ICAI follow-up: UK aid to refugees in the UK

Introduction

1.1 Every year the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) returns to the reviews we published in the previous year’s cycle to follow up on the steps the government has taken in response to our recommendations. This process is a key link in the accountability chain, providing Parliament and the public with an account of how well government departments have responded to ICAI reviews.

1.2 ICAI’s rapid review of UK aid to refugees in the UK was published in March 2023 and looked at the UK’s spending on ‘in-donor refugee costs’. These are particular costs associated with supporting refugees and asylum seekers who arrive in a donor country which can be counted as official development assistance (ODA) under international aid rules as established by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The rationale is that supporting refugees with basic services and accommodation is a form of humanitarian assistance, wherever they are located, and can therefore be reported as aid. The follow-up assessment of the government’s response to ICAI’s six recommendations is presented below.

ICAI’s March 2023 review of UK aid to refugees in the UK detailed how, in 2022, soaring costs charged to the aid budget by the Home Office and other government departments to support refugees and asylum seekers in the UK caused major disruption to the international development programme managed by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development

ICAI’s March 2023 review of UK aid to refugees in the UK detailed how, in 2022, soaring costs charged to the aid budget by the Home Office and other government departments to support refugees and asylum seekers in the UK caused major disruption to the international development programme managed by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development

Office (FCDO). Because the UK, uniquely among major donors, sets a ceiling for its annual aid budget (currently 0.5% of gross national income), more aid spent by the Home Office in the UK means less available for FCDO to spend in developing countries. In 2022, in-donor refugee costs took up almost one-third of the UK’s total aid budget. Since FCDO is the “spender and saver of last resort” to ensure the aid spending commitment is met, the sharp increase in the Home Office’s official development assistance (ODA) spending, mainly on hotel accommodation for asylum seekers, forced FCDO to put its own programming on hold, despite the risk to partnerships and the many people around the world who rely on UK development and humanitarian aid. ICAI’s review also found that FCDO was hampered in its financial planning due to the unpredictability of the Home Office’s ODA spend.

Returning to the topic a year later, ICAI’s follow-up shows that, far from reducing as costs of Ukrainian and Afghan refugee schemes went down, in-donor refugee costs have continued to increase, from £3.7 billion in 2022 to £4.3 billion in 2023. Again, hotel costs are the main drivers of the increase, but other categories of spend, both by the Home Office and by other departments, also remain very high. Despite various Home Office initiatives to move away from hotel accommodation, almost exactly the same number of asylum seekers were accommodated in hotels in December 2023 as in December 2022 (more than 45,700 people), although the Home Office reported a drop in the first quarter of 2024. Value for money concerns have not diminished: the per person per night costs are fluctuating but have not reduced, while standards of support do not seem to have tangibly improved.

The introduction of some flexibility into the 0.5% aid commitment, better communication from the Home Office to FCDO, and improved planning and risk management by FCDO even in the context of some continuing unpredictability in the Home Office’s spend, have played some role in helping FCDO cope better with the stresses created by in-donor refugee costs. But the underlying factors wreaking havoc on FCDO’s development partnerships and spending commitments in 2022 have not been tackled. The fact that gross national income (GNI) for 2023 was considerably higher than forecast is one of two significant factors in smoothing out the impact on FCDO, the other being an additional £2.5 billion of ODA resources over 2022 and 2023 provided by the Treasury in response to the unprecedented spend by the Home Office.

The UK government has not revisited its methodology for reporting in-donor refugee costs with the aim of producing a more conservative approach. The UK appears to be taking a maximalist approach to reporting in-donor refugee costs compared to most, if not all, large donors – reporting anything that could possibly be reported according to ODA eligibility rules. We also find that its pricing of certain costs remains opaque.

While we saw some improvements in how the Home Office manages its large-value asylum accommodation and support contracts (AASC), value for money and safeguarding concerns continue. There are no signs yet that the Home Office has found a route out of short-term crisis management towards longer-term solutions for asylum accommodation.

The Illegal Migration Act (IMA) is an important unknown piece in this puzzle: if it is fully implemented, in-donor refugee costs will drop dramatically. Meanwhile, the current situation for the cohorts of asylum seekers who arrived by irregular routes (and therefore would fall under the IMA) after 8 March 2023, when the Illegal Migration Bill was introduced to Parliament, and after 20 July 2023, when it received royal assent and became an Act, is full of contradictions. The Home Office has allowed this cohort of arrivals to enter the asylum claims system and is reporting their accommodation costs as ODA, but it is not progressing their applications as it is assumed that they will be deported. This approach is untenable as a new backlog of cases in limbo is building up fast, at considerable human and financial cost.

In-donor refugee costs continued rising in absolute terms in 2023, to £4.3 billion or 28% of all UK ODA, despite value for money risks and a lack of connection to the UK’s international development objectives

1.3 ICAI’s review of UK aid to refugees in the UK found that the system of managing the aid spending target means that the Home Office and other departments incur costs but FCDO in effect has to take the financial hit. The Home Office is accountable to HM Treasury for its ODA spend, but it does not have a set ODA budget for in-donor refugee costs. There is no limit to the ODA costs it incurs for the accommodation of asylum seekers, and the effect of this spend is not felt elsewhere in the Home Office, but by FCDO as “spender and saver of last resort”, severely affecting the latter’s ability to plan and execute its international development programme. This creates perverse incentives and value for money risks.

1.4 Despite the absence of reference to the use of aid to pay for the costs of asylum seekers and refugees in the UK in the 2022 International Development Strategy, this had become the largest category (‘bilateral sector’) of ODA. In 2022, the UK spent £3.7 billion on in-donor refugee costs. This was 29% of all UK aid that year. It was also a sharp rise from 2021, when in-donor refugee costs were £1.1 billion or 9% of all UK aid.

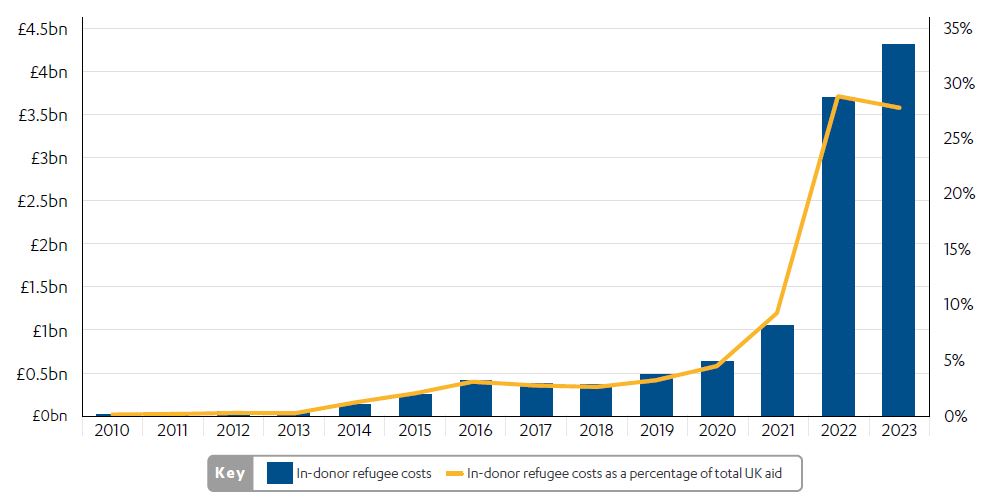

1.5 There is no mention of in-donor refugee costs as a priority in the 2023 White Paper on International Development either, but it is now clear that the rise in these costs continued in 2023, with £4.3 billion, constituting 28% of all UK aid last year, used to cover in-donor refugee costs. Figure 1 below shows the trend in UK in-donor refugee costs since 2010.

