ICAI follow-up review of 2017-18 reports

Letter from the chief commissioner

Within 12 months of the publication of each ICAI review, we conduct a follow-up review, to assess the government’s response to our recommendations. This follow-up is a crucial aspect of ICAI’s work, ensuring a chain of accountability from findings to remedial actions, and encouraging transparency around the delivery and value for money of UK aid. This year the follow-up review has been complemented by a separate review synthesising the findings from each of the 28 reviews issued in the four-year review period from 2015 to 2019. Together, these two reviews provide a comprehensive picture of the current state of UK aid. The follow-up process is often one of the most rewarding parts of our work as commissioners, when we see how our reviews have helped to catalyse a shift in performance or impact. It also provides a window for aid-spending departments to showcase new initiatives and improvements in UK aid. Again, this year, we report on many areas of progress and improvement, though there are also aspects where more work is required. The follow-up review is also an opportunity for dialogue between ICAI and aid-spending departments on how best to achieve desired changes – a dialogue that also feeds into ICAI’s own learning on how best to target our recommendations to have the greatest impact. This follow-up review marks the transition to the next phase of ICAI. With it we say goodbye to retiring commissioners Tina Fahm and Richard Gledhill, and to former chief commissioner Alison Evans, who left ICAI to take over the Independent Evaluation Group in the World Bank Group in December last year, and we welcome two new commissioners, Sir Hugh Bayley and Tarek Rouchdy. ICAI’s important work of independent scrutiny, through well-targeted, evidence-based reviews and systematic follow-up continues.

Tamsyn Barton

Chief commissioner

Executive Summary

This review follows up on progress made by aid-spending government departments and funds on addressing recommendations from the eight reviews we published between September 2017 and June 2018. It also revisits four issues identified as outstanding from last year’s follow-up review.

Table 1: List of Year 7 reviews and outstanding issues from earlier years covered by this followup review

| Follow-ups | |

|---|---|

| Global Challenges Research Fund | September 2017 |

| The UK aid response to global health threats | January 2018 |

| DFID’s approach to value for money in programme and portfolio management | February 2018 |

| Building resilience to natural disasters | February 2018 |

| The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund’s aid spending | March 2018 |

| DFID’s approach to disability in development | May 2018 |

| The UK’s humanitarian support to Syria | May 2018 |

| DFID’s governance work in Nepal and Uganda | June 2018 |

| Outstanding issues | |

|---|---|

| When aid relationships change: DFID’s approach to managing exit and transition in its development partnerships | November 2016 |

| The cross-government Prosperity Fund | February 2017 |

| The UK’s aid response to irregular migration in the central Mediterranean | March 2017 |

| DFID’s approach to supporting inclusive growth in Africa | June 2017 |

There has been good progress across ICAI’s 2017-18 recommendations

While the level of progress made varied, the response of the relevant government departments to the eight reviews followed up in this report was generally strong, considered and appropriate. The report highlights a range of positive actions, leading to good progress in a number of areas of UK aid, including on strategic direction, theories of change and results management, research, analysis and diagnostic work, and the mainstreaming of cross-cutting issues such as disability and disaster resilience. Some improvements which stand out include:

- The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund’s efforts to strengthen theories of change and results frameworks. Together with the scaling up of monitoring, evaluation and learning activities, these are likely to improve both the design and the implementation of the Fund’s programmes.

- DFID’s ambitious strategic framework for mainstreaming disability inclusion in all its programming.

- Significant achievement by the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) in the span of a year in developing strategic themes, setting up research hubs and appointing challenge leaders. This is highly likely to improve the coherence of the Fund’s investments and the potential for development impact at scale.

- The range of efforts by DFID, the Department of Health and Social Care and other government bodies to improve coordination and collaboration on tackling global health threats.

In many cases we can relate these improvements directly to ICAI’s findings and recommendations. It is rarely the case, though, that progress is only attributable to ICAI’s reviews, especially when other significant learning processes such as DFID’s Country Development Diagnostics work are taking place at the same time. Often ICAI’s recommendations have their strongest influence when they inform and encourage departmental initiatives and reforms that are already under way.

Cross-cutting themes

This follow-up process has highlighted issues of strategic importance to UK aid spending that cut across many of our 2017-18 reviews. We will continue to monitor these in ongoing and future reviews:

- Do no harm: Several of this year’s follow-up exercises show improvements in how UK aid actors adhere to the principle of ‘do no harm’.

- The changing profile of UK aid: Dual-purpose funds, combining development and national interest goals, now spend a significant amount of UK aid. From a low starting point, these have made strong progress in developing systems and processes to ensure value for money and compliance with official development assistance (ODA) rules.

- From targets to transformative change: After a period characterised by targets-based programming, there is now an increased focus on transformative results in DFID’s programming, such as promoting economic transformation and building equitable and sustainable public services to help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

Outstanding issues

There are nevertheless areas of strategic significance where further follow-up next year will be beneficial. This year we identified three reviews for further follow-up:

- Governance: This was ICAI’s last review in the 2017-18 review cycle, with the least time available for DFID to respond to the recommendations. We found that most actions were at too early a stage for us to judge their appropriateness, so we plan to return to all this review’s recommendations in next year’s follow-up exercise.

- The GCRF: We saw significant improvements in many areas but would like to return to four issues:

- Given the very devolved structure of the GCRF, we would like to look again at how the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) ensures overall accountability for the Fund.

- We would like to revisit the block grants forwarded to the devolved funding councils via the GCRF. There have been clear improvements in the monitoring of ODA compliance since our review, but it is too early to tell how far the measures taken will align the funding councils’ GCRF expenditure with the Fund’s strategic objectives and ensure value for money. We also want to look again at how BEIS monitors and ensures accountability for how these block grants are spent.

- The newly created research hubs are a promising innovation and we would like to follow up on how they contribute to the potential development impact of the GCRF.

- We will also look at the effectiveness of the new cross-government Strategic Coherence for ODA-Funded Research Board in influencing the allocation and delivery of UK ODA funds for research and innovation over time.

- Irregular migration: Overall, we found good progress on the outstanding issues we raised in last year’s follow-up. However, DFID has decided not go ahead with plans for an independent evaluation of its flagship migration-related programme, the SSS II, relying instead on alternative arrangements for monitoring, rapid research and learning. Because this happened subsequent to our follow up assessment, we plan to review these revised arrangements as part of next year’s follow-up.

Introduction

ICAI provides robust, independent scrutiny of the UK’s ODA to assist the government in improving the effectiveness and impact of its interventions and to assure taxpayers of the value for money of UK aid spending. Our main vehicle for this scrutiny is the publication of reviews on a broad range of topics of central concern to the UK’s aid strategy. A crucial part of these evaluations is our annual follow-up process, where each year we return to the recommendations from the previous year’s reviews to see how well they have been received and acted upon by the relevant government department or public body.

