The UK’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative

Score summary

The Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative is an important body of work on a neglected topic but falls short of the government’s stated ambitions. It lacks an overall strategy and adequate mechanisms for meaningful survivor inclusion. Results reporting and learning activities are weak.

Conflict-related sexual violence is a common feature of modern conflict, with devastating impacts on survivors, their communities and prospects for building lasting peace. Aiming to galvanise action on this issue, in 2012 the UK government launched the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI), a cross-departmental initiative led by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO).

In 2014, the then foreign secretary, William (now Lord) Hague, co-hosted the high-profile Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict with Angelina Jolie, Special Envoy to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The summit ended in a commitment by the foreign secretary to move from pledges to practical action to end conflict-related sexual violence. That same year, the PSVI launched its International Protocol on Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict, which has since been used in a range of conflict and post-conflict settings to aid the investigation and prosecution of perpetrators of sexual violence. This review assesses PSVI activities since the 2014 Global Summit, investigating how the UK government has followed up on its Summit commitments on preventing sexual violence, supporting survivors and promoting justice and accountability.

The Initiative benefited initially from strong political leadership, but after the departure of Lord Hague in mid-2014, leadership moved from the level of foreign secretary to special representative. Ministerial interest waned and the PSVI’s staffing and funding levels dropped precipitously during this time. The Initiative has no overarching strategy or theory of change, and programming has been fragmented across countries and between the three main contributing departments, the FCO, the Department for International Development and the Ministry of Defence.

Survivors call for long-term interventions that address the deep-rooted causes and effects of sexual violence. However, most PSVI projects are subject to the FCO’s one-year funding cycles, often obliging implementing partners to focus on symptoms and short-term fixes. There is little room for meaningful inclusion of survivors in programme design, and inadequate ethics protocols and monitoring mechanisms pose risks that projects may cause inadvertent harm. Despite the lack of rigorous requirements and monitoring by PSVI, many projects run by implementing partners have been innovative and useful, building on strong local networks.

The Initiative lacks a system for monitoring, analysing, sharing or storing results information, and learning is ad hoc rather than part of a systematic learning approach. This hinders learning both internally and externally in a field that suffers from a dearth of evidence.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Relevance: Does the portfolio demonstrate a credible approach to preventing sexual violence in conflict and meeting the needs of survivors, as well as meeting the objectives and pledges set out at the 2014 Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict? |  |

| Question 2 Effectiveness: How well have the programmes delivered on their objectives as well as the overall objectives of the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative? |  |

| Question 3 Learning: How have responsible departments generated and applied evidence on what works on sexual violence in conflict? |  |

Key terms and acronyms

Executive summary

“There is a village where almost all the women are survivors, or at least 70% of the village.”

– Survivor, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Sexual violence is pervasive. In conflict-affected settings, both the frequency and severity of sexual violence intensifies. Despite being punishable by international human rights and humanitarian law, sexual violence remains rife in most modern armed conflicts. These experiences have devastating and life-changing impacts on survivors and their communities, and make it harder to achieve lasting peace.

After long neglect, recent years have seen vocal campaigns to encourage the international community to prevent conflict-related sexual violence, support survivors in rebuilding their lives, and punish perpetrators. The UK government has been at the forefront of efforts to galvanise support for an international campaign to address conflict-related sexual violence. In 2012, the government launched its Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI), championed by the then foreign secretary, William (now Lord) Hague, and Angelina Jolie, Special Envoy to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. In 2014, the two hosted the high-profile – and first ever – Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict. The summit gathered an unprecedented 1,700 high-level delegates, including politicians, celebrities, survivors and their supporters at grassroots organisations, international organisations, and experts from civil society from across the world. Following the summit, 113 states endorsed the UN Declaration of Commitment to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, a number which has now risen to 156 UN member states.

The UK government planned a further international conference to take place in November 2019, five years on from the Global Summit, but this was subsequently postponed due to the 2019 general election. It is ICAI’s intention that this review of the government’s PSVI activities to date should feed into discussions at any rescheduled conference and beyond.

The Initiative is led by the PSVI team, which sits in the Gender Equality Unit at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) in London, under the leadership of the Prime Minister’s Special Representative for Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict, Lord Ahmad. The Initiative was intended to be an FCO-led tri-departmental effort involving the FCO, the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Ministry of Defence (MOD).

This review assesses the credibility of the Initiative’s objectives and approach, and its effectiveness in delivering on these objectives. We gave special attention to how PSVI projects meet the needs of survivors, looking for evidence of meaningful inclusion. Finally, we examined the Initiative’s evidence generation and application of learning. Assessment was undertaken through a series of remote and field-based case studies, document reviews, and interviews with UK government representatives, donors, and survivors and their supporters at survivor-led organisations.

Relevance: Does the portfolio demonstrate a credible approach to preventing sexual violence in conflict and meeting the needs of survivors, as well as meeting the objectives and pledges set out at the 2014 Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict?

The Initiative benefited initially from strong political leadership, driving a range of activities, foremost among which was the influential 2014 Global Summit which helped set the global agenda on sexual violence in conflict. Indeed, throughout the review period, FCO-led influencing activities at global and country level have been an important part of the Initiative, convening countries around the need to address conflict-related sexual violence and setting international standards. This review focuses mainly on the programming aspects of the Initiative, assessing progress on commitments made at the Summit.

Following Lord Hague’s departure from the post of foreign secretary soon after the Global Summit, high-level ministerial interest waned, and funding and staffing levels for the PSVI team were reduced. The impact of this was compounded by the fact that, from the beginning, there was no strategic vision or plan driving the work of the Initiative.

Instead of a strategic plan, the Initiative is directed by short ‘core scripts’ and the overall guidance from the government’s National Action Plan on Women, Peace & Security. However, these documents do not offer an adequate framework from which to develop a coherent approach to programming and to lead cross-departmental efforts on the specific challenges of conflict-related sexual violence.

The Initiative is loosely organised around three thematic ‘strands’: justice and accountability, stigma, and prevention. Each department and in-country team is left to interpret the Initiative in line with their own strategic priorities rather than through a unified cross-departmental strategy and concrete objectives. While the PSVI is a notable initiative in a field generally neglected by donors, the level of effort and funding that the UK government has applied to addressing conflict-related sexual violence is modest and has decreased each year.

Overall, we find that the UK government’s approach to preventing conflict-related sexual violence falls far short of the ambition and commitments set out at the 2014 Global Summit. Because of this, we have given the Initiative an amber-red score for relevance.

Effectiveness: How well have the programmes delivered on their objectives as well as the overall objectives of the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative?

The UK government’s investments and interventions are modest, but nevertheless significant in a field where few other donors are engaged. The International Protocol on Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict is the main achievement of the Initiative since 2014. It establishes a set of evidentiary and prosecutorial standards and best practices to help survivors overcome the barriers to pursuing justice. The protocol has been used in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burma, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Syria, Uganda and Iraq. It has helped secure convictions in several countries and is almost universally praised as a document which has practical use at grassroots, institutional and international levels.

Through its implementing partners, the Initiative has worked mainly through well-established networks of local civil society organisations (CSOs). The Initiative’s implementing partners have mainly met their stated output objectives – with targets such as training and workshop participation, service delivery and activity goals. They have also impressively navigated tight timelines, small budgets and the uncertainty created by the PSVI’s reliance for the most part on short one-year funding cycles. While output reporting clearly illustrates the achievement of PSVI partners, evaluating the impact of PSVI-funded projects is difficult given that partners are not required to track progress towards sustainable outcomes, such as changes in attitude and behaviour changes at community level.

Survivors consistently call for long-term programming that addresses the deep-rooted causes and effects of conflict-related sexual violence in ways that would allow them to move beyond simply surviving. DFID, the FCO and the MOD agree that long-term programming is needed, but many PSVI projects were obliged to focus on symptoms rather than causes and long-term effects because of the FCO’s one-year funding approach. While this funding approach increases access for smaller CSOs and those developing innovative programmes, it does so at the expense of survivors’ stated needs and lasting impact.

With some exceptions, such as the appointment of survivor champions to advise the London team, the PSVI’s mechanisms to ensure that survivors are meaningfully included in the choice, design and implementation of projects, and that the principle of ‘survivor wellbeing’ guides all activities, are not robust. This runs counter to the Initiative’s stated goal of survivor inclusion and global best practice for addressing sexual violence, in conflict-affected settings or otherwise. Importantly, this also increases the risk that programming inadvertently causes harm to survivors.

