ICAI-Report-International-Climate-Fund

Traffic light system

| The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review. |

|---|

| Green: The programme performs well overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Some improvements are needed. |

| Green-Amber: The programme performs relatively well overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Improvements should be made. |

| Amber-Red: The programme performs relatively poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Significant improvements should be made. |

| Red: The programme performs poorly overall against ICAI’s criteria for effectiveness and value for money. Immediate and major changes need to be made. |

1 Executive Summary

This review assesses the International Climate Fund (ICF). This is a five-year (2011-2016), £3.87 billion fund managed jointly by DFID, DECC and Defra. It is a central part of the UK’s climate change response. Its goal is to support international poverty reduction by helping developing countries to adapt to the impacts of climate change, take up low-carbon growth and tackle deforestation. We reviewed the ICF at three levels: international, national (Indonesia and Ethiopia) and intervention level (15 programmes). We assessed emerging impacts and whether the ICF is likely to succeed in catalysing global action on climate change.

Overall

Assessment: Green-Amber

The UK has made a major policy commitment to supporting international action on climate change. It has catalysed positive action, taking a leadership position on the need to shape and deliver an effective international agreement. The ICF is both a significant contribution to climate finance and a tool for influencing action at the international and national levels. After a challenging start, it has built up significant momentum and is now well placed to deliver on its ambitious objectives. While many of its investments have had long lead times and remain unproven, there is evidence of early impact in a range of areas. It has pioneered new approaches in the measurement of results.

Objectives

Assessment: Green-Amber

The ICF has set itself the ambitious goal of transforming the global response to climate change. While its objectives are closely linked to the UK’s international policy commitments, they would benefit from greater clarity and precision. The ICF took some time to develop a coherent overall theory of change and allocation strategy but it is now clearer in its direction.

Delivery

Assessment: Amber-Red

Delivery has become more strategic with repeated course corrections. The ICF initially relied heavily on the multilateral development banks as spending channels but is now beginning to diversify its partnerships. When operating in middle-income countries, it relies primarily on loans and equity investments, rather than grants, which limits its delivery options and the activities it can support. It is trying to engage with the private sector but needs a more granular and nimble approach.

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

While it is too early to assess overall impact, the ICF has already had significant influence on the international climate finance system. There is also evidence of promising results from many of its activities at country level. The ICF is not, however, doing enough to ensure coherence and build synergies across its portfolio, particularly between multilateral and bilateral initiatives. Deeper engagement with recipient countries to build national capacity, policy and regulation would also enable stronger results.

Learning

Assessment: Green-Amber

The ICF is supporting the development of and has contributed to building global knowledge on climate change. It has helped the multilateral climate funds to become more effective. It has pioneered new approaches to measuring results. It is helping to bring climate into the mainstream of development, including in the UK’s bilateral aid programme. Improvements to results reporting and verification are, however, needed. The ICF also needs to become more transparent in its strategies, priorities and results with better reporting.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: The ICF should work through a wider range of delivery partners at the international and national levels, with a stronger understanding of their comparative advantages.

Recommendation 2: More flexibility in the allocation of resource and capital expenditure is needed. DECC and Defra would benefit from access to more flexible and direct resource and capital expenditure.

Recommendation 3: The ICF should develop a more differentiated strategy for working with the private sector, focussed on the particular conditions and approaches required to attract different forms of private capital.

Recommendation 4: The ICF should deepen its engagement with developing country governments and national stakeholders, including through greater emphasis on capacity development. This is likely to require greater access to grant and technical assistance resources, including for middle-income countries.

Recommendation 5: The ICF should strengthen coherence across multilateral and bilateral delivery channels and programmes and implement a common, country-level planning process and tracking system.

Recommendation 6: The ICF should be more transparent and inclusive, publishing its strategies, activities and progress on an ICF website, in a coordinated reporting format in partnership with other climate finance data providers.

1 Introduction

Background

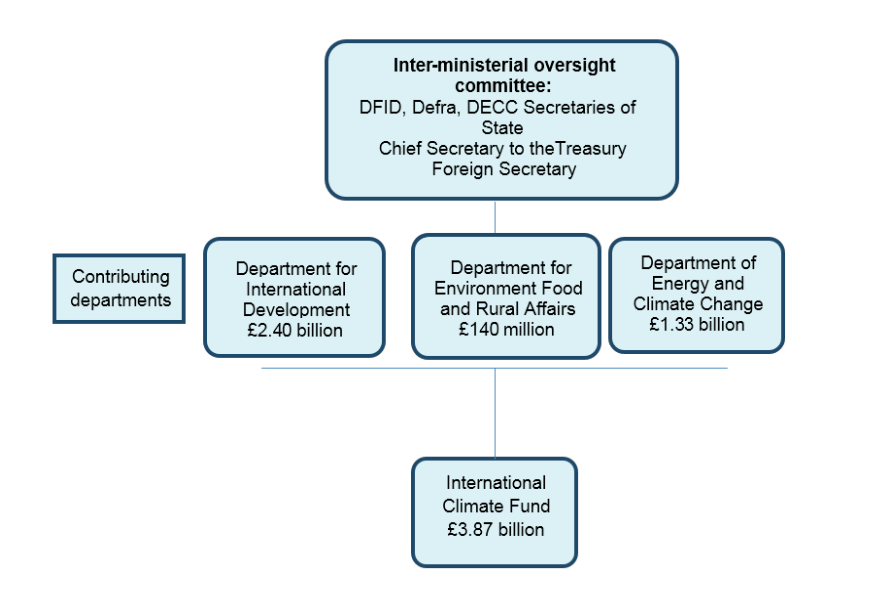

1.1 The International Climate Fund (ICF) is a £3.87 billion fund running from 2011 to 2016, jointly managed by the Department for International Development (DFID), the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Its goal is to support international poverty reduction by helping developing countries to adapt to the impacts of climate change, take up low-carbon growth and tackle deforestation. The governance summary and financial contributions per department are provided in Figure 4 on page 5.

1.2 The ICF is the UK’s primary instrument for funding international action on climate change. It is also an instrument for influencing others, to support global action on climate change.

The objectives of tackling climate change and global poverty reduction are closely linked

1.3 As a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),1 alongside 191 other countries, the UK has committed itself to taking action to stabilise greenhouse gases (GHGs)2 at a level that will keep average global temperatures from rising by more than two degrees. The UK Government has made a strong commitment to leading international action to mitigate the effects of climate change and to help affected communities to adapt.

1.4 Since the 1950s, unprecedented changes have been observed in the global climate system. The atmosphere and oceans have warmed, the volume of snow and ice has diminished, sea levels have risen and concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased. Each of the last three decades has been warmer than any preceding decade since 1850.3

1.5 Poor people and poor countries are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, through threats such as water shortages and increased incidence of extreme weather.4 Changing rainfall patterns are disrupting agricultural production, threatening the livelihoods of the rural poor and reducing food security. Through these and other processes, climate change has the potential to undermine progress in tackling global poverty.5

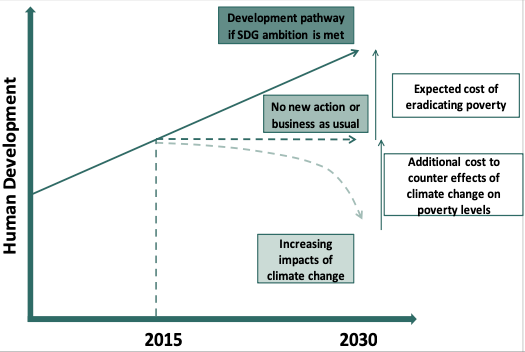

1.6 The two policy objectives of tackling climate change and reducing global poverty are, therefore, closely intertwined. Unchecked climate change is likely to have a dramatic, negative impact on poverty reduction efforts. At the same time, if developing countries meet their growing energy needs through conventional technologies, it will result in significant increases in GHG levels. Figure 1 is a graphical representation of how the two challenges relate to each other.

Chart showing: Development pathway if SDG ambition is met, Expected cost of eradicating poverty, Additional cost to counter effects of climate change on poverty levels, No new action or business as usual, Increasing impacts of climate change, Human Development from 2015 to 2030

The ICF’s contribution to global climate finance

1.7 The ICF was given an initial funding allocation of £2.9 billion, for the period 2011-12 to 2014-15.7 In the most recent Spending Review, this was increased to £3.87 billion and extended by a year, to 2015-16. While this contribution is significant within the UK aid budget, it represents only a small fraction of the US$ 100 billion (£60 billion) in climate finance that the international community has agreed to mobilise annually, from public and private sources, by 2020.8

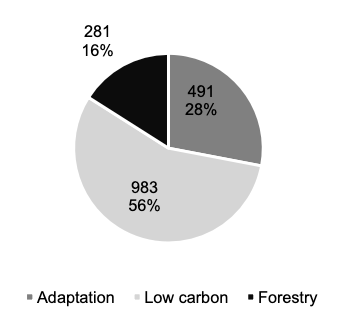

1.8 By the end of the 2013-14 financial year, the ICF had spent £1.75 billion: 45% of its funding. Many of its individual activities, however, have long lead times and remain in their infancy. So far, more than half of its funding has gone towards climate change mitigation – that is, promoting low-carbon development. 28% has gone towards adaptation – that is, helping poor communities cope with the impact of climate change (see Figure 2).