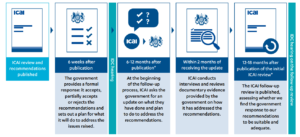

The follow-up process is structured around the recommendations provided in each ICAI review (see Figure 1 for an illustration of the process). The government has six weeks to provide a formal response to ICAI reviews, where it sets out whether it accepts, partially accepts or rejects ICAI’s recommendations and provides a plan for how it will address the issues raised. This is followed by a hearing in the ICAI sub-committee of the International Development Committee (IDC). Then, between six and 12 months after the publication of the original review (the amount of time depends on how early in ICAI’s annual review cycle the relevant report was published), ICAI conducts a formal follow-up exercise. The aid-spending departments are asked to provide an update on what they have done, and what they plan to do but have not yet implemented, in response to ICAI’s recommendations. Based on this response, supported by documentary evidence and interviews, we investigate the extent to which the government has done what it promised to do and – also considering any additional relevant actions – determine whether we find this to be a suitable and adequate response to the original recommendation. After publication of the follow-up review, there is an IDC hearing on its findings.

Figure 1: Timeline of ICAI’s annual follow-up process

*We conduct our follow-up assessment on an annual basis, starting in January and publishing in the summer. The follow-up covers a number of reviews which are selected according to their publication date (if a review is only published a few months before the follow-up process then it will be covered in the following year). If we are not satisfied with the government’s progress on any of our recommendations, we then follow up on those areas again during the next year’s assessment.

This report presents the results of the annual follow-up exercise for 2017-18 reviews. It provides a record for the IDC and the public of how well the UK government has responded to ICAI recommendations and findings. The follow-up process is also an opportunity for additional interaction between ICAI and responsible staff in DFID and other government departments, offering feedback and learning opportunities for both parties. The follow-up process is a central part of our work to ensure maximum impact from our reviews.

ICAI published eight reviews in 2017-18 and all 43 recommendations made in these reviews were accepted or partially accepted. This report contains an analysis of three important themes that cut across many of the reviews being followed up this year, together with a series of tables summarising our assessment of progress on the recommendations in these reviews, and on four areas of concern that were outstanding from last year’s follow-up exercise. We also include a brief explanation of our follow-up methodology.

A more detailed narrative account of ICAI’s recommendations and the government’s response and actions is provided in an annex to this report. This narrative is also available on the ICAI website, alongside the relevant reports and government responses.

Methodology

When we follow up on the findings and recommendations of our past reviews, we focus on four aspects of the government response:

- Whether the actions proposed in the government response are likely to address the recommendations.

- Progress on implementing the actions set out in the government response, as well as other actions relevant to the recommendations.

- The quality of the work undertaken and how likely it is to be effective in addressing the concerns raised in the review.

- The reasons why any recommendations were only partially accepted none of the 2017-18 recommendations were rejected).

We begin by asking the relevant government department to prepare a brief note, accompanied by documentary evidence, summarising the actions taken to implement the response to our recommendations. We then check that account through interviews with the responsible staff, both centrally and in country offices, and by examining relevant documentation. Where necessary or useful, we also interview external stakeholders, including other UK government departments, multilateral partners and implementers. To ensure we maintain sight of broader developments, we also assess whether ICAI’s findings and analyses have been influential beyond the specific issues raised in the recommendations.

The follow-up process for each review concludes with a formal meeting between a commissioner and the senior civil service counterpart in the responsible department.

At the end of the follow-up process, we identify issues of continuing strategic importance where we judge the action taken by the department in question to have been inadequate or incomplete. These issues are flagged for further follow-up the following year.

We also use the follow-up review as a learning opportunity for ICAI, about the impact of our reviews on UK aid and how we communicate our findings and recommendations in order to achieve maximum traction with the government.

Box 1: Limitations to our methodology

Assessing the impact of ICAI recommendations is not straightforward. UK aid programming is not static, with new policies and strategies launched every year. Often our recommendations concern areas of activity already undergoing important changes, and sometimes an ICAI review is only one among several reports highlighting similar issues or making similar recommendations. Attributing particular reforms or policy changes directly to ICAI reviews is therefore not always possible. Instead, we consider relevant changes that have occurred since our reviews, where it is plausible that ICAI has contributed to the thinking or influenced the action taken.

Cross-cutting themes

During the course of our follow-up exercise, we noted three themes of strategic importance that recurred across several of the 2017-18 reviews and remain relevant in our current review programme.

Do no harm

‘Do no harm’ is a key principle of good development practice, particularly in fragile or conflictaffected settings. It commits aid actors to avoiding causing inadvertent harm to vulnerable individuals and groups, and to considering the risk of harm and how it can be mitigated in the design and implementation of aid programmes.

If risks cannot be sufficiently mitigated, then programmes should not be launched. For instance, after conducting a risk analysis, DFID decided not to implement certain projects aimed at vulnerable irregular migrants in Libya due to the many risks involved in providing material assistance in an environment of human rights abuses, kidnappings, slavery and extortion practices perpetrated against migrants in the country’s migrant detention centres.

Risks should be monitored during the lifetime of programmes, as changing circumstances – especially in volatile conflict zones – can throw up risks that were unforeseen in a programme’s design phase.

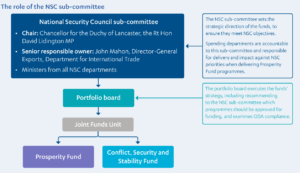

The principle of doing no harm will continue to be central to the UK aid strategy, as the ideas from the Fusion Doctrine on national security, presented in the March 2018 National Security Capability Review, begin to inform aid programming. UK aid is an important link in the chain of political, economic and influencing activities which support the government’s national security objectives (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: The objectives and tools of the Fusion Doctrine

Principle:To deploy security, economic and influence capabilities to protect, promote and project our national security, economic and influence goals.

In a speech in Cape Town in August 2018, Prime Minister Theresa May described how UK aid would contribute to the joined-up way of working set out in the National Security Capability Review and outlined a series of new strategic objectives for the UK aid programme. In addition to reaffirming long-standing UK aid commitments to humanitarian relief, empowering women and girls, and tackling climate change, she set out four thematic priorities for UK aid:

- addressing the root causes of conflict and fragility

- tackling cross-border threats

- promoting the rules-based international order

- building markets in frontier economies.

She also announced a new geographical focus, including on the Sahel region of Africa and the new ‘frontier markets’ such as Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal.

This prioritisation of tackling threats, fragility and conflict makes it crucial that all departments and funds that deliver UK aid have the necessary knowledge, skills and procedures in place to assess and mitigate against the risk of doing harm to vulnerable individuals. This entails careful analysis of the drivers of conflict and human rights risks, and the design and implementation of sophisticated theories of change and strategies for mitigating the risk of harm.

“These new priorities will represent a fundamental strategic shift in the way we use our aid programme, putting development at the heart of our international agenda – not only protecting and supporting the most vulnerable people but bolstering states under threat, shaping a global economy that works for everyone, and building co-operation across the world in support of the rules-based system.”

Prime Minister’s speech in Cape Town, 28 August 2018

This year’s follow-up exercise found significant improvements in how UK aid actors adhere to the principle of doing no harm:

- The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) has made considerable progress towards strengthening its ‘do no harm’ approach, elevating it from a threshold compliance question to be considered at programme design to a more broad-based and substantial endeavour to place conflict sensitivity and human rights risk management at the heart of its programming.

