Review of UK Development Assistance for Security and Justice a

Executive Summary

Security and justice (S&J) assistance, including support for policing, courts and community justice, is an increasingly important part of the UK aid portfolio. In 2013-14, it accounted for £95 million in expenditure, across DFID and the Conflict Pool. In this strategic review of the UK S&J assistance portfolio, we examined S&J programmes in 10 countries, including through visits to Malawi and Bangladesh. We looked mainly at DFID’s assistance, together with the question of coherence and coordination across the UK Government. We paid particular attention to whether the portfolio is addressing the needs of women and girls.

[table “x818” not found /]Overall

Assessment: Amber-Red

Security and justice are important development goals and a high priority for poor people around the world. DFID was an early champion of S&J assistance but its portfolio has fallen into conventional patterns and needs refreshing. DFID focusses on S&J primarily as a service, rather than as a set of issues or practical challenges, leading it to concentrate on the reform and capacity-building of service providers, particularly police. While there are pockets of success, there is little sign that its institutional development work is leading to wider improvements in S&J outcomes for the poor. DFID does, however, have a good base of programming on community justice and for women and girls, on which it can build. Overall, we are concerned that the portfolio suffers from a lack of management attention, leading to unclear objectives and poor supervision of implementers.

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

DFID has no overarching strategy for its S&J assistance and its approach to the portfolio has changed little in recent years. This has led to the repetition of a standard set of interventions across very different country contexts. The use of empirical evidence and contextual analysis is often weak and poorly linked to programme designs. Some DFID advisers report feeling under pressure to over-promise on results, leading to unrealistic programmes. There is, however, a strong focus on women and girls in newer programmes, with a range of innovative new approaches.

Delivery

Assessment: Amber-Red

While DFID generally makes sound choices of delivery channels, its supervision of implementing partners is inconsistent. Programme components are not managed as integrated portfolios. Implementers feel under pressure to deliver wide geographical coverage, resulting in programmes that are spread too thinly to achieve sustainable results. DFID’s procurement of contractors is causing a range of problems, including long delays and rigid or unrealistic programme designs. We saw instances of high quality delivery by non-governmental organisations (NGOs), who may offer greater local knowledge and legitimacy than contractors but often find it difficult to compete in procurement processes. The UK Government has recognised the importance of assessing human rights risks in S&J assistance but needs clearer principles on risk management.

Impact

Assessment: Amber-Red

We found a mixed pattern of results across the portfolio. Attempts to build the capacity of central S&J institutions are not translating into better or more accessible services for the poor. In the policing sphere, common reform strategies, such as building model police stations and community policing pilots, are producing, at best, isolated results that are not scalable or sustainable. The assistance is more effective when it focusses on addressing specific S&J challenges, such as excessive pre-trial detention. There are also promising results from community justice initiatives, with women and girls as the main beneficiaries, although we have concerns as to how DFID goes about scaling up these activities. Little attention is being given to sustainability, at either the financial or political levels.

Learning

Assessment: Amber-Red

In an area where the evidence base is known to be limited, we find that DFID does not have an active learning approach to the portfolio and is repeating approaches with a poor track record of results. It has a range of useful central initiatives on knowledge management but these are not being used to challenge or shape country programming. The quality of monitoring and results data is often poor and there has been little use of independent evaluation in recent years.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: DFID should develop a new strategy for more focussed and realistic security and justice assistance that emphasises tackling specific security and justice challenges in particular and local contexts. This should include working in a cross-disciplinary way to address wider security and justice themes, such as gender equality (including working with men), labour rights and urban insecurity.

Recommendation 2: DFID should identify the key evidence gaps across its security and justice portfolio and tailor its investments in research and innovation to fill those gaps. It should develop guidelines on how to ground programme design in sound contextual analysis and evidence of what works and on how to strengthen programme oversight, including management of political risk.

1 Introduction

Scope and purpose

1.1 Development assistance for security and justice (S&J) – namely, support for policing, judicial systems, community justice and related initiatives – is an increasingly important part of the UK aid programme. In recent years, the UK has funded substantial S&J programmes in 16 countries and smaller activities in a number of others. Commitments have increased in number and size and, with more of the UK’s bilateral aid devoted to fragile and conflict-affected states, this trend is likely to continue.

S&J is not organised as a single sector, like health or education, with a lead ministry. Rather, it is a cluster of systems involving multiple independent agencies (courts, prosecutors, police, corrections services) with different cultures and interests and, in many cases, little incentive to collaborate.

Inefficiencies in the delivery of S&J services lend themselves to corruption and rent-seeking, creating strong vested interests that resist reform.

The poor face major barriers to accessing security and justice services. They are often remote, especially from rural communities. The costs of travel, accommodation, fees (formal or informal) and lawyers can be prohibitive. Formal proceedings conducted in an unfamiliar language can be intimidating, while corruption is often pervasive.

Developing countries show high levels of legal pluralism, with formal S&J institutions working alongside traditional or informal S&J processes that may or may not have formal legal authority. These informal mechanisms are more accessible to the poor and are often viewed as more legitimate.

Formal and informal S&J institutions alike share a deep-seated bias against women and tend to favour the interests of the wealthy and powerful rather than of the poor.

The concentration of UK S&J programming in fragile and conflict-affected states gives rise to a volatile environment for programme delivery. In recent years, DFID programmes have been cancelled or interrupted due to conflict (South Sudan, Libya), loss of political support (Ethiopia), human rights concerns (Democratic Republic of Congo) and a public health crisis (Sierra Leone).

The evidence base for S&J programming is generally acknowledged to be weak. According to the DFID-funded Governance and Social Development Resource Centre topic guide on S&J, ‘much of the literature is normative, presenting recommendations with little empirical evidence about what works. There is little in the way of rigorous evaluation on the effects of institutional reform programmes on security and justice provision.’1

1.2 We decided, therefore, to conduct a thematic review of the UK S&J assistance portfolio. Our review covers policies and strategies, patterns in programme design, delivery arrangements and the generation of knowledge to inform programming. While we cannot quantify results across the portfolio as a whole, we assess impact through a series of case studies to assess which types of S&J assistance are delivering on their intended objectives.

1.3 While our focus is primarily on programmes funded by the Department for International Development (DFID), we have also looked at some Conflict Pool projects and at how various UK Government departments and agencies collaborate on the delivery of S&J assistance. Our scope is limited to activities that qualify as official development assistance (ODA). This excludes some aspects of UK S&J assistance, such as support for counter-terrorism and to the military.

1.4 As a cross-cutting theme for the review, we have chosen to look at how well the portfolio delivers results for women and girls. DFID has made an overall commitment to providing 10 million women and girls with improved access to S&J services.2 We assess whether DFID’s programming reliably identifies the S&J needs of women and girls in particular contexts and whether it is able to overcome the challenges they face in accessing quality S&J services. We have not, however, limited our enquiry to programming that explicitly targets women and girls. Rather, we take the perspective of women and girls in assessing whether the portfolio as a whole is delivering meaningful changes to S&J services and outcomes. We have looked at DFID programming on violence against women and girls only in the S&J arena, not in other areas such as civil society support.

Methodology

1.5 Our methodology consisted of six main elements.

- We commissioned a literature review on the challenges of delivering improved S&J for women and girls. It focussed on identifying the S&J needs of women and girls, on the entry points for S&J programming and on common obstacles to delivering improved S&J outcomes for women and girls. The literature review was carried out by staff of the Overseas Development Institute. This review also drew extensively on other literature, including empirical studies of what works in S&J programming (see Figure 1 on page 2 for some key issues emerging from the literature).

