International Climate Finance: UK aid for halting deforestation and preventing irreversible biodiversity loss

Score summary

The UK has a range of relevant and credible programmes tackling drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss around the world, but lacks evidence of impact at scale.

Global rates of deforestation and biodiversity loss are catastrophic. Between 1990 and 2020, the world lost 178 million hectares of forests. Natural ecosystems have declined by nearly half in extent and condition since 1970. The UK spent £1.2 billion in aid on protecting forests and biodiversity between 2015 and 2020, through the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

Most of the UK programmes are well targeted towards prevailing drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss. However, the lack of a clearly prioritised strategy has contributed to a portfolio that is too widely spread, both geographically and thematically. The quality of evidence and contextual analysis is mixed, with strong engagement on illegal logging and the global timber trade counterbalanced by programming on alternative livelihoods that is less well founded. Some programmes are working well with forest communities, including indigenous peoples, but consultation with communities during programme design is inconsistent and more could be done to strengthen the participation of women in local forest governance.

The UK has been an active supporter of global commitments and initiatives, and has positively influenced various multilateral funding bodies and programmes. The three departments are coherent at the policy level but in country often lack shared strategies, coordination arrangements and learning mechanisms. There is a need for a more considered approach to working with the private sector.

Given the major challenges in measuring results from efforts to protect forests and biodiversity, there is limited evidence of impact across the portfolio and the UK has not done enough to fill the measurement gap. Nonetheless, most programmes are delivering well at output level and there are some examples of excellent programming. The Forest Governance, Markets and Climate programme (supported by earlier Department for International Development investments in the forest sector) has been highly effective in influencing tropical timber markets in both producer and consumer countries. In our three case study countries (Colombia, Ghana and Indonesia), UK aid has made positive contributions to knowledge, institutions, governance and policies, although the overall impact on deforestation rates cannot be assessed. The portfolio includes some innovative pilots, but successful results are not always scaled up or replicated, and there is underinvestment in evaluation and learning across the portfolio.

Individual question scores:

- Relevance: How well are UK aid programmes related to halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss responding to global, national and community needs and priorities? GREEN/ AMBER

- Coherence: How internally and externally coherent are UK aid programmes directed at halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss? GREEN/ AMBER

- Effectiveness: To what extent has UK aid contributed to halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss? GREEN/ AMBER

Executive summary

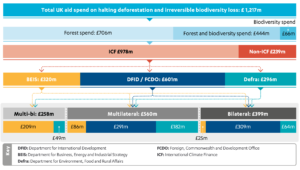

By our calculations, the UK spent £1.2 billion in aid between 2015 and 2020 on protecting forests and biodiversity, through bilateral and multilateral channels. The support has been delivered by several departments – the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Department for International Development, now merged into the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) – and supported by various cross-government coordination mechanisms, including a newly established Nature Board.

This review assesses the relevance, coherence and effectiveness of this support. Our methodology included a literature review (published separately), case studies of UK programming in Colombia, Indonesia and Ghana, programme desk reviews and consultations with affected communities in Colombia and Indonesia.

Relevance: How well are UK aid programmes related to halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss responding to global, national and community needs and priorities?

Over the review period, the UK has invested in a broad range of intervention types and delivery models. Activities were directed towards tackling prevailing drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss, at national and international levels. For example, UK aid programmes have sought to reduce the impact of cocoa production on forests in Ghana, strengthen land-use planning and security of tenure in Indonesia, and promote sustainable ranching to reduce illegal forest clearing in Colombia. The portfolio also tackled global challenges through efforts to influence forest-risk commodity markets and promote green financing models. In addition, it has included a range of initiatives at community level, such as community forestry, sustainable smallholder agriculture and community-based enterprises.

However, we find that the UK lacks a clear overall strategy to guide its efforts on deforestation and biodiversity loss. There are elements of such a strategy in documents like the International Climate Fund Strategy (2011), the 25 Year Environment Plan (2018), the Green Finance Strategy (2019) and outputs from the London Conferences on the Illegal Wildlife Trade and related declarations (2014 and 2018). We were also told that a new International Climate Finance strategy (which ICAI has previously noted was required) is being prepared and have seen unfinished working papers. However, these documents do not add up to a clear or consistent set of priority objectives or plan for achieving them. There is also a lack of country strategies for the key countries. This has resulted in a collection of programmes spread widely over geographies, issues, commodities and approaches that, while generally making useful individual contributions, lack the combined impact that might have resulted from a clearer strategic focus. We will return to this issue in our follow-up review next year.

Some of the programmes we reviewed are well grounded in evidence on ‘what works’ and in-depth analysis of the context. For example, the UK’s long-standing work on illegal logging and the timber trade is based on a detailed understanding of the challenge. The Forestry, Land-use and Governance programme in Indonesia has made good use of political economy analysis, while the Forest Governance, Markets and Climate (FGMC) programme in Ghana demonstrates a strong understanding of national and local forest governance contexts. However, interventions on palm oil in Indonesia, cattle ranching in Colombia and cocoa in Ghana are not based on a similar depth of understanding. Some projects lack clear and testable theories of change about how they will contribute to protecting forests and biodiversity, and some make unsubstantiated assumptions about their eventual impact. We also found examples of intervention types that are not supported by evidence. For example, the literature suggests that developing alternative livelihood options for communities living in forest areas is unlikely to reduce deforestation. However, there are several such livelihoods interventions across the portfolio.

We assessed how well programmes reflect the needs and priorities of the communities they affect. Many of the programmes are focused on influencing government policies, markets or global challenges and therefore have limited engagement with communities. For those that do provide direct support to communities, we found good-quality engagement with citizens during the implementation process. In both Indonesia and the Congo Basin, UK programmes have helped to build the capacity of community-based organisations and indigenous peoples to assert their rights. However, consultation with affected communities and sub-groups at design stage is not consistent. Furthermore, given that measures to tackle deforestation and biodiversity loss can disrupt local livelihoods, there is a lack of systematic engagement with local communities to monitor unintended consequences. Many of the community-focused programmes include gender analysis and women-focused programming. However, in our citizen engagement, we heard widespread concerns that women, young people and poorer people are excluded from forest governance arrangements, and UK programme documents acknowledge a need to work more with national governments to overcome barriers to their participation.

We have awarded the UK portfolio a green-amber rating for its clear focus on the drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss, while noting that it would benefit from a more strategic, evidence-based and consultative approach.

Coherence: How internally and externally coherent are UK aid programmes directed at halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss?

UK efforts to galvanise international action on the drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss have been effective when structured as a sustained and properly resourced campaign. The UK has played a significant role at a global level in supporting coordinated action, helping to secure a number of global commitments. The UK government has also engaged strongly with multilateral institutions across the portfolio, and has helped improve their systems, capacities and programming.

Within the UK government, policy coherence at central level is good and there is a clear division of labour between BEIS, FCDO and Defra. However, while there are strong examples of ‘joined-up’ working across government within the portfolio, we also found examples of avoidable duplication and fragmentation, most notably around cross-cutting issues such as private sector engagement and sustainable financing. Coordination of programming is held back by a lack of shared strategies, management arrangements and learning mechanisms.

