Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| BEIS | Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, which includes two ODA-spending divisions: BEIS Research & Innovation (R&I) and BEIS Climate |

| CDC | Formerly the Commonwealth Development Corporation, a development finance institution owned by the UK government |

| CERF | Central Emergency Response Fund |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| FCDO | Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office |

| FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office |

| GNI | Gross national income |

| HM Treasury | Her Majesty’s Treasury |

| NAO | National Audit Office |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OECD DAC | The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee |

| ONS | Office for National Statistics |

| SOG | Senior Officials Group |

| Glossary of key terms | |

|---|---|

| Calendar year and financial year | The calendar year runs from 1 January to 31 December. The financial (or fiscal) year used in government accounting runs from 6 April to 5 April the following year. |

| Cash accounting and accrual accounting | Cash accounting and accrual accounting are different methods for recording how cash comes into and out of a business. Cash accounting involves income and expenditure being recorded when money is received or paid. Under accrual accounting, income and expenditure are recorded when a transaction takes place (irrespective of whether cash has been received or paid). |

| Cross-government funds | These funds have their own governance and management structures, and oversee programmes delivered across government departments. These are the Prosperity Fund and the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund, overseen by the Joint Funds Unit. |

| European Union (EU) attribution | The UK is attributed a share of the EU’s External Assistance Budget based on UK contributions to the total EU budget. Each budget line within the External Assistance Budget was attributed to either DFID (as ‘EU attribution DFID’) or other departments (‘EU attribution non-DFID’) based on the aim of the budget line. |

| Financial transactions | Financial transactions are a form of capital used by government to provide loans or equity investment to private sector entities. |

| Financial year underspend | Allocated spend that is not used before the end of the financial year (5 April). |

| Forecasts | Estimated spend by government departments. |

| In-donor refugee costs | OECD DAC rules allow donors to report some of the costs of hosting refugees in donor countries during the first 12 months of their stay as ODA. |

| Investment Committee and Management Board | These were DFID governance committees before the DFID-FCO merger. The Investment Committee met quarterly and provided assurance that DFID's programme portfolio delivered value for money. The Management Board met monthly and provided strategic direction to the management of DFID's operations, staff and financial resources. Both supported the overarching Departmental Board, chaired by the secretary of state. |

| Main and Supplementary Supply Estimates | Government seeks Parliament’s authority for its spending plans through the Supply Estimates process. Government is only able to finance planned activities if Parliament votes for the necessary financial provision. Main Supply Estimates contain the detail of spending plans for a particular year and are presented for parliamentary approval ahead of the financial year in question. Changes are presented at the end of each year through Supplementary Estimates. There is a separate estimate for each department. |

| Monitoring commissions | ODA-spending departments received regular ‘commissions’ (requests for ODA forecasts) from DFID before the DFID-FCO merger, often with a two-week deadline for returns. This commissioning cycle played an important part in the ODA monitoring process. |

| Negative ODA/ ODA reflows | Negative ODA, or ODA reflows, includes any income that is generated as part of investments financed by aid and unspent contributions to programmes or multilateral organisations (such as trust funds) that are returned. As per the 2016 OECD DAC agreement, any profits or dividends paid back to donor governments from private sector instruments should also count as negative ODA or an ODA reflow. |

| Non-departmental ODA | This is ODA that is not spent by any central government department. This includes the EU attribution (non-DFID), contributions to the BBC World Service, Gift Aid and aid spent by the devolved administrations. |

| ODA | ODA is defined by the OECD DAC as government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries. |

| ODA modernisation | ODA modernisation is the OECD DAC-led process of modernising its system for how ODA is defined, monitored and reported. |

| Payment in advance of need | Payment in advance of need is when funds are given before it is demonstrated and agreed that they are needed. Payment in advance of need is not allowed unless approval from HM Treasury is obtained. |

| Promissory notes (PN) | These are legally binding financial commitments by the UK government to provide to the named beneficiary any amount, up to the specified limit, that the beneficiary may demand at any time. DFID used PNs mainly, but not exclusively, as part of the arrangements to make payments to multilateral international development banks and funds. |

| RAG (red, amber, green) ratings | Within their monitoring commissions, departments indicate their level of confidence in achieving their forecasts by the end of the calendar year using a red/amber/green (RAG) rating scale, with red signalling the lowest level of confidence and green the highest. |

| Settlement letters | Following a spending review or spending round, HM Treasury issues settlement letters to departments which lay out their departmental expenditure limits and other controls on spending for each year covered by the spending review. For ODA-spending departments, settlement letters also record ringfenced amounts for ODA-eligible spending by the department. |

| Spender or saver of last resort | As spender or saver of last resort, DFID was required by HM Treasury to spend the difference between non-DFID ODA spend and the 0.7% target to make sure the UK’s ODA commitment was met by 31 December each year. |

| Spending review | A spending review is a governmental process carried out by HM Treasury to set multiyear expenditure limits for departments. The last spending review took place in 2015 and set out expenditure limits for financial years 2016-17 to 2019-20. |

| Spending round | A spending round sets out the government’s spending plans for (usually) one year in the interim of a new spending review. The last spending round took place in 2019 and set out expenditure limits for the financial year 2020-21. |

Executive Summary

The UK is one of only a handful of donors worldwide that meets the international target of spending 0.7% of its gross national income (GNI) on official development assistance (ODA), and one of only two to have enshrined that commitment in law, in the 2015 International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Act. The UK interprets the target as both a floor and a ceiling: the government seeks to achieve but not exceed 0.7% of GNI each year. As the final GNI figure is not known until after the end of the calendar year, and because coordination is required across many ODA-spending departments and cross-government funds, this is a considerable managerial challenge.

This rapid review explores how well the UK government manages the ODA spending target. It assesses the mechanisms for coordinating aid expenditure across ODA-spending departments, and the role played by the former Department for International Development (DFID) as ‘spender or saver of last resort’, required to adjust its expenditure up or down late in each calendar year to prevent any shortfall or overspend. We cover the period since 2013, when the UK first achieved the 0.7% target, to 2019, building on reviews by the National Audit Office (NAO) of management of the target published in 2015 and 2017. The review does not assess whether the target itself is an appropriate one, as this is a matter of government policy and a legislative requirement. We intend to carry out a supplementary review of management of the target in 2020 once spending data is available, given the dramatic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the UK economy and its consequences for UK aid.

Relevance: What is the process for the allocation, monitoring and management of ODA spending targets to and within individual departments, and how well is this process governed and managed?

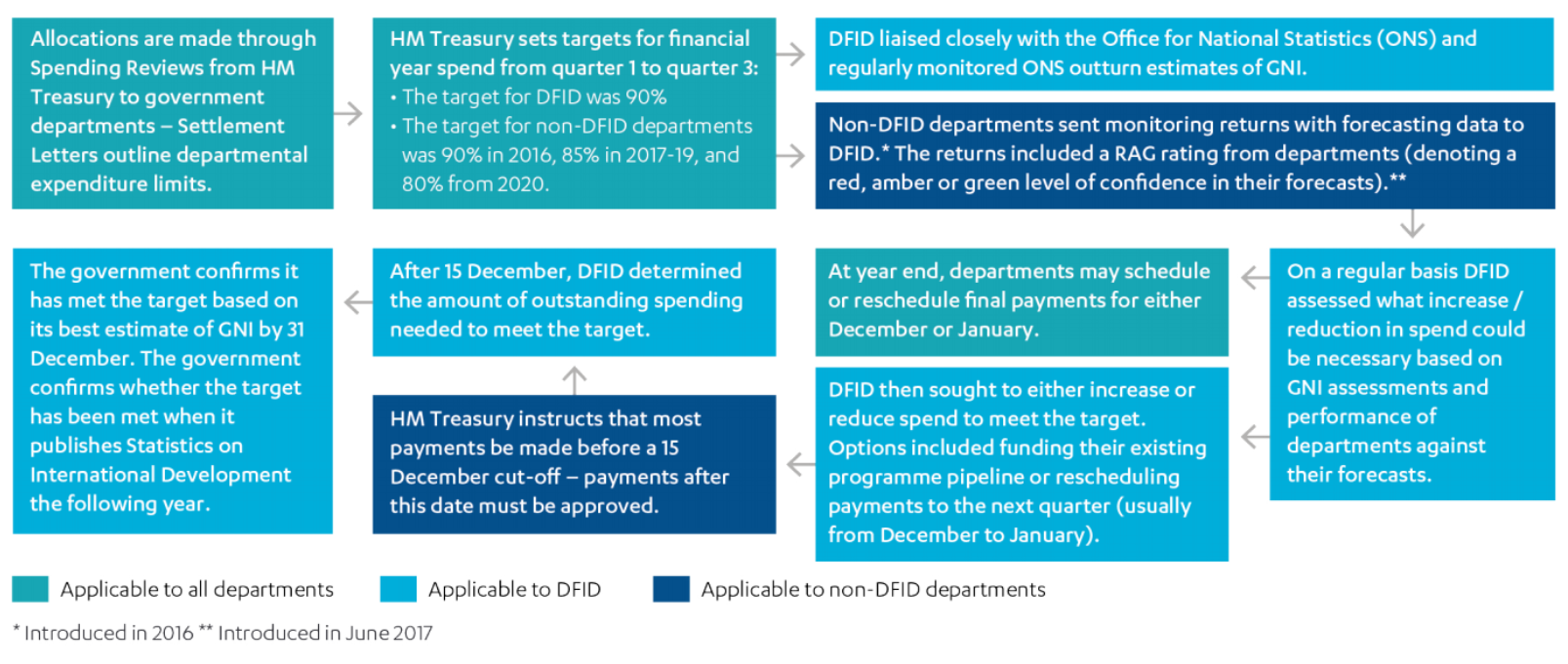

The spending target poses a complex set of financial management challenges for HM Treasury and aid-spending departments. Since the 2015 legislation mandating the target, a set of cross-government coordination mechanisms has emerged, including the Senior Officials Group (SOG), which has overall responsibility for overseeing management of the target. In order to manage delivery of the 0.7% target given difficulties in forecasting aid expenditure and GNI, DFID was assigned the role of spender or saver of last resort in its 2015 settlement letter from HM Treasury. In this capacity, DFID obtained regular spending forecasts from other departments, tracked non-departmental spend (ODA expenditure that does not fall within any department’s budget) and closely monitored GNI forecasts, in order to adjust its spending in response to any gaps in reaching 0.7%. HM Treasury sets targets for all departments, specifying that they must spend 90% of their ODA allocation in the first three quarters of the financial year (later revised down to 85% and then 80% for non-DFID departments) in order to help deliver the target. DFID and HM Treasury used the SOG to engage departments on their spending forecasts, targets and value for money issues. The government used several methods to adjust ODA expenditure towards the end of the calendar year in order to hit 0.7%.

Overall, we found that the UK government has successfully developed several layers of governance that have facilitated increasingly effective cross-government coordination and ensured the 0.7% target has been met each year since 2013. This coordination has been especially useful towards the end of the calendar year, when final adjustments to spending are made. Non-DFID ODA-spending departments have strengthened their oversight of and reporting on the ODA they spend, although their processes are generally less sophisticated than DFID’s were. While the target has provided some perverse incentives for ODA allocations, stronger governance and better management over time have reduced value for money risks.

