Tackling fraud in UK aid: country case studies

Executive Summary

Fraud and corruption divert aid from those that need it and entrench poverty and inequality by undermining the systems needed to deliver sustained social, environmental and economic progress. The UK delivers aid programmes in some of the most challenging environments which often involve significant fraud and corruption risks. How the UK protects this spending from fraud is therefore of utmost importance, both to ensure UK taxpayer money is not diverted to corrupt individuals and entities and to safeguard the social, environmental, economic and governance gains it aims to support.

The Public Sector Fraud Authority (PSFA) estimates between 0.5% and 5% of all government spending is lost to fraud and error. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) reported overall detected fraud of £2.2 million in 2020-21 compared to total expenditure of £9.9 billion, a detected fraud loss rate of 0.02%. The PSFA considers reporting of ‘near zero’ levels of fraud to be an indicator of poor value for the taxpayer because it shows that either fraud is not being found or that controls are so tight that the quality of delivery is compromised.

This supplementary review builds on findings and themes from the earlier reviews of fraud and governance in UK aid by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI). It assesses how effectively fraud risk is managed in aid programmes delivered through the UK’s global network of embassies, high commissions and other UK government offices, overseen by FCDO Heads of Mission – the UK’s ambassadors and high commissioners. It draws on the principles for public sector fraud as set out by the UK’s Public Sector Fraud Authority:

- There is always going to be fraud

- Finding fraud is a good thing

- There is no one solution

- Fraud and corruption are ever changing

- Prevention is the most effective way to address fraud and corruption

During its third commission, ICAI conducted a series of rapid reviews on programme governance and counter-fraud measures in aid spending. Our 2021 review, Tackling fraud in UK aid, assessed how the five biggest aid-spending departments tackle fraud in their aid delivery chains. The review found that measures to prevent and investigate alleged fraud were operating as designed but that detection levels remained low across all departments. It highlighted how individuals and organisations are disincentivised from finding and reporting fraud.

Our 2022 review, Tackling fraud in UK aid through multilateral organisations, assessed how the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) ensures the effective management of fraud risks in its core funding to multilateral organisations. The review took place following significant reductions in the UK’s ODA budget, which we found had affected FCDO’s ability to influence multilateral partners and increased overall fraud risk at the country level.

Our 2023 review of The FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework, assessed FCDO’s devolved approach to programme governance and risk management as set out in its Programme Operating Framework (PrOF). This found that while the PrOF has the potential to enable agility and context-appropriate decision-making, its devolved approach requires country-level leadership and local capability and capacity to be effective.

Due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, country visits were not possible for these reviews. Therefore, this supplementary review focused on the experience of in-country programme staff who manage fraud risk on a day-to-day basis and comprise the ‘first line of defence’ to fraud. This included how well the first line is supported by the rules, guidance, intelligence sharing and training which comprise the ‘second line of defence’. The review centred on three in-depth case studies including country visits (Mozambique, Kenya and India), and five case lighter-touch studies conducted remotely (Lebanon, Montserrat, Myanmar, Somalia and

Syria). For each of our in-depth case studies we identified strengths, weaknesses and opportunities. These findings were combined with our remote case studies, interviews with central staff and document reviews to enable us to answer our review questions.

Efficiency: How efficiently does the UK government deploy resources to ensure robust country-level fraud risk management in the aid delivery chain?

Programme teams build long-term local knowledge through locally hired staff, while UK staff posted overseas periodically rotate to bring cross-learning and refreshed scrutiny. This can be undermined, however, if UK staff rotate too frequently and where FCDO struggles to compete for local talent. We also identified areas of potential inefficiency, such as in FCDO’s outsourcing of risk management processes to delivery partners and in managing very small fraud cases.

FCDO has failed to build its second line of defence both centrally and in-country. Its network of fraud liaison officers is a missed opportunity. Central counter-fraud capability is under-resourced and has been unable to take a proactive approach to tackling fraud. This has left in-country counter-fraud capability vulnerable. Similarly, the lack of investment in effective training for programme staff on FCDO’s new finance system, Hera, has led to inefficiencies and increased risk.

A strong second line is essential to support, monitor and challenge the first line of defence.

Effectiveness: How effective are the UK’s overseas teams at identifying and responding to fraud allegations and concerns in aid delivery?

FCDO has good processes for fraud prevention and to investigate reported cases that staff understand and apply effectively. Programme teams recognise the importance of building good relationships to encourage openness about fraud. FCDO is recognised as taking fraud risk management seriously by partners, although programme teams do not travel to project sites as much as they would like and a lot of reliance is placed, sometimes unduly, on due diligence assessments, third-party reporting and audits.

Processes are focused on preventing fraud, which is important, but not on finding it. The second line of defence, both centrally and in-country, is better at supporting teams to implement processes than searching for problems or gathering intelligence. The message that “finding fraud is good” is beginning to get through, but many staff and partners are wary and virtually no fraud is reported compared to FCDO’s spend.

A range of major influences, including the merger to form FCDO, COVID-19, ODA budget reductions and the implementation of a new finance system, have increased the risk of fraud while also distracting programme staff. It is a testament to teams that they have maintained good programme management practices, but good processes are not enough to effectively tackle fraud.

Coherence: How well does the UK work across different UK government teams, departments and bodies (internal coherence), and with external partners (external coherence), to tackle fraud in aid delivery?

FCDO has a strong reputation for taking fraud seriously with partners and donors, which gives it an opportunity to play a leadership role in promoting better coherence in tackling fraud. There are barriers to systematic data and intelligence sharing, but co-operation among like-minded actors is all the more important in the shifting geopolitical landscape.

FCDO has a huge amount of experience of tackling fraud and corruption in its anti-corruption programming, and pockets of expertise elsewhere in its network, including its arm’s length entities British Council and British International Investment, and across other UK bodies and government departments. However, FCDO is not using this knowledge to help promote a coherent approach to fraud across all the UK’s aid delivery.

Heads of Mission do not have clear visibility of the centrally managed programmes that operate in their countries and there is significant variation in Heads of Mission’s understanding of their responsibility for risk in these programmes. FCDO teams in-country are working to address this, but each country is doing it independently.

Overall, FCDO is not doing enough to match its counter-fraud capability to evolving risks faced by programme staff in the field. While it has strong counter-fraud processes and diligent programme staff who have good relationships with partners, it places insufficient value on the professional development of in-country counter-fraud and programme staff, and has under-invested in its central and in-country second line of defence. The lack of robust second-line capacity has two concerning consequences. The first is that as fraudsters evolve and become more sophisticated, FCDO risks being left behind in areas such as cybercrime, artificial intelligence and the use of big data. The second is that in-country staff are not properly supported. FCDO risks relying on the accumulated skills and capabilities of former Department for International Development programme management staff rather than adapting to meet the ever-changing fraud landscape.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

FCDO should take a substantially more robust and proactive approach to anticipating and finding fraud in aid delivery.

Recommendation 2

FCDO should strengthen its second line of defence in the top 20 ODA recipient countries, allocating dedicated, well-trained and sufficiently senior resources to manage fraud risks.

Recommendation 3

FCDO should develop specific guidance on capital investments within its Programme Operating Framework.

Recommendation 4

FCDO should increase Head of Mission oversight of and accountability for fraud risks relating to centrally managed programmes and other government department programmes that operate in their country.

1. Introduction

1.1 Fraud and corruption not only divert aid from those that need it, but entrench poverty and inequality by enriching corrupt and powerful individuals and undermining the systems and culture needed to deliver sustained social, environmental and economic progress.

“As a direct result [of corruption], education, health and other development priorities remain underfunded; the natural environment is ravaged; and fundamental human rights are violated. Those who suffer the consequences are ordinary citizens, and particularly those most left behind.”

Transparency International

1.2 The UK is the sixth-largest official development assistance (ODA) donor. Anti-corruption programmes play a part in the UK’s ODA programming, but amount to less than 0.2% of the total ODA spend across all sectors. The UK spends ODA in some of the most challenging environments which often involve significant fraud and corruption risks. How the UK protects all of its ODA from fraud is therefore of utmost importance, both to ensure UK taxpayer money is not diverted to corrupt individuals and to safeguard the social, environmental, economic and governance gains it aims to support.

1.3 The UK participates in the International Public Sector Fraud Forum (IPSFF) along with Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States to share good practice in fraud risk management. The UK’s Public Sector Fraud Authority guidance for effective fraud control in ODA has adopted IPSFF’s five principles, as shown in Figure 1.

1.4 This supplementary review focuses on the challenges that the UK’s country teams face in managing fraud risk at the country level. Drawing on the principles in Figure 1, it assesses how effectively fraud risk is managed in ODA delivered through the UK’s global network of embassies, high commissions and other UK government offices, overseen by Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) Heads of Mission – the UK’s ambassadors and high commissioners.

Table 1: Our review questions

| Review criteria and questions | Sub-questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Efficiency: How efficiently does the UK government deploy resources to ensure robust country-level fraud risk management in the aid delivery chain? | • How does the UK allocate resources to manage fraud risks in-country, including if there are staff shortages or other resource constraints? • How does the UK ensure value for money of the training and support provided to first-line country staff? • How does the UK engage with partners and other third parties to manage in-country fraud risk efficiently in the delivery chain? • How well do different UK government teams, departments and bodies share and use each other’s fraud risk knowledge, learning and good practice in-country? • How does the UK identify fraud risks at the country and programme level? • How do country staff learn of fraud allegations or concerns, and how quickly and appropriately are they managed? • How well do country staff understand fraud risks in their portfolios? • How do different UK government teams, departments and bodies ensure a joined-up approach to counter-fraud in-country (both in terms of systems and strategies)? • How well do country staff work with central teams to apply good counter-fraud practice? • How effectively does the UK contribute to a coherent approach to fraud risk management in aid delivery overall in the country (both in terms of systems and strategies)? |

| 2. Effectiveness: How effective are the UK’s overseas teams at identifying and responding to fraud allegations and concerns in aid delivery? | |

| . Coherence: How well does the UK work across different UK government teams, departments and bodies (internal coherence), and with external partners (external coherence), to tackle fraud in aid delivery? |

2. Methodology

2.1 This supplementary review is based on case studies of how country staff manage fraud risk in programmes that include official development assistance (ODA). It supplements a series of rapid reviews looking at fraud and governance in ODA since 2020:

-

- Tackling fraud in UK aid, published in 2021.