The UK recognises the importance of engaging with the private sector, given the role of global markets in driving deforestation and biodiversity loss. Work in the timber industry under the FGMC programme takes a sophisticated approach, engaging with multiple stakeholders across producer and consumer countries, and building in clear economic incentives for producers. Work in other forest-risk commodities is not as well developed. Across the portfolio, the quality of private sector engagement is variable. The UK has helped reinforce voluntary moves in the private sector towards greener investment and more sustainable supply chains, but the much larger problem of continuing private investment that threatens forests and biodiversity remains unresolved. Given the scale of the challenge, a more concerted effort to bring about change in the private sector is needed.

While we find that coherence and coordination are not yet strong enough across government, the positive engagement by the UK at global level merits a green-amber score for coherence.

Effectiveness: To what extent has UK aid contributed to halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss?

Measuring results in the protection of forests and biodiversity presents difficult technical and practical challenges. The UK has an indicator for tracking ‘avoided deforestation’ across its climate finance, but only a handful of programmes have been able to report against it, due to capacity and methodological constraints. There are no internationally agreed measures of biodiversity loss, and only one biodiversity-related programme in the UK portfolio has come up with a methodology for assessing biodiversity quality. Some key projects in the portfolio are not well set up for results management, owing to weaknesses in theories of change and results framework. While these challenges are common across development partners working in the sector, this is clearly an area where the UK could be doing better.

As a result, there is insufficient evidence to reach conclusions on the overall effectiveness of the portfolio. In Indonesia, one of our case study countries, deforestation rates have been falling, but there has been no country-level analysis of the UK’s contribution, despite sustained investment over a number of years.

However, we found a good range of effective interventions across the portfolio, with most programmes delivering well at output level and some examples of exemplary programming. In particular, the £280 million FGMC programme, building on earlier phases of UK forest sector programmes, has been able to influence and shape demand for timber in major consumer markets (such as Europe and China), while supporting in-country reforms in producer countries. Across the portfolio, the UK’s support for national civil society organisations in timber-producing countries has helped increase the voice of marginalised forest communities, including indigenous peoples, and promote biodiversity protection initiatives that also benefit local communities.

In our case study countries, UK aid has made important contributions to strengthening knowledge, institutions, governance and policies. For example, the UK has supported successful interventions to reduce illegal logging and improve regulation of the timber market, while strengthening the rights of indigenous peoples to manage forest land. In Colombia, UK aid has helped to improve forest monitoring and law enforcement, and in Ghana it has built capacity for improved forest governance.

The UK has also piloted a wide range of potentially useful interventions and has been willing to take risks in testing new approaches and initiatives. However, there is no defined approach to scaling up or replicating successful pilots. Furthermore, the emphasis on piloting interventions has not been matched by sufficient investment in evidence collection to support uptake. Overall, there is underinvestment in evaluation and learning at programme, thematic, country and portfolio levels.

We have awarded a green-amber score for effectiveness, in recognition of some high-quality programming in very challenging areas, while noting the need for greater effort on results measurement and learning.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1:

UK bilateral ODA support to tackle deforestation and biodiversity loss should have a tighter strategic focus, concentrating resources to increase impact.

Recommendation 2:

All programmes addressing deforestation and biodiversity loss should be monitored and evaluated against common, measurable indicators designed specifically for assessing deforestation and biodiversity impacts.

Recommendation 3:

Independent external evaluations of the bilateral programme should be carried out regularly at programme, country and global levels and then used to shape strategic funding decisions.

Recommendation 4:

UK bilateral programmes should be guided by social impact analysis and should include safeguarding measures, to maximise the benefits for and minimise negative impacts on local communities, women and vulnerable groups.

Recommendation 5:

Gender issues need greater prioritisation in policies and programming to ensure that women benefit from investments in forests and biodiversity.

Introduction

The world’s tropical forests and biodiversity are declining at an alarming rate.2 Many irreplaceable ecosystems have already been lost, and others are close to a tipping point – including globally significant areas such as the Amazon. Biodiversity is under threat from overharvesting, climate change, pollution and many other factors, with up to a million animal and plant species at risk of extinction in the coming decades. The decline of forests and biodiversity poses threats both to the global economy and to the many people in developing countries who depend on nature for their livelihoods.

There have been clear commitments on halting deforestation and preventing irreversible biodiversity loss within global agreements on climate change. So far, however, just 3% of international climate finance has gone towards protecting forests and other ecosystems.

The UK has been an active participant in international initiatives to protect forests and biodiversity. Following the 2014 New York Declaration on Forests, it entered a joint commitment with Germany and Norway to increase support for REDD+7 to at least $5 billion in the period from 2015 to 2020. Within the UK’s pledge to provide £11.6 billion in climate finance in the five years to 2025, the prime minister has announced that at least £3 billion will go towards solutions “that protect and restore nature and biodiversity”. In 2021, the UK and Italy plan to co-host the next UN Climate Change Conference (COP26), delayed from 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This review assesses how effective the UK aid programme has been in halting deforestation and preventing irreversible biodiversity loss. It covers both UK aid programmes, through bilateral and multilateral channels, and related diplomatic efforts to galvanise international action. It looks at the period from 2015 to 2020, during which, by our own calculation, the UK spent £1.2 billion on programmes related to deforestation and biodiversity. For most of the period, the programmes were managed by the former Department for International Development (DFID), the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). The portfolio was restructured in 2020 following the creation of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and most aid expenditure is now under the authority of the foreign secretary.

The review explores whether the UK’s approach to tackling deforestation and biodiversity loss is relevant, given evidence on ‘what works’. It also considers whether the portfolio is managed in a coherent way, and how effective the programmes have been at identifying and scaling up viable solutions. Our review questions are set out in Table 1. In light of the UK’s commitment to intensifying its efforts on nature and biodiversity, our objective is to identify lessons that can help to strengthen the approach.

Box 1: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. Most important for the UK’s goal of ending deforestation and biodiversity loss is the following SDG:

SDG 15 Life on Land reflects the importance of forests and biodiverse regions to the planet, and to sustainable development. Forests are a key economic resource, providing food, medicine and fuel for more than a billion people.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and question | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance: How well are UK aid programmes related to halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss responding to global, national and community needs and priorities? | • To what extent are UK aid programmes related to halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss structured by an informed, credible and evolving strategy? • To what extent are programmes related to deforestation and biodiversity based on solid evidence of ‘what works’ in protecting sensitive ecosystems and promoting sustainable livelihoods for those that inhabit them? • To what extent does the design and implementation of UK aid programmes respond to the needs and priorities of affected communities – particularly women, poor and marginalised groups, and indigenous peoples? |

| 2. Coherence: How internally and externally coherent are UK aid programmes aimed at halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss? | • How well has the UK worked with and influenced partner countries, multilateral institutions, other donors, and climate finance agencies to scale up and improve action on protecting forests and biodiversity? • How coherent and coordinated are programmes across the UK government and within the three departments, and how well is this coherence managed? • How well has the UK engaged with the private sector (within the UK and overseas) to increase its positive contribution and reduce its negative impacts on forests and biodiversity internationally? |

| 3. Effectiveness: To what extent has UK aid contributed to halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss? | • How effective has UK aid been in helping to create the enabling conditions (governance and policy) to address deforestation and biodiversity loss, and benefit poor people? • How well are UK aid programmes helping to build sustainable, locally led governance structures that protect forests and other sensitive ecosystems? • How well is UK aid generating evidence for, learning from, replicating, and scaling forest and biodiversity programmes that have been effective, and is this having a broader impact? |

Methodology

Our methodology for the review included six components:

- Literature review: We reviewed literature on the causes and extent of the global deforestation and biodiversity challenge, the nature of the international response and the evidence on ‘what works’ in addressing it.

