Review of UK Development Assistance for Security and Justice

1. Introduction

1.1 The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is the independent body responsible for scrutinising UK aid. We focus on maximising the effectiveness of the UK aid budget for intended beneficiaries and on delivering value for money for UK taxpayers. We carry out independent reviews of aid programmes and of issues affecting the delivery of UK aid. We publish transparent, impartial and objective reports to provide evidence and clear recommendations to support UK Government decision-making and to strengthen the accountability of the aid programme. Our reports are written to be accessible to a general readership and we use a simple ‘traffic light’ system to report our judgement on each programme or topic we review.

1.2 We have decided to conduct a thematic review of UK security and justice (S&J) programming. This review was requested by a number of stakeholders during the public consultation on our work plan. We will examine security and justice programming delivered by DFID and other government departments at the portfolio level and through country case studies, with a focus on its effectiveness in delivering improved justice and security to women and girls.

1.3 These Terms of Reference outline the purpose and nature of the review and identify its main themes. A detailed methodology will be developed during an inception phase.

2. Background

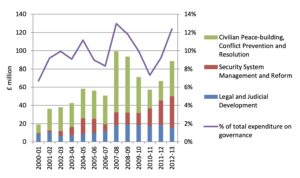

2.1 As DFID has increased the share of its assistance going to states affected by conflict and fragility, support for S&J has become an increasingly important part of its governance portfolio. DFID has undertaken to implement new S&J programmes in 12 fragile and conflict-affected states,1 to provide 10 million women and girls with improved access to security and justice services2 and to tackle violence against women in at least 15 countries.3 While DFID does not report separately on its S&J expenditure, an indication of the growth in its S&J portfolio can be gained from combining a number of different ‘input sector codes’ from its aid statistics (Security System Management and Reform; Civilian Peace-building, Conflict Prevention and Resolution; and Legal and Judicial Development). As Figure 1 shows, the S&J portfolio has grown from under £20 million in annual expenditure in 2000-01 to £89 million in 2012-13 and from 7% of its total governance portfolio in 2006-07 to 12% in 2012-13. These figures may not capture the full S&J portfolio.

2.2 S&J is a broad area, with no settled definition of its boundaries. DFID describes it as encompassing the values and goals associated with the rule of law (for example, freedom, fairness, personal safety) and the institutions established to promote them (including defence forces, police, courts, prosecutors, public defenders and corrections systems).4 It covers both the criminal and civil justice systems, as well as work with informal systems of justice, including paralegals, alternative dispute resolution, traditional justice systems, crime prevention, community safety and empowering communities and groups of people to exercise their legal rights. While the term ‘S&J’ also encompasses security sector reform (democratic control over the security sector), this will not be a particular focus of this review.

2.3 DFID’s S&J programming serves a range of policy objectives. It is seen as part of the solution to conflict and fragility. The Building Stability Overseas Strategy notes that ‘we cannot build stable states without functioning security and justice systems’ and that ‘access to justice is a basic need for all citizens’.5 DFID’s Practice Paper on building peaceful states and societies lists security, law and justice as among the core functions that must be established as part of a transition out of conflict and fragility.6

Source: DFID bilateral expenditure by input sector code 2000-01 to 2012-13, January 2014, DFID,

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/268308/Table_17.csv/preview.

2.4 S&J also serves wider development goals. The High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda has proposed the building of responsive and legitimate institutions that promote the rule of law and access to justice as one of five ‘transformative shifts’ for the new international development agenda that will follow the Millennium Development Goals. It describes freedom from fear, conflict and violence as ‘the most fundamental human right and a foundation for building peaceful and prosperous societies’.7 There are various other rationales offered in the literature as to why S&J should be part of the development agenda. Earlier literature, dating back to the 1970s, stresses the importance of secure property rights, enforceable contracts and protection from arbitrary state interference as essential to efficient markets, enabling economic actors to invest with confidence.8 More recent literature stresses the direct costs of crime and injustice for the poor and notes that personal security is a precondition for the poor to access basic services.9 The legal empowerment movement focusses on enabling poor communities to use the justice system as a tool for their own advancement.10 In 2012, the Prime Minister David Cameron listed an independent judiciary, the rule of law, the rights of individuals and democratic control of the military as part of the ‘golden thread’ that links ‘successful countries and sustainable economies all over the world’.11