- Tackling fraud in UK aid through multilateral organisations, published in 2022.

- The FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework, published in 2023.

2.2 Due to COVID-19 travel restrictions, fieldwork was not possible for the previous reviews. This review was designed to complement and follow up on the themes identified in the earlier reviews, summarised in Section 3, by focusing on the perspectives and experiences of the UK’s overseas programme staff. We used case studies to assess how well fraud risk is managed at the country level and to draw out examples of good practice, areas of weakness and learning opportunities relevant to wider fraud risk management in the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and other UK government departments that manage ODA programmes.

2.3 Our methodology comprised the following components:

- Review of the current FCDO and cross-government guidance and FCDO fraud data.

This included reviewing documentation provided by, and interviewing, central, UK-based FCDO counter-fraud staff. We also reviewed FCDO fraud reporting data and documentation for a sample of six significant closed cases of suspected fraud reported through FCDO’s systems. This provided context for our case studies and insight into developments in FCDO’s fraud risk management since the earlier reviews.

- In-depth country case studies: India, Kenya and Mozambique.

These included field visits and involved:

- A review of relevant FCDO and public materials for the country, such as risk assessments and fraud reporting data, and interviews with senior officials responsible for fraud risk management.

- Interviews with programme management staff and a review of risk management documentation for a diverse sample of three to five programmes per country.

- Interviews with key external stakeholders such as delivery partners, local civil society organisations, other aid agencies and donors, local counter-fraud professionals and experts, and host government officials.

These case studies provided a deeper view of fraud risk management in country-specific ODA-funded programmes. The in-country work helped us understand the interface between policy, guidance, and practice and how this is informed by attitudes and behaviours towards fraud and fraud risk management by staff with these responsibilities. They form the core part of this review and enable comparison between different countries, programmes and contexts.

- Supplementary case studies: Lebanon, Montserrat, Myanmar, Somalia and Syria.

For a further five countries, we undertook:

- A review of relevant FCDO and public materials for the country, such as risk assessments and fraud reporting data.

- Interviews with programme management staff and review of risk management documentation for a sample of one to two programmes per country and a sample of fraud reporting and whistleblowing cases where applicable.

These case studies provided breadth to the review and enabled us to compare approaches across a wider range of countries and programmes, including those with smaller ODA budgets and conflict-affected environments where aid delivery is managed remotely.

2.4 The three in-depth case studies are presented in Section 4 of this report, including strengths, weaknesses, challenges and opportunities that we observed. These, combined with the other aspects of the methodology, inform a discussion about the overall efficiency, effectiveness and coherence of fraud risk management in UK aid delivery in the second part of Section 4. Our conclusions and recommendations in Section 5 relate to this wider analysis.

Our review approach to fraud and wider corruption

2.5 The UK’s 2006 Fraud Act describes fraud as making a false representation, failing to disclose relevant information or the abuse of position to make financial gain or misappropriate assets. While fraud requires intentional deceit or abuse of power, for this review we took a broad interpretation of fraud, including bribery, theft and other corrupt acts relating to UK ODA. This is consistent with our approach in previous reviews. In addition, this review looks both at the risk of fraud to UK ODA and the risk that UK ODA enables fraud of third parties. We did not, however, audit any data or systems, nor did we seek to identify new fraud cases or quantify fraud levels in UK aid.

2.6 Further details about our scope and methodology are provided in the approach paper published in December 2023.

3. Background

3.1 The UK’s global network of embassies, high commissions and other government offices, overseen by its Heads of Mission – the UK’s ambassadors and high commissioners – brings together the UK’s diplomatic and aid delivery capability to promote the UK’s interests and tackle poverty and global challenges through overseas partnerships. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) has more than 17,000 staff in diplomatic and development offices worldwide, including 281 embassies and high commissions. FCDO Heads of Mission have overall responsibility for the UK’s strategy and risk management in each country. Other government departments with overseas operations deliver programmes according to their own procedures, but their country-based officials also have a reporting line to the FCDO Head of Mission.

3.2 In 2022, the UK delivered £2.4 billion (18%) of the UK’s £12.8 billion ODA expenditure though country specific bilateral programmes. Of this, FCDO managed £2.1 billion (27% of FCDO’s £7.6 billion total ODA expenditure), with other government departments managing the remainder. Country-specific bilateral ODA is primarily managed by staff based in the country of delivery. It excludes global and regional programmes and core contributions to multilateral organisations (covered in previous reviews in this series), but includes some country-specific expenditure managed by staff based in the UK or a third country for security, political or logistical reasons, such as in the case of the UK Office for Syria which has staff based in the UK and Lebanon.

ICAI reviews before the DFID-FCO merger

3.3 Financial governance and fighting fraud and corruption have been key themes for the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) since its inception in 2011. Prior to the creation of FCDO in 2020 – merging the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) with the Department for International

Development (DFID) – ICAI’s reviews in this area focused primarily on DFID. ICAI’s programmatic reviews have uncovered major governance failings, such as its reviews of Girl Hub in 2012 and TradeMark Southern Africa in 2013, leading to urgent changes at both the programme level and in DFID-wide risk management processes, such is its pre-grant due diligence.

3.4 ICAI’s thematic reviews in this area include the 2011 review of DFID’s approach to anti-corruption, which highlighted the need for greater co-ordination in DFID’s approach to risk management, anti-corruption programming and fraud resourcing. A subsequent review in 2014 recommended more programmes targeting everyday corruption experienced by the poor, and for DFID to gather evidence of effectiveness in anti-corruption measures, disseminate lessons learned and cultivate expertise to help drive anticorruption efforts globally.

3.5 ICAI’s 2016 review of DFID’s approach to managing fiduciary risk in conflict-affected environments commended DFID for good practice in identifying fiduciary risks in programme design and implementing measure to mitigate risks in challenging contexts. However, the review raised concerns about confusion among staff and partners about what it meant for DFID to have “‘zero tolerance’ to fraud and corruption” in high-risk environments, and the potential for this messaging to discourage reporting of suspected fraud and corruption. The report also recommended that DFID clarify expectations around risk transfer down the delivery chain and improve transparency and monitoring of fiduciary risks in bilateral

programmes implemented by multilateral partners. DFID responded positively, strengthening guidance around risk appetite, and implementing supply chain mapping for all programmes, including those with multilateral partners.

ICAI fraud reviews after the formation of FCDO

3.6 ICAI’s 2021 review, Tackling fraud in UK aid, looked across five ODA-spending government departments: DFID, FCO, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (formed in 2016 and dissolved in 2023), the Home Office and the Department of Health and Social Care. Research for this review coincided with the merger of DFID and FCO in September 2020. At this time, former DFID and FCO programme management and counter-fraud systems and functions were still being operated in parallel. As the review was looking at past performance, we assessed DFID and FCO as separate departments but with a view to providing timely insights for the newly formed FCDO. The review also took place during COVID-19 travel restrictions and provided initial learning about how this had impacted fraud risk management, especially the necessity for remote monitoring.

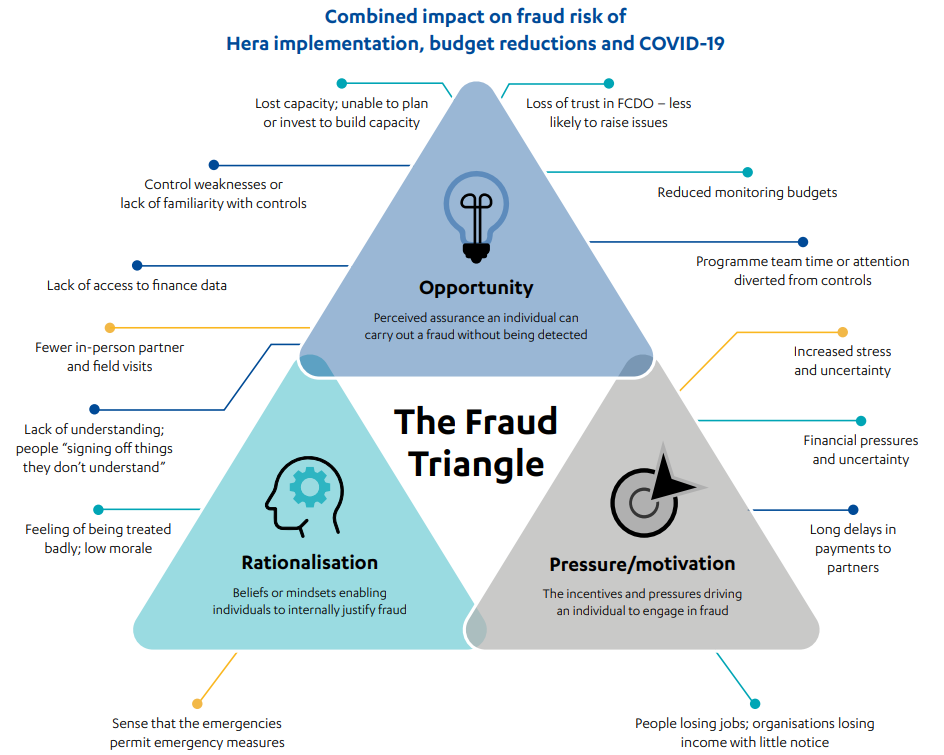

3.7 Due to travel restrictions, this review focused on the risk management support functions (central second line of defence) and fraud reporting and investigation (third line of defence). We also surveyed more than 400 frontline staff, counter-fraud professionals and delivery partners (first line of defence) to understand their perceptions of fraud in UK aid. The review found that measures to prevent and investigate alleged fraud were operating as designed but that detection levels remained low across all departments. Among former DFID staff we found that the understanding of ‘zero tolerance to fraud’ had evolved since our 2016 review to be understood as “fraud risks can be taken with proportionate controls in place [and] zero tolerance for inaction to prevent and quickly rectify problems when they come to light”.