Pie chart showing: Adaptation (491, 28%), Low carbon (983, 56%), Forestry (281, 16%)

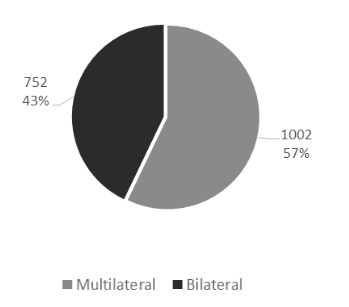

1.9 The ICF directs around three-quarters of its funding through multilateral channels (see Figure 3). Much of this goes to a series of World Bank-administered multi-donor trust funds, called Climate Investment Funds (CIFs), which the UK helped to establish. The CIFs consist of four separate funds, promoting clean technology, renewable energies, reduction in deforestation and the integration of climate resilience into national development planning. With total funding commitments of US$8 billion from 14 donor countries, they operate in 48 developing and middle-income countries, providing a mixture of grants, loans and equity investments. They aim to leverage an additional US$55 billion from other sources.9 The international architecture for climate finance continues to evolve and new multilateral channels, such as a new Green Climate Fund, are under development.10

Pie chart showing 57% Multilateral and 43% Bilateral

1.10 The ICF’s bilateral programming works with recipient countries to strengthen their capacity to promote low-carbon development, reduce deforestation and respond to climate change. It also funds a range of individual interventions at the national level.

1.11 The ICF is also a tool for influencing others. It works to strengthen the international climate finance architecture and to attract more global finance. It seeks to influence particular sectors of the global economy, such as the market for clean energy technologies. It helps to promote international knowledge and expertise on climate change, by promoting innovation, generating evidence and promoting mechanisms for sharing knowledge. It also aims to ensure that the UK’s own development assistance is ‘climate smart’.

1.12 With its multiple objectives and delivery channels, the ICF operates at a larger scale and over longer time frames than any individual aid programme. For example, developing large-scale wind and solar power capacity can take a decade or more. Helping developing countries to move to a low-carbon development pathway is an objective with no fixed end date, requiring considerable flexibility.

1.13 This review assesses the operations of the ICF across its three levels:

- the international level, including its policy advocacy and its influence on international systems and processes;

- the national level, through its work to build the capacity of priority countries; and

- the programme level, through its funding of specific activities and interventions.

1.14 We assess whether the ICF has coherent strategies and objectives, whether its funding strategies and choice of delivery partners are appropriate and whether it is on track to deliver its intended impacts at international and national levels. We consider both the direct effects of its funding and its ability to catalyse and influence action by others.

1.15 Our methodology included various components, including:

- a literature review;

- interviews with decision makers and stakeholders in the UK and internationally;

- a portfolio review of the 15 largest programmes, including reviews of business cases, evaluations and other documentation and interviews with people involved in their delivery. The sample, which included nine multilateral and six bilateral programmes, spans all of the ICF’s thematic objectives and accounts for more than half of its expenditure to April 2014. The sample is summarised in Figure 5 on page 6; and

- visits to Indonesia and Ethiopia, where we looked at the full range of multilateral and bilateral programming, to assess coherence and likely impact.

| Country / Region | Thematic Area | Programme Title | Contribution from UK ICF (£ millions) | Share in Total ICF Spending to date | DECC | Defra | DFID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 largest multilateral programmes | |||||||

| Global | Low carbon | Clean Technology Fund (CTF) - Climate Investment Funds (CIF) | 425 | 24% | 90% | 0% | 10% |

| Global | Adaptation | Pilot Program for Climate Resilience (PPCR) - CIF | 100 | 6% | 15% | 0% | 85% |

| Global | Adaptation | Support to the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDC FUND) | 80 | 5% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Global | Forestry | BioCarbon Fund Initiative for Sustainable Forest Landscapes | 75 | 4% | 67% | 33% | 0% |

| Global | Low carbon | Global Environment Facility (focus on climate change) | 63 | 4% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Global | Low carbon | Scaling-up Renewable Energy Program - (CIF) | 50 | 3% | 50% | 0% | 50% |

| Global | Forestry | Forestry Investment Program (FIP) - CIF | 25 | 1% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| Global | Adaptation | Support to the Adaptation Fund for developing countries to build climate resilience | 10 | 1% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Global | Low carbon | Partnership for Market Readiness Fund | 7 | 0.4% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| 6 largest bilateral programmes | |||||||

| Global | Adaptation | Adaptation for Smallholder Agricultural Programme (ASAP) | 115 | 7% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Global, China, South Africa, Indonesia | Low carbon | Global Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) Capacity Building | 60 | 3% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| Global | Low carbon | Climate Public Private Partnership | 50 | 3% | 76% | 0% | 24% |

| Global | Low carbon | Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA) Facility | 50 | 3% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| Global | Cross-cutting | Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) - Outputs and Advocacy Fund | 46 | 3% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Bangladesh | Adaptation | Bangladesh Climate Change Programme I - Jolobayoo-O-Jibon | 42 | 2% | 0% | 0% | 100% |

| Total 9 multilateral + 6 bilateral programmes | 1,198 | 68%11 | 54% | 2% | 44% | ||

| Other bilateral programmes (not reviewed) | 556 | ||||||

| Total ICF spending for all programmes | 1,754 | ||||||

2 Findings: Objectives

Objectives

Assessment: Green-Amber

2.1 This section considers the ICF’s objectives at the international, national and intervention levels. We review its strategy and evolving theory of change.

The objectives of the ICF reflect the UK’s far-reaching international commitments

2.2 Successive UK governments have made strong commitments to promoting international action on climate change. To support these commitments, the ICF’s goals are necessarily very ambitious.

2.3 The Fund’s thematic priorities mirror internationally agreed priorities for climate finance, namely:

- to help poor people adapt to the effects of climate change (adaptation);

- to reduce carbon emissions by promoting low-carbon development and enabling poor countries to benefit from clean energy (mitigation); and

- to reduce deforestation.

2.4 The ICF also supports a number of UK policy interests, including demonstrating the feasibility of low-carbon and climate-resilient growth, supporting UK positions in the UNFCCC negotiations and driving innovation, including through new partnerships with the private sector.12

2.5 The ICF has outlined a series of far-reaching goals, including:

- helping developing countries to adopt low-carbon development pathways;

- ensuring that poor and vulnerable people in developing countries are supported to respond effectively to existing climate variability and future impacts of climate change;

- supporting global efforts towards a 50% reduction in global deforestation by 2020; and

- mobilising of US$100 billion per annum for low-carbon, climate-resilient development.13

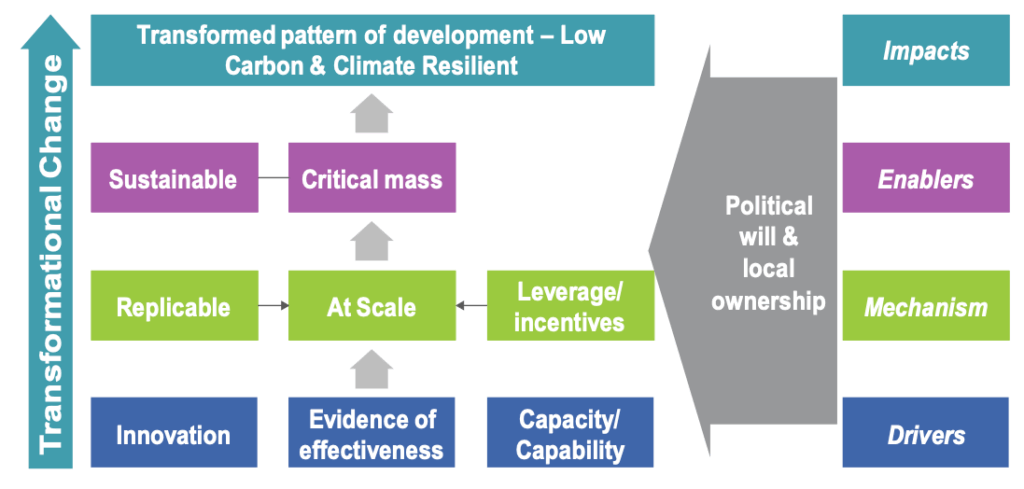

2.6 The strategy acknowledges that, to achieve these goals, the ICF will need to wield an influence that far exceeds the direct impact of its own spending.14 Its ‘theory of transformational change’ (see Figure 6 on page 8) identifies four mechanisms for transformational change: delivery at scale; replication by others; promoting innovation; and leveraging additional financial flows. It also stresses the need for political will and local ownership. By catalysing action at both international and national levels, the ICF hopes to achieve a critical mass of activity, leading to a decisive shift towards low-carbon and climate-resilient development (see Figure 7 on page 8).