- We carried out a strategic assessment of DFID’s overall approach to S&J assistance. This included:

- reviewing relevant policies, strategies and guidance;

- dialogue with the S&J Team in DFID’s Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department (CHASE), which provided a series of briefing notes on different aspects of S&J assistance;

- interviews with other DFID teams and the cross-departmental Stabilisation Unit;

- interviews with UK development non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with DFID Programme Partnership Agreements that are active in the S&J area and a consultation meeting with other NGOs organised through the network organisation Bond;

- consultations with UK-based academic experts;

- consultations with companies and consultants involved in the design, delivery or review of UK S&J programmes;

- consultation with UN NGOs active on security, justice and violence against women; and

- a review of how DFID measures results across the portfolio.

- We carried out desk reviews of a sample of eight current or recently completed DFID and Conflict Pool S&J programmes. The sample covered programmes in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Libya, Nepal, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Sri Lanka and Sudan. The sample was not random; rather, it was chosen to cover a cross-section of programming in terms of scope, duration, region, country context (post-conflict, fragile and other), implementing partner (companies, NGOs and multilateral agencies) and funding source (DFID and the Conflict Pool). For each programme, we reviewed programme design documents and related analytical work, results frameworks, annual reviews and any external assessments. Where possible, we also looked at prior programmes in that country. We conducted telephone interviews with the responsible DFID staff, implementing partners and, where possible, consultants or Stabilisation Unit advisers involved in design work or reviews. We identified recurring patterns in programme activities and in reported results.

- We reviewed DFID’s approach to innovation and knowledge management. This included desk reviews of a range of programmes and initiatives managed by the CHASE S&J Team or DFID’s Research and Evidence Division, including on technical support, innovation, strategic partnerships and research. We assessed DFID’s approach to converting its knowledge pool into informed programming choices.

- We assessed the level of co-ordination and coherence across the UK Government in the international S&J assistance field. We consulted with a number of sections in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), the Stabilisation Unit, the Ministry of Defence, the Home Office, the Ministry of Justice, the Crown Prosecution Service and the National Crime Agency. We spoke to various stakeholders about the development of National Security Council country strategies and the design of the new Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF). We considered how UK security and other policy interests influence the approach to S&J assistance. We also looked at the experience of involving other UK Government departments and agencies in the delivery of S&J programmes.

- Finally, we carried out detailed case studies of the full range of UK S&J programmes in Bangladesh and Malawi. Our original intention had been to visit Sierra Leone but this proved impossible due to the Ebola epidemic. We responded by making Sierra Leone a desk study and elevating Malawi from a desk study to a full case study. Bangladesh and Malawi have both received more than one generation of S&J programming, allowing us to examine the cumulative results of sustained DFID support. Along with many countries in which DFID works, they have acute problems of violence against women and girls, which is, in turn, a significant focus of DFID’s programming (see Figure 2 on page 5).

1.6 In two-week visits to each case-study country, we consulted with DFID, programme implementers and counterparts, interviewed a range of independent observers, visited project sites and consulted with intended beneficiaries.3 We reviewed the results of surveys and other monitoring tools used by the programmes. Our beneficiary consultations took the form of community meetings, focus groups and individual interviews, including taking case histories from individual users of services supported by UK programmes. The data collected was qualitative in nature. It enabled us to test the plausibility of results reported by the programmes we reviewed and to assess their relevance to the needs of beneficiary communities. Our findings on impact are drawn mainly from DFID’s own results data, as generated by the programmes, supplemented by our own observations and findings.

1.7 Altogether, through desk reviews and case studies, our review covered nine of the largest current DFID S&J programmes (see Figure 4 on page 6).

1.8 We have also drawn on the findings of other ICAI reports. In 2013, we reviewed DFID S&J programming in Nepal4 and in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.5 We examined a DFID justice programme in Nigeria as part of our second review on anti-corruption programming6 and a security sector and policing programming in DRC in our review of the scaling up of DFID assistance to fragile states.7 The findings of these reviews formed part of the desk review component of our work for this report.

1.9 The review was carried out by an international team of S&J specialists, supported by local experts in Bangladesh and Malawi.

In Bangladesh, for instance, approximately 60% of ever-married women report lifetime physical or sexual violence.8 In 2010, dowry-related violence – where a husband abuses his wife in order to extort dowry payments from the wife’s family – was the most common form of violence that women report to police.9 Adolescent girls are also acutely at risk. They are five times more likely to be abused than women aged 40–49 and are also the most common victims of acid attacks.10 Yet despite the obvious need for security and justice services, women and girls face an array of barriers when accessing services. People from poor communities find approaching police stations or the formal justice system intimidating and are frequently deterred from pursuing justice by the lengthy delays and high costs of the system. Even where they overcome the barriers to access, they are often denied justice. For instance, with an Evidence Act dating from 1872, forensic evidence is not admissible in Bangladeshi courts and abusive practices such as the ‘two finger test’, used to examine girls reporting cases of rape, remain commonplace. The criminal justice system is highly inefficient, with many people accused of crime spending longer awaiting trial than the maximum sentence for the offence of which they are accused.

In Malawi, in addition to a highly inefficient justice system, women and girls face wide-ranging abuse and discrimination. One in five girls experiences sexual abuse before the age of 18,11 while almost half of women experience physical or other abuse at the hands of an intimate partner.12 Women are commonly dispossessed of their land following divorce or the death of their husband, cutting off their livelihoods and making them more vulnerable to violence. Girls face egregious forms of harmful cultural practices, including a form of initiation that requires them to engage in sexual relations with older men. Yet Malawi has very limited budgetary resources to spend on policing and the criminal justice system remains highly inefficient, with long case backlogs.

Overview of DFID’s S&J portfolio

1.10 The UK’s major S&J assistance programmes are funded by DFID through the bilateral aid programme. In addition, the tri-departmental Conflict Pool funds a significant number of smaller S&J projects, oriented towards ensuring stability in fragile or conflict-affected countries. The FCO has a number of strategic programmes on S&J themes, including on human rights and counter-terrorism, while some of the UK Government’s domestic S&J agencies, including the Crown Prosecution Service and the National Crime Agency, have a range of international assistance activities.

1.11 DFID’s expenditure on S&J assistance is not separately identified in its management information system. As a result, there are no exact figures available on the amount that DFID spends. A reasonably accurate picture can be gained, however, by looking at two ‘input sector’ codes: ‘security sector management and reform’, which includes support for police; and ‘legal and judicial development’, which includes programmes working with the judicial system and community justice.13

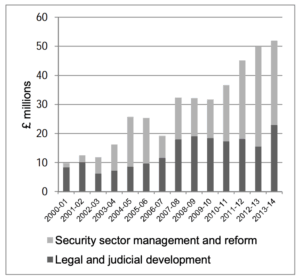

1.12 The data shows that the portfolio has grown from around £10 million in annual expenditure in 2000-01 to £53 million today (see Figure 3 on page 6). Expenditure on legal and judicial development was stable or on a slightly declining trend from 2007-08 until 2013-14, when it increased again. Expenditure on security sector management and reform (including policing) has risen substantially over the past five years. In 2013-14, S&J accounted for 7% of DFID’s total expenditure on ‘governance and civil society’.