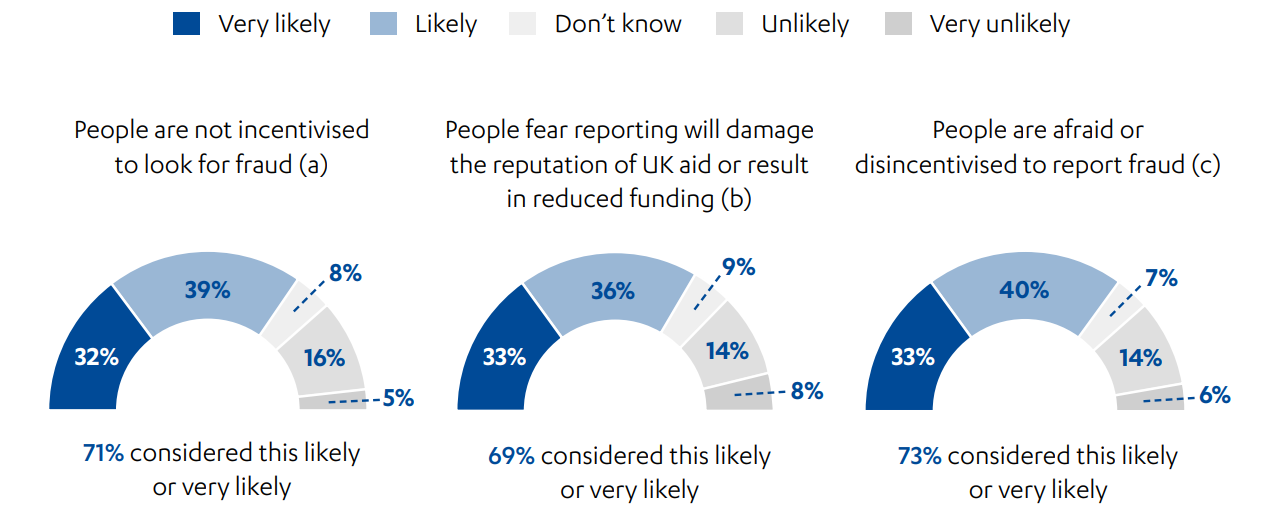

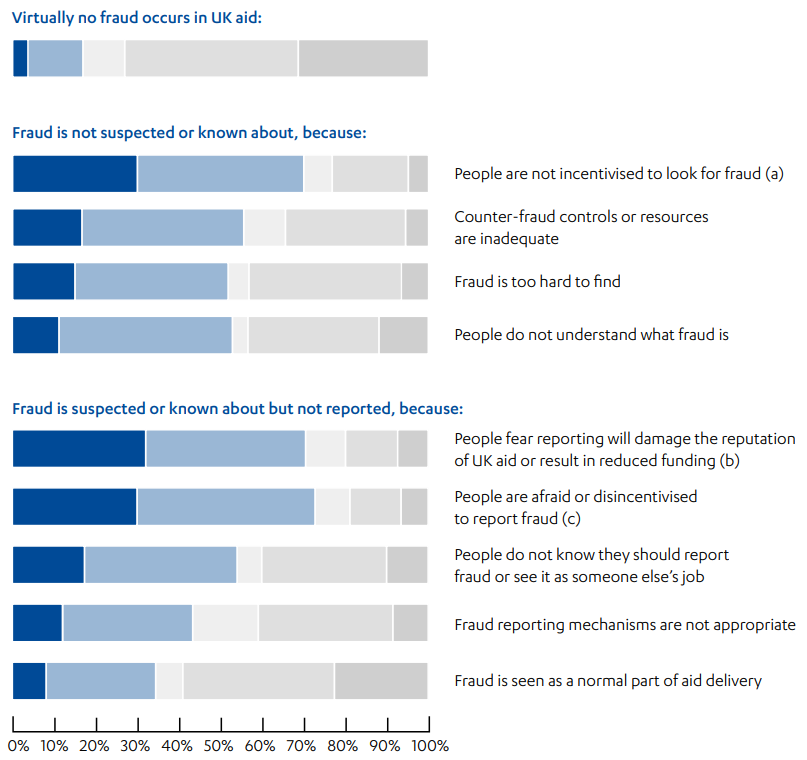

3.8 This more nuanced understanding was not shared across all departments or by partners, including DFID partners, risking the unintended of consequence of burying fraud deeper, as individuals and delivery partners down the delivery chain fear the consequences of reporting fraud. Our 2021 survey aimed to understand why so little fraud is reported (see Figure 2). The main reasons given were:

- People are not incentivised to look for fraud (71% considered this likely or very likely).

- People fear reporting will damage the reputation of UK aid or result in reduced funding (69% considered this likely or very likely).

- People are afraid or disincentivised to report fraud (73% considered this likely or very likely).

3.9 Two key disincentives identified in ICAI’s 2021 review were, first, the administrative burden that results from information demands when reporting fraud and, second, that delivery partners often bear the fraud costs, rather than these being successfully recovered from the fraudster.

Figure 2. Stakeholder perspectives on why so little fraud is reported in UK aid

3.10 This review made four recommendations (see Box 1), consistent with good practice set out by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee. This includes that agencies should work towards a comprehensive system for corruption risk management, such as: codes of ethics; whistleblowing mechanisms; financial control and monitoring tools; sanctions; co-ordination to respond to corruption cases; and communication with domestic constituencies (taxpayers and parliaments) on the management of corruption risks. It also states that agencies should “communicate clearly about how confidential reports can be made, including providing training if necessary, and streamlining channels to reduce confusion”. It suggests that agencies should “communicate clearly and frequently about the processes and outcomes of corruption reporting, to build trust and reduce any perception of opacity around corruption reports and investigations”.

Box 1: Recommendations from the 2021 Tackling fraud in UK aid review

Prior recommendation 1: Consideration should be given to establishing a centralised ODA counter-fraud function to ensure good practice and consistency of the ODA counter-fraud response and share intelligence across all ODA spend.

Prior recommendation 2: ODA-spending departments should review and streamline external whistleblowing and complaints reporting systems and procedures, and provide more training to delivery partners down the delivery chain on how to report safely.

Prior recommendation 3: Counter-fraud specialists should increase independent oversight of ODA outsourcing, including systematically reviewing failed or altered procurements and advising on changes to strengthen the actual and perceived integrity of ODA procurement.

Prior recommendation 4: To aid understanding and learning, ODA counter-fraud specialists should invest in collecting and analysing more data, including on who bears the cost of fraud, and trends in whistleblowing and procurement.

3.11 While the government decided not to introduce a centralised ODA counter-fraud function, it did establish an ODA Counter Fraud Forum led by FCDO to help ensure good practice and consistency of the ODA counter-fraud response and share intelligence across all ODA-spending departments. Progress on the remaining recommendations, however, was hampered by severe and protracted resource shortages and staff turnover in FCDO’s central counter-fraud and investigations teams following the DFID-FCO merger. As a result, ICAI’s follow up reviews published in 2022 and 2023 found that little progress had been made in addressing recommendations 2, 3 and 4. Further developments relating to these recommendations are included in Section 4 of this report.

3.12 ICAI’s 2022 review, Tackling fraud in UK aid through multilateral organisations, assessed how FCDO ensures the effective management of fraud risks in its core funding to multilateral organisations, which was excluded from the scope of the 2021 review. This review took place following significant reductions in the UK’s ODA budget, which we found had affected FCDO’s ability to influence multilateral partners. Also, unplanned budget reductions increased overall fraud risk at the country level, creating gaps in local mechanisms and heightening fraud risk in affected programmes. FCDO’s response to this review has led to a more joined-up approach to managing fraud risks across FCDO’s portfolio of multilateral organisations, including better knowledge sharing between FCDO’s multilateral teams, and peer review of central assurance assessments.

FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework and risk management

3.13 FCDO has a devolved approach to programme governance and risk management, set out in its Programme Operating Framework (PrOF). This framework is based primarily on the rules, principles and guidance that evolved during years of DFID aid delivery, adapted for the FCDO context. The PrOF was rapidly developed after the September 2020 merger of DFID and FCO and launched on 1 April 2021, in time for the first financial year of the newly formed department. FCDO intended the PrOF to establish a common approach to ODA and non-ODA programme management across the new department. It provides the basis for how FCDO programmes should be managed to ensure high standards and meet central government expectations.