- Both DFID’s and the CSSF’s irregular migration-related programming in the central Mediterranean now includes more stringent risk analysis of how vulnerable migrants will be affected before programmes are rolled out, based on improved theories of change and research on what works. We would, however, have liked to see the risk of harm incorporated more explicitly in these programmes’ monitoring and evaluation approaches. Disability in development: DFID’s new Disability Inclusion Strategy has stigma and discrimination against people with disabilities as one of three cross-cutting areas “which will be consistently and systematically addressed in all of [its] work”. While this is primarily an issue of inclusive development, attention to stigma and the effects of aid interventions on people with disabilities will also contribute to avoiding harmful unintentional effects of aid interventions.

- Inclusive growth: With the development of new diagnostic tools, new programming and the Inclusive Data Charter: Action Plan, DFID has put in place a strong and credible approach to counteract trends in many partner countries of excluding women, young people and marginalised groups from the benefits of aid programmes. This is primarily about inclusion rather than ‘do no harm’, but more thorough diagnostic work on how and why individuals and groups become excluded will also help DFID ensure that its own aid programming is not inadvertently supporting harmful exclusion practices.

The changing profile of UK aid

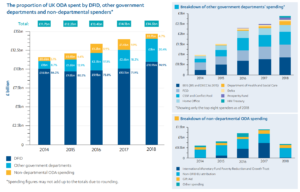

The UK continues to be one of the few countries to spend 0.7% of its gross national income on ODA. In 2018, this amounted to more than £14.5 billion, an increase of £487 million or 3.5% from 2017. DFID is no longer the only UK government department spending significant amounts of ODA. More than 25% of all UK aid in 2018 was accounted for by other government departments and by non-departmental expenditure (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3: Growth in UK ODA spending outside of DFID from 2014 to 2018

The proportion of UK ODA spent by DFID, other government departments and non-departmental spenders

Dual-purpose funds, combining development and national interest goals, now spend a significant amount of UK aid.

Our review of the Prosperity Fund in February 2017 was the first of a series of reviews of major aid funds managed by departments other than DFID. This was followed by reviews of the GCRF, the CSSF and, most recently, the Newton Fund. In all of these reviews, ICAI found serious shortcomings, including:

- unclear governance and accountability structures

- lack of fund-level strategies, including clarity on primary and secondary objectives

- inadequate monitoring, evaluation and learning arrangements scaling up expenditure too quickly, before robust programme designs and management processes were in place

- in the case of the Prosperity Fund, the GCRF (regarding its original approach to block grants to the devolved funding councils) and the Newton Fund, pushing the boundaries of ODA eligibility.

The GCRF, the CSSF and the Prosperity Fund have responded well to the concerns raised by ICAI. The follow-up review found that these funds had made considerable progress in putting in place the necessary systems and processes to ensure value for money and compliance with ODA rules. In particular:

- The Prosperity Fund decided to delay allocations in order to develop a fund-level strategy, a theory of change with key performance indicators, a monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning strategy and a procurement framework.

- The CSSF has made significant progress in instituting good aid practice in fragile and conflict-affected areas, including investments in thorough conflict sensitivity analysis and ‘do no harm’ risk assessments, results management, transparency and ODA compliance.

- The delivery partners have developed a strong strategy for their GCRF portfolios, paying much closer attention to achieving development impact, particularly through the development of research hubs and priority research areas and the appointment of challenge leaders.

However, challenges and risks remain, some of which are legacies of the lack of strategic direction and ODA management structures and processes when the funds were first launched:

- Value for money risks around rapid scale-up: While we are very pleased that the funds are now putting strategies and better management processes in place, in some cases this was only after much of their budget had been allocated. This damage was mitigated in the Prosperity Fund by the postponement of its first allocation round. However, in the case of the GCRF, it was only after around £1.3 billion of the total fund of £1.5 billion had been allocated to delivery partners that priority research areas were announced and the research hubs established.

- Learning within and across funds could be improved, particularly on ODA oversight: The GCRF’s improvements since the original ICAI review have been driven by delivery partners, not by BEIS, and cross-learning from the GCRF to the Newton Fund has been insufficient, despite similar concerns about oversight arrangements and the value for money of aid spending having been raised previously.

- Improvements are at an early stage: With each of the three funds covered by this year’s followup, new governance structures, strategic directions, monitoring and evaluation arrangements and other procedures for ensuring aid effectiveness and value for money have only recently been put in place, so it is too early to assess how they have been implemented and whether they will lead to stronger programming.

ICAI has contributed to driving the progress of these funds in developing more robust structures and procedures. The next stage of scrutiny should be on how these will translate into higher-quality programming and better value for money. These funds and other cross-government aid programmes will therefore continue to be an important focus for ICAI.

From target-based to transformative results

Between 2010 and 2015, the UK government set ambitious global results targets for the UK aid programme, with country offices accountable for demonstrating their contribution to these targets. Over a number of reports, ICAI raised concerns that the targets created pressures on programmes to maximise beneficiary numbers, without proper regard to the quality, equity or sustainability of the results.

In last year’s ICAI review of DFID’s approach to value for money (which we follow up on this year), we noted that a results management system which focused on output targets would measure the direct returns on individual aid investment, but might miss out on measuring and reporting on results at the country portfolio level. Such an approach risked focusing attention on the efficiency of delivery, rather than on whether the programme was likely to achieve the intended results.

A target-based results management system makes it difficult for DFID, ICAI or the general public to assess the aid programme’s contribution to transformative change – in other words how UK aid programmes combine to contribute to broader development efforts at the country level, such as the Sustainable Development Goals, or cross-cutting objectives like resilience, disability and inclusive development.

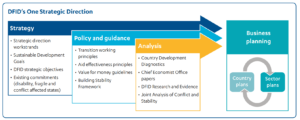

There are now some positive signs that DFID is moving towards a greater focus on transformative results, such as promoting economic transformation and building equitable and sustainable public services. In this year’s follow-up exercises, evidence we have seen of measures to strengthen transformative results includes:

- stronger emphasis on flexible, adaptive programming

- the introduction of a new diagnostic tool, the Country Development Diagnostics process, into the business planning process to help tailor programming to the needs of each partner country

- an emerging focus on managing results at the country and sector portfolio level.

DFID’s move towards transformative results is still a work in progress. There are key technical challenges that must be surmounted for this transition from a target-based to a transformational results approach to be successful. Chief among these is the considerable challenge of finding ways of reporting results that move from attribution of results at programme level to contribution analysis at portfolio level, while still maintaining rigour and accuracy. DFID has been consulting internally on how best to measure and report on transformative results, but no standard practice has yet emerged.

Summary of findings from individual follow-ups

This section provides a short summary of the main findings of our follow-up on recommendations for eight ICAI reviews and four outstanding issues from previous follow-ups. A fuller narrative account of trends, improvements and gaps for each of the reviews is provided as an annex at the end of this report.

