Tackling fraud in UK aid

Executive summary

Fraud is a deliberate and illegal act which results in funds or assets being diverted from their intended purpose. It involves making a false representation, failing to disclose relevant information or the abuse of position to make financial gain or misappropriate assets. The Cabinet Office estimates that for every £100 of UK public spending, between 50p and £5 is lost to fraud and error. However, most government departments report less than 5p in every £100 as detected fraud. This includes the former Department for International Development (DFID) which, until its merger with the former Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) in September 2020, spent around three-quarters of UK aid. Most detected fraud is recovered by departments; less than 1p in every £100 is reported as lost to fraud after recovery. Other major aid donors report similar low levels of fraud.

This rapid review assesses the extent to which the UK government takes a robust approach to tackling fraud in its aid expenditure, known as official development assistance (ODA). The review explores how departments prevent, detect, investigate, sanction and report on fraud in their aid delivery chains, and how they decide on how to balance and manage fraud risk within portfolios, programmes and projects. We look at cross-government counter-fraud structures and assess in more detail the five departments allocated more than £100 million of ODA in 2019-20. These are the former DFID (including the UK’s Development Finance Institution (CDC)); the former FCO; Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS); the Home Office; and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC).

The review addresses external fraud involving individuals or organisations outside UK government departments, or involving both internal and external parties (such as fraud relating to outsourcing), and not internal fraud by UK government employees. Our aim was to assess the effectiveness of fraud risk management across ODA-spending government departments. We did not seek to identify or investigate specific instances of fraud or to test fraud risk management beyond ODA. In addition, we excluded central funding to multilateral organisations, as this is subject to specific accountability mechanisms not covered by this review. The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) is planning a supplementary review looking at fraud prevention measures within multilateral contributions.

As the review is retrospective, we treated the FCO and DFID as separate departments while considering the implications of our findings for their merger to create the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

Relevance: To what extent do departments have systems, processes, governance structures, resources and incentives in place to manage risks to their UK aid expenditure from fraud?

We conclude in our review that systems, processes and structures are relevant to tackle fraud in the five ODA-spending departments we reviewed notwithstanding several observations made below.

A cross-government Counter Fraud Function and Centre of Expertise hosted by the Cabinet Office provides a resource and structure to those working in counter-fraud roles across government departments. The Centre of Expertise oversees the professional development of counter-fraud specialists and works with them to help public bodies identify and combat fraud. It maintains a Counter Fraud Functional Standard, which sets out requirements and guidelines for all public bodies. It also tracks the alignment of government departments against the 12 key elements of the Counter Fraud Functional Standard although it does not have the power to enforce the functional standards.

We identified three areas of weakness in the systems, processes and structures that departments use to manage fraud risks. First, there are varying degrees of maturity among ODA-spending departments and no overarching oversight, control or visibility of ODA fraud risks across all government departments. Second, whistleblowing mechanisms for external parties are diverse and not consistently accessible, and in conflict with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee’s (OECD DAC) recommendation to ensure clear and streamlined whistleblowing mechanisms. Third, there is limited oversight by counter-fraud specialists of procurement and contract management, where some of the greatest fraud risks lie.

Effectiveness: How effectively do departments prevent, detect and investigate fraud at portfolio, individual programme delivery and partner levels?

Fraud risks down the delivery chain are well-considered at the country and portfolio level, and staff and delivery partners understand the need to report suspected fraud. In our sample of programme reviews and interviews, we noted that measures to prevent fraud throughout the programme cycle, and to investigate suspected fraud when detected, are generally being implemented in practice. There were several isolated cases where counter-fraud measures had not worked as designed, but were identified by good programme management practices, fraud investigations and internal audits. Key mechanisms are also in place to deter and detect fraud, such as programme monitoring, reporting requirements, field visits and audits, along with training and guidance for staff.

The main weaknesses we observed in the effectiveness of counter-fraud measures relate to the issues noted above in the systems, processes and structures, especially in relation to the detection of fraud. There are a range of hurdles for stakeholders in highlighting or reporting fraud, including the fear of being identified or disadvantaged thereby limiting the effectiveness of fraud detection. This is likely to contribute to the low levels of detected fraud cases. These issues, combined with weaknesses identified in whistleblowing and procurement oversight and data analysis, may negatively affect the amount of fraud actually discovered in UK aid.

Learning: How effectively do departments capture and apply learning in the development of their systems and processes for fraud risk management in their aid programmes?

Counter-fraud specialists in the five departments we reviewed demonstrated a commitment to learn and improve fraud risk management. There was a good spirit of cross-departmental learning on ODA fraud risk management between four of the five departments. As there is no cross-government ODA specialism within the Counter Fraud Function, however, learning risks being ad hoc to the detriment of departments or teams that are less connected. There is, nevertheless, an appetite among departmental counter-fraud functions for a more coordinated approach to fraud risk management across ODA-spending departments.

Building the capability of partners to manage fraud risks can also benefit aid delivery. The most common areas cited by delivery partners as ways to improve fraud risk management relate to building their capacity through sharing practical examples and increasing investment in systems. Despite the creation of good learning materials, especially by the former DFID, these are not systematically shared down the delivery chain to the extent they could be.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

Consideration should be given to establishing a centralised ODA counter-fraud function to ensure good practice and consistency of the ODA counter-fraud response and share intelligence across all ODA spend.

Recommendation 2

ODA-spending departments should review and streamline external whistleblowing and complaints reporting systems and procedures, and provide more training to delivery partners down the delivery chain on how to report safely.

Recommendation 3

Counter-fraud specialists should increase independent oversight of ODA outsourcing, including systematically reviewing failed or altered procurements, and advising on changes to strengthen the actual and perceived integrity of ODA procurement.

Recommendation 4

To aid understanding and learning, ODA counter-fraud specialists should invest in collecting and analysing more data, including on who bears the cost of fraud, and trends in whistleblowing and procurement.

Introduction

Fraud is a deliberate and illegal act which results in funds or assets being diverted from their intended purpose. The 2006 Fraud Act describes fraud as making a false representation, failing to disclose relevant information or the abuse of position to make financial gain or misappropriate assets. Examples of fraud that may occur in aid spending are in Box 1.

Box 1: Types of fraud

- Abuse of power or influence

- Deception to steal money or resources

- Abuse of procurement

- Overstating contract or grant costs

- Overstating contract or grant achievements

- Facilitation payments or bribes to help achieve programme objectives

- Extortion

- Theft or misuse of data

The UK Cabinet Office states that “Fraud is a hidden crime and to fight fraud you have to find it”. It asserts that the UK aims “to be the most transparent government globally in how we deal with public sector fraud”. It estimates that for every £100 of UK public spending outside the tax and welfare system, between 50p and £5 is lost to fraud and error. However, the largest aid-spending departments report less than 5p in every £100 as detected fraud, as with most government spending. Most of this is recovered; less than 1p in every £100 is reported as lost to fraud after recovery.

This rapid review assesses the extent to which the UK government takes a robust approach to tackling fraud in its aid expenditure – which for the four years to the end of March 2020 totalled £54 billion.7 It explores how departments prevent, detect, investigate, sanction and report on fraud in their aid delivery chains, and how they decide on how to balance and manage fraud risk within portfolios, programmes and projects. The review considers the evolution of aid-spending departments’ approaches to tackling fraud from 2016 to 2017, since when UK aid was increasingly spent across multiple government departments (see Box 3 in chapter 3).

| Review criteria | Question |

|---|---|

| 1. Relevance | To what extent do departments have systems, processes, governance structures, resources and incentives in place to manage risks to their UK aid expenditure from fraud? |

| 2. Effectiveness | How effectively do departments prevent, detect and investigate fraud at portfolio, individual programme delivery and partner levels? |

| 3. Learning | How effectively do departments capture and apply learning in the development of their systems and processes for fraud risk management in their aid programmes? |

Methodology

Research for this review took place from September to November 2020. In September 2020, the Department for International Development (DFID) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) merged to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). At the time of our review, former DFID and FCO programme management and counter-fraud systems and functions were still being operated in parallel. Our review also looked at historic DFID and FCO programmes and fraud reporting. We therefore treated FCO and DFID as separate departments while considering the implications of our findings for the newly formed FCDO.

This review focuses on the five departments allocated more than £100 million of official development assistance (ODA) in 2019-20: DFID (including the UK’s Development Finance Institution (CDC)); FCO; Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS); the Home Office; and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). The review addresses external fraud involving individuals or organisations outside UK government departments, or both internal and external parties (such as fraud relating to outsourcing), rather than internal fraud by UK government employees.

Our methodology combined the following components:

- Annotated bibliography: Review of selected literature on fraud in the UK public sector and international development, and good practice in fraud risk management.

- Systems review: Document reviews and interviews with counter-fraud leads in the five selected departments and with stakeholders in the Cabinet Office and the Serious Fraud Office (SFO).

- Programme review: Review of 18 programmes and two CDC investments across the selected departments, and interviews with two country offices to assess fraud risk management. Our sample included 12 programmes/investments with reported suspected fraud. Nine investigations were complete; three were still under investigation. We could not fully review one of the active cases as the department considered it to be at a sensitive stage in the investigation. In total, we interviewed 49 government officials and 11 external stakeholders for the systems and programme reviews.

