Information note: The use of UK aid to enhance mutual prosperity

Introduction

1.1 Overview

This annotated bibliography has been written to inform the information note by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) on the use of UK aid to enhance mutual prosperity. We focus on three key areas:

| Topic | Sub-questions |

| 1. Background on the use of aid for mutual prosperity | • Outline of ‘aid for trade’, economic development, and private sector development and financing initiatives • Brief history of tied aid and its relevance to mutual prosperity |

| 2. National interest debate in the UK | • Overview of the current debate in the UK about spending aid in the national interest • Overview of the UK development community’s response to the new strategic direction adopted in November 2015 |

| 3. Review of bilateral donor practices in enhancing mutual prosperity | • Explanation of changes to the rules governing official development assistance (ODA) • A rapid survey of other selected bilateral donor practices vis-à-vis the pursuit of mutual prosperity |

1.2 Approach

This annotated bibliography is based on a rapid survey of publicly available literature across each of the above topic areas, with a focus on contemporary sources (primarily literature published since 2010). The objective of this bibliography is to signpost a selection of sources under each of the above categories that summarise key aspects of the topic or debate. Most of the literature covered is therefore high-level and comparative as opposed to specific and case study-based. It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey or an in-depth literature review of all existing scholarship. We have included literature from a wide variety of sources:

- government/intergovernmental bodies

- think tanks and policy-oriented organisations

- academic peer-reviewed publications

- civil society organisations

- media.

1.3 Conceptualising mutual prosperity

We adopt a broad definition of the term ‘mutual prosperity’ in this annotated bibliography, which sits along a spectrum from the use of aid to support global economic development, which ultimately benefits donors and recipients, to the pursuit of short-term economic and commercial advantages for donor country firms. We also note that homologous terms are often used and have therefore been included: national interest, ‘win-win’, mutual benefit, enlightened self-interest, and secondary benefits, among others. In the UK context, the term ‘mutual prosperity’ is largely used in cross-government/whole-of-government documents, for instance the March 2018 National Security Capability Review (NSCR), whereas the concept of national interest is the primary subject of the 2015 aid strategy, titled UK aid: tackling global challenges in the national interest.

The following article sets the scene for how the pursuit of mutual benefits, including mutual prosperity, is conceptualised in donor countries.

-

When unintended effects become intended: implications of ‘mutual benefit’ discourses for development studies and evaluation practice, Niels Keijzer & Erik Lundsgaarde, Evaluation and Program Planning, June 2018, link.

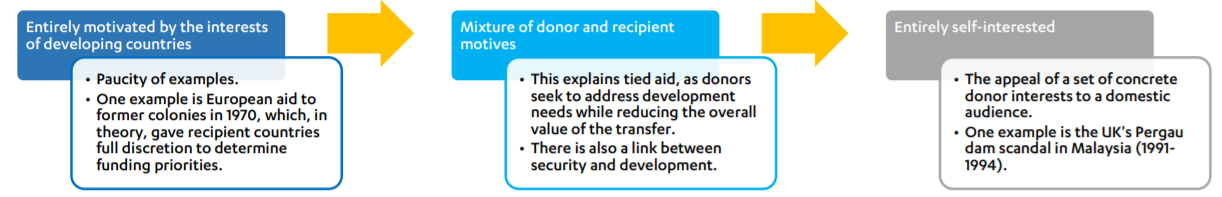

This article analyses the trend of moving away from an emphasis on developing country benefits towards the pursuit of mutual benefit as the main motivating factor for development cooperation. The authors start by acknowledging that development cooperation has always been driven by a multitude of motivations; indeed, the 1996 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) strategy entitled Shaping the 21st century: the contribution of development co-operation recognises that while reducing extreme poverty and human suffering is a moral imperative, donors also have a “strong self-interest in fostering increased prosperity in the developing countries”.2 More recently, both the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) also conceptualise development as a universal, shared mission that does not preclude mutual benefit. The differentiating factor of the current trend, however, is the tendency to “conceptualise a common development agenda for the donor and recipient country whilst denying the existence of trade-offs between their respective interests” (p. 210). This shift is motivated in part by efforts to appease or appeal to taxpayers in justifying ODA budgets, whether by focusing on international security and health threats, or on the benefits of economic returns. As illustrated in the figure below, donors exhibit a spectrum of motivations in relation to spending foreign aid.

Figure 1: Spectrum of donor motives

The authors also argue that research on aid effectiveness only evaluates developing country benefits, ignoring the “intended/unintended results” that stem from pursuing mutual benefit. Based on the official definition, ODA spent in pursuit of mutual benefit must have donor interest as a secondary concern. As a result, there is an incentive for donors to under-report on secondary benefits in order for their spend to count as 100% ODA. The authors end by reaffirming the need for “donors to be accountable to taxpayers about the full breadth of the development policy, not only the part that directly caters to developing country interests” (p. 216).

Background on the use of aid for mutual prosperity

2.1 Brief overview of ‘aid for trade’, economic development and private sector development initiatives

Trade and poverty reduction

-

Succeeding with trade reforms: The role of aid for trade, OECD, 2013, link.

The OECD’s Aid for Trade Initiative was launched at the 2005 Hong Kong World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial Conference. In this book, the OECD acknowledges that while trade can be an engine for growth and poverty reduction, the growth potential of trade is not always realised, and trade reforms have sometimes proved unsustainable. The OECD argues that effective aid for trade requires proper sequencing and policy coherence, achieved through donor coordination and alignment with country priorities. The book highlights several conclusions based on benchmark results from an econometric analysis and series of case studies:

- Both imports and exports contribute to economic growth, but they are subject to different constraints, therefore aid for trade and trade reform should focus both on export promotion and on the role of imports.

- Issues related to transportation constrain trade performance, especially infrastructure availability (more so than its quality).

- Access to credit is a significant barrier to trade, especially for imports.

- Complementary and compatible policies are important for trade expansion and economic growth; these include education, governance, business environment and macroeconomic stability, which affect investment and labour productivity and participation.

- Aid for trade should focus not only on helping developing countries capitalise on trade opportunities but also on tackling binding constraints that obstruct the impact of trade on growth. These constraints differ for landlocked countries, small and vulnerable economies, and commodity exporters.

In order to improve the quality of aid for trade, the OECD has adopted three pillars: 1) expanding monitoring of aid for trade flows, 2) learning from evaluations, and 3) identifying the most binding constraints to trade in partner countries.

-

The role of trade in ending poverty, World Bank and WTO, 2015, link.

According to the World Bank and the WTO, “the expansion of international trade has been essential to development and poverty reduction”, but it is not an end in itself (p. 7). The report delivers two substantive messages: 1) deepening economic integration and lowering trade costs is essential to ending poverty, as trade is a critical enabler of growth, and to opening up new opportunities for the poor, and 2) lowering tariff and non-tariff barriers between countries is essential, as is attention to the specific constraints facing the extreme poor. The theory of change put forward in the report is that a basic requirement for poverty reduction is economic growth, and therefore trade can drive poverty reduction by boosting growth. It does this in several ways: by increasing a country’s gross domestic product (GDP), as trade enables a more efficient use of resources through specialisation in the production of goods and services; by giving access to advanced technological inputs in the global market and enhancing incentives to innovate; by opening up new employment opportunities; and by providing better access to external markets for the goods that poor people produce.

The report also cautions, however, that growth alone may not be enough to end poverty and that the “extreme poor face numerous constraints that limit their capacity to benefit from wider economic gains” (p. 8). These constraints manifest across four characteristics: rural poverty, fragility and conflict, informality, and gender. Trade integration is vital and must be executed in such a way as to overcome these constraints, which are amplified by risks such as economic shifts, labour market adjustments, and vulnerability to weather events and climate change. Finally, the World Bank and the WTO propose recommendations in several policy areas:

- Reduce trade costs for deeper integration of markets – trade facilitation is critical.