The Global Challenges Research Fund

Since the publication of the ICAI review in September 2017, progress has been made in all four areas covered by our recommendations, often led by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), the GCRF’s main delivery partner. We remain concerned that BEIS is providing insufficient oversight of the Fund, particularly over the block funding allocations to the four devolved funding councils. Mechanisms to ensure ODA compliance and value for money can still be improved.

| Subject of recommendation | Recent developments | ICAI's assessment of progress |

|---|---|---|

| Formulate a more deliberate strategy to encourage concentration on highpriority development challenges. Government response: Partially accepted | • Introduction of six thematically distinct GCRF portfolios on global health, food systems, conflict, resilience, education and sustainable cities. • 12 interdisciplinary research hubs established under the aegis of UKRI. • Nine senior academics appointed as challenge leaders. • A new BEIS Portfolio & Operations Management Board, including oversight of programme-level portfolios. | • The thematic portfolios, research hubs and challenge leaders are a strong response to this recommendation. Together they strengthen the chances that the last unallocated portion of the GCRF’s budget will be spent in a more targeted, strategic manner. • Strategic oversight of the GCRF remains very devolved from BEIS to the delivery partners, especially UKRI, which poses an accountability risk. • The devolved funding councils have improved their monitoring of ODA compliance, but it is too early to tell if the recently introduced measures will lead to a stronger strategic alignment between the block grants and the GCRF’s priority research themes. |

| Develop clearer priorities and approaches to partnering with research institutions in the Global South. Government response: Accepted | UKRI has led a series of global engagement events to inform potential research collaborators in partner countries about funding and collaboration opportunities. • Partners from the Global South are included in each research hub. • South-based principal investigators can now lead some GCRF projects. • UKRI has set up an international development peer review college, which will contribute to assessing proposals. | • There is progress towards more equitable partnerships with researchers and institutions in the Global South. • The international development peer review college, with 95% of its membership drawn from developing countries, is likely to improve the development relevance, equity and strategic coherence of portfolios. |

| Provide a results framework for assessing the overall performance, impact and value for money of the GCRF portfolio. Government response: Accepted | • BEIS has developed a Fund-level theory of change. • A Fund-level evaluation approach is under development, building on this theory of change. The delivery partners also have their own individual evaluation processes. • UKRI is improving reporting procedures to better monitor ODA compliance and capture development impact and value for money of research investments. | • These are important improvements, but they come too late in the GCRF’s programming cycle. • UKRI has plans to review the effectiveness of its policies and practices to ensure ODA compliance, not just at the award stage but during the lifespan of the grant. |

| Develop a standing coordinating body for investment in development research across the UK government. Government response: Accepted | • The Strategic Coherence for ODA-Funded Research (SCOR) Board was established in December 2017 to provide strategic coordination for the UK’s ODAfunded research across government departments. • The SCOR Board is the governance body for the UK Collaborative for Development Research, a government entity that brings together government departments and research funders working in international development. | • The SCOR Board is likely to improve crossgovernment information exchanges, but it is too early to assess what impact it will have. • It is too early to assess the impact SCOR will have on BEIS’s management of the GCRF and its sister fund, the Newton Fund. |

The UK aid response to global health threats

There have been positive developments in response to all four of ICAI’s recommendations. A refreshed strategic framework is under development, which will highlight health systems strengthening work and facilitate wider engagement by adopting the internationally recognised ‘Prevent, Detect, Respond’ terminology. We also saw improvements in cross-government working and learning in support of the high priority that the UK government gives to global health security.

| Subject of recommendation | Recent developments | ICAI's assessment of progress |

|---|---|---|

| Refresh the government’s global health security strategy, with emphasis on health systems, research and mechanisms for collaboration. Government response: Accepted | • The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and DFID are refreshing the strategic framework and are committed to sharing it externally. • The UK has been closely involved in the international response to the outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), building on its experience in Sierra Leone, and is feeding learning from this latest outbreak into its new strategy | • The refreshed framework employs the internationally recognised ‘Prevent, Detect, Respond’ terminology which will facilitate coordination with donors and partner countries and engagement with the private sector • There is a shift towards stronger emphasis on health systems strengthening, in line with ICAI’s recommendation • Important learning is taking place on how to adapt global health threat responses to fragile and conflict-affected settings. |

| Strengthen and formalise crossgovernment partnership and coordination mechanisms, including regular simulations. Government response: Partially accepted | • The government argued that relevant branches already coordinate and collaborate closely. It has nevertheless expanded the membership of the cross-government Global Health Oversight Group (GHOG) to include all relevant government actors. • DFID and Public Health England (PHE) are working more closely together at country level. | • The strengthening of GHOG, together with a range of other cross-government coordination meetings and discussion forums, constitutes a significant improvement. • Cross-government collaboration has been strong during the Ebola outbreak in the DRC. |

| Ensure that DFID has sufficient capacity to coordinate programmes and influencing activities in priority countries. Government response: Accepted | Recruitment is under way for seven new UK government posts focusing on global health security in the Africa region. • PHE is increasing its in-country activities, and DFID and PHE now work closely together in countries where both organisations have a presence. | • The new staff will bring additional capacity to enhance the UK's engagement on global health security within the Africa region. However, the recruitment process has been lengthy. |

| DFID and DHSC should work together to prioritise learning on global health threats across government. Government response: Accepted | • There has been a flurry of learning and evaluation activities. • We do not yet know how learning will be incorporated in the new Prevent, Detect, Respond framework. | • The significant learning and evaluation activities that have taken place since the publication of the ICAI review are a good response to our recommendation. • The new framework and theory of change, once completed, will facilitate cross-departmental coordination and give strategic direction to learning activities. |

DFID’s approach to value for money in programme and portfolio management

There is a currently a wide-ranging process of reflection on business planning and results management systems under way within DFID, including on adaptive programming, diagnostics, portfolio management, portfolio-level results management and business case development. Most of this work remains at the design and development stage. While progress has been fairly slow, we recognise that changes to core business processes necessarily take time. We welcome plans to introduce more emphasis on portfolio-level and transformative outcomes into DFID’s approach to assessing results and value for money.

| Subject of recommendation | Recent developments | ICAI's assessment of progress |

|---|---|---|

| Articulate crosscutting value for money objectives at the country portfolio level. Government response: Partially accepted | • DFID has begun a wide-ranging process of reflection on its results management systems as a whole, with stronger emphasis on transformational results – such as promoting inclusive growth. | • DFID is in the middle of a strategic planning phase ahead of the business planning cycle and the Spending Review, so there has been no concrete action on this recommendation yet. |

| Experiment with different ways of delivering results more cost-effectively, particularly for more complex programming. Government response: Accepted | • DFID is progressing with useful initiatives to promote flexible and adaptive programming, including a LearnAdapt initiative to develop a value for money approach to adaptive programming. | • These are promising initiatives, and the learning on designing adaptive programming is significant. But work remains at a preparatory or planning stage, so it is too early to assess its impact. |

| Ensure that principles of development effectiveness are more explicit in DFID’s value for money approach. Government response: Accepted | • No concrete action. • The UK has slipped from 3 to 12 (out of 27) on the Center for global Development’s Quality of Official Development Assistance index. | • Principles of development effectiveness, such as ensuring partner country leaderships and empowering beneficiaries, are not explicit enough in DFID’s business processes, which opens up risks of deteriorating standards in development cooperation. |

| Be more explicit about – and monitor and reassess – assumptions underlying the economic case for interventions. Government response: Partially accepted | • DFID is revising its annual review process to include a reassessment of the programme’s theory of change and the overall value for money case, including by reference to assumptions set out in the business case. • A new section in the annual review requires an assessment of the logic and assumptions of the theory of change. | • While DFID has opted for a different solution to the one recommended by ICAI, we find the response to be reasonable. The new template and guidance are improving the quality of the annual review process. |

| Annual review scores should assess whether programmes are likely to achieve their intended outcomes in a cost-efficient way. Government response: Partially accepted | • DFID has revised the annual review template to include detailed reconsideration of the theory of change and whether the programme is on track to achieve its intended outcomes. • Changes to logframe targets during programme implementation are now logged. | • Again, DFID opted for a different solution, but we find the rationale for this to be reasonable. DFID has introduced more transparency into the setting of programme targets and a stronger focus on assessing progress towards outcomes in annual reviews. |