- Strategy review: We reviewed the UK’s policies, commitments and approaches relating to halting deforestation and conserving biodiversity.

- Multilateral channels review: We assessed how the UK has participated in and influenced international efforts to halt deforestation and reduce biodiversity loss.

- Programme reviews: We reviewed a sample of nine programmes aiming to halt deforestation and prevent irreversible biodiversity loss funded from UK International Climate Finance (see Annex 1 for details). The sample was selected to provide a mixture of geographic focus, programme types and funding mechanisms, and to cover all three responsible departments (DFID/FCDO, BEIS and Defra). The nine programmes have combined budgets of around £709 million, representing over half the portfolio by value.

- Country case studies: We prepared case studies of UK efforts in Colombia, Ghana and Indonesia – three diverse countries with significant rates of deforestation and a concentration of UK programming. The case studies assessed how well UK programmes had contributed to national efforts to protect forests and ecosystems, and how the UK had used its aid programmes to engage with national and international stakeholders. During virtual visits to each country, we undertook key informant interviews and conducted roundtables with UK government representatives, national offices, other donors, implementing partners, experts and civil society organisations.

- Citizen engagement: An important component of our methodology was to hear the views of people directly affected by UK aid programmes. We engaged national research partners to undertake consultations with citizens, including forest-dependent people, in three regions of Colombia and Indonesia where the UK has programmes that engage directly with communities. As the citizen engagement was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was governed by location-specific risk assessments and research protocols, to protect both participants and researchers. Quotes from those consulted are featured throughout the report.

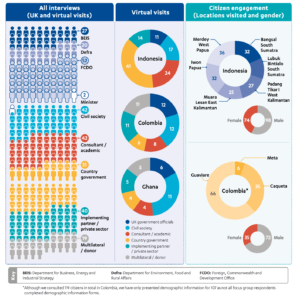

Figure 1: Summary of methodological elements of the review

Altogether, we conducted around 150 interviews covering 295 key stakeholders, including over 100 UK government officials, and reviewed close to 1,500 documents (see Figure 2). Through our citizen engagement exercise, we spoke to 291 individuals in Indonesia and Colombia.

Our methodology and approach were independently peer-reviewed. We provide a full description of our methodology and sampling in the approach paper.

Box 2: Limitations to our methodology

COVID-19: The COVID-19 pandemic placed restrictions on travel. Interviews and country visits were conducted remotely and citizen engagement was undertaken by national partners, with appropriate protocols to safeguard researchers and participants.

Data on impact: The long causal pathways associated with halting deforestation and biodiversity loss, the range of other actors involved in this area and frequent data limitations meant that assessing and attributing impacts at country level was challenging. We depended primarily on programme monitoring data and evaluations. We conducted our own assessment of the credibility of this data, for instance by triangulating results through key informant interviews and citizen feedback. Lack of impact results from more recent projects may also be due to insufficient time elapsed for results to become apparent.

Influencing: While all three departments have invested a significant amount of effort in international influencing, the practical impact of this is difficult to assess.

Figure 2: Breakdown of stakeholder interviews, virtual visits and citizen engagement

Background

The world’s tropical forests and biodiversity are diminishing at an alarming rate

Human activities have already severely altered 75% of the Earth’s land, reducing its productivity by over 23%. The majority of global ecosystems are in decline, including many that are an essential part of sustaining human life. Some are reaching tipping points: there is a growing risk, for example, that the Amazon will shift from rainforest into savannah.

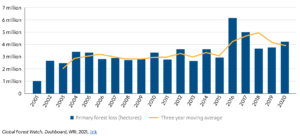

The data shows a devastating rate of deforestation: around the world, 178 million hectares were lost between 1990 and 2020, out of a total area of 4.1 billion hectares. Primary forest loss reached a record high in 2016, and in 2019 was once again on the rise. As the World Resources Institute put it, this equates to the loss of a football pitch of rainforest every six seconds (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Global tropical primary forest loss, 2001-2020 (hectares)

Global Forest Watch, Dashboard, WRI, 2021.

Biodiversity loss is closely linked to deforestation. Over 80% of the world’s terrestrial biodiversity can be found in forests. Tropical forests, in particular, are among the most diverse ecosystems on the planet: covering just 7% of the globe, they support over half of all terrestrial plant and animal species. Biodiversity loss also has a range of other drivers, including changes in land and sea use, loss of pollinators, overharvesting, climate change, invasive alien species, and pollution of air, water and soil. Since 1970, global ecosystems have declined by 47% in size and condition, and 41% of known insect species and 68% of vertebrate species have declined. On average, a quarter of all species in assessed animal and plant groups are threatened and around a million face extinction within decades unless action is taken.

Deforestation and biodiversity loss have a direct impact on the lives and livelihoods of local communities, including indigenous peoples. A quarter of the world’s population, and 90% of the world’s people living in extreme poverty, depend on forests for some part of their livelihoods. As patterns of land use change and resources become scarcer, poorer communities often lose access to forests and natural resources, resulting in greater inequality and marginalisation. Forest and biodiversity protection efforts can conflict with local land tenure claims and forest use practices, particularly affecting indigenous peoples and women’s access to forest resources. Within local communities, women are often responsible for collecting forest products for household and subsistence needs, and the literature suggests that they have an important role to play in strengthening institutions for forest management. However, women, young people and poorer people are often excluded from consultation around the design and implementation of initiatives to halt deforestation and prevent biodiversity loss, which are, as a result, less likely to meet their needs and priorities.

During our consultations with people in Indonesia and Colombia, we heard how forest destruction and declining biodiversity had affected their lives.

Magpies, tekukur, punai, merbak, finches and tiung birds used to appear in many residential areas. However, because the forest is getting smaller, bird sightings are less frequent. Local leader, Padang Tikar, Indonesia

We, the farmers, are seeing that we need to conserve the forests that we own; if one destroys the forest, all is over. The animals leave, temperatures rise, weather changes. Farmer, member of ASCATRAGUA, Meta, Colombia

Our three case study countries – Colombia, Ghana and Indonesia – have all experienced continuous forest loss over the past five years. Indonesia is among the world’s top three countries for forest cover. Its annual rates of forest loss, though high, have been brought down in recent years through improved law enforcement and a moratorium on clearing forest for oil palm plantations (see Figure 4). Colombia’s rate of deforestation increased after the 2016 peace agreement led to changes in land occupation patterns in the Colombian Amazon.

Figure 4: Annual forest loss and major drivers of forest loss in Colombia, Ghana and Indonesia

Source: Deforestation Fronts: Drivers and responses in a changing world, WWF, 2021; Global Forest Watch, Dashboard, WRI, 2021, link; Global Forest Resources Assessments, FAO, 2020.

Human activity is behind most direct drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss, including overexploitation of resources, human-induced fires, invasive plant species, excessive logging, and the expansion of agriculture, infrastructure and urban areas. Agriculture is the main driver of global deforestation and land conversion, almost half of it illegal. Other underlying drivers include agricultural subsidies, commodity markets, financial investment, population growth and increasing consumption. Addressing these complex drivers requires equally complex action.

