ICAI follow-up review of 2018-19 reports

Letter from the chief commissioner

This is the first follow-up review that I have led since joining ICAI as chief commissioner in January 2019. It has been very useful for me to get to know the work ICAI did before I arrived, to ensure that we continue to press for the improvements in UK aid work that we identified in earlier reviews.

When we consulted about how ICAI itself could do better, one suggestion we received was that ICAI could make its follow-up reviews even more rigorous and give our scrutiny more grip if we scored departments’ responses to our recommendations. We decided to try this, and it has been a good, if challenging, discipline to make judgements on which responses are adequate, taking into account what could reasonably be expected.

This process has made us think even harder about how to word recommendations for the greatest impact, and to recognise how they work together. We do not expect all recommendations to have equal importance, so sometimes the response can be judged inadequate even where the majority have been used to improve the work. We also try to take into account how external events may have meant that one or more of our recommendations are less relevant, or expectations need adjusting.

External events have in the past year created many challenges, even where departments were very responsive and ministers committed to the improvements recommended – as in the cases of climate change and maternal health. Nevertheless, we did see for the most part continued efforts to respond to ICAI’s work. We have been careful to limit the number of cases where we identified the need to follow up through this process next year. We recognise that, although scrutiny is more important than ever before, it can be time-consuming, and we want to be sure that we can continue to achieve impact even with the pressures on the time of officials created by the COVID-19 pandemic and as UK aid moves into a new governance structure with the creation of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office.

Dr Tamsyn Barton

Chief Commissioner

Executive summary

This report presents the results of our follow-up exercise to assess progress made by aid-spending government departments and funds on addressing ICAI recommendations. It covers nine ICAI reviews in all: eight published during the annual review cycle from July 2018 to June 2019, as well as one earlier report from November 2017. This earlier report is the first of two reports scrutinising the approach to procurement by the Department for International Development (DFID), and we decided to follow up these two reviews in parallel. In addition to these nine follow-ups, we also revisit three issues identified as outstanding from last year’s follow-up review.

Table 1: List of Year 8 reviews and outstanding issues from earlier years covered by this follow-up review

| Follow-ups | |

|---|---|

| Achieving value for money through procurement: DFID’s approach to its supplier market ("Procurement 1") | November 2017 |

| Achieving value for money through procurement: DFID’s approach to value for money through tendering and contract management ("Procurement 2") | September 2018 |

| DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments | October 2018 |

| Assessing DFID’s results in improving Maternal Health | October 2018 |

| The UK’s approach to funding the UN humanitarian system | December 2018 |

| International Climate Finance: UK aid for low-carbon development | February 2019 |

| CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states | March 2019 |

| DFID’s partnerships with civil society organisations | April 2019 |

| The Newton Fund | June 2019 |

| Outstanding issues | |

| Global Challenges Research Fund | September 2017 |

| The UK’s aid response to irregular migration in the central Mediterranean | March 2017 |

| DFID’s governance work in Nepal and Uganda | June 2018 |

Overview on the response to ICAI’s recommendations

The past year has provided a challenging climate of uncertainty and disruption for UK aid. Cabinet reshuffles – with four secretaries of state for international development over a one-year period – and a general selection led to delays in the development of strategies and plans, as ministerial teams came and went. Brexit preparations drew some staff away from their usual tasks. Then, the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically compounded the stress on human resources as the government reordered its priorities in order to focus attention on the healthcare and economic emergencies triggered by the pandemic. And finally, on 16 June 2020, the government announced a plan to merge DFID with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO).

Considering this context, the government’s response to ICAI’s recommendations from its 2018-19 reviews has been, on the whole, positive. Many improvements have been achieved despite stretched resources, as teams and departments chose priorities carefully and worked, as the head of one DFID team described, “above and beyond”. Among specific highlights this year, we include:

- DFID’s results in maternal health: DFID responded swiftly to ICAI’s concerns that the models it used to assess “maternal lives saved” were flawed.

- The UK’s approach to funding the UN humanitarian system: After ICAI’s review, DFID conducted an internal review of core support to the UN’s Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF), which agreed with ICAI that CERF should be removed from the joint UN business case and collective payment by results approach. A standalone business case for CERF is being developed and is planned to be launched in 2020.

Scoring the government’s progress

This year, for the first time, we introduced a scoring element to the follow-up exercises. For each of the nine reviews we follow up, we provide a score of adequate or inadequate, illustrated by a tick or a cross.

An inadequate score results from one or more of the following three factors:

- Too little has been done to address ICAI’s recommendations in core areas of concern (the response is inadequate in scope).

- Actions have been taken, but they do not cover the main concerns we had when we made the recommendations (the response is insufficiently relevant).

- Actions may be relevant, but implementation has been too slow (the response is insufficiently implemented) and we are not convinced by the reasons for the slowness.

We will return to issues where the government response has been inadequate, either through the next follow-up or through future reviews.

Of the nine reviews this year, four were given an inadequate score:

- The Newton Fund, due to inadequate progress in addressing ICAI’s concerns over tied aid and attention to poverty reduction as the Fund’s primary purpose.

- DFID’s approach to tendering and contract management, as a result of DFID’s failure to put in place a formal contract management regime, despite the risks this entails for programme results.

- CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states. While CDC has put in place mechanisms and tools for improving its attention to development impact, the evidence is not yet clear that these are sufficiently shaping investment practices. CDC’s plans for opening and expanding country offices remain insufficiently ambitious, particularly in Africa.

- The UK’s International Climate Finance (ICF): a new cross-departmental strategy for the ICF has not yet been published (the current strategy is from 2011). With the UK government hosting COP26 and having committed to doubling its spending on climate finance, the urgency of communicating the ICF strategic priorities to other donors and the UK public is higher now than when ICAI wrote its original recommendation.

Cross-cutting themes

Every year the follow-up process throws up issues of strategic importance to UK aid spending that cut across many of our reviews and recommendations. In this year’s follow-up review, we discuss three themes that affected the government response to our recommendations and which will continue to be salient in our current review programme:

- steady (but reduced) progress on ICAI’s recommendations in a period of extensive disruption

- the role of clear and consistently applied strategies in achieving development impact

- challenges in improving central and country-level coherence in DFID.

Outstanding issues

There are areas of strategic significance where further follow-up next year will be beneficial. This year we identified three reviews for further follow-up:

- The Newton Fund

- DFID’s approach to tendering and contract management

- CDC’s investment in low-income and fragile states

In addition, we will follow up on the progress on the new ICF strategy as part of our forthcoming review on UK aid to tackle biodiversity and deforestation. We also keep open the option of returning to the maternal health review again if the publication of the Ending Preventable Deaths Action Plan and the Health Systems Strengthening Position Paper does not go ahead as planned later in 2020 or if they are of insufficient quality.