Building resilience to natural disasters

There has been a good response to ICAI’s recommendations related to the strengthening and mainstreaming of resilience across DFID programming in high-risk country settings, particularly through its Country Development Diagnostics (CDD) process. The main actions proposed and under way are relevant and useful, but much remains at the preparatory stage. DFID should provide clearer guidance on strengthening measurement of resilience at the portfolio level.

| Subject of recommendation | Recent developments | ICAI's assessment of progress |

|---|---|---|

| In partner countries with significant risks from natural disasters, keep risk assessment and resilience strategies up to date. Government response: Accepted | • DFID has introduced a series of risk management tools and processes to support resilience and preparedness, including as part of its CDD process. • DFID has linked core funding to UN agencies to a set of progress indicators, including on preparedness planning. • Influencing activities through participation in international forums. | • Including these tools and processes in the CDD process is a good way to prompt country offices to consider resilience and risk comprehensively in their diagnostic and planning work. • There is a risk that country offices ignore the CDD prompts. |

| DFID offices in highrisk countries should adopt a portfolio approach to resilience. Government response: Accepted | • The CDD is the main vehicle for change in response to this ecommendation: resilience is one of the CDD’s cross-cutting issues. • Guidance notes to country offices on how to cover resilience were issued at the start of the CDD process. | • This process is ongoing, but there are already signs that it is leading to a better understanding in country offices of the need to address resilience and risks systematically. • We would welcome a follow-up assessment by DFID in due course of whether country offices have in fact implemented the results of this analysis into their portfolios. |

| Develop guidance on how to measure resilience results, providing options that can be adapted by country offices to their contexts and needs. Government response: Partially accepted | • For programmes where resilience is the main objective, DFID is revising its main key performance indicator on resilience. • It is participating in international forums on resilience measurement and using lessons from its Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters (BRACED) programme to develop its approach to monitoring, measurement and evaluation. | • There has been a range of significant actions to improve guidance for programmes where resilience is the main objective. However, there has been little action in the case of programmes where resilience is not the main objective but an important cross-cutting and secondary aim. • The growing use by country offices of specialist monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) units is very likely to improve the capacity to capture secondary resilience outputs and outcomes. |

| Undertake a stocktake of resilience work in high-risk countries to inform country strategies. Government response: Partially accepted | • DFID said it already assesses resilience and preparedness in high-risk countries, as part of internal ‘lessons learned’ reviews in the wake of significant natural disasters and as part of the programme management cycle. • DFID’s resilience contributions have been reviewed in recent evaluations of UK humanitarian responses, such as in South Sudan. | • There have so far been no specific actions in direct response to ICAI’s review, but the recent series of evaluations to ensure that DFID programmes routinely analyse risk and resilience is positive. It is too early to tell if this will be sufficient. |

| Establish a community of practice to promote the mainstreaming of resilience. Government response: Accepted | • DFID was already planning to establish a community of practice on resilience, and has now done so. It is moderated by a staff member, hosts resources and facilitates cross-programme links. It is supported by a ‘one-stop shop’ for learning materials. • A learning strategy is in the process of being developed. | • We are pleased that DFID has now established a community of practice. Its continued success will depend on sufficient resources being allocated to maintain it. |

The Conflict, Stability and Security Fund’s aid spending

The CSSF has made significant efforts to address the shortcomings identified by ICAI. It is possible that the work done to date has already led to more conflict-sensitive programming with clearer and more testable intermediate outcomes. Monitoring is becoming more rigorous as quality standards for programme design have been raised. Learning has been accelerated and there are signs that some important learning mechanisms are starting to become institutionalised.

| Subject of recommendation | Recent developments | ICAI's assessment of progress |

|---|---|---|

| Introduce country or regional plans that specify how CSSF activities will contribute to National Security Council objectives. Government response: Partially accepted | • There has been a step change in the quality of programme-level documentation. The CSSF is now routinely developing theories of change of good quality. • The government did not want to introduce SSF specific country or regional plans, but instead invested in strengthening programme-level theories of change with clearly defined objectives and more transparency around assumptions. | • Annual reviews now report on outcomes, not just outputs. • The improved annual review process is leading to better data collection and can be used to assess whether outcome targets remain adequate or need adaptation as contexts change. |

| When CSSF projects have influencing objectives, make them explicit and report on their progress. Government response: Accepted | • Influencing and diplomatic access outcomes are now presented as explicit and legitimate objectives in programme documentation. • Indicators of influencing and access outcomes are now included in theories of change and annual reviews are now reviewing these. | • This is a strong response. Reasuring the achievement of influencing objectives is difficult, but these measures should make it possible to do so. • Annual reviews are already beginning to reflect critically on how to use flexible, adaptive approaches to easurement in order to capture influencing outcomes. |

| Programmes should demonstrate more clearly and carefully how they identify, manage and mitigate risks of doing harm. Government response: Accepted | • The CSSF has strengthened guidance and training and introduced new processes to identify, manage and mitigate risks of doing harm. • Risks of doing harm are now incorporated in programme risk registers and annual review templates. • A ‘conflict sensitivity marker’ is being refined and piloted. • 70 Overseas Security and Justice Assessments (OSJAs) have been assessed and revised where necessary. | • This is a swift and thorough response, with much stronger mechanisms and processes in place, supported by improved learning material and conflict sensitivity analyses, to assess and mitigate against harm. • The 20 pilot exercises for the conflict sensitivity marker focus on awareness, adaptiveness and accountability, and have been thorough and useful. |

| New programming should include adequate results management and measures to assess value for money. Government response: Accepted | • Given human resource constraints, the CSSF has prioritised getting regional monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) contracts in place. • The strengthening of the CSSF’s programme level theories of change and annual reviews (see above) will also help to improve results management. | • The CSSF has made significant commitments to improving its results management processes, backed up by dedicated funding, staff recruitment, independently contracted expertise and other measures to ensure implementation of MEL initiatives. • The ‘learning-while-doing’ approach adopted by the CSSF will allow it to refine its results management mechanisms as these commitments are transformed into action. |

| Create conditions that allow for the evaluation, by independent evaluators where possible, of a larger part of the CSSF portfolio. Government response: Accepted | • The CSSF has conducted a number of evaluations since the ICAI review and has strengthened the evaluability of its newer programmes through improved theories of change, annual reports and better data gathering and results management mechanisms. • The CSSF currently has a stated practice of only evaluating major programmes with larger budgets. | • These are significant improvements, but the CSSF is still making some unsubstantiated results claims. • The Fund should not focus exclusively on large programmes in its evaluation strategy. As its spending is mostly through many smaller projects, it should also evaluate these on a sample basis. We have been told that the new MEL strategy will seek to take a more strategic approach to evaluation, but we do not yet know if this will include a strategy for evaluating smaller projects. |

| Do more to gather and synthesise evidence and disseminate lessons on what works in important programming areas. Government response: Partially accepted | • The CSSF’s global MEL plans include measures to consolidate Fund-level evidence to improve the understanding of what works in fragile and conflictaffected states. • A stabilisation guide has been issued and other learning exercises are nearing completion, particularly in the field of conflict sensitivity. | • The CSSF has made great strides in its approach to learning. It now has a deliberate strategy to engage more with other donors and its implementing partners to generate and share learning. • The stabilisation guide is a comprehensive update of the 2014 UK Approach to Stabilisation. Systematic reviews of learning and analytical work, such as of the revision of 70 OSJAs, point towards a more rigorous, institutionalised approach to learning. |