Efficiency: What are the value for money risks associated with meeting the spending target, and how well do the responsible departments mitigate them?

The increase in ODA spending managed by non-DFID government departments since 2015 (from less than a tenth in 2014 to just over a fifth of the total in 2019) introduced new and sometimes significant value for money risks. Initially, due to capacity challenges, many departments were spending at levels well below HM Treasury-set spending targets, a problem that has eased over time. However, the spending forecasts of these departments remain volatile and there remains a high concentration of expenditure by these departments in the final quarter of the calendar year.

DFID adapted and developed its financial management systems to respond to these challenges and successfully adjusted its spending to ensure that the target has been met every year since 2013. It was able to make use of the flexibility inherent in its programme portfolio, especially through rescheduling multilateral payments and maintaining a pipeline of projects that could be brought forward as needed. Its ability to act as spender or saver of last resort was, however, closely linked to the scale of multilateral contributions, and the challenge becomes more difficult in years when multilateral replenishments are lower than expected. We also conclude that HM Treasury’s ‘one size fits all’ approach to setting spending targets for departments for the first three quarters of the year has not been effective, given departments’ differing spending profiles and constraints.

In examining value for money risks posed by different types of ODA spend, we found no evidence that rescheduling multilateral contributions across calendar years compromised value for money. We have, however, noted that special rules for DFID’s capital budget may have introduced value for money risks and we flag the need to pay attention in the next spending review to mitigating possible risks linked to the reallocation of ODA spent through the EU and to the management of ODA reflows.

Learning: To what extent have departments reduced the value for money risks associated with meeting their spending target?

We found that processes for managing ODA spending had improved across all departments and funds, and most departments were getting closer to meeting their in-year (April to December) spending targets. However, further progress is needed by non-DFID departments to improve the accuracy of forecasting and reduce the amount of spend taking place in late December. We found that the cross-government lesson learning activities led by DFID and HM Treasury, with the participation of other departments, were comprehensive and the findings were well communicated across government. These exercises have led to identifiable changes and have helped to build a more accurate picture of capability gaps in the management of the spending target. However, all of the departments we interviewed as part of this review indicated that they would need additional resources to address these gaps.

Overall, we conclude that the system for managing the target is well suited to handling the typical level of variability experienced in most years since 2013. However, larger shocks – such as major fluctuations in UK GNI forecasts coinciding with significant reductions in multilateral contributions, both of which occurred in 2019 – can pose significant risks. The rigidity of the UK system (compared to other donors) poses more challenges in times of significant shocks. The 2020 OECD DAC peer review noted that the UK could draw on the experience of other DAC members to smooth ODA budgets and expenditure over several years.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

HM Treasury should consider assigning spending targets for the first three quarters of the financial year to ODA-spending departments and cross-government funds that better reflect the structural nature and spending profile of their programme portfolios and reduce negative effects for suppliers.

Recommendation 2

The UK government should lessen the value for money risks associated with managing the 0.7% target by establishing a spending floor for FCDO (as the new spender or saver of last resort) that gives it a degree of certainty over its share of UK ODA spending.

Recommendation 3

The UK government should ensure that a sufficient share of the UK’s ODA portfolio is allocated as multilateral aid, so that ministers have the flexibility they need to manage the target at calendar year end, without compromising value for money or adversely impacting programme delivery (or supplier operations).

Recommendation 4

The UK government should explore ways of introducing greater flexibility into the management of the 0.7% target, including, for example, introducing a ‘tolerance range’ for hitting the target of between 0.69% to 0.71% of GNI, or specifying the target as a three-year rolling average.

Introduction

The UK is one of only a handful of donors which meet the international target of spending 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) on official development assistance (ODA), and one of only two to have enshrined that commitment in law. The UK interprets the target as both a floor and a ceiling: the government seeks to achieve but not significantly exceed 0.7% of GNI each year. With ODA being spent by many departments, and GNI and elements of the UK’s large and complex aid expenditure difficult to predict inyear, this presents a considerable managerial challenge that one former DFID minister likened to “landing a helicopter on a handkerchief”.

This rapid review explores how well the UK government manages the ODA spending target. It assesses the mechanisms for coordinating aid expenditure across departments, and the role played by the former Department for International Development (DFID) as ‘spender or saver of last resort’ required to adjust its expenditure up or down in each calendar year to prevent any shortfall or overspend. We cover the period from 2013, when the UK first achieved the target, to 2019. We intend to carry out a supplementary review of management of the target in 2020, once spending data is available, given the dramatic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the UK economy and the aid programme.

Various commentators have raised concerns that a spending target poses risks to the value for money of UK aid. These concerns include: the potential for a greater focus on inputs (spending needed to meet the target) than intended results, the risk of financing poorer quality programmes towards the end of the calendar year, risks associated with increasing contributions to multilaterals and with potential payments in advance of need (not allowed by HM Treasury rules), and challenges arising from managing two year ends using different accounting methods. In this review, we work through concerns raised externally and by the UK government itself to assess whether these value for money risks have materialised, and whether the UK government is managing them appropriately. The review does not assess whether the target itself is an appropriate one, as this is a matter of government policy and a legislative requirement.

The time period we are reviewing precedes the merger of DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO). We therefore refer to the predecessor departments throughout this report. However, a key objective of the review is to guide the new department, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), as well as HM Treasury and other ODA-spending departments, in future management of the spending target.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria | Question |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance | What is the process for the allocation, monitoring and management of ODA spending targets to and within individual departments, and how well is this process governed and managed? |

| 2. Efficiency | What are the value for money risks associated with meeting the spending target, and how well do the responsible departments mitigate them? |

| 3. Learning | To what extent have departments reduced the value for money risks associated with meeting their spending target? |

Methodology

The methodology for this review included the following components:

- An annotated bibliography presents short summaries of literature on the origins, history and perceptions of the 0.7%, and the UK’s approach to managing the target.

- Our data collection, which took place in August and September 2020, included: (i) a review of government documents related to the spending target, (ii) virtual interviews with 42 senior government officials from across government and external stakeholders, (iii) a virtual focus group discussion with 16 representatives from civil society, universities, think tanks and independent experts, and (iv) an open call for written submissions, including from UK government supply partners and grant recipients.

- We conducted case studies of five aid-spending departments and funds and six thematic issues (see Table 2). Together, the departments and funds in our sample accounted for 85% of UK aid spending in 2018.

Table 2: Sampled case study areas

| Department/fund case studies | Thematic case studies |

|---|---|

| • Department for International Development • Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy • Home Office • Department of Health and Social Care • Prosperity Fund | • DFID as spender or saver of last resort • Multilateral aid spending • Non-departmental ODA • Capital spend • ODA modernisation • Humanitarian aid spending (rapid-onset) |

This review builds on the National Audit Office’s (NAO) reviews of management of the aid target published in 2015 and 2017, and extends this analysis through to the end of 2019. It also draws on some insights from the NAO’s 2019 review on the effectiveness of UK ODA.

Box 1: Limitations of the methodology

Time restrictions: Data collection for this review took place during a time period disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the DFID-FCO merger. Both events affected the availability of UK government officials to engage with the review. ICAI made efforts to limit the amount of government engagement required, given the current external pressures, by relying as far as possible on desk research.

Scope: The analysis timeframe for this review is from 2013 to 2019. However, most of our primary data collection focused on the period from 2017 to 2019 to minimise burden on the government and to fit within the parameters of a rapid review. ICAI worked closely with the NAO to build on their findings on managing the target from 2013 to 2017, and reviewed secondary data to assess the broader context of our findings. We also made efforts to interview some officials who have been in post for a long time, or who were dealing with management of the target in earlier years.

Background and overview

The international ODA spending commitment

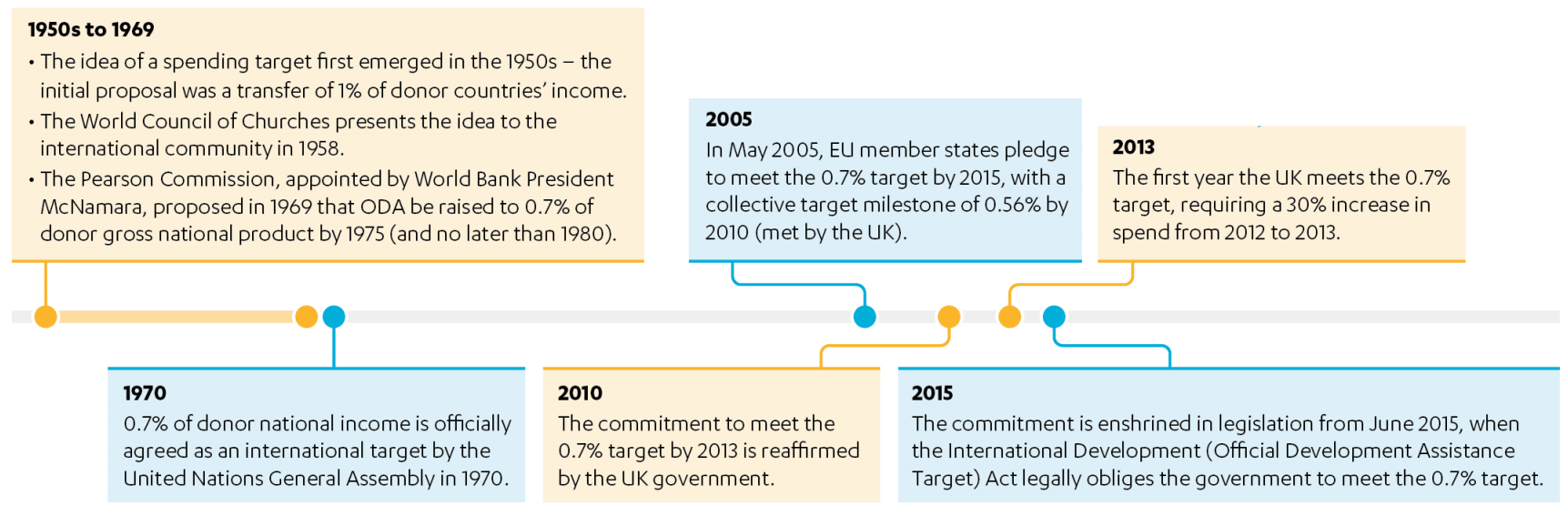

The 0.7% aid-spending target has a long history (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Timeline of the UK’s history of the 0.7% ODA spending target

