ICAI Annual Report 2019-2020

Foreward

ICAI’s third commission began in July 2019. This first ICAI Annual Report of the new commission covers a period of considerable external and internal change. It covers only nine months, from July 2019, when the new commission started, to the end of March 2020. We made this change to move it in line with the financial year, making consistent reporting more straightforward for the future, although this does mean that this report is not comparable with previous reports.

In July we welcomed Sir Hugh Bayley and Tarek Rouchdy as commissioners, and their willingness to begin their tasks immediately meant that we could rapidly build on the work already started on setting new directions, following a public consultation. We brought in the Sustainable Development Goals as an overarching framework, and agreed a new set of proposed reviews for the International Development Committee before the parliamentary recess. We also made some other changes, such as scoring our future follow-up reviews and publishing our literature reviews. Reviewing ICAI’s impact under the previous commission has led us to increase our effort on communications and engagement, and we have benefited from a growing interest in our work.

Given that the most striking feature of the second commission’s time was the fragmentation of the aid budget, with a major increase in spending of official development assistance by departments other than the Department for International Development (DFID), our first review, How UK aid learns, mapped out the work of all 18 aid-spending departments and cross-government funds. We examined how well learning was taking place and ensuring value for money. We also broke new ground in bringing in the voices of those expected to benefit from aid programmes in our new reviews, including 800 Ghanaian citizens who fed in to the first country portfolio review, and survivors of conflict-related sexual violence who provided their perspective on the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative.

We were very pleased to see that, after a significant amount of contact between ICAI and French parliamentarians and officials over some time, legislation was brought forward to establish a French version of ICAI, the Commission Indépendante d’Evaluation. We hope to foster links with the new commission and wish it all success as the French aid programme grows.

There were, however, major changes taking place in our work environment which slowed down our programme. The work to prepare for the UK’s exit from the EU led to a lot of disruption to the parliamentary calendar, postponing sub-committee hearings, while staff redeployment in government delayed the progress of some reviews. The unexpected election in December 2019 caused the most disruption, as the International Development Committee was dissolved and not re-established until March 2020. This meant a considerable delay to hearings, and some work done for the previous committee no longer had the same purpose.

The new committee embarked on an overarching inquiry into the effectiveness of aid, with an eye to ongoing plans to review foreign policy and potentially to merge DFID with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office – plans the government subsequently confirmed in June 2020. We contributed evidence to this inquiry, but the government review was itself halted as the COVID-19 pandemic began to absorb all government resources. At the end of the reporting period, Parliament was shut down because of COVID-19, resulting in disruption to hearings; at the time of writing, it is expected that many ICAI-related hearings will be carried out in written format. This does make it more challenging to hold departments to account effectively. There is also clearly a big impact in the reduction of the capacity of government to provide input, such as factchecking, which is currently causing delays to some reviews.

Nevertheless, continuing scrutiny at a time like this is more important than ever. While attempting to avoid over-burdening departments focused on measures to deal with the pandemic, we are adjusting our programme and ways of working. At the time of writing, we also continue to work with parliamentary and departmental colleagues to ensure that scrutiny continues as plans for the merged Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office take shape. I would like to thank my fellow commissioners, the secretariat, everyone in government and the external stakeholders, whether in the UK or internationally, who have contributed to our work.

Dr Tamsyn Barton

Chief Commissioner

Highlights of 2019-2020

The focus of our reviews

ICAI’s programme of reviews is agreed each year with the International Development Committee (IDC) in the UK Parliament. Our topics are chosen in consultation with a wide range of stakeholders, using four selection criteria: the amount of UK aid involved, relevance to the strategic priorities of UK aid, the level of risk, and the potential added value of an ICAI review. For this year, our review programme also drew on a horizon-scanning exercise we carried out in 2019 to identify emerging challenges for UK aid, as well as a public consultation in which we invited stakeholders and members of the public to raise issues of concern for ICAI to examine.

ICAI is changing its reporting year so as to match the financial year (April to March). As this is the transition year, this year’s Annual Report covers a shorter period of activity – from July 2019 to March 2020. There were five products published in this period, including two scored reviews, one rapid review and two information notes (see Table 1).

Table 1: ICAI 2019-2020 reviews and scores

| Review title | Review type | Publication date | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| How UK aid learns | Rapid review | September 2019 | Not scored |

| The use of UK aid to enhance mutual prosperity | Information note | October 2019 | Not scored |

| The UK's Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative | Joint review | January 2020 | Amber/red |

| The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana | Country portfolio review | February 2020 | Green/amber |

| Mapping the UK’s approach to tackling corruption and illicit financial flows | Information note | March 2020 | Not scored |

In 2019-2020, we introduced a new ICAI scrutiny tool: the country portfolio review. Country portfolio reviews examine the entirety of UK aid to a particular country, by whichever department or channel it is spent, including multilateral aid. With more departments now involved in spending aid, this gives an opportunity to assess whether their collective effort is coherent and coordinated, and whether it is helping the partner country achieve its development objectives. Our first country portfolio review explored how UK aid has responded to Ghana’s achievement of middle-income status and its desire to move to a new form of development partnership.