Table 2: Overview of progress and scoring for individual reviews

| Our assessment of progress on ICAI recommendations | Score |

|---|---|

| Achieving value for money through procurement: DFID’s approach to its supplier market (“Procurement 1”) | |

| DFID has made good progress on most recommendations, leading to a stronger approach to its supplier market. The department has progressed significantly with its use of open-book accounting and monitoring and management of fee rates. It has made use of a number of communication channels to promote new suppliers, support small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and local suppliers and encourage overseas bidders. However, there has been a disappointing failure to increase the number of local suppliers from developing countries. | Adequate |

| Achieving value for money through procurement: DFID’s approach to value for money through tendering and contract management (“Procurement 2”) | |

| There have been improvements in how DFID manages consultations and information, but this will have little impact on overall performance without progress on instituting a formal contract management regime and appropriate levels of staff training. The response to this review’s recommendations is therefore inadequate and we will return to the issue of contract management next year. | Inadequate |

| DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments | |

| DFID has made notable progress on all of ICAI’s recommendations, despite stretched human resources. The department has developed increasingly sophisticated approaches to programme design and delivery. New guidance material and tools have helped it manage infrastructure programme challenges, including ensuring consideration of the impact of its infrastructure investments on the poorest and most vulnerable. However, efforts to improve economic appraisal of projects have been limited. Gaps remain in the guidance material available, and sustainability of results is a concern due to limited project timeframes and delays in initiating successors to major centrally managed programmes. In engaging with China on infrastructure cooperation, there is an ongoing need to carefully monitor potential trade-offs between commercial, trade and developmental interests at policy, influencing and programme levels. | Adequate |

| Assessing DFID’s results in maternal health | |

| DFID’s response has been comprehensive, and the changing shape of DFID strategy and programming on maternal health is already evident. However, initiatives are at an early stage and it will be some time before their full scope and influence are evident. It will be crucial to keep the momentum and to publish the delayed Ending Preventable Deaths Action Plan and Health Systems Strengthening Position Paper. DFID reacted swiftly to one of the central concerns of the ICAI report: how the department estimated and reported its results. Some changes have already been made, and a new approach to results reporting is being developed for the next spending review period. DFID also enhanced its emphasis on the need for good quality, respectful care for women and their babies and we found evidence of increased focus on adolescents and poorer women within DFID’s new family planning programmes – as well as of data disaggregation to monitor this. | Adequate |

| The UK’s approach to funding the UN humanitarian system | |

| Key aspects of ICAI’s recommendations have been taken forward. The third-party monitoring and evaluation function has now been contracted, and the UN’s Central Emergency Response Fund has been removed from the joint UN agencies business case and payment by results system. Good progress has been made on DFID’s support of multilaterals’ coordination of joint needs assessments and improving accountability to affected populations. However, more needs to be done in other reform areas, including localisation, the UN’s subcontracting processes, UN-NGO partnerships, and how the UN delivers its normative functions at country level. | Adequate |

| International Climate Finance: UK aid for low-carbon development | |

| A commitment to double UK spending on climate finance and preparations for hosting COP26 have been accompanied by technical work to develop the ICF’s thematic priorities, value for money approach and governance structure. Transparency and information sharing have improved, but we are concerned about continued significant delays to producing the new ICF strategy, the limited progress in developing a more structured and deliberate approach to mainstreaming low-carbon development in DFID, and the limited efforts to use communications on the ICF to pursue UK global leadership in the area of climate finance. We have therefore scored this review as inadequate. | Inadequate |

| CDC’s investments in low-income and fragile states | |

| CDC has made notable progress in strengthening its tools to assess development impact, but it is not yet clear how these tools are shaping investment decisions and management. CDC has completed all its value creation strategies, but in most cases there has been limited action to implement them. CDC has deepened its collaboration with DFID. However, its country expansion efforts – based on plans agreed with DFID – remain unambitious, posing challenges for investment sourcing, oversight and securing development impact. CDC has expanded communications on its Catalyst Portfolio but made limited progress on communicating the rationale behind its investment approach for the Growth Portfolio. | Inadequate |

| DFID’s partnerships with civil society organisations | |

| DFID’s ambitious commitments may amount to a new approach to civil society partnerships – with less bias towards UK civil society organisations (CSOs) and more attention to the longer-term health of civil society in partner countries. Actions have been planned and implemented quickly, but with care. Learning processes have been built into business plans. If these commitments continue to be implemented during the difficult period ahead, CSOs should start seeing the results of DFID’s new approach in the coming years. Being a reliable partner to CSOs will be crucial in this time of significant stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Support for local CSOs will need to be an important element of UK aid's support of the poorest and most vulnerable, who will suffer most from the economic consequences of the pandemic. | Adequate |

| The Newton Fund | |

| Governance and oversight mechanisms have been strengthened, and there has been substantial improvement on gender equality, diversity and inclusion. However, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) has not interacted with the fundamental concerns of ICAI’s review, which focus on the Fund’s attention to development impact and a funding model that ties almost all the UK official development assistance (ODA) to UK research institutions. We find the overall response to ICAI’s recommendations inadequate and will return to these fundamental concerns as an outstanding issue in next year’s follow-up exercise. | Inadequate |

Table 3: Overview of progress on outstanding issues from earlier reports

| Outstanding issue | Our assessment of progress since last year |

|---|---|

| The Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) | |

| To come back to how promising innovations are functioning, and to revisit ongoing concerns over tied aid and value for money for the portion of the Fund distributed through the funding councils. | The Research Hubs are a particularly promising innovation from the perspective of potential development impact, while the cross-departmental Strategic Coherence of ODA-funded Research (SCOR) Board appears well placed to encourage greater cross-government coherence of ODA-funded research. We remain, however, deeply concerned about the quality-related grants to UK higher education institutions allocated via the four funding councils. This is in stark contrast to the UK’s untying commitment and is poor value for money, allocated with little consideration of aid effectiveness or the aims and objectives of the GCRF. |

| The UK’s aid response to irregular migration in the central Mediterranean | |

| The adequacy of the MEL arrangements for DFID’s flagship migration programme, SSS II. | Although, as highlighted in the original review and subsequent follow-ups, the monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) arrangements for the Safety, Support and Solutions Programme for Refugees and Migrants (SSS II) were too late in being developed and implemented, we find that they are now of an adequate standard to support this complex programme. |

| DFID’s governance work in Nepal and Uganda | |

| ICAI returned to all the recommendations of this review, since last year’s follow-up exercise took place too early to allow an assessment of the effectiveness and impact of the improvements underway. | DFID has made good progress on strengthening its approach to governance. The new Governance Position Paper supports business planning and the mainstreaming of governance goals into other sectors. It reinforces the focus on adaptive programming, the use of evidence in designing and evolving programming, and thinking and working politically. Governance advisers now spend more of their time on providing technical inputs, and DFID has been making better use of locally appointed staff. There is less progress on improving the diversity of governance advisers, and there remains a dearth of evaluations of DFID’s governance work. |

Introduction

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) provides robust, independent scrutiny of the UK’s official development assistance (ODA), to assist the government in improving the effectiveness and impact of its interventions and to assure taxpayers of the value for money of UK aid spending. Our main vehicle for this scrutiny is the publication of reviews on a broad range of topics of importance to the UK’s aid strategy. A crucial part of these reviews is our annual follow-up process, where we return to the recommendations from the previous year’s reviews to see how well they have been acted upon. New to this year’s review is the scoring of the government’s action as adequate or inadequate (see below for the criteria used), to provide the reader with a clear visual summary of the relevance and effectiveness of the response to ICAI’s recommendations.

This report provides a record for the public and for Parliament’s International Development Committee (IDC) of how well the UK government has responded to ICAI recommendations. The follow-up process is also an opportunity for additional interaction between ICAI and responsible staff in aid-spending departments, offering feedback and learning opportunities for both parties. The follow-up process is central to our work to ensure maximum impact from our reviews.

