Management of the 0.7% ODA spending target in 2020

Acronyms and glossary

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| BEIS | Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, which includes two ODA spending divisions: BEIS Research & Innovation (R&I) and BEIS Climate |

| CDC | Formerly the Commonwealth Development Corporation, a development finance institution owned by the UK government |

| CERF | Central Emergency Response Fund |

| DFID | Department for International Development (merged with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 2020) |

| DHSC | Department of Health and Social Care |

| FCDO Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office FCO | Foreign and Commonwealth Office (merged with the Department for International Development in September 2020) |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| GNI | Gross national income |

| HM Treasury | Her Majesty’s Treasury |

| IDA | World Bank’s International Development Association |

| IDC | International Development Committee |

| IMIG | International Ministerial Implementation Group |

| NAO | National Audit Office |

| ODA | Official development assistance |

| OBR | Office for Budget Responsibility |

| OECD DAC | The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee |

| ONS | Office for National Statistics |

| Q1 | Quarter one – January, February, March |

| Q2 | Quarter two – April, May, June |

| Q3 | Quarter three – July, August, September |

| Q4 | Quarter four – October, November, December |

| SOG | Senior Officials Group |

| Glossary of key terms |

|

|---|---|

| Calendar year and financial year | The calendar year runs from 1 January to 31 December. The financial (or fiscal) year used in government accounting runs from 1 April to 31 March the following year. |

| Underspend | Where activities and spend were expected to be below budget and were treated as savings. |

| Cross-government funds | These funds have their own governance and management structures, and oversee programmes delivered across government departments. These are the Prosperity Fund and the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund, overseen by the Joint Funds Unit. |

| First secretary of state | Office sometimes given to a cabinet minister in UK government, indicating seniority including over all other secretaries of state. |

| Forecasts | Estimated spend by government departments. |

| Main and Supplementary Supply Estimates | Government seeks Parliament’s authority for its spending plans through the Supply Estimates process. Government is only able to finance planned activities if Parliament votes the necessary financial provision. Main Supply Estimates contain the detail of spending plans for a particular year and are presented for parliamentary approval ahead of the financial year in question. Required changes to a department’s budget are presented in January/February of each financial year through Supplementary Estimates. There is a separate estimate for each department. |

| Non-departmental ODA | This is ODA that is not spent by any central government department. In 2020 this included the EU attribution (non-DFID), contributions to the BBC World Service, Gift Aid and aid spent by the devolved administrations. |

| ODA | ODA is defined by the OECD DAC as government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries. |

| ODA Ministerial Group | Cross-government ministers responsible for oversight of UK ODA spend. ODA ministerial meetings bring together ministers from ODA-spending departments to ensure value for money and coherence of ODA. |

| Payment in advance of need | Payment in advance of need is when funds are given before it is demonstrated and agreed that they are needed. Payment in advance of need is not allowed unless approval from HM Treasury is obtained. |

| Spender or saver of last resort | As spender or saver of last resort, DFID (and subsequently FCDO) was required by HM Treasury to spend the difference between non-DFID ODA spend and the 0.7% target to make sure the UK’s ODA commitment was met by 31 December each year. |

| Spending review | A spending review is a governmental process carried out by HM Treasury to set expenditure limits for departments. These reviews usually set multi-year budgets, however government can decide to set only one-year budgets. The last multi-year spending review took place in 2015 and set out expenditure limits for financial years 2016-17 to 2019-20. Spending Review 2019 and 2020 only set out expenditure limits for the following financial year (ie 2020-21 and 2021-22 respectively). |

| Star Chambers | In UK government parlance, a ‘Star Chamber’ is a senior-level meeting of government departments, usually with HM Treasury, to resolve issues relating to budgets. In the context of this review, Star Chambers meetings were convened mid-year to reprioritise ODA spend across departments. |

Executive summary

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a major realignment of the UK aid programme for 2020. Between March and December 2020, the UK government spent £1.39 billion of UK official development assistance (ODA) to address the pandemic and to meet the urgent health and humanitarian challenges facing developing countries. At the same time, in April 2020, the impact of COVID-19 on the UK economy resulted in a sharp fall in projected gross national income (GNI). With the UK committed to achieving but not exceeding the ODA spending target of 0.7% of GNI, this prompted government to plan a £2.94 billion (19%) in-year reduction in aid spending in 2020. This planned adjustment had major implications for both multilateral spend and ongoing bilateral projects, including the cancellation of ongoing and planned programmes and the reprioritisation of activities within programmes.

In 2020, we published a review of the government’s management of the 0.7% spending target over the period 2013 to 2019. We found that cross-government systems were well suited to managing the target when the aid budget increased in a predictable way, but we questioned whether they would be robust enough to handle major economic shocks. This supplementary review extends the analysis into 2020, to assess how well the government managed the unprecedented challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Effectiveness: How effective were the systems and processes for managing the spending target in 2020?

The standing cross-departmental arrangements for managing the spending target described in our first report remained in place for 2020. Some additional, ad hoc structures were established in direct response to the external shocks and played important roles in the reprioritisation of ODA spend. As the likely scale of GNI reduction emerged, the government increased central oversight of the aid budget.

Informed by official April economic forecasts which were less favourable compared to later forecasts of GNI for 2020, departments were directed to adopt an approach which could be characterised as ‘cut once, cut deep’. The cuts approved were based on what officials badged a ‘reasonable worst case’ scenario. A mid-year cross-government reprioritisation process achieved its objective in identifying potential reductions in aid expenditure by £2.94 billion across spending departments, through a combination of underspend in ongoing programmes (linked to COVID-19 delivery constraints), cuts and deferrals of planned expenditure into 2021. In September 2020, the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) were merged to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). DFID/FCDO continued in its role of spender or saver of last resort and increased its level of monitoring of other departments.

As in previous years, DFID/FCDO used the flexibility inherent in its multilateral programme portfolio to manage the target at the calendar year end. A decision was taken to use the deferral of multilateral payments as the primary mechanism for managing uncertainty around the target to limit the need for adjustments to bilateral aid.

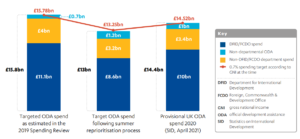

At the beginning of the year, before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, GNI estimates suggested the aid budget would be £15.8 billion. The lowest economic forecasts referenced during the year suggested the aid budget would be £13.3 billion. Latest (provisional) GNI figures for 2020 published by the Office for National Statistics on 31 March 2021 suggested the 0.7% spending target for 2020 was £14,517 million. Government-published statistics recorded provisional UK ODA spend in 2020 as £14,471 million. Using the flexibility of multilateral commitments in combination with cuts to bilateral programmes, in the face of great uncertainty, the government succeeded in meeting the 0.7% spending target.

Efficiency: How well were value for money risks mitigated?

There were several robust approaches taken by government to adjust spend towards the 0.7% target. Aid spending departments continued to make good use of flexibility in the timing of multilateral payments to offset the uncertainty surrounding UK GNI and aid expenditure. Multilateral aid is inherently better placed to manage flexibility in payments than bilateral programmes without disruption to aid delivery. During the reprioritisation process, departments examined their aid programmes in detail to identify where planned activities had in any case been disrupted by the pandemic, and where expenditure could be deferred into 2021 without practical impact. Cross-government coordination processes for the aid programme were stepped up in response to the pandemic. This enabled strategic decisions to be made across the 17 aid-spending departments and funds, rather than asking each to pursue parallel reprioritisation processes.

However, there were also decisions taken which served to increase value for money risk. In our earlier review of the management of the 0.7% ODA spending target we noted that the government’s interpretation of the target as both a floor and a ceiling with a very narrow margin for error was overly rigid (compared to other donors) and posed more challenges in times of significant shock – a finding also commented on by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC) in its peer review and noted in its recent publication of preliminary ODA statistics for 2020 and in Table 2 and Table 3 (in section 3). Other possibilities for managing the 0.7% target, such as shifting to a 0.7% target based on a two- or three-year GNI average that would have enabled the cuts to be planned over a longer period, were not pursued.

