The UK’s humanitarian support to Syria

Score summary

DFID has overcome substantial barriers to the delivery of humanitarian assistance in Syria and is providing life-saving support to communities in need. However DFID took too long to put the required staffing and management resources in place, and its approach to learning has not been systematic.

At the outset of the crisis, DFID faced limited options for delivering humanitarian assistance inside Syria. In response, DFID set about investing in independent assessment of humanitarian needs and built a capacity to deliver aid across the border from neighbouring countries. UK aid is now reaching vulnerable people and bringing about positive changes to households and communities in some of the hardest-hit areas of Syria. Given the duration of the crisis, however, we judge that DFID has been slow in evolving its portfolio to incorporate more cash-based programming and support for livelihoods, along with more explicit attention to protection activities.

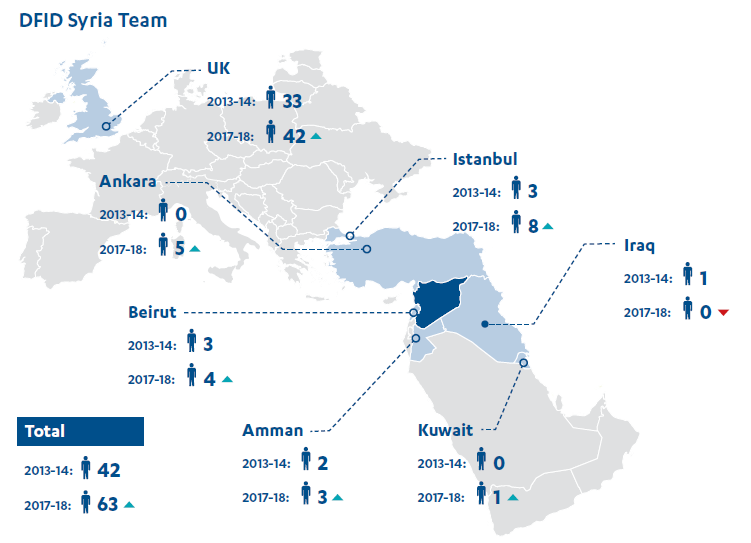

The Syria response was originally managed as a short-term engagement. This persisted even as the crisis grew in scale and complexity. With hindsight, DFID was slow to put in place the necessary staff resources and management capacity to rigorously oversee the response. In time this changed significantly and DFID built up its Syria team and shifted to multi-annual programme funding, with stronger systems for selecting partners, monitoring operations and managing fiduciary risk. Some gaps remain, including around engagement of Syrian partners, attention to safeguarding and independent monitoring.

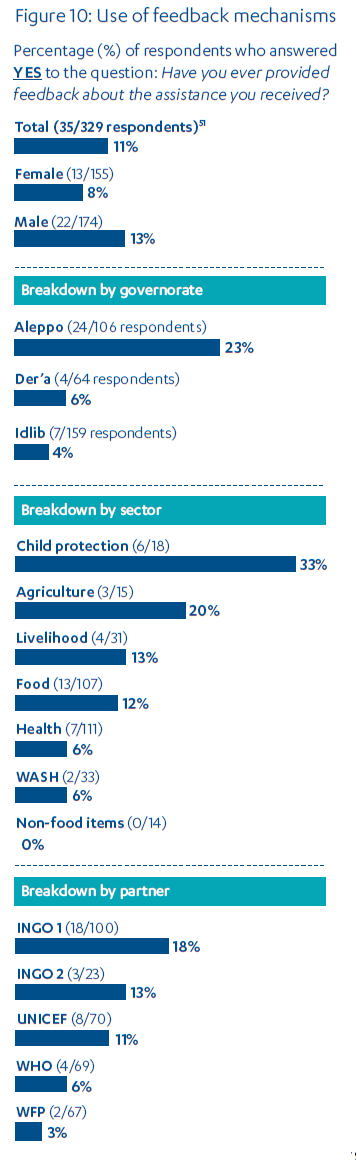

The latest phase of DFID’s humanitarian response and particularly its focus on severity of need has notably been supported by a major focus on data and data analysis. However, on a wider front, DFID’s approach to research, evidence collection and learning in the Syria crisis response has been more limited and not systematic. While beneficiary feedback mechanisms are in place, we found little evidence that the information they provide is directly informing programme design. There is also limited evidence that lessons from the Syria response have been captured more widely to inform future crisis responses.

Overall, we find that the UK Syria humanitarian response merits a green-amber score, in recognition of DFID’s success, particularly since 2015-16, in building a delivery capacity and helping communities in severe need in acutely challenging and changing circumstances.

| Individual question scores | |

|---|---|

| Question 1 Effectiveness: How effectively has the UK responded to humanitarian need in Syria? |  |

| Question 2 Efficiency: How well has DFID managed its delivery chains? |  |

| Question 3 Learning: How well has DFID learned from experience? |  |

Executive summary

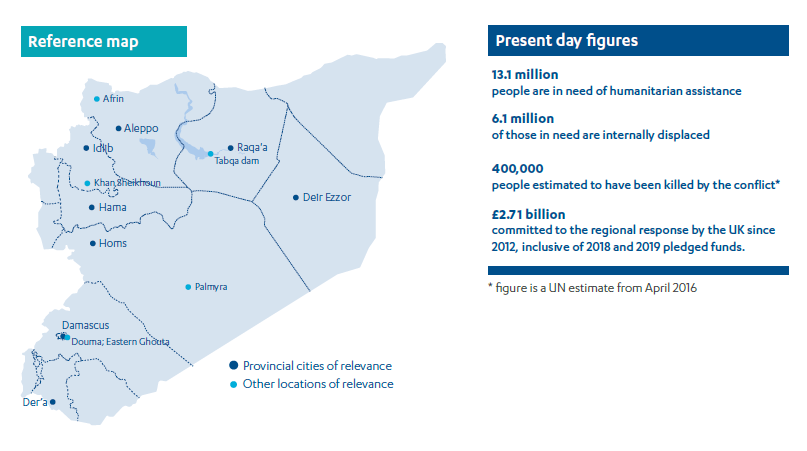

The conflict in Syria has been one of the most brutal in modern history, costing nearly half a million lives, displacing more than 12 million people from their homes, including 5.6 million refugees who fled to neighbouring countries, and leaving 5.6 million people in severe humanitarian need in Syria. In response, the UK has mounted its largest-ever humanitarian operation, committing £2.71 billion to the regional response since 2012, with £910 million allocated for humanitarian operations in Syria.

The complex and dynamic nature of the conflict, with rapidly shifting alliances and frontlines, has made for an acutely difficult operating environment. Lacking a presence in Syria, DFID originally managed its operations from London before building up a regional delivery capacity, operating from bases in Turkey, Lebanon and Iraq.

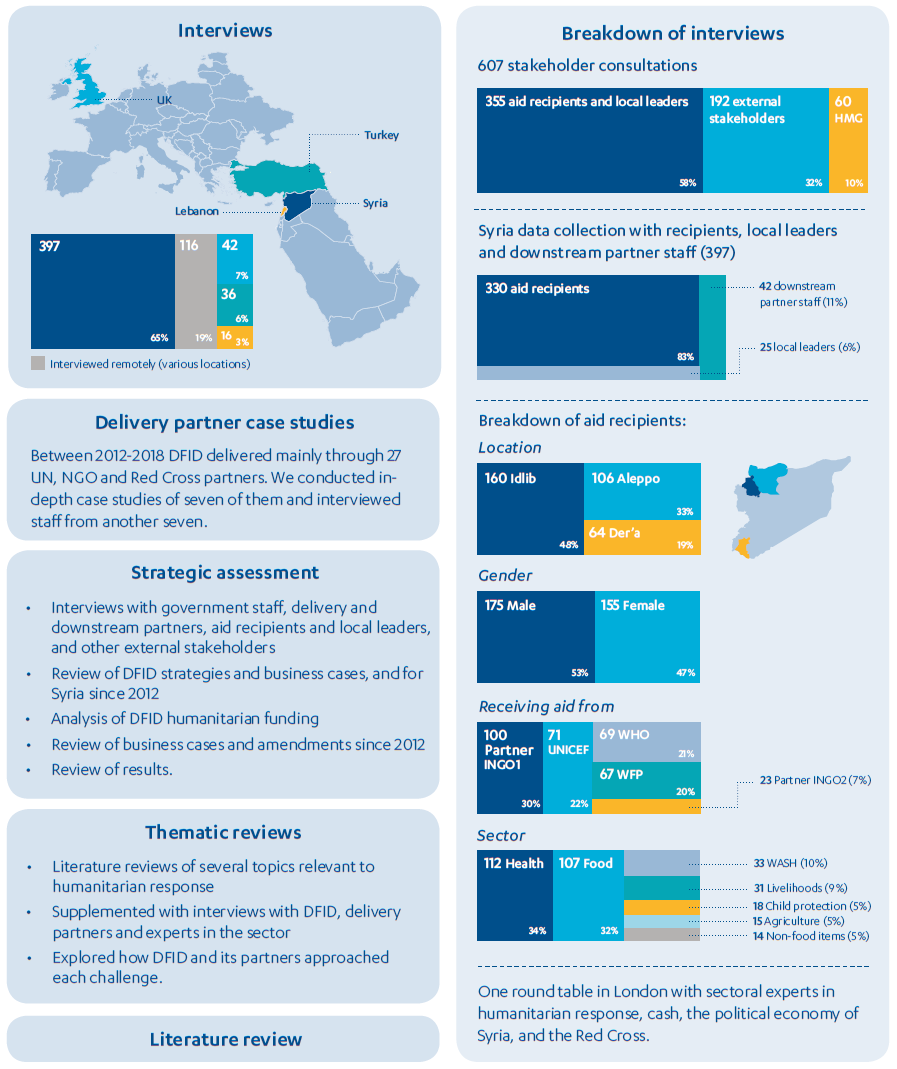

This performance review assesses the effectiveness of UK humanitarian aid in Syria from the beginning of the crisis response in 2012 to the present. It explores how well DFID has identified and reached those in need, whether it has managed its operations efficiently and how well it has learned from experience. In preparing the review, we interviewed past and present DFID staff, consulted staff from 40 of DFID’s delivery and downstream partners, and collected data within opposition-controlled Syria, including interviewing aid recipients and local leaders across 28 communities.

Effectiveness: How effectively has the UK responded to humanitarian need in Syria?