Figure 1: UK spending on in-donor refugee costs, in absolute figures and in proportion to total aid, from 2010 to 2023

Source: OECD Query Wizard for International Development Statistics, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, n.d., link and Statistics on International Development: Provisional UK Aid Spend 2023, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, link.

The Home Office’s use of hotel accommodation for asylum seekers continues to be the main driver of the rise in in-donor refugee costs, but other departments have also increased their spend

1.6 The Home Office is responsible for more than two-thirds of all in-donor refugee costs: it reported an estimated £2,937 million of ODA for 2023, mainly for asylum seeker accommodation (£2,489 million), the vast majority of which covered hotel accommodation (which is very expensive compared to more appropriate dispersed housing in the community). The ODA spending is only part of the Home Office’s hotel costs because costs are only eligible to be considered as ODA in the first 12 months: in October 2022, the department reported total spend (ODA and non-ODA) on hotels at £6.8 million per day.4 In October 2023, the Home Office reported this cost as £8 million per day, while in March 2024 the department reported it as £8.2 million per day (see discussion under Recommendation 3). In a Supplementary Estimates Memorandum for 2023-24, provided by the Home Office in February 2024, the department noted a further “£4 billion of funding provided to alleviate pressures within the asylum system” and “£528.2 million to support the Afghanistan Resettlement Schemes”.

1.7 Other government departments also have high levels of in-donor refugee costs in areas such as health, primary education, housing and social benefits. In 2023, other government departments than the Home Office reported a total of £1,251 million in-donor refugee costs, while £109 million of spending on asylum seeker and refugee support by devolved administrations was also reported as ODA. We discuss this spend in more detail under Recommendation 2 below, and Tables 1 and 2 in that section provide, respectively, a breakdown of in-donor refugee costs per department and within the Home Office’s spending categories.

While disruptions to FCDO’s aid budget were eased in 2023, helped by unexpected high growth in GNI, many of the underlying problems remain unresolved

1.8 ICAI’s original rapid review found that soaring in-donor refugee costs in 2022 caused major disruptions to the UK aid programme. The scale and unpredictability of the spending on in-donor refugee costs caused FCDO to ‘pause’ all ‘non-essential’ ODA spending for four months. Forward financial planning became, in the words of Philip Barton, permanent under-secretary at FCDO, “incredibly difficult”, while the Minister of State for Development and Africa Andrew Mitchell noted at the very end of the year that he still did “not know what the full extent of the Home Office demands [on the 2022 aid budget] will be”. This dire situation was somewhat eased in November 2022, when in the Autumn Statement the government allocated £2.5 billion additional ODA funding over two years (2022-23 and 2023-24). That additional funding, combined with growth in GNI far beyond what was forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), has led to a less severe effect in 2023 resulting from this large diversion of aid spending away from UK development priorities.

1.9 The original review noted that the Home Office was facing a critical shortage of accommodation for asylum seekers and refugees, leading to the widespread use of hotels – a trend that continued in 2023. The review found that the short-term crisis-driven response and lack of planning for long-term solutions were contributing to the spiralling of costs. ICAI also noted serious shortcomings in the Home Office’s management of the large-value asylum accommodation and support contracts (AASC) and raised concerns about the department’s insufficient oversight of safeguarding, particularly in hotel settings. These issues are discussed under Recommendation 3 below, which concludes that although new initiatives such as the Large Sites Accommodation Programme and strengthening of the commercial management team overseeing AASC took place in 2023, we did not see results from these in the form of reduction of the Home Office’s reliance on hotel accommodation in 2023.

1.10 The first quarter of 2024 has seen the closure of up to 100 of the approximately 400 hotels used by the Home Office in October 2023. According to a March 2024 Home Office announcement, around 36,000 asylum seekers were in hotel accommodation in March 2024, a decrease of around 10,000 since December 2023. However, the same announcement reported the cost of using hotels per day at £8.2 million, which is higher than in October 2023 (£8 million).

1.11 ICAI’s original review made six recommendations. Unusually for ICAI reviews, the government rejected two recommendations, both related to finding ways to lessen the negative impact of in-donor refugee cost spending on the predictability, reliability and quality of FCDO’s ODA programme (Recommendations 1 and 2). For these recommendations, ICAI comments on their continued relevance since the original review was published and discusses developments over the past year, but does not score the government’s response.

Findings

| Subject of recommendation | Government response |

|---|---|

| The government should consider introducing a cap on the proportion of the aid budget that can be spent on in-donor refugee costs (as Sweden has proposed to do for 2023-24) or, alternatively, introduce a floor to FCDO’s aid spending, to avoid damage to the UK’s aid objectives and reputation. | Rejected |

| The UK should revisit its methodology for reporting in-donor refugee costs, as Iceland did, with the aim of producing a more conservative approach to calculating and reporting costs. | Rejected |

| The Home Office should strengthen its strategic and commercial management of the asylum accommodation and support contracts, both individually and as a group, to drive greater value for money. | Accepted |

| The Home Office should consider resourcing activities by community-led organisations and charities as sub-contractors in the asylum accommodation and support contracts for dedicated activities to support newly arrived asylum seekers and refugees. | Accepted |

| The government should ensure that ODA-funded in-donor refugee support is more informed by humanitarian standards, and in particular that gender equality and safeguarding principles are integral to all support services for refugees and asylum seekers. | Partially accepted |

| The Home Office should strengthen its learning and be more deliberate, urgent and transparent in how it addresses findings and recommendations from scrutiny reports. | Partially accepted |

Recommendation 1: The government should consider introducing a cap on the proportion of the aid budget that can be spent on in-donor refugee costs (as Sweden has proposed to do for 2023-24) or, alternatively, introduce a floor to FCDO’s aid spending, to avoid damage to the UK’s aid objectives and reputation.

1.12 The government rejected ICAI’s recommendation of a cap on in-donor refugee costs as a proportion of total UK ODA or a floor to FCDO’s aid spending. The strong desire of the government to avoid a repeat of what happened in 2022 meant, however, that in practice measures were taken that address some of ICAI’s concerns. These measures have been essential, considering that in-donor refugee costs have increased significantly again in 2023, to an estimated £4.3 billion, up from £3.7 billion in 2022. However, as the discussion in this section shows, a key reason why the impact of this spend was less severe than in 2022 was that the UK’s GNI grew by more than had been forecast by the OBR, leading to a larger ODA envelope for 2023 than planned for. It is important to note that some of the key factors causing the 2022 crisis in UK aid remain unchanged. The trend in UK in-donor refugee spend is illustrated in Figure 1 above.