In our key stakeholder interviews, it was pointed out that while other donor countries also faced economic contractions in 2020 and some reduced their aid spending, many did not attempt in-year cuts of the same proportion as the reduction to their GNI. Preliminary statistics published recently by the OECD DAC reported that ODA rose to an all-time high of $161.2 billion in 2020, up 3.5% in real terms from 2019. The UK was the third-highest DAC donor (after the USA and Germany), and one of only six countries11 to meet or exceed the UN’s ODA as a percentage of GNI 0.7% target. In the same report, the OECD DAC reported that “ODA rose in sixteen DAC member countries, with some substantially increasing their budgets to support developing countries face (sic) the pandemic. Large increases were noted in Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Norway, Slovak Republic, Sweden and Switzerland. It fell in thirteen countries, with the largest drops in Australia, Greece, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg, Portugal and the United Kingdom.”

While volatile and rising GNI forecasts had been a concern in 2019, in 2020 volatility in GNI forecasts and the eventual reduction in GNI were on a different scale. Focus on single-point, outdated Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) gross domestic product (GDP) forecasts to predict the GNI target caused the government to miss opportunities to mitigate value for money risk. Multilateral flexibility remained key to meeting the target in a volatile GNI context and bilateral cuts made in June went further than necessary, even on the basis of the OBR forecast for GDP available at that time.

In value for money terms, there were pros and cons to the approach taken at Star Chambers. Early and deep cuts minimised the risks that the spending target would be overshot. This also minimised the risk that additional cuts would be needed late in the year when time and options to adjust bilateral spend would have been more constrained. On the other hand, it meant that the reductions were made at a point of significant uncertainty.

There were governance gains in the way systems and processes were adapted to respond to COVID-19 and volatile GNI, with strategic scrutiny of UK ODA spending across departments strengthened to some extent. However, despite attempts to prioritise support to countries classified as highly vulnerable to COVID-19 impacts, these countries were not entirely protected from budget reductions, and moving decision making about portfolio and programme adjustments away from those closest to the detail heightened value for money risks.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

To inform decision making on ODA spend throughout the year, departments responsible for managing UK ODA should use a range of GNI forecasts, calculated by a range of methods and provided by a number of reliable economic commentators (including, though not limited to, the OBR).

Recommendation 2

FCDO should build options for flexing spend into country portfolios and plans, incorporating programme activities that could be scaled up or down in response to external shock, with minimal impact on value for money.

Introduction

In 2020, the UK economy contracted sharply as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the March 2021 estimates from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the UK’s gross national income (GNI) shrank by 5.9% and the UK’s gross domestic product (GDP) shrank by 9.8% – the largest reductions of the economy on record. Final figures will be available in autumn 2021. With the UK committed to achieving but not exceeding the official development assistance (ODA) spending target of 0.7% of GNI, the contraction of the economy prompted government to plan a £2.94 billion (19%) in-year reduction in aid spending in 2020. This reduction in planned spending posed an unprecedented challenge for aidspending departments: before 2020, the aid budget had always expanded with the UK’s economic growth, adding an average of £629 million per year between 2013 and 201915 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The UK’s official development assistance as a percentage of gross national income

In 2020, we published a review of the government’s management of the 0.7% spending target over the period 2013 to 2019. We found that the cross-government governance arrangements and departmental ODA management systems had become increasingly effective over time and were able to mitigate value for money risks when the aid budget increased in a predictable way, but we questioned whether they would be robust enough to handle major shocks. This supplementary review extends the analysis into 2020, to assess how well the governance systems and processes performed in response to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the spending target and on programme delivery. It also examines how management of the spending target changed following the September 2020 merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) and the Department for International Development (DFID) to create the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

Further substantial changes to the aid budget are expected in 2021, following the government’s decision to reduce the spending target temporarily to 0.5%, until “fiscal conditions allow”.18 This review explores lessons from 2020 on how to maintain value for money and minimise the impact of in-year cuts on the UK’s longer-term international development objectives. It does not comment on events in 2021. It also does not comment on the decision to reduce the spending target, which is a matter of government policy and outside ICAI’s remit. Our review questions are set out in Table 1.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria | Question |

|---|---|

| 1. Effectiveness | How effective were the systems and processes for managing the spending target in 2020? |

| 2. Efficiency | How well were value for money risks mitigated? |

Methodology

The methodology for this review mirrors that used for the previous rapid review and updates our findings to include events in 2020 and to incorporate new analysis around the robustness of spending target management systems in changed circumstances. It includes the following components:

- Updated strategic review: Desk review of departmental and cross-government policies, strategies and guidance in relation to management of the target in 2020. We reviewed over 100 documents received from the responsible departments.

- Key informant interviews: We interviewed over 35 stakeholders, including responsible officials from aid-spending departments, HM Treasury and the Cabinet Office, bilateral country team leads and multilateral partners.

- Departmental case studies: We returned to four of the departments assessed as part of the original review – DFID/FCDO, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), the Home Office (HO) and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) – to collect additional data about 2020.

Background

The UK’s commitment to 0.7%

As we described in our previous review, the 0.7% aid-spending target in the UK has a long history. It was first endorsed by the UK in 1974, but it was not until the mid-2000s that a cross-party consensus emerged for a deadline to meet this target. In 2010, the Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government pledged to reach 0.7% by 2013, which was achieved, and the ODA target was enshrined in law in the 2015 International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Act. All parties represented in Parliament supported the target in their election manifestos in 2019. It is government policy to meet and not exceed the target.

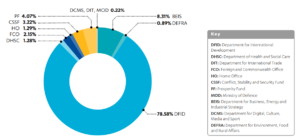

Since 2015, the architecture for managing UK aid has changed considerably. Under the November 2015 aid strategy, more departments were given a role in managing aid.20 Before 2015, the Department for International Development (DFID) managed more than 86% of the aid budget. In 2020, 17 departments and cross-government funds were spending ODA, and DFID’s share of UK ODA in 2020 was 69.4%.

This significantly complicated management of the spending target, requiring careful coordination of expenditure across departments.

ODA management arrangements before 2020

The spending target poses complex financial management challenges for HM Treasury and aidspending departments. A set of coordination arrangements emerged, overseen by the Senior Officials Group (SOG), established in 2016 by HM Treasury and co-chaired by DFID until September 2020, when the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) took over the co-chairing role. Its remit includes ensuring that aid-spending departments meet “high standards for value for money” and, through coordinated effort, achieve the spending target. Departments provide regular updates on their forecast aid expenditure, according to an annual calendar, and are required to spend a large proportion of their aid budgets in the first three quarters of the year. As the largest spender, DFID/ FCDO was designated ‘spender or saver of last resort’, adjusting its expenditure in the final quarter of each calendar year in accordance with gross national income (GNI) forecasts and spending figures from other departments. ODA:GNI ratio is reported by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to two decimal places, affording a margin for error in 2020 of approximately £100 million in either direction, even if the 0.7% is taken as an exact target.

Some aid expenditure falls outside departmental budgets, including parts of the UK’s contribution to the European Union aid budget and Gift Aid (tax rebates for charitable donations by UK taxpayers for international development). These items are non-discretionary and are recorded in the aid statistics as ‘non-departmental spend’. Their size is unpredictable and also needs to be monitored through the year.

Alongside the GNI forecasts produced by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), DFID/FCDO also monitored the outturn GNI estimates produced by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) on a quarterly basis. The ODA:GNI ratio can only be calculated after the end of the calendar year and is not finalised until autumn of the following year at the earliest, although provisional figures are published in March. It

was challenging to plan to spend a share of the size of the economy in a year when the economic context was constantly changing.