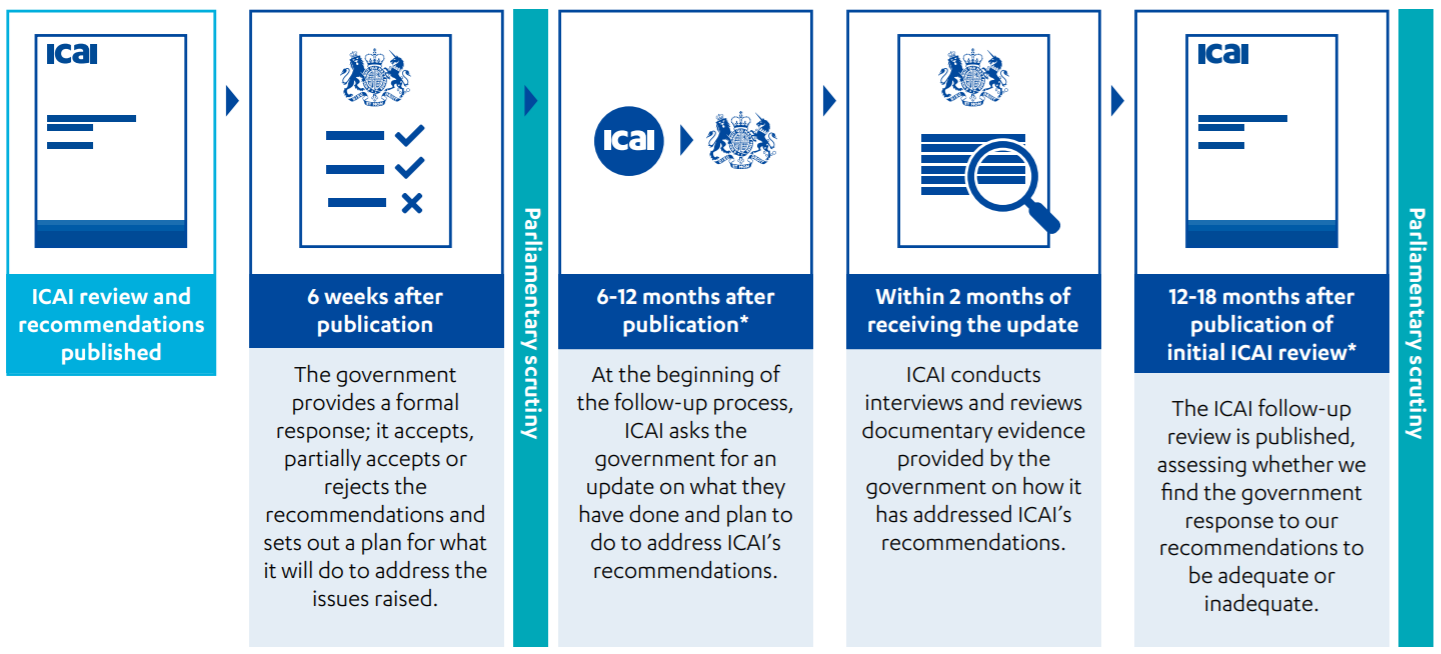

Figure 1: Timeline of ICAI’s annual follow-up process

*We conduct our follow-up assessment on an annual basis, starting in January and publishing in the summer. The follow-up covers a number of reviews which are selected according to their publication date (if a review is only published a few months prior to the follow-up process then it will be covered in the following year). If we are unsatisfied with the government’s progress on any of our recommendations, we then follow up on those areas again during the next year’s assessment.

The follow-up process is structured around the recommendations provided in each ICAI review (see Figure 1 above for an illustration of the process). Soon after the original ICAI review is published (usually six weeks), the government provides a formal response. The response sets out whether the government accepts, partially accepts or rejects ICAI’s recommendations and provides a plan for addressing the issues raised. This is followed by a hearing, usually in the ICAI sub-committee of the International Development Committee. Then the formal follow-up process starts, normally between six and 12 months after the publication of the original review (timing depending on how early in ICAI’s annual review cycle the relevant report was published).

To start the follow-up exercise, ICAI asks the aid-spending departments and organisations for an update on what they have done and plan to do. This is followed by an evidence gathering stage, where we investigate the extent to which the government has done what it promised and – considering any additional relevant actions – determine if this is an adequate response. The findings are reported and scored in the follow-up review. After publication, there is parliamentary scrutiny of the review’s findings.

Introducing scoring of the follow-up exercises

New to the follow-up review this year is the introduction of scoring. For each of the nine reviews we return to, we have provided a tick or a cross, depending on whether we find the overall progress adequate or inadequate. The score takes into consideration the wider context, including external constraints, in which government actions have taken place (see more on the turbulent period that this follow-up review covers in Section 3 of this report). It also considers the time the relevant government department or organisation has had to plan and implement changes.

An inadequate score results from one or more of the following three factors:

- Too little has been done to address ICAI’s recommendations in core areas of concern (the response is inadequate in scope).

- Actions have been taken, but they do not cover the main concerns we had when we made the recommendations (the response is insufficiently relevant).

- Actions may be relevant, but implementation has been too slow and we are not able to judge their effectiveness (the response is insufficiently implemented).

It should be noted that the third factor – the adequacy of implementation – is not a simple question of checking if plans have been put into practice yet. We take into consideration how ambitious and complicated the plans are, and how realistic their implementation timelines are. Some changes are ‘low-hanging fruit’ and can be achieved quickly, while others demand long-term dedicated attention and considerable resources. An inadequate score due to slow implementation will only be awarded if ICAI finds the reasons provided for lack of implementation unconvincing.

This year’s follow-up review covers nine ICAI reviews with a total of 40 recommendations. After briefly setting out our methodology, we discuss three cross-cutting issues that affected how well our recommendations have been taken up. This is followed by the main body of the report: an account of progress on each of the nine reviews and the three outstanding issues covered by this year’s follow-up report. We sum up with a brief conclusion and a list of the reviews and recommendations we plan to return to again next year.

Methodology

When we follow up on the findings and recommendations of our past reviews, we focus on four aspects of the government response:

- whether the actions proposed in the government response are likely to address the recommendations

- progress on implementing the actions set out in the government response, as well as other actions relevant to the recommendation

- the quality of the work undertaken and how likely it is to be effective in addressing the concerns raised in the review

- the reasons why any recommendations were only partially accepted (none of the 2018-19 recommendations were rejected).

We begin by asking the relevant government department to prepare a brief note, accompanied by documentary evidence, summarising the actions taken to implement the response to our recommendations. We then check that account through interviews with the responsible staff, both centrally and in country offices, and by examining relevant documentation. Where necessary, we also interview external stakeholders, including other UK government departments, multilateral partners and implementers. To ensure we maintain sight of broader developments, we also assess whether ICAI’s findings and analysis have been influential beyond the specific issues raised in the recommendations.

The follow-up process for each review concludes with a formal meeting between a commissioner and the senior civil service counterpart in the responsible department.

At the end of the follow-up process, we identify issues that warrant a further follow-up the following year. The decision is based on the continuing strategic importance of the issue, the inadequate or incomplete action taken to address it, and whether or not there will be other opportunities for ICAI to pursue the issue through its future review programme.

We also use the follow-up process to inform internal learning for ICAI about the impact of our reviews on UK aid and how we communicate our findings and recommendations in order to achieve maximum traction with the government.

Box 1: Limitations to our methodology

The follow-up review addresses the adequacy of the government response to ICAI’s recommendations. Its findings are based on checking and examining the government’s formal response, and its subsequent actions in relation to the recommendations from the review. The time and resources available for this evidence gathering exercise are limited, and not comparable to a full ICAI review.