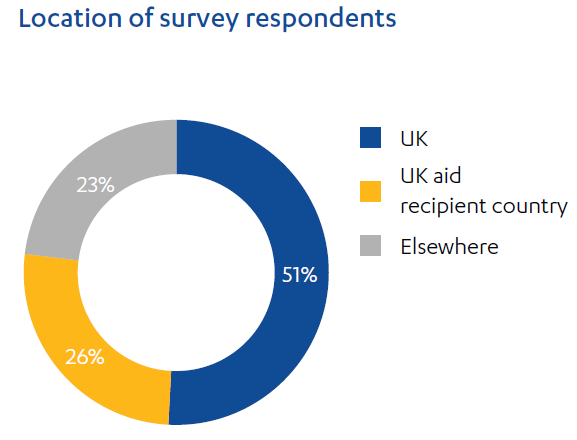

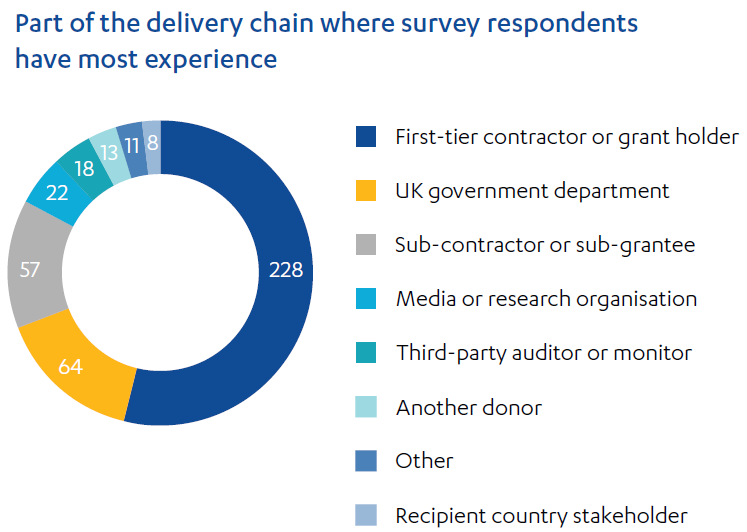

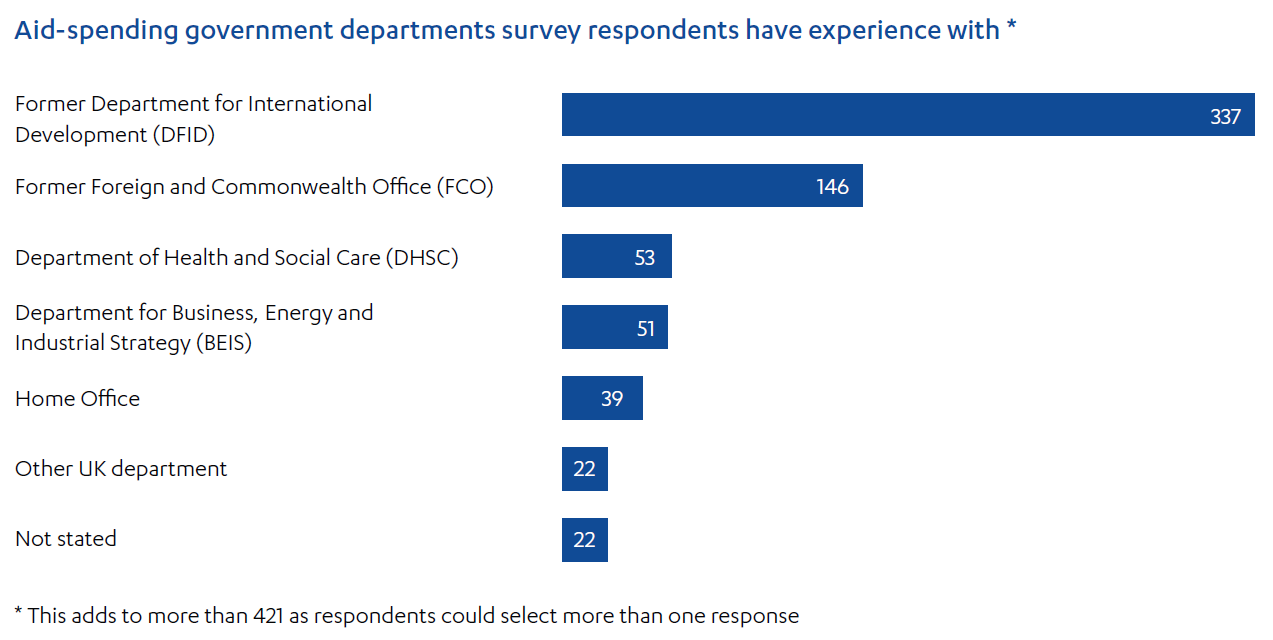

- Stakeholder consultation: An anonymous online survey was used to seek perspectives on fraud risk management in UK aid from stakeholders throughout the delivery chain and provided an opportunity for stakeholders to independently raise any concerns with us. We disseminated the survey to service providers of the selected departments and through ICAI’s networks and communications channels. We received 421 responses; an overview of survey respondents is in Figure 1. We received an anonymous report of one new incident of suspected in-country procurement fraud and referred it to the relevant department. Based on its review of documentation, the department determined there was insufficient evidence of fraud to warrant further investigation.

This review builds on previous work conducted by ICAI, including reviews of DFID’s anti-corruption programming, fiduciary risk management and procurement and contract management practices. It also draws on National Audit Office (NAO) work, including its 2017 review of DFID’s approach to tackling fraud. Both ICAI and NAO have previously highlighted the relatively low level of fraud detected in UK aid compared to estimated levels. For example, NAO found that “there are few allegations of fraud reported to DFID in some of the countries ranking among the most corrupt”. NAO also noted that DFID had improved its counter-fraud strategy in response to previous ICAI scrutiny, including strengthening guidance, working to increase awareness of fraud among delivery partners and staff, and embedding consideration of fraud risks at different stages in the programme delivery cycle. This review is not, however, intended as a formal follow-up of prior ICAI or NAO review findings.

Box 2: Limitations to the methodology

- This review did not seek to investigate specific instances of fraud but to assess the effectiveness of fraud risk management across ODA-spending government departments. Where departments raised suspected fraud with us, we reported it via the appropriate channel.

- While some of our findings may be more widely applicable, ICAI is only mandated to evaluate the effectiveness of UK ODA so we designed the review for this purpose only.

- We took a broad view of fraud but did not specifically look at anti-terrorist financing or anti-money laundering measures.

- We excluded central funding to multilateral organisations, as this is subject to specific accountability mechanisms not covered by this review. ICAI intends to carry out a supplementary review looking at fraud prevention measures within multilateral contributions.

- We provided survey anonymity to create a safe space for stakeholders to provide honest views, but this means we cannot verify responses. Aggregated responses helped inform our subsequent interviews and document reviews, and were triangulated with the other methodology components.

- During the review, COVID-19 travel restrictions were in place and departments were responding to this emergency. Departments made significant efforts to accommodate our work, but the amount of engagement available to us within the timeframe of a rapid review was limited. All work was conducted remotely.

Overview of survey respondents

A total of 421 stakeholders responded to our anonymous survey comprised as shown in Figure 1. All questions were mandatory apart from an opportunity to provide written comments on how fraud risk management could be improved in UK aid. Almost half of respondents also provided written comments.

Half of respondents were UK-based and a quarter were based in UK aid recipient countries. In terms of experience, the largest cohort (54%) came from first-tier partners (contractors or grant holders), followed by UK government departments (15%) and sub-partners (14%). While 80% had experience of DFID-funded programmes, half of these had experience with at least one other department and DFID.

Figure 1: Composition of survey respondents

Background

Fraud risk exists in every sector and type of expenditure, but risk profiles vary. In 2017, the UK Fraud Costs Measurement Committee estimated that payroll fraud was under 2% of expenditure while procurement fraud was close to 5% in both the UK public and private sectors. Similarly, Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) estimates losses in the tax and welfare system to be around 5%. Some expenditure may be higher risk. For example, in its report to the Public Accounts Committee in November 2020, HMRC stated that it assumed the error and fraud rate in its Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme to be between 5% and 10%.

Similarly, the fraud risk profile of UK aid expenditure depends on factors such as the delivery mechanism, the nature and experience of partners, and the country context; the risks of which can change over time. Although risk profiles for UK aid vary, there are key characteristics of UK aid that warrant treating it as a specific class of government expenditure for fraud risk management purposes (see Box 3), as it is for other forms of scrutiny and reporting. During our interviews, a senior official at the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) identified three major fraud risk areas for government as being outsourcing in defence, the health service and UK aid.

Box 3: Official development assistance (ODA) and fraud risk

UK aid is a specific class of government expenditure, known as ODA, intended to tackle poverty and promote development in developing countries. Criteria for what constitutes ODA are set by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC), a group of traditional aid donors, including the UK. The UK government is accountable to Parliament’s International Development Committee for meeting its ODA obligations. ODA is subject to scrutiny by ICAI and other bodies such as Parliament and the National Audit Office (NAO), and treated as a distinct area by the press and public.