DFID’s approach to disability in development

DFID’s new Disability Inclusion Strategy is an important step forward and addresses most of the issues raised in the ICAI review. The minimum standards for all business units are specific and ambitious. Achieving them within the required deadline is likely to call for significantly more resources than currently available to departments – in particular, staff with relevant experience and skills. However, we welcome the momentum that DFID has created around the disability inclusion agenda.

| Subject of recommendation | Recent developments | ICAI's assessment of progress |

|---|---|---|

| Adopt a more visible, systematic and detailed plan for mainstreaming disability inclusion. Government response: Accepted | • DFID has published a comprehensive Disability Inclusion Strategy, with specific and ambitious standards for all business units. Guidance has been provided by the disability team. The standards cover programming, human resourcing, learning, and organisational culture. • All business units are required to achieve the standards by the end of 2019. • A new Disability Inclusion Delivery Board will meet quarterly to monitor progress and DFID will publish an annual assessment of progress against the standards. | • The Disability Inclusion Strategy is a step change compared to the 2015 non-directive Disability Framework and the one-page 2017 disability action plan. • It is too early to know how well the strategy will be implemented, but early signs show strong engagement and commitment. • The strategy’s timeline is very ambitious. The lack of sufficient human and financial resources will make it extremely difficult to meet. |

| Increase the representation of staff with disabilities and increase the number of staff with expertise on disability inclusion. Government response: Accepted | • The Disability Inclusion Strategy includes targets for increasing the proportion of UK-recruited staff with disabilities (currently at 8.7%) to match that of the UK average for the working age population (18%). • The strategy states that DFID “will equip DFID staff with the skills, tools and knowledge to better integrate disability inclusion into all of our policies and programmes”. | • The target for UK-recruited staff is appropriate, but stronger efforts should also be made to increase the number of locally recruited staff with disabilities in DFID country offices overseas (currently only at 2%). • Additional expertise is urgently required to help all business units meet the minimum standards by the end of 2019. |

| Country offices should develop theories of change for disability inclusion and working with national governments. Government response: Partially accepted | • DFID argued against making country-level theories of change mandatory. Instead it has developed a general theory of change for disability inclusion which it encourages country offices to use to develop their mandatory disability action plans. • The ‘inclusion module’ of the Country Development Diagnostics (CDD) asks country offices to consider the situation for people with disabilities in social, political and economic spheres. | • Country-level action plans without countryspecific theories of change can lead to plans being based on general assumptions instead of local knowledge on context-specific needs and opportunities. • The CDD’s inclusion module is likely to help improve the quality of country-level analysis by ensuring that the situation for people with disabilities is comprehensively considered. |

| Engage more with disabled people’s organisations. Government response: Accepted | • The Disability Inclusion Strategy reaffirmed a fundamental principle that people with disabilities are “engaged, consulted, represented and listened to at all levels of decision-making ... and empowered as powerful and active agents of change to challenge discrimination and harmful norms and to hold governments and implementers to account”. • The Strategy commits to sufficient investments in disabled people’s organisations to promote their meaningful engagement and stipulates that business units must consult (at least) annually with disabled people’s organisations on programmes, policy and strategy in a way that builds capacity and involves groups that are sometimes excluded, such as people with psychosocial or intellectual disabilities. | • There has been a strongly positive response to this recommendation. It is too early to assess implementation, but we note that DFID ensured substantial involvement by people with disabilities in the July 2018 Global Disability Summit and that disabled people’s organisations have been brought into the governance structures of two new research programmes on disability inclusion. • Practical issues remain to be tackled, such as the accessibility of DFID offices and onerous contracting requirements, which disabled people’s organisations are often unable to meet due to their limited finances and capacity. • While country offices have improved their engagement with disabled people’s organisations, they have generally not been consulted in the business planning process. |

| Tackle stigma and discrimination. Government response: Partially accepted | • The Disability Inclusion Strategy includes stigma and discrimination as a cross-cutting area to be consistently and systematically addressed. • The Strategy requires all business units by 2023 to be “supporting full participation and leadership of people with disabilities; transforming harmful stereotypes and behaviours; and ensuring policies, structures and resources are in place to counter discrimination”. • There has been considerable activity - particularly on learning and influencing - on psychosocial disabilities, with a staff member dedicated to this issue. | • DFID’s rationale for only partially accepting the recommendation was that it needed to understand the issues better before designing interventions. We think this is unduly cautious, as evidence of what works already exists on how to influence behavioural change. • The improvements in the area of psychosocial disabilities highlight the importance of having dedicated, expert staff to promote DFID’s ambitious Disability Inclusion Strategy. In contrast, little has changed on the issue of intellectual disabilities, which has not benefited from similar human resources. |

| Create a systematic learning programme and community of practice on the experience of mainstreaming disability into DFID programmes. Government response: Accepted | • DFID is creating a community of internal champions on disability inclusion and designing a learning journey on the topic with five monthly sessions planned for about 30 participants. • The Disability Inclusive Development helpdesk is now generally available to assist all business units. | • These are welcome moves, but probably not sufficient to ensure that all business units meet the minimum standards by the end of 2019 |

The UK’s humanitarian support to Syria

Despite the dynamic and challenging operating environment in Syria, DFID has engaged proactively with ICAI’s recommendations, with many positive developments. Looking forward, the design process for the 2020 DFID Syria programme portfolio will be one of the most significant ways in which DFID Syria can ensure that further progress is made. It will be important for DFID to ensure that learning from the past seven years of working in Syria is sustained throughout the planned restructuring and relocation of the team – while at the same time overseeing the uninterrupted delivery of a complex portfolio.