Cross-cutting themes

During the course of our follow-up exercise, we found three themes of strategic importance that recurred across several of the 2018-19 reviews which affected the government response to our recommendations and which will continue to be salient in our current review programme.

Steady (but reduced) progress in a period of extensive disruption

2019 was an eventful year in British politics, with significant impact on UK aid delivery. Across the UK government some staff were drawn away from their usual tasks to prepare for Brexit. Many aid delivery teams told us they were significantly affected. Then, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically compounded the stress on human resources as the government reordered its priorities to focus attention on the healthcare and economic emergencies triggered by the pandemic. Finally, as this report was being completed, the plan to merge DFID with the FCO was announced.

There were several changes in political leadership over the past year, including a cabinet reshuffle in July 2019, a general election in December and then another reshuffle in February 2020. DFID saw even more disruption. The department had three secretaries of state during 2019 (Penny Mordaunt, Rory Stewart and Alok Sharma), with a fourth, Anne-Marie Trevelyan, taking office in February 2020. This led to repeated interruptions in planned work due to restrictions in the pre-election period and delays in obtaining ministerial approval, as new ministers were brought up to speed on current initiatives and set out their own priorities.

We have seen the impact of these disruptions across the government’s response to ICAI recommendations. Frequent ministerial changes contributed to delaying the completion and publication of strategies and guidance – including some that had been a long time in the making. As some staff were redeployed to other departments for Brexit preparations, stretched human resources meant that initiatives demanding coordination and cooperation across several DFID teams or several government departments were particularly vulnerable to being deprioritised, since cross-team work tends to be more difficult and time-consuming.

Examples of the impact of disruptions include:

- DFID’s funding of the UN humanitarian system: We were told that Brexit preparations had a significant impact on the staff time available to implement the government’s commitments, with members of the DFID Conflict, Humanitarian and Security team at times redeployed, including several of those leading the engagement with UN agencies. Except for safeguarding issues, which it continued to prioritise, DFID had little capacity to engage with UN humanitarian agencies on improving the way they subcontract non-government organisations (NGOs) or manage their delivery chains.

- DFID’s investments in transport and urban infrastructure: Development of a new SMART guide on infrastructure programming was delayed, as senior staff from the infrastructure cadre were redeployed to Brexit planning and the management of major events and commitments such as the Africa Investment Summit and the Infrastructure Commission.

- DFID’s partnerships with CSOs: DFID’s civil society team lost two staff to Brexit-related redeployment. DFID’s plans to institute a shared approach to learning across the many different departments and teams that work with CSOs fell by the wayside.

- DFID’s results in maternal health: The long-awaited Health Systems Strengthening Position Paper is an example of the results of cumulative disruption. After first being delayed by the frequent turnover in secretaries of state, it was finally scheduled for publication in December 2019. However, this was postponed due to restrictions in the pre-election period, and then put back again so that publication coincided with the release of the Ending Preventable Deaths Action Plan, which is still under development. Both are now likely to be further delayed due to the COVID-19 response.

Considering this difficult and fast-changing context, it is notable that DFID and other departments delivering UK aid have managed to make good progress in tackling many of the concerns raised in ICAI reviews. Where prioritisation had to be done, it was generally done in a thoughtful and realistic manner. Careful balancing of priorities will continue to be important, as the response to the COVID-19 pandemic puts a heavy burden on UK aid management capacity in the coming period.

This said, the lack of progress on some reviews cannot be put down (at least not solely) to external pressures and events. We found, for instance, that:

- The Newton Fund’s lack of progress on addressing ICAI’s concerns over tied aid and the lack of attention to poverty reduction cannot be explained by human resource constraints, as BEIS has bolstered staffing and governance structures for the Newton Fund and its sister fund, the Global Challenges Research Fund.

- DFID’s failure to put in place a formal contract management regime with sufficient staff training cannot be attributed to external events.

- CDC, which was not affected by political change or Brexit redeployment, retained its unambitious plans for increasing its country presence in Africa, with a slow rate of opening and expanding country offices.

- The departments responsible for the UK’s International Climate Finance (ICF) are yet to publish a new cross-departmental strategy for the ICF. As the strategy has not been updated since 2011, recent events do not justify this delay.

The role of clear and consistently applied strategies in achieving development impact

Delivering aid impact calls for clear strategies and well-articulated priorities. ICAI reviews have consistently found that UK aid is most effective when the responsible departments focus their efforts by setting down clear priorities and how they propose to achieve them. This helps to promote coherence and consistency across complex portfolios. It is therefore not surprising that many ICAI recommendations call for new or updated strategies, or for their more consistent application.

This year, the challenging political context has made it difficult to develop or strengthen strategies in a range of policy areas, which has, in turn, hampered effectiveness. In the cases where new or strengthened strategies have been produced – often following protracted processes – they have proved key to improving the impact and value for money of UK aid.

The follow-up of DFID’s governance work in Nepal and Uganda is an example of this. Our original review found that a lack of strategic approach undermined continuity of programming and long-term focus. After delays, DFID published a Governance Position Paper in March 2019. This led to significant improvements in DFID’s governance work by giving the department a common language and conceptual framework, strengthening business planning and increasing the demand for governance advisers to support colleagues in other sectors.

The UK’s International Climate Finance, on the other hand, is an example of a strategic gap yet to be addressed. While the government has undertaken analytical work to underpin a new cross-departmental strategy for the ICF, officials interviewed for this follow-up review – even before the scale of the impact of the COVID-19 response was clear – could not confirm when the new strategy would be published. Working without a public strategy undermines public debate and scrutiny, and risks compromising the coherence of the UK’s international climate investments.

Poverty reduction is the primary purpose of UK aid. Clear strategies for retaining this focus on poverty reduction and development impact are particularly important in the case of aid spending identified as ‘dual purpose’. ICAI’s reviews of the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) and the Newton Fund – both large research and innovation funds managed by BEIS – identified weaknesses in their focus on poverty and development results. Both funds are actively pursuing secondary purposes, such as supporting UK research and innovation and building UK soft power. The GCRF responded well to ICAI’s concern by developing a clear strategy for sustainable and transformative development impact. However, the Newton Fund has not gone through a similar transformation.

With aid funding now distributed across more departments and funds, clear strategies are important to maintaining the coherence and integrity of UK aid. In particular, it is important that aid-spending departments charged with pursuing secondary benefits to the UK set out clearly how they propose to manage the trade-offs and avoid compromising their primary purpose of promoting poverty reduction.

Challenges in improving central and country-level coherence in DFID

Historically, DFID has been one of the most decentralised global aid agencies. As the OECD’s past peer review processes pointed out, this helped the department to adapt to changing contexts and be more responsive to its partner countries.

In recent years, however, ICAI has witnessed a trend towards the centralisation of a number of functions within DFID. The spending authority given to country offices has been reduced. Large centrally managed programmes have been established to boost DFID’s global effort in priority areas such as girls’ education. Increasingly, technical and programme management capacity is located in central or regional ‘platforms’ that provide support across multiple country programmes.

There are likely to be both advantages and disadvantages to this move, and some tensions and compromises that will need to be carefully managed. It may boost the department’s overall technical and delivery capacity, while making it more difficult to be responsive to specific country needs. The ICAI reviews followed up on this year give some reason for confidence that DFID has been managing these tensions appropriately, but also raise questions about the risks of continuing centralisation.

Our review of DFID’s maternal health work had raised questions as to whether centrally managed programmes were helping partner countries to build effective national health systems. Our follow-up found that a number of new centrally managed health programmes had a strong focus on health systems strengthening and addressing quality of care. With the eventual publication of the Ending Preventable Deaths Action Plan, it will become clearer whether UK aid is mitigating the risks of centralisation.