There are practical risk factors that, while not universal, are commonly associated with ODA spending. In particular, UK aid is primarily outsourced to external agencies and companies, often through complex delivery chains, and focuses on achieving development results in often challenging and high-risk contexts. The ongoing, high-profile public and political discourse about how much UK taxpayers’ money is spent on aid, how it is delivered and what it is spent on, makes how fraud risks and breaches are managed and reported a sensitive issue.

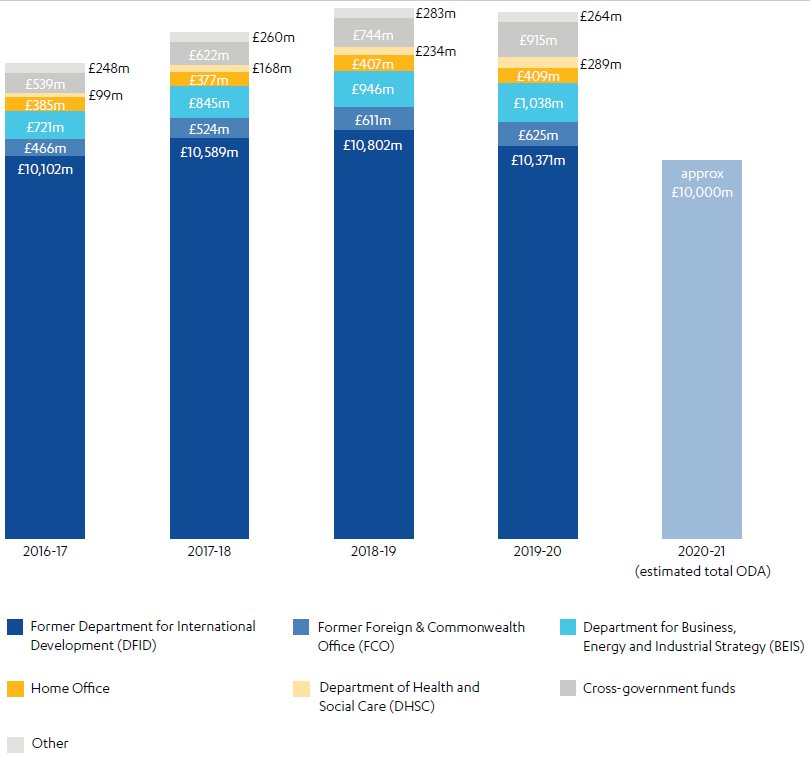

Figure 2 shows the ODA budgets for each of the five departments looked at in this review, and the two largest cross-departmental funds, from 2016-17 to 2019-20. The estimated spend for 2020-21 is also shown. During 2020-21, the DFID and FCO merged to form the FCDO and the UK’s ODA budget was reduced.

Figure 2: ODA allocation by department and cross-government funds by year

Sources: Policy paper. Annex: Official Development Assistance (ODA) allocation by department, DFID, 31 January 2020; the 2020-21 estimate is based on Development update, Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs, UK Parliament, 26 January 2021, accessed 22 March 2021.

Who commits fraud?

Three key factors can affect the likelihood of fraud being committed. These are: opportunity (such as weak controls or too much trust); motivation (such as to service debts or pressure to meet targets); and rationalisation (such as feeling undervalued or thinking ‘everyone else is doing it’). These factors can change over time. Counter-fraud strategies aim to tackle them through controls, culture and training.

A 2020 study found that 28% of organisations across a range of sectors are significantly affected by fraud committed by external parties and 27% by fraud perpetrated within their organisation. It also found that 45% of fraud within the organisation is perpetrated by employees, 17% by third parties and 12% by customers. Fraud committed by external parties is most commonly perpetrated by customers (20%), followed by contractors (18%) and third parties (18%). This indicates the types of risks that organisations may face in the aid delivery chain.

Lines of defence against fraud

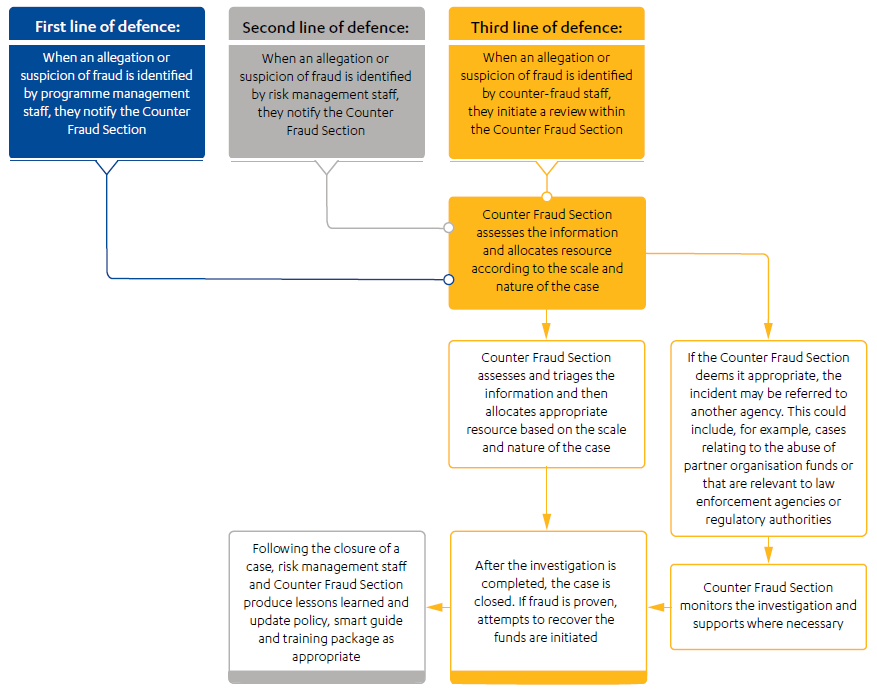

Good counter-fraud practice comprises three lines of defence, which are also expected of all government departments and arm’s length bodies. The first line of defence comprises staff and management systems and controls to ensure fraud risks are identified, addressed and monitored in programmes. This is typically delivered by front-line staff such as programme managers and senior responsible officers, who are accountable for ensuring the programme delivers on its objectives, outcomes and required benefits. The second line comprises risk management staff and assurance policies and procedures, designed to support front-line staff in taking an appropriate level of risk and ensuring management systems and controls are working. The third line involves proactive and reactive investigation of suspected fraud and ensures learning from failures. This is typically managed by counter-fraud specialists.

Figure 3 shows the design of DFID’s fraud reporting process. Any line of defence could identify allegations or suspicions, which it should then report to the third line to assess. The Counter Fraud Section (the third line of defence) determined whether to investigate the incident, provide support to the relevant line to address the concerns or refer the case externally, such as if the fraud does not relate to UK aid funds. Once the investigation is complete – whether fraud is proven to have happened, not to have happened or the evidence is inconclusive – the case is closed and the Counter Fraud Section shares any learning with risk management staff to consider changes in policies, guidance or training.

Figure 3: DFID’s fraud reporting process

Source: DFID Counter Fraud Policy, Oct 2017, DFID, unpublished.

Changes in how aid is spent through government departments

Prior to the creation of the FCDO, while the majority of UK aid was spent through DFID, increasing amounts were spent through other government departments and cross-government funds (see Box 3). In 2019-20, DFID was allocated just under 75% of ODA, compared to 80% in 2016-17. By 2019-20, five government departments were each allocated more than £100 million of ODA. This means departments with less experience of UK aid were spending increasing amounts of aid and ODA was a relatively small part of their overall mandate.

During our review, shortly after the FCDO was formed, Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab announced that going forward, “all aid projects will be assessed through a new management process, led by FCDO” and that “FCDO will decide the final allocation of ODA to other departments”. This suggests that while other departments may continue to play a role in delivering ODA, there may be greater central oversight of the ODA portfolio by FCDO. Although this was not in place at the time of our research, we have aimed to interpret our findings and recommendations with these considerations in mind.

The Foreign Secretary also stated FCDO’s intention to reduce the need to outsource aid delivery, reducing “reliance on mega-contracts with delivery agents”. This had yet to be implemented at the time of our review but, given the significant use of contractors in UK aid delivery and the inherent fraud risk associated with procurement, it is pertinent to our findings.

Establishment of a cross-government Counter Fraud Function and standards

In October 2018, the UK government established a cross-department Counter Fraud Function, bringing together 15,000 counter-fraud public servants and creating a Counter Fraud Functional Standard (Government Functional Standard GovS 013: Counter Fraud). One of 14 government functional standards, it applies to all government departments and arms-length bodies. It includes both mandatory and advisory elements and aims to set expectations for the management of fraud, bribery and corruption risk by government organisations.

The Counter Fraud Functional Standard comprises 12 elements covering key aspects of governance (such as counter-fraud action plans, metrics and assurance) and practices (including reporting, proactive detection activity and training). Regarding metrics, for example, the standard states that organisations should define the outcomes they are seeking to achieve that year and “target an increase in the total amount of detected fraud and/or loss prevented from their counter-fraud strategy”. Regarding proactive detection activity, organisations are expected to “undertake activity to try and detect fraud in high-risk areas where little or nothing is known of fraud, bribery and corruption levels”.