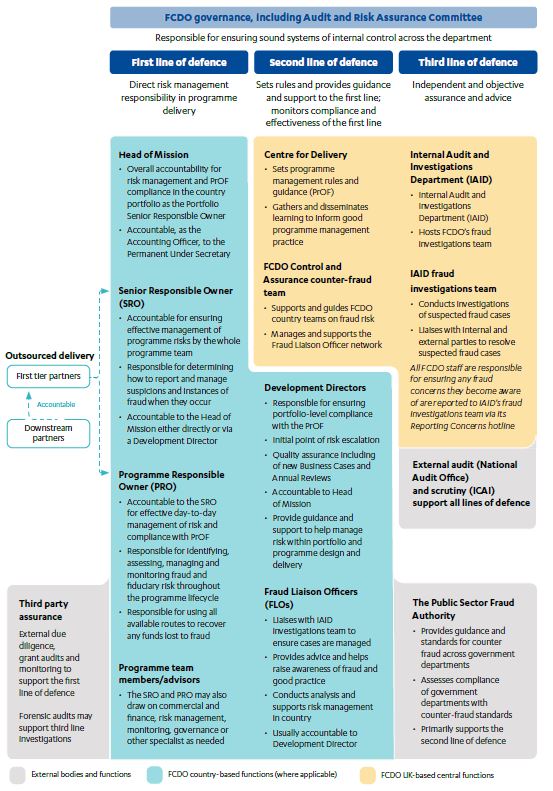

3.14 The PrOF applies to all FCDO policy programmes, not just ODA, but does not apply to other government departments, some of which also manage country-specific ODA programmes. Other government departments manage and are accountable for programmes according to their own procedures, but their country-based staff also have a reporting line to the FCDO Head of Mission, who is responsible for in-country risk management.

3.15 ICAI’s 2023 rapid review of The FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework found that while the PrOF has the potential to enable agility and context-appropriate decision-making, its devolved approach requires country-level leadership and local capability and capacity to be effective. The PrOF defined a new set of roles for programme delivery (see Box 2 and part 4 of the publicly available PrOF document). Changes to the senior responsible owner (SRO) role, to make it more senior, and the addition of a programme responsible owner (PRO) reporting to the SRO, has also helped to align FCDO with other government departments. The addition of a portfolio SRO at the Head of Mission level situates the devolved model within a country-level portfolio approach to delivering UK priorities that supports coherence between FCDO’s programmes and policy work. These have the potential to make FCDO’s ODA and non-ODA programming better at delivering strategic goals, but we found the roles to be poorly understood by programme staff and limited engagement with the PrOF at the Head of Mission level. FCDO responded positively to our recommendations, including relating to these findings.

Box 2: Risk management responsibilities from Guidance for PrOF Rule 18

“SROs are accountable for ensuring effective management of risks to programme objectives. When required, the programme SROs must escalate risks to development directors, Heads of Mission, heads of department or directors, depending on their line management chain and the level of risk.

“PROs are responsible for leading an active risk management process in their programmes, which brings risks in line with risk appetite, and for ensuring that SROs are aware when risks exceed appetite or need to be escalated for information or further support.

“[Heads of Mission]/directors [i.e. portfolio SROs] are accountable for ensuring effective management of risks to the delivery of country plans / business plans. Development directors are accountable for ensuring effective management of risks to the development objectives within country plans. This includes embedding the right values and behaviours, putting risk at the heart of decision-making, and ensuring appropriate resources and systematic implementation of risk policies and practices in their business areas.”

Source: FCDO Programme Operating Framework, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office

3.16 The PrOF is a critical tool for ensuring effective fraud risk management and many of the rules relate directly or indirectly to good counter-fraud practice. Central to the PrOF are 10 principles and 30 mandatory rules that govern FCDO’s programmes. Each rule has associated guidance, but it is up to programme staff to decide how to implement the rules based on the PrOF principles. Figure 3 sets out the PrOF principles and summarises key rules relating to fraud risk management.

Figure 3: PrOF principles and key rules relating to fraud risk management

The UK’s Public Sector Fraud Authority

“The fraud perpetrated against aid in its many guises is not victimless – it has a clear and immediate impact on life-saving projects across the world as well as undermining the hard work of those involved from taxpayers onward. Tackling the epidemic of fraud is essential for security, credibility and to ensure all funds have the impact intended.”

Public Sector Fraud Authority

3.17 The UK’s Public Sector Fraud Authority (PSFA) was launched by the Cabinet Office in August 2022 to “transform the way that the government manages fraud” by working “with departments and public bodies to better understand and reduce the impact of fraud against the public sector”. This is part of UK’s aim “to be the most transparent government globally in how we deal with public sector fraud”. PSFA’s remit includes research, analysis and intelligence gathering. It also sets cross-government counter-fraud standards for public bodies and assesses public bodies against these standards, and sets professional standards for staff to develop capability through a counter-fraud profession.

3.18 PSFA estimates between 0.5% and 5% of all government spending is lost to fraud and error. FCDO reported overall detected fraud of £2.2 million in 2020-21 compared to total expenditure of £9.9 billion, a detected fraud loss rate of 0.02%. Similar low levels of detected fraud are reported across UK government departments and by other major donors. Prior to the merger of DFID and FCO to form FCDO in 2020, DFID was detecting fraud losses at 0.06%. PSFA considers reporting of ‘near zero’ levels of fraud to be an indicator of poor value for the taxpayer because it shows that either fraud is not being found or that controls are so tight that the quality of delivery is compromised.

3.19 PSFA ODA guidance sets out some of the main fraud challenges pertinent in aid delivery and indicators of heightened fraud risk. It highlights learning from COVID-19 programmes, including the importance of:

- working with fraud control experts to support the design of the aid scheme

- developing intelligence capability, and collecting and sharing consistent data across donor governments

- including counter-fraud communications campaigns and post-event assurance in programme design to detect fraud and error

- sharing experiences and best practice with international and local partners to build knowledge and expertise.

3.20 A section on ‘Managing counter fraud in the international aid cycle’ in the PSFA guidance sets out how to incorporate good aid practice in each stage of programme delivery from needs assessment to peer review and lesson-learning processes following closure. It links to resources from the US, but not the UK or other countries, namely the US Agency for International Development anti-fraud plan (although this link did not work when we tried to access it on 29 February 2024) and the US Agency for International Development Office of Inspector General, Compliance and Fraud Prevention’s A pocket guide for programme implementers.

3.21 The guidance references a World Bank Development Research Group study on Elite capture of foreign aid that shows “aid disbursements to highly aid-dependent countries coincide with sharp increases in bank deposits in offshore financial centres known for bank secrecy and private wealth management, but not in other financial centres” resulting in an implied leakage rate of 7.5 percent. It also provides real world examples of fraud cases relating to collusion in tendering processes, the creation of false identities of refugees eligible for aid and an instance where an estimated £5 million was diverted to corrupt aid workers, community leaders and business owners though a complex fraud scheme. It unfortunately does not give sufficient details to understand what could have prevented the fraud or how it was found. It is nevertheless a step towards more open discussion to help drive a “change in perspective so the identification of fraud is viewed as a positive and proactive achievement”.

Fraud liaison officers

3.22 FCDO has continued DFID’s network of fraud liaison officers (FLOs) based in country teams. The FLO role is not to investigate fraud (which is the job of the central IAID) but to “encourage reporting of all or any suspicions”, “[advocate] the need for fraud prevention, detection and response across the organisation and [promote] a deeper understanding of FCDO’s zero tolerance approach to fraud”. FLOs should also “challenge inaction and importantly highlight and help to promote best practice”.

3.23 The role is set out in terms of reference but is not mandatory and it is up to each embassy or high commission to decide whether and whom to appoint and what the role should entail in their context. There are no specified qualification, training or experience requirements or recommendations. The terms of reference, however, set out responsibilities FLOs can expect, which are:

- “Liaison and support for Internal Audit and Investigations Directorate (IAID), including oversight of progression of business managed cases

- providing advice and helping to raise awareness

- analysis and risk management.”57

3.24 The FLO role is not full time. While there is no hard rule, FLOs are expected to dedicate an average of 10% of their time to the role.

3.25 A cross-FCDO FLO network provides a forum for discussion between FLOs and with central fraud specialists, intended to provide two-way learning. The terms of reference also states that “FLOs are expected, unless in circumstances where normal duties need to be prioritised, to attend and participate in bi-monthly sessions and conversations on the dedicated [Microsoft] Teams site”. Each government department has its own fraud risk management structure. This review focuses on FCDO’s structure and also how FCDO interacts with other departments in-country. The FLO network applies only to FCDO and there is no indication of any expectation for engagement between FLOs and other government departments.

The three lines of defence model

3.26 FCDO uses an established model of three lines of defence against fraud as shown in Figure 4. FCDO’s first line of defence is typically based in-country, with a few exceptions such as FCDO Syria for security reasons, and FCDO Montserrat which is managed remotely. FCDO’s second line of defence is split between central functions, which include the Control and Assurance counter-fraud team and the Centre for Delivery, and country-specific resources which may include an FLO and a cross-cutting country team such as the Delivery Unit in India or the Accountability and Results Team in Kenya. FCDO’s third line of defence – IAID including the fraud investigations team – is independent of FCDO country offices and based in the UK.

Figure 4: FCDO’s three lines of defence model

Sources: The IIA’s the lines model, Institute of Internal Auditors, p. 3-4, link; FCDO Programme Operating Framework, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, updated 19 December 2023, p. 45, link; FCDO Fraud Response Plan, Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, accessed 20 November 2023, unpublished.

FCDO’s new finance system, Hera

3.27 FCDO was formed in 2020 with the merger of FCO and DFID. At this time, DFID operated a finance system called ARIES and FCO used one called Prism. FCO, however, had already selected a new finance system, Hera, to replace Prism. After the merger, FCDO adopted Hera as the new system for the merged department. Implementing Hera was problematic and delayed. FCDO originally had more ambitious integration and modernisation plans but the government’s Infrastructure and Projects Authority found these “overambitious and unachievable” given FCDO’s resources. FCDO scaled back its ambition to focus on creating a shared IT architecture and integrating former DFID and FCO aid programmes onto a common platform. Hera was finally launched in June 2023 although some functionality, such as access to full programme finances where some data was previously on ARIES, was not available until later in 2023. The implications of the Hera implementation for the efficiency and effectiveness of fraud risk management are discussed in Section 4 of this report.