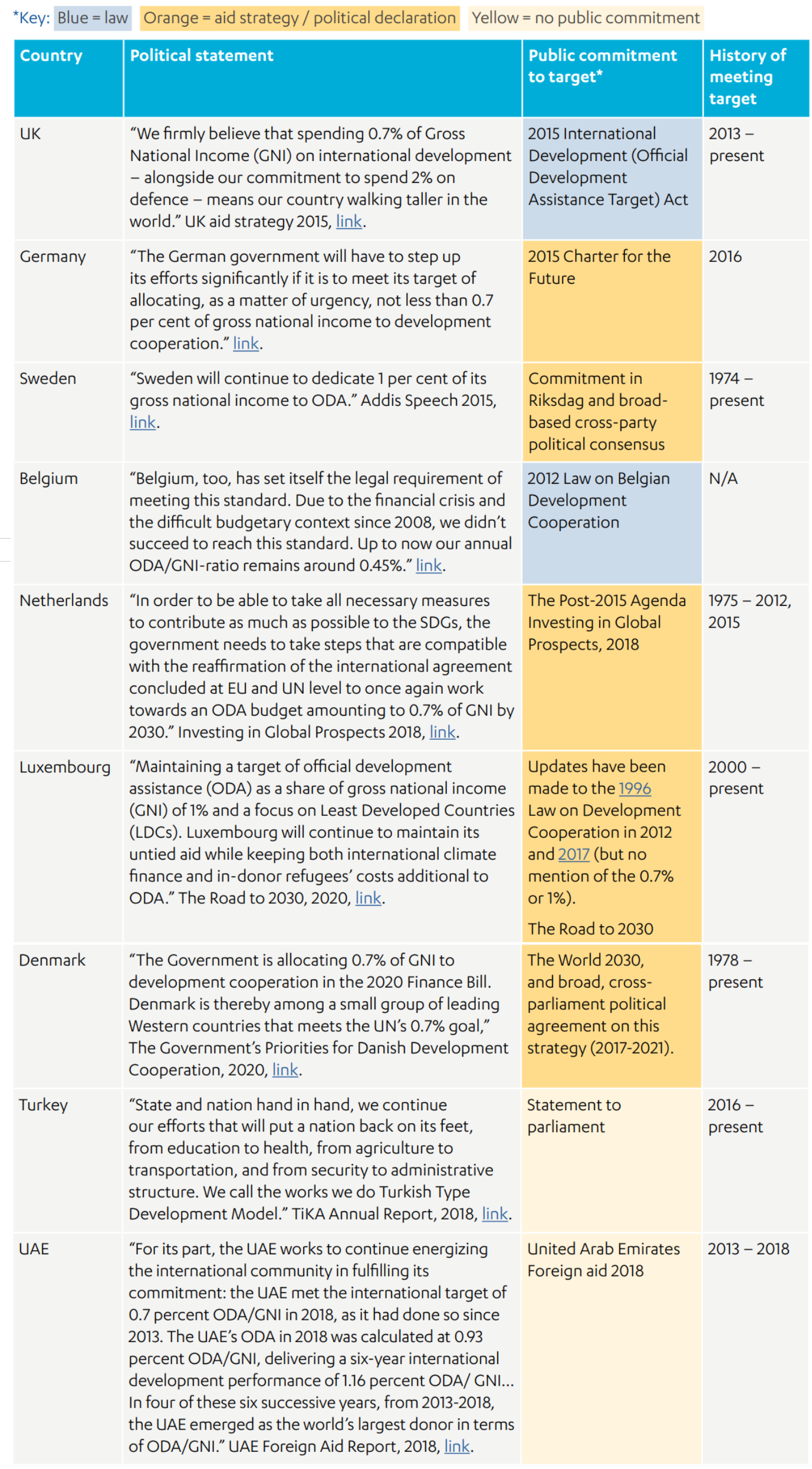

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC) is a coordination mechanism among traditional donors that sets standards and rules for reporting on aid. The first OECD DAC member country to reach the 0.7% target was Sweden in 1974, followed by the Netherlands in 1975, Norway in 1976 and Denmark in 1978. These countries (apart from the Netherlands) have consistently met or exceeded the target in the years since. In total, only eight OECD DAC countries have ever met the target and only five do so consistently. In 2018, across OECD DAC donors, the average aid budget stood at 0.3% of GNI. A number of non-DAC countries have also become important donors in recent years. Turkey has met the 0.7% ODA target since 2016 (in fact reaching 1.15% of GNI in 2019), the United Arab Emirates met the 0.7% ODA target between 2013 and 2018, and Saudi Arabia came close at 0.56% in 2019. Other countries, including China, India, Brazil and South Africa, have also increased their aid budgets, but do not currently apply the international ODA definition to their reporting.

The UK is one of only two countries to have passed national legislation mandating the target and is unique in consistently meeting, but not exceeding, the 0.7% target. The other country to enshrine the target in legislation is Belgium, which has not as yet met the target. Instead, Belgium uses the flexibility allowed by its legislation to provide an explanation to its parliament each year for why it has not hit the target.

Other donors that have consistently met the target have done so without any legal obligation; instead, they have set out their commitment in national aid strategies or announcements in parliament. Instead of mandating its target in law, Sweden passed a bill stating that ODA is to “amount to approximately one per cent” of national income. Each year, its parliament considers the government’s budget bill and sets the aid budget. In 2005, Sweden spent 1.4% while in 2019 it spent 0.99%. Denmark also routinely spends more than the 0.7% target but has not enshrined this in law. By instituting a new budgeting mechanism that allows it to meet the 0.7% commitment as an average over several years, Denmark allows for fluctuations in certain unpredictable areas of expenditure, such as in-donor refugee costs. Finally, Luxembourg’s target is not mandated in law but is reflected in the annual aid budget set each year by its parliament. The ODA:GNI ratio is allowed to fluctuate around this target. Between 2008 and 2019, Luxembourg spent, on average, 1% of GNI on ODA. However, it only hit 1% exactly on four occasions over those 12 years, spending slightly above, or even slightly below, its stated goal in the other eight. See Annex 3 for more detail.

The UK’s commitment to 0.7%

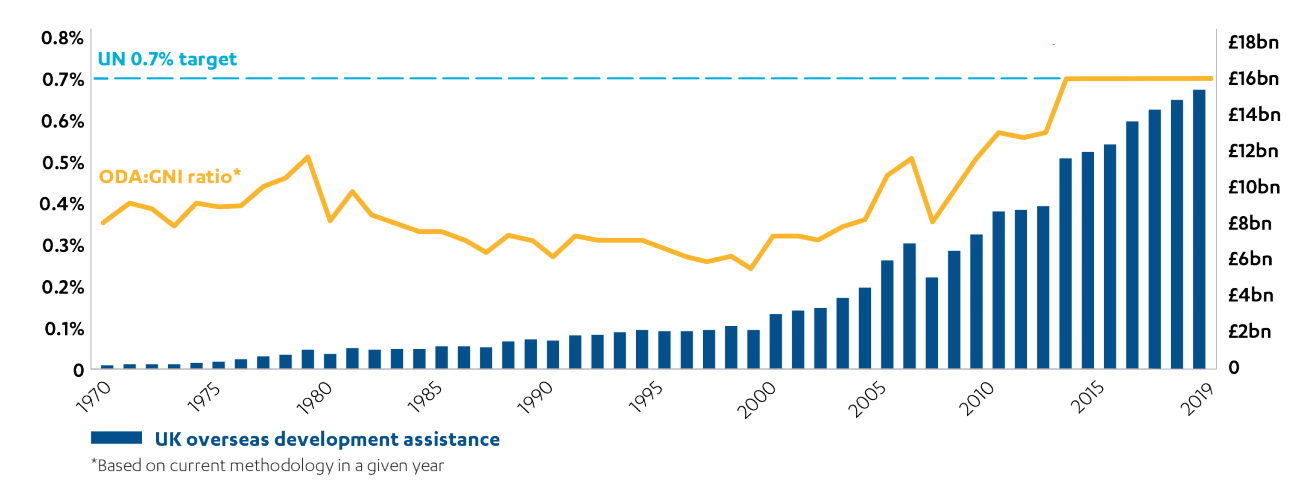

Figure 2: The UK’s official development assistance as a percentage of gross national income

Source: Statistics on international development: provisional UK aid spend 2019, 7 April 2020.

The UK first endorsed the 0.7% target in February 1974. However, it was not until the mid-2000s that a cross-party consensus emerged for a time-bound commitment, which solidified ahead of the 2005 election. In 2010, the Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government pledged to reach 0.7% by 2013, which was achieved (see Figure 2). The ODA target was enshrined in law in the 2015 International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Act.

Box 2: An overview of the UK legislation governing the 0.7% target

The International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Act 2015 states: “It is the duty of the Secretary of State to ensure that the target for official development assistance to amount to 0.7% of gross national income is met by the United Kingdom in the year 2015 and each subsequent calendar year.” If that target is not met in any given year, the secretary of state (the Act does not specify of which

department) must present an explanation to Parliament, based on economic or fiscal conditions in the UK or overseas, and state the steps that will be taken to make sure the target is met the following year. This flexibility has yet to be utilised by the UK government. The law also requires the secretary of state to make arrangements for the independent evaluation of the extent to which UK ODA represents value for money. ICAI is the means by which this commitment is met.

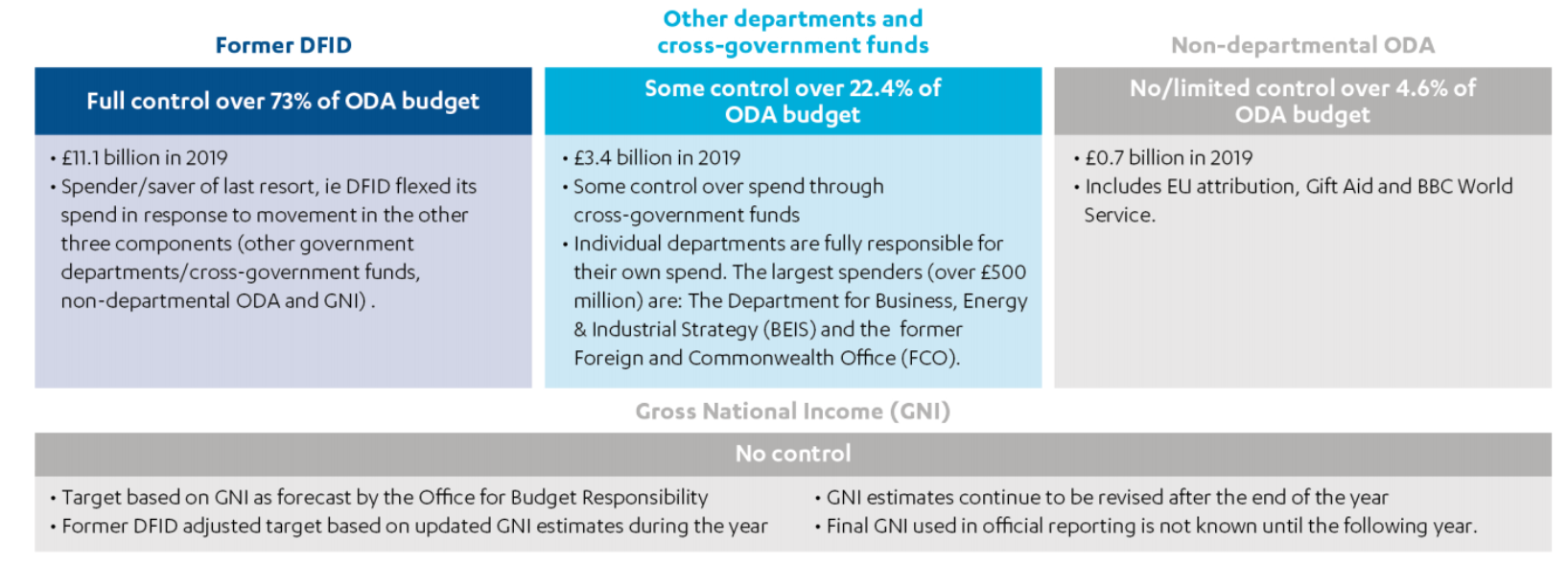

Since 2015, the architecture for managing UK aid has changed considerably, guided largely by the November 2015 aid strategy. This strategy signalled a ‘step change’ in the management of UK ODA, including a substantial increase in the number of ODA-spending government departments. Nearly three quarters (73.1%) of UK aid was spent by DFID in 2019.16 This complicates management of the spending target, which relates to the entire amount spent across the 18 ODA-spending departments and crossgovernment funds, as well as non-departmental ODA.