At the same time, a Government Counter Fraud Profession was launched to provide a professional structure and career path, and common standards and competencies, for government fraud professionals. Its aim is to tackle fraud head on by investing in highly skilled people and bringing together individual and organisational learning from across the public sector, and beyond, into one place. The Counter Fraud Centre of Expertise supports the standard and function (see Box 4).

Box 4: UK government Counter Fraud Centre of Expertise

The Counter Fraud Centre of Expertise was established in 2018 within the Cabinet Office. While the centre does not have the power to enforce the Counter Fraud Functional Standard, it aims to improve counter-fraud practices across government departments by:

- bringing the Counter Fraud Function together

- overseeing the development of the Counter Fraud Profession

- supporting public bodies to enhance their fraud response

- maintaining the Counter Fraud Functional Standard

- assessing public bodies’ compliance with the 12 key elements of the functional standard

- leading the International Public Sector Forum, engaging public sector agencies globally to understand, find and stop fraud.

The Centre of Expertise publishes an annual cross-government fraud landscape report, which summarises the progress of departments against the 12 key elements of the Counter Fraud Functional Standard.

Since the implementation of the Counter Fraud Functional Standard, government departments have reported a 21% increase in reported fraud allegations, from 8,361 in 2017-18 to 10,116 in 2018-19. The Counter Fraud Centre of Expertise cites the volume of reported suspected fraud as a key indicator of its ability to reinforce the right culture, where departments acknowledge that fraud exists and staff are confident in identifying and reporting it. Cabinet Office reporting does not specify how many cases relate to ODA, but DFID, which had responsibility for around 75% of ODA spending in 2019-20, had also seen an increase in the number of allegations reported and investigations undertaken over the previous four years. According to NAO, this was likely at least in part due to DFID’s deliberate strategy to “increase awareness of fraud and relevant policies and procedures among staff and delivery partners”, in response to ICAI’s 2011 review of DFID’s approach to anti-corruption. Nevertheless, no clear correlation exists between increased numbers of investigations by either DFID or other departments, and the amount of fraud discovered or prevented, which remains very low (see Annex 1). In addition, the increase in allegations has only taken place for low level fraud, not larger frauds. We note that similar, low levels of detected fraud reporting occur for other major donors such as the US Agency for International Development and United Nations’ bodies.

OECD Development Assistance Committee recommendation on managing risks of corruption

The OECD DAC is a co-ordination mechanism among traditional donors, including the UK. Its 2016 Recommendation of the Council for Development Co-operation Actors on Managing Risks of Corruption considers corruption risks affecting the delivery of ODA specifically. It sets out measures to prevent and detect corruption across ODA-financed projects, and details sanctions to include in ODA contracts to enable agencies to respond to cases of corruption. It also recommends that agencies should work towards a comprehensive system for corruption risk management including codes of ethics, whistleblowing mechanisms, financial control and monitoring tools, sanctions, co-ordination to respond to corruption cases, and communication with domestic constituencies (taxpayers and parliaments) on the management of corruption risks.

The document includes suggestions for implementing its recommendations. Regarding whistleblowing, for example, it recommends that agencies should “communicate clearly about how confidential reports can be made, including providing training if necessary, and streamlining channels to reduce confusion”. It also suggests that agencies should “communicate clearly and frequently about the processes and outcomes of corruption reporting to build trust and reduce any perception of opacity around corruption reports and investigations”.

Findings

Relevance: To what extent do departments have systems, processes, governance structures, resources and incentives in place to manage risks to their UK aid expenditure from fraud?

The Cabinet Office Counter Fraud Function has strengthened counter-fraud capability but acts only in an advisory capacity and does not have an Official Development Assistance (ODA) specialism

The Counter Fraud Function and Centre of Expertise hosted by the Cabinet Office provides a resource and structure to those working in counter-fraud roles across government departments. It also brings together public reporting of detected fraud for all government departments in its annual fraud landscape report.

Cabinet Office personnel work with departments to develop clearly defined targets for fraud detection and prevention. The Cabinet Office identified the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) as a leading department in this area, noting that it has metrics and financial targets in place for savings from fraud prevention across the department. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) had recruited additional fraud resources to try to identify the real level of fraud, particularly on programme spend. The Department for International Development (DFID) had set metrics to “increase reporting of fraud by 2% (on a year-on-year basis) in areas where reporting levels are low and perceived corruption levels and terrorist finance risks are high”.

However, while the Centre of Expertise assesses alignment of government departments with the 12 elements of the Counter Fraud Functional Standard, it does not have a formal responsibility for departmental counter-fraud measures. Each department is responsible for its own fraud risk appetite, systems, frameworks and resources for managing fraud. This results in a lack of uniformity in processes, reporting lines and quality standards, and potentially impacting the operational efficiency and effectiveness of the overall cross-government counter-fraud framework.

ODA is spent across a range of departments yet, as a class of government expenditure, is subject to specific rules and scrutiny, and many of the same fraud risks and delivery partners (see Box 3). The Counter Fraud Centre of Expertise does not have an ODA specialism. Although the Centre of Expertise provides a forum for engagement for counter-fraud specialists in general, ODA-specific learning takes place primarily through informal channels.

To summarise, there is no overarching authority responsible for counter-fraud frameworks across government, and the Cabinet Office does not have the power to enforce the functional standards on non-compliant departments.

The main ODA-spending departments have adequate systems, processes and structures in place to manage ODA fraud risk albeit with differences and weaknesses

All departments have counter-fraud policies and strategies setting out how to respond to fraud and respective strategic areas of focus to better manage and tackle fraud in the future. As stated before, the existence of a central function and standard is relatively recent and cannot mandate changes at the department level. As a result, differences remain between the approaches and structures of each department. BEIS, for example, relies more than the other departments on its arms-length bodies’ counter-fraud resources to monitor and assess fraud risk for ODA spend (these bodies were outside the scope of this review). It has, however, established a group for arms-length bodies and partner organisations to share good counter-fraud practice and intelligence. The FCO had engaged with a wide range of external agencies to inform its work on ‘finding more fraud’. DHSC established an ODA Transparency Working Group to help ensure it meets UK aid strategy transparency requirements. DFID and DHSC had agreed a more routine exchange of audit plans, to help avoid duplication of audit activity and information exchange, as well as promoting the potential option for joint audits. DFID’s internal audit function used fraud risk assessment tools to assess fraud risks and data across the department, follow up on prior findings and identify specific areas to target. DFID’s control and assurance function also looked for areas where low levels of fraud are reported and support front-line staff to help them encourage reporting. Former DFID’s fraud risk assessments are being used to inform the new FCDO strategy.

How each department treats ODA also varies, so it was not possible to directly compare departmental approaches. Table 2 summarises key information provided by departments about the attributes and resources they have in place to tackle fraud.

Table 2: Summary of counter-fraud information provided by departments

| Former DFID | Former FCO | BEIS | Home Office | DHSC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person to whom the third line of defence reports | Director General Finance via Head of Internal Audit | Director General Finance via Deputy Head of Internal Audit | Chief Financial Officer | Director General Capabilities and Resources Office | Finance Director |

| Third line, counter-fraud investigation staff budget | £996,523 in 2020-21 | £154,754 from April to August 2020 (total internal audit costs including investigations) | £200,000 to £250,000 annually (pre-COVID figures; resources have been tripled to deal with COVID-related risks) | Not provided | £226,393 from April to December 2020 |

| Number of third line counter-fraud staff (full-time equivalent), excluding counter-fraud resource in the first and second lines of defence | 18 | 7 (excluding 8 in FCO-sponsored British Council) | 2 (BEIS relies on arm’s length bodies’ counter-fraud resources) | 19 | 9 (excluding the NHS CFA – discussed later in paragraph 4.36) |

| Number of third line counter-fraud staff that are members of the counter-fraud profession | 0 (from third line but 3 in second line positions) | 0 | 1 | 19 | 6 (all of its fraud investigators) |

| Percentage of staff completing counter-fraud training | 71% as at Mar 2020 among all staff | 13% as at March 2019 among all staff | 12% as at March 2020 among all staff | Not provided | 100% as at Jan 2020 among ODA-spending teams |

| Cabinet Office assessment of compliance with the 12 Counter Fraud Functional Standard elements (see Annex 2 for detail) | 11/12 | 11/12 | 11/12 | 9/12 | 12/12 |

| Evidence of close working between ODA and department level counter-fraud resources? | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Number of ODA-related fraud cases reported from 2016-17 to 2019-20 compared to ODA spend | 2,819 1 case for every £14m of ODA | 6 1 case for every £370m of ODA | 7 1 case for every £610 million of ODA | 0 | 2 1 case for every £400m of ODA |

| Fraud losses before and after losses recovered (gross and net losses) from 2016-17 to 2019-20 in GBP and as a percentage of ODA spend to 3 decimal places) | Gross loss: £25.3m (0.060%) Net loss: £2.6m (0.006%) | Gross loss: 0 (0.000%) Net loss: 0 (0.000%) | Gross loss: £371,479 (0.009%) Net loss: £35,623 (0.000%) (may not be complete for 2018-19 & 2019-20) | Not provided | Gross loss: £5,964 (0.000%) Net loss: £0 (0.000%) |

Counter-fraud intervention points are designed into each phase in the programme cycle. Again, there were differences between departments but they broadly follow the approach shown in Table 3. We observed several good practices including the Smart Rules and Smart Guides developed by DFID’s Better Delivery team to support first line roles and now adopted by FCDO. These provide practical guidance on mapping risks in the delivery chain and conducting due diligence on partners, for example.