4. Findings

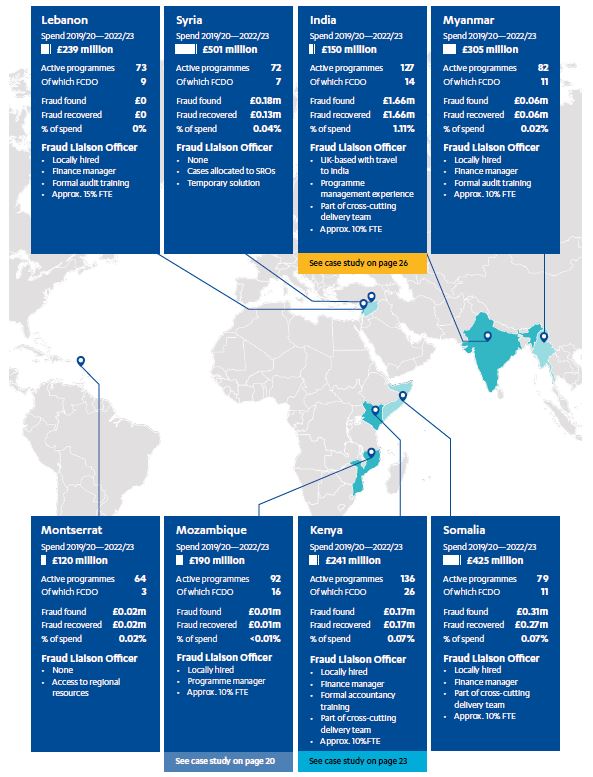

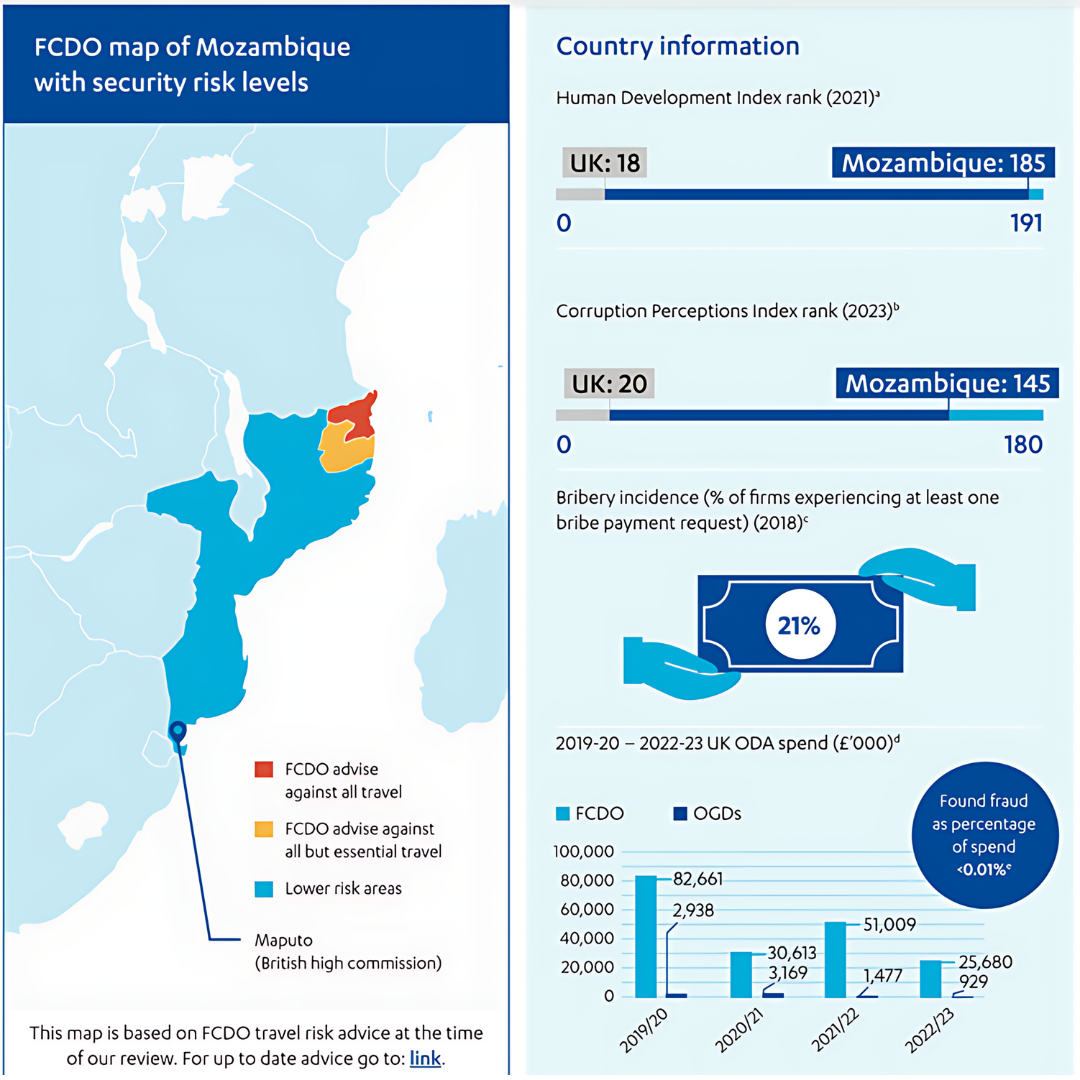

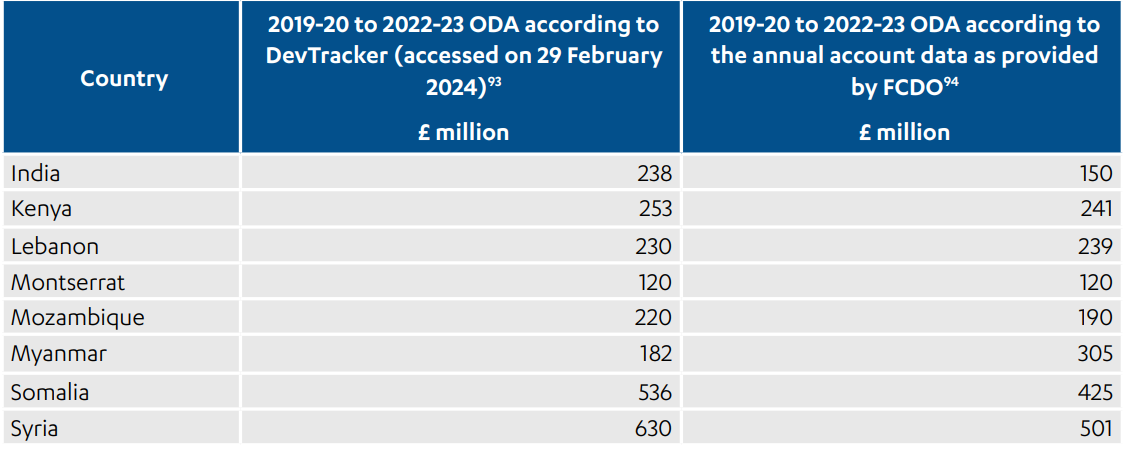

4.1 Case studies for Mozambique, Kenya and India are summarised on the subsequent pages, presented in the order in which we visited the countries. The case studies highlight the main strengths, weaknesses, challenges and opportunities that we observed. These are followed by our analysis of the efficiency, effectiveness and coherence of counter-fraud in UK aid. This brings together findings from the Mozambique, Kenya and India case studies, insights from our lighter-touch review of aid delivery in Lebanon, Montserrat, Myanmar, Somalia and Syria, and our review of documentation and discussions with central teams. Figure 5 shows the case study countries alongside their UK ODA spend and fraud data. The figure also shows differences in how the fraud liaison officer (FLO) role, described in paragraphs 3.22 to 3.25, is deployed in each of the case countries.

Figure 5: Map of case study countries and ODA spend in 2021-22

Notes: The values for fraud found are based on closed cases recorded in internal FCDO reporting. Fraud is not necessarily found in same year as it occurred. Additionally, FCDO does not capture fraud that occurs in pooled funds to which it contributes, as discussed later in the report.

FCDO ODA spend is based on the published accounts for FCDO while the numbers of programmes come from the UK government’s Development Tracker website. Spend in the published accounts differs from the that published on the Development Tracker website as explained in Annex 1.

Country case study: Mozambique

In the two decades after its first democratic elections in 1994, Mozambique achieved high economic growth, human development progress and relative peace. This success attracted substantial amounts of Official Development Assistance (ODA), including budget support from donors such as the UK. During this period, Mozambique received 10-15% of total foreign direct investment inflows into sub-Saharan Africa. This momentum ended abruptly in 2016 with the revelation of £1.73 billion in state-backed ‘hidden debts’, guaranteed without parliamentary approval and much of it diverted to enrich private individuals. This led to a protracted economic downturn. ODA fell from 17.5% to 12.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) between 2013 and 2018. This combined with cyclones, conflict in the north and the impact of COVID-19, slowed Mozambique’s progress. It remains sixth from bottom in the United Nations’ Human Development Index and is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world.

Fraud and corruption are commonplace in Mozambique, including political, petty and grand corruption, embezzlement of public funds, and a deeply embedded patronage system. Mozambicans face a constant threat of fraud and corruption. We heard many typical examples such as citizens being required to pay bribes at police checkpoints, to register children at schools or obtain exam results, to access ostensibly free healthcare, or to obtain official documents such as a driving license. During our fieldwork, opposition groups were protesting about widespread municipal election irregularities that were highlighted by election observers and donors including the US, EU and UK.