The UK has made a series of global commitments

The UK has been an active participant in a substantial number of international initiatives and agreements on tackling deforestation and biodiversity loss. Examples include:

- the New York Declaration on Forests, which called for a halt to global deforestation by 2030

- the Amsterdam Declarations on eliminating deforestation from European agricultural imports

- the Bonn Challenge, which aimed to restore 350 million hectares of degraded land by 2030.

In 2015, the governments of Norway, Germany and the UK committed to increase support for REDD+ to at least $5 billion in the period from 2015 to 2020. They also committed to partner with the private sector to support deforestation-free supply chains, and to integrate a wide set of interventions relating to capacity building, inclusion and participation of indigenous peoples and local communities, and land tenure.

The UK has been active in international initiatives on biodiversity and combating illegal wildlife trade, and has ratified the 1976 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals.

Box 3 outlines the UK’s approach to addressing the drivers of deforestation in the period from 2015 to 2020. In parallel to our review, a new International Nature Strategy was under preparation, focusing on UK support for ambitious global action, although a decision has been taken to not make this public. We were told that an updated UK International Climate Finance (ICF) strategy which included efforts to halt deforestation and prevent biodiversity loss was under development. This new ICF 3.0 strategy is an outstanding issue from previous reviews, and is not yet finalised.

Box 3: How UK aid aims to address deforestation drivers (2015-2020)

Supporting sustainable, climate-resilient growth: Working at national and sub-national levels to strengthen governance, clarify land tenure, implement sustainable land-use planning, raise agricultural productivity, and ensure sustainable use of natural assets (including biodiversity) to support growth.

Driving innovation and creating new partnerships with the private sector: Leveraging and accelerating commitments to remove deforestation from agricultural commodity supply chains.

Supporting negotiations and building an effective international architecture: Incentivising forest nations to develop and implement ambitious REDD+* programmes to realise the potential of forests and land use for global mitigation.

Meeting the development needs of the poorest and most vulnerable, particularly women and girls: Helping some of the most marginalised communities in the world to gain secure rights over the forests upon which they depend, improve their livelihoods and help to build resilience.

Source: ICF forests and land use spending review paper, UK government, 2015.

*REDD+ is an international mechanism to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries, see link

The UK has made a number of funding commitments to respond to the global challenge

The UK committed to providing at least £5.8 billion from the aid budget in climate finance for developing countries between 2016-17 and 2020-21. At the 2019 UN General Assembly, it pledged to double that figure to £11.6 billion for the next five-year period. The government uses the label “UK International Climate Finance” (ICF) for funding that contributes to this commitment, which includes spending by DFID/FCDO, BEIS and Defra. It supports both mitigation (measures to reduce climate change) and adaptation (helping developing countries deal with the effects of climate change) in roughly equal proportion. Projects that reduce deforestation contribute towards both mitigation and adaptation, and are estimated to comprise around 13% of the ICF portfolio over this period. We calculate that it amounted to almost £1 billion over our review period (see Figure 6).

In September 2020, the prime minister signed the ‘Leaders’ Pledge for Nature’ at a virtual UN event, committing to put nature and biodiversity on a road to recovery by 2030. In January 2021, the prime minister announced that the UK would commit at least £3 billion (around 25%) from the current ICF phase to solutions “that protect and restore nature and biodiversity”. The UK and Italy plan to co-host the next UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in 2021, delayed from 2020 by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The three departments that contribute to ICF manage their programmes separately, according to their own rules and procedures. A cross-government ICF Strategy Board was established to provide strategic direction and ensure coherence with UK government policy and across departments, while a Management Board monitors expenditure, delivery and risk. The government also recently established a Cabinet Committee on Climate Change and a National Strategy Implementation Group for Climate Change, to lead on its commitments for the coming five-year period.

Figure 5: Timeline of the UK’s significant forest and biodiversity commitments, decisions and events

Source: Information gathered through interviews with UK government officials and publicly available data.

Biodiversity loss was not a major focus for UK aid during most of our review period. Most expenditure in this area falls outside ICF, with the exception of contributions to multipurpose international funds such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Various bilateral initiatives have been created to follow up on the UK’s international commitments – most notably the Darwin Initiative, a small grants facility announced at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro that has been operated by Defra since 2001. More recently, there has been greater recognition of the importance of biodiversity, as illustrated by the commissioning of the Dasgupta Review (see Box 4) by HM Treasury in 2019. Given this increasing focus on ‘nature’ in UK government policy, a cross-government Nature Board has also now been established (in addition to the committees mentioned in paragraph 3.13) and various structures put in place to support the UK’s preparations for COP26.

Box 4: The Dasgupta Review

Published in February 2021, The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review is an independent review commissioned by HM Treasury. The review considers how nature should be accounted for in economic decisions. It argues that nature is our most precious and valuable asset but has been systematically undervalued and, therefore, mismanaged. Three key features of nature – mobility, invisibility and silence – have led to its overconsumption. As a result, the decline in biodiversity is occurring at a faster rate than ever before, endangering the prosperity of both current and future generations. The review finds that the demands placed on nature by economic activity far outweigh nature’s capacity to supply the goods and services that humans rely on. It calls this phenomenon ‘impact inequality’.

The review presents a number of options for change and calls for urgent transformative action, including:

- Ensuring that demands on nature do not exceed sustainable supply, and increasing the global supply of natural assets.

- Adopting improved metrics for economic success that fully account for natural capital.

- Transforming institutions and systems to make them more sustainable, notably finance and education.

The review concludes by acknowledging that its framework of the economics of biodiversity has been set out in anthropocentric terms. Yet, it says, nature has its own intrinsic, often sacred, value which has been under-recognised. If we were to value nature not only for its use to us but also for its intrinsic value, there would be even greater reasons to protect and promote it.

The UK’s aid is spent by several departments, through bilateral and multilateral channels

UK aid for halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss is provided through a mixture of bilateral and multilateral channels. A substantial part is in the form of contributions to large international climate funds, such as the Green Climate Fund (total UK commitment £720 million between 2015 and 2019, plus another £450 million in 2020 as part of the UK commitment to £1,440 million between 2020 and 2023). These funds work across multiple areas and do not report on the share specifically going towards conserving forests and biodiversity. During our 2015-2020 review period, aid spending on initiatives that incorporate forest- and biodiversity-related activities was almost £1.2 billion. As Figure 6 shows, we calculate that over £700 million of this supported the conservation of forests, with a further £444 million supporting projects covering forests and biodiversity, and the balance (£66 million) going to biodiversity-only areas.

Over half of the portfolio spend (59%) is targeted towards addressing deforestation, climate change mitigation and reducing emissions. Efforts that encompass both protecting forests and biodiversity represented 37%. The remaining 4% of the portfolio is dedicated to efforts to protect biodiversity, mainly through bilateral channels.

Figure 6: UK aid spent on halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss, 2015-2020

Source: Information provided to ICAI by the government during the evidence gathering process. Note: Not all figures add up due to rounding to whole numbers.