Table 3: The programme cycle and counter-fraud controls

| Stage in the cycle | Key activities | Examples of key counter-fraud controls |

|---|---|---|

| Design | • Setting out a business case, including the context and evidence to support what it aims to deliver • Making strategic choices about how to deliver business plan commitments • Determining delivery channel and route to market | • Fraud risks included in business plan risk assessments • Delivery chain mapping informs delivery channels • Second-line counter-fraud staff provide support where significant fraud risks have been identified |

| Mobilisation | • Identification of partners and tendering • Conducting due diligence on selected partner • Formalising agreements • Finalising the results and monitoring frameworks | • Tendering process following procurement rules • Contract terms and conditions mandate fraud reporting |

| Delivery | • Establishing delivery plan • Managing risks and relationships • Escalation of issues when they arise • Adjusting and adapting to changing circumstances | • Policies and guidance set out how staff should respond to suspected fraud • Ongoing performance monitoring and review • Financial monitoring and review of supporting documentation • Reporting of any fraud allegations to third line counter-fraud staff |

| Closure | • Evaluating performance • Learning and sharing lessons to adapt future implementation including in any programme redesign, extension and closure | • Policies and guidance set out closure risks and controls, including specific risks and challenges for early programme closure • Review of final programme reporting and financial claims |

Some departments’ approaches to fraud risk management in ODA are less developed than others

We noted several aspects of the Home Office approach to fraud risk management in ODA were not completely developed. Home Office considers its ODA spend to be low risk due to the nature of spending (for example, through established first-tier suppliers) and a lack of reported fraud cases. However, similar risk profiles exist in other departments but we do not have the same concerns. Although not specifically focused on ODA, the Counter Fraud Centre of Expertise’s assessment also indicates Home Office fraud risk management is less developed at a departmental level (see Annex 2). Counter Fraud Function officials informed us that while there are capable people working on fraud in the Home Office, there are still gaps in capability and further work is necessary to comply with the Counter Fraud Functional Standard – which is the minimum that public bodies have committed to in order to manage the risk of fraud. From our own research, while the Home Office ODA team engaged positively with the ICAI review team and demonstrated a desire to strengthen their capabilities and learn from our review, we are concerned that, relative to the other departments, they have limited experience of ODA and appear isolated both from the main counter-fraud resource within the Home Office and other departments’ ODA counter-fraud specialists. We note that sometimes the Home Office had engaged with DFID and FCO on fraud risk, including in the Joint Anti-Corruption Unit as mentioned in ICAI’s 2020 information note on tackling corruption. Based on this review, however, the level of engagement was lower than the other departments reviewed, and we would have liked to have seen more systematic engagement and learning by the Home Office with other ODA-spending departments.

The Home Office was also unable to provide comprehensive responses to our questions and requests for data and information (as outlined in Table 2). While this does not mean the information does not exist in the Home Office, it reinforces our perception that the ODA team may have been isolated and therefore unable to access key information.

BEIS informed us it was significantly increasing its counter-fraud resources to respond to the increased fraud risk due to high levels of rapid spending in response to COVID-19. BEIS officials expressed a hope that at least some of these resources would be retained permanently. While not specifically focused on ODA, we agree that this would be beneficial given the lower levels of third line counter-fraud specialists in BEIS compared to the other departments.

All departments have a ‘zero tolerance to fraud’ but differ in their understanding of what this means in practice

ICAI’s 2016 review of DFID’s approach to managing fiduciary risk in conflict-affected environments raised concerns about confusion among DFID staff about what zero tolerance means in practice. We were satisfied to find a clear and consistent understanding among former DFID counter-fraud and programme staff that zero tolerance to fraud means fraud risks can be taken with proportionate controls in place, but that there is “zero tolerance for inaction to prevent and quickly rectify problems when they come to light”. Former FCO, BEIS and DHSC interviewees shared this understanding.

The Home Office ODA team, however, interpreted zero tolerance as meaning that fraud risks should not be taken. Such an interpretation of zero tolerance to fraud is concerning as it can have the unintended consequence of burying fraud deeper, as individuals and delivery partners down the delivery chain fear the reputational consequences of reporting fraud. It risks slowing progress on Cabinet Office initiatives to find more fraud. Among Home Office programme staff, we found a mixed understanding of a zero tolerance approach. While some officials showed a nuanced understanding of fraud risks, we are concerned by instances where trust in experienced delivery partners not to commit fraud, or confidence in the strength of anti-fraud messaging, was disproportionately high compared to the other departments.

The Home Office approach to fraud reflects its anti-fraud and corruption strategy. This emphasises maintaining “a culture that actively encourages integrity, supported by an environment that inhibits fraud or corruption”. This contrasts with the other departments’ strategies that place greater emphasis on building awareness and encouraging openness, while promoting active counter-fraud mitigation and investigation. For example, the DHSC Fraud Policy notes “we know much fraud goes unreported. The better informed we are, the more we can do to prevent, detect and deter it.” There were also slight differences in each department’s definition of fraud (see Annex 3).

There are multiple whistleblowing and complaints mechanisms that vary in accessibility

Whistleblowing, in the most general use of the term, is the act of reporting wrongdoing to authorities or the public. Certain types of whistleblowers have protections under the UK Public Interest Disclosure Act (PIDA), such as an employee reporting illegal activity by their employer. In the case of the government departments we reviewed, each has its own whistleblowing policies relating to its own employees. These policies, and their protections, do not apply to external delivery partners or individuals who report to a government department, such as employees of a delivery chain partner. Policy documents sometimes refer to whistleblowers as complainants or external whistleblowers. While the legal protection provided by government departments under PIDA does not extend to external whistleblowers, departments do aim, however, to maintain the confidentiality of the person making the report.

Delivery partners, nonetheless, are contractually obliged (whether in contracts or grants) to report suspicions of fraud and must require this of delivery partners down the delivery chain. Mechanisms for reporting and their accessibility vary considerably, commonly being outsourced to the first-tier contractor or a third-party provider. UK Aid Match, a £23 million a year FCDO grant fund matching public donations to aid charities, previously managed by DFID, has an outsourced, online reporting mechanism that states that it is an “anonymous, free-to-call and confidential service”. In contrast, other mechanisms are email-based or require a potentially costly phone call to the UK. This variety of mechanisms may confuse would-be external whistleblowers and, where emails and calls are invited, may increase concerns that reporters might be identified as opposed to anonymous reporting systems. There is also the potential for misunderstanding about the level of protection that government departments provide to external whistleblowers. For example, the UK Aid Match fraud reporting page states that grant holders are mandated to report suspicions of fraud immediately and refers them to its “whistleblowing hotline” which is “available to all of our employees, as well as clients, business partners and others in a business relationship with UK Aid Match”. The site does not distinguish between whistleblowers with PIDA protection or explain how those without it will be protected and how to minimise the risks to themselves.

OECD DAC recommends agencies should “communicate clearly about how confidential reports can be made, including providing training if necessary, and streamlining channels to reduce confusion if different reporting mechanisms exist for different stakeholders.” Although reporting of concerns about fraud is mandated in contracts and grants, UK aid-spending departments, collectively, currently fall short of meeting this recommendation for external stakeholders. With a wide range of reporting channels in existence, many delivery partners are subject to different mechanisms for different programmes. As we discuss later in the report, almost three-quarters of survey respondents believe people are afraid or disincentivised to report fraud. Therefore, it is critical to ensure potential external whistleblowers understand how to report suspected fraud safely. This demonstrates that the government should consider the coherence, accessibility and effectiveness channels that are available, and how it communicates this to stakeholders.

Outsourcing-related ODA fraud risks lack systematic scrutiny by third-line counter-fraud specialists

Third line counter-fraud resources tend to focus on risks down the delivery chain rather than at the top contract level where some of the biggest risks lie. A senior official in the Serious Fraud Office advised us that outsourcing in ODA is among the biggest fraud risks for the UK government. The UK Fraud Costs Measurement Committee estimated procurement fraud makes up 64% of all fraud in the UK by value. The Cabinet Office reports that procurement fraud made up 79% of all reported external fraud in 2017-18 and 50% in 2018-19. Excluding core funding to multilateral agencies (which accounted for a third of the ODA spend in 2019 but is outside the scope of this review), the government delivers ODA primarily by outsourcing through contracts and grants, so it is reasonable to assume that procurement and grants are likely to be the highest risk areas in ODA expenditure by value as well. DFID’s internal audit department also included procurement risks in its 2020 analysis of DFID sector trends.