UK aid to Mozambique

The UK still does not provide direct budget support to the Mozambican government. One of the five goals of FCDO’s country plan is “promoting freedom and democracy” which includes “strengthening inclusive, accountable, and democratic politics and institutions”. Six of the ten in-country ODA programmes, which are all FCDO-managed, focus on this, representing around 60% of the 2023-24 programme budget. Included in our sample were the Tax and Economic Governance (TEG) and Transparency and Accountability for Inclusive Development (TACID) programmes.

Strengths

We found that programmes had been designed to minimise fraud risk. Procedures were in place to manage risk during delivery which were embedded into partner selection. For example, the Waala programme to deliver family planning products to girls and women involved using the United Nations Population Fund Sexual & Reproductive Health Agency (UNFPA) to undertake procurement outside the government systems and had built in stock checks along the delivery chain to ensure products arrived at remote clinics. The programmes, designed to promote freedom and accountability, directly tackle priority fraud and corruption challenges, including TEG which provides technical support to the government on public investment, debt and fiscal risk management relating to the growing extractives sector, and TACID, which includes funding the local affiliate of Transparency International, Centro de Integridade Pública (CIP).

Programme staff took fraud risk seriously and understood FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework requirements. We saw examples where additional controls, such as spot checks, had been implemented, although this was more down to individual initiative than necessarily aligned to the risk. More importantly, however, we saw evidence of programme teams responding to potential risks. A payment was made to a partner from UK funds, rather than from other donor funds that the UK managed, which was permitted by the newly implemented Hera finance system. This was quickly rectified, and the Human Development, Climate Change and Humanitarian team subsequently implemented additional manual controls to mitigate this risk.

Programme staff demonstrated an understanding of the importance of their relationships with partners. Partners, for their part, took risks seriously. We saw examples of good practice, such as SNV, a partner delivering solar home systems for the UK-Sweden-funded Brilho programme (which means “shine” in Portuguese). SNV had developed an impact assessment framework that included randomly sampling customers, using their mobile phone numbers provided as part of the service, to assess the impact of the programme and ask whether they had to pay more than they should for the equipment. This identified instances of overcharging that SNV could then address.

Weaknesses and challenges

When the fraud liaison officer (FLO) left the team in January 2023, a new FLO was appointed, however, they did not receive a proper handover, training or support. Despite their attempts to get information on ongoing fraud cases and support on how to undertake their role from the central fraud team, staff turnover in the central team meant the FLO did not have the training or support needed to undertake the role effectively. Following our visit, FCDO Mozambique is looking to strengthen its counter-fraud capacity.

Programme staff informed us that FCDO’s ‘zero tolerance’ messaging was not always understood by partners to mean “zero tolerance for inaction to prevent and quickly rectify problems when they come to light”. They considered it likely that current zero tolerance messaging could disincentivise partners from raising fraud risks if not explained, and we noted examples where suspected frauds were investigated and addressed by partners before being reporting to FCDO. Very little fraud reporting occurs in Mozambique despite the high risks. Programme staff themselves were not aware of the International Public Sector Fraud Forum principle, adopted by the Public Sector Fraud Authority, that “Finding fraud is a good thing”, and some found this difficult to reconcile with the concept of zero tolerance to fraud as a communications tool and slogan.

FCDO Mozambique has a database of centrally managed programmes operating in the country, but noted that it finds it challenging to maintain full oversight of them, particularly those managed by some other government departments. This means activities and meetings may be taking place that the high commission is not aware of. A 2023 internal audit identified this challenge, noting it is incompatible with a Head of Mission’s notional accountability for all UK delivery in their country. FCDO Mozambique is aware of the challenge, and informed us it is working to strengthen its engagement and oversight in this area.

Opportunities

FCDO Mozambique has robust counter-fraud controls within programmes but could develop a more strategic approach to addressing corruption internally across its portfolio. It has further opportunities to increase engagement with representatives of other government bodies (such as the British Council) and externally with partners and like-minded donors. Similarly, communications about fraud tend to focus on compliance with the PrOF, and lack events or ongoing initiatives that bring people together to make learning effective, such as peer stress testing. FCDO’s annual Fraud Week was a missed opportunity internally and externally. FCDO emailed partners (only in English), disseminated materials to staff and held internal sessions for staff, but more could have been done to effectively engage staff and partners.

FCDO funds deep expertise in tackling fraud and corruption, including organisations such as CIP, and others that have substantial practical experience, such as SNV. At present, FCDO does not make use of this expertise to share learning across its own programmes or between partners. For example, the Waala programme has strong controls to ensure products get to clinics (dealing with direct fraud risks to UK ODA), but no checks to ensure girls and women are not having to pay bribes to access them. The implementing partner relies on government fraud prevention processes which include posters informing users that services are free of charge. SNV’s checks with solar home system customers could be adapted to address this. In general, FCDO could facilitate collecting and sharing data and information beyond programmes. This could be used to identify regions, institutions or transactions where fraud is particularly common, or where there are deliberate attempts to prevent accountability (such as efforts by some officials to sabotage a move to electronic payments) and support working with other stakeholders and government contacts to tackle it.

FCDO has good relationships with the multilateral organisations it funds, which helps FCDO to access more information than multilaterals strictly need to provide. However, the department could include better fraud monitoring as part of the programme design when commissioning programmes. This would give FCDO access to important information as part of the programme rather than having to ask for it later, which is particularly challenging with multilateral organisations. Good relationships should not replace FCDO oversight and, as also noted in a 2023 international audit, more physical visits to first tier and downstream partners would strengthen oversight of risks and mitigations in the delivery chain.

We are pleased to note that following our visit in November 2023, FCDO Mozambique:

- arranged a partners’ day in January 2024, where partners including SNV and CIP were invited to present on fraud prevention

- advertised for a dedicated delivery excellence manager with a risk and counter-fraud background, which will incorporate the FLO role.

Case study sources are in Annex 2.

Country case study: Kenya

FCDO describes Kenya as “a beacon of stability and democracy” that plays an important role in regional global governance and investment, with a significant presence of multilateral organisations, international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and private sector companies and investors. Despite good economic progress, poverty rates remain high and corruption is endemic. Kenya is ranked 126 out of 180 in the Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index.

Kenya loses a third of its state budget to corruption according to its former Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission chair. Corruption impacts every sector in Kenya, constraining the country’s development. Despite longstanding laws criminalising all types of bribery and corruption including facilitation payments, weak and corrupt public institutions undermine enforcement. Demands for bribes by officials, patronage and nepotism, procurement corruption and embezzlement, and mismanagement of funds are commonplace. FCDO anti-corruption specialists in Kenya told us that fraud and corruption is often subtle and sophisticated, including convincing false receipts and collusion.

UK aid to Kenya

FCDO sees Kenya’s development as critical for the East Africa region and the achievement of its wider sustainable development ambitions. Due to the high corruption risk, FCDO does not directly fund the public sector in Kenya. Anti-corruption programming is a key part of FCDO Kenya’s strategy and our sample of four programmes included the £3 million Kenya Anti-Corruption Programme and the Regional Economic Development for Investment and Trade programme (REDIT), which includes work to enhance trade transparency. During our visit, we also met with FCDO Somalia staff based in the high commission in Nairobi, Kenya. Somalia is ranked as the most corrupt country in the world.

Strengths

ODA programme delivery through the high commission in Kenya is supported by capable, often long-tenure locally hired staff, many of whom are allocated to financial management or project manager roles that are key to fraud prevention. This contributes to FCDO’s management of fraud risk in-country, since these staff maintain continuity and institutional knowledge during turnover of staff from the UK, and their contextual knowledge is valuable to UK staff posted overseas. Programme staff execute processes well, often adding further checks and balances to reassure themselves that fraud is not taking place.

We noted good fraud risk management processes built into programme design which staff apply effectively. This focuses on prevention in line with the principles for public sector fraud. FCDO Kenya’s Accountability and Results Team (ART), comprising local staff with financial backgrounds (including the fraud liaison officer), review programmes from concept note to procurement stages with context-specific fraud risks, and the evolving Kenyan fraud landscape.

There are ambitious FCDO programmes in Kenya. Staff are realistic about the level of risks being taken and control for these. For example, the Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF) Borderlands programme promotes community led peace and stability at the Kenyan borders with Somalia and Ethiopia, where proscribed militant groups are active. Programme staff manage to visit the region – an essential part of programme oversight – despite the security and travel risks. This involves them travelling in a Kenyan police armoured personnel carrier. FCDO also continues to fund the Hunger Safety Net Programme, which provides regular and emergency financial support to vulnerable communities in the northern drought-affected regions. FCDO has worked with the World Bank to build fraud prevention systems into the programme, such as biometric and unique personal identification numbers, and FCDO staff conduct regular site visits to the programme.

FCDO is recognised as a leader in tackling fraud and corruption in Kenya. Delivery partners described FCDO as “highly involved” in day-to-day programme management and more engaged than most other donors on fraud. World Bank staff explained that FCDO is identifiable for its rigorous processes with downstream partners, who understand and accept that this is a necessary part of delivering FCDO-funded projects.

Weaknesses and challenges

FCDO Kenya’s biggest weakness is in its strategic oversight of fraud risks. While the development director has responsibility for portfolio risk management, and a programme board considers overall risk as part of its review and approval process, effective learning across the portfolio on fraud risk is not taking place. There are a lot of people doing a little on fraud risk management, and while it is important that everyone sees fraud risk management as part of their responsibility, there is no one at a senior level linking together the various activities to enable lesson learning and knowledge sharing or inform strategic decision-making. For example, the mission runs an anti-corruption programme that seeks to build evidence and develop innovative and practical interventions to address corruption in Kenya, yet its tools and research outputs are not proactively shared across programme delivery teams. Similarly, other government department staff have good relationships with FCDO staff but tend not to share learning or experience of fraud risk management.