1.13 Figure 4 provides a list of the largest current DFID S&J programmes by lifetime budget (although DRC and Ethiopia are currently suspended and Libya has been heavily curtailed). In recent years, there has been a trend towards more and higher value programmes, reflecting the increasing prominence of fragile and conflict-affected states in the UK bilateral aid programme.

1.14 Most of DFID’s S&J portfolio is focussed on criminal justice, with a concentration of funding on policing. There is also a substantial strand of programming on community justice, which can include supporting paralegal services, informal dispute resolution and ‘legal empowerment’ (empowering communities to use the justice system to claim their rights). There is less support for the formal justice sector and for civil justice. In recent times, DFID has begun to explore wider justice themes linked to the Prime Minister’s ‘golden thread’ agenda15 (see Figure 5 on page 10), including land tenure, economic law and commercial justice. Programming in these areas, however, remains small.

1.15 DFID also engages in international advocacy on S&J. In recent years, it has lobbied in international forums, such as the United Nations, to secure the inclusion of S&J goals in the post-2015 international development agenda.

Source: Data provided by DFID. Notes: The list includes only programmes that are predominantly directed towards security sector reform, policing and formal and community justice. Programmes in DRC and Ethiopia are currently suspended, while the Libya programme has been curtailed. The Afghanistan programme is only one of a number of UK S&J programmes in that country, funded through other channels. Programmes shaded grey are covered in our review sample.

* A Conflict Pool programme, with a £32.3m contribution from DFID.

Other UK S&J assistance

1.16 According to figures provided by DFID, the Conflict Pool spent £42.4 million on S&J programming in 2013-14 (excluding the Security, Justice and Defence Programme in Libya, which also appears in DFID’s figures). We note, however, that this sum uses a broader definition of S&J and includes expenditure that is not ODA-eligible, such as training for military forces.

1.17 Most Conflict Pool projects are much smaller than DFID’s programmes; in 2013-14, there were 116 projects, with an average budget of £365,000, as compared to an average DFID S&J programme of £20 million. Most Conflict Pool projects are implemented directly by the UK Government, NGOs or individual consultants, with only a small number tendered out for commercial delivery.

1.18 In 2015, the Conflict Pool will be replaced by the new CSSF, with an increased budget. The CSSF will fund activities in support of National Security Council country strategies, with the priorities decided by inter-departmental regional and country programme boards. This is part of a UK Government initiative to improve the co-ordination of UK engagement in strategically important countries. It is an important part of the strategic backdrop to UK S&J assistance.

1.19 We reviewed the Conflict Pool in 2012 and identified a range of issues regarding programming practices and results management.16 We have not repeated that assessment in this review.

1.20 The FCO also has a range of strategic programmes that fund S&J assistance. Its Counter-Terrorism Fund has an annual budget of £15 million, with a £7 million ODA target. The UK Government has a policy against co-operating on counter-terrorism with other countries where it is likely to lead to torture or abuse of suspects.17 S&J assistance under this fund goes to a number of countries to help them to develop the capacity to investigate, detain and try counter-terrorism suspects in accordance with human rights principles.

1.21 The FCO also has a Human Rights and Democracy Programme, of £6 million annually, which provides small grants to promote international human rights standards, including advocacy against torture and the death penalty. In recent years, part of this fund has been used to support the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative. In April 2013, under the UK Presidency, the G8 group of nations issued a Declaration that no post-conflict amnesty may be granted to people who have ordered or carried out rape.18 The Declaration has been endorsed by 155 countries. It was followed by a Global Summit in London in June 2014, hosted by the Foreign Secretary and UN Special Envoy Angelina Jolie.19

1.22 Other UK departments and agencies are active in international S&J assistance on a small scale, as implementers of programmes funded by others. The Ministry of Justice and the Home Office have a joint project team that implements European Union (EU) ‘twinning projects’ on justice and home affairs in EU accession countries. The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has around 20 officers abroad, helping to strengthen the capacity of criminal justice systems in areas such as asset recovery and fighting organised crime. It helped to deliver a DFID programme in Sierra Leone on criminal justice. The National Crime Agency (NCA) has a substantial overseas network engaged in both operational matters and in capacity building of partners. Both the CPS and the NCA have played roles in the implementation of Conflict Pool and DFID programmes.

1.23 The Stabilisation Unit is also an important part of the UK institutional architecture for S&J assistance. It is a tri-departmental unit, established by DFID, the FCO and the MOD in 2004, to boost the UK Government’s capacity to respond to instability overseas. It supports the rapid deployment of UK expertise in support of stabilisation. It has a Security and Justice Group, including a core team of experts and a roster of Senior S&J Advisers, which provides technical support to the UK Government on the design and delivery of S&J interventions. The Group supports DFID with the scoping, design and monitoring of its S&J programmes in a number of countries, as well as developing lesson-learning documents, such as its 2014 Policing the Context paper.20

2 Findings: Objectives

2.1 Chapters 2 to 5 present the findings of our review against the ICAI assessment framework, covering objectives, delivery, impact and learning. The ratings in this review relate to the S&J portfolio as a whole.

Objectives

Assessment: Amber-Red

2.2 This section reviews the objectives of UK S&J assistance, the quality of programme design and the level of coherence across UK Government agencies. We begin by looking at the policy goals underlying the S&J portfolio and whether there are strategies in place for delivering them in different country contexts. We then look at recurring patterns in the design of S&J programmes.

UK S&J assistance supports multiple, overlapping policy interests

2.3 The UK Government has a wide variety of policy goals that bear upon S&J. For DFID, the primary goal is to address poverty by reducing the vulnerability of the poor to insecurity and injustice. Its 1997 White Paper was an early statement of this goal, noting that ‘poor people, particularly women, are the most vulnerable to all forms of violence and abuse… because in very many cases systems of justice and government services do not fully extend to them’.21 A number of DFID documents22 cite the World Bank’s influential ‘Voices of the Poor’ study from 1999,23 which found that insecurity and injustice are major concerns for poor people, of equal importance to hunger, unemployment and the lack of safe drinking water.

2.4 DFID also cites S&J assistance as a means of strengthening governance in developing countries, by promoting the accountability of government officials to the poor. According to a May 2008 paper, an effective justice system ‘is a guarantor of the rule of law, an essential element of democratic politics.’24 This was, in turn, incorporated into DFID’s approach to state-building in post-conflict countries. Security, law and justice were defined as ‘core state functions’ which are essential for all states if they are to ‘govern their territories and operate at the most basic level’.25

2.5 S&J assistance also supports conflict reduction. The UK has been a strong champion of including security within the international development agenda, based in large part on its experiences of intervening in the Sierra Leone conflict from 1996 onwards. DFID has been very influential in establishing security sector reform as a discrete area of development assistance, covering the restoration of civilian law enforcement, democratic control over the armed forces and the disarming and demobilising of former combatants.26 In 1999, DFID prepared a policy statement on Poverty and the Security Sector, drawing the link between insecurity and poverty.27

2.6 More recently, the Prime Minister’s ‘golden thread’ agenda makes reference to the rule of law as underpinning peace, open societies and economies, which are necessary in order to address the underlying causes of poverty28 (see Figure 5 on page 10).