The target is calculated on a calendar year basis, in line with agreed processes for international aid statistics, while the UK government’s financial year runs from April to April. The commitment therefore requires the UK to manage expenditure across two time periods.

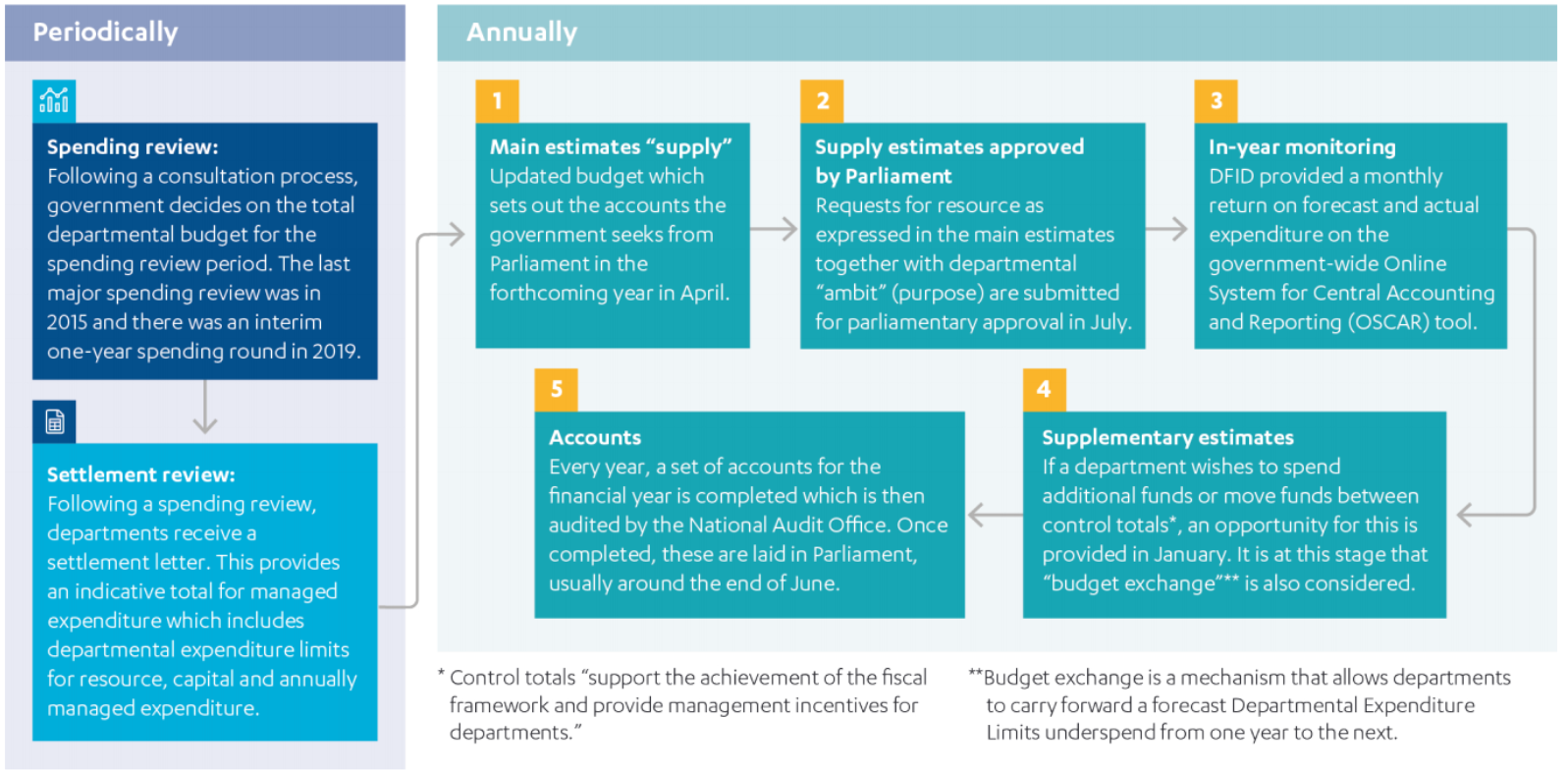

Box 3: How are UK aid budgets allocated and accounted for in order to meet the target?

Departmental budgets are allocated periodically through cross-government spending reviews, and include ringfenced ODA allocations. These are further specified by Parliament in the annual budget and in-year adjustments (known as Main and Supplementary Supply Estimates). In the 2015 spending review, ODA budgets equivalent to a total of 0.7% of forecast GNI were allocated across departments through a competitive process conducted by HM Treasury. Departments were asked to identify which elements of their current budgets could be classified as ODA as per the OECD definition, and to indicate where they would like to increase their ODA expenditure. A panel consisting of HM Treasury and DFID officials, as well as representatives of the Major Projects Authority (now the Infrastructure and Projects Authority), considered a total of 61 ODA bids with a combined value of £18 billion. See Annex 1 for a graphic that summarises this process.

HM Treasury then issued settlement letters to each department, confirming their overall budget and their ringfenced ODA allocations. Departments were also reminded of their obligations to ensure value for money in their aid spending, to support cross-government aid objectives and to provide timely and accurate reporting on their expenditure in order to assist with management of the spending target. In addition to reporting on their ODA expenditure across two time periods, departments are required to use two accounting methods. ODA spending is reported using cash accounting (where expenditure is recorded when the payment is made), while government accounts use the accrual method (where expenditure is recorded in the accounts when the transaction takes place, irrespective of whether cash has been paid).

Spending by government departments is classified as either ‘resource’, for day-to-day operations, or ‘capital’, for investments that add to the government’s stock of fixed assets. All government departments must comply with the rules and guidance set out in HM Treasury’s Managing public money guide. A share of DFID’s capital allocation was ringfenced for financial transactions, which included contributions to the UK’s development finance institution, CDC, and international financial institutions, including the Asian Development Bank and the International Bank for Development and Reconstruction (the lending arm of the World Bank Group).

Findings

How is the ODA spending target managed?

The spending target poses a complex set of financial management challenges for HM Treasury and aid-spending departments. Since the target was brought into legislation in 2015, a set of coordination arrangements has emerged, including an annual calendar of monitoring commissions requesting departments to provide their ODA spend forecasts to DFID and HM Treasury. Alongside processes specific to managing the target, DFID had in place a broader approach to value for money at the programme and portfolio level, assessed in a 2018 ICAI review. Other departments have their own approaches to value for money, which vary based on the type of ODA they spend and how long they have managed ODA programmes. In this section, we outline the processes as they have evolved. We then move on to our assessment of whether these arrangements gave rise to value for money risks over the period from 2013 to 2019, and whether these have been appropriately managed.

In-year monitoring and management

Overall responsibility for overseeing management of the target is entrusted to a Senior Officials Group (SOG), established in 2016 by HM Treasury and, until September 2020, co-chaired by DFID. The membership of the SOG also includes officials responsible for ODA spending from other departments. Its objectives are “to support departments to demonstrate that ODA spend meets high standards of value for money” and “to deliver a 0.7% GNI ratio by ensuring effective cross-government spending control.” The SOG leads a set of processes for monitoring how aid-spending departments are performing against their targets throughout the year.

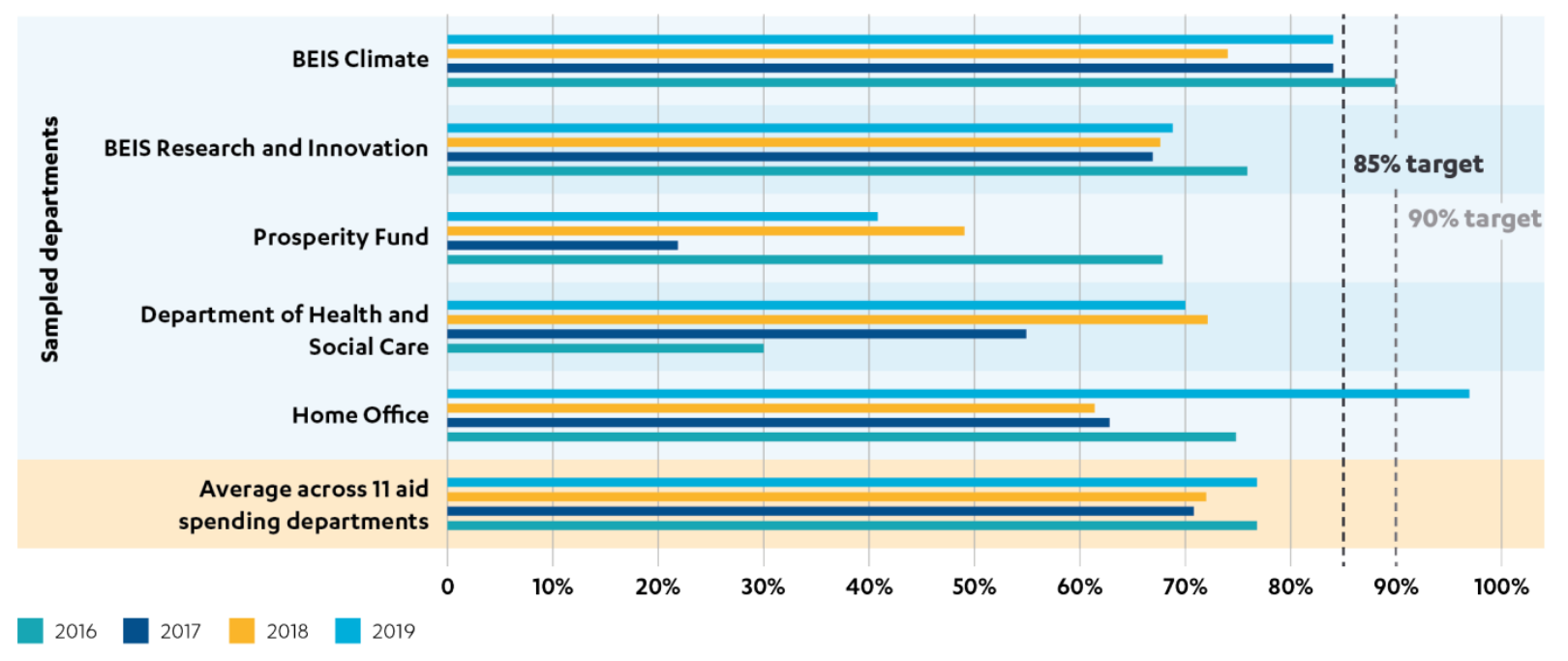

In 2015, HM Treasury specified that aid-spending departments must spend 90% of their financial year ODA allocations in the first three quarters of the financial year, to enable the calendar year target to be met. Following feedback from departments, HM Treasury reduced the target for departments other than DFID, first to 85% (for 2017-19) and then to 80% (for 2020). DFID’s target remained at 90%.