| Subject of recommendation | Recent developments | ICAI's assessment of progress |

|---|---|---|

| As conditions allow, DFID Syria should prioritise livelihoods programming and supporting local markets, to strengthen community self-reliance. Government response: Partially accepted | • Given the evolving and unpredictable nature of the conflict in Syria, DFID is unable to commit to expanding this type of programming for the time being, but is actively exploring ways to deliver more livelihoods programming going forward. • DFID Syria is in the process of designing its 2020 portfolio and will produce a new Livelihoods Strategy in mid-2019. | • We agree with DFID that livelihoods approaches are often not possible due to contextual factors and can only be pursued when conditions allow. • The Livelihoods Strategy, once completed, will help better position DFID Syria to respond to contextual challenges in this sector. |

| Strengthen thirdparty monitoring to provide a higher level of independent verification of aid delivery. Government response: Accepted | • DFID Syria has updated its third-party monitoring methodology. It has reduced the role of implementing partners in selecting site visit locations and introduced in-depth verification visits. It has increased the length of monitoring visits from one to two days and has also piloted three-day monitoring visits. • Although constrained by the context, DFID now conducts monitoring in government-controlled areas. | • There are significant improvements under way in this area, some of which were already planned when ICAI made its recommendation. • Early signs are positive. The changes are likely to produce higher-quality and less biased data for assessing project performance in a difficult setting. |

| Support partners to expand their community consultation and feedback processes and ensure this informs learning and design. Government response: Accepted | • DFID Syria’s response has so far focused on information gathering on current processes. These include a desk-based research project to map beneficiary feedback mechanisms and how these are used in Syria, and an assessment of DFID’s delivery partner’s monitoring and evaluation systems, including beneficiary feedback mechanisms. | • Actions are at the learning and planning stage. • The information gathered is expected to feed into the design of the 2020 portfolio. |

| Identify ways to support the capacity of Syrian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to have more direct roles in humanitarian responses. Government response: Accepted | • There has been little action in response to this recommendation. | • Due diligence requirements are important and necessary to safeguard UK public money from fraud and misuse. Syrian NGOs are unlikely to be able to meet these requirements without concentrated assistance to address capacity gaps and set up sound administrative, financial and quality assurance systems. |

| DFID Syria should develop a dynamic research, learning and dissemination strategy. Government response: Accepted | • The response has been limited to refining the process by which DFID Syria staff propose research pieces. They are now also required to identify plans for dissemination. | • The requirement for the Syria DFID staff to have a dissemination plan for their research projects is a good stop-gap measure, but does not remove the need for an overall learning strategy and established dissemination mechanisms beyond the efforts of individuals. |

| Collect and document lessons and best practices from the Syria response, to inform ongoing and future crisis responses. Government response: Accepted | • The Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department (CHASE) has led the effort to embed lessons from the Syria response into humanitarian policy and practice. | • DFID’s information/data analytics team has introduced a search engine that will allow staff to search more easily for projects and topics. • The new search engine is likely to facilitate the collation of and access to lessons and experience across DFID. |

| In complex crises, plan for a lengthy engagement from an early stage. Government response: Accepted | • DFID has outlined several actions to be taken by CHASE, including synthesising learning from various crises in order to streamline the government’s humanitarian response policy. | • Institutionally, DFID has not yet taken forward the wider lessons on transitioning from a short-term emergency footing to longer-term funding and staffing arrangements for protracted complex crises. • CHASE’s synthesis exercise may lead to a more adaptable approach to emergencies. |

| Build on DFID Syria’s efforts to invest in reporting and data management systems that can be readily adapted to complex humanitarian operations. Government response: Accepted | • DFID Syria continues to share its experience using its Cascade reporting tool for results management. • Working with the Office for National Statistics, DFID’s information management team is exploring options for a common DFID reporting tool. | • DFID does not have a systematic way for country offices involved in complex humanitarian operations to share experiences. • Progress on the reporting tool is slow, largely due to the need to ensure proper electronic information security protocols, particularly when external organisations, such as delivery partners, are involved. |

DFID’s governance work in Nepal and Uganda

This was the last review in the 2017-18 review cycle, leaving little time for DFID to respond. Since many actions are at an early planning stage, ICAI will return to all the recommendations in next year’s followup exercise.

| Subject of recommendation | Recent developments | ICAI's assessment of progress |

|---|---|---|

| A more detailed strategic approach to governance at country level, balancing risks and return across its governance portfolios. Government response: Partially accepted | • DFID argued that a separate country-level governance strategy would not assist with integrating governance across the portfolio since the Country Development Diagnostics process would form the core of all new business plans. • The department has recently published a new governance position paper. • A series of guides will be published to help country offices put this approach into practice. | • The position paper is usefully organised around four ‘shifts’ in its governance work: thinking and working politically, integrating governance for growth, stability and inclusion, confidence in UK values, and keeping DFID at the cutting edge of governance work. • The guides are not yet ready and it is too early to tell what impact the position paper will have on country-level planning. |

| Invest in long-term relationships with key counterparts, while maintaining flexibility to scale individual activities up and down. Government response: Accepted | • At the general level of furthering flexible, adaptive programming, there has been a range of actions. • For instance, DFID is developing guidance on adaptive programming (see the discussion of LearnAdapt in the follow-up of the value for money review above). | • There are significant improvements in DFID’s work on designing and monitoring adaptive programming. • There has been little specific action addressing ICAI’s recommendation, including on issues such as how to recognise and reward staff who spend time investing in long-term relationships with national counterparts. |

| Rebalance how governance advisers spend their time. Government response: Accepted | • Both country offices we reviewed made changes in response to this recommendation. For instance, in Uganda the governance team now has a dedicated programme manager to give the team more time for core technical tasks and advocacy work. | • The response to this recommendation has been good within the two country offices reviewed. • At the central level, efforts are under way to learn lessons from the use of more in-depth advisory posts. We will see whether this has resulted in changes to guidance or practice in next year’s follow-up exercise. |

| Increase the diversity and develop the capacity of its governance cadre. Government response: Partially accepted | • DFID did not completely agree that its locally recruited staff in country were underutilised. • Recent actions include giving locally recruited staff the same emails as UK-recruited staff, removing a highly visible symbol of differentiation between the two groups. | • It is too early to tell whether practices contemplated or begun will have the desired effect of making better use of the skills, experience and local knowledge of countryrecruited staff. |

| Improve the capturing of learning, particularly through an increased use of evaluations. Government response: Accepted | • Centrally, work is under way to develop a new approach to measuring results using technology to link evidence and evaluations. • At country level, both Nepal and Uganda are stepping up their research and evaluation plans. | • We would like to revisit this next year, to see the fruits of country-level efforts and check on the progress of DFID’s central evaluation strategy for governance programming. |

Table 2: Summary of findings on outstanding issues from earlier reports

| Progress since last year |

|---|

DFID’s approach to supporting inclusive growth in Africa: |

| DFID has increased its focus on inclusion within its economic development programming. While it is still up to country offices to decide how best to do this, DFID has taken a number of useful initiatives: • Including an inclusion module in its new Country Development Diagnostics process, to inform the next round of country business plans and economic development programmes. • Adopting the Inclusive Data Charter: Action Plan, with a commitment to disaggregating results data by gender, age, disability status and geographical locations. • Producing guidance on equity in value for money analysis, which encourages programme teams to identify target groups. • Launching a number of flagship programmes with a strong focus on inclusion, such as the Work and Opportunities for Women programme. We have been pleased to note that some of the most recent economic development programmes pay more attention to inclusion in their design, logframes and monitoring arrangements. |

