quality of results, rather than on management issues, including by gathering more feedback from the people receiving the aid.

DFID is an increasingly demanding donor. It has introduced new reporting and due diligence requirements that give it greater oversight of how UN agencies manage UK aid funds. The requirements are time-consuming for both UN and DFID staff, potentially drawing resources away from programme implementation. UN officials also suggested that DFID was failing to live up to its Grand Bargain commitment to streamline reporting requirements. There was some evidence from our case studies that DFID does not always prioritise participation in Grand Bargain initiatives due to other demands on staff time, such as programme management. It did not participate in a pilot initiative on harmonised reporting which was launched during a period when operational response to the humanitarian crisis in Mosul was prioritised. While neither DFID nor the UN agencies have attempted to calculate the transaction costs associated with UK aid, there is a risk that the increasing demands are undermining some of the inherent value of core funding.

Overall, we award DFID a green-amber score for its efforts to improve the efficiency of UN humanitarian operations, in recognition of its pivotal role in championing value for money. However, we stress the importance of keeping reporting requirements proportional.

Is DFID’s support to UN humanitarian agencies likely to improve the performance of the UN humanitarian system?

Throughout the review period, DFID has had a strong focus on encouraging the use of cash transfers as a form of humanitarian support, instead of distributing food and household items. In the right conditions, cash transfers can stimulate local markets while affording more dignity to the recipients. DFID has approached this matter in a structured way, building evidence to support its case, engaging in high-level advocacy and funding initiatives at country level. As a result, DFID has played a key role in the growing use of cash in humanitarian response, which doubled in volume between 2014 and 2016 to $2.8 billion.

Other reform objectives – such as conducting joint needs assessments, accountability to affected populations and ‘localising’ humanitarian response – have not received the same level of attention, with consequently patchy results. While we saw a few examples of useful initiatives in our country case studies, DFID has not specified the practical changes it wants to see or equipped its humanitarian cadre to take these issues forward. We saw positive evidence that DFID is beginning to pursue its reform objectives consistently across its core funding and in-country support. However, country offices lack both the staff capacity and the flexible funding needed to support local initiatives to improve humanitarian practice.

In its work with UN humanitarian agencies, DFID focuses on their operational capacity to deliver aid, rather than their normative or standard-setting roles. A key part of the UN’s mandate is to provide leadership and coordination, negotiate access with national governments and lead on the articulation of humanitarian policy and principles. We found no evidence in our case study countries that DFID’s core funding was helping to strengthen the UN’s capacity in these areas.

Until the scandal around the sexual exploitation and abuse of aid recipients in Haiti came to light in early 2018, DFID had limited engagement with this issue, even though instances had been made public as far back as 2002. It has now created a safeguarding unit to review its own procedures and lead on reform across the aid sector. It has engaged with UN agencies at a senior level to encourage them to take action. At a safeguarding summit in London in October 2018, participants (including UN agencies) agreed to a range of actions, including more support for victims and whistleblowers. In our case study countries, DFID had been vocal in encouraging UN agencies to ensure that their implementing partners had appropriate safeguarding policies in place. However, among the UN staff we interviewed, there were concerns that this top-down, rules-based approach would not be enough to change practices in emergency contexts, where the power imbalance between humanitarian aid providers and recipients is so acute. We find that there is still considerable work to be done to identify practical solutions to this deep-seated problem.

The payment by results mechanism first introduced in the 2017 business case is experimental and it is too early to judge its effectiveness. However, we find that the design of the instrument needs further work if it is to succeed in creating positive incentives for reform. The rationale for including CERF in the payment by results scheme is weak, given that it is not an operational agency and has little influence on the conduct of other agencies. Given its dependence on DFID’s core funding, withholding payments to CERF would work against DFID’s objective of strengthening the agency. There are risks that the uncertainty created by payment by results prevents UN agencies from using the funds flexibly, undermining the inherent benefits of core funding. UN agencies are also concerned that, in its choice of performance conditions, DFID is ‘cherry picking’ objectives from the Grand Bargain, rather than treating it as a package with reciprocal obligations for donors.

DFID introduced payment by results without bringing other donors on board, even though the theory of change in its business case identified a common donor approach as a condition of success. While there were practical reasons for this unilateral approach, DFID now has to overcome a significant level of scepticism from other donors. Finally, DFID has been slow to put in place a method of independently verifying progress by the UN agencies on the Grand Bargain commitments, with the result that baselines have not yet been established.

These shortcomings in the payment by results mechanisms are not necessarily intrinsic to the approach, and could perhaps be resolved through refinements to the instrument. For the time being, however, DFID’s mixed record in advancing its humanitarian reform objectives and the weaknesses in its payment by results approach merit an amber-red score.

Recommendations

We offer the following recommendations to help DFID improve the impact of its future work on reforming the UN humanitarian system:

Recommendation 1

In the next annual review of its joint business case for core funding for UN humanitarian agencies, DFID should assess the practical implications of payment by results for agency budgets, planning and operations (particularly for CERF) and whether the resulting incentives are in fact accelerating implementation of the Grand Bargain.

Recommendation 2

DFID should step up its engagement with the international working groups that are translating the Grand Bargain principles into practical measures for improving humanitarian action, and develop guidance for country offices on how to prioritise and pursue these measures at country level.

Recommendation 3

DFID should develop a plan for simplifying its reporting requirements for UN humanitarian agencies, in accordance with its Grand Bargain commitment. This should take account of the trade-offs between increased oversight and transaction costs, with a focus on proportionate solutions.

Recommendation 4

DFID’s engagement with UN humanitarian agencies on effectiveness and value for money should address how they subcontract non-government organisations (NGOs) and the management overheads involved in doing so, as well as promoting compliance with safeguarding requirements through their delivery chains.

Recommendation 5

DFID should review how it supports the normative functions of UN humanitarian agencies, particularly at country level, and ensure that staff resources and budgets are available to support UN-led initiatives to improve the quality of humanitarian response.

Introduction

In 2018, more than 135 million people affected by conflict and disasters across the world were in need of humanitarian assistance and protection. Humanitarian action saves lives and alleviates suffering for the world’s most vulnerable people. In 2017, it helped to stave off potential famines in South Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria and Yemen, supported Rohingya refugees fleeing violence and persecution in Burma and continued to support millions of people in protracted crises from Syria to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In response to deteriorating global humanitarian conditions, the UK’s humanitarian aid has grown more than 200% since 2011, reaching £1.56 billion in 2017-18. Around half of this is spent via UN humanitarian agencies and funds. This reflects the centrality of the UN to the international humanitarian system, due to its unique mandate and ability to operate at scale in the world’s most challenging contexts.

