Rapid Review: Management of the 0.7% ODA Spending Target

Introduction

This paper provides an overview of the Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI) Rapid Review of how the UK government manages the 0.7% Official Development Assistance (ODA) spending target. The International Development (Official Development Assistance Target ) Act 2015 states: “It is the duty of the Secretary of State to ensure that the target for official development assistance to amount to 0.7% of gross national income is met by the United Kingdom in the year 2015 and each subsequent calendar year.”1 If that target is not met in any given year, the Secretary of State must present an explanation to Parliament, based on economic or fiscal conditions in the UK or overseas, and state the steps that will be taken to make sure the target is met the following year. The Act also requires the Secretary of State to make arrangements for the independent evaluation of the extent to which UK ODA represents value for money. ICAI is seen as the means by which this commitment is met.

Background to the 0.7% target

The idea of an ODA spending target first emerged in the 1950s and 0.7% of donor national income was officially agreed as an international target by the United Nations General Assembly in 1970. In a 2004 Spending Review, the UK’s Labour government set a target date of 2013 for achieving the 0.7% target, earlier than the pledge by EU member states of 2015. This was reaffirmed by the UK’s Coalition government elected in 2010, and was duly achieved in 2013, subsequently becoming a legal obligation from 2015. The UK is one of only seven OECD countries to have reached the target, alongside Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway and Sweden (who all currently meet or exceed the target) and the Netherlands and Germany (who have met the target in the past). The UK is currently the only G7 country that meets the target.

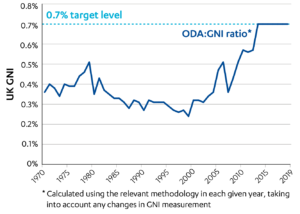

Figure 1: The UK’s official development assistance (ODA) as a percentage of Gross National Income (GNI)

Managing the commitment to spend 0.7% of Gross National Income (GNI) on ODA

The commitment to hit the 0.7% spending target led to an initial rapid scaling up of UK aid, from £8,802 million in 2012 to £11,407 million in 2013. For the Department for International Development (DFID), ODA spending increased from £7,624 million in 2012 to £10,016 million in 2013, requiring an equally rapid evolution in DFID’s capacity and business systems. This scale up occurred as the UK maintained ODA spending at 0.56% between 2010 and 2012 (the interim target committed to by EU member states) and then opted to scale up to 0.7% in 2013. A change in the methodology for calculating GNI in 2014 meant that UK ODA spending had to be increased significantly in order to meet the target in 2016. The UK aid budget has increased in proportion with GNI, at an average increase of £628 million per year (£505 million per year excluding 2016). DFID, referred to as the ‘spender and saver of last resort,’ is required by HM Treasury (HMT) to spend or save the difference between other ODA spend and the 0.7% GNI target to make sure that the ODA commitment is met by 31 December each year. DFID’s Strategic Objective 6 in its latest Single Departmental Plan focuses on improving the value for money and transparency of UK aid. This includes maintaining the commitment to spend 0.7% of GNI on ODA and to keep all UK aid untied, supporting other departments in assessing whether spending proposals meet the OECD’s rules on ODA spending, and reporting annually to the OECD and to Parliament on the government’s performance against achieving the 0.7% target.

Purpose and scope of the Rapid Review

Given that the UK government’s commitment to the 0.7% ODA spending target is a key element of UK aid policy, ICAI will apply its specialist knowledge in examining whether the complexities of managing the target affect the quality of UK aid spending. Reviewing the commitment itself is not within the remit of this review. The review will focus on how ODA spending departments and cross-government structures such as the Senior Officials Group manage the value for money risks associated with the spending target. It will also explore how ODA spending departments have generated and applied lessons learnt to their approaches on value for money in managing the 0.7% spending target. Our timeframe of analysis is 2013 to 2019 and we will build on previous reviews conducted by the National Audit Office (NAO) on this topic. Although ICAI will not focus on the effects of COVID-19 or the merger of DFID with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, we will factor these into the review’s recommendations.

Review questions

- Relevance: What is the process for allocation, monitoring and management of ODA spending targets to individual departments, and how well is this process governed and managed?

- Efficiency: What are the value for money risks associated with meeting the spending target, and how well do the responsible departments mitigate them?

- Learning: To what extent have departments reduced the value for money risks associated with meeting their spending target?

Methodology

Our methodology is composed of four intersecting components:

- Annotated bibliography: A review of the key literature outlining the UK’s approach to managing the 0.7% spending target.

- Strategic review: A review of key government documents related to the allocation of ODA, and the monitoring and management of the 0.7% spending target.

- Interviews, focus group discussions, and submissions: Interviews with government officials from across DFID, HMT and other spending departments. Virtual focus groups with UK civil society, universities, think tanks, and independent experts. An open invitation for submissions.

- Case studies: These will explore how the spending target has been managed by/affected the aid programmes of a sample of government departments, cross-government funds, multilateral aid agencies, and other dimensions of spending, looking across the period 2013 to 2019.

Timeline

Research for this review began in July 2020 with publication expected in November 2020.