To manage delivery of the 0.7% target in the context of difficulties in forecasting aid expenditure and GNI, DFID was assigned the role of spender or saver of last resort in its 2015 settlement letter from HM Treasury. In this capacity, DFID obtained regular calendar year forecasts from other departments, to track aggregate expenditure against calendar year targets, and quarterly reporting on actual and forecast expenditure. Departments were asked to indicate their level of confidence in their forecasts using a red/amber/green (RAG) rating scale. Based on these forecasts, DFID then increased or reduced its spending to make up for changes to ODA spending in other departments to ensure that the 0.7% target was achieved.

In addition to monitoring its own and other departments’ ODA spending, DFID was required to track nondepartmental spend (that is, ODA-eligible expenditure that does not fall within any department’s budget). The largest items in this category in 2019 were the non-DFID element of the EU attribution (parts of which are ODA-eligible) and Gift Aid (tax rebates for charitable donations by UK taxpayers for international development), estimates of which are adjusted throughout the year and are difficult to predict.

DFID also kept a close eye on quarterly GNI outturn data produced by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), which is revised during the year as more economic data becomes available. The ODA:GNI ratio can only be calculated after calendar year end and is not finalised until autumn of the following year at the earliest. In 2019, a provisional ODA:GNI ratio was calculated based on a GNI estimate published by the ONS on 31 March 2020.

Year-end adjustments

The government uses several methods to adjust ODA expenditure towards the end of the calendar year, in response to the latest GNI estimates and differences between actual and forecast ODA expenditure during the year. One is to reallocate the ODA budget between departments in the final quarter, through Supplementary Estimates. HM Treasury requires departments to declare any expected underspend by September. It can then reallocate unused resources to other departments.

As the end of the calendar year approaches, the frequency of monitoring is increased. DFID’s practice was to compile actual and forecast expenditure figures from each department with a frequency that reflected the amount of spend remaining and the level of risk. To avoid any major last-minute changes, HM Treasury introduced a 15 December cut-off date for most ODA expenditure (departments must seek approval for any expenditure between 15 and 31 December).

Figure 3: Process map showing cross-government coordination to hit the 0.7% target

After 15 December, DFID then adjusted its own expenditure to ensure the target was hit (reported within two decimal places, as required for international aid statistics). In 2019 this rounding afforded a margin of error of approximately £100 million (in either direction) – a challenge which is particularly resource-intensive to meet. To do this, it relied principally on rescheduling multilateral contributions agreed in promissory notes to fall either side of 31 December.

Box 4: What are promissory notes?

The amount and timing of multilateral contributions are set out in promissory notes (legally binding commitments to pay), which are issued in favour of the multilateral partner and lodged with the Bank of England. A promissory note counts as ODA expenditure at the time it is issued, even though the funds are not transferred until later, according to an ‘encashment schedule’ agreed with the multilateral organisation. This is particularly useful for multilateral development banks, which are not permitted to agree new loans to developing countries until they have secured the funds from donors, but typically pay out the loans in instalments over several years. Promissory notes provide them with the liquidity to continue their operations. At any given time, the UK has around £5 billion in outstanding ODA promissory notes. We discuss the implications of this below in paragraph 3.54.

Relevance: How well is the process governed and managed?

The Senior Officials Group has become an effective cross-government structure for managing the target

The complexity of hitting an aggregate aid target across a large number of government departments calls for robust governance structures and clear coordination. The SOG brings together the responsible officials from across government, enabling efficient communication on the challenges and how to respond to them. The SOG has become an effective mechanism for sharing information about expenditure forecasts and other variables, as well as updating on progress towards the target at various points in the year.

HM Treasury has used the SOG meetings to challenge departments to improve their performance against spending targets, while DFID provided guidance on forecasting of expenditure, to minimise crowding of expenditure towards the year end. At times, tensions have arisen between the need to impose top-down discipline and allowing departments enough space to raise concerns about their own spending profiles. Nevertheless, DFID noted it had developed good working-level relationships with other departments, and the departments we interviewed found the SOG to be an effective, though sometimes formulaic, forum (given the regular revisiting of a set action plan).

Meetings closer to the end of the calendar year have been judged to be most useful, particularly by DFID and HM Treasury, as the evolving picture of progress towards the spending target becomes clearer. A meeting is generally held in September to allow HM Treasury time to challenge departments on their forecasts and to reallocate ODA as needed. Meetings in the final quarter of the calendar year are particularly important, especially in years with higher-than-usual levels of uncertainty. In 2019, for example, DFID used the November SOG to address the implications of a lower-than-expected GNI target and the risks of disruption to aid spending caused by the 12 December general election.

The SOG has a wider remit beyond managing the ODA spending target, including supporting HM Treasury’s efforts to improve cross-government coherence and effectiveness, and reporting periodically to the ODA Ministerial Board, which is the highest-level coordination structure for UK aid. As part of this effort, in 2018 HM Treasury developed a framework for monitoring the alignment of UK aid against the 2015 aid strategy, but this remains unpublished. At least one department noted that, as time spent in SOG meetings on broader ODA coherence issues increases, it would be useful to convene additional technical discussions focused solely on the target. For this reason, a ‘junior officials group’ was convened in advance of a SOG meeting in 2020 to allow for more detailed technical discussion.

DFID successfully fulfilled the main responsibilities and carried the risk associated with the spending target

4 Between 2017 and 2019, DFID tracked cross-government ODA expenditure on a near-monthly basis, presenting the information to its Management Board. The level of detail increased as the calendar year end approached, and was sufficiently granular to allow DFID to monitor, track and respond to any potential value for money risks, particularly those related to its own role as spender or saver of last resort. Any issues were raised in quarterly Investment Committee meetings.

It is notable, however, that DFID had no overall responsibility for ensuring the value for money of aid spent by other departments, and only had full control over its own spending through cross-government funds (see Figure 4). Its Investment Committee was responsible for providing assurance to DFID’s permanent secretary, as accounting officer, that the department’s own portfolio represented value for money. However, HM Treasury rules stipulate that each department is responsible for the quality of its own expenditure. DFID was, however, mindful of potential reputational risks for UK aid, including not meeting the target, and sought to coordinate across departments where possible.

Figure 4: Overview of DFID’s level of control over the main components of ODA spend

Source: Adapted from internal presentations used by DFID in 2018 and 2019.

Other departments vary in the quality of their governance arrangements for aid spending, but they have improved over time

Of the departments and cross-government funds that we sampled for this review, we found that each had worked to put in place or improve governance structures for their aid spending. We were able to confirm that the progress “towards increasing capacity and capability” identified by the NAO in 2017 has continued. These structures include a capacity to monitor aid spending throughout the year and to highlight any emerging challenges in meeting spending targets. The sophistication of departments’ financial management systems varies, generally (but not always) in proportion to the importance of ODA within each department’s overall budget. Some departments invite HM Treasury representatives to their internal ODA financial oversight meetings, for additional support. However, there is substantial variation in practice across ODA-spending departments, which leads to varying levels of overseeing how spending targets are managed.

Does the spending target affect how UK aid is allocated?

The ODA target can create pressure to push the boundaries of what counts as aid

Over the spending review period, DFID provided guidance to other departments on what counted as ODA, defined by the OECD DAC as “government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries.” In 2018, the Institute for Fiscal Studies expressed the view that “meeting the annual target with no margin to spare creates a disincentive for the Secretary of State to halt or reclassify aid [as non-ODA], as this can risk undershooting the target.” Similarly, in June 2020, in interim findings from an enquiry on the effectiveness of UK aid, the International Development Committee noted that “there is a significant risk that non-DFID government departments will rebadge day-to-day spending as aid and push the boundaries of what counts as aid.” We have seen evidence from internal documents that this concern is shared by at least one government department, agreeing with the NAO’s point in its 2019 report that ODA targets might have a distorting impact on spending choices for some departments, particularly in the context of tighter overall budgets.

While we agree that these are serious concerns that need careful monitoring, we did not come across any instances of expenditure being inappropriately classified as ODA in this review. We have, however, raised concerns around ODA re-classification in other reviews, particularly in respect of some research expenditure in the Newton Fund.

Concerns that the spending target encourages a greater focus on inputs than on results are partially mitigated by the scale of international poverty reduction needs.

In an interview, a senior DFID official acknowledged a common perception that input-based spending targets are unhelpful (that is, judging an aid programme by how much it spends, rather than what it achieves). This perception was confirmed in our focus group discussion with non-government stakeholders, expressed in several different ways. It was noted that spending targets encourage a focus on inputs rather than outputs/outcomes, that relating aid levels to UK GNI rather than global need is inappropriate, and that the impression of the UK government “shovelling money out the door” to meet the target undermines the legitimacy of UK aid, even if this is not true. HM Treasury, however, made the observation that departments would always aim to spend their budget allocations fully, even if there were no overall 0.7% spending target.

Both HM Treasury and DFID officials made the point to ICAI that global poverty reduction needs far outstrip current international aid flows, a point also documented by external sources. This means there is no shortage of worthwhile development projects, and no reason to believe that an increase in aid necessarily leads to a reduction in its quality, even at the margins, provided that each aid-spending department has adequate capacity to manage its own resources. The section below explores the methods the UK government employs to ensure programming decisions related to the target represent good value for money.

Conclusion on relevance

The UK government has developed several layers of governance that have ensured that the 0.7% target has been hit each year since 2013. The coordination has become increasingly effective over this period, which enabled DFID to play its role as spender or saver of last resort successfully. Other ODA-spending departments have strengthened their own oversight of the target, although their processes are generally less sophisticated than DFID’s. While the target has provided some perverse incentives for ODA allocations, stronger governance and better management over time have reduced value for money risks.

Efficiency: What are the value for money risks associated with meeting the spending target, and how well do the responsible departments mitigate them?

Management of DFID’s ODA expenditure

Alongside its value for money assurance framework, DFID developed a well-articulated set of financial management and risk mitigation procedures for meeting the spending target

Over a period of several years, DFID refined its value for money guidance and operational practices to establish value for money as an overriding consideration for the department at all levels of its work and all stages of the project cycle. DFID’s approach to value for money was reviewed by ICAI in February 2018. In 2017, the Investment Committee reviewed DFID’s Value for Money Agenda for Action and plans

to drive value for money during the implementation of the 2015 spending review. In 2018, DFID sought improvements in portfolio-level value for money management and in 2019 endorsed the proposal for a strategy refresh.