1.13 As Figure 1 shows, although in-donor refugee costs have increased by £607 million from 2022 to 2023, because of an increase in GNI (to which the UK’s aid target is pegged), they have slightly decreased as a proportion of total UK aid. In 2023, according to FCDO’s provisional Statistics on International Development, published on 10 April 2024, in-donor refugee costs constituted 28% of total UK aid in 2023. It is highly likely to have remained by far the largest sector of UK bilateral spend, and is significantly larger than UK bilateral spend on humanitarian action, which was £888 million in 2023, down from £1,109 in 2022 (a decrease of 20%).

1.14 Most, but not all, of the increase in the past year comes from the Home Office’s spend, which was more than £2.9 billion in 2023, up from £2.4 billion in 2022. Costs were also up for most other departments that spend aid in this category. For instance, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) spent £249 million on in-donor refugee costs in 2023 (up from £163 million in 2022). Spending decreased somewhat for the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) and the Department for Education (DfE). A breakdown of in-donor refugee costs across UK government departments is provided in Table 1 (which is found under paragraph 1.30), while changes in departmental spending from 2022 to 2023 are discussed under Recommendation 2 below. The increase in the Home Office’s spending on asylum accommodation is discussed under Recommendation 3.

1.15 A combination of measures have been taken since ICAI’s review that go some way towards addressing the negative impact on the UK’s aid objectives and reputation that we described. These include:

- The introduction of some flexibility into the UK government’s spending commitment. For 2022 and 2023, the commitment has been to spend around 0.5% of GNI, rather than hitting 0.5% exactly. In 2022, the UK spent 0.51% of GNI on ODA, while in 2023, this was 0.58%, a more notable level of flexibility. It seems likely that flexibility will continue to be required, as it is crucial for FCDO’s ability to manage future shocks from spikes in other departments’ in-donor refugee cost spending.

- Improved cross-government communication on in-donor refugee costs and the implications of this spend on the rest of the UK ODA programme, which facilitates risk management and planning. In particular, there is a new high-level ODA board, co-chaired by the FCDO Minister of State for Development and Africa and the Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The first meeting of this board discussed in-donor refugee costs. There is stronger recognition and engagement at senior level in the Home Office regarding the impact of its ODA spend on other departments and increased Home Office resourcing of its ODA forecasting, as well as of its management of the asylum accommodation and support contracts. The latter is discussed under Recommendation 3. There are also more frequent FCDO-Home Office interactions at working level to manage in-donor refugee costs throughout the year.

- The quality of the Home Office’s forecasting of its ODA spend on in-donor refugee costs has improved. In hindsight, the middle estimate of the Home Office’s spending forecasts remained relatively stable throughout 2023 and ended up being roughly correct, but the high level of uncertainty attached to the forecasts, with a large range between the lower and higher estimate, meant that it was challenging for FCDO to plan based on these middle estimates until towards the end of the calendar year when the uncertainties started to recede. While the sharing of data has improved, FCDO is not aware of all the assumptions underpinning the Home Office’s forecasting of in-donor refugee costs.

- FCDO’s risk management and planning has improved. This is linked to the general improvement in FCDO’s reporting and planning over the past year, including the resumption of forward spending plans. In July 2023, FCDO published its annual report and accounts, which included planned ODA allocations for 2023-24 and 2024-25, split by country. It also published country development partnership summaries, including indicative budgets for 2024-25.

- FCDO is using all the levers at its disposal to ‘push and pull’ funding between the calendar and financial year to reach the spending target without going back on its development partnership commitments.

- This has been helped by the injection of £2.5 billion in additional funds over two financial years provided by the chancellor in the 2022 Autumn Statement, which has helped to smooth FCDO’s planning in 2023 when faced with a further increase in in-donor refugee costs to £4.3 billion.

- Since the ODA spending target is linked to GNI, the fact that GNI has increased well above what was forecast has softened the impact on FCDO’s aid programming considerably.

1.16 These measures add up to a significant improvement from 2022, the most important of which is the introduction of some flexibility into the ODA commitment. This is supported by FCDO’s return to regular published forward planning. It is, however, crucial to recognise the role of the unexpected growth in GNI well beyond the OBR forecast in allowing FCDO to protect its core development partnerships and spending commitments in 2023. This means that more robust measures are still needed to address the underlying factors that wreaked havoc on FCDO’s development programme in 2022, since above-expected GNI growth may not always come to the rescue.

1.17 The number of asylum seekers arriving in high-income countries in Europe and North America continues to be high, and it seems unlikely this will change in the near future, considering the many conflicts and humanitarian crises that have led to very high levels of displacement across the world.15 Planning needs to keep this reality in mind. However, as discussed in ICAI’s review, the costs could be lessened dramatically if the asylum processing backlog were to be reduced and a longer-term plan enabling dispersed accommodation in the community were to be produced and implemented.

1.18 In addition, in the case of the UK, the largest uncertainty regarding how large its future in-donor refugee costs will be is the Illegal Migration Act (IMA). The Act received royal assent on 20 July 2023 but key aspects of it are not yet in force. ICAI’s update on the IMA, published in September 2023, found that the “effect of the Act, if implemented, would be that individuals arriving irregularly or ‘in breach of immigration control’, as the Act states, are no longer entitled to protection by the UK as refugees or asylum seekers. In ICAI’s assessment, any spending on individuals who, due to their irregular arrival, are barred from receiving asylum in the UK, would therefore not meet the second of the OECD-DAC clarifications on in-donor refugee costs – which describes an asylum seeker as ‘a person who has applied for asylum and is awaiting a decision on status’.”

1.19 For now, the Secretary of State’s duty to make arrangements to remove people who fall under the IMA is not in force. The status of the cohort of asylum seekers who have arrived after 20 July 2023 by irregular routes (and therefore would fall under the IMA) is not entirely clear. The situation is also unclear for those who arrived between 8 March 2023, when the Illegal Migration Bill was introduced to Parliament, and 20 July 2023, when it received royal assent and became an Act. They are hosted within the existing asylum accommodation and support system (mainly hotels) and, for now, the Home Office considers its accommodation and support costs for this group of asylum seekers to be eligible as in-donor refugee costs. If the IMA is fully enacted, this would change and the UK’s in-donor refugee costs would drop dramatically. If detention facilities are used before an asylum seeker is removed, this type of accommodation would not be ODA-eligible. But even if not detained, if the IMA were to be fully in force, those who fall under its provisions would be barred by law from receiving protection in the UK. Accommodation and support for this group would then no longer be ODA-eligible as it is not protection-related.