- Improve the enabling environment through innovative policy frameworks that improve consultation with the poor and target their needs more carefully.

- Intensify the poverty impact of integration policies, with a greater focus on tackling the remoteness of markets.

- Manage and mitigate risks faced by the poor through building greater resilience.

-

The UK’s global contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals. Progress, gaps and recommendations, Bond, June 2019, link.

The Bond network’s latest report on the implementation of the SDGs contains recommendations on UK trade policy in relation to targets under Goal 17, in particular the following targets:

- Target 17.10: Promote a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system under the WTO, including through the conclusion of negotiations under its Doha Development Agenda.

- Target 17.12: Realise timely implementation of duty-free and quota-free market access on a lasting basis for all least developed countries (LDCs), consistent with WTO decisions, including by ensuring that preferential rules of origin applicable to imports from LDCs are transparent and simple, and contribute to facilitating market access.

To achieve these targets, Bond makes four key recommendations:

- Develop proper mechanisms for transparency in, and scrutiny of, trade negotiations and agreements. Ensure UK trade policy is coherent with its commitments under the SDGs, human rights, tackling climate change and ensuring there are no other negative impacts on the global south.

- Exclude Investor to State Dispute Settlement mechanisms from all future trade and investment agreements.

- Design a preferential market access scheme offering duty-free, quota-free market access to imports from economically vulnerable countries, including but not limited to LDCs. Make regional trade cooperation and integration the central aim of such a scheme.

- Use its position as an independent member to push for a fundamental rethink of the purpose and powers of the WTO.

-

Does foreign aid promote recipient exports to donor countries? Commercial interests versus instrumental philanthropy, Inmaculada Martínez-Zarzoso, Felicitas Nowak-Lehmann, M.D. Parra and Stephan Klasen, KYKLOS, Vol. 67, No. 4, November 2014, link.

This academic article reviews evidence on the effects of development aid on donor exports to developing countries. Overall, the study finds that bilateral aid provided by donors has positively affected their exports to developing countries, but this varies over time (the period of analysis is from 1998 to 2007) and across donors. Aid from Austria, Australia, Italy, Japan, Sweden, the US, Germany, Canada and Spain has been highly export-enhancing, whereas the export-enhancing effects for France, the UK, Norway, Denmark and Portugal have been positive but smaller. No effect was found for Belgium, Finland, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand or Switzerland. The differences across donors are largely explained by the level of tied aid and the sectoral allocation of aid. Across all donors, the authors find a smaller (and even insignificant) effect of bilateral aid increasing donor exports from 2000 onwards – potentially as a result of the OECD DAC recommendation on untying aid. In addition, the effect of an increase in the amount of donor exports flowing from aid is more moderate than previous studies found, corresponding to a roughly $0.50 increase in exports for every aid dollar in the short term, and $1.80 in the long term. Since the late 1990s, donors have increasingly signed regional trade agreements with developing countries as an alternative way to promote donor commercial interests.

-

Aid, Aid for trade, and bilateral trade: an empirical study, Jan Pettersson and Lars Johansson, The Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, Sept 2011, link.

In this academic article, the authors present the findings of an empirical study across 184 countries between 1990 and 2005 that examines the relationship between aid, aid for trade and bilateral trade. The study put forward several key findings. First, bilateral aid is not only positively correlated with donor exports, but also with recipient exports to donors. Second, an intensified aid relationship was associated with a reduction in the effective cost of distance, which implied larger bilateral trade. Plausible mechanisms for this include “preferences for donor commodities through aid in kind or through aid-financed recipient country students studying in donor countries” and “familiarization with the donor country”, which enhances export capabilities (p. 887). Third, a particularly strong relationship between aid in the form of technical assistance and exports in both directions was found, supporting the authors’ interpretation that market knowledge through interpersonal relations was a significant driving force for exports. Fourth, the “aid-trade link is particularly strong for donor exports to Sub-Saharan African countries and for recipient exports of strategic materials” (p. 866).

-

Institutions for trade: translating trade into development impact. Knowledge, evidence and learning for development, Phill Norley and Jessie Rosenthal, IMC Worldwide, 11 June 2019, link.

In the African Economic Outlook 2019 published by the African Development Bank, policymakers were urged to implement the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement to reduce both the time required to cross borders and the transaction costs tied to non-tariff measures. These measures, along with others, could yield a cumulative income gain of 3.5% of Africa’s GDP. This report, commissioned by the Department for International Development, focuses on two key questions:

- Which institutions in developing countries tend to be the most important/effective for translating trade into development impact across society?

The authors find that the “combination of economic opportunity, trade law commitment and government mindfulness of reputational standing will squeeze the space in which negative forces within political elites can in respect of self-interest act to maintain the status quo and complacency towards reform” (p. 2).

- Under what circumstances can donors contribute to reforming these institutions in order to achieve increased development impact from trade?

The authors identify that the following institutions have the potential to enhance the impact of growth in trade, with an identification of potential entry points: ministries of trade, economy and industry, joint public/private sector consultative committees (such as national trade facilitation committees), customs and border agencies, customs brokers, transport and logistics bodies, private sector industry representative bodies, and civil society organisations.

-

Our shared prosperous future, an agenda for values-led trade, inclusive growth and sustainable jobs for the Commonwealth, Dirk Willem te Velde, Maximiliano Mendez-Parra et al., APPG and ODI, April 2018, link.

Comprising 53 countries, the Commonwealth is committed to supporting sustainable economic development. However, shared prosperity remains a key challenge. This joint report by the UK All-Party Parliamentary Group for Trade Out of Poverty and ODI puts forward a case for the Commonwealth to adopt a values-led agenda on Trade and Investment for Inclusive Development, which focuses on harnessing the potential of trade and investment to help its developing country members, including the most vulnerable small economies, out of poverty.

The study proposes five priority areas that a new Commonwealth agenda should focus on:

- Reducing the costs and risks of trade and investment.

- Boosting trade in services through regulatory cooperation.

- Making trade more inclusive: women, young people and small and medium-sized enterprises.

- Addressing the special needs of small and vulnerable states.

- Strengthening partnerships: government, business, diaspora and civil society.

Economic and private sector development and financing

-

Blended finance in the poorest countries: the need for a better approach, Samantha Attridge and Lars Engen, ODI, April 2019, link.

This report outlines how blended finance uses public sector development finance to catalyse additional private investment in order to generate economic growth and create jobs, thereby reducing poverty. Mobilising private finance is at the centre of the ‘billions to trillions’ agenda, which seeks to address the financing gap of the SDGs. The authors examine the investment portfolios of the largest blended-finance actors, including multilateral development banks (MDBs), regional development banks and bilateral development finance institutions (DFIs), including the UK’s CDC group. Four key findings are presented:

- It is unrealistic to expect blended finance to bridge the SDG financing gap: mobilising billions rather than trillions is more plausible.

- A better understanding of the poverty and development impact of blended finance is needed. 3. In low-income countries, blended finance is hindered by poor investment climates, lack of investable opportunities, lack of tailored approaches, and the low risk appetites of MDBs and DFIs.

- Undue focus on blended finance risks moving ODA away from its core purpose of contributing to the eradication of poverty.

To conclude, the authors recommend that MDBs and DFIs make fundamental changes to their business models to enable them to take on riskier projects, that donors more generally think carefully about the trade-offs of investing ODA in blended finance, and that the OECD and MDB blended-finance frameworks be aligned, with disaggregated project-level data provided by all institutions.

-

Hitting the target: an agenda for aid in times of extreme inequality, Briefing paper, Oxfam, 8 April 2019, link.