First- and second-line procurement procedures and practices were outside the scope of this review but we considered how the third line of defence (ie, the counter-fraud specialists responsible for proactive and reactive investigation of suspected fraud) engaged with procurement risks. We saw evidence that, where issues were raised with counter-fraud teams, they were investigated – but we identified an opportunity for more proactive, independent scrutiny. An overly reactive approach may miss trends or areas of risk that are not known to, or raised by, procurement officials. Cabinet Office officials noted that, from reviewing areas with reported fraud, procurement was a gap with little reporting compared to the level of spend. Furthermore, ICAI and the International Development Committee have previously raised concerns about the dominance of a small number of service providers and the overuse of framework contracts in ODA by DFID, increasing the risk of unethical practices. ICAI’s follow-up review of its 2018-19 reports found DFID had increased its pool of bidders and lead contractors following ICAI’s 2017 review of DFID’s procurement. Nevertheless, a small number of first-tier partners still dominate ODA. DFID’s ten largest legacy service providers have contracts valued at £2.06 billion, some of which are multiyear contracts. DFID’s single largest legacy service provider holds £535 million of this.

Third line counter-fraud experts do not routinely review data on failed or challenged procurements to assess whether fraud in its various forms has occurred. They do not systematically review other risk areas where fraud or corruption may occur, such as post-contract variations either. Doing so would help to generate learning to reduce the risk of procurement failure and demonstrate independent scrutiny to service providers. In addition, DFID’s Procurement and Commercial Department (PCD), which had a separate disputes and risk team, dealt with complaints about contract awards. While this team was independent of those making the original contract award, it was not independent of PCD. Separately, tender evaluation boards do not need to include independent technical reviewers (although they could use them), and could comprise of only the commissioning department and a member of PCD. Although DFID’s PCD’s Procurement Steering Board provided an oversight function, the board’s terms of reference did not list counter-fraud officials as observers or attendees. In addition, the reporting lines of DFID’s counter-fraud function and PCD both went through the Director General for Finance, further diminishing independence.

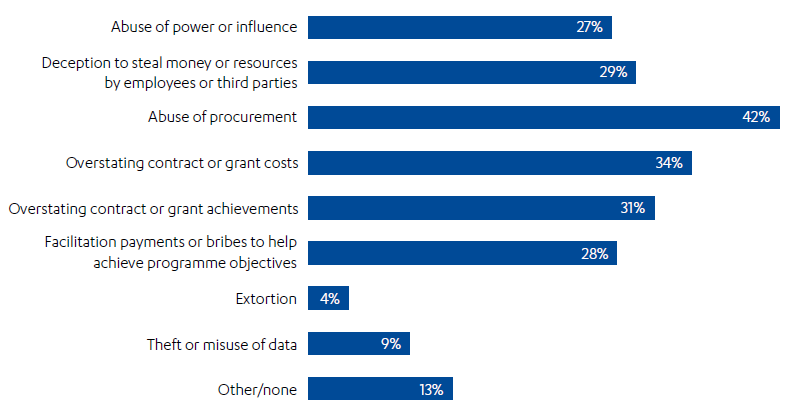

Stakeholders also consider procurement and contract or grant fraud to be the main fraud risks to UK aid. Survey respondents consider the top three most likely types of fraud to occur in UK aid relate to procurement and contract management (see Figure 4). These were:

- Abuse of procurement (42% of respondents).

- Overstating contract/grant costs (34% of respondents).

- Overstating contract/grant achievements (31% of respondents).

Figure 4: Stakeholder perspectives on the types of fraud most likely to occur in UK aid

There is some variation between different stakeholder groups. Respondents from UK government departments are less likely to consider procurement to be in the top three risk areas than first-tier partners or sub-partners (36% compared to 46% and 42%). UK government respondents are more likely to consider overstating achievements to be in the top risk type than first-tier partners (34% compared to 25%). Sub-partners are even more concerned about this at 43%.

While survey results do not specify whether concerns relate to government departments’ own outsourcing, or sub-contracting and sub-granting down the delivery chain, written comments and interviews with service providers indicate that departments’ outsourcing is an area of concern for stakeholders. See Box 5 for examples of the types of concerns raised by different stakeholders. We could not verify these concerns within the scope of this review and note that DFID had implemented training for what they could discuss in meetings with strategic suppliers in response to previous ICAI recommendations. However, the perception that mis-procurement is occurring to the benefit of some service providers, combined with evidence that outsourcing is an area of high risk, warrants a higher level of independent counter-fraud engagement than is currently in place.

Box 5: Sample of paraphrased concerns raised about outsourcing

- A government official told us of a scenario in a culturally sensitive context where their department approached a bidder to suggest including a specific non-government organisation (NGO) in its consortium to help ensure cultural representation. The consortium won the bid.

- A first-tier partner told us it is common for in-country officials to indicate or specify specialists to include in their bids. They commented that this tends to happen with newer officials who may not understand how framework contracts should work.

- A sub-partner informed us that when they raised what they believed to be confidential and sensitive concerns with the department in confidence about the first-tier partner, the sub-partner believed that these were passed on to the first-tier partner.

While we did not see evidence of widespread malpractice, DFID had identified similar isolated incidents relating to poor procurement practices. In a review of local procurement in August 2020, DFID’s internal audit team found examples where three country offices had contracted suppliers requested by partner governments. In two instances, DFID sole-sourced suppliers without competition. In another office, the internal audit found DFID had requested an expert advisory framework supplier specifically recruit a named individual requested by the partner government. The internal report noted that while partner governments may have good reasons for wanting specific suppliers, there is a risk that this results in inadvertently facilitating cronyism or corruption. The report also highlighted learning opportunities, noting, for example, that where there is a lack of consistent, effective oversight to ensure programme and procurement processes are taking place such risks are increased. These findings and learnings reinforce the significance of the procurement fraud risk but they also highlight the important role internal audit plays in identifying and addressing fraud risks. We were satisfied to see such concerns being tackled by internal audit.

Some fraud risk in contracts and contract management could be better managed

ICAI’s 2018 review of DFID’s tendering and contract management found that the department followed EU legislation and UK government procurement guidelines but also noted that DFID did not always choose the most appropriate procurement processes. The ICAI follow-up review of 2018-19 reports rated DFID’s response to its tendering and contract management recommendations as inadequate, concluding that a continued lack of “effective contract management regime and proper training has demonstrable negative effects on programming, as evidenced in our original review”. Furthermore, ICAI’s 2016 review of DFID’s approach to managing fiduciary risk in conflict-affected environments found an over-reliance on junior staff to manage challenging programmes in high-risk contexts. Our interviews for this review highlighted incidents where junior staff with limited financial understanding were relied upon to carry out due diligence, suggesting this problem persists. DFID’s former PCD officials, now within FCDO, acknowledged that there remains a need for greater focus on contract management, including increasing levels of contract management accreditation among programme managers. Former DFID PCD informed us that it was working with the Cabinet Office to strengthen its training for programme managers.

Interviewees and survey respondents also expressed concern that DFID’s efforts to maximise value for money through setting maximum rates for specified roles in framework contracts and robust financial scoring criteria in tenders could create incentives to manipulate or misrepresent costs in proposals. In one framework contract, a UK-based supplier noted that maximum rates for a junior team member would require a salary less than the living wage, which meant it could not compete without making up losses elsewhere. PCD, however, emphasised that award criteria are set specifically for the programme to reflect key cost drivers. In addition, while tying payments to outputs can help hold suppliers accountable, it can also increase the risk of fraud in reporting. This is consistent with our survey findings discussed around Figure 4, where a third of respondents believe that overstating costs in proposals is a key risk area in UK aid, and supported by interviews with a range of stakeholders.

“Gaming rates enables you to score more so everyone [is] doing it. If you don’t play the game, you won’t win.

“[I] suspect that most fraud actually falls into a grey area of ‘open to interpretation’ rather than outright deception and in many ways is incentivised by overengineered procurement rules and reporting which encourages gaming of the system rather than transparency.”

Conclusions on relevance

We consider systems, processes and control frameworks to be relevant in tackling fraud in the five ODA-spending departments we reviewed. However, variability in approach, systems, structures and the level and focus of resources means there is more to do to meet Counter Fraud Functional Standard requirements. In particular, to “undertake activity to try to detect fraud in high-risk areas where little or nothing is known of fraud, bribery and corruption levels.” The limited levers available to the Cabinet Office to ensure alignment with the Counter Fraud Functional Standard, combined with insufficient independence within reporting lines, risk systemic weaknesses not being identified and addressed. In particular, with most ODA delivery outsourced to delivery partners and procurement being a high-risk area, there is a notable lack of proactive and systematic review of procurement and contract management data and practices by third line counter-fraud teams.

Whistleblowing procedures are in place, but vary significantly in terms of their accessibility, mechanisms and the level of protection for the whistleblower. The variety of whistleblowing channels, coupled with the outsourcing of whistleblowing to a wide range of third parties, also risks causing confusion, creates potential conflicts of interest and makes it harder for government counter-fraud teams to analyse data across ODA. This suggests a need to look both at how to ensure fraud risk is managed appropriately across all ODA spending, and how whistleblowing mechanisms to identify it can be streamlined and strengthened.

Effectiveness: How effectively do departments prevent, detect and investigate fraud at portfolio, individual programme delivery and partner levels?

We observed measures to prevent and investigate alleged fraud to be operating as designed but detection levels are low

In our sample of programme reviews and interviews we noted that the three lines of defence were in place. We also noted that measures to prevent fraud throughout the programme cycle, and to investigate it when found, are being implemented, except in isolated cases discussed above. Key mechanisms are also in place to help detect fraud, such as programme monitoring and review, reporting requirements, field visits and audits, along with training and guidance for staff. Survey respondents concur, with 77% of respondents agreeing that the level of fraud risk taken in UK aid programmes is proportionate to the development objectives (excluding 133 who did not know), and 57% that fraud risk measures are reasonably well matched to the risks (excluding 87 who did not know), although 26% think fraud risk measures are too onerous in some areas and not rigorous enough in others.