Yet while it saves many lives each year, the UN humanitarian system is large and unwieldy, with overlapping functions and many inbuilt inefficiencies. There has been a long history of efforts to reform the system and streamline its operations – most recently at the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016, where a number of donors and humanitarian agencies, including the UN, signed up to a ‘Grand Bargain’ of reforms designed to improve humanitarian practice. However, reform of the UN is a complex process and progress has proved difficult to achieve.

“The humanitarian system is neither broke nor broken. […] We reach tens of millions of vulnerable people each year. We unquestionably save millions of lives. […] Nevertheless, there is ample scope to improve the global humanitarian response system”.

Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Sir Mark Lowcock, Lecture, March 2018, pp. 1-3.

In light of the importance of the UN to the UK’s global humanitarian effort, we have undertaken a review of how well the UK uses its position as a major donor to improve the effectiveness and value for money of UN humanitarian aid. Our focus is on core funding: that is, unconditional funds paid to the central budgets of UN agencies, which can be allocated flexibly for central functions or to particular emergencies. Core funding represents around a quarter of UK humanitarian funding through the UN. The rest is allocated in response to specific crises. During our review period, from 2011 to 2018, DFID has experimented with different ways of providing core funding – including by introducing in 2017 a ‘payment by results’ component. We also explore how well core funding works alongside DFID funding to UN agencies in particular crises, and whether in-country funding practices are consistent with and supportive of DFID’s objectives and approach at headquarters level.

Our review questions (see Table 1) explore whether there is a clear strategy for achieving reform, and whether DFID’s efforts have led to improvements in efficiency at the agency level and to the overall effectiveness of the international humanitarian system. We chose to conduct a performance review (see Box 1), given the volume of funding involved and the long history of UN humanitarian reform efforts.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: To what extent have DFID’s choices of funding channels and mechanisms for UN humanitarian agencies been relevant to its strategy and objectives for strengthening the humanitarian system? | • Does DFID have a clear, coherent and evidence-based strategy and objectives for strengthening the UN humanitarian system through its funding? • How consistent has DFID’s funding of UN humanitarian agencies been with its influencing strategy and policy objectives? |

| 2. Efficiency: Has DFID’s funding of UN humanitarian agencies led to improvements in their individual management, practices, capabilities and performance? | • How well does DFID assess the performance of UN humanitarian agencies and improvements in their capacity over time? • Has DFID’s core funding improved the value for money performance of UN humanitarian agencies? |

| 3. Effectiveness: Is DFID’s funding of and influence on UN humanitarian agencies likely to strengthen the overall performance of the international humanitarian system? | • How effectively does DFID combine funding instruments at international and country levels, including core and non-core funding, to achieve positive change? • How well has DFID linked its core funding to UN humanitarian agencies with its wider approach to promoting reform of the international humanitarian system? • Is DFID’s core funding of UN humanitarian agencies creating incentives for positive change in the international humanitarian system? |

Box 1: What is an ICAI performance review?

ICAI performance reviews examine how efficiently and effectively UK aid is being spent on an area, and whether it is likely to make a difference to its intended recipients. They also cover the business processes through which aid is managed to identify opportunities to increase effectiveness and value for money.

Other types of ICAI reviews include: impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for intended recipients, learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming, and rapid reviews, which are short real-time reviews of emerging issues or areas of UK spending that are of particular interest to the UK parliament and public.

Methodology

The methodology for this review had three main components:

- A strategic review: We examined the evolution of DFID’s strategy to fund and influence UN humanitarian agencies between 2011 and 2018. In order to make an assessment, we carried out a literature review that synthesised findings from system-wide and individual agency evaluations, and conducted a financial analysis of DFID’s funding by agency, country and sector.

- UN organisation engagement reviews: We reviewed DFID’s engagement with the following agencies:

- the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), which is a central coordinating body for UN humanitarian agencies

- the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), managed by OCHA, which collects contributions from donors for allocating to sudden-onset or under-funded emergencies

- the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

- the World Food Programme (WFP)

- the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

We conducted interviews with DFID staff in London and with UN agency staff and UK missions in New York, Geneva and Rome in order to investigate whether the UK had helped to bring about positive change in agencies’ management systems and response capacity. A particular focus was on how well DFID has coordinated its influencing activities with other donors. We therefore conducted focus groups with other donor governments in Geneva, Rome and South Sudan.

- Country and thematic case studies: We conducted one country visit (to South Sudan), three desk-based country studies (Bangladesh, Iraq and Lebanon) and two thematic case studies (the use of cash transfers as a form of emergency relief and the accountability of humanitarian agencies to affected populations). The case studies involved 169 interviews with UN staff, independent experts and non-government organisations (NGOs). Through the country case studies, we examined whether DFID’s humanitarian funding practices at the national level were consistent with the objectives of its core funding.

These three components enabled us to assess from several perspectives how well DFID’s various UN reform objectives, as they have evolved over time, have been reflected and advanced through its funding arrangements. We explored changes in capacity and performance of both individual agencies and the UN humanitarian system as a whole, at the global level and in the context of specific emergencies. Where possible, we looked for evidence of DFID’s particular influence in contributing to change and how well it had worked and coordinated with others in pushing for reform.

Our methodology and report were independently peer reviewed. A full description of our methodology is detailed in our approach paper.

Figure 1: Overview of interviews and focus group discussions by country

Box 2: Limitations to our methodology

Attribution: Given the long causal chains between management reforms at the UN agency level and changes to in-country performance and the fact that multiple donors are involved in promoting UN reform, attributing changes in performance to DFID’s influence and funding is difficult. Observing incremental changes in the collective performance of multiple organisations is also challenging. To evaluate the UK contribution, we assessed whether there was evidence of changes in UN humanitarian agency systems, capacities and performance in relation to DFID’s stated objectives, and whether DFID had successfully coordinated with other donors to bring about these changes.

Sampling changes: We had to adapt our sampling over the course of the review in response to events during the research phase. A planned desk study of Yemen was replaced with one of Lebanon because the DFID team and UN partners in Yemen were responding to the Hodeidah crisis (a major offensive on a key port for aid supplies). The field visit to Iraq was replaced with an in-depth desk study because the team was unable to obtain visas. We do not believe that this significantly impacted on the robustness of our methodology.

Background

Humanitarian action and the UN system

Over the review period, humanitarian need has risen sharply, as a result of large-scale conflict in Syria and Yemen, the expulsions of Rohingya from Burma, long-running crises in Somalia, Eritrea and the Central African Republic and the threat of famine across Africa, from Somalia to Nigeria. Global humanitarian assistance has increased by 46%, from $14.9 billion in 2011 to $21.7 billion (£16.6 billion) in 2017. An ever-larger proportion of global official development assistance (ODA) is going towards humanitarian assistance, rising from 9% of the total in 2007 to 13% in 2016.