In 2019-2020, ICAI also produced two information notes to support the IDC with its scrutiny role. One explored the rise of mutual prosperity as an objective of UK aid. The other was a mapping of the UK’s efforts to tackle corruption and illicit financial flows, which involves a significant number of departments and cross-government initiatives. It was requested by the IDC to support a planned inquiry into the UK’s contribution to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16 on ‘peaceful, just and inclusive societies’.

Key themes emerging from 2019-2020 reviews

The complexities of cross-government partnerships

In recent years, the share of UK aid spent by departments other than the Department for International Development (DFID) has grown rapidly, from 14% in 2014 to 27% in 2019, reaching more than £4 billion. UK aid is now spent by 18 departments and funds. In 2019-2020, ICAI continued to explore the consequences of this changing UK aid architecture – including how well aid-spending departments work together on common goals.

How UK aid learns assessed whether departments other than DFID had put in place the learning processes required for high-quality aid spending. It found that they had made important progress in building up learning capabilities, broadly commensurate with the size and complexity of their aid budgets. However, learning was often treated as a stand-alone exercise, rather than integrated into aid-management processes.

The review noted the absence of a structured process for building aid-management capacity across departments – a significant shortcoming, given the challenges involved in delivering high-quality development cooperation. It explored the assistance that DFID provides to other aid-spending departments, including the loan of over 100 staff, while noting that DFID had not received any additional resources for this support. In the Spending Review, extra funding for staff was then allocated for this purpose, which was a welcome step in the right direction. Our review found good examples of departments exchanging learning with each other, through a growing number of cross-government groups and forums. Our review also raised questions about the potential value for money risks of the fragmented procurement of outsourced monitoring, evaluation and learning. Several departments are also investing in information platforms for their aid, although these are not yet interoperable, which undermines the sharing of learning. We also raised issues about transparency as some departments were yet to publish their data to IATI (International Aid Transparency Initiative) standards and non-DFID information about UK aid spend was found to be incomplete on DevTracker.

Tackling corruption and illicit financial flows is an area that has benefited from cross-government partnerships. Since a landmark international anti-corruption summit in London in May 2016, aid-spending departments have addressed the challenge at three levels: programmes that tackle corruption within developing countries, efforts to change international institutions to reduce opportunities for laundering illicit gains, and efforts to ensure that the UK itself is not a safe haven for stolen funds. Our information note on this subject described how the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), the Home Office and DFID were working together on a range of initiatives, such as promoting transparency of beneficial ownership to make it easier to track illicit flows through global financial centres.

The Ghana country portfolio review found that DFID was working well with other UK departments to build a new development partnership based on trade and economic cooperation. The UK has adopted a UK-Ghana Prosperity Strategy and developed an interdepartmental Economic Development Investment and Trade working group in Ghana. This has led to better coordination on promoting trade and investment. However, there are tensions between the UK’s development assistance and its promotion of trade interests that will need to be managed carefully.

Some tensions also emerged in the context of the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI) – a high-profile initiative to tackle conflict-related sexual violence originally launched by former foreign secretary William Hague and Angelina Jolie, in her capacity as Special Envoy of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. While intended to be a tri-departmental initiative, led by the FCO and involving DFID, the FCO and the Ministry of Defence, we found that differences in priorities and approaches across departments had undermined its coherence, and that there had been a lack of effective leadership to enable better collaboration.

The mutual prosperity information note explored growing expectations that UK aid should generate economic and commercial benefits for the UK, as well as recipient countries not only through programmes run by departments with these objectives, but also in DFID programmes. This is part of a wider effort to align the aid programme with the UK’s security, economic and diplomatic interests, known as the Fusion Doctrine. The report noted that while ICAI did not identify any examples of UK aid programmes compromising development impact for secondary benefit in the sample of programme business cases reviewed, there were various risks around the mutual prosperity agenda, including that it might divert the time and energy of staff, blur departmental mandates and incentives, and lead to a reduced focus on poverty reduction.

Sustaining momentum on long-term challenges

An important theme emerging from the 2019-2020 reviews was the importance of sustaining development interventions for long enough to achieve meaningful results. In the Ghana review, we noted that DFID had long been an active supporter of better human development outcomes, helping to promote access to quality education and affordable healthcare, with a strong focus on gender equality and leaving no one behind. In recent years, however, with encouragement from the Ghanaian government, it had shifted its focus from health and education service delivery to the poorest and most vulnerable, to promoting private sector development and economic transformation. The review found that DFID had not done enough to manage the risks around this transition and to ensure that its past investments in the social sectors were sustainable.