Since the introduction of the target, DFID adapted its financial management practices to provide the flexibility needed not only to manage changes to spending plans that arose within its own portfolio, but also to adjust its spending and play the role of spender or saver of last resort. It had a range of techniques for accomplishing this, including:

- processes for pipeline and portfolio management, including over-programming

- close monitoring of actual and forecast ODA expenditure

- in-year tracking of GNI estimates

- profiling expenditure towards calendar year end, giving flexibility to reschedule between years.

Each of these practices is explored in turn below.

Dynamic portfolio management helped DFID meet the 0.7% target

DFID’s Investment Committee monitored the department’s portfolio and, as evidenced in meeting minutes, raised concerns whenever programming levels needed to be adjusted to hit the target. Having a strong pipeline of programmes in design and awaiting approval gave ministers a range of fully designed and appraised programmes to bring forward if needed, avoiding the need to make poor allocative choices.

DFID’s Management Board recognised that delays in approving programmes during the year could result in unhelpful pressure to spend money quickly before the end of the calendar year. It routinely tracked approved programmes and those in the pipeline awaiting approval, and made sure that approvals were given in a timely way. The figures show an improving trend in the timeliness of project approvals over the years. By May 2017, only 65% of DFID’s 2017-18 resource budget scheduled to be spent between April to December had been approved, which was considered a risk. In May 2018 the approved programme rate had risen to 73%, and in May 2019 it stood at a healthier 77%.

To provide flexibility to adjust expenditure towards the end of the year, DFID routinely over-programmed its budget (that is, it maintained a stock of approved programmes in excess of its annual budget, which could be launched ahead of schedule in the event of underspend). If the department needed to accelerate spending, senior management would proportionately increase the level of over-programming and step up oversight of expenditure. This finding builds on the NAO’s conclusion that DFID had improved the management of its own budget since 2013, smoothed its spending profile by distributing spend more evenly across the year, and created an annual pipeline of projects that exceeded budgets, creating more scope to apply value for money considerations in its spending choices.

The unpredictability of GNI estimates and non-departmental ODA presented substantial challenges

As outlined above, DFID tracked GNI estimates in order to adjust expenditure in a timely way. GNI variability at times presented a substantial challenge. HM Treasury indicated that it allocated additional funds to DFID in 2018 to deal with a GNI rise over 2018 and 2019. A transfer of £230 million from HM Treasury to DFID is recorded in the 2018-19 Supplementary Estimates.

The largest item of non-departmental ODA, the EU attribution (non-DFID), has been especially difficult to predict. Estimates depend on the EU’s ability to forecast its own ODA spend, as well as exchange rates and the imputed UK share of the EU’s budget (which depends upon the size of UK GNI relative to other EU member states). EU attribution estimates vary considerably year to year and can change after year end. They were particularly volatile in 2017, when estimates fell by £90 million between May and December. Estimates in 2018 and 2019 were more accurate. The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, another example of non-departmental ODA, was also identified as particularly volatile, with in-year forecasts varying by £329 million.

Although this volatility adds to the uncertainty in ODA spending plans, DFID was able to factor the changes into its overall management of the target. Fluctuations were tracked on a regular basis by the Management Board and considered, when necessary, by the Investment Committee.

Sudden-onset humanitarian crises were effectively managed through the UK’s cross-government ‘crisis reserve’ fund and DFID’s contingency resources for unforeseen events

Another type of uncertainty in meeting the target is related to the rapid onset of humanitarian crises. The ODA crisis reserve fund of £500 million, announced in the 2015 UK aid strategy and managed by DFID, was designed to enable quick and flexible response to humanitarian crises. It was accessible to any ODA-spending department. It consisted of a £200 million cash reserve (held centrally by DFID) and a £300 million re-deployable reserve (allocated programme funds that could be redirected to respond to a crisis if needed). The crisis reserve allowed DFID to quickly commit over £22 million of UK aid (as of March 2019) in response to Cyclone Idai, which affected 3 million people in Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe. DFID further responded to unforeseen humanitarian events by making a significant contribution to the UN’s Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) at the end of 2019 (further explained in paragraph 3.52).

DFID’s financial arrangements allowed it to absorb significant changes to payment schedules without adversely affecting its programming

One of the concerns identified by the NAO in its 2015 report was the concentration in DFID expenditure towards the end of the calendar year, which it recommended that the department reduce. DFID’s view was that the concentration of spend related to the timing of multilateral payments, and was a conscious strategy enabling it to adjust their timing around year end, in order to play the role of spender or saver of last resort.

Several external commentators argued that uneven spending profiles (such as a concentration of spend at year end) introduce value for money risk, which would be mitigated by smoothing spend across the year. This would most likely be the case if non-governmental organisation (NGO) or commercial suppliers of bilateral programmes were forced to reschedule their expenditure according to DFID’s spending calendar, or if rescheduled payments were made “in advance of need”, contrary to HM Treasury rules.

While we have seen evidence from 2017 that DFID’s Management Board considered options for rescheduling bilateral programme spend (including to CDC and multiple low-value transactions), adjustments to spending made by DFID have more typically involved rescheduling multilateral promissory note payments. We find that this has not compromised value for money. We return to the rescheduling of multilateral payments in paragraph 3.52 below.

Managing the ODA target created administrative costs for DFID

While managing annual spending limits is routine for government departments, hitting the ODA target is unusually onerous. It involves coordinating across more than 18 departments and cross-government funds (even though their ODA spending is often small in relation to the total), meeting parallel reporting conventions set by the OECD DAC, which continue to evolve, managing two different reporting years

and using two accounting conventions.

Within DFID, managing the 0.7% target was a department-wide activity. As the calendar year end approached, it involved senior finance and policy department officials in an intense schedule of activities, and coordinating with multilateral organisations and suppliers. There is no question that this was resource-intensive for DFID, with high opportunity cost. Any measures that simplified the demands would have the effect of freeing up resources for providing high-quality development assistance.

While DFID worked hard to manage the risks, the 90% financial year target resulted in an uneven pattern of spending over the year and potential value for money risks

As noted above, HM Treasury’s allocations assumed DFID would spend 90% of its budget in the first three quarters of the financial year (April to December), but that this would be flexibly adjusted in-year as necessary by DFID to meet 0.7% as spender or saver of last resort. This obligation was passed on to all DFID directorates, with the exception of the Corporate Performance Group. This obligation was challenging for DFID in the early part of our review period, when its budget was expanding rapidly to meet the target in 2013, but became embedded practice from 2015. DFID staff acknowledged that it created potential value for money risks for bilateral programming, but these were mitigated by allowing underspend in some directorates to be offset by overspend in others, smoothing expenditure across the department.

In April 2019, DFID faced the prospect of having to spend 94% of its 2019-20 budget in the first three quarters, to make up a shortfall of £458 million in forecast spend by non-DFID departments (significantly above the £28 million to £219 million forecast underspend at the same time in previous years). In June 2019, DFID confronted a worst-case scenario of having to make up a possible £1.3 billion forecast shortfall against the target resulting from further slippage by non-DFID departments, reduction in non-departmental ODA, and GNI growth that would have required DFID to spend 103% of its 2019-20 budget in the first three quarters. DFID managed this by bringing forward the approval and design of new programmes and by asking non-DFID departments to ensure all ODA-eligible spend was included in their forecasts. HM Treasury instructed departments to transfer unspent ODA allocations to DFID, and provided DFID with additional budget for 2019-20 which helped manage down its Q1-3 pressure. There is no doubt that value for money risks are heightened when large in-year budget changes are required. The system functions well in respect of ‘normal’ levels of variability but comes under pressure when the UK economy and aid programme are subject to significant external shocks.

Variability in expenditure caused disruptions to DFID’s supply chain, of which it was not always aware

Spending 90% in the first three quarters of the financial year can pose value for money risks when combined with other factors that delay the approval of new programmes, such as elections and ministerial changes. These factors can lead to lower-than-expected levels of approved programming and pressure to rush expenditure.

We found some evidence that this adversely affected DFID’s suppliers. In our focus group discussion, one supply partner noted that having end-of-year spending pressures heightens risks for international NGOs operating in fragile contexts, where programming is in any case vulnerable to disruption. Rushed expenditure in such environments could compromise the quality of programming. Another supplier noted that, depending on the activity invoiced for (for example, the early scheduling of a conference event), this could affect value for money, though was unlikely to have a material impact on results. In written submissions, two suppliers noted they had been asked on a few occasions to time an invoice for either December or January to help meet the 0.7% target, but that this did not have a significant impact on programming.

DFID did not have a process for monitoring the impact of its spending targets on suppliers and may therefore have been unaware of effects felt in its supply chains. However, in 2018, it introduced a strategic relationship management programme covering 42 strategic supply partners from the private sector and civil society and 80% of the department’s contract and grant spending. This provided supply partnerswith an opportunity to raise concerns and enabled DFID to monitor their financial health and stability.

ODA management by other departments

Non-DFID departments initially lacked the systems required for managing value for money risks

In its 2017 report, the NAO noted that the allocation of resources to new ODA-spending departments after 2015 introduced significant value for money risk because these departments lacked the systems and skills required to develop and manage programmes. The departments we covered in this review acknowledged that they faced challenges early in the 2015 spending review period, and that some of these continue. The Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) noted the added risk, for those not familiar with managing ODA, of managing calendar year (cash accounting) and financial year (accruals accounting) systems and procedures in parallel. ICAI observed in 2019 that in allocating money to Newton Fund delivery partners, BEIS Research & Innovation (R&I), which manages the Fund, had not developed sufficient value for money assurance processes. ICAI’s 2018-19 follow-up review noted that progress on value for money had been made. The Prosperity Fund regarded the spend profile it was set in 2015 as overambitious, and despite a budget reduction and term extension (decided by HM Treasury following a recommendation made in ICAI’s 2017 review of the Prosperity Fund), it continues to underspend its ODA calendar year target, choosing, in its own words, to prioritise quality over rapid scale-up of programming.

To accommodate rising ODA budgets, other departments sought to adopt some of DFID’s financial management practices, with varying degrees of success

The 2015 spending review underestimated the time it would take new ODA-spending departments to build a full portfolio and pipeline of ODA programmes. Five years on, not all of them have reached a position where they can over-programme in order to meet their targets.

Before 2015, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) managed a small amount of ODAeligible spend but no large development programmes. The ODA spending profile allocated to it in the 2015 spending review was unrealistic, failing to take account of the lead time required to develop and implement new programmes. As a consequence, DHSC underspent against its calendar year allocation each year until 2019. DHSC was aware of the risks this posed to the overall spending target, and communicated this regularly to HM Treasury and DFID, including at the SOG. For the Prosperity Fund, being in a position to support DFID to invest £28.5 million in The Currency Exchange Fund (TCX) programme in March 2019 helped boost overall UK ODA spend, at a time when only 15 of its portfolio of 27 programmes were under implementation. With all 27 programmes now under way, the Prosperity Fund actively manages its overall expenditure, including through over-programming. Because of the nature of their portfolios, BEIS Climate and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) have the option to reschedule multilateral payments at calendar year end (the main method used by DFID to meet the target).