In April 2019, Oxfam published ten principles or golden rules for donors on using aid to tackle inequality. The first is to “build on the example of the World Bank and establish two legally binding goals that ensure all aid that is given is clearly a. reducing inequality and b. reducing poverty” (p. 28). The report also highlights ‘do no harm’ risks associated with unproven public-private partnerships, and with “diverting aid to serve national political and commercial objectives” (p. 28). On the former, Oxfam notes the lack of evidence on whether aid to subsidise private investment tackles poverty or inequality, and some research shows that “putting a profit motive at the heart of development, particularly in sectors like health and education, increases the likelihood of unaffordable user fees, privatisation of public services” (p. 28). On the latter, Oxfam argues that donors must not put the national interest over the interests of the poorest people and should refrain from giving preference to their own companies when awarding ODA-funded contracts. Oxfam also makes the case for avoiding aid modalities and instruments that put countries at risk of debt. Donors are increasing their use of concessional loans (which now constitute 26% of all ODA spending), even in countries at risk of debt distress, and on barely concessional terms. The report concludes by reiterating that “reducing economic inequality makes growth more robust and sustainable, and also accelerates poverty reduction” (p. 28).

-

DFID, the private sector and the re-centring of an economic growth agenda in international development, Emma Mawdsley, Global Society, 2015, 29:3, link.

In this academic article, Mawdsley argues that the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) is re-centring a private sector-led economic growth agenda at the heart of its mandate, and increasingly turning to large-scale corporations, consultancies and the financial sector as delivery partners. The author acknowledges that a healthy private sector is essential to healthy development outcomes. However, without safeguards there are risks of enabling “yet more assertive strategies of capital accumulation and profit making that, in the name of ‘development’, overwhelmingly benefit wealthier actors in the UK and abroad” (p. 341). For instance, DFID is directly investing in infrastructure, as well as shaping the business, trade, investment and finance environment through new programmes supporting corporations, foreign direct investment, financial and legal services, and capital market promotion – all of which feature in the UK’s comparative advantage in management consultancies and the financial sector. While economic growth is undoubtedly necessary and desired by partner countries, and despite DFID’s focus on inclusive growth, the author argues that there is evidence that the strategies of DFID and other donors in this area are insufficiently anchored to development (as distinct from growth). More specifically, this growth agenda does not address numerous concerns including: inequality, decent work, private sector accountability, unequal distribution of risks and rewards in public-private partnerships, the short-termism and predatory nature of shareholder capitalism. In addition, conflicts of interest that are inherent and unavoidable in all development and certainly in private sector-led development, and the relationship between exposure and risk under conditions of greater financialisation (pp. 357-358).

Further reading:

- A Post-Brexit Customs Union and Global Development: The Best of All Worlds?, Hannah Timmis and Owen Barder, Center for Global Development, 17 April 2019, link.

- Strengthening Accountability in Aid for Trade, OECD, October 2011, link.

- Aid for Trade in Action, OECD, WTO, 2013, link.

- Trade, Inclusive Development, and the Global Order, Global Summitry, 13 April 2019, link. • Economic Development and the Effectiveness of Foreign Aid, a Historical Perspective, Sebastian Edwards, KYKLOS, Vol. 68, No. 3, August 2015,

- Less Pretension, More Ambition: Development Policy in Times of Globalization, Peter van Lieshout, Robert Went and Monique Kremer, Amsterdam University Press, The Hague, 2010, link.

- Does German development aid boost German exports and German employment? A sectoral level analysis, Inmaculada Martínez-Zarzoso, Felicitas Nowak-Lehmann, Stephan Klasen and Florian Johannsen, Journal of Economics and Statistics, 2016, 236:1, link.

- How does foreign aid impact Australian exports in the long-run? Sabit Amum Otor and Matthew Dornan, Development Policy Centre, Australian National University, September 2017, link.

- Aid, exports and employment in the UK, ODI, May 2019, link.

2.2 Overview of the history of untying aid

Origins of untying aid in the UK

-

When foreign aid and wider foreign policy goals clash: the Pergau Dam affair, Tim Lankester, 2018, Chapter 11 in Andreas Kruck, Kai Oppermann and Alexander Spencer (eds.), Political Mistakes and Policy Failures in International Relations, link.

Tim Lankester, former permanent secretary of the UK’s Overseas Development Administration (the agency responsible for the UK’s aid spending before DFID), provides first-hand analysis of what he describes as the “most controversial financing in the history of Britain’s foreign aid programme”: the Pergau dam (p. 241). In 1991, the Overseas Development Administration provided $234 million (around $600 million today) of aid money to fund a hydroelectric scheme on the Pergau river in Malaysia. In secret, the UK defence minister at the time had negotiated a major arms export deal in exchange for this aid, in which the Pergau project was an undisclosed term. Despite the Overseas Development Administration’s serious concerns about the economic viability of the dam, and the fact that the link to an arms deal was contrary to the UK’s aid policy and internationally agreed rules of aid and trade, Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd approved the grant. Investigations were subsequently undertaken by the National Audit Office, along with inquiries by two House of Commons committees. In March 1994, advocacy non-governmental organisation (NGO) the World Development Movement took the government to court, and the UK’s High Court ruled that the aid granted for Pergau was unlawful.

Projects under the 1977 Aid and Trade Provision (ATP) were not opened for international tender, and the Pergau dam fell into this category. As a direct response to the ensuing scandal, and the “potential for misuse of the aid budget on account of pressure from commercial interests” (p. 257), the newly elected Labour government abolished ATP in 1997 and later committed to untying aid. The International Development Act was also enshrined in law in 2002, placing poverty reduction at the heart of the UK aid programme. Lankester concludes by noting that the “renewed emphasis on aid as an instrument for promoting trade, alongside development and poverty reduction, clearly carries risks. The Pergau Dam Affair is a cautionary tale that deserves revisiting before the lessons from it are entirely forgotten for both aid and foreign policy more generally” (p. 258).

Further reading:

- ‘Success’ and ‘Failure’ in International Development: Assessing Evolving UK Objectives in Conditional Aid Policy Since the Cold War, Jonathan Fisher, Chapter 10 in A. Kruck et al. (eds.), Political Mistakes and Policy Failures in International Relations, link.

- Judicial review and the future of UK development assistance: On the Application of O v Secretary of State for International Development (2014), John Harrington and Ambreena Manji, Legal Studies (2018), 38, pp. 320-335, link.

OECD recommendation on tied aid

-

Untying aid: is it working? Thematic study on the developmental effectiveness of untied aid: evaluation of the implementation of the Paris Declaration and of the 2001 DAC recommendation on untying ODA to the LDCs. An evaluation of the implementation of the Paris Declaration, Edward J. Clay, Matthew Geddes and Luisa Natali, ODI, December 2009, link.

This report is the first independent evaluation of DAC member policies and practices on untying aid, further to the adoption of the recommendation on untying ODA by the OECD DAC on 25 April 2001 and the 2005 Paris Declaration. The evaluation concludes that the DAC recommendation has had a positive impact on the untying of aid, as evidenced by the fact that untied bilateral aid rose from 46% between 1999 and 2001 to 76% in 2007, and, for LDCs, it increased from 57% to 86% (p. viii). However, grey areas persisted due to the exclusion of free-standing technical cooperation and food aid from the recommendation. The report highlights six reasons for de facto tying: 1) donor regulations, 2) lack of local capacity, 3) local and regional contractors unable to compete internationally, 4) unequal access to information, 5) potential risk aversion at donor HQ, and 6) pressure for speedy implementation.

In terms of conclusions, the report confirms the economic theory that untied aid is likely to be more cost-effective than tied aid. A survey of developmental impacts in six country case studies (Burkina Faso, Ghana, Lao PDR, South Africa, Vietnam and Zambia) revealed cautiously positive findings, with evidence of direct employment, income stream generation and promotion of local business development. Stakeholders in these partner countries noted that untying aid is about country ownership and the practicalities of contracts, modalities, use of country systems, and giving an opportunity for local business to compete. They are “less concerned about removing biases between donor partners in their trade, except where excessive inefficiencies of tying significantly reduce the resource transfer value of aid” (p. viii). The report concludes by recommending that DAC members increase the transparency of their reporting on tying to the OECD, and that their plans include specific measures for increasing the use of country systems, bolstered by initiatives to strengthen local and regional capacity to compete for aid-funded projects.