In the PSVI review, we found that a high-profile international summit in 2014 had helped to focus international effort on a difficult issue, including through the launch of a new international protocol on investigating and prosecuting offences. However, with the departure of William Hague from office, ministerial interest in the initiative had waned and funding and staffing levels dropped precipitously. As a result, the initiative fell well short of its initial ambition. We also found that most PSVI programming followed one-year project cycles, which is unsuited to tackling such a complex and sensitive issue.

In the area of anti-corruption and illicit financial flows, we noted that international influencing is resource-intensive and needs to be sustained over time to achieve results. With regard to transparency of beneficial ownership, the UK’s efforts had achieved some promising early results, but there are challenges around sustaining the momentum.

Mixed results on measuring transformation

A key theme across ICAI reviews is whether UK aid is able to deliver and monitor transformative results. In Ghana we found that, while DFID had a country strategy, it had not specified its intended outcomes on governance, human development or prosperity. Because results monitoring was all at the programme level, DFID was unable to identify its overall contribution to Ghana’s development outcomes or its progress towards particular SDGs. However, the review recognised that the UK aid portfolio has responded well in most respects to Ghana’s development needs and was well aligned to broader UK aid objectives and commitments. It also found credible evidence that the UK aid portfolio in Ghana was contributing to important results.

The PSVI review found that monitoring systems were not strong enough to track outcomes even at the individual project level. Conflict-related sexual violence is a challenging area in which to obtain and measure results. Some of the individual projects had achieved useful and innovative outputs at the local level, but weaknesses in results data made it difficult to reach any conclusions about overall impact.

In How UK aid learns, we noted that a number of the larger cross-government funds and programmes had engaged commercial suppliers to manage monitoring, evaluation and learning frameworks. This can be an effective means of collecting results data from across a complex portfolio, as well as providing access to additional technical expertise. However, the risk is that the resulting learning accumulates in the supplier team, without being properly absorbed by the department itself. There are also value for money risks, as noted above.

Consultation with people expected to benefit from UK aid programmes

A key theme for ICAI’s work in 2019-2020 has been to ensure that the voice of those expected to benefit is adequately integrated into ICAI reviews, as part of an effort to ensure that it feeds into UK aid programmes. In our Ghana review, we used a national research team to consult with around 800 citizens through a variety of methods, including individual interviews, focus group discussions, town hall meetings and radio phone-ins. The consultations took place in eight of the districts where UK aid is working and produced a rich picture of the priorities of Ghanaian citizens and their experiences with public services and public institutions.

However, we found that consultation with those expected to benefit is not a consistent part of DFID programming. In only six of the ten programmes we reviewed in depth did we find evidence of citizen engagement in programme design, implementation and monitoring.

In the PSVI review, we found that FCO procedures do not require projects to consult with survivors or collect other evidence on survivor needs. The experts we consulted believed that such consultations are essential to identifying effective interventions centred on the needs of survivors.

ICAI will continue to make consultation with people expected to benefit a strong focus of its work. It was very good to see increased emphasis on this in DFID, with the publication of its Smart Guide (a DFID best practice guide), as this responded to ICAI’s sustained focus on this issue.

ICAI functions and structure

This chapter sets out the structure and functions of ICAI.

ICAI’s structure and functions

ICAI was established in May 2011 to scrutinise all UK official development assistance (ODA), irrespective of spending department. ICAI is an advisory non-departmental public body. ICAI is sponsored by DFID but delivers its programme of work independently and provides its reports to Parliament’s International Development Committee.

Our remit is to provide independent evaluation and scrutiny of the impact and value for money of all UK government aid spending. To do this, ICAI:

- carries out a small number of well-prioritised, well-evidenced, credible thematic reviews on strategic issues faced by the UK government’s aid spending

- informs and supports Parliament in its role of holding the UK government to account

- ensures its work is made available to the public.