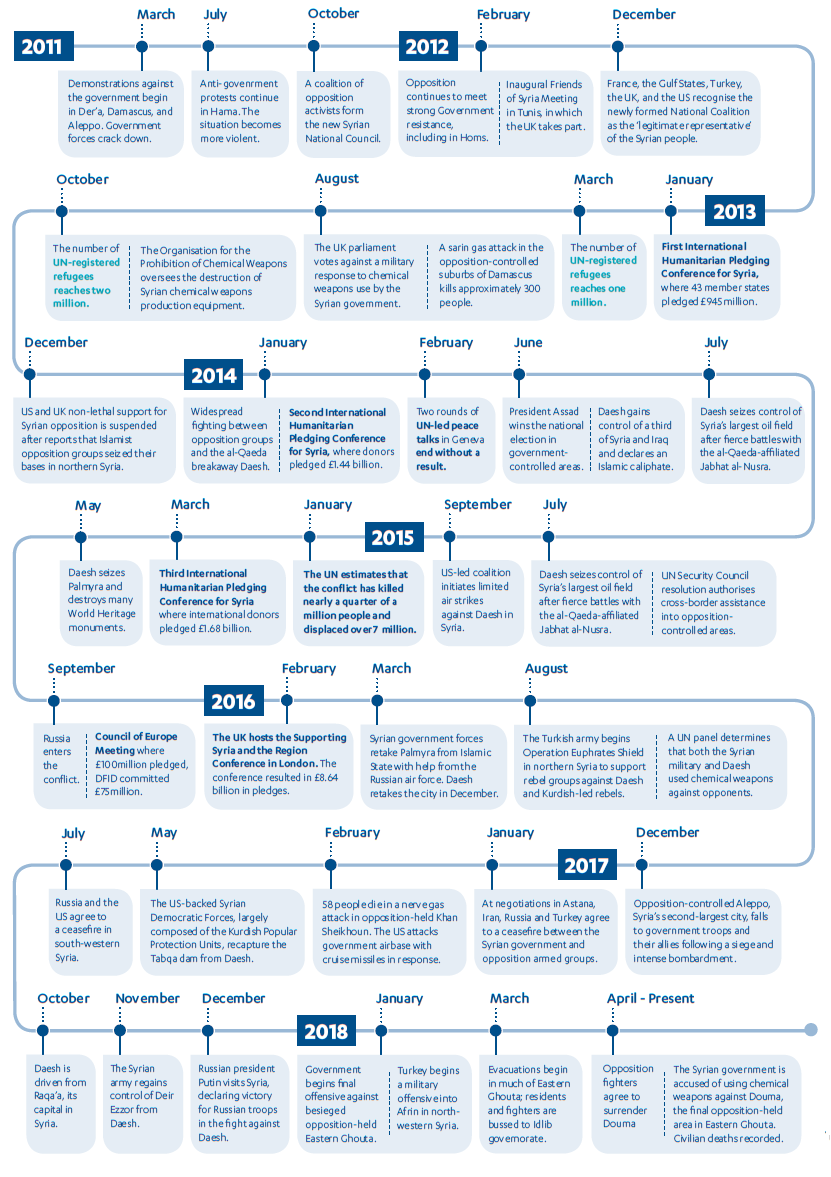

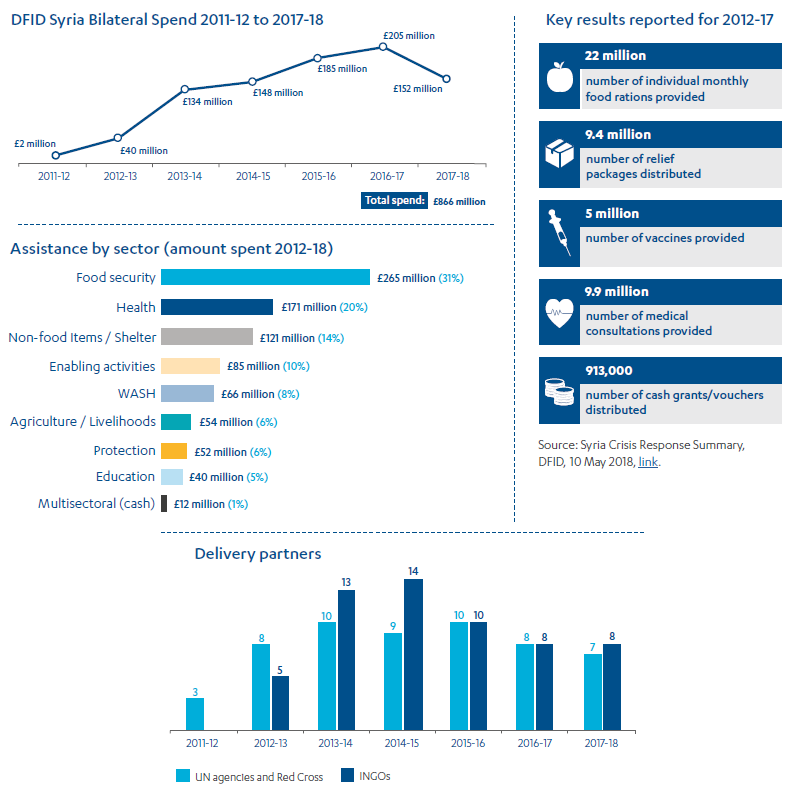

The Syrian conflict began as pro-democracy protests in 2011 and escalated rapidly into a multi-party conflict that pitted the Syrian government against a range of armed opposition groups supported by external powers. In 2014-15, Daesh (also known as Islamic State, ISIL or ISIS) seized control of large parts of the territory. Working in unstable and insecure conditions, the UK has supported a complex international operation to alleviate the suffering of communities across Syria. In the period from 2012 to 2017, DFID reports that it provided 9.4 million relief packages, 5 million vaccines and 22 million individual monthly food rations.

DFID’s initial delivery options were limited to UN and Red Cross agencies operating out of Damascus. As the conflict escalated, it became apparent that the Syrian government was controlling information on humanitarian needs and limiting access to opposition-controlled areas. Working with other donors, DFID gradually built up reliable data on humanitarian need across the country. It also built up other delivery channels, mainly through international non-governmental organisations operating across the border from Turkey and Lebanon. It worked with the Foreign Office (FCO) and other donors to advocate for a UN Security Council resolution authorising the UN to conduct cross-border operations without approval from the Syrian government, enabling a shift to a ‘Whole of Syria’ humanitarian response. It also established an Emergency Response Mechanism that gave it the capacity to respond quickly to spikes in humanitarian need. Although it took time, DFID eventually developed the capacity to deliver life-saving support across Syria, despite the very challenging context.

As it became clear that the information on humanitarian needs in Syria was incomplete, particularly in areas controlled by opposition forces, DFID coordinated with other donors and humanitarian organisations to improve coordination mechanisms and needs assessment tools and processes. From 2014, as these efforts improved the quality of information about humanitarian needs, DFID adopted a targeting approach of ‘severity over scale’ – including prioritising isolated or besieged communities where needs were most acute, even if that meant reaching fewer people overall. Within communities, it directed aid towards the most vulnerable households. Our data collection in Syria, though small in scale, confirmed that UK aid is reaching communities and households in acute need, with appropriate procedures in place to ensure that targeting criteria are fairly applied.

Within the 28 communities we sampled, UK aid had brought about positive changes to the lives of recipients. Distributing food aid and other emergency items had alleviated suffering and allowed recipients to use their own resources on housing and health care. It had enabled some families to send their children back to school. There was also evidence of positive outcomes at the community level, in the form of reduced incidence of local crime, fewer disputes and families having a more optimistic outlook about the future.

However, there are some gaps in the UK assistance. In humanitarian aid, ‘protection’ refers to measures that help make civilians less exposed to risks, particularly from conflict and violence. Protection is one of the pillars of DFID’s strategy in Syria but is very difficult to achieve in the context of ongoing hostilities, which are often directed against civilians. Since 2016, DFID has encouraged its partners to do more to integrate protection activities into their programmes, but this has been held back by a lack of knowledge and experience and still falls short of what would be expected, given the needs.

We also find that DFID has been slow to shift from emergency relief to programming to support recipients’ livelihoods, where security conditions allow. While our interviews found demand for more support in this area, livelihoods programming currently makes up less than 5% of the portfolio. DFID has also made slow progress in its objective of shifting towards cash-based programming, which remains well short of its target of 20% of all assistance by 2019. Lessons from other humanitarian crises suggest that, in the right conditions, moving from food aid to cash payments gives recipients more flexibility to meet their needs and can help to stimulate local food markets.

Overall, DFID’s humanitarian response in Syria has improved significantly over time and is now delivering to communities and households in severe need across a much larger share of the country. We award DFID a green-amber score, in recognition of its achievements in overcoming practical constraints and developing an effective delivery capacity.

Efficiency: How efficiently has DFID managed its response?

The Syria operation was originally planned as a short-term emergency response, in expectation of an early end to the conflict. As the crisis escalated, this stance resulted in heavy burdens being placed on the DFID team, compromising the efficiency of response. We find that DFID was slow to acknowledge the size and complexity of the crisis and to shift from emergency response mode.

From 2014, however, DFID built a more substantial Syria team with greater programme management capacity and broader expertise. This enabled it to diversify its programming and invest in stronger systems and processes. It improved its partner selection processes, discontinuing funding to partners that were not aligned with DFID’s strategic objectives, and improved its level of engagement with partners. It introduced more standardised reporting tools, including an online reporting system that gave it greater oversight of

spending and coverage across the portfolio. Following concerns about its fiduciary risk management practices (including from a past ICAI report), DFID introduced enhanced due diligence processes through its delivery chain. We found that the quality of its due diligence assessments had improved and that delivery partners were being encouraged to share any fraud and corruption problems early and agree on actions to address them. However, the due diligence process did not explicitly address risks around safeguarding aid recipients from sexual exploitation, which has been identified as an issue in the international humanitarian response in Syria. While there have been no specific allegations in respect of UK funding, DFID acknowledges that its efforts to date to address this risk have not been sufficient and is now working to strengthen its systems and processes.