Humanitarian assistance includes life-saving support – food, shelter and water – for those left in severe need by conflict or disaster. It is increasingly also expected to include wider support – education, health services, protection from harm and assistance with restoring livelihoods.

Humanitarian assistance reaches people in need through complex delivery chains. UN agencies received about 50% of global humanitarian funding. They may deliver aid directly or via international or local non-government organisations (NGOs). Bilateral donors such as the UK also provide humanitarian assistance directly to NGOs, to the Red Cross Movement and (to a lesser extent) via the private sector. NGOs involved in the last stage of delivering aid may therefore receive their funding through multiple channels.

As global humanitarian aid has risen, the share passing through UN agencies has also increased. Funds received by WFP, UNHCR, UNICEF, IOM, OCHA and CERF collectively have grown by 71%, from $6.7 billion in 2011 to $11.5 billion (£9 billion) in 2017.

Figure 2: The UN agencies covered by this review and key achievements through UK funding

| The World Food Programme (WFP) | |

|---|---|

| Total contributions to WFP in 2016: £4.51 billion | Mission: WFP is a humanitarian organisation focused on delivering food assistance in emergencies and working with communities to improve nutrition and build resilience. Key achievements: In 2015 UK support to WFP has helped contribute to: • providing direct assistance for 76.7 million people in 81 countries, of which 50 million were in emergency situations • increasing women’s decision-making over the use of food and cash in their homes in 55 countries • providing specialised support to 7.6 million malnourished children • distributing 3.2 million metric tons of food. |

| The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) | |

| Total contributions to UNHCR in 2016: £3.9 billion | Mission: The UN Refugee Agency is a global organisation dedicated to saving lives, protecting rights and building a better future for refugees, forcibly displaced communities and stateless people. Key achievements: In 2016 UK support to UNHCR has helped contribute to: • resettling 125,600 refugees worldwide • providing cash assistance to 2.5 million vulnerable refugees, people displaced within their own country, asylum seekers and stateless people in more than 60 countries • providing shelter to more than 1.2 million people • preparing for refugee emergencies and enabling UNHCR staff to respond and support 31 countries. |

| The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) | |

| Total contributions to UNICEF in 2016: £1.90 billion | Mission: UNICEF advocates for the protection of children’s rights, to help meet their basic needs and to expand their opportunities to reach their full potential. UNICEF’s humanitarian action encompasses both interventions focused on preparedness for response to save lives and protect rights as defined in the Core Commitments for Children in Humanitarian Action (CCCs) in line with international standards and guided by humanitarian principles. Key achievements: In 2016 UK support to UNICEF’s humanitarian action has helped contribute to: • supplying 28.8 million people with safe drinking water • providing 24.2 million measles vaccinations to children • treating 2.4 million children with severe acute malnutrition. |

| The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) | |

| Total contributions to OCHA in 2016: £0.26 billion | Mission: OCHA is the part of the UN Secretariat responsible for bringing together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies. OCHA also ensures there is a framework within which each actor can contribute to the overall response effort. Key achievements: In 2016 UK support to OCHA has helped contribute to: • providing technical and operational expertise to 40 countries responding to crisis in 242 surge deployments managing CERF • managing 18 country-based pooled funds, with a total value of $713 million. |

| The Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) | |

| Total contributions to CERF in 2016: £0.43 billion | Mission: Established in 2005 as the UN’s global emergency response fund, CERF pools contributions from donors around the world into a single fund allowing humanitarian responders to deliver life-saving assistance. It disperses rapid response grants when a new crisis hits and grants to under-funded emergencies which support unmet needs in protracted crises. It is managed by a secretariat within OCHA. Key achievements: In 2015 UK support to CERF has helped contribute to: • addressing sudden-onset and under-funded crises, providing vital funding to 436 projects across 45 countries affected by crisis • supporting humanitarian organisations providing water, sanitation, hygiene and other assistance to 18.7 million people affected by humanitarian crises, health services to 12.8 million, food assistance to 10 million, protection to 5.7 million. |

| The International Organization for Migration (IOM) | |

| Total contributions to IOM in 2016: £1.00 billion | Mission: IOM works to help ensure the orderly and humane management of migration, to promote international cooperation on migration issues, to assist in the search for practical solutions to migration problems and to provide humanitarian assistance to migrants in need, including refugees and internally displaced people. Key achievements: In 2015 UK support to IOM has helped contribute to: • assisting up to 5.2 million people across 40 countries with its shelter activities • facilitating resettlement activities for about 126,000 refugees from over 130 countries • preventing disease outbreak by vaccinating 117,731 internally displaced people against cholera. |

Sources: Total contributions is in constant 2016 prices. Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2018, Development Initiatives, 2018, p.46, Performance agreement with the UN Humanitarian Agencies and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, DFID, February 2018 (accessed October 2018).

The four UN agencies and two funds that are the focus of this review vary significantly in size, mandate and governance. WFP is a major operational body with the mandate to provide food aid and improve nutrition and resilience. Its 2017 revenue was $6 billion.9 By contrast, OCHA is a coordinating body, with a 2017 budget of just £241 million. They are not all ‘agencies’ in the sense used within the UN. Four (IOM, UNHCR, WFP and UNICEF) are ‘operational agencies’, while OCHA is part of the Secretariat to the UN General Assembly and CERF is an OCHA-managed funding instrument. However, DFID uses the term ‘agency’ as a catch-all description for its UN partners and we adopt it here for simplicity.

In addition to their operational role in the delivery of humanitarian aid, UN agencies play an important normative role for the international humanitarian system. They set standards, identify and prioritise needs, provide leadership and coordination and help to broker agreement on global humanitarian principles and policy.

The UN agencies sit within a complex network of national and international actors that respond to humanitarian crises. This is certainly not a neat and orderly international humanitarian ‘system’. In this report we use the term international humanitarian system to refer to “the network of inter-connected institutional and operational entities through which humanitarian assistance is provided when local and national resources are insufficient to meet the needs of the affected population”. However, it is important to remember that the UN and OCHA cannot direct this system; they rely on coordination and persuasion.

The literature suggests that there are both strengths and weaknesses to the UN humanitarian system. Compared to other options for delivering humanitarian aid, UN agencies offer a number of unique advantages: their neutral international mandate that gives them access to conflict-affected areas that may be closed to bilateral donors, their normative and convening role and their ability to operate globally and at scale. There is a broad consensus that the UN generally does a good job of getting help to those in need, often in dangerous places and at considerable personal risk to the aid workers involved. These advantages have been endorsed by the UK and other donors through their decision to entrust ever-larger amounts of humanitarian funding to the UN.