2.7 The ICF’s 2011 strategy links these objectives to global poverty reduction. It notes that adaptation helps poor people to protect their livelihoods through better management of climate change risk and increases their ability to cope with climate-related events like droughts and floods. Climate change mitigation can help developing countries to reduce poverty by making low-carbon technologies and approaches more widely accessible, while reducing the rate of deforestation can help sustain the livelihoods of the 1.2 billion people around the world who depend on forestry, reduce emissions and protect biodiversity.15

Scale: National, sectoral or economy-wide programmes, including institutional and policy reform, for example energy sector reform; large-scale deployment of a technology so that it reaches critical deployment mass or provision of technical assistance to support a country to reduce national fossil fuel subsidies;

Replicable: Programmes which others can copy, leading to larger scale or faster roll out, for example key policy change or helping to drive technology down the learning curve;

Innovative: Piloting new ways of achieving objectives that could lead to wider and sustained change. These programmes are often high risk but with high potential returns; and

Leverage: Programmes that leverage others to increase the impact also increase the likelihood of their being transformational, by unlocking scale and replication potential. Examples of leverage include domestic flows from recipient country and private sector or other aid flows. Leveraging should be considered to be an addition to existing funding sources, provided they are not crowded out.17

2.8 To achieve these goals, the ICF has defined five main areas of activity:

- building knowledge and evidence;

- developing, piloting and scaling up innovative activities;

- supporting country-level action;

- creating an enabling environment for private sector investment; and

- mainstreaming climate change into UK, EU and other development assistance.

2.9 We find these objectives to be largely appropriate, reflecting a holistic approach to the challenges of climate change. This is, however, a rapidly evolving field. The ICF’s objectives and approaches will need to be regularly updated. We take the view that there is now scope for the ICF to adopt a more focussed approach, to maximise its potential for impact. A narrower set of objectives and a clearer definition of the role that multilateral and bilateral delivery channels play in realising them would be helpful. There is also room for the ICF to do more to support innovation on low-carbon and climate-resilient approaches to development and to pilot new approaches to engaging the private sector.

The ICF’s overarching theory of change took time to emerge

2.10 Each of the three ICF themes (adaptation, low-carbon growth and forestry) has its own theory of change. These theories of change were approved by the ICF Board in July 2011, together with an overall Implementation Plan.

2.11 It took until April 2014, however, to develop a fully articulated, overarching theory of change showing the connections between outcomes, outputs and activities. The responsible departments have acknowledged that establishing an integrated theory of change earlier in the process would have helped to guide the development of a strategic portfolio. As it was, pressure to meet spending targets meant that early spending decisions were taken without a coherent, overarching strategy in place.

Country allocation of ICF finance has been appropriate

2.12 Within the internationally agreed list of ODA-eligible countries, DFID has established a list of 28 priority countries for UK development assistance. The ICF initially established a list of 32 priority countries. The two are compared in Annex A4.

2.13 There is a high level of overlap between the two. The ICF list, however, also includes a number of middle-income countries that offer major opportunities to mitigate climate change, including Brazil, China and Indonesia. In these countries, UK support is helping to integrate climate change mitigation into national development processes.

2.14 We regard the inclusion of these middle-income countries in the ICF portfolio as appropriate. Continuing emissions growth in these countries will adversely affect all countries, with low-income countries particularly vulnerable. It does, however, pose some operational challenges. The ICF will need to continue to strengthen its collaboration with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), including in places where there is no DFID country office.

Influencing national priorities

2.15 To achieve its goal of transformational impact, the ICF needs to influence the policies and investment priorities of its priority countries. It is, therefore, working to support national climate policy and target setting. For example, it is helping Ethiopia to develop a Climate- Resilient Green Economy Strategy. In Indonesia, it is supporting efforts to implement national climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies.18 It is working with the Government of Ethiopia to set up a national fund, supported by strong systems, to help deliver the Climate- Resilient Green Economy and attract further international climate finance. It is also working with the Partnership for Market Readiness, a World Bank-administered grant-making fund, to support developing countries to develop and pilot carbon pricing policies. We have some concerns, however, as to whether ICF programmes have secured sufficient support from national stakeholders. In Indonesia, for example, while government departments were broadly supportive of UK efforts, they expressed confusion about the diverse objectives of UK-supported programmes through bilateral and multilateral channels.

2.16 At the activity level, we found the processes by which national governments, the private sector and civil society stakeholders contribute to the design of ICF programmes to be inadequate. While improvements have been made to design processes, the ICF acknowledges that it needs to deepen its engagement with national governments and other stakeholders. We are also concerned about the ICF’s approach to mobilising private sector investment and whether its focus on leveraging private investment creates the right set of incentives for investors.

3 Findings: Delivery

Delivery

Assessment: Amber-Red

3.1 In this section, we consider whether the management structure of the ICF facilitates the effective delivery of its programme. We assess how capitalisation of the ICF affects its operations. We examine the ICF’s selection of delivery partners and its overall approach to portfolio management.

The structure of the ICF enables working across sectors

3.2 As a tri-departmental instrument managed jointly by DFID, DECC and Defra, the ICF brings together the development expertise of DFID with the sector experience of DECC and Defra. It also includes the FCO and HM Treasury within its governance. This represents a ‘whole-of-government’ approach to addressing climate change, harnessing diverse expertise and capacity across UK government departments. The ICF’s structure, therefore, mirrors the recommendation19 often made to developing countries that they should bring together key agencies in support of their efforts to pursue low-carbon and climate-resilient development.

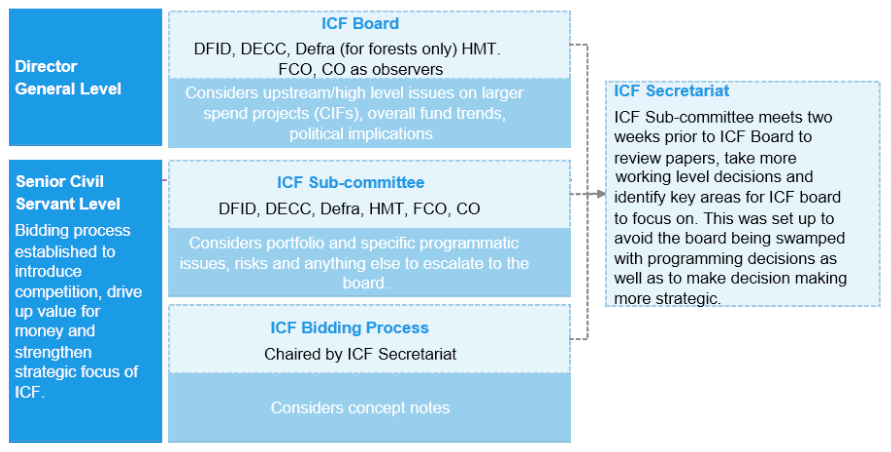

3.3 Ministerial oversight of the ICF is provided by the Secretaries of State of DFID, DECC and Defra, together with the Chief Secretary to the Treasury and the Foreign Secretary in a consultative role. These departments, occasionally joined by the Cabinet Office, attend ICF Board meetings, which are chaired by DFID.20 Figure 4 on page 5 illustrates the ICF’s governance structure, together with the financial contributions made by the main departments.

3.4 The FCO has been characterised as a ‘fourth partner’21 in the ICF by DFID. This relates to the role of the FCO’s Prosperity Fund22 and its overseas network in delivering programmes, particularly in countries with no DFID bilateral aid programme.

3.5 The ICF Secretariat is led by DFID and supported by DECC and Defra staff. Their current role is to manage routine processes and provide support to the Board. There is a need to improve oversight and management of ICF information and data by the Secretariat, who remain dependent on programme leads.

Pressure to spend ICF funds quickly has not always been conducive to effective delivery

3.6 The ICF’s funding is significant, within the expanding UK aid budget. This translated into substantial pressure to spend rapidly, which has sometimes come at the cost of strategy development and considered programming choices.