2.5 Most recently, the International Development Secretary, Rt. Hon. Justine Greening MP, committed DFID to tackling violence against women and girls around the world. DFID’s work in this area includes both S&J assistance and broader interventions designed to empower women and women’s organisations to promote social change.12

2.6 Within DFID, the policy leads for S&J and violence against women and girls are with the Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Department (CHASE), through two separate teams. CHASE’s mandate includes technical support for S&J programmes, commissioning research, promoting innovation, policy development and international policy advocacy. CHASE has established communities of practice on S&J and violence against women and girls, which promote the sharing of experience within DFID. It also commissioned help desk services in both areas, run by specialist organisations, to develop guidance material and provide technical advice to DFID staff. DFID’s Governance, Open Societies and Anti-Corruption Department is also engaged in policy development on the rule of law and development.

2.7 There is a range of other government departments with a mandate in this area. The Stabilisation Unit, which provides operational support and personnel for the UK’s response to crises abroad, includes a Security and Justice Group, which acts as an operational hub for S&J support in fragile and conflict-affected states. It has a roster of advisers from both inside and outside the UK Government who are able to deploy on short notice into stabilisation contexts. The tri-departmental Conflict Pool funds S&J programmes in many countries, which may be implemented by DFID, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) or the Ministry of Defence (MoD). There are also other departments and agencies involved in the delivery of UK S&J assistance, either from their own budgets or as implementers of DFID programmes. These include the Home Office, the Ministry of Justice, the Crown Prosecution Service and the National Crime Agency.

2.8 DFID has on-going S&J programmes in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Jamaica, Kenya, Libya, Malawi, Nepal, Nigeria, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, Somalia and South Sudan. According to DFID, most of these programmes are sector-wide in nature, investing in a number of S&J agencies, in public demand for S&J services and in the linkages between formal and informal S&J systems.13

2.9 There are also a number of global or thematic programmes, listed in the Annex on page 9. These include:

- a £4.4 million Security and Justice Innovation Fund (2012-16), which commissions innovative S&J pilot projects;

- a £2 million Global Legal Empowerment Initiative (2011-15), which funds the non-governmental organisation Namati14 to pilot grassroots legal empowerment activities. It is currently active in Bangladesh, Sierra Leone and Mozambique; and

- a £3.2 million contribution to UN Women (2010-14) to promote women’s participation in security and peacebuilding processes.

3. Purpose of this review

3.1 To assess the relevance and effectiveness of UK security and justice programming in addressing the security and justice needs of women and girls.

4. Relationship to other reviews/studies

4.1 Despite the growing prominence of S&J in UK and global development policy, the evidence base informing S&J programming is widely assessed as weak.15 The S&J topic guide in DFID’s Governance and Social Development Resource Centre states:

‘The evidence base for security and justice programming is generally weak and much of the literature is normative, presenting recommendations with little empirical evidence about what works. There is little in the way of rigorous evaluation on the effects of institutional reform programmes on security and justice provision’.16

4.2 It is often observed in the literature that there is no single, coherent purpose for S&J programming17 and that the record of tangible outcomes for poor people is not particularly strong.

4.3 DFID is in the process of conducting a thematic evaluation of its S&J portfolio. It has just completed the first stage of the process, which was an ‘evaluability assessment’. This involved a desk review of a sample of six S&J programmes, looking at their business cases, programme designs and monitoring and evaluation frameworks. It assessed the scope for a ‘macro-evaluation’,18 which would synthesise results across the portfolio against a common evaluation framework. No decision has yet been taken as to whether to proceed with a macro-evaluation.