In relation to transport and urban infrastructure, ICAI has observed that centrally managed programmes have enabled DFID to scale up its efforts in a technically demanding area, but have also made it more difficult to manage relationships with national counterparts. In our follow-up, we found that a new centrally managed infrastructure programme will support country offices with the design and review of new initiatives and give them access to a pool of technical experts. However, DFID was still working on how to ensure that multi-country platforms are flexible enough to respond to country needs.

Our second follow-up on DFID’s governance work in Nepal and Uganda identified a transfer of programme management functions from country offices to headquarters. This has helped free up the time of governance advisers to support sector work and develop influencing relationships with country stakeholders. However, this is a recent and still evolving reform, and there is a risk that the centralisation of programme management functions may compromise the ability of country offices to manage their programmes in a flexible and adaptive manner, which has been one of the strengths of DFID’s governance portfolio.

Our two reviews of DFID’s procurement also addressed the changing balance of management functions between the central and country offices. DFID’s objective is to build commercial capacity across its country offices. However, its procurement rules are adapted for large UK-based suppliers and are constraining its ability to work with local contractors in its partner countries, which would require a more flexible and adaptive approach.

An important development relating to the structures through which UK aid is managed, which emerged towards the end of this follow-up review cycle, was the announcement of a plan to merge DFID with the FCO. The announcement was preceded by a government directive that DFID country offices should now report directly to ambassadors or high commissioners.

Findings from individual follow-ups

This main section of the report presents the results of our follow-up investigations of the government’s responses to the recommendations of nine ICAI reports. We present the results and score of each investigation in turn, focusing on the most significant results from, or gaps in, the response. We then end this section with a discussion of outstanding issues in three reviews from last year’s follow-up: on the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), evaluating irregular migration programming, and DFID’s governance work.

Achieving value for money through procurement: DFID’s approach to its supplier market (“Procurement 1”)

Adequate

Good progress on three out of four recommendations, leading to a stronger approach to DFID’s supplier market, although a disappointing failure to increase the number of local suppliers.

ICAI published the first of its two reports on how DFID achieves value for money through procurement in November 2017. This Procurement 1 report gave a green-amber score on how DFID interacted with its supplier market. It concluded that, after a slow start on market shaping, there was evidence of progress and a serious effort by DFID to get to grips with the challenges of achieving value for money through engagement with its supplier base. It offered four recommendations.

Table 4: ICAI’s recommendations and the government response

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| DFID should adopt a more systematic approach to promoting the participation of local suppliers, to the extent permitted within procurement regulations, including measures at the central, sector and country office levels to encourage the emergence of future prime contractors from developing countries. | Accepted |

| DFID should develop clear plans for how it will progress its use of open-book accounting and improve fee rate transparency and ensure that its plans are clearly communicated to the supplier market, to minimise the risk of unintended consequences. | Accepted |

| DFID should accelerate its efforts to improve communication of pipeline opportunities to the market. It should also assess what potential information advantages are gained by participants in its Key Supplier Management Programme and ensure that this is counterbalanced by more effective communication with all potential suppliers. Internally, DFID should provide clearer guidance to staff as to what can and cannot be discussed during key supplier meetings. | Partially accepted |

| A stronger change management approach, with explicit objectives that are clearly communicated to staff. Plans should be supported by robust monitoring and management information arrangements, to enable full transparency, regular progress reporting and mitigation of potential negative effects. | Accepted |

Recommendation 1: Adopt a more systematic approach to promoting the participation of local suppliers, including measures to encourage future prime contractors from developing countries

ICAI’s review recommended that DFID promote the participation of local suppliers by identifying opportunities for them to compete directly for DFID contracts, increasing supervision of the terms on which prime contractors engage local suppliers, and inducing DFID’s prime contractors to invest in building local capacity.

The actions undertaken by DFID have the potential to address a number of the concerns underpinning ICAI’s recommendation. The department continues to seek new ways to engage with local suppliers and small and medium enterprises (SMEs), including greater use of social media, early market engagement, publication of its pipeline and a dedicated and monitored email address for potential contractors.

DFID has slightly diversified its contractors. In 2016-17, 92% of DFID contracts by value went to UK-registered suppliers and only 3% to suppliers in developing countries as prime contractors. In 2018-19, DFID increased its overseas bidders from 13% to 20%. However, the major non-UK bidders are from Western countries and sustained efforts will be required to recruit local, in-country supply partners. The actions DFID has taken, combined with the gathering of more systematic evidence, should help the department improve its analysis and tracking of local supplier participation, but this has not yet resulted in the increased use of local suppliers.

Recommendation 2: Develop clear plans for open-book accounting and improve fee rate transparency. Ensure plans are clearly communicated to the supplier market, to minimise the risk of unintended consequences

ICAI’s 2017 report noted that DFID has had contractual rights for some time to access certain information on supplier costs and profits, but had not made use of these rights due to capacity constraints. The report was also concerned about risks of distorting market behaviour attached to the control of costs and profits, and recommended minimising such risks through clear communication with suppliers.

Since ICAI’s review, DFID has introduced tougher scrutiny of costs through new clauses in contract terms and conditions that allow the department to inspect costs, overheads, fees and profits of supply partners. DFID has developed a robust open-book accounting process to enable better scrutiny and control of costs by its supply partners. It also created an eligible cost policy and a template to help suppliers identify the types of costs eligible for inclusion within their bids. 2019 was the first year of monitoring profit levels, which provided DFID with details about the range of profit declared by suppliers. Profit levels are monitored by the programme’s senior responsible officer (SRO) and commercial delivery manager.

DFID created a fee rates database in 2016. This is a database of all fees proposed in tenders, with currently over 23,000 entries. Using the database, DFID actively monitors and benchmarks fee rates against other global organisations, and by geography, sector and job family. As a result, it has recently applied a fee rate ceiling to around 22% of contracts: tenders that exceed this maximum rate are automatically excluded from technical evaluation. This has helped DFID to control prices better.

To communicate the fee rates approach to suppliers, DFID has improved its online guidance and FAQs and made the commercial cost template easier to complete for potential suppliers.

Recommendation 3: Improve communications and engagement with its supplier market

The 2017 review found that weaknesses in DFID’s approach to its supplier market were partly due to poor communication, and a lack of early market engagement and a comprehensive pipeline of opportunities. It recommended that: “DFID should accelerate its efforts to improve communication of pipeline opportunities to the market. It should also assess what potential information advantages are gained by participants in its Key Supplier Management Programme and ensure that this is counterbalanced by more effective communication with all potential suppliers. Internally, DFID should provide clearer guidance to staff as to what can and cannot be discussed during key supplier meetings.”

DFID only partially accepted this recommendation, noting that it was already improving its communications with the supply market and that its Key Supplier Management Programme did not provide preferential treatment to key suppliers. It has nevertheless made good progress on addressing the concerns underpinning ICAI’s recommendation. DFID now uses a variety of communication channels, including greater use of social media, particularly Twitter, to communicate pipeline opportunities to the market. It also hosts early market engagement events in the UK, online and in partner countries, and works with other government agencies to host Open for Business events across the UK.

DFID launched its Strategic Relationship Management (SRM) programme in early 2018. There are currently 42 supply partners covering 80% of DFID annual spend through 346 contracts. This is significantly wider than the previous Key Supplier Management Programme, which covered 14 organisations in 2016-17.