Since 2016, DFID has moved to multi-year funding of its delivery partners, which is intended to reduce transaction costs and encourage longer-term planning. We found that there were indeed substantial benefitsfor DFID and its international non-governmental organisation partners. However, these benefits were not necessarily being passed on to Syrian partners, many of which continue to be engaged on a short-term basis, hampering their ability to retain staff and build capacity. While there are operational reasons for this, connected to the fluid nature of the Syrian conflict, we find that there has not been a systematic approach to building the capacity of Syrian downstream partners.

Since 2016, DFID has engaged third-party monitors to support its delivery partners and verify that aid is being delivered as intended. While the monitoring gives DFID greater confidence in its partners’ own monitoring capacity, we found that the level of verification was not as high as we would expect for an operation of this size, complexity and risk. Between 2016 and 2017, the monitors visited 15 of DFID’s delivery partners at least once. However, the visits are only for one day and partners are allowed too much influence over where the monitors visit. DFID acknowledges these issues and is taking steps to address them.

DFID has improved its assessment and monitoring of value for money. Partners are required to detail their administrative costs and the unit costs of key commodities and outline how they will ensure economy, efficiency and effectiveness. However, we found few instances as yet of DFID using this data to secure improvements in economy or efficiency.

Overall, since DFID began in 2014 to move out of emergency response mode and provide more management resources for its Syria operations, there have been significant improvements in DFID’s partner selection and engagement, reporting processes and fiduciary risk management, meriting a green-amber score. However, there are still some gaps that need to be addressed, particularly regarding independent monitoring, support for Syrian partners and safeguarding.

Learning: How well has DFID learned from experience?

While DFID Syria set itself the goal of being evidence-based and promoting continuous improvement, we find its learning activities to be small in scale and unsystematic. Although it has invested in some relevant research, this is not based on a clear strategy and there is little active dissemination of the outputs to the delivery partners it is intended to influence. There have been very few programme evaluations, although these are now a requirement of current funding agreements.

DFID encourages its partners to collect feedback from aid recipients on their operations in Syria, but most devolve responsibility for this to their downstream partners. The examples we reviewed consisted mainly of complaints mechanisms; while these have generated useful feedback on operational issues, we find limited evidence that voices of recipients have informed wider learning and programme design.

While DFID Syria has adapted its management processes during the crisis, there is little evidence that DFID is systematically drawing on this at a central level to inform its response to future complex crises. A recent DFID discussion paper proposes some useful operating principles for protracted crises, but DFID has yet to adopt a set of doctrines, processes and tools, drawing on its Syria experience, for managing its response to complex crises. We therefore award DFID an amber-red score for learning.

Conclusions and recommendations

Overall, we find that DFID’s humanitarian response in Syria has improved substantially in recent years. DFID has built capacity to overcome the restrictions set by the Syrian government and to reach communities in need across the country, despite an extremely challenging operating environment. However, there have been significant time lags in putting in place the management systems and capacities required to manage the response efficiently. While DFID has adapted in response to practical challenges, its approach to research and learning has not been systematic.

We offer the following recommendations, both for the Syrian operation and for DFID’s response to future crises.

Recommendation 1

As conditions allow, DFID Syria should prioritise livelihoods programming and supporting local markets, to strengthen community self-reliance.

Recommendation 2

DFID Syria should strengthen its third-party monitoring approach to provide a higher level of independent verification of aid delivery, and continue to explore ways of extending it into government-controlled areas.

Recommendation 3

DFID Syria should support and encourage its partners to expand their community consultation and feedback processes and ensure that community input informs learning and the design of future humanitarian interventions.

Recommendation 4

DFID Syria should identify ways to support the capacity development of Syrian non-governmental organisations to enable them to take on a more direct role in the humanitarian response.

Recommendation 5

DFID Syria should develop a dynamic research and learning strategy that includes an assessment of learning needs across the international humanitarian response in Syria and a dissemination strategy.

Recommendation 6

DFID should ensure that lessons and best practice from the Syria response are collected and documented, and used to inform both ongoing and future crisis responses.

Recommendation 7

In complex crises, DFID should plan for the possibility of lengthy engagement from an early stage, with trigger points to guide decisions on when to move beyond emergency funding instruments and staffing arrangements.

Recommendation 8

Building on DFID Syria’s reporting system, DFID should invest in reporting and data management systems that can be readily adapted to complex humanitarian operations.

Introduction

The ongoing conflict in Syria, which began with pro-democracy protests in 2011, is one of the most brutal in modern history. Eastern Ghouta, an opposition-held area of Damascus that largely fell to government forces in April 2018 after a five-year siege, encapsulates the catastrophe that has befallen Syrians. Nearly 400,000 residents were subject to bombardment by government forces and their allies, reportedly prevented from leaving by armed opposition groups and denied access to aid for months at a time. Across the country, civilian populations have been victims of a war with multiple parties, fluid alliances and rapidly shifting frontlines, resulting in a humanitarian crisis on an extraordinary scale.

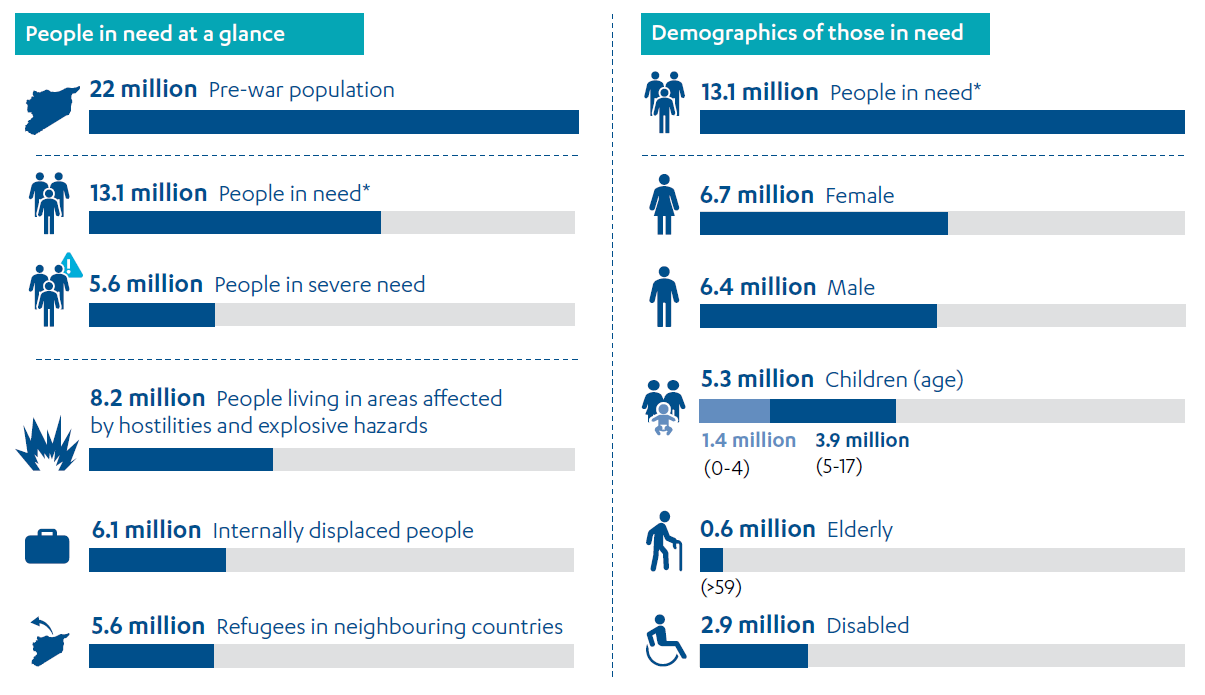

Figure 1: The Syria crisis in numbers (November 2017)

* People in need refers to people whose physical security, basic rights, dignity, living conditions or livelihoods are threatened or have been

disrupted, and whose current level of access to basic services, goods and protection is inadequate to re-establish normal living conditions within their accustomed means without assistance. People in severe need refers to those facing more severe forms of deprivation in terms of their security, basic rights and living conditions and face life-threatening needs requiring urgent humanitarian assistance.

Sources: 2018 Humanitarian Needs Overview – Syrian Arab Republic, link. Syria Crisis Response Summary, DFID, May 2018.

In response, the UK has undertaken its largest-ever humanitarian operation, committing £2.71 billion to the regional response since 2012.4 The support in Syria has included emergency food aid, the restoration of basic services such as water, health and education and, in more stable parts, assistance with restarting livelihoods.

For DFID, which managed the response, the operational challenges have been substantial. DFID did not have a country office in Syria and had been reducing its presence in the Middle East region for some years before the onset of the crisis. It therefore needed to build a delivery capacity across the region, operating from bases in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan. The operational environment within Syria was also very challenging, in the midst of a large-scale multi-party conflict.

Humanitarian Assistance comprises disaster relief, food aid, refugee relief and disaster preparedness. It generally involves the provision of material aid including food, medical care and personnel and finance and advice to save and preserve lives during emergency situations and in the immediate post-emergency rehabilitation phase; and to cope with short and longer term population displacements arising out of emergencies.

DFID glossary

This performance review assesses the effectiveness of UK humanitarian aid in Syria since the beginning of the crisis response in 2012. It explores how well DFID has identified and reached its intended recipients, and whether it has managed to achieve the best possible results given the challenging circumstances. It also examines how well DFID has learned from the Syria response.

Box 1: What is an ICAI performance review?

ICAI performance reviews examine how efficiently and effectively UK aid is being spent on an area, and whether it is likely to make a difference to its intended recipients. They also cover the business processes through which aid is managed to identify opportunities to increase effectiveness and value for money.

Other types of ICAI reviews include: impact reviews, which examine results claims made for UK aid to assess their credibility and their significance for the intended recipients; learning reviews, which explore how knowledge is generated in novel areas and translated into credible programming; and rapid reviews, which are short, real-time reviews of emerging issues or areas of UK aid spending that are of particular interest to the UK Parliament and public.