While the Initiative has been a leading voice in the effort to address conflict-related sexual violence, there is considerable room for improvement. We have given the Initiative an amber-red score for effectiveness.

Learning: How have responsible departments generated and applied evidence on what works on sexual violence in conflict?

Eight years after its launch, the PSVI lacks a system for monitoring, analysing, sharing or storing information, including on progress towards project outcomes. There is no requirement to provide evidence of pre-project planning in the form of needs assessments, conflict analyses, survivor consultations, or ‘do no harm’ appraisals in funding applications or business cases.

Apart from one-off reports, the Initiative has very limited evidence on the results of its work. This inhibits learning both internally and externally in a field that already suffers from a dearth of evidence. Learning events have been convened, but partners, donors, survivors, and representatives across DFID, the FCO and the MOD have all acknowledged that there needed to be more learning activities and opportunities for the sharing of learning, whether across country contexts, between country teams and the central PSVI team, between UK government departments, or with external stakeholders. We therefore award the Initiative a red score for learning.

Conclusion and recommendations

The PSVI is an important initiative on a neglected topic. However, its levels of ambition, funding and activity have been reduced rather than increased since the 2014 Global Summit, and cross-departmental collaboration has been poor. To continue and to strengthen its work on conflict-related sexual violence, the Initiative must develop a clear oversight structure and strategy, and robust monitoring, reporting and learning mechanisms.

Recommendation 1: The UK government should ensure that the important issue of preventing sexual violence in conflict is given an institutional home which enables both full oversight and direction, while also maximising the particular strengths and contributions of each participating department.

Recommendation 2: The UK government should ensure that its programming activities on preventing sexual violence in conflict are embedded within a structure which supports effective design, monitoring and evaluation, and enables long-term impact.

Recommendation 3: The UK government should ensure that its work on preventing conflict-related sexual violence is founded on survivor-led design, which has clear protocols in place founded in ‘do no harm’ principles.

Recommendation 4: The UK government should build a systematic learning process into its programming to support the generation of evidence of what works in addressing conflict-related sexual violence and ensure effective dissemination and uptake across its portfolio of activities.

Introduction

Sexual violence is a common feature of most modern armed conflicts, with devastating and life-changing impact on survivors and their communities. Sexual violence is often pursued as a tactic of war to displace or control whole communities, as seen recently in the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In Iraq, sexual slavery was a central piece of ISIS’s genocidal campaign against the Yazidi community. In other conflict-affected settings, sexual violence can be more opportunistic in nature, perpetrated by members of armed groups who take advantage of the general lawlessness in fragile and stateless zones.

“Often, 27 years later there are no visible damages, but victims stay in deep trauma and poverty.”

– Leader of civil society organisation, Bosnia and Herzegovina

“[The] country does need a future, but the past still poses a burden.”

– Survivor, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Conflict-related sexual violence is a crime punishable under international human rights law, international humanitarian law and international criminal law. Even with these legal instruments at the disposal of the international community, conflict-related sexual violence is perpetrated with almost total impunity. Latent trauma, stigma, and the fear of being ostracised by their communities, silences survivors. As a result, conflict-related sexual violence is vastly under-reported. For those who do speak out, very few receive the support they need or the justice they seek. In the words of UN Secretary-General António Guterres, “most survivors of conflict-related sexual violence face daunting social and structural reporting barriers that prevent their cases from being counted, much less addressed”.

The effects of conflict-related sexual violence are lasting and multigenerational. Individual survivors and whole communities carry the emotional and physical scars of sexual violence, which makes it more difficult to stabilise conflicts and build lasting peace. After long neglect, recent years have seen vocal campaigns to engage the international community in prioritising efforts to prevent conflict-related sexual violence, support survivors in rebuilding their lives, and punish perpetrators. In the words of Nadia Murad, 2018 Nobel Peace Prize laureate and a survivor herself, the aim is to say:

“No to exploiting women and children, yes to providing a decent and independent life to them, no to impunity for criminals, yes to holding criminals accountable and to achieving justice.”

Nadia Murad, Nobel Peace Prize lecture, Oslo, 10 December 2018

The UK government has been at the forefront of efforts to galvanise support for an international campaign to reduce and prevent conflict-related sexual violence. In 2012, it launched the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative (PSVI). The Initiative was championed by the then foreign secretary, William (now Lord) Hague, and the Special Envoy of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Angelina Jolie. In 2014, as part of the Initiative, the UK hosted the high-profile – and first ever – Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict.

The Global Summit enjoyed high-level support from politicians, celebrities, and grassroots organisations. It gathered governments, international organisations, experts from civil society, and survivors from across the world. The summit, co-chaired by Lord Hague and Ms Jolie, was accompanied by events around the world that sought to amplify survivors’ voices and emphasise the urgent need for action. The summit aimed to “break the international silence” and help “generate the long-overdue international political will necessary to end acts of sexual violence in conflict”. The Global Summit led to a range of pledges by participants. In the post-summit report, Lord Hague committed the Initiative to moving on to practical action to implement these pledges.

“We believe the time has come to end the use of rape in war once and for all, and we believe it can be done.”

– Lord Hague, foreword to the post-summit report, 2014

The aim of this ICAI review is to assess PSVI activities since the 2014 Global Summit, to investigate how and to what degree the UK government has followed up on its commitments and ambitions set out at the summit. The review builds on the House of Lords’ 2016 report Sexual Violence in Conflict: A War Crime, and responds to that report’s call for an evaluation of the Initiative. In its report, the House of Lords lauded the Initiative and the Global Summit, but noted that the government needed to demonstrate its continued commitment now that the summit was over. They warned that the Initiative must “set out the strategic goals and [an] operational plan for the Initiative – without this, momentum will be lost”. The House of Lords noted the need for high-level political leadership, sufficient resources and strengthened coordination of the cross-government effort.

Five years on from the Global Summit, in November 2019, the UK government planned to convene another international conference on the topic, but this was subsequently postponed due to the 2019 general election. Titled Time for justice: putting survivors first, it aimed to forge agreement among international partners on actions to strengthen justice for survivors and to mobilise various stakeholders, including community and faith leaders, to address the stigma attached to survivors and children born as a result of sexual violence. It is our hope that this review, in assessing whether the UK has delivered on the promise of the Initiative, will help shape discussions at any rescheduled conference and aid the Initiative in strengthening its approach as it continues this important work to end conflict-related sexual violence.

Box 1: How this report relates to the Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

Related to this review:

![]()

Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. The Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative aims to raise awareness of the extent of sexual violence against women, men, girls and boys in situations of armed conflict and rally global action to end it. It can therefore play an important role in achieving SDG 5.

This review assesses the relevance and effectiveness of the PSVI portfolio, focusing on global as well as country-specific programming, along with the Initiative’s approach to learning. It explores what progress has been made on the commitments to reduce stigma for survivors, to increase justice and accountability, and to increase preventative efforts since the 2014 Global Summit.

Table 1: Review questions

| Review criteria | Review question |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance | Does the portfolio demonstrate a credible approach to preventing sexual violence in conflict and meeting the needs of survivors, as well as meeting the objectives and pledges set out at the 2014 Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict? |

| 2. Effectiveness | How well have the programmes delivered on their objectives as well as the overall objectives of the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative? |

| 3. Learning | How have responsible departments generated and applied evidence on what works on sexual violence in conflict? |

The review uses the UN definition of conflict-related sexual violence, to include: “rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilization, forced marriage and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, girls or boys that is directly or indirectly linked to a conflict”.

A separate ICAI report on sexual exploitation and abuse

Sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) in peacekeeping is a form of conflict-related sexual violence. However, like the UN, the UK government addresses the issue of sexual exploitation and abuse perpetrated by peacekeeping forces, including the military and police, and civilian staff of peacekeeping missions, through a different set of teams and policies. The ICAI review team conducted a joint review of the UK government’s work on PSVI and SEA. Our findings are presented in two separate but related reports, of which this is the first and main report.

Methodology

The research for this review was conducted jointly with ICAI’s forthcoming review on sexual exploitation and abuse in peacekeeping contexts. The methodology was developed to cover both reviews, given the overlapping nature of the two issues. In this section, we focus on the methodological components relevant for the PSVI review. However, where the two issues benefit from being assessed together, we have not separated them. As an example, the literature review produced for this report covers both conflict-related sexual violence and the issue of sexual exploitation and abuse in peacekeeping operations as a particular subset of conflict-related sexual violence.