Guidance on the SRM programme is now given to all DFID staff members, identifying what can and cannot be discussed during supply partner meetings. Staff are required to read this guidance and declare that they have read and understood it. It is updated annually and there is, in addition, a corporate compliance regime in place to ensure that all internal processes and procedures are followed. This reduces the risk of challenge from supply partners of preferential treatment.

Recommendation 4: A stronger change management approach, clearly communicated to staff and supported by robust monitoring and management information arrangements

ICAI’s 2017 review noted that DFID struggled to demonstrate the effectiveness of its reform initiatives for two reasons: the expected benefits have not been clearly articulated, and the initiatives have not been designed to include monitoring mechanisms to facilitate continuous learning. ICAI recommended that DFID adopt a systematic change management approach, clearly communicated to all staff. DFID accepted this recommendation, and has undertaken a range of useful activities:

- introducing a new Commercial Board to strengthen its governance processes

- establishing a review mechanism by non-executive directors

- developing an annual procurement and commercial report

- improving its monitoring and management information arrangements, particularly relating to the financial health of its key supply partners.

In all, these actions mean that DFID has strengthened its governance and oversight of the commercial reform programme, particularly through introducing a Commercial Board. It is now engaged in regular feedback sessions with supply partners through a variety of online and face-to-face mechanisms.

Conclusion

DFID has progressed significantly with its use of open-book accounting and monitoring and management of fee rates. The department has made use of a number of communication channels to promote new suppliers, support SMEs and local suppliers, and encourage overseas bidders. These changes have resulted in ongoing improvements to supplier market management. However, we are yet to see an increase in the number of local suppliers from developing countries.

Achieving value for money through procurement: DFID’s approach to value for money through tendering and contract management (“Procurement 2”)

Inadequate

There has been a good response to the first two recommendations, on improving consultations and management information. But these will have little impact on overall performance without progress on the third recommendation. Without a formal contract management regime and appropriate levels of staff training, we find the response to this review’s recommendations inadequate.

The second of ICAI’s performance reviews of DFID’s approach to achieving value for money through procurement focused on tendering and contract management. The review was published in September 2018 and gave the department a green-amber score. It concluded that DFID had an appropriate overall approach to procurement with good performance in most areas of tendering. However, it found significant weaknesses in DFID’s contract management and offered three recommendations to improve the department’s practices in this area.

Table 5: ICAI’s recommendations and the government response

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| Before the next major revision of its supplier code and contracting terms, or future changes that may materially affect suppliers, DFID should conduct an effective consultation process with its supplier market, to ensure informed decisions and minimise the risks of unintended consequences. | Accepted |

| DFID should accelerate its timetable for acquiring a suitable management information system for procurement, to ensure that its commercial decisions are informed by data. | Accepted |

| DFID should instigate a formal contract management regime, underpinned by appropriate training and guidance and supported by a senior official responsible for contract management across the department. The new regime should include appropriate adaptive contract management techniques, to ensure that supplier accountability is balanced with the need for innovation and adaptive management in pursuit of development results. | Accepted |

Recommendation 1: Before making changes affecting suppliers, conduct an effective consultation process with the supplier market, to ensure informed decisions and minimise the risks of unintended consequences

The 2018 ICAI review noted that the last Supplier Review included little consultation with supply partners, leading to a loss of feedback and market intelligence and a greater risk of unintended consequences arising from reforms. ICAI recommended that greater communication would help rebuild the relationship with its suppliers. DFID accepted the recommendation and has undertaken a range of appropriate actions. A series of supplier feedback sessions and engagement with supply partners has resulted in the revision of DFID’s standard contract terms and conditions as well as the commercial cost template. The Strategic Relationship Management (SRM) programme provides a robust platform for strategic discussion and performance management at portfolio level with DFID’s strategic suppliers. Open for Business events across the UK have helped local businesses understand DFID’s processes and encouraged them to compete for DFID business.

These actions have enabled DFID to listen to all sectors within the market, not only the large players. By engaging with small and medium enterprise (SME) suppliers without the larger suppliers present, it is enhancing its understanding of challenges specific to smaller suppliers.

We saw evidence that the change in contract terms and the supplier engagements have already had positive effects:

- In 2018-19, DFID increased its overseas bidders from 13% to 20%.

- Total bids per OJEU contract are up to 3.91, close to the target of 4.

- A total increase in bidders in 2018-19 by 39% from the previous year.

Recommendation 2: Accelerate the timetable for acquiring a suitable management information system for procurement, to ensure that commercial decisions are informed by data

The Procurement 2 review found that DFID was slow to source and implement a new management information system, hampering its ability to generate the data needed to improve its procurement and contract management. DFID accepted the recommendation to accelerate this process.

DFID now has a new information management tool: a business intelligence suite, using best practice software, enables effective information gathering through a series of dashboards available to all DFID users. These dashboards cover all available information on bill payments, governance, expenditure, company checks etc in a user-friendly manner. The dashboards track key performance indicators (KPIs), metrics, and other key data points relevant to the business, and present complex data sets through at-a-glance visualisations of current performance. This is a major step forward in DFID’s ability to make informed decisions and track performance.

While this is a strong response to ICAI’s recommendation, it is hampered by the lack of data on grant funding. Grants are currently outside the remit of the management information system, thus diluting what would otherwise present a rich information picture.

Recommendation 3: Instigate a formal contract management regime, with appropriate levels of training and senior management support

The review found significant weaknesses in DFID’s contract management capability, noting that DFID was overly reliant on formal contract amendments to adjust programme activities and outputs and that there was a lack of appropriate senior-level support, training and guidance for staff on contract management. DFID accepted ICAI’s recommendation. It has begun to create new policies and procedures for contract management, but has failed to implement these, partly due to a lack of support from the top management within the department, resulting in insufficient budgetary resources.

So far, only 260 DFID staff have been registered for the Cabinet Office’s Contract Management Capability Programme (CMCP) foundation level online training. Forty-two staff have undertaken the assessment and have been accredited. DFID recognises that this is far from enough. The department had not yet achieved the threshold for a ‘good’ rating on a June 2019 contract management competency metric due to its lack of progress in CMCP training and accreditation for DFID programme managers.

The most senior qualified commercial officer in the department still only sits at the third tier of management, and we did not see evidence that those at the second or first tier understand the risks of poor contract management. None of the senior responsible officers (SROs) who have received CMCP training have attended higher-level (practitioner or expert-level) training in contract management capability.

This lack of an effective contract management regime and proper training has demonstrable negative effects on programming, as evidenced in our original review.

Conclusion

Two of ICAI’s recommendations have been addressed in a timely manner. Regular reviews with consultation on terms and conditions, as well as appropriate management information tools, regimes and techniques, are being applied and embedded within DFID. Actions taken on terms and conditions, and in particular on management information, will greatly assist in making DFID, and the future Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, a more informed buyer.

However, positive action in response to these two recommendations will not have a significant impact on overall performance without a formal contract management regime. Without this foundation, poor contract management will continue to pose risks to programming results. We therefore consider the overall response to the recommendations as inadequate and will return to the issue of contract management again in next year’s follow-up exercise.

DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments

Adequate

DFID has made notable progress on all of ICAI’s recommendations, despite stretched human resources. While much remains work in progress, the direction of travel is largely positive.

ICAI published its review of DFID’s transport and urban infrastructure investments in October 2018. The review was scored green-amber, acknowledging DFID’s good performance on strategic approach and supporting multilateral finance, but noted a mixed record in the delivery of bilateral programmes. It also raised concerns about multilateral oversight and highlighted challenges in engaging China on infrastructure. The review made four recommendations.