Despite estimates of fraud in the public sector being 0.5% to 5% of spend, fraud reported by most government departments is less than 0.05%, reducing to less than 0.01% after recovering losses. The level across all ODA is untracked but, as an indicator, in the four years to 5 April 2020, DFID’s annual detected gross fraud losses (before recovery) ranged between 0.02% and 0.07% of expenditure. That the amount of fraud detected is so low, combined with weaknesses identified in whistleblowing and procurement oversight, shows departments could do more to find additional fraud in UK aid. We acknowledge that fraud, by its nature, is often hard to find. Nevertheless, through our interviews and anonymous survey, we sought to explore why so little fraud is reported.

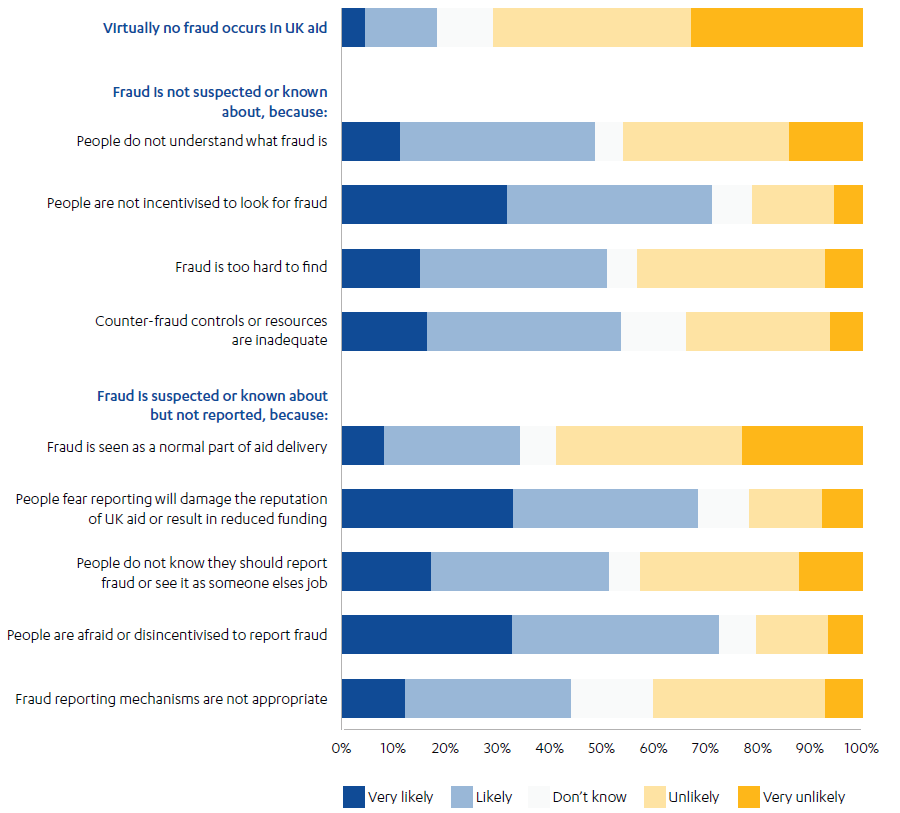

Most stakeholders believe more fraud is taking place but that people are disincentivised from reporting it

When asked why so little fraud is reported in UK aid, four in five respondents believe it was unlikely that virtually no fraud occurs in UK aid (excluding 45 who did not know). The top three reasons given for why so little fraud is reported in UK aid related to disincentives are:

- People are afraid or disincentivised to report fraud (73% considered this likely or very likely).

- People are not incentivised to look for fraud (71% considered this likely or very likely).

- People fear reporting will damage the reputation of UK aid or result in reduced funding (69% considered this likely or very likely).

Box 6 is an example of disincentives experienced by a government official reporting fraud.

Box 6: Anonymised example: disincentives for reporting fraud

A UK government official informed us their department deployed them to a country with high fraud risk with no prior counter-fraud or programme management training. On arrival, they were assigned management of an ODA programme which, in their view, had poor controls and records in place. The official was alerted to a fraud allegation and reported it, but felt unsupported in their investigation and that their career progression opportunities were at risk.

The official highlighted both a historical poor understanding of how to manage risks and a reluctance to report fraud in the country office. The official has since moved to another government department. We found that the department did investigate the fraud and ultimately could not prove fraud, although the first-tier partner had exploited weak contract terms and contract management.

Figure 5: Stakeholder perspectives on why so little fraud is reported in UK aid

There is increased focus on risks down the delivery chain but poor intelligence sharing at the first-tier partner level

Based on our sample, practical efforts to reduce fraud risk down the delivery chain are generally well considered at the country and portfolio level and in programme design. Fraud investigations identified the main weaknesses, found in programme management rather than design or mobilisation. This does not prove that weaknesses do not exist in other areas, only that those found generally relate to programme management.

DFID has implemented mandatory delivery chain risk mapping, which includes fraud risks, and this is being adopted by other departments. One of the fraud cases we reviewed was a legacy programme originally funded in 2008 by both DFID and the former Department of Energy and Climate Change, before BEIS was established. DFID and BEIS noted that supply chain risk mapping was not required or undertaken at the time. A major fraud subsequently occurred and an independent forensic audit highlighted weaknesses in the fund’s procurement process and conflicts of interest, fraudulent travel expenses and unsupported payments. In this case the fraud loss was recovered from the recipient government, whose officials were found to have acted fraudulently. We were informed that learning from this contributed to BEIS adopting supply chain risk mapping for ODA programmes, based on the approach developed by DFID. Separately, a Home Office official told us that while supply chain risk mapping is not mandatory in the Home Office, several programme managers are starting to apply it themselves.

Standard contract terms for former DFID, former FCO, BEIS and DHSC include a requirement for a due diligence assessment, which looks at risks and controls in potential first-tier partners before finalising a contract. With one older CDC investment, we found that due diligence at the time was inadequate to identify key risks. In that case, following investment, CDC and other development finance institutions (DFIs) identified concerns in how slowly funds were being deployed, leading to the DFIs recalling their investment. The fund later collapsed. CDC noted that this event, and the lessons learned from it, resulted in new industry-wide practice emerging with an enhanced focus on and transparency around business integrity risks for investors into investment funds, including strengthened monitoring and engagement on such risks post investment. This is also reflected in subsequent changes made in CDC’s own due diligence and risk management practices which, if followed, should help to prevent similar occurrences.

There is no systematic process, however, for sharing due diligence or risk concerns about partners across and even within departments. There are legal restrictions on how to share and use information on a supplier’s past performance due to data protection and procurement rules. However, this lack of visibility of supplier risks across and within departments puts counter-fraud functions at a disadvantage. ICAI has raised similar issues about intelligence sharing in its reviews of procurement and fiduciary risk but the issues are unresolved. In response to its 2017 report, NAO noted that DFID agreed it should “assess the ability of its principal non-governmental organisation partners to manage fraud risks and to use these assessments to inform future spending decisions”. Contract terms also allow for government departments to audit first-tier partners, but this is not systematically used to assess first-tier partners’ self-reported risk management capability. There are also still no formal mechanisms to share due diligence and risk concerns within or between departments. We know there are sometimes informal discussions, but this is not satisfactory as it does not facilitate proper analysis and risks fuelling the perceptions of collusion discussed above.

There are some examples of where departments have found ways to consider past performance in bids. BEIS’s Innovate UK funding, for example, has rules that makes bidders ineligible if they have not commercially used the results of a previous BEIS grant. Within DHSC, NHS England has an in-house counter-fraud authority (NHSCFA) that collects and shares intelligence to help prevent economic crime. Learning and intelligence from allegations of fraud informs proactive fraud prevention work and successful prosecutions are publicised internally and externally. Although not focused on ODA, NHSCFA is independent of other NHS bodies and directly accountable to DHSC, so a good example of an independent counter-fraud unit within a government department (see Box 7).

Several of our sample case studies and interviews identified an over-reliance on external audits as a counter-fraud control, especially by more junior staff. As one senior responsible owner said, “It is important not to take a clean audit for a financial year to mean all financial systems and controls are working”. This mirrors concerns raised above about reliance on junior staff to conduct due diligence in relation to contract management. We note that this is one of several controls in place to manage fraud risks, as shown in Table 3.

Box 7: Transparency around fraud losses

The Cabinet Office aims for the UK to be the most transparent government globally in how it deals with public sector fraud. OECD DAC recommendations also encourage transparency. Some departments are embracing this approach more openly than others. DFID did not publicise fraud court actions as it was concerned this could risk losing suppliers. In contrast, NHSCFA is actively working to raise the profile of NHS fraud and increase awareness among NHS staff and the public about the work that the NHSCFA does to tackle fraud. The five-part BBC documentary Fraud Squad NHS made the top 20 most watched BBC shows in 2019 and was credited with a 100% increase in fraud referrals to the NHSCFA reporting line during the week the show aired. It also targeted engagement with those working in priority areas of pharmaceutical and procurement fraud, resulting in increased referrals in those specific areas.