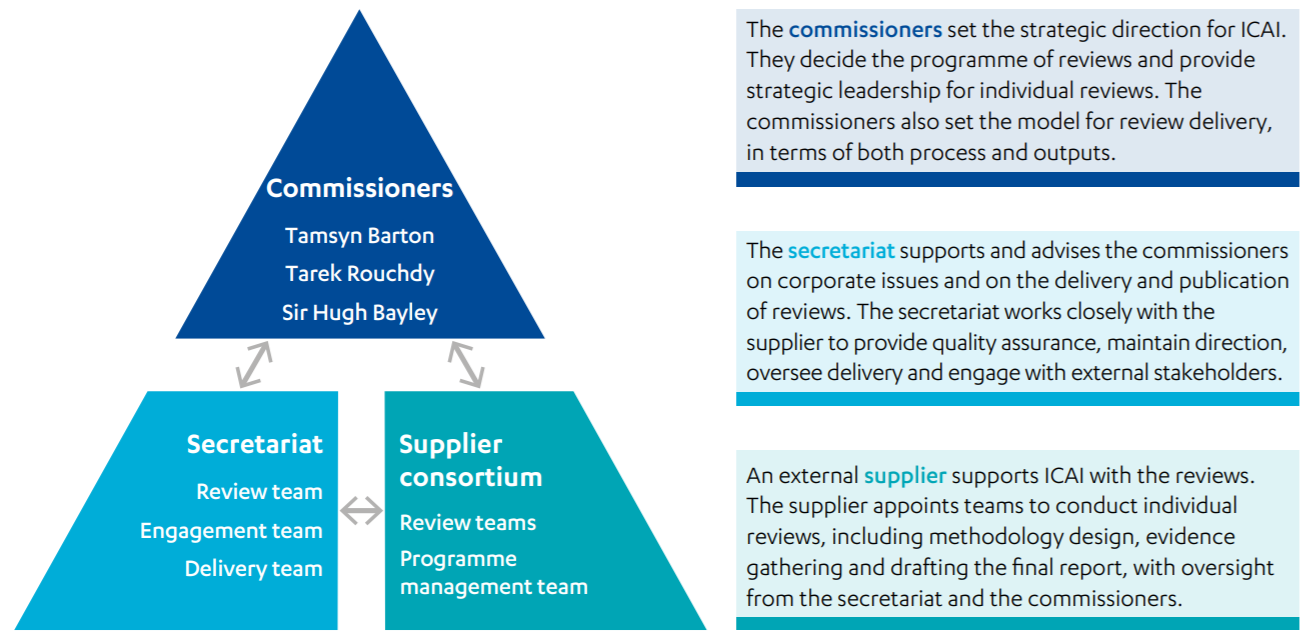

ICAI is led by a board of independent public appointees (the commissioners) who are supported by a secretariat and an external supplier. These three pillars – commissioners, secretariat and supplier – work closely together to deliver reviews. The high-level roles and responsibilities of the three pillars are summarised in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: High-level roles and responsibilities