-

2018 Report on the DAC untying recommendation, OECD, 13 June 2018, link.

This report provides an update on the tying status of ODA across DAC donors, taking into consideration both de facto and de jure tied aid. The OECD argues that untying “generally increases aid effectiveness by reducing transaction costs and improving recipient countries ownership” (p. 3). In 2016, 88% of donors (including the UK) reported as untied all, or almost all, of their ODA referenced by the 2001 recommendation, an increase of 5.7% from 2015. Progress, however, is mixed. Adherence to the transparency provisions of the 2001 recommendation, which requires ex ante notification of awards and reporting on ex post contracts, is improving in the latter but still weak in the former. The analysis finds that 99% of aid that should be but is not untied as per the recommendation is related to project-type interventions, primarily in the following sectors: health (22%), government and civil society (22%), agriculture, forestry and fishing (11%) and education, which includes scholarships and student costs in the donor country (10%). While the overall direction of travel is positive, some donors have further to go to fully untie their aid, including Austria, the European Union, Greece, Korea, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and the United States.

Drivers and impact of tied aid

-

Political power and aid-tying practices in the development assistance committee countries, Jared Pincin, King’s College, 1 August 2013, link.

This paper recognises that the allocation of aid is influenced by political realities in donor countries, and that politicians in these countries face a degree of pressure from domestic interest groups when determining the volumes and distribution of aid. Given these pressures, political leaders often use aid strategically to improve their own political position. To assess this phenomenon in a comparative way, this paper investigates the relationship between the fragmentation of executive power and the degree of competition in government legislatures on the amount of tied aid. Fragmentation is measured by the number of cabinet ministers and number of political parties in the governing coalition, and legislative competition is broadly defined as the relative strength of the government in relation to the legislature (the number of seats above a simple majority). Using data from 22 OECD DAC countries between 1979 and 2000, the paper illustrates that tied aid “increases as the number of decision makers within the government increases and decreases as the proportion of excess seats a governing coalition holds above a simple majority increases” (p. 372). One political reform that could reduce tied aid is the setting of clear and public benchmarks that must be met before aid is tied, thereby placing the burden of proof for tying aid on interest groups and legislators to publicly justify the practice.

-

Development, untied: Unleashing the catalytic power of Official Development Assistance through renewed action on untying, European Network on Debt and Development (Eurodad), Polly Meeks, September 2018, link.

In 2016, roughly $25 billion of ODA was reported as formally tied (equating to more than the total bilateral ODA spent on health, population and water combined). In addition, in 2016 donors awarded 51% of contracts to their own domestic companies (in the UK, the US and Australia this is 90%), with only 7% going to suppliers in LDCs and heavily indebted poor countries. Suppliers in the global south also tend to lose out on contracts in the most lucrative sectors, including technical assistance. The perpetuation of tied aid is partly facilitated by the fact that the OECD DAC rules governing tying are exclusive of key countries and sectors. Eurodad estimates that the cost of tied aid in 2016 was between $1.95 and $5.43 billion, which does not factor in missed opportunities to catalyse local-level development in the long term. In light of these statistics, this report argues that the tying of ODA procurement, which requires that goods and services be obtained from suppliers in donor countries, “puts the commercial priorities of firms based in rich countries before development impact” (p. 3). Eurodad recommends that donors prioritise budget support over project-based ODA and use local procurement systems (provided that local people agree this is the best option). In addition, donors should seek to overhaul their procurement systems to give firms in the global south a fair chance to compete, for instance by splitting tenders into smaller lots, advertising in local languages through local media, and enhancing procurement skills and capacity in local donor entities.

Further reading:

- DAC Recommendation on Untying Official Development Assistance, OECD Legal Instruments, OECD/LEGAL/5015, link.

- OECD Revised DAC Recommendation on Untying ODA, OECD, 24 January 2019, link.

- In whose benefit? The case for untying aid, ActionAid, April 1998, link.

- Is tied aid bad for recipient countries? Sang-Kee Kim, Young-Han Kim, Economic Modelling 53 (2016) pp. 289-301, link.

The national interest debate in the UK

3.1 Overview of the UK development community’s response to the ‘aid in the national interest’ approach

Measuring aid in the national interest

-

Public opinion matters, so what does the public think? Aid Attitudes Tracker, Will Tucker, 27 April 2018, link; and Reasons for giving aid: a government policy in search of a public? Jennifer van Heerde-Hudson, David Hudson and Paolo Morini, 30 January 2018, link.

The Aid Attitudes Tracker (AAT) has been studying the attitudes of the UK population since 2013. Recent data has shown that support for aid spending to stay the same or increase has risen from 43% to 46%, while support for aid to be cut has decreased from 53% to 47%. In another AAT online survey which looks into whether UK aid should focus on helping people in poor countries most in need, deliver equally on mutual interest or promote UK business and strategic interests, the results are as follows:

- 10% of the public choose a response where giving aid should be tipped in favour of UK national interests

- 24% are in support of giving aid based equally on UK interests and others’ needs

- 34% prefer to give UK aid primarily to help people in poor countries who need it the most • 15% think aid should not be given at all

- 15% ‘don’t know’.

While it is clear that a third of the UK public supports the use of aid to focus mostly on poverty reduction, one of the greatest perceived threats to aid quality is that the goal of poverty reduction is diluted when pursuing national interest goals. Another key finding from the survey is that aid should be given primarily to reduce poverty, and not to benefit the UK, but “if it happens to benefit us then that is great”. At the same time, the AAT also finds that 45% of respondents indicate that aid is ineffective, with only 12% regarding it as very effective. These percentage levels remained fairly stable between November 2013 and September 2017. The AAT states that it is essential for the international development sector to keep an eye on the degree to which the pursuit of national interest gains in prominence, and increase efforts to improve public perceptions of and support for aid.

-

Commitment to Development Index 2018, United Kingdom Country Report, Center for Global Development, link.

In 2003, the Center for Global Development (CGD) launched the Commitment to Development Index (CDI), which ranks the world’s 27 richest countries according to their performance across seven policy areas: aid, finance, technology, the environment, trade, security and migration. The breadth of areas covered is in recognition of the fact that development is about more than foreign aid alone, and because “decisions made by the richest countries about their own policies and behaviour have repercussions for people in lower-income nations” (p. 2, 2018 brief). In the most recent ranking (from 2018), the UK scored eighth, with relative strengths in trade, security, aid and the environment, and performing less well on finance, migration and technology. The UK dropped one place from the 2017 CDI ranking, largely due to a lower score on aid. Table 1 summarises the three components most relevant to the mutual prosperity agenda.

-

Real Aid Index, ONE Campaign, link.

ONE Campaign’s Real Aid Index, launched in February 2019, assesses the performance of individual government departments against the criteria set out in the Real Aid Charter, which focuses on maintaining the 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) target, focusing entirely on poverty eradication, effectiveness and transparency. ONE raised concerns about the poverty focus of specific government departments, rating the performance of the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy as moderate and that of the Foreign Office (FCO) and the Home Office as weak. DFID, which still spends the majority of UK ODA, and the Department for Health and Social Care were both rated as strong in this area.

-

Principled Aid Index, Policy Briefing, Nilima Gulrajani and Rachael Calleja, ODI, March 2019, link.

ODI’s Principled Aid Index, launched in March 2019, presents a comparative picture of the extent to which OECD DAC donors are spending aid in a principled way, defined as aid that targets “countries that need it most, supports global cooperation and adopts a public spirited focus on development impact rather than a short-sighted domestic return”. It defines unprincipled aid in the national interest as “self-regarding, short-termist and unilateralist” (p. 2). The UK is ranked as the second most principled donor, just behind Luxembourg and followed by Sweden. The Index also shows that the UK has become less public-spirited in its aid spending over the period from 2013 to 2017, along with other donors including Sweden, Norway and Korea, measured across four dimensions: minimising tied aid, reducing alignment between aid spending and United Nations voting, de-linking aid spending from arms exports, and localising aid.