DFID/FCDO programmes were both bilateral and multilateral, including contributions to multilateral climate funds such as GEF and the Green Climate Fund (GCF). There were dedicated forest and land-use experts within DFID’s Climate and Environment Department (now transferred to FCDO), working on centrally managed programmes and DFID/FCDO’s engagement with the key multilaterals. Management responsibilities for programmes were shared across regional departments and country offices.

BEIS spent around £320 million on reducing deforestation through seven projects, including a contribution to the GCF and six other programmes. Of these, all but three were multi-bi programmes (that is, programmes delivered by a multilateral delivery partner but where BEIS had a role in specifying the purpose of the funding and, in some cases, the recipient). Its programmes were either managed centrally or by staff in UK high commissions and embassies (such as in Colombia and Brazil).

Defra spent around £296 million through 13 projects (five multilateral, three bilateral and five multi-bi). Defra currently has only one representative overseas (in Brazil). The majority of its programming was therefore managed centrally or through implementing partners, including multilateral organisations.

There were a number of jointly funded and managed bilateral and multi-bi programmes, including Investments in Forests and Sustainable Land Use/Partnerships for Forests, the BioCarbon Fund and projects tackling the illegal wildlife trade, representing just over £144 million of the portfolio.

Findings

In this section, we present the main findings from our assessment of the relevance, effectiveness and coherence of UK official development assistance (ODA) for halting deforestation and preventing irreversible biodiversity loss. A summary assessment under these three headings is presented in the conclusions section.

UK programmes have successfully targeted the most relevant drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss

The programmes in our sample are focused on addressing most of the important direct drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss in each national context. For example, in Ghana, the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility and the Partnerships for Forests programme set out to reduce the impact of cocoa production on deforestation and forest degradation. In Colombia, several programmes are working to develop sustainable ranching models and tighten law enforcement, to reduce illegal forest clearance. In Indonesia, a number of spatial planning and land-use governance programmes sought to address the negative effect of insecure land tenure on the environment. Issues of cattle ranching in Colombia and land rights in Indonesia were both confirmed as relevant and significant drivers of deforestation during our consultations. We were told by local people in Indonesia and Colombia that UK programmes are addressing key drivers of forest loss.

In the past, there were many activities that damaged the environment, such as farmers who planted rice fields by burning. Currently, land use without burning has been introduced so that method is no longer in use. We also developed a Village Regulation on spatial planning. Village Chief, Bangsal Village, Ogan Komering Ilir, South Sumatra, Indonesia

Programmes such as Visión Amazonia38 have a positive impact on forest conservation since they generate improved environmental consciousness and offer supplies to community members. For example, the supplies given to the project beneficiaries were used to keep livestock out of the forests and protect water sources. That’s why I keep out of the forest to allow regeneration. Farmer, member of ASOPROCAUCHO, Calamar Municipality, Guaviare, Colombia

While the programming is targeted towards drivers of deforestation, this does not necessarily mean that all the interventions are sufficient to make a difference. Some important drivers have not been significantly addressed to date, such as oil palm investment in Indonesia, land grabbing in Colombia and illegal mining in Ghana. There are also significant indirect drivers – such as financial investment, agricultural subsidies, rapidly growing consumption and population growth – that are not directly or significantly addressed by UK ODA, although the Global Resource Initiative supported by Partnerships for Forests has undertaken research and policy advocacy highlighting the need for UK action to address these issues. This contributed to the proposed requirement in the UK’s Environment Bill, currently before Parliament, for greater due diligence from companies in respect of certain imported forest risk commodities.

The three departments – the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Department for Business, Skills and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs (Defra) – are employing a wide range of approaches. Some are engaging with the private sector, in recognition of the importance of global trade in commodities such as palm oil and soy in driving deforestation. Others use results-based finance, which provides funding to partner countries based on demonstrated success in halting deforestation, to encourage them to reform national laws and policies. There are efforts to promote sustainable (green) finance models through the eco.business Fund project. The Darwin Initiative and Illegal Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund offer small grants for local initiatives on biodiversity and protection of wildlife to support poverty reduction. Other projects support mangrove restoration, forestry, sustainable agriculture and community-based enterprises. As discussed below, the variety of these activities raises questions as to whether the resources are being used in a strategic way.

The UK has played a significant role in promoting global cooperation on the drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss

The UK is recognised as an active, influential and well-informed participant in international policy processes on forests and biodiversity. We found evidence of positive UK influence in a range of international initiatives, including:

- the New York Declaration on Forests (2014)

- the EU Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade Action Plan and more recently the EU Timber Regulation (2013)

- the United Nations General Assembly Leaders’ Pledge for Nature (2020)

- the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (particularly support to REDD+)

- the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

- the Convention on Biodiversity

- the London Conference Declarations on the Illegal Wildlife Trade (2014/2018)

- the Amsterdam Declaration

- the Tropical Forest Alliance

- the Global Consumer Goods Forum

- the Global Resource Initiative.

Its efforts have helped to mobilise finance and encourage international cooperation. In 2015, the UK entered into a joint agreement with Norway and Germany on tropical deforestation, with a joint pledge of $5 billion. Since 2015, it has entered into a number of partnerships on sustainable commodities and supply chains. It recently chaired the Amsterdam Declaration Partnership, which was instrumental in shaping European action on palm oil and other forest-risk commodities. It has helped to promote international action to combat the illegal wildlife trade, under the 1976 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Across these international processes, the UK has used a variety of influencing channels, from diplomatic engagement to support for non-governmental organisation (NGO) advocacy.

There has been mixed success in influencing private sector regulation and practice. The UK has focused on two areas: encouraging companies to make voluntary commitments to reducing the impact of their actions, and improving regulation of the commodities they trade. Progress on implementing voluntary commitments for commodities such as cocoa and soya has so far been limited, linked to practical challenges in certifying products as sustainable or deforestation-free, especially from smallscale producers.

Consequently, the focus has shifted towards regulatory measures, both within the UK and internationally. In 2019, following pressure from the UK, European consumers and civil society organisations, the EU announced a range of initiatives to reduce the environmental footprint of European commodity imports. NGOs funded through the UK’s Forest Governance, Markets and Climate (FGMC) programme supported the passage of these reforms through research and advocacy. The UK government has used its support to the Amsterdam Declaration Partnership to encourage European partners to develop strategies for addressing sustainability challenges within the palm oil, cocoa and soya sectors.

One notable success has been the FGMC programme’s engagement with China, which is a major importer of tropical timber and other forest-risk commodities. This support contributed to China’s adoption of a new forest law in 2019, which introduces some limited due diligence obligations for Chinese companies importing timber products.

The UK has influenced several multilateral funding bodies to improve focus and capability

A significant share of the UK’s deforestation and biodiversity portfolio is delivered through multilateral partners, such as the World Bank, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF) (see Figure 6). The UK has used its position as a funder to influence the design of their funding instruments.

For example, an Evaluation and Learning Initiative (E&LI) established under the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) was initially opposed by a number of funders in the belief that planned external evaluations were sufficient. The UK government argued strongly for its inclusion and offered to cover a significant share of the initial E&LI costs. Following a successful first phase, a second phase of the E&LI (starting in 2020) was fully funded from the CIF core budget. Furthermore, the UK has used its position on the board of the World Bank to strengthen the emphasis on biodiversity within the Bank’s overall governing principles. Efforts such as these have strengthened UK multilateral aid in this sector, alongside the much larger international finance that flows through these channels.