ICAI’s theory of change

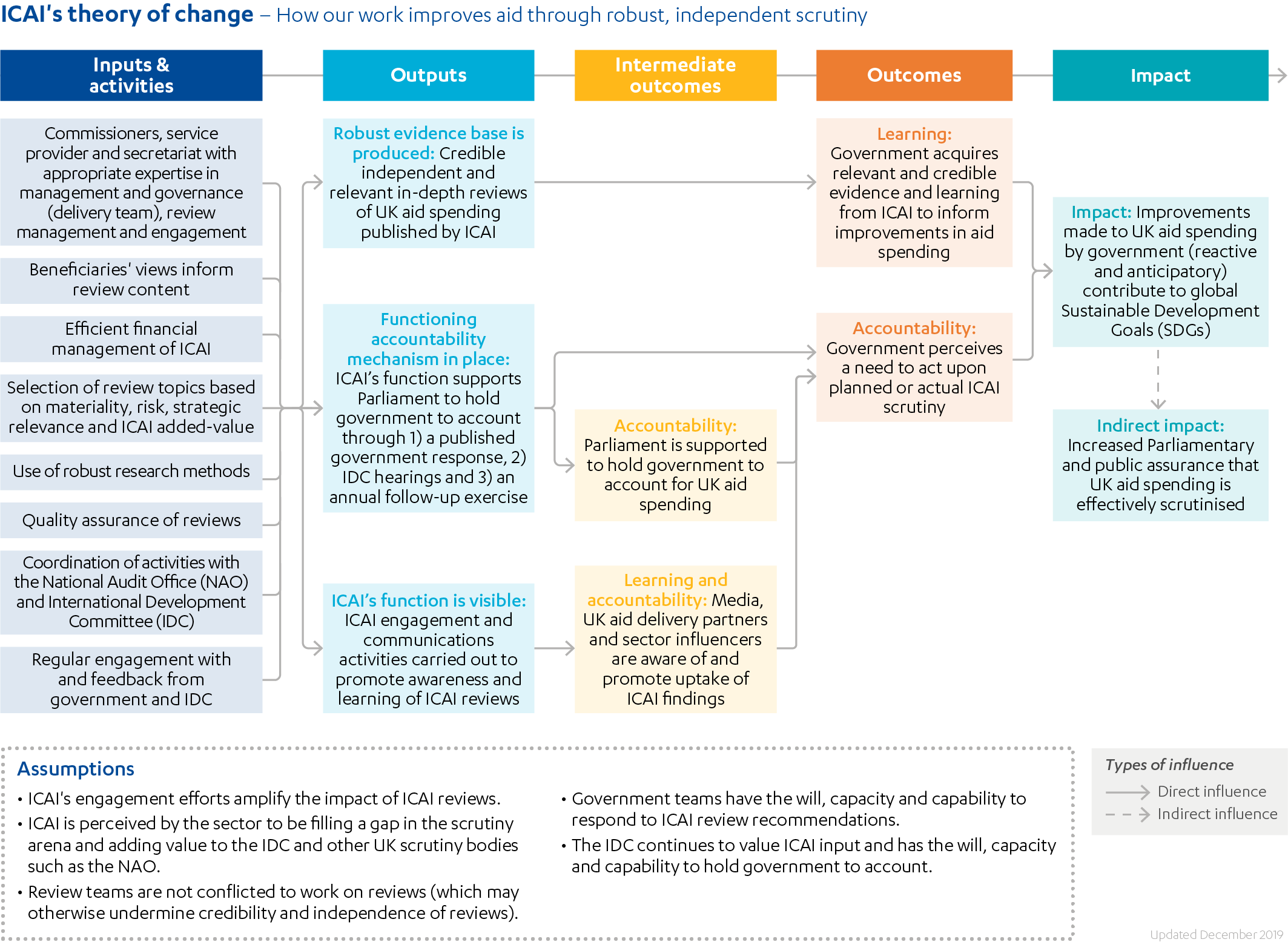

ICAI developed a theory of change following a recommendation in our 2017 Tailored Review to articulate how our work is expected to deliver improvements in the impact and value for money of UK aid spending. In addition, the theory of change, illustrated in the diagram below, is expected to assist our continuous improvement. Following some work commissioned to understand ICAI’s impact so far, and how to increase it, this was updated in December 2019, with a view to it:

- distinguishing more clearly between activities and inputs

- ensuring all ICAI secretariat functions are recognised

- including a greater focus on citizen voice

- linking the intended change in UK government practice to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- being simplified visually.

The ICAI team

The commissioner team is headed by Dr Tamsyn Barton, ICAI’s chief commissioner. ICAI’s other commissioners are Sir Hugh Bayley and Tarek Rouchdy. Tamsyn Barton commenced her term as chief commissioner in January 2019, six months ahead of her fellow commissioners, owing to the early departure of her predecessor, who took up a new post at the World Bank. The commissioners’ biographical details are published on the ICAI website.

ICAI’s secretariat is headed by Ekpe Attah and is made up of ten civil servants. They are responsible for review management (working alongside the external supplier), supplier contract management, financial control and corporate governance, and communications and engagement. The secretariat is based in Gwydyr House, Whitehall.

Agulhas Applied Knowledge, a specialist international development consultancy, is ICAI’s external supplier. During Phase 3 (2019-2023), Agulhas has been supported by Ecorys, ODI and INTRAC.

Corporate governance

ICAI’s commissioners, who lead the selection process for all reviews as well as leading the work on each review, were appointed after a recruitment process regulated by the Commissioner for Public Appointments. They hold quarterly board meetings, the agendas and minutes of which are published on our website.

ICAI’s primary governance objective is to act in line with the mandate agreed with the Secretary of State for International Development, set out in our Framework Agreement with DFID. An updated version of the agreement was signed by the Chief Commissioner and the Secretary of State in September 2019 to cover the period from 2019 to 2023 (ICAI’s Phase 3). The modifications were primarily to clarify and reinforce the fact that ICAI’s remit encompasses all departments and cross-government funds that spend Official Development Assistance (ODA).

The cross-government focus of ICAI’s work is not new – it was included in the UK aid strategy, published in November 2015. This whole-of-government strategy included a commitment to sharpen oversight and monitoring of spending on ODA and emphasised that ICAI is one of the means of conducting this scrutiny and ensuring value for money, irrespective of the spending department.

Risk management

ICAI has a corporate risk register which identifies and monitors ICAI’s corporate risks. This is reported monthly to the ICAI commissioners. Risks relating to individual reviews are monitored and ICAI also monitors supplier risks as part of the monthly contract management meetings.

ICAI’s risk registers include an assessment of gross and net risk, mitigating actions and assigned risk owners. Risk is discussed regularly and is included as a standing item at every board meeting. Commissioners review risks in detail and the risk register is included in formal monthly performance reporting.

New key performance indicators (KPIs)

ICAI’s performance against its existing KPIs is covered in Chapter 5 below. However, it is worth noting that in March 2020 commissioners agreed to adopt a more comprehensive set of KPIs, which align more closely with ICAI’s theory of change, from the beginning of April 2020.

In summary, the revised KPIs will cover:

- the proportion of ICAI recommendations actioned by government

- change in government practice as a result of ICAI reviews

- IDC satisfaction with ICAI

- adequacy of government response assessed at follow-up reviews

- ICAI communications and engagement activity

- media and social media coverage

- budgetary control.