Table 1: Three key components of the mutual prosperity agenda

| Component | Indicators | UK progress |

|---|---|---|

| Aid | • Aid quantity (bilateral and multilateral) • Aid quality | • UK bilateral aid quality scores above average, based on its performance in reducing the burden on recipient countries, and transparency and learning. • Significant room for improvement on bilateral aid quality on indicators measuring how donors foster recipient country institutions(building institutional strength by using country systems, priorities and approaches). |

| Finance | • Investment • Financial secrecy | • UK international investment agreements are slightly better than average, taking account of public policy goals of partners and supporting their environmental and social regulations, but there is room for improvement. • Scores well on international commitments and its compliance with the OECD anti-bribery convention. • The UK could strengthen its performance as an open and transparent investor by a more comprehensive commitment to the OECD guidelines on multinational companies. • Low score on financial secrecy, which could be improved if overseas territories and crown dependencies moved in line with the rest of the UK |

| Trade | • Lower income-weighted tariffs • Agricultural subsidies • Services trade restrictions • Logistics performance | • Good trade infrastructure and efficient customs procedures. • Very few restrictions on trade in services and – due to being part of the EU Customs Union – has low tariffs. |

Visions for delivering on aid in the national interest

-

After Brexit: new opportunities for global good in the national interest, Michael Anderson, Matt Juden and Andrew Rogerson, CGD, August 2016, link.

Shortly after the EU referendum, the CGD published a paper assessing new UK policy opportunities for global development that arise from Brexit. The authors take the view that the “national interest agenda is not just about aid; indeed, it is mostly not about aid at all. It touches on diplomacy, trade, security, movement of people, and financial regulation, as well as much else. Such an agenda will require a formidable combination of soft and hard power” (p. 6). The authors focus on the “triple win” of policies that are good for the world, good for the UK, and also good for the UK’s negotiation to leave the EU. They find four clear winners:

- Better trade for development – counteracting the risk that developing countries come last in future trade negotiations.

- Fighting modern slavery and people trafficking – building on the UK Modern Slavery Act.

- Climate change leadership – new freedom to partner for carbon pricing.

- Making new migration controls work for mutual benefit – putting in place a unified ‘points-based’ system for migration control spanning EU and non-EU countries.

The authors also identify ‘runner-up’ policy areas: 1) restructuring UK agricultural subsidies, 2) establishing a new UK Development Bank, 3) developing a UK-owned “Smart Sanctions” mechanism, and 4) more cost-effective humanitarian assistance. Finally, the paper outlines promising areas that merit further consideration. These are: a stronger voice for the UK in environmental regulation, new intellectual property arrangements, a new model for competition law, a new procurement system, voluntary contracting into European delivery channels (such as the European Development Fund), new global initiatives on tax evasion, and boosting UK research networks in international development.

-

Five ways to deliver UK aid in the national economic interest, Paddy Carter, ODI, September 2016, link.

In this briefing note, ODI proposes five ways of spending UK aid in the national interest without compromising on its essential purpose of eradicating poverty and promoting sustainable development summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Five ways to deliver UK aid in the national interest (ODI)

| Overview | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Enlightened self-interest: The UK’s 2002 International Development Act requires that aid be spent with the primary purpose of contributing to a reduction in poverty. | When the UK spots cost-effective opportunities to help the world’s most vulnerable, even if there is no obvious benefit to the UK itself, it should take them. The UK should look for opportunities to promote development overseas which also bring benefits at home, but self-interest must not become a necessary condition for all UK aid spending. |

| Boosting trade: Following the EU referendum, there has been rising interest in exploring ways to use UK aid to leverage better trade deals for the UK. | The UK should keep the focus of export promotion on addressing market failures in international trade, rather than indirectly using aid to finance export sales. |

| New markets for investment: The UK has for a long time invested in supporting the enabling environment for private sector growth in developing countries, by helping them put in place building blocks. DFID also uses its development capital to ‘crowd in’ private investors into projects and new enterprises. But not all investments have the same impact on poverty. | Aid can benefit UK investors by driving inclusive and sustainable growth overseas and by addressing market failures in capital markets. But the secretary of state must ensure that support from the aid budget is proportional to poverty impact. |

| Disaster prevention: While aid spending is set by the 0.7% target, investing money to reduce future humanitarian obligations will not save the UK money in the sense of reducing total aid spending, but it will free up the aid budget for spending on areas of more direct benefit to the UK. It is in the national interest to spend less money coping with disasters that could have been prevented. | The UK should take the lead in creating insurance-based financing structures, complemented by strong country systems, that disburse funds rapidly to organisations with well-defined roles. |

| Lead on global public goods: Exemplary public goods are global security, the natural environment and pandemic prevention. | The UK should continue to use aid to bring stability to fragile states, and build on initiatives like the Ross Fund, the Global Innovation Fund and Innovation UK to develop new transformative technologies to share with the world. |

-

Britain’s Global Future: Harnessing the soft power capital of UK institutions, Philip Bond, James Noyes and Duncan Sim, ResPublica, July 2017, link.

This report takes into account the consequences and implications of the UK leaving the EU in terms of foreign policy. The authors argue that UK soft power – the influence a country exerts on the world stage without relying on economic or military strength – is more relevant and important than ever. The Global Britain soft power approach should be closely integrated with the government’s approach to diplomacy and foreign policy in order to increase the UK’s authority on the world stage. The report also emphasises that civil society is better placed than the state to establish long-term relationships with other countries, and that these institutions must be at the heart of the government’s vision for Global Britain. The report also offers several recommendations, including creating a clear soft power vision based around the primacy of civil society and reallocating foreign aid spending in line with the UK’s institutional strengths. The report also argues that a “smarter” international aid policy is needed, where more spending is allocated to education and government and civil society.

-

Global Britain: A twenty-first century vision, Bob Seely MP and James Rogers, Henry Jackson Society, February 2019, link.

This report, authored by Bob Seely, MP for the Isle of Wight and member of the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee, and James Rogers, Director of the Global Britain Programme at the Henry Jackson Society, presents a vision for how the UK can make the institutions and instruments of state power more effective, particularly in a post-Brexit context. The authors argue that the UK currently lacks an integrated approach to foreign policy, and that it should create a National Strategy Council (emerging from the existing National Security Council), which leads on developing a National Global Strategy. The authors also recommend an organisational re-structuring, which would see DFID and the Department for International Trade amalgamated into the FCO as new agencies, following the model of Australia and Canada. Several changes to spending are also outlined, as follows:

- The BBC World Service should be mandated by the FCO as a global broadcaster on all major audio and visual platforms and should be funded from the “international development” budget (defined as distinct from the foreign aid, or ODA, budget).

- All UK contributions to peacekeeping should come from the ODA budget.

- Humanitarian aid spending should be preserved, while allowing for more spending to be channelled through the FCO and Ministry of Defence (MoD).

- The total amount of spending on “international development” – inclusive of ODA – should be capped at 0.7%, provided the UK gains freedom to define this aid as it sees fit.

- The 0.7% of GNI target should no longer be mandatory, but dependent on the quality of projects. Unallocated funding should be put into a UK Development Fund for future use.

- The UK should no longer provide ODA to countries with advanced military or space programmes without a clear strategic purpose.

The report concludes by noting that there is an “imbalance in overseas spending”, and that by changing the definition of what counts under the umbrella of international development, there would be an uplift in spending for the FCO and the MoD (with the latter receiving an increase of as much as 3% of GDP).

-

Global Britain, global challenges. How to make aid more effective, Jonathan Dupont, Policy Exchange, 2017, link.