1.20 There is already ambiguity around this question from the Home Office, in that the Home Office has allowed asylum seekers arriving by irregular means after 20 July 2023 to enter the asylum claims system but is not progressing their applications. In ICAI’s view, this limbo state is untenable both from a humanitarian perspective and from a financial one:

- Humanitarian imperative: Leaving people for months and potentially years living with profound uncertainty about their future, most of whom (according to previous Home Office asylum statistics)17 would end up receiving refugee status in the UK if their claims were to be processed, is not in line with humanitarian principles. If the IMA is not fully in force, asylum applications should be processed within a reasonable timeframe, not left until an unknown future date at which time the Act may become enforced.

- Financial imperative: A new backlog of arrivals after the IMA was brought as a bill before Parliament in March 2023 has been building up fast. More than 55,000 people arrived in the UK and entered the asylum claims system between March and December 2023. Most arrived irregularly, meaning that their applications are in limbo due to the IMA. Most of these people have also entered the asylum accommodation system while waiting indefinitely, staying mainly in costly hotel accommodation, which is funded by ODA for the first 12 months. The decision to leave this growing number of asylum seekers in limbo thus has a considerable financial cost, which is increasing by the day.

1.21 ICAI’s original review urged the government to take a more conservative approach to reporting, as asked for by the OECD-DAC in its clarification of the reporting rules. ICAI did not argue in its review that the costs included by the UK as in-donor refugee costs were ineligible to count as ODA. Instead we argued that it was not necessary – or indeed “conservative” – for the government to do so. We note that the UK had until 2010 taken the position within the DAC of being critical of the reporting category of ‘in-donor refugee costs’. The government’s response to ICAI’s review was, in contrast to this earlier stance, that everything that can be reported as in-donor refugee costs should be reported as such. This continues to be the UK government position, as verified during this follow-up assessment.

1.22 ICAI’s original review noted that almost all donors reporting their aid spending to the OECD increased their in-donor refugee costs reported as ODA in 2022, due to a combination of high levels of asylum seeker arrivals and the hosting of Ukrainian refugees, around four million of whom were hosted in EU countries under an EU-wide temporary protection directive. However, as a proportion of its total ODA, the UK’s in-donor refugee costs were twice as high as the OECD donor average (28.9% compared to a 14.4% average).

1.23 We do not yet have the OECD average for 2023, but expect the comparison to look similar to 2022. The arrival of asylum seekers continues to be high not only in the UK, but across Europe and the US, with levels in Europe similar to those of the previous spike in 2015-16. In the 27 countries of the EU, 1.1 million new asylum applications were lodged in 2023, with more than 330,000 new applications in Germany, 167,000 in France and 162,000 in Spain. In the UK, there were 84,425 new asylum applications in 2023 (main applicants and dependants), which is slightly reduced from 2022, but remains at a higher level than seen in two decades. In addition, the number of Ukrainian refugees in both the UK and the EU continued to rise in 2023, with 201,400 Ukrainian nationals registered on one of the UK’s tailor-made humanitarian visa schemes as of March 2024, and 4.3 million Ukrainian refugees receiving temporary protection in EU member states as of January 2024.

1.24 A key reason for expecting UK in-donor refugee costs to continue to be proportionally higher than the OECD average is the high cost of the Home Office’s hosting of many asylum seekers in hotels and other expensive initial accommodation for prolonged periods of time. This will be discussed under Recommendation 3 below. However, another reason is that the UK’s methodology for identifying, calculating and reporting costs has not changed, and remains more expansive than it needs to be, as noted in ICAI’s original report.

1.25 The government rejected ICAI’s recommendation to revisit its methodology with the aim of producing a more conservative approach. Its response to ICAI’s recommendation noted that: “Since the introduction of schemes such as the Afghanistan Citizen Resettlement Scheme and Ukraine Visa Schemes, all departments reporting in-donor refugee costs have developed their methodologies to incorporate new costs in line with the ODA rules. Details of the methodologies used by spending departments will be published […] in autumn 2023. This report will demonstrate that the methodology is fit for purpose while highlighting areas for potential development.” The report was published in September 2023.

1.26 We note that the objective of the September 2023 report was to demonstrate that the UK methodology was fit for purpose, but not to assess whether it is taking a conservative approach to reporting, as asked for by the OECD-DAC in its clarification of the reporting rules.

1.27 At the same time, it remains unclear how the UK has priced some of its costs for certain categories of spend. ICAI’s original review noted that the “UK government’s decision-making on what to include as in-donor refugee costs and how to price it is opaque, which means that: (i) there is a need for better monitoring; and (ii) it is currently difficult to assess if estimated costs are realistic and conservative”. This has not changed. The September 2023 report on the UK methodology was not intended to shed light on how components of in-donor refugee costs were priced and therefore did not address pricing issues highlighted in ICAI’s review (see paragraphs 1.31-1.38 for further discussion of this subject).

1.28 The combination of a maximalist approach to finding ODA-eligible spend to contribute to UK in-donor refugee costs and the lack of transparency about decisions on how to price those costs means that the UK approach to reporting in-donor refugee costs cannot be seen to be conservative. The UK is better than many donors at providing a public account of how it calculates in-donor refugee costs, but the bar is low.

1.29 ICAI shares with the DAC, the body which makes the rules about the use of aid, the concern that the reporting of significant amounts of in-donor refugee costs risks undermining the integrity of the concept of ODA. ODA has as its primary aim the benefit of developing countries, but this type of spending is not good value for aid money. The DAC has reiterated its concern since ICAI’s review was published, both in general and in the specific case of the UK:

- The DAC mid-term peer review of the UK, published in March 2024, noted: “The International Development Act (2002) continues to require that ODA must be ‘likely to contribute to a reduction in poverty.’ However, varied understanding of ODA eligibility among other ODA-spending departments, implications of the merger [to form the FCDO in 2020] and capacity constraints has made delivering on this challenging and the completeness and coherence of the United Kingdom’s statistical reporting to the OECD has declined. Meeting the DAC’s commitment to take a conservative approach to counting in-donor refugee costs and building understanding and capacity on ODA standards and statistics will be important.”

- Carsten Staur, the chair of the DAC, wrote after OECD data showed a trebling of in-donor refugee costs among DAC donors from 2021 to 2022 that: “In-donor refugee costs are a challenge for donor reporting, as various costs are incurred at different levels of government (state, region, municipality) and in various public sector institutions. The OECD Development Cooperation Directorate (DCD) has been working closely with member states to validate each country’s processes and encourage them to share their models of calculation, to increase transparency and mutual accountability. The Secretariat has also encouraged DAC members to be conservative, whenever they make their assessments – not to overreport, but to act on the side of caution.” The DAC Chair noted that: “Even though these costs can be reported as ODA, this does not mean that a country must do so”, and donors also have the “option of deciding that such costs are additional to their planned development budgets”.

1.30 Table 1 below shows the in-donor refugee cost spending in 2022 and 2023 per government department. While the Home Office’s spend is primarily related to the accommodation and support it provides to asylum seekers, many of the costs incurred by other government departments relate to the humanitarian visa schemes for Ukrainian refugees and the Afghanistan Citizen Resettlement Scheme. All the costs incurred by DLUHC are linked to the Homes for Ukraine scheme and include tariffs for local authorities and thank-you payments to those hosting Ukrainian refugees in their homes.