The government used two main methods to adjust aid expenditure in response to changing GNI estimates and ODA spending figures. One was to reallocate aid between departments in the final quarter of the year, through Supplementary Estimates. Second, and most importantly, DFID/FCDO adjusted its own expenditure to ensure the target was hit. This was done principally by rescheduling payment of contributions to multilateral organisations to fall either side of the calendar year end.

An unprecedented and challenging year

The pandemic affected UK aid in a number of ways. First, it triggered a global humanitarian crisis of unprecedented proportions. In response, during 2020, the UK government spent £1.39 billion to meet the urgent health and humanitarian challenges facing developing countries (a forthcoming ICAI review will explore the choices made in responding to COVID-19).

Second, lockdown measures, the recall of country-based DFID/FCDO staff and contractors back to the UK, and restrictions on travel imposed around the world disrupted the delivery of ongoing aid programmes.

Third, the negative impact of COVID-19 on the UK economy resulted in a sharp fall in projected GNI. The government therefore undertook unprecedented steps to reduce its planned aid expenditure in year, in order to avoid exceeding the 0.7% target. These adjustments, alongside a decision to pause the approval of new programmes (other than COVID-related programming) while adjustments to spending were decided, had major implications for ongoing bilateral projects, including the cancellation of ongoing and planned programmes, reprioritisation of activities within programmes, and postponements. Planned inyear adjustments to budgeted expenditure also anticipated rescheduling multilateral contributions into the following calendar year on a very substantial scale.

The pandemic resulted not only in a sharp decrease in GNI, but also in a sharp increase in uncertainty. GNI estimates made during the year were based on assumptions about the course of the pandemic and the length and severity of lockdown measures that would be required. Not surprisingly, they were revised substantially through the year as events unfolded.

The COVID-19 pandemic occurred against a background of other considerable changes in UK aid. The UK’s exit from the European Union, a newly elected government, an impending spending review and a planned Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (published in March 2021) all contributed to uncertainty about longer-term priorities. On 16 June 2020, the prime minister announced the merger of DFID and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to form a newly created FCDO, which took place in September 2020. On 2 December 2020, in a letter to the chair of the International Development Committee (IDC), the foreign secretary announced a new strategic framework for ODA to replace the 2015 UK aid strategy, framed as seven global challenges. The letter also set out measures to improve the quality of aid across government, including a cross-government process, led by the foreign secretary, to review, appraise and finalise all of the UK’s ODA allocations to all government departments against the government’s priorities for 2021 with the agreement of the chancellor and department secretaries of state. Secretaries of state and accounting officers remain accountable for the ODA allocated to their departments as per managing public money guidance.

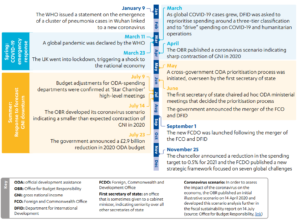

A timeline showing key events in the 2020 ODA management calendar is shown in Figure 2. This illustrates the DFID prioritisation exercise in the spring and the reprioritisation exercise, led by the first secretary of state (FSS), in the summer of 2020.

Figure 2: Timeline of key events affecting the management of official development assistance in 2020

Source: Timeline compiled from information gathered during interviews with UK government.

Findings

Effectiveness: How effective were the systems and processes for managing the spending target in 2020?

The government’s interpretation of the spending target made it more difficult to absorb shocks of the scale experienced in 2020

Our first review found that the cross-government systems used for managing the official development assistance (ODA) spending target were broadly effective in managing the level of uncertainty experienced in most years. However, we pointed to several features that might create problems if greater volatility were experienced. One of these was the treatment of the spending target as a floor as well as a ceiling, leaving a very narrow margin for error for the level of spending. We recommended that the government explore flexibility in its interpretation of the spending target – for example, introducing a ‘tolerance range’ for hitting the target of between 0.69% and 0.71% gross national income (GNI), or specifying the target as a three-year rolling average. The government agreed with the principle of introducing greater flexibility into the management of the ODA/GNI target. However, even in the exceptional circumstances of 2020, in year there appeared to have been no discussion of interpreting the aid target so as to allow more flexibility over the timing of cuts. The difficulties in reprioritising aid on the scale required in such a short period of time illustrate the shortcomings of a rigid interpretation of the target – a point also made in an article written by the Director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) and published in The Times. In the article, the author noted that “making funding cuts on this scale, this quickly will mean cuts where they are feasible rather than where value for money is lowest”. The author

also reflected on the value of using the spending target as a guide, saying that hitting the target exactly “creates unnecessary complexity”.

In our key stakeholder interviews, it was pointed out that while other donor countries also faced economic contractions in 2020 and some reduced their aid spending, many did not attempt in-year cuts of the same proportion as the reduction to their GNI. Preliminary statistics published recently by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC) reported that ODA rose to an all-time high of $161.2 billion in 2020, up 3.5% in real terms from 2019. The UK was the third-highest DAC donor (after the USA and Germany), and one of only six countries to meet or exceed the UN’s ODA as a percentage of GNI 0.7% target. In the same report, the OECD DAC reported that “ODA rose in sixteen DAC member countries, with some substantially increasing their budgets to support developing countries face (sic) the pandemic. Large increases were noted in Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Norway, Slovak Republic, Sweden and Switzerland. It fell in 13 countries, with the largest drops in Australia, Greece, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg, Portugal and the United Kingdom” (see Table 2 for the percentage change in 2020 ODA from 19 DAC countries that are EU members and primary reasons for the changes, compared to 2019, and Table 3 for the percentage change in 2020 ODA from non-EU DAC countries and primary reasons for the changes, compared to 2019).

Table 2: Percentage change in 2020 ODA from 19 DAC countries that are EU members, compared to 2019

| Country | Change | Primary reason for change |

|---|---|---|

| Hungary | 35.8% | Increase in overall aid programme |

| Sweden | 17.1% | Due to contributions to the Green Climate Fund |

| Slovak Republic | 16.3% | Due to debt relief operations |

| Germany | 13.7% | Mobilisation of additional ODA resources to fight the pandemic |

| France | 10.9% | Increase in bilateral aid and funding for COVID-19, including through lending |

| Finland | 8.1% | Increase in multilateral contributions |

| Belgium | 2.8% | Increase in contributions to multilateral institutions, in particular UN organisations |

| Poland | 1.1% | Slight increase due to a larger contribution to EU institutions |

| Austria | 0.6% | Slight increase due to multilateral contributions |

| Denmark | 0.5% | Slight increase in contributions to multilateral organisations |

| Slovenia | -1.7% | Slight decrease in bilateral aid |

| Spain | -1.8% | Slight decrease in bilateral aid |

| Netherlands | -2.8% | Decrease to maintain the same ODA to GNI ratio as in 2019 (0.59%) |

| Ireland | -4.1% | Lower volume of costs reported for in-donor refugees |

| Czech Republic | -5.2% | Lower volumes of debt relief compared to 2019 |

| Italy | -7.1% | Fall in bilateral grants as well as in-donor refugee costs |

| Luxembourg | -9.2% | Decrease in bilateral grants |

| Portugal | -10.6% | Decrease in contributions to multilateral organisations |

| Greece | -36.2% | Lower costs for in-donor refugees |

Source: COVID-19 spending helped to lift foreign aid to an all-time high in 2020, Detailed Note, OECD DAC, 13 April 2021, link.

Table 3: Percentage change in 2020 ODA from non-EU DAC countries, compared to 2019

| Country | Change | Primary reason for change |

|---|---|---|

| Switzerland | 8.8% | Overall increase in aid budget and additional funding to support developing countries with the pandemic |

| Norway | 8.4% | Increase in health-related ODA and contributions to the Green Climate Fund |

| Iceland | 7.8% | Increase in contributions to multilateral organisations |

| Canada | 7.7% | Increases in climate financing and costs for in-donor refugees |

| United States | 4.7% | Increased contributions to multilateral organisations |

| Japan | 1.2% | Increase in bilateral lending |

| New Zealand | -5.2% | Decrease in bilateral aid |

| Korea | -8.6% | Cuts in overall aid programme |

| United Kingdom | -10% | Cuts driven by the decrease in GNI while meeting the ODA to GNI ratio of 0.7% |

| Australia | -10.6% | Cuts in bilateral aid programme |

Source: COVID-19 spending helped to lift foreign aid to an all-time high in 2020, Detailed Note, OECD DAC, 13 April 2021, link.