On the other hand, the UN system is large and unwieldy. While the agencies each have distinct mandates (for example WFP for food assistance, UNHCR for refugees, UNICEF for children), there is significant overlap in their roles. The complexity of the UN architecture creates challenges with leadership and coordination. Because donors are required to choose which agencies to support in particular emergencies, the pattern of funding encourages UN agencies to compete with each other, rather than collaborate. While there is no question that the UN is successful at saving lives, the nature of the UN system itself leads to widespread inefficiency. The rapid growth of global humanitarian funding in recent years has placed it under considerable strain, while increasing the demand from donors for greater efficiency.

There is therefore a broad consensus, in the literature and among international donors, that the UN humanitarian system needs reform. DFID’s core funding business case describes the UN humanitarian system as hampered by “siloed approaches, structural inefficiencies and sometimes destructive competition between agencies. Agencies carry out their own needs assessments, develop their own plans and work under separate leadership structures. In the current system, priorities are frequently defined according to what the agencies can supply, rather than what beneficiaries need most.”

There is a long history of attempts by the international community to reform the UN humanitarian system, with mixed success. There have been measures to improve leadership and coordination across agencies, including:

- shared needs assessments

- stronger, better prioritised joint UN funding appeals for particular crises, with mechanisms to allocate funding across agencies according to need

- the introduction of UN humanitarian coordinators to act as the senior UN official in crises and efforts to strengthen their role

- the development of the ‘cluster system’ for humanitarian coordination, whereby UN agencies, national government bodies, NGOs and others active in a particular sector coordinate their efforts.

There have also been efforts to improve overall humanitarian practice, which apply both to UN agencies and to other humanitarian actors and donors. The most recent of these was the ‘Grand Bargain’ – an agreement between humanitarian donors and delivery partners setting out areas for improvement on both sides (see Box 3). Key reform objectives over the review period have included:

- more investment in building the resilience of communities that are vulnerable to disasters

- increasing the accountability of humanitarian aid deliverers to affected populations

- more use of national and local actors in humanitarian assistance, to build their capacity (known as ‘localisation’)

- a shift towards more use of cash transfers as a form of humanitarian assistance, which in the right circumstances is considered a more effective way of restoring lives and livelihoods than providing food and other items

- a shift towards unconditional and multiannual humanitarian funding, to give agencies greater ability to respond efficiently to needs.

These efforts have achieved incremental change in various areas, resulting in some improvements in performance. However, the core characteristics of the UN system remain unchanged. A DFID assessment concluded that the reform efforts “have not been strong enough to overcome systemic inertia and resistance to change”.

Reform is made more difficult by the consensual nature of the UN system. Change requires agreement among UN member states, which is difficult to achieve. UN agencies are subject to competing demands from member states and donors, giving them a justification for resisting the demands of any single donor. UNHCR and WFP both depend on the US for approximately 40% of their funding, making any major reforms difficult without US support. Successful reform therefore requires collaboration and coalition building among donors, as well as buy-in from the agencies themselves. Furthermore, the continued reliance on the UN by donor countries to deliver ever-larger amounts of humanitarian aid tends to dilute pressure to reform.

Box 3: Timeline of reform initiatives

From 2005 to 2011, the Humanitarian Reform Agenda introduced a new approach to coordination (the ‘cluster’ system) aimed at strengthening coordination and leadership among humanitarian actors within and across sectors (food, shelter, water etc). It also bolstered the UN humanitarian coordinator system (the appointment of a senior UN official in each crisis-affected country to coordinate humanitarian action across UN agencies). It introduced specific innovations in humanitarian financing aimed at better allocating funding according to need, rather than agency mandates. DFID was a sponsor of the financing components, including a revitalised CERF (grants for rapid response and under-funded emergencies) and the introduction of country-based pooled funds.

From 2011 to 2016, the UN launched what it called the Transformative Agenda. This had a number of critical reform strands with a focus on supporting the leadership role of humanitarian coordinators, better preparedness, a stronger response to the most serious emergencies and a stronger programme management cycle, with a focus on improving the quality of needs assessments, funding appeals and monitoring.

The 2016 World Humanitarian Summit focused on mobilising more resources and achieving efficiency gains to enable a stronger response to the growing humanitarian caseload. At the summit, donors (including DFID) and aid agencies agreed a Grand Bargain: UN agencies and NGOs promised efficiency and effectiveness reforms, while donors committed to harmonising and simplifying reporting requirements. Its ten goals were:

- Greater transparency.

- More support and funding for local and national responders.

- Increased use and coordination of cash transfers.

- Reduced duplication and management costs.

- Improved joint and impartial needs assessments.

- Include the people receiving aid in making the decisions that affect their lives (the participation revolution).

- Increased collaborative multi-year planning and funding.

- Reduced earmarking of donor contributions.

- Harmonised and simplified reporting requirements.

- Enhanced engagement between humanitarian and development actors.

DFID as a humanitarian donor

The UK spends around half of its humanitarian aid through the UN system. The remainder is spent through the Red Cross Movement, international NGOs, national governments and private contractors.

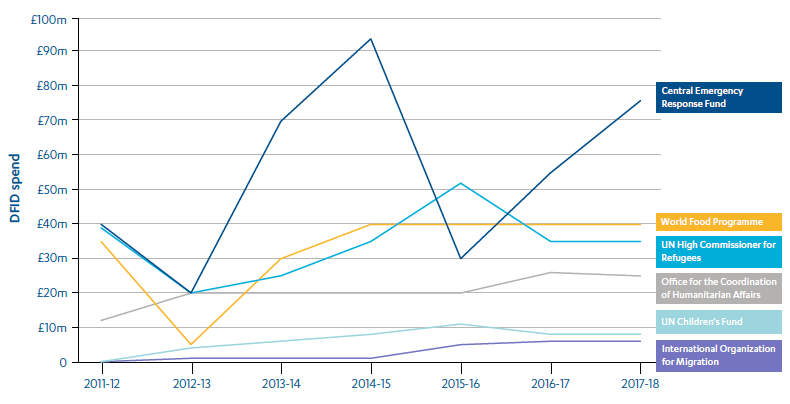

The UK’s overall humanitarian expenditure has grown by more than 200% during the review period. The amount spent through the UN has increased proportionately, from £241 million in 2011-12 to £846 million in 2017-18 (see Figure 3). It takes a number of forms:

- Core funding to agencies’ global budgets. Core funding is unearmarked funding that can be used for any purpose. It allows agencies to fund their central operations and staff and invest in training and preparedness. It also provides flexible funding that can be applied to sudden-onset or under-resourced crises.

- Contributions to the UN’s Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), which are held in reserve to be called down at short notice to facilitate rapid response to humanitarian emergencies.

- Funding given in response to appeals for specific emergencies, either directly to individual agencies or through country-based pooled funds.