Table 6: ICAI’s recommendations and the government response

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| In the continuing development of its infrastructure strategy and guidance, DFID should address the need for the following: • a more rigorous approach to project selection and clear expectations around economic analysis, with a range of tools and approaches • a strong focus on identifying and addressing governance and market failures that inhibit sustainable infrastructure development •realistic timetables and how to manage investments lasting beyond a single programme cycle •stronger programme supervision and risk management processes • a more systematic approach to enhancing impact on poverty reduction and ensuring the inclusion of women, people with disabilities and marginalised groups, including monitoring intended and unintended impacts on target groups. | Accepted |

| When funding infrastructure through multilateral partners, DFID should ensure that there are adequate safeguarding systems and the capacity to implement them in place at country level (including in national counterpart agencies), and verify that this remains the case throughout the life of the programme. | Accepted |

| To improve its ability to manage complex transport and urban infrastructure programmes, DFID should make more use of staff from regional departments and centrally managed programmes to supplement capacity in country offices. This might include deploying additional experts during the design and inception phases of new programmes, to help build working relationships with national stakeholders, and providing ‘over the horizon’ support throughout the life of the programme on issues such as land acquisition and safeguarding. | Accepted |

| DFID should clarify how it will work with China and other new donors on infrastructure finance, and prioritise helping partner countries become more informed consumers of infrastructure finance. | Partially accepted |

Recommendation 1: Strengthen project selection, analysis, supervision and risk management. Address governance and market failure, unrealistic project timeframes, and poverty and inclusion

The ICAI review highlighted a range of concerns about DFID infrastructure projects, including the varied depth and quality of economic analysis in business cases, inconsistent approaches to supervision, risk and analysis of infrastructure deficits and their causes, unrealistic assumptions about implementation timelines and partner capacity, and limited emphasis on targeting poor communities. DFID accepted the recommendation addressing these issues and has pursued a number of actions to improve the analytics and guidance underpinning project selection.

DFID is in the final stages of producing a SMART guide on infrastructure and has strengthened its guidance for investment decisions in the Overseas Territories. However, we found little progress in improving the economic appraisal of projects.

DFID has recently concluded work on an urban handbook, providing guidance on how to respond to governance and market failure issues that constrain infrastructure projects. DFID also noted that the delayed successor to the Infrastructure Cities and Economic Development Facility will include a focus on issues such as inadequate infrastructure governance, policy and planning.

A new seven-year land programme has recently been approved. However, judged on the basis of recent projects approved by DFID, five-year funding cycles remain the norm. This is despite the fact that major infrastructure projects generally require a longer implementation period due to their complexity and the demands of processes such as local consultation.

A stronger approach to addressing inclusion in infrastructure programmes has emerged since ICAI’s review. DFID’s new disability helpdesk has been active in responding to requests for support from infrastructure projects and the reorganisation of the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG) has helped strengthen DFID’s emphasis on gender and safeguarding.

Recommendation 2: Strengthen oversight of safeguarding policy and practice by multilaterals

A significant share of UK aid for infrastructure is overseen by multilateral organisations. ICAI’s review was concerned that multilateral partners often lacked adequate environmental and social safeguard systems at the national level, and that DFID had not worked actively at the country level to improve their application. DFID accepted the recommendation, but stated it was already implementing a range of measures dealing with ICAI’s concern.

DFID remains engaged in supporting the implementation of the World Bank’s new Social and Environmental Framework, which the department was influential in developing. However, we did not see evidence that it has enhanced its role in monitoring the capacity of multilaterals at central levels to implement safeguards.

Since the ICAI review, DFID has developed new guidance for staff working with multilaterals, which aims to ensure that they consider the adequacy of safeguarding standards and procedures as part of their decision to support (or continue supporting) trust funds managed by multilaterals. While we welcome this guidance, its application is too limited: using the guidance is voluntary, and it provides limited advice on how and what due diligence should be carried out.

DFID has worked actively with multilaterals to strengthen their safeguarding policies against sexual abuse, exploitation and sexual harassment, through its organisation of the October 2018 Safeguarding Summit and its follow-up process. DFID’s Safeguarding Unit has worked with infrastructure advisers to develop a technical tool to identify and mitigate safeguarding risks in infrastructure programmes.

Recommendation 3: Make more use of central expertise to support country-level infrastructure programmes

The ICAI review identified concerns about whether capacity from DFID regional departments and centrally managed programmes was being adequately utilised to support challenging country-level programmes. DFID accepted the recommendation to address these issues, but did not identify any new measures to act on it.

DFID’s infrastructure cadre have been stretched over the past year, due to some staff being reassigned to the Africa Investment Summit and the UK’s Infrastructure Commission or redeployed to other departments to support Brexit planning. However, in response to long-term staffing constraints, DFID has recently appointed three new senior regional infrastructure advisers as a result of the UK’s Africa strategy.

Since the ICAI review, the Head of Profession has also been preparing a staff competency framework and a process for monitoring competencies across the cadre, so as to better address gaps in expertise and knowledge through future recruitment. In essence, DFID has continued to try to maximise the impact of its relatively few staff.

Recommendation 4: Engage more effectively to ensure partner countries benefit from infrastructure investments made by China and other emerging donors

The ICAI review noted that the rise of emerging economies as major infrastructure investors has created both opportunities and risks for developing countries. DFID partially accepted the recommendation to engage more actively with China and partner countries to ensure that risks are mitigated and opportunities pursued.

Information shared by the UK government during the follow-up exercise shows that collaborations with China on infrastructure development issues are expanding, both through international forums (such as the G20 and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) and country-level activities (especially in East Africa and through PIDG). For example, in October 2019, DFID supported an initiative where the British Chamber of Commerce for Kenya, the Kenya-China Economic Trade Association and the Kenya Private Sector Alliance signed a memorandum of understanding to stimulate investments in strategic sectors like infrastructure.

However, there is limited information on the substance of these collaborations with China and little analysis of how such collaborations support country partners and development outcomes. DFID and the broader UK government have a multifaceted and evolving relationship with China. Since China’s Belt and Road Initiative is so prominent in many of DFID’s priority countries, there is an ongoing need to carefully monitor potential trade-offs between commercial, trade and developmental interests at policy, influencing and programme levels.

Conclusion

DFID’s work on infrastructure faces significant challenges, due to its complex nature and stretched human resources. Within this context, many improvements have taken place since the publication of ICAI’s review in 2018. DFID has been developing increasingly sophisticated approaches to programme design and delivery. New guidance material and tools have helped the department manage infrastructure programme challenges, including ensuring consideration of the impact of its infrastructure investments on the poorest and most vulnerable.

However, efforts to improve economic appraisal of projects have been limited. Gaps remain in the guidance material available, and sustainability of results is a concern due to limited project timeframes and delays in initiating successors to major centrally managed programmes. We also found an ongoing need to carefully monitor potential trade-offs between commercial, trade and development interests in engaging China on infrastructure cooperation.

Assessing DFID’s results in maternal health

Adequate

DFID’s response has been comprehensive. The changing shape of its strategy and programming on maternal health is already evident. DFID reacted swiftly to one of ICAI’s central concerns: how the department estimated and reported its results. However, initiatives are at an early stage and it will be some time before their full scope and influence are evident. It will be crucial to keep the momentum and to publish the delayed Ending Preventable Deaths Action Plan and Health Systems Strengthening Position Paper.