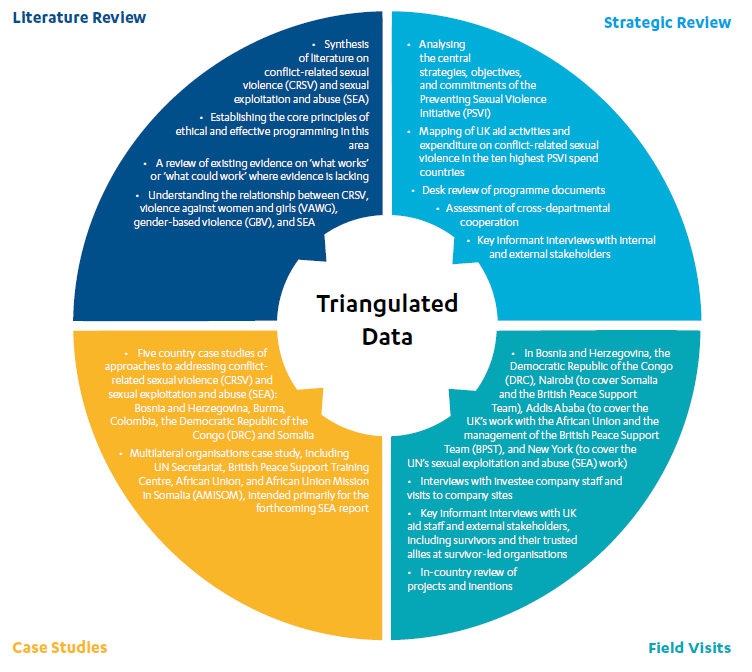

To allow for a robust level of data triangulation, the review team relied on four methodological components (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Methodological approach

Literature review – The literature review summarises existing academic and practitioner literature on conflict-related sexual violence, offering a set of suggestions on how programming might more effectively address this issue. It reviews empirical evidence on what works, or – since evidence and data in this field are often weak – what might work in addressing conflict-related sexual violence.

Strategic review – Based on key informant interviews and a desk review of key documents and programme materials, the strategic review served the following purposes: (a) analysing the central strategies, objectives and commitments framing the UK’s efforts to address conflict-related sexual violence, (b) mapping the government’s aid activities and expenditure on conflict-related sexual violence in the ten countries where the Initiative invested the most financial resources (an estimated 85% of total country-level expenditure during the review period), and (c) assessing cross-departmental coordination on this topic.

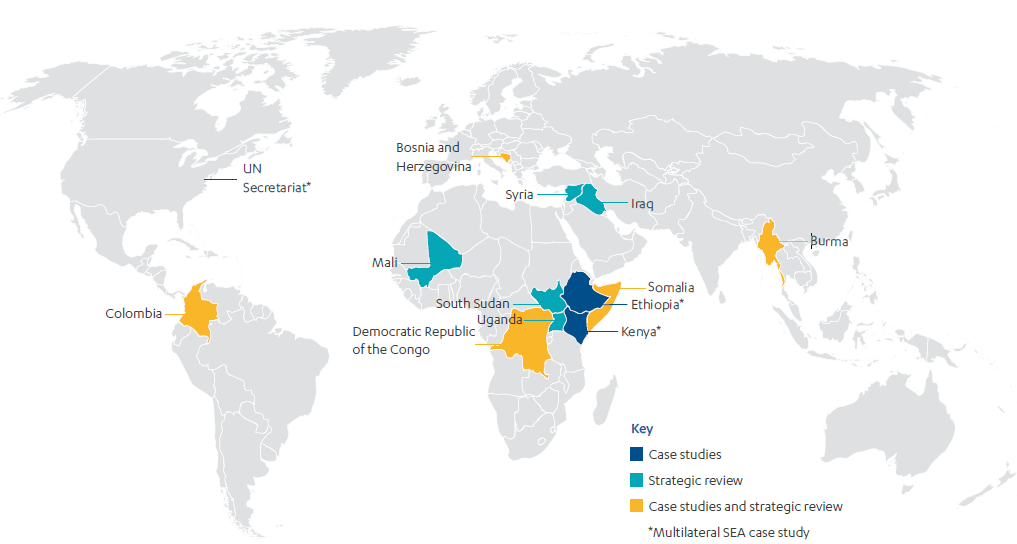

Case studies – We conducted five country case studies – of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burma, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Somalia – and one case study on multilateral organisations. The country case studies were selected based on the following criteria: (a) among the top ten countries for PSVI-related spending, with a breadth and diversity of programming, (b) the severity of the problem of conflict-related sexual violence (historically or present), (c) evidence of both centrally managed programming and programming led by in-country teams, and (d) diversity of conflict settings, as the characteristics and prevalence of conflict-related sexual violence vary widely from conflict to conflict. Figure 2 shows the countries covered.

The country case studies consisted of desk reviews of country and programme documents, and phone interviews. In addition, we conducted field research in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the DRC and Kenya (covering Somalia). We did not travel to Somalia, but conducted interviews in Nairobi, where most relevant UK government and many other stakeholders are based due to the security situation in Somalia. Field visits allowed ICAI to triangulate evidence from the strategic review and desk studies through key informant interviews with DFID, FCO and MOD staff and consultations with national and international stakeholders, implementing partners, civil society organisations, and survivors and survivor-led organisations. Finally, we visited the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa and the UN Secretariat in New York, although the research conducted during these trips was most relevant to the forthcoming ICAI review on sexual exploitation and abuse by international peacekeepers.

We conducted 114 interviews with key stakeholders and assessed over 400 programme and project documents, covering 149 PSVI-related projects, at central and country level. The research covered programming by the FCO, DFID and the MOD, although delineating where PSVI programming begins and ends was a challenge (see Box 2 below).

Figure 2: Country overview

The protection of vulnerable people is central to all ICAI reviews. The meaningful inclusion of survivors’ perspectives was especially important for this review. Protocols were therefore established to ensure that vulnerable participants were fully informed, protected and able to offer consent before, during and after interviews.

Box 2: Limitations to our methodology

It was a challenge to map the nature and size of the UK government’s PSVI programming. Beyond the funding managed by the PSVI team in London, many country teams also manage PSVI-related programmes. Funding for these programmes comes from many sources, with different reporting mechanisms, and no department or team has a full overview of the Initiative’s portfolio of programmes or spending. We therefore conducted our own mapping of the ten countries where the most financial resources have been invested in addressing conflict-related sexual violence.

However, since different departments and country teams have different interpretations of what constitutes PSVI-related activities, clearly delineating expenditure that was and was not intended for PSVI projects was a challenge. In particular, DFID’s portfolio is not organised or categorised around the concept of conflict-related sexual violence, instead focusing on wider violence against women and girls (VAWG) programmes. Because of this, accurately mapping DFID’s contribution to PSVI has presented considerable challenges. The review team liaised with DFID’s Violence Against Women and Girls team to identify related programming. It was not possible, however, for DFID to provide a breakdown of the budgets for VAWG programmes that included some (in most cases small) components relevant to conflict-related sexual violence. The categorisation and aid management platform used by DFID does not classify which programme components and budgets specifically relate to conflict-related sexual violence, or PSVI. Thus, while we had enough information to assess DFID’s contributions, we have not been able to estimate the monetary value of DFID’s efforts in this area.

Background

In 2000, the UN Security Council recognised the growing severity of conflict-related sexual violence and its grave impact not only on survivors, but also on peace and security. And yet action from the international community remained limited. In 2012, the UK government launched the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative in response to the ongoing neglect of this important issue.

As the literature review for this report notes, there is a lack of firm data on the prevalence and trends of conflict-related sexual violence. For instance, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, “22 years on from the end of the fighting, and despite being the most thoroughly investigated conflict to date in terms of sexual violence, there are still no reliable estimates of the numbers of victims of sexual violence either male or female.” Inconsistent and evolving definitions of conflict-related sexual violence have added to the challenge of collecting information on prevalence.

Survivors are clear, however, that the defining feature of conflict-related sexual violence is context – in other words the presence or legacy of conflict. One survivor in Nairobi, Kenya, explained that “in conflict, people take advantage. There is a breakdown of order and anyone can take advantage.” Conflict-related sexual violence is unique not necessarily because of the type of incident or perpetrator, but because conflict itself increases impunity and the frequency and severity of preexisting harmful norms around the treatment of women and girls. Sexual violence is exacerbated by conflict, with perpetrators ranging from intimate partners to armed groups. Indeed, intimate partner violence remains the most common form of sexual violence both within and outside conflict-affected communities, but the presence of conflict can and does increase the prevalence. In addition to exacerbating pre-existing patterns of sexual violence, conflict can also lead to forms of sexual violence that are more unique to conflict settings, such as the use of mass and gang rape as a war tactic or sexual violence against both female and male political opponents in detention to humiliate them and break their spirit.