Cross-government coordination was strengthened and decision-making centralised

The standing cross-departmental arrangements for managing the spending target described in our first report remained in place for 2020. The Senior Officials Group (SOG), co-chaired by HM Treasury and DFID/FCDO, continued to operate, and a ‘working-level’ SOG made up of technical-level officials remained active throughout the year. The ad hoc ODA ministerial meeting was reconvened in June 2020, having been dormant for some years.

The SOG was seen as an effective governance structure by HM Treasury, DFID/FCDO and other aid spending departments. HM Treasury used the meetings to deliver clear messages on how departments should manage their spending targets. The standing ‘working-level’ SOG came into its own early in the year, enabling detailed government-wide conversations about the financial risks presented by COVID-19 and GNI shocks. Connections made within the working group meant that, when the pandemic began, HM Treasury was able to reach out quickly to departments to obtain financial and programming details and inform SOG discussions ahead of time. Feedback from key government stakeholders was that these mechanisms were robust and effective.

Some additional ad hoc ministerial-level structures were established in direct response to the external shocks and played important roles in the reprioritisation of ODA spend. These were the International Ministerial Implementation Group (IMIG), which led the UK’s global response to COVID-19, and ‘Star Chambers’ that decided reductions in ODA budgets for 11 ODA spending departments and funds. Six departments and ODA contributors with a combined spend in 2019 of £142 million were exempted from the process as their (relatively small) ODA budgets are used to fund largely fixed activities such as international subscriptions.

As the likely scale of GNI reduction emerged, the government increased central oversight of the aid budget, something that the National Audit Office (NAO) and ICAI have been advocating since the UK aid architecture changed in 2015.34 Cross-government governance arrangements were strengthened to some extent as ODA ministerial and Star Chambers meetings were convened to examine which aidfunded programmes should be protected and which were open to reprioritisation. These were chaired by Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab in his capacity as the first secretary of state. He was supported by a secretariat from the Cabinet Office and HM Treasury.

In-year reprioritisation of ODA across government departments was overseen by ministers through four Star Chambers meetings between 30 June and 9 July. On 20 July, the prime minister signed off on a package of up to £2.94 billion in-year ODA budget reductions. This amount was considered by officials a ‘reasonable worst case’ scenario based on the April 2020 Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) gross domestic product (GDP) forecast that implied the 0.7% GNI target could fall by £2.5 billion from the pre-COVID-19 OBR March forecast, and further adjusted to anticipate an increased contribution to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Poverty Reduction Growth Trust (PRGT) and some underspend by non-DFID departments (see paragraphs 3.39 and 3.40).

Aid-spending departments responded quickly and efficiently to the changed circumstances of 2020

This centralised summer reprioritisation process (as described in a stakeholder interview) built on efforts by individual departments to reorient their programming to support the response to COVID-19 in partner countries. As early as February 2020, the responsible departments began to assess the implications of the pandemic for their aid expenditure. Prompt attention was also given to assessing the operational implications of the pandemic and the likely disruption to ongoing programmes. In March, HM Treasury asked departments to report on areas of flexibility where resources could be freed up for humanitarian and COVID-19 response. In early April, HM Treasury noted that departments were not forecasting major underspends and so did not propose to recommend any immediate reallocations in the Main Supply Estimates for 2020-21 being presented for Parliament vote in early May 2020. HM Treasury asked departments to provide early notice of any emerging areas of underspend.

The UK government was quick to articulate its objective of playing a leading role in the global response to COVID-19. DFID/FCDO led on the identification of new spending priorities. By the end of the year, the UK had announced new multi-year ODA commitments of up to £1.3 billion for COVID-19, including £312 million for humanitarian support to the most vulnerable countries, £834 million to support the development and equitable distribution of vaccines, treatments and tests and other critical research and development, and £150 million for urgent economic support. This was in addition to adapting existing (primarily bilateral) programmes. DFID/FCDO reportedly accounted for 97% of UK COVID-19 ODA. The £1.39 billion figure published in the Statistics on International Development refers to total ODA spend on COVID-19 by the end of 2020 and includes both the new commitments and the adapted programmes. The figure does not include the UK’s core contributions to multilaterals, a proportion of which will have been channelled to address the COVID-19 pandemic. ICAI will explore the choices made centrally and within countries on the COVID-19 response in forthcoming reviews.

To free up resources for new and additional COVID-19 spending and to accommodate the foreseen budget reduction that accompanied the fall in GNI, between March and May 2020 DFID/FCDO undertook two major exercises to reprioritise ongoing aid programmes. The exercises also identified opportunities to ‘pivot’ existing programmes in response to the pandemic, by reorienting planned activities in support of the response and rescheduling or stopping less response-relevant activities. The criteria used in these DFID/FCDO reprioritisation processes are described in paragraphs 3.19 to 3.26.

By May, it became clear that deeper cuts would be needed to address the fall in GNI. As spender or saver of last resort, DFID/FCDO worked to identify up to £3.5 billion of potential savings from its budget (see paragraph 3.21). The international development secretary wrote to the prime minister and first secretary of state advising them of her intentions and insisting that the cuts be shared fairly and transparently across aid-spending departments. The cross-government reprioritisation Star Chambers process was instituted following an ODA ministerial meeting in June. The centrally managed Star Chambers reprioritisation strategy and processes strengthened strategic scrutiny of UK ODA spending across departments to some extent.

However, as it turned out, the approach adopted by central government at mid-year resulted in more drastic aid cuts than were needed

In May, on the basis of its own internal preparations for likely GNI-related cuts, DFID/FCDO articulated its strategy for managing the uncertainties around the aid target, namely to protect bilateral programmes, and use flexibilities in multilateral payments – as commonly done to manage the aid target – to deal with GNI fluctuations as they evolved. However, this strategy was superseded mid-year by the more

pessimistic ‘cut once, cut deep’ approach adopted by the ODA Ministerial Group in June, informed by the April OBR GDP estimate that officials badged as a ‘reasonable worst case’ 0.7% spending target prediction. This strategy required the 11 departments and funds involved in the Star Chambers reprioritisation process to identify 30% reductions to their 2020-21 Q1-Q3 aid budgets. Flexibility in the timing of the remaining multilateral payments would then be used to manage GNI volatility at year end.

As it transpired, the OBR soon revised upwards its 2020 GDP forecast made in April. OBR GDP forecasts published on 14 July (five days after ministers decided on reductions to departmental budgets) suggested that the reduction to the ODA target would not be as substantial as the ‘reasonable worst case’ that informed the reprioritisation exercise (with the 0.7% target expected to be between £150 million and £720 million higher than the ODA target under the ‘reasonable worst case’ scenario). However, ministers decided not to reopen the reprioritisation decisions taken at the Star Chambers meetings. The cuts approved by Star Chambers on 9 July and then endorsed by the prime minister on 20 July were therefore more drastic than were needed based on the information available to HM Treasury at the time, even taking the most negative scenario into account. Officials said that, at the time, this was a ‘reasonable worst case’ assumption and noted that hindsight might set this decision in a harsher light. As we discuss below, this had significant value for money consequences, especially for UK bilateral programmes, as these faced greater risks from cuts than multilateral programmes.