This report was published a year after the UK’s 2016 EU membership referendum. Against the backdrop of Brexit, the author addresses the question of how to make UK aid more effective in tackling global challenges and makes the case that there are clear synergies between national and global interests, particularly in the combination of hard and soft power, innovation and trade. Nevertheless, the UK must be careful that “its decision to become a ‘global champion for free trade’ should be seen as an expression of long standing principles, and not just a mercantilist attempt to secure a greater export share” (p. 14). Finally, the author puts forward four principles to follow in tackling global challenges:

- Maintain the commitment to a Global Britain, including by continuing to spend 0.7% of GNI on aid and updating the 2015 UK aid strategy to take into account post-Brexit changes.

- Create a more efficient and innovative aid budget, including by creating a new Office for Aid Effectiveness and by increasing the proportion of ODA spent on global public goods.

- Stand up for democracy, rule of law and a free press, with DFID publishing an annual analysis of the quality of developing country institutions.

- Reduce trade barriers with the developing world and act as a global champion of free trade, by going beyond the EU’s duty-free, quota-free approach for developing countries and by reforming the Common Agricultural Policy after 2020.

-

The changing face of UK aid: How to deliver mutual prosperity, Jack Thompson, PA Consulting, 2 July 2019, link.

In this blog post, the author notes that ODA spending is a key area scrutinised in government spending reviews, given the shift in direction for UK aid to align with the UK national interest, as outlined in the 2015 UK aid strategy. The Prosperity Fund is presented as an example in which, although innovative in the approach to fund-level portfolio management, tension existed between strategic objectives and delivery. The Fund has not yet worked out a design that “reduces poverty and promotes inclusion while delivering secondary benefits to UK and international business” (paragraph 3). In light of this, four key lessons are presented in relation to designing, defining, measuring and operationalising aid portfolios in order to deliver greater returns from UK aid:

This report, authored by Bob Seely, MP for the Isle of Wight and member of the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee, and James Rogers, Director of the Global Britain Programme at the Henry Jackson Society, presents a vision for how the UK can make the institutions and instruments of state power more effective, particularly in a post-Brexit context. The authors argue that the UK currently lacks an integrated approach to foreign policy, and that it should create a National Strategy Council (emerging from the existing National Security Council), which leads on developing a National Global Strategy. The authors also recommend an organisational re-structuring, which would see DFID and the Department for International Trade amalgamated into the FCO as new agencies, following the model of Australia and Canada. Several changes to spending are also outlined, as follows:

- Design programmes that balance primary purpose and secondary benefit, starting with the primary development challenge to solve before considering where the UK can support.

- Define secondary benefits and how to achieve them.

- Develop monitoring and evaluation procedures, including the identification and prioritisation of relevant indicators.

- Decide who is responsible for delivering benefits.

-

Ethical foundations for aid: duty of rescue and mutual benefit, Paul Collier, ABC Religion and Ethics, 1 September 2016, link.

In a long-form online essay, Paul Collier argues that there is “nothing inherently bad about designing aid in such a way that it generates mutual benefit. On the contrary, it can be desirable.” This is because mutual benefit can create a more equal relationship that differs from the “faux ‘partnership’ of charity”, make donor commitments more credible, and even lead to larger aid budgets. Spending aid for mutual benefit does, however, carry the risk of an adverse effect: diverting aid from projects which contribute to the “duty of rescue” (part of the ethical rationale for foreign aid spending) to those that make a smaller contribution but generate benefits for the donor. This risk is mitigated by the fact that while each dollar of aid spent for mutual benefit is less effective for the duty of rescue, donors are still incentivised to provide more aid. Nevertheless, Collier argues that any project characterised by mutual benefit must be scrutinised to ensure that it is effective as the best alternative use of money. He demonstrates this scrutiny by looking at four distinct uses of aid:

- Chinese infrastructure-for-resource deals, which removed conditionality and avoided the asymmetry of the donor-recipient relationship. However, this asymmetry was replaced by differing degrees of capability. Chinese packages were also opaque and not subject to competition, skewing terms in China’s favour.

- Subsidies for commercial investment, given that the poorest countries are short of investment by modern firms. Mass poverty cannot be overcome by donor financing of governments, therefore confining aid to the public sector restricts its potential. In contrast, aid to subsidise pioneer firms is an ethically reasonable way of compensating these firms for benefits that accrue to others (positive externalities).

- Aid to fragile states¸ for which there is a legitimate duty of rescue. Aid used to address fragility (a global public bad) has the potential to be a global public good, yet it has become ethically controversial given the potential for security expenditure to be repressive. As security is a precondition for development, it is difficult to justify excluding spending that strengthens national military capability from aid spending.

- Aid for the mitigation of climate change, specifically reducing carbon emissions. Climate change is a global priority, however it should be financed through new instruments such as carbon taxes rather than a diversion of aid budgets from their primary duty of rescue from mass despair. Some projects will meet the dual criteria of duty of rescue and climate change mitigation, but the most pertinent use of aid is for climate adaptation.

In conclusion, Collier notes that the ethical foundations of aid can be usefully reinforced by the addition of a self-interest component. However, due to the potential for moral hazard, any claims to mutual benefit must be adequately scrutinised.

Concerns about the pivot towards national interest, in the UK and elsewhere

-

UK aid: allocation of resources, seventh report of session 2016-17, House of Commons, International Development Committee, 21 March 2017, link.

In 2017, the International Development Committee (IDC) launched an inquiry into the allocation of UK aid. In the final inquiry report, the IDC notes a shift in UK development strategy since the 2016 EU referendum, including a change in tone on the relationship between the aid budget and trade. The IDC also notes the concern expressed by witnesses to the inquiry that UK aid could become “implicitly tied”. While this would not be a formal condition, the shift to focus more on the national interest could provide expectations of producing goods or services from the UK. While the IDC welcomes DFID’s strong focus on economic development as an important aspect of poverty reduction, the creation of mutually beneficial partnerships in the national interest must not lead to a rise in explicitly or implicitly tied aid. As part of this, “language surrounding leveraging aid for trade and creating opportunities for UK companies and the City of London needs to be used cautiously, so as not to create an impression that aid is being given conditionally” (p. 37). The IDC concludes the report by strongly reiterating its recommendation that poverty reduction be made the explicit primary purpose of any UK aid spending.

-

Exporting stimulus and “shared prosperity”: Reinventing foreign aid for a retroliberal era, Emma Mawdsley, Warwick E. Murray, John Overton, Regina Scheyvens, Glenn Banks, ODI, Development Policy Review, 2017, link.

Despite the recessions in northern economies following the 2008 global financial crisis, levels of foreign aid spending have not fallen. The central argument of this article is that there has, however, been a shift in the narrative and nature of foreign aid spending, constituting a “return to explicit self-interest designed to bolster private sector trade and investment” (p. 25). The authors term this shift retroliberalism, due to its revitalisation of (explicit) state-led financing under the umbrella of neoliberalism. Based on evidence from the UK and New Zealand, the authors argue that aid programmes are increasingly functioning as exported stimulus packages. In practice, this means that “aid has become part of a broader stimulus package intended to revive and sustain capitalism, primarily with the donors in mind, but with spillover benefits for capitalist elites in partner countries” (p. 40). The benefits for workers and citizens are less sure. The article concludes by proposing that aid should be reclaimed, with a focus on lessening global inequality.

-

National interests and the paradox of foreign aid under austerity: Conservative governments and the domestic politics of international development since 2010, Emma Mawdsley, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 183, No. 3, September 2017, link.

In this academic article, Mawdsley argues that although Conservative-led governments since 2010 have imposed domestic austerity while maintaining foreign aid commitments, they have adopted an increasingly explicit stance that aid must be spent in the national interest. In 2014, the UK met the UN target of spending 0.7% of GNI on ODA, despite high levels of hostility from Conservative MPs, influential sections of the media, and parts of the British public. This commitment runs counter to arguments that foreign aid is an external projection of national approaches to redistribution, with higher levels of aid correlating with states that commit to higher levels of spending on domestic social welfare. Providing a historical overview, the author notes that since the establishment of the OECD DAC in 1960, levels of ODA spending under Conservative governments have always fallen. The Conservative 2009 Green Paper on One World Conservatism represented a departure from this trajectory, promising to adopt a value for money-led approach while maintaining levels of spend, a promise which was fulfilled when the Conservative-led government came to power in 2010.