Despite good processes around fraud, fraud reporting is low in FCDO’s programmes in Kenya. The senior management team recognise this, and programme staff engage frequently with downstream partners to encourage openness and emphasise that FCDO’s ‘zero tolerance’ approach to fraud means zero tolerance to inaction and poor processes around fraud, rather than a default to punitive measures. However, there are still perceptions of negative consequences of finding fraud, particularly among smaller NGOs, that discourage openness. A further challenge is that fraud can be seen as too entrenched or beyond the scope of programmes to address, such as ‘thank you’ payments by recipients of aid to agents distributing it. These may be bribes, facilitation payments or extortion, but their payment is so normalised that they are challenging to tackle, and staff would welcome further practical guidance on how and when to tackle them.

The volatility of the ODA budget in Kenya – cut from around £100 million to £24.6 million with little notice and is due to rise to £81 million in 2024/25 – presents a challenge for fraud risk management. Staff are concerned about the impact this has both on fraud risk and their ability to oversee and properly control it.

FCDO Kenya is aware of 102 centrally managed and other government department programmes active in Kenya. The high commission does not consider itself ultimately accountable for these programmes, which it does not have the capacity to oversee, but has begun work to identify and rank them by risk rating to help it prioritise how to engage with programmes and manage reputational risks.

FCDO’s problematic global rollout of the Hera finance system led to delays of up to six months in paying downstream partners. Staff in Kenya report that few effective controls were in place for a period of around six to eight weeks, during which the office relied on trusted staff to invent and apply controls manually using spreadsheets and offline record-keeping. Programme staff expressed concern about how easy it would have been to defraud the system during this time. HERA continues to confuse and frustrate, consuming disproportionate amounts of staff time that could otherwise be spent on managing programmes.

Opportunities

FCDO Kenya and much of FCDO Somalia are both based in the UK high commission in Nairobi. There is good interaction between the counter-fraud leads of both offices, and some examples of coordinated learning. For example, while FCDO Kenya did very little with its partners during Fraud Week, which came shortly after a major royal visit which caused staff to be overstretched, the Somalia team invited Kenyan partners to its training events. There is potential to build upon this cross-department engagement, also including key contacts in other government departments, arms-length bodies and other entities. For example, we saw opportunities for FCDO to learn from experienced staff in the British Council and British Chamber of Commerce but also a need for other government department representatives to have a better understanding of fraud and corruption risks which they could learn from FCDO.

In response to the UK’s ODA budget reductions, FCDO Kenya cut monitoring, evaluation and learning components from most programmes. FCDO Kenya is currently designing a cross-cutting programme to support monitoring, evaluation and learning across all of its programmes. This kind of approach, drawing on the counter-fraud expertise of FCDO Kenya’s governance advisors and counter-fraud specialists, has the potential to promote a more strategic and proactive approach to tackling fraud across the Kenyan portfolio and in the wider aid delivery system. This should bring good practice and knowledge from FCDO Kenya’s anti-corruption programming to support its programmes in all sectors.

Staff suggested that counter-fraud training could be improved with more engaging, context-specific, scenario-based learning to bring the reality of fraud risks relevant to the country programmes to light and share lessons across teams. Staff described current training on fraud risk management as being largely generic, individual online training. There is also potential to collect and share learning and data on fraud to deepen FCDO’s understanding of fraud types and prevalence in the sectors it operates and the impact of fraud on people expected to benefit from its programmes. There is further potential for better sharing of learning and data with other donors to inform collective action while also encouraging openness and discussions around fraud more generally.

Case study sources are in Annex 2.

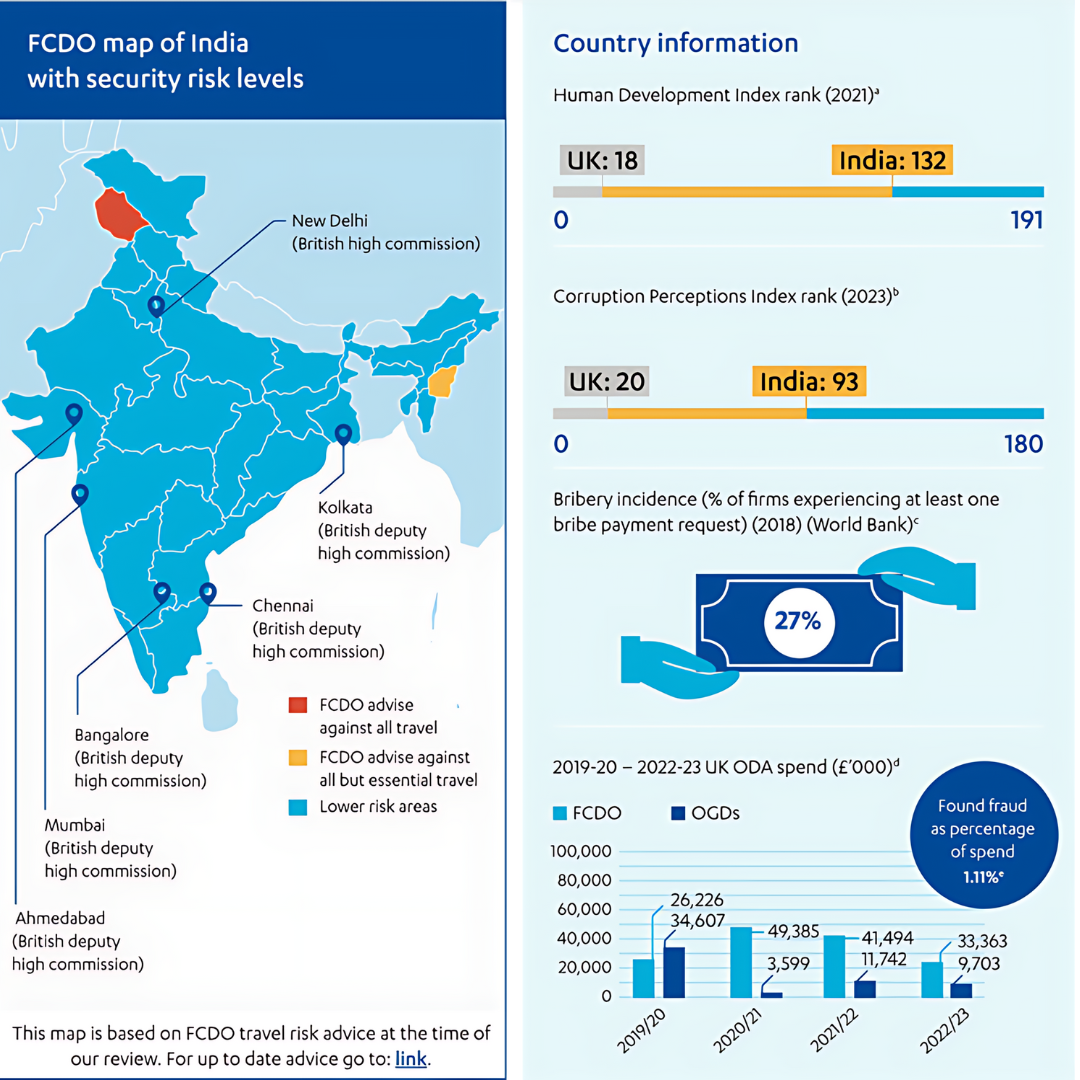

Country case study: India

India is the world’s largest democracy with a population of more than 1.4 billion. It is the third largest economy and one of the UK government’s highest foreign policy priorities. India has made significant progress in reducing extreme poverty from 48% of the population in 1993 to 10% in 2019. The last decade has also seen more effective government and improved regulatory quality and control of corruption, according to World Bank indicators, but also a decline in civil liberties and rule of law.

Indian legislation criminalises “attempted corruption, active and passive bribery, extortion, abuse of office and money laundering” although it does not outlaw facilitation payments. On one hand, private sector companies have been pushed to tighten their compliance processes, on the other, authorities have been accused of selective enforcement of anti-corruption laws. Corruption remains endemic in India, affecting all levels of governance across the public and private sectors. India has the “highest overall bribery rate” and the “highest rate of citizens using private connections” in Asia according to Transparency International. Petty corruption, grand corruption, procurement fraud, patronage networks and nepotism, including caste-system based nepotism are commonplace.

UK aid to India

As India’s economy has grown, and despite there being more than 140 million people still in extreme poverty, the UK has transitioned away from traditional aid programmes towards a partnership based on mutual national interests agreed with the Indian government. The UK’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) to India is now focused on providing technical assistance, research partnerships and equity investments which aim to achieve development objectives alongside financial returns. British International Investment (BII) is the UK’s main development finance institution, making commercial investments in low and lower-middle income countries in Africa and Asia, including India. However, FCDO India’s ODA portfolio is unique within FCDO’s network in making its own development capital investments. Compared to to BII, FCDO India invests in earlier stage, higher risk companies that it considers have high development impact potential – especially in terms of tackling climate change and job creation. Our sample of five programmes included two capital development funds with a combined budget of £172 million and $1 billion (around £790 million) loan guarantee to enable increased lending from the World Bank to the Indian government.

Strengths

The high commission in India has a more integrated structure than our other core case study countries. All UK staff, such as those from the Department for Business and Trade, and arms-length bodies, such as the British Council, as well as FCDO, are included in one organisational structure with some departments having direct reporting lines to the Head of Mission (BII staff are not included in this network, although it does have a large presence in India). We saw positive examples of engagement across programme areas, including sharing knowledge about risk management in capital investments, for example.