DFID’s core funding to UN humanitarian agencies and CERF is managed by its Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department, while its non-core funding is decentralised to country offices.

Figure 3: Breakdown of DFID’s humanitarian spend from 2011-12 to 2017-18

Source: Statistics on International Development, DFID (accessed November 2018).

Core funding currently represents 23% of DFID’s total humanitarian funding through UN agencies, while the rest is pledged in response to specific emergencies. Since 2011, DFID has been committed in its policy documents to increasing core funding to the most effective humanitarian agencies, in recognition that this improves the efficiency of the overall humanitarian response. Over the review period, the overall amount of core funding has in fact increased (with variations across agencies), although not as fast as funding for specific emergencies (see Figures 3 and 4 ).

Figure 4: Breakdown of DFID humanitarian spend through the UN from 2011-12 to 2017-18

Source: Statistics on International Development, DFID (accessed November 2018).

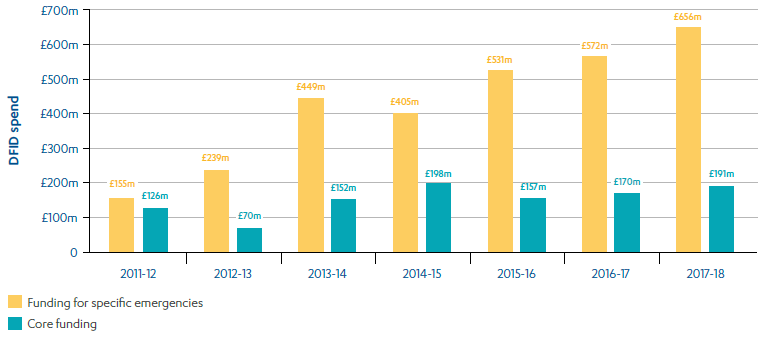

Figure 5: DFID core funding to UN agencies and funds from 2011-12 to 2017-18

Source: Statistics on International Development, DFID (accessed November 2018).

The significance of UK core funding differs across UN agencies. For some of the large agencies, it is such a minor share of overall resources that the influence it affords the UK is likely to be limited. However, the UK is one of the largest donors to both OCHA and CERF and its level of core funding makes a significant difference to their ability to operate.

Beyond the UN, most of the UK’s other humanitarian aid goes to international NGOs and the Red Cross Movement. However, given the scale of UK humanitarian expenditure, DFID is unable to manage large numbers of individual grant agreements with NGOs directly. Other than funding through the UN, the options include working with NGO consortia or engaging private-sector suppliers to manage the grant-making process. For large-scale humanitarian responses, DFID often prefers to use a combination of delivery channels, both via the UN and outside, in order to spread risks and maximise coverage.

DFID’s funding is just one part of its overall engagement with the UN humanitarian system. DFID works with UN agencies centrally, playing an active role on executive committees, while DFID humanitarian advisers in emergency contexts work closely with their UN counterparts. DFID’s influence on the UN system therefore comes about through a combination of different funding flows and levels of engagement. DFID’s decentralised structure means that country offices retain a high degree of autonomy in deciding which organisations to fund for specific humanitarian responses. DFID also coordinates with other donors in its engagement with UN humanitarian agencies at board and executive committee level, in key global forums such as the Inter-Agency Standing Committee, the Good Humanitarian Donorship Initiative and reform efforts such as the Grand Bargain and Transformative Agenda.

Findings

Relevance: To what extent have DFID’s choices of funding channels and mechanisms for UN humanitarian agencies been relevant to its strategy and objectives for strengthening the humanitarian system?

In this section, we assess whether DFID has a coherent strategy for using its core funding of UN humanitarian agencies to advance its objectives for reform of the humanitarian system.

DFID has actively promoted improvements in humanitarian practice, with clear and well-considered objectives

We find that DFID has pursued a clear and explicit set of objectives for strengthening the UN humanitarian system – and wider humanitarian practice – throughout the review period. In 2011, it commissioned an independent review of UK humanitarian response, entitled the Humanitarian Emergency Response Review. The review called for DFID to play a leading role in reforming the UN system. DFID accepted the recommendation and set out the reforms it would champion in a humanitarian policy in 2011. This was updated in 2017. More detailed reform objectives are set out in its 2017 joint business case for UN humanitarian core funding.

Some of these objectives have been pursued consistently across the review period. Others emerged from ongoing international dialogue on humanitarian reform. DFID’s core priorities include:

- Strengthening the UN’s humanitarian leadership, at both the strategic and operational levels, and improving coordination in humanitarian action, including by supporting the UN’s Inter-Agency Standing Committee and OCHA for global and in-country coordination and the appointment of humanitarian coordinators for specific emergencies.

- Promoting collaborative approaches to need assessments, so that agencies can coordinate around a shared understanding of humanitarian need, and encouraging assistance based on the needs of beneficiaries, rather than agency mandates.

- Promoting pooled funding mechanisms (including CERF and country-based pooled funds) so that resources can be directed flexibly to under-funded areas and emerging needs.

- Promoting long-term investments in building resilience to disasters among vulnerable populations, and facilitating a smooth transition from humanitarian to development assistance in the post-crisis recovery phase.

- Increasing the use of cash transfers as a form of humanitarian assistance, instead of giving food or household items (see Box 5).

- Increasing transparency in the provision of humanitarian aid, particularly through the publication of information on expenditure to the International Aid Transparency Initiative.

- Increasing the accountability of humanitarian actors to beneficiaries (‘accountability to affected populations’).

- Putting national and local actors at the centre of humanitarian response (‘localisation’) so as to build their capacity to respond to emergencies.

DFID also made commitments to strengthening its own humanitarian funding practices. It committed to increasing core funding for the most effective multilateral humanitarian agencies. It pledged to increase the predictability and timeliness of UK funding, including by making early responses to humanitarian appeals, providing multi-year funding, contributing to pooled funds and fast-tracking its assistance. Predictable, multiannual and unconditional funding gives UN agencies more flexibility to match funding to need. They are better placed to manage the financial risks associated with the unpredictability of most of their other funding. They are also able to allocate funds to emergencies that do not attract enough donor support.

The multilateral system has the mandate and experience to be the first line of response to humanitarian emergencies when international assistance is required. The UK has committed to significantly increase its core contributions to those multilateral agencies that have demonstrated they can deliver swiftly and appropriately to emergencies.

Saving lives, preventing suffering and building resilience: The UK Government’s humanitarian Policy, DFID, 2011, p. 7.

The reform objectives that DFID has pursued have reflected the evolving international dialogue on strengthening humanitarian practice. They have been aligned with the core principles of humanitarian action and the principles of ‘Good Humanitarian Donorship’, first drawn up by a group of donors in 2003 (see Box 4). DFID was active in the lead-up to the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit, and elements of its thinking are reflected in the Grand Bargain. DFID has also taken up some new issues that have emerged from international discussions over this period, such as the localisation agenda.