2.7 The 2011 Building Stability Overseas Strategy,29 issued jointly by the FCO, the MOD and DFID, made the case that S&J provision is an important part of promoting stability overseas. There are also more specific UK interests at stake. The Prevent Strategy notes the importance of effective criminal justice systems in countering radicalisation and preventing terrorism.30 The Serious and Organised Crime Strategy, likewise, notes the importance of building capacity in criminal justice in developing countries, in order to ensure effective collaboration in the fight against global crime.31

In the S&J field, the ‘golden thread’ policy initiative has led to a renewed interest in the rule of law as a constitutional principle, with a programme of policy development, research and advocacy led by DFID’s Governance, Open Societies and Anti-Corruption Department. It has also led to more emphasis on property rights and economic law, with the Growth and Resilience Department pulling together various strands of existing work.

DFID has also been encouraged by the Secretary of State to make more use of UK legal expertise to support S&J development abroad. It has provided £2.6 million for the Rule of Law Expertise UK programme,33 which is a mechanism for sharing best practice and funding the overseas deployment of legal experts from the UK Government and the legal profession

2.8 There are, therefore, multiple, overlapping UK policy agendas in the S&J arena, including poverty reduction, good governance, state-building, conflict reduction, the golden thread and UK national interests. With so many policy objectives at play, it can be difficult at times to identify which objective UK S&J assistance is pursuing at any given point.

The DFID S&J portfolio shows signs of strategic drift

2.9 With the exception of the agenda to tackle violence against women and girls, discussed below in paragraph 2.27, there has been little development of S&J policy or strategy in recent years. The clearest statement of DFID’s current approach is found in its July 2009 White Paper, where it committed to treating S&J as ‘a basic service’, on a par with health or education.34 This helped to unify the various S&J activities under a common idea and to mainstream them within an aid programme that was, at that point, oriented towards service delivery for the Millennium Development Goals.

2.10 As a strategy, however, it also has its limitations. The emphasis on service delivery steers DFID towards a widespread assumption that the solution to insecurity and injustice, as experienced by the poor, is strengthening a specific set of S&J institutions and services, such as policing, courts and local tribunals. It works against approaching S&J as a set of social issues – for example, land tenure, labour rights or urban insecurity – requiring broad, multi-pronged interventions to address. Some of the experts whom we consulted stressed that poor people’s experiences of S&J have more to do with surrounding socio-economic conditions and cultural norms, than with the quality or accessibility of S&J services. As one NGO expert put it to us, ‘You don’t necessarily get security by doing security’. We saw good evidence of this broader, multidisciplinary approach in DFID’s programming on violence against women and girls but less in other areas of the S&J portfolio.

2.11 Most of DFID’s S&J portfolio focuses on the strengthening of S&J institutions as its starting point, rather than the need to address specific problems of insecurity or injustice. In our view, the portfolio would be strengthened by more attention to problem solving. A problem-solving approach entails multiple reinforcing interventions to tackle specific S&J challenges in particular locations or for particular groups of beneficiaries. It entails finding localised solutions and developing partnerships among different authorities and community groups. We see some signs of a move towards this in recent programme designs, such as the (now suspended) Ethiopia programme.35 This has not, however, been clearly articulated as a strategy.

2.12 Beyond the idea of treating S&J as a service, DFID has no explicit strategy for the portfolio and little in the way of updated policies or approaches. We encountered little consensus, within DFID or among practitioners, as to which services to prioritise or what it takes to improve them.

2.13 DFID informs us that it has chosen not to develop an overarching strategy for its S&J assistance, preferring to allow country offices to identify their own solutions to local challenges and opportunities, in order to respond to context. In the absence of clear guidance, however, we found that DFID S&J programmes tend to be fairly similar in composition, suggesting a lack of adaptation to context.

S&J programmes are based on a menu of conventional activities

2.14 DFID S&J programmes appear to be constructed from a menu of conventional components, generally without a strong theory of change. There is limited variation in the mix of activities across countries, despite very different contexts.

2.15 Figure 6 shows the recurrent elements across the ten programmes in our sample. Some of this repetition comes from successful activities that have been replicated across countries. For example, the use of paralegals to tackle excessive pre-trial detention, which has worked well in Malawi, was taken to both Sierra Leone and Bangladesh – including using a Malawian NGO to deliver the training.

Key: 1 = Bangladesh; 2 = DRC; 3 = Ethiopia; 4 = Libya; 5 = Malawi; 6 = Nepal; 7 = Nigeria; 8 = Sudan; 9 = Sierra Leone; 10 = Sri Lanka

Source: Synthesis from programme documents and interviews.

2.16 Other activities, however, recur across the portfolio without due consideration of their track record or their suitability to different country contexts. For example, DFID’s approach to community policing focusses more on supporting police with community outreach activities than on changing operational tactics (e.g. through crime prevention activities or increased patrolling in high-risk areas). The approach looks similar across country contexts, despite limited evidence of success (see paragraphs 4.11-4.17 on pages 26-28). Our interviews also suggested that there is little confidence among UK S&J experts that the demonstration of new policing approaches within model police stations is an effective means of promoting reform. Yet model police stations continue to be designed into new programmes, including the most recent design for Libya. DFID invests in internal affairs and professional standards units for police across many of its programmes, without much evidence that this contributes to improved police behaviour. Justice sector planning and coordination initiatives are another recurring activity, despite little history of success.

2.17 There are also gaps and omissions in the list of conventional activities that are difficult to explain. For example, despite DFID’s strong focus on criminal justice, with programmes in nine out of the ten countries we reviewed supporting criminal investigation by police, there is relatively little engagement across the portfolio with prosecutors, the judiciary, court administrations or the legal profession. Increasing police capacity to investigate crime without improving prosecutions and court processes is unlikely to improve the performance of the criminal justice system. While there may be good reasons for the omission, they are not explicit in programme design documents. Similarly, the balance is tipped strongly towards justice in rural areas, even though rapid urbanisation in many countries is generating pressing new S&J challenges. Certain justice issues, such as security of housing tenure, play only a minor part in the portfolio. Key stakeholders confirmed to us that these patterns of programming are a result of established preferences or ‘comfort zones’ among DFID and Stabilisation Unit staff and their regular consultant advisers.

2.18 Few of the programmes that we reviewed had explicit theories of change. Our own analysis of S&J programmes suggests a number of common assumptions underlying their design:

- building the capacity of central S&J institutions leads to improvements in S&J services and increased public trust and state legitimacy;

- training of police officers leads to improved police attitudes and behaviour;

- successful innovations introduced at pilot sites will result in national authorities replicating them at the national level;

- services to female victims of crime reduce the incidence of violence against women;

- improved community-police relations improve police responsiveness and reduce crime;

- better local dispute resolution processes reduce conflict within communities; and

- community awareness-raising and rights education encourage more women to access justice, leading to reduced violence against women.

2.19 We find it difficult to reconcile these assumptions with the pattern of results reported across the portfolio. In the community justice area, there is emerging evidence to support DFID’s theories of change, although there is still much to be learned about how to deliver and scale-up results in different contexts. Some of the work with central S&J institutions, however, seems to rest on assumptions that are implausible or contradicted by the evidence. For example, while victim support services for women can clearly help women in need, there is no evidence that they reduce the overall incidence of violence against women36 (see the Malawi case in Figure 7 on page 14). Empirical studies from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries show – and some of DFID’s central documents confirm37 – that entrenched police culture is not easily changed through training, particularly when externally initiated.38 If police are trained in new approaches and then returned to their former working conditions, colleagues and superiors, they quickly revert to old patterns of behaviour. There is also little evidence across the portfolio that behavioural changes introduced in model police stations are replicated elsewhere, due to political, financial and organisational constraints.