The review focuses solely on DFID-funded humanitarian assistance in Syria. It does not include UK support to Syrian refugees throughout the region or stabilisation programming funded through the Conflict, Security and Stability Fund (CSSF). Our review questions are set out in Table 1. The review follows a 2016 National Audit Office report on DFID’s response to crises, which explored capacity issues within the department and raised questions as to how well it manages the shift from short-term emergency response to sustained engagement in protracted crises.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Effectiveness: How effectively has the UK responded to humanitarian need in Syria? | • How well has the UK identified humanitarian needs? • How effective and, where appropriate, innovative has the UK’s assistance been in addressing and meeting humanitarian needs? • How well has the UK coordinated with other humanitarian actors? |

| 2. Efficiency: How well has DFID managed its delivery chains? | • To what extent has DFID selected and managed its implementing partners so as to secure value for money? • How well has DFID monitored its portfolio to drive improvements in value for money? |

| 3. Learning: How well has DFID learned from experience? | • How well has DFID engaged with research and lesson-learning and disseminated the results from these processes? • To what extent has DFID collected feedback from intended beneficiaries and responded to it? • To what extent has DFID adapted its humanitarian operations in response to lessons learned? • To what extent has DFID innovated and adapted its humanitarian operations in response to lessons learned (other than beneficiary feedback)? |

Methodology

Our review methodology included four interconnected components that we used to triangulate information and findings to give us more assurance of the robustness of our evidence:

- Strategic review: We analysed the strategies and planning documents that governed the response, as well as management data from DFID on expenditure patterns and human resources. Coupled with interviews with UK government staff, this enabled us to explore the evolution of the response at the strategic, financial and managerial levels.

- Delivery partner case studies: DFID’s support in Syria is provided through delivery partners, including UN agencies and international non-government organisations (INGOs). Most of these, in turn, subcontract Syrian organisations to distribute aid. Of the 27 partners that have received direct DFID funding since 2012, we selected seven for detailed analysis: three UN agencies and four INGOs (see Annex 1). For each case study, we undertook interviews with DFID, the delivery partners and selected downstream partners at each level of the delivery chain, both at the organisations’ headquarters and in Syria. We augmented this with interviews with delivery partners not included in the case studies, enabling us to assess whether the findings of our case studies were representative.

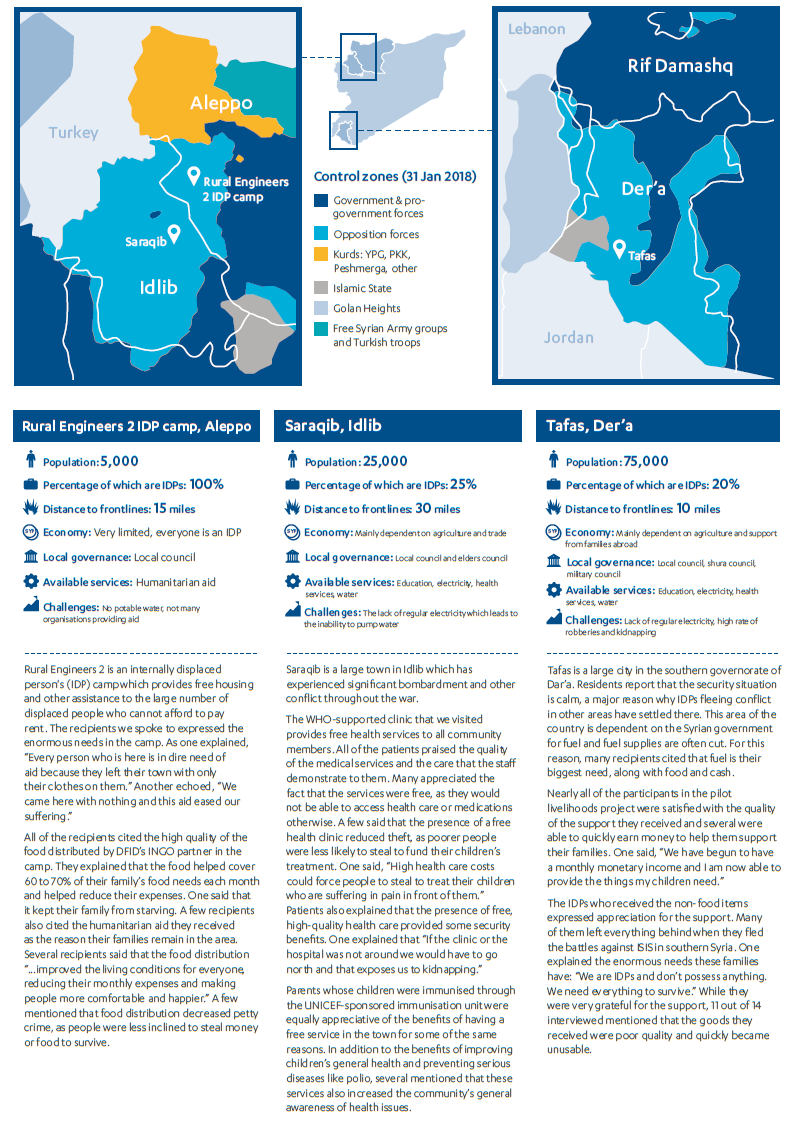

- Interviews in Syria with affected communities: Working with a team of Syrian enumerators, we conducted in-person interviews with 330 recipients of DFID-funded assistance. Our programme sample included agriculture, child protection, food, health, livelihoods, non-food items, and water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). The enumerators visited 28 opposition-controlled

communities in three governorates in Syria: Aleppo and Idlib in the north-west and Der’a in the south. They also interviewed 67 community leaders and downstream partner staff. This component allowed us to understand the final link in the delivery chain: the aid recipient. - Thematic case studies: We conducted brief literature reviews of several topics relevant to the humanitarian response, including the use of cash transfers for humanitarian relief, data and knowledge management, and innovation. We supplemented the reviews with interviews with DFID, delivery partners and experts in the field, exploring how DFID and its partners approached each challenge.

Overall, we interviewed over 600 people in the UK, Syria and neighbouring countries, either in person or remotely (see Figure 2).

Box 2: Limitations to our methodology

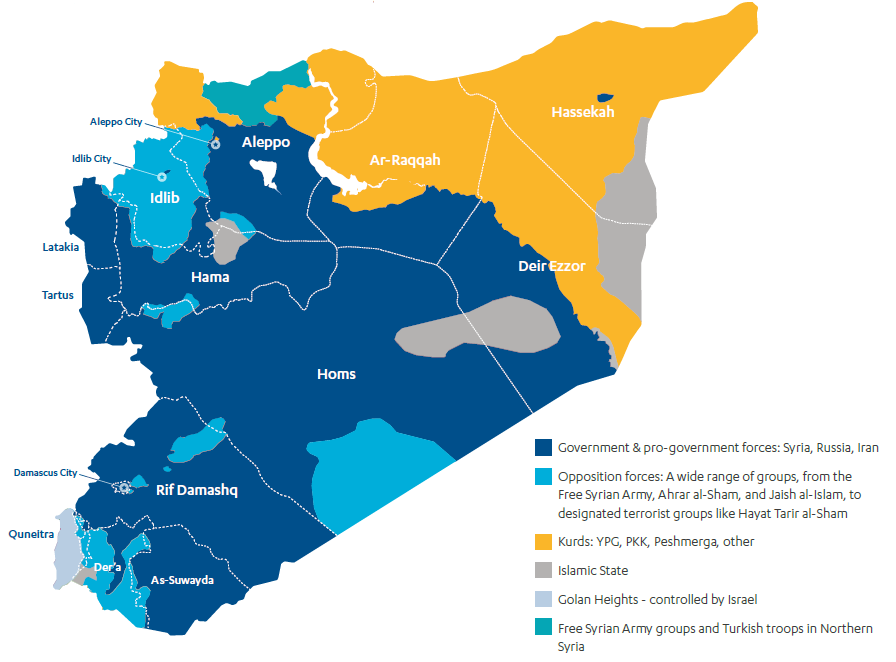

There are several limitations to our methodology created by the difficulty of conducting data collection in Syria and building a representative picture of a highly complex and diverse context. Control of the country is divided among warring factions, including the government and its allies, Western-backed largely Kurdish forces, the Turkish military and its allies, and a variety of armed groups, some with extremist ties. Social and economic dynamics vary widely between communities, making it difficult to draw generalisations from our sample across 28 communities in three governorates.

Our data collection within Syria was limited to opposition-held communities, where we had access. This limits the scope of our findings. We also had limited access to DFID delivery partners operating in government-controlled areas: while we were able to interview some in person in Beirut, most of our engagement with them was by telephone. The Syrian Arab Red Crescent, a downstream partner for nearly all of DFID’s delivery partners operating in government-controlled areas, declined our requests for interviews.

Additionally, we drew on information from DFID’s delivery partners to identify our sample of downstream partners and communities, which introduced a risk of bias into our data. That risk also accompanies interviews with recipients in an ongoing conflict, who may be reluctant to provide negative feedback on humanitarian assistance for fear that it could be stopped. We have sought to guard against bias by triangulating across data sources, and by being circumspect about the degree to which it is possible to draw general conclusions from our data.

Figure 2: Summary of data collected

Background

The Syrian conflict

Figure 3: Map of Syria with zones of control, accessed 31 January 2018

Source: Liveuamap – Syria (accessed 31 January 2018).

Emerging from pro-democracy protests in 2011, the Syrian conflict quickly escalated into a regional war that pitted armed opposition groups, some supported by Western and Gulf countries, against government forces and their Iranian and Hezbollah allies. In 2014-15, Daesh (also known as Islamic State, ISIL or ISIS) seized control of large portions of Iraq and Syria. In September 2015, Russia committed forces to support the Syrian government military and its allies, dramatically shifting the shape of the conflict and leading at the end of 2016 to the fall of Aleppo, Syria’s second-largest city and one of the opposition’s main strongholds. In August 2016, Turkey also entered the conflict, establishing a buffer zone in northern Syria between two areas of Kurdish control. In 2017, predominantly Kurdish forces backed by the US pushed Daesh out of most of the areas they controlled. This led to another Turkish military operation into Kurdish areas in north-eastern Syria in early 2018. At the time of writing in April 2018, Syrian forces had taken the Damascus suburb of Eastern Ghouta and evacuations of opposition forces and civilians were underway.

The conflict has included the repeated use of chemical weapons against civilian populations, siege warfare and the bombardment of civilian infrastructure such as hospitals and schools. Almost half a million Syrians have been killed. The degradation or collapse of public services have left 13.1 million people – over half of the pre-war population of 22 million – in need of humanitarian assistance, with 5.6 million in severe need. Around 6.6 million refugees have fled the country, including 5.6 million refugees to the neighbouring countries of Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan and an estimated additional 1 million to Europe. Forced internal displacement has left 6.1 million Syrians without homes, many of them multiple times.