The UK’s engagement with multilateral organisations has also brought about benefits for low-income countries. In 2019, Defra’s engagement with the World Bank led to 15 countries being provided with additional funding to counter biodiversity loss. UK influence also contributed to GEF allocating a greater share of its funding to biodiversity and to low-income countries, and introducing rules requiring middle-income countries to contribute relatively more co-finance to projects supported by GEF.

UK support for NGO advocacy fills a useful niche

Civil society actors have a role in many countries in holding government and the private sector to account, to reduce the drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss. The UK portfolio includes a range of support to NGOs, to help build their capacity for effective advocacy. The evaluation of the FGMC programme (and subsequent research commissioned by FCDO) found that partnerships between international, national and local NGOs in timber-producing countries have helped to amplify the voice of marginalised forest communities (including indigenous peoples) and have led to improvements in national policies and improved accountability in national governments and the private sector.

The Darwin Initiative and the Illegal Wildlife Trade Challenge Fund both support local civil society organisations, helping to promote initiatives to protect biodiversity that also work for the benefit of local communities.

We received feedback that UK-funded projects had successfully engaged with communities, often through civil society organisations.

Confidence in Visión Amazonia [REDD Early Movers] has grown considerably, especially since its second phase which is currently in development. Expectations were fulfilled and many community members that were sceptical in the beginning now want to join and participate. The impact of the project has generated interest and non-beneficiaries are now asking how they can join. Farmer, member of ASCATRAGUA, Vista Hermosa Municipality, Meta, Colombia

This NGO provides education on forest issues and goes into villages to assist in mapping customary forests, so that we know our rights to the land. As I come from Masyeta, I have rights to the land there even though I live in Merdey. And if there are other people, for example, a construction project that wants to open a road, or a company that enters it, the company must request access from those who have the rights, otherwise, the company may not enter. The role of Panah Papua [NGO] is very helpful. Man, Merdey Village, Bintuni, Papua, Indonesia

[Panah Papua is an NGO that works with The Asia Foundation on the Supporting a Sustainable Future for Papua’s Forests programme]

Box 5: Positive examples of UK support to civil society

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Improving Livelihoods and Land Use in Congo Basin Forests programme worked through a network of national NGOs in five countries to help forest communities establish effective community forestry processes, including sustainable rural enterprises linked to forest management. The project succeeded in influencing legal reforms across the Congo Basin. With funding from this project, Rainforest Foundation UK (together with local partners) supported the establishment of a National Community Forestry Roundtable, lobbied successfully for a government decree on community forestry and contributed to the development of operational guidelines on community forestry in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In Indonesia, the Forest, Lands and Governance programme aims to improve governance in the forest and lands sector. An accountable grant to the Asia Foundation supported over 50 national NGOs in 13 provinces, which worked on a range of initiatives including community forestry, land tenure, freedom of information requests on questionable land-use decisions, cancelling illegally issued mining permits, improved local and national policies, and provincial moratoria on new mining and palm oil concessions.

UK aid has made positive contributions to knowledge, institutions, governance and policies in the case study countries

UK support has strengthened institutions and policies across a range of countries. Indonesia, Ghana and Liberia have all witnessed significant reductions in illegal logging in recent years, linked to successful government policies often designed and implemented in partnership with national civil society organisations. Furthermore, new laws negotiated and agreed as part of the Voluntary Partnership Agreement process have helped improve health, safety and employment conditions in the domestic timber markets in countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia and Ghana. UK support through the MultiStakeholder Forestry programme in Indonesia has been instrumental in strengthening the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities to forest land. The stakeholders we consulted were in agreement that UK support had resulted in meaningful improvements in governance, particularly around transparency and accountability.

Box 6: The Forest Governance, Markets and Climate programme

DFID’s £280 million Forest Governance, Markets and Climate (FGMC) programme has been running since 2011 and is one of the most successful in the portfolio. It aims to strengthen sustainable forest management, improve governance and promote domestic and international trade in legally produced timber and other forest-risk commodities. Drawing on learning from three decades of forest sector projects, it aims to adopt a politically smart, evidence-based and locally led approach, working with a wide range of government, civil society and private sector partners. Its investments are significant, relative to the size of the timber sector in the countries where it works, which enables it to achieve meaningful impact.

FGMC works on both the demand and the supply side. It has helped to influence major consumer markets in Europe and China, while supporting in-country reforms in producer countries through Voluntary Partnership Agreements. The programme, and earlier phases of UK support to the forest sector, have been instrumental in shaping European policy on timber, including the EU’s Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade Action Plan and the EU Timber Regulation, passed in 2011, requiring European timber operators to demonstrate legality of timber imports. More recently, the programme has supported China in introducing new legislation requiring Chinese timber importers to conduct due diligence of their supply chains.

In Colombia, the REDD Early Movers programme (in partnership with Norway and Germany) and the BioCarbon Fund have both built the capacity of government institutions at national and sub-national levels, and improved coordination between the government bodies involved in land-use decision-making. The REDD Early Movers programme has built technical capacity in forest monitoring, reporting and verification, developed a carbon registry, promoted social and environmental safeguards, established benefit-sharing arrangements and mechanisms, and built the capacity of law enforcement institutions. These processes have taken longer than expected to become fully operational, but the effort has built national ownership and is therefore more likely to lead to sustainable outcomes.

Farmers in Colombia told us that Visión Amazonia (part of the REDD Early Movers programme) had encouraged the adoption of sustainable farming practices.

We have taken care of the territory we live in. We, the farmers, established rules among communities, we do not log close to the streams or water sources, we established quotas for hunting and protect the animals that are part of our resources. Farmer, member of ASCATRAGUA, Vista Hermosa Municipality, Meta, Colombia

Visión Amazonia has generated changes towards how products are produced, it has focused on community necessities. It recognises the inputs and the impacts of each beneficiary with supplies for their needs and farms. Farmer, member of ASACAMA, Vista Hermosa Municipality, Meta, Colombia

Ghana has made good progress on strengthening forest governance and legal compliance over the past decade. The UK assistance has helped to support these changes, especially through the FGMC programme, building strong relationships with stakeholders at all levels and making good use of the positive incentives created by the Voluntary Partnership Agreement and the EU Timber Regulation (see Box 6). Long-term UK support to Ghanaian civil society organisations has helped to promote more participatory policymaking and improvements in transparency and accountability. Support from the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility has helped build capacity within the Ghana Forestry Commission to plan, coordinate, monitor and report on REDD+ actions, making Ghana a leader across the continent in this area. The Partnerships for Forests programme is also helping to promote useful reforms in the cocoa and palm oil sectors. However, while these programmes are making individual contributions, there is insufficient evidence of a coherent strategy or coordinated implementation and learning that actively links them at country level.

In Indonesia, UK support has also improved governance in the forest and land-use sector, including by building the capacity of national NGOs to engage in policy process. The FGMC programme helped to establish an independent forest monitoring network, to improve transparency. The Forest, Lands and Governance programme and the Spatial Planning programme in Papua and West Papua have supported more transparent and accountable decision-making on land use and contributed to improved laws and regulations on spatial planning, social forestry and natural resource management.

In Indonesia, local residents confirmed that there had been improvements in forest governance and management.