2.20 We are concerned that the assumptions behind conventional programming choices are being left untested and often unstated. A well-managed portfolio should, in our view, include an active process of testing the evidence behind different theories of change, both from DFID’s own experience and from wider empirical evidence. The resulting conclusions should be translated into strategic guidance for country programmes, helping to drive continuous improvement.

Contextual analysis and use of evidence are often poor

2.21 The older design documents that we reviewed cited no empirical evidence to back their chosen interventions. Since the introduction of DFID business cases, this has somewhat improved. There is still a tendency, however, to use evidence selectively – and sometimes incorrectly – to justify programming choices (see Figure 7 on page 14). There are no DFID standards as to what constitutes sufficient evidence and the quality assurance of business cases does not appear to address the evidentiary basis of programming choices. Some of the DFID advisers that we spoke to confirmed that business cases are approached more as internal marketing documents than as opportunities to ensure robust design. There is also a widespread perception that DFID lacks technical depth in this area.

2.22 The quality of contextual analysis underlying S&J programmes is variable. In our view, tailoring programmes to the context requires an understanding of three different domains and their interaction:

- the national political, economic and social environment;

- the structure, history and interests of the S&J institutions; and

- the S&J needs of the intended beneficiaries and how they are currently served.

2.23 Business cases usually include analysis of one or more of these domains, sometimes to a good standard. For example, the Nepal business case contains a strong analysis of S&J institutions and of the drivers of insecurity for women and girls, while the Ethiopia programme has produced quality research on the S&J needs of intended beneficiaries. We also saw a range of analytical work commissioned following design. It is rare, however, for business cases to include an analysis of all three domains or for the analysis to be kept up to date through the life of the programme.

2.24 Contextual analysis should be followed by a process of adapting interventions to the particular challenges and opportunities identified in each country context. This calls for a good understanding not just of what has worked in other contexts but also why it has worked, allowing for an informed judgement about its transferability. It is this analytical foundation for programme designs that we find to be weak, leading to some poor programming choices (see Figure 7 on page 14).

In Nigeria, the model policing component was based on assumptions about the willingness of the authorities to replicate successful initiatives across the country, despite a ten-year history of police reforms that had proved to be largely ineffective for want of political support.

A review of the Security, Justice and Defence Programme in Libya found that almost all of the assumptions in the original logframe – including on the overall direction of the political transition, the political environment, the availability of national budgetary resources and the status of the militia – proved to be incorrect.40

In Bangladesh, two studies41 pointed to the behaviour of lawyers as a major cause of delays in the judicial system. This was confirmed repeatedly in our beneficiary consultations. Even though the DFID programme had several components dealing with delays in criminal justice, it is not working with the bar association to address the lack of professional standards among lawyers.

In DRC, our review of the scale-up of DFID’s support to fragile states found a series of significant flaws in the design of the Security Sector Accountability and Police Programme.42 The designers failed to appreciate the extent of the differences between S&J institutions in DRC – with their French and Belgian civil law traditions – and those found in common law countries. There was little analysis of beneficiary needs, little consultation with the DRC Government and the political context was poorly understood.43 The programme was substantially re-designed midway through implementation, after which it began to perform better, delivering improvements in community-police relations in three pilot sites (see paragraph 4.14 on page 27).

In Malawi, the business case for Justice for Vulnerable Groups programme,44 which aims to achieve a 10% reduction in violence against women, notes that domestic violence will only be reduced through a comprehensive approach to tackling the factors that cause it, including changing social norms and behaviours, reducing exposure to abuse in childhood, reducing harmful alcohol use and increasing women’s economic empowerment. It also notes that mass media campaigns and community-based education have been successful in changing attitudes to violence among men. The programme, however, is almost entirely directed towards responding to victims of violence, rather than addressing underlying causes, does not engage with the media and works very little with men. We noted that DFID had commissioned a high-quality study on violence against girls in schools. This was not, however, picked up in the design of its programmes.

DFID advisers feel under pressure to over-promise on results

2.25 We are concerned at a tendency to over-promise on results. Several DFID advisers and consultants told us that they felt that it was necessary to overstate the results that could be achieved in each programme cycle, in order to secure approval. According to one DFID adviser at country level, ‘we have to put in ambitious targets to look like we get good value for money… We are expected to put in linear, year-on-year milestones and targets that cannot be met.’

2.26 This is sometimes related to UK Government pressure to spend more in strategically important contexts. We were told that the design team in Libya, for example, was repeatedly asked to increase its level of ambition and expenditure, to match the UK Government’s commitment to supporting the country’s transition. Through successive iterations, the planned programme was scaled up to £62.5 million, making it the UK’s largest ever S&J programme. Its comprehensive, top-down, capacity-building approach, however, had little prospect of success in such a difficult environment. In the end, the programme was significantly scaled back and realigned in the face of deteriorating security conditions. In other reviews, we have found a similar tendency towards over-commitment in fragile contexts, based on overoptimistic assumptions of the time required to scale-up interventions.45

2.27 In our view, the lessons from the case study countries clearly point to the conclusion that the most convincing designs are relatively modest in their objectives and focus on finding solutions to specific problems, rather than achieving across-the-board improvements in S&J institutions. The 15-year history of S&J assistance in Malawi is instructive. Over four generations of programming, the support has moved from capacity-building for specific institutions through an overambitious attempt to reform the criminal justice system as a whole, to arrive at a more focussed programme supporting the delivery of specific services for vulnerable people. The programme progressively moved away from major systemic reforms, in favour of niche interventions more tightly linked to specific problems, such as electoral violence and violence against women and children. This lesson on focus and selectivity, however, is yet to be articulated by DFID as a strategy for S&J programming or shared across the portfolio.

DFID has responded well to UK policy commitments on tackling violence against women and girls

2.28 The International Development Secretary, Rt. Hon. Justine Greening MP, has committed DFID publicly to tackling violence against women and girls around the world.46 It is one of the pillars of DFID’s New Strategic Vision for Women and Girls, which contains a commitment to helping 10 million women across 15 countries to access justice through the courts, police and legal assistance.47

2.29 We find that DFID has made good progress on developing strategies to support this commitment. Led by the Violence Against Women and Girls Team, which at the time of our review was based in CHASE, DFID has worked to map its existing programmes,48 assemble evidence on what works and develop guidance notes that identify programming options and possible entry points, including in particular sectors, with an overarching theory of change.49

2.30 One of the differences between this body of work and other DFID S&J guidance material is that it starts with a clearly defined problem – violence against women – and works back to possible solutions, giving it a more practical orientation. It also gives due attention to social norms and attitudes as barriers to change and a potential entry point for programming. In our view, DFID’s broader S&J portfolio would be strengthened by more detailed analysis of specific justice issues, such as land and housing tenure.

2.31 Across the portfolio, we saw a marked difference in the weight given in S&J programmes to the needs of women and girls since the Secretary of State’s commitments in this area. The programmes we reviewed in Bangladesh and Malawi had a strong focus on women and girls, including:

- providing medical, legal and social services for victims of violence;

- promoting women’s participation in and access to local justice mechanisms;

- recruiting female police;

- educating service providers on gender issues;

- raising women’s awareness of their legal rights; and

- working with women’s organisations to empower women.