This represents the implementation of the last outstanding recommendation from the 2017 Tailored Review that “ICAI should develop fewer but more meaningful measures of its own performance which incentivise it to maximise the effectiveness of its remit and functions. ICAI should consider soliciting government stakeholder feedback alongside Parliamentary feedback as part of this process, and report annually on the results.” Implementation was deliberately deferred by the previous board of commissioners, who felt that decisions on any substantive changes to the KPIs should be taken by their successors.

Commissioners have decided to review how fit for purpose the new KPIs are in practice in March 2021.

Annual audit

As part of the Framework Agreement, ICAI is subject to annual audit, undertaken by DFID’s Internal Audit Department, to provide assurance to ICAI and DFID on the effectiveness of the systems and processes in place to manage risk and deliver objectives.

This year’s audit, which had not reported at the time of writing, is examining how ICAI:

- achieves its strategic objectives through the delivery of reviews (in other words, how effectively our reviews support our theory of change)

- ensures quality of its reviews through quality assurance processes and oversight of its supplier

- reports against its work plan, including the agreement and reporting of its KPIs

- embeds risk in its approach to delivery, performance and quality assurance to achieve its strategic objectives.

Conflict of interest

ICAI takes conflicts of interest, both actual and perceived, extremely seriously. Our independence is vital for us to achieve real impact.

Our conflict of interest and gifts and hospitality policies are included on our website. We update the commissioners’ conflict of interests register every six months. We maintain an internal register for secretariat staff and review potential conflicts of interest for all supplier team members before beginning work on reviews.

Any conflict of interest is managed in a transparent way and decisions are taken on a case-by-case basis. The specialist nature of our work, and the requirement for strong technical input, means that we need to weigh the risk of a possible or perceived conflict with the need to ensure high-quality and knowledgeable teams conduct our reviews.

ICAI’s implementation of its conflict of interest policy was reviewed in 2019 by DFID’s Internal Audit Department. The report found that, in general, ICAI manages risks in this area well, with a clear process across the secretariat, board of commissioners and external suppliers. However, it recommended an enhanced process for managing potential conflicts after commissioners have left ICAI. ICAI accepted this recommendation and the head of secretariat now writes to commissioners when they step down from ICAI to remind them of their and ICAI’s ongoing responsibilities in this area.

Whistleblowing

ICAI’s capacity to investigate concerns raised by the public is limited, and not part of our formal mandate. Our whistleblowing policy can be found on our website.

In line with the policy, if we receive allegations of misconduct, we offer to put the complainant in contact with the relevant department’s investigations team, if appropriate, or with the National Audit Office’s investigations function.

Safeguarding

ICAI complies with DFID safeguarding and reporting standards. There have been no reports this year under our safeguarding policy.

Financial summary

This chapter sets out:

- the overall financial position of ICAI

- ICAI’s work cycle

- expenditure for the nine-month period July 2019 to March 2020

- spending plans for the forthcoming year.

Overall financial position

ICAI has a budget of £15.077 million for the four-year period 2019-2023. In the first nine months of this period ICAI spent £2.488 million. The budget for the 2020-2021 financial year is £3.8 million. The work plan for 2020-2021 has been developed but is being kept under review as the COVID-19 crisis develops.

ICAI’s work cycle

ICAI’s pipeline is designed to achieve its mandate of delivering a small number of well-prioritised, well-evidenced, credible thematic reviews on strategic issues faced by the UK government’s aid spending. This means managing a rolling programme of reviews. On average, full ICAI reviews take around nine to 12 months to complete and the shorter rapid reviews take around six months to complete. Even information notes normally take between two and five months to complete. Consequently, costs payable to the supplier in any one financial year cover both products published in that year and initiation costs for reports due to be published the following year.

Expenditure from July 2019 to March 2020

Table 2 provides a breakdown of expenditure for the first nine months of ICAI Phase 3.

Table 2: ICAI expenditure July 2019 to March 2020

| Area of spend | Actual expenditure July 2019 to March 2020 (£k) |

|---|---|

| Supplier costs | 1769 |

| External engagement activities | 25 |

| Total programme spending | 1794 |

| Commissioner honoraria | 157 |

| Commissioner expenses | 1 |

| Commissioner country visit travel, accommodation and subsistence | 14 |

| FLD (front line delivery) secretariat staff costs | 222 |

| FLD staff expenses | 2 |

| FLD staff training | 2 |

| Total FLD spending | 398 |

| Admin secretariat staff costs | 255 |

| Admin secretariat training | 3 |

| ICAI accommodation and office costs | 38 |

| Total administrative spending | 296 |

| Total | 2488 |

ICAI spends most of its money on supplier costs. In 2019-2020, the costs of the supplier in the production of reviews (programme spend) was £1.769 million. This included the cost of reviews, project management of the review portfolio and some inception costs associated with developing new methods for Phase 3.