Figure 4: Key events in the Syrian conflict 2011-2018

The UK’s humanitarian response

The UK responded to the Syrian conflict with its largest-ever humanitarian operation. To date, DFID has committed £2.71 billion to the wider regional response, including support for refugees in neighbouring countries. Of this, £910 million was allocated for aid in Syria. Figure 5 provides an overview of DFID’s funding in Syria. The largest item has been emergency food distribution, at 31% of expenditure between 2012 and 2018, followed by health (20%), non-food items and shelter (14%) and water, sanitation and hygiene (8%). The pattern is typical of an emergency response in a conflict zone.

In the early phase, DFID provided its support mainly through multilateral organisations operating from Damascus. As the crisis deepened, the scale of the response expanded rapidly and came to include a large number of delivery partners, many delivering aid into Syria from neighbouring countries. In 2016, DFID adopted a new strategic plan for its Syria operations, outlining four objectives:

- support conflict reduction and peacebuilding

- build resilience

- protect civilians

- strengthen the enabling environment.

In this strategy, humanitarian assistance falls under the objective of protecting civilians. This is to be complemented where possible with programming to build resilience by restarting agricultural markets and restoring livelihoods, to reduce the population’s dependence on aid. DFID’s strategy also emphasises recent global policy commitments under the Grand Bargain, including the use of flexible, multi-year funding (see Box 3).

Figure 5: DFID’s response

Box 3: The World Humanitarian Summit and the Grand Bargain

In January 2015, against the background of a growing shortfall in global humanitarian funding, the UN created a high-level panel on humanitarian financing to explore ways of addressing the funding gap. A year later, the panel recommended a set of actions to “deepen and broaden the resource base for humanitarian action” and “improve delivery through ‘A Grand Bargain on efficiency’”. This led to agreement among a group of 30 donors and humanitarian agencies at the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit in 2016 on 51 commitments across ten workstreams, known as the Grand Bargain. The commitments include:

- Transparency: Make data on humanitarian funding transparent and available to all.

- Frontline responders: Greater inclusion for national and local organisations who are often delivering the bulk of humanitarian assistance.

- Cash-based programming: Increase use of cash in humanitarian response and strengthen monitoring.

- Reduce management costs: Reduce duplication of management and other costs while providing transparent and comparable cost structures.

- More joint and impartial needs assessments: Single comprehensive overview of humanitarian needs and increased collaboration on data collection.

- Participation revolution: Improved engagement with communities and streamlined feedback mechanisms; greater utilisation of feedback in programme design activities.

- More multi-year humanitarian funding: Increase multi-year, collaborative and flexible planning and funding instruments, with funding recipients applying the same financial terms that they received from donors.

- Less earmarking: Reduce the amount of directed funding, reaching a global target of non- and softly-earmarked contribution representing only 30% of humanitarian funding by 2020.

- Harmonised and simplified reporting requirements: Simplify and harmonise reporting requirements by the end of 2018.

- Strengthening engagement between humanitarian and development actors: Use existing resources to reduce humanitarian needs with the aim of contributing to long-term global development goals.

There is ongoing work under each workstream, each co-led by a donor and an operational agency, to translate the commitments into actions and agreed standards. The UK leads the workstream on cash-based programming, with the World Food Programme (WFP).

Operating context

A complex set of dynamics converged to make delivering humanitarian assistance in Syria a particularly difficult undertaking:

- Lack of presence: In the period before the Syria crisis, DFID had scaled back its presence in the Middle East and North Africa region (apart from Yemen and the Occupied Palestinian Territories), to concentrate its resources in low-income countries. As a result, DFID had no recent experience of the political and operational context. The UK closed its embassy in Damascus in early 2012, leaving no standing UK presence in Syria to oversee the response.

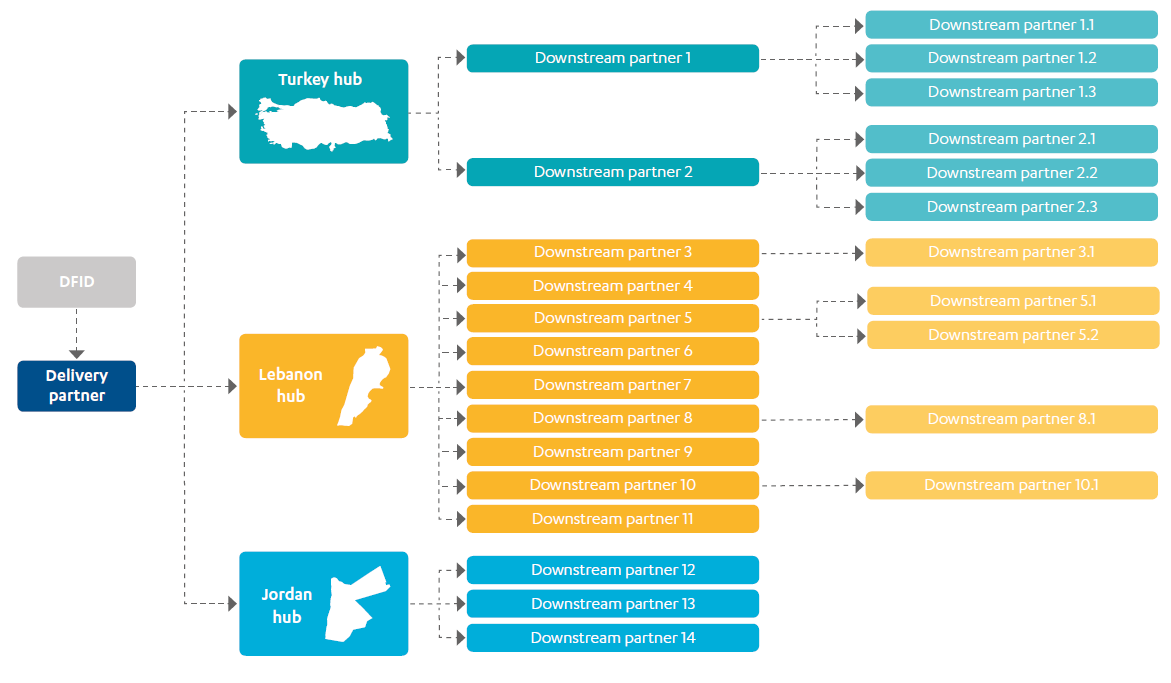

- Remote management and multiple hubs: Like DFID, many of its delivery partners also operate remotely from hubs in Turkey, Jordan, Iraq and Lebanon. To access people in need in Syria, most of them are reliant on Syrian partner organisations, who deliver the bulk of their assistance. Within Syria, UN agencies and the International Committee of the Red Cross also work through Syrian partners. This makes for complex delivery arrangements: delivery partners have multiple operating hubs and downstream partners, often working through long delivery chains (see Figure 6). The need to work across borders increases the costs of delivery in Syria, while operating from multiple countries forces partners to reconcile different national rules and regulations, leading to higher management costs.

Figure 6: Example of a delivery chain for one DFID partner in Syria

Note: DFID has developed and maintains delivery chain diagrams for each project which are informed by data reported by partners in the downstream partner list in the logframe workbook. As the figure shows, the partner reaches Syria from three hubs (Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan) and has 14 immediate downstream partners. Six of those 14 downstream partners have an additional 11 downstream partners between them. Source: DFID, 2017.

- Relationship with the Syrian government: Early in the crisis, the UK publicly declared its support for the Syrian opposition,13 bringing an end to diplomatic contact between the two governments. However, under its mandate, the United Nations could only operate with the consent of the Syrian government. Its continued presence in Damascus and cooperation with the government led to deep distrust from partners in opposition areas. The Syrian government also compelled some delivery partners to choose between maintaining a presence in Damascus or continuing their work in opposition-held areas. This situation politicised the choice of humanitarian delivery channels, undermined coordination efforts and led to parallel delivery mechanisms for different parts of the country.

- A fluid operating environment: The operating environment in Syria is both uniquely challenging and highly changeable. Control of the country is fragmented, frontlines shift frequently, and the intensity of conflict is unpredictable. Parts of the country can be stable for lengthy periods while others face daily fighting or are besieged. Populations are frequently displaced, sometimes multiple times and into areas devastated by years of fighting. DFID staff have described the situation as multiple crises within a protracted crisis.

- Nascent civil society at community level: Civil society organisations were not well established in Syria before the conflict but emerged throughout much of the country to support communities in need. Most of DFID’s delivery partners rely on these organisations to deliver aid (referred to as “downstream partners” in this report). Because of their access to communities and understanding of local conditions, they are a critical link in DFID’s delivery chain. As new organisations, however, they are often unfamiliar with humanitarian principles and the norms of the humanitarian system. Many lack experience with donor requirements for accountability and value for money.

Findings

Effectiveness: How effectively has DFID responded to humanitarian needs in Syria?

In this section, we assess how well DFID has identified and responded to humanitarian needs in Syria. We examine the evolution of the response and the work that went into building up an accurate picture of humanitarian needs. We draw on our interviews with aid recipients in Syria to assess whether assistance is reaching people in need and what impact it is having on their lives.

DFID has successfully overcome major barriers to the delivery of relief across Syria

At the beginning of the crisis, DFID’s choice of delivery partners was limited to those working from government-controlled Damascus. DFID followed its usual approach for rapid-onset emergencies, channelling funding primarily through the UN humanitarian system and the Red Cross. It did so through a set of ‘umbrella’ business cases: single programme documents covering multiple partners, without detailed design of individual interventions. This allowed funds to be mobilised quickly, without lengthy design and approval processes.

As required by their mandate, UN humanitarian agencies operated in Syria under the authority of the Syrian government. The Syrian government from the outset exercised a substantial degree of control over their operations. It designated the Syrian Arab Red Crescent both as the coordinating body for humanitarian operations, supplanting the usual role of the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and as the principal downstream delivery partner for assistance. It also placed tight controls on information flows, with a ban on media reporting and restrictions on UN agencies publishing details of their work.

As the response progressed, it became apparent that opposition-controlled areas of the country were underserved. From 2013, DFID and other like-minded donors (including the EU, the Netherlands and the US) worked to build a delivery capacity that was beyond the control of the Syrian government and able to operate impartially across the territory. It did so primarily by working with international non-government organisations (INGOs) operating across the Syrian border, from Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. DFID encouraged UK-based INGOs to move to, or scale up in, the region, to increase its delivery options. Building a cross-border delivery capacity from neighbouring countries took a considerable amount of time. The new delivery partners lacked expertise on Syria and were hampered by the ongoing conflict. Eventually, however, DFID was able to overcome some of the constraints set by the Syrian government and develop a capacity to reach communities in need across the territory. This was a significant achievement in difficult circumstances, which considerably improved the effectiveness and impartiality of the response. We note, however, that humanitarian operations in government controlled areas continued to operate from Damascus under the authority of the Syrian government, constraining DFID’s ability to direct and monitor its operations.