2.32 There are important linkages between women’s vulnerability to violence and their broader legal status, which DFID is beginning to explore. During our field work, many of the women we met in poor communities described physical abuse, low status and discriminatory economic or social norms as closely connected problems. We saw evidence that approaching the problem of violence against women via economic empowerment, particularly around land rights, can be a productive strategy in some environments (see Figure 8 on page 31). In Bangladesh, DFID has begun to address other pressing justice issues for women, such as the labour rights of textile workers. It is also starting to explore the S&J challenges facing women in urban slums. We saw little attention, however, given to promoting attitude-change among men and boys, which our beneficiary consultations raised as a critical issue. There is also scope for the programmes to distinguish between different types of perpetrator (intimate partners, acquaintances and strangers) and target their interventions accordingly.

2.33 The DFID programmes we examined seem to have made relatively little effort to consult with women and girls or to include them in programme governance or monitoring arrangements. While DFID is certainly making women and girls a major focus of its programming, its approach would be stronger if it were more consultative and participatory. There is scope for DFID to be more creative in involving women and women’s organisations in the design, governance and monitoring of its S&J programmes.

The UK is yet to achieve a joined-up approach to shared international S&J challenges

2.34 Many of the stakeholders we interviewed pointed out the growing importance of international co-operation in the S&J arena on global threats such as terrorism, extremism, drug trafficking, money laundering and cyber-crime. These are ‘global public goods’, in that their impact is global and joint action across national boundaries is needed to address them. Effective international co-operation, in turn, often depends on building specific operational capacity in S&J institutions in other countries.

2.35 Global public goods in S&J are increasingly important to the UK Government. The National Security Council has signalled its desire for a more coherent UK approach in these areas. From 2015, CSSF funding will be accessible to a wider range of UK agencies to pursue these issues internationally.

2.36 DFID is obviously reluctant to allow other policy agendas to intrude on its S&J programming. We see this reluctance as legitimate; we would not like to see the poverty focus of DFID’s S&J portfolio become blurred with UK domestic interests.

2.37 Support for global public goods is, however, also a legitimate use of ODA. The NCA and the CPS make a persuasive case that problems such as organised crime and money laundering can be drivers of fragility and a brake on national development. There is likely to be an increased need in the future for focussed efforts to build capacity in developing countries to tackle specific global S&J threats.

2.38 In recent years, co-operation between DFID and other UK Government agencies in this arena has been growing. For example, DFID funds the Metropolitan Police to investigate money laundering linked to corruption in developing countries. There is also a range of co-operation at the country level. We note, however, that communication between DFID and UK S&J agencies is often poor. Other departments report that they find it difficult to engage with DFID without being treated as supplicants for funds. On the other hand, according to DFID, the interest of other departments in these issues is sporadic and influenced by the availability of budgets. The International Development Committee recently heard evidence that interdepartmental coherence is strong on some S&J issues, including on international campaigns against female genital mutilation, early child marriage and violence against women in conflict but weaker on drugs and arms trafficking, tax and anti-corruption. Overall, it concluded that the UK Government’s performance on policy coherence is ‘patchy’ and needs to improve.50

2.39 One of the rationales for creating the CSSF is to promote greater UK Government coherence in this area. Given the current quality of communication, we believe that effective CSSF programming will need to be anchored in a wider, cross-HMG strategy for using S&J assistance to tackle global threats.

3 Findings: Delivery

Delivery

Assessment: Amber-Red

3.1 This section examines common delivery challenges associated with UK S&J assistance. It looks at DFID’s supervision of implementing partners and at how the corporate results agenda and the procurement process influence programme delivery. Finally, it assesses how well different UK Government agencies work together in the delivery of S&J assistance. We note that many of the delivery challenges explored here are not specific to the S&J portfolio. We are concerned, however, that this portfolio seems to be particularly affected by weaknesses in DFID systems for procurement and delivery oversight.

DFID generally makes sound choices of delivery partner

3.2 DFID delivers its S&J assistance through implementing partners, including United Nations (UN) agencies, NGOs, private contractors and, to a lesser extent, partner governments. All of the available delivery channels offer advantages and limitations, which need to be assessed in each instance. Generally, we found a good balance of delivery channels across the portfolio, reflecting a realistic appraisal of the delivery capacity available in each country.

3.3 Working through the UN, with its global mandate, can help to secure access in politically sensitive areas. In Bangladesh, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) enjoys a closer relationship with national S&J institutions than the bilateral donors. On the other hand, the UN’s need to protect its access can make it reluctant to challenge national authorities on areas like corruption and accountability. In Bangladesh, we were concerned that UNDP had become too close to its counterparts, particularly the police, to challenge them effectively. UN agencies sometimes have goals that are at variance with DFID’s and are more resistant to direction. In Malawi, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) is funded by DFID to support services to women and children victims of crime. Given its mandate, UNICEF pays much more attention to children than to women, to the extent that one Malawi police counterpart reported feeling ‘locked out’ of DFID funding for women’s services. DFID, however, appears less able to take corrective action for a multilateral implementer.

3.4 Private contractors are generally preferred for large-scale programming. As discussed in paragraphs 3.22 to 3.28, large international companies are better equipped to manage DFID’s increasingly demanding contractual processes, particularly output-based contracting. They also have the resources to operate in insecure environments. As a result, the S&J portfolio is increasingly reliant on a small pool of large contractors.

3.5 In practice, as we found more generally in our review of DFID’s use of contractors,51 their performance varies widely. At their best, they can bring experience from around the world to bear on complex delivery challenges and harness the best of international and national expertise. The best implementation generally involves quality partnerships with local organisations that bring local knowledge and legitimacy. Few large companies, however, have standing capacity in S&J. They tend to recruit for each contract, resulting in inconsistent performance. Furthermore, we were informed that DFID terms of reference often set out precise requirements for members of delivery teams. According to implementers, these tend to favour technical expertise over management experience or knowledge of the country context. As a result, programmes often experience high turnover of personnel in the first year, as the contractors and DFID negotiate to get a suitable team in place.

3.6 We observed that national NGOs tend to have a clear advantage in the area of community justice. National NGOs in both Bangladesh and Malawi were able to offer thorough local knowledge, good working relationships with local stakeholders and an ability to mobilise communities without distorting incentives through payments and material benefits. In Bangladesh, the NGOs active in S&J were well networked with each other and willing to collaborate on delivery and joint advocacy. These advantages do not seem to be given sufficient weight in DFID’s procurement processes (see paragraph 3.27 on pages 21-22).

3.7 We were particularly impressed by an NGO grant-making fund run by the Manusher Jonno Foundation (MJF) in Bangladesh (£49.5 million over 5 years), which supports projects promoting human rights and good governance. It funds a number of partners active on justice issues, including violence against women, land rights and labour rights. MJF was established in 2002 as part of a DFID-funded CARE project, before becoming an independent organisation. It focusses on smaller and medium-sized NGOs able to operate in areas not covered by Bangladesh’s large NGOs.

3.8 We found MJF’s grant-making procedures to be very strong, comparing favourably with the contractor-managed programmes we examined in our 2013 review of DFID’s empowerment and accountability programming in Africa.52 The partner offers strong proposal assessment and due diligence, tailored capacity-building and robust monitoring arrangements. As a national NGO, it is cost-effective and well positioned to use its network to advance advocacy and policy dialogue on issues arising from its portfolio.