4.4 DFID has commissioned other assessments of its S&J justice portfolio, including a 2005 desk review of programmes in seven countries,19 a 2007 evaluation of Conflict Pool-funded S&J sector reform programming in Africa20 and a 2009 review of lessons learned.21 More recent DFID S&J programmes include an evaluation component, so more evaluations of individual S&J programmes should become available in the coming years.

4.5 Some other donors have conducted thematic evaluations of their S&J portfolios, including the European Commission22 and the Government of Australia.23

4.6 Given the limits of evidence in this field, we conclude that our review can make a substantial contribution to knowledge in this area. If DFID decides to proceed with a macro-evaluation, it is likely to be a longer exercise, reporting over the next three years until 2017, which could then be informed by this review. Further, our focus on women and girls adds a unique perspective that directly addresses DFID’s capacity to deliver on recent policy commitments in this area.

4.7 We note that we have already reviewed one of DFID’s S&J programmes in Nepal and are currently looking at aspects of another in Nigeria in our ongoing review of DFID’s Approach to Anti-Corruption and its Impact on the Poor.24 In Nigeria, our review of the Justice for All Programme was focussed on its efforts to tackle corruption through the police, judiciary and central anti-corruption agencies. Our findings on those two programmes will inform this portfolio review. Our current review on DFID’s Scaling-up of Aid in Fragile States25 is also expected to generate finding that are relevant to this review.

5. Analytical approach and methodology

5.1 We will examine the UK S&J portfolio from the perspective of its ability to deliver on DFID’s headline commitment of improving S&J services for women and girls. We will assess whether S&J programmes and approaches are relevant to the needs and preferences of women and girls, whether they are effective in overcoming the challenges they face in accessing S&J services and whether they deliver real impact for this group of intended beneficiaries.

5.2 We have chosen to focus on women and girls for a number of reasons. It enables us to assess the relevance and effectiveness of DFID’s S&J programming for a defined group of intended beneficiaries, which is a central element of the ICAI approach. It enables us to assess the real value of DFID’s headline commitment to providing ten million women and girls with improved access to S&J services and whether it is making a substantial contribution to improving equity for disadvantaged groups. It also addresses an issue that is of considerable interest to the public, as revealed in our consultation on our work plan, on which DFID has made a substantial policy commitment.

5.3 The scope of the review will encompass the delivery of S&J assistance by any UK department or agency, provided it falls with definition of Official Development Assistance. This will provide us with an opportunity to examine the quality of coordination across the UK Government in this area and to assess the use of other government departments as implementing agencies for DFID-funded programmes. Our focus will be on the contribution that S&J assistance makes to international development, rather than other UK policy interests.

5.4 This will be a thematic review, drawing conclusions about the relevance and effectiveness of UK S&J assistance as a whole. This review will use as its basis the standard ICAI guiding criteria and assessment framework, which are focussed on four areas: objectives, delivery, impact and learning. A detailed methodology will be developed during the inception phase, setting out the assessment questions and the methods to be used for answering them. Likely questions will include:

5.5 Objectives

5.5.1 Does UK S&J programming have objectives that are clear, realistic and relevant to country context and the needs of women and girls?

5.5.2 Is UK S&J programming strategic in orientation and based on sound evidence and credible theories of change at the portfolio, country programme and intervention level?

5.5.3 Is there coordination and coherence across UK Government departments and agencies engaged in S&J assistance?

5.6 Delivery

5.6.1 Does DFID make appropriate choices as to partnerships, funding and delivery options in its S&J portfolio and do its procurement processes provide good value for money?

5.6.2 Are other government departments effective delivery channels for UK S&J assistance?

5.6.3 Do S&J programmes engage effectively with partner countries, S&J institutions, their intended beneficiaries and those whose behaviour they seek to influence?

5.6.4 Are delivery arrangements flexible enough to respond to risks, opportunities and lessons learned?

5.7 Impact

5.7.1 Are there appropriate arrangements for monitoring inputs, processes, results and impact within S&J programmes and across the portfolio?