Working with others, DFID has improved needs assessment and coordination, strengthening the international response

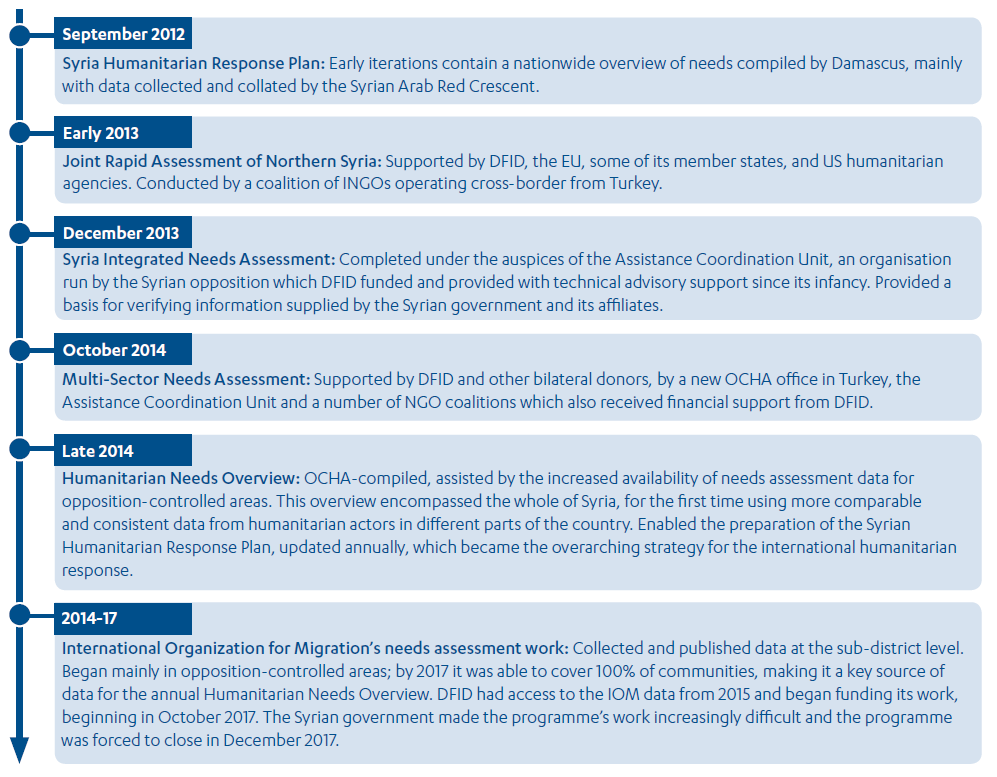

A key part of this shift in approach was developing an independent capacity to assess humanitarian needs across Syria. Reliable, detailed and up-to-date information on humanitarian need is essential both for effective targeting of relief operations and for coordination among multiple humanitarian actors. Recognising that Syrian government-controlled information was incomplete and unreliable, from 2013 DFID supported several independent initiatives to collect data in opposition-controlled areas (see Figure 7).

Along with the EU, the US and other donors, it supported a Joint Rapid Assessment of Northern Syria in 2013, carried out by a coalition of INGOs operating across the border from Turkey. It provided technical and financial support to the Assistance Coordination Unit, an organisation run by the Syrian opposition. The unit coordinated a Syria Integrated Needs Assessment, published in December 2013. These initiatives provided DFID and its donor partners with the first independent picture of needs across the country and a means of cross-checking information generated by the Syrian government and its affiliates.

Using the information collected through these assessments, the UK – working with other donors – helped to galvanise a shift of international policy on humanitarian access in Syria. Before July 2014, UN agencies could only conduct cross-border humanitarian operations with the consent of the Syrian government, which was usually withheld. UN Security Council Resolution 2165 gave them formal authorisation to access opposition-controlled areas through specified border crossings without government permission. According to key stakeholders, DFID and the Foreign Office (FCO) worked closely together to make the case for this change.

The Security Council…

Deeply disturbed by the continued, arbitrary and unjustified withholding of consent to relief operations and the persistence of conditions that impede the delivery of humanitarian supplies to destinations within Syria, in particular to besieged and hard-to-reach areas…

Decides that the United Nations humanitarian agencies and their implementing partners are authorized to use routes across conflict lines and the border crossings of Bab al-Salam, Bab al-Hawa, Al Yarubiyah and Al-Ramtha, in addition to those already in use, in order to ensure that humanitarian assistance, including medical and surgical supplies, reaches people in need

throughout Syria through the most direct routes, with notification to the Syrian authorities.

UN Security Council Resolution 2165.

Resolution 2165 had important implications for the coordination of the international humanitarian effort. OCHA was able to establish coordination offices in Gaziantep (eastern Turkey) and Amman (Jordan). It set up its standard ‘cluster’ coordination mechanism, where working groups of humanitarian actors share information and coordinate operations in particular clusters, such as food security or health. The Humanitarian Needs Overview in late 2014, for the first time, encompassed the whole of Syria, with more standardised data. This, in turn, enabled the Syrian Humanitarian Response Plan, updated annually, to become the overarching strategy for the international humanitarian response across the whole of Syria. From 2015, OCHA established pooled funds (through its Emergency Response Fund) in each of the neighbouring countries, which facilitated coordination and capacity building of Syrian non-governmental organisations. DFID has contributed to that pooled funding mechanism.

The strengthening of data collection and international coordination has been a gradual process, in the face of continuing practical challenges. While the annual Humanitarian Needs Overviews have improved in coverage and quality, continuing restrictions on data collection limit the level of local detail and therefore their usefulness for informing programming. Nonetheless, we find that DFID’s investments in data collection and coordination made an important contribution not just to the targeting of UK humanitarian aid but also to the overall shape of the international response.

Figure 7: Timeline of work to assess humanitarian needs within Syria

DFID’s decision to prioritise populations with the most severe needs was appropriate

As the quality and coverage of needs assessment data improved, DFID began directing aid towards geographical areas based on the severity of humanitarian need, rather than numbers of people in need. A significant share of its support was directed towards opposition-controlled areas that were underserved by the UN and where the humanitarian need was most acute at that point in the crisis. While continuing to contribute to the UN’s overall humanitarian response, it also began to place conditions on its funding to UN agencies, to encourage them to target more assistance towards severely affected areas. Along with like-minded donors such as the EU and Germany, DFID also advocated for changes to the targeting principles in the Humanitarian Response Plan, which governs the overall UN response, with some success.

Prioritising ‘severity over scale’ – that is reaching communities where needs were most acute, even if this meant reaching fewer people overall – is consistent with generally accepted humanitarian principles (see Box 4). DFID’s 2017 Humanitarian Reform Policy affirms that, while prioritising severity of need may involve higher unit costs, this can still represent value for money when the principle of equity is considered.

Box 4: International humanitarian principles

DFID aligns its programming with the four core principles that are widely recognised as guiding international humanitarian operations:

- Humanity: Human suffering must be addressed wherever it is found. The purpose of humanitarian action is to protect life and health and ensure respect for human beings.

- Neutrality: Humanitarian actors must not take sides in hostilities or engage in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature.

- Impartiality: Humanitarian action must be carried out on the basis of need alone, giving priority to the most urgent cases of distress and making no distinctions on the basis of nationality, race, gender, religious belief, class or political opinions.

- Independence: Humanitarian action must be autonomous from political, economic, military or other objectives that any actor may hold in areas where humanitarian action is being implemented.

This targeting approach was nonetheless controversial. Some multilateral partners told us of their view that the decision to prioritise smaller numbers of people with more severe needs in largely opposition held areas (including besieged areas) was a partisan attempt to strengthen opposition resistance to Syrian government forces. (We note that, given the UN’s obligation to work with and through the Syrian government in Damascus, delivering aid solely through the UN would equally have been open to criticisms of partisanship.) Some multilateral partners also claimed that DFID’s conditionality was administratively burdensome and unnecessary, as their own methodologies allowed them to target assistance effectively to the most severe needs across Syria.

DFID also identified shortcomings in the UN system for responding to spikes in humanitarian need. It set up its own Emergency Response Mechanism as a quick and flexible funding instrument, based on past experience in Somalia and South Sudan. It allows DFID to call for proposals from partners (typically existing partners that have already been through the due diligence process) as soon as a new crisis emerges. DFID reviews these proposals rapidly and aims to release funds within 72 hours of approval. This has allowed DFID to be more flexible in responding to acute need. For example, in late 2017, it used the Emergency Response Mechanism to preposition relief supplies in Eastern Ghouta, in preparation for an anticipated government offensive.

Overall, we find that DFID’s approach to the targeting of its humanitarian assistance was an appropriate response to the available evidence on need, and consistent with the humanitarian principles that the UK espouses. Furthermore, we find that placing additional conditions on funds to UN agencies was defensible, where it was done to improve the targeting of the response. We come back to the question of whether this caused efficiency losses in paragraphs 4.68 and 4.69.

UK assistance is reaching communities and individuals in need

DFID’s vulnerability criteria determine which households are eligible for humanitarian assistance. They consider economic status, size of household, numbers of dependents and people with disabilities, and whether the household is female-headed, among other factors. DFID delivery partners are obliged to draw up lists of recipients according to these criteria.

Through our interviews in Syria, we assessed – on a small scale – whether these criteria were appropriate and being complied with. Feedback from recipients, local leaders and downstream partner staff all suggested that the criteria matched community perceptions of need. Most recipients (83% of 330) and local council representatives (80% of 25) told us that the assistance was reaching the most vulnerable people – although many also expressed the view that need was high across the board. Most of the recipients described themselves as falling within the vulnerability criteria, with many describing extremely precarious situations.18 We confirmed that DFID’s partners have processes in place to investigate any complaints they receive about who is (or is not) included in the beneficiaries lists.