Core principles underpinning programming to address conflict-related sexual violence

Specific drivers and characteristics of sexual violence vary greatly between conflict-affected settings. For instance, in the North and South Kivu provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), gang and mass rape is used by local militias to subdue populations and control the illicit extraction of natural resources. In Yemen, on the other hand, while a “few cases are directly attributable to parties to the conflict, most are the result of increased risks that women and children face, against a backdrop of pre-existing gender inequality, exacerbated by the chronic incapacity of Government institutions to protect civilians”. A localised approach to programming is therefore required, built on an assessment of the drivers, motivations and forms of sexual violence particular to that specific conflict setting.

While there is a limited body of evidence on what works in programming to address conflict-related sexual violence, there is nevertheless agreement on the need for all programming to centre on survivor wellbeing. Described in more detail in Box 3, this approach demands that survivors are not just consulted by development practitioners but enlisted as co-architects of the programmes and projects in which they participate. Survivors explain that the best approach for their wellbeing involves comprehensive programming that targets short-term urgent care in addition to multi-sector long-term assistance aimed at building resilience.

Box 3: The primacy of survivor wellbeing

An approach based on survivor wellbeing focuses on survivor resilience and offering a sense of closure to traumatic events. This approach supports survivors in rebuilding their lives and reintegrating into their community. It includes urgent medical care, livelihood support, mental health services, legal aid and a variety of other forms of support that survivors want and need to move beyond merely surviving in their communities. An approach based on survivor wellbeing does not presume to know exactly what survivors need. Survivors’ participation in the design of the programmes in which they participate is paramount.

“When you are a victim and you’ve been taken care of ‘holistically’, I would say that you’re 50% cured, but if there’s no economic support, you’re not going to be okay … If we could have funds for children born of rape, if we could take care of some survivors that want to study by paying for their medication or their studies. Some victims need housing because they have been abandoned by their families and do not have any shelter.”

– Survivor-led CSO, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Overview of the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative

The UK government’s Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative is a combination of influencing efforts and programmes to tackle the issue. The influencing effort pushes for international action on the issue of conflict-related sexual violence through the G7, the UN and “champion countries”. This international campaign was not the focus of this review. The initiative is led by the PSVI team sitting in the FCO’s Gender Equality Unit, under the leadership of the Prime Minister’s Special Representative for Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict. It is set up as an FCO-led cross-departmental effort, with the FCO, DFID and the MOD as the main contributing departments. In addition to the central PSVI team at the FCO, the FCO’s PSVI Team of Experts is managed by the Stabilisation Unit within the Civilian Stabilisation Group. This Team of Experts was originally managed and funded by the PSVI team at the FCO, but now sits in the cross-government Stabilisation Unit.

Determining the scope and nature of the UK government’s PSVI portfolio of programming that addresses conflict-related sexual violence is not easy (see also Box 2 in the methodology section). The government does not have an overview of its programming in this area. Our strategic review included a wide range of projects – those managed by the PSVI team in London, country-based projects labelled as ‘PSVI projects’ by in-country teams (which we checked and verified as being focused on addressing conflict-related sexual violence), and projects managed by DFID and the MOD (both centrally managed and country-based) – undertaken by London teams or implemented in the ten countries with the highest PSVI expenditure.

Assessing the expenditure on PSVI-related programming is extremely complicated, as many projects, especially those managed by DFID and the MOD, include conflict-related sexual violence as one of several components and do not break down budgets to show how much was spent on PSVI-related activities. The analysis that follows reflects what we refer to as the PSVI portfolio in the top ten destination countries for PSVI spending. To reach this point, we solicited PSVI programme and spending information from the FCO, DFID and the MOD at the central level. We also requested programme documents for each of the ten countries that utilised the most PSVI spending. A detailed review of all data resulted in a list of 114 programmes directly linked to the Initiative in the 2014-19 period, which can be described as the PSVI portfolio. Those programmes not directly linked to PSVI were left out of the analysis depicted below, so as to not distort the analysis. In the end, the figures below do not include expenditure by DFID or the MOD, since neither department was able to provide a breakdown of spending on the PSVI-related components of larger programmes. The figures provided below therefore only include funding channelled through the central PSVI team in London and PSVI-specific spending largely led by FCO in-country teams, with the occasional support of DFID in-country teams.

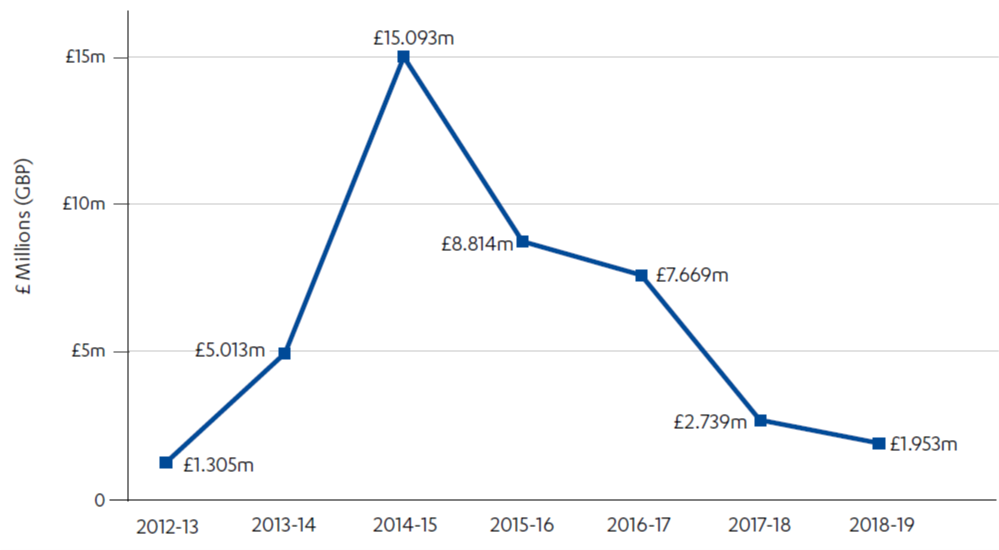

Spending by the central PSVI team in London

Since the 2014 Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, roughly £34 million has been spent by the PSVI team in London on a range of programmes and projects in 24 countries. Some of this funding has also gone to support UN and other influencing activities such as conferences, campaigns or film festivals. The PSVI team’s budget peaked in 2014-15 at £15 million. Since that time, their budget has precipitously fallen. For the fiscal year 2018-19, the PSVI London team recorded a budget of just under £2 million.