Box 4: International principles governing humanitarian action and financing

The four core principles of international humanitarian action:

- Humanity – To save lives and alleviate human suffering wherever it is found and respecting the dignity of those affected.

- Impartiality – Action is based solely on need, giving priority to the most urgent cases of distress, and without discrimination.

- Neutrality – Humanitarian action must not favour any side in an armed conflict or engage in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature.

- Independence – Humanitarian action must be autonomous from political, economic, military or other objectives.

Good Humanitarian Donorship principles:

- Be guided by the principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality and independence.

- Promote adherence to international humanitarian, refugee and human rights law.

- Ensure flexible, timely and predictable funding and reduce earmarking.

- Allocate funding in proportion to needs.

- Involve beneficiaries in the design and evaluation of humanitarian response.

- Strengthen local capacity to prevent, prepare for and mitigate crises.

- Support the UN, the Red Cross and NGOs and affirm the primary position of civilian organisations in humanitarian crises.

- Support learning and accountability initiatives and encourage regular evaluation.

Overall, we find that DFID’s reform priorities have been well considered, reflecting evidence from the literature on the shortcomings of the UN humanitarian system and international humanitarian action more broadly. In multiple interviews at headquarters and country levels, UN staff described DFID as a thought leader on many of these areas – particularly on issues such as joint needs assessments, cash transfers and accountability to affected populations that cut across agency mandates. This thought leadership comes about through well-qualified technical staff, particularly at country level through DFID’s network of humanitarian advisers, active engagement at board level and in key global forums, and through support to research, evidence collection and country-level initiatives on objectives such as cash, accountability and needs assessments.

Box 5: DFID’s advocacy for cash as a form of humanitarian support

A core priority for DFID throughout the review period has been promoting the use of cash transfers as a form of humanitarian support. There is a growing evidence base that, under the right conditions, cash transfers can be more efficient and effective than distributing food or other humanitarian supplies. If local markets are operating, it allows the recipients to purchase the items they need the most, while helping to preserve their dignity. While distributing food aid can suppress local food markets, cash transfers can stimulate them, leading to faster recovery. In the past, reliance on food aid has led UN agencies to provide supply-driven support, based on the resources they had available, rather than tailoring their assistance to the needs of beneficiary communities. Cash assistance is a solution to that problem. DFID also sees the shift towards cash transfers as a useful driver of UN reform, cutting across organisational mandates and sectoral siloes.

Figure 6: Evolution of DFID’s funding approach and reform objectives

Doing cash differently. How cash transfers can transform humanitarian aid. Report of the high level panel on humanitarian cash transfers, ODI and CG-Dev, September 2015.

DFID has used core funding to support other efforts to strengthen UN humanitarian agencies

DFID is a major funder of the UN humanitarian system. In 2016 it was the largest donor to OCHA and the country-based pooled funds and the second-largest to CERF, UNHCR, UNICEF and WFP. We find that DFID has used its core funding strategically to support its reform objectives.

DFID’s position as a major funder supports direct engagement with the agencies at both headquarters and country levels. DFID internal documents show that it has been active on agency boards and executive committees, and within the OCHA Donor Support Group, in pushing forward its policy priorities. In our interviews with other donors and UN staff, DFID is described as coordinating well with other donors on reform priorities at headquarters and country levels. For example, in 2018 DFID worked with ‘List D’ donors to broker a joint request to WFP to improve its risk management.

Core funding for OCHA and CERF provides a platform for the UK to promote UN leadership of international humanitarian response and improved coordination across agencies. Since 2007, the position of emergency relief coordinator (currently held by Sir Mark Lowcock, formerly DFID’s permanent secretary) has been awarded to a UK national. The UK is also active in the OCHA donor support group. DFID was a prime mover behind the establishment of CERF in 2006 and has been its biggest funder since its inception, providing £653 million or 19.6% of total contributions between 2008 and 2017. It has also been an important contributor to country-based pooled funds.

Over the review period, DFID introduced a new element into its decision-making on allocating core funding to multilateral partners, for both humanitarian and development aid. The 2011 Multilateral Aid Review assessed agencies according to their strategic fit with UK policies and their organisational effectiveness. This assessment informed the amount of core funding allocated to each body. A more detailed description of the process can be found in our 2015 review on How DFID works with multilateral agencies to achieve impact. The assessment was repeated in 2016 (this time called the Multilateral Development Review), to inform DFID’s next round of multilateral funding.

For the 2011 to 2015 period, DFID prepared separate business cases for its core funding to each agency. These set out DFID’s expectations for how each agency should improve its performance, including by addressing shortcomings identified in the multilateral aid review. They included performance assessment frameworks with indicators, against which each agency reported its progress. There was a consistent focus on managing for results, risk management and value for money. There were also expectations specific to each agency. For example, WFP was expected to improve its food supply chain management, its leadership of the food ‘cluster’ and its support to national governments on preparedness, resilience and nutrition.

Overall, we find that DFID has made active use of the influence gained through its core funding to push for improvements at the agency level. We note, however, that this is against a background of increased UK humanitarian expenditure through the UN. This is consistent with the commitment DFID made in its 2011 humanitarian policy to providing predictable, multiannual funding and to increasing its core contributions to the most effective international agencies. However, across-the-board increases in funding (against a background of rapid growth in global humanitarian need) have arguably weakened the pressure on UN agencies to reform.

There are gaps in DFID’s approach to reform, particularly around the UN’s normative role and its management of delivery partners

While improving the value for money of humanitarian aid through the UN has been a DFID priority, there has been a distinct gap regarding its attention to the UN’s role as a subcontractor of non-government organisations (NGOs). This function is central to its value proposition to DFID: the department chooses to fund relief operations through the UN agencies in large part because it is not in a position to manage large numbers of smaller contracts. We would therefore have expected to see DFID paying more attention to what value the UN adds through its subcontracting and whether that justifies the management overhead (the proportion of funding that UN agencies keep to cover their costs of managing contractors).

Our interviews with international NGOs at both headquarters and country levels pointed to some serious weaknesses in UN subcontracting practices. For example, NGOs in South Sudan described the UN as a ‘painful’ fund manager with onerous contracting terms and complained of a lack of support from donors, including DFID, on holding the UN to account. In interviews at headquarters and country levels, DFID staff acknowledge that they had limited visibility of the UN’s subcontracting practices and little understanding of management overheads down the delivery chain. The literature also points to the need for a better understanding of the purpose and value of UN agencies sub-granting to NGOs.