Table 1: UK in-donor refugee costs per government department, 2022 and 2023

| Department | Final ODA spend 2022 | Provisional ODA spend 2023* |

|---|---|---|

| Home Office | £2,382 million | £2,937 million |

| Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities | £524 million | £466 million |

| Department for Health and Social Care | £274 million | £330 million |

| Department for Education | £218 million | £179 million |

| Department for Work and Pensions | £163 million | £249 million |

| Other in-donor refugee costs | £109 million | £109 million |

| HM Revenue & Customs | £21 million | £28 million |

| Total UK in-donor refugee costs | £3,690 million | £4,297 million |

* Figures for 2023 are from the accompanying data tables to the Provisional Statistics on International Development, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, 10 April 2024, link.

1.31 The Homes for Ukraine scheme remains an example of the lack of transparency in determining ODA-eligible costs. ICAI’s original review noted “the lack of information around the government decision-making on what aspects of the Homes for Ukraine scheme should be classified as ODA and at what funding level”. We find that the September 2023 methodology update does not address this concern, but merely states that costs associated with Ukrainians on temporary protection visas are ODA-eligible and that funding for “the provision of shelter and temporary subsistence” is eligible. These statements are both true, but the issue at stake is how DLUHC arrived at the particular funding level of 69% of tariffs to local authorities being classified as ODA and how it checked that indeed 69% of funds were spent on ODA-eligible activities, considering the broad descriptions of how local authorities may use the funding. The government decided to reduce the tariffs to local authorities from the original £10,500 to £5,900 per person from January 2023, with 53% of the tariff ODA-eligible. But there is no explanation in the September 2023 methodology report of the basis for the reduced figure. The report states that “[s]ubsequent and continued analysis of spend confirms expected usage and the proportion of ODA eligibility applied” without any detail on why 69% of £10,500 or 53% of £5,900 would be a suitable proportion allocated as ODA.

1.32 Based on the September 2023 methodology report and the reported cost by UK government departments, ICAI conducted a comparison with the published methodologies of a selection of other European donors. The results of this analysis – caveated by the fact that none of the methodologies are detailed – is that although the types and levels of cost reported by the UK can also be found in the reporting methodologies of some or many of the other donors, few if any other donors with published methodologies report all of these costs at the same level that the UK does.

1.33 One example of this is the reporting of child benefit as ODA. HM Revenue & Customs, which spent £28 million on in-donor refugee costs in 2023 (up from £21 million in 2022), has decided to count as ODA child benefit for all Ukrainian and Afghan families who claim it for children of eligible age in the first 12 months. The September 2023 methodology report describes this as in line with the DAC clarification 4 (i) ‘Other’ category. This category describes all direct expenses for temporary sustenance (food, shelter and training), and the list of ‘Other’ eligible activities are listed as:

- Basic health care and psycho-social support for persons with specific needs such as unaccompanied minors, persons with disabilities, survivors of violence and torture.

- Cash ‘pocket money’ to cover subsistence costs.

- Assistance in the asylum procedure: translation of documents, legal and administrative counselling, interpretation services.

1.34 The DAC clarifications do not mention child benefit, but it is clear from the above that if needed to cover subsistence costs, child benefit could be eligible. It is not clear, however, that the determination of 100% of child benefit for Ukrainian refugees who claim it can be characterised as a conservative approach to reporting in-donor refugee costs. First, a look at the published methodologies of other donors shows that only one other donor, Iceland, includes child benefit among its eligible costs. No other donor mentions child benefit and Italy’s methodology states that “[c]osts related to services available to all citizens are not included”. Second, while many Ukrainian refugees in the UK are in need of basic subsistence support, others are not. A survey by the Office for National Statistics from April 2023 of 3,500 respondents among visa holders under the Ukraine Family Scheme and Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme (Homes for Ukraine), showed that 61% of respondents were employed or self-employed, and many of these will be paying taxes and national insurance contributions. If ODA allocations should focus on those most in need, considering the humanitarian nature of in-donor refugee costs, it would have been a more conservative approach to charge a percentage of, rather than all, costs related to child benefit for Ukrainian refugees in the UK as ODA.

1.35 There are various items counted by the UK as in-donor refugee costs that some or many other donors do not count as such. For instance, Austria, Greece, Iceland and the Netherlands do not include administrative costs at all, while the Home Office alone charged £75 million in administration and management costs to the ODA budget in 2023 (up from £67 million in 2022). Social housing – as contrasted with the initial accommodation provided when asylum seekers first arrive in the country – is not included in ODA by the Netherlands, while Sweden stopped including compensations to local authorities for their refugee resettlement costs in its reporting of in-donor refugee costs from 2020 onwards. France and Spain do not include primary schooling as in-donor refugee costs.

1.36 Some donors have decided either to cap how much of their ODA budget can be spent on in-donor refugee costs or to report this cost separately from and additional to their ordinary aid budget – thus not cutting other aid in order to spend on in-donor refugee costs.

1.37 To conclude, ICAI disagrees with the UK government that a ‘conservative approach’ to reporting and counting in-donor refugee costs is compatible with an approach that seeks out and includes every type of cost that can be deemed to be ODA-eligible. We see this as a maximalist approach – and one that differs from those of other major donors – based on a misunderstanding of the intention behind the DAC clarifications on reporting in-donor refugee costs. The effect of this maximalist approach is that a large proportion of UK aid, 28% of all ODA in 2023, is spent in a manner that is not good value for money nor in line with UK international development strategic priorities. As a result, such a maximalist approach undermines the integrity of the ODA concept, which is about supporting development and reducing poverty in developing countries. The DAC clarifications were written with the aim in mind of protecting the integrity of the ODA concept.

1.38 It is regrettable that the UK government did not use the opportunity of its September 2023 methodology review to interrogate the reasoning around pricing and the premises for decisions on what costs to include as in-donor refugee costs. Instead, the report concluded (as had been indicated in advance in the government response to ICAI) that ODA eligibility standards were adhered to and that the methodologies used by departments were fit for purpose. This was a missed opportunity to draw the UK approach closer to the DAC donor average and in doing so to help protect the integrity of the ODA concept.

1.39 ICAI’s original review found that the Home Office had not effectively overseen the value for money of its large-value asylum accommodation and support contracts (AASC). It lacked monitoring data and up-to-date key performance indicators (KPIs) that would have enabled it to compare the cost effectiveness of different suppliers and identify scope for improvement. The Home Office accepted ICAI’s recommendation and noted that it was in line with the department’s own plans for improvements on capacity and capability, value for money, and performance management and the AASC KPIs.