There are, however, local challenges to effective targeting that need to be overcome. In some areas, local leaders attempt to control recipient lists, which can make it difficult for downstream partners to follow DFID’s targeting principles (see Box 5). Ongoing conflict and instability also inhibit accurate targeting. Overall, while no targeting approach is foolproof, our data provides a clearer level of assurance that DFID’s processes for prioritising vulnerable people are generally effective.

Box 5: Validating beneficiary lists

We encountered concern from some delivery partners about the role played by local councils in drawing up beneficiary lists. Some councils select recipients according to their own criteria, and in some instances council lists were found to have improperly included relatives and acquaintances. Most downstream partners informed us that they review and correct these lists, as required under the terms of DFID funding. One reported that, on one occasion, it had threatened to withdraw its assistance unless the local council allowed it to select recipients based on the vulnerability criteria. However, a few partners told us that they had, on occasion, accepted the lists in order to preserve good working relationships with local councils.

There is evidence of a range of positive results from UK assistance

In the period from 2012 to 2017, DFID reports that it provided 9.4 million relief packages, 5 million vaccines and 22 million individual monthly food rations (see Figure 5). In 2016-17 DFID funding provided 4.9 million people with clean water and 3.5 million people with sanitation or hygiene programmes. Around 432,000 children received education services, while over 351,000 children and pregnant and lactating women received nutritional support. We have not verified these figures, although we have reviewed DFID’s systems for collecting and aggregating monitoring data from its partners.

These are output-level figures, recording the volume of assistance that DFID has provided, rather than its outcomes, on which there is little data. This is common in humanitarian emergencies: delivery partners count the number of people who have received aid but, given the emergency conditions, rarely attempt to measure what difference it has made in their lives. Given limited resources and difficult operating environments, priority is given to maximising the provision of life-saving support, rather than to more elaborate monitoring and evaluation. However, in some of its most recent programmes in Syria, DFID has begun to require delivery partners to report on outcome indicators and to conduct mid-term and end-of-programme evaluations.

To gain a better picture of the difference that UK humanitarian aid has made, we conducted interviews with recipients in 28 communities in opposition-controlled areas (where we could gain access). Of the 330 recipients we interviewed, 81% reported changes in their circumstances as a result of the assistance. Many reported that food aid had allowed them to use money saved to meet other basic needs, such as housing, health services or other non-food items, and 13 families said they were able to send children back to school. From livelihoods programmes, 53 people claimed that the support had influenced their decision not to leave as refugees, while three reported that it had prevented men from joining armed groups. A clear impact was reported on people’s state of mind as well, with some feeling more optimistic and less stressed. “They make me feel like I am human,” one person told us.

Figure 8: Locations of our interviews in Syria

Two thirds of the respondents also attested that UK assistance had brought about positive changes at the community level. 60% thought that their communities had become safer places to live largely because they believed assistance reduced robberies, but also because it created a better mental outlook and improved health conditions. Some reported that aid reduced disputes, such as over water. Aid was also seen as a stabilising factor, with 69% of recipients reporting that their communities were more positive places to live and many believing that they had a greater role to play within their communities.

DFID’s work on protection does not yet reflect the scale of need

According to a Red Cross definition, ‘protection’ is a category of support in conflict areas that aims to “make individuals more secure and to limit the threats they face, by reducing their vulnerability and/or their exposure to risks, particularly those arising from armed hostilities or acts of violence”. It is highly varied and context-specific, including activities such as ensuring the safety of refugees and displaced people, psychosocial support, protection of children, awareness-raising on human rights, and preventing and responding to sexual and gender-based violence. Protection work is often integrated into wider humanitarian activities – for example by ensuring that camps for displaced people are well lit and shelters located a reasonable distance from food aid collection points.

Effective protection activities are very difficult in the context of a live conflict where civilians are deliberately targeted. Protection also requires a stable presence within the relevant communities, which is lacking. As one DFID staff member observed: “You can’t take protection off a truck.”

DFID characterises the Syrian context as a ‘protection crisis’. In its five-year strategy for Syria, protection is one of four objectives, encompassing both life-saving humanitarian assistance and specific protection activities, which are regarded as “inextricably linked”.22 Annual funding for specific protection activities in Syria, such as child-friendly spaces, women’s centres, legal assistance and protection monitoring, has increased from £3 million in 2013-14 to £16 million in 2016-17. A humanitarian adviser on the Syria team is responsible for mainstreaming protection across both programming andadvocacy efforts.

When submitting proposals under the 2016-20 business cases, DFID partners were invited to explain how they will integrate protection into their programme design, including:

- Explain how the programme will integrate core protection standards and principles.

- State whether the programme will contribute to reducing the extent of external risk more broadly.

- Describe how the programme will contribute to monitoring, reporting and analysis of protection trends.

Within the current portfolio, we found examples of monitoring of protection issues and research on specific topics, such as the targeting of medical personnel by combatants. Specific protection activities include women’s centres, legal aid services, child-friendly spaces and psychosocial support. DFID is a major donor to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in Syria, which is a leading agency on protection, particularly on sexual and gender-based violence issues, and offers training to other agencies.

Among the INGO delivery partners in our sample, progress on developing protection activities is mixed. One partner has had a multi-faceted programme since the early stage of the conflict, including in intervention to help people displaced by conflict to access civil documents. Others are newer to protection programming and are yet to fully develop their activities, although protection elements may be built into their humanitarian work. They offered several explanations for the slow start, including challenges with recruiting appropriately qualified staff and the difficulty of working from fixed sites, like community or women’s centres, given rapidly changing local security conditions. These variations are anticipated in DFID’s 2016 Syria strategy, which notes that some partners will have “specialised protection programming capabilities” while others will focus primarily on the delivery of relief. However, it notes that “[a]ll should be committed to integrating core protection principles and relevant interagency guidelines into their work as part of good quality programming which has at its core the dignity, agency and safety of the affected population”.

While we acknowledge DFID’s increased efforts on protection, we find that it has been relatively slow to implement a strong protection focus into its operations, given the scale of need. As conditions in Syria allow, we would hope to see DFID looking for opportunities to expand its protection efforts – both programming and advocacy.

DFID has been slow to move from emergency assistance to livelihoods support and more flexible modalities such as cash

Conditions across Syria are highly varied. In relatively stable areas, where agriculture and food markets are operating at a certain level, food distribution may not be the most appropriate way of helping those in humanitarian need. There is evidence from other crises that providing support in the form of cash or vouchers can help to stimulate local food markets and rebuild productive capacity. It is also inherently more flexible, enabling recipients to spend according to their own priorities. There may also be scope to move from relief to helping recipients re-establish their livelihoods – for example, by providing agricultural inputs or seed money for small businesses.

In the 2016 Grand Bargain, 30 donors and aid providers committed to increasing their use of cash-based programming. Globally, DFID has been a leading advocate for the use of cash for humanitarian relief. It convened a high-level panel on humanitarian cash transfers in 2015 and chairs a multi-donor working group on the topic.

DFID’s use of cash in Syria has been gradually increasing, accounting for 14% of its humanitarian support through INGOs up to September 2017. DFID’s goal is for 20% of its total humanitarian expenditure in Syria to be cash-based by 2019. It has made some early efforts to promote a coordinated approach to cash across agencies, supporting a working group on the subject in Gaziantep. However, practical and legal constraints, related to counter-terrorism regulations and international sanctions against Syrian banks, have limited partners’ ability to use Syrian financial institutions to transfer cash into Syria and to recipient households. While there are traditional mechanisms for handling cash payments into and within Syria (such as hawalas, which are networks of money agents who exchange value without the need for a formal transfer), they are unregulated and some are reported to pay taxes to terrorist-linked groups and are therefore considered too risky for regular cash transfers.

While the practical challenges with cash transfers are significant, we take the view that DFID should have done more and sooner to build up safe mechanisms for cash programming once it became clear that the crisis would be protracted. DFID is now collecting data on whether conditions are in place for cash programming, including the state of local food markets and possible mechanisms for handling cash payments safely. Humanitarian advisers in Istanbul are working to strengthen partner capacities and coordination mechanisms, and partner logframes now include targets on scaling up the use of cash and vouchers.

Our interviews with people in Syria suggested a clear demand for more livelihoods support. Aid recipients – even those participating in food distribution programmes – indicated a desire for assistance with agriculture or other income-earning activities. Some noted the significance of livelihood programmes in maintaining local markets and strengthening community self-reliance. Interviews with local councils and downstream partner staff also reflected this demand. Of the 36 local council members we spoke to, ten requested more livelihoods programming. One respondent echoed others’ opinion when he said that “finding alternative and sustainable solutions for people” should be a priority for the humanitarian response.

DFID’s livelihoods programming remains small in scale, at 6% of the Syria humanitarian expenditure between 2012 and 2018. Among our seven delivery partner case studies, only one, an INGO, had made significant progress with livelihoods programming. The multilateral partners we reviewed had struggled to establish a successful track record in the area and, in one case, had chosen to deprioritise it. In interviews, both DFID and its delivery partners recognised that the transition to livelihoods programming had been slow, attributing it to a lack of capacity within partner organisations and the difficulty of recruiting experienced staff. We also note that the DFID Syria team lacked advisers specialised in livelihoods programming during the first three years of the response (see paragraph 4.44).

Conclusion on effectiveness

DFID’s humanitarian response in Syria has improved significantly over time and is now delivering effectively over a much larger share of the territory. Its early operations delivered vital food and nonfood items to civilians in need under challenging conditions, but were limited by a shortage of delivery options and constraints imposed by the complex operating context. DFID worked to overcome these barriers. It built up independent sources of information on needs across the country and developed alternative delivery mechanisms operating from neighbouring countries. Working with the FCO and like-minded donors, it helped to secure Security Council authorisation for UN cross-border operations, enabling the shift to a ‘Whole of Syria’ approach to the international response. It used its influence as a funder of the UN system to direct assistance towards the communities with the most severe needs.

Our data collection in Syria suggests that DFID’s targeting of intended recipients was effective at reaching communities in need and, within them, some of the most vulnerable individuals. We found a range of positive results for both households and communities. While little outcome-level data has been generated to date (as is common in humanitarian emergencies), our findings suggest that DFID has made an important contribution to alleviating the humanitarian crisis, meriting a positive rating.

However, we have several reservations. DFID has been relatively slow to integrate protection activities into its programming, given the scale of need. It has also been slow to move towards livelihoods and cash-based support, which would help to avoid distortion of the local economy and to reduce dependence on aid. While we acknowledge the practical challenges, these are areas where a more concerted effort to shift the balance of programming might have delivered more relevant assistance at an earlier stage.