Development capital is deployed through professional asset managers following due diligence by FCDO on the asset managers. FCDO has an oversight role as a member of the governance committees (which could include one or more of investment, advisory or development committees) for the funds it invests in, giving it a role in ensuring appropriate investment policies and fund performance. We found that FCDO programme staff had a strong understanding of the regulatory framework in which investments were deployed and of FCDO’s programme management processes. They also demonstrated an awareness of challenges caused by the problematic implementation of the Hera finance system, including approvals by individuals with limited knowledge of programmes or outside the line of accountability and lack of visibility of financial information, and developed offline controls where deemed necessary.

FCDO India has a Delivery Unit designed to help the India network deliver UK government priorities including supporting programme delivery. This includes the fraud liaison officer (FLO) role and facilitating learning across the department; for example, to help teams determine how to apply FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework rules and guidance to investments. The Delivery Unit does not look for fraud but does help ensure good governance practice by undertaking spot checks of risk registers to promote compliance and consistency across the portfolio. Following a recommendation in a 2023 internal audit, the Delivery Unit has begun to incorporate a review of programme agreements and due diligence assessments into its spot checks.

Weaknesses and challenges

In high fraud-risk countries, FCDO tends to have anti-corruption programmes due to the higher significance of tackling corruption to safeguard development objectives. FCDO India’s focus on technical assistance and capital investments, however, means it does not have any anti-corruption programmes. Despite being the largest UK delegation with over 700 staff from 15 government departments and seven regional deputy high commissions, as well as a large high commission in Delhi and having one of the largest ODA budgets, FCDO India does not have a governance advisor or other deep anti-corruption expertise.

The FLO in India did not receive any formal training after being appointed, and was not aware of the FLO job description until recently. The FLO role is a 10% time commitment of a UK staff member who splits their time between the UK and India and will be rotating to another country shortly. The FLO has some previous programme management experience but does not have a financial background and has had to learn on the job. They are supported by a financial manager with good programme finance experience and a deputy FLO role has recently been created. The team has worked diligently to manage reported fraud concerns but felt insufficiently supported by the central counter-fraud team.

Due to its focus on capital investments, FCDO India considers the risk of fraud losses attributable to ODA to be low. This is because gains or losses in investments depend on multiple factors and only crystallise on the sale of shares. Fraud can reduce the value of investments, such as if a company is fined or loses business, but it may also increase the value, for example, if a company pays bribes or benefits from nepotism to win contracts. Outsourced asset managers are strongly focused on ensuring regulatory compliance prior to investment, and also work to strengthen governance systems within investees, which will help to mitigate risks. FCDO has also strengthened its environmental, social and governance framework for asset managers with a view to strengthen controls and ensure regulatory compliance. However, little is done to understand the wider fraud and corruption landscape in which investees operate, which is extremely high. As the 2023 internal audit noted, FCDO is exposed to delivery, financial and reputation risks if systematic frauds are not identified and dealt with appropriately.

The internal audit also highlighted risks relating to low staff morale and recruitment challenges. Low morale can disincentivise openness about concerns, including about fraud. In our interviews, we heard an example of recent improvements in leadership that made raising concerns more acceptable. However, staff reiterated challenges around morale and recruitment, especially relating to FCDO’s inability to attract skilled, locally hired finance and programme management staff due to low pay compared to the market.

Despite good practice relating to the integrated governance structure at the strategic level, noted above, we identified gaps in relation to fraud risk management. For example, a Deputy Head of Mission had been deployed without any introductory training for over six months. Similarly, we heard from Home Office officials managing programmes through FCDO’s finance system that appeared to have fallen between the gaps, with no knowledge of the Programme Operating Framework and not being required to undertake counter-fraud training by either department.

Opportunities

FCDO’s PrOF, which sets out rules and guidance for all FCDO programmes, is written with traditional aid programmes in mind, and is therefore not easily applicable to capital investment programmes. FCDO noted that the requirements of other investors, needs of investees and investment market regulations need to be duly considered when determining good practice for fraud risk management throughout the investment lifecycle. FCDO India’s Development Unit is working with the central PrOF owners to develop guidance for capital investment programmes. Such guidance has the potential to clarify:

- where FCDO’s responsibilities lie in capital investments through asset managers

- how to mitigate residual risks where fraud risk management is outsourced

- where and how FCDO should engage with the wider fraud and corruption risks that companies in India commonly face.

Based on recent learning, FCDO has the opportunity to strengthen its contracts with partners. A fraud occurred in a programme managed through a memorandum of understanding (MOU) rather than a contract or grant. The MOU has no legal obligation for the partner to return fraud losses and has resulted in a drawn-out negotiation. The 2023 internal audit also identified contracts with no fraud reporting clauses and at least one instance where procurement fraud had not been reported up the delivery chain. The Delivery Unit is working to address these gaps, and gaining legal advice for appropriate contract clauses.

Case study sources are in Annex 2.

Efficiency: How efficiently does the UK government deploy resources to ensure robust country-level fraud risk management in the aid delivery chain?

Programme staff are efficiently allocated to manage fraud risks in-country, although there are threats that need to be addressed

4.2 FCDO staff in-country are either hired locally or contracted in the UK and posted overseas. Locally hired staff are on local salaries. This is usually cheaper, while also bringing local knowledge and, if retained, can build long-term capability within the country. UK staff posted overseas have UK contracts, salaries and benefits, and are posted typically for periods of two to three years. These staff are usually more expensive but build knowledge and experience across the FCDO’s global network.

4.3 Across our sample, senior responsible owners (SROs) were predominately UK staff posted overseas, whereas programme responsible owners (PROs) and other programme management team-members were usually locally hired staff. This mix enables cost-effective long-term knowledge-building among locally hired staff with day-to-day programme management responsibilities, while rotation of SROs introduces an important counter-fraud control at the oversight level.

4.4 When deployed effectively, as for most of our sample, this is an efficient way to manage fraud risks in programme teams. However, it takes time for SROs to get up to speed, so if postings are less than three years, which we saw in several instances, this can become inefficient and introduce risk. This challenge can be exacerbated when SRO postings become synchronised in a country, as was the case in Kenya.

4.5 The typical split between UK staff posted overseas and local hire roles can also create a two-tier culture. We heard of an example whereby a locally hired staff member had abused her position to encourage others to use salary advances to loan her funds to pay school fees for her children. As the school fees increased, the scheme collapsed, resulting in severe distrust between the leadership (comprising UK staff posted overseas) and locally hired staff that took years to normalise. During our discussions with programme staff, we found their day-to-day experiences of corruption were not always fully understood by UK staff posted overseas, when this knowledge could provide important insights for programme delivery. Overall, however, we found that staff from the UK and locally hired staff had constructive working relationships.

Counter-fraud and programme teams face recruitment and retention challenges in competitive markets

4.6 FCDO’s first line of defence – SROs, PROs and other programme staff – had a strong understanding of their risk management responsibilities. Locally hired staff, in particular, had strong knowledge of the local fraud landscape and were relied upon by SROs to build a rapid understanding of risks at the start of their deployment.

4.7 Since 2020, FCDO has faced short-notice ODA budget reductions from £11.8 billion in 2019 to £7.6 billion in 2022, due predominantly to a 28% reduction of total ODA as a proportion of gross national income alongside burgeoning expenditure of ODA on refugees in the UK, of around £3.5 billion in 2022, primarily through the Home Office. This has caused major challenges in managing risk, discussed later in this report. It also means many FCDO countries now have a higher ratio of programme management staff compared to spend, even after reductions in local staffing levels. It is important to recognise that smaller programmes do not necessarily require proportionally less programme management resource, and that reducing budgets can require more, rather than less management time. However, countries such as Mozambique, Kenya, Lebanon and Myanmar reported healthy staffing levels.

4.8 In more competitive markets, it has been harder to attract and retain skilled staff. UK-based teams, including FCDO Syria, which is partially based in East Kilbride, and FCDO India reported challenges hiring and retaining experienced programme staff due to below-market salaries. Other factors reported to us by FCDO that make it harder to recruit included perceived instability of jobs due to ODA budget reductions, enhanced vetting requirements and delays in completing these, and restrictions in external recruitment. FCDO Kenya is about to increase its ODA spend from £25 million to £81 million in a year, requiring staff recruitment in another competitive marketplace. FCDO is also imposing restrictions on external hires for UK contracts, vastly limiting the talent pool available for relatively niche areas such as counter-fraud.

4.9 In several of our interviews, low morale was highlighted as a concern for retaining high-quality staff. Internal audits raised concerns about low morale and high rates of reported bullying, harassment and discrimination in FCDO’s annual ‘people survey’ in relation to staff retention in specific countries. Globally, the FCDO people survey demonstrates stubbornly high rates of reported bullying, harassment and discrimination. These issues can impact fraud risk management by threatening continuity, disincentivising openness about issues such as fraud, and potentially providing a motivation for permitting fraud (see Figure 6).

There is a strong reliance on third-party risk management, which may not be good value for money

4.10 Like many donors, FCDO designs and oversees programmes but usually outsources their delivery to partners – companies, non-governmental organisations or multilateral institutions. For larger programmes, the first-tier partner’s main role is often to manage multiple downstream partners. This results in FCDO outsourcing key risk management processes such as due diligence and results monitoring, while – according to FCDO’s Programme Operating Framework (PrOF) – SROs remain accountable for programme risk management and PROs are responsible for day-to-day risk management. In practice, this means FCDO programme teams assess the first-tier partner to gain assurance that they have the capacity and systems to manage risks in the delivery chain. This can result in pushing responsibility for risk down the delivery chain and in partners covering the cost of fraud losses. We highlighted this in our 2021 review where we recommended FCDO conduct more work to understand who bears the cost of fraud and the potential negative consequences of this. This remains a challenge for many partners, although we did see good examples, including in Syria, of where FCDO had written-off losses where it considered partners were not at fault.