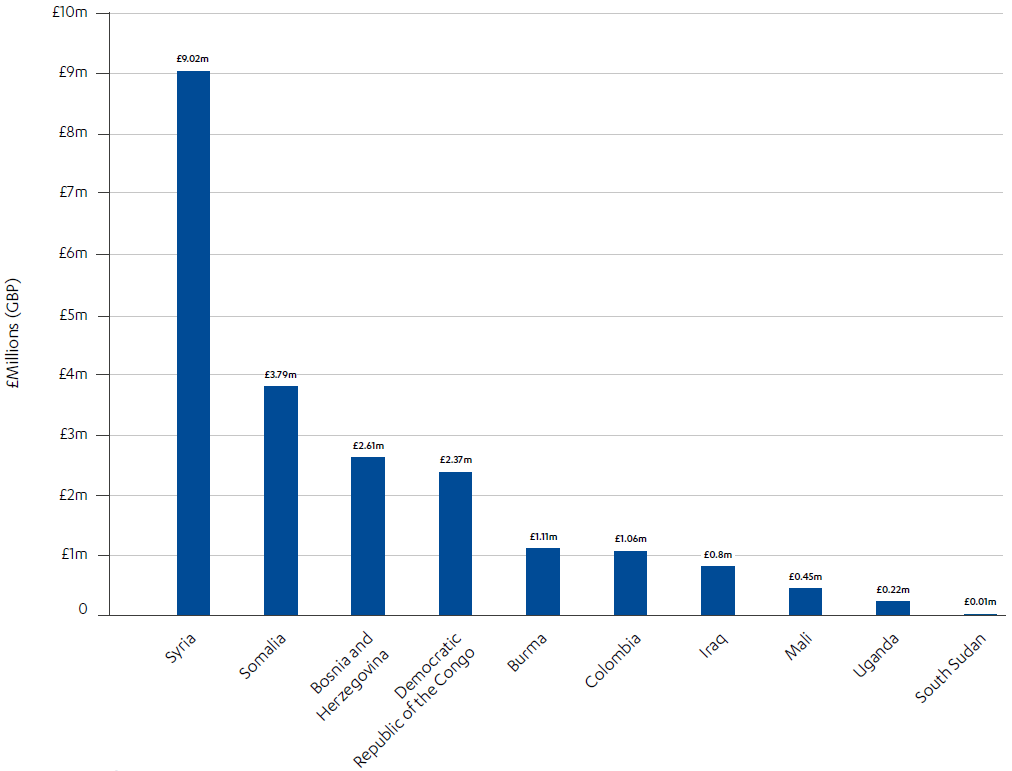

Figure 3: PSVI spending in-country in the top-ten spending countries

PSVI spending in country

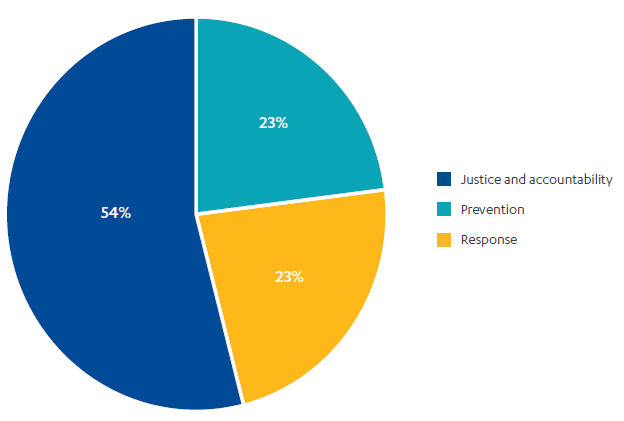

In addition to the funds centrally managed by the PSVI team in London, FCO country teams bid directly for support from funds like the Global Britain Fund and the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund, or allocate portions of their discretionary budgets (the Ambassador’s budget) to PSVI projects. These are not counted in any database maintained by the PSVI team in London. Our own mapping of PSVI interventions led to a list of 114 PSVI interventions in the ten top-spending countries from 2014 to present, with a total budget during that period of roughly just over £21 million. Figure 3 above shows how this £21 million has been spread over the ten countries. Of the £21 million, the majority has been allocated to justice and accountability activities (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: PSVI budget per thematic area in the top-ten spending countries

In some of the ten countries, DFID is contributing to the prevention of, or response to, conflict-related sexual violence through its programming on violence against women and girls (VAWG) and humanitarian emergencies. In the DRC, Somalia, South Sudan and Syria, DFID runs large humanitarian, health care, education, and protection programmes, some of which target structural issues leading to gender-based violence. While these conflict-related VAWG programmes do not fall under the FCO budget used by in-country teams for PSVI programming, or the PSVI portfolio visualised in the figures above, we did review all of DFID’s PSVI-relevant activities in the ten countries.

The MOD supports the PSVI through the training it provides to British and international troops on issues related to conflict-related sexual violence, funded mainly through the cross-departmental Conflict, Stability and Security Fund. This includes a series of training programmes for African peacekeepers provided by the British Peace Support Teams in Eastern and Southern Africa. Issues of conflict-related sexual violence are only one part of these training programmes. Importantly, this training is not replicated widely throughout the MOD. Because this programme is not cross-departmental, and does not separate out the PSVI-related aspects of the training, the modest budget (which is partly not official development assistance) used for this training including conflict-related sexual violence is not included in the graphic above.

Findings

In this section, we set out our findings on the UK government’s approach to addressing conflict-related sexual violence, under the umbrella of the Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative, which is led by the FCO but includes contributions from the MOD and DFID. PSVI programming includes response and prevention interventions as well as influencing work.

Our findings consider to what degree this work is relevant to demonstrating a credible approach and meeting strategic aims, is effective in delivering on objectives, and how well the government is learning and adapting in this area. It should be noted that the UK is a leading voice among what is presently a small group of international donors working to address conflict-related sexual violence.

Relevance: Does the portfolio demonstrate a credible approach to preventing sexual violence in conflict and meeting the needs of survivors, as well as meeting the objectives and pledges set out at the 2014 Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict

The PSVI has contributed to making the UK a leading voice in the international effort to address conflict-related sexual violence, especially through its influencing work

The PSVI was explicitly envisaged as an FCO-led cross-departmental effort, aiming to bring together the comparative areas of expertise across the FCO, DFID, and the MOD. PSVI programming includes response, prevention, and justice and accountability programming, as well as influencing activities on raising awareness and setting international standards. The focus of this review was on programming “on the ground” and the extent to which the government has followed up on its commitments and ambitions set out at the 2014 Global Summit.

In 2014, the PSVI team held the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, an unprecedented gathering of 1,700 delegates. The summit included over 175 external public events in London and an 84-hour global relay of international events held around the world. Directly following the Global Summit, 113 states endorsed the Declaration on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict, a number that has since risen to 156 UN member states. Self-identified ‘champion countries’ have continued their engagement after the summit, partnering with the UK government to share learning and best practice and discuss future opportunities to address conflict-related sexual violence in a collaborative atmosphere.

Other global-level PSVI influencing activities include, for instance, five ministerial statements and diplomatic telegrams on conflict-related sexual violence, the presentation at the UN General Assembly by Lord Ahmad of Wimbledon, the Prime Minister’s Special Representative on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict, of learning from stigma workshops in nine countries, and the engagement of Afghan ministers and high-level stakeholders in Bosnia and Herzegovina in talks about conflict-related sexual violence.

The Initiative’s contribution to setting international standards has been particularly noteworthy. The 2014 International Protocol on Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict and its second edition published in 2017 (see also the effectiveness section of this review) and the 2017 publication of Principles for global action: preventing and addressing stigma associated with conflict-related sexual violence offer guidance specific to conflict-related sexual violence in the absence of other tools and contribute to setting standards for gathering evidence and tackling stigma for survivors.

The government’s level of effort and activities intended to address sexual violence in conflict are not commensurate with the objectives and pledges set out at the 2014 Global Summit

In 2014, the PSVI benefited from strong leadership from Lord Hague and a peak in FCO funding at £15 million. The 2014 Global Summit culminated in the publication of a list of commitments and pledges, and a commitment by the foreign secretary that the UK would move forward with practical interventions to address conflict-related sexual violence. In his closing statement, Lord Hague summed up: “And now we have done so much this week, we must go on to do even more, and accelerate our work over the coming months and years. We must follow up the implementation of the international protocol, and move towards practical action that makes a difference on the ground in some of the worst-affected countries.”

However, momentum since the summit has not been maintained. There was a drop in interest in the Initiative at the ministerial level following Lord Hague’s departure as foreign secretary soon after the summit. The role of the Prime Minister’s Special Representative on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict was shifted from the foreign secretary to the level of junior minister. This resulted in ministerial attention and funding being redirected elsewhere.

This loss of leadership was compounded by the nature of the summit pledges, which were targeted towards political leadership and included broad commitments to “do more to … challenge the impunity that exists and to hold perpetrators to account … and to support both national and international efforts to build the capacity to prevent and respond to sexual violence in conflict”. In the aftermath of the summit, nothing was done to translate the pledges into practical and measurable steps or transform them into an action plan. Indeed, there is no process in place to review progress on Global Summit pledges. This lack of accountability meant momentum was lost, and a number of survivors and survivor-led civil society organisations (CSOs) across contexts expressed great disappointment that they had received no update on progress towards the pledges.