There are many positive roles of local institutions. During the area mapping, they surveyed the clan boundaries and entered the forest to conduct the survey. Woman, Merdey Village, Bintuni, Papua, Indonesia

The project [carried out by SAMPAN] is what the community needs because it reflects the aspirations of the community. Village secretary, Padang Tikar Village, Kubu Raya, West Kalimantan, Indonesia

The level of resources devoted to addressing deforestation and biodiversity loss is dwarfed by the scale of the challenge

Across our three case study countries, stakeholders confirmed that forest loss is continuing apace, driven by mining (both legal and illegal), infrastructure development and expanding agriculture. The rate of forest loss is closely linked to economic growth. As the Dasgupta Review concluded, growing human populations and global patterns of consumption are exceeding what nature can provide on a sustainable basis.

The UK portfolio includes initiatives to address the deforestation impacts of agricultural commodities such as palm oil, soya and beef. The Global Resource Initiative, a UK-supported taskforce, has made recommendations on how to ensure that markets in agricultural and forestry products avoid deforestation and environmental degradation overseas, while supporting jobs and livelihoods. These included imposing a due diligence obligation on business and finance to eliminate unsustainable practices from their global supply chains and investment portfolios. Part of this recommendation has been picked up in the UK’s Environment Bill, which will require large companies to ensure that the commodities they purchase are not a product of illegal deforestation.

While these are positive interventions, private investment is still flowing into forest-risk sectors at a huge rate: one analysis suggests that new investment into sectors that drive biodiversity loss totalled $2.6 trillion in 2019. By comparison, UK aid for biodiversity in 2018-19 was just $195 million. The global biodiversity financing gap is estimated at $711 billion. While this mismatch in scale is acknowledged by the UK officials that we interviewed, there is little discussion of it in the strategy documents provided to ICAI. Tackling unsustainable investment is therefore an important frontier for future action.

While the UK has actively promoted international agreements on protecting forests and biodiversity, global implementation falls well short of the level of ambition in the agreements. According to Global Biodiversity Outlook 5, none of the Aichi Biodiversity Targets (which articulate the goals of the Convention on Biological Diversity) will be fully met. The New York Declaration on Forests, which is a voluntary instrument, includes the goal of ending natural forest loss by 2030, but the current rate of progress is not enough to achieve this objective. It also contained a commitment to eliminating deforestation from agricultural commodities by 2020, which was not achieved. Although the rate of tree cover loss due to commercial agriculture has been declining in recent years, the 2018 levels remain similar to those seen in the decade preceding the New York Declaration.

Our citizen engagement exercises similarly evoked the scale of the challenge when activities relating to deforestation continue to be profitable.

In Colombia, citizens recounted how land-use changes relating to livestock and illegal crops continue to impact on forests.

The biggest forest predator is livestock. Ranchers come to Guaviare, buy land and establish extensive livestock practices. Low-price land is the entry point to extensive livestock farming, converting forest to pasture. Man, farmer, Calamar Municipality, Guaviare, Colombia

Illegal crops occupy smaller areas and are more profitable than livestock. Much of the resources obtained from illegal crops are invested in livestock. So, there is a direct relationship between those activities and deforestation. Man, farmer, member of ASOES, Cartagena del Chairá Municipality, Caquetá, Colombia

The deforestation- and biodiversity-related interventions in the UK portfolio are spread across a wide range of approaches, interventions, value chains and geographies. Despite some positive results, most lack the scale and reach to make a difference at the global level. Many are small-scale pilots with only local impact. Given the scale of the challenge, there is a clear case for focusing the resources on interventions that tackle drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss at a more systemic level.

UK efforts on commodity-related deforestation are effective when they adopt a systematic approach

Changing land-use patterns is one of the most serious drivers of deforestation and biodiversity loss. Much of it is driven by conversion of land (often illegally) to produce commodities for international markets – notably beef, soy, palm oil and wood products. Other agricultural commodities such as cocoa, rubber and coffee also have significant land-use impacts.

The three country case studies confirmed the scale of the challenge presented by commodity-related deforestation. In Ghana, illegal mining, cocoa, illegal logging and agriculture were all identified as drivers of forest loss. In Colombia, deforestation and biodiversity loss are strongly linked to land grabbing and the growth of illicit markets in the Amazon (narcotics, mining and illegal logging), and extensive, low-productivity cattle ranching. In Indonesia, oil palm expansion has historically been a major cause of forest loss. Indonesia has enjoyed some success in recent years with temporary bans on the conversion of primary forest and peatlands. However, Indonesia’s forests remain under threat from national plans to expand biofuel consumption, continuing encroachment of smallholder farmers into primary forests and unrevoked plantation licences.

The FGMC programme (see Box 6) offers a strong example of how to approach commodity-related deforestation. It supports implementation of the EU Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) Action Plan. While some aspects of the FLEGT approach – notably timber licensing – have proved difficult to advance, evidence from Ghana and Indonesia indicates that the programme has helped reduce illegal logging and improve forest governance.

Several other programmes are also engaging with commodity-related deforestation. In Ghana, Partnerships for Forests is helping to promote sustainable production within the cocoa and palm oil sectors by supporting the Cocoa and Forests Initiative and the African Oil Palm Initiative. It is also supporting private sector partnerships aimed at delivering on commitments to making commodities deforestation-free, and to protecting forests and improving livelihoods.

The expansion of agriculture and plantations into forests was a key concern raised by the citizens we consulted in Colombia and in four of six locations in Indonesia.

In Colombia and Indonesia, local residents described the harmful effects of large-scale agriculture.

Forests are lost due to large landowners, not smallholders. They buy scores of hectares to implement extensive livestock ranching. They log 100 or 200 hectares, pay a fine and that’s it. Man, farmer, member of ASCATRAGUA, Vista Hermosa Municipality, Meta

Since the [oil palm plantation], the condition of the village has changed. Buffalo-grazing places were reduced, and the water was damaged because it became acidic so that there were fewer fish. Young man, Bangsal Village, Ogan Komering Ilir, South Sumatra, Indonesia

In the cases of palm oil and cocoa, UK programmes involve both supply- and demand-side measures. However, work on these and other commodities is less comprehensive than for timber, at a smaller scale in relation to the economic value of the sectors involved, and at an earlier stage. It also lacks policy leverage. The experience of the FGMC and predecessor programmes provides a model for work on other commodity supply chains: it was built on deep sectoral expertise and experience, was genuinely multi-stakeholder, and adequately resourced relative to the scale of the commodity market. It involved a package of demand- and supply-side measures, implemented in formal partnership with both producer and consumer countries, and worked to create clear economic incentives for producers to change their practices. Currently, UK efforts on other forest-risk commodities lack such a systematic approach.

This highlights the importance of effective engagement with the private sector. The UK has committed to working with companies to develop sustainable supply chains. Partnerships for Forests provides a good example, working as it does to influence the private sector on agricultural commodities at global, regional and national levels. However, depth of engagement with the private sector across the ICF portfolio is variable. The UK has helped support some voluntary private sector initiatives promoting greener investment and more sustainable commodity supply chains, but these efforts are small relative to the scale of the challenge. To be effective, they would need to be accompanied by measures to address the large-scale business and investment practices that continue to threaten forests and biodiversity.