ICAI published its review on DFID’s results in maternal health in October 2018. The review noted that DFID programmes had expanded access to family planning and some maternal health services. However, its amber-red score was based on the conclusion that a renewed effort was required to reach young women and girls and to generate lasting impacts on quality of care and maternal health outcomes. It also noted its concern over the model used by DFID to back up its claims of “maternal lives saved” through DFID-funded interventions. The review’s five recommendations were all accepted by DFID.

Table 7: ICAI’s recommendations and the government response

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| As part of its commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), DFID should develop a long-term approach to improving maternal health, planning through to 2030 in focus countries with high maternal mortality. These plans should focus on improved quality and continuity of care, cross-sectoral interventions and efforts to empower women and girls. | Accepted |

| DFID should clarify its approach to health systems strengthening, prioritising improvements in the availability and accessibility of good quality, respectful care for women and their babies. | Accepted |

| DFID should directly monitor the impact of its sexual, reproductive and maternal health services programmes on adolescents and the poorest women. This means including design features in programmes that target adolescents and the poorest women, monitoring whether they are effective and adjusting course where they are not. | Accepted |

| When using models to generate outcome data, DFID should test its assumptions and triangulate its results claims using other quantitative and qualitative data. | Accepted |

| As part of its commitment to the SDG data revolution, DFID should prioritise and invest in international and country-level efforts to gather data on the quality of maternal health services and outcomes, including disaggregated data relating to key target groups. | Accepted |

Recommendation 1: Develop a long-term approach to improving maternal health, planning through to 2030 in focus countries with high maternal mortality, focusing on quality and continuity of care, cross-sectoral interventions and empowerment of women and girls

The 2018 ICAI review welcomed the comprehensive approach to improving maternal health set out in DFID’s 2011-15 Results Framework, but found that its implementation was less balanced. Programmes, particularly on family planning, were too focused on generating short-term results, and few programmes had compelling exit strategies. ICAI therefore recommended that DFID pursue a long-term approach to investing in health and other infrastructure as well as in socio-cultural change, to maximise results in improving maternal health.

In early 2019, DFID reviewed its bilateral health programming in 18 countries in light of the ICAI review findings. Later in 2019, it began developing a new Action Plan on Ending Preventable Deaths of Mothers, Newborns and Children by 2030 (EPD). Importantly, the Action Plan will be accompanied by an internal implementation plan translating the high-level objectives into action across DFID.

The Action Plan was intended to be launched in March 2020, but was delayed due to the COVID-19 outbreak. ICAI was not shown a draft, but DFID’s description of its contents is aligned with ICAI’s recommendations. The plan focuses on a set of high-priority countries and locates DFID’s maternal health interventions within a focus on “quality health services for all”, health systems strengthening, multi-sectoral work on the wider determinants of health, and women’s and girls’ rights and empowerment. Although the EPD plan is not yet published, we saw evidence of new centrally managed programmes being developed in line with its approach.

DFID has sought to exercise global leadership on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and quality of care for women, newborns and children over the past year. Ministerial engagement has been strong, including on topics such as safe abortion where the global consensus is in danger of being rolled back due to actions by the US administration and others. The UK government reportedly pushed for SRHR and service quality to be reflected in the UN General Assembly’s political declaration on universal health coverage (SDG 3, Target 8).

This appears to be a good response to ICAI’s recommendation. However, without sight of the EPD Action Plan, its implementation plan, and related monitoring frameworks, it is hard to assess the full potential of this work to shape future government policy and programming in relation to maternal health.

Recommendation 2: Clarify the approach to health systems strengthening, prioritising improvements in the availability and accessibility of good quality, respectful care for women and their babies

The 2018 ICAI review found that DFID programmes had a limited focus on improving the quality of maternal healthcare, and that little progress had been made in developing skills in emergency obstetric and neonatal care in many of DFID’s focus countries. DFID had not yet considered how to address discrimination, neglect or abuse in maternal health services, nor fully explored the opportunities to improve access to care (particularly for poor, marginalised and young women) through community health services.

DFID has undertaken a range of actions in response to ICAI’s recommendation. New centrally managed and country programmes are being developed. For instance, in Malawi, a new health systems strengthening programme will focus on primary and community health, quality of care, and local accountability. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, DFID has been designing a new health sector programme that will focus on reproductive, maternal, neonatal and adolescent health, with a strong emphasis on community mobilisation and accountability, as well as quality of care.

DFID has pushed for a greater focus on quality of care within the Global Financing Facility and is funding the World Health Organisation (WHO) to help countries develop national quality policies and strategies. It is working with the UK Department of Health and Social Care to advance the patient safety agenda with the WHO. The new UK Partnerships for Health Systems programme (2019-2023) will support UK health professionals, including midwives, to provide voluntary technical assistance to developing countries in line with the EPD Action Plan.

DFID has taken many years to develop a Health Systems Strengthening Position Paper, to the frustration of external stakeholders including UK CSOs. DFID told us that a draft of this paper was due for consultation but had been paused first due to the 2019 general election and then by the COVID-19 emergency. The plan at the time of writing was to publish the paper together with the EPD Action Plan.

Overall, DFID has responded positively to this recommendation, although much of the work on quality of care is at an early stage. The evident collaboration across the UK government and between teams working on SRHR, violence against women and girls and safeguarding is promising. DFID has also developed good new guidance and learning resources on SRHR for its staff, placing new emphasis on respectful and dignified care. As we have not seen the draft Health Systems Strengthening Position Paper, we cannot assess its relevance to maternal health programmes.

Recommendation 3: Directly monitor the impact of sexual, reproductive and maternal health services programmes on adolescents and the poorest women, ensuring through programme design and monitoring that adolescents and the poorest women are included

The ICAI review found that DFID did not track whether its programmes reached its core target groups of young women aged between 15 and 19 and the poorest 40%. Reaching adolescents proved a particular challenge, and DFID’s own lesson learning indicated a need to expand programming to include both girls and boys aged between 10 and 14.

New centrally managed and country-level sexual health and family planning programmes now have a stronger focus on adolescents and the poorest women, with performance tracked through logframe indicators. For instance, the Women’s Integrated Sexual Health (WISH) programme (£238 million, 2018-2021), which was under procurement during the ICAI review, has a strong focus on young, poor and rural women and girls, includes efforts to improve quality of care, and seeks to engage men and boys. Five key performance indicators (KPIs) are linked to results-based funding and one relates to reaching young people under 20, against which the programme is over-performing. A third-party monitor has been engaged to verify results reporting, capture learning and support adaptation.

The new Malawi family planning programme, Tsogolo Langa (£50 million, 2018-2024), includes targeted interventions to reach young people aged between 10 and 24 with sexual health services. Indicator data will be disaggregated by location, age group (10-14 and 15-19), and disability.

DFID’s response to this recommendation is at an early stage. New programmes include interventions targeted at adolescents and poorer women, and programme documents suggest that monitoring data will be disaggregated. For most of these programmes, it is too early to see any results. However, data from the WISH programme is promising, and its strong emphasis on learning and knowledge sharing should enhance future government efforts in this area.

Recommendation 4: When using models to generate outcome data, DFID should test its assumptions and triangulate its results claims using other quantitative and qualitative data

The ICAI report found that the model DFID used to estimate departmental results on “maternal lives saved” rested on assumptions that were not robust. We considered that DFID should make more use of qualitative information, such as data on quality of care, and feedback from client surveys, community scorecards and local accountability bodies, to test and triangulate its quantitative data and results estimates.