One official noted that non-DFID departments do not have the licence, which HM Treasury allowed DFID, to commit up to 60% of their budget beyond the spending review period. Without this, departments could be prevented from developing multi-year programmes and might have to close effective programmes early, which could pose value for money risks.

Departments have struggled with forecasting their ODA spending

In its 2017 report, the NAO identified concerns about the accuracy of forecasting by ODA-spending departments, noting that only two of the 11 bodies reviewed were able in August 2016 to forecast within 10% accuracy what their spending would be in the final quarter of 2016. Volatility in non-DFID forecasts between August and December has continued, with two departments and one fund showing less accuracy in 2019 than in the previous two years.

These forecasting challenges can reflect different kinds of aid expenditure. For example, support provided by the Home Office for asylum seekers in their first year in the UK counts as ODA and fluctuates depending on the number of arrivals during the year.

Several departments, including the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), BEIS, the Home Office and the Prosperity Fund, also acknowledged that ‘optimism bias’ (where departments and funds overestimate their spend in their forecasts) played a role in inaccurate forecasting.

The 90% financial year target set by HM Treasury was not sufficiently tailored to reflect different departmental programme portfolios

Within the SOG, BEIS, the FCO and the Home Office have all noted that the nature of their ODA budgets gives them little flexibility to manage their spending target. BEIS R&I noted that research spending, which constitutes a large share of its ODA budget, takes the form of monthly salary payments that cannot be brought forward. Similarly, the demand-led nature of the Home Office’s support for asylum seekers explains its inability to meet in-year spending targets.

HM Treasury has noted that the consequence for departments unable to meet the 85% target may be reallocation of their aid budgets in-year to other departments. While HM Treasury opted not to revisit the 2015 spending review settlements in light of the challenges that were encountered, it noted that performance and capacity would be a consideration in the forthcoming spending review.

Concentration of expenditure at year end remains a significant problem

Because departments have struggled to meet in-year spending targets set by HM Treasury, too much ODA expenditure is still concentrated towards the end of the calendar year. In 2016, almost half of nonDFID departmental ODA was spent in the last quarter. This has reduced slightly, but has remained fairly stable over the past three years, at 40% in 2017, 39% in 2018 and 38% in 2019. In practice, given the rising aid budget, this means that the amount of ODA spent in December has increased, from £760 million in 2017 to £1,086 million in 2019.

This suggests that too much ODA is at risk of being rushed at year end, and the chance of slippage against the target is heightened. Rushed expenditure poses a significant value for money risk. One written submission that we received claimed that there is “panic” in one ODA-spending department between September and December, and that this leads to a risk of reporting financial transactions in ways that contravene good financial management practice, or funding decisions that are not in line with the “spirit” of ODA. The NAO identified this as a potential risk as early as 2015.

Other value for money risks

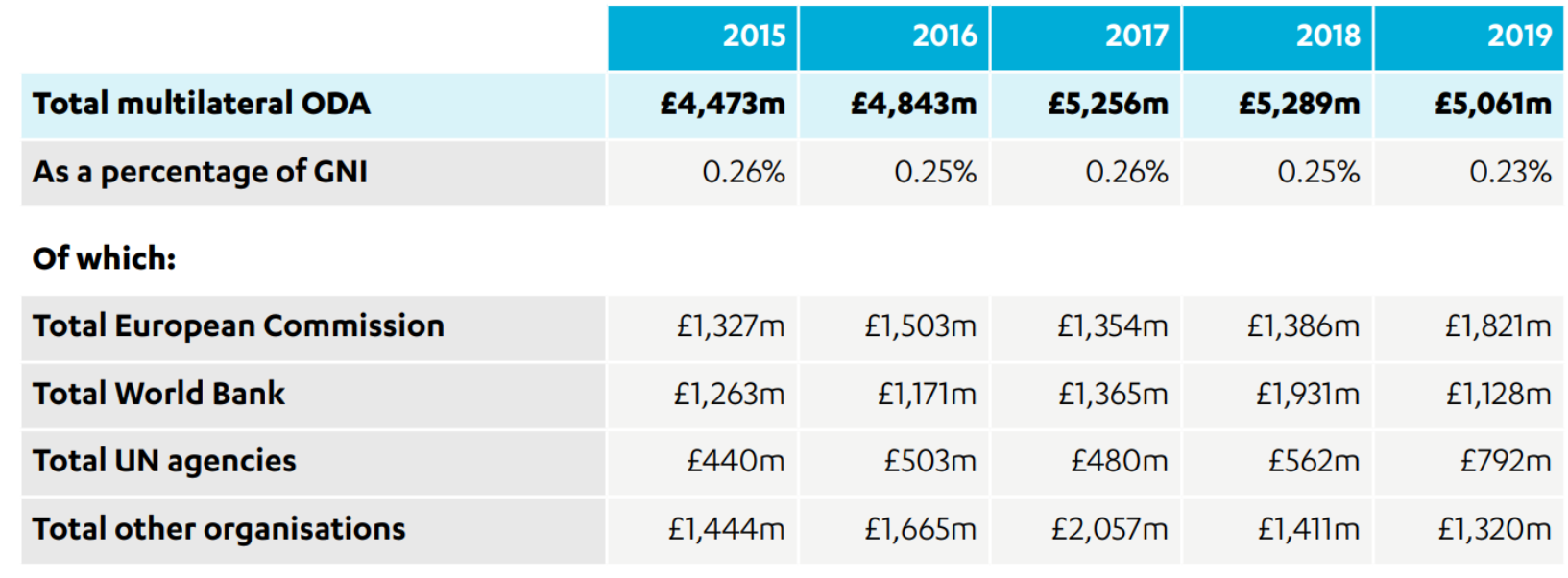

There is no evidence that rescheduling multilateral contributions across calendar years compromises value for money

Multilateral contributions are an important part of UK aid programming, accounting for around 40% of the total. The flexibility to move payments between calendar years has also been crucial to DFID’s ability to act as spender or saver of last resort. By October each year, DFID had assessed its options for rescheduling payments. For example, in 2018, it brought forward a World Bank International Development Association (IDA) payment of £629 million, in part to offset a £700 million reduction in the UK’s expected contribution to the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust. In 2019, DFID was able to adjust its contribution to the UN’s CERF – a multilateral fund set up at the request of the UK to ensure the availability of funding for UN relief programmes as needed and, as such, an example of good value for money. Shifting around payments of this size in turn creates risks to meeting the following year’s spending target. In May 2019, DFID flagged at a SOG meeting that it would be “impossible” to spend 94% of its financial year budget in the first three quarters, as the multilateral replenishments that occurred in 2019 were smaller than in previous years. See Annex 1 for more detail on variations in multilateral spend between 2015 and 2019.

The UK is the largest contributor to IDA, providing 12% of the 2020-23 replenishment (IDA19). The UK’s large and early contribution enables the World Bank to begin committing IDA funds, and also to manage a large and flexible trust fund portfolio. The World Bank confirmed to us that it does not consider the rescheduling of the UK’s IDA payments to be a concern, citing a recent agreement on a slight adjustment to the UK’s IDA19 payment schedule. Given the rules governing its finances, small variations in the timing of payments do not affect its capacity to utilise the funds.

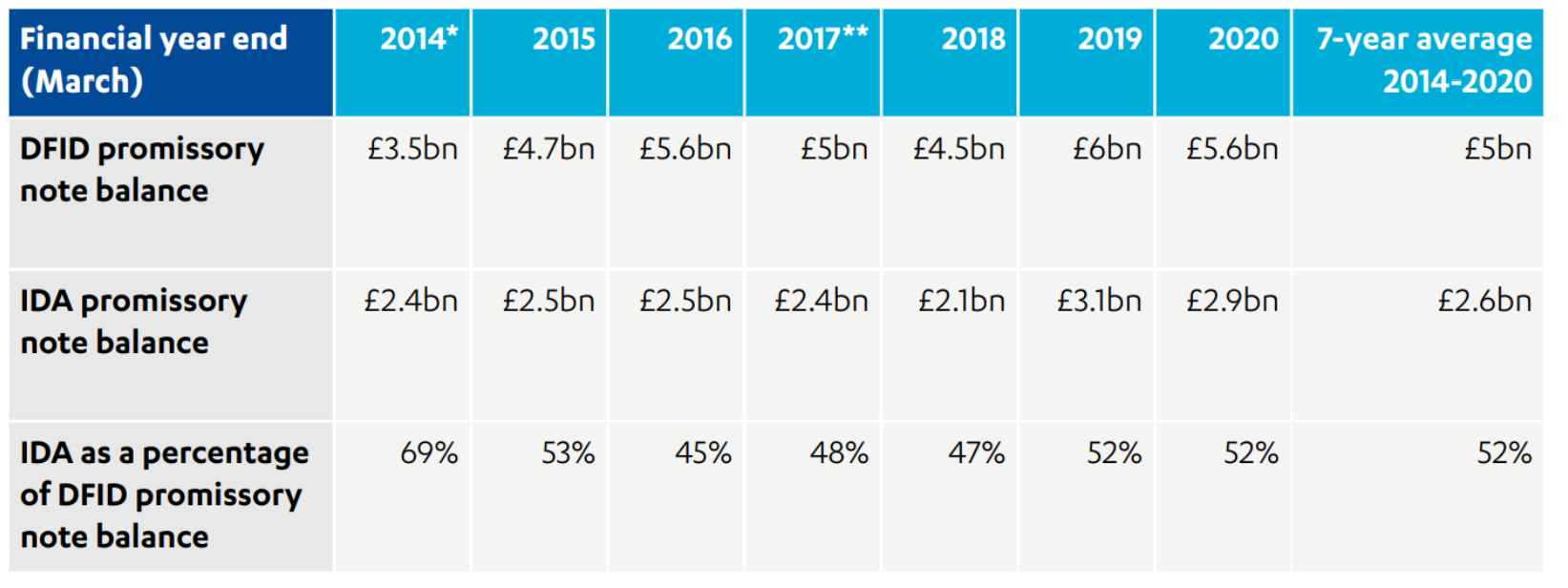

The NAO observes in its 2017 report that promissory note commitments are typically not paid out for two years or more, noting that “the continued growth in the balance of outstanding promissory notes could undermine the credibility of the ODA target.” It is true that the balance of uncashed promissory notes recorded each year at the end of March has risen from £3.5 billion in 2014 to a high of £6 billion in 2019. However, the growth anticipated by the NAO in December 2016, when the balance of uncashed promissory notes was £8.7 billion, did not materialise. Uncashed promissory note balances between 2014 and 2020 averaged £5 billion, of which half is owed to the World Bank (see Table 4 in Annex 1). When the nature of the World Bank’s business model is taken into account, we do not see this as compromising value for money. In practice, the existence of promissory notes enables the Bank to extend loans to developing countries, against the security provided by the UK. In that sense, the funds are not idle.