The UK’s efforts to halt deforestation and prevent irreversible biodiversity loss lack a coherent, overarching strategy

While the UK has made a number of commitments to address the global challenge of deforestation and biodiversity loss, there is no overarching strategy to guide its efforts. Some general strategies are in place, including the ICF Strategy (2011), the 25 Year Environment Plan (2018), the Green Finance Strategy (2019), and the outputs from the London Conferences on the Illegal Wildlife Trade and related declarations (2014 and 2018). However, these documents do not add up to a sufficiently detailed, clear or consistent set of objectives for addressing deforestation and biodiversity loss, or a coherent and plausible strategic plan for achieving them. Country-level strategies are similarly lacking, and we found no evidence of global programmes being integrated into country business plans. This has resulted in a mix of programmes widely dispersed over geographies, commodities, issues and approaches that, while often making useful individual contributions, lack the combined impact that might have resulted from a clearer strategic focus.

In the period under review, a paper discussing the cross-government international forests and landuse strategy produced in December 2018 is the only document devoted to forests. However, this was a discussion of the work underway at the time, not a forward-looking strategy. Two of the departments – Defra and BEIS – produced relevant departmental strategies. The Defra ICF Strategy 2016-2020 identified protecting biodiverse forests as one of four focus areas, but did not elaborate a strategy to tackle deforestation. The BEIS ICF Governing Principles (2017) document was more strategic. It identified “halting deforestation” as one of three broad thematic areas. Within that, the strategy was to “build on our results-based finance approach to crowd in sustainable investments in forests and land use, and to address key drivers of deforestation by supporting the shift to zero-deforestation supply chains for key commodities”.

The UK’s approach to biodiversity, in particular, has lacked an overall strategy. Addressing biodiversity loss has not been an explicit objective of ICF. Within the ICF portfolio, biodiversity has either been seen as a rationale for tackling deforestation or as a cross-cutting issue. The 25 Year Environment Plan (2018) set out policies and actions to protect and improve the global environment. The Defra ICF Strategy 2016-2020 elevated the importance of biodiversity by identifying the “protection of the world’s most biodiverse forests” as one of four focus areas. However, the emphasis remained on forests and forest projects, with biodiversity benefits a secondary result.

In our 2019 review of ICF’s work on low-carbon development, ICAI recommended that the ICF Strategic Plan, originally set to run from 2011-12 to 2014-15, needed updating. In our follow-up reviews, the issue remained outstanding. We had hoped that a strategy for the new phase of ICF, together with a planned International Nature Strategy, would provide the detailed, clear and coherent approach that had been lacking during the review period. We will return to the outstanding issue of the ICF strategy as part of our follow-up review next year, and provide an assessment of it then.

Coordination across government can be good but is not always so

The agreed division of labour between BEIS, DFID/FCDO and Defra is well articulated and understood across government:

- DFID/FCDO have focused on development, livelihoods, support to fragile states, building resilience, strengthening governance and delivering lower-carbon growth, with a geographical focus on Africa and Southeast Asia.

- BEIS has spearheaded the development of carbon markets and REDD+, with a geographical focus on Latin America.

- Defra has led on biodiversity and UK-focused regulatory measures.

Examples of effective coordination and coherence at policy and operational levels can be found within the forests and biodiversity portfolio. For instance, the cross-departmental Climate Change Unit within British Embassy Jakarta oversees a complex portfolio of projects, including both in-country and centrally managed programmes. In Colombia, where the majority of programme staff are employed by BEIS, there is a well-developed ‘One HM Government’ approach, under a common business plan developed jointly by embassy staff and BEIS. The exception to this pattern is Defra-managed projects, which are run by Defra staff in the UK with some direct contact with embassy staff.

Joint implementation of programmes across departments has supported interdepartmental learning and coordination. The Investments in Forests and Sustainable Land Use programme is shared between DFID/FCDO and BEIS, with a common logframe, coordination framework, delivery mechanism, and monitoring, evaluation and learning facility. Joint programming has brought many benefits, including improved external communication and influencing. GEF and the BioCarbon Fund are also joint programmes (Defra/FCDO and Defra/BEIS, respectively). In the case of the BioCarbon Fund, the two departments have brought valuable perspectives to programme management, reflecting their respective areas of expertise (biodiversity and climate nexus for Defra and private sector engagement for BEIS). Furthermore, useful lessons regarding the development of demand-side measures for timber have been transferred from the FGMC programme to Defra, which is responsible for developing new due diligence regulations under the Environment Bill.

Despite the agreed division of labour between departments, avoidable duplication and fragmentation were evident in some areas of policy and programming. In particular, multiple strands of work on sustainable finance lack a shared approach or clear coordination. DFID/FCDO has supported sustainable finance through the FGMC programme (through accountable grants to Rainforest Action Network and Global Canopy Programme) and through the Forest Lands and Governance Programme in Indonesia (through a grant to the International Finance Corporation). Defra is working on sustainable finance through the eco.business Fund and the Land Degradation Neutrality Fund, while BEIS has developed a business case for a £150 million project, Mobilising Finance for Forests. DFID/FCDO and BEIS are working together to provide finance for sustainable land-use investments through the Partnerships for Forests programme.

In some areas, the geographical division of labour between departments has led to a lack of coherence at the thematic level. For example, in the area of forest-risk commodity chains, cattle and soya are led by BEIS (given its focus on Latin America), while palm oil and cocoa are led by DFID/FCDO (which leads in Southeast Asia and West Africa). This geographical split leaves no clear lead for sustainable commodities as an issue.

There was no consistent approach to coordinating programming at country level, either across departments or between in-country, centrally managed and multilateral programmes. While collaboration in Indonesia and Colombia on biodiversity and forests was effective, it has evolved in each location in an ad hoc way, and there is no common model or approach. We noted that in Indonesia, although the Climate Change Unit brings together the UK government’s work on biodiversity and forests, other sustainable development programmes were managed by a separate FCDO team, with areas of overlapping interest and programming (for instance on low-carbon development). Coordination between centrally managed programmes and the overseas network was often weak. For example, although Ghana is considered one of FGMC’s flagship countries, we found limited knowledge of the programme within the high commission in Accra and no mechanisms to coordinate across the different strands and levels of UK support.

The 2020 National Audit Office report on ‘Achieving government’s long-term environmental goals’ reached similar conclusions, finding that “Government’s arrangements for joint working between departments on environmental issues are patchy.”

The UK has piloted useful technical interventions and has been willing to take risks

Global evidence on ‘what works’ in halting deforestation and preventing biodiversity loss is still emerging.59 In various areas where the evidence base is weak, the UK is engaged in useful pilot projects to test new interventions. For example, the Partnerships for Forests programme is engaged in testing and demonstrating the concept of public-private community partnerships. The REDD Early Movers programme in Colombia and Brazil is seeking to demonstrate that results-based payment offers a viable approach.

A number of programmes are piloting alternative and more sustainable livelihood options. In Indonesia, Green Economic Growth is seeking to fund forest-friendly community enterprises that work within the Papuan context. Its objective is to identify and showcase viable economic alternatives to deforestation. Partnerships for Forests in Colombia and Ghana, and some Darwin Initiative projects, are supporting similar projects. While we have some reservations about the value of further piloting of alternative livelihood approaches (see below), there is a good case for pilots that explore ways of making forest protection work for poor and vulnerable groups.