As explained above, some of this cost is for initiating work on reviews to be published after 1 April 2020 and into Year 2 of Phase 3 to maintain the pipeline of review production. The payments made to the supplier for each review actually published between July 2019 and March 2020 are set out in Table 3 below.

ICAI’s administration budget will continue to be carefully managed to ensure that all expenditure contributes directly to meeting ICAI’s objectives. The scope of ICAI work is expanding as an increasing percentage of ODA is spent by departments and funds other than DFID. However, in keeping with the Tailored Review recommendation in 2017, ICAI will continue to seek further efficiency savings on relevant administration costs.

Table 3: Supplier costs for reviews published in 2019-2020

| Review | |

|---|---|

| How UK aid learns | £157,102 ** |

| Mutual prosperity information note | £100,333 ** |

| Anti-corruption information note | £99,526 ** |

| Preventing sexual violence in conflict and sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers* | £342,920 |

| UK aid to Ghana | £393,824 ** |

*Publication of the second part of this review, Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by Peacekeepers, is pending.

**These figures include the costs attached to IDC hearings which we expect to take place in 2020-2021.

An additional £4459 was spent on scoping a review focusing on ratios of staff costs to expenditure in the context of the Government’s Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR), which was not taken forward once the CSR was scaled back.

The variation in the costs of ICAI reviews is driven by:

- the breadth of the topic under review

- the methodological approach required to provide robust, credible scrutiny of the topic (including whether and how many country visits may be required).

Where relevant, ICAI reviews entail country visits. Commissioners visited four countries as part of the evidence gathering process between July 2019 and March 2020. Secretariat staff did not join any country visits during this period.

Spending plans for 2020-2021

During 2020-2021 we plan to continue with our published work plan and we anticipate spending approximately £3.8 million between April 2020 and March 2021. COVID-19 is causing significant disruption in the first quarter of 2020-2021, because of departments’ lack of capacity to complete fact checks and other input to reviews, and disruption may continue to some extent for some time. ICAI will continue to monitor and revise spending forecasts as the year progresses.

ICAI's performance

This chapter sets out performance during the year against the previous KPIs:

- overall number and type of reviews published

- levels of media/public engagement with our work

- performance against budget.

Table 4: Performance summary

| Key performance indicators | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Publication | 3 reviews, 2 information notes, 1 annual report |

| External engagement events | Commissioners led 14 external engagement events |

| Finance | ICAI operated within authorised budget |

The government has six weeks to publish a response to an ICAI review. By the end of March 2020, we had received responses from the government for three of our reviews published in 2019-2020. The government does not formally respond to information notes. To date, all of ICAI’s recommendations this year have been accepted or partially accepted by the government.

Finances

ICAI continues to deliver within budget. Overall, in the financial year 2019-2020, ICAI remained within its budget by operating with tight financial controls over key areas of spend. ICAI continues to scrutinise all areas of its expenditure to drive further improvements in its operational efficiency.

Working with the International Development Committee

ICAI works closely with the International Development Committee (IDC) to ensure effective scrutiny of UK aid.

This year has seen substantial changes to the membership of the IDC following the December 2019 general election, including the election of a new chair, Sarah Champion MP, and the appointment of Theo Clarke MP as chair of the dedicated ICAI sub-committee

ICAI supports the work of the committee by sharing its review findings, carrying out discrete pieces of work to support the committee’s own inquiries, and agreeing its work plan with members. During the year, ICAI witnesses gave evidence to two IDC hearings – the first on the committee’s report on UK aid for combating climate change and our International Climate Finance review, and the second to support the committee’s Effectiveness of UK Aid inquiry in March, for which ICAI has provided further written evidence. In the same month, ICAI published its information note on anti-corruption and illicit financial flows, which was originally commissioned by the committee in 2019 to inform its inquiry into Sustainable Development Goal 16.

ICAI continues to seek further opportunities to support Parliament in its scrutiny of government, both through ongoing engagement with the IDC and with other committees relevant to ICAI’s work – for example, the Foreign Affairs Committee.

External engagement

ICAI’s stakeholders – government, Parliament, the aid sector and the general public – all have an important role to play in our scrutiny and accountability process, and in helping achieve maximum impact for reviews. Effective engagement with these groups is therefore a strategic priority for ICAI.

Despite the turbulent external and political landscape – including the 2019 general election and the global pandemic – throughout the year ICAI has nonetheless strengthened its engagement processes, delivering an unprecedented number of events, visits and speeches for the period and achieving coverage across national, sector and social media.