Since April 2017, DFID has begun to ask UN agencies to map their delivery chains, with the focus on improving value for money and ensuring that funds do not reach inappropriate organisations. DFID is also asking UN agencies to pass on the benefits of multi-year funding to delivery partners. However, this has had limited traction, as the processes by which UN agencies subcontract delivery partners are mostly determined at headquarters level. Across the case study countries, DFID country office staff told us that they needed more support from headquarters and from DFID offices in Rome, New York and Geneva on this issue.

The treatment of women and marginalised groups is another area that has been under-emphasised in DFID’s engagement with UN agencies. The annual synthesis report on progress since the World Humanitarian Summit found that the political commitment to gender-responsive programming expressed at the summit has not been translated into practice. In its 2017 Humanitarian Reform Policy, DFID states that it will promote minimum standards for the protection of children, women, people with disabilities and the elderly in emergencies. DFID has supported the adoption of non-binding standards regarding age and disability in humanitarian action. However, in interviews with UN staff, there was little mention of gender, age or disability being raised by DFID as a reform objective.

DFID’s move to a joint business case and payment by results for UN agencies represents an ambitious shift in focus from agency to system-wide performance

DFID’s core funding in the 2011 to 2015 period focused on encouraging incremental improvements in organisational performance at the individual agency level. It did not address systemic issues, such as overlapping mandates, joint needs assessments or improved accountability. From 2015, DFID added new elements to its core funding approach in an attempt to address system-wide performance issues.

From 2015 to 2017, DFID piloted a single business case for core funding to all UN humanitarian agencies, with collective performance indicators that they were expected to report on jointly. While the focus on individual agency management reforms continued, the new business case was also designed to encourage changes in their joint behaviour.

For the period 2017 to 2021, DFID has a single business case for UN humanitarian agencies with inbuilt performance incentives.

- 30% of the funding is conditional on DFID’s assessment of their joint progress in implementing a selection of Grand Bargain commitments (see Box 6). DFID may choose to withhold some or all of this funding if it judges progress by the group as a whole to be inadequate. DFID describes this as ‘payment by results’, although the conditionality relates to reforms, rather than results for aid recipients. (There is also a payment by results element for 30% of DFID’s core funding to UN development agencies.)

- The remaining 70% of the funding is guaranteed for the period of the business case, although shortfalls in individual agencies’ performance might affect the level of core funding they receive in the next funding period, from 2021.

Box 6: DFID’s use of payment by results

DFID uses the term ‘payment by results’ (PBR) for any programme where a portion of the payment is made after the achievement of pre-agreed results, rather than in advance to support activities. DFID’s contracts with implementing partners – including commercial suppliers and NGOs – increasingly include elements of PBR.

DFID sees PBR as sharpening performance incentives for implementers by requiring them to share the delivery risks. By encouraging more emphasis on performance standards and measurement systems, it generates greater accountability for results.

PBR also has recognised risks: it can be complex to apply and administer, requires independent monitoring and can create unhelpful incentives or unintended effects. As DFID’s own PBR strategy notes, evidence on how to do PBR right is still emerging.42 A DFID smart guide on PBR therefore recommends a flexible approach to its use. ICAI’s recent review of DFID’s procurement processes finds that PBR “remains a new field where further learning is required”.

The application of PBR to UN agencies is novel and DFID sees the approach as an experiment.

We welcome this evolution in the approach to a system-wide focus. It accords with DFID’s own diagnosis that performance shortfalls in the UN humanitarian agencies are due to systemic issues as well as organisational capacities. It also accords with ICAI’s 2015 review of DFID’s work with the multilateral system as a whole, which called for a more strategic approach to the multilateral system. It strengthens the alignment between DFID’s core funding approach and its wider humanitarian reform agenda.

The use of payment by results in core funding for multilateral agencies was untested at the time of its introduction. It was foreshadowed in the multilateral development review for UN agencies, but with funding linked to the achievement of “concrete outcomes on the ground” rather than complex reforms. DFID hopes that it will create incentives for improvements in collective performance, breaking with the traditional pattern of UN funding that drives a level of competitiveness between agencies and can work against the efficient functioning of the system as a whole. By attaching funding to Grand Bargain commitments, it also creates incentives for the agencies to define those commitments more precisely and demonstrate their progress in meeting them. Given the difficulty of achieving structural reform of the UN, the idea of using funding to create incentives for better collective performance is innovative. However, we come back under our third review question later to whether DFID has been able to craft a payment by results mechanism that creates an effective set of performance incentives.

Box 7: Payment by results to UN humanitarian agencies

Under a 2017 to 2021 joint business case for core funding to UN humanitarian agencies, 30% of the funding is conditional on their making satisfactory progress as a group towards a set of reform objectives drawn from the World Humanitarian Summit and Grand Bargain commitments. If DFID assesses that progress has not been satisfactory, it may withhold some or all of the funding. The conditions include:

- improve joint impartial and timely needs assessments

- increase the use and coordination of cash-based programming

- manage risk better, build resilience and strengthen preparedness

- multi-year comprehensive response in protracted crises and better engagement between humanitarian and development actors

- increase transparency on financing and operations

- focus on the protection risks of vulnerable people in assessment, planning and response

- increase accountability by seeking feedback and communicating with affected populations.

The remaining 70% of funding is guaranteed. However, DFID will track each agency’s performance against a set of commitments and performance may influence the amount of core funding offered to the agencies after 2021. The commitments include:

- demonstrate leadership in line with agency’s mandate and humanitarian country team/cluster responsibilities

- quality, timeliness and flexibility of the response and protection of population in need

- reduce management costs

- improve value for money

- improve reporting

- strengthen ‘localisation’ (delivery through national and local partners)

- uphold legal norms and humanitarian principles and maintain access.

Conclusions on relevance

Throughout the review period, DFID has been an active and engaged funder of UN humanitarian agencies, with a well-articulated and relevant set of objectives for improving the performance of individual agencies, strengthening the UN humanitarian system as a whole and improving global humanitarian practice. It is recognised as a thought leader around a number of its reform objectives, including joint needs assessment and the use of cash transfers for humanitarian support. It has been a champion of pooled funds at international and country levels, and has used its core funding to strengthen OCHA and CERF. DFID has been active in promoting its reform objectives in international processes such as the Grand Bargain, while also adjusting its approach in response to new principles emerging from international dialogue.

Through the multilateral aid/development reviews, DFID pioneered the use of core funding and associated performance frameworks to drive improvements in organisational performance at the agency level. We find that it has communicated clear expectations for performance improvements and provided transparent metrics for agency-specific reforms – although the parallel increase in levels of funding may have diluted the pressure for reform. There are, however, some key gaps in DFID’s reform priorities relating to how UN agencies subcontract NGOs and the priority given to issues of gender equality, ageing and disability in humanitarian practice.