1.40 Coming back to this recommendation, there has been progress on some of ICAI’s problem statements related to the commercial management of the AASC contracts. Two overarching problems remain, however, unchanged. First, efforts to move away from hotel accommodation have not yet led to reduced spending in this area. A recent investigation by the National Audit Office (NAO) showed that the cost of hotels per person per night fluctuates, ranging between £127 and £148, and that the Home Office expected to spend around £3.1 billion on hotels in the financial year 2023-24, up from £2.3 billion in 2022-23. Second, AASC, which was never meant to be used for, and is unsuitable for, procuring hotel accommodation on a large scale, continues to be used for this purpose, and the KPIs for these contracts have not changed to address this very different set of requirements since ICAI’s original review.

1.41 A breakdown of the Home Office’s in-donor refugee costs for 2023 compared to 2022 can be found in Table 2 below. We were not able to provide exactly the same categories of spend for the two years because the Home Office did not provide disaggregated costs according to type of accommodation in 2023 as requested. We therefore do not have exact ODA costs for hotel accommodation for 2023. However, combining what we know about the cost per person in hotels and the statistics on asylum seekers hosted in hotels in 2023, it is clear that most of the Home Office’s ODA cost on accommodation in 2023, as in 2022, was on hotels.

Table 2: The Home Office’s in-donor refugee costs per activity or scheme, 2022, 2023

| Home Office activity or scheme | ODA spend 2022 | Estimated ODA spend 2023 |

|---|---|---|

| Initial accommodation through Asylum Accommodation and Support Contracts (AASC), including hotels and other contingency accommodation | £1,860 million | £2,489 million |

| Asylum support, providing dispersed accommodation and cash support to adults and families | £110 million | |

| Asylum seeker travel, such as when moving to new accommodation or to attend asylum interviews | £10 million | £19 million |

| Support for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children | £130 million | £266 million |

| Children’s Panel, which advises and assists unaccompanied children through the asylum process | £2 million | £3 million |

| Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) | £180 million | £40 million |

| UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS) | £8 million | £26 million |

| Modern Slavery Victims Care Contract (MSVCC) | £12 million | £20 million |

| Administration costs, such as staff costs for processing applications for asylum support, assessing accommodation needs and managing contractors’ provision of accommodation | £17 million | £75 million |

| Management and contracted services, the Advice, Issue Reporting and Eligibility contract (AIRE) and fees to AASC providers and cash card providers | £50 million | |

| Total spend (estimate for 2023) | £2,380 million | £2,937 million |

There have been some improvements in the commercial management of asylum accommodation and support contracts

1.42 Improvements found in the commercial management of the AASC contracts include: contract management; resourcing of the commercial team; data management and usage; and cost management. It should however be noted that many of these are very recent changes, the fruits of which are yet to be seen or verified.

1.43 Contract management: ICAI’s original review noted that there were no contract management or contract contingency plans in place for the AASC contracts, despite their high value. These are now in place and are of suitable quality. This is a considerable improvement that will help the contract management team navigate uncertainties and contextual changes, such as in asylum seeker arrivals.

1.44 Resourcing of the commercial team: ICAI’s original review found that the commercial team managing the AASC contracts was under-resourced and that the contract management skills and qualifications of the team were not equal to the value and complexity of the contracts. Furthermore, the operational teams managing the AASC contracts were too thin on the ground to move away from a purely reactive mode in response to crises. Since then, there has been substantial progress on contract management staffing. The commercial team has recruited two colleagues with extensive contract management skills and experience, and has as a result of stronger team capacity felt able to start thinking and planning more strategically, and negotiate more effectively with the contract holders. The challenge is to ensure that the commercial team retains adequate resources over time, since the new recruitments are on contracts rather than permanent staff. The commercial team is in the process of presenting a resource paper for approval to recruit much needed permanent members of staff. This recruitment will be crucial for continuing the improvements in contract management and moving away from what is still mainly a crisis handling mode. As one Home Office interviewee noted, “it is demanding to be in the middle of the news all the time”.

1.45 There is also, since ICAI’s review, a dedicated post holder supporting “Project Maximise”, which is focused on improving occupancy rates in the hotels contracted for asylum accommodation. The commercial team told us that this post has led to significant savings and freed up other staff to concentrate on other operational matters. However, this is not yet reflected in cost figures, since hotel costs for asylum accommodation were reported by the Home Office in October 2023 to be £8 million per night.

1.46 Data management and usage: The commercial team has adopted a more strategic approach to the gathering and use of data, and told ICAI that this has had direct impact on the value for money of the AASC contracts. The commercial team spent time in the first half of 2023 gathering appropriate data in order to establish the true costs of services. Once the cost analysis was done, cost models were put in place in preparation for negotiations with the contract holders. The more robust data source has enabled better-evidenced negotiations with contract holders and better-informed review of invoices. This has, ICAI was told, also led to clawback of costs.

Any cost savings from various initiatives and measures cannot yet be verified, and many of the unit costs quoted to ICAI for 2023 are higher than those provided for 2022

1.47 Cost reductions: The government update on progress stated that “Project Maximise has now hit its target, increasing the number of CA [contingency accommodation] bedspaces by 9,200. This has avoided the need for 72 average sized hotels. In financial terms, this work has already delivered £59m in cost avoidance since April 2023, and is currently delivering an equivalent of £237m in annual cost avoidance for the taxpayer”. The commercial team confirmed in an interview that the combination of improving hotel occupancy rates and closer management of the AASC contracts, including the cost analysis, had saved the Home Office around £300 million, and an additional written update to ICAI noted that Project Maximise had delivered 10,800 bedspaces in hotels by the end of December 2023.

1.48 ICAI was not able to verify these claims on cost savings. As the Home Office itself emphasises, the cost of hotel accommodation per person per night fluctuates widely as different hotels are stood up or closed down. Different teams also seem to operate with different numbers. For ICAI’s original review, we were given an average per person per night cost of £120 in March 2023, which was significantly lower than the figure we had first been given during evidence gathering in 2022. For this follow-up, we were told that the cost per person per night had reduced from £165 in 2022 to £139 in December 2023, but that costs fluctuated widely. In a February 2024 letter to the chair of the House of Commons’ Home Affairs Committee, the Home Secretary stated that “the latest running costs for the Bibby Stockholm [barge] are £120 per person per night, compared with the latest average hotel cost of £140 per person per night”.

1.49 The number of asylum seekers living in hotel contingency accommodation has remained steady. According to Home Office statistics, there were 45,775 asylum seekers living in hotels at the end of December 2022 and 45,768 in December 2023. Numbers fluctuated somewhat in the months in between. The statistics show that work on finding alternative, and more cost-effective, large sites for asylum accommodation has not yet led to noticeable shifts in accommodation patterns: in December 2023, there were 2,010 asylum seekers in other contingency accommodation than hotels, such as large sites, up from 1,945 in December 2022.

1.50 There has also been little shift in the use of dispersed accommodation (usually flats or houses): in December 2023, 56,489 asylum seekers were housed in dispersed accommodation, up from 56,143 in December 2023. The figures, in other words, remain stubbornly steady. A new dispersed accommodation property board has been up and running since October 2023, with the objective of matching available property from landlords and their agents with the Home Office’s needs, and an emphasis on larger-scale properties such as blocks of flats. Service providers bring proposed properties to the board. The prices for these are estimated at around £40-50 per person per night, a significant saving on hotel prices (although still considerably higher than the dispersed accommodation costs quoted by the Home Office to ICAI for our original review, which was £18 per person per night). Such accommodation would also have the added benefit of asylum seekers living among the community rather than isolated in hotels.