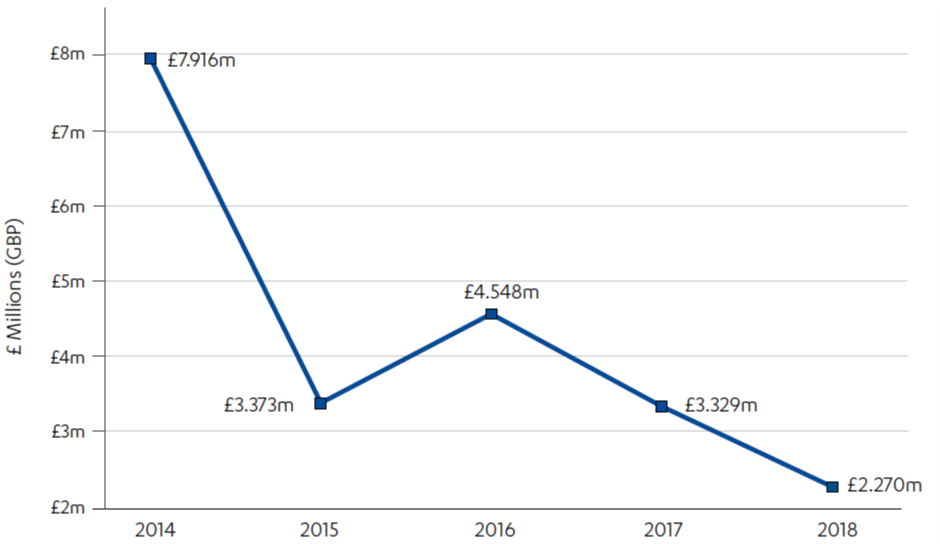

Dramatic cuts to the PSVI budget have reduced the Initiative’s ability to follow up on the UK’s own commitment. Between 2014 and 2019, PSVI funds managed by the London-based team have fallen from £15 million to £2 million per year (Figure 5). The drop in PSVI-specific funding at country level has also been dramatic, if more uneven, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Human resources have fallen commensurately. In 2014, the PSVI team included 34 staff members, most of whom were consultants brought in for the 2014 Global Summit. After Lord Hague’s departure in mid-2014, the PSVI team was reduced to five people. At present, the team consists of three staff members and one graduate intern. The number of deployments of the separate PSVI Team of Experts has also significantly decreased since the summit. The Team of Experts supports PSVI work through, for example, training of in-country partners on how to gather evidence using the International Protocol and conducting in-country conflict assessments.

In contrast to the modest PSVI budget at the FCO, DFID has run large, comprehensive programming on violence against women and girls (VAWG) since 2010. The MOD meanwhile contributes to PSVI primarily through the training of troops on issues related to conflict-related sexual violence. It has used a modest amount of combined official development assistance (ODA) and non-ODA funds on troop training since 2017, with issues of conflict-related sexual violence constituting one element of this training.

Figure 5: Centrally managed PSVI funding per year

Figure 6: Drop in PSVI funding at country level

While the UK’s modest PSVI funding should be seen in the context of a general lack of funding in this area by international donors, it is nevertheless not commensurate with the UK government’s ambitions set out at the Global Summit. The short-lived spike followed by a rapid and sustained drop in funding is particularly problematic when considering that addressing the complex and entrenched challenge of conflict-related sexual violence requires long-term, unwavering commitment, a strong strategic focus with clear objectives, and a comprehensive approach. In the words of one senior FCO representative, “this will take a generation, it’s not like building a road”.

The Initiative lacks a clear strategy and overall vision to guide its activities

“There must be a strategy in place [for] what to do with [conflict-related sexual violence] CRSV cases, by the state and the donors, and we need to document all the experiences, as soon as possible.”

– Survivor-led CSO, Bosnia and Herzegovina

The PSVI has never had a strategic vision or plan driving its work. This was less noticeable in the early days, with the work on the International Protocol and preparations for the summit dominating PSVI activities. However, as the budget fell after the summit, the lack of a strategic plan became more evident as the Initiative’s programmatic focus shifted from the International Protocol to implementing a disparate range of smaller projects, often funded through country office budgets. The fragmentation was noticed in the 2016 House of Lords report, which recommended that the government adopt a strategy and five-year plan to drive the Initiative’s work. However, no strategic plan was developed in response to this recommendation.

In interviews, some government stakeholders explained that the UK’s National Action Plan on Women, Peace & Security (NAP) serves as the PSVI’s strategic plan. However, the NAP does not go into detail about the Initiative as it covers a broad range of work across multiple UK government departments linked to the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda. Moreover, a concrete set of strategies are not offered and the visibility of the PSVI has noticeably decreased in the 2018-22 NAP as compared with the 2014-17 version of the document. The NAP represents the UK’s commitment to the global WPS agenda, which itself covers only the Initiative’s prevention and response programmes with women and girls.

The PSVI is organised around three thematic strands – justice and accountability, stigma, and prevention – and guided by ‘core scripts’, short three-to-four-page internal memos updated annually and used for internal FCO communication only. The core scripts do not replace the need for a strategy: they do not contain a vision, concrete objectives, or indicators of success. They do not allow for internal or external scrutiny of the initiative’s achievements. Furthermore, neither the PSVI as a whole nor 90% of the PSVI projects implemented since 2014 are guided by a theory of change. The only exception is the country team in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which introduced a theory of change for PSVI programming in 2017. The government also pointed to the Shared UK Government Approach to Gender in Syria as a good example.

Without a strategy, specific objectives or a theory of change driving the Initiative’s work, implementation has come in “bits and pieces”. Each department and in-country team is left to interpret the Initiative according to their own priorities rather than through a unified cross-departmental vision. The selection of PSVI ‘priority countries’ – an annually updated list of countries targeted for PSVI funding – is similarly informal. Three senior FCO representatives explained that there are no formal selection criteria for the “[not] wholly scientific exercise” of choosing PSVI priority countries. In 2017, Somalia was removed from the priority country list in the face of clear need as noted by two senior government representatives. That same year, Sri Lanka was added as a priority country with little evidence justifying this selection. Despite recent assessments of survivor need in Zimbabwe and Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh, there is no evidence of how or whether these locations will be prioritised.

While the PSVI falls under the NAP, only five out of nine NAP focus countries are also PSVI priority countries (Burma, the DRC, Iraq, South Sudan and Syria). Adding confusion, the Initiative funds projects outside PSVI priority countries if a “strong rationale for funding” is provided. What constitutes a strong rationale, however, is not defined.

The lack of a shared understanding of the problem has inhibited cross-departmental collaboration on addressing conflict-related sexual violence

The PSVI was intended as a “tri-departmental initiative”, drawing together DFID, the FCO and the MOD in a cross-departmental effort led by the FCO. Little progress has been made in cross-departmental collaboration since the House of Lords report. While all agree that the FCO leads the Initiative, DFID and the MOD see their contributions to the PSVI as supplemental rather than as integral pieces of the PSVI portfolio. Collaboration has been hampered by lack of alignment in the way each department understands, addresses and prioritises the problem of conflict-related sexual violence.

In DFID’s case, conflict-related sexual violence falls under the VAWG team. Its programmatic focus is based in the fact that women and girls are disproportionately affected by sexual violence both within and outside conflict-affected settings and that the most prevalent form of sexual and gender-based violence is intimate partner violence. As a result, DFID programming tends not to target forms of sexual violence more often found in conflict settings, such as mass and gang rape used to either displace or control populations, or both, or the use of sexual violence against men and boys as a war tactic to humiliate them and damage social relationships.

The FCO, on the other hand, focuses only on conflict-affected settings for its PSVI work. This leads to a portfolio of programming specific to trends and types of sexual violence particular to conflict settings. Meanwhile, for the MOD, conflict-related sexual violence is only one element of its work under the department’s broad ‘protection of civilians’ agenda, which they now refer to as ‘human security’.

The lack of alignment in understanding of this issue is translated into differences in programming and resource prioritisation, which directly impacts survivors. These differences become most visible around how programming engages men and boys. DFID’s VAWG activities almost entirely engage men and boys as (potential) perpetrators and only rarely as possible survivors. In contrast, the FCO engages men and boys in a variety of programmes, including supporting male survivors of sexual violence, and implements interventions aimed at reducing stigma in order to encourage male survivors to seek support services. While DFID and the FCO are not aligned, both departments are explicit about the gendered nature of conflict-related sexual violence. In contrast, many stakeholders take issue with the MOD’s use of ‘human security’ as masking the gendered nature of sexual violence.

This lack of alignment has resulted in a long-standing and often heated debate over terminology and concepts. The effect on programming, and thus the impact on survivors, is clear. Instead of reaching cross-departmental agreement on a pragmatic division of labour, under the oversight of a central PSVI team, the Initiative has remained primarily an FCO effort, with DFID and the MOD as supplemental rather than integral to the Initiative. At country level we saw missed opportunities for collaboration as a result of different visions. For instance, in Somalia, while there is a strong culture of cross-department collaboration, we found little evidence of departmental coordination on conflict-related sexual violence.

Conclusions on relevance

The PSVI’s influencing activities have contributed to making the UK a leading voice in the international effort to address conflict-related sexual violence, through convening countries and leaders around the need to address conflict-related sexual violence or set international standards.