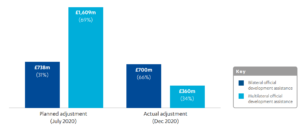

In fact, the original DFID/FCDO strategy of using the full flexibility afforded by multilateral contributions to manage the GNI-related uncertainty would have been viable, although this would not have been known at the time. The adjustment in DFID/FCDO bilateral aid agreed at Star Chambers was £738 million (including a deferral of £485 million to CDC from 2020-21 to 2021-22). The amount of ‘unused’

flexibility in multilateral payments available at year end exceeded the total bilateral adjustment planned at Star Chambers, so if DFID/FCDO had been allowed to manage the required reductions based on its understanding of context and individual programmes, cuts to DFID/FCDO’s bilateral aid programmes could have been avoided. This demonstrates the downside of centralising decision making through Star Chambers rather than allowing those who are more conversant with their portfolio to make tailored judgements. One senior interviewee regretted the “overshooting of bilateral cuts” but made the argument that overall, in aggregate, DFID/FCDO’s prioritisation of multilateral spend was appropriate given the need for a comprehensive global coordinated response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Value for money risks were further exacerbated by the speed at which the Star Chambers process took place. Although departments had already been examining their portfolios to identify areas where savings could be made, aid-spending departments were given five to seven working days to prepare proposals for the 30% budget cuts. The proposals were reviewed, revised and approved by ministers over four virtual meetings totalling just seven hours. One of the officials we interviewed described it as “like doing a handbrake turn with an oil tanker”.

Budget reductions were rightly distributed unevenly across departments

The 30% reduction in spend over three quarters called for through the Star Chambers process was substantial, and made more so by the fact that planned reductions were decided in July, when there were only two quarters of the calendar year left in which to adjust expenditure. In practice, not all departments were able to identify reductions of that magnitude due to the differing size and nature of their aid budgets. Star Chambers ended up approving a wide range of percentage budget adjustments, from a 53% reduction for the Department for International Trade to a projected overspend of 4% by the Home Office (linked to higher-than-expected asylum seeker support costs in 2020, which are demand-driven and not amenable to management). Some departments saw their budget proposal increased at Star Chambers, while others were unchanged or decreased. The reduction in spend agreed for DFID/FCDO at Star Chambers amounted to £2.35 billion, representing a 24% reduction on DFID/FCDO’s forecast 2020-21 Q1-Q3 budget (against DFID/FCDO’s initial proposal of a 30% budget adjustment for the same period).

Reductions in spend agreed at Star Chambers totalled £2.94 billion and fell into three categories: “underspend” where activities and spend were expected to be below budget and were treated as savings, “cuts to 2020-21 Q1-Q3 spend” where activities and spend were stopped, and “spend delayed to 2020-21 Q4” where spend on activities was postponed until the following calendar year.

Cuts primarily affected bilateral programmes and across all departments amounted to £943 million (32% of the total £2.94 billion reduction). Of this amount, DFID/FCDO saw cuts to its bilateral budget of £738 million (see Table 4). Total adjustments to the DFID/FCDO spend amounted to £2,347 million and were equivalent to 78.3% of the total cuts agreed for all departments, five percentage points above DFID/

FCDO’s 73.2% share of UK ODA spending in 201937,38 (see Figure 3).

Table 4: Planned adjustments and revised 2020 target spend by department

| Budget adjustments agreed at summer reprioritisation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Planned underspend | Cuts to 20-21 Q1-Q3 forecast | Delay to 2020-21 Q4 | Total Calender year reduction from April Q1-Q3 forecast | Revised target ODA spend for 2020 (post-summer reprioritisation) * |

| Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy | -£6m | £52m | £202m | £248m | £981m |

| Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport | 0 | £1m | 0 | £1m | £10m |

| Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 0 | 0 | £27m | £27m | £67m |

| Department for International Development | 0 | £738m | £1,609m | £2.347m | - |

| Department of Health and Social Care | £14m | £9m | £15m | £38m | £247m |

| Department for International Trade | £1m | £3m | 0 | £4m | £4m |

| Foreign and Commonwealth Office | £1m | £50m | £13m | £64m | £603m |

| Home Office (nonasylum costs only) | £28m | 0 | £10m | £39m | £495m*** |

| Conflict, Stability and Security Fund | -£24m | £40m | £81m | £96m | £535m |

| Prosperity Fund | £32m | £50m | £39m | £122m | £213m |

| Ministry of Defence | £2m | 0 | 0 | £2m | £6m |

| ODA contributors**** not included in summer reprioritisation | - | - | - | - | £48m |

| Total planned adjustments to budgets at summer reprioritisation | £48m | £943m | £1,996m | £2,987m | £3,207m |

Figure 3: Share of UK aid budget reductions agreed for Q1 to Q3 of financial year 2020-21

Source: HM Treasury Technical Notes issued to spending departments and cross-government funds, July 2020.

The criteria used for reprioritisation were open to broad interpretation and inconsistently applied

The spring DFID/FCDO COVID-19 reprioritisation and the summer cross-departmental GNI-related reprioritisation exercises were informed by multiple, competing and different criteria.

In March and April 2020, DFID/FCDO asked its spending divisions to prioritise their activities to respond to COVID-19 with reference to a three-tier classification: Gold (‘drive’), Silver (‘manage’) and Bronze (‘pause’). The highest priority (Gold) went to the COVID-19 response and ongoing humanitarian operations, while other key development and manifesto priorities were rated Silver. Policy and programme work and cross-government engagement falling outside these two categories were rated Bronze. This referred not only to programme spend but also to the redeployment of staff to priority Gold activities. New programming was put on hold (unless approved by ministers), pending the reprioritisation. This process was described in more detail in ICAI’s December 2020 information note on how procurement was managed during the reprioritisation.

In May, the international development secretary instituted a second reprioritisation exercise within DFID/ FCDO to address likely GNI-related cuts, directing spending divisions to identify a third of their portfolio by value that could be deprioritised, based on a set of priorities (Category 1, 2 and 3) and ranking criteria drawn up by ministers. Programmes concerned with protecting the lives of the most vulnerable people and reducing the severity and length of the COVID-19 crisis for those in the most vulnerable countries were included in Category 1. Programmes related to the pursuit of manifesto commitments and restoring progress on the Sustainable Development Goals were included in Category 2, and all other DFID/FCDO business was badged as Category 3. To inform decisions about which programmes within their portfolios could be deprioritised, divisions were asked to consider ranking criteria of national interest, supplier health, reputational issues and exit costs.

With regard to the summer reprioritisation, which was launched by the first secretary of state in early June, the relevant departments and funds were asked to identify a third of their portfolio by value that could be deprioritised. The criteria applied were based on, and superseded, those adopted by DFID/FCDO for earlier reprioritisation exercises. Departments were asked to prioritise their programme and 2020 ODA spend based on a number of broadly defined goals, including the UK’s global COVID-19 response, manifesto commitments on climate change and girls’ education, ‘advancing Global Britain and the UK as a force for good’, and ‘bottom billion’ poverty reduction. They were also asked to take into account existing commitments, strategic challenges posed by the pandemic, value for money and deliverability.

While some guidance on how to categorise spend according to certain criteria was provided, interpretation of criteria varied, and it remained unclear how different criteria should be weighted when deciding how to prioritise and rank each programme within a portfolio.

We were provided with little evidence that criteria used in the summer reprioritisation were consistently applied across or within ODA-spending departments, and no evidence to suggest that decisions to badge programmes as meeting the criteria were systematically reviewed to confirm consistency in approach to badging.

Some of the criteria, notably ‘COVID-relevant’, ‘advancing Global Britain and the UK as a force for good’ and ‘value for money’ were open to a great deal of interpretation. For example, analysis of DFID/FCDO 2020 management spend data suggested that 55% of all spend was badged as ‘COVID-relevant’. One official attributed this to teams interpreting the criterion as requiring the repurposing of programmes to support COVID-19, rather than badging programmes that were COVID-relevant (for example health, humanitarian, WASH programmes) as such. According to the same analysis, more than a quarter (28%) of DFID/FCDO’s 2020 spend was categorised as ‘advancing Global Britain and the UK as a force for good’, having been badged as such for the Star Chambers reprioritisation process.