5.7.2 Is the portfolio maximising impact, particularly for women and girls?

5.8 Learning

5.8.1 Is DFID making sufficient effort to innovate and fill gaps in the evidence base as to how to improve S&J outcomes for poor people?

5.8.2 Are lessons on how to deliver results for women and girls being learned, shared and used to inform programming?

5.9 To enable us to generate findings at the portfolio level, our methodology will incorporate the following elements:

- a literature review and consultations with UK stakeholders to identify key challenges in the delivery of improved S&J outcomes for women and girls, from which we will generate a strategic assessment framework;

- a strategic assessment of the portfolio as a whole, through key informant interviews, reviews of strategies and guidance documents and desk reviews of a sample of programmes, to assess how well DFID addresses these challenges in its programming choices and designs;

- consultations with DFID staff, other government departments, UK development non-governmental organisations (NGOs), contractors and academics active in S&J assistance and tackling violence against women and girls, to collect feedback on contemporary approaches to these issues and on the current UK approach to S&J programming;

- an assessment of the effectiveness of other government departments as delivery channels for UK S&J assistance and of the level of cross-government coordination and coherence;

- an assessment of DFID’s efforts to promote innovation and generate new knowledge, to fill the evidence gaps in the S&J field, through review of a sample of its non-country specific programmes (see paragraph 2.9); and

- detailed field assessment of S&J programmes in two or three countries, as case studies of different types of S&J programming in different country environments. The case studies will enable us to test hypotheses on the strengths and weaknesses of DFID’s overall approach to S&J programming, to review the quality of programme implementation and to assess the level of sustainable impact on women and girls. Our case study methodology will include:

- analysis of programme design documents, programme reviews, analytical work and results data;

- interviews with DFID country office staff, implementing partners and country counterparts;

- site visits; and

- consultations with groups of women and girls and other intended beneficiaries and stakeholders.

5.10 The number and choice of country case studies will be determined during the inception phase. The case studies will cover different types of S&J programming (such as civil and criminal justice; formal and informal justice systems; or innovative programme types) and country context (that is, whether or not fragile and conflict-affected). We will seek to include countries with a longer history of UK S&J programming, enabling us to assess impact over a longer period. We will take account of ICAI’s country focus in previous relevant reviews, to ensure breadth of coverage and minimise the burden on DFID country offices.

5.11 Consultations with intended beneficiaries will be an important part of our methodology. They will serve a number of purposes. They will assist us with assessing the relevance of UK programmes to the needs and preferences of women and girls. They will provide feedback on the challenges women and girls face in accessing S&J services, helping us to assess whether the theories of change underlying the programmes are realistic. They will provide feedback on whether women and girls are being actively engaged in the design, delivery and monitoring of UK programmes. They will also provide information on programme impact that can be used to verify the results data generated by the programmes themselves. We note that programming designed to tackle violence against women and girls also needs to engage with men. Our consultations will also assess how well UK programmes engage with those whose behaviour they intend to influence.

5.12 We may convene an expert panel, with eminent individuals from UK development NGOs, academia and/or the UK government, to advise us on methodology, support stakeholder outreach and validate our analysis.

6. Timing and deliverables

6.1 The review will be overseen by Commissioners and implemented by a small team from ICAI’s consortium. The lead Commissioner will be Diana Good. The review will take place during the second and third quarters of 2014, with a final report available during the first quarter of 2015.

Footnotes

- ^ Business Plan 2012-2015, DFID, May 2012, page 10, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/31197/DFIDbusiness-plan2012.pdf.

- ^ DFID’s Results Framework: Managing and Reporting DFID Results, DFID, 2012, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/175715/DFID-external-results.pdf.

- ^ A new strategic vision for girls and women: stopping poverty before it starts, DFID, 2011, page 3, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67582/strategic-vision-girls-women.pdf.

- ^ Explanatory Note on Security and Access to Justice for the Poor, DFID Briefing Note, April 2007.