The Initiative benefited from initial strong leadership and a peak in funding in 2014. After this point, ministerial interest fell along with the PSVI team’s budget and staffing levels. There is no strategic vision or plan driving the work of the Initiative, leaving each department and the country-based staff to interpret the Initiative according to their own priorities. The overall consequence is that activities aimed at addressing conflict-related sexual violence are often not prioritised at all.

We give the Initiative an amber-red score for relevance. There is a lack of coherent and clear strategic priorities around which cross-departmental collaboration could be built. While recognising the important agenda-setting role of the Initiative, the decrease in ministerial interest in and funding for the PSVI has meant that the UK government’s efforts are not commensurate with the ambitions and commitments it set out in 2014.

Effectiveness: How well have the programmes delivered on their objectives as well as the overall objectives of the PSVI?

In the background section to this review, we noted the minimal evidence existing on what works in preventing and responding to conflict-related sexual violence. This is a challenging field in which to achieve impact, and this needs to be considered when assessing effectiveness. While there is little evidence on what works, the available evidence shows that a survivor-led approach focused on wellbeing leads to greater success. With this in mind, programming to address conflict-related sexual violence must have a broad, long-term perspective anchored in the particular cultural context and conflict dynamics of the communities in which interventions take place.

The dearth of evidence from PSVI programming means that it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of the PSVI portfolio. Moreover, although globally there has been a growth in interest and concern over the past decade, the issue of conflict-related sexual violence has received limited resources. Results data is often of poor quality, but we were able to identify a range of promising, and sometimes innovative, projects funded through the Initiative. These projects have been influential in setting the agenda for international efforts to address conflict-related sexual violence.

Box 4: Examples of potentially effective and innovative PSVI projects

FCO – Rights of survivors and their children born as a result of wartime rape, implemented by Medica Zenica (Bosnia and Herzegovina).

Improving the rights of survivors of sexual violence and of children born as a result of rape during war through the provision of survivor-centred services, such as, for example, the establishment of a 24/7 free of charge hotline for survivors to access free counselling, support and information.

FCO – Protecting Women from Sexual Violence in Conflict, 2016-18, implemented by CORD (Burma).

The International Protocol was adapted into a user guide and translated into local languages. The user guide was then distributed to local civil society, police, government, and community leaders, and eventually led to the first 20-year sentence in Shan state under the Burma Penal Code.

FCO – Building Community Approaches for Supporting Victims and Preventing Sexual Violence, implemented by Liga Internacional de Mujeres por la Paz y la Libertad and Corporación Casa Amazonia (Colombia).

Local partners implemented a comprehensive, culturally sensitive approach to supporting survivors, including through self-help groups led by local women leaders and the integration of indigenous medicine into services designed to provide physical and psychological healing support.

FCO – Fighting against impunity by bringing perpetrators to justice, implemented by TRIAL International (DRC).

TRIAL and local partners relied on the International Protocol to secure the conviction of 11 Congolese militia members in the Kavumu trial in South Kivu. The International Protocol is also being used to train forensic police officers on evidence gathering and protection in Bukavu, the capital of South Kivu.

DFID – Engaging with faith groups to prevent violence against women and girls in conflict-affected communities, implemented by Tearfund and Heal Africa, as part of the What Works to prevent VAWG programme (DRC).

Focusing on prevention and evidence gathering, Tearfund and Heal Africa worked with 75 local faith leaders, in 15 communities in Kivu to address the underlying causes of violence against women and girls, especially social norms that support male dominance and contribute to impunity for survivors. The project recorded significant reduction in rates of self-reported intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence experienced by women in these communities.

MOD – UK Major seconded as Gender Advisor to the UN Peacekeeping force MONUSCO, (DRC).

The secondment of a British Gender Advisor to the MONUSCO is helping peacekeeping troops integrate the issue of conflict-related sexual violence into their mandate, as part of their mission to protect civilians. Among other things, the Gender advisor developed pocket cards for soldiers to carry with them to be able to recognise, respond and report if an incident of conflict-related sexual violence occurs.

DFID – United Nation Joint Human Rights Office, (DRC).

DFID provides funding to the Human Rights office, which documents abuses from the DRC military and government forces and monitors consistently abuses of human rights violations, including sexual and gender based violence perpetrated by these forces. This increases the visibility of violations and contributes to putting pressure on the Congolese government to address them.

FCO – From Words to Actions: Preventing Sexual Violence against Women and Girls in Southern Iraq, implemented by War Child UK (Iraq).

This project worked with Islamic religious leaders to raise awareness about sexual violence through cultural and religious events in communities. It also helped to create informal mediation systems to increase community investment in protecting women and girls. As a result, 150 survivors received safe access to support services and two female-only shelters were established and supported by the government in Basra and Thi Qar.

FCO – Engaging youth in awareness raising through local radio stations, implemented by BBC Media Action (Syria).

Local radio stations were mobilised to inform and empower everyone to be more active partners in tackling sexual violence. Awareness raising sessions were used to increase their capacity to challenge negative social norms.

MOD – British Peace Support Team (Africa).

The MOD works to improve the capability of troops from contributing countries to peacekeeping missions deployed by the African Union or the United Nations. With the help of a dedicated Gender Advisor, the MOD has integrated addressing conflict-related sexual violence in its pre-deployment training packages to troops who will then deploy in countries like Somalia or the DRC. The MOD is currently piloting a new methodology to measure the outcomes of these pre-deployment training packages.

FCO/MOD (CSSF) – Stabilisation and Security Sector Reform (Somalia).

The British Army and the British Embassy in Mogadishu have worked together with assistance from the BPST(A) to design a training of trainers programme for the Somali National Army with a module on conflict-related sexual violence, using its training facility in Baidoa. One of the promising features of this project is that it aims to have Somali trainers take the lead in designing training modules that will be appropriate and better targeted to the Somali context.

Interventions centred on the International Protocol have created a lasting impact

The International Protocol on the Documentation and Investigation of Sexual Violence in Conflict was first published by the Initiative in 2014, with a second edition produced in 2017 after receiving greater input from the UN. The Protocol was developed with the aim “to help overcome the barriers to prosecution, by setting out clearly and comprehensively the basic principles of documenting sexual violence as a violation of international law”. The All Survivors Project, a global network, noted that the International Protocol made a genuine contribution to the sector. The document has been used in 16% of all justice and accountability programming reviewed for this report, and in particular in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burma, Colombia, the DRC, Syria, Uganda and Iraq. The International Protocol is used at grassroots and institutional levels to train focal points in remote communities, police, medical professionals, lawyers and judges. Six of the organisations interviewed during this review, including the UN Joint Human Rights Office and the Office for the Coordinator of Humanitarian Affairs, confirmed widespread knowledge of the document among partners in civil society.

Perhaps the best example of lasting impact comes from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Here, the International Protocol provided the necessary structure to (a) enable the use of information gathered by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and service providers, (b) litigate individual cases and secure redress through judicial or quasi-judicial mechanisms, (c) submit documentation gathered according to international standards to law enforcement, investigative, and judicial bodies, (d) securely store evidence for later use in accountability and transitional justice processes, and (e) use evidence to assist survivors in filing non-judicial claims.

The Initiative has funded partners with strong local ties who are meeting their stated output objectives

The Initiative has identified and funded implementing partners with strong local ties and high levels of trust in local communities in country. For instance, Bosnian survivors and their allies told us that the Initiative was a ‘game changer’ in this way. Through local partnerships, the PSVI focal point catalysed increased reporting on sexual violence across Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In most cases, partners funded by the UK government work through strong networks of local CSOs and projects are delivered efficiently on the ground. TRIAL International, CORD, Tearfund and World Vision, among others, have impressively navigated tight timelines and small budgets while still meeting their stated output objectives.

Our strategic review of 114 projects across ten countries showed that partners have delivered on their commitments. For example, in the DRC, all PSVI-funded projects except one met 100% of their output targets. All projects in Burma and Colombia met their stated output goals, with the exception of six projects that encountered intractable challenges in the local political climate.

There is little monitoring and reporting on how outputs translate into lasting outcomes, making it difficult to assess the effectiveness of interventions

PSVI-funded projects are only required to report on outputs, or activity-based figures such as the number of workshops held or participants trained. Only PSVI projects funded by the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) have a better oversight structure, as the CSSF recently established proper monitoring mechanisms, including results frameworks and progress tracking against outcomes. Otherwise, the effort to track and assess progress towards outcomes – best understood as longer-term changes in attitudes and behaviours – has not been made, although we found a few one-off attempts by individual implementing partners. Some implementing partners have attempted to measure change beyond that required by the Initiative. Without proper financial and methodological support, however, they have faced challenges. Because of this, evaluating the PSVI’s impact on survivors and their communities is difficult.