We award DFID a green-amber score, which recognises the value of the role DFID has played to date while pointing to some areas in need of improvement.

Efficiency: How well has DFID managed its delivery chains?

This section explores how well DFID has managed the delivery of its humanitarian assistance in Syria to achieve the best possible results for the support provided. We explore whether DFID put adequate resources into managing the response, given its scale and complexity. We review the management processes and tools that DFID established, assessing whether they gave the Syria team the information it needed to achieve the best possible results.

DFID was slow to acknowledge the scale and extended nature of the crisis and resource its response appropriately

According to DFID staff from the early phase of the crisis, DFID’s initial response was premised on the assumption, shared across the UK government and other donors, that the Syrian conflict would end quickly and in the opposition’s favour. This led DFID to plan and resource its response in a short-term and iterative manner, scaling up its funding in response to the worsening crisis without putting in place the structures and systems required to manage a crisis of this scale and complexity. The practical challenges of responding to such a dynamic context also hampered longer-term planning.

This meant that DFID continued to use tools and modes of operating designed for emergency response. As mentioned in the previous section, DFID’s initial funding was programmed through umbrella business cases without detailed design. As the crisis deepened, both the number of partners and the scale of funding increased on multiple occasions. DFID’s annual spending on Syria went from £2 million via three partners in 2012 to £134 million through 23 partners just two years later (see Figure 5).

The Syria team was originally drawn mainly from DFID’s Conflict, Humanitarian and Security Operations Team (CHASE OT) – a standing team based in the UK that supports emergency response. It was a small team, with only ten staff stationed in the region, distributed among offices in Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and Iraq. London-based team members were required to remotely manage delivery partners operating from multiple hubs. Travel to the region was costly and time-consuming.

DFID faced a shortage of experienced programme managers to support a rapidly growing operation. DFID’s own reviews and our interviews with staff from the period confirm that vacancies remained unfilled for extended periods, forcing DFID to appoint relatively junior staff with no crisis response experience. One DFID staff member described that they were “thrown into the deep end and expected to sink or swim”, leading to a stressful working environment and high turnover of staff.

The advisory team was also staffed mainly by humanitarian advisers, which is usual for emergency response. As the conflict became protracted, however, it called for greater diversity in the response, with programming on livelihoods, health and education. Eventually, DFID expanded the team to include expertise in these areas. However, some stakeholders are of the view that the advisory team profile in the early years of the crisis had held back the evolution of DFID’s response, leaving it caught in an emergency response posture until as late as 2015.

The overall programme management capacity of the Syria team has significantly increased since 2014, matching the shift towards separate business cases for each major delivery partner. There are now 63 staff on the team, with a significant proportion (33%) located in the region, where they have greater access to delivery partners for support and oversight. This is a more appropriate level of resource. While much of the response is still managed remotely, DFID’s increased presence in the region has alleviated some of the challenges it faced earlier in the response.

Figure 9: Evolution of DFID’s staffing numbers and location

DFID improved its capacity for partner selection and management

The expansion of its Syria team from 2014 onwards gave DFID the resources to invest in management tools and processes that were better suited for an operation of this scale and complexity. We saw signs of improvement in delivery partner engagement. DFID established partner management teams made up of:

- a senior responsible owner – typically a senior manager or adviser

- a programme manager, to handle daily programme management

- a technical adviser, who ensures that the sectoral strategy and individual programme activities are appropriate for the context and aligned with best practice.

Interviews with DFID and delivery partner staff confirmed that this tripartite structure, together with DFID’s expanded presence in the region, had improved the level and quality of engagement with delivery partners, with better communication and faster decision-making. As well as formal quarterly meetings with partners, following submission of their quarterly reports, informal interactions are also more frequent. DFID staff informed us that they aim to build a relationship in which partners feel able to raise problems as they arise. In some instances, we saw evidence that this had resulted in improved delivery through earlier identification and solving of problems.

We also saw evidence of improvements in partner selection. In preparation for the shift to multi-year funding in 2016, DFID developed new guidance on proposal assessment. Proposals are evaluated against several criteria, including theory of change, value for money, financial management, risk management, due diligence, and monitoring and evaluation. Using these criteria, DFID has rejected proposals that are a poor fit with its objectives, improving the focus of the portfolio. However, we noted some instances where past performance issues or poor relationships with delivery partners were flagged in the screening processes but not addressed in the design or management of the subsequent programme. This suggests some continuing weaknesses in programme management.

DFID has strengthened the monitoring of its portfolio

In the early phase, DFID’s ability to oversee its portfolio was limited by an inadequate set of tools for tracking funding and results. It worked from basic Excel spreadsheets, which grew in complexity and decreased in utility as the portfolio expanded. DFID staff from the time acknowledged that they were “clunky and presented a picture that was, at best, three months behind”. As the umbrella business cases came to cover multiple partners and countries, it became enormously challenging for DFID to track both individual programmes and overall results using these spreadsheets.

To address this, DFID Syria established a Risk and Results Team to support monitoring and analysis. Among other things, the team is responsible for tracking results across the portfolio, to assess whether they accord with DFID’s objectives. To assist with this, it developed a set of standard reporting templates and a web-based reporting system, Cascade, which became fully operational in April 2017.

We find that the new reporting templates and process are a clear improvement on the previous system. Except for a few multilateral organisations, delivery partners submit their quarterly and annual reports through an online portal using the same template. This enables more timely and uniform reporting on expenditure, results (disaggregated by gender, age and recipient group) and unit costs. This system automates the aggregation of reports, which saves a great deal of staff time and gives DFID improved oversight of both individual partners and the portfolio as a whole. The Risk and Results Team produces a quarterly dashboard on results and can map activities against needs. This analysis helped one DFID adviser to identify an instance where the aid distributed by a multilateral partner did not match up with the areas of most severe need, which were DFID’s priorities. DFID was able to use this information to persuade the partner to redirect their operations.

There are still gaps in the data system. A limited number of multilateral partners use their own reporting templates rather than DFID’s. Additionally, there is as yet little outcome data. Overall, however, this is a significant improvement in the management of the response, which we would expect to lead to more efficiency gains over time as DFID develops a stronger evidence base for its funding decisions. However, we are concerned that it took two years for DFID to develop a basic reporting template and guidance for its partners. It was a further two years before it put in place a comprehensive suite of uniform reporting tools and systems, and the system had to be developed from scratch. Cascade and other tools from the Syrian response may be adaptable to other humanitarian responses, to enable quicker progress on portfolio management.

DFID has tightened its processes for managing the risks of fraud and aid diversion

Syria is a very high-risk environment for fraud, corruption and diversion of aid. In May 2016, USAID announced that it was conducting a fraud investigation into its cross-border operations from Turkey. Three of DFID’s delivery partners were implicated in the investigation. Around the same time, a DFID internal audit report and an ICAI report on DFID’s fiduciary risk management in conflict zones (for which Syria was a case study) both identified weaknesses in DFID Syria’s risk management practices. ICAI’s report found that DFID’s Syria team lacked programme management experience and was consistently underrating the level of fiduciary risk in its programmes, compared to other conflict zones. We also found that its due diligence reports were being prepared by relatively junior staff (deputy programme managers), resulting in inconsistent quality.

In an updated fiduciary risk management strategy from June 2016, DFID identified a range of measures to strengthen its processes and address the weaknesses that had been identified. It introduced an enhanced due diligence framework, with more rigorous testing of partners’ administrative, financial and operational processes. It appointed an accounting firm to carry out due diligence assessments of INGO partners before the awarding of multi-annual funding agreements. Where the due diligence identified gaps in partner systems that were not severe enough to exclude the partner altogether, DFID developed a joint work plan with the partner to address them, with clear milestones and targets. The delivery partners that we interviewed told us that the process was a rigorous one. One mentioned that it had helped to drive improvements not just in its Syria operations, but across its global systems.

DFID Syria also strengthened its due diligence process for its multilateral partners in September 2016, in alignment with DFID’s central policies. Its approach consists of an assessment conducted by the due diligence adviser and the relevant programme manager before DFID awards any new funding. The enhanced assessment includes a desk review of previous due diligence assessments, including those from other organisations. They also conduct a minimum one-day visit to each country hub and conduct interviews remotely if necessary. The due diligence report is shared with each agency and incorporated into the agency’s business plan and programme delivery plan.

In our 2016 report on fiduciary risk management, we noted the risk that DFID’s ‘zero tolerance’ policy on fraud and corruption might discourage partners from reporting issues in a timely way. DFID has made an effort to address this by creating positive incentives for early reporting. In our interviews with both DFID staff and delivery partners, it was frequently mentioned that DFID encourages partners to report incidents as soon as they occur. Interviewees reflected that, given the high level of risk in Syria, the expectation is not that fraud and corruption cases never occur, but that partners recognise problems early and come up with a solution.

Our 2016 report also identified that fiduciary risks are often most acute lower down the delivery chain, where DFID is not directly involved. DFID requires its partners to carry out due diligence assessments of their downstream partners. The partners reported receiving clear directions from DFID staff on what information they needed to collect and how to conduct the assessment. Downstream partners confirmed to us that DFID’s INGO partners were providing them with support and mentoring on budgeting, unit cost analysis and financial reporting. DFID also funds two of its partners to build the capacity of the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, one of the main downstream partners in government controlled areas. However, we have no evidence that multilateral partners conduct similar capacity development with their other downstream partners.

Since July 2017, DFID has also instituted delivery chain mapping, to improve its oversight of the delivery chain. Delivery partners are required to provide updated information on their downstream partners every quarter. In practice, we found that the information provided was frequently outdated or inaccurate. DFID reports that the information has revealed instances where several delivery partners rely heavily on the same downstream partner, which increases delivery risk. However, it is not yet clear how DFID will use this data to improve risk management.

Overall, we find a range of improvements in DFID’s fiduciary risk management, centred on the enhanced due diligence process introduced in 2016. While the Syrian context will continue to be high-risk, these measures have increased the likelihood that instances of fraud and corruption will be detected and acted upon.

DFID has only recently begun to respond to safeguarding challenges in Syria

‘Safeguarding’ – or the protection of aid recipients from exploitation – has become a matter of heightened public concern following revelations in February 2018 of sexual misconduct by Oxfam staff in Haiti during the response to the 2010 earthquake.