Value for money was listed as one of the criteria for consideration at Star Chambers. We noted that DFID/FCDO referred to a variety of value for money considerations in its proposal for 30% reductions in spend, and officials cited value for money as being a key factor in assessing trade-offs in reducing spend between programmes. We were not given access to what lay behind the judgements for these value for money assessments.

Budget reductions were concentrated in vulnerable countries

It is notable that the successive reprioritisation processes consistently highlighted the importance of protecting support for the countries considered most vulnerable to COVID-19. In April 2020, in a document entitled ‘Battleplan for Vulnerable Countries’, the government identified 40 ODA-eligible countries that were deemed highly vulnerable and stated that they were to be prioritised for support and have their progress in responding to COVID-19 tracked. A wider circle of countries was placed on a ‘watch list’, for monitoring as the pandemic unfolded. When it came to the additional funds programmed in 2020 for COVID-19 response, the greater share did indeed go to countries classified as ‘highly vulnerable’.

However, these countries were not entirely protected from cuts during the summer reprioritisation exercise. Our analysis of DFID/FCDO post management data41 suggests that in 24 of the 40 countries classified as highly vulnerable where DFID/FCDO had a post, DFID/FCDO spending in these 24 countries in 2020 fell by £753 million (compared to 2019), equivalent to around one-fifth of 2019 spend and an average of £31 million per country (see Table 5). These reductions in spend were on average six times greater in value than the reductions in DFID/FCDO spend in countries not classified as highly vulnerable where DFID/FCDO had a post (see Table 6), a finding partly explained by the fact that only sizeable programmes, of the type listed in Table 6, could make a significant contribution to cuts. Only one highly vulnerable country, Sudan, received an overall increase in aid in 2020 compared to the previous year.

Table 5: Outcome in countries with a DFID/FCDO mission classified as highly vulnerable to COVID-19 impacts (according to DFID/FCDO management information)

| DFID/FCDO mission | Cash spend calendar year 2019 | Cash spend calendar year 2020 | Difference in cash spend 2020 vs 2019 | Percentage change 2020 vs 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFID Pakistan | £265m | £164m | (£101m) | -38% |

| DFID Syria | £251m | £178m | (£72m) | -29% |

| DFID Uganda | £138m | £71m | (£67m) | -49% |

| DFID South Sudan | £203m | £149m | (£54m) | -27% |

| DFID Bangladesh | £246m | £196m | (£50m) | -20% |

| DFID DRC | £188m | £141m | (£47m) | -25% |

| DFID Yemen | £252m | £205m | (£47m) | -18% |

| DFID Ethiopia | £289m | £244m | (£45m) | -16% |

| DFID Kenya | £106m | £63m | (£44m) | -41% |

| DFID Mozambique | £92m | £52m | (£40m) | -44% |

| DFID Afghanistan | £194m | £154m | (£40m) | -21% |

| DFID Tanzania | £131m | £92m | (£39m) | -30% |

| DFID OPTs | £114m | £78m | (£36m) | -31% |

| DFID Somalia | £146m | £120m | (£26m) | -18% |

| DFID Nigeria | £231m | £211m | (£20m) | -9% |

| DFID Ghana and Liberia* | £45m | £26m | (£20m) | -43% |

| DFID Malawi | £70m | £57m | (£13m) | -19% |

| DFID Zambia | £46m | £35m | (£11m) | -25% |

| DFID Caribbean* | £32m | £22m | (£10m) | -30% |

| DFID Myanmar | £102m | £94m | (£8m) | -8% |

| DFID Sierra Leone | £73m | £68m | (£5m) | -7% |

| DFID Zimbabwe | £93m | £89m | (£4m) | -4% |

| DFID Brazil** | £0m | £0m | (£0m) | -33% |

| DFID Sudan | £82m | £127m | £45m | 55% |

| Subtotal for countries with DFID/FCDO missions classified as highly vulnerable to the impacts of COVID-19 | £3,387m | £2,634m | -£753m | -22% |

| Average reductions | -£31m | |||

Table 6: Outcome in countries with a DFID/FCDO mission not classified as highly vulnerable to COVID-19 impacts (according to DFID/FCDO management information)

| DFID/FCDO mission | Cash spend calendar year 2019 | Cash spend calendar year 2020 | Difference in cash spend 2020 vs 2019 | % change 2020 vs 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFID Jordan | £97m | £65m | (£32m) | -33% |

| DFID Lebanon | £123m | £94m | (£30m) | -24% |

| DFID Rwanda | £63m | £41m | (£22m) | -35% |

| DFID Iraq | £37m | £15m | (£22m) | -59% |

| DFID Nepal | £83m | £78m | (£4m) | -5% |

| DFID Indonesia | £13m | £11m | (£2m) | -18% |

| DFID Ukraine | £7m | £5m | (£2m) | -25% |

| DFID North Africa Joint Unit* | £2m | £0m | (£1m) | -73% |

| DFID Southern Africa** | £5m | £5m | £0m | 4% |

| DFID Middle East and North Africa Department*** | £3m | £3m | £0m | 13% |

| DFID Central Asia | £6m | £8m | £1m | 21% |

| DFID India | £26m | £33m | £7m | 28% |

| DFID Turkey | £13m | £41m | £29m | 229% |

| Subtotal for countries with DFID/FCDO missions classified as highly vulnerable to the impacts of COVID-19 | £477m | £399m | -£78m | -16% |

| Average reductions | -£6m | |||

*Zero values due to rounding. Cash spend calendar year 2020: £0.4m

** Zero values due to rounding. Difference in cash spend 2020 vs 2019: -£0.2m

** Zero values due to rounding. Difference in cash spend 2020 vs 2019: -£0.4m

Source: DFID/FCDO management information, 2020

Measures were taken to improve the forecasting of aid expenditure

The systems used by aid-spending departments to monitor and manage their ODA spending through the year, and those applied by DFID/FCDO and HM Treasury to oversee the process, continued broadly as described in our first report, with some adaptations to the unusual circumstances.

In relation to previous years, DFID/FCDO increased its level of monitoring of other departments. It requested formal reports on aid expenditure on five occasions between March and November. These were accompanied by frequent informal contact. Reporting then stepped up significantly towards calendar year end.

In 2015, HM Treasury had required aid-spending departments to frontload the spending of their aid budgets into the first three quarters of the financial year, to help with meeting the calendar year-end target. DFID/FCDO was required to frontload 90% of its aid, while for other departments the target was 80%. HM Treasury first reduced this to 85% (2017-19) and then to 80% (2020). In our previous review we questioned this ‘one-size fits all’ approach and recommended that HM Treasury considered tailoring spending targets for the first three quarters of the financial year to each ODA-spending department and cross-government fund, to reflect the structural nature and spending profile of their programme portfolios and reduce negative effects for suppliers.

Although the government only partially agreed with this recommendation made in our 2020 review, in the circumstances of 2020 the government modified its approach to monitoring, agreeing bespoke spending schedules for each department at Star Chambers that it monitored ODA spend by non-DFID/ FCDO departments against over the remainder of the year. FCDO informed us that, despite this change

in approach, during 2020 some departments continued to experience problems with the concentration of payments towards the year end. The NAO expressed concerns about this practice in 2015 with reference to DFID, and again in 2017 when it looked at ODA spending across UK government.

Overall, the reprioritisation of ODA spending during the year and the replacement of uniform spending targets with tailored spending plans improved the ability of departments to forecast their expenditure.

DFID/FCDO continued to use flexibility in the timing of multilateral contributions to manage the year-end target

As in previous years, FCDO used the flexibility inherent in its multilateral programme portfolio to manage adjustments to spending required to meet the target at the calendar year end. Large multilateral payments were rescheduled to the first quarter of 2021, including a contribution of £1.1 billion to the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA). When it transpired later in the year that 2020 GNI was higher than previously forecast, some of these payments (including a contribution of £775 million to IDA) were brought forward into December 2020 to allow the target to be reached.