Since then, there has been a notable shift in the official aid discourse of most OECD DAC donors. DFID has been a leading example of a more assertive and explicit focus on spending aid to further national self-interest. Conservative champions of aid have sought to justify aid spending while imposing austerity by referencing various UK interests as follows: soft power as an explicit benefit of foreign aid, contributions to global public goods (such as climate change mitigation and disease control) as enlightened self-interest, economic benefits to the UK as achievable alongside poverty reduction, and improving the UK’s security as a contribution to global stability. The article concludes with the reflection that successive Conservative governments have sought to persuade the British public that foreign aid spending should be maintained by appealing to their moral and charitable instincts; whether the shift towards persuading them on the grounds of aid working in the UK national interest has been successful is yet to be seen.

-

“Aid in the national interest” – in the interest of the poorest? Mike Green, The Reality of Aid 2018: The Changing Faces of Development Aid and Cooperation, Reality of Aid Report, 14 January 2019, link.

In this report, Mike Green from Bond argues that since the 2016 EU referendum, the Brexit discourse on ‘taking back control’ has permeated the development sector in the UK and is mirrored in the national interest debate. In this chapter, the author focuses on the decline of DFID’s share of UK ODA, the establishment of the cross-government Prosperity Fund (with a secondary objective of creating opportunity for international business, including UK companies), the creation of the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), and a push to change the definition of ODA. He argues: “Dual objectives of national interest alongside poverty reduction can create an inherent tension, which results in secondary national interests eclipsing ODA’s primary aim of reducing poverty. Taking this to its furthest conclusion, an increasing emphasis on the promotion of UK interests can distract from the rightful emphasis of ODA on poverty reduction. It also has potential to be a worrying step toward the return of tied aid” (p. 403).

Further reading:

- The “global Britain” report: rule-breaking in foreign aid will not strengthen UK soft power, Global Development Institute, 12 February 2019, link.

- Development aid and national interests, February 2019, British Council, link.

- Development, self-interest, and the countries left behind, Brookings Institution, Sarah Bermeo, 7 February 2018, link.

- DFID’s share of UK aid rises but it’s not all good news, Devex, 5 April 2019, link.

- UK aid figures spark renewed alarm over cross-government spending, Devex, 6 April 2019, link.

- Opinion: Aid isn’t going to the world’s poorest people. Why?, Devex, 25 April 2019, link.

Review of bilateral donor practices in enhancing mutual prosperity

4.1 Changing definitions of official development assistance

-

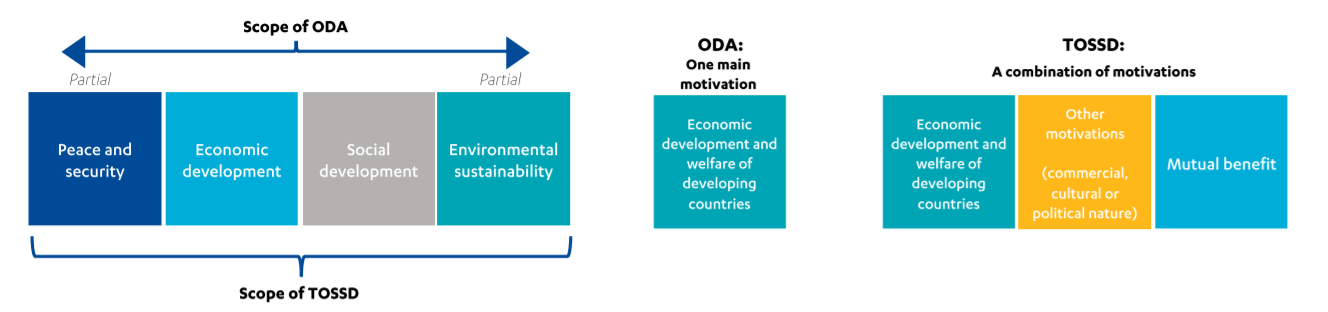

TOSSD Compendium for public consultation, draft June 2016, OECD, link.

In a 2016 report, the OECD highlighted that the concept of mutual benefit “is one of the main principles of South-South co-operation… The concept is linked to solidarity and equality among countries and implies that international co-operation arrangements have win-win outcomes benefitting all partners involved” (p. 15). Likewise, many OECD members acknowledge that their development cooperation is also linked to their foreign policy and trade objectives. In recognition of this, the OECD has introduced the concept of total official support for sustainable development (TOSSD), which “aims to cover a broader range of activities that support sustainable development in developing countries, not necessarily with development as their primary objective. This means it will be better aligned with the principle of mutual benefit” (p. 15). The figure below illustrates the differing scope of ODA and TOSSD.

Figure 2: the differing scope of ODA and TOSSD

-

ODA modernisation background paper, Development Initiatives, September 2017, link.

This report demystifies the concept of ODA modernisation, a term used to refer to ongoing aid reforms being undertaken by the OECD DAC, first announced in 2012. Through this process, the official system for how ODA spending is monitored, measured and reported is being significantly updated. There are both technical and political drivers behind these changes. The technical aspects include ensuring consistency of reporting across donors and more accurate reflections of donor effort allocated to development activities. The political and policy drivers are more complex and vary across donors. The DAC itself states that modernisation seeks to reflect the introduction of many new types of finance since the definition of ODA was conceived in the 1960s, and to politically incentivise donors to increase more concessional financing flows. The changes will also better accommodate the ways in which emerging economies deliver development assistance, including through south-south cooperation. ODA modernisation can be conceptualised across two areas of change, see Table 3.

Development Initiatives concludes that while the new rules may improve ways of measuring donor effort, they also mean that overall ODA figures will not fully resemble actual resource transfers. This is largely because the headline ODA figures for loans and private sector instruments (PSIs) will not match funds committed or disbursed. There is concern that PSIs represent a significant change to the concessionality aspect of ODA, and that it will be difficult to maintain the same level of transparency as for the rest of ODA reporting, due to commercially confidential information.

-

How should UK development finance count as aid?, 18 October 2018, Ian Mitchell and Euan Ritchie, CGD, link; and Aid for the private sector: continued controversy on ODA rules, Jesse Griffiths, ODI, 17 October 2018, link.

Table 3: ODA modernisation across two areas of change

| 1. Updating, clarifying and ‘streamlining’ existing ODA reporting | 2. Expanding ODA to bring in new activities, new flows and new financing instruments not previously eligible as ODA |

|---|---|

| • ODA loans: only the grant proportion of loans will count as ODA, in other words a loan of $10 million with a 25% grant element will count as $2.5 million of ODA. Repayments of capital on existing loans will no longer be subtracted from the headline ODA figures. Currently the discount rate is set at 10%, but in future it will be differentiated by country income status. • Debt relief: new rules allow donors to count a greater proportion of their lending as ODA than would otherwise be the case, specifically because of the risk of default when lending to developing countries, especially the poorest ones. | • Private sector instruments (PSIs), including equity investments, guarantees and other ‘market-like’ instruments, will allow for reporting of investments in private companies, non-concessional loans to private companies, and underwriting of commercial activities through guarantees. The ODA eligibility of PSIs is to be judged according to different criteria: financial additionality and development additionality. |

| • In-donor refugee costs: levels have risen significantly across donors, along with a tightening of the rules on how to report these costs | • Some peace and security activities: new ODA-eligible activities, mainly non-coercive security-related activities with a long-term sustainable development objective, for instance training for partner military forces and educational activities to prevent violent extremism. The proportion of core funding provided for UN peacekeeping that counts as ODA is to be increased from 7% to 15%. |

| • Data changes – including purpose codes, channel codes and finance types: addition of sector codes, and a plan to align purpose codes with the SDGs. New financial codes for instruments such as blended finance. |