1.51 However, the board is new, and was described as “still finding our feet in terms of the process”. ICAI was told that there had been a few approvals, and that suppliers were using the board and sending submissions. The board first checks if the proposed accommodation is in an area where there is a need, and not over-subscribed. The submission is then sent to the commercial team for a value for money assessment. ICAI heard from other stakeholders that the process for finding new properties remains cumbersome.

The key performance indicators for the asylum accommodation and support contracts have not yet been updated, but there are plans to do so in 2024

1.52 KPIs: There has not yet been any progress on the aspect of ICAI’s recommendation related to reviewing and updating the AASC KPIs. There is still a perception within the Home Office that the AASC contracts do not require review or updates. However, the commercial team does recognise that it is good practice to review KPIs on at least an annual basis. Now that more appropriately qualified staff are in place, ICAI was told that there are plans for this crucial element to be addressed early in 2024, to ensure that all KPIs are fit for purpose and enable incentivisation.

Conclusion on Recommendation 3

1.53 While contract management improvements and cost saving measures have been made, impact on overall asylum accommodation costs is not yet discernible. The AASC KPIs have not yet been updated to address ICAI’s concerns. The amounts spent on hotel accommodation for asylum seekers has continued to grow, regardless of the Home Office closure of up to 100 hotels between October 2023 and March 2024. ICAI has not had access to more detailed financial information to enable us to assess why the daily cost of hotels has increased in that same period; indeed, the ODA data received from the Home Office for 2023 were less detailed than those provided for 2022, and did not break the spending figures down into contingency, initial and dispersed accommodation. The response as a whole is therefore judged to be inadequate.

Recommendation 4: The Home Office should consider resourcing activities by community-led organisations and charities as sub-contractors in the asylum accommodation and support contracts for dedicated activities to support newly arrived asylum seekers and refugees.

1.54 ICAI’s original review found that the inclusion of the Advice, Issue Reporting and Eligibility (AIRE) contract managed by a non-governmental organisation alongside the AASC private contractors had been an improvement from the previous COMPASS contracts for asylum accommodation, but noted that there was no other public funding for voluntary organisations to provide asylum seekers and refugees with information and support. The asylum accommodation and support system relies too heavily on organisations and individuals going ‘above and beyond’ to provide adequate services. ICAI saw the difference this could make when we inspected hotels hosting Afghan refugees who had arrived as part of the better-resourced Afghan Citizen Resettlement Scheme and Afghan Relocation and Assistance Policy: in one hotel a local women’s charity made a big difference to addressing the needs of women and girls.

1.55 The Home Office accepted this recommendation, and noted that community-led organisations and charities make a highly valued contribution in supporting asylum seekers. The department’s update on progress on this recommendation stated that: “The Home Office also provides grant funding to voluntary sector organisations, including an Asylum Seeker Therapeutic Support Grant to Barnardo’s. […] Accommodation providers routinely engage with local stakeholders to establish Multi-Agency Forums (meetings created to discuss issues arising in contingency accommodation in a particular setting) and link into existing Voluntary Community Sector (VCS) groups and faith sectors to offer additional nuanced support to service users, whilst considering local VCS infrastructure.”

1.56 However, beyond this update on existing activities, ICAI did not receive any further information suggesting plans by the Home Office to make financial resources more available for community-led organisations and charities to support newly arrived asylum seekers and refugees. Documentation and an interview regarding the pilot Refugee Transitions Outcomes Fund (RTOF) programme provided interesting insights into the Social Impact Bond model of funding. This is an outcomes-based commissioning model, where the Home Office pays for outcomes verified and delivered by providers. Upfront capital to fund services is paid by social investors, who get back their money through the delivery of outcomes. The RTOF pilot was focused on integration support for refugees recently recognised through the asylum system, and was therefore not in scope for ICAI, since integration is not an ODA-eligible activity.

1.57 ICAI’s own evidence gathering in 2022 as well as 2023 reporting from the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI) show that prolonged stays in contingency accommodation, often in isolated areas and in a state of enforced idleness, is detrimental to wellbeing and health, and can exacerbate mental health problems. This can make integration more difficult for the many who in due course receive refugee status in the UK. Having not seen new initiatives or plans in this area, ICAI finds the response to its recommendation to be inadequate.

Recommendation 5: The government should ensure that ODA-funded in-donor refugee support is more informed by humanitarian standards, and in particular that gender equality and safeguarding principles are integral to all support services for refugees and asylum seekers.

1.58 During evidence gathering for the original review, ICAI heard about many safeguarding concerns from a wide range of stakeholders. Refugees and asylum seekers in hotel accommodation – particularly women and girls – face significant risks, especially of gender-based violence and harassment. The review concluded that humanitarian standards were not incorporated into objectives for how activities funded as in-donor refugee support are delivered in the UK, even though it is classified as a form of humanitarian aid. Gender-sensitive approaches were not mainstreamed across support services for refugees and asylum seekers, despite the different needs and experiences of refugee and asylum-seeking men and women. The review found that practice around ensuring safeguarding and gender equality within the AASC contracts and the Afghanistan resettlement schemes was inadequate and that there was insufficient oversight from the Home Office of contractors’ approach to and training of staff in safeguarding.

1.59 The Home Office partially accepted this recommendation, but did not offer plans for improvement in its government response. In the November 2023 update on progress in response to ICAI’s follow-up review, a brief account of relevant activities was provided without accompanying documentation. Of the actions taken in response to the review, most important is the increase in human resources in the safeguarding hub, with around 16-17 new staff recruited. In interviews, we were told that the extra recruitment was partly to address safeguarding concerns around children in hotels. The safeguarding caseload was also changing as many of the ‘legacy backlog’ of asylum applications from before 28 June 2022 have been processed in the last year, with many vulnerable people in the safeguarding hub’s caseload finally receiving refugee status and moving out of the Home Office system. Meanwhile a new caseload is building up of asylum seekers who have arrived in the UK by irregular means whose claims are not being processed or progressed due to the Illegal Migration Act (IMA) and who are therefore currently in a state of limbo (see discussion of the IMA under Recommendation 2 above).

1.60 A training programme has been started for senior managers and policy leads on trauma-informed practice. An organisation of clinical psychologists conducted an initial assessment to understand how trauma-informed the Home Office’s asylum system is, in terms of how it shapes its messaging and interacts with service users. ICAI did not see the report or recommendations resulting from this assessment, but was told that the next stage is to design a training programme which will be delivered at three levels: trauma-aware, trauma-informed (enhanced training and awareness for those with more direct contact with asylum seekers) and trauma-enhanced (delivered to people who are regularly in contact with asylum seekers, as well as to senior managers). The trauma-aware training has just started, while the next two levels will be rolled out over the next two years. The aim is to embed a culture change, with all staff trauma-informed and trauma-aware.