The multilateral organisations that we consulted confirmed that the UK had communicated its plans to them at an early stage to minimise disruption to their activities. As we found in the first report, small changes to the timing of multilateral payments do not usually affect their operations. The World Bank confirmed again that its ability to spend funds had been unaffected, even in the face of increased demand for its resources during COVID-19. IDA had been able to respond quickly to the increased demand from IDA-eligible recipient countries, and to respond at scale, using pooled contributions from donor countries. Demand was such that the World Bank will have used the funds committed to IDA under the 19th replenishment round one year earlier than planned, and is in discussion with donors about completing the next replenishment round before the end of 2021.

A few of the departments that we spoke to indicated that in making the required adjustments to their budgets they had sometimes chosen to defer planned expenditure into 2021, rather than make permanent cuts and avoid unnecessarily reducing capacity or impact. However, they were not aware at the time that 2021 would see further deep cuts in UK aid as a result of the reduction of the spending target to 0.5% of GNI, and that deferred expenditure was also therefore at risk of being cut. Officials informed us that had they known this, they might have approached the value for money choices facing them in the second half of 2020 differently. However, both the Cabinet Office and HM Treasury told us that the 0.5% decision had not yet been made when the major 2020 reprioritisation decisions were taken. The decision to cut ODA to 0.5% GNI was announced on 25 November 2020.

Having flexible programme instruments in their portfolios also helped some bilateral portfolios reduce value for money risks

In response to a question about why humanitarian spend in a particular country had fallen so significantly between 2019 and 2020, one development director noted that it had been possible to increase humanitarian spend in 2019 when resources became available, as this had at the time been considered best value for money. While this 2019 decision exaggerated the reported reduction in humanitarian spend compared to the level that the office typically provided in response to the protracted humanitarian crisis in country, it did serve to highlight that having flexible instruments within a bilateral portfolio of programmes can, like multilateral contributions, offer in-year budgetary flex.

Volatility in forecast non-departmental ODA put downward pressure on other areas of the budget

Volatility in non-departmental ODA forecasts put downward pressure on other areas of the budget.

This was particularly the case for the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) Poverty Reduction Growth Trust (PRGT), which provides concessional loans for low-income countries facing balance of payment needs. Donor loans to the PRGT are drawn down when required, and drawdown levels therefore vary according to the level of need each year. Increased demand from low-income countries for emergency

concessional loans in direct response to COVID-19 prompted the IMF to approach bilateral lenders and donors to augment the PRGT’s resources.46 The amount of the UK’s loan to the PRGT that was forecast to be drawn down proved particularly volatile in 2020, given the uncertain economic outlook and unpredictable levels of demand. This was forecast at zero at the start of the year before the COVID-19 crisis, rising to £540 million at mid-year and ending the year at £255 million.

The UK has agreed with the IMF that its loan to the PRGT cannot be drawn down in December, which helps FCDO with managing the ODA target. Nonetheless, the higher projections during the year had a significant influence on the extent of prioritisation that was undertaken, leading Star Chambers to target £2.94 billion in overall reductions to existing planned programmes rather than £2.5 billion, to make room

for the disbursements to the PRGT. The government worked closely with the IMF to understand the latest projections of the UK loan drawdown. However, given high uncertainty in the economic outlook and levels of demand from the PRGT, these projections were subject to variability. Uncertainty in 2020 GNI forecasts could have been managed with less pessimism bias

The full extent of the shock to the UK economy caused by the pandemic was unknown throughout 2020, and GNI estimates fluctuated substantially during the year. Aid-spending departments faced not only a reduction in their budgets, but also an unprecedented level of uncertainty.

At the beginning of the year, before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, GDP estimates (used as a proxy for GNI) suggested the aid budget would be £15.78 billion. The lowest GDP forecasts referenced during the year suggested the aid budget would be £13.25 billion, equivalent to a £2.53 billion (16%) reduction in the 0.7% target compared to the early year estimate. By the end of November, the estimate of the 0.7% target had been revised upwards to £14.35 billion, resulting in the final in-year reduction to the 2020 aid budget of £1.43 billion (9%) compared to the budget that had been expected at the start of the year. This was still a substantial cut in aid spending, but just 57% of what had been expected at the time the major reprioritisations were undertaken.

Latest (provisional) GNI figures for 2020 published by the ONS on 31 March 2021 suggested the 0.7% spending target for 2020 was £14,517 million.47 Government-published statistics recorded provisional UK ODA spend in 2020 as £14,471 million.48 This figure is £122 million higher than the £14,349 million target FCDO was aiming at on 31 December 2020 and illustrates how applying more flexible approaches to

target management, such as tolerance ranges as recommended in our earlier review,49 can be helpful in meeting the target. It was not clear from the data available to us exactly what this £122 million post-year spend comprised. Final spend data for 2020 is expected to be published in September 2021. Figure 4 illustrates the change in the 0.7% spending target at different points in the year and shows how DFID/ FCDO management planned to meet it by adjusting spending plans accordingly.

Figure 4: Official development assistance target spend and 0.7% spending target in 2020

Source: DFID/FCDO management information, 2020 and Statistics on International Development Provisional UK Aid Spend 2020, FCDO, April 2021, link.

The fluctuation in GDP forecasts that followed the COVID-19-induced shock to the economy raises important questions about forecasting and scenario planning. Although it considered a range of different forecasts, the government decided to exclusively use GDP estimates provided by the OBR to estimate its ‘reasonable worst case’ for the aid-spending target. The size of the reduction to ODA decided at Star Chambers was informed by the OBR’s April estimate of real GDP growth, which was not up to date at the time it was used to inform the summer reprioritisation process and was in fact lower than all 21 forecasts and the OBR’s July forecast that were available to HM Treasury at the time.

An unexpected anomaly in relation to the GDP deflator which had a significant impact in 2020, and which only became apparent in August following the publication of ONS outturn data, created an added complication to interpreting the GDP forecast issued in July. It also appears that in 2020, because of the way the economy responded to the COVID-19 shock, GDP was a less good proxy for GNI than it had been

in 2019 (see Table 7). In 2019, UK GDP (£2,172,511 million) was a close (99%) proxy for UK GNI (£2,203,201 million). In 2020, UK GDP (£1,958,591 million) came in lower, at 94% of UK GNI (£2,073,880 million).

Table 7: GDP as a proxy for GNI in 2019 and 2020

| GDP | GNI | GDP/GNI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | £2,172,511m | £2,203,701m | 99% |

| 2020 | £1,958,591m | £2,073,880m | 94% |

| Difference 2020 vs 2019 | -£213,920m | -£129,821m | |

| Difference 2020 vs 2019 | -9.8% | -5.9% |

Source: Gross National Income: Current price: Seasonally adjusted £m, ONS, 31 March 2021. link and Gross Domestic Product: chained volume measures: Seasonally adjusted £m, ONS, 31 March 2021, link.

A DFID/FCDO official acknowledged to us that one of the lessons from 2020 is the need, in times of economic volatility, to make use of a variety of GDP forecasts and to plan around different scenarios, rather than single-point estimates, and to be mindful of fluctuating inflationary pressures. HM Treasury and FCDO informed us that they did in fact monitor GDP estimates from other sources. HM Treasury

indicated that they considered there were good reasons for using the OBR April scenario to inform the ‘reasonable worst case’ scenario, but did not elaborate on what these were. After the cross-government reprioritisation exercise, DFID/FCDO monitored ODA spending against a range of possible GNI outcomes, rather than a single projection, although officials still used OBR figures.

As it transpired, GNI did not decrease by the forecast amount. On 14 July, five days after the Star Chambers reprioritisation process concluded, OBR produced three scenarios for nominal GDP growth (upside, central and downside), allowing a range of ODA spending targets to be produced. All these scenarios were higher than the £13.3 billion target used for the reprioritisation exercise, which had been based on the OBR’s April real GDP growth figures. If the government had taken steps to adapt its reprioritisation strategy in light of the July forecasts, it would have had more choices and might have been able to avoid reducing departmental budgets as much as it did.