Without a requirement for detailed reporting, including a list of indicators and means of verification, only anecdotal evidence can be found on outcomes of PSVI-funded projects. As an example, partners note that the Initiative’s work on stigma has raised awareness, but evidence of attitude and behaviour change to support these statements is lacking. Instead, ‘success’ is frequently defined at the output level only by the number of people engaged in projects.

The FCO’s one-year funding cycle has restricted the Initiative’s ability to address deep-rooted issues and has negatively impacted programme effectiveness

“The most urgent need is the ‘holistic care’, this is the first and most urgent need.”

– Survivor, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

In referring to “holistic care”, the survivor points to the need for comprehensive or ‘radical’ interventions on root causes. Survivors consistently express the need for long-term programming to address the deep-rooted causes and effects of conflict-related sexual violence. They point to a lack of medical services, the importance of livelihood support when survivors are ostracised by their communities, and the challenge of carefully reducing stigma to make way for more survivors to access resources. Those working on sexual violence across DFID, the FCO and the MOD also emphasise the need to address root causes and effects, rather than the more superficial symptoms of conflict-related sexual violence. And yet, a range of projects we reviewed in Burma, the DRC, South Sudan and Uganda were forced to concentrate on symptoms because of the FCO’s one-year funding cycle.

The PSVI follows the FCO’s approach to funding and supports projects through what it calls ‘catalytic seed’ funding guaranteed for one year. The idea behind this short-term, ‘catalytic’ funding is to attract larger, long-term funding from other donors, such as DFID or the UN, after an initial PSVI-supported proof of concept. In one sense, this funding approach is agile, and may enable the piloting of innovative projects, especially among smaller organisations that would otherwise struggle to access funds. In a field where evidence on what works is limited, there is clearly an important space for innovative and experimental approaches, if part of a package of longer-term as well as short-term funding.

However, this catalytic funding approach permeates the PSVI portfolio. The great majority of PSVI projects in the portfolio, including all FCO-funded projects, were limited to the one-year funding cycle, and we did not see evidence of these short-term projects ‘catalysing’ funding from other donors. In practice, this short-term nature of the Initiative’s funding cycle limits what projects can achieve. Frequent delays in the disbursement of funds, combined with the FCO’s 80% rule – requiring that 80% of funds be spent by December of the financial year of disbursement – often reduces a 12-month programme to effectively nine or even six months with little notice. Partners across the case studies explained that they sometimes had to spend PSVI funds very fast, with disregard for the quality of programmes, to complete spending before the funding cycle ended. A number of PSVI-funded projects reviewed here concluded abruptly, regardless of their success, after their funding was not renewed.

We were informed by a range of interviewees, including programme staff, that project preparation and expertise building is limited as a result of this rushed approach. The FCO’s annual rather than multi-year funding approach also places an undue burden on civil society and community-based organisations that must quickly scale up programme teams when awarded funds and reduce programme staff with little warning, if funding is not renewed, only one year later.

The FCO’s one-year funding approach has limited benefits and risks causing harm to survivors. It is an impediment to meaningful inclusion of survivors, due to rushed planning and implementation. Delays in funding and unrealistic project timelines risk doing more harm than good to survivors who embark on lengthy justice processes extending well beyond the Initiative’s one-year funding cycle. Partner organisations in the DRC highlighted the lack of congruence between justice processes that can take five to ten years and funding not guaranteed beyond one year. We heard that survivors and their communities are sometimes engaged in consultations during project preparation and then experience long delays waiting for the Initiative to fund service delivery. Bosnia and Herzegovina was an example of this widespread problem, where survivors were frustrated by delays in service delivery while implementing organisations waited for disbursement of PSVI funds.

The Initiative lacks robust mechanisms to ensure that survivors are meaningfully included in the choice, design, and implementation of projects and that the principle of ‘survivor wellbeing’ guides all activities

In general, survivors call for programming that addresses the challenges they face. Survivors desire support that enables them to thrive rather than simply survive. After immediate medical care, survivors call for victims’ assistance and mental health services. A survivor in Bosnia and Herzegovina noted that “medical support is needed given that the trauma is trans-generational”. Similarly, in the DRC, several CSOs made it clear that the most urgent need was a comprehensive approach that focuses on a survivor’s wellbeing. Financial victims’ assistance provides much needed emotional closure and can be a lifeline if the survivor has been ostracised by her community. If victims’ assistance is not available, survivors say that livelihood support, ideally in the form of long-term income-generating activities, allows them to care better for themselves and their children, while also encouraging reintegration into their communities. Mental health services help address lasting trauma and stigma, survivors report.

Survivors are not consistently included in the planning and design of PSVI projects. This omission goes against best practice and increases the risk of causing unintentional harm. In-country teams do not have formalised processes for consulting survivors during project design, implementation or monitoring. In the projects where survivors were engaged, this was often done in ad hoc ways, including survivors being consulted about their experiences and asked for their insights without follow-up to explain how their contributions have been used. In many cases, contact ceased after initial engagement, a practice which risks doing harm to survivors.

Moreover, we were unable to identify any formal processes or ethical protocols which set out how and when survivors would be engaged, or how the project would ensure that its interventions posed no risk of doing harm to survivors.

We found some positive examples of survivor inclusion, including the appointment of survivor champions to advise the PSVI London team. Other examples we found were all at the initiative of partner organisations. The ‘Building Community Approaches for Supporting Victims and Preventing Sexual Violence in Colombia’ project (see Box 4) offers one example. In this project an ‘ideal route’, which highlighted both obstacles and recommendations for institutions responding to survivors in armed conflict, was created by female survivors. Focus group discussions were held, providing indigenous, Afro-Latina and forcibly displaced women the space to express their concerns about approaching traditional indigenous justice systems. The project also gave participants the opportunity to recommend approaches to key decision-makers from the Victims’ Unit, the Regional High Commissioner for Gender Equality, and the ombudsman’s office in Bolívar, Meta, Putamayo, and Bogotá.

The PSVI team has no oversight of funding

The Initiative has no single source of funding. Instead, PSVI-supported projects are funded through the CSSF, the Rules-Based International System (RBIS), the Global Britain Fund, ODA and non-ODA MOD funds, DFID’s VAWG budget and the FCO’s Gender Equality Unit budget.

The multitude of funding streams partly explains why there is no single repository of PSVI project information where a record of spending, goals and objectives, and evidence is kept. Moreover, the PSVI team does not oversee the entirety of ‘PSVI funding’ and activities. Instead, each department and in-country team manages its own records and funding as it sees fit, and rarely shares information with others. When conducting our strategic review, we were given inconsistent spending figures by the PSVI team in London and by country offices and teams.

Many country teams are not clear about the link between their work on conflict-related sexual violence and that of the Initiative itself.

Weak staff capacity undermines the impact of the Initiative

Understaffing, high turnover and, in many cases, staff lacking expertise in the area, limit the impact of the Initiative. In many cases, ‘institutional knowledge’ within country offices and teams is heavily dependent on a single individual. While these individuals are committed, PSVI is only one of their many responsibilities: PSVI focal points at country level must balance urgent priorities. This often leaves between 5 and 10% of their time at most to allocate to projects on conflict-related sexual violence. In the DRC, for example, the PSVI lead is tasked with overseeing the Ebola response, government transition, and outbreaks of violence across the DRC and the Republic of the Congo. Similar patterns are visible in Burma with the recent Rakhine state conflict.

Conclusions on effectiveness

While the government’s investments and interventions are modest, the PSVI work is significant in a context where few donors are deeply engaged. The International Protocol is one of the main achievements of the Initiative, having been used in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burma, Colombia, the DRC, Syria, Uganda and Iraq.

Identifying implementing partners with strong local ties has been a strength of the Initiative. These partners worked through strong networks of local CSOs and have impressively navigated tight timelines and small budgets while still meeting their output objectives. However, assessing their effectiveness has not been possible because PSVI-funded projects are not required to assess progress towards outcomes.

Survivors consistently express the need for long-term programming that addresses the deep-rooted causes and effects of conflict-related sexual violence. Yet many projects were forced to concentrate on symptoms rather than causes because of the FCO’s one-year ‘catalytic seed’ funding approach.