1.61 This is a positive development, although we would have liked to see the rollout of the training happen more quickly. But more importantly, there is no change as yet in the oversight function the Home Office has over the safeguarding training and standards of contractors and hotel staff and management. ICAI was told again that service providers “are arm’s-length organisations, they are responsible for their own learning in this area”.

1.62 ICAI’s review had found that levels of training varied and were not sufficiently overseen by the Home Office, a conclusion also reached in an earlier report from ICIBI. In a subsequent (May-June 2023) inspection report from ICIBI, belatedly published by the Home Office on 29 February 2024, the Chief Inspector noted that “worryingly, the inspection found that basic clearances and training for some contractor staff had not been undertaken, resulting in a number of staff working with children and vulnerable adults for many months in hotels who had not undergone checks or training”. The report’s first recommendation was for the Home Office to “clarify the respective safeguarding responsibilities of all agencies, including contractors and subcontractors, involved in supporting asylum-seeking families with children in contingency accommodation and communicate this to stakeholders”.

1.63 Another ICIBI inspection report, focused on unaccompanied child asylum seekers, also belatedly published on 29 February 2024, noted improvements from its previous inspection but concluded on training that: “However, the Home Office acknowledges that this record [of training of all staff in hotels] is not up to date, and as the document does not include staff employed by the hotel or security staff, the department does not have a complete record of each person’s safeguarding training”.

1.64 The Home Office safeguarding team told ICAI that work is taking place to develop training courses and packages that service providers can replicate or feed into, but this is at an early stage. The safeguarding team is also working to embed standards and principles to ensure consistency in the quality of how asylum seekers are treated.

1.65 While there are some good initiatives and increased human resources in the safeguarding hub, the lack of proper oversight by the Home Office of safeguarding standards and training remains concerning. We therefore consider the response to this recommendation to be inadequate.

Recommendation 6: The Home Office should strengthen its learning and be more deliberate, urgent and transparent in how it addresses findings and recommendations from scrutiny reports.

1.66 During the evidence gathering for the original ICAI review, we did not see sufficient evidence that recommendations from scrutiny bodies were being systematically tracked and responded to. The review found that, in the project assurance dashboard for the AASC contracts that the Home Office shared with ICAI, many relevant recommendations from external independent scrutiny reports remained open, with no comments provided on action plans two or more years after scrutiny.

1.67 In returning to this recommendation this year, ICAI found that there is variability in the quality of the Home Office’s attention to recommendations, but that there are systems in place to track and report on progress. The Home Office assurance team has software that tracks recommendations from different audit sources and scrutiny bodies. The assurance team identifies responsible owners for each recommendation within the different departments and teams and the software provides notifications when actions are due. The assurance team also has dedicated staff who function as liaison officials with the larger scrutiny bodies such as the NAO and the Government Internal Audit Agency (GIAA).

1.68 In terms of scrutiny bodies that have produced recommendations in areas relevant to ICAI’s remit, the Home Office’s responsiveness to NAO recommendations seems to be relatively good. The ICIBI has seen less interaction with its recommendations, although ICIBI staff have noticed a recent improvement in the tracking and communications to update on responses to their recommendations. However, the biggest challenge for ICIBI has been to have the recommendations published in the first place. In 2023 there were long delays in the Home Office’s publishing of ICIBI’s reports. By February 2024, 12 reports and the annual report were waiting for publication, before all were released by the Home Office on the same day. As our discussion under Recommendation 5 shows, this includes delays in getting important recommendations on safeguarding responsibilities on to the Home Office’s tracking system, since these are not tracked until the reports are published.

1.69 During the course of this follow-up exercise, ICAI has established contact with the Home Office assurance team and we look forward to working together on seeing improvements in response to our ODA-related While there has apparently been some progress in relation to the NAO’s recommendations, we are concerned by the delays in publishing ICIBI’s inspection reports throughout 2023, and the uncertainty about when reports of inspections that are currently underway may be published now that there is no chief inspector in post. We also note the lack of supporting documentation shared with ICAI for this follow-up review. We therefore consider the response to this recommendation to be inadequate.

Conclusion

1.70 ICAI’s review of UK aid to refugees in the UK highlighted major value for money risks as a result of the way in which the aid spending commitment was managed. It took place at a time of soaring in-donor refugee costs which took a great toll on the UK’s development and humanitarian work around the world. Returning to our recommendations this year, we find that in-donor refugee costs, far from reducing, have actually increased. Value for money risks have not been reduced, given that the same number of asylum seekers are accommodated in hotels as of 31 December 2023 (45,768 people) as there were on 31 December 2022 (45,775), at extremely high costs to the UK taxpayer, much of which is covered by the ODA budget. The per person costs have not reduced, while standards of support do not seem to have tangibly improved.

1.71 While systems and processes for coping with the stresses this places on FCDO’s aid programme have mitigated the negative impacts, the fact that GNI has turned out to be higher than forecast is probably an even more significant factor. Most importantly in principle, the introduction of some flexibility into the UK’s aid spending commitment has allowed FCDO the space to push and pull multilateral contributions across financial years to protect its spending commitments.

1.72 In-donor refugee costs, which are categorised as ODA due to their humanitarian nature, continue to represent very poor value for money as humanitarian spend. While there have been positive developments, these are in the form of mitigations to a way of managing ODA spend where the department which overspends does not have to manage this within its own budget. In effect, FCDO takes the financial hit for other departments’ overspending – although it should be noted that this same system would also see an increase in FCDO’s budget if other departments were to underspend.

1.73 ICAI does not assess the adequacy of response to recommendations that were rejected, but we remain disappointed that the UK government has not taken up the opportunity to assess its methodology for reporting in-donor refugee costs or how these costs are counted towards the UK’s aid spending target. This is a topic that ICAI will undoubtedly return to in its future review programme.

1.74 ICAI considers the overall response to its recommendations to be inadequate. We expect to come back to Recommendations 3, 4 and 5 as outstanding issues next year. These were all areas where we saw some early actions that have potential if sustained and built up further to address some of the problems underpinning ICAI’s recommendations. However we have not seen evidence that the Home Office has found a route out of short-term crisis management towards longer-term solutions for asylum accommodation.

1.75 The Illegal Migration Act (IMA) is an important unknown piece in this puzzle: how the Act is implemented will have significant implications for the ODA eligibility of accommodation and support services for those arriving in the UK by irregular routes with the aim of seeking asylum. ICAI will therefore continue to follow developments on the IMA closely. The status of asylum seekers who have arrived after 20 July 2023 by irregular routes (and therefore would fall under the IMA) is not entirely clear – nor indeed is that of the cohort which arrived between 8 March and 20 July, the period during which the Illegal Migration Bill made its way through Parliament. The Home Office has allowed this cohort of arrivals to enter the asylum claims system but is not progressing their applications. This limbo state is untenable both from a humanitarian perspective and from a financial one. The new backlog of cases in limbo is building up fast, at considerable human and financial cost.