Efficiency: How well were value for money risks mitigated?

The reprioritisation processes allowed the government to achieve its aim of reaching a reduced ODA spending target set in year,52 and in the face of great uncertainty, while spending £1.39 billion in resources for the global COVID-19 response. However, there are inherent value for money risks in reprioritising expenditure at such a scale and speed in the middle of the year. Good financial management principles

suggest that annual budgets should be prepared with due care, to avoid the need for large changes during the year. If changes do need to be made, attention should be given to mitigating the risks. In this section, we explore how well the risks were managed.

Several robust approaches were taken by government to adjust spend to reach the 0.7% target. First, the departments continued to make good use of flexibility in the timing of multilateral payments to offset the uncertainty surrounding UK GNI and aid expenditure. Because of its pooled nature and the business model that underpins it, multilateral aid is inherently better placed to manage flexibility in payments

than bilateral programmes, without disruption to aid delivery. The departments communicated their intentions to multiple partners at an early stage and throughout the process, which helped them to manage the uncertainty. We noted during the review that some DFID/FCDO missions managing humanitarian programmes were equally able to flex spend in 2020 without adversely impacting value for money.

Second, during the reprioritisation process, departments examined their aid programmes in detail to identify where planned activities had in any case been disrupted by the pandemic, and where expenditure could be deferred into 2021 without practical impact. They also identified opportunities to reallocate budgets within existing programmes towards the COVID-19 response. In ICAI’s information note on the government’s management of procurement during the reprioritisation, we noted that, before the merger, both DFID and the FCO demonstrated a good level of flexibility in determining the best way to adapt individual programmes and contracts with implementing partners in order to minimise disruption. Particular attention was paid to avoiding cutting programmes that were close to completion,

recognising that value for money gains are often realised in the last years of programming, on the back of investments made in previous years.

Third, cross-government coordination processes for the aid programme were stepped up in response to the pandemic. This enabled strategic decisions to be made across the 17 aid-spending departments and funds, rather than asking each to pursue parallel reprioritisation processes.

There were also a number of areas where new processes were introduced to accommodate the exceptional circumstances of the pandemic, such as setting up the IMIG and focusing on vulnerable countries.

However, decisions were also taken which increased value for money risk. In our earlier review of the management of the 0.7% ODA spending target, we noted that the government’s interpretation of the ODA spending target as both a floor and a ceiling with a very narrow margin for error was overly rigid (compared to other donors) and posed more challenges in times of significant shock – a finding also commented on by the OECD DAC in its peer review55 and noted in its recent publication of preliminary ODA statistics for 202056 (see also Table 2 and Table 3). Other possibilities for managing the 0.7% target, such as shifting to a 0.7% target based on a two- or three-year GNI average that would have enabled the cuts to be planned over a longer period, were not pursued.

There were shortcomings in the GNI estimates used for projecting the ODA spending target. Given the unprecedented level of uncertainty around GNI estimates in the early months of the pandemic, we would have expected to see the responsible departments planning around a range of GNI scenarios. Instead, a single-point and outdated estimate was used to inform a ‘reasonable worst case’ scenario on which the reprioritisation process was based. As it transpired, the estimate relied upon was particularly low and was quickly superseded by more optimistic forecasts. Because this low estimate was used, the cuts were deeper than they needed to be.

Through the Star Chambers process, the government adopted a ‘cut once, cut deep’ approach. All the cuts to bilateral programmes were identified, based on proposals prepared by the departments, within a short period of time in July, and were not revisited. The amount of bilateral cuts was broadly delivered as planned.

In value for money terms, there were pros and cons to the approach taken at Star Chambers. Early and deep cuts minimised the risks that the spending target would be overshot. This also minimised the risk that additional cuts would be needed late in the year, when time and options

to adjust bilateral spend would have been more constrained. On the other hand, it meant that the cuts were made at a point of significant uncertainty. In minimising its risks of overshooting the target, the government also increased the likelihood that the cuts would prove to be more drastic than needed.

Analysis of published outturn data indicated that actual year-on-year reductions in DFID/FCDO’s bilateral spend in 2020 remained largely unchanged from the planned adjustments agreed at Star Chambers (at £700 million) (see Figure 5).

It is notable that by the time the prime minister approved the final package of cuts on 20 July, updated GNI assessments were already available suggesting that cuts of that magnitude might not have been necessary, although these new estimates still included significant uncertainty.

Figure 5: Estimated reductions in DFID/FCDO’s planned* and actual** multilateral and bilateral official development assistance spend

‘Planned’ adjustments are those confirmed at the summer reprioritisation exercise. Planned multilateral adjustments were identified in July 2020 for use if required. ** ‘Actual’ reductions are computed from published Statistics on International Development 2020 data (Table 3 and Table C3) and Statistics on International Development 2020 data (Table 10)

Source: HM Treasury Technical Note issued to DFID/FCDO, July 2020, and Statistics on International Development: Provisional UK Aid Spend 2020, FCDO, April 2021, link.

Conclusions and recommendations

The extreme volatility reflected in 2020 GNI forecasts, and the timing of updates, made managing towards a moving (fixed percentage GNI-based) target demanding.

In spring 2020, DFID/FCDO moved quickly to reprioritise spending and focus staff resources on delivering the UK’s ambitious global response to COVID-19.

The summer 2020 reprioritisation process achieved its objective of identifying potential reductions of £2.94 billion across the aid programme, through a combination of underspend in ongoing programmes (linked to COVID-19 delivery constraints), permanent cuts and deferrals of planned expenditure into 2021. At the same time, DFID/FCDO succeeded in creating space for £1.39 billion funding for the global COVID-19 response. Meeting the aid target in these circumstances, and in the face of so much economic uncertainty, was a considerable achievement.

Established cross-government governance arrangements and departmental ODA management systems and processes proved resilient, and there were governance gains in the way these were adapted torespond to COVID-19 and volatile GNI. The centrally managed Star Chambers reprioritisation strategy and process strengthened strategic scrutiny of UK ODA spending across departments to some extent.

However, the government’s chosen approach to ‘cut once, cut deep’, based on single-point and outdated GNI forecasts, had unintended value for money consequences for bilateral ODA programmes and UK ODA overall that might have been avoided. Moving decision making about portfolio and programme adjustments away from those closest to the details of the programmes also heightened value for money risk.

ICAI has not had access to the departmental submissions, detailed proposals or confirmed programme adjustments agreed at the Star Chambers process. We were therefore unable to assess how the various reprioritisation criteria were applied in practice. Value for money was reportedly considered by officials when assessing the trade-offs involved in reducing expenditure across programmes, but without

clear criteria or detailed analysis. The lack of a common method for factoring value for money into the reprioritisation was a shortcoming in the process. Overall, we observed that using prescriptive reprioritisation processes and criteria to frame reprioritisation exercises will only be able to support decision making in a limited way.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: To inform decision making on ODA spend throughout the year, departments responsible for managing UK ODA should use a range of GNI forecasts, calculated by a range of methods and provided by a number of reliable economic commentators (including, though not limited to, the OBR).

Problem statements

- Narrow focus on single-source, single-point, outdated GNI forecasts in the face of an extreme economic shock can prompt risk-averse ODA management strategies that adversely impact portfolio-level value for money.

- The unexpected anomaly around the GDP deflator that materialised in 2020, which could also appear in future, complicates the interpretation of nominal GNI forecasts which in turn impact the setting of the aidspending target.

- Because of the way the economy adjusted to the COVID-19 shock, GDP proved to be a less reliable proxy for GNI in 2020 than in 2019, and the reasons for this need to be considered for future monitoring.

Recommendation 2: FCDO should build options for flexing spend into country portfolios and plans, incorporating programme activities that could be scaled up or down in response to external shock, with minimal impact on value for money.

Problem statements