In these two blog posts, the CGD and ODI both express concern over the UK’s proposal to change the definition of aid to allow returns made on investments by the CDC Group to count towards the 0.7% aid spending target. As noted above, the OECD DAC agreed in 2016 to introduce a new category of ODA spending knowing as ‘private sector instruments’, or PSIs, to capture the value of official support to private sector companies acting in developing countries, both domestic and foreign. The CGD argues that CDC profit should not count as ODA, nor should the UK let the aid ceiling limit its investment ambition. Using the UK’s preferred reporting mechanism, counting profits would double-count investment in CDC, thereby creating artificial incentives to favour its use. Should the UK succeed in changing the rules, this would mean that the UK would provide less support overall to developing countries. ODI argues that focusing on what counts as ‘official’ support only serves to obscure other, larger issues, for instance how we can avoid incentivising aid to flow to the most viable commercial opportunities rather than following the greatest needs. Can we prevent an increase in tied aid and debt risks? If no agreement is reached, the concept of ODA itself risks being undermined.

4.2 Rapid survey of other bilateral donor approaches to mutual prosperity

-

When unintended effects become intended: implications of ‘mutual benefit’ discourses for development studies and evaluation practice, Niels Keijzer & Erik Lundsgaarde, Evaluation and Program Planning, June 2018, link.

The article (summarised in Table 4) presents a present-day comparison of four donors, including the UK, based on policy statements and the legal basis for development initiatives.

Table 4: Recent policy statements on development assistance/cooperation

| United Kingdom | Netherlands | European Union | Denmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| “The UK’s development spending will meet our moral obligation to the world’s poorest and also support our national interest” (2015 UK aid strategy). | “Our mission is to combine aid and trade activities to our mutual benefit” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2013). | “Development policy will become more flexible and aligned with our strategic priorities” (European Commission, 2016). | “We will be driven by the wish to promote Danish foreign and domestic policy interests at one and the same time” (Danish government, 2016). |

| Legal basis for development assistance/cooperation | |||

| “Assistance provided for the purpose of (a) furthering sustainable development in one or more countries outside the United Kingdom, or (b) improving the welfare of the population of one or more such countries” (International Development Act, 2002). | No law on development cooperation. | “Union development cooperation policy shall have as its primary objective the reduction and, in the long term, the eradication of poverty” (Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, 2012). | Both international goals and Danish interests featured in the International Development Cooperation Act. |

The following section constitutes short summaries of how a sample of other OECD DAC donors are currently utilising their aid budgets to pursue mutual prosperity.

European Union

-

The modernization of European development cooperation: leaving no one behind? Alexandra Rosen, CONCORD Europe, 2018 Reality of Aid report, 14 January 2019, link.

ODA provided by the EU and its 28 member states (EU28) totalled €75.46 billion in 2016, but declined by 2.4% in 2017. Nevertheless, the EU28 constitute the world’s largest development donor bloc. However, an estimated one-fifth of ODA provided by EU member states constitutes “inflated aid”, which is financial flows that do not represent a genuine transfer of resources to developing countries, as opposed to “genuine aid”. There is also a shift away from providing ODA to LDCs.

Some EU member states have committed to spending aid on delivering genuine developmental impact in developing countries, particularly Sweden and Luxembourg. But there is concern that EU aid is not always used for development purposes in developing countries. In-donor refugee costs accounted for 30% of the increase in EU ODA in 2016, and are a central feature of European development cooperation. Overall, there has been a “trend towards an instrumentalisation of ODA to address emerging non-development objectives”, for instance managing migration flows and achieving domestic security goals (p. 343). In addition, the EU relies heavily on the private sector to achieve the SDGs, but evaluations have shown that EU blending projects do not generally have strong pro-poor dimensions. While the private sector has an important role to play, rigorous safeguards are required to ensure that inequalities are not exacerbated.

United States

- The challenges and opportunities of US foreign assistance under Trump, Tariq Ahmad, Marc Cohen, Nathan Coplin, Aria Grabowski, Oxfam America, 2018 Reality of Aid report, 14 January 2019, link.

- United States profile, Donor Tracker, 2019, link.

- USAID Budget and spending FY 2020, USAID, link.

The US is the largest donor country in dollar terms, but ODA accounts for only 0.17% of its GNI. In 2016, untied aid occupied 65% of the US’ total bilateral ODA across all sectors and countries. Nonetheless, it is the world’s largest bilateral donor and the largest provider to LDCs. The US prioritises countries where it has strategic interests. The greatest beneficiaries are Israel, Egypt, Jordan, Afghanistan, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Development assistance has been, and continues to be, strongly linked to US national security and economic growth. In April 2017, President Trump issued an executive order that requires government agencies to ‘buy American and hire American’.

The Trump administration has also renewed the US’ focus on supporting the private sector in development. Private sector growth is at the centre of the Millennium Challenge Corporation’s mission. Congress introduced legislation in February 2018 to revamp and expand the US’ development finance institution, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC). The Better Utilisation of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act would replace OPIC with the US International Development Finance Corporation, at double the capitalisation rates, which would continue to give preference to US firms. The initial text of the bill would have seen a dramatic reduction in the robustness of a 33-year-old prohibition of investments in countries whose governments fail to uphold labour rights.

The ‘America First’ rhetoric has thus far not entirely subverted the poverty reduction focus of US aid, and Congress has thus far resisted President Trump’s attempts to dramatically cut foreign assistance.

Sweden

- Policy framework for Swedish development cooperation and humanitarian assistance, Government Communication 2016/17:60, Government Offices of Sweden, 12 May 2017, link.

- Sweden profile, Donor Tracker, 2019, link.

Sweden has exceeded the 0.7% ODA-to-GNI target each year since 1975, and it has committed to spend 1% of its GNI on ODA since 2008 (1.04% in 2018). It is the largest donor in proportion to the size of its economy, and the sixth-largest donor country, with net ODA at $5.8 billion in 2018. 68% of Sweden’s bilateral ODA was allocated to low-income countries (when excluding unallocated funding) in 2015-17.

The Swedish government does not have an explicit approach to using aid for mutual prosperity. In 2014, the Swedish government announced a new policy framework for development cooperation. The framework is characterised by two overarching perspectives: the perspective of poor people on development and a rights-based perspective (p. 3). The former perspective means taking a comprehensive approach to the situation, needs, conditions and priorities of a person living in poverty, with poor women, girls, men and boys as the key focus. This also includes the four fundamental principles of human rights: non-discrimination, participation, openness and transparency, and responsibility and accountability. The Swedish government focuses on three thematic areas: conflict, gender, and the environment and climate change. The Swedish government is committed to the principle of the country partner ownership and that its development cooperation “must be adapted to conditions and needs and where Swedish development cooperation has an added value – for countries, regions or organisations”. The policy framework recognises that “cooperation with business actors in partner countries and internationally is essential to development” as it “helps to mobilise both private sector capacity for initiatives, creativity, experience and expertise and its financial resources for sustainable development. Business has a central role to play in economic development and is essential for job creation” (pp. 53-54).

Japan

- Emphasizing SDGs but increased instrumentalization under the new development cooperation charter, Akio Takayanagi, Japan NGO Center for International Cooperation (JANIC), 2018 Reality of Aid report, 14 January 2019, link.

- Development cooperation charter, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Japan, 10 February 2015, link.

- Japan profile, Donor Tracker, 2019, link.

Japan is the fourth-largest donor country in absolute terms, spending $14.2 billion in 2018. This accounts for 0.28% of Japan’s GNI. Loans are the major modality, with only 27.2% of Japan’s ODA provided in the form of grant aid. Most of Japan’s ODA is provided bilaterally (82% in 2017).