3.7 The UK government’s four-year spending review set an ICF target of £425 million in its first year of operations (see Figure 8 on page 12). This put considerable pressure on DFID and DECC to establish the ICF’s structures and processes and to begin spending. Concerns about the implications of this pressure were raised by the departments at the time. In our view, pressure to spend rapidly has contributed to some of the delivery challenges observed in this review.

The ICF’s programming and delivery options are constrained by its reliance on capital expenditure

3.8 The ICF is funded from a combination of capital (investment) and resource (recurrent expenditure) budgets, according to a proportion agreed by departments with HM Treasury in each Spending Review.23 DFID’s contribution is divided approximately equally between capital and resource, while DECC and Defra provide only capital (see Figure 8 on page 12).

| Dept. Resource/Capital split | Base line 2010-11 £m | 2011-2012 £m | 2012-2013 £m | 2013-2014 £m | 2014-2015 £m | 2015-2016 £m |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFID Resource & (up to 50%) Capital | 400 | 275 | 410 | 445 | 670 | 600 |

| DECC Capital | 250 | 140 | 240 | 400 | 220 | 329 |

| Defra Capital | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 40 |

| Total | 650 | 425 | 670 | 875 | 930 | 969 |

3.9 This in turn influences how the ICF spends its funds. The DECC and Defra capital funds must be spent in accordance with HM Treasury guidance. This requires that a capital asset is created on the balance sheet.24 This budget is, therefore, not available for items requiring recurrent expenditure, such as grants for technical assistance or research, unless DFID agrees to exchange resource for capital with DECC or Defra from within ICF departmental allocations (since DFID is the only holder of ICF resource budget of the three departments). In some cases reaching agreement has taken three to five months. This can delay delivery. For 2015-16, HM Treasury has agreed a 5% ‘pre-authorised switch’ between the DFID resource budget and DECC and Defra capital funds. This should provide greater flexibility in investment choices.

3.10 Capital expenditure is used to support private-sector investment in low-carbon and climate-compatible development. This can be effective where viable investments are available and where there is sufficient capacity within the private sector to take advantage of the opportunities. For example, the IFC invests at close to commercial rates, to avoid market distortions.25

3.11 Capital expenditure is not, however, well suited to building institutional capacity or helping to put in place the policies, regulations and governance arrangements required for low-carbon and climate-resilient development. Capital is also not well suited to meeting upfront project development needs, such as feasibility studies. In many instances, grant funding must be used in a strategic way to unlock large-scale investment flows, by reducing risk or the cost of finance.

3.12 Furthermore, capital expenditure is only suitable where the recipient institutions have the capacity to make and manage investments that can earn a return soundly. This has been an important influence on the ICF’s choice of delivery partners.

3.13 In our view, a more flexible approach to the balance between capital and resource funding is required, in order to make the most effective use of ICF funds. In Indonesia, for example, we found that better results could have been obtained by combining capital and resource expenditure in strategic ways, with the former provided through multilateral channels.

The ICF’s partnerships with multilateral development banks have been fruitful

3.14 The ICF is substantially dependent on the multilateral development banks (MDBs) to deliver its assistance – in large part because they have the capacity to manage returnable capital. Figure 9 on page 13 shows the intermediaries through which the ICF works.

3.15 Over 64% of ICF funding has gone through a small group of trusted MDBs, in particular the World Bank. The World Bank plays a prominent role in 9 of the 15 largest ICF programmes, either as fund manager or implementer.

| Intermediaries | £ millions | % |

|---|---|---|

| Climate-dedicated fund, usually including MDBs as implementing agencies | 769 | 44% |

| Multilateral development banks | 358 | 20% |

| Multilateral agencies | 216 | 12% |

| Other* (e.g. private firms) | 235 | 14% |

| Bilateral development agencies | 126.5 | 7% |

| Civil society organisations | 29.5 | 2% |

| Research institutions | 18 | 1% |

| Miscellaneous (small programmes) | 2 | 0% |

| Total | 1,754 | 100% |

* Includes programmes with multiple intermediaries.

3.16 We take the view that this was an appropriate choice by the ICF, particularly during its early years of operation. It allowed the ICF to harness the MDBs’ substantial knowledge and experience in the area and their capacity to manage large investments. It also enabled the ICF to influence the MDBs’ programming choices and to push for the mainstreaming of climate change across their investment portfolios. ICAI will be undertaking a review of DFID’s funding through multilaterals in 2014-15.26

3.17 The ICF Mid-Term Evaluation found that multilateral investments ‘bring the benefit of being able to programme large amounts with delegated management and administration.’27 The 2013 Multilateral Aid Review (MAR) update and the Multilateral Organisations Performance Assessment Network (MOPAN) also reported favourably on the multilateral channels used by the ICF.28 We have not conducted an independent assessment of the MAR and MOPAN ratings.

3.18 While working through the MDBs was a logical choice, we found variations in their performance. Several of their programmes have been substantially delayed as they went through a process of learning how best to target low-carbon and resilience enhancing investment opportunities. As Annex A1 shows, there has now been some course correction in many of the ICF’s delivery channels, including major programmes funded through the CIFs.

The ICF has had a positive influence on multilateral institutions and climate funds

3.19 The ICF has made substantial investments in multilateral climate funds as delivery instruments, particularly the CIFs. As we discuss below under Impact, the CIFs have piloted new approaches to climate finance and had significant influence on international policy processes. The ICF has helped to drive reforms and to promote more inclusive decision-making processes.29 The UK has a seat on all CIF Trust Fund Committees as one of usually eight donor members.30 Examples of ICF influence include:

- Results: strengthening results frameworks;

- Private sector: targeted development programmes;

- Gender: comprehensive review of approach and recruitment of a specialist; and

- Increasing transparency and inclusiveness: project documents are now published, governing committee sessions are now open to the public.

3.20 A recent evaluation of the CIFs31 highlighted the importance of continuing to deepen engagement with government, private sector and civil society organisation stakeholders. This is necessary in order to ensure that programming aligns with national priorities and that recipients have a strong commitment to effective implementation.32 In the case of the Global Environmental Facility (see Figure 14 on page 20), the UK has also supported national portfolio formulation exercises that enable more engagement of national stakeholders and better alignment with country priorities.

There is scope for using a wider range of delivery partners

3.21 There is now scope for the ICF to use a wider range of delivery partners, including civil society and the private sector. In 2013, DECC commissioned an external review of how the range of delivery options could be increased.33 The review identified three potential vehicles: the UK Green Investment Bank, the Private Infrastructure Development Group and CDC Capital Partners PLC (CDC).34 Work is now in progress with regard to the UK Green Investment Bank. UK engagement with the Green Climate Fund, the new multilateral channel through which a growing share of international climate finance is expected to flow, should also help with this.

3.22 Initially, the ICF did not make much use of CSOs as delivery partners. One exception was its establishment of the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN), through a consortium of three companies and three CSOs.35 More recently, CSOs have become more involved in the delivery of ICF programmes. For example, the Building Resilience and Adapting to Climate Extremes and Disasters (BRACED) programme has made 21 project development grants to CSO-led consortia in 15 countries.36

3.23 We found, nonetheless, that the ICF could make greater use of the influence and outreach of major international CSOs. DFID already works with many of these organisations in other fields.

The ICF’s approach to the private sector is evolving

3.24 The ICF’s private sector engagement strategy recognises that private firms play a growing role in the sectors that are most closely linked to climate change in developing countries, particularly energy and transport.37 Available data suggest that the private sector accounts for 57% of climate change-related investment in developing countries, compared with 88% in developed countries.38

3.25 One of the ICF’s objectives is ‘to build an enabling environment for private sector investment and to engage the private sector to leverage finance and deliver action on the ground’. It has various ways of engaging with the private sector. For example, it has devoted significant effort to developing the Capital Markets Climate Initiative – an international platform for promoting the sharing of knowledge and experience amongst governments, firms, NGOs and research institutes.39 We also saw examples of engagement with entrepreneurs and SMEs at the micro-level (see Figure 10 on page 15).

3.26 In June 2014, the UK, the USA and Germany, in collaboration with other major donors, launched the ‘Global Innovation Lab’. This is a new global public-private platform to work with development finance institutions, including export credit agencies, private banks and others, to encourage private investment in low-carbon, climate-resilient infrastructure in developing countries. This is a welcome attempt to find new ways to engage mainstream investors around climate-related opportunities.