Following feedback from stakeholders, ICAI is taking a progressively proactive approach to external engagement. Stakeholders are increasingly consulted at the early stages of reviews in order to help shape their design and direction, and they continue to be engaged as reviews progress through to publication. The team has also adopted new and more accessible ways of communicating with media and the general public, for example through providing video summaries of reviews on ICAI’s social media channels.

Public consultation

In order to identify priorities and shape ICAI’s work for the current commission, ICAI carried out a public consultation in spring 2019. More than 100 stakeholders and members of the public responded, and the findings were published in October. In August, a separate, unpublished piece of work to examine ICAI’s impact, involving interviews with government and non-government stakeholders, also provided ICAI with insight on what was being done well and how its ways of working could be improved.

The combined feedback from both exercises helped enable improvements, including:

- Introducing new country portfolio reviews, looking at all UK aid spend within a country. The first of these, on Ghana, was published in February.

- Making more use of information notes – short, factual reports that do not reach evaluative conclusions on specific programmes – such as on the UK’s evolving mutual prosperity agenda, or on UK aid’s approach to tackling corruption.

- Scoring the annual ICAI follow-up review in order to give a clearer indication of government progress against ICAI’s recommendations.

- Publishing ICAI’s literature reviews in order to contribute to the body of public evidence around a subject.

Respondents to the public consultation also asked ICAI to continue to broaden its focus beyond aid spent by DFID, and to provide more scrutiny of multilaterals. This will be reflected in a number of forthcoming ICAI reviews, such as those on modern slavery, climate change and deforestation, and DFID’s support to the African Development Bank. ICAI continues to welcome stakeholder feedback as its work plan develops.

Events

Events are a key way in which ICAI can raise its profile and present its findings to a wide audience.

In July, ICAI joined forces with the Institute for Government for the first time for an event on What can the aid watchdog tell us about spending public money well? Tamsyn Barton was joined on the panel by the then chair of the ICAI sub-committee, Paul Scully MP, the then permanent secretary of DFID, Matthew Rycroft, and Institute for Government senior fellow Martin Wheatley to discuss ICAI’s previous work and future plans.

ICAI hosted another successful event in January, based on its information note The use of UK aid to enhance mutual prosperity. The report, which provided a snapshot of the UK’s emerging approach to the mutual prosperity agenda, found that the concept was becoming increasingly prominent in government documents, creating the need for a clearer set of rules across departments. The event was an opportunity for experts from across the aid community, academia and Whitehall to discuss the issues, risks and opportunities of the government’s approach.

After publication of each review, ICAI works with government, civil society organisations and the private sector to organise ‘learning events’ for those working in the subject area. Between July 2019 and March 2020, five learning events were held, including sessions on How UK aid learns, the country portfolio review of The changing nature of UK aid in Ghana, and The current state of UK aid.

Commissioners also participated in an unprecedented number of speaking engagements during this nine-month period, including presenting ICAI’s work to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly’s Annual Session in London, delivering a keynote speech at an ODA compliance conference at the University of Cambridge, and speaking at Devex’s Future of Development Finance event, Inside Government’s International Development Conference, and the Seoul ODA International Conference, among others.

Media and digital

Media coverage is an important way in which ICAI can hold government to account, and ICAI’s reviews have continued to generate interest throughout the year. In January, the publication of the review into the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative resulted in 24 pieces of media coverage, including prominent pieces in the Times, the Guardian, Channel 4 News and BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour.

Other reviews to have received coverage include the information note on mutual prosperity, the Ghana country portfolio review, and the How UK aid learns review. In total, over the year, ICAI reviews and announcements generated 85 pieces of media coverage.

Social media continues to be a significant engagement channel for ICAI, with more than 6,200 followers on Twitter, an increase of over 8% from the previous year, and a growing professional audience on LinkedIn. ICAI is increasingly working with stakeholders to seek their support in amplifying messaging on social media channels, resulting in more engagement and impact for reviews.

An innovation this year is the launch of a bi-monthly newsletter to update ICAI’s subscribers (who sign up via the ICAI website) on ongoing work. Newsletters are also issued to subscribers on publication of each review.

ICAI’s website also continues to perform strongly, with 3,035 unique downloads of reviews published since July 2019. This reflects the shorter timeframe covered by this report. Work is underway to optimise the website further.

ICAI’s work plan April 2020 to March 2021

ICAI’s current work plan for April 2020 to March 2021 is updated throughout the year and is available on our website. Although the COVID-19 pandemic is having a considerable impact on how we work, ICAI continues to scrutinise UK aid programmes during this period, in line with our mandate and at a time when monitoring public spending is as important as ever. However, we keep our work plan under constant review, working with Parliament, the departments we scrutinise, and other stakeholders as necessary. We are also adapting our research methods to allow for remote working approaches, following official advice at all times. The safety of all those involved in ICAI reviews is our highest priority.