Supervision of programmes is inconsistent

3.9 Whatever the delivery channel, the level and quality of supervision by DFID are major factors in programme performance. Many stakeholders commented that DFID’s supervision of and level of engagement with its implementing partners is inconsistent. Given its importance and complexity, we are concerned that the S&J portfolio has not received the management focus that it needs. The problem may also reflect an overall lack of technical knowledge of the area.

3.10 While DFID governance advisers are required to have a broad knowledge of the S&J field, they offer different levels of practical experience. The level of oversight of programmes varies widely across different advisers and, therefore, often changes dramatically with staff turnover. We heard concerns that some DFID advisers were inclined to micromanage programmes while others were largely disengaged. Beyond mandatory contract-management processes, there appears to be no standard DFID approach to overseeing programmes, resulting in supervision that is often inadequate. The introduction of Senior Responsible Owners (SROs) under DFID’s new Smart Rules may help to address this – although there may still be a lack of continuity in SROs.53

3.11 In Sudan, for example, there were five heads of office and three governance advisers during the design and implementation of a four-year programme. According to a number of stakeholders, this contributed to the poor performance of the programme and a breakdown in relations between DFID and the contractor. In DRC, Nigeria and Sierra Leone, implementers also reported disruptive changes in direction or approach following turnover in DFID staff.

3.12 We also found inconsistent engagement in building and maintaining relationships with counterparts. It is widely acknowledged that the political nature of S&J assistance calls for close attention to relationship-building and political risk management. Yet the nature of the relationships between DFID, implementers and counterparts often remains unclear. This carries the risk that relationships between the contractor and the counterparts break down or that the implementer becomes too close to the counterparts in an attempt to secure their support. In Bangladesh, we were concerned that a UNDP-run police programme, embedded in police headquarters in Dhaka, seemed to treat the Bangladesh National Police as its intended beneficiary, rather than the public. It also appeared that DFID was slow to react to clear signals that the political environment had become less conducive to reform.

3.13 Overall, we found that implementing partners were rarely challenged on their performance. Weak results data and overoptimistic reporting are routinely accepted. We are concerned that DFID staff are not encouraged to be proactive in identifying and resolving delivery challenges. According to one former DFID staff member, ‘nobody applauds you for noticing that things are going wrong’.

3.14 A consequence of weak supervision is that programmes are being run as a collection of discrete projects, rather than as an integrated whole. In both Bangladesh and Malawi, we found that different components and their implementers had limited interaction with each other and were not managing their activities as parts of a larger whole. Leveraging influence across multiple interventions is important for achieving results. We also saw few examples of interaction between S&J programmes and DFID’s programmes on public financial management reform. In Sierra Leone, DFID is working with S&J agencies to increase the quality of their budget submissions. In DRC, the programme made some progress on attracting funding for the police from regional and commune authorities, which was positive. On the whole, however, DFID does not give much attention to the budgetary side of S&J institutions, including the difficult problem of ‘right-sizing’ them according to the resources available in national budgets.

3.15 We found a mixed record on coordination between centrally managed programmes and country-level programming. For example, a project with Harvard University on S&J indicators54 was initially not joined up with country programming in Sierra Leone or Nigeria, although this seems to have improved over time. The Security and Justice Innovation Fund is trialling innovative activities in a number of countries but is programmed without reference to the learning needs of country programmes. A new DFID protocol on co-ordination with centrally managed programmes may help to address this.55

Implementing partners are under pressure to deliver ‘reach’ over depth

3.16 DFID set itself the corporate target of providing 10 million women and girls with improved access to security and justice services by 2015. Most of the stakeholders that we spoke to agreed that, despite measurement problems (see Figure 9 on page 32), this target had been useful in signalling the UK Government’s commitment to addressing the S&J needs of women and girls.

3.17 Overall, however, we noted a preference for programmes that attempted to cover a wide geographical area and reach a larger population with standardised and relatively superficial interventions, rather than trying to achieve greater depth in a more focussed geographical area. While this is not necessarily a product of the departmental target, implementing partners reported feeling under pressure to meet over-ambitious spending and output targets, which can compromise the delivery of long-term and sustainable results.

3.18 In Malawi, a component on primary justice was providing training to village tribunal members on human rights awareness, legal issues and record keeping. We found this to be a project with considerable potential. Its scale and pace of delivery, however, meant that only a once-off, single day of training, or less, was offered to each tribunal to tackle matters of considerable complexity. Our consultations showed that there was considerable unmet demand for more in-depth training and that recall of topics covered in the training was limited. We were also surprised to find that the content of the programme was always the same, despite working across varied cultural environments (including in matrilineal and patrilineal areas).

3.19 In Bangladesh, a five-year Community Legal Service programme started two years behind schedule, as a result of delays in procurement. Both the contractor and its NGO delivery partners expressed their concern at the pace with which they then had to scale-up their activities. This risked the sustainability of results from what looked to be a potentially strong programme.

3.20 While there was consistent feedback from implementing partners on this point, DFID told us that it was not intentionally encouraging reach over depth. This suggests a problem of miscommunication. It may also be caused by DFID’s reliance on ‘reach’ indicators to assess value for money. Reach indicators measure the numbers of people who have gained access to a particular service, usually because they live within a defined distance of the service delivery point. This can create unhelpful incentives for the implementing partners to spread services thinly across a wide geographical area, running the risk of generating superficially impressive beneficiary numbers at the expense of more meaningful impact.

3.21 Where DFID’s objectives are to achieve social change, such as empowering women or reducing gender-based violence, a greater intensity of effort may be required to generate meaningful results. These are deep-seated and complex problems that require sustained engagement at multiple levels. In such cases, aiming for wide geographic coverage may not represent the best value for money over the longer term.

DFID’s procurement system is undermining effective delivery

3.22 We encountered widespread concern among DFID staff and contractors that the current procurement system frequently undermines effective delivery. Both UK Government staff and contractors noted a number of recurring problems with procurement.

3.23 First, for reasons explored above, the initial programme designs are often overambitious in scope and timeframe, causing the procurement to proceed on the basis of unrealistic terms of reference. While those bidding for the contracts are permitted to challenge the design, in practice their incentive is to promise to deliver all the results and more, at a discounted price, in order to secure the contract.

3.24 The procurement process is often subject to delays of 12 to 24 months. This carries the risk that programme designs become dated, country (and DFID) ownership declines and continuity with any predecessor programme is lost. During inception, contractors are often required to rebuild consensus on the need for the programme. In Sierra Leone, for example, procurement delays and poor DFID management of the transition from one phase of programming to the next meant that the contractor faced open resistance from counterparts on its arrival. A great deal of time and effort was required to rebuild relationships.

3.25 Procurement panels are not able to take account of evidence of past contractor performance when making their assessments. Technical assessments are, therefore, made purely on the basis of written bids. We encountered considerable scepticism among stakeholders as to whether this allowed for proper assessment of technical competence. Recently, DFID has begun to use output-based contracting in the S&J area. This involves payment against the delivery of specified outputs, rather than according to the level of inputs. We recognise the usefulness of output-based contracting in driving value for money, in the right context. We are concerned, however, that DFID is yet to develop criteria for identifying the programmes that are suitable. S&J programmes, which need to work flexibly in the face of a complex political environment, are not obvious candidates.