3.27 Despite these initiatives, we are not convinced that existing programmes in the ICF portfolio have engaged the private sector sufficiently. This echoes the mismatch in the scale of ambition and ability to deliver as identified by the ICAI Private Sector Development review.40 There is still a significant shortfall of finance available for early-stage entrepreneurial investment.41 There is also continued need for financing for high-risk investments in technological development, to improve the viability of low-carbon technologies.42

The first tender resulted in 186 bids, of which 26 were shortlisted and eight received funding, with awards ranging from US$25,000 to US$37,500. Examples of projects include the conversion of indigenous miscanthus grass into biomass pellets for use in energy production and the distribution by women of silver-coated ceramic water filters, to reduce bacterial disease.

One recipient of CIC support, which we visited, is a small hotel that is piloting rainwater harvesting, the recycling of wastewater, biomass heating for kitchens and the use of recycled materials for construction and solar panels.43

3.28 This shortfall is recognised by the departments involved, who have been testing a range of new approaches, including potential spending through the UK’s own Green Investment Bank on international programmes. We see potential synergies between the work of the ICF and DFID’s new Economic Development Strategy process. We encourage DFID to promote exchange of experience between the two.

3.29 Private sector people who were interviewed for this review stressed the need for the ICF to work through a more nimble set of financial channels, so that it can respond within the tight timelines on which private investors need access to capital.44 They also highlighted the growing diversity of agents that are now interested in low-carbon development opportunities, including private funds and banks in developing countries, who could be useful partners in future ventures.

Portfolio management has strengthened

3.30 Despite the pressure on the ICF to spend quickly, we found a range of appropriate measures in place to safeguard the quality of investments. Many of DFID’s investments were scrutinised under the climate pillar of the 2010 Bilateral Aid Review. Multilateral bids were scrutinised through the Multilateral Aid Review process.

3.31 The ICF Board comprises members at Director-General level from DFID, DECC, Defra and HM Treasury. Figure 11 on page 16 outlines the revised management structure. Initially, the Board scrutinised all proposals for funding; this function was later delegated to a sub-committee. Projects were rejected at this stage if they did not meet the ICF’s objectives. In the first nine board meetings, 31 concept notes were accepted, 13 were sent back for further development and two were rejected.45

3.32 Since November 2011, the ICF sub-committee meets two weeks prior to each ICF Board meeting to review papers, take working-level decisions and identify the issues on which the Board should focus. In our view, this was an important and welcome change, enabling the Board to strengthen its strategic oversight role.

3.33 This process was further improved with the introduction of competitive bidding rounds in Spring 2012. This has helped to drive value for money. Technical panels from the three departments, including members drawn from outside the ICF, gave each concept note a ‘RAG rating’ for potential for transformative impact, strategic fit and value for money (VFM). In the first bidding round, this resulted in £300 million in proposals given a ‘green’ rating for endorsement, £240 million scoring ‘amber’ and £186 million scoring ‘red’, which led to them being rejected.

The shifting focus of ICF delivery causes delays

3.34 After two bidding rounds, additional guidance on the ICF’s priorities was provided through the 2013 ICF Strategy Refresh. Ministers agreed that ICF interventions should be strategic in nature and focus on the delivery of larger outcomes. The Strategy Refresh also concluded that bilateral spending on climate change adaptation should focus on low-income countries. Bilateral programmes in middle-income countries would be supported with returnable capital or technical assistance. Multilateral spending on both adaptation and mitigation could continue in all ODA-eligible countries.

3.35 During the recent Resource Allocation Round to set 2015-16 budgets, DFID has set a target that country and regional programmes should account for 50% of DFID’s ICF spending by 2015-16.46 This amounts to a substantial change of direction. While it will help with mainstreaming climate investments into DFID country programmes, we have not seen a clear rationale for why this will deliver greater impact than the present multilateral channels.

3.36 We are concerned about the number of course corrections that have occurred over the life of the ICF (for example, the delay to establish an integrated, overarching theory of change and the heavy dependence on the MDBs as a delivery channel). While a measure of learning-by-doing was necessary, the on-going changes in emphasis suggest that pressure to spend quickly at the outset may have compromised strategy setting.

Financial oversight appears to be sound

3.37 Independent assessments have found that the ICF’s financial oversight of its partners is appropriate and in proportion to the level of risk. In 2012, the ICF was subject to an internal audit which identified a number of weaknesses. In a follow-up audit in 2013, these had been addressed. For example, new operational procedures for programme design and the prevention of fraud and corruption were introduced.

3.38 Multilateral climate funds (which have spent over £1 billion of ICF funds to date) use the financial management systems of the responsible MDB. DFID’s Multilateral Aid Review (MAR) demonstrated high confidence in their level of financial oversight.47 Earlier ICAI reviews of both the World Bank and Asian Development Bank scored Green-Amber overall. ICAI will be undertaking a further review of DFID’s engagement with the multilaterals in 2014-15.

3.39 At the portfolio level, there is a risk register that is reviewed at quarterly board meetings. Each risk is rated for probability and impact, with a corresponding mitigation plan. On the recommendation of the mid-term evaluation, the ICF is now developing a risk-reward matrix to track risks across the portfolio and inform risk management. The Mid-Term Evaluation found no cases of fraud and corruption relating to on-going programmes. Overall, we find the level of fiduciary control to be appropriate.

4 Findings: Impact

Impact

Assessment: Green-Amber

4.1 In this section, we consider the evidence of impact from the ICF’s programmes to date and the trajectory of the ICF as a whole. We examine impact at three levels: international, national and intervention.

There is clear evidence of ICF influence on international climate finance

4.2 The ICF has been a significant element of the UK’s international climate policy, supporting its negotiating position within the UNFCCC. The ICF has allowed the UK to be clear about its climate finance contribution between 2011 and 2016.

4.3 We find that the ICF has had a significant influence on international climate finance. Through its main multilateral channel, the CIFs, the ICF has supported new approaches to delivering climate finance at scale. As Annex A1 makes clear, after some adjustments, these programmes are beginning to deliver results. The ICF has blended concessional lending with grant funding and, in some cases, private finance to facilitate new types of investment.

4.4 These innovations in the delivery of large-scale climate finance have entailed a steep learning curve. This learning has been reflected in the design of new funds. For example, the Green Climate Fund (GCF) has been established under the UNFCCC, with the goal of taking on the good practices of existing funds and avoiding some of their mistakes. The design of the new GCF has borrowed extensively from the CIFs. It will support programmatic approaches to climate change, using a diversity of instruments to mobilise private investment, with an inclusive and gender-sensitive approach to programme development.48 As we discuss in paragraph 5.13 (on page 25) in Learning, the ICF has been an important player in facilitating this knowledge transfer.

We saw a range of emerging impacts at national level

4.5 The ICF is working with national governments to help them integrate climate change objectives into their national development plans, as well as providing finance for capacity building and individual investments. We saw early results from this engagement in both the countries we visited.

4.6 Indonesia is one of the key countries for climate change mitigation and, as a result, most of the multilateral instruments funded by the ICF are active there. The Government has made ambitious commitments to moving towards a low-carbon development pathway.49

4.7 Figure 12 on page 19 summarises our findings in Indonesia. Further information is provided in Annex A2. In summary, we found good evidence of positive national impact in the areas of land-use planning and forestry governance. ICF support to The Asia Foundation (TAF) is enabling changes in national, provincial and district legislation and law enforcement in the forestry sector. It is also directly assisting poor communities through recognition of their rights to land and forest resources.

4.8 In Ethiopia, where fewer global funds are active, the ICF has invested in a number of bilateral programmes. The Ethiopian Government has made a strong commitment to reducing its vulnerability to climate change through climate-resilient, carbon-neutral development and is recognised as a leader on the issue among African countries.50

4.9 This commitment is being well supported by ICF funding, complemented by policy dialogue with the DFID country office. DFID works in close partnership with both the Government and other climate finance partners, such as Norway and the World Bank.

The Climate Change Unit (CCU), run from the British Embassy in Jakarta, is working effectively but could link up better with multilateral programming. The CCU has good relations with the Government of Indonesia, donors, some CSOs and the private sector. While it is well placed to deliver the ICF, it would benefit from more expertise in the important low-carbon/clean energy sectors.

The Asia Foundation’s SETAPAK programme (meaning ‘pathway’ in Bahasa Indonesia) is improving the governance of land use and forestry, through £7.6 million in investments from November 2011 to March 2015. It is strengthening the rule of law, improving recognition of community rights and increasing transparency and accountability of land permitting. In East Kalimantan, we visited ICF programmes working with poor communities who depend on forest resources for their livelihoods. We found that the SETAPAK programme has also strengthened the voice of poor and indigenous peoples, through media outreach, regulatory reforms, freedom of information processes (now available to 2.3 million people in 6 districts), training of judges and support to the national anti-corruption agency. Though small in scale, the programme is producing multiplier effects by giving disadvantaged groups the ability to report infringements on their rights and interests. Six cases have so far been brought to the Corruption Eradication Commission.