The UK will need to revisit its multilateral funding strategy after the end of the transition period of its exit from the EU.

In a September 2019 report, the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee noted that “[if] the UK leaves the EU without a deal, a significant risk to value for money is created as the government might need to identify, quickly, alternative ways to spend the money if it is still to meet the 0.7% target.” The NAO also noted that a quick redistribution of such a large amount of ODA (currently around £1.8 billion per year) would create a risk to value for money. DFID indicated to the Public Accounts Committee that it would be prepared for all scenarios, including by maintaining sufficient links with EU institutions to be able to work with them after the UK’s exit from the EU is finalised. With the UK funding to the EU’s international development budget likely to reduce gradually from 2020 onwards due to the UK’s exit from the EU, it is likely that the government will need to revisit its multilateral funding strategy, also in light of changes in GNI from 2020 as a result of COVID-19.

Special rules for DFID’s capital budget may have introduced value for money risks

In 2015, HM Treasury set DFID a ‘financial transactions’ target of £5 billion across the spending review period. Financial transactions include loans, equity investments and certain contributions to the multilateral development banks. This placed pressure on DFID to identify suitable financial transactions, with relatively few options available at that stage.

In 2017-18, the loan portion of the UK’s contribution to the World Bank IDA accounted for most of the target, with contributions to CDC taking over from 2018-19 onwards. In financial year 2019-20, approximately 28% (£3 billion) of DFID’s £10.8 billion annual budget was capital, and within that £1.03 billion was for financial transactions. In its 2016-17 session, the International Development Committee recommended that DFID’s financial transactions target be relaxed, to avoid the department being forced to “spend large amounts of money through a small number of channels”. DFID disagreed, maintaining that the target was appropriate. Parliament passed legislation in 2017 allowing DFID to recapitalise CDC. ICAI recommended in 2019 that DFID’s business cases for future capital commitments to CDC should be based on stronger evidence of achieved development impact and clear progress on expanding their in-country presence. With the CDC recapitalisation programme set to complete in 2021, the FCDO is now being encouraged to identify new financial transaction options.

ODA ‘reflows’ or repayments have become less of an issue

Where capital ODA expenditure generates income, in the form of loan repayments or returns on investment, that income is an ODA ‘reflow’ (also referred to as ‘negative ODA’). Under OECD DAC rules, reflows are subtracted from annual aid figures in the calculation of net ODA – the basis of the 0.7% target. ODA reflows also occur when unspent contributions to multilateral instruments (such as trust funds) are returned. This further complicates the management of the ODA target.

A 2015 change to the way DFID recorded capital reflows reduced the amount of reflows in the department’s accounts. Before 2015, CDC’s equity investments were scored as UK ODA using a net reflow method, resulting in negative amounts in some years. Following a consultation in 2014-15, it was decided to report the government capital contributions to CDC as ODA at the time they were paid to the institution. Discussions within the OECD DAC about the reporting of ODA through private sector instruments is ongoing (see paragraph 3.61).

The UK’s International Climate Finance (ICF) has the potential to generate some reflows, though to date only a small number of cases have arisen. BEIS anticipates that this will increase in the coming years as older programmes reach their pre-agreed closing date and as investments mature and begin to generate returns. Mitigating actions may be needed, on a case-by-case basis. In 2019, for example, the Green Africa Power company (a joint BEIS/DFID ICF investment made under the multilateral Private Infrastructure Development Group) was liquidated, resulting in the return of £8 million in cash and the cancelling of a promissory note liability of £15 million. DFID then had to offset this partially with an increase in its own ODA expenditure.

Changes to the international ODA definition introduce some uncertainty into the spending target

The international ODA definition and reporting rules are agreed by OECD DAC member countries. Between 2016 and 2018, several changes were introduced, relating to in-donor refugee costs, investments in peace and security, and methods for reporting loans and development capital. The possibility of rule changes injects some uncertainty into ODA spending forecasts. So far, according to DFID officials, in-year changes have not had a material impact on the spending target. However, the Home Office noted that in 2018 a proportion of its support to asylum seekers was ruled ineligible, which posed a challenge in meeting its own spending target. There are ongoing discussions on changes to the reporting rules for private sector instruments. In 2017, it appears that the UK advocated for changes in the rules that would enable it to maximise the amount of ODA reported in respect of its CDC contributions and other financial transactions.

In 2015, the OECD DAC agreed a change to the rules for reporting ODA official loans, whereby only the ‘grant equivalent’ component (a measure of the level of concessionality) is reported. This change was phased in between 2016 and 2018, and DFID was therefore able to anticipate this change in its planning. According to a technical note prepared by the department,60 had the ‘grant equivalent’ method been applied to 2017 spend, ODA would have been about £750 million (5.4%) lower than the cash flow estimate (because of the high volume of loans to the World Bank and the IMF in that year). This would have risked the UK not meeting its 0.7 target.

Conclusion on efficiency

The increase in ODA spending managed by non-DFID government departments since 2015 introduced new and sometimes significant value for money risks. Initially few, if any, of the departments were able to meet HM Treasury-set spending targets. There is still considerable concentration of expenditure in the final quarter of the calendar year, which in turn creates value for money risks and made it more difficult for DFID to manage the overall spending target.

DFID adapted and developed its financial management systems to respond to these challenges and succeeded in adjusting its spending to ensure that the UK hit the target each year since 2013. It was able to make use of the flexibility inherent in its programme portfolio, especially through rescheduling multilateral payments and maintaining a dynamic pipeline of projects that could be brought forward as needed. Its ability to act as spender or saver of last resort is, however, closely linked to the scale of multilateral contributions, and the challenge becomes more difficult in years when multilateral replenishments are lower than expected.

Learning: To what extent have departments reduced the value for money risks associated with meeting their spending target?

DFID, HM Treasury and other departments made improvements to their methods for managing ODA spending targets

We have found that processes for managing ODA spending improved across all departments and funds, and most departments are getting closer to meeting their in-year (April to December) spending targets. However, only four non-DFID departments have hit their targets, and the total shortfall in meeting targets across departments remains significant, at around £280 million in 2019. There is also substantial room for improvement in the accuracy of forecasting and reducing the concentration of expenditure in December each year (see Figure 7 in Annex 1).

DFID and HM Treasury undertook a cross-government learning exercise early in each calendar year to encourage key officials to reflect, through surveys and discussions, on experiences from the previous year. The conclusions were presented at SOG meetings and helped to shape an action plan for meeting the target. For example, in 2019 DFID and HM Treasury presented lessons to the SOG on how to improve the accuracy of forecasts and the profiling of spending at planning stages, in order to reduce clustering in December. Lessons identified include the importance of building strong pipelines, undertaking regular monitoring, flagging underspend as early as possible and reducing ‘optimism bias’ in forecasts.

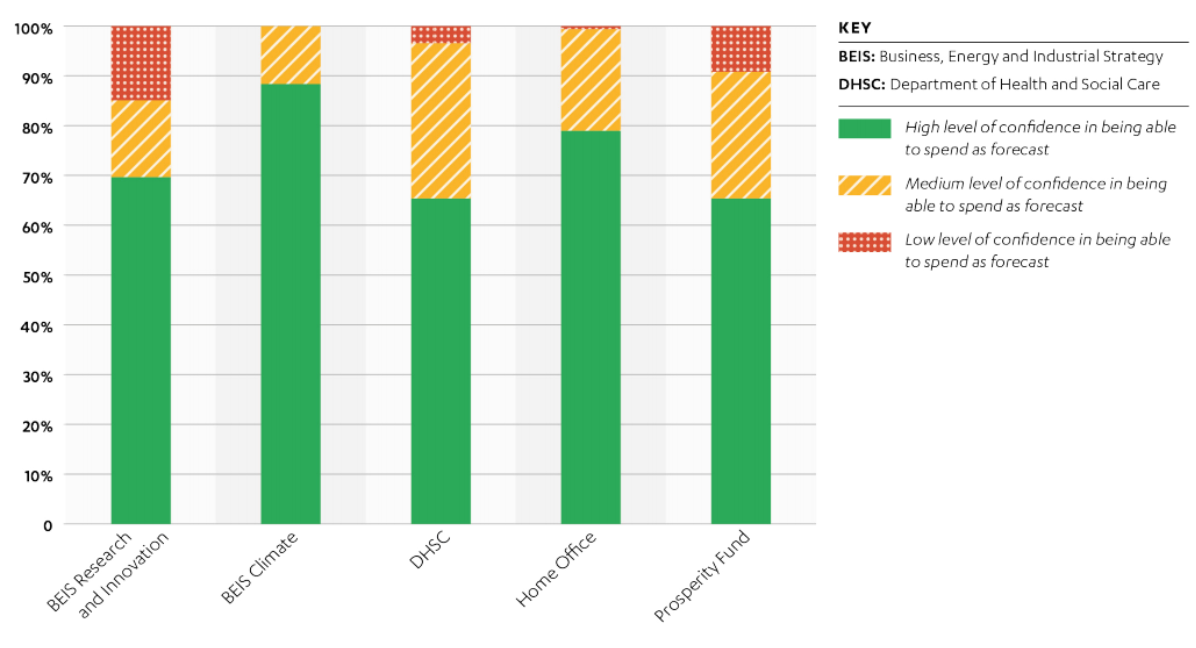

There is clear evidence that these learning exercises led to changes in subsequent years. Examples include HM Treasury’s decision to lower in-year targets for non-DFID departments, following feedback that a ‘one size fits all’ approach was not working. DFID also changed its systems in response to lessons learned. Most notably, it adapted its monitoring processes (including introducing RAG ratings, demonstrating confidence in forecasts) to encourage more timely and accurate forecasts from other departments. Figure 5 below provides an example of RAG ratings from late in the calendar year, when the need for greater accuracy becomes even more important, to illustrate how the ratings are used. In October, red-rated forecasts accounted for 5% of total forecast spend by non-DFID departments. DFID also learned to use historic performance and previous RAG ratings to help judge the accuracy of spend forecasts from other departments.

Figure 5: RAG-rated forecast amounts across non-DFID departments, October 2019

An ongoing challenge and barrier to learning lessons and improving performance has been high staff turnover within departments, which has resulted in some capability being lost as people move on from their ODA management teams.

DFID and HM Treasury provided useful support to other departments in strengthening their practices

We find that HM Treasury and DFID provided substantial support to help aid-spending departments address forecasting challenges, clear obstacles to expenditure and reduce spending shortfalls. Other departments were appreciative of the support they received from HM Treasury and particularly DFID, including on ODA-eligibility questions. As one official described it, the “lines of communication” worked well. DFID produced a significant amount of internal guidance to support its own staff and other departments in managing various components of their spend. This guidance, outlined in Annex 2, included an in-depth financial planning and budgeting policy and smart guides on value for money. The Joint Funds Unit, which manages the Prosperity Fund and the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund, also provided support to participating departments with guidance and training, including on financial management.

DFID responded well to critiques from the International Development Committee and the NAO