FCO had publicly reported a list of counter-fraud cases including a description of the allegation, the resolution and any sanctions, gross and net loss, and a brief summary of lessons learned for each case. We commend this level of transparency. Similarly, the British Council, an arms-length body sponsored by FCDO (formerly FCO), has published internal and external fraud cases since 2016-17. It won the 2019 Charity Fraud Team of the Year at the Charity Fraud Awards, an initiative run by the Charity Commission and the Fraud Advisory Panel. This was in part down to its transparency on fraud reporting.

Disincentives to look for and report fraud mean even some known frauds are not being reported

Our programme reviews and interviews showed that the need to report suspected fraud is communicated to delivery partners across all departments. Survey responses indicate that this expectation is well understood. This is not matched, however, with incentives and accessible mechanisms to easily report concerns. As explained earlier, the main reasons stakeholders believe fraud is under-reported is that people are not incentivised to look for it, afraid to report it, or concerned it will damage the reputation of UK aid or result in budgets being cut.

Out of 421 survey respondents, 54 said that they had suspected fraud in UK aid but not reported it. Twenty-four said that they had known about a fraud but not reported it. In addition, 34% of all respondents said that some types of fraud cannot be avoided in the types of aid that they have experience with, and 23% said that some facilitation payments are necessary to achieve UK aid objectives. Facilitation payments – “payments to induce officials to perform routine functions that they are otherwise obligated to perform” – are illegal anywhere in the world under the UK law, although they are commonplace in many countries where UK aid is delivered.

We do not have further information about the size of facilitation payments and frauds referred to in the above paragraph. Facilitation payments are often small payments and most of the country-level frauds that are reported are for relatively small amounts. Nevertheless, combined, these responses (not reporting suspected fraud, believing some bribes are necessary and feeling disincentivised from reporting) suggest a context where many in the delivery chain feel they are not able to talk openly about fraud concerns that are an everyday reality to them.

Most detected fraud losses are recovered. Although we do not have a breakdown for ODA overall, in the case of DFID from 2016-17 to 2019-20, gross fraud losses of £25.3 million were detected. Of this amount £23.7 million were reported as recovered, leaving a net loss of only £2.6 million out of an expenditure of over £42 billion, ie 0.006%. Where fraud is reported as recovered, however, this does not mean it is recovered from the fraudster. In many cases it is the first-tier partner that covers the cost through its own reserves, surpluses in other areas or insurance. While this reduces the apparent loss to taxpayers, the costs are not eliminated from the aid delivery system. In one interview, a government official recalled an incident where, once the department had recovered the costs from the first-tier partner for suspected fraud in a sub-partner, the department considered the matter resolved and did not support the first-tier service provider to recover funds from its downstream partner. This adds a disincentive for service providers to report while not necessarily acting as a deterrent for the actual fraudster.

Conclusion on effectiveness

In practice, efforts to address fraud risk down the delivery chain are well considered at the country and portfolio level and the need to report suspicions of fraud is understood by staff and delivery partners. There are, however, a range of disincentives for stakeholders to look for or report fraud, limiting the effectiveness of fraud detection. This is likely to contribute to the low levels of detected fraud cases. There is good practice by internal audit teams analysing data to identify areas to target within the department, helping to strengthen controls and knowledge internally. However, when it comes to risks down the delivery chain, third line counter-fraud practice tends to focus on referrals, rather than proactively analysing data and targeting investigations based on risk factors. While contracts give government departments the right to audit suppliers and access their due diligence of downstream partners, there is high reliance on self-reporting by contractors. This right is not systematically used to assess partners’ claimed capability or the quality of downstream audits. This suggests more could be done to find fraud in UK aid through making it easier for stakeholders to report fraud and a better use of data by counter-fraud teams to learn more about fraud and target higher risk areas.

Learning: how effectively do departments capture and apply learning in the development of their systems and processes for fraud risk management in their aid programmes?

Learning takes place through the fraud investigation process

When each of the departments investigates fraud, they set out to learn how it occurred. For the 12 alleged fraud cases we reviewed, this was done as expected and for ten of these we saw evidence that learning was then taken up with the delivery partner and/or internally as appropriate. Box 8 shows an example of where fraud was identified through good programme monitoring and which also highlights the potential for increased risk due to changes in aid spending, such as those necessitated by COVID-19 and cuts to the aid budget.

Box 8: Anonymised example: changing risk factors

Payments fraud occurred in a programme where funding was due to end in a high-risk country. The fraud came to light when the programme manager investigated apparent gaps in a grant audit statement. The department recovered the losses from the first-tier partner but did not identify the motivation for the fraud which occurred after a positive relationship over several years. Following the investigation, the department produced a ‘lessons learned’ paper and presentation to share with programme teams across the department. We saw evidence that the department had adopted new measures through implementing this learning, including establishing a new quarterly board for the programme and monthly programme managers’ meetings.

Although unproven, the official we interviewed believed that the motivation for fraud was because the supplier knew that funding was going to end. In their view, there was a reliance by the supplier on UK aid funding and, when a currency devaluation occurred, it gave the supplier the opportunity to overclaim without exceeding their contractual budget. This is a potential example of how a change in circumstances – in this case ending funding combined with currency devaluation – can affect the factors that drive fraud risk (opportunity, rationalisation, motivation). The official learning document had not captured these perspectives, even though they may apply to others where funding is being cut.

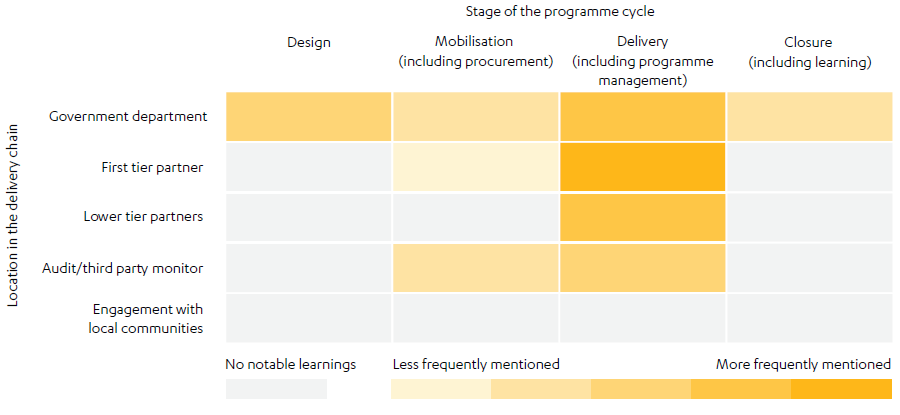

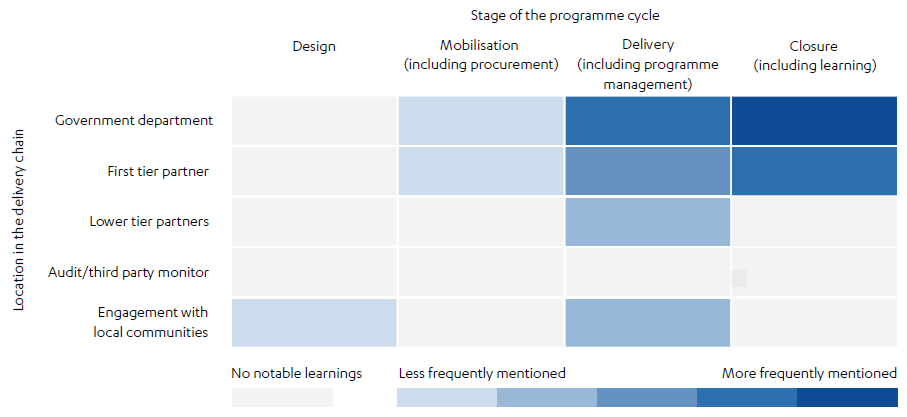

We mapped the learning processes for the programmes we reviewed with suspected fraud to identify where issues occurred during the programme lifecycle and down the delivery chain, and lessons learned. In each case, programme officials aimed to understand what went wrong and what they could learn from it. In most cases, they also identified examples of good practice, typically relating to how departments identified and communicated suspected fraud. In Figure 6, the top chart shows our assessment of where programme officials identified weaknesses in the programme lifecycle and delivery chain; the bottom chart shows identified examples of good practice.

We note that this is a small sample and the data set comprises only reported suspected frauds. Nevertheless, in the cases we reviewed, the blame for what goes wrong largely falls in the management part of the programme lifecycle; ie executing the design and contract. In this sample, we identified relatively few weaknesses in the design or procurement process. The key learnings that emerged were:

- Weakness in applying controls, with a reliance on more junior staff to carry out due diligence and other key risk management processes.

- Over-reliance on audits as a risk assurance / counter-fraud measure.

- Most identified frauds happen at the sub-partner level, but weaknesses at the first-tier partner level are often blamed.

- Positive evidence that learning is being fed back into future design or used by suppliers to strengthen their systems.

Figure 6: Where government officials identified learning in our sample of fraud reviews

Where weaknesses were identified in the delivery chain and programme cycle

Where good practice was identified in the delivery chain and programme cycle

There is a good spirit of learning between departments, but it is mostly informal