4.10 The results that we observed in Ethiopia are summarised in Figure 13. At this stage, these are focussed mainly on putting in place national policies, legislation and financing instruments. In both countries, we found that a more joined-up approach across the ICF portfolio, including a combined tracking system for results, would enable greater impact.

There is evidence of early impact at the programme level

4.11 The results of our review of the 15 largest ICF programmes are presented in Annex A1.51 While many of these programmes are still at early stages, we nevertheless found evidence of a range of early results that are likely to lead to substantial impact in the future. The results are presented here under the three thematic areas of low-carbon development, adaptation and avoided deforestation.

The ICF is helping the Government to realise its Climate- Resilient Green Economy initiative, including through its support for the CRGE Facility as a window for coordinating climate finance from all sources. Wider impact may occur through the mainstreaming of the CRGE into the Government’s next five-year Growth and Transformation Plan. Support to the private sector and civil society is more limited and could be expanded.

At the local level, we saw a range of local impact, such as increased use of drought-resistant crops and planting methods.

Implementation has been slow to start under the low-carbon development theme (mitigation)

4.12 In many cases, implementation of low-carbon initiatives has been slower than expected, even after allowing for the longer time frames involved in these types of programmes. The ICF delivery partners have in some cases struggled to tailor their programmes to specific national needs and contexts.

4.13 An independent evaluation of the CIF found that its investments will over time deliver a substantial increase in the share of renewable energy generation capacity across its recipient countries – at least doubling and in some cases quadrupling their current installed renewable energy capacity.52 This offers the potential for significant transformational change (see Figure 14).

Low-carbon development programmes typically have up to a 30-year lifespan. Impact should increase dramatically once the major infrastructure investments are in place. The CTF is now in a position to deliver results on a much larger scale, having completed much of the early work on feasibility studies, planning, tendering and commissioning.

The ICF has also invested £63 million in the £668.8 million Global Environment Facility (GEF). This provides grants to help to develop new policies and institutions. The GEF often provides complementary support to larger CTF investment. In Ukraine, for example, the GEF supported the development of a renewable energy policy regime; the CTF is now providing low-cost finance to enable businesses to invest in the renewable energy opportunities created by this new policy regime.

Adaptation programmes are more directly addressing the needs of the poor

4.14 We found that the adaptation programmes focus on vulnerability and ensuring that the needs of the poor are addressed (see Figure 15). At country level, there is some encouraging evidence that the ICF is supporting integrated approaches to dealing with climate risk, as part of national development planning. For example, in Bangladesh, the ICF is supporting a bilateral adaptation programme that is raising awareness across government on climate change and creating linkages with disaster risk management programmes.

The ICF has also invested in the Adaptation Fund. This works directly through national institutions, including ministries of environment and NGOs, on practical adaptation initiatives. In Senegal, for example, the Adaptation Fund is supporting a coastal protection programme administered by the Centre de Suivi Ecologique (CSE), an NGO.

DFID’s long experience in forestry is supporting innovation and collaboration

4.15 We observed that the ICF’s forestry initiatives have drawn on long UK experience with strengthening forest governance and law enforcement (see Figure 16). While often politically challenging, this engagement is necessary in order to create the institutional capacity to slow the rate of deforestation.

The BioCarbon Fund has some promising approaches to engaging with the private sector. It is looking to partner with private companies that wish to strengthen their supply chains with more sustainable agriculture and forestry products. There may be an opportunity to link the business case with a cross-cutting ICF programme in Papua, Indonesia. The Papua programme proposes a plan for the implementation of spatial planning and low-carbon development. More joined-up support for this ambitious bilateral programme in Papua may improve effectiveness. Long-term multilateral support can provide continuity for this more limited time frame programme and strengthen coordination to work on the area that is politically sensitive and new to the UK.

Linking climate-related investments to poverty reduction

4.16 We found good evidence that the ICF’s investments in climate change mitigation and adaptation are also supporting international poverty reduction. There are, however, some tensions between the need for long-term investments, particularly infrastructure and the goal of achieving direct poverty reduction.

4.17 For example, large-scale, low-carbon development programmes have the potential to deliver significant long-term impact on climate change but necessarily take many years to show results. By contrast, short-term, smaller-scale initiatives, such as promoting clean cook stoves and solar lanterns, deliver immediate clean energy benefits to the poorest but more modest impacts on GHG emissions.

A more coherent approach to portfolio management could increase impact

4.18 In our country visit to Indonesia, we found missed opportunities for synergy and coherence between programmes with complementary aims. For example, advisors to the Indonesian Ministry of Finance were not aware of the Clean Technology Fund’s (CTF) US$400 million low-carbon investment programme.54 As a result, the technical assistance provided by bilateral programmes was not actively supporting the larger-scale investments being made through multilateral channels.

4.19 We also found that the multilateral Forest Investment Programme and the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility programmes in Indonesia have faced challenges as a result of poor stakeholder engagement and a lack of attention to governance. They would benefit from learning from ICF’s bilateral projects on forest governance, which are building on much stronger consultative processes.

4.20 Overall, there is a need for stronger portfolio management at the country level, to ensure that bilateral initiatives managed by country offices work effectively with multilateral programmes managed from the centre. In the most recent ICF bidding round, countries and regions are now required to submit their plans to the ICF Board, which should encourage a more considered approach to portfolio management.

Programmes are closely monitored but there is a need for more verification of results data

4.21 The ICF is actively monitoring its progress and tracking interim outputs. Its business cases include expected outcomes, based on available data sources, which are tested for bias and reduced to allow for error. ICF programme leads report every six months on progress and anticipated impact.

4.22 Expected and actual outcomes are generated through regular monitoring by ICF partners, either directly or through third party monitors. Data may also come from household surveys and management information systems in partner countries. We find that the accuracy of the programme data varies according to the quality of the data collection and management by the ICF partners. ICF programme managers are often several steps removed from the data collection process and have little influence over quality.

4.23 In the light of this, more third party verification of data would be appropriate. The ICF Board could also give greater attention to ensuring the consistency and rigour of programme monitoring and evaluation systems. These issues are recognised to some degree, as the ICF has recently approved a new initiative to strengthen its results and evidence processes. It is unfortunate that the Mid Term Evaluation (MTE) of the ICF proved to be poorly executed and was not able to address some of these points (see paragraphs 5.20-5.21 on page 29 in Learning). The issues of DFID’s design, commissioning and management of the MTE and its outcome do not materially affect the overall findings of this review. They do reflect on the resourcing and management of the evaluation function in DFID. This challenge has already been recognised by DFID in its Embedding Evaluation rapid review in February 2014.55 Similar issues were found by ICAI in its review How DFID Learns.56

5 Findings: Learning

Learning

Assessment: Green-Amber

5.1 This section considers how well the ICF is promoting learning at the global, country and fund levels. First, we assess whether the ICF is influencing the global climate finance architecture and supporting global knowledge. Second, we explore how well the ICF is supporting learning in priority countries. Third, we examine whether learning is bringing about the mainstreaming of climate change within development assistance. We consider whether lessons are being shared across government departments and the benefits of strategic investments in smaller projects. Finally, we consider the ICF results framework and reporting systems.

The ICF has promoted learning within key multilateral partners

5.2 The ICF is working to ensure that the MDBs incorporate an effective response to climate change into their investment portfolios. We saw, for example, that learning from the ICF has resulted in reforms to the CIFs in the areas of risk management, private sector engagement, gender equality, transparency, innovation and the use of results frameworks. Each CIF now has dedicated staff dealing with gender and risk, as well as strategies for engaging with the private sector. As a result of the ICF’s efforts, the CIFs have developed a range of learning products, some of them in partnership with leading analysts and think tanks. This is an early example of a transformational outcome for the ICF.

5.3 We also observed that learning from the ICF is being fed into the work of the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which is likely to become a leading channel for international climate finance in the coming period. The UK also participated in a small working group of GCF Board members to strengthen the GCF’s results framework. As a result, several indicators were agreed that either match or very closely resemble the ICF indicators.

5.4 We found, however, that more could be done to disseminate learning experiences, particularly at the level of practical difficulties with project implementation. For example, many early learning products related to the CIF focus on high-level objectives, often glossing over implementation challenges, in order to avoid creating an impression that programmes had not gone smoothly.57 Effective learning requires implementers to reflect on their failures, as well as their successes.

The ICF is supporting global knowledge initiatives

5.5 The ICF has invested in learning and research on climate and development issues, in keeping with its objective of building the global knowledge base. The work of the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN), described in Figure 17, has been particularly important. Through the CDKN, the ICF has helped to build an international network of climate change specialists, promote analytical work and influence policy development.