Since 2015, through its joint business case and then the introduction of a payment by results element into its core funding, DFID has shifted its attention to improving collective performance across the UN system. While this remains untested as a means of incentivising complex reforms, it is a welcome increase in ambition and a break from the traditional pattern of UN funding that promotes unhelpful competition among agencies.

The clear objectives and DFID’s willingness to innovate in its core funding approach merit a green-amber score for relevance.

Efficiency: Has DFID’s funding of UN humanitarian agencies led to improvements in their individual management practices, capabilities and performance?

In this section, we examine whether DFID’s funding of UN humanitarian agencies over the review period has led to improvements in their individual management practices, capabilities and performance.

DFID’s use of multiannual core funding has strengthened the UN’s ability to respond to emergencies

Through the review period, DFID has provided multiannual core funding to UN humanitarian agencies, with four-year commitments. This is in line with the undertaking it made in its 2011 humanitarian policy, which was reinforced in the Grand Bargain. This predictability is highly valued by the agencies. While each manages and allocates core funding differently, in interviews they all described it as critical to their overall effectiveness, enabling them to build up and sustain their operational capacity in key areas. DFID has been a leading donor in providing multi-year funding at both core and country levels. In 2017, the UK provided 89% of its humanitarian funding in multi-year agreements.

Core funding supports the development of new policies and approaches at headquarters level. For example, core funding enabled WFP to develop a central unit to build capacity across the organisation to provide cash transfers. It also enables efficiency gains at country level. For example, in South Sudan, multi-year funding enables agencies to pre-position relief supplies across the country, in anticipation of seasonal flooding. This reduces the need to rely on expensive air drops when large parts of the country are cut off during the rainy season.

The literature also suggests that multiannual funding offers better value for money than short-term funding, allowing better financial planning, reducing transaction costs and improving procurement practice. A DFID-commissioned study noted the potential for substantial value for money gains from a shift to multi-year funding. A four-country study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Pakistan, Ethiopia and Sudan also found clear benefits. In its efforts to prevent famine in Ethiopia, by purchasing humanitarian supplies at the optimal time, WFP spent between 18 and 29% less than if it had done so after the onset of food shortages. In the DRC, long-term funding enabled a UNICEF cash transfer programme to commission studies to improve delivery and reduce delivery costs by giving fewer, larger grants. However, the benefits of multiannual donor funding are frequently lost because UN agencies often continue to subcontract NGOs on a short-term basis, or because their management systems do not facilitate long-term planning.

DFID has introduced a stronger focus on value for money and risk management into the UN humanitarian system

Over the review period, DFID has had a strong focus on improving performance at the agency level. The multilateral aid review process was a significant innovation in the use of core funding that helped to drive an increased focus on results, risk management and value for money.50 DFID has since introduced additional assessment processes such as central assurance assessments, due diligence and delivery chain mapping. These have given it leverage to push for greater rigour in results reporting and risk management.

In interviews, UN and DFID officials offered a number of examples of positive changes to agency management systems and processes that resulted from DFID’s interventions. For example:

- DFID linked its core funding to IOM to improvements in results-based management and seconded a staff member to IOM headquarters to support changes to some core management systems.

- A DFID central assurance assessment of UNHCR carried out in 2017 highlighted the need for UNHCR to develop stronger risk management processes. An action plan is being agreed to respond to the findings which includes the development of a control framework, more proactive engagement with donors on fraud investigations, controls for downstream partners and clarifying and strengthening UNHCR’s approach to value for money.

- DFID played a leading role in brokering a joint donor request to WFP to improve its risk management. The joint statement called for a “comprehensive and overarching vision for WFP’s control environment, one that includes WFP’s plans to define its risk thresholds and to revise its current risk frameworks, policies and assurance statements”. Together with DFID’s central assurance process, this has led to the development of an updated oversight framework for WFP.

- DFID successfully advocated for CERF to reduce its management costs from 3% of total spend to 2%, freeing up more funding for operations.

DFID’s strong push for more use of cash transfers in humanitarian aid and more efficient ways of delivering it has also produced value for money gains. For example in Lebanon, DFID encouraged WFP to move from vouchers to cash and argued for a common approach to managing cash transfers across UN agencies. It has made effective use of evidence, including a value for money study and a study on the relative efficiency of cash and vouchers, to make the case for change.51 The study found that unrestricted cash raised the recipient’s purchasing power by 15% to 20%, compared to vouchers for use in WFP shops.

This accords with our 2015 review of DFID’s work with multilateral agencies, which noted DFID’s success in improving the monitoring and reporting of results across its multilateral partners. In our review of DFID’s humanitarian support in Syria, we noted that DFID’s partners were now regularly reporting on unit costs and other value for money indicators.

While these changes have been positive, the pace has been relatively slow. DFID’s ratings of the UN humanitarian agencies in the multilateral aid and development reviews have remained static over the review period (2011-18) – although DFID acknowledges that it judged them against tougher standards in the later review. Only WFP and UNICEF are rated as ‘good’ on organisational capacity, while UNHCR, CERF and OCHA are assessed as ‘adequate’. However, there have been areas of progress within those overall ratings (see Annex 1 for details).

To maintain the momentum, DFID recognised the need to support its core funding with stronger institutional relationships with UN agencies. It has taken this forward in a number of areas, appointing additional full-time institutional strategy leads to manage the relationship with UN agencies (2017), starting a regular process of senior-level strategic dialogues with UN agencies (2017) and appointing senior staff to key posts in Geneva and New York. While the level of engagement has improved, UN staff in interviews noted that DFID’s knowledge and insight into UN agencies remained patchy and dependent on a few knowledgeable individuals, rather than institutionalised.

In interviews, UN officials described DFID’s engagement on value for money as challenging but instrumental in driving an evolution of practice within the UN and across the wider humanitarian sphere. However, not all stakeholders are in agreement with DFID’s approach to value for money in humanitarian assistance. Some officials noted consistent DFID pressure to identify savings and efficiencies – in other words, ways of delivering a given set of results at a lower cost. There was much less mention of DFID pushing for innovations that would enable more and better results for a given set of resources. Interviewees in our case study countries also suggested that DFID’s reporting requirements paid less attention to issues of quality and impact and did not incorporate enough feedback from the communities receiving assistance. This had led to a perception that DFID is more interested in management processes than in outcomes.

This reflects a finding from the recent ICAI review on DFID’s approach to value for money in programme and portfolio management that DFID’s drive for value for money is often interpreted by partners as pressure to reduce costs, rather than to innovate in order to maximise results. While the drive for value for money is unquestionably important, there is evidence that DFID could strike a better balance between reducing costs and driving up value.

DFID’s reporting and diligence requirements have become increasingly burdensome