The UK’s aid response to irregular migration in the central Mediterranean: |

| We assessed the monitoring and evaluation arrangements for DFID’s new flagship programme, the Safety, Support and Solutions Programme for Refugees and Migrants (SSS II), which was not yet up and running at the time of last year’s follow-up. SSS II now has a strong theory of change and a new monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) strategy. The first three tiers of this strategy are in place: MEL procedures for individual projects, administered by implementing partners, DFID monitoring visits to verify these, and DFID’s own programme-level monitoring. The fourth tier – an independent monitoring and rapid research and evidence facility – was at the inception phase at the time of our follow-up assessment. There had also been plans for a fifth tier, an independent evaluation. However, following preparatory work, DFID decided in 2019 not to commission this, relying instead on alternative arrangements for monitoring, rapid research and learning. Because this happened subsequent to our follow-up assessment, we plan to review these revised arrangements as part of next year’s follow-up. We found significant progress on the issue of ‘do no harm’ in UK migration-related aid programming. Conflict sensitivity and risk assessments in the design phase of programmes were thorough and shared with implementing partners. In the case of SSS II, key risks have been incorporated in the programme’s central risk register. We saw evidence of activities being terminated because the risks of doing harm were deemed to be too high. However, we would still like to see greater focus on the risk of doing harm in written MEL plans. |

The cross-government Prosperity Fund: |

| ICAI revisited three issues and found good progress on all of them. • Developing portfolio-level results indicators and associated systems for measuring results and learning from experience: The Prosperity Fund now has 15 key performance indicators (KPIs) for its strategic objectives. The theory of change is updated annually, and two monitoring, reporting, evaluation and learning (MREL) providers have been contracted, one for monitoring and reporting and another for evaluation and learning. • Implementing the Fund’s new procurement framework: A ‘Prosperity Framework’ for procurement processes is now in place and can be used by all government departments involved in the Fund’s activities. There are regular portfolio-level market engagement (in London and at post) and horizonscanning activities to assess market capacity constraints. Conflict of interest assessments are undertaken where potential risk exists. Importantly, both the KPIs and the Prosperity Framework were put in place ahead of the first round of the Fund’s business case approvals. • Introducing explicit and challenging procedures to assess the ODA eligibility of programmes: The Prosperity Fund has now formally clarified that the ownership of ODA compliance lies with spending departments. All staff with responsibility for Prosperity Fund programmes go through a training session on ODA compliance. There is guidance on gender and inclusion requirements and KPIs will be disaggregated by gender and income level. The new MREL systems will contribute to ensuring ODA compliance during the lifetime of programmes. |

When aid relationships change: DFID’s approach to managing exit and transition in its development partnerships |

| DFID is currently in the process of realigning and expanding on its strategic objectives in preparation for the next Spending Review. The department also prepared its evidence base, particularly through the Country Development Diagnostics (CDD) process, which fed into the business planning process for the 2019-20 financial year and the production of a new Single Departmental Plan. DFID has created two versions of the CDD, one of which is a Rising Powers Diagnostic targeted at seven identified countries or regions: China, India, South Africa, Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey and the Gulf region. DFID has also just finalised its development of six working principles for transition, with accompanying guidance material for how to incorporate these in the business planning process. The Rising Powers Diagnostic and the six working principles on transition are likely to bring greater coherence to DFID’s management of its changing relationships with middle-income countries. DFID shared the working principles with development leads in other government departments in May 2019. Many other government departments are involved in developing and transitioning UK relationships with rising powers and other middle-income countries, so it was a missed opportunity not to have involved them more closely earlier. We understand that other urgent government business, including Brexit preparations, delayed further consultation |

Conclusions

Overall, the response to ICAI’s recommendations from its 2017-18 reviews has been very encouraging, from DFID, other aid-spending departments and aid-spending funds. Last year, we noted how government actors new to aid spending were facing a steep learning curve, building up aid management capacity and developing, testing and bedding down processes to ensure that their work meets the high standards expected from UK aid. In our follow-up work for the CSSF, the Prosperity Fund and the GCRF we have seen significant improvements over the past year towards meeting these standards.

We do not expect all our recommendations to have equal resonance. But there are some in areas of strategic importance where it is currently too early to assess the impact of actions taken. We have identified three outstanding issues that we will return to in next year’s follow-up exercise:

- GCRF: While we have seen many improvements at this fund, we will return to the GCRF next year to assess: (i) the role of BEIS in providing overall accountability and responsibility in managing and assuring the GCRF, (ii) the block grants that are still being forwarded to the devolved funding councils via the GCRF, (iii) progress on the research hubs as they develop, in order to assess the effectiveness of this highly decentralised delivery model, and (iv) the effectiveness of the SCOR Board in influencing the allocation and delivery of aid-funded research and innovation programmes over time.

- Governance: We recognise that our follow-up took place too soon after publication, and we will therefore return to assess progress on all the recommendations in next year’s follow-up.

- Irregular migration: Overall, we found good progress on the outstanding issues we raised in last year’s follow-up. However, DFID has decided not go ahead with plans for an independent evaluation of its flagship migration-related programme, the SSS II, relying instead on alternative arrangements for monitoring, rapid research and learning. Because this happened subsequent to our follow up assessment, we plan to review these revised arrangements as part of next year’s follow-up.

Annex: Findings from individual follow-ups

In this annex, we present in more detail the results of our investigations of the government’s responses to 43 recommendations in eight ICAI reports published in 2017-18, as well as four outstanding issues from last year’s follow-up exercise. We focus on the most significant results from, or gaps in, the response. The presentation is chronological, beginning with the earliest published review from September 2017.

The Global Challenges Research Fund

ICAI published a rapid review of the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) in September 2017. With a budget of £1.5 billion from 2016 to 2021, the Fund constituted a significant increase in the UK government’s spending on development-oriented research. The review found that although progress had been made in the first 18 months of the GCRF’s existence, the rapid development of the Fund meant that many elements of its strategy, governance arrangements and procedures were unclear or weak. The review made four recommendations, summarised in the table below.

Table 3: Summary of recommendations and the government’s response

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| Formulate a more deliberate strategy to encourage concentration on highpriority development challenges | Partially accepted |

| Develop clearer priorities and approaches to partnering with research institutions in the Global South | Accepted |

| Provide a results framework for assessing the overall performance, impact and value for money of the GCRF portfolio | Accepted |

| Develop a standing coordinating body for investment in development research across the UK government | Accepted |

Formulate a more deliberate strategy to encourage concentration on high-priority development challenges

The GCRF’s strategy, published by the time the ICAI review came out, had a broad approach to tackle all Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), resulting in a scattered portfolio of research projects. To increase the chances of achieving transformative research impact, ICAI recommended the development of “a more deliberate strategy that encourages a concentration of research portfolios around highpriority global development challenges, with a stronger orientation towards development impact”. BEIS only partially accepted this recommendation, but there has been considerable activity to ensure stronger strategic coherence and development impact commensurate with a research fund of this size.

There are now six thematically distinct GCRF portfolios on global health, food systems, conflict, resilience, education and sustainable cities. The Fund has also launched 12 interdisciplinary research hubs around specific development challenges and appointed nine challenge leaders. Together, these initiatives encourage a concentration of interdisciplinary research portfolios around particular global challenges. As a result, the final portion of the GCRF’s budget (some £200 million) has been allocated with greater targeting and strategic direction.

BEIS has now strengthened its analytical capability and oversight over the GCRF portfolio with the appointment of dedicated staff and the formation of a new Portfolio & Operations Management Board, whose scope specifically includes oversight of programme-level portfolios. However, we are concerned that strategic oversight is still very devolved from BEIS to the delivery partners, with a reliance on UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), which is only one of the GCRF’s delivery partners.