CDKN was established to offer developing countries better access to high-quality research and information relevant to climate change policies and programmes. It provides advice and services on demand, working in 74 developing countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. Our recent review of DFID’s use of contractors found this to be ‘a ground-breaking concept’.58 We also noted that 40% of CDKN’s work is being won by suppliers from developing countries. The Governments of Ghana and Kenya were early adopters of its services. Following a mid-term review, this programme has been extended to 2017.59

5.6 The ICF also supports regional and pan-African initiatives such as the African Climate Policy Centre, a hub for demand-led knowledge generation on climate change in Africa. This is summarised in Figure 18.

Its work to date includes support for Ethiopia, Tanzania and the Gambia to strengthen their hydro-meteorological monitoring systems and to integrate their climate records with satellite data. This will improve weather forecasting, including early warning of extreme weather events, as well as improve the quality and accuracy of weather and climate modelling. Efforts are being made to increase the use of this information in key sectors, starting with health (for example, malaria mapping).

The ICF supports learning in DFID priority countries

5.7 A key part of the ICF’s work in developing countries is the promotion of knowledge and learning. During our visit to Ethiopia, we saw how the ICF has worked with the DFID country office to help the Government realise its ambitious green economy strategy. The ICF has also prioritised support to Ethiopia’s Climate- Resilient Green Economy initiative (see Figure 19).

The ICF is helping to support the mainstreaming of climate into development

5.8 One of the ICF’s key objectives is ‘to mainstream climate change into development assistance’ – including in DFID’s bilateral aid programme. Its efforts are beginning to show results. The BRACED programme, for example, demonstrates a promising approach to merging climate change goals with other development priorities (see Figure 20).

Building on earlier learning, BRACED seeks to integrate disaster risk reduction and adaptation into its programme. Its approach also incorporates gender assessment (how these approaches impact on women and girls), beneficiary involvement (how to involve beneficiaries and stakeholders in design and implementation), community-friendly knowledge exchange mechanisms (such as local radio and SMS texts) and conflict sensitivity.60

5.9 The ICF recently developed a paper on mainstreaming climate funding within DFID’s activities.61 It highlights the benefits of considering climate change and development assistance jointly. A senior DFID official commented, ‘the ICF has given us a framework that has helped DFID to understand that building resilience to climate change is just good development’. We saw this thinking at work in our study of DFID’s livelihoods work in Odisha, India.62

5.10 DFID launched its ‘Future Fit’ programme in 2013. This seeks to ensure that building resilience to climate change is a core part of its operations. Under this initiative, ICF spending will be integrated more closely with DFID’s core programming in sectors such as food, water, energy and cities.

5.11 This mainstreaming approach is also apparent in DFID’s new Country Poverty Reduction Diagnostic tool.63 This treats resilience as an aspect of poverty and treats climate change as a key development risk. This will help country offices to link up climate change and poverty reduction. We saw evidence of this beginning to occur in Ethiopia (see Figure 21).

- the national social safety net programme, which responds to chronic food insecurity and short-term climate shocks such as droughts, is being made ‘climate smart’. This will strengthen its existing efforts to help the poor deal with the effects of climate change;

- the Private Enterprise programme, which provides access to finance for priority economic sectors, has been set a target of providing 20% of its funds to ‘green’ companies or activities; and

- a new programme to increase land tenure security and facilitate land market development is based on the assumption that more secure tenure will encourage smallholder farmers to invest in more environmentally sustainable practices.

The availability of ICF funding has helped to create incentives to engage with issues that were not previously prioritised.

5.12 We note that the Climate and Environment cadre in DFID has increased from 50 staff members in 2011 to approximately 65 in 2014. This increase in capacity should support the mainstreaming of climate issues, since the cadre works on both the ICF and other DFID programming. Joint management of the Climate Change and Wealth Creation teams is also supportive.

Lessons are being shared effectively between the three core departments and the FCO

5.13 We observed that the ICF has promoted increased understanding of the linkages between climate and development across DFID, DECC, Defra and the FCO. This is a good example of inter-departmental learning and compares well with the experiences of the Conflict Pool.64 All four departments work together on technical panels assessing proposals to the ICF. All four reported developing a clearer understanding of the benefits of and opportunities for addressing climate change, as a result of working on the ICF. Some positive examples of joined-up programming and lesson learning across departments include:

- DFID, Defra and DECC are working together on integrated policy-making.65 This includes using DFID country offices’ information and expertise. In Nepal, for example, the involvement of the DFID country office in discussions with the Government of Nepal and other stakeholders over the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility Carbon Fund has helped to inform policy engagement at the international level;

- ICF’s investment in the BioCarbon Fund was supported by joint DECC and Defra consideration, joint discussions with the World Bank (which administers the fund) and joint negotiations to join the fund. Both departments report that the cross-fertilisation of ideas was useful;

- DECC and DFID work closely together on the Climate Public Private Partnership (CP3),66 including setting the investment framework, selecting the fund manager and maintaining the risk register; and

- in Uganda, DECC (68%) and DFID (32%) have jointly allocated £34.6 million to catalyse private investment in small-scale renewable energy projects through the GET FiT programme. The programme consists of a combination of financial incentives, risk guarantees, technical assistance and capacity-building support to the Ugandan energy regulatory authority.

Small investments in knowledge can at times deliver large impacts

5.14 While we recognise that the efficiencies of large-scale spending are attractive for an instrument like the ICF, it is our view that some of the smaller programmes in the portfolio have the potential for significant impact. The 2050 Calculator is an example of a small investment delivering widespread impact (see Figure 22). It is important that, alongside its large-scale programmes, the ICF retains the flexibility to support smaller, strategic interventions. There is a risk that this capacity is lost in the move towards larger investments.

The ICF results framework

5.15 Like other climate funds, the ICF has found the measurement of aggregate results across its portfolio to be a major challenge. It has now developed an overall results framework that continues to evolve in the light of lessons learned. We found this to be a good example of adaptive learning.