- ^ Building Stability Overseas Strategy, DFID, Foreign and Commonwealth Office and Ministry of Defence, 2011, page 12, www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32960/bsos-july-11.pdf.

- ^ Building Peaceful States and Societies: A DFID Practice Paper, DFID, May 2010, http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/CON75.pdf.

- ^ A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies Through Sustainable Development, United Nations, 2013, page 9, http://www.post2015hlp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/UN-Report.pdf.

- ^ North, D., Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press, 1990; Ogus, A., The importance of legal infrastructure for regulation (and deregulation) in developing countries, Centre on Regulation and Competition, University of Manchester, Working Paper No. 65, June 2004.

- ^ See the literature cited in Cox, M., Security and justice: measuring the development returns: a review of knowledge, Agulhas Applied Knowledge, August 2008, pages 26-37.

- ^ Golub, S., Beyond Rule of Law Orthodoxy. The Legal Empowerment Alternative, Rule of Law Series Working Papers No. 41, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington D.C., 2003.

- ^ David Cameron, Speech at Al Azhar University, 17 April 2012, https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/transcript-prime-ministers-speech-at-al-azhar-university–10.

- ^ A theory of change for tackling violence against women and girls, DFID How To Note, June 2012, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/67336/how-to-note-vawg-1.pdf.

- ^ Business Case: Evaluation of DFID’s Security and Justice Policy and Programmes, DFID, 2013, http://iati.dfid.gov.uk/iati_documents/4202867.docx.

- ^ See http://www.namati.org/about/.

- ^ CHASE Operational Plan 2012-2015, DFID CHASE, 2012, page 7; Evidence on ‘rule of law’ aid initiatives, GSDR Helpdesk Research Report, October 2013, pages 2-3, http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/HDQ1008.pdf.

- ^ Safety, Security and Justice Topic Guide: Strength of evidence, GSDRC, http://www.gsdrc.org/go/topic-guides/safety/-security-and-justice/challenges-and-approaches/strength-of-evidence.

- ^ Denney, L. and Domingo, P., Security and justice reform: overhauling and tinkering with current programming approaches, ODI Workshop Note, March 2014, http://www.odi.org.uk/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8895.pdf.

- ^ DFID defines a ‘macro-evaluation’ as a ‘quality assessment and synthesis of existing data (evaluative or other) against a common evaluation framework, with the aim of generalising evaluation findings’. Governance Evaluation Strategy, DFID, 2012, quoted in Business Case: Evaluation of DFID’s Security and Justice Policy and Programmes, DFID, undated, http://iati.dfid.gov.uk/iati_documents/4202867.docx.

- ^ Stone, C. et al., Supporting security, justice and development: lessons for a new era, April 2005, http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/CON24.pdf.

- ^ Ball, N. et al., Security and justice sector reform programming in Africa, DFID Evaluation Working Paper 23, April 2007, http://www.oecd.org/countries/sierraleone/38635081.pdf.

- ^ Julio Faundez, Alison Lochhead and Lt. Col. Hugh Evans, Lessons Learned from Selected DFID Security and Justice Programmes: Study to Inform the White Paper Process, DFID, March 2009.

- ^ Thematic Evaluation of European Commission Support to Justice and Security System Reform, Analysis for Economic Decisions (ADE), Volume 1, November 2011, http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/how/evaluation/evaluation_reports/reports/2011/1295_vol1_en.pdf.

- ^ Cox, M., Emele Duituturaga and Eric Scheye, Building on Local Strengths: Evaluation of Australian Law and Justice Assistance, December 2012, http://www.ode.dfat.gov.au/publications/documents/lawjustice-building-on-local-strengths.pdf.

- ^ DFID’s Approach to Anti-Corruption and its Impact on the Poor – Terms of Reference, ICAI, 2014, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/ICAI-ToR-Anti-Corruption-Second-Review.pdf.

- ^ DFID’s Scaling-up of Aid in Fragile States – Terms of Reference, ICAI, 2014, http://icai.independent.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Fragile-States-ToRs-Final.pdf.