3.26 In output-based contracting, the main activities and outputs are agreed during contractual negotiations. This undermines the value of an inception phase and may result in unhelpful rigidity in programme delivery. In a policing project in Malawi, for example, neither DFID nor the contractor could say for certain what the procedure would be for changing the outputs in the project logframe.

3.27 Finally, we are concerned that the tendency towards higher-value programmes with more complex procurement process advantages a limited number of large international firms, at the expense of small firms, NGOs and local partners. DFID procedures increasingly require a knowledge of sophisticated value-for-money metrics and contracting modalities. Bidding for an output-based contract to deliver S&J assistance in a volatile context requires the skills and financial capacity to estimate and absorb complex commercial risks. These skills do not necessarily match up with those required to deliver effective S&J assistance. The procurement process does not give enough emphasis to local networks and country knowledge, which we have seen are key factors for effective delivery.

3.28 These problems are not unique to S&J assistance. The S&J portfolio, does, however, seem to be particularly vulnerable to disruption from procurement-related issues.

The UK Government has recognised the importance of human rights risks but needs clearer principles on risk management

3.29 S&J assistance in many developing countries involves engaging with institutions with a poor human rights record. Indeed, reducing abuse of human rights is sometimes the rationale for UK support. Inevitably, this raises the possibility that the assistance may do harm or bring the UK Government into disrepute, calling for careful risk management.

3.30 The UK Government has developed a tool – the Overseas Security and Justice Assistance (OSJA) tool – to assist with assessing human rights and reputational risks.56 It is mandatory for all UK agencies contemplating any form of support to S&J institutions abroad. It involves an assessment of the overall human rights situation in the country concerned; whether UK support in any way increases the risk of a human rights violation; and whether mitigating actions are available (for example, seeking assurances, training on human rights or additional monitoring and reporting). The guidance is procedural, rather than substantive, in that it sets out a decision-making process, rather than the principles to be followed. Serious risks that are open to mitigation must be approved by a head of department or overseas mission. If no mitigation is available, Ministers must be consulted. There is, however, no quality control of the underlying risk assessment.

3.31 We welcome the development of this tool, which clearly signals the UK Government’s commitment to taking human rights risk seriously. We note, however, that DFID still appears uncertain as to what types and level of risk are justifiable in which circumstances, resulting in inconsistent decision-making.

3.32 In Sudan, for example, there was a substantial problem with police brutality against street children in Khartoum. The DFID programme reportedly achieved some progress in training the police in new behaviours and strategies for engaging with street children. Nonetheless, DFID lacked confidence in the implementer’s ability to manage the human rights risks and requested that additional accountability and safeguarding mechanisms be introduced in this area. The programme ended up being terminated ahead of schedule, following violent suppression of protests in Khartoum and other cities in September 2013.

3.33 In November 2014, DFID suspended its Security Sector Accountability and Police Reform Project in DRC, following a finding by the UN that units of the Congolese National Police – although not those supported by DFID – had engaged in human rights violations, including extra-judicial killings.57 DFID received some criticism in the media for waiting for almost a year after the incidents to respond.58 According to DFID, it decided, in consultation with international partners, to delay a decision on suspension until the UN report was released, in order to give the DRC Government an opportunity to undertake a credible response. When no appropriate response was forthcoming, this was considered to be in violation of DFID’s Memorandum of Understanding with the DRC Government and the programme was suspended.

3.34 Both Sudan and DRC were examples of DFID trying explicitly through its programming to alleviate a known human rights problem. In such instances, DFID could be more forthright in defending its decision to engage with agencies with poor human rights records. It is more problematic when DFID helps to build capacity that might be misused, without a strong focus on safeguards and accountability. In Bangladesh, we were surprised to find that a UNDP-run DFID programme was helping to develop the intelligence functions of the Bangladesh National Police, including providing software and training to the Criminal Investigation Division on how to track mobile phones, analyse call data59 and monitor social media. There are obviously legitimate uses for intelligence capacity in fighting crime. Indeed, through this assistance, the police claimed to have disrupted criminal gangs engaged in human trafficking and prostitution. Our concern was that this assistance might also be misused. We were informed both by DFID and UNDP that politicisation of the Bangladeshi police had increased in recent times. We saw evidence that the prison population spiked during periods of opposition activism. In a deteriorating political context, the intelligence capacity built by UK assistance could be used to monitor and suppress political opposition groups.

3.35 DFID Bangladesh completed an OSJA risk assessment and opted to proceed. It informed us that it does not work with the parts of the police that are allegedly used for political purposes. The communications tracking software was provided to carefully chosen units and subject to security protocols that limit access. We were concerned, however, that both trained personnel and software could be redeployed for other purposes. Since we raised our concern, the project has stopped all support for criminal intelligence units in the Bangladeshi police.

3.36 Clearly, support for S&J institutions can raise some genuine ethical dilemmas and the risk of doing harm is real. While the OSJA tool is welcome, this is an area that calls not just for procedural guidance but also for clearer principles on when and how to engage with S&J institutions with poor human rights records. DFID should be willing to work with high-risk partners, provided it achieves an appropriate balance between the likelihood of success and the risks of doing harm and gives due attention to developing accountability mechanisms. An explicit set of principles would enable DFID to be more robust in defence of its support where the benefits outweigh the risks.

Cross-departmental delivery mechanisms are underdeveloped

3.37 Other UK departments and agencies are eager to play a larger role in the delivery of S&J assistance. They offer a number of potential advantages over contractors. Current UK Government staff bring up-to-date knowledge of contemporary issues and approaches. They are able to form good working relationships with government counterparts in developing countries. Judges, government lawyers, police and corrections officers all seem to share a preference for receiving technical advice from peers over contractors. In sensitive political contexts, UK Government representatives may also have better political access.

3.38 In practice, however, both DFID and the Stabilisation Unit have experienced significant challenges with using staff from other departments. They are not necessarily cheaper, especially in insecure environments where the Government’s ‘platform costs’ (package of required support) may be higher than a contractor’s. Other departments often struggle to provide continuity in personnel over a sustained engagement. They also lack knowledge of developing country contexts and approaches to programming.

3.39 In short, other government departments are not geared up to deliver sustained, complex development programmes. They could, however, provide useful strategic inputs into larger programmes run by DFID or the FCO.

3.40 The first phase of the Libya programme represented an interesting experiment in cross-UK Government delivery. While the main programme was being designed, the Stabilisation Unit was engaged in an operational role, co-ordinating the deployment of a cross-departmental team of advisers to support Libyan S&J institutions. With no formal programme design but a high-level of supervision from the UK Government agencies present in-country, this delivery arrangement proved adept at responding to the very fluid Libyan environment. It also carried the advantage that the advisers could speak with the authority of the UK Government. Ultimately, however, once the engagement was scaled up, a decision was made to procure a private contractor and the cross-government delivery arrangement was brought to an end.

3.41 Though the Stabilisation Unit’s experience in Libya was not without challenges, it raises the interesting possibility that other, more flexible direct delivery arrangements might be more appropriate in fluid stabilisation contexts. There is potential for mixed delivery arrangements that use contractors for large-scale activities while drawing on strategic advisory inputs from across the UK Government. With its emphasis on joint delivery in support of shared country plans, the CSSF may provide an opportunity to develop such joint delivery platforms, under the oversight of the National Security Council.

4 Findings: Impact

Impact

Assessment: Amber-Red