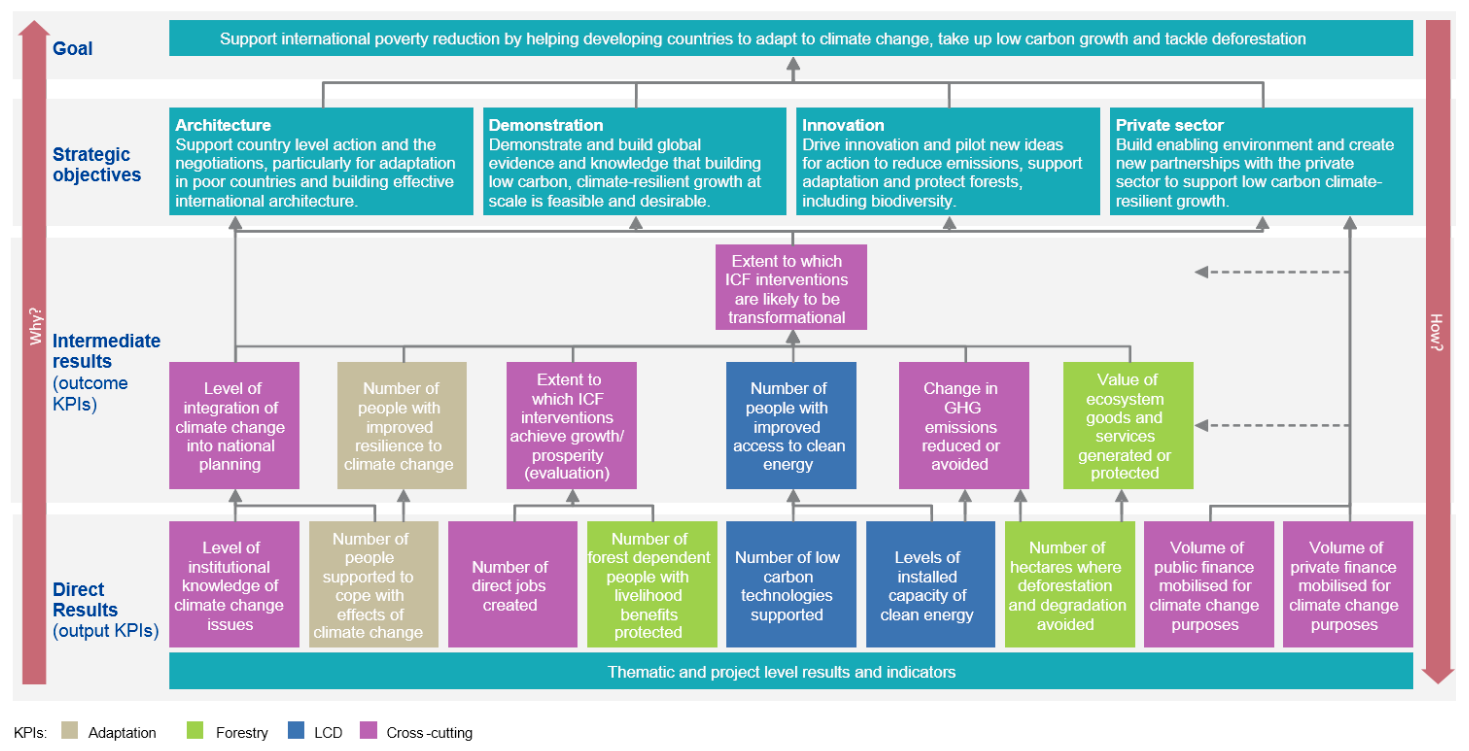

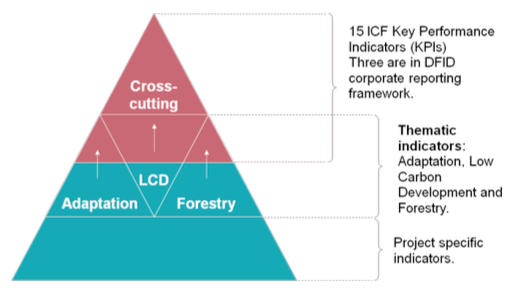

5.16 Approved in July 2012, the results framework (see Figure 24 on page 28) reflects the ICF’s theory of change, with 15 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) spanning its thematic and cross-cutting areas. The KPIs capture both immediate impacts and progress towards longer-term goals. While results measurement in areas such as climate change adaptation is challenging, the ICF is taking an iterative approach to developing its methodology. For example, its approach to measuring the KPI on ‘transformation’ is being tested in Kenya, before being introduced at the portfolio level.

5.17 Each ICF project reports on its own individual performance indicators and should be able to report on at least one KPI. Although they do not capture all results, the KPIs enable results from over 120 programmes to be aggregated and communicated in a way that would not be possible through project and programme-level indicators alone. The table of ICF achieved and expected outcomes is at Figure 26 on page 31.

The calculator has been replicated by several developed and developing countries as it is such a useful tool. These include:

- China in 2012 (China 2050 Calculator, English language version and China 2050 Calculator, Chinese language version);

- South Korea in 2013 (My2050 simulation);

- Taiwan in 2013 (the Taiwanese Ministry of Economic Affairs and the Industrial Technology Research Institute published their calculator as an Excel spreadsheet);

- India in 2014 (India Energy Security Scenarios 2047);

- South Africa in 2014 (South Africa 2050 Calculator webtool); and

- Belgium in 2011 (the Wallonia 2050 Pathways analysis).

The Calculator won the 2013 Analysis and Use of Evidence Civil Service Award for the joint DECC and FCO team.67

How the ICF measures adaptation impact

5.18 The reporting in the results framework finds that, under Adaptation, 3.2 million people have already been supported to cope with the effects of climate change. How the ICF defines ‘support’ has been the subject of detailed work, illustrated in Figure 23. There is an improved understanding of the methodological challenges related to monitoring and evaluation that are particularly relevant for adaptation. A recent DAC paper highlights the three key challenges:68

- assessing attribution;

- establishing baselines and targets; and

- dealing with long-term time horizons.

5.19 The ICF results framework has shaped DFID’s corporate reporting framework, which supports the mainstreaming of climate change into UK development assistance. ICF KPIs – including the numbers of people supported to cope with the effects of climate change and who have improved access to clean energy and the total area where deforestation has been reduced – are included in DFID’s Departmental Reporting Framework (DRF).69 Figure 25 on page 29 presents the nested performance framework, which captures relationships between these different indicators.70

Targeted: defined as whether people (or households) can be identified by the programme as receiving direct support, can be counted individually and are aware they are receiving support in some form. This implies a high degree of attribution to the programme; and

Intensity: defined as the level of support/effort provided per person, on a continuum but broad levels may be defined as:

- Low: for example, people falling within an administrative area of an institution (such as Ministry or local authority) receiving capacity building support or people within a catchment area of a river basin subject to a water resources management plan;

- Medium: for example, people receiving information services such as a flood warning or weather forecast by text, people within a catchment area of structural flood defences, people living in a community where other members have been trained in emergency flood response; and

- High: for example, houses raised on plinths, cash transfers, agricultural extension services, training of individuals in communities to develop emergency plans.

There are two categories for reporting:

Direct: targeted and high intensity. This must fulfil both criteria, for example people receiving social protection cash transfers, houses raised on plinths, agricultural extension services, training of individuals in communities to develop emergency plans and use early warning systems; and

Indirect: this covers targeted and medium intensity, for example, people receiving weather information and text message early warnings.

5.20 The ICF commissioned a Mid Term Evaluation (MTE) in 2013. As of November 2014, it was clear that there were still weaknesses in the MTE. The ICF has decided to publish the MTE, with a UK Government assessment and separate commentary by the Advisory Panel.71 At the time of the publication of our report, we have been informed by DFID that the UK Government assessment will include text which states that, although it will publish this report for transparency, it is not satisfied that the report meets the standards DFID requires from formal independent evaluations. For this reason, less weight should be put on the report than on evaluations that do meet the minimum standards; DFID does not consider this an evaluation as normally defined. According to DFID’s evaluation policy, its programmes need to be evaluated in accordance with the standards recommended by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee. The ICF does not have an MTE that meets this standard: a situation which requires significant improvement and which would attract an Amber-Red rating for Learning, were the MTE to be the only form of learning applied to the ICF. This outcome increases the need for a comprehensive evaluation at the end of the ICF cycle, for example including verification of the Results Framework reporting. The Terms of Reference for this will need to reflect better the scope and nature of the portfolio and the availability of impact information and data.

5.21 The challenges encountered by the MTE (and this review) are common across climate funds, for example portfolio analysis, establishing baselines and data availability.72 Given the many technical challenges involved in measuring progress on climate change, the ICF has been active in promoting new approaches at the international level. It has commissioned research and stakeholder engagement on how to monitor and evaluate climate finance across more than 25 institutions and countries.73 In 2011, DECC and DFID commissioned PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) to prepare a low-carbon development results framework for the ICF. This was then used to promote international agreement on a range of indicators.74 On adaptation, work has been done to prepare a tracking and measuring development framework, which is being tested in Nepal, Kenya, Ethiopia, Mozambique and Pakistan.75 As a result, there is increasing convergence of concepts and approaches across funders, which is being captured by the OECD.76 The ICF has recently put in place a further programme, the Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Programme, to support its work in this area. This is not before time, given the need to establish what works and why and improve monitoring, verification and benchmarking.

The ICF needs to become more visible

5.22 We found that the ICF would benefit from becoming more visible and transparent in its operations. The ICF’s approaches, programmes and projects are not readily available online in a single place. We found it surprising that the ICF has no dedicated website accessible to the public. It is also difficult to identify ICF-supported programmes in published budgets. A number of civil society and private sector actors expressed to us their frustration in trying to understand and engage with the ICF. Greater visibility and transparency would increase accountability and reduce misunderstanding.

| Section | Achieved outcomes against KPIs by March 2014 | Expected outcomes by 201577 | Lifetime expected outcomes based on current estimates78 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation KPI | |||

| 2.1 | 3.2 million people directly supported to cope with effects of climate change. | 18 million people | 29 million people |

| 2.2 | Methodology for the number of people whose resilience has improved is still under development. | ||

| Low-carbon Development KPI | |||

| 3.1 | 550,000 people with improved access to clean energy. | 1.7 million people | 25 million people |

| 3.2 | 9,000 units of low-carbon technologies installed. | 240,000 units | 4 million units |

| 3.3 | Not yet reporting against the level of installed capacity of clean energy. | ||

| Forestry KPI | |||

| 4.1 | Methodology for the number of forest dependent people with livelihood benefits protected or improved is still under development. | ||

| 4.2 | Methodology for the number of hectares where deforestation and degradation have been avoided is still under development. | ||

| Cross-cutting KPI | |||

| 5.1 | 15,000 jobs created. | 29,000 jobs | 50,000 jobs |

| 5.2 | 1.4 million metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2Eq) reduced or avoided. | 4.6 million tonnes | 150 million tonnes |

| 5.3 | £800 million of public finance mobilised. | £900 million | £2,600 million |

| 5.4 | £113 million of private finance mobilised. | £270 million | £2,200 million |

| 5.5 | Methodology for the value of ecosystems services generated/protected is still under development